Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits

domestic violence against women

miss opportunity to reframe

discourse

Gaps between evidence on underreporting and visual

representation of domestic violence

Abstract

Domestic violence against women (DVAW) is a global pandemic that affects approximately one in three women living in the United Kingdom. One of the biggest challenges in combating and preventing DVAW is the underreporting of incidences to law-enforcement by victims and the collective silence of bystanders who are aware of the abuse but choose to remain silent (i.e. social silence). This degree project compares evidence regarding social silence and underreporting of DVAW and how DVAW is represented in British awareness campaigns to answer the research question: What gaps exist between evidence available in respect of contributing factors to social silence and underreporting of DVAW and how key players in the space of DVAW prevention in the United Kingdom (UK) represent DVAW in public awareness campaigns aimed at addressing these issues? A literature review served to establish state of the art evidence and was followed by a Foucauldian discourse analysis of selected visual media texts from awareness raising campaigns published by British key players (i.e. NGOs and government agencies) in the area of DVAW. The analysis was conducted in three stages: 1) relevant discourse fragments were identified according to strict sampling criteria, 2) texts were analysed with a step-by-step approach, in order to identify key themes and a typical sub-sample of discourse fragments, and 3) an in-depth analysis of two typical campaign texts was conducted. The analysis revealed that a range of misalignments and gaps exist. DVAW is represented in isolation as an issue of individuals rather than society. Some of the most problematic attitudes contributing to social silence and underreporting of DVAW such as victim blaming remain largely unaddressed. Victims of DVAW are represented in isolation and the responsibility to act and stop the abuse is often placed on the them. Perpetrators of DVAW in particular, but also men in general, are largely excluded from the discourse. Instead of encouraging victims and building their confidence, a bleak picture of isolation and fear is painted in campaign texts. Some of the discourse fragments included in the analysis appear to perpetuate the very misconceptions and stereotypes they are trying to address. There is ample opportunity for British key players in the space of DVAW to take a leading role in challenging the current discourse and assume their role of influencer in the fight to break social silence and increase the reporting of DVAW.

Table of content

1. Introduction... 5

2. Background... 6

2.1. Istanbul Convention – Article 12 ... 7

2.2. Addressing problematic attitudes and achieving social change ... 8

2.3. UK Context ... 9

3. Literature review and existing evidence... 10

3.1. Key surveys and reports ... 11

3.2. Complex, systemic issue... 11

3.3. Importance of public attitudes and perceptions of DVAW ... 12

3.4. DVAW – an open secret... 13

3.5. Main contributing factors to social silence and underreporting ... 14

4. Methodology ... 17

4.1. Discourse Analysis and theoretical lens ... 18

4.1.1. Foucault – Discourse, power/knowledge, subjects, and truth ... 19

4.1.2. Intertextuality... 20

4.2. Method ... 21

4.2.1. Sampling ... 21

4.2.2. Operationalising Discourse Analysis ... 23

5. Analysis... 24

5.1. Selected campaign texts... 24

5.2. Discourse Analysis of campaign texts... 26

5.3. Sub-sample analysis ... 31 5.4. Synoptic analysis ... 36 6. Conclusion ... 39 References... 44 Appendix ... 47 Annex 1 ... 47 List of Tables Table 1: Selected campaign texts for discourse analysis ... 25

List of abbreviation

CDS Critical discourse studies

DVAW Domestic Violence Against Women

DV domestic violence

EIGE European Institute for Gender Equality

EU European Union

FRA European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights HMIC Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary NGO Non-government organisation

UK United Kingdom

VAW Violence Against Women WHO World Health Organisation

1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence or domestic violence against women (DVAW) is a global pandemic that affects approximately one in three women at least once in their adult lives (WHO, 2013). DVAW is by no means limited to women from particular socio-economic backgrounds or specific countries. According to a recent study conducted by the World Health Organisation (WHO), 19.3 percent of women living in high-income countries of Western Europe have fallen victim to domestic violence (DV) at least once in their lives (2013, p. 47).

Despite the high prevalence of DVAW, many cases remain unreported to authorities (European Commission, 2016b, p. 1, FRA, 2014, p. 3, Gracia, 2004, p. 536). Interestingly, cases of DV are often known to the social circle surrounding victims, but less than 20 percent of people aware of domestic abuse reported it to the police or a public/independent support service (Eurobarometer 449, 2016, p. 84-85). The issue then is no longer a matter of ignorance and simply not knowing, but a matter of social silence (Gracia, 2004, p. 536).

The important role of public attitudes and perceptions of DVAW in combating the issue has been widely recognised. Gracia (2014) argues that "public perception and attitudes shape the social climate in which [DVAW] takes place and either perpetuate or deter its occurrence" (p. 380). Victim blaming attitudes, for example, can create a ‘climate of tolerance and acceptability’ of DVAW and influence behaviour of the public, professionals, victims or perpetrators (European Commission, 2015, p. 62).

Public awareness campaigns are helpful in both informing victims of DVAW about strategies for getting help and to influence public attitudes and norms regarding DVAW (Campbell and Manganello, 2006, p. 14). To address the issue of underreporting and to raise awareness regarding DVAW most key actors in this domain, both government agencies and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) have published multiple awareness campaigns in recent years. The way DVAW is represented and framed in these awareness campaigns is highly relevant, because representation and discourse (i.e. everything that is being said anywhere on a particular issue) structures the way we think about something, and consequently the way we act based on that thinking (Rose, 2012, p. 190). In other words, representation and discourse have the power to either

perpetuate current attitudes and perceptions around DVAW or stimulate desired social change.

The aim of this degree project is to unveil potential gaps and misalignment between available evidence and how British key players represent DVAW in public awareness campaigns aimed at addressing social silence and underreporting. The main research question, therefore, is: What gaps exist between evidence available in respect of contributing factors to social silence and underreporting of DVAW and how key players in the space of DVAW prevention in the United Kingdom (UK) represent DVAW in public awareness campaigns aimed at addressing these issues?

To this end, in a first step, a literature review will serve to establish what available evidence suggests are the main issues around social perceptions of DVAW and current DVAW discourse that lead to underreporting and social silence. In a second step, discourse fragments (i.e. particular campaign texts) from awareness campaigns published in the last five years by some of the major British players in the space of DVAW, including regional police forces and NGOs, will be visually analysed using discourse analysis, and gaps and misalignments will be discussed.

This paper is structured into five main chapters: 1) Background, 2) Literature Review of existing evidence regarding social silence and underreporting of DVAW, 3) Methodology section providing some theoretical background and describing the specific methods used for the visual analysis, 4) Analysis containing a detailed discourse analysis of ten selected discourse fragments, a sub-sample of two typical discourse fragments and a discussion of identified gaps and misalignment, and 5) Conclusion summarising main findings and results, including a brief reflection on how the DVAW discourse deployed by key players could be optimised to ultimately drive meaningful social change of perceptions and attitudes towards DVAW.

2. Background

Recognising the magnitude and negative impact of DVAW at all levels of society, many steps have been taken across the European Union (EU) over the past few years to achieve a more concerted approach to tackle the issue of DVAW, and violence against women (VAW) more broadly. In 2010, DVAW was declared a high priority by the

European Commission (p. 5), culminating in the 2011 Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention aiming to prevent and combat VAW and DV (European Commission, 2016b, p. 4). Furthermore, the European Commission declared 2017 a year of focused action to fight VAW (Goodey, 2017, p. 1770). The Council of Europe acknowledges VAW as a human right violation, positioning the issue clearly at the highest societal level.

Apart from the far reaching individual and psychological implications for victims and their families affected by DVAW, exposure to a violent partner also has severe consequences on social and economic outcomes. The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) estimates that VAW costs approximately 226 billion Euro per year across the EU, of which 109 billion Euro are attributed to intimate partner violence against women (2014, p. 115). Cost calculations included lost economic output from women missing work, health services costs, social welfare costs and justice costs, personal costs, and costs for specialised services.

2.1. Istanbul Convention – Article 12

The aim of the Istanbul Convention is to prevent and combat VAW and DV through 1) effectively providing services, 2) protecting victims, 3) prosecuting the perpetrators, and 4) preventing violence (European Commission, 2016b, p. 4). Signed by all 28 EU member states and a total of 44 signatories, the Istanbul Convention marks an important step towards an orchestrated approach to the issue across the EU.

The fourth pillar of the Istanbul Convention – prevention – is the most relevant for this degree project. The goal of the prevention pillar is to promote “awareness through awareness-raising campaigns and education at all levels to ensure that the general public are fully informed of the various forms of violence that women experience on a regular basis as well as of the different manifestations of domestic violence” (European Commission, 2016b, p. 3). Furthermore, the Council of Europe aims to “bring societal change by challenging acceptance or denial of violence [against women] and gender stereotyping” (European Commission, 2016b, p. 4), and therefore, clearly positions the issue at a societal level.

In 2014, the Council of Europe, published Preventing Violence Against Women: Article 12 of the Istanbul Convention outlining in detail how comprehensive preventative measures can contribute to a reduction in violence against women (2014, p. 5). The

report states “the purpose of Article 12 is to reach the hearts and minds of individuals to ensure changes in mind-sets, attitudes and beliefs towards women, their role and status in society, their sexuality, as well as women’s agency” (p. 7).

2.2. Addressing problematic attitudes and achieving social change

Public awareness-raising campaigns have been identified as an effective measure to challenge prevalent stereotypes that perpetuate VAW (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 18). The available literature emphasises the importance of how such campaigns are framed and the messages conveyed. The Council of Europe provides clear guidance in this regard, suggesting to target awareness-raising campaigns at the different levels and to frame VAW accordingly. At a societal level it is suggested to frame VAW as an intolerable violation of human rights, at community level as a health and human rights issue showing benefits to the community of eliminating VAW and also provide practical solutions how the community can work together to prevent VAW, and at individual level messages of safety should be conveyed to women, informing them about their rights, existing laws, and services available for both victims and perpetrators (pp. 18-19). Traditionally, prevention initiatives and awareness campaigns target women in particular, advising them what to do (e.g. avoid particular situations, report the abuse, speak up, etc.) (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 19). However, campaigns telling women how to act, implies that a) DVAW is inevitable, and b) places the responsibility on the actions of women, rather than the perpetrator (p. 19). This bears the risk of perpetuating existing attitudes instead of challenging them. The Council of Europe, therefore recommends, that campaigns targeting the individual level should focus on the behaviour of abusive men and challenge gender stereotypes and men’s views of acceptable violence, abuse and controlling behaviour in relationships by focusing on and encouraging positive, alternative behaviours (2014, p. 19). Boyko et al. (2017) do highlight that campaigns have to be carefully designed in order to avoid backlash or ‘tuning out’ from the targeted population. Men, for example, may react defensively or even angrily, if they “feel unfairly blamed for the actions of others” (p. 2). Due to the immense influence men have on each other, focusing on teaching men how to intervene in other men’s abusive behaviours can foster positive anti-violence attitudes (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 31).

Most importantly, campaigns should do more than raise awareness, they should focus on delivering “specific prevention messages to specific groups in society to dispel myths, stimulate debate and change societal attitudes to address the culture of victim-blaming, among others” (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 20).

2.3. UK Context

Considering the global magnitude of DVAW, not only affecting women in the global South but to a comparable extent in the global North, I very specifically wanted to focus my research on a European country, in which great progress has already been made in terms of gender equality and social standing of women in general. The UK, one of the largest economies in Europe, currently led by both a female Prime Minister and female monarch, was a natural choice. Interestingly, figures in the UK for DVAW are significantly higher than the Western European average of 19.3 percent (WHO, 2013, p. 47). An estimated 28 percent of women have experienced DV (physical and/or sexual violence by a current or past partner) at some point in their lives since the age of 16 (Office for National Statistics, 2016a, p. 3). According to the latest Crime Survey for England and Wales, between March 2015 and March 2016 alone, 1.3 million women or 7.7 percent of the total population fell victim to DV (Office for National Statistics, 2016a, p. 8). Issues affecting such large numbers of citizens, threatening their life and health, are considered important public health problems (Campbell and Manganello, 2006, p. 15).

The issue of underreporting and social silence is equally prevalent in the UK. According to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (2016a), 79 percent of last year’s victims did not report their domestic abuse to the police (p. 6). An online survey conducted by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), revealed that 46 percent of DV victims had never reported their abuse to the police (2014, p. 31). In addition, the majority of people in the immediate social environment of victims or perpetrators who are aware of the abuse do not report it to authorities. In the UK, only 15 percent of bystanders report the abuse to police and 6 percent to public or independent support services (European Commission, 2016a, p. 84). Due to the issue of underreporting, the majority of VAW remains hidden and, as a result, perpetrators are not confronted (FRA, 2014, p. 3).

Key players in the area of DVAW

There are many actors in the UK who are active in the area of VAW or abuse in general, but the focus of this research will be on organisations that specifically concentrate their activities on DVAW, are also involved at a policy level and who I therefore consider to be key players. The focus areas of the identified key player NGOs in the space of DVAW range from provision of supportive services such as helplines, legal advice, and safe houses for victims of DV to raising awareness and promoting services provided amongst the general public or particular minorities (e.g. refugee populations, adolescents, etc.). Some of the most active key players are NGOs such as Women’s Aid, Refuge, the National Centre for Domestic Violence, Domestic Violence UK, Bede House and Hestia. The national government through the Home Office is a major influencer and key player as they are directly responsible to allocate funding for prevention and support services. In addition, police forces are crucial when it comes to directly responding to DVAW and ensuring victim’s safety. However, the national government has not been very active in the space of prevention, with the last major campaign being launched in 2010 and only focussing on adolescents. Local government agencies, police forces and municipalities seem to be more active, regularly publishing new campaigns. Collaboration regarding awareness-raising between NGOs and government agencies also take place frequently. As experts on the issue, the key players mentioned above take the role of opinion leaders and influencers, not only regarding public opinion, but also at policy level and are communicating from a place of authority. In other words, key players’ influence on the DVAW discourse can be expected to be particularly strong.

3. Literature review and existing evidence

In this section, I will review available and relevant evidence published in recent years regarding social perceptions of DVAW in the UK and Europe more broadly, to establish what we know about reasons why social silence and underreporting of DVAW are still very prevalent, and what the different barriers to reporting DVAW are. This chapter explores the first part of the research question, which is: What does available evidence suggest are the main issues around social perceptions of DVAW and current DVAW discourse that lead to underreporting and social silence?

3.1. Key surveys and reports

The commitment across the EU to combat DVAW and to understand the complex phenomenon within the wider social context including social and cultural norms permeating DVAW, becomes apparent in a range of highly relevant reports and surveys completed in recent years. In 2014, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) conducted a EU-wide survey ‘Violence against women: An EU-wide survey’ of unprecedented scope (42’000 women interviewed in all 28 EU member-states) to reveal the magnitude of the issue and learn more about women’s experiences with physical, sexual and psychological violence, including DV. In 2015, the European Commission published the review ‘Attitudes towards violence against women in the EU’ including all surveys conducted in the last 5 years in EU countries exploring public attitudes and responses towards DVAW. The review is based on 40 surveys from 19 EU countries, reflecting the responses from 85’000 European citizens (Gracia and Lila, 2015, p. 13). While the review crystallises some of the issues around the perception of DVAW very well, Gracia and Lila do emphasis that evidence published in academic journals of high scientific quality exploring attitudes towards violence against women in European countries have been few in recent years (2015, p. 15). They further argue that research around attitudes regarding VAW is underdeveloped and insufficient at this point in time (p. 15). The Special Eurobarometer 449 on Gender-based Violence, published in 2016 also by the European Commission as a follow-up study to the 2010 Eurobarometer 344, addressed some of the gaps identified by Gracia and Lila, focussing on levels of DVAW awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions. Eurobarometer surveys cover all 28 member-states represented in proportion to their population size.

In 2016, under the leadership of the Home Secretary at the time, Teresa May, Her Majesty’s Government formulated a strategy to end violence against women and girls. The strategy is a step for the UK towards ratifying the Istanbul Convention, therefore following the same four pillars framework for combating violence against women. 3.2. Complex, systemic issue

The UK and the EU as a whole have clearly recognised the complexity of the issue and the multiple risk factors that lead to VAW, more specifically DVAW. It is important to acknowledge “the gendered nature of violence against women as rooted in power imbalances and inequality between women and men” (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 6).

The 2016 strategy of the UK government clearly frames domestic violence as an inter-generational and gender inequality issue with wider social repercussions (HM Government, p. 8). Systemic change is needed in order to eliminate VAW, and social norms based on gender stereotypes have to be challenged (HM Government, 2016, p. 16, Council of Europe, 2014, p. 14). VAW does not have a single cause, but is the result of multiple risk factors (Boyko et al., 2017, p. 2). These risk factors occur at all levels – from societal level (e.g. gender inequality, glorification of violence and sexualisation of women in media) to an individual disposition towards violence (e.g. personal stress factors, emotional and cognitive deficits, substance abuse, childhood exposure to violence) (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 10). Despite the recognition that DVAW is a societal and systemic issue, just as much as it is an individual one, Boyko et al. (2017) argue that “gender violence-related research often focuses on the individual victims and perpetrators (less so the latter) rather than community and system-level or structural determinants and interventions” (p. 2).

3.3. Importance of public attitudes and perceptions of DVAW

Public attitudes and perceptions play a major role in preventing DVAW (Gracia and Lila, 2015, p. 17), and it is paramount to gain more insight, in order to better understand some of the root causes for DVAW and develop more effective interventions to prevent DVAW (p. 13). Boyko argues that “knowledge, practice and policy are shaped by the beliefs, values, norms and attitudes about violence entrenched in societies and cultures” (p. 2). Changes in those attitudes and norms that contribute to perpetuating VAW should be promoted (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 11). The Council of Europe sees prevention measures as a long-term strategy to achieve “far-reaching changes in attitudes and, ultimately, behaviours” (p. 5). Furthermore, a change in mind-set is necessary for any intervention to reduce VAW to be effective (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 5). One of the outcomes formulated in Her Majesty’s Governments strategy in regards to prevention of VAW is to “increase awareness across all sections of society that VAW is unacceptable in all circumstances” (2016, p. 15).

Gracia (2014) pointedly explains that "public perception and attitudes shape the social climate in which [DVAW] takes place and either perpetuate or deter its occurrence" (p. 380). Victim blaming attitudes, for example, can create a “climate of tolerance and

acceptability” (p. 62) for DVAW and influence behaviour of the public, professionals, victims or perpetrators (Gracia and Lila, 2015). Staub argues: “when there is limited public discussion of an issue, a condition of pluralistic ignorance exists. If no one is concerned, the issue seems unimportant and action unnecessary… given inaction, individuals shift awareness away from these issues to lessen their feelings of danger, personal responsibility, and guilt.” (2003, p. 491).

3.4. DVAW – an open secret

Both the Eurobarometer 499 survey (European Commission, 2016a) and the FRA survey show that DVAW is often an ‘open secret’ and that the social circle surrounding victims are aware of the abuse. More than one third of respondents (35%) in the United Kingdom reported to know a woman within their circle of friends and family who has been a victim of DV (European Commission, 2016a, p. 84). During the FRA survey, 47 percent of all women interviewed in the UK, knew of women amongst their friends and relatives, who are or have been victims of domestic violence, and 25 percent knew of a work colleague (2014, p. 156). Although the vast majority of Brits (96%) find DVAW unacceptable (European Commission, 2016a, p. 82), of the people aware of abuse in their immediate environment, 40 percent reported not to have spoken to anyone about it and a quarter of people (26%) only spoke about the abuse directly to the people involved or to a friend or family member (p. 85). Only 15 percent reported the domestic abuse to the police and 6 percent to a public/independent support service (European Commission, 2016a, p. 85). Gracia and Lila’s review also showed non-interventionist attitudes are still prevalent. A significant number of respondents preferred not to get involved, even if they were aware of a case of VAW (2014, p. 14). Gracia and Lila argue “if those who know about the violence choose to be silent and passive, this can contribute to creating a climate of social tolerance that reduces inhibitions for perpetrators and makes it more difficult for women to make DV visible, choosing not to report or abandon the relationship” (2014, p. 79). In addition to being aware of the abuse of people in their immediate social circle, there seems to be good knowledge regarding available support services, so it can be assumed that people know how to report abuse if they chose to do so. The majority of respondents (81%) reported to know of support services for women who are victims of DV (European Commission, 2016a, p. 34). Women in the UK are also aware of institutions or services that offer services to

victims of VAW – 67 percent of women in the UK know of Women’s Aid, 56 percent of Refuge, and 52 percent of a national or regional helpline (FRA, 2014, p. 193). However, 23 percent of women do not know if there are any specific laws or political initiatives for protecting women in cases of DV (FRA, 2014, p. 160). Only 48 percent of women have recently seen or heard campaigns about VAW (FRA, 2014, p. 162).

3.5. Main contributing factors to social silence and underreporting

Reasons for the high percentage of unreported cases of DVAW are both personal and societal (Gracia, 2004, p. 536) and reasons for not reporting DVAW are complex for both victims and bystanders who are aware of the abuse. For victims it is often not as simple as ‘just leaving him.’ One of the most important and powerful factors for women not to report abuse, is the fear of retaliation and revictimization. Reporting the abuse of a violent partner or attempting to leave a violent partner can lead to an escalation of abuse. The FRA data underlines how vulnerable women are, as one in six women reported to have experienced abuse after the relationship ended (FRA, 2014 p. 44). In 2016, 44 percent of all women killed in England and Wales were killed by partners or ex-partners (Office for National Statistics, 2016b, p. 3).

The issue of fear of retaliation, is further exacerbated by insufficient police response regarding DVAW. A report published by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) concluded “the overall police response to victims of domestic abuse is not good enough” (2014, p.6) and further states that “in too many forces there are weaknesses in the service provided to victims; some of these are serious and this means that victims are put at unnecessary risk” (p. 6). This included insufficient evidence collection at the scene of the abuse and perpetrators often not being arrested (p. 13). It is then unsurprising that 5-13 percent of women interviewed during the FRA survey indicated they did not report to the police, because they believed that the police would not or could not do anything” (FRA, 2014, p. 64). The HMIC report concludes that the low percentage of reporting “reflects women’s level of confidence in the authorities to respond appropriately and effectively” (2014, p. 13).

Another main reason for victims not to report abuse is that they do not consider the incident of abuse to be serious enough, so that reporting never even occurs to them (FRA, 2014, p. 64). This might indicate that a significant number of victims have a

tendency to ‘normalise’ their abuse (Goodey, 2017, p. 1779), which seems particularly concerning. Justifying the abuse by attributing it to external factors such as exposure to violence during childhood, substance abuse (e.g. drugs, alcohol), or stress also seems fairly common (Council of Europe, 2014, p. 11).

Shame and embarrassment is a further factor inhibiting victims to report DV to authorities. Some women (11%) indicate that they deal with the issue themselves, because they do not want anyone to know about it (FRA, 2014, p. 64). Feelings of shame and embarrassment cause even more women (23%) not to report abuse in cases of sexual violence (FRA, 2014, p. 64).

At a society level, attitudes are very much rooted in gender inequality and the perceived role of women in society. Attitudes towards DVAW such as “it is none of my business” and “it is a private matter” are still prevalent and were named as reasons for not getting involved despite being aware of the abuse (Gracia and Lila, 2014, p. 14). The most frequently named reasons for not reporting the abuse during the Eurobarometer survey were ‘I had no proof’ (21%), ‘it was none of my business’ (19%), and ‘the circumstances were not clear enough for me’ (16%) (p. 88). A small but still relevant percentage of people seem to either accept VAW to a certain degree, perceiving it as ‘not very serious’, or even ‘inevitable’, including insulting, hitting, controlling, or even forced sex (Gracia and Lila, 2014, p. 13). Hence, a certain level of acceptance and tolerance seem still to be prevalent.

Imbalanced power relations between men and women in society also seem to prompt attitudes of victim blaming (Gracia, 2004, p. 536) – an attitude which is imperative to address. Gracia (2014) argues “when the cause of the violence is attributed to the victims, incidents are more likely to be trivialised and seen as understandable or deserved, and hence as less unjust and more admissible. Such attitudes serve to excuse and partly absolve the perpetrators of violence and to the notion in the public’s mind that sometimes women are justifiably the victims of intimate partner violence… If people blame the woman who is the victim of the violence, they are likely to place the responsibility for solving the problem – at least partly – on her shoulders as well.” (p. 380-381). In a study conducted by Lee et al. (2016) with adolescents in the UK, the majority of respondents (76%) said that women and girls may ‘sometimes’ be to blame

for their abuse (p. 579). The 2016 Eurobarometer 449 survey revealed that 30 percent of Brits believe that “women often make up or exaggerate claims of abuse or rape” (p. 98). While, as mentioned earlier, 96 percent of Brits condemn DVAW, 18 percent believe that victims often provoke violence against them (p. 99), hence are partially responsible. In addition, it appears to be common to try and explain or even excuse the perpetrator’s actions with alcohol and drug use, instead of simply condemning the abusive behaviour (Gracia and Lila, 2014, p. 13). Lee et al. argue that substance abuse cannot be regarded as a main trigger for violent behaviour (2016, p. 579). Perpetrators and victims themselves named the experience of violence in childhood as the biggest contributing factor to violent behaviour (Gracia and Lila, 2014, p. 13). Furthermore, fights, family problems, and stress due to unemployment or financial problems were frequently named as risk factors as well (p. 14).

Lastly, evidence suggests many bystanders have no reason at all for not intervening or reporting DVAW. During the Eurobarometer 449 (2016a) survey the most frequently named reasons in the UK for people not reporting abuse in their immediate social circle was “I don’t know/No particular reason” (p. 88). This response implies a certain lethargy or even acceptance of DVAW amongst bystanders.

In summary, some women fear retaliation by their partner, are embarrassed/feel shame, are economically dependent on the perpetrator, or are afraid that authorities cannot or will not help them, and consequently remain silent or make up excuses when confronted by people of their immediate environment or health professionals (HMIC, 2014, p. 31, European Commission, 2016b, p. 1). There is a need to build women’s confidence to report DVAW, knowing that their abuse will be perceived as socially unacceptable and that their report will be taken seriously and responded to appropriately (Goodey, 2017, p. 1784) and that adequate support services are readily available. Furthermore, framing the issue of DVAW as an individual problem and putting the responsibility for reporting on victims, implies that women can solve the issue by acting differently, while the perpetrators are removed from the equation. DVAW should be framed as a societal issue and widely condemned as an inacceptable behaviour and human rights violation.

4. Methodology

In this chapter I discuss why I chose visual research as the focus of this degree project, what methods I used, and why.

In researching how British key players represent DVAW in their prevention and awareness-raising campaigns, how meaning is created, and how this contributes or shapes the DVAW discourse, a wide range of approaches could potentially be of interest and / or relevance. Not only the site of the image (i.e. the different materials or texts of a public awareness campaign such as posters and video clips), but also the production process and strategic development of public awareness campaigns, and aspects around audienceing (i.e. how different audiences understand and interpret particular texts) provide important insight into how meaning is created. However, in order to avoid dilution of analytical depth and to remain within the scope of the degree project, clear boundaries had to be defined. To this end, I focussed only on the site of the image, specifically, on selected visual texts from mass-media public awareness campaigns published by UK based key players in the area of DVAW, aimed at addressing the issue of social silence and underreporting.

In Western societies, visual representation is central to culture and the construction of social life and the values of a society (Rose, 2012, p. 2, Hall, 2013a, p. xvii). Our world is filled with visuals, from photographs and moved images such as film, to sculptures, architecture, and fashion. None of which is innocent or neutral – any visual is a depiction, a particular interpretation of the world around us, a representation (Rose, 2012, p. 2). Looking at the representation of a particular issue is based on the notion that different groups within a society make sense of their surroundings in different ways and these interpretations structure the way we think about something, and consequently the way we behave (Rose, 2012, p. 2). In short, representation creates meaning. However, to exchange meaning, a common understanding or sharing of the same ‘language’ is required (Hall, 2013a, p. xvii). Visual representation of DVAW not only creates meaning, but also reflects a particular common understanding of the issue – a cycle of representation producing common understanding of an issue and common understanding of an issue producing representation (Hall, 2013a, p. xvii). Analysing representation of DVAW and the created discourse can provide insight into how the

issue is understood in a particular context (i.e. the UK) and at the same time might reveal how particular representation of DVAW contributes to discourse shaping the way an issue might be understood by the general public and influence actions when confronted with the issue (e.g. social silence or reporting to authorities). Ultimately, research of visual representation is then trying to understand the social effects of visual materials and could provide valuable insights to provide guidance for future public awareness campaigns around DVAW.

4.1. Discourse Analysis and theoretical lens

Discourse analysis is of the methodologies used for critical visual research. It has been used in a wide range of disciplines within the social sciences and humanities (e.g. sociology, anthropology, cultural studies, and communication studies) and encompasses a wide range of approaches, each with its own assumptions, understanding of what discourse means, and particular methods (Wodak and Meyer, 2016, pp. 2-3). Although this complexity has greatly enriched the discussion around how meaning is created it does require me to clarify my understanding of discourse analysis further. For this degree project I will use a Foucauldian approach to discourse analysis, an approach categorised under critical discourse studies by Wodak and Meyer (2016). The Foucauldian understanding of discourse has fundamentally shaped the study of visual culture (Rose, 2012, p. 191).

According to Wodak and Meyer, critical discourse studies are rooted in linguistics, but not interested in linguistic units like words and sentences per se, but rather in analysing, understanding and explaining complex social phenomena (2016, p. 2). Approaches used in critical discourse studies have a common interest in deconstructing ideologies and power by systematically investigating semiotic data (written, spoken or visual) (Wodak and Meyer, 2016, p. 4). Wodak and Meyer (2016) argue that critical discourse studies (CDS) are “fundamentally interested in analysing hidden, opaque, and visible structures of dominance, discrimination, power and control as manifested in language. In other words, CDS aim to investigate critically social inequality as it is expressed, constituted, legitimised, and so on, by language use (or in discourse)” (p. 12). They further state that results derived from this type of discourse analysis are of practical relevance (Woday and Meyer, 2016, p. 19), so can provide tangible results to inform future awareness

campaigns. Under these premises, discourse is more than language, it is expressed in social practices and also exercises power, because discourses “institutionalise and regulate ways of talking, thinking and acting” (Jäger and Maier, 2016, p. 110/2567). The wide range of approaches used within the field of CDS, have in common that they are all deeply grounded in theory (Wodak and Meyer, 2016, p. 14) and basic philosophical premises that must be accepted by the researcher (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002, p. 4). So before diving deeper into the method applied in this degree project to critically analyse the DVAW discourse, I would like to take a closer look at Foucault’s philosophical premises, to establish a theoretical foundation.

4.1.1. Foucault – Discourse, power/knowledge, subjects, and truth

Foucault argues that things and actions only take on meaning within discourse (Foucault, 1972, p. 7). He was therefore particularly interested in the production of social knowledge and meaning through the way something is represented or talked about (i.e. discourse) (Hall, 2013b, p. 27-28). Foucault’s understanding of discourse, therefore, goes beyond language and its use and also includes social practices of everyday life (Hall, 2013b, p. 39). Discourse about DVAW for instance, shapes not only the way we talk and think about it, but also manifests in laws, institutions (e.g. women shelters, helplines), and practices (e.g. counselling) (Rose, 2012, p. 190). Furthermore, the relationship between power and knowledge is essential to Foucault’s theory. He argues that knowledge and power are inextricably linked – with knowledge always being an exercise of power and power always a function of knowledge (Foucault, 1977, p. 27). Hence, knowledge is not only a form of power, but power determines whether and in what circumstances knowledge is applied or not (Hall, 2013b, p. 33) However, Foucault did not understand power as exclusively oppressive, but as a productive network, which runs through the whole of society (Foucault, 1980, p. 119). In other words, Foucault did not understand power as something that is imposed on society from the top down, but something that is omnipresent, because discourse, too, is omnipresent (Rose, 2012, p. 192). Power produces discourse, knowledge, and subjects. The DVAW discourse, for example, produces, amongst others, subjects such as victims of DV, perpetrators or abusive intimate partners, and activists (Rose, 2012, p. 190). Lastly, Foucault (1980) argues that “each society has its regime of truth” and decides which types of discourse

it accepts as true (p. 131). In other words, knowledge is not necessarily a reflection of reality, and what we conceive as truth is constructed by discourse (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002, p. 13). While Foucault’s work is highly influential in discourse analysis and provides the theoretical basis for many approaches, Foucault did not provide a method for the analysis of specific texts (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002, p. 15/941) Furthermore, the vast amount of Foucault’s work available, has led to a complex and diffuse methodological legacy (Rose, 2012, p. 194). How theory is translated into specific instruments and methods of analysis, how it is operationalised, is therefore not always clear (Wodak and Meyer, 2016, p. 14). However, Jäger and Maier (2016) have developed a comprehensive Foucauldian approach to operationalise discourse analysis, described in section 4.2.2., which I applied in conducting the analysis for this degree project. 4.1.2. Intertextuality

An additional concept used in critical discourse analysis and important in understanding discourse is intertextuality. Discourse never consists of just one statement, one action, or one text (Hall, 2013b, p. 29) and it can be articulated through a diversity of forms (Rose, 2012, p. 191). In other words, no text has meaning by itself. Foucault (1972) argues that discourse is “from beginning to end historical – a fragment of history” (p. 117). Each text is an insertion into history, "in the sense that the text responds to, re-accentuates, reworks past texts, and in doing so helps to make history and contribute to wider processes of change" (Fairclough, 1992, p. 270). This accumulation of meaning through different texts, which refer to each other or receive new meaning by being put in context with another text, is called intertextuality (Hall, 2013c, p. 222). While intertextuality can refer to a relation between different sources and text, it can also be found within a single text. Rose (2012) argues that an image can be understood as a kind of discourse as well, as the way something is visually presented has the ability to make certain things more visible than others or represent something in a particular way (p. 191). Fairclough (1992) further speaks of horizontal intertextual relations whereby a dialogue can be identified between what proceeds and what follows in the chain of a text (p. 271). This is of course particularly relevant for moving images (e.g. video clips).

4.2. Method

While the literature review established what available evidence suggests the contributing factors to social silence and underreporting are, visual analysis was geared towards exploring the second part of the research question, namely, how key players in the space of DVAW prevention in the UK represent DVAW in public awareness campaigns aimed at addressing the issue of social silence and underreporting. The analysis was conducted in three concrete stages: 1) relevant discourse fragments (i.e. visual texts) were identified according to strict sampling criteria, 2) texts were analysed with a step-by-step approach outlined by Jäger and Maier (2016), in order to identify key themes and a typical sub-sample of discourse fragments, 3) an in-depth analysis of a sub-sample of typical discourse fragments was conducted.

4.2.1. Sampling

As briefly described in section 2.3, there are many actors in the UK who are active in the area of VAW or abuse in general. For this research I only mapped organisations that specifically focus on DVAW and are, apart from their organisational activities, also involved at a policy level, collaborating with the government to develop and implement national strategies to tackle the issue, hence are influencers at multiple levels. In addition, when mapping key players, police forces, municipalities and other government related actors were included. I subsequently conducted a search for visual texts from mass-media public awareness campaigns that were published in the UK during the past five years by all identified key players.

Sampling criteria

Considering the high level of media convergence today (i.e. ability to consume multiple formerly distinct media such as radio or TV on a single platform or device, or one medium on several different platforms and devices), it has become increasingly difficult to make clear distinctions between TV- or cinema-spots, or video clips circulated on YouTube and other social media platforms, and to identify through which medium visual texts were published initially (Dwyer, 2010, p. 4). For this reason, visual texts, be it moved images (e.g. video clips) or still images (e.g. posters), regardless of where or how they might have been published, were included in this study. However, campaigns with a focus on written text, audio or other non-visual media, such as social media campaigns

using hashtags without additional visual texts, newspaper articles, news segments, events, radio clips, promotional materials, etcetera, were excluded.

Any campaigns aimed at DV against children or men were excluded, as women remain disproportionately affected by DV and are therefore the main focus of this research. Furthermore, the issue of DVAW is prevalent across the entire population regardless of socio-economic background or age, so that campaigns focusing only on one sub-group (e.g. adolescents, the elderly, immigrant populations, particular religious groups or LGBT community) were excluded as well, although it has to be mentioned that only two campaigns focusing on sub-groups were found. Consequently, only campaigns targeted at ‘the general public’ focusing on DVAW were included.

Furthermore, only campaigns specifically aimed at issues around underreporting and social silence were included. Campaigns aimed at creating awareness around the different forms of domestic abuse (e.g. physical, sexual and psychological abuse, controlling behaviour and jealously, cyber-bullying, etc.) or other aspects such as the negative effect on children witnessing DVAW were excluded.

Interestingly, and this is relevant beyond the sampling process, some campaign texts had to be excluded even though they seemed to fit the sampling criteria at first, because the intent of the text or issue it was trying to address could not be determined with certainty, neither through looking at the text itself nor by additional campaign information published by the creators of the text.

For campaigns that fulfilled all the sampling criteria, only one had more than one visual text available. For all other campaigns included in the sample, campaigns consisted of one visual text only, which, in the vast majority (9/10), was a video clip. As a consequence, no further selection was necessary.

Sample size

Based on the above sampling criteria a total of ten visual texts could be identified, see Annex 1 and section 5.1. Rose (2012) states that discourse analysis “does not depend on the quantity of materials analysed, but the quality” (p. 199) and a great care for detail is necessary (p. 219). As Jäger and Maier (2016) suggest, the sample size for texts analysed should be determined by a saturation principle – saturation is achieved when key

themes or “arguments begin to repeat themselves” (p. 111/2803). I analysed all ten campaign texts, and based on this sample size, key themes could be identified very clearly and their repetition became obvious, see section 5.2., hence, data saturation was achieved. Furthermore, the sample size allowed me to determine criteria for typicality described in the analysis chapter, which further indicates an adequate sample size. 4.2.2. Operationalising Discourse Analysis

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, Jäger and Maier (2016) have developed a comprehensive Foucauldian approach to operationalise discourse analysis, summarised here, which I strictly followed when analysing the selected campaign texts listed in Table 1, in order to identify key themes and a typical sub-sample of discourse fragments (i.e. texts).

To start the analytical process, I undertook a structural analysis consisting of the following six steps, as proposed by Jäger and Maier (2016, p. 113/2846):

1. List all relevant discourse fragments (i.e. texts) including bibliographical information, notes about topics covered in the text, and genre.

2. Roughly capture the characteristics of texts on particular aspects of interest such as illustrations, layout, use of collective symbols, argumentation, as well as vocabulary and imagery.

3. Identify sub-topics or key themes and summarise into groups.

4. Examine with what frequency key themes appear, which ones are focussed on and which ones are neglected, are there subtopics that are conspicuous by their absence?

5. Are there any other discourse strands entangled? For example, is the DVAW discourse entangled with the gender equality discourse?

6. Combine findings from previous steps and summarise. Ideas should emerge for the detailed analysis of typical discourse fragments and for the final analysis. Based on this structural analysis, two typical campaign texts were identified by rating texts regarding their typicality according to defined criteria (Jäger and Maier, 2016, p. 120/2874). Criteria for typicality can be, for example, typical argumentation, typical use of collective symbols and representations, typical vocabulary or images (Jäger and Maier, 2016, p. 120/2874).

Then, as a second step, the sub-sample of two typical campaign texts were analysed in more detail. And in a third step, a synoptic analysis followed, to discuss discrepancies between available evidence and representational strategies deployed by key players in their campaign texts, and to ultimately unveil potential gaps and misalignments. Findings could potentially help to optimise how DVAW is represented, in order to drive meaningful social change.

5. Analysis

As discussed in previous chapters, the way something is visually represented not only creates meaning, it also has the potential to influence the way we think about something and therefore either perpetuates existing discourse or has the potential to influence or achieve social change. Critical discourse analysis is particularly interested in investigating structures of dominance and social inequalities (Wodak and Meyer, 2016, p.12). By examining the second part of the research question, which is how British NGOs and government agencies represent DVAW in selected texts of public awareness campaigns addressing social silence and underreporting of DVAW, I will analyse the discourse promoted by DVAW experts in the UK. Furthermore, the representation of DVAW identified in this chapter, when compared to available evidence, will allow me to unveil possible gaps and misalignment.

5.1. Selected campaign texts

Table 1 lists all campaign texts that were included in the sample and analysed. A more detailed version of this can be found in Annex 1. Interestingly, only in one case (i.e. UK Says No More) was there more than one text available from the same campaign – all others were campaigns consisting of one text only. In the vast majority (8/10) this visual text was a moving image (e.g. video clip). The Inspire Hope – Be a voice text is the only still image – a poster.

Table 1: Selected campaign texts for discourse analysis

1 Name: Inspire Hope - Be a voice Year: 2012

Organisation: Domestic Violence UK Text type: Poster

Link: https://www.prlog.org/11865179 - inspire-hope-be-voice-campaign-aims-to- shatter-silence-surrounding-domestic-abuse.html

2 Name: Don’t cover up – How to look your best the morning after

Year: 2012

Organisation: Refuge Text type: video clip Link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d -XHPHRlWZk

3 Name: Emma’s story - Christmas Campaign Year: 2012 & 2016

Organisation: Live Fear Free by the Welsh Government

Text type: video clip

Link:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= TUY8APLxnKA&feature=player_embedded 2012Creative+agency%3A+%3F

4 Name: Final Minutes Year: 2014

Organisation: National Centre for Domestic Violence

Text type: video clip

Link: https://vimeo.com/98629065 5 Name: Unpunished

Year: 2015

Organisation: Women’s Aid & Football united

Text type: video clip Links:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b2M FsmpbAlA

6 Name: Look at Me Year: 2015

Organisation: Women’s Aid

Text type: interactive transforming poster Link:

https://www.womensaid.org.uk/what-we-do/blind-eye/

7 Name: Stop the routine Year: 2016

Organisation: National Centre for Domestic Violence

Text type: video clip

Link:https://vimeo.com/189123911 8 Name: Who’s pulling your strings

Year: 2016

Organisation: South Yorkshire Police Text type: video clip

Link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cukl Nf66T0k

9 Name: UK Says No More Year: 2016 (ongoing)

Organisation: Hestia in partnership with No More

Text type: video clip Link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_c ontinue=2&v=4gtC2CW-Ljs

10 Name: Signal for Help Year: 2017

Organisation: Bede House Text type: video clip Link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_YO 4zxpYB8

5.2. Discourse Analysis of campaign texts

All ten selected visual texts were carefully analysed according to the six steps outlined in the methodology chapter section 4.2.2. Detailed stock was taken of each visual text, to identify representational elements, collective symbols and key themes. Since the majority of texts analysed were video clips, I wrote a detailed synopsis for each clip to facilitate analysis and capture images used as well as the spoken and written word, see Annex 1. Only one of the texts used drawing/cartoon for the imagery (Who’s pulling your strings) and two texts used celebrities or known protagonists (UK says NO more and Don’t cover up). Key themes such as the portrayal of violence, victim, perpetrator and

bystander, as well as more nuanced sub-topics, started emerging very early on. Results presented here are summarised r with my focus being predominately on the discussion of results.

Representation of violence

The actual act of domestic violence, whereby a perpetrator attacks their victim, only featured in three texts, and in all texts the violence shown was physical (e.g. beating, pushing) as opposed to emotional or verbal (e.g. controlling behaviour). Furthermore, the violence was hinted at or strongly implied, rather than explicit. The most explicit display of physical violence featured in Stop the routine, which shows the struggle of a victim and perpetrator over nearly two minutes. However, the act of violence is staged as an artful dance, and albeit violent, the perpetrator only makes body contact with the victim occasionally, pretending to harm her as part of the choreography. In the other two texts the act of violence is partially taking place off screen and implied through sounds and furniture falling over. More texts (4/10) opted to represent abuse or violence through a placeholder, by showing bruised victims. Interestingly, all the bruising shown in the texts is either on the woman’s face or neck (e.g. black eye, split lips, strangulation marks around the neck). Additionally, all victims are depicted as young and attractive. Showing an attractive woman with violent bruises on her face – a ‘broken beauty’ – maximises the shock effect.

While all texts used the word violence in written or spoken form, three texts did not portray violence visually at all. Showing the act of violence or alternatively bruises as a collective symbol for abuse and violence seem to be a common form of DVAW visual representation to create an effect of shock and to emphasise the seriousness and severity of the issue.

Representation of the victim

All but one text (UK says NO More), feature a victim of DV as one of the main subjects of the text. It is striking that in all nine texts showing a victim of DVAW, the victim is represented in a very isolated manner with no visible contact to the outside world or society. In three texts, Inspire Hope – be a voice, Look at me, and Who’s pulling your strings women are shown in front of a black background with no reference to their whereabouts. In the other texts, women are home alone with the perpetrator. The homes shown in most cases are furnished scarcely, if at all (e.g. Break the routine), often in white and grey, or other cold and dull colours. Showing victims in such an isolated manner, implies that victims have no social circle or are not part of society as a whole. It frames the issue of DVAW as a personal, private issue, happening behind closed doors with no witnesses and no help in sight or way out, at the mercy of the perpetrator. Interestingly, four texts still assume victims to be one of their primary audiences, by addressing them directly, asking them to stop the violence by speaking up or seeking help from specialised services. The visual representation of the victim’s situation and the call to action are contradictory in that the situation shown seems hopeless, isolated and highly dangerous, but then the victims are asked to summon the courage to speak up and break free, when the visual representation offers no encouragement or hope. In two texts the victims take initiative and ask the viewer directly for help – in Signal for help unsuccessfully, as she gets caught and beaten up as a result of her help seeking. In only one text, Break the routine, is the victim successfully standing up to her abuser, seemingly without any outside help. This is the only text that provides us with a positive outlook. In all the other texts where victims are represented they are shown in a passive role.

All texts featuring the victim depict women in their thirties, who are dressed modestly and casually, look rather plain, wear little to no make-up and no jewellery. This is in stark contrast to the sexualised manner women are often represented in mass media and advertising.

Representation of the perpetrator

Only three texts explicitly show the perpetrator. In two texts (Signal for help and Stop the routine) the perpetrator’s face can be seen, and in Unpunished we only see the perpetrator’s torso. Only in Stop the routine is the perpetrator in full view for most of

the video. In another three texts the perpetrator is merely present on the periphery. He is represented as a lurking threat just beyond what we can see. In Don’t cover up we hear a door banging somewhere in the house that startles the victim we can see, in Who’s pulling your strings the perpetrator is represented in the form of strings tied to the woman’s arms and legs, or as the invisible puppet master, and in Final Minutes we can only assume the perpetrator is watching TV in the next-door room. In the remaining four texts the perpetrator does not feature at all, except through the bruises he left on his victim. By focussing the representation of DVAW on the victims (i.e. the symptoms of the issue), perpetrators (i.e. the cause) are not only excluded from the conversation, but also to a certain extent released from their responsibility. This could further foster attitudes of victim blaming and continue to foster a climate of social acceptability of DVAW. To a certain extent, DVAW is framed as a women’s problem that the general public has to solve by speaking up on behalf of victims. This implies that the victim needs to take action, the general public needs to take action, but keeps the perpetrator in a rather passive role, when the core of the problem lies with the act of abuse, with the root cause being the perpetrator’s behaviour.

Source: Perpetrator in “Break the routine”

Representation of bystanders

Three texts actively portray bystanders: 1) In Emma’s story her parents who have remained silent about her abuse are at the centre of the story, 2) Look at me engages bystanders in real time through facial recognition technology and cameras, and 3) UK says NO More exclusively addresses and features bystanders. These are examples how the focus can be taken away from the victim when framing DVAW and give the issue societal context. In addition, UK says No More is the only text specifically debunking some misconceptions regarding DVAW and specific public attitudes that need to be addressed and changed.

Call to action and contact details

All texts analysed include some sort of call to action, typically at the end of the video clip. Phrases such as “stand up”, “speak up”, “call”, “go online”, “talk to us”, “join us”, and “stop it” are used to ask viewers to take action. However, to achieve the desired behaviour change amongst the general public and victims to report DVAW and end social silence, most texts lack clear instructions regarding what specifically one must do. Only three texts provide very clear instructions what to do to follow the call for action and how to do it by providing a phone number to call. Four texts missed the opportunity to provide a clear and actionable ‘call for action’ regarding what to do and how to do it. Some texts, in fact, give contradicting messages or messages to different audiences that then dilute the intended key message of the text. Don’t cover it up, for example, asks victims to no longer hide their bruises and abuse, but does not provide further information to victims what they are supposed to do after reporting or how they can report the abuse safely. Instead viewers are asked to “share this video” and “help someone speak out”, but again, it is not specified how. In other words, two different audiences are addressed, but neither given clear messages how they can do what is asked from them. While most texts (7/10) provide a website where people can find more information on the topic, it is questionable whether this would prompt further action. Four texts place the responsibility to act solely on the victim, whereby six texts clearly put that responsibility on the general public, and two texts on both victims and bystanders. Putting the responsibility of action on the victim alone, further emphasises the language of isolation.

Discourse strands entangled with DVAW discourse

As most texts are framed at an individual level with very little societal context, not many entangled discourse strands could be identified. Unpunished was the only text framing DVAW within the human rights discourse. None of the texts make reference to gender inequality, for example. Other texts made reference to the festive season or sportsmanship to show DVAW in stark contrast to characteristics associated with the former (i.e. family, celebration and love or fairness and obeying rules).

Typical texts – Sub-sample

In order to conduct a more in-depth analysis of a sub-sample of texts, the key themes identified above were used to rate texts regarding their typicality of representing DVAW. Criteria classified as typical were the following:

a) Display of either physical violence or the result thereof (i.e. inflicted injuries) b) Predator is not visible

c) Victim is isolated, without social context (beyond immediate family) d) No vision how life could be without DVAW

e) Responsibility to act is placed on bystanders/the general public

f) Call to action including contact details (either website, phone number or both)

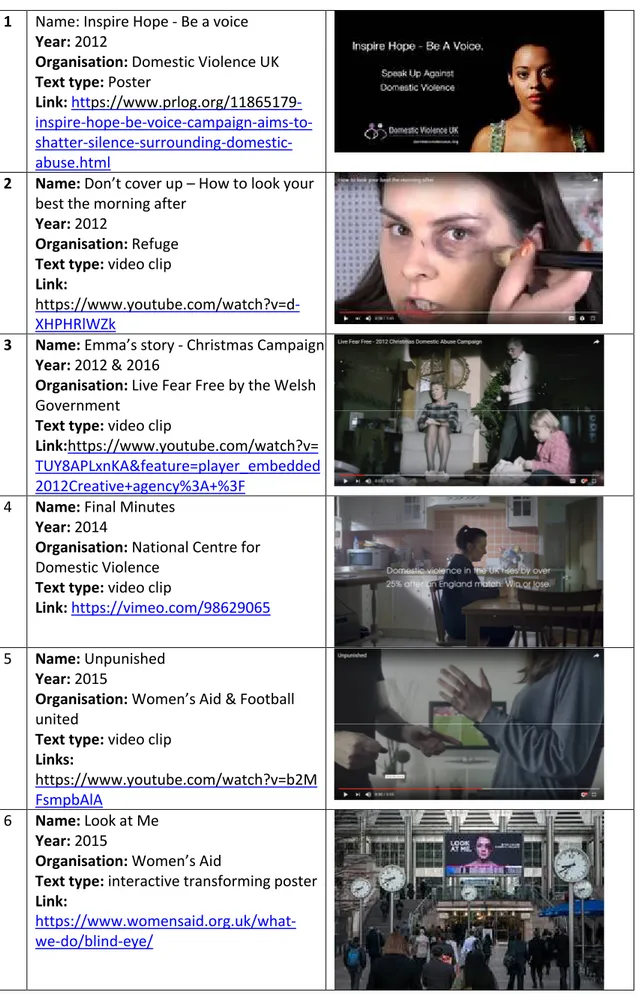

Table 2: Ranking of typicality*

Text a) b) c) d) e) f) Total

Emma’s story 1 1 1 1 1 1 6

Don’t cover up 1 1 1 1 0,5 1 5,5

Unpunished 1 0 1 1 1 1 5

Signal for help 1 0 1 1 1 1 5

Inspire hope 0 1 1 1 0,5 1 4,5

Look at me 1 1 1 0 1 0 4

Final minutes 0 1 1 1 1 0 4

Who’s pulling your strings 1 1 1 0 0 1 4

UK says NO More 0 1 0 1 1 1 4

Break the routine 1 0 1 0 0 1 3

*1= criteria fulfilled, 0= criteria not fulfilled, 0,5= criteria partially fulfilled

5.3. Sub-sample analysis

The two texts ranked as most typical are further analysed in this section to identify finer detail regarding how the discourse fragments create meaning. What effects do the texts create? What symbols and clichés are used? What concepts of society are represented? What argumentation is used? Foucauldian aspects such as subject, power, knowledge, claim of truth, and intertextuality are of particular interest.

Emma’s story

Emma’s story is a Christmas campaign. The discourse fragment tells the story of Emma’s parents who, despite knowing of their daughter’s abuse, have never spoken up about it. This time they did not say anything, because they did not want to “spoil Christmas for Emma or her daughter” (Emma’s story, 2012, 0:05-0:12). We see Emma’s parents with their granddaughter at Christmas (screen shot (SS) 1). Emma is not there. They now regret not having spoken up, but it is too late, Emma is in hospital and her daughter, accompanied by her grandmother (SS2), brings her a Christmas gift (SS3). Emma is badly bruised (SS4). Sad Christmas music is played in the background throughout the clip. A female voice-over says: “If you see the signs of domestic abuse, don’t just wish for things to get better…they won’t! Call 0808 80 10 800 or go online now” (Emma’s story, 2012, 0:18-0:28).

SS1 SS2

SS3 SS4

The absence of the perpetrator is striking. Not knowing where he is or if he was held accountable for what he did to Emma creates an air of a lurking threat. Even though the perpetrator is entirely invisible, he seems to hold power over the subjects shown in the video. Emma’s parents are represented as passive bystanders, who seem to care more about keeping the family peace than their daughter’s wellbeing. The responsibility to act is very clearly placed on Emma’s parents. Emma herself is portrayed passively and holds no agency.

Christmas is typically understood as a time for families to come together and celebrate, a time of love and peace. Framing Emma’s story in this context creates a particularly strong effect – not even Christmas could keep the perpetrator from beating Emma up. It further emphasises the effect of DV and burden on families. Despite Emma being in hospital and despite Christmas ‘being spoilt’ anyways, Emma’s parents “still hadn’t said anything” (Emma’s story, 2012, 0:03-0:05). Representing Emma’s parents so passively, makes them appear cowardly and fosters feelings of guilt, and further emphasises the absurdity of remaining silent. This representation reinforces the clear message given at the end of the clip to bystanders of DVAW to speak up and not wait and hope for things to get better. Overall, the video is coherent and effectively conveys a clear key message to encourage people to speak up rather sooner than later and end social silence and underreporting.

Don’t cover up

Don’t cover up is a video clip disguised as a regular YouTube video by Lauren Luke who is known for her make-up tutorial posts. This video shows her with a bruised face however (SS5, SS6), and she explains to viewers how black eyes and other bruises such as split lips can be covered up with make-up in a step-by-step make-up tutorial. Throughout the tutorial she mentions that she has had a “rough time” (Don’t cover up, 2012, 0:15), how to cover up bruises from being “pushed hard against the coffee table” (0:38-0:42) and splits “caused by any watches or rings” (01:07-01:09). Then one can hear a banging sound from somewhere else in the house. Lauren looks terrified, turns to the computer and closes the lid. White text on black background appears: “65% of women who suffer domestic violence keep it hidden.” New slide “Don’t cover it up” then “Share this and help someone speak out.”