Designing expressive

typing experiences

Alexander Grövnes

Alexandergrovnes@gmail.com

Interaktionsdesign Bachelor 22.5HP Spring 2020

Supervisor: Jens Pedersen

Abstract

The expressive nature of typing has been mostly neglected in research. The possibilities of our full expressive selves are not included in typing experiences.

The aim of this thesis is to explore the expressive qualities and experiences of typing and open up new opportunities and possibilities for interaction designers. To fulfil this aim, the qualities of typing itself as a medium are investigated, as well as how handwriting can be used as inspiration and guidance to investigate the potential expressive qualities of typing.

The result of this investigation showed how typing possesses personal, behavioral and emotional expressions. Additionally, the investigation lead to the discovery of how typing possesses impressionable experiences. These impressions changed the feeling while typing, could make the user write in a particular way and be used as an expressive tool to another person.

Keywords: Typing experience, Expression, Impression, Handwriting.

Acknowledgements

I would first like to thank my supervisor Jens for guiding me with valuable assistance in the right direction and being encouraging throughout the process. I also want to thank the participants for their time and effort in the evaluation sessions, making this project reach new possibilities.

Finally, I would like to thank my girlfriend for always being supportive, caring and encouraging, especially throughout this thesis work.

Table of contents

Abstract ... 2

Acknowledgements ... 3

Table of contents ... 4

1 Introduction ... 5

1.1

Aim ... 5

1.2 Delimitations ... 5

1.3 Research question ... 6

1.4 Reading guide ... 6

2

Theory ... 6

2.1 Interactive systems ... 6

2.2 Typing as a medium ... 7

2.3

Related work ... 11

2.3.1

Expressive typing through pressure ... 11

2.3.2 Expressive Keyboards: Enriching Gesture-typing ... 12

2.3.3 Expressive mobile touch keyboards ... 13

3 Methods ... 14

3.1 Research through design ... 14

3.2 Interaction-driven design ... 14

3.3 Sketching and prototyping ... 15

3.4

Evaluation and interpretation interviews ... 16

4

Exploration ... 17

4.1 Reimagining typing ... 17

4.2 The sketches ... 18

4.3

The next step ... 22

4.3.1

Expressional experiments ... 24

4.3.2 Impressionable experiments ... 27

4.4 Interpretation interviews ... 29

4.5 The expressive qualities of typing ... 33

4.6

The impressionable qualities of typing ... 35

5

Discussion ... 36

6 Conclusion ... 37

7

References ... 39

1 Introduction

Handwriting is a medium of human communication and the source of some of the strongest self-expressions. Writing is to think, analyze, express feelings, desires, and beliefs. Handwriting involves both a conscious and an unconscious expressive process. Being consciously expressive means that the written letters reflect the specific way we wanted to write the text. Being unconsciously expressive means that the text expresses individuality through your personal behavior, patterns, and habits of writing (Huber & Headrick, 1995).

The paradigm shift from handwriting into the era of typewriter machines resulted in writing being deprived of the expressive aspects of handwriting. Typewriters made writing rapid and easy to read but sacrificed personal expressiveness.

Despite the importance of self-expression through writing, our digital writing experience is of a static nature. The visual representation of the typing action and the response of identical-looking letters we see on the screen occur without any kind of expression.

In response to the non-expressive capabilities of digital writing, I intend to explore the potential expressive qualities of typing experiences. I am interested in what qualities typing could possess and how we can utilize a digital environment. How do we experience and interpret these qualities? And how can interaction designers use these tools to design richer and more expressive typing experiences?

1.1 Aim

The aim of this thesis is to explore the expressive qualities of typing experiences. In order to fulfill this aim, I look at the qualities of typing itself as an expressive medium and use handwriting as inspiration and influence to investigate potential expressive qualities.

Expression is a term that can be rather abstract and to clarify what I mean with expression in the context of typing, I will illustrate it through handwriting. In handwriting, we could look at a person’s written letters and see patterns and habits of that particular person’s handwriting. This can be seen as their personal behavioral expression. In handwriting we can also write the text in a particular way and convey particular emotions in the writing; this can be seen as intentional or explicit expressions. The starting point of this thesis is to explore expressive typing qualities from explicit and implicit expressions.

The thesis will concern typing as an interaction and not the feeling of physical or digital keys. However, typing involves both tangible and intangible interactions which might change both typing behavior and experience from one artifact to the next (Jung & Stolterman, 2011). My thesis will investigate the actions you put into the keyboard and the response from the system. Furthermore, how this interchanging relation between action and response works in typing experiences and how we can experiment with new forms of expressive typing.

1.3 Research question

The overall aim of this thesis is to experiment with expressive typing. I am interested in what types of expressive qualities typing can possess and how we can enable these qualities using the capabilities of a digital artifact. This leads to the open and explorative research question:

-How can we experiment with expressive typing experiences?

1.4 Reading guide

This thesis focuses heavily on the experience of typing and to communicate this experience, illustrations and images are limited in their ability to do so. Therefore, links to both videos demonstrating the experience as well as links to the actual prototypes will be provided. I encourage the readers to press the links and experience, to a fuller extent, what I will be discussing. Remember that the experiments are prototypes and not finished products. Also, important to note is that the experiments are distributed through a website called Glitch.com, which means the site might take a few seconds to load when entering it and could potentially crash. If this happens, you have to reload the page and, in some cases, wait sometime before re-attempting.

2 Theory

This chapter presents the theory used in different phases of the exploration phase. The first section introduces the fundamentals of interactive systems in relation to the expression of a user. The second section informs about the fundamentals of handwriting as an expressive process and the expressive possibilities of digital text. The third and last section provides an overview of relevant concepts and projects.

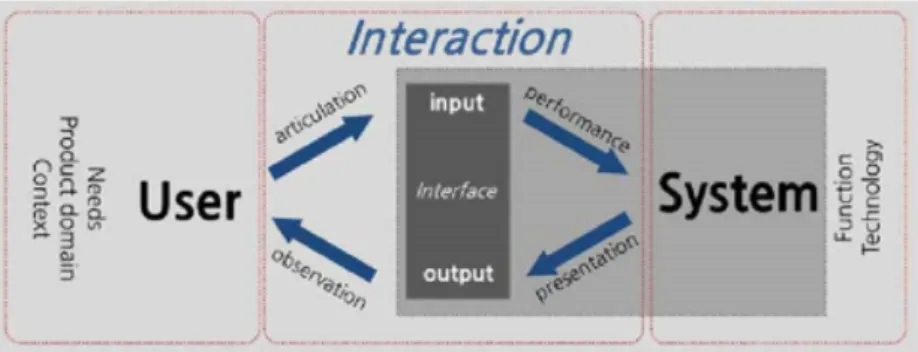

Within any interactive system, there is an action and a response from the system. The response also referred to as feedback, is the system informing the user that their action was registered (Wensveen et al, 2004). However, there is a difference between the system acknowledging your action and reflecting on how you performed the action. Wensveen, Djajadiningrat & Overbeeke (2004) address the importance of freedom in interactions when expressing emotions to an interactive system. They mean that the system needs to respond to the user in a way that allows dynamic and expressive responses to the user’s actions. Wensveeen et al. argues that to achieve a system that responds to your behavior and emotions, also called an emotionally intelligent system, the coupling between action and response need to be unified on multiple aspects that lead to representing the behavior and expression of a user’s action. In the case of typing, the missing aspects are dynamics (speed, acceleration, force) and user expression. In this thesis, I will explore how a system can achieve an experience where the coupling between the system and the user reflects a user’s behavior and expression. Figure 1 visualizes such interaction.

Figure 1 Structure of interactive systems (Maeng et. al, 2012)

Typing experiences and input

Typing interfaces are integrated into most computing or mechanical products that surround us. However, typing does not respond to our writing behavior or the emotional information of the user's input. The keyboard measures each individual key press and present identical letters that do not give any sense of individuality or expression.

In this thesis, I will use typing input such as the measurement of the speed of typing and the amount of pressure used on a key. These types of input generate a wider range of data of a user as well as extracts more information about the dynamic behavior of the user. More about how speed and pressure measurements will be used and captured will be discussed in section 4.1.

2.2 Typing as a medium

After having examined how an interactive system needs to respond to the user’s dynamic and expressive actions in regard to enabling expressivity in typing and how we could introduce more depth of the user’s input, I needed

to understand the fundamentals of handwriting as an expressive process and understand how typing can be its own expressive medium. I looked at the fundamentals and the possibilities of handwriting as it possesses many expressive qualities and can help navigate the complexities of human thoughts and emotions in writing.

Handwriting as inspiration and guideline

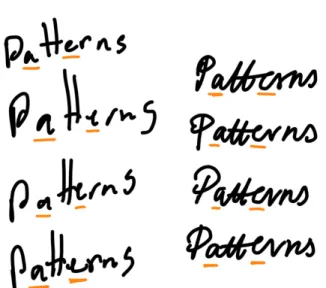

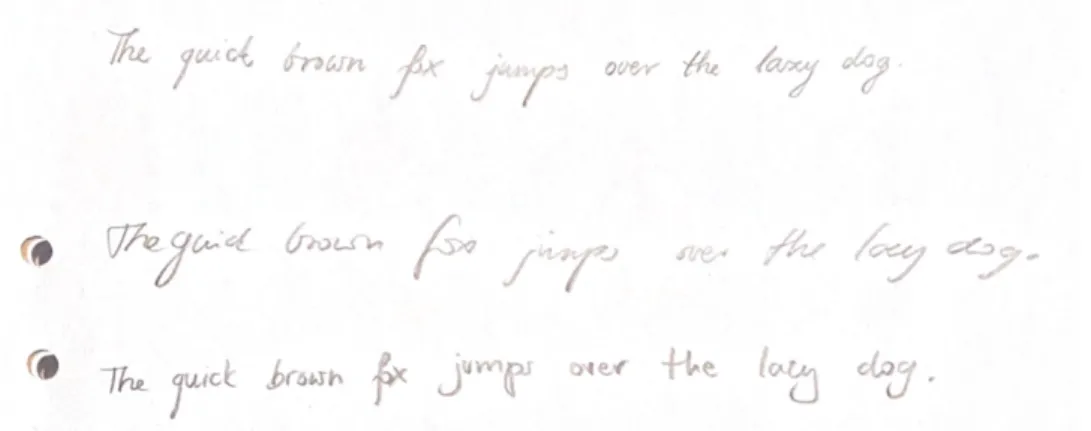

When exploring the possibilities of expressive typing it was important to distinguish between two mindsets of writing: conscious and unconscious writing. Conscious writing can be seen as our intensions or decisions while writing. We are actively trying to write something in a particular way. This is most visible in handwriting. Huber and Headrick (1995) proposed that a consciously executed handwritten letter have bigger changes in the shape and size of letters and the overall text. I could for example write carelessly or gently and the text’s overall look would be perceived that way. In figure 2, we can see the difference between a quickly and carefully written text.

Figure 2. Comparison between handwritten texts. Where both are consciously executed.

In contrast, Huber and Headrick (1995) proposed that unconscious writing contains smaller changes in letters and the overall text. Unconscious writing can be viewed as our natural behavior or less active decisions. This is when we write something but do not consciously think about how we want to write it and the text reveals patterns and habits of the person who wrote it (Figure 3). For a user to acknowledge the unconscious writing, one has to examine the written text after having written it. It is then the patterns of our typing become visible to us.

Figure 3. Handwriting patterns and habits of different writers

The conscious and unconscious execution of handwriting is described as an act that is evidential of behavior patterns, known as habits (Huber & Headrick, 1995). Huber & Headrick describe how handwriting can be used as an identification process by comparing and evaluating writing habits. The authors proposed that each individual person has their own characteristics or qualities of handwriting and that these are simply manifestations of the habits formed. These habits become less varied as the writer improves their skill and control, although the natural variation is inevitable in the text. Huber and Headrick describe natural variation as: “…the imprecisions with which the habits of the writer are executed on repeated occasions.” (Huber & Headrick, 1995, p. 97) The authors continue to say that the range of natural variation varies with the skill of the writer and the specific letters being written (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Natural variation visible in two writers’ letters.

This means that in handwriting, unconscious actions are the habits and behavior of a person that lead to natural variation in letters, while conscious actions are about active decisions that involve a sense of control and skill. I will try to mimic the perspectives of conscious and unconscious writing when typing digitally. I will examine writing from the perspective of conscious writing and how control is needed to allow conscious writing, as well as how unconscious and conscious writing leads to habits that form variations in letters, also referred to as natural variation. Unconscious and conscious writing seem to be the fundamental part of writing when trying to achieve expressivity on both a behavioral- and emotional level.

Huber & Headrick (1995) compiled a list of how different handwriting patterns and habits contribute to various circumstances and conditions the writer is experiencing. These circumstances, conditions, and experiences are part of the potentially expressive qualities I hope to achieve when I will explore expressive typing in section 4.

The authors describe how handwriting habits can be express when a writer is paying close attention to what they are writing; If a writer is concentrated on the act of writing this means that the writing is less fluent and slower. It is also possible to see if the writer wrote the text carelessly by examining the execution. A carelessly written text can decay to a scribble due to haste, carelessness, or poor writing circumstances. Headrick and Huber additionally describe how handwriting habits can inform us about the writers’ health and mental conditions. If the writer has changes in health conditions this might affect the fluency of writing and result in loss of

control and more random movement and speed. Writing by people who are under emotional stress, seems to affect the fluency of writing in contrast to the effects mentioned above, resulting in a more conscious, careful, and detailed effort.

Text expression and communication

Now that we now what expressive possibilities typing could possess, I needed to investigate approaches for how digital text could surpass its limitations as a seemingly static and non-expressive output. In the next section, different text expressions and communication possibilities will be presented.

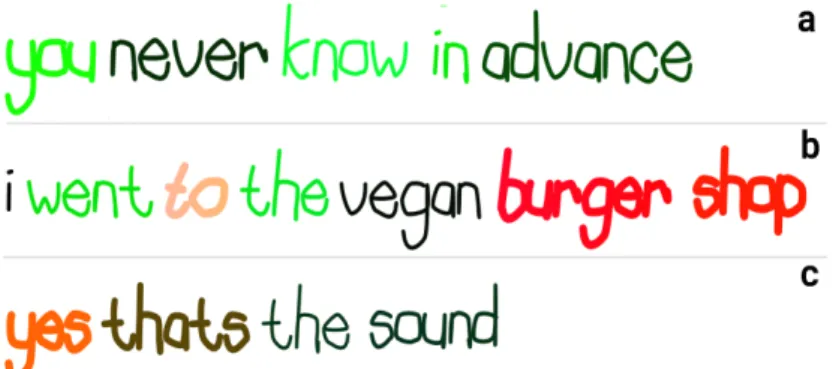

Various techniques and forms exist in communicating text. In regard to expression, the potential of animated text has been reported to elicit certain emotions, such as joy, surprise, and excitement when used in typing experiences (Tikkanen, 2016).

One form of animated text is kinetic typography. It has been researched due to its ability to convey emotions, personality, and tone of voice. Kinetic typography refers to texts that can dynamically change their appearances, such as size, shape, and location. Bodine & Pignol (2003) explored the potential of kinetic typography in relation to improving expressive communication in instant messaging. Bodine & Pignol built an application for instant messaging and during testing discovered that kinetic typography can dramatically change people’s ability to convey emotions. Similarly, Wang, Prendinger & Igarashi (2004) used kinetic typography in combination with emotional information, collected from the user through physiological sensors, to visualize the affective state of a user in a chat application. Their approach resulted in users’ ability to determine a partner’s affective states, such as nervousness, sadness, and excitement. Wang et al. (2004) also explain how typing speed could be used in detecting when users were anxious or in a hurry, as users typing speed tended to increase while writing under those conditions. This way of dynamically changing the appearance of texts seems appropriate in the context of expressive writing. We know that handwriting involves letters changing from letter to letter and computer letters that can dynamically change their appearance from letter to letter seem to be an appropriate approach for expressing variation (habits) as well as conscious decisions such as expressing certain emotions with the letters.

2.3 Related work

After investigating handwriting and digital text. The next step was to look at relevant concepts and projects. I found that most research exploring typing expression focused on explicit or conscious expressions that could be used in direct messaging contexts.

Inspired by hand-writing and non-verbal communication. Iwasaki, Miyaki, and Rekimoto (2009) proposed a new way of measuring key typing pressure using an accelerometer embedded in laptops. Their concept explored typing pressure for sensing non-verbal communication aspects of key typing and proposed three application ideas that utilize typing pressure. The first proposal was applications for rich text expression. By using this application seamless and real-time text expressions could be realized. Instead of users having to change font or size after typing it was possible to change it while typing (Figure 3). Meaning pressure could be used as a way to consciously control changes in the text. The second proposal was applications for new user interfaces; mode switch typing. As the name suggests this could be used to assign commands to each key and would activate when the user presses the key strongly. One of their examples showcased commands to change from normal to italic text mode. The final proposal was the use of pressure as authentication. Imitating another person’s typing pressure is difficult and is therefore an option as an authentication method. Pressure would result in a similar authentication level as handwriting-signatures according to the authors. This meant that pressure could add individuality when typing.

Figure 5. Rich text expression (Iwasaki, Miyaki, and Rekimoto, 2009)

Iwasaki et al. experiment showcased how it was possible to decide when you wanted to initiate change in the text dynamically. However, their research did not fully go into detail about the experiences of pressure typing, which made it hard to determine, what they found about pressure typing and how it would fit my intensions of the thesis.

2.3.2 Expressive Keyboards: Enriching Gesture-typing

Alvina, Malloch, and Mackay (2016) introduced Expressive Keyboards, an approach that takes advantage of user input, otherwise not used, in gesture typing. They analyzed gesture typing separately from the regularly used recognition process and use the expressiveness of this extra gesture input to enable users to express themselves through personal style and intentional control. The authors approach is similar to my own, by how they are using otherwise disregarded user input. As well as investigating conscious or intended expression.

Mackey et.al (2016) conducted experiments to test whether it was possible for users to deliberately control their output. They found out that it was possible to vary their output deliberately when expressing emotions or when writing to different recipients. The authors furthermore wanted to explore expressive keyboards in a more realistic setting and developed a chat application that rendered a dynamic font that changed shape and colors depending on the gesture features.

Figure 6. Expressive gesture application (Alvina, Malloch and Mackay, 2016)

While their experiments focused on explicit output, they believed implicit output could be interesting and enrich social communication. Authors stated that a user might not intentionally control their output, yet the output could reflect the writing process. This insight is one of the main focuses of this thesis.

2.3.3 Expressive mobile touch keyboards

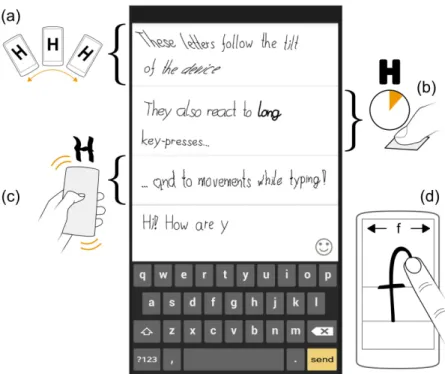

Inspired by previous research on expressive typing. Buschek, De Luca & Alt (2015) developed a dynamic font for mobile phones that changed letters' visual appearance based on the writer’s behavior and context. To capture the context-based influences of a user they measured device orientation and movement and mapped the data to the dynamic font (Figure 5). To enable the personal style of letters they captured users' touch targeting behavior and touch pressure and mapped the data to the dynamic font (Figure 5). These captures resulted in variation in letter appearance and the variations in the text informed users of other users’ behavior and contexts. Buschek et al. (2015) conclude their research by explaining how participants experienced dynamic font variation and sharing insights to inform future work. The authors stated that the system made it possible to elicit creative usages in chats and how users’ conscious changes in the text need to be understandable or adjustable. Furthermore, the system should also display a high degree of variation of letters or a lower degree of variation depending on the situation and recipients’ feedback.

Figure 7. Font personalization concept and prototype (Buschek, De Luca and Alt, 2015)

The main difference from Buschek et al. (2015) research and my thesis is that I use a physical keyboard to capture behavior, and context, Buschek et al. (2015) used a mobile device. This led to different approaches to what is appropriate to consider when deciding on how to capture data. The similarities lie in both parties wanting to achieve behavioral expression and reveal context-based information about the user. However, the way we approach context-based expression is different. Buschek et al. (2015) tried to express the outside forces, such as walking or laying down, of the user’s conditions. While my aim is to capture the users’ writing patterns and habits and in so revealing contexts and circumstances about the user.

3 Methods

3.1 Research through design

Zimmerman, Forlizzi and Evenson (2007) proposed research through design as a method for generating knowledge through an explorative design process. According to the authors, such an approach allows researchers to identify opportunities for new technology or advancement of current technology as well as help researcher discover unexpected effects to a specific problem space, context, or specific target group. The contribution of such research becomes a prime model and with each new contribution continuing the conversation of the explorative research. This method and model reflect well with the goals of this thesis.

The approach of Interaction-driven design, proposed by Maeng et al. (2012) argues that designers can focus on users’ input behavior and feedback from the system’s output, the interaction, instead of more traditional technological-driven and user-driven approaches when developing products. User-driven approach starts with users’ needs from a specific context. Technology-driven approach starts with the possibilities of a certain technology. The interaction-driven approach, on the other hand, focuses on the interactive process that is not part of users’ needs or technology. Maeng et al. alternate approach to product development argues that exploring specific interactions and their qualities can uncover potential functions, needs and applications by initially disregarding users’ needs and technical possibilities. The approach of interaction-driven design resonates well with my own intentions and approach for this thesis. Focusing on the user’s input behavior and the feedback the system provides is important in my process. However, the goal is to investigate the expressive qualities the interaction of typing possesses. While the approach of interaction-drive design is in line with my process it is not a mirrored approach and outcome. Interaction-driven design examines an interaction by itself, isolated from contexts and agendas, resulting in new knowledge about the specific interaction that can then be implemented in user-driven approaches. In comparison, my methodology started similarly with evolving the capabilities of a specific interaction, namely typing, and then during the process developed into the subject of expressive interactions. Meaning the scope and focus of the thesis changed into a more specific way of interacting with typing than the broad focus described by Maeng et. al. in their paper.

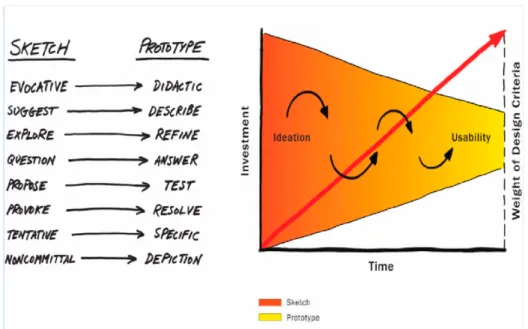

3.3 Sketching and prototyping

Research through design and interaction-driven design appears to be appropriate methods for generating knowledge within the context of my thesis. However, I still need methods that help me develop and explore expressive typing experiences.

Approaches within interaction design for generating concepts and ideas are usually created or built upon through sketching and prototyping. Sketching is a method aimed to materialize design thoughts and ideas. Once materialized, sketches help designers visualize and articulate their ideas, creating a dialogue between the sketch and the creator. Resulting in furthering of the design process and the manifestation of new ideas and sketches (Moussette, 2012). Prototypes are quite similar to sketches, aimed to manifest design ideas into an artifact that users can interact with. Buxton (2007, pp.139) suggests that sketching and prototyping are concentrated at different stages of the design process. At the beginning, where there are uncertainties and a lot of different concepts to explore, sketching dominates the process. While prototyping is essential at the later stage of the process, where things are converging, and we have more defined goals and concepts. The objective of this thesis focuses on finding and exploring the expressive qualities of typing which requires a more open and explorative approach in

the early stages of the design process. I have therefore proceeded with Buxton’s suggestions in my exploration phase. However, as we move further into the process, the line between sketching and prototyping becomes blurred.

Figure 8. Difference between sketching and prototyping (Buxton, 2007)

3.4 Evaluation and interpretation interviews

Evaluation

The evaluations in this project were conducted to collect detailed data on typing experiences. The experiments are divided up into two groups of six experiments per each phase of the design process. The first six are evaluated by me and the next six are evaluated by four participants. The first six experiments, that were evaluated by my myself are early sketches and required a close first-person perspective as it gives direct access to attention to detail and deeper articulation and understanding of the experience in relation to exploring expressive typing. Expressing the experience and details from a first-person perspective of the experiments was important in regard to the objective of the experiments, which will be further explained in section 4.2.

Interpretation interviews

The second phase of the design process that included the six other experiments was evaluated by four participants. The participants were invited to digital sessions due to the circumstances of Covid-19. My plan was to involve the participants in a group session, where participants can share, compare, and discuss the expressive qualities of each experiment. However due to the circumstances of Covid-19, where participants changed their daily routines and schedules resulting in the inability to participant online all at once. As well as time restraints of the thesis, the interpretation

session could not be conducted as a group session. Individual sessions were conducted but since I wanted each participant to learn from other people’s perspectives and further explain their experiences as described by Muratovski (2015). I repeated and quoted other participants' answers in the individual sessions.

This approach made it possible to capture first reactions unaffected by other people and the benefits of participants being able to moderate their views in regard to other participants' perspectives, which lead to a more elaborated understanding of the expressive qualities each user had experienced.

4 Exploration

In order to explore the expressive qualities of typing and give the user more expressive means similar to the possibilities of handwriting, I needed to address two issues. In the first set of experiments I try to address the limitations to expressiveness while using a keyboard and digital text. In the second set of experiments I try to provide more meaningful and distinct expressions from the perspective of the reader and writer of the text.

4.1 Reimagining typing

In order to achieve the implicit and explicit expressions. I needed to include two distinct features of handwriting. These two fundamental components of handwriting are variation in letters, that lead to expressing patterns and habits of a person, and enabling a sense of control when writing letters (Huber & Headrick, 1995). However, considering Huber & Headrick (1995) described writing by hand, it is not wise to assume that the same level of variation and control can be achieved in a digital environment. To understand how typing in a digital space could have similar expressive qualities as handwriting, I needed to investigate how to work with the limited factors of keyboard inputs as well as the limited qualities of digital text.

The keyboard

One of the main challenges in enabling user expression when typing appears to be how we currently measure user input. For instance, a keyboard's ability to measure the users’ input is far less extensive and sensitive than handwriting as it involves complex motor skills and movements of the hand. Computers detect key presses made on the keyboard but do not measure other input values made by the user. Additionally, to measure keypresses a keyboard can use the speed and pressure inputs of typing.

As previously mentioned in section 2.1, pressure will be used in this thesis as an input to contribute to a wider range of data on the user. Pressure will be captured by measuring the time between the key being pressed and the key is released. This is more of a simulation of pressure than Iwasaki’s et al. (2009) approach that involved an accelerometer to detect typing pressure. However, the experiments in this thesis are sketches and prototypes and are not of a technological focus, rather an exploration of the possibilities of expressive typing. The benefit of using simulated pressure is that implementation is simpler for researchers who want to continue investigating pressure typing or expressive typing.

An additional factor to consider when typing or handwriting is the speed at which we are performing the action. Contradictory to handwriting, the speed at which you are typewriting is barely visible while typing, and the sense of speed at which you wrote the text is non-existing in a digital environment. The two additional inputs, speed and pressure, adds to the data we can collect from the user and extends the expressive possibilities we can reach.

Limitations of digital text

Digital text cannot alter each line of a letter as handwriting can. Handwriting’s ability to alter letters line by line leads to natural variation as mentioned by Huber and Headrick (1995). This variation of letters that is present in handwriting leads to the behavioral expressive qualities of the person who is writing, in a sense the personal expression of the user. In a digital environment, text manipulation is much more limited and includes the ability to change a parameter such as size, scale, boldness, and tilting but digital text cannot alter letters line by line. However, as mentioned in section 2.2, dynamically changing fonts such as kinetic texts and dynamic fonts is a way of manipulating digital text. Variable fonts, a dynamically changing font, have proven to be useful in the context of expression (Buschek et al, 2005, Bodine & Pignol, 2003 and Wang et al, 2004), as it can manipulate the appearance of each letter. A variable font is not as unlimited in its ability to vary the appearance of letters when compared to handwriting but can change parameters of a letter’s appearance, such as width, weight, and size dynamically. Variable fonts add expressiveness by the fact that they can alter each letter based on inputs from the users, such as speed or pressure. Manipulating width, weight, and size properties of letters dynamically, in combination with a users’ input, should provide the tools necessary to add variation to each letter by letter.

4.2 The sketches

There were a few challenges in designing expressive typewriting. For instance, extracting users’ behavior and articulations from the keyboard and presenting these complex human behaviors and emotions to the user to observe through text. After dealing with the challenges as best as I could, I needed to further investigate the expressive qualities that a digital

environment can provide. I tested multiple variable fonts and animations to determine in what ways these outputs can be expressive of implicit and explicit expressions. A list of potential experiments was compiled. The list contained experiments that were combinations of inputs and outputs. This listing and brainstorming activity resulted in a narrow expressive range of qualities. As I was thinking of the limited expressive qualities of variable fonts and animations output, I noticed how the feedback from hitting keys on computers possess a rhythmic quality. I decided to investigate the potential expressive qualities of sound feedback, as a way to compile a wider range of expressing behavior and intentional expressions. After evaluating the expressive qualities of variable fonts, animations, and sound feedback, the most fundamental and unique were chosen and programmed into tangible sketches.

The next part of this chapter presents the sketches. First, two experiments were conducted to experiment with the explicit expressions of typing through the use of a variable font. The next three experiments focused on the implicit qualities but through the use of a variable font, animation, and sound feedback.

Each experiment will present a readers and a writer's perspective. This separation is done to illustrate the expressive and communicative qualities of the text from the perspective of a reader and a writer. The reader perspective is the person who is observing or receiving the written text and the writer is the person who wrote the text.

Explicit expressions

Speed expression

Introduction

Speed expression is categorized as an intentional expressive experiment. Meaning the expressive qualities lie in the conscious process of the writing. In this speed experiment writing a letter slow results in bolder and bigger text and writing faster results in thinner text. The purpose of the experiment is to see what intentional expressive qualities variable fonts parameters have in combination with speed input.

Link to the sketch: https://expression-speed.glitch.me/

Writer perspective

Typing speed was experienced as offering enough control to manipulate the text consciously. Using a variable font to change boldness dynamically based on speed made it possible to see changes in speed but the letters themselves does not express a sense of speed in which it was written. (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Using boldness as the single changing factor made it possible to emphasize words by slowing down the writing pace. This is visible in figure (10). As a writer and being able to express myself through the means of emphasized words through bolder letters is not particular expressive.

Figure 10

Reader perspective

As an observer or receiver of a text visible in figure (9). The text does not tell the reader anything of why letters are bolder or what the person was trying to express when writing the text. Figure (10) expresses an emphasis on the words “care” and “nice”, which results in a more emotional

reception of the words. This emphasis does convey intentional expression but is limited in terms of expressiveness.

Pressure expression

Pressure expression was also categorized as an explicit expression experiment. The outcome of the experiment was similar to the speed expression experiment. As this experiment suffered from the same issues as speed expression. I will not go into detail about the lack of meaningful or clear expression again but present the main difference between speed and pressure writing. As it helps us understand how pressure input can be used when moving to the next set of experiments in section 4.3.

From the perspective of the writer, pressure offers better control when initiating change in letters' appearance than speed. It was easier to control the boldness of letters. To make the keyboard react upon key pressure in a way so that the letters clearly show a change in the output. One has to press a key for a longer time resulting in a more concentrated way of writing. Meaning pressure writing requiring more attention and skill to write with.

Implicit expressions

Speed tracking

Introduction

This experiment is categorized as an implicit expressive experiment. This means the expressive qualities lie in the unconscious process of the writing. As I am writing the letters, I am not trying to express something specific, but the patterns and habits of my writing speed are made visible as I read

the text. The letters change based on the speed between letters. Meaning writing a letter slow results in bolder text and writing faster results in thinner text. The purpose of the experiment is to understand what expressive behavior, patterns, and habits there are using speed through the use of a variable font.

Link to the sketch: https://tracking-speed.glitch.me/

Writer perspective

Speed input can be controlled to an extent and becomes easier to control as you practice. However, it is still hard to keep a really fast speed consistently. Writing on a keyboard seems to happen at high speed and when I slow down it does not feel very natural and becomes an intentional action. As Headrick and Huber (1995) suggest lower speeds of handwriting results in a more concentrated act of writing. It seems slower typing speed is due how long and how hard words can be to spell as well as the difficulty in reaching letters on the keyboard layout. As a writer of the text, I recognize the bolder letters as an indication of hesitation or thinking (Figure 11).

Figure 11

Reader perspective

As a reader observing the writing, the bold letters do not express hesitation or concentration of writing. As I reader I can observe the variation of bold and thin letters (Figure 11). However, the text is lacking expressions of what kind of behavior the writer wrote with.

Sound panning

As I was exploring different sound feedback, sound panning caught my attention by how it could be used as an expressive tool of writing behavior. Sound panning was about panning the sound from one auditable side to the other, in this case, left to right ear depending on the speed of writing. The outcome of the experiment resulted in a very similar experience as fade-in. Sound panning experiment did not lead to further iteration in the next section of experiments (section 4.3) and is therefore not interesting to go into detail about but instead hear what we learned from the experiment. I will illustrate what we learned by going into detail about the fade-in experiment since it directly illustrates and influenced the next set of experiments.

Fade-in experiment

Introduction

Fade-in is an experiment that is based and built upon previous speed tracking experiment. In the previous experiment, we saw how bolder letters do not convey a clear indication of the behavior of the writer. Fade-in experiment aims to add a better expression of the behavior of a person through how the letters appear on the screen. As mentioned earlier, animations are one of the expressive outputs that we can work within a digital environment that can change how letters appear on the screen. As animations change how the letter appears on the screen, typing using animations become an experience that is experienced by the writer of the text. And not something the reader of the text will experience.

Considering fade-in is an experiment using animations, this changes the experiment from the other experiments by how it focuses on the writer's perspective of the typing experience. And how the expression happens as you are actively writing the text. In the experiment, letters fade in with a short animation based on the speed of writing.

Writer perspective

Using a longer fade in delay had the most interesting experience. A long fade-in delay animation resulted in difficulties when writing fast. The letters appeared with a long delay after you had written them resulting in a disruption between what you were writing, and which letters were visible on the screen. However, the delay had a relaxing sensation and made for a much softer and gentle experience when writing slow. I found myself writing slower because of the soft and gentle experience.

The experiment showcased how a long fade-in animation delay can change the typing experience into a calmer and relaxing feeling while typing. This experiment resulted in an impressionable experience rather than an expressive one. Instead of me explicitly expressing something or the letters expressing my behavior. The way letters were acting changed the experience of typing into impressing a feeling onto me rather than me expressing myself.

Experience the sketch here: https://fade-in-speed.glitch.me/

4.3 The next step

In this section, the six new experiments that focuses on expressional and impressionable typing will be presented. These experiments involved user participation.

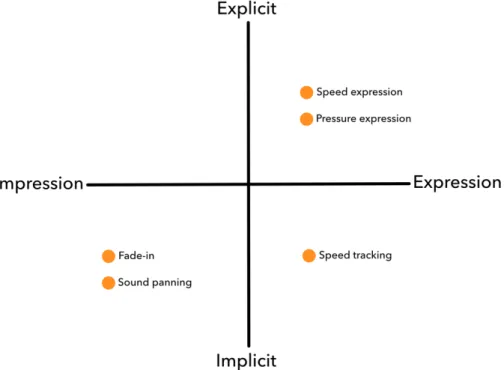

After evaluating the previous experiments, I noticed two main approaches for future experiments. The first approach was the result of evaluating

speed expression, pressure expression, and speed tracking (Figure 12). I noticed how using a variable font is quite difficult to make meaningful and clear expressions with, as the expressive output. As we previously saw in Speed expression, the experiment did showcase a degree of explicit expression, but the extent of that expression is very limited. There’s a poorness to the variable font as a material in relation to accomplishing explicit and implicit expression. I also noticed how the expressiveness of the majority of experiments was unclear from the perspective of the writer and reader.

In order to address these issues in the next set of experiments, I specified the expressive qualities of each experiment. Which will hopefully lead to clearer and more meaningful expressions of the writer and for the reader.

Figure 12. Diagram of the different qualities found.

The second approach was to investigate the experience of impression fade-in and sound pannfade-ing generated durfade-ing exploration (Figure 12). On the one hand, we have expression, that’s how the text looks and what you can express outwards, and on the other hand, the impression the typing has on you. The way the letters are acting is impressing something on you. An expression can take multiple forms of expression and not solely be directed outwards but inwards. Exploring this area with typing can lead to a better understanding of what shapes and forms digital writing can take. Areas that might not be possible to achieve in handwriting but possible on digital artifacts.

4.3.1 Expressional experiments

Previous experiments showcased how there was a lack of clear and meaningful expressions for both the writer and reader of the text. As a writer, I cannot express myself through the bolding of letters in a meaningful and attractive way. As a reader, I cannot make sense of bolding of letters as to the same degree as what the writer wanted to express to me. This section is about experimenting with more specific types of expressive qualities in typing and hopefully lead to clearer and more meaningful expressions of the writer and for the reader.

Expressive style experiments

I started investigating how to enable a larger expressivity when typewriting, by collecting and analyzing my own and other people’s handwriting. The letters and overall appearance could either be perceived as beautiful, normal, or distinct writing. A sense of quickness or haste as well as care or effort was also detected. Based on these findings the categories of beauty, a sense of haste, and finally care seemed most distinctive based on the gathered observations and would extend the expressive possibilities of digital typing (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Handwriting expressions: First beauty, haste and lastly care.

The next section will include a further explanation on how I designed beauty, haste, and care experiments. Considering all experiments are based on perception, it is important to clarify how and why I designed them in these specific ways. In order to experiment with more meaningful and clearer forms of expressive qualities. I needed to decide, in all three experiments, what the output would look like and how you would have to write to produce the letters' visual appearance.

Beauty

So far, we have managed to detect and experience a change in writing behavior and expression. This experiment aims to enable a wider range of expressive writing styles. Beauty is an experiment meant to explore how we can distinguish between different typing styles and appearances on digital artifacts. It is not meant to determine what is defined as beautiful but rather explore the possibility of expressing a range of writing styles and

appearances. Introducing two extremes of writing, “beautiful” and “bad”, enables us to express a range of writing styles. Beauty is subjective, however, determining a writing appearance that is more preferred than the other is the aim of this experiment. In this next section, I am in a sense determining the skillful capabilities required to write in order to get a good writing style on computers.

The input was based on handwriting observations, which will shortly be explained further, as well as the findings from the first series of experiments. Because of the limitations of determining each users’ writing patterns, I used my own patterns and experience as a base for determining how you would have to write to produce the range of writing styles.

Determining what the output would look like, in the case of the two extremes “beauty” and “bad” writing, I research what is associated with better and worse handwriting appearances. I started analyzing my own and other people’s handwriting that I had access to. It seemed for handwriting to be associated with a beautiful handwriting style, the text had to be consistent and symmetric throughout multiple elements that shape the writing, while a “bad” writing appearance was associated with inconsistent and asymmetric letters on the same elements. Those elements included: dimensions, spacing, slant or slope, and arrangement. I decided that a medium and consistent writing speed would result in the “beautiful” output extreme, where letters are consistent and symmetric. I chose to go with medium consistency in writing speed based on how the visual appearance of the text would look and the observations from previous experiments. Previous speed tracking and expression experiments showcased how letters were both varied (inconsistent) and not varied (consistent) at times. I decided that you would have to write at a consistent speed to mirror the consistent and symmetrical visual appearance.

Analyzing digital typography, consistency, and symmetry in how letters look are inherent (Figure 14), meaning digital text is in most cases arranged symmetrically. There are few commonly used typefaces that are less symmetric and less legible. Instead, typefaces express a variety of different emotional states and associations (Amare & Manning, 2012).

Figure 14.

I decided for the users to understand the two ranges of extremes, the letters would change dimensions, spacing, and scaling depending on the

consistency or inconsistency of their writing. If the user does not write completely consistent throughout a sentence or word, the aim was for the text to still be considered good. This can be seen in figure 15.

Figure 15

Writing with an inconsistent speed from letter to letter will result in an output reflective of that behavior. Letters will be bigger and smaller, closer, or further apart as well as scaled wrongly, resulting in the text appearing inconsistent and asymmetric (Figure 16).

Figure 16

Writing with a consistent medium speed meant that you could not write consistently fast or slow and have a result that would be symmetric. This is why an ai or a system with a better algorithm would be needed to fully capture the behavior of each persons’ typing to fully be expressive of each persons’ typing style and range.

Press the link to experience the prototype: https://expressive-styles-1.glitch.me/

Haste

The experiment is about giving the writer and reader a sense of quickness with which the text has been written. The input measures the users typing speed and will visualize that input. The question in focus became how to visually express a sense of speed in users typing. Previous speed experiments were evidential of speed changes, visualized through bolder letters when writing slower. Bolder letters in particular do not indicate a sense of speed rather a change in speed of some sort. Exploring options that could express a sense of speed I noticed how text manipulation such as, tilted, faded, boldness/thinness, or letter-spacing or combinations of them did not indicate a sense of speed in which the text had been written. I realized that a sense of speed is not solely based on how the text statically looks but how adding animation can be used to achieve motion. Adding animations to the text made it possible to indicate whether the text was written fast or slowly.

Link to the prototype: https://expressive-styles-3.glitch.me/

Care

After identifying care as an expression when handwriting I started comparing” beautiful” and normal handwriting to handwritten texts that were written with care. The texts shared many similar traits in the overall appearance of the letters. However, the significant difference was how the execution changed. A text that was written with care was written

significantly slower, more precise, and what seemed to use a consistent pressure amount. Overall the execution seemed more skillful and slower. Comparably to the output of the beauty experiment. A sense of care needed a contrasting appearance when you are not writing with care. That contrasted output had to express a sense of disorder. I achieved this similarly to how “bad” writing was achieved in the beauty experiment (Figure 17).

Figure 17

To determine what was considered typing with care, I utilized pressure as the input parameter for changing the visual appearance. Pressure is easier to initiate but requires more attention and skill to continuously write with the same amount of pressure. Meaning I could use a specific pressure amount as an indication of care since it required a lot of attention and practice to achieve it. Achieving the specific pressure input would result in well-written letters and text (Figure 18).

Figure 18

Link to the prototype: https://expressive-style-4.glitch.me/

4.3.2 Impressionable experiments

This set of experiments was about challenging the influence of handwriting in the project and creating a typing experience that utilizes digital tools to transform the keyboard into a medium evidential of expression potentially different from the capabilities of handwriting. The difference being the computer translates the user’s actions and outputs an impressionable experience. These experiments are about how the output is affecting or immersing you to feel a particular sensation when typing.

All these experiments are about creating subjective impressions. These impressions could potentially help interaction designers understand how certain qualities of interaction could result in certain emotional impressions within interactive systems, which could help them think more clearly around the user experience of expression-oriented systems.

Typing immersion

All experiments were based on distinct animations. To clarify what they are about and what they look like the following section has been devoted for this purpose.

Fade-in

The first experiment within this category is using the same animation as ‘fade-in’ experiment previously. The purpose of this experiment was to try and see if the impression of calmness and relaxation when typing was experienced by other users as well (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Picture of Fade-in experiment.

Link to a video of the prototype: https://vimeo.com/428300982

Bouncing

The second experiment is using a bouncing animation and tries to give an impression of playfulness or enjoyment while typing (Figure 20).

Figure 20. Picture of Bounce experiment.

Link to a video of the prototype: https://vimeo.com/428301739

Falling letters

The third and last experiments is experimenting with immersing the users into a sense of unease and being uncomfortable (Figure 21).

Figure 21. Picture of Falling letter experiment

Link to a video of the prototype: https://vimeo.com/428302549

4.4 Interpretation interviews

Ethical considerations

The research in this thesis follows the ethical guidelines from Vetenskapsrådet (2017). As my project developed into a second-person perspective, it was important that all participants were treated with transparency, respect, and anonymity as were informed about their rights and potential risks in participating in the experiments. One experiment in the category of impressionable experiences is concerning an uncomfortable experience. However, the intensity of the experiment has been adjusted to be low.

An important consideration is the subject of confidentiality and personal data. Therefore, my research precedes the ethical data handling rules and General Data Protection Regulation. All participants and personal data were anonymized. And all identifiable information will be removed. Furthermore, all participants were asked to sign a consent form that clarified the details of the experiments, potential risks, their rights, and how I will treat their personal data (Appendix 1).

The participants

I was interested in exploring how people would interpret and experience the expressive and impressionable qualities of the experiments. In order to generate a second-person perspective, I invited four participants to digital sessions. The participant consisted of two men and two women between the age of 20-30.

The interviews

The structure of the interviews was semi-structured. The interviews were conducted individually with each participant but since I wanted participants to learn from other people’s perspectives to further explain their experiences. I repeated and quoted other participants' answers in the session. Participants were asked to start typing and had the opportunity to write a predetermined sentence to start with. After getting used to the

experience they were asked a few questions: What their initial reactions were? How or where the experiment could be used in their opinion? Pros and cons about their experience as well as how the prototype could be developed further. The participants were not asked about how or where the experiments could be used as a way to direct future developments but for participants to more deeply talk about the qualities and experiences they encountered. Initial reactions can change the experience quite heavily after discussing more possibilities and contexts of set experience.

The category of expressive styles was conducted the same way as impressionable experiments with one alteration. At the beginning of participants experiencing the experiments, I analyzed their behavior and patterns and changed the code to better fit the participant. After getting used to the experience they were asked the same questions as described above.

Expressive style experiments

Beauty

This experiment is aimed to enable a wider range of expressive typing styles. By introducing two extremes of writing styles.

How does the prototype work?

The output is reflective of the input you produce. Meaning writing in a consistently will result in letters appearing consistent and symmetric.

Reaction

The majority of the participants commented on how it took some time getting used too but thought the experience was interesting. One participant stated, “Interesting to see how my own writing works. There’s

instant feedback on how weird or beautiful I’m writing. I’m not writing as consistent as I thought. “. Another one said, “It feels like there is a connection between how I emphasize it and what I’m writing.”. Two

participants also expressed how the experience wanted them to write consistently and make the text look “beautiful”. One of them said, “I have to be very careful about how I write. Nice when I get it right and very annoying if I sometimes get it wrong.”.

Discussing the use case scenario with one participant in the context of reflecting oneself in digital artifacts and developing a personal writing style. The participant said he believed it would definitely work but could use some more advanced algorithms or AI to help the process of variation in the output. Imagining future developments, he said, “you would have your

own personal signature style”. Two other participants talked about direct

messaging. One of them said, “emojis are completely useless from a practical point of view but they are very useful when conveying emotions. This is similar, the social value is the value. I think people would really like

it because the reason for people using emoji so much is because they can’t express feelings”.

Two participants referred to the experience as annoying in the beginning of testing. One participant stated, “Getting annoyed when I see the variation.

I try and can’t get what I want”. Participants did get better at controlling

the text after some time. Variation was still part of their output, but they felt more in control as the sessions progressed.

Another participant commented on the possibility of illegible outputs, “The

writing can become illegible. It is not clearer when writing like this. In this case I can definitely see what I’m writing.”.

Haste

The idea was to experiment with a sense of speed and pauses in people’s writing. Enable users to feel and see their writing speed as well as inform the receiving end about the users writing situation.

How does the prototype work?

Writing faster results in a very quick and snappy animation and writing with a slow speed result in letters appearing very slowly, almost slow-motion.

Reactions

All participants immediately commented on the interaction with the experiment, stating that it was a clear indication of writing fast or slow. One of the participants described the experience as, “It reflects how fast I write,

how fast the letters appear. Nice to see they arrive slowly but stressful when they show up quickly. Feels like I have to write fast.”. Another said, “It responds to my actions but there is a delay, in this case it is helpful because I can see the letters being written out quickly”.

A topic that reoccurred in each session was whether or not the animations would happen in real time or not when presented to another person. We discussed the differences that would make to the overall use and how it could be useful in real-time as well as non-real time. Participant commenting on a real-time scenario said, “It is quite natural and responds

to how I’m writing. If I’m thinking or hesitating it shows. There’s a clear indication. This way it is possible to see when a person writes all the time compared to someone who stops and thinks about what they are writing. It’s possible to tell who you are writing with. Differences between how you write is clearer in this one than previous (beauty)”. Participant pointing to

how the text looks, “This can be two different people or to different

mindsets. Maybe you start thinking more or become nervous then it shows”. The participant is referring to how the text would write itself out

slower, indicating nervousness or hesitation of some sort.

A participant described how this experiment could be used in non-real time scenario. The participant stated, “It could be useful if you pressed a button

and activated it (the animations) and see the letters be written out like this then it could be used when writing essays”. Another participant gave a

similar respond and said it could be valuable when writing by yourself, indicating how you wrote the text. For example, if there were no indications of writing slow, meaning the text was written fast, that could be a good thing when wanting feedback about particular parts of writing.

One of the testers reflected on the experience as a way for her to calm herself or someone else down. The participant further commented on how she would use it when writing a report, stating, “It might be good to see that I

write quickly. Might be satisfying and calming that letters are written out quickly”.

Care

The experiment is about expressing a sense of care when typing. That the writer had dedicated time and effort into writing the text.

How does the prototype work?

The prototype responds to pressure and to achieve an output reflective of care being put into the text. Users needed to find a specific pressure amount and consistently write the text using the specific pressure amount.

Reaction:

The majority of participants experienced the experiment as difficult. After spending some time with the experiment and given a hint that the experiment is influenced by handwriting, participants adjusted and reflected over the experience. One participant said, “In the other

experiments you could write however you wanted, and it responded well. In this one if you write carelessly it shows it, but it also becomes a bit punishing”.

One participant reflected over how this experience could evolve over time and said “If you know what it is and you can see it in real time, it feels like

you get more feedback out of it (than beauty). You know they are writing slowly and taking their time to really make it perfect. After a while we might recognize this letter animation and style to mean that someone wrote this with care”. A participant also talked about how the experiment

used different feedback to indicate the preferred output. The participant looked at the text and said, “You can see this one is types with little

pressure, this one with the preferred pressure and this one with a lot of pressure”. Meaning the expectation of how to achieve the preferred output

was not fully met by all participants but the way the experience evolved over time helped participants learn how to achieve the preferred output.

Most of the users thought it had similar uses as Haste but at the same time preferred Haste. Assuming the receiving end would know about how this experiment worked, one participant said,

“I would use it when applying for a job or when writing to grandma. It shows that I have been careful and wrote it slowly. When you can show this directly in the message. It shows how you worked your way to a result, carefully and proper. It shows how you are as a person”.

4.5 The expressive qualities of typing

Beauty

The experiment was experienced as having personal expressive qualities. From the perspective of the writer, the participant reacted upon how the text responded to their writing patterns, while as a reader of the text it is harder to tell a difference and recognize different people’s writing. All participants experienced their writing as inconsistent as they could see how their fluctuations in speed resulted in variation in letters. Some participants thought of the variation as their personal writing patterns and style, while others referred to the variation in the text as annoying because of how asymmetrical and inconsistent the letters were. These participants perceived the asymmetrical and inconsistent letters as bad writing; therefore, participants interpreted their text as them writing badly. This was frustrating since participants wanted their appearance and writing style to look good as it was a mirror of self-expression.

Link to a video showcasing the prototype: https://vimeo.com/428286766

Haste

Haste helped participants perceive how fast they were writing and made it possible to communicate when someone is thinking more about what they write, as well as hesitation and nervousness to another person. As mentioned earlier in section (2.1) Huber & Headrick (1995) reported on how handwriting possessed matching expressive qualities. The authors explained how handwriting could indicate when someone is concentrating on the act of writing and when someone is under emotional stress, such as nervousness. Similarly, the Haste experiment could inform the reader of the text about what conditions, situations, or circumstances the writer was in. It could also communicate back to the writer of the text in the same ways, in a sense expressing feedback to the user about their own patterns.

Link to a video showcasing the prototype: https://vimeo.com/428299160

Care

This experiment had some difficulties with both the writer and the reader's side. As a writer, participants said that it was hard to achieve the “correct” output and took some practice. For the writer, it was possible to tell a difference between the two outputs and associates one of them with care being put into the writing. However, as a reader, it was difficult to know that anyone output meant that the text was executed with care. Participants said that when they knew what the specific animation meant it did express