CAN ALL STUDENTS PLEASE

SPEAK UP?

A mixed methods study into the situational and motivational aspects of

(un)willingness to communicate in English in Swedish upper secondary schools AMANDA KARLSSON

School of Education, Culture and Communication Degree project ENA314

15 hp.

Supervisor: Elisabeth Wulff-Sahlén Examiner: Olcay Sert

School of Education, Degree project

Culture and Communication ENA314 15 hp

Autumn 2020

ABSTRACT

This study seeks to examine (1) in what situations Swedish upper secondary school students from two EFL classes are unwilling to speak English in English class, and (2) what the motivational factors are for the same students to speak English. Students in their first and second year of studying English in Swedish upper secondary school participated in this study. The data were collected using observations, a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The data collected in this study were analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. The results of the study showed that students are unwilling to speak English in assessed situations as well as in situations where students are given less time before they can speak. The results suggest that students are influenced by one another, and that using English only instruction will make students more confident in speaking activities since speaking English will be normative behavior in class. Moreover, students are motivated to speak the target language in class by the English they meet outside of school, and by the plans that they have envisioned for their future.

_________________________________________________

Keywords: willingness to communicate, motivation, upper secondary school, English

1 Introduction... 1

1.1 Aim ... 2

2 Background ... 2

2.1 The Swedish curriculum... 2

2.2 Willingness to communicate (WTC) ...3 2.3 Motivation... 5 2.4 Speaking anxiety ... 6 3 Method... 7 3.1 Data collection ... 7 3.1.1 Observations ... 8 3.1.2 Questionnaire ... 9 3.1.3 Interviews ... 9 3.1.4 Limitations ... 10 3.2 Data analysis ... 10 3.3 Ethical considerations ... 11 4 Results ... 12

4.1 In-class situations that result in less communication in English ... 12

4.1.1 Time for preparation ... 13

4.1.2 Assessment ... 14 4.1.3 Peer influence ... 15 4.1.4 General comments on WTC ... 16 4.2 Motivational factors ... 17 4.2.1 Extramural English ... 18 4.2.2 Future prospects ... 19 5 Discussion ... 20 6 Conclusion ... 22 References ... 24

Appendix A: Observation scheme ... 26

Appendix B: Questionnaire ...27

1 Introduction

During my time studying to become a teacher I have come across many English as a foreign language (EFL) learners in Swedish upper secondary schools who refuse to speak English in English class. I too faced this issue during my internship having an English class. None of the students answered or asked questions in English during class and when I spoke English to the students they responded in Swedish. Only during oral assignments that gave grounds for grading did the students speak English. I later discussed the problem with other teachers at the school and fellow student-teachers and came to the understanding that this was a common issue among students in upper secondary school.

Research shows that second language (L2) learners develop their communicative skills

through performance in classroom situations (Saint Legér & Storch, 2009). This implies that it is important to speak English in English class as much and as often as you can to be able to get the most out of the subject. Given that performing in classroom situations will develop the students’ communicative skills it is easy to understand that I felt confused as to why students were unwilling to speak English in English class.

There are no explicit demands written in the curriculum by the National Agency of Education (Skolverket) stating that students need to speak English in English class at all times. It is, however, written that the teaching should be conducted in English to a greater extent (Skolverket, 2011). Still, many teachers I have spoken to try to encourage students to speak English and aim to use English only instruction. At some times these attempts at using English only instruction are successful but at other times they are not, and the class continues to ask and respond to questions in Swedish instead of English. Previous research in the field suggest that students become less willing to engage in communication if they are demotivated (Sundqvist & Olin-Scheller, 2013), faced with teachers or learning conditions they do not agree with (Falout, Elwood & Hood, 2009), or if they suffer from speaking anxiety (Papi, 2010).

What motivates Swedish upper secondary school students to speak English is an important and pressing issue for teachers. Exploring the motivational factors for students to speak English, as well as in what situations students are less willing to speak English would be useful for me and others who will enter the profession of teaching. To date, several studies have investigated students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) (Yashima, MacIntyre &

Ikeda, 2018; Saint Legér & Storch, 2009; Cao & Philp, 2006). However, there are fewer studies that have focused on in what situations students are unwilling to communicate (see e.g. Fager, 2020). Thus, more research on students’ unwillingness to communicate is needed. It would also be interesting to explore the issue from the students’ perspective. By hearing the students’ point of view, it could be understood what different factors are at play in motivating students to speak English in English class.

1.1 Aim

Teaching an English class where the students are unwilling to speak English can be difficult. As previously mentioned, the teacher should substantially conduct the teaching in English according to the National Agency of Education (Skolverket, 2011). The students, however, are not obliged to use English to the same extent. This could be frustrating for the teacher and for students who want to speak English as much and as often as they can, but for some reason do not. Two Swedish upper secondary school classes were involved in this study and three different methods of collecting the data were used in order to gain a better understanding of the students’ perspectives. The two EFL classes were observed for one lesson each, a

questionnaire was given to the students and in addition, two semi-structured interviews were carried out with two groups of students. This study, therefore, focuses on the students’ perceptions of speaking English in English class.

Based on this aim, the following research questions are posed:

1. In what situations are Swedish upper secondary school students from two EFL classes unwilling to speak English in English class?

2. What are the motivational factors for Swedish upper secondary school students from two EFL classes to speak English in English class?

2 Background

2.1 The Swedish curriculum

The Swedish curriculum states that:

Teaching of English should aim at helping students to develop knowledge of language and the surrounding world so that they have the ability, desire and confidence to use English in different

situations and for different purposes. Students should be given the opportunity, through the use of language in functional and meaningful contexts, to develop all-round communicative skills. (Skolverket, 2011).

This means that all teachers who teach English in the Swedish upper secondary school should give students the opportunity to develop their language skills; it is however rather unclear how often or how much the students should use English in class.

One example of the Swedish curriculum’s unclarity is the following statement: “Teaching should as far as possible be conducted in English” (Skolverket, 2011). The quote is

problematic in the sense that (1) “The teaching” is for the teacher in class; it cannot be found anywhere in the curriculum how much English the students should use; (2) what is meant by “as far as possible”? The phrase as far as possible may mean different things to different teachers, which could result in students being given unequal opportunities. A formulation which states that both teachers and students should communicate in English to a further extent would perhaps make it clearer.

Furthermore, the assessment criteria do not mention how much or how often the students should use English in class, simply that the students should be able to express themselves in both written and spoken English (Skolverket, 2011). It is therefore up to the students to decide whether they will speak English at all times in English class or not. Due to the fact that there are no demands written in the assessment criteria; some students may choose not to

communicate in English, thus, not making use of learning opportunities.

2.2 Willingness to communicate (WTC)

How students’ unwillingness to communicate affect the language classroom is explained by Yashima, MacIntyre and Ikeda (2018) as follows:

In language classrooms all over the world teachers struggle to get learners to talk in the target language. Learners who avoid communication are a concern for teachers, curriculum designers, and language planners. This issue has been central to research on willingness to communicate (WTC) in a second language (L2) […] (Yashima, MacIntyre & Ikeda, 2018, p. 116)

Students’ WTC in an L2 has been addressed in many studies, and previous research in the field has focused on objective features in situations, such as who is speaking, at what time, in what kind of activity and where (Zhang, J. Beckmann & N. Beckmann, 2018). Objective features are also explained as situated WTC, meaning that students’ WTC can increase or

decrease depending on different situations or moments in class (Yashima et. al. (2018). Studies have also discussed subjective features which focus on L2 students’ own perceptions of situations. Subjective features are connected to students’ personality traits and interests (Zhang et. al. (2018). Zhang et. al. (2018) suggest that it is crucial to keep in mind that students all show individual differences in how they perceive different situations. Students’ WTC will therefore differ in language learning situations because of their individual interests and characteristics. This brings clarity into subjective and objective features; that they are both of importance for students’ WTC. The situations in which students find themselves, in contrast to their trait of character or personal interests will ultimately affect their WTC. For example, one student may show a higher level of WTC in situations where the teacher is listening because that student is concerned with achieving high grades, while in situations where the teacher is not listening, the same student will show a lower level of WTC. Similar to Zhang et. al. (2018), the results of Yashima et. al.’s (2018) study show that

students’ individual characteristics in connection to contextual factors will affect their WTC. WTC is in that respect not static but will change within different contexts. On a group level the results show that anxiety is one of the main reasons for not participating in

communication. The results also indicate that students are very much affected by their classmates’ way of communicating. This would mean that if one student were to use the L2 instead of the L1 more would likely follow that student’s example (Yashima et. al., 2018), thus, making peer influence another factor contributing to students’ WTC. Similar findings were presented in Cao and Philp’s (2006) study on WTC, suggesting that classmates can either motivate or demotivate one another. In that respect, a student less willing to

communicate could be paired up with a student more willing to communicate, thus increasing the less motivated student’s WTC. The making of stable groups and thinking of how to create group dynamic is important for students’ WTC. In contrast, the review of Zhang et. al (2018) shows that contextual factors such as classroom environment, or if the performance is

assessed or not is important for students’ WTC. However, students’ interest in a specific task, or if they find the task useful will too affect their WTC.

As previously mentioned, research in the field of WTC have studied subjective features such as students’ own perception of different situations, their ability to communicate, as well as their attitudes to in-class activities. Saint Legér and Storch (2009) have studied how these subjective features affect students’ WTC, stating that previous research on situational WTC have been rather small-scale projects and have not taken into account that subjective features

can change over time. Saint Legér and Storch thus conducted their study over an entire semester, allowing students to answer a self-assessing questionnaire multiple times during that semester. The questionnaires were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. In these questionnaires, students reported that the activity that was most demanding was whole class discussions. Students found whole class discussions more difficult due to the fear of being judged by their classmates and competitiveness (Saint Legér & Storch, 2009). Peer influence was addressed in Yashima et. al’s (2018) research, as well as Cao and Philp’s (2006) study on WTC, discussing the positive and negative outcomes of students being influenced by other students. Students competing with each other is one of the negative outcomes, causing a higher level of anxiety among students, thus affecting students’ WTC (Saint Legér & Storch, 2009). Positive outcomes of peer influence are stated to be, for example, more proficient learners motivating their less proficient peers to engage in communication (Yashima et. al., 2018).

2.3 Motivation

Similar to subjective features of students’ WTC, recent studies on second language motivation have focused on L2 learners’ self-perception, suggesting that there are three important key factors in terms of students’ motivation when learning an L2 (Dörnyei & Chan, 2013). The first key factor is the students’ inner motivation to be able to use the L2 in an effective way. Secondly, expectations from the students’ environment to learn the L2 and the students’ desire to use the L2 in a way that others expect them to. Finally, the experience of learning the L2 e.g. what the positive outcomes may be of being in the learning environment of the L2 (Dörnyei & Chan, 2013). These three factors constitute “the ideal L2 self” (Dörnyei & Chan, 2013, p. 439) and should make the L2 learning more successful. However, one study made in Iran found that the second key factor, the expectations from the student’s environment, actually made the students more anxious (Dörnyei & Chan, 2013). One possible explanation for the students’ anxiety could be that the desires from the students’ environment does not always correspond with the students’ own desires (Dörnyei & Chan, 2013). This could mean that, similarly to WTC, students’ motivation may be affected by their trait of character due to the fact that some students are motivated by the expectations from others while some are demotivated or anxious. Students’ anxiety when learning a second or foreign language will be further discussed in section 2.4.

Regarding demotivation, Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller (2013) claim that demotivation among Swedish EFL students is a real issue. The authors suggest that one reason for Swedish EFL students’ demotivation is the (so called) authenticity gap, meaning that the English that students face in school differs from the English they learn outside of school, i.e. extramural English (TV, video games, social media etc.). Students view the English they learn outside of school as more authentic and are, because of that, less motivated to learn English in classroom situations. According to Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller (2013), many Swedish EFL teachers fail to make use of the students’ interests in the English students meet outside of school, which is ultimately a disadvantage for the students. In contrast, Csanadi (2021) conducted a study which showed that extramural English have positive effects on both language proficiency and students’ WTC.

In addition to the authenticity gap, different factors are involved in students’ demotivation. Many EFL students state that their lack of motivation is due to their teachers (Falout, Elwood & Hood, 2009). Other studies suggest that the more dominant pedagogy that often exists in, for example, grammar teaching has had great impact on students’ motivation in a negative manner (Falout et. al., 2009). The study conducted by Falout et. al. (2009) concludes that students are demotivated by teachers and learning pedagogies the students do not agree with, thus, making it the teacher’s responsibility to create learning conditions and environments that are more agreeable to students. These more agreeable learning conditions would make

students more motivated in language learning. This would mean that the relationship between teachers and students are of importance for students’ motivation in class. Students who do not agree with their teacher will be less motivated, thus causing the classroom environment to be of lesser quality (Falout et. al., 2009). Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller (2013) conducted a study which showed that students’ demotivation can be decreased by further educating and training EFL teachers in methodologies concerning IT. By further educating EFL teachers, they will be better equipped to meet the needs of students (Sundqvist, Olin-Scheller, 2013).

2.4 Speaking anxiety

Anxiety was previously mentioned as a negative contributor to both motivation and WTC. Pérez Castillejo (2019) provides an explanation to why students suffer from speaking anxiety when learning a new language. What happens when students produce speech during class is that students need to first decide what they want to communicate, and then organize their thoughts into the language they want to communicate in. These two processes happen

simultaneously and take a lot more effort in an L2 than an L1. The reason behind it is that there are limited language resources for the students in their L2, while speech is more or less fluent in their L1 (Peréz Castillejo, 2019).

Papi (2010) suggests L2 anxiety as the factor that most often interferes with learning the L2. Papi further separates state anxiety from trait anxiety. State anxiety refers to students’ having a passing feeling of anxiety that is at times stronger and at other times weaker, while trait anxiety means having a more stable feeling of anxiety which appears in different situations. Students’ anxiety appears in most situations in the classroom; some student’s feel anxious in situations that are assessed, and some students feel anxious simply by communicating with others. Papi further claims that L2 anxiety affects both motivation and WTC in a negative manner. Similarly, Teimouri (2017) connects speaking anxiety to motivation and argues that different emotional states such as anxiety, joy or shame is closely connected to the “L2 motivational self system” (Dörnyei 2005, 2009, in Teimouri, 2017, p. 682), that has been previously discussed under section 2.3.1. Students with L2 anxiety would, in that respect, be less motivated and less willing to communicate in classroom situations. This would mean that WTC, motivation and anxiety are interrelated in students’ choice to participate in

communication in classroom situations. To gain a deeper understanding of these concepts, multiple methods will be used in this study to examine how they interrelate in the

participants’ choice to communicate in the EFL classroom.

3 Method

In order to investigate in which situations Swedish upper secondary school students are unwilling to speak English and what motivates the same students to speak English in English class, the data were collected using three different data collection tools. The data were

collected in a Swedish upper secondary school, using observations, a questionnaire, and semi-structured interviews, each of which will be described in further detail below. The data were then analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

3.1 Data collection

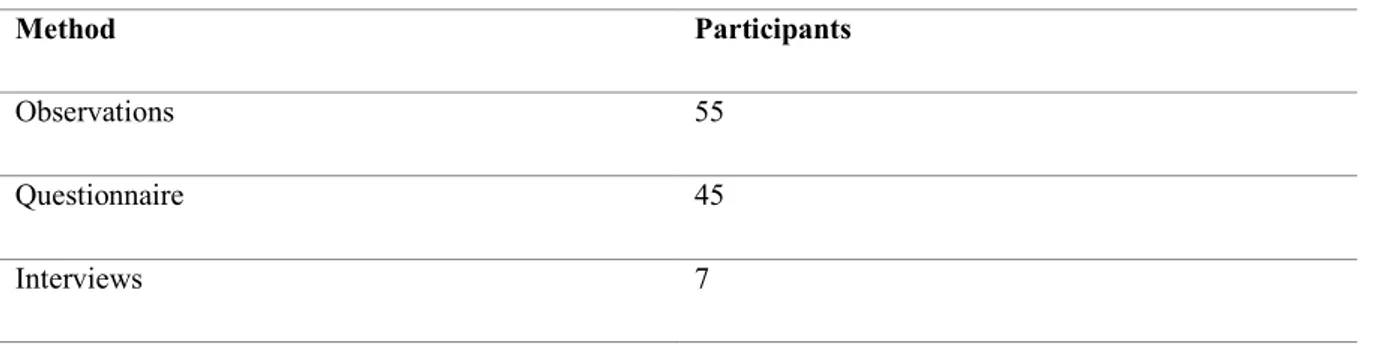

As previously mentioned, the data for this study were collected in multiple ways. The different methods and the participants of each method are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Methods and participants

Method Participants

Observations 55

Questionnaire 45

Interviews 7

As a first step of collecting data I observed two EFL classes in a Swedish upper secondary school. The first lesson I observed was an English 6 class, consisting of 27 students 16 to 17 years of age in their second year of upper secondary school and the second lesson I observed was an English 5 class consisting of 28 students, who were 15 to 16 years of age in their first year of upper secondary school. Both classes had the same English teacher and the topic for both lessons was communication i.e. the students speaking about their communication. As a second step of collecting data, a questionnaire was given to the students at the end of class. All 55 students were asked to participate and 45 of the students answered the questionnaire.

Lastly two semi-structured group interviews were carried out. At the beginning of each class I asked the students if anyone would like to participate in an interview. In the English 6 class three students volunteered and in the English 5 class, four students volunteered to participate in the interview.

3.1.1 Observations

In preparation for the observations I created an observation scheme that would allow me to take notes quickly. The observation scheme was created for me to gain a better understanding of in what situations the students were less willing to speak English as well as what their actions were in those situations. The observation scheme was inspired by the COLT scheme part A developed by Nina Spada (Rondon-Pari, 2012). However, my observation scheme was a highly simplified version of the COLT scheme. For my observation scheme, categories which contained possible classroom situations as well as possible actions in those situations were created. The categories were based on my previous knowledge from my internship as well as previous research. Since I did not know which situations may occur before the observations were carried out, the list of classroom situations was quite long. The categories

have therefore been reduced for this report (see Appendix A), only presenting the situations which actually occurred during my observations. In these situations, I observed how the students acted, i.e. what language they used, if the teacher encouraged the students to speak English, if the students influenced each other to speak English as well as the students’ behaviors, e.g. if the students seemed nervous, confident etc. I wanted to focus on those actions in order to gain insights that could be of use later on in the interviews. I also created one column for notes which allowed me to describe other interesting occurrences I took notice of which did not fit into any of the other categories.

3.1.2 Questionnaire

At the end of both lessons, the students were asked to participate in a questionnaire. In the English 6 class 24 out of 27 students participated and in the English 5 class 21 out of 28 students participated in the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 13 questions (see Appendix B). The questions were concerned with the students’ experiences speaking English in English class and were in the form of a Likert scale. The students were faced with different statements and were then allowed to express how well that statement fit with their own experience on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = Disagree, 5 = Agree completely). The statements were based on the aim of this study and were designed to provide an overview of the students’ attitudes and feelings about speaking English in the EFL classroom. To ensure that the

students were able to understand all questions, the questionnaire was carried out in Swedish to decrease the risk of misinterpretations.

3.1.3 Interviews

As previously mentioned, the students who took part in the observations and questionnaire were asked to participate in a semi-structured group interview. The invitation went out to all students of both classes. In the English 6 class three students accepted to participate and in the English 5 class four students agreed to participate. I discussed my findings from the

observations with the participants, asking them to explain the situations which occurred from their point of view. The interviews included questions, with room for follow-up questions, as well as a discussion about the lesson I observed. The interview questions translated into English can be found in Appendix C. However, those questions were prepared before the observations which means that a number of questions were improvised after the observations and are thus not visible in the appendix. The interviews addressed different situations where the participants are more or less comfortable to speak English in English class and what

motivates the participants to speak English. The first interview with the participants from the English 6 class lasted for 20 minutes and the second interview with the participants from the English 5 class lasted for 14 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded with the

participants consent. Since I did not know how comfortable the participants were with speaking English, the interviews were carried out in Swedish to make it easier for the participants to express themselves.

3.1.4 Limitations

During the time of this study, a global pandemic was taking place, which posed issues to this study. In regard to the restrictions following the pandemic, multiple visits to the school were difficult. It was therefore in my interest to carry out the observations, the questionnaire and the interviews the same day. This made time an issue in the way that the students did not have the time for longer interviews. If I had been able to visit the school on multiple occasions, there might have been time for longer interviews on days that better fit with the students’ schedules. Having longer interviews with the participants could have provided an even deeper discussion between me and the participants, thus, giving me more or other information of importance, which could have affected the outcome of this study.

3.2 Data analysis

The data was analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. The quantitative method was applied to the questionnaire. I organized the participants’ answers and presented them in the form of tables, using statistical analysis. A mean score was created for each of the questions from the questionnaire in order to present the results in one table. For example, one question asked if the participants were motivated by their classmates to speak English. The participants were then allowed to rate the statement from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree completely). The mean score for that question was 2.8, and 2.5 being the average score, 2.8 would indicate that the participants neither disagree nor agree completely with that statement.

The qualitative data (observations and interviews) were analyzed using content analysis, based on Bengtsson (2016). According to Bengtsson (2016) content analysis can be used as a method on all types of data, which made content analysis fit well with this study because of this study’s multiple ways of collecting the data. Content analysis aims to “link the results to their context or to the environment in which they were produced […]” (Bengtsson, 2016, p. 9). In order to use content analysis, the data are transformed into a written text and then

reduced into a smaller amount of text. The reduced amount of text is sorted into themes based on recurrences from the texts. These themes will then, hopefully, provide understanding of the results of the study (Bengtsson, 2016).

To analyze the data using content analysis, I needed to transform my observation scheme into running text, as well as transcribing the interviews. To transform the observation scheme into running text, I wrote down the situations in the order in which they appeared combined with how the participants of the study acted in those situations. For example: “In the group discussions, students of one group seemed nervous. All students of that group discussed in Swedish while looking at me and their teacher multiple times…”. In this way, a longer text was created with the support from the observation scheme. As part of the content analysis, four steps were taken in analyzing the data for this study (Bengtsson, 2016). The first step, decontextualization, meant that I read through the data multiple times in order to be able to identify smaller units of the text that carried meaning to this study. The second step, recontextualization, meant that I went back to the original text and compared it with the smaller text units I had identified to make sure that nothing important had been excluded. The third step, categorization, meant that I identified larger themes based on the smaller units which would help me answer my research questions. The search for themes was time

consuming and these steps were taken multiple times before themes emerged which I believed to be representative. The themes will be further presented in section 4. The final step,

compilation, is the presentation of the results of this study.

3.3 Ethical considerations

Ethical principles, provided as guidelines by the Swedish research council (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002) were followed in this study. In accordance with these guidelines, all participants of this study were assured that their identities would be concealed, as would the name of the school where the study was conducted. All involved in this study have accepted to participate and were informed that they were free to cancel their participation at any time or refuse to answer a question.

In order to further follow the confidentiality clause, all names have been omitted from this report, and students are referred to as Student A, Student B etc. All participants were informed of this study’s purpose and of the fact that all data, including audio-recordings would only be used for this study.

4 Results

In the following sections, themes that emerged in the data analysis will be presented. First, the quantitative results from the questionnaire is presented. Second, the qualitative results from the observations and interviews are presented. Each section is connected to one of the

research questions. Section 4.1 will address situations where students are less willing to speak English in English class and section 4.2 will address students’ motivation to speak English in English class. Both sections are organized according to the themes that emerged in the data analysis. Results from the questionnaire, the observations as well as the interviews will help support these themes. The results from the questionnaire will provide a general overview of situations, while the results from the observations and interviews will explore different

aspects of the general overview in further detail. The quotes presented in this report have been translated by me, and minor grammatical changes have been made to ensure an easier read.

4.1 In-class situations that result in less communication in English

Questions 1 to 7 in the questionnaire addressed in-class situations. The mean scores for those questions (see Table 2) show that there are two questions with a mean score below average (2.5) and five questions with a mean score above average. A low mean score indicates that the participants do not agree with the statement, whereas a high mean score indicates that the participants do agree with the statement.

Table 2. Questionnaire mean scores

Statement Mean score

I think it is difficult to respond to questions in English. 2.2 I think it is difficult to discuss with my classmates in English. 2.28 I think it is difficult to speak English during the English lesson. 2.6 When I speak during the English lessons I speak English. 2.8 If the teacher asks me a question in English I will respond in English. 3.35 I think it is difficult to give a presentation in English. 3.37

If one of my classmates speaks to me in English I will respond in English. 3.4

The question with the lowest mean score (2.2) asked if the participants find it difficult to respond to questions in English, thus, the participants do not agree with that statement. The participants neither agree with the statement which asked if they found it difficult to discuss with their classmates in English, nor the statement which asked if they found it difficult to speak English during the English lesson. The mean scores (2.28 and 2.6) indicate that the situations those statements addressed are situations where students may feel more confident speaking English in the English classroom. In contrast, one question asked if the participants found it difficult to give presentations in English, which the participants according to the mean score (3.37) agreed with. The results of the questionnaire indicate that students do not particularly struggle with engaging in communication in English class, unless giving

presentations. The question with the highest mean score (3.4) asked if the participants responded in English if a classmate spoke to them in English. In contrast, another question asked if the participants speak English during the English lesson, which according to the mean score (2.8) the participants do not always do. This indicates that the participants are more likely to respond in English if they are being spoken to in English, which is further justified by the mean score of the first statement presented in Table 2.

4.1.1 Time for preparation

One of the themes that emerged while analyzing the data from the observations and interviews was time for preparation, which proved to be of importance for students when engaging in communication. The participants stated that not being able to prepare what they want to communicate made them less willing to join a communicative activity. Student A expresses that answering questions in class gives you less time to prepare what you want to communicate:

One thing that is difficult, is questions that you are completely unprepared for, that you have not had the time to think about. Since it is a different language, you might need some more time to think compared to when you speak Swedish.

According to the same student, the fact that it takes more time to think of how to answer questions asked by the teacher is due to the lack of fluency:

Sometimes, not being able to translate one word to English could make students not want to answer the question at all, which is expressed as follows by Student C:

Even if I speak English at home, I still get nervous. Because sometimes you know how to say everything that you want to say in English except for one word, and then it feels as if you cannot say anything at all. You get stuck on one word and it destroys everything.

The issue of fluency was also brought to attention by the participants of the English 5 class. In student G’s words:

It is difficult when the two languages collide, and you do not know how to translate the English word to Swedish. It makes me hesitate.

The results from the interviews indicate that students find whole class activities such as whole class discussions as well as responding to questions difficult due to the lack of time they get to prepare their answers. Students need to decide what to communicate and map their thoughts into English before engaging in communication. The lack of fluency makes students more nervous, and thus less willing to communicate in those situations.

4.1.2 Assessment

Assessed situations have been described by the participants from the interviews as the most demanding situations in English class. During the observations many students seemed more relaxed in the group discussions without the teacher listening. The data from the interviews also showed that there is a fear among students of being judged by the teacher in assessed situations. Student A expressed the feeling of constantly being assessed in the English classroom, especially if the teacher were to demand that students spoke English at all times:

If a teacher comes in and says that we have to speak English all the time and will not allow us to speak Swedish, it becomes so demanding, and then you will feel like you have to perform all the time. You would be afraid of constantly being judged by the teacher in all situations.

The questionnaire mean scores indicated that giving presentations is the situation that students find most difficult (see Table 2). According to student B giving presentations in English is the most demanding activity in the English course:

It (presentations) just feels so unnatural. It is just awful, I do not even want to talk about it. Especially with everyone looking at you.

Another student adds that what you intend to say does not always correspond with what you are saying, which causes stress and anxiety. In student B’s words:

I mean, in my head I sound like a native English speaker. And then when I speak I sound so Swedish, and that is just so stressful.

In student A’s words, presentations in English are hard due to students relying on manuscripts in a different way than in Swedish:

It is hard to salvage the situation when you have rehearsed it. Because you are so dependent on the manuscript. So, if you lose a word, and cannot remember how to say it in English, you will just start to stutter.

In contrast, Student C explains how presentations are actually easier in English:

With English, there is only focus on language. It feels as if you are being assessed on fewer things compared to when you hold presentations in Swedish.

This indicates that assessed situations in English can be viewed as easier compared to assessed situations in Swedish, given that presentations in Swedish are more focused on content than language. This was further supported by Student E:

I mean, since we attend a Swedish school it is expected from us that we can speak Swedish. So, presentations in Swedish are more focused on content, like dealing with sources for example. This is harder for me since I am more confident in English than in Swedish.

However, presentations are not the only situations that are assessed in English class. Student A expresses that group discussions are hard as well if the teacher is listening:

I think it is stressful when the teacher is listening. Because then you put more pressure on yourself. Student B adds:

You have to focus more. Because when you discuss in groups the speech becomes more fluent, but when I know that a teacher will assess the discussion I feel like I have to say the right things. You have to perform in another way.

Overall, these results suggest that students are less willing to communicate in English in assessed situations, and that being overseen by the teacher in speaking activities can make students put more pressure on themselves.

4.1.3 Peer influence

The results from the observations indicate that peer influence is of special importance. In both classes I observed, students were influenced by one another in group discussions. In the groups where students spoke Swedish, the students spoke Swedish at all times. Similarly, in

the groups where students spoke English, all students spoke English at all times. In the English 6 class, 4 groups spoke Swedish during the group discussions, and 2 groups spoke English. In the English 5 class, all 7 groups spoke English during the group discussions. This indicates that students influence each other in group discussions to either communicate in Swedish or English, as well as the possibility of more proficient learners influencing their less proficient peers to speak English.

Peer influence was further discussed during the interviews. According to Student A, assessed situations would not feel as demanding if all students spoke English in English class:

If one student starts to speak English, the whole class will speak English. If everyone spoke English all the time I do not think it (assessed situations) would feel as difficult as it does now.

Student A’s statement was further supported by the participants from the English 5 class. In the English 5 class all students speak English regardless if the situation is assessed or not. In Student D’s words:

It is like a spell, the moment we come in to English class we switch from Swedish to English. Student E continues:

I think that is the reason why I do not feel nervous before English presentations. I feel confident speaking English.

The participant’s answers indicate that speaking English at all times during English class could cause for less tension during assessed situations, i.e. presentations. These results provide important insights into the influence of other classmates, indicating that students are more willing to speak English if others in the classroom do so as well. This also explains why the questionnaire mean scores indicate that the participants are more likely to answer in English if they are spoken to in English.

4.1.4 General comments on WTC

During the observations for this study several interesting things were noticed in regard to students’ unwillingness to communicate. First, the two classes I observed acted differently. The English 6 class I observed seemed more uncomfortable with speaking English than the English 5 class. This was especially visible in the whole class discussion when many of the students in the English 6 class hesitated to engage in communication. Second, in the English 6 class most students answered and asked questions in Swedish, in contrast to the English 5 class where most students answered and asked questions in English. This can be supported by

the findings presented in section 4.1.3, and that the students in the English 5 class are more willing to communicate in those situations due to all students always speaking English in class.

Comparing the results from the questionnaire with the results from the observations and interviews, some inconsistencies can be shown. One question asked if the participants responded to the teacher’s questions in English, which according to the mean scores they do. This is interesting due to my findings from the observations, where many of the students answered the teacher’s questions in Swedish instead of English. Not responding to questions in English was more common in the English 6 class I observed. This was further supported in the interview with students from that class, when student B described the difficulties with speaking in whole class activities:

In front of the whole class, since it is rather uncommon that anyone answers the teacher in English, it becomes such a big deal to speak English. That is the worst part, I guess.

This indicates that students would find it easier to speak English in whole class activities if everyone answered the teacher’s questions in English.

4.2 Motivational factors

In the questionnaire, there were 4 questions that were concerned with students’ motivational factors (see Table 3). All questions which concerned students’ motivation have a mean score above average, however, two statements seem to be more agreeable to the participants whereas two statements seem less agreeable. As previously mentioned in 4.1, a low mean score indicates that the participants do not agree with the statement, whereas a high mean score indicates that the participants do agree with the statement.

Table 3. Questionnaire mean scores

Statement Mean score

There is a lot in school that motivates me to speak English. 2.6 My classmates motivate me to speak English. 2.8 There is a lot outside of school (out of school activities, friends, interests)

that motivates me to speak English.

3.15 My teacher motivates me to speak English. 3.84

One question asked if there is a lot outside of school (out of school activities, friends,

interests), i.e. extramural English, that motivates the participants to speak English and another question asked if the participants are motivated by their teacher to speak English. Both of these statements are motivational factors for the participants, with mean scores above 3. In contrast, two questions which asked if the participants were motivated by their classmates or other factors in school seemed to agree less with the participants’ views. Interestingly enough, the participants seem less motivated by factors in school than factors out of school with the exception of the teacher. The teacher, who may be considered to be a main contributor to in-school activities, is the great motivator for the participants according to the mean scores.

4.2.1 Extramural English

The questionnaire mean scores indicate that the participants are most motivated to speak English by their teacher. Surprisingly, none of the participants mentioned the influence of their teacher in the interviews. Furthermore, the questionnaire mean scores indicate that students are more motivated by factors outside of school than factors in school. This was further supported in the interviews, where the participants discussed the importance of English in their out of school activities. As expressed by Student D:

As for me, when I socialize online through gaming for example, I speak English to all of my friends. Most of my online friends are from other countries, like Germany for example. So, it is important for me to be able to communicate in English.

Most participants reported that English is of vital importance in their lives outside of school, as they are filled with English influences. Student F said:

I do not even watch Swedish TV-series or movies. I only watch English ones. And all of my social media pages are in English, I mostly follow English speaking celebrities and so on.

A common view amongst participants was that extramural English can be of use in their own language development. In the words of Student C:

One thing that really motivates me is looking at English political debates, for example. You learn interesting new words and expressions, and you think of how you can use those expressions in your everyday speech.

Student A agrees and adds:

Yes, since I am interested in politics I want to be able to understand everything they say so that I will develop my academic English.

The participants’ answers suggest that one important motivating factor for wanting to engage in English communication is extramural English, as it is an important source of knowledge. It is also indicated by the results that out of school activities where English is included have positive effects on students’ English.

4.2.2 Future prospects

Another significant motivational factor that appeared in the interviews was how English can be of use in the participants’ futures. This could make students more motivated learning English than mastering other subjects, e.g. Swedish. As reported by Student E:

To me, English is more important than Swedish. I mean, I do not plan on living in Sweden in the future. Student E’s view was echoed by other participants as well, as expressed by student F:

For me it is about my future career. All educations I want to apply to and all lines of work I am interested in would require that I speak English.

One of the participants have relatives outside of Sweden, which motivates the participant to speak English. In student F’s words:

I have relatives who live in English speaking countries, so it is important for me to keep developing my English skills so that I can use English when I travel for example. I think that everyone needs to know how to speak English, because in that way it is easier to communicate with each other.

This indicates that students realize that English is a global language and that communicating in English is necessary when travelling out of Sweden, thus motivating them to increase their knowledge in English by speaking. Student F continues:

If you want to be able to communicate with as many people as possible, you need to speak English. The participant’s statement suggests that communicating with others in English is how the language can be mastered. This corresponds well with the results from the observation of the English 5 class. Since the students of the English 5 class spoke English during the entire lesson, it seems as if they realize the importance of performing in class to develop their communicational skills. However, in the English 6 class where not as many students spoke English in class, the idea of performing orally is still viewed as important. As expressed by Student A:

Together these results provide insights into which the motivational factors are for Swedish upper secondary school students to speak English in English class. Overall, these results show several important motivational factors: the English that students meet outside of school, their desire to engage in communication with other English speakers, as well as if English is a part of the students’ future prospects.

5 Discussion

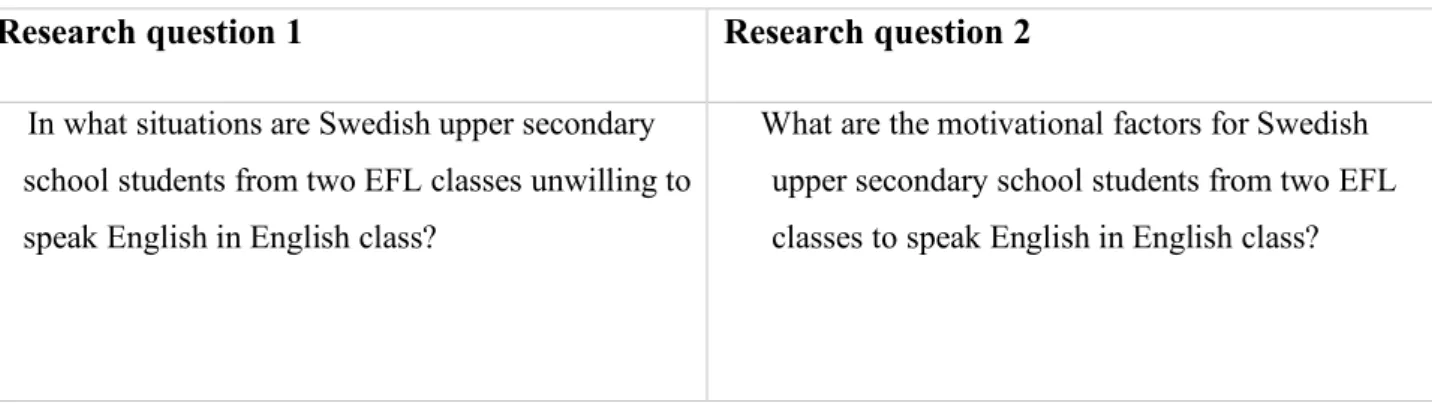

Table 4. Research questions

Research question 1 Research question 2

In what situations are Swedish upper secondary school students from two EFL classes unwilling to speak English in English class?

What are the motivational factors for Swedish upper secondary school students from two EFL classes to speak English in English class?

The results of the first research question (see Table 4) suggest that students get nervous and more self-conscious in assessed situations, which causes them to be less willing to speak English in those situations. Some inconsistencies were shown comparing the results from the questionnaire to the interviews and observations. According to the results from the

questionnaire, students did not find it difficult to respond to questions in English. However, the questionnaire can only provide some insights into the issue due to mean scores being the only statistical measure used in this study. Participants further stated that responding to questions gives you less time to prepare what you want to say, which causes stress. This was further validated in the observations, where many students responded to questions asked by the teacher in Swedish. Looking at the participants answers, the issue is connected to

student’s lack of fluency. As previously explained by Perez Castillejo (2019), learners need to first decide what they want to communicate, and then organize their thoughts into English. It was communicated by the participants of this study that it takes a lot of effort deciding how to communicate utterances in English, thus making them more hesitant to answer questions asked by the English teacher.

Participants reported in the questionnaire that the situation they find most difficult in English class is giving presentations. This, in contrast to responding to questions, was consistent with the results from the interviews. Participants reported that giving presentations make them nervous and more self-conscious. The results from the interviews indicate that other in-class activities (e.g. group discussions and whole class discussions) can be difficult as well, because those situations are perceived as assessed if the teacher is listening. The results suggest that the influence of the participants’ classmates was of special importance in speaking activities. The observations showed that students affected one another in group discussions, e.g. in the groups where students communicated in English all participants of that group communicated in English and vice versa. The importance of peer influence may not be that surprising, considering that previous research has addressed how peer influence can affect students’ WTC (Saint Legér & Storch, 2009; Yashima et. al, 2018; Cao and Philp, 2006). Peer influence was however only expressed by the participants as something positive. The

participants did not raise competitiveness as an issue, as suggested in the study by Saint Legér and Storch (2009). Similar to the findings presented in Yashima et. al.’s (2018) study, the participants of this study stated that assessed speaking activities may feel less stressful if all students spoke English at all times in English class. As expressed by another participant, the reason for feeling confident in assessed speaking activities is because of that participant’s experience of always speaking English in English class. Hence, encouraging English only instruction may make students more confident in assessed speaking activities.

The results of the second research question (see Table 4) indicate that some motivational factors for students to speak English in English class are extramural English, e.g. the English that students face outside of school, and if students’ plans for their future include speaking English. The mean scores from the questionnaire indicate that students are motivated by their teacher and by factors outside of school. This is interesting in contrast to Falout et. al.’s (2009) study, which stated that students’ demotivation was often caused by their teachers. The teacher being a motivating factor for the participants was not further discussed in the

interviews of this study, which means that it cannot be further supported.

It was, however, reported by the participants that they are motivated to speak English by their interests and out of school activities. Extramural English was previously brought to attention in this study by Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller (2013), saying that extramural English may cause students to be less motivated because of the authenticity gap between extramural English and EFL class English. Csanadi’s (2021) research however, which suggested that

extramural English have positive effects on student’s WTC, seems to agree more with this study due to the fact that participants expressed extramural English as an important

motivational factor. The fact that EFL students are motivated by their use of extramural English was supported by the participants of this study, due to extramural English being included in their out of school activities. These activities and interests include gaming, social media as well as political debates, which cause students to speak and be exposed to English. The results are in some respects consistent with Dörnyei and Chan’s (2013) idea of the “ideal L2 self”, that students are motivated by their desire to use the language in an effective way. However, the other two key factors suggested by Dörnyei and Chan, the expectations from the student’s environment and the experience of learning, were not brought to attention by the participants of this study. Judging by the participants’ answers, students are motivated to develop their communicative skills by how English may affect their future prospects. Participants claimed that their desire to be able to communicate with others if they were to move to a different country, as well as their future careers, are important motivational factors.

6 Conclusion

Both of the research questions posed in this study were answered through the use of observations, questionnaires and interviews. The first research question had its focus on situations where EFL learners are unwilling to speak English in English class. Themes

emerged in the data collection, namely time for preparation, peer influence and assessment i.e. assessed situations and situations where students get less time to think of what they want to communicate. The second research question aimed to explore the motivational factors for EFL learners to speak English in English class. Themes that emerged were extramural English and future prospects.

Based on the results of this study, Swedish EFL learners are less willing to speak English in situations where they are assessed or perceive a feeling of being assessed. Students are less likely to answer questions or engage in communication in English if they feel like they are not given enough time to think of what they want to say. Students are affected by their

classmates, meaning that students may be hesitant to speak English in English class if their classmates do not speak English. As a solution, it could be suggested that using English only instruction may have positive effects on students’ willingness to communicate. This is suggested since the participants of this study claimed to have an increased confidence in

English class due to their classmates speaking English at all times in English class.

Motivational factors for EFL learners to speak English in English class include their out of school activities, interests and future prospects. Students are motivated to achieve a higher level of fluency and an increased vocabulary to be able to communicate with others outside of school as well as understanding what others communicate. Participants of this study view English as a global language, meaning that their future plans (leaving Sweden, work opportunities) often include English.

The results of this study cannot be generalized, due to its small scale. The results are based on the observations, the questionnaire and the interviews of two Swedish EFL classes, and may look different with more participants. The statistical significance is also limited in this study, due to questionnaire mean scores being the only statistical measure. The results could

however provide some important insights into Swedish EFL learners’ perception on their English teaching, which could inspire other student-teachers and teachers. This also leaves the possibility for further research, as a study with more participants, further observations and interviews, may reveal more information about Swedish EFL learners’ motivation and

situations that affect the same learners’ willingness to speak English in English class. Another interesting aspect of this study, is the fact that the participants rated their teacher to be the great motivator in the questionnaire, in contrary to previous studies (Falout et. al., 2009). However, since the topic was not discussed in the interviews it cannot be further validated in this study but would definitely be interesting to address in further research.

References

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis.

NursingPlus open, 2, 8-14.

Cao, Y. & Philp, J. (2006). Interactional context and willingness to communicate: A

comparison of behavior in whole class, group and dyadic interaction. System, 34(4), 480-493. Csanadi, R. (2021). The impact of extramural English on students’ willingness to

communicate in an EFL context (Dissertation, Basic level). Mälardalen University.

de Saint Léger, D. & Storch, N. (2009). Learners’ perceptions and attitudes: Implications for willingness to communicate in an L2 classroom. System, 37(2), 269-285.

Dörnyei, Z. & Chan, L. (2013). Motivation and vision: An analysis of future L2 self images, sensory, styles, an imagery capacity across two target languages. Language learning, 63(3), 437-462.

Fager, L. (2020) A qualitative study on students’ perceptions of (un)willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language (Dissertation, Basic level). Retrieved from

http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mdh:diva-47021

Falout, J., Elwood, J. & Hood, M. (2009). Demotivation: Affective states and learning outcomes. System, 37(3), 403-417.

Papi, M. (2010). The L2 motivational self system, L2 anxiety, and motivated behavior: A structural equation modeling approach. System, 38(3), 467-479.

Peréz Castillejo, S. (2019). The role of foreign language anxiety on L2 utterance fluency during a final exam. Language testing, 36(3), 327-345.

Rondon-Pari, G. (2012). Analysis of L1 and L2 use in Spanish college courses using the COLT observation scheme. Journal of college teaching and learning, 9(3), 189-199. Skolverket. (2011). English. Stockholm. Retrieved from

https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a74181056/1535372297288/English-swedish-school.pdf

Sundqvist, P. & Olin-Scheller, C. (2013). Classroom vs. Extramural English: Teachers dealing with demotivation. Language and linguistics compass, 7(6), 329-338

Teimouri, Y. (2017). L2 selves, emotions, and motivated behaviors. Studies in second

language acquisition, 39(4), 681-709.

Vetenskapsrådet. (2002). Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig

forskning. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet. Revised: December 13, 2017.

Yashima, T., MacIntyre, P. & Ikeda, M. (2018). Situated willingness to communicate in an L2: Interplay of individual characteristics and context. Language teaching research: LTR,

22(1), 115-137.

Zhang J., Beckmann N. & Beckmann J. (2018). To talk or not to talk: A review of situational antecedents of willingness to communicate in the second language classroom. System, 72, 226-239.

Appendix A: Observation scheme

In-class situations Language Teacher encouragement Peer influence Learner behavior Notes Beginning of class Teacher review Group discussion Whole class discussion Responding to questions Asking questions End of classAppendix B: Questionnaire

1. Which English course are you attending? o English 5

o English 6 o English 7 2. Which sex are you?

o Male o Female

o Would rather not say

3. I think it is difficult to speak English during the English lesson. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

4. I think it is difficult to give a presentation in English. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

5. I think it is difficult to discuss with my classmates in English. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

6. I think it is difficult to respond to questions in English. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

8. If the teacher asks me a question in English I respond in English. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

9. If one of my classmates speaks to me in English I respond in English. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

10. There is a lot in school that motivates me to speak English. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

11. There is a lot outside of school (out of school activities, friends, interests) that motivates me to speak English.

1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

12. My teacher motivates me to speak English in English class. 1 2 3 4 5

Disagree Agree completely

13. My classmates motivate me to speak English in English class. 1 2 3 4 5

Appendix C: Interview questions

1. Are there any specific situations where you feel less comfortable speaking English? 2. Are there any specific situations where you feel more comfortable speaking English? 3. Is the lesson I just observed a correct representation of how your class usually

communicate in English class?

4. Are you affected by your classmates in English class? 5. Are you affected by your teacher in English class? 6. What motivates you to speak English in English class?