Degree project in criminology Malmö University

120 credits Health and Society

Criminology, Masters programme 205 06 Malmö

WE JUST WANT TO PASS

-EXPLORING THE VICTIMIZATION OF

REFUGEES ON THE MOVE IN SERBIA

WE JUST WANT TO PASS

-EXPLORING THE VICTIMIZATION OF

REFUGEES ON THE MOVE IN SERBIA

SONJA LUNDGREN

Lundgren, S. We just want to pass. Exploring the victimization of refugees on the move in Serbia. Degree project in Criminology 30 credits. Malmö University: Faculty of Health and Society, Department of Criminology, 2018.

Refugee crisis of 2015 has strained European asylum system, and EU member states responded by closing the borders, leaving many refugees stranded in Serbia. Preventing refugees from accessing the territory of EU has led to breeching of the international protection mechanisms and victimization of refugees. Previous research on victimization of refugees is broad but it does not explore victimization on the move. The present study thus fills a research gap and by using descriptive statistics it strives to set foundation for further research. Aim of the study is to explore the prevalence and forms of victimization against the refugee population in Serbia and to provide better understanding of the phenomenon by investigating what types of victimization and perpetrators are refugees exposed to while

travelling. Quantitative method in form of descriptive statistics has been used to analyze the data collected from a sample of 153 refugees transiting through Serbia between December 2015 until December 2016. Results of the study show that the most common types of victimization are physical violence and pushbacks by police while irregularly crossing the borders. Further results show that young males are most commonly victimized, while valid results on women could not be drawn due to very low response rate. Since police violence is mostly connected to pushbacks, the great part of victimization of refugees seems to be systematic and carried out as a measure of border control. As such, refugees’ victimization is harsh breeching of humanitarian laws and international conventions. Although the research sample was small, some trends regarding the victimization of refugees on the move could be observed. The study concludes that further systematic research of the phenomenon is needed in order to prevent further victimization and

improve the international protection mechanisms and support systems for one of the most vulnerable groups.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

BACKGROUND...1

Introduction ...1

Previous research ...2

Theoretical framework ...2

THE PRESENT STUDY ...3

Aim ...3

Method ...4

Data ...4

Instruments ...4

Sample ...4

Analysis ...5

Research Ethical considerations ...5

RESULTS ...6

DISCUSSION ...7

Limitations ...9

CONCLUSION ... 10

REFERENCES ... 11

APPENDIX ... 13

BACKGROUND

Introduction

Over 1 million refugees1 have reached Europe during 2015, the year of European refugee crisis as it was labeled in the media (UNHCR, 2015). Such a high influx of people put a strain on European asylum system that was unable to cope with it. Individual countries in Europe such as Macedonia (FYROM), Croatia and

Hungary have responded to refugee crisis by closing their borders, hoping to stop refugees from entering their territories (International Rescue Committee, 2016). As pointed out by Jakulevičienė (2017), border closing resulted in the paradox where people fleeing from violence in their home countries suffered detentions, violence, human trafficking and other ill-treatment in the states of their first arrival (Medecins Sans Frontieres, 2016). Already being a highly vulnerable group, refugees are in greater risk than others to experience violence (Kalt, et al., 2013). Following a beaten track to the European Union, most of them have passed through Balkan countries. One of those countries is Serbia, a neighboring country to Macedonia (FYROM), Croatia and Hungary, located on the Western Balkan route refugees transit while fleeing to the EU. Serbia is also home to the highest number of internally displaced people in Europe. The number of refugees passing through Serbia has risen dramatically in the last several years. In 2008, only 77 asylum seekers were registered in the system, while that number jumped to 577,995 in 2015 (Bubalo, 2017). However, the actual number of people passing through the country is much higher, taking into account that not all asylum seekers were registered, due to entering the country irregularly.

By looking at the numbers of registered asylum seekers in 2015, it is easy to observe just how dramatic rise in persons in need of international protection Serbia faced. Due to the high pressure on the European asylum system that was unable to process all of the requests, EU Member States have firmly stated that Serbia, which is not a member of EU, is in fact a safe third country of asylum and capable of providing protection to asylum seekers. Results of this claim were preventing people from crossing borders and accessing EU territory (pushbacks),

1The Article 1 in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, defines a refugee as ’’ a

person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it’’ (United Nations; 1951:14).

Asylum seekers, on the other hand, are persons who applied for asylum, or requested a state’s protection but is still waiting for the request to be processed. They are often called ‘’prima facie’’ refugees. (UNHCR, 2011:para 44).

Term refugees will be used for the present study. Although all of the persons who data was collected on were de facto irregular migrants at the time of data collection, they had the intention of applying for asylum either in Serbia or in some of the EU countries. Therefore, the term refugees will be applied for them based on prima facie principle.

and even building a physical barrier on the southern Hungarian border, leaving people stranded in Serbia (BBC, 2016). Of course, although some of the stranded people were economic migrants, the majority of them were refugees - the most afflicted category of migrants, taking in consideration their legal status. As a vulnerable migrant population, refugees are exposed to the risks of sexual

assaults, trafficking, forced labour, military recruitment and other forms of abuse and violence.

Previous research

Previous research on victimization of refugees is broad, but it mostly focuses on victimization in host countries and host communities (Fisk, 2016). Scholars have pointed out that presence of large refugee populations can impact the probability of conflicts in host states (Lischer, 2005; Salehyan and Gleditsch, 2006), but as Fisk points out, it is important to consider how those conflict might affect human security and violence against civilians (Fisk, 2016).

Victimization of refugees is not an uncommon occurrence, and in a study on victimization of refugees in Africa, Cuéllar concludes that ‘‘refugees have been chronically plagued by violence and threats to their physical security during the entire half century history of the modern refugee protection system’’ (Cuéllar, 2006:10-11). Baban et al. (2016) took up important findings in their research on border politics and Syrian refugees in Turkey. According to their results, hosting countries such as Turkey categorize refugees as subjects of humanitarian

assistance rather than political agents, thereby stripping refugees of their political subjectivity and ability to enjoy international refugee protection programs. However, no study, to my knowledge, has investigated the victimization of refugees on the move, in active transit to their destination countries. This explorative study thus fills a research gap, that could potentially be used for identifying the blind spots in international protection policies that provide an opportunity for victimization to happen. By using descriptive statistics, this study strives to set good foundation for further research in this field of criminology. Theoretical framework

This study will focus on aspects of routine activity theory (RAT) that concentrates on circumstances under which crime occurs. Foundations of the RAT were

drafted by Cohen and Felson in 1979, suggesting that there are three elements that need to merge in space and time for a crime to be committed: a suitable target, a motivated offender and the absence of guardianship. Cohen and Felson’s focus was mostly on macro level due to their goal to explain escalation of crime rates in US after the Second World War. Their results show that escalation of crime was followed by changes in the routine activities of US citizens who became more public-oriented and therefore created opportunity for victimization (Cohen and Felson, 1979). As Podaná pointed out, RAT can also be applied for explaining victimization, despite the fact that it was created as a general framework for the analysis of crime occurrence (Podaná, 2017).

Another theoretical perspective that is similar to Cohen and Felson’s (1979) approach is Hindelang’s perspective that links routine activities to victimization through exposure to high risk situations (Hindelang, 1978). According to

Hindelang, he considers lifestyles that involve routine activities in public places, and particularly at night, to be highly risky in terms of victimization. He also states that a certain lifestyle in not simply matter of choice since it is influenced by cultural norms and structural constraints of society. Focusing his interest on socio-demographic factors that were assumed to affect victimization risk through influence on person’s choice of routine activities, Hindelang’s research shows higher levels of victimization for males, younger persons and single persons (Hindelang, 1978). The concept of a certain lifestyle having influence in the risk of victimization, combined with increased opportunity of exposure to motivated offenders and absence of guardianship is a popular perspective in victimology, also known as routine activities/lifestyles perspective (Podaná, 2017).

Early RAT focused only on individual factors in victimization, but later research brought community context into focus as well. This is due to social integration that is defined in terms of interpersonal networks. Therefore, if a person is

geographically mobile, relational structure and stability in personal relationship is low, and community attachments are not very strong. These high levels of

residential mobility give a motivated offender an opportunity not to be confronted by community’s informal social control. Sampson claims that ‘’by weakening community social integration, mobility increases rates of crime and deviance, especially by strangers’’ (Sampson, 1987:336).

Finally, Sampson’s research presents results of higher risk of violent victimization by strangers in communities that have low social integration/weak interpersonal networks, such as those with higher number of broken families or higher

residential mobility (Sampson, 1987). These results are therefore in agreement with Cohen and Felson’s research, who argue that ‘’ as activities take people away from their households or their primary groups, the circumstances favorable for direct-contact predatory violations, especially involving strangers, will probably occur with greater frequency’’ (Cohen and Felson, 1979:397).

THE PRESENT STUDY

Aim

Since victimization of refugees on the move is an understudied topic, this study aims to explore the prevalence and forms of victimization against the refugee population in Serbia and to provide better understanding of the phenomenon. The research questions through which the topic of this study will be investigated are:

1. What type of victimization are refugees exposed to while travelling? 2. Who are the perpetrators?

Method

Data

Data used for this study has been collected from Humanitarian Center for Integration and Tolerance (HCIT), a local Serbian NGO, one of UNHCR’s implementing partners in Serbia. HCIT specializes in providing legal aid and monitoring migration flows in the north of the country, on the borders with EU. Data that was collected by HCIT was originally used as a part of HCIT and UNHCR’s project aimed at protection of refugees in Serbia.

Original data was collected in the Serbian northern province of Vojvodina, in border crossings Horgoš, Adaševci, Subotica bus station and Šid transit accommodation center for refugees.

Data is consisted of 153 general questionnaires and 85 incident reports (refugees’ personal testimonies of victimization during transit to Europe) that were collected in the span of 1 year, from December 2015 until December 2016, during the peak of refugee crisis.

Instruments

The instruments used for the original data collection were UNHCR’s Questionnaire for interviews with persons (likely) in need of international protection (general questionnaires) and UNHCR’s Protection incident reports. General questionnaires include questions about personal information (age, sex, country of origin), information about entry and treatment in Serbia, as well as information about treatment in transit. All refugees participating in the study have responded to the general questionnaire. In cases when refugees responded

negatively about treatment in Serbia or other countries they transited, they were asked to partake in incident reports, and all agreed to it. Incident reports contain questions about victim personal information, type of incidents and detailed descriptions/narratives of those incidents. Descriptions of perpetrators are disclosed as well, including their names (if known) and physical descriptions. Since incident reports contain descriptions of victimization that may be unique and could potentially identify those involved, the author has not received

permission to use the narrative information, the permission was granted only for the statistical data that is needed in order to answer the research questions in form of descriptive statistics.

Sample

The sample of 153 refugees in total consists of 127 men and 26 women. Out of 153 refugees in total, 85 reported some form of victimization during their travel, which is 55,5%, a very high victimization rate. Victimized population in this research is consisted of 77 men and 8 women. The sex distribution among

victimized female participants is 9,4%, which is less than usual for Serbia, where the prevailing percentage of women among refugee population is 15% (UNHCR, 2017).

Analysis

As this is a descriptive study that has a goal of exploring a relatively unnoticed phenomenon of victimization of refugees on the move, descriptive analysis was conducted in order to explore distribution of variables needed for further analysis. Descriptive statistics are a straightforward process that easily translate results into distribution of frequency, percentage and averages, and are often used to identify further ideas for research since they may identify variables that can be tested (Creswell, 2013). Advantages of descriptive studies are richness in data that is collected in larger amounts as well as gathering in-depth information that may be either qualitative or quantitative in nature (Bernard and Bernard, 2012).

SPSS 25.0 computer-aided analysis was used to analyze the data (IBM SPSS Statistics 25, New York, US). Furthermore, frequencies were drawn on all the variables of the data collected in the present study. Variables that have been explored are age, countries of origin, gender, types of violence and perpetrators. The information about perpetrators and types of victimization obtained through incident reports has been analyzed by identifying different types of

violence/perpetrators, looking at their number of occurrences and grouping them accordingly. Findings are presented in frequency tables. Since there were no missing cases, valid percentage has been reported in the findings, providing an accurate picture of the distribution of obtained responses.

Research Ethical considerations

The testimonies were collected during HCIT’s field work in providing refugees with both humanitarian and legal help. The author of this thesis was present in the field with HCIT during 5 last months of 2015 as a part of an internship. All of the information in incident reports were collected personally by HCIT from refugees in forms of questionnaires, and the participants have given signed consent for the data to be used by the organization and UNHCR. All participants have been informed about the purpose of the questionnaire, they were informed that the participation is completely voluntary and that they could stop participating at any time without having to provide an explanation.

Consequently, the author of this thesis has requested permission to use the data both from the HCIT and UNHCR in order to conduct this study, and the

permission was granted from both organizations.

Due to the sensitive nature of information found in the incident reports, HCIT who provided the data has taken away all personal information before handing the data to the author. The information that has been taken away includes names of both victims, witnesses and perpetrators, phone numbers and signatures, in order to ensure the anonymity. Due to the fact that all personal information, as well as detailed narratives of incidents are inaccessible to the author, there are no risk and complications for the participants that may arise.

Victimization of refugees on the move is an understudied topic, and the aim of the study is to provide better understanding of the phenomenon in an under-explored research area. Once that is completed, future research can give suggestions and lay the road for improving the international protection and support systems for one of the most vulnerable populations, which they will benefit from in the future.

order to ensure safe passage for refugees, punishments for perpetrators as well as better assistance in both legal and humanitarian matters regarding refugees. The project was approved by the Malmo University ethical council on April 6, 2018. There were no objections for the implementation of the project to be performed (HS2018/Serial No 35).

RESULTS

What type of victimization are refugees exposed to while travelling?

When comparing both victimized and non-victimized respondents, there was nearly no difference in their age and countries of origin. Due to the fact that no major difference could be found, focus of this paper will be on victimized respondents only.

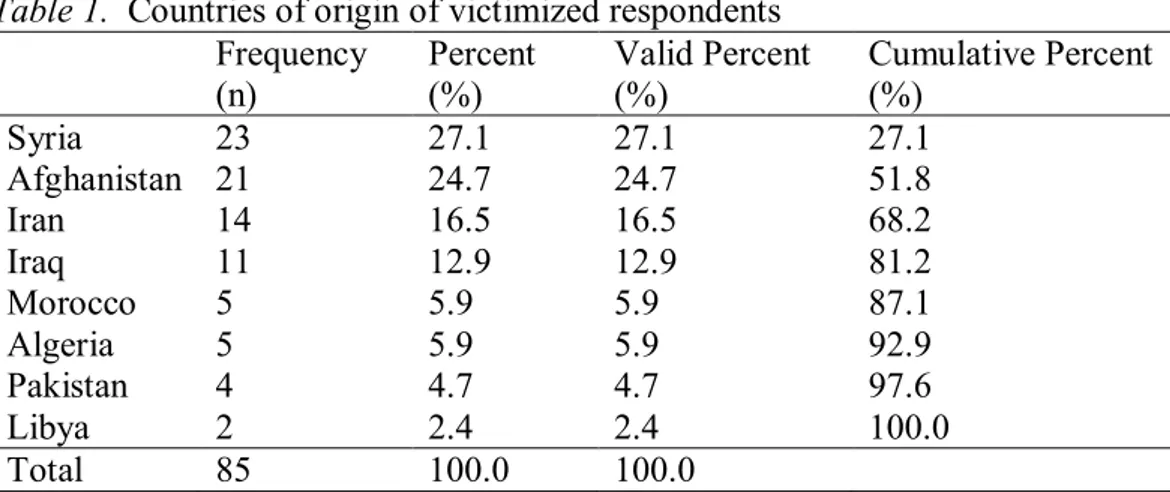

Age of respondents has been explored by dividing the sample into individuals over the mean age, which was 26.3. The countries of origin were primarily Syria, Afghanistan and Iran. The distribution of countries of origin is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Countries of origin of victimized respondents Frequency (n) Percent (%) Valid Percent (%) Cumulative Percent (%) Syria 23 27.1 27.1 27.1 Afghanistan 21 24.7 24.7 51.8 Iran 14 16.5 16.5 68.2 Iraq 11 12.9 12.9 81.2 Morocco 5 5.9 5.9 87.1 Algeria 5 5.9 5.9 92.9 Pakistan 4 4.7 4.7 97.6 Libya 2 2.4 2.4 100.0 Total 85 100.0 100.0

According to the collected data, the total of 85 participants reported 140 incidents, that can be categorized in 5 types. Those are physical violence, being prevented from entering a country (pushbacks), extortion/robbery, sexual violence and forced labour. Statistical analysis of distribution of victimization is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Types of victimization Frequency

(n) Percent (%) Valid Percent (%) Cumulative Percent (%)

Physical violence 66 47.1 47.1 47.1 Pushbacks 41 29.3 29.3 76.4 Sexual violence 3 2.1 2.1 78.6 Robbery/extortion 29 20.7 20.7 99.3 Forced labour 1 0.7 0.7 100.0 Total 140 100 100

Who are the perpetrators?

According to the processed data, 140 cases of victimization were conducted by 85 perpetrators. These results show that in some cases a single perpetrator has

victimized respondents’ multiple times. The most common perpetrators were police officers, followed by smugglers. Other perpetrators listed are other refugees, local population and personnel in transit accommodation/camps. The distribution of perpetrators is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Perpetrators Frequency (n) Percent (%) Valid Percent (%) Cumulative Percent (%) Police 59 69.4 69.4 69.4 Smugglers 13 15.3 15.3 84.7 Other Refugees 6 7.1 7.1 91.8 Locals 5 5.9 5.9 97.6 Personnel in transit accommodations/camps 2 2.4 2.4 100.0 Total 85 100.0 100.0

It has been attempted to look into the gender aspect as well and explore if there are any differences in victimization of refugees in relation to their gender. Based on the data reported by male refugees, the most commonly experiences

victimization during journey is physical violence, followed by pushbacks and robbery/extortion. Sexual violence was reported only three times, while forced labour was reported in one incident report. Moreover, some victimization types, such as pushbacks or forced labour, were not reported by female respondents at all. As it can be concluded from the number of responses, men are far more victimized than women. However, this conclusion should be interpreted carefully, since few women agreed to participate. Consequently, results regarding gender differences would be very limited and unreliable. Only 8 women agreed to answer the incident report questionnaire and report victimization, which constitutes solely 7.4% of the research sample. Out of 8 female participants, no one reported that

DISCUSSION

Results of both previous research and the current study indicate that refugees on the move are victimized population that is mostly viewed as recipients of humanitarian aid rather than political subject that should be protected by

international law. The results show that the most common types of victimization are physical violence and pushbacks by police while irregularly crossing the borders. Despite the fact that police officers are falling in the category of motivated offender according to RAT, labeling them in that way would not be completely fair, as it is the situation of irregular entry that is of their interest, not the people they cannot resist to victimize. After all, one can argue that they were working within the authorization of the law, and in order to control the irregular entry to their respective countries. However, police being the most common perpetrators is problematic as their status might have affected the reporting ability. Being ‘’protected’’ by the law while acting as border keepers, they are unlikely to be liable in cases of overstepping the necessary physical engagement in contact with persons trying to irregularly enter the country. Therefore, it is likely to assume that the actual numbers of physical violence are higher, and refugees might fear retaliations or legal trouble if they were to report police officers as perpetrators.

However, it must not be forgotten that all countries in Europe, both member states of the EU as well as those that aspire to become members, are signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. Problems arise when

countries loosely interpret the Convention to maximize their border protection and justify pushbacks. Namely, the article 31 of Refugee Convention prescribes that ‘’ The Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened in the sense of Article 1, enter or are present in their territory without authorization, provided they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence’’ (United Nations: 1951:29). As the refugee crisis showed, the major problem in

misinterpretation of this article is formulation- refugees need to come directly from a territory where their life of freedom was threatened. Humanitarian organizations and human rights activist agree that the formulation ‘’directly’’ is referring to the country of origin and legal residence of refugees, despite the number of countries one transited on the way to their destination country. They also claim that misinterpretation of this article is breaching of the Refugee

Convention, while European countries stay firmly by opinion that refugees should seek asylum in the first safe country they ‘’directly’’ arrive to from their countries of origin (Trauner, 2016).

Most commonly victimized group in the sample are young males which is in agreement with Hindelang’s theory and research that points out males and young persons as having higher victimization rates (Hindelang, 1978). Furthermore, RAT links routine activities to victimization through exposure to high risk

situations, and results of this research are again in accordance with it. Namely, the travel of refugees if rich in high risk situation and behaviors, from travelling across the Mediterranean Sea in overcrowded boats to cutting the border fence and being chased by police dogs (Turhan and Armiero, 2017).

Results of this research also support Sampson’s theory of high risk of violent victimization by strangers in communities with low social integration. This is especially prominent in situations of fleeing from danger and moving irregularly. The possibilities of having social integration are minimal, if any in those

circumstances, since there is no stability and continuity in relationships. Consequently, having community attachments is impossible and if there is no community one can relate to, there is no informal social control. Without informal social control that acts like a guardian and protects one from victimization,

refugees are in high risk of violent victimization, especially by strangers (Sampson, 1987).

Although some differences in types of victimization in relation to gender were observed, they were not sufficient for a relevant analysis. This was primarily due to response rate among female participants being very low, which is a common issue observed by other researchers on female refugees in Serbia. NGO Atina’s previous research indicates that female refugee population is problematic in terms of providing reliable answers to researchers. While conducting another research on female refugees in Serbia, it was noticed that women who travel with family members are more open to sharing experiences of violence than women who are travelling alone. Furthermore, it was also observed that the women travelling alone often report that they are accompanied by their partners since they believe that it would deter potential perpetrators from victimizing them (Marković and Cvejić, 2017). Previous research also suggest that victims often conceal the perpetrator if it is a partner or a husband, and report violence as if it was committed by someone else. Moreover, reports from the field exhort that some participants do not see violence as a negative matter that harms and is unallowed, at least within the framework of both Serbian and European law (Marković and Cvejić, 2017). Although other researchers have made similar suggestions as well (Bubalo, 2017), it is only an assumption, which requires further analysis. Since all of the women in sample of this study suffered some kind of violence despite being accompanied by their partners/family members, it is clear that the presence of guardianship does not make them less vulnerable or protects them from violence in a higher extent (Marković and Cvejić, 2017).

Limitations

There are limitations to this study that could compromise its validity, and some are related to the method. Although this is an explorative study and descriptive statistics were chosen for their ability to gather detailed information and help identify ideas for further research, this method has some weaknesses. One of them is certainly leaving results open to interpretation, since no cause and effect could be found (Creswell, 2013). Out of 1 million refugees passing thorough Serbia in 2015 (UNHCR, 2015), only 153 agreed to participate in data collection carried out by HCIT, and only 85 reported victimization, making this sample rather modest. Although it was impossible to interview majority of refugees due to the quick transit through the country, and sometimes unfavorable conditions in the field and language barriers, it was observed that the majority of them were unwilling to talk to the HCIT staff and would simply leave when approached. They explained that this was due to the wish to continue travelling as fast as possible and the fear they would be halted on their journeys if any incidents would be reported to the authorities. Consequently, the truthfulness of the

descriptive studies as participants may not be truthful or may not behave naturally if they are observed. Limitation in the data is that women are underrepresented, thus making the sample size small. Therefore, no meaningful comparisons in relation to gender could be conducted. However, as women seem to be victimized despite being accompanied by their partners, victimization of female refugees on the move is important for future research and should be explored additionally.

CONCLUSION

The aim of the present study was to explore types of victimization and

perpetrators refugees are exposed to while travelling and, despite the limitations, some trends in types of victims, victimization and perpetrators could be observed. As the results show, physical violence carried out by police is one of the most common ways to victimize refugees. Since police violence is mostly connected to pushbacks, as data and results of this study suggest, the great part of victimization of refugees seems to be systematic and carried out as a measure of border control. As such, refugees’ victimization is harsh breeching of humanitarian laws and international conventions. Therefore, further systematic research of the

phenomenon is needed in order to prevent further victimization and improve the international protection mechanisms and support systems for one of the most vulnerable groups. Further research would be beneficial in order to support the rule of law, especially regarding implementation of regulations in Refugee Convention. Finally, further research on this topic is crucial for supporting better cooperation among countries in order to ensure safe passage for refugees,

punishments for perpetrators as well as better assistance to refugees in both legal and humanitarian matters.

REFERENCES

Baban, F., Ilcan, S. and Rygiel, K. (2016). Syrian refugees in Turkey: pathways to precarity, differential inclusion, and negotiated citizenship rights. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(1), pp.41-57.

BBC News. (2016). Migrant crisis: Hungary's closed border leaves many stranded - BBC News. (Online) http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34260071 (Accessed 5 February 2018).

Bernard, H. R., & Bernard, H. R. (2012). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage.

Bubalo, R. (2017). Koridor nade: Aktivnosti Humanitarnog Centra za Integraciju i Toleranciju u izbegličkoj krizi 2015-2017. Novi Sad: HCIT.

Christensen, A. (1995). Comparative Aspects of the Refugee Situation in Europe, International Journal of Refugee Law Special Issue, Oxford University Press. Cohen, LE. and Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review 44(4): 588–608.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Cuéllar, Mariano-Florentino. (2006). ‘‘Refugee Security and the Organizational Logic of Legal Mandates.’’ Georgetown Journal of International Law 37:583. Fisk, K. (2016). One-sided Violence in Refugee-hosting Areas. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(3), pp.529-556.

Hindelang, MJ. Gottfredson, MR. and Garofalo, J. (1978). Victims of Personal Crime: An empirical foundation for a theory of personal victimization.

Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

International Rescue Committee (2016), The Refugee Crisis in Europe and the Middle East A Comprehensive Response (online)

https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/911/irccrisisappealcompositer evaugust.pdf (Accessed 17 January 2018).

Jakulevičienė, L. (2017). MIGRATION RELATED RESTRICTIONS BY THE EU MEMBER STATES IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE 2015 REFUGEE “CRISIS” IN EUROPE: WHAT DID WE LEARN?, International Comparative Jurisprudence, 3(2). (online)

https://www3.mruni.eu/ojs/international-comparative-jurisprudence/article/view/4718 (Accessed 17 Jan. 2018).

Kalt, A., Hossain, M., Kiss, L. and Zimmerman, C. (2013). Asylum Seekers, Violence and Health: A Systematic Review of Research in High-Income Host Countries. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3) (online)

http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.mau.se/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid= 765cdd53-2abb-4656-ae41-97b8cf6f9a4f%40sessionmgr4010 (Accessed 18 Jan. 2018).

Lischer, Sarah Kenyon. (2005). Dangerous Sanctuaries: Refugee Camps, Civil War, and Dilemmas of Humanitarian Aid. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Marković, J. and Cvejić, M. (2017) Nasilje nad ženama i devojčicama u

izbegličkoj i migrantskoj populaciji u Srbiji. Beograd: Atina.

Medecins Sans Frontieres (2016), Obstacle Course to Europe: A Policy-Made Humanitarian Crisis at EU borders, (online)

https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/sites/usa/files/2016_01_msf_obstacle_cou rse_to_europe_-_final_-_low_res.pdf (Accessed 17 January 2018).

Podaná, Z. (2017). Violent victimization of youth from a cross-national perspective. International Review of Victimology, 23(3), pp.325-340. Salehyan, Idean, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. (2006). ‘‘Refugees and the Spread of Civil War.’’ International Organization 60 (2): 335-66.

Sampson, RJ. (1987) Personal violence by strangers: An extension and test of the opportunity model of predatory victimization. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 78(2): 327–356.

Trauner, F. (2016). Asylum policy: the EU’s ‘crises’ and the looming policy regime failure. Journal of European Integration, 38(3), pp.311-325.

Turhan, E. and Armiero, M. (2017). Cutting the Fence, Sabotaging the Border: Migration as a Revolutionary Practice. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 28(2), pp.1-9.

United Nations General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 28 July 1951, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 189.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2011), Handbook and

Guidelines on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, HCR/1P/4/ENG/REV.3

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Over one million sea arrivals reach Europe in 2015, (online)

http://www.unhcr.org/5683d0b56.html (Accessed 17 January 2018).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2017), Interagency Operational Update Serbia April 2017.

APPENDIX

Appendix. Decision of the Ethics Council regarding the implementation of student project.

1(1)

Malmö University / Faculty of Health and society Ethics Council

STATEMENT

2018-04-06 HS 2018/löp nr 35

Postadress Besöksadress Tel Fax Internet E-post

Malmö högskola Fakulteten för Hälsa och samhälle 205 60 Malmö

Malmö sjukhusområde Jan Waldenströms g 25

040-665 74 54 040-665 81 00 www.mah.se Helen.olsson.hs@mah.se

Project: Victimization of refugees on the move

Student: Sonja Lundgren

Supervisor: Eva-Lotta Nilsson

Presenter of case: Petri Gudmundsson

Ethical Council Statement, HS 2018/Serial No 35, 2018-04-06 Thank you for an excellent application!

The ethical council at the faculty of Health and Society has, from an ethical point of view, nothing to object for the implementation student project to be performed.

Good luck in the process! On behalf of the Ethical Council

Petri Gudmundsson

PhD, Associate professor, Senior lecturer Member of the Council