Engaging Teenagers in Online

Ethnographic Participatory Design

Andreea Strineholm

Master’s Thesis in Innovation and Design, 30 credits Course: ITE500

Examiner: Yvonne Eriksson Supervisor: Karolina Uggla

School of Innovation, Design, and Engineering Mälardalens University

ABSTRACT

The aim of this master’s thesis is to explore the implications of using online ethnographic participatory design in studying communication with teenagers in the context of Carbon Dioxide Theatre, a climate action research project. By developing multiple methods, tools and activities, the implications are understood throughout the teenagers’ engagement in collaborating and co-creating using online media. The findings are then organized based on the teenagers activity from three perspectives, by following the medium, the story and the feeling. The medium shows how social media platforms such as Snapchat and Facebook Messenger can be used in order to establish a valuable collaboration with the teenagers, the story presents how the teenagers are expressing their views, thoughts and dilemmas regarding the climate action topic, co-creating one Instagram account while the feeling offers emotions raised during the process. Ultimately, inspired from the study process, the paper suggests a design method for online ethnographic participatory design data collection, consisting of a set of cards and maps that can be utilized as a guiding tool in organizing and understanding the empirical data within an exploratory research context.

Keywords:

online ethnography, participatory design, teenagers, co-creation, social media, online communication, collaborative study, climate action, design method.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Conducting the research project along with writing the thesis has been an emotional journey, full of ups and downs, during which I have learned many lessons that I will bring with me for the rest of my life. This journey could not be experienced as it was without the help of both my supervisors, Karolina Uggla from Mälardalen University, and Jennie Schaeffer from Västmanland County Museum, who have been supporting me throughout the process. You believed in my ability to design a comprehensive study even when I felt insecure about being able to connect the dots, dots that generated in the end the valuable results presented in this paper. I also want to show my appreciation to the teenagers and the project stakeholders, who made me view life from new intergenerational perspectives, taught me emotional lessons and acknowledged the benefits of being part of this online collaboration, as well as to my teachers and colleagues from the Innovation and Design departament who gave me the opportunity to develop myself providing a safe environment for designing innovative ideas. Last but not least I am grateful for my family and friends who showed their empathy and encouraged me to continue working, considering that there were two big “projects” under development during this period, both my research study and my baby.

FOREWORD

This project is about my knowledge developed during the past ten years in the field of design and art and how to use it in order to create new understandings within different contexts in life and provide support for those in need. When I first heard about the Carbon Dioxide Theatre project I was both excited and worried at the same time. The excitement came from the beauty of this project, combining theatre methods with participatory design and aiming to understand the teenagers perspective regarding a hot topic today while involving them throughout the whole process. On the other hand I felt so unsure about how I will be able to find my own path along a project that was already established half a year before, since the summer of 2018. However, meeting the team and understanding deeper the coordinates of the project, I started to see many directions I could take for my master’s thesis study, having the opportunity to provide value for both project and academia. Thus, the topic of this paper began as a necessity I discovered in the practical field to establish the online communication with the teenagers involved in the project, which I combined further with my interests in working around solving challenges together with people, as well as fighting for a better relationship between humans and nature. The text that follows presents theoretical concepts applied on valuable empirical material, along with my personal reflections that aim to guide you throughout this emotional journey I have experienced during the four months of study.

Andreea Strineholm Västerås, May 2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I 1

1| INTRODUCTION 1

1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND 1

1.1.1 Climate action urgency and teenagers 1

1.1.2 Co-production Context 2

1.2 AREA OF RESEARCH FIELD AND AIM 4

1.3 RESEARCH APPROACH AND QUESTIONS 5

1.4 PREVIOUS RESEARCH 6

1.5 SCOPE AND DELIMITATIONS 8

1.5.1 Recruitment and participants 8

1.5.2 Social media platforms 8

1.5.3 Timeframe 9

1.5.4 Innovation and Design 9

1.6 STRUCTURE 10

2| THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 11

2.1 ONLINE ETHNOGRAPHY 11

2.1.1 What is online ethnography? 11

2.1.2 What is the time-space framework? 12 2.1.3 What is the ethnographer’s role in online studies? 13 2.1.4 How can the online ethnographic methods be used? 14

2.2 PARTICIPATORY DESIGN 15

2.2.1 What is participatory design? 15

2.2.2 What is the participatory design researcher’s role? 15 2.2.3 What are the participatory design methods? 16

3| METHODS 19

3.1 RESEARCH PROCESS 19

3.2 DEVELOPING INQUIRY 20

3.2.1 Methods for conceptual phase 20

3.3 EXPLORING 22

3.3.1 Methods for empirical phase 22

3.4 SYNTHESIZING 25

3.4.1 Methods for analytic phase 26

3.5 RESEARCHER’S POSITION 28

PART II 31

4| FINDINGS 31

4.1 STRUCTURE 31

4.2.1 Email 32

4.2.2 Physical meetings 33

4.2.3 Facebook private group 35

4.2.4 Snapchat private group 36

4.2.5 Facebook Messenger private group 37

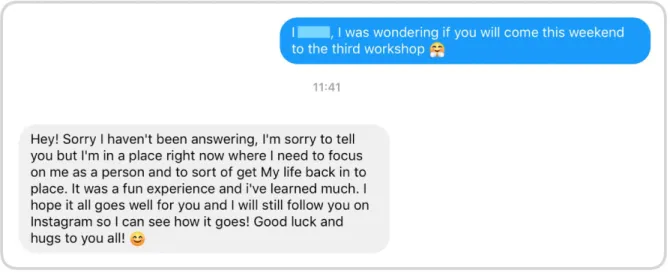

4.2.6 Private individual chat 40

4.2.7 Instagram 41

4.2.8 Summary 41

4.3 THE STORY 42

4.3.1 Climate action Snapchat exhibition 43

4.3.2 @co2theatre 45

4.3.3 #30daysclimatechangechallenge 46

4.3.4 Insta calendar 50

4.3.5 Stories outside the project 51

4.3.6 Summary 52

4.4 THE FEELING 53

4.4.1 “I like, I wish” 53

4.4.2 Reflection session 56

4.4.3 The “turtle” voting moment 58

4.4.4 Individual experiences 60

4.4.5 Summary 61

4.5 “GET IT” CARDS METHOD 62

5| DISCUSSION 65

5.1 RESEARCH CHALLENGES 65

5.1.1 Challenges in online ethnographic research 65 5.1.2 Challenges in participatory design research 66 5.1.3 Co-production in the research field 66 5.1.4 Teenagers in the research project 67

5.1.5 Research process 68 5.2 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS 69 5.3 FUTURE RESEARCH 70 6| CONCLUSIONS 71 7| REFERENCES 73 8| APPENDICES 78

8.1 APPENDIX A: RECRUITMENTING INFORMATION 78

8.2 APPENDIX B: AGREEMENT FORM 79

8.3 APPENDIX C: PRE-STUDY SURVEY RESULTS 80

PART I

1

|

INTRODUCTION

1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND

1.1.1 Climate action urgency and teenagers

The climate is changing and many of us have heard at least one time about the urgency of taking action and fighting towards a more sustainable environment and society, due to the big catastrophes that are expected if not. Moreover, the Paris Agreement that brings all nations into a collaborative effort to combat climate change, draws attention to the global temperature rise this century, aiming to keep it below 2 degrees Celsius and pursuing the effort to narrow it even more to 1.5 degrees Celsius (UNFCCC, 2018). There are also the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports that take into consideration the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), underpinning the scoping elements of: (1) global stocktake (scientific information regarding the state of the climate system), (2) interaction among emissions, climate, risks and development pathways, (3) economic and social costs and benefits of mitigation and adaptation in the context of development pathway, (4) adaptation and mitigation actions in the context of sustainable development and (5) finance and means of support (IPCC, 2017).

In 2018, VICE, (a Canadian-American magazine) has published a documentary with social theorist Jeremy Rifkin, who has worked for the past 50 years with energy issues, discussing about how we are running out of time when it comes to climate changes (Lutteman, 2018).

Based on these global facts and warnings, on September 2018, a 16-years-old swedish girl named Greta Thunberg (in the moment of writing this paper, being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize), struck outside the Swedish parliament for climate action and her protest has been published at BBC (the British Broadcasting Corporation) (Ahmed and Abdi, 2018). Since that moment, a global phenomenon of teenagers striking from schools for a better future is taking place, organized in public manifestations. Influenced by Thumberg’s speech, teenagers’ arguments are mostly regarding the very less attention that the adults are paying to environmental issues that surround us today, especially coming from the politicians. These events aim to transform the climate policies and promised solutions into actual actions. Interviewed by the BBC, one of the teenagers said that “there is actually no point going to school if our world is going to die!” (BBC, 2019).

Within this context, the current paper is based on a collaborative research project where young citizens from Västerås city, in Sweden are engaged in a critical reflection around social norms and climate goals through participatory methods. However, within this collaborative research project which implies the presence of other researchers and designers, the current master’s thesis is focusing on a subproject, aiming to understand how teenagers are using online tools in order to communicate the urgency to take action around climate issues and how these online media are influencing their actions, the data is collected with an online ethnographic approach. The aim of this paper will be further discussed in this chapter, along with the description of the study context.

From the beginning, to be able to make the differentiation between the collaborative research project (the Carbon Dioxide Theatre project) and the thesis ethnographic study, they will be mentioned as following: Carbon Dioxide Theatre project will become “ CO 2 Theatre project” and

the thesis study will be found as “OEPD study” (Online Ethnographic Participatory Design study).

1.1.2 Co-production Context

The OEPD study is a co-production designed in collaboration with the CO2 Theatre, a project led by Västmanland County Museum from Västerås, Sweden (VLM), Interactive Research Institute of Sweden (RISE Interactive Eskilstuna) and Syddansk University from Denmark, which has the goal to engage teenagers in a participatory theatre project, exploring social norms and environmental issues, working directly towards the European Sustainable Development Goal number 13: Climate Action, focusing on its subgoal “to improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity to climate change” (Sustainable development, United Nations, 2018). Furthermore, the project is financed by Formas, a Swedish government research council for sustainable development, fitting within its responsibilities of sustainable societies and environment (Schaeffer et. al., 2018).

With an inclusive and educational objective, the project stimulates negotiation around climate issues to analyze current research on the limitations of CO2 emissions (Roskström et. al., 2009) and individual carbon footprints (Wessman and Reitsma, 2018). According to the project funding application, there are four criteria involved in this project:

“(1) participatory theatre and co-design methods to engage young citizens in negotiating social norms and understanding their possible impact on CO 2 emissions; (2) using the museum’s existing collections to reflect on the temporality of social norms; (3) making the climate goals come to life with participatory methods in which current research on quantifying your carbon footprint, life cycle assessment and required limitations to our carbon emission are socially explored; (4) developing new practices for museums involving participatory methods in order to engage young citizens in climate research.” (Schaeffer et. al., 2018, p. 3)

The four main actors have different roles (figure 1) during the time frame of one year: VLM contributes by providing the space (where the four physical workshops will take place) and

resources (from collections to contextual knowledge regarding cultural heritage, exhibitions, public services and so on), RISE Interactive is focused on experimental IT and design research (aiding the project with their expertise on prototypes, CO2 consumption and life cycle assessment), and the third party, SDU, provides the theatre experts (who facilitate the workshops and stimulate the dialogue with the target group). The fourth party is represented by the teenagers, a group of 15 highschool students from Västmanland region with the ages between 15 and 20 years old. They have been recruited from different theatre groups, with the free will to apply for this project. Moreover, the CO2 Theatre project offers the possibility for further collaboration during the summer when the teengaers can choose to participate on summer job positions within the museum.

Figure 1: Project diagram and stakeholders’ roles.

In order to show a broader view on the CO2 Theatre project, the 4 workshops are described briefly. The first workshop represents the kick-off moment in exploring the social norms through stories around CO 2 with the teenagers, the second one explores objects from the

existing museums’ collections along with RISE prototypes, the third one facilitates carbon dioxide theatre together with the teenagers, museum staff and people outside the project, while the last workshop aims to reflect around the process and to identify possible themes for the

PopUp exhibition. However, within this one year project, the OEPD study is conducted until the third workshop, having a timeframe of four months that is shown later on in this chapter. Within the CO2 Theatre project, my position can be understood from multiple perspectives,

which also affect the research outcome, being part of the academy as a master’s student in Innovation and Design, having a designer position within the OEPD study, being employed as project assistant within VLM and collaborating as a researcher with the other CO2 Theatre project stakeholders. More about the researcher’s roles and positions will be found in the method chapter.

1.2 AREA OF RESEARCH FIELD AND AIM

This study aims to explore the use of an online ethnographic participatory design approach in studying communication with teenagers. It is situated at the cross intersection between two main research approaches (figure 2) represented by online ethnography, which is explored through the use of social media, and participatory design, developed within the CO 2 Theatre project,

designed around the climate action theme.

Figure 2: Area of research

Within the CO2 Theatre project, the teenagers are taking part of four workshops, in which

together with the other stakeholders are exploring and developing new knowledge regarding today’s environmental issues and social norms, finalizing the project with an exhibition or another form of communication of this knowledge. The purpose of the OEPD study is to continue together with the teenagers the dialogue developed during the workshops, and bring it into online environments throughout different methods, activities and tools, guided by the hybrid methodology of online ethnographic participatory design.

The contribution of this paper is related to two fields: the first one is represented by academia, creating new knowledge regarding teenagers’ communication aspects in online environments in a participatory context, as well as the development of a new data collection method based on the experience generated throughout the study, and the second one is produced as a contribution for the practical field, providing value within the CO 2 Theatre project, as most of the activities

together with the teenagers are designed towards the project theme, aiding the process within the workshops.

1.3 RESEARCH APPROACH AND QUESTIONS

In order to define the OEPD study, online ethnography and participatory design are used as research approaches, providing both theoretical framework and methodological guidance for understanding the communication with teenagers and engaging them in collaboration, focusing on the medium, the story and the feeling that will be developed during this study, within the online environment. These two emerging research approaches offer the possibility to position the study around people’s needs through design practices, while taking ample views and setting broader scopes in analysis.

Considering online ethnography and participatory design as the OEPD study approach, along with the complexity of studying online communication with the teenagers, an exploratory research question is considered. Thus, the main research question is:

“What are the implications of using online ethnographic participatory design in studying

communication with teenagers?”

This main question represents the meta-analysis of the study, offering an open understanding of the cultural phenomenon, the people, as well as their actions. However, since the word “implication” is described as “the conclusion that can be drawn from something, although it is not explicitly stated” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2019) , there is a need of considering a second research question, that views the OEPD study from a practical perspective in accordance to the CO2 Theatre project scope:

This second question aids the process of data analysis and creates the base for underpinning the study findings. The findings are structured starting from the second research question, and it consists of three main perspectives, by following the medium, the story and the feeling in relation to the teenagers. Each of these three perspectives answer its own sub-question, in order to provide comprehensive knowledge in regard to the main research questions.

The medium: “How are the online media used as tools for collaboration and co-creation with teenagers?” The story: “How are the teenagers making their experiences visible within the project, as well as outside the

project’s context?”

The feeling: “ How are the teenagers experiencing the involvement in online ethnographic participatory design, and expressing their feelings?”

The purpose of structuring the findings based on these three perspectives is to show a broader knowledge that will be developed during the study, considering also key aspects on the teenagers’ actions, the way they are navigating within online media, sharing their knowledge and expressing their feelings within this co-designed context. Both online ethnography and participatory design are research approaches with an exploratory mindset, thus the data collected during the process includes complex knowledge that would be represented throughout this structure of the findings. These approaches are also explored as research and design methods, inspiring the creation of a card based method, used as tool for recording and analysing the empirical material collected from online environment.

1.4 PREVIOUS RESEARCH

In this subchapter the focus is on understanding how the concepts of online ethnography and participatory design have been used in previous studies as research approaches, in relation to the online communication and participants’ engagement in research projects.

The term “online” used within the ethnography field is usually referring to studies that, according to Caliandro (2014), have been conducted considering “blogs, forums, as well as social networking sites such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+, and LinkedIn as social media platforms.” (p. 552). As people started to use these media in their everyday practices, the social researchers found it fruitful for their studies, especially the ethnographers for whom “it is not longer imaginable to conduct ethnography without considering online spaces” (Hallett and Barber, 2017, p. 307). Thus, several styles of online ethnography have been developed in the recent years, as reviewed by Caliandro (2014), such as: cyber-ethnography (Escobar, 1994), virtual ethnography (Hine, 2000), Internet ethnography (Miller and Slater, 2001), digital ethnography (Murthy, 2008), expanded ethnography (Beneito-Montagut, 2011), ethnography of the virtual words (Boellstorff et. al., 2012), showing its flexible method approach.

Online ethnography can be used as a research approach for understanding the participants from both general and specific perspectives, by mapping their sociocultural context (Hine, 2015) and by following their everyday practices (Dirksen, Huizing and Smit, 2010). On the general side, research studies show this model as represented by the online world with its communities, that are real and complex formations similar to the offline one (Jones, 1995; Kavanaugh and Patterson, 2001; Komito, 1998), and how the ethnographers are observing and participating in this social practices (Caliandro, 2014). From the specific perspective, following everyday practices represents the paradigm of multisited ethnography, in which the ethnographers focus on the participants’ movements across online spaces (Marcus, 1995).

In order to understand how these new communication and interaction media can be studied, there are the Digital Methods conceptualized by Rogers (2013) that aim to inspire the researchers in finding “new methodological strategies and conceptual frameworks that are useful for mapping the social structures and cultural processes being deployed in social media environments.” (Caliandro, 2014, p. 557).

From the participatory design perspective, several studies are focused on studying the online media. Halskov and Hansen (2015) present in their paper how participatory design is represented in the new domains, mostly belonging to technological developments. They claim that nowadays participatory design is used in very uncommon media, “thus contributing to the field by implementing PD [participatory design] techniques, or questioning prevailing assumptions.” (p. 84).

Part of this societal development approach from a participatory design perspective are also the online media. Mainsah and Morrison (2012) examine how social media can be adapted from a youth point of view in studying their civic engagement. Johnson and Hyysalo (2012) are also another example of researchers whose focus is on understanding the strategies having long-term user involvement on social media. Moreover, other studies consider social media as an opportunity to foster participation on participatory design projects (Duffett-Leger and Beck, 2018).

However, when it comes to participatory design used as a method in an online research project, there is a need of exploring connectivity with end-users to evaluate if this approach can be completed using online collaboration tools (ibid).

Along these lines, the current study is contributing from an academic perspective by filling the gap between online participatory design which aims to co-create together with the practitioners and conducting the study by following an ethnographic approach in exploring these online activities and understanding the teenagers’ perspective.

1.5 SCOPE AND DELIMITATIONS

1.5.1 Recruitment and participants

Being a satellite project, the participants within the OEPD study are the same as within the CO2 Theatre project. When discussing the research participants, I am referring to the teenagers that have taken part of the study. Two months before the first CO2 Theatre project workshop took place, we started the recruitment process of the teenagers. All of them are between 15 and 20 years old, are enrolled in high schools from the Västmanland Region, and have an interest in taking action towards climate change (see appendix A for the recruitment information created by VLM). The specific requirements to be in high school and to have this certain age, are in relation with the summer job positions offered by Västerås Municipality as being part of the project. Around 20 teenagers have sent their applications in the first month, although before the first workshop the number lowered to 15. Until the end of the OEPD study, 9 tennagers remained fully active within the both the CO2 Theatre project and this study.

Alongside with the CO2 Theatre project’s teenagers’ group, the OEPD study is also

understanding the knowledge produced in collaboration, considering the project stakeholders needs within specific contexts. This group is formed by 10 to 15 people, with the ages between 25 and 67 who are taking part of the workshops and thus influencing the activities designed for the OEPD study.

1.5.2 Social media platforms

The term “social media” is usually referring to “online means of communication, conveyance, collaboration, and cultivation” in between systems of people or communities, who are using technological abilities (Tuten and Solomon, 2014, p. 4).

Throughout the OEPD study, the concepts of “medium” and “media” are used to describe the space where different actions take place, while the words “platform” and “channel” define the social media umbrella of a specific medium, used in a general sense such as Snapchat, Facebook or Instagram as online applications.

There are multiple social media used for collaboration and co-creation together with the teenagers. Snapchat private group represents the first medium, created by the teenagers and is mainly used for knowledge transfer, in relation to its features. Facebook Messenger private group is the medium created as a complement to the Snapchat tool, considering its longer time character compared to the first one. Social media is also represented by Instagram, which is mostly applied as a co-creation tool for sharing thoughts regarding the discussions developed during the CO2 Theatre project workshops.

1.5.3 Timeframe

The OEPD study timeframe is designed in relation to the CO2 Theatre project first four workshops (workshop 1: 8-9th of February, workshop 2: 5-6th of April, workshop 3: 26-27th of April, workshop 4: 23rd of May). Figure 3 shows the timeline for both, the empirical data collection and the study development.

The first dimension is extended over three and a half months, starting in the middle of January 2019 and finishing in the middle of April the same year, even though the online project as such is continuing until the summer, keeping active the communication with the teenagers. The empirical data collection presents the online platforms used as communication media for this study, along with the methods, activities and tools that have been developed during this time.

Figure 3: The OEPD study timeframe.

The study development dimension occurs within four month of research, being conducted in three stages: developing inquiry, in which the conceptual phase is developed, exploring, which coincides with the empirical phase, and synthesizing, when the analytical phase is established. These three stages are explained in the method chapters, along with all activities represented in these moments.

1.5.4 Innovation and Design

From an Innovation and Design perspective, the OEPD study is connected to the research fields of online ethnography and participatory design, following the four core principles of successful innovation as presented by Kumar (2013): (1) build innovation around experiences, (2) think of innovation systems, (3) cultivate an innovation culture and (4) adopt a disciplined innovation process. The first principle is created around the teenagers experiences in relation to the climate

action theme and online participation, the second one is presented through integrating them within the research context, while the third principle is connected to the exploration of new practices within both practice and research following the merged online ethnographic and participatory design research approaches. The last one, innovation and design processes, is related to the broad research umbrella made in collaboration with other institutions, and how all the actors (in this case the CO2 Theatre project stakeholders) are adopting a new mindset in using the online ethnographic participatory design approach as guidance in future projects. Thus, the stakeholders benefit from the results that emerged through the online ethnographic participatory design approach, adapting their practices in engaging teenagers in online collaboration and co-creation.

Moreover, inspired by the online ethnographic participatory design research process, this study suggests a design method for data collection and analysis, which consists of a set of cards and maps that can be used in order to gather knowledge from participants, organizing the findings by following three criteria: the medium, the story and the feeling. The “Get it” cards method aims to become a companion throughout the research process for those who want to follow an exploratory research path within online ethnographic participatory design, facilitating the collection of empirical material, as well as organizing and synthesizing it towards relevant findings and valuable conclusions. The method is also part of the innovation and design field, being an end product that concludes this exploratory research process, engaging multiple actors and responding to both the practical and the academic need. The “Get it” cards method is under development and its prototype will be presented in the end of the findings chapter.

1.6 STRUCTURE

The paper is divided into two parts. The first part (chapters 1, 2 and 3) presents the theoretical perspectives of the research project, discussed in relation to the project design and empirical data. The second part (chapters 4, 5 and 6) describes and analyses the empirical data, and conducts discussions about different aspects and lessons learned during the OEPD study.

This is a study that focuses on understanding how two methodologies can emerge into a hybrid one. In chapter 2 the focus is on molding the theoretical framework in order to understand general aspects of two methodologies (online ethnography and participatory design). The methods chapter (3) creates the transition between meta-text and empirical material, presenting the research design process along with the activities that have been conducted during the OEPD study, while chapter 4 develops further the empirical data into valuable findings. The findings chapter (4) shows also the “Get it” cards method for data collection or analysis, created based on the study experiences. The discussion chapter (5) brings up challenges and lessons learned throughout the study, regarding online ethnography and participatory design, co-production, social media and ethics, under the research questions umbrella.

2

|

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 ONLINE ETHNOGRAPHY

Today’s communication is taking place in two different environments, the physical one and the virtual one, and the researchers role is to understand how to recognize both advantages and disadvantages. As Garcia et. all. (2009) argue in their paper, the communication that is taking place through technological support become more visible in our everyday life, which make the distinction between offline and online worlds hard to separate. These two environments have increasing interaction with each other, influencing the transformation in our society, especially with the increased use of social media.

2.1.1 What is online ethnography?

Before going into the definition of online ethnography, first there is a need to understand how traditional ethnography is presented in the literature. Ethnography is one of the theories that are based on data collection methodologies and it is focused on understanding and exploring the real world such as ideas, ways of thinking, meanings or symbols (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000), providing periods of exposure to the empirical material (Atkinson and Hammersley, 1994). As Fetterman (1989) states in his book, the definition of ethnography is “the art and science of describing a group or culture.” (p.11).

When it comes to online ethnography, Hine (2008) point of view is that it transfers the traditions as integrated tools into the online social spaces. These traditions might refer to the inductive and deductive approaches of an ethnographic study that drive the research approach. On one hand, inductive ethnography concentrate on data while deductive ethnography, covered by concepts as interpretive ethnography, critical ethnography or post-modern ethnography, focuses on the narrative representations and critical reflection of the problems (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000). However, there are studies that talk about the inadequacy of conventional ethnography when transferring it into the digital fields (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015; Marwich, 2013). Thus, there is a need for a deeper understanding of how to use online ethnography as a research tool, which will also affect the research design and methods.

Besides studying a medium and its users, online ethnography is also approaching social phenomena which are equally real as the one represented in the offline environments (Airoldi, 2018). People nowadays use online tools for everyday communication and this collected data might hide other perspectives from an ethnographic study which would add value to the whole research project.

In the beginning of online ethnography, in order to frame the context, ethnographers tend to concentrate on the place-driven metaphors around the internet. This was a way to understand the “rooms” represented in the early social chat software (Hine, 2008, p. 27). The place-driven concept still exist in nowadays internet and it is very popular when it comes to group chats on communication applications, social media, blogs, Facebook pages or Google groups (Airoldi, 2018). However, online ethnography is studying not only the place-drive metaphors, but also complex array of activities and their intersection within the networked publics (Boyd, 2011).

2.1.2 What is the time-space framework?

Online ethnography research is usually represented by ample cultural studies with long term exposure, which might produce the risk of exploring phenomena, people or ideas without limiting them in a certain framework. This possibility is due to the desire of creating comprehensive knowledge, which might also lead to time consuming projects and unfocused results. In order to avoid this risk, Cook, Laidlaw and Mair (2009) limit the ethnographer’s field as “a set of points that may be imagined as a space - as a site” (p. 60). Therefore defining the borders of the research project from the beginning represents a key aspect that has high importance within the project design.

Marcus (1995) defines the ethnographic research approach as embedded in the environmental system, but outside the single sites, in order to observe the large movement of the cultures, objects and identities. His statement points out the traditional ethnographic views and how open the researcher should be in order to understand a phenomenon from multiple perspectives, and to examine it considering complex cultural meanings in a broad time and space.

The online environment provides according to Airoldi (2018) two different ethnographic infrastructures, one based on the distinct social media contexts that have their own space, and the other one located along streams of “de-contextualized communicative contents” (p. 670) as it is the example of hashtags searched on different social media platforms. This digital field can be also seen as a parallel form of the traditional environment, which provides specific patterns of informational systems that are streaming around the participants, as a phone conversation that has defined characteristics (Meyrowitz, 1985). Comparing the pre-online perspective to the digital fieldwork, the physical aspects of the space, as the dimensions of the walls, or the position of the doors and windows, are mimic in the digital space by the platforms and applications’ infrastructures (Baym & Boyd, 2012). On a larger perspective, the online spaces have become more and more real, being depended on each medium’s specific characteristics (Floridi, 2014). Still within the comparison between physical spaces and online interactions, it is important to reflect on how their fragmented borders are affecting the research ethnographic practices, or even reshaping it (Airoldi, 2018). The relation between researcher and participants differs from physical to online interaction, which might become hard to embrace. When it comes to understanding participants feelings in a deeper sense, online communication platforms on social media might not provide the same knowledge that a physical discussion would accomplish.

However, it is important to have an open mindset and to understand how to use these particularities of social media tools, perspective that might lead to valuable knowledge creation.

2.1.3 What is the ethnographer’s role in online studies?

One of the ethnographers main role is to have an open mindset regarding the study. Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000) emphasizes the relation between theoretical framework and data, where theory is offering a reference in directing the organization of the work, instead of interfering with the observations and analysis.

The ethnographer should also be able to understand the contemporary network society (Castells, 1996) communities by spending a notable amount of time in the online platforms used by the participants (Caliandro, 2018). Considering the current study, these network societies are represented by the teenagers interaction on social media which translates as the researcher being actively engaged in their social practices in order to understand this shared culture, developing comprehensive perspectives and knowledge.

The concept of “follow the things” introduced by Marcus (1995) might represent a threat for one designing a study within the broad and ubiquitous online environments such as social media, due to the risk of getting lost in defining the limitations of the study, since the social actors spend most of their everyday lives (Beneito-Montagut 2011; Hine 2007). Therefore, the need of a clear scope and position appears. Caliandro (2014) points out an important aspect when using the ethnographic approach in online media, characterized by the decision of knowing which perspective to choose from collected data, as well as when to stop gathering it: “researchers must be aware of the infrastructural properties characterizing digital sites [...] Ethnographic fieldwork must be designed accordingly, comprehending and exploiting the logics and peculiarities of digital media.” (p. 756).

In order to develop a “thick” analysis of the social phenomenon - concept established by Geertz (Airoldi, 2018) - the research needs to follow also the participants outside the virtual context and to consider online medium as part of our social environments (Miller and Slater, 2001). Seeing the participants embedded in other social spaces (real life situations), gives another perspective when analysing the empirical data and constructing the research findings.

Thus, the researcher has to embrace the platform as a guiding tool, in the current study, taking advantage of the media and use it along with all its properties, as an aid for engaging participants in collaboration. Ethnography is an approach based on observing the people and how they act in their time and spaces, which contribute in forming the research role as one that is not struggling with designing a very detailed method, but rather exploring the way people use their own life mechanisms, in order to follow effectively the dynamics of empirical data. investigate the (Calianro, 2017).

2.1.4 How can the online ethnographic methods be used?

Traditional ethnographic approaches are transferred to the virtual medium, along with their methodological concepts. Burrell (2009) defines the term “field site” as being the place where the social processes within the study develope, which determines a transposition of offline methods to today’s social media environments (Airoldi, 2018). These methods need an adaptation to the new tools and platforms in order to succeed in gaining fruitful results.

Airoldi (2018) presents two research approaches when conducting ethnographic studies in an online medium. The first one is referring to the macro level of social representations around the meta-fieldwork analysis, and the second one addresses the micro level, which is represented by a context-sensitive perspective. These two different ways of pursuing ethnographic research on social media are relevant in understanding the context and the people, especially because they aid the observational process on how the general level of meta-fieldwork is occuring (on open environments such as newsfeeds, tweets, open posts), as well as focusing on specific micro level found in the contextual site environments (private groups, private messages).

Frequently, conducting research on social media from an ethnographic perspective is undertaken by observing online publics, largely groups of people that do not know each other and connected through the platform's built environment (Baym & Boyd, 2012). Still, there is also the possibility of studying social media in relation to a relatively small group of people, who are in connection to each other and act towards common goals based on their personal beliefs, as represented in the OEPD study.

When it comes to interpreting the data, there are multiple ways of viewing the one collected from online environments, and due to the fact that we are so used nowadays to see this type of social communication, it might lead the researcher towards recognizing it as being simple and easy to be understood, while it can actually provide more meaning is he/she started seeing its “entry points into larger and more complex worlds” (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015, p. 7).

As theory shows, online ethnography is a flexible approach that gives the opportunity to sustain an open view and to adapt its features according to the “mutations of online environments” (Caliandro, 2018, p. 552) and the project needs, during the development process. By all means, online ethnography represents a suitable approach for the OEPD study, since it has a complex system of actors, actions and topics.

2.2 PARTICIPATORY DESIGN

2.2.1 What is participatory design?

Participatory design is a concept understood as the collaborative design process in creating new technologies, in which the people that will be influenced by these new designs are directly involved (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012).

Nigel Cross mentions about this concept in 1971 at the Design Participation conference on user participation in design. This “design participation” approach, even though it was new at that time, Cross (1971) considered it “an inadequate cliche” (p. 11-14) due to the fact that everyone was using it, as Bahman (1971) describes it being: “one of those ideas that everybody has heard of, everybody can discuss, everybody knows what it means” (p. 15-18). However, participatory design became an important approach in the research field and the term started even to be used as a collaborative decision-making factor (Jones, 1971). By that, the diversity in the studies and the implications of the “users” made it a difficult approach.

Modern studies are stating that nowadays, the participation in research is a ubiquitous fact and that participatory design provides the mechanism for making it happen (Smith, Bossen, and Kanstrup, 2017), but its meaning of “participation” has become altered as it gained more approval on the public perception. (Smith and Iversen, 2018). Because of its various applications in multiple fields such as IT, healthcare, sustainability, and also the socio-political differences between the people engaged in this type of research, this concept became so broad that its social design values for a common good and for a better society, are not completely accepted within society (Luck, 2018). However, from a research perspective, participatory design has the capability to accommodate this diversity (ibid.). Still, this design approach might not be accepted by everyone, since it gives larger opportunities to address social, political and more over ethical questions in designing the new technologies, aspects that are not always comfortable to be managed (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012).

2.2.2 What is the participatory design researcher’s role?

In participatory design, the researcher’s role is to construct the proper infrastructures for the participants in order to create heterogeneous spaces where everybody can become collaborators, well as to keep an open mindset and leave behind the misconceptions about how social-materially life is organized, in order to facilitate innovative transformations (Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren, 2010). The researcher needs to recognize how personal understanding regarding the design, design process, methods, activities and tools are enabling the transformations within the process of shaping and re-shaping our socio-technological intrastructures project context (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012).

Since participatory design has a flexible approach and very much depends on the collaborators and the other stakeholders, another aspect that the researched needs to be aware of is to accept that the planned transformations might or might not happen, and at the same time other changes can occur, developing new possibilities for applying the technology in this social context (Orlikowski and Hofman, 1997).

Embracing the power positioned in people’s hand and accepting that all people are creative and can take part in co-design, become a collective thinking and acting that will provide valuable support in solving today’s challenges, only if the ones that are guiding this process give the relevant tools for enabling creativity and communication (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012). As an analogy for this action, the researcher is equally responsible for the technology design project as it is an architect in construction (Bødker et al., 2011), who has the knowledge to understand how space, time, building materials and human resources are affecting the end product as well as its residents.

The participatory design process is a social activity made in collaboration with others, rather than the individuals, that is defining the domain of work and how to succeed in accomplishing it (Schmidt et.al, 2007). Thus the insights need to be understood as part of the social structures, as results from producing and reproducing social process, and at the same time as products created for these people (Ehn, 1993). However, in order to be actively involved within the design process, each individual needs to perceive value in the way they are working for themselves (according to their interests), with themselves (assessing the changes that might happen during the process), and for the project (contributing with personal insights to reach the project goal) (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012).

2.2.3 What are the participatory design methods?

An important aspect to consider when designing the participatory design method is to expect how the participants are acting in the designed activities might be completely different of what is presented by others or visible in diagrams and other materials, as the way the participants are acting or should ideally do (Schmidt et.al, 2007). Still, in order to accomplish authentic results, the participation requires a position which fully embraces the user’s interests as key factors in the design process, which included also posing questions regarding the participation meaning, the decisional power, the support facilitation through design process as such, or the construction of concrete methods and tools (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012). These questions are part of the core principles for participation, as well as Kensing and Blomberg statement: “The epistemological stand of participatory design is that these types of knowledge are developed most effectively through active cooperation between workers [end-users] (and increasingly other organizational members) and designers within specific design projects” (p. 172).

The cooperation is completed by the mutual learning and learning by doing approaches. The first one supports a sustainable technological solution based on practice logic (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012), while the second one facilitates the main participatory design strategy,

prototyping (Bannon and Ehn, 2012). Using these approaches improves the participators’ practical skills in communicating and sharing their experiences with the researchers, designers and other stakeholders (Robertson and Simonsen, 2012).

There are also other characteristics that can be understood as participatory design core concepts. According to Luck (2018), there are six key concepts guiding this field: (1) equalising power relations: giving voice to the one invisible or weaker; (2) situation-based actions: working together with people in their life contexts; (3) mutual learning: considering the different views of people which might foster new understandings; (4) tools and techniques: using them properly based on specific situations to help people expressing their visions and needs; (5) alternative visions about technology: fostering expression of ideas in different contexts and; (6) democratic practices: applying the role models for those who represent others. These characteristics complement the strategy proposed by Smith and Iversen (2018) who view participatory design from three stages: scoping, from user involvement to protagonist communities; developing, from technological artefacts to digital practices and conceptions of technology and; scaling, from tangible outcomes to sustainable social change.

All together, these participatory design concepts along with online ethnographic characteristics represent the ground for this study in creating suitable conditions for the teenagers to co-design and be engaged in different activities, developing meaningful understandings for both themselves and within the CO2 Theatre project and OEPD study. They provide guidance regarding how to

actively engage the participants in collaboration following an ethical approach, how to frame the study and position myself within a complex context with multiple actors and how to collect and analysis the data, reflecting on the important elements in relation to the aim of the study.

3

|

METHODS

3.1 RESEARCH PROCESS

In order to understand the research process, and support it with relevant methodology guidance, two main process models are considered: (1) ethnography research process, which focuses on in-depth understanding of culture from a holistic perspective, finalizing with in-depth description of a group’s life (Passos et.al., 2012, p. 11) and (2) participatory action research, which is based on several iterations of observations, reflections, planning and acting (Sendall et.al., 2016, p. 4), process that goes along with my empirical data collection. The process has a flexible approach that unlocks a mechanism of learning and unlearning, where practitioners are in direct contact with the context (Yayici, 2016).

However, there is a need to mention that even though the OEPD study is conducted using the participatory design approach as guidance, for the design process model it used as inspiration the participatory action research model instead, since the participatory design models usually are conducted towards creating a final product or service, while the participatory action research allows more space for iterations and reflections. Thus, the following model presented in figure 4 is created, implementing three main stages: developing inquiry (conceptual phase), exploring (empirical phase) and synthesizing (analytic phase). Throughout this chapter, the model is explained based on each stage, which also consists of methods, tools and activities that have been conducted in order to answer the research questions.

Figure 4: Research process.

3.2 DEVELOPING INQUIRY

Developing inquiry coincides also with the beginning of the OEPD study. During this stage the conceptual phase is constructed, understanding both the practice and the theory relevant to this study.

From the practice perspective, “everyday research usually begins not with dreaming up a topic about but with a practical problem that, if you ignore it, means trouble.” (Booth et. al., 2009, p. 52). Thus, practice represents the starting point of this study, since it is taking place within an already established project. The first steps coincide with being in contact with the CO2 Theatre project team, engaging in their discussions regarding the project planning and understanding how the physical workshops with the teenagers are planned to be conducted. Within the conceptual phase, there are two possible solutions on how my study would aid the project development: the first one by being focused on the space (since there is a lack of human resources responsible for this part), and the second one by becoming the link between the project target group (the teenagrs) and the rest of the project team (again, this part is not covered yet in the project planning). Both solutions are taken in consideration until the pre theoretical study shows a more narrowed information.

The process of overlapping practice needs with theoretical perspectives on the research problem is difficult due to the wide array of possibilities. As Booth et.al. (2009) state in their book, “the condition of a conceptual problem, however, is always some version of not knowing or not understanding something.” (p.56). Thus, the beginning doubts provide with actual support for further searches, which are conducted into the field of participatory design, since the main approach of the CO2 Theatre project is on this area of expertise. Further on, online ethnographic

research is added in order to get valuable knowledge in exploring the field, and how to follow the actors.

The OEPD study planning is developed in relation to the academic course requirements, as well as with the first CO2 Theatre workshop. On this stage, the decision is made: the thesis study is focusing on the online communication with the teenagers, while the space remains a responsibility for the whole team in order to arrange it before each workshop. The activities planned for this stage are coming next.

3.2.1 Methods for conceptual phase

Physical meetingsThe purpose of this activity is to facilitate the first interaction with the teenagers that applied for the CO2 Theatre project by sending an online form. Studies suggest that the project success is in strong connection with the first physical contact between all the project partners (Kelley and Kelley, 2013). People need to feel safe in the new environment and to trust their collaborators.

Two warming-up meetings are conducted based on the need of connecting with the majority of the participants. 21 teenagers applied for the CO2 Theatre project, 9 came to the first meeting, and 3 attended the second meeting. In order to invite them to these meetings, I have sent out emails that consisted of a welcome message and short information about the agenda that will be discussed during the meeting. In both moments the facilitators and project informants were me and the manager of the museum. As part of the CO2 Theatre project, after this meeting my responsibility was to inform all the researchers about the current status of the teenagers.

Pre-study online survey

In order to understand the practical foundation for the OEPD study, a pre-study online survey was conducted, with the purpose of evaluating the teenagers’ current situation of using online platforms as communication tools.

The survey consisted of ten questions (see appendix C), five regarding general information about the participants and five that evaluated their preferences and actions on social media, and it has been sent out to 15 teenagers from those who have applied for CO2 Theatre project. The recipients selection was made based either on their presence to the warming-up meetings or their answers to my previous emails. The survey was sent via email using the website www.surveymonkey.com.

Popular media scan

The popular media scan method is used in order to identify broad topics within the OEPD field of study. It represents the background of the study in understanding the teenagers’ activisms phenomenon regarding climate action, as well as identifying the theoretical framework of this study, as presented in chapter two. As Airoldi (2018) mentioned in his paper, this search is an useful preliminary exploration providing guidance for further steps, while creating valuable opportunity in discovering the social landscape of this study, as it has been “empirically argued” by other researchers (Marcus, 1995, p. 109).

The keywords used for conducting the searches on online platforms such as Scopus database, Google, Google Scholar, Facebook and Instagram are: online ethnography, participatory design, teenagers climate action, teenagers school strike, social media methods.

Climate action Snapchat exhibition

The climate action Snapchat exhibition is an activity designed as preparations for the first CO2

Theatre project workshop, in which all participants (15 teenagers and 12 project stakeholders) are asked to send beforehand one image of themselves (selfie) with a short text added on, that describes actions they are already taking in order to develop a more sustainable lifestyle. This request is sent via email, providing information about where these images can be sent (both via email or using the Snapchat application), along with my personal example on how the task can

be completed. The images are printed out and publicly exhibited in the space reserved for the CO2 Theatre project workshops, within VLM Västerås.

3.3 EXPLORING

The exploring stage is the empirical phase of data collection and it represents the key moment of the study. This phase is developed during two months of research, applying four main approaches (act, observe, reflect and plan) within continuous circles. From a methodological perspective, these approaches are adapted to the digital domain, “therefore somewhat visualizing them [...], skillfully mixing digital techniques with analogical techniques (e.g. participant observation online and offline).” (Caliandro, 2018, p. 555).

The acting moments relay on the experimental side. Within a specific group setting, as a researcher I pose multiple questions or tasks that the teenagers answer in relation to their personal beliefs and life settings. For instance, online communication media is used, such as Snapchat, Facebook Messenger and Instagram.

The next step is to observe how the teenagers respond to the sent requests, as well as how are they establishing their group communication with each other. As Merriam and Tisdell (2016) mention in their book, observations are important in ethnographic studies, especially because they “take place in the setting where the phenomenon of interest naturally occurs”, in this case being used the tools that are already used by the teenagers as instruments for connecting to each other.

The observation moments are followed by reflection time, when questions as “Is it the right process to perceive?”, “Is there any other way of doing the actions?” or “How would the teenagers feel if I would try something else?” are taken into account. The reflection moments are not only made by me as a researcher, but also discussed together with the participants in different online formats.

Making new plans is the natural step to continue the process, and how the teenarges are influencing the project. Frequently, the planning part is done in collaboration with both the teens and the other stakeholders from the CO2 Theatre who also have certain needs regarding the project. More than that, during the exploration stage the data is collected by recording the online conversations in photo and video format, storing the files safe on a personal hard drive, with no sharing possibilities.

3.3.1 Methods for empirical phase

Data collection

Conducting the OEPD study within a relatively stable digital environment “where the traces of social interactions are limited in number, [...] ethnographers can produce field notes using

screenshots (e.g. Stirling, 2017) or manual copy-and-paste techniques (see Caliandro, 2014)” (Airoldi, 2018, p. 666).

As data collection method, screenshots from the group conversations are applied. Due to the instant notifications that all the group members received while I am using the screenshot feature, I use as an alternative method to capture my smartphone’s screen to take photos with an external device. The process of photographing is also replaced with video recordings of the screen after several failures in capturing the notifications. Several discussions about the process of data recording are conducted in the findings chapter.

The data is stored in tabular files organized by the dates of the posts. Even thought this collection tool might seem very distant from the usual ethnographic experience (Caliandro, 2017), the data collected provides fruitful interpretations of the teenagers’ social interactions. Facebook private group

Based on the methods conducted on the conceptual phase, the empirical phase starts by creating the private group on Facebook, one social media platform planned for the OEPD study. As a metaphor for choosing to make a study together with the teenagers by accessing their social practices on private digital sites, Airoldi (2018) mentions: “In terms of access to the site, ethnographies of private dinners are obviously different from the unobtrusive observations of town-squares interactions. Similarly, in order to access interpersonal communications within Facebook chats or closed groups, it is not enough to digit a keyword in a search bar. It is necessary to contact the informants first, asking to be invited to join otherwise inaccessible digital settings.” (p. 669). However, this Facebook private group is not used as communication and collaboration platform, due to the findings gathered in the first CO2 Theatre project workshop.

Snapchat private group

The Snapchat group is one of the main OEPD study communication channels, along with Facebook Messenger private group. This tool is co-created with the teenagers during the first CO2 Theatre project workshop, the participants connecting with each other by creating this private group named “The students”, on which I received the access. The group consists of 14 members, including me. Once more, the number of participants is based on their active participation in the CO2 Theatre project. The teenagers that withdrew from the project were not included in this group.

#30daysclimatechangechallenge

Willing to experiment the co-creative approach on social media, the #30days climatechangechallenge activity is created. Using the Snapchat group as the communication platform, the Instagram challenge represents a triggering moment for the participants to share