http://www.diva-portal.org

Postprint

This is the accepted version of a paper published in Scandinavian Journal of Management. This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination.

Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Crevani, L. (2018)

Privilege in place: How organisational practices contribute to meshing privilege in place Scandinavian Journal of Management

Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

Introduction

The concept of privilege can be used to express ‘the ways social inequality actualises in everyday lived experiences, systems and institutions’ (Banks, Pliner & Hopkins, 2013, p. 102). Analysing privilege thus enables the exploration of unrecognised advantage that positions certain people in a favoured state and systematically confers power on certain groups of people in specific contexts (McIntosh, 1989). In other words, privilege is situated and therefore related to specific places. Such a relationship between privilege and place is the focus of this paper. More specifically,

building on a processual understanding of space and place (Massey, 2005; Beyes & Steyaert, 2012), and following the construction and enactment of a ‘temporary place’ (an exhibition), in this article I propose that places are not simple ‘containers’ for the production of privilege, but rather that the production of privilege is to some extent meshed in the construction of place itself.

The rationale for studying privilege is that the study of discrimination and oppression, on which much academic work on inequality and social differences in organisation theory has focused, leaves out the ‘up-side of discrimination’: privilege (McIntosh, 2012, p. 197; Choo & Ferree, 2010). Privilege can be understood as accumulating across categories of social difference and in time, as McIntosh’s seminal paper (1989) points out. For instance, in many contexts, male privilege and white privilege are connected and reproduced (ibid). Building on such insight and on research from among other sources gender studies, ethnicity studies and studies of heteronormativity, researchers have developed different avenues of investigation, including how to make privilege visible, what the consequences of privilege are and how to work with awareness-raising initiatives (Case,Iuzzini & Hopkins, 2012; Ferber, Jimenez, O’Reilly & Samuels, 2008; Cole, Avery, Dodson & Goodman, 2012).

In organisation studies, such an approach has only partially been mobilised. While scholars mention privilege and at times produce empirical material about this phenomenon, they nevertheless tend to focus on the production and reproduction of oppression (Choo & Ferree, 2010). In this paper, I therefore want to contribute to organisation studies by foregrounding processes of privilege accumulation related to organising practices. Given that privilege is situated, studying privilege requires an understanding of the place in which privilege accumulation takes form. To develop such an understanding, I lean on the increasingly rich stream of studies on the places and spaces of organisations and organising processes (Dale and Burrell, 2008; Beyes and Steyaert, 2012; De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013; Zhang and Spicer, 2014; Ropo et al., 2015; Sergot and Saives, 2016). In particular, I build on the idea of space and place being more than ‘containers’ – space and place are performative and continuously reproduced as they both affect and are

affected by organising processes (Beyes and Steyaert, 2012; De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013). Spacing is about ordering, about emerging relational configurations (Beyes and Steyaert, 2012) and thus

spacing processes enact power (Dale and Burrell, 2008; Vásquez and Cooren, 2013). Place can be argued to be not only about ordering, but also about convergence of meaning and homogenisation of practice – place is often treated as meaningful location, a coherent bounded space that can be a source of identity constructions and can inform social processes (Cresswell, 2004; Courpasson, Dany and Delbridge, 2017; for criticism, Massey, 2005). A processual understanding

problematising such convergence (Massey, 2005) still needs to be further explored in organisation studies (Sergot & Saives, 2016).

The purpose of this paper is therefore to add to our understanding of processes of privilege accumulation in place by exploring the relation between privilege and place when both privilege and place are considered processes rather than entities. If place is not a neutral container and if place is not only an entity that is given meaning through social practice, but a process involving the ongoing configuring of people, artefacts and the physical environment (Massey, 2005), how does such configuring relate to privilege accumulation?

To explore such a question, I focus on a place that can be defined as ‘temporary’, that is Nordic Outdoor, an exhibition. Although all places are temporary when a processual understanding is mobilised, this place does exist for only a couple of days: it is quickly constructed and then deconstructed. It thus provides the opportunity to study whether privilege accumulates (or is absent) as the organisations participating to the exhibition and the organisers of the exhibition bring and invite people and artefacts to the physical environment of empty fair trade halls, and as people and artefacts engage in certain practices made possible by the organisations involved. In my analysis, I build on human geographer Doreen Massey’s work (1994; 2005; 2011) and her notion of place.

Since the purpose of the article is to further our understanding of processes of privilege

accumulation in place, I first introduce the literature on privilege accumulation and then I describe the conceptualisation of place mobilised in this article, building on the emergent literature on space and place in organisation studies. After a section on methodological considerations, I present the studied event, Nordic Outdoor, and analyse it, elaborating on how privilege accumulates as place is produced and proposing the concept of ‘privilege meshed in place’. Finally, I discuss the value of my analysis in adding to organisation studies with respect to questions of inequality and social difference (Choo & Ferree, 2010) and of place, power and organising (Sergot & Saives, 2016). I conclude that the contribution of this article is thus two-fold: it contributes to deepening our knowledge of privilege accumulation and our understanding of the production of place as a result of organisational practices.

Privilege and organisation studies

Peggy McIntosh’s seminal papers (1988, 1989) affected the study of inequality, turning the attention towards advantage and how it is manifested, produced and challenged. The title of the 1989 paper is telling: ‘White privilege: unpacking the invisible knapsack’. Starting from her own experience, she problematises how a system of privilege offers some people a favoured status in society. In her own words:

I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was "meant" to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, assurances, tools, maps, guides, codebooks, passports, visas, clothes, compass, emergency gear, and blank checks (McIntosh , 1989, p. 2)

Studying privilege thus means focusing on systems that create and maintain benefits in the form of access to rewards and resources for specific groups in relation to other groups (Case et al., 2012). Not only that, as these unearned benefits are conferred on entire social groups, for instance white people, privilege is not reserved for only a limited elite in society, as popular discourse may suggest, but rather is a widespread phenomenon (ibid). It is a phenomenon that is often invisible, ironically precisely because norms are pervasive (Kendall, 2006), which means that those benefitting from them do not recognise their privileged position (Kimmel & Ferber, 2017).

Privilege is often legitimised by referring to the naturalness of the state of affairs (Cole et al., 2012) and the norms reproduced by the privileged become generalised expectations for everyone, which means that the privileged ones do not need to be knowledgeable about their privilege, nor about possible oppression caused by it (Case et al., 2012). Such conclusions are also supported by research in gender studies (Martin, 2003), critical race theory (Collins, 2015; Twine & Gallagher, 2008) and ableism (Campbell, 2009), to mention some central contributions. Privilege thus means having a position that is constructed as natural and that allows access to rewards and resources. Mobilising ‘nature’ has powerful effects since ‘nature’ suggests that something has an essential character, immutable and fixed, but also that there is a ‘plan’ or ‘force’ that makes things the way they are (‘Mother Nature’), and that such things are genuine and given, not constructed by ‘culture’ (Cole et al., 2012). Hence, naturalising current situations in which people have different access to resources and benefits contributes to maintaining privilege. Moreover, the essentialisation of cultural differences and the individualisation of achievement also contribute to making privilege persist and easily render it invisible (Ferber, 2012). The invisibility of privilege is problematic as it is an obstacle to change processes aiming at greater equality and inclusion (Kimmel & Ferber, 2017). If inequality is only addressed from the oppressed point of view, those in a position of

privilege may argue they have nothing to do with it and can do nothing about it (ibid). Hence, while making privilege visible may be complicated, it also results in making more social groups accountable for current inequalities and for taking action in order to reduce them (ibid).

An important aspect of privilege is that it is relational, embodied and accumulates across categories (Ferber, 2012; Banks et al., 2013; see also intersectionality scholars such as Collins, 2015; Holvino, 2010). In other words, race, gender and other categories of inequality build a matrix of privilege and oppression (Coston & Kimmel, 2012, Banks et al., 2013; Collins, 2000; Ferber et al., 2008). Privilege is thus created and sustained in practice; it is no essential characteristic of a social group, and the practices in which this happens are also related to organisational practices (Gherardi, 1995). Although several leading scholars in the field of intersectionality and organisational practices mention privilege and its invisibility (for instance Acker, 2006; Holvino, 2010), research in

organisation studies interested in questions of inequality has mainly paid attention to the

construction and reiteration of oppression (Rodriguez, Holvino, Fletcher, & Nkomo, 2016). There is still a need to turn to privilege and examine how organisational practices contribute to the emergence and maintenance of privilege (Atewologun, Sealy & Vinnicombe, 2016) – a need to look at how certain groups become defined as normative standards (cf. Choo & Ferree, 2010). Such an approach would be beneficial for bringing the advantage of dominant groups into sharp focus, thus potentially providing a means to contribute to dismantling the invisibility of privilege (Case et al., 2012). This knowledge is also important for grounding change initiatives aimed at reducing inequality and increasing inclusion (Acker, 2006; Kendall, 2006).

Studying privilege accumulation in place

Exploring the accumulation of privilege means making visible the unrecognised advantage that positions certain people in a favoured state and confers power on them in specific contexts (McIntosh, 1989). In order to understand privilege, it may then be important to understand the place in which privilege accumulates and how it is related to such an accumulation. To this end, I build on the increasingly rich literature on the spatial dimension of organising in organisation studies, contributions that have explored processes in which space affects organising and/or in which space is produced (cf. Kornberger and Clegg, 2004; Taylor & Spicer, 2007; Beyes & Steyaert, 2012), although seldom focused explicitly on place (Sergot & Saives, 2016). Admittedly, the distinction between space and place is a debated one (compare, for instance, Tuan, 1977 and Massey, 2005). For the purpose of this study, I build on Massey’s work that I describe below and propose that what the concept of place has to offer is the possibility to foreground coherence and convergence in the form of ‘uniqueness’ and ‘authenticity’ as constructions, always possible to contest, and requiring work to be achieved in the coming together of people, artefacts and physical environments. What most of organisation scholars have done, I suggest, is to foreground how the

relations between people, artefacts, and the physical environment are shaped, enacted,

re-constructed, and contested (cf. De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013) mostly in terms of different kinds of separation and distinction in space (see for instance Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015). In relation to the focus of this article, one could say that while mobilising space allows us to develop our

understanding of how identities, power, and control are constructed and re-constructed, the concept of place enables us to take issue with the very core of notions of identity (individual or organisational) and power by problematising the idea of ‘uniqueness’, ‘genuinity’, ‘meaningfulness’ and ‘authenticity’.

To clarify such an argument, I start by introducing the conceptualisations I borrow from human geography. Human geographer Doreen Massey has dedicated her professional life to developing understandings of space and place as open-ended, constructed, contested (Massey,1994; 2005). Together with other geographers such as Nigel Thrift and Gillian Rose, to mention two, Massey has namely been deeply engaged in re-articulating space and place, refusing to treat them as neutral categories given a priori, proposing instead to treat them as constituting and constituted by ‘the social’ as well as ‘the natural’ (Kitchin & Hubbard, 2011). In such a view, space-time is no container: space is constructed in, and constructs, social and material relations (Massey, 2005).

Several scholars in organisation studies have been inspired by similar processual views of space, and many of them have heavily drawn on Lefebvre, and in particular his book ‘The production of space’ (1991), in order to study organisational spaces (cf Taylor & Spicer, 2007). Space, or better, spacing, is understood as ‘processual and performative, open-ended and multiple, practiced and of the everyday’, thus making us aware of provisional spatio-temporal configurations always in process (Beyes & Steyaert, 2012, p. 47). Going beyond the space as container metaphor, ‘space is more than an abstract neutral framework filled with objects [...]. We constitute space through the countless practices of everyday life as much as we are constituted through them’ (Clegg and Kornberger, 2006, p. 144).

Furthermore, the political nature of space and the enactment of power through space has been a central point of interest (Clegg and Kornberger, 2006; Dale and Burrell, 2008; Zhang and Spicer, 2014; Ropo et al., 2015) with regard to both how spatial processes reproduce power asymmetries (Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015) and when they possibly reconfigure them (Beyes, 2010;

Panayiotou, 2014; Wasserman and Frenkel, 2011). Drawing on Lefebvre has also made it possible to foreground possible tensions and contradictions between how space is designed and how it is lived and experienced (Dale, 2005; Dober and Strannegård, 2004; Wasserman and Frenkel, 2011), and thus to show how inhabiting organizational space can be understood as a negotiated practice including identity work (Tyler and Cohen, 2010). In relation to the aim of this article, particularly

interesting are specific studies problematising gender (Tyler and Cohen, 2010; Panayiotou, 2014) and gender and class (Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015). Gender identities can be understood as performed and materialised in and through workspaces, in relation to norms dominant in the context in which the organisation is situated (Tyler and Cohen, 2010). For instance,

‘simultaneously enacting and signifying […] “normal” women’ (ibid, p 191) can be achieved through resignation to accepting spatial constraint and spatial invasion. Panayiotou, on the other hand, foregrounds how spaces that seem to marginalise women can be hybridised by spatial practices that make the margin into a ‘space of radical openness’ (2014, p 127). In Wasserman and Frenkel’s (2015) study, women are also to be found in different space than men and societal norms play a role, but there is a difference between women belonging to different classes – women, in other words, are not a homogeneous group with regard to spatial work. Spatial work is performed as spaces are inhabited and personalised, as women move in the space in specific ways and are dressed in certain fashions, but also as efforts are made to materialise organisational identity in the buildings. Spatial work, performed by female workers on the one hand, and architects and

managers on the other hand, thus contributes to both reproducing and challenging gender and class distinctions and hierarchies (Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015). Such work has a discursive, a

physical and an emotional dimension – such work is therefore embodied and material (ibid). Attention to aesthetics and materiality is therefore also central to the study of space and organising, although the degree of significance and of agency attributed to materiality differs (De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013).

While conceptualisations of space have informed organisation studies, place as a concept is mobilised more seldom (Sergot & Saives, 2016). Interesting exceptions are Courpasson et al. (2017) who have explored the role of place for resistance in organisations and Shortt (2015) who has focused on transitory dwelling places. In Courpasson et al. (2017), places for resistance are not ‘natural settings’, but rather emerge through the repeated practices performed by the resisting group in that setting, at the same time as they impact the kind of resistance that emerges. The meaningfulness of the places to those making resistance is crucial and emerge as people do things in that place. In Shortt (2015), places are also constructed, but stable, and thus a source of meaning. These studies demonstrate the importance of studying place as a phenomenon related to organizing process and show how the convergence of meaning is central to how place intertwines with organizing. The focus is on people in place, though. In this article I want to add to this stream of literature by answering the call for processual and sociomaterial approaches to place (De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013; Orlikowski and Scott, 2008), which means that the convergence of meaning related to a place is not given, but rather is accomplished in evolving configurations of people, artefacts and physical environments – something to explore empirically.

To this end, I turn to Massey’s understanding of place. Until recently, Massey’s work has seldom been mobilised in organisation theory. Recent articles show, however, how her relational thinking and attention to power enactments can be fruitfully mobilised not only for exploring spacing processes (Vásquez & Cooren, 2013) but also for analysing place and how place comes into being in relation to organisational practices (Sergot & Saives, 2016). While place is often referred to in entitative terms such as static, genuine, authentic, bounded, with a definite identity on which people’s identity is dependent, Massey foregrounds the multiplicity of trajectories that make up a place, resulting in continuous negotiation about how to be together. Hence, place may be

understood, as commonly held, as a meaningful location (Cresswell, 2015, p. 12), but such meaningfulness is co-constructed and contested. Place is a spatio-temporal event, not a point on a map (Massey, 2005, p. 130). This means that space is not already divided up into places that are already separated; rather, the boundedness of place is constructed and its cultural specificity emerges not only as what is ‘internal’ becomes articulated, but also in relation to what is beyond.

The main characteristic of place is its ‘throwntogetherness’ and how it is handled (ibid, p.151) – places are thus collections, or bundles, of trajectories. Travelling between places is moving between collections of trajectories and ‘reinserting’ in those one relates to (ibid, p. 130). A trajectory, or a story-so-far, can be understood as the movement and change of ‘phenomena’, both humans and artefacts, but also geological formations and the physical environment (ibid, p. 12). Trajectories co-evolve in relation to each other. Hence, places are constructed and re-constructed as trajectories come, leave, and change. There is no pre-existing coherent collective identity linked to a

geographical location, but rather continuous negotiation and co-existing multiplicity. Places, or collection of heterogeneous trajectories, are also articulated within wider power-geometries that affect/are affected by them (Massey, 2011).

Hence, in order to study how places take shape and their meaning is negotiated, the researcher can look at which trajectories become related and how, as well as what such emerging relational configurations do. Given this anti-essentialist conceptualisation of place, place is political. The production of place is related to ordering attempts, regulation of juxtapositions, codification of space, negotiation of the terms for connecting, and who gets the right to be present (Massey, 2005). Places are produced through practices that form relationships and it is by focusing on practices and relationships that political action becomes possible. Furthermore, Massey also used the term ‘power-geometry’ to express the notion that groups, or individuals, are differently positioned within the constellation of trajectories and how trajectories are interrelated (Massey, 1993, p. 61).

In conclusion, building on Massey I define place as an event consisting of a bundle of trajectories (related to a location) organized in specific configurations, whose throwntogetherness needs

negotiation in order for coherence and uniqueness to be produced. Hence, compared to organization studies focusing on space, my attention is directed towards how the bundle of trajectories gains meaning and coherence. After presenting some methodological considerations in the next section, I will therefore introduce Nordic Outdoor, an event organised by Swedish outdoors companies and mobilise Massey’s conceptualisation of place to explore how privilege is constructed on these occasions by asking the following questions:

- Which trajectories are brought to Nordic Outdoor? - Which trajectories come to Nordic Outdoor? - How are these trajectories ordered?

Methodological considerations

This article is based on the work done in a project on the outdoors industry in Sweden that was chosen as empirical focus given my theoretical interest in studying privilege accumulation. The outdoors industry is very successful in Sweden and outdoors is strongly related to Swedishness, something that attracted my interest and inspired me to start a study about ethnicity and

organising. The research process has then proceeded abductively, moving between fieldwork, re-reading of empirical material, emergent analysis and deeper theoretical understanding (Dubois & Gadde, 2002), thus accumulating observations of a phenomenon and reaching ‘beyond the experience of the moment to comprehend intuitively and theoretically the patterned network of interdependent relationships that give events their meaning’ (Taylor & Van Every, 2011, p. 21). Analytically, therefore, I gradually ended up focusing on categorising the events studied in different situations, identifying which trajectories were to be found in such situations, how such trajectories were becoming related and what such emerging configurations were doing in terms of producing social difference, including how such trajectories relate local practices to practices being performed in other places (both in space and time).

Empirically, what guides my fieldwork is trying to be present during instances of ‘constitution of organization’ (Cooren, Brummans & Charrieras, 2008), inspired by a multi-sited ethnography approach (Couldry, 2003). While losing the traditional ethnographic focus on one ‘site’ may lead to reduced depth of understanding, the phenomenon I became interested in unfolds in different locations and the aim of my study is not to produce a thick description of one culture, but to gather as much context as reasonably possible (Cooren et al., 2008) in order to discuss the performativity of different configurations of trajectories. Working with this kind of approach may be a necessity to be able to follow complex phenomena involving a large number of people and locations within the limited resources of a research project: what can be defined as a ’passing organizational

ethnography’ (ibid). But it is also a question of analytical focus, given my interest in analysing the meeting of trajectories in communicational events, without aiming at reproducing a

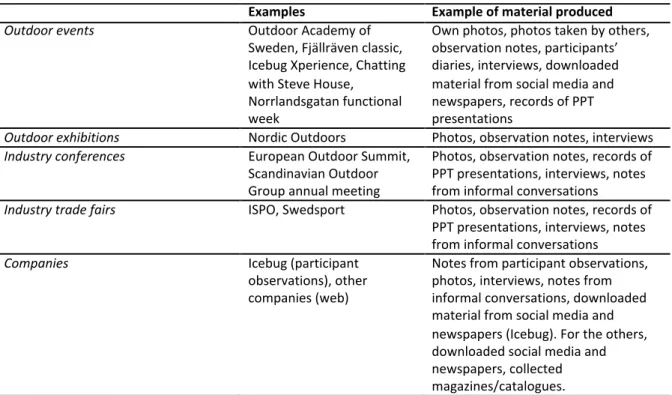

phenomenological account of people’s lived experience. The approach followed could therefore be characterised as a ‘passing multi-sited ethnography’ and includes the fieldwork and material produced according to table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the empirical material produced in the study

To follow the production of places initiated by company representatives, I used a combination of techniques, inspired by Latourian hybrid fieldwork (Austrin & Farnsworth, 2005). Hence, besides observations, interviews and participation in events, I also collected printed material and

downloaded websites. In particular, in this article I present one event which is representative of others: Nordic Outdoors. Table 2 summarises the material produced.

Examples Example of material produced Outdoor events Outdoor Academy of Sweden, Fjällräven classic, Icebug Xperience, Chatting with Steve House, Norrlandsgatan functional week Own photos, photos taken by others, observation notes, participants’ diaries, interviews, downloaded material from social media and newspapers, records of PPT presentations

Outdoor exhibitions Nordic Outdoors Photos, observation notes, interviews Industry conferences European Outdoor Summit, Scandinavian Outdoor Group annual meeting Photos, observation notes, records of PPT presentations, interviews, notes from informal conversations

Industry trade fairs ISPO, Swedsport Photos, observation notes, records of PPT presentations, interviews, notes from informal conversations Companies Icebug (participant observations), other companies (web) Notes from participant observations, photos, interviews, notes from informal conversations, downloaded material from social media and newspapers (Icebug). For the others, downloaded social media and newspapers, collected magazines/catalogues.

Table 2. Summary of the empirical material presented in this article.

Finally, in this article I use photographs that provide a documentation of interesting situations – one can see which trajectories are being gathered and how they become related. It is also crucial for me to use photographs as they re-produce part of the materiality that was central in the situations analysed. The written text can capture some elements and frame them, but visual communication is different, given its immediacy and aesthetic impact (Bell & Davison, 2013). However, this does not mean that the empirical material becomes more objective or more directly accessible to the reader in this way (ibid); rather, photos are part of the narrative that this article articulates.

Nordic Outdoor

Nordic Outdoor 2014 is the event I focus on in this article. Nordic Outdoor is an exhibition open to consumers of outdoors products (clothes, shoes, equipment), integrated with a number of

competitions, shows and the possibility to try different outdoor practices, such as climbing, tenting, kayaking, balancing on a slackline, etc. The event is open to the public – there is an entrance fee to pay that is reasonably low and comparable to other similar events (approx. 10 euros). In 2014, even action sports (such as BMX or parkour) are present under the label ‘Nordic Outdoor’ and the event runs parallel to the tourism exhibition ‘Tur’, which meant that visitors to ‘Tur’ can also participate in ‘Nordic Outdoor’. The total number of visitors reaches 23 000 people over two days. Nordic Outdoor 2014 takes place in the halls of the Swedish exhibition and congress centre in Gothenburg in Sweden. The exhibition and congress centre is located in the heart of the city (as their website proudly claims), surrounded by large and trafficked streets and by different tram lines. It is composed of exhibition halls and three skyscrapers (Gothia Towers) including

Event Event open/closed Material produced Nordic Outdoors This event is open to

everyone. I was also invited to the Scandinavian Outdoor Group taking place in the same building the day before.

I participated in the event and to the presentation of the event to outdoors companies the day before the opening.

Notes, pictures and films documenting:

- observations of what was happening and informal talks with people during the event - the organiser’s presentation of the event to representatives of outdoors companies the day before the event

- a tour given by the organiser around the halls of the exhibitions as workers were building the stands, scenes, tracks, etc the evening before the event

- a dinner with representatives of outdoors companies the evening before the event Material published on the internet (articles, ads, etc.)

conference facilities, restaurants and a hotel.

Setting the scene

The day before Nordic Outdoor, the Scandinavian Outdoor Group (SOG) gathers in the same facilities for their annual conference. SOG is an association including all major Scandinavian, in particular Swedish, brands. Figure 1 shows one of the slides presented, with a man hiking and wading across a stream and the agenda of the assembly. At the end of the formal assembly, the founder of SOG, who is now leaving the position as leader of the association, is thanked and given one of the first posters that he produced, with the text ‘Original outdoor business (according to Scandinavians)’ and the picture of a group of aggressively shouting Vikings that have landed and are ready to fight (see figure 1). The reference to Vikings is something he often used when talking about Scandinavian Outdoor, and it is also present on the ‘certificate’ that he is given as a sign of appreciation for his work (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Images from the SOG meeting: a slide with the agenda, the SOG funder is thanked, the certificate given to him.

As the last activity for the day, the Nordic Outdoor organisers present the event and guide the company representatives, who will themselves participate in it, through the halls where people are working with constructing stands, stages and sites for activities. It is with this presentation and tour of the halls that I start the description of my participant observation. After that, a more analytical section explores the question of how trajectories are gathered and organised as this place emerges.

The day before Nordic Outdoor

Late in the afternoon, the organiser of Nordic Outdoor, present the event that will take place the day after. She is very proud of all the exciting highlights and activities they have succeeded in putting together, and actually a bit nervous about the opening ceremony. A PPT presentation she has prepared shows pictures from last year, when in the opening ceremony a man climbed one of the skyscrapers all the way from the bottom to the top to the awe of a rather large crowd that had gathered in the streets below. As figure 2 shows, other activities that took place included different sorts of climbing, running, and trying out outdoor gear.

Figure 2. PPT slide summarising Nordic Outdoor 2013 presented by the organiser of Nordic Outdoor 2014.

The organiser explains to us that the aim is to invite people to try outdoor activities such as climbing, diving, parkour, etc. It will be an intense and high-pulse event for those that want to challenge themselves. There will be 69 exhibitors and 19 different activities going on. Activities will include a, a trail-running competition, as well as the possibility to try slackline, , kayak, etc. There will be a cinema showing some of the best movies about nature, about personal portraits and more adrenaline-intense films, in collaboration with National Geographic and Sergel Media. There will also be seminars with distinguished guests like Ola Skinnarmo (a famous Swedish adventurer) and Robin Trydd (the youngest Swede to climb Mount Everest). Finally, most companies having a stand will sell their products at reduced prices. But the most exciting part is the opening ceremony that will be even more dangerous and spectacular this year: there will be people balancing on a highline between two skyscrapers. The people around me seem to be excited by the idea.

After this presentation, we are invited into the halls where people are frenetically working to make the stands, stages, and different artefacts ready. Everything seems to be still rather unfinished (see figure 3) and I wonder whether they will really make it by the next day. While the stands are mostly ‘ordinary’ fair stands, smaller and larger objects are being transported and assembled to produce rock-like climbing walls, parkour tracks, green grass on which to pitch tents, etc. The organiser explains that this year ‘Tur’ runs in the adjacent halls and this will probably result in more older people than usual participating in Nordic Outdoors, as a large proportion of the tourism exhibition visitors consists of older people, according to her. As we walk around, I talk to some of the company representatives and they explain how they all know each other and used to do things together. None of them is really into extreme adventures, but they all like to be outdoors and have to some extent been active in outdoor practices. At dinner, such a picture is confirmed. These are people that like and know their products as they use them themselves – the outdoors is an important part of their lives. Something that we end up discussing as the dessert is served is whether these companies are producing extreme images of what outdoors is about: more and more athletic bodies are presented in more and more extreme situations. Everyone knows that this is not

who the majority of the people buying outdoor products are, but somehow the industry seems to be stuck in this superhuman imaginary.

Figure 3. The preparation of the exhibition the day before Nordic Outdoor.

At Nordic Outdoor

The next day, as I want to experience the exhibition as a ‘regular’ visitor, I go out from the hotel and approach the congress centre from a distance. It is kind of strange to walk, feeling the pulse of the city along a street full of cars and noise, with several tram lines, to approach three skyscrapers shining in their blue-glass walls of windows, and think that I am going to experience outdoors. Once at the entrance, the first sign of outdoors is provided by the digital poster above the doors, presenting a group of well-equipped people hiking on a mountain. Figure 4 shows photos taken as I walk towards Nordic Outdoor.

Figure 4. Photos taken on the way to Nordic Outdoors.

The opening ceremony is going to start in a few moments and I find a spot on the pavement. As I wait, I look at the press releases that have been produced for the event.

At Nordic Outdoors, the visitor is given the chance to try a number of exciting activities, to listen to inspiring seminars and to see some of the world’s best adventure films. [press release]1

And we indeed start feeling the adrenaline pumping when we look up at the three men making their way across a highline between the two skyscrapers, at a height of some 60 metres, as the exhibition is formally opened (figure 5). A small crowd follows the event from the ground on the pavement. We are thrilled when the men walk out on the tiny line 60 metres above our heads, a performance that is called highlining. Many hold their breath as the man walking seems to lose his balance for a second, but then he regains control of his body. This happens a few times before we can relax as he has safely arrived at the end of the line.

Figure 5. The opening ceremony with a man balancing on a highline 60 metres above the ground.

Once inside the exhibition, the atmosphere is energetic and exciting. There are people of all ages around me, from dads with prams to older people, but mostly relatively young ones. They all seem very interested in what they see and some of them are clearly eager to try different things.

Surrounded by pictures of cliffs, forests, snow-covered mountains, we make our way among an array of outdoor gear and outdoor people to look at and listen to; it is also possible to try many products and activities. One thing that catches the eye is a large tent village, occupying a

considerable surface made of green floor, where the visitor can try all kinds of tent models. At one stand some people are trying to make a fire with a specific tool and clearly proud when they succeed. At another stand there are shoes waiting to be put on for walking on a wet slippery stone as the salesperson promises that you will not slip. But what attracts most of us visitors is ‘where the action is’: a very tall ‘climbing-cliff’, the slacklines, the BMX track, the children’s obstacle course, the presentations of documentaries about spectacular landscapes and challenging performances (see figure 6).

Nordic Outdoors meets the interest we see around an increasingly active outdoor life in both Sweden and the rest of the Nordic countries. But we want to create something new. An event where experience and interactivity are in focus and where visitors get both wet and sweaty and feel the adrenaline pumping, says Angela Anyai, director of Nordic Outdoors [press release]2

Figure 6. Scenes from Nordic Outdoor: the climbing cliff, the children obstacle course, the slacklines, a documentary being shown, the BMX track, a parkour competition.

On the climbing cliff, you can try climbing by using grips for your feet and hands, secured by the proper equipment and helped by the staff – children seem to be welcomed too. At the BMX track I see young men jumping around ramps and obstacles and balancing on their bikes. I am most impressed by the slacklines, where mainly young men are not only balancing, but also jumping and doing complicated tricks on these narrow lines – I cannot do other than just stare at what they are doing. Children seem to be attracted by the obstacle course that one company has constructed, where, after having put on the company’s functional clothes and a helmet, they go along a

challenging path as they climb some stairs, balance on a beam over some water, crouch on a bed of wooden pieces under a ‘bush’, etc. They seem to really enjoy this and challenge each other to complete the track fast. Finally, I join other people sitting on logs, surrounded by furs and reindeer skulls, to watch a documentary presented by a young man, a photographer – it is easy to become fascinated by the spectacular pictures.

As I walk around, I also notice how the exhibitors are easily identifiable among the people present as they wear clothes clearly showing the brand of their organisation, but also as they are all physically fit and respect the outdoor ‘dress code’: high-function materials suited for challenging performances (light-weight, durable, breathable, etc), accompanied by traditional flannel shirts and greenish and brownish trousers. This is mirrored in many of the visitors’ clothes. When reflecting on whether this place feels outdoors, I realise that the scenery put in place would not be enough.

Being surrounded by many people dressed in this ‘proper’ outdoors way and by outdoors gear makes me actually feel this is outdoors and I realize I am eager to try some of the activities and have some of the products in my hands. As I am in the final stages of pregnancy, I decide not to do this, though. And I am not the only one left to look at others performing. The ones I admire as they do what they have trained for, try something new or talk about past performances are mostly white physically fit men without any visible norm-breaking variation in ability – when it is children practising, they are almost exclusively white, dressed in ways that allow for movement and apparently in control of how their bodies perform. Of course, I could not be everywhere at the same time and I may have missed part of what was going on. But the discussions the night before, at dinner, had somehow anticipated that the focus would be reserved for extreme achievements and white bodies impersonating the ideal of able-bodiedness. When I look at videos and pictures

produced by others about the event and available on the internet, this impression is also confirmed.

Nordic Outdoor – an outdoor place is produced on the initiative of

outdoors companies

In order to add to our understanding of privilege in place, I start by focusing on the place that is being shaped at Nordic Outdoor and, while doing that, foreground whether certain trajectories become more rightfully present, something that I then discuss more at length in the following section ‘Privilege in place’. Building on processual views of space (cf. Beyes & Steyaert, 2012; De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013; Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015), and in particular on Massey’s work (2005), I have defined place as an event consisting of a bundle of trajectories (related to a location) organized in specific configurations, whose throwntogetherness needs negotiation in order for coherence and uniqueness to be produced, an event that is continuously re-produced. In other words, what is interesting in a place is how the throwntogetherness of trajectories is handled in order to produce a sense of authenticity. Nordic Outdoor can thus be considered as a place produced by the bundle of trajectories that become related to the halls of the Swedish exhibition and congress centre in Gothenburg for a couple of days. Nordic Outdoor is a place that only exists for a short period of time as it is composed of trajectories that almost completely disappear from the location once the exhibition ends. This means that, if the place has to present some form of

uniqueness and coherence in the short time of its existence, it is even more crucial how its

throwntogetherness is handled. In order to analyse how the throwntogetherness of Nordic Outdoor is handled, I will ask the empirical material the following questions:

- Which trajectories are brought to Nordic Outdoor? - Which trajectories come to Nordic Outdoor? - How are these trajectories ordered?

It should be noted that my aim is not to discuss whether Nordic Outdoor is a successful event or whether people at Nordic Outdoor are affected in their identity constructions. What I want to focus on is how organisations in the outdoor industry work on producing a place in order to discuss whether this is related to the accumulation of privilege.

Trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor

Trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor by the participating organisations are bundles of people and artefacts related to specific practices connected to ‘outdoors’ – table 3 provides some examples including climbers (people and artefacts), climbing a cliff face, an obstacle course, etc. ‘Outdoors’ can be argued to be a construction, rather than an entity, that is connected to the enactment of wilderness in terms of an awe-inspiring, even threatening, encounter with nature that provides an occasion for the self to be confronted with the sense of its own mortality (Drenning, 2013). ‘Nature’ itself should not be considered as an entity – rather, different disciplines have foregrounded how portions of the physical environment become culturally appropriated and visually consumed in a way that constructs the physical environment as sceneries, views, perceptions, etc. (Urry, 1992). Nature can thus be treated as a sociomaterial construction.

Table 3. Examples of trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor by the participating organisations.

The trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor could then be understood as trajectories reproducing ‘nature’ in terms of wilderness. When looking at these trajectories, one could ask why, for instance,

Examples of bundles of people and artefacts brought to Nordic Outdoor

Examples of bundles of artefacts brought to Nordic Outdoor

o Climbers: very fit people with ropes, security belts, specific shoes, specific clothes, etc

o Adventurers: athletic people with pictures of them having moved in environments that pose challenges to survival o Professional outdoor film-makers: people dressed in

outdoor clothes with a movie to show that reproduces breath-taking actions performed by fit people on, for instance, mountains

o Company representatives dressed in functional clothes with certain logos

o Competitors in trail-running, parkour, etc dressed in the proper gear for the competition and, at times, showing outdoor companies’ logos on their garments

o The fabricated climbing cliff

o The obstacle course including balancing beam, water, tree branches, etc o Logs, reindeer skulls, reindeer fur, etc o Water, kayak, life-jackets, paddles o Slacklines, supports for slacklines, soft

mats, etc.

you would construct a high cliff that looks as if made of rocks, equipped with designed and

manufactured grips of different shapes to make the climb challenging enough for someone that can exercise force with both arms and both legs and is relatively strong, a cliff that is also equipped with a safety rope. Why would such a fabricated cliff materialise ‘outdoors’? If we consider ‘outdoors’ as the enactment of wilderness, then we can understand that such a fabricated cliff enables the practice of safe climbing – by using grips, a safety belt and rope, a helmet, etc. Climbing has historically developed as one way of enacting wilderness by relating to the physical

environment in ways that challenge the human body and mind and result in awe-inspiring moments (Robinson, 2008). The trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor thus include artefacts that

reproduce certain aspects of the physical environment in relation to the construction of wilderness. They also include extraordinary people able, for instance, to balance at 60 metres above ground. Again, it is the construction of outdoors in terms of confronting one’s own mortality that can be argued to make such a performance into producing outdoors (Drenning, 2013).

The trajectories that the organisations and the exhibition organisers bring to this location are not ‘neutral’ trajectories – as trajectories, they are stories-so-far connected to other stories-so-far. They thus materialise power-geometries that have emerged and developed in other places and at other times as well. In reproducing outdoors in terms of wilderness, in terms of searching for the sublime as an antidote to urban life in order to return to an authentic self, they actualise constructions of whiteness, since the need for the uncontaminated as an escape from modern life can be argued to be a construction related to the construction of whiteness (Drenning, 2013). The creation of natural parks can be seen as a manifestation of such a construction, actively making the physical

environment ‘clean’ and ‘uncontaminated’ for white people (those who could leave their jobs behind) to enjoy as a leisure activity (Merchant, 2003). Even recently, the imagery produced when showing the outdoors is dominated by, if not exclusively composed of, white bodies (Martin, 2004). Not only do the trajectories brought to re-enact outdoors as wilderness actualise constructions of whiteness, they also actualise construction of Swedishness: in the second half of the nineteenth century, worship of nature became a more acceptable form of nationalism in Sweden than those celebrating blood, race or people (Werner, 2014, p. 107). Furthermore, in the enactment of wilderness, adrenaline-fuelled situations are often emphasised, at the expense of more ‘mundane’ parts of the activities (Drenning, 2013). This is also the case at Nordic Outdoor, with, for instance, the opening ceremony consisting of highlining at 60 metres above the ground. The result is a celebration of able-bodiedness in terms of fit and performing bodies that can master the ‘natural’ challenges necessary for re-producing wilderness (Crosbie, 2016). Moreover, again widening the focus to broader power-geometries, longing for the sublime was not part of all white people’s life experience: it was the male body that was the subject that craved for and could experience such transcendence (Larsson, 2012; Humberstone, 2000). For a long time, female bodies were not

allowed to participate in outdoor activities at all and, when allowed, were constrained by particular types of clothing (Larsson, 2012). Conversely, outdoor practices have contributed to

re-constructing gender practices. Quoting Simone de Beauvoir, ’[l]et her swim, climb mountain peaks, pilot an airplane, battle against the elements, take risks, go out for adventure, and she will not feel before the world the timidity which I have referred to’ (1952, p. 333). The evolution of outdoor clothing also bears witness to this – the more space in outdoor activities women took up, the less constraining (and more similar to men’s) clothes they could use, and the more their body could become visible in such public spaces (Larsson, 2012). The trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor thus also actualise the taken-for-grantedness of the male bodies. In some cases this is very explicit, as when celebrating extreme adventurers, the ‘heroes’, who are men equipped with advanced material (and have traditionally been white men with strong bodies and minds). In other cases this is more implicit: women are also present and the artefacts brought to Nordic Outdoors do not exclude women explicitly, but the trajectories brought actualise outdoor constructions in which men are taken for granted and women accepted if they perform like men in enacting wilderness.

To summarise, the organisers of Nordic Outdoor and the organisations participating in the exhibition bring specific trajectories to the halls in Gothenburg that become related in a bundle of trajectories. Such trajectories also connect this place to other places in space-time and their throwntogetherness is already partly organised by such relationships to wider power-geometries. The premises for the production of privilege are laid as the trajectories becoming related have traditionally foregrounded white, able-bodied men as those having the right to be present in the outdoors. The presence of action sports in the same place could have changed which people are taken for granted, but action sports have also traditionally foregrounded white, able-bodied men (Rannikko, Harinen, Torvinen and Liikanen, 2016) and therefore the trajectories related to action sports (for instance, bikes without a saddle and the elements of the BMX track) reinforce, rather than contest, the central position of certain trajectories.

Trajectories coming to Nordic Outdoor

I now turn to trajectories invited and coming to Nordic Outdoors (and not directly controlled by the organisations). The event is open to everyone who can afford to pay approximately 10 euros for some entertainment. While this already excludes a number of people, there is a large part of the population, at least in Gothenburg and the nearby towns, that could consider coming. The way in which the event is marketed invites certain people, though. It is emphasised that this is something for those wanting to become soaked and to sweat, for those ready to challenge themselves, for those who want to feel the adrenaline pump. The adjective ‘Nordic’ in the name of the event is also reinforced by pictures of Swedish landscapes, which means that the aim is to attract people interested in Nordic wilderness.

As the majority of the organisational representatives are dressed in high-function clothes and shoes, it is easier to treat visitors dressed accordingly as being a ‘natural’ part of this place compared to people dressed in casual, but not outdoor, clothes. Although this is not really spelled out, it can be hinted in comments regarding the quantity and diversity of people present. For instance, the organiser, explains the anticipated presence of older people by referring to the Tur exhibition present in the same facilities. Hence, it seems that the organiser, who represents the companies and organisations that want Nordic Outdoors to happen, envisions a place in which the non-older are the ones that should become soaked and sweaty and feel adrenaline pumping. This is interesting since the co-presence of Tur, a tourism exhibition which gathers trajectories connected to other power-geometries, seems to partly open for new trajectories (older people) compared to the previous year, but such trajectories may still not be considered as rightful presences in this place.

In summary, the organisers of the event try to attract certain trajectories to the halls of the exhibition; certain trajectories (people and artefacts) seem to have a more uncontested right to be present as they mirror the trajectories already brought there by the organisers, while others are accepted but need possibly to be explained (older people, for instance). Hence, of the trajectories coming to Nordic Outdoors, certain become unproblematically related to those brought by the organisers, while others are not obviously related to them. In the next section, I will explore how this emergent bundle of trajectories is ordered.

Ordering the bundle of trajectories

Following Massey (2005), the production of place is political: it is connected to ordering attempts, codification of space, negotiation of the terms for connecting, and who gets the right to be present. Central to how Nordic Outdoor is enacted are the outdoor practices performed that involve visitors and connect them to the people and artefacts brought to the location by the organisations. I would like to propose that it is in the practices carried out that the bundle of trajectories is being ordered and the terms for connecting are being negotiated.

There are, of course, a number of practices being performed as this place takes form. I focus on those that I would argue are the ones distinguishing this place from other places (an exhibition about food, for instance), making this place outdoors. Hence, I do not analyse the selling practice, for instance. Rather, I foreground two kinds of situations: those in which visitors are admiring outdoors as presented/performed by others and those in which some visitors are included in doing outdoors.

documentaries and seminars, showing practices such as highlining, trail-running, or going on an expedition. In these practices, the representation of what outdoors is about is controlled by the organisations and the event organisers, while visitors are made into spectators. In all these situations, as previously discussed, trajectories related to whiteness, able-bodiedness, mostly masculinity, and advanced materials are made into rightful presences, while others confirm such centrality by admiring them (see the people “looking at” in figure 6).

The second category includes the slacklines, the climbing pillar, and the children’s obstacle course. While no one is explicitly excluding any trajectory from becoming related to such artefacts by performing outdoors in relation to them, it is only certain trajectories that enter such a relationship. As described above, the artefacts and the outdoor practices are not neutral: they transport certain power-geometries to this location. As people coming to the event meet these artefacts and the company representatives, some of them become rightful presences taking the stage and performing outdoors, while others are made into spectators. As an example, the children’s obstacle course is a very appreciated spot with a lot of laughing kids making their way on it. But before starting, they need to put on highly functional clothes, thus reproducing the ‘natural’ and necessary role of these artefacts in doing outdoors. Moreover, given how the track is constructed, only children not presenting any norm-breaking variation of mobility can take part in such doing of outdoors (compared to the man with crutches looking at them in figure 6). The track, in other words, does not reproduce a neutral physical environment; it is a reproduction of wilderness, which includes challenging the body by demanding balance, strength and agility.

To summarise, as Nordic Outdoor emerges and is produced as place, the bundle of trajectories that makes this place is being organised and ordered in ways that make some trajectories rightfully present, while others not. This is done as trajectories are brought to the location, as trajectories are invited and come to the location, and as practices are performed that put in relation these two kinds of trajectories. In the next section, I elaborate on how this can be understood as accumulation of privilege happening as place emerges.

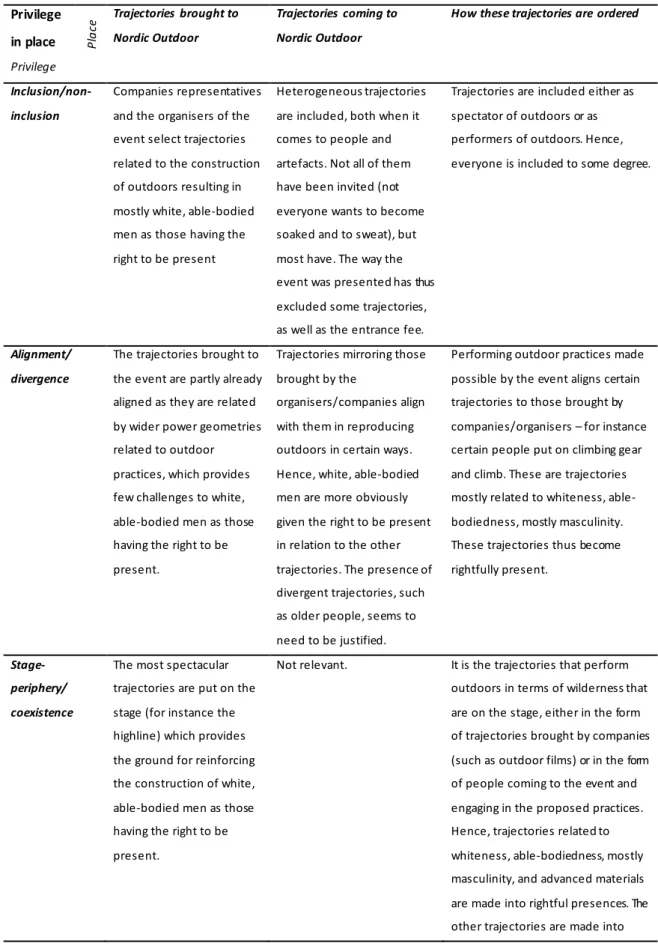

Privilege in place

Having looked at which trajectories are brought and come to Nordic Outdoor, as well as how such a bundle of trajectories is ordered, I now turn to a more articulated analysis of such processes in relation to privilege accumulation by further discussing how certain trajectories become more rightful presences than others in the emerging place (Case et al., 2012). The central question is what happens when the throwntogetherness of trajectories is organised into ‘outdoors’. When I

considered the trajectories brought and invited to the event and how they are ordered (as presented in the previous section) in relation to how the throwntogetherness of such trajectories is handled so that the place becomes coherent and trajectories convergent, I could identify three dimensions that affect how certain trajectories are made into rightful occupants of the place, and others are

rendered marginal presences, thus producing privilege. These empirically-grounded dimensions of throwntogetherness are: inclusion/non-inclusion, alignment/divergence,

stage-periphery/coexistence. Table 4 provides an overview in relation to the three processes explored in the previous section. It should be pointed out that my analysis does not identify any single actor that works with these dimensions; rather, it is in the interaction between people, artefacts and practices that such dimensions are articulated in a way that makes this place into a place where certain trajectories are central without other trajectories claiming space for plurality and contestation.

Inclusion/non-inclusion refers to the fact that trajectories that are going to become part of the bundle of trajectories are selected, to some extent. This happens explicitly when

organisers/companies bring certain trajectories, and more implicitly when trajectories are invited to the event. Inclusion is, analytically, the first dimension that influences whether certain trajectories become rightful presences or not.

Alignment/non-alignment refers to the fact that certain trajectories become aligned with each other, while others do not. For instance, trajectories brought by companies are all related to the

construction of outdoors in terms of wilderness and are therefore to a great extent aligned with regard to the meaning and uniqueness of the place being constructed. Older people, in contrast, are considered divergent trajectories as their presence needs to be accounted for. Alignment is thus the second dimension that influences which trajectories are rightful presences.

Finally, stage-periphery/coexistence refers to how trajectories are positioned in relation to each other. On the stage means that certain trajectories are put on a metaphorical stage to be admired by others (sometimes the stage is actually literally present) that are thus placed on the periphery and confirm the rightful presence of those on the stage. Coexistence would instead be a situation in which a plurality of trajectories is recognised and valued. Moving certain trajectories on the stage is partly done when designing the event and deciding which spots and actions should attract the attention of the visitors, but also in the doing of the outdoors practices that are showcased at the event and in which visitors can participate (see the people “looking at” in figure 6). Being on the stage is thus the third dimension that influences which trajectories are rightful presences.

Table 4. The production of privilege in relation to the production of place at Nordic Outdoor.

Hence, the production of privilege takes form in a rather subtle way without being visible as such. There is no explicit exclusion; rather, in the interplay of inclusion, alignment and taking the stage,

Privilege in place Plac e Trajectories brought to Nordic Outdoor Trajectories coming to Nordic Outdoor

How these trajectories are ordered

Privilege Inclusion/non-inclusion

Companies representatives and the organisers of the event select trajectories related to the construction of outdoors resulting in mostly white, able-bodied men as those having the right to be present

Heterogeneous trajectories are included, both when it comes to people and artefacts. Not all of them have been invited (not everyone wants to become soaked and to sweat), but most have. The way the event was presented has thus excluded some trajectories, as well as the entrance fee.

Trajectories are included either as spectator of outdoors or as performers of outdoors. Hence, everyone is included to some degree.

Alignment/ divergence

The trajectories brought to the event are partly already aligned as they are related by wider power geometries related to outdoor practices, which provides few challenges to white, able-bodied men as those having the right to be present.

Trajectories mirroring those brought by the

organisers/companies align with them in reproducing outdoors in certain ways. Hence, white, able-bodied men are more obviously given the right to be present in relation to the other trajectories. The presence of divergent trajectories, such as older people, seems to need to be justified.

Performing outdoor practices made possible by the event aligns certain trajectories to those brought by companies/organisers – for instance certain people put on climbing gear and climb. These are trajectories mostly related to whiteness, able-bodiedness, mostly masculinity. These trajectories thus become rightfully present.

Stage-periphery/ coexistence

The most spectacular trajectories are put on the stage (for instance the highline) which provides the ground for reinforcing the construction of white, able-bodied men as those having the right to be present.

Not relevant. It is the trajectories that perform outdoors in terms of wilderness that are on the stage, either in the form of trajectories brought by companies (such as outdoor films) or in the form of people coming to the event and engaging in the proposed practices. Hence, trajectories related to whiteness, able-bodiedness, mostly masculinity, and advanced materials are made into rightful presences. The other trajectories are made into

certain trajectories become rightful presences, others do not. The analysed throwntogetherness is characterised by rather extensive inclusion, but also by relatively strong alignment among trajectories reproducing outdoors that are then put on the stage, while those not aligned become more peripheral. This results in certain trajectories becoming taken-for-granted rightful presences and thus in privilege accumulating. Given the wider power-geometries related to Nordic Outdoor and connected to other outdoor places, such rightful presence becomes related to the interplay of whiteness, able-bodiedness and masculinity, as the previous section anticipated and table 4 illustrates. I would therefore argue that, as place emerges in the gathering and ordering of

trajectories, privilege accumulates, given how the throwntogetherness of such trajectories evolves with respect to the dimensions of inclusion/non-inclusion, alignment/non-alignment and stage-periphery/coexistence.

In the event presented, company representatives heavily influence how the throwntogetherness of trajectories is handled. Still, there is the possibility to contest how the place is being constructed, but trajectories that may cause conflicting practices to surface seem to be re-ordered without any contestation breaking out. For instance, children, as trajectories, have not traditionally been central to outdoor places. At Nordic Outdoors, children are invited to participate and practice outdoors – such inclusion adds different stories and ways of practicing outdoors, but re-enacts able-bodiedness and whiteness as central to the place, given the performance that children are supposed to engage in.

Privilege can thus be argued to accumulate in a taken-for-granted fashion. Some trajectories are granted more rightful presence than others, given how the throwntogetherness of the bundle of trajectories is handled to produce an outdoor place. While place is constructed, privilege is produced. In the next section, I elaborate on this by discussing how ‘privilege in place’ means that privilege is organically meshed in place.

Discussion – Privilege meshed in place

This study adds to current understanding of social difference in relation to space and place in organisation studies by pointing to the importance of understanding privilege as accumulating in the same process of configuring trajectories that gives shape to the place in which privilege emerges. The relationship between privilege and place can thus be understood as more than a mutual process of influence (place influences privilege and privilege influences place). Rather, I propose that privileged is meshed in place: as trajectories are brought to a location, invited to come, and ordered they also become included (or not), aligned (or not), and positioned on the stage/on the periphery (or not). At Nordic Outdoor, privilege did not accumulate after the place was ‘there’, accomplished, and the place was not affected by a privilege already present at the location – both

privilege and place were gradually constructed, starting with the organisers and the companies trying to design the configuration of trajectories to become the bundle of trajectories producing Nordic Outdoor, and continuing with the contribution of a great number of trajectories that became related to such a bundle. Building on processual understandings of space and place in organisation studies (Beyes and Steyaert, 2012; De Vaujany and Mitev, 2013; Sergot and Saives, 2016), this study foregrounds how ‘sameness’ is produced. In fact, while different strands of theory recognise that social difference is reproduced in specific social practices – for instance Dacin, Munir and Tracey (2010) show how the dinner rituals at a prestigious university may be argued to maintain the British class system – studies of social difference that have taken spatial work and dimensions into consideration have mostly focused on ‘difference’: on how segregation,

subordination, exclusion, and resistance to such dynamics are spatially achieved. They thus also often focus on women when gender is the studied category (Tyler and Cohen, 2010; Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015). This is related to the fact that such studies mobilise the concept of space, not place, and therefore focus on a dimension, space, that is constructed in the relating and ordering of trajectories. Analysing how space is constructed enables us to see both how trajectories are

segregated and positioned in relation to each other, and how different actors affect such a separation and positioning (see Wasserman and Frenkel, 2015, for instance). My contribution is complementary and focuses instead on ‘sameness’ in terms of privilege and place. It points to how the taken-for-grantedness of both privilege and place is achieved by turning our attention to the trajectories that become ‘natural’ presences thus connoting the place, in this case Nordic Outdoor as an outdoor place, and how this happens. I would argue that in order to study privilege, the concept of space is less useful than the concept of place. Building on a processual understanding, I am not claiming that place is essentially unique or authentic (as other understandings would hold). Rather, what is interesting about place is that it needs to be performed in certain ways in order for the bundle of trajectories of which it is composed to become coherent enough. Hence, while space directs our attention to unfolding relations – and therefore is helpful in studying social difference and power– place directs our attention to constructions of convergence, meaning closure and authenticity – and therefore is helpful in studying privilege and power.

It should be kept in mind, in any case, that according to Massey, the coherence of place is always potentially contested and multiple stories coexist. In this study, I mostly foreground the

achievement of coherence, but mention that possible divergences did not seem to lead to any impactful alternative construction of the place. Further studies could focus more on the plurality of stories and possibly co-existing different configurations of trajectories in a location – how do they relate to privilege accumulation?