- SWAPnSAVE -

A Design Proposal

for collectively reducing

Carbon Emissions

Kristina Arnold

Kristina.arnold@outlook.de Interaktionsdesign Bachelor 22.5HP May 2020Abstract

This thesis contributes to Sustainable Interaction Design by exploring how an eco-feedback enriched design proposal may engage people to collectively reduce carbon emissions. Taking a participatory design approach, the project identified fashion consumption as an area of opportunity towards this aim and proposes a design concept as an alternative to resource and emission-intense consumption by engaging swapping and renting of fashion.

Challenges found in field research with regard to re-using fashion were problematised, namely quality, trust and fairness. The project aimed to address these challenges by conceptualizing an engaging user experience that creates a community between people to share fashion with each other. Values and unique qualities of fashion were investigated as well as how visualizing the environmental impact of such activity affects user engagement. User testing suggests that such eco-feedback positively impacts engagement with the proposed concept.

Keywords: Sustainable Interaction Design, Eco-Feedback, Sustainable

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank everyone who supported the progress of this project: my supervisor Lizette for providing useful tips on literature throughout the project, Taner and Emelie for their continuous support and everyone that contributed their time for interviews, the co-design workshop and user tests. Also, a tremendous thank you to my family for their continuous support. Thank you!

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT ... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ... 4 1 INTRODUCTION ... 6 1.1 PURPOSE ... 6 1.2 CONTRIBUTION ... 7 1.3 RESEARCH QUESTION ... 7 1.4 TARGET GROUP ... 7 1.5 DELIMITATIONS ... 8 1.6 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 82 THEORY AND METHODS ... 9

2.1 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 9

2.2 DESIGN RESEARCH METHODS ... 10

2.2.1SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEWS ... 11

2.2.2 PARTICIPANT OBSERVATIONS ... 11 2.2.3 CO-DESIGN WORKSHOP ... 12 2.2.4 PROTOTYPING ... 12 2.2.5 USER TESTING ... 13 3 FIELD RESEARCH ... 14 3.1 INSIGHTS INTERVIEWS ... 14 3.2 DESIGN OPPORTUNITY ... 17 3.3 CO-DESIGN WORKSHOP ... 17

3.4 INSIGHTS INTERVIEWS PHASE II ... 21

3.5 INSIGHTS PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION ... 22

4 DESIGN ... 24

4.1 THE DESIGN CONCEPT ... 24

4.1.1 INSIGHTS ON FASHION AND SUSTAINABLE FASHION ... 24

4.2 LOW FIDELITY PROTOTYPE I ... 26

4.3 USER TESTING I ... 28

4.4 PROTOTYPE II ... 29

4.5 USER TESTING II ... 33

4.6 DESIGN FOR FASHION AND ECO-FEEDBACK EXPLORATION ... 33

4.6.1 ECO-FEEDBACK DESIGN CONCEPT ... 34

4.6.2 FASHION EXPLORATION CONCEPT ... 35

4.7 HIGH-FIDELITY PROTOTYPE IV ... 38

4.8 USER TESTING IV ... 43

4.9 ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION FINAL USER TESTING ... 44

5 REFLECTIONS ... 45

5.1 RESULTS ... 45

5.2 DESIGN PROCESS REFLECTIONS ... 47

5.3 FUTURE WORK ... 49

5.4 CONCLUSIONS ... 50

6 REFERENCES ... 51

1 Introduction

Climate Change is the “defining issue of our time” according to the UN (n.d.) and data indicates continuously rising global temperatures over the past years (NASA, n.d.). Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion pressure governments and the economy to implement political changes while media coverage increases awareness of the urgency to act now.

Climate Change requires coordinated responses as it is a complex collective action problem (Smith & Mayer, 2018). It cannot be tackled by voluntary action of individuals alone but entire societies need to change the way they produce, consume and live. This thesis hypothesizes that Sustainable Interaction Design (SID) can play a role to identify design solutions that can motivate and unite people, inspire and create a feeling of being accountable for the decisions we take towards each other and the society as a whole. As Stegall (as cited in Blevis, 2007, p. 508) suggests, it is “the role of the designer in developing a sustainable society (is) not simply to create sustainable products but rather to envision products, processes and services that encourage widespread sustainable behaviour”.

The thesis aims to contribute to SID research by proposing a design concept that encourages such widespread sustainable behaviour by engaging people to collectively reduce their negative impact on climate change.

1.1 Purpose

SID research focuses largely on designing interactive technology to promote sustainable behaviour in users (Blevis, 2007). 70% of previous design research took a prescriptive approach to change unsustainable behaviour with persuasive technology, based upon Fogg´s theory of persuasive technology (DiSalvo, Sengers & Brynjarsdóttir, 2010). Such approach entails a judgement where the designer decides upon which behaviour is desired. However, literature voiced concern about the extent to which designers should drive user behaviour (Ceschin & Gaziulusoy, 2016).

Also, less research focused on design opportunities for collective approaches. Foth, Paulos, Goodman and Dourish (as cited in DiSalvo et al., 2010) claim a research gap to address collective settings and suggest moving away from focusing on individuals alone. Similarly, de Jong, Önnevall, Reitsma & Wessmann (2016) propose shifting the focus away from aiming solely at behavioural change of individuals. The thesis aims to address this research gap by identifying design opportunities with a potential to engage people collectively in creating sustainable behaviors instead of prescriptively aiming to target individual behavior.

As literature suggests is individual willingness to environmental action strongly influenced by collective dynamics and perception of other´s

responsibility and actions (Buchanan & Russo, 2015). Corraliza and Berenguer (2000) stipulate that people become more environmentally active when they perceive their environment to be conducive to it. Climate change is a classic social dilemma (Buchanan & Russo, 2015), where individuals have little incentive to act but acting is rational for the entire society in their collective interest (Smith & Mayer, 2018).

However, such required collective action does not arise spontaneously, but people need to imagine the possibilities of how the social world could be different (Cohen-Chen & Van Zomeren, 2018). The thesis hypothesizes that SID can contribute to leverage peoples willingness to reduce their carbon impact by proposing such possibilities.

1.2 Contribution

The thesis aims to contribute to the creation of SID knowledge by exploring how an Interaction Design proposal can connect people in a way to convince them of their collective effectiveness (Pan & Blevis, 2014). The thesis aims to identify a meaningful design space where such opportunity can unfold by taking a participatory design approach. By involving stakeholders throughout the process, the topic is unpacked from a peoples perspective to identify relevant issues and design opportunities on which a design concept will be based.

Findings of this thesis can be interesting to researchers and practitioners focusing on how SDI can contribute with design concepts towards reducing our negative impact on the environment and climate change in specific.

1.3 Research Question

The exploration started with the general problem statement: how can

Interaction Design contribute towards reducing people´s impact on Climate Change by taking a collective approach?

1.4 Target Group

The target group have been people living in Sweden that are concerned about their personal impact on climate change and have either taken personal action to reduce their impact or have an interest in doing so. In order to have variation in the target group, people from different age groups and life situations were included in the research ranging from students to full-time workers and parents.

This target group was expected to have a good overview of the topic while assumingly being confronted with frustrations and needs in relation to the topic. The aim was to identify specific problems that may qualify as design opportunities for given problem statement.

The scope of the target group had been narrowed down during the design phase to include people with an interest in fashion that are also concerned about their impact on climate change. Specifying the target audience ensured that user feedback on the design proposal was relevant and to gather insights into user needs and behaviour with regard to the design concept.

1.5 Delimitations

The insights of this project are limited to users in Sweden where all participants were based at the time of their contributions. This is relevant as behaviours of consumption and perceptions around the research question are likely different between countries for reasons such as economic background or cultural differences.

1.6 Ethical Considerations

The project adhered to the rules and guidelines as provided by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, 2017) and personal data was processed following the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 2018).

All interview participants were informed about the project, its goal and the purpose, usage and storage of their private data before each interview and contribution. All participants reviewed and acknowledged the letter of consent and approved it orally in the interview recording. No participant requested a written consent confirmation though. For all images of people included into this project, prior oral consent was given.

Interview recordings and pictures from the participant observations, the swopshop visit and co-design workshop are stored for the duration of the thesis project on my laptop. There were no objections of any participant on data security throughout the project. All contributions are anonymized in this project so no private information is being exposed and neither name nor age are being mentioned. Gender was only mentioned where it was relevant to the purpose of the thesis.

In addition, all participants were informed why they were invited, how they contribute to the project and what was expected as the outcome for their contribution. They were also informed that their contributions might be viewed by researchers when reviewing the thesis project. Recordings and field research data was reviewed during analysis of each research contribution. The data will be deleted from local files following the finalization of the thesis project.

In addition, the thesis touches upon ethical issues around personal values, lifestyles and political and ethical questions of individual and collective responsibility with regard to climate change. The project strictly avoided any judgement about personal values and beliefs, but focused exclusively on identifying needs and issues of people to frame the design work.

2 Theory and Methods

Subsequently, theoretical perspectives relevant to the research question as well as research methods are outlined to set the stage for the following Chapter that elaborates on how literature insights and methods are applied during field research and the design process that led to the proposed concept.

2.1 Literature Review

Knowledge from SDI research contextualizes the project as SDI research looks at design as “an act of choosing among or informing choices of future ways of being” (Blevis, 2007, p. 503) which is also intended with present research.

SDI Researchers focused on designing for people to adopt a sustainable behaviour, based on social sciences or behavioural economics (Ceschin & Gaziulusoy, 2016). Research findings with regard to means, drivers and notions of individual and collective behaviour both from the SDI and environmental psychology fields provide insights for framing the scope of the project.

A growing body of SDI research focused on reducing energy consumption and unsustainable practices, often designing persuasive systems and technologies that provide eco-feedback on user behavior (Petkov, Goswami, Köbler & Krcmar, 2012). To achieve pro-environmental behaviour, such concepts offer information, game dynamics or leverage social influence, based on the assumption that people lack knowledge, understanding and awareness how their activities affect the environment (Froehlich, Findlater & Landay, 2010). To understand why people may engage in pro-environmental behaviour can behavioural change models provide guidance: rational choice models see it mainly as driven by self-interest of people, whereas norm-activation models view pro-social motives as most important. Norm-activation models are useful in present context to unpack and understand potential drivers of action: personal norms and understanding the negative consequences of action for others can drive pro-environmental behaviour (Froehlich et al.,

2010). Incorporating elements in the design process that inform and speak to

personal norms, by including relevant eco-feedback, can prove useful in present context.Furthermore, literature from environmental psychology and behavioural science offer insights into unpacking the notion of collective action versus individual action to understand drivers and motives.

Fairbrother (2017) argues that trust is a crucial element in achieving collective behaviour towards reducing negative impact on climate change. Tam and Chan (2018) as well as Smith and Mayer (2018) found a significant

relationship between trust between people and environmental behaviour suggesting that mutual trust helps to overcome the dilemma that people feel reluctant to contribute when fearing to be exploited by free riders. Rothstein (2005) called this the “social trap” where lack of trust reduces the effect of risk perception on climate behaviour. Trust appears especially relevant when accurate information about the severity of a potential risk is missing or unknowable, with climate change being such a type of risk (Smith & Mayer, 2018).

Also relevant for collective action appears to be hope. Research suggests that if a group has high hope for social change, it motivates collective action and group efficacy (Greenaway, Cichocka, van Veelen, Likki, & Branscombe, 2016). Research from psychology showed as well that normative messages and statistical information regarding environmental behaviour can directly motivate others that are not yet environmental conscious to act as well (Truelove & Gillis, 2018).

It appears that trust, hope and relevant environmental information are drivers to be considered in the design process. However, most importantly the project needs to unpack the issues and perceptions of people relevant to the problem statement. By applying the field research methods as described below, relevant issues of people are identified to derive meaningful and real design opportunities for exploring in the ideation process.

2.2 Design Research Methods

The project followed the “Double Diamond” iterative design approach of the British Design Council (Design Council, 2005) that describes four phases of the design process: discover insights about the design space, define design opportunities, develop concepts and ideate them in the deliver phase. The approach emphasizes how the design process diverges to create as many ideas before refining them to the best idea by converging. The double diamond approach was used as a mental model for structuring the design process. During the discover phase, the project gathered insights from academic literature and field research that was conducted by semi-structured interviews and participant observations (Muratovski, 2015). Subsequently, analysing the gathered insights and problems, a specific design opportunity with regard to the problem statement was defined (define phase). The design process then diverged again to ideate and iterate on a design concepts that were subsequently converged by prototyping one concept that was iterated further by user testing.

As mentioned, the project took a participatory design approach to involve people not trained as designers into the design process. People are the experts of their own experiences and needs and serve as valuable input partners, experts and influenced the design process and outcomes (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). Involving the target audience in the beginning of the

design process was central to identifying relevant problems and opportunities for a design concept while the outcome was still unclear in terms of design space and whether it will be a service or an interface (Abras, Maloney-Krichmar & Preece, 2004).

2.2.1 Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews served as the main field research method to gather knowledge and insights into users perceptions, meanings and issues about acting towards climate change individually but also collectively. It also laid the foundation for identifying problems, insights and identifying a design opportunity to be explored during ideation.

The qualitative interviews were semi-structured with questions and themes prepared but open to situate changes (Kvale, 2008). The interviews unpacked areas of major struggle for a person with regard to climate change, gained insights about specific problems, the role of others in their social networks and feelings and drivers towards personal action. All interviews created an open space without being judgemental about personal values and opinions. The interviews followed a script but allowed flexibility to explore aspects important to the stakeholder spontaneously. This was intended to let the design process be guided by the stakeholders and explore issues they deemed important.

Following some unstructured interviewing during demonstrations of Fridays for Future in Lund, seven semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of the target audience. The interviewees comprised of three students of Lund’s University studying Environmental Science and seven adults aged 30-45. Following identification of the design opportunity, another three interviews were conducted to gather knowledge around sustainable fashion and clothes swapping specifically.

The qualitative data from the interviews were analysed by using Affinity Diagramming (Hangington & Martin, 2019). The analysis was done by reading the material, sorting data in post-its, finding stories, issues and derive meanings, patterns and common issues. Analysing and interpreting the data to identify problems served as inspiration to define the design opportunity.

2.2.2 Participant Observations

After narrowing down the design opportunity, I collected further insights during a participant observation at a clothes swap at Malmö University. Participant observation is a method where the researcher takes part in an activity as an observer together with the people that are full participants as a way to learn the context and aspects of this specific activity. As both a data

collection and analytic tool, this method enhanced the information gathered in the interview phase but also enriched the interpretation of the field data (Musante & DeWalt, 2010).

The aim for participating in a clothes swap myself was to unpack the meaning of physical swapping, gather deeper insights and understanding of the behaviour and needs of people and formulate new research questions. I both participated in the activity and closely observed myself and other participants while taking notes. Also, I used informal conversations as an interview technique, spending time with the people at the event and recording my observations through field notes and pictures (Musante & DeWalt, 2010).

2.2.3 Co-Design Workshop

A one-hour co-design workshop included relevant stakeholders directly in the design process, unpack the design opportunity together and gather as many diverse ideas as possible for ideation (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). The workshop was conducted with two students of Interaction Design with a strong interest in both climate change and fashion and one student of Environmental Science in Lund University that participated in the interview. I participated myself in the activities instead of solely being a facilitator as many participants cancelled due to the pandemic.

Everyone was encouraged to think outside the box and write down as many ideas as possible individually for the design challenge: “How might we reduce overconsumption by designing for new and engaging was to consumer less and more sustainably?” All ideas were hung up on a wall, read out loud but not discussed due to time constraints. Participants were then asked to choose one of these ideas to be developed together in a 15 minutes brainwriting session. Brainwriting is a method where one idea is developed on one sheet that is being passed from one person to the next (Interaction Design Foundation, n.d.). The method was chosen as participants could build upon each other´s ideas in a short timeframe and in silence, offering the chance to reflect individually while also inspiring each other and avoiding lengthy discussions.

2.2.4 Prototyping

Based on the design ideas developed during the co-design workshop, the chosen concept was explored through prototyping aspects of it. According to Houde and Hill (1997), a prototype is defined as any representation of a design idea and tests the look and feel, the role but also the implementation of such design concept, meaning the potential function of the prototype for a user, the sensory experience of using it and the technical components of how it could work. Prototyping gathered knowledge about the design concept and

different qualities and meanings of the concept such as environmental feedback and user interaction (Lim, Stolterman & Tenenberg, 2008).

First ideas were sketched quickly on paper to take early design decisions whereas chosen ideas were later prototyped in different levels of fidelity using digital prototyping tools including Sketch, Adobe XD and Invision. The high-fidelity prototype explored the role and implementation of the design concept but also gathered feedback on a potential look and feel.

2.2.5 User Testing

User testing was done to gather knowledge on the aspects explored by each prototype with representatives of the intended user group. The purpose is to inform and iterate on the design concept and identify usability issues for user experience. Usability tests provide insights into what users think is important in the prototype, how they would want to access information, how they feel when performing a task or testing a user flow and generally, how they perceive the efficiency of use of the design concept (Rubin & Chisnell, 2008). During all user tests, participants were thinking out loud while exploring a prototype (Abras et al., 2004). During all tests it was made clear what the prototype prototypes (Houde & Hill, 1997) in order to receive relevant feedback on questions tested by that specific prototype. Following each test, users were encouraged to elaborate on their impressions and reflections about the design concept and their specific needs.

User testing has been a central element of the design process to gather more information about users perceptions and needs with regard to the concept proposed. Except for one user test, all tests were undertaken remotely through video conferencing. A link to the interactive prototype was shared and tested on the computer and users were observed via screen-sharing. However, this set-up proved to be challenging, as screen sharing was not working for everyone, users had to be closely guided to the areas that were tested and certain aspects, for example swiping interactions, could not be tested properly on the computer as the prototype was a mobile application. Here, insights gathered from the user test may be biased and less reliable, since the functionality had to be explained orally as the mouse interaction did not work as intended.

3 Field Research

3.1 Insights Interviews

A total of 17 interviews were conducted in three stages: seven during a prescreening phase, seven interviews during the main design research phase and three during the final design research phase focused on a more narrowed-down design opportunity. The interviews gathered knowledge around people´s mindset on personal impact on climate change, what they take action on, and which problems and issues they encountered.

Clustering, sorting and organizing findings in the Affinity Diagram (see figure 1) of the seven main interviews visualized recurring patterns of issues: consumerism, data, food and awareness. Most issues, insights and inspiration for design opportunities derived from consumerism and attitudes (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Opportunities organized in Affinity Diagram

Frustration

All interviewees felt frustration to varying degrees around the ignorance of others in their social networks that might acknowledge climate change but do not take personal steps to change their behaviour.

“People are egoistic”- “People avoid the topic to not feel bad”- “I want people to at least reflect about it”

The inactivity of others was explained to be related to feelings of not having any personal impact on climate change and not being responsible while large polluters such as China would be accountable instead. Here, missing trust in others to take their responsibility appears to be a driver for personal inactivity as was found by Smith and Mayer (2018) and Tam and Chan (2018), or as Rothenstein (2005) called it, the “social trap”.

Food

An area where diverging patterns evolved was food and eating habits. Issues and opportunities were contradicting: some felt to have a positive impact on others by leading as an example while others were frustrated as their networks were not receptive to change. However, some examples demonstrated the positive effect of inspiring others to change: one interviewee said her network of friends and family turned her vegetarian while another person was successful in inspiring her friends by showing alternatives to meat.

Transportation and Data

Nearly all interviewees named flying habits as a difficult area for change as overseas travel is needed for family visits or studies. Another finding revealed that understanding the personal carbon footprint was not conducive to behaviour change and even contrary, reduced motivation. One interviewee claimed to have taken all possible personal steps towards a reduced carbon footprint and calculating the carbon footprint resulted in a much higher value than expected. For him, realizing that his tedious personal efforts did not result in a smaller footprint, had a discouraging effect.

Consumption

A recurring pattern during all interviews was the concern around consumption as this was acknowledged as being an area were one has a large impact but were changes are feasible. Every interviewee mentioned the personal goal to reduce consumption, use second hand or even aiming to influence their networks to reduce carbon emissions related to consumption. One interviewee felt that “everyone has too much stuff” and that “people want to get rid of stuff.” This indicates that due to high consumption rates, people have collected things, that often are not of use or value anymore. Interviewees also mentioned barriers with regard to re-using items by second hand shopping. One interviewee observed hesitance of friends to shop certain products second hand like shoes. “I try to convince my friends to go shop second hand with me but I have not been so successful.”

One interviewee mentioned the missing trust when it comes to buying second hand electronic items and another that quality of second hand items is oftentimes low: “You want more high quality second hand.” This expresses a need for having better opportunities to acquire re-used things, from the offer perspective but also a quality point of view. One person mentioned the lack of availability of specific items like a specific hobby equipment. Also, there is continuous stigma and the expectation that “clothes may smell weird” which prevent some people to re-use instead of buying new.

One interviewee mentioned her motivations to only buy second hand clothes: the fun when hunting for good deals, being unique and individual in style, the reduced costs and the passion for fashion that she could express be sustainably this way. Also, the interviewee highlighted the strong attachment and care people developed towards items before handing them over to her, by telling the history of a lamp for example. When giving clothes away herself, she experiences strong joy and fulfilment. Here, the aspects of inspiration, being unique and creating a stronger personal identity were factors to engage the interviewee to exclusively purchase second hand, both for fashion but also other items.

Specific issues that others interviewees mentioned with second hand shopping was the lack of trust on the second hand platforms in Sweden and

insecurity when it comes to purchasing electronic devices. Most interviewees regularly use online platforms like Tradera and only a minority uses physical second hand stores to see and touch the products.

Further, an interviewee mentioned she shared her wardrobe always with family and friends. A similar concept, swapping clothes, was mentioned as a “fun” and community focused activity she engages in to reduce her consumption. The interviewee mentioned specific problems during the events, such as a lack of space, panic to miss a deal, low quality of clothes, difficulties with sizing, fairness and trust and low participation.

From analyzing insights and opportunities, reducing consumption was identified as an interesting design space with inspiring, real and solvable problems for Interaction Design such as the social acceptance of re-using, trust that is required when re-using things but also issues of security. Based on the insights gathered from the interviews, the design opportunity was reframed subsequently.

3.2 Design Opportunity

How might Sustainable Interaction Design help people collectively reduce carbon emissions from consumption?

3.3 Co-Design Workshop

In an one hour co-design workshop stakeholders explored as many ideas as possible on the design opportunity (see figure 3).

Initially and to diverge, the design space was opened up to ideate on how we might reduce overconsumption by designing for new and engaging was to consume more sustainably. The intention was to gather a feeling for what participants feel relevant in that context but also to gather many diverse and inspiring ideas that could be incorporated in the ideation phase.

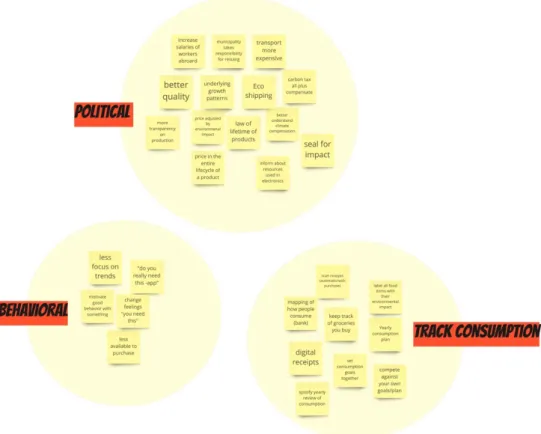

The first round of brainstorming revealed many diverse ideas for example tracking and informing about a person´s consumption by mapping purchases and sharing them, setting personal consumption goals and making consumption plans (see figure 4).

Figure 4: First brainstorming round revealed many ideas on reducing consumption

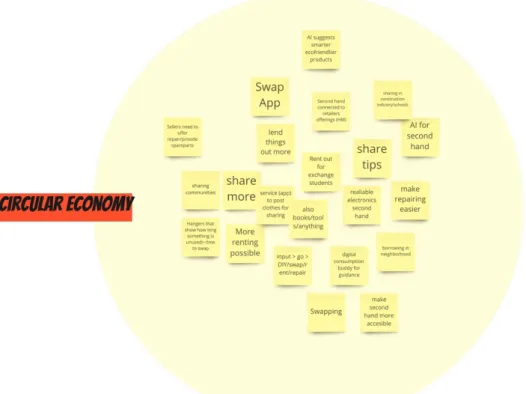

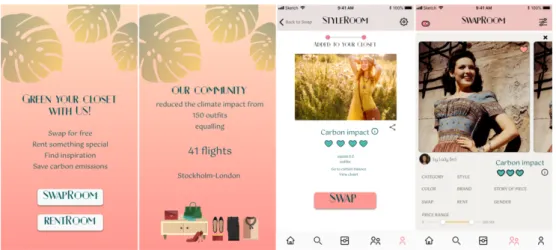

The largest amount of ideas evolved around creating a “circular economy” as shown in figure 5, for example by sharing products after a purchase, renting out, repairing, reusing by lending and borrowing, and using Artificial Intelligence or a digital consumption buddy for making better online purchase suggestions. Participants also mentioned sharing networks and considering the entire lifecycle of products are aspects of changing consumption patterns.

These suggestions were made for products like tools, electronics and clothes and for specific communities like schools or specific businesses like the construction industry.

Following the initial brainstorming, each participant then chose one idea to develop further during brainwriting and a total of four ideas evolved from the group.

Figure 5: Summary of more specific circular economy ideas

The first idea suggested a community platform where items purchased by members are being shared or swapped within the community. A community sets goals, and gets their carbon reductions visualized with the potential to include a competition between teams and you get yearly review of purchases. The second idea built upon using Artificial Intelligence for online shopping in the form of a platform that shows products from different sources ranked according to their environmental impact. The user could define priorities and set goals beforehand. The AI tracks the search and purchase behaviour via credit card plus it provides feedback whether someone is on track to reach their goals. The platform shows how much carbon was reduced by re-using. The third idea focused on creating a circular fashion economy by reselling unsold clothes of large retailers similar to how food leftovers are sold for lower prices. The retailer could even take care of reusing these items by offering swap, reuse and repair services. A profile keeps track of purchases, reductions and swaps and shows carbon reductions.

The fourth idea suggested a circular economy platform “Swap it all” where users can share or swap clothes, a toolbox, games, books or household items. Trust is built by creating small communities within this platform. The platform suggests looks and complementary items and usage is encouraged via a point system and physical meetings are encouraged for hand-over.

During the brainwriting, many ideas kept recurring in each concept such as to create communities, to use AI to find the most sustainable option or visualizing the environmental impact of a solution (see figure 5). Also, having a better overview of which items are in use appeared as a recurring idea. At the end, participants were encouraged to vote and reason for their preferred idea. The majority voted for idea four: the “Swap it all” platform as they felt this is the most promising idea incorporating elements discussed in the other ideas. With regard to the opportunity statement, it appeared to be the most suitable as it speaks to the notion of creating a sort of community as people exchange clothes with each other, thereby supporting each other in living sustainably.

The initial idea from the workshop was not limited or focused to a specific item and participants mentioned clothes, electronics and household items. All items entail very specific qualities though. Household items are typically exchanged less often than clothes based on the insights from Naturskyddsföreningen. Electronic items appear to have very specific issues around whether an item is functional, who would be liable in the case it is not, as was found during one of the interviews.

Earlier field research suggested that clothes are exchanged often and specific problems were for example quality and social stigma for people to not re-use fashion. In addition, findings indicated that fashion has very unique qualities such as identity and uniqueness which makes it an inspiring design space. At this point of the design process, the scope of the design space was narrowed down to focus on fashion as an inspiring as well as relevant area for which most user problems were identified during interviews. Also, the design process can be inspired by the the specific emotional qualities and values of fashion that might be leveraged to design for an engaging experience that inspires people to an alternative way of consuming fashion.

Also, considering the fashion industry is responsible for 10 % of annual global carbon emissions, more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined (UN, 2018), the environmental impact of focusing the concept on fashion appears to be strong too. According to Wrap as cited in James, Reitsma & Aftab (2019) are consumption levels of new clothing around 12,6 kg per person in Sweden, with high amounts going to landfills or remaining unused in wardrobes. Hence, providing an engaging alternative to reduce unsustainable fashion consumption may result in considerable collective reductions of carbon emissions.

To unpack and further understand sharing and swapping of clothes, its drivers, issues and user needs and expectations, the design process further field research was conducted as a next step.

3.4 Insights Interviews Phase II

An additional three interviews were conducted with the founder of the Swopshop in Malmö, a representative of the Swedish Nature Conservation organization “Naturskyddsföreningen” and a student of Environmental Science from Lund University. Questions were targeted to further understand the concept of clothes swapping to identify problems, issues and user motivations.

The interview with the representative of “Naturskyddsföreningen” revealed that people in Sweden change their outfits very often but that they are increasingly aware of negative environmental impacts of fast fashion due to media coverage of the subject. In 2019, 17,000 people participated at the national Swap day in Sweden and 58,000 items were swapped (Naturskyddsforeningen, 2020) with participants asking for even more regular events. From all interviewees it derived that people including men are increasingly interested in clothes swapping. However, it is currently mostly women that use swap events or the Swopshop where 95% are female in the age of 16-35.

A problem of clothes swaps appears to be the logistics and organization: volunteers, storage and physical space is needed, but limited mostly. Often, there is panic among participants to hunt the best deal and frustration when quality is not matching. Quality and trust appear to be crucial notions for swapping to work as low quality frustrates people. The Swopshop owner manually checks quality upon hand in of clothes to ensure customers feel trust and return.

Figure 6: The Swopshop in Malmö

At physical swap events, quality and fairness is difficult to guarantee as participants hand in 5 or 10 items and get a voucher to take out the same amount without knowing the quality or offer beforehand. There is a tendency for people to bring bad quality clothes at big events: “People tend to bring

worst clothes to swap” and some people aim at upgrading instead of renewing their wardrobes.

As quality and offering is unknown beforehand, people for example men may not attend: the organizers of a swap event at Malmö University aimed to get male attendees but they declined as they did not expect anything to be offered. The owner of the Swopshop mentioned her disappointment about the quality at swap events to be the reason for opening the shop. Also, it was difficult finding right sizes because one cannot test clothes on during events. Interestingly the shop aims to change the behaviour for consumption by enhancing the value people attach to products and for people to create a community of sharing. Re-using items has the potential to make people care more about them but also consider quality and longevity in purchase decisions up-front, thereby potentially reducing fast fashion consumption. The shop limits hand-ins to ten items for people to be selective, ensure quality and only items of upcoming seasons are allowed to reduce storage clutter. It appears from the interviews that main challenges of swapping are quality of items, fairness for matching items with comparably equal value, trust to expect something that appeals at an event and insecurities around making a good deal which can create panic and frustrations.

Limitations for physical swapping are that one is limited to a specific swap amount and for finding clothes for men since such clothes are typically not offered. Other opportunities mentioned during interviews were using the swap concept for local situations such as exchange students; and including other items such as household products, home decorations and hobby equipment. To unpack the specific qualities and notions of the concept of clothes swapping even further, a participant observation was conducted.

3.5 Insights Participant Observation

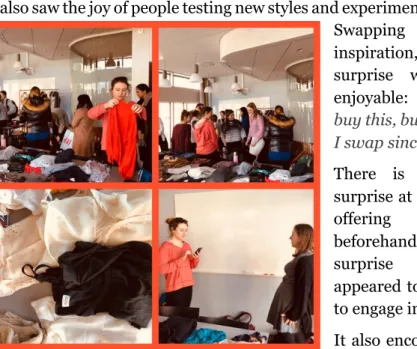

How does it feel to swap clothes and what is engaging in this activity? What is the specific meaning of fashion? At a small swap event at Malmö University I gathered insights on these questions to understand specific notions and qualities of swapping. Selecting items myself for swapping created a feeling of “wanting to make someone happy”, a notion that could be observed in others during the event. Giving and sharing in itself creates a sense of community and enjoyment as I observed in myself and people.

I also saw the joy of people testing new styles and experimenting with fashion. Swapping triggered inspiration, creativity and surprise which makes it enjoyable: “I would never buy this, but I would try it as I swap since this is for free.” There is an element of surprise at such event as the offering is not clear beforehand. This notion of surprise and hunting appeared to motivate people to engage in swapping. It also encouraged people to test new styles: “You can swap it and when you don’t wear it you bring it to the next swap”. Participants commented and supported each other, taking pictures in the absence of mirrors and suggested items to each other. A sense of community as well as mutual inspiration was apparent: “this is so you”, “this looks very much like you”. This also shows the unique quality of fashion to relate to someone´s identity and personal style. Participants told each other the story of an item they swapped with each other, making it valuable and special. “It’s so nice to see where the clothes come from.”

Physical swapping is limited to the amount of items brought in which can create disappointment when running out of items to swap. Even though there were no rules set for the event, it could be observed that fairness in swapping items was managed due to the small size of attendees and community feel. No one was taking more than they brought in, nor could be observed that value of items being swapped was very different, even though there were apparent inequalities of clothes in terms of value and quality. Here, the small size of the event and the personal connections between many attendees may have been conducive to this behavior. Fairness, one of the main challenges identified for swapping, appears to be created by having a community feel and trust in each other. Trust in this context would mean having the expectation of matching quality and that other participants do not aim at upgrading their wardrobe.

Having collected these insights on user motivations and challenges of physical clothes swapping, the design concept from the co-design workshop could be ideated further, as will be laid out subsequently.

4 Design

4.1 The Design Concept

The sharing platform idea was chosen as it appeared the most promising and inspiring concept to create collective engagement into a sustainable behavior by offering an inspirational alternative by re-using clothes. Consumption of new clothes, especially environmentally damaging fast fashion, can be reduced by people swapping items with each other and re-using fashion. It appears to be an alternative to renew the wardrobe while also providing a platform to share clothes that are not in use anymore. Can fashion serve as a positive force to design sustainable interactive experience (Pan & Blevis, 2014)?

Next, such platform could either be designed for desktop or mobile phone. Firstly, consumption of fashion appears to be increasingly done online as a study of Postnord (2019) reveals: 62% monthly purchases are online in the Nordic region, with an upward trend, of which 39% of all online shopping was for fashion items like clothing and shoes in Sweden.

Considering that over 35 percent of consumers in Sweden make online purchases by phone (Axinte, n.d.) and assuming at this point that swapping entails continuous communication between members, a mobile phone app appeared to be the most suitable technology.

Stakeholders for the design phase were refined to include people that care about the environmental impact, but equally are interested in fashion. It is furthermore assumed that there might be different user motivations: whereas some are driven by environmental motivations, are others seeking inspiration and may be driven by fashion considerations with the environmental impact being secondary.

The co-design workshop also brought up the idea to visualize the environmental impact of such swapping platform in order to inform, encourage and motivate members. To design such eco-feedback, insights and learnings from literature as well as related work had to be gathered before designing the concept. Also, additional literature insights on fashion, its meanings, values and drivers were dissected to gather inspiration and frame the design decisions. At this point, the design process diverges to gather further insights before conceptualization the idea, which are both presented subsequently.

4.1.1 Insights on Fashion and Sustainable Fashion

Fashion means “the symbolic, aesthetic, cultural meanings of items and the way artefacts and objects are being used to express taste, lifestyle, social

status and community belonging” (Pan, Roedl, Blevis & Thomas, 2015, p. 53). Similarly, is fashion an inherently social phenomenon “in which individuals engage in activities collectively as participants in the process of producing fashion and sustaining fashion” (Kawamura as cited in Pan & Blevis, 2014, p. 108). Fashion is both a driver for collective behaviour as well as differentiation: “In following fashion we align ourselves with some people and differentiate ourselves from others, but at the same time we enjoy expressing ourselves in a common language that is widely understood” (Sassatelli, 2007, p. 64).

Fry (as cited in Pan & Blevis, 2014, p. 109) claims that “individual action can feed the collective aim, it can be a passage entry into a community of change to become both a contributor and recipient of new knowledge and practice”. Pan and Blevis (2014) hypothesize that drivers underlying fashion consumption can promote reuse, engage in collective sustainable action and making it “fashionable to live with less”. Similarly, Pierce and Paulos (2011) suggest to design for making reacquisition mainstream and promoting reuse by for example creating online communities for sharing.

Here, literature suggests fashion is a driver to form communities based on fashion style, as people attach emotional, personal values and desires to fashion, and it is a symbol of self-identity. Styles are developed in groups and subcultures that express taste and identity (Pan & Blevis, 2014).

Hence, fashion adheres to emotional needs as individuals and social beings and is an identity-creating as well as creative activity. Consuming fashion is also a creative activity where people reinterpret and reorganize items expressing a particular style. Other qualities assigned to fashion include newness, exclusivity, and originality to fashionable goods (Sassatelli, 2007), as well rarity that can make items fashionable and popular (Pan et al., 2015). With newness the author refers to the drive to pursuing trends in order to keep up with latest styles, often to conform. How can the concept leverage these unique qualities of fashion to engage people in sustainable re-using?

4.1.2 Insights from Related Work

Findings from the co-design workshop showed that participants expect to create motivation by providing environmental information about the impact of such platform. The underlying assumption appears to be that such eco-feedback can trigger motivation into a desired behaviour. Here, research of learnings from the SDI community can inform the design process further. Designing for eco-feedback takes the underlying assumption that presenting information to people can provoke a desired behaviour (Froehlich et al., 2010). Feedback is the means through which information, in our case the emission reduction information, is displayed to a person using a visualization device, in our case the mobile app, and it should persuade but also offer

analysis (Pierce, Odom & Blevis, 2008). Eco-feedback technologies have largely targeted electricity usage with 41% of projects in Interaction Design, while others tackled water, transportation, carbon tracking, environmental impacts of product purchases.

Even though these different design concepts had varying success with regard to measuring and retaining long-term behaviour change, studies have shown that eco-feedback technology does affect consumption behaviour (Froehlich et al., 2010). What is meant by eco-feedback could be information, goal-setting, comparison, commitment, incentives and low- and high level feedback. Most design proposals from literature contain multiple options (Froehlich et al., 2010). Relevant strategies for designing eco-feedback are suggested by Pierce et al. (2008) to offer behavioural information and indicators, connect the behaviour to the impacts of consumption, encourage playful engagement, competition and exploration of data, and stimulate critical reflection. Even though Pierce et al. assert great promise into eco-feedback, do the authors suggests such feedback needs to be specifically designed for each use-context and to include considerations around how such feedback remains useful and relevant over time.

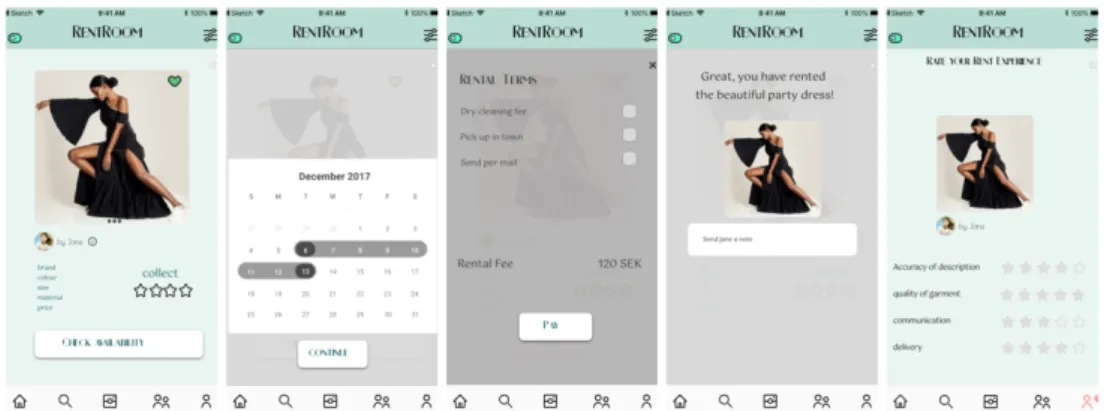

Looking at related practical examples from similar initiatives with regard to fashion, several swapping and renting services were identified, of which however none resides in Sweden. Neither does any of these initiatives and services visualize the environmental impact of the activities of users nor include a combination of swapping and renting. Examples include Swancyapp (https://www.swancyapp.com), a clothes swapping app offered in Norway, and similarly, NUW (https://www.thenuwardrobe.com/) in the UK offering a sharing community, and RenttheRunway in the US that rents out high quality fashion (https://www.renttherunway.com), the latter two being based on a paid subscription model.

4.2 Low Fidelity Prototype I

With the additional insights gathered, were low-fidelity paper sketches conceptualizing first ideas quickly. Since user testing had to be done remotely via video calling and paper prototypes did not qualify for such test, a quick low fidelity digital prototype was done in Adobe XD (see Figure 8).

The aim for the first prototype was to explore overall opportunities deriving from the general concept and hence, a rough flow for the entire app idea was designed. Conceptualizing individual aspects only was expected to not provide answers to the question of how such concept can be an answer to the design opportunity.

The first digital prototype was tested with two Interaction Designers of which one has a professional background in the fashion industry, whereas the other has a strong interest in fashion. These users were chosen in order to get a

quick peer review on the initial concept to prepare the next iteration with a more refined prototype which was intended to be tested with the target audience.

The Re-Use Concept

The re-use basic concept includes the option for users to upload items into their closet, search for items based on price range and other filters as shown in figure 8, and later swap with others or rent out. During the co-design workshop participants suggested renting as a way for re-using items besides swapping. Field research has shown that when running out of pieces to swap, a trade may not happen and therefore renting is assumed to increase flexibility of the concept and was included besides swapping. However, this feature had to be tested with users to understand its usefulness.

Purchasing had been intentionally excluded from the concept in order to prevent such platform from being a second hand marketplace as, instead, if shall form a community that is based on trust and aims together for environmental change.

Figure 8: Selection of wireframes from low-fidelity prototype 1

Quality had been identified as a main challenge for swapping. The concept designs for exchanging individual pieces and not an entire wardrobe to account for quality. Moreover, insights from interviews showed that fairness can prevent swaps: for a fair swap to happen, pieces shall have a somewhat similar monetary value and hence, the option to filter search results according to value was included.

Eco-Feedback

Co-design participants suggested “information” for the concept that shows its environmental impact. Research suggested that information needs to be easily understood, trusted, presented in a way it attracts attention, is remembered and delivered closely in timing and placement as well as is

specific to the action and relevant choice (Froehlich, Findlater & Landay, 2010).

The first low-fidelity prototype visualizes the amounts of carbon emission in tons CO2 saved by the community to encourage interest to explore that concept, stimulate reflection and offer an indicator for the behavioural impact. Showing the total emissions reduced by all swaps and rentals of all members aimed to create a community feel.

Initially, an emission reduction target was included based on the assumption to create a stimuli for people to contribute to such community goal. In order to make the placement of such information relevant to the action, environmental impact information is provided upon uploading an item to indicate how much will be saved when renting out or swapping that item.

Fashion Considerations

The design concept aims to leverage the values and qualities of fashion that were identified during field and literature research. Design considerations should speak to the qualities of fashion as a factor in creating identity, being unique, provide inspiration and creativity and leverage rarity of items. To account for personal style and self-identification, the design concept aims to allow people to personalize their feed by choosing styles (see figure 8). Design considerations were also made regarding identity creation and uniqueness. Identity creation and styles may be accounted for by the creation of connections between users. Being able to follow people that appear as trendsetters by their level of activity can account for creation of identity, as much as showing own items and sharing them with others, for example on social media.

Uniqueness, rarity and personal attachment can be designed for by people telling a story about a piece and listing the history of swaps for an item. The platform may also enable the creation of influencers and trends by showing most-liked items. The functionality of the concept itself with people offering specific personal items allows for rarity.

The first design considerations had to be tested to gather first user feedback on the direction of the design, test design assumptions to further iterate especially the eco-feedback and how to design for the fashion values.

4.3 User Testing I

The test focused solely on the role of the design concept meaning the function of the concept for the user and the role it could play in their lives (Houde & Hill, 1997). The testers were asked to go through the prototype, provide feedback how the environmental information is perceived, if it motivates usage, and which functionalities, concerns and ideas arise while testing it. Users were also asked to describe situations for how they envisage usage.

Both users found the basic design concept of having a combination of swapping and renting of clothes useful: swap felt to be less complicated as one keeps an item and it is for everyday wear, while renting makes sense for special occasions. An idea that evolved in testing was to explore visual differences of both “stores”, comparing it to a fast fashion versus boutique shop. A user would be able to toggle between these shops similar to switching between Netflix profiles. Being presented with the boutique view may feel more attractive to join the community. As the concept needs a significant amount of users to have an attractive offering such approach appeared to be useful.

The low-fidelity infographic screen was perceived both as useful because it helps understanding the community effort in terms of environmental protection as well as motivating. That information was perceived as unusual and surprising to have in an app. It was suggested to add how many users are contributing to provide context and perspective of the data. One user said “when having to choose between different apps, I would rather choose this one that adds the environmental information.” Feedback included also to add environmental information on the introduction page to visualize what impact users could have, incentivising people to join. Also it was suggested relating the data to kg of clothes or a measurement that users understand. One user wanted to share the personal wardrobe on social media, as “clothes have both memory and identity attached”. Here, designing for the specific quality of fashion in terms of creation of identity can be achieved by offering the option to share images to social media channels. The user also suggested the interaction within the app itself will be conducive to user engagement with the concept: “What engages me is the way to interact.”

Overall, user feedback supported the general design idea, but indicated the need to further iterate on the environmental feedback mechanism as well as the way people can interact within the app itself.

4.4 Prototype II

The second prototype aimed to incorporate the early feedback received and test the concept with four more stakeholders that are not designers. At this stage, feedback was needed from non-designers to assess if the concept of combining swapping and renting as well as on the environmental feedback could work before iterating further.

A mood board developed a basic look and feel for users to imagine the concept better. Design decisions were based on Apples Human Interface Guidelines for IOS (https://developer.apple.com/design/human-interface-guidelines/).

Re-Use Concept

Figure 10: Selected wireframes for swap flow

This prototype advanced in terms of presenting the different user flows for swapping and renting. Prototype 2 visualized how the person asking for a swap suggests an item directly with the receiving party having to agree and parties communicating around it (figure 10). Here, the assumption is made that direct communication may help to create mutual trust, a notion found to be crucial for creating communities as literature had indicated. Also, communication enables parties to meet in person for handing over items, which reduces logistic and environmental costs.

Figure 11: Selected wireframes rent flow

The renting flow (figure 11) was designed with inspiration of other renting services: the item is booked and paid for a specific time. This is intended to create security and trust on behalf of the lending party as items may get damaged.

Further, the design assumption was made that renting is about special garments such as wedding dresses, where quality and value is higher. At this point, technical issues like cleaning, delivery, payment and insurance were considered but not designed for due to time constraints.

Eco-Feedback

Figure 9: Eco-Feedback of prototype 2

As the user feedback suggested, needs eco-feedback data to be more contextualized. The environmental data is gathered upon each upload of an item when a specific category is chosen such as jeans, which produces 33,4 kg CO2 (Worldbank, 2019). When a pair of jeans is swapped, the person receiving that pair of jeans will be accounted a reduction of 33,4 kg CO2e. In order to contextualize the carbon emissions and considering that most people understand the climate impact of flights, I related hypothetical carbon data to flight emission for a Stockholm-London flight (figure 9). Also, the decision to allow for an emission target was removed as this raised questions about who would set such target and how it is managed, complicating the concept. Also, it was introduced to be able to write a story about an item upon uploading. The intention is to create value and enhance care for items. From participant observations it was concluded that knowing the story of a garment creates a stronger attachment to the item itself.

Design considerations were also around how to design for delivery by for example drop off points in town to avoid carbon emission from logistics. There is a tension though between the aspect of connecting locally and having a larger variety of offers. At this point, such technical aspects are only considered without being prototyped.

Fashion Considerations

Figure 10: The styleroom concept, uploading an item and settings

Based on the results of the first user test, the concept was iterated to include the feature to follow specific “stylepals” and their closets (figure 10). The design consideration here is for people to show their style identity and connect with others that either have a similar style or are interesting due to their environmental impact in the community. Here, the concept aims to account for the fashion values identified earlier by designing for people to inspire and get inspired, to create identity and offer ways to become creative by choosing new styles.

To account for the idea of having different “shops” of different quality for renting and swapping, this prototype allows to toggle between a rentroom and a swaproom (figure 11). The rent-room was intended to offer high-quality garments for special occasions whereas swapping was assumed to be more regular items being exchanged often. Inspired by feedback received in the first test, this concept aims to get people interested in joining by being presented with more attractive items in the boutique-style rentroom view.

4.5 User Testing II

Four users tested the prototype, of which three from the target audience and one user with a stronger interest in climate change but less interest in fashion. Questions were how users perceived the eco-feedback, the overall concept and any needs and requirements they envisage.

All users felt that the design concept is appealing and they would use it for acquiring new fashion items. Half of the test group got confused with toggling between the swap and the rentroom and it appeared to over-complicate the design concept unnecessarily. Renting and swapping as options shall instead be offered from the item description page directly.

The user test revealed that the environmental feedback of emission reductions needs much more elaboration. Users raised the need for more information and a better visualization while relating it to known examples. Users were interested in how much is being saved when an item is swapped compared to a new purchase. Also, having a list of leading “carbon savors” that provide tips could inspire. Showing the individual impact of others and their success in terms of swaps and emissions savings can enable others to learn from high performers.

Another idea raised from testing is to allow for communication in groups with people of similar size, style or from the same region. It could be explored how to encourage personal meet-ups. The visual design was found to be appealing yet not gender neutral and seemed to rather attract women.

Overall, both initial user tests suggested that the concept appeals to users and that eco-feedback strategy does offer the potential to create engagement into this activity. However, user feedback has demonstrated that testers were interested in much more details of eco-feedback than assumed initially. The next iterations need to focus on the eco-feedback design and also leveraging the emotional values of fashion more. The latter means also changing the visual design to be more gender neutral. Field research has shown that even though currently the majority of users are women, there is large potential in also attracting men.

4.6 Design for Fashion and Eco-Feedback Exploration

This iteration focused on exploring two specific elements of the design concept: the eco-feedback which according to user feedback needs further elaboration, as well as how to design for the emotional values of fashion that were identified earlier.

It is being hypothesized that both elements will motivate users to engage with the concept. These explorations were tested only with two Interaction Designers to get peer review. The aim is to incorporate findings into a final high-fidelity prototype that will then be tested with the target audience.

Also, at this stage, a new gender-neutral mood board was developed as visible in figure 12. For simplicity, icons and elements were largely used from the IOS library. The background of the app is kept white to not distract from images. The main font is changed to a more legible, modern style. Due to time constraints, the visual language was not explored in further detail.

4.6.1 Eco-Feedback Design Concept

The environmental feedback was redesigned to provide carbon data for individual items, the community and for individual savings of a user by a leaf icon in different colors that indicate levels of engagement. The profile page and the community page were redesigned to provide more details (see figure 13). Numeric values for carbon dioxide were kept for simplicity, whereas the explanation and contextualizing of the data would be done on an extra frame.

Figure 13: Concept for community and personal eco-feedback

For presenting data on individual items, different versions were tested to understand how glanceable or hidden the data shall be (figure 14 and figure 15). The design assumption here is that when screening items, the primary

Figure 12: Mood board high-fidelity prototype

interest of users for choosing something is the item itself and not its environmental impact when being swapped.

Figure 14: Full screen modal version

The test revealed that the icon leaf shall be placed on the picture to make a relation to it and place it in focus. The feedback was to have the information slide in from the right side in the form of an overlay modal instead, which can then be swiped back. Also, the data should be in a visualization instead of text. For the community page, users requested more information, such as statistics to understand what impacts the values and which areas contribute to the data as well as seeing the result of others being in the community.

“That is where the truth comes out. This is where people get a view of the backstage of the community.”

Further development is needed on eco-feedback to make design decisions on the amount of information that is relevant to engage and create

motivation.

A more meaningful visualization for the symbol should be explored as colours did not provide clear feedback to users. By making the symbol clickable, another page could then reveal background information. Also, a suggestion was to use the leaf icon in the navigation bar in order to enhance the environmental character of the design concept.

4.6.2 Fashion Exploration Concept

This exploration aims to explore further how certain qualities of fashion can be leveraged in the concept to create an engaging experience. Values of fashion relate to identity, uniqueness and inspiration as literature showed. The latter appeared as one of the main drivers for people to engage in

swapping, as found in the field research. Exploring clothes to renew the wardrobe, experiment with new styles and getting inspired were observed to make clothes swapping an engaging. This exploration aims to expand on these qualities and explore in three different sketches how the interaction can be designed for an inspiring exploration of clothes.

The first animated sketch (figure 16) was showing clothes in a “hanger” inspired scenario where the clothes could be explored by swiping through the pictures.

Both users felt the urge to swipe from right to the left and one said

“I want to

explore it”. Both also understood

that when

double clicking on the picture itself, they could expand the it. The way to get back was for both intuitively to swipe it up right, as it had been designed for. The second idea (figure 17) resembled a drawer that can be expanded by double tapping. The clothes were then presented in a vertical carousel. The interaction with the clothes was to swipe right and left to either

Figure 16: Hanger inspired exploration