Bachelor’s thesis in Social Work Malmö högskola

15 ECTS Faculty of Health and Society

January 2014 205 06 Malmö

CLIENTS’ AND COUNSELLORS’

EXPERIENCES WITH HIV

- A UGANDAN EXAMPLE

PAULINA ERIKSDOTTER

TILDE GUSTAFSSON

FOREWORD

This study is the result of an eight week field trip to Jinja, Uganda. We would like to thank all of those who made our work possible. First of all, the volunteers at YWAM for their commitment in our study, and most of all Antony Elliot for introducing us to the different clinics and health workers. We would also like to thank all of our interview participants for sharing their stories with us. We are deeply grateful for their honesty and openness. We would never have been able to go to Uganda in the first place without the funding from SIDA, which we are very grateful for as it has been an enriched experience. Our supervisor Pernilla Ouis deserves a big thanks for her enthusiasm and positive feedback on this report. And last, but not at all the least, we would like to thank all the girls in our dormitory at the YWAM base for their emotional support and the interesting late night talks.

ABSTRACT

Eriksdotter, P. & Gustafsson, T. Client’s and counsellor’s experiences with HIV – A Ugandan example. Degree project in Social Work (bachelor) 15 ECTS points. Malmö University: Faculty of Health and Society, Department of Social Work, 2013/2014.

This study is based on a minor field study that took place during eight weeks in Jinja, Uganda. It discusses the aspect of social work in HIV counselling, with the object to describe HIV counselling and how it is conducted. The study attempts to answer questions about the nature of the interaction between the client and the counsellor from a Ugandan context, what experiences that lies between them, as well as what challenges can be identified when it comes to HIV prevention as well as HIV counselling. The study’s research strategy has a qualitative approach and the collected data is derived from semi-structural interviews with four HIV positive women who receive counselling, four counsellors and one woman who is both a client and a counsellor. We have chosen to understand our empirical findings through theories of stigma, sexual scripts and pastoral power. From our findings, we were able to conclude that there is consensus as well as discrepancies between the clients’ and the counsellors’ perceptions of their relationship, the counselling content as well as the challenges that is connected with HIV counselling. The relationship is the result of an intertwining of friendship and professionalism and there seem to be an expectation on the counsellor as a savior, which is supported by both clients and counsellors. It appears that stigma still appears in relation to HIV, but to a lesser extent than before and more so among men and children than among women. Since the introduction of ARV’s, many of our interviewed clients seem to view HIV as any other disease, which is regarded as something of a risk by many of our interviewed counsellors, as it may lead to increased risky behavior when it comes to HIV transmission. In the counselling session, the focus seems to be on behavioral change through the concept of positive living, which revolves around the idea of physical and mental well-being. Furthermore, religion has a great impact on the Ugandan society, which can be seen in the words and actions in the meeting between counsellor and client. Keywords: clients, counselling, HIV, interaction, prevention, religion, sexual behaviour change, social work, Uganda

Sammanfattning

Eriksdotter, P. & Gustafsson, T. Klienters och rådgivares erfarenheter med HIV – Ett ugandiskt exempel. Examensarbete i socialt arbete, 15 ECTS-poäng. Malmö högskola: Fakulteten för hälsa och samhälle, institutionen för socialt arbete, 2013/2014.

Uppsatsen baseras på en åtta veckor lång fältstudie i Jinja, Uganda och behandlar socialt arbete med fokus på rådgivning. Syftet är att beskriva

HIV-rådgivning och hur det utförs. Detta genom frågeställningar om interaktionens natur mellan klient och rådgivare utifrån en ugandisk kontext, vad respektive parter har för upplevelser av rådgivning samt vilka utmaningar som kan identifieras gällande såväl HIV- prevention som HIV- rådgivning. Studien är kvalitativ och den insamlade empirin består av semistrukturerade intervjuer med sammanlagt nio informanter, varav fyra är eller har varit aktiva rådgivare, fyra är HIV- positiva klienter som får rådgivning och en är aktiv både som rådgivare och som klient. Vi har valt att spegla vår empiri mot teorier om stigma, sexuella skript och pastoralmakt. Ur resultatdelen har det mellan klienter och rådgivare framträtt en bild som visar på en samstämmighet såväl som diskrepans gällande relationens natur och innehåll såväl som utmaningar kopplat till HIV- rådgivning och

preventionsarbete. Relationen bygger på vänskap såväl som professionalism och det tycks finnas en förväntan på rådgivaren som räddare som understöds av såväl klienterna som rådgivarna själva. Det framkommer att stigma fortfarande

framträder kopplat till HIV, men i mindre utsträckning än förut och i högre utsträckning bland män och barn än bland kvinnor. Sedan ARV, bromsmediciner, kommit HIV- smittade till del, talar de klienter vi intervjuat om hur HIV numera inte behöver ses som värre än vilken annan sjukdom som helst, vilket rådgivarna menar på också är en risk, då minskad respekt för sjukdomen också kan leda till ett ökat riskbeteende. I de rådgivande samtalen låg fokus på beteendeförändringar baserade på ett hälsofrämjande tänkande och handlande, så kallat positive living. Vidare framgår att religionens framträdande roll i det ugandiska samhället även tar sin plats genom ord eller handling i mötet mellan rådgivare och klient. Nyckelord: HIV, interaktion, klienter, prevention, religion, rådgivning, sexuell beteendeförändring, socialt arbete, Uganda

List of abbreviations

ABC Abstinence, Be faithful, Condoms

AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

ARV Anti-Retroviral drugs

ART Anti-Retroviral drug Therapy

CD4 Cluster of Differentiation 4

CDC US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention

FBO Faith-Based Organization

HCT HIV Counselling and Testing

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HPTN HIV Prevention Trials Network

HRW Human Rights Watch

MOH Ministry of Health

MTCT Mother to Child Transmission

NHS National Health System

NGO Non-governmental organization

PEPFAR US Presidents’ Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief PMTCT Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission

STI Sexually Transferred Infections

TASO The AIDS Support Organization

TORCH Together Restoring Community Hope

UCA Uganda Counselling Association

UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

VCT Voluntary Counselling and Testing

WHO YWAM

World Health Organization Youth With A Mission

List of content

1. Background ... 1

1.1. A medical approach to HIV ... 1

1.2. HIV on a global scale ... 2

1.3. HIV in Uganda ... 3

1.4. The research area ... 4

2. Aim and research questions ... 5

3. The counsellor in Uganda ... 5

3.1. Pre-test and post-test counselling ... 6

3.2. Counselling content ... 6

3.3. Counselling training ... 7

3.4. Counsellor quality control ... 7

4. Theoretical framework ... 8

4.1. Stigma ... 8

4.2. Sexual scripts ... 9

4.3. Pastoral power ... 10

5. Previous research ... 11

5.1. The ABC-method and positive living ... 11

5.1.1. Prevention strategies and ABC ... 11

5.1.2. PEPFAR ... 12

5.1.3. The problem with ABC... 12

5.1.4. Positive living ... 13

5.2. Challenges from a Ugandan perspective ... 13

5.2.1. Medical challenges ... 14

5.2.2. Structural challenges ... 15

5.2.3. Attitudinal challenges ... 15

5.3. Stigma and children’s vulnerability ... 16

6. Method ... 17

6.1. Participant observation ... 17

6.2. Qualitative interviewing ... 18

6.2.1. Selection and limitations ... 18

6.2.2. Presentation of the interview participants ... 19

6.3. The role of the researcher ... 19

6.4. Ethical considerations ... 20

6.5. The analytical process ... 21

7. Results ... 21

7.1. Client and counsellor interaction ... 21

7.1.2. Counsellors’ experiences and attitudes toward professionalism ... 23

7.1.3. Counselling content ... 25

7.2. Stigma ... 26

7.2.1. Children’s vulnerability ... 27

7.3. Challenges and the changing climate ... 28

7.3.1. Structural challenges ... 29

7.3.2. Attitudinal challenges ... 29

7.3.3. Counsellors’ concerns about the future ... 31

7.4. The role of religion in counselling ... 32

8. Analysis ... 33

8.1. Clients’ attitudes towards counselling ... 34

8.2. Being friends and being open ... 34

8.3. The sacrificial role of the counsellor ... 34

8.4. Managing the counsellors’ advice ... 35

8.5. The pluralization of stigma ... 36

8.6. Challenges ... 36

9. Discussion ... 38

9.1. Discussing the research method ... 38

9.2. Answering the research questions ... 39

9.3. Further research ... 41

1

1. BACKGROUND

When we first started working on this minor field study, our original wish was to get a picture of the HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) prevention work in Uganda, and what role social work plays in the fight against HIV. However, we found that this area is extremely vast and multi-layered, which makes it almost impossible to grasp within the scope of this study. We therefore chose to focus on the HIV counselling profession and the interaction between the counsellor and the client. HIV counselling is an important aspect of HIV prevention, and therefore it might be useful to take a closer look at how the counselling is conducted and which challenges may arise from the meeting between counsellors and clients. In our future profession as social workers, human interaction will be fundamental for the work we will perform. To get more knowledge and a deeper understanding of what happens in the relation between people, and more specifically between someone in the role of a social worker and someone in the role of a client, has been of great interest to us while contemplating the contents of this study. With this study, we hope to increase as well our own self-awareness as others and develop a critical thinking about professionalism and interaction.

In this chapter, we present a medical understanding of HIV as well as the historical and sociological context in which it has developed into an epidemic, both internationally and more specifically, in Uganda.

1.1. A medical approach to HIV

Although this study does not intend to deal with the pure medical aspects of HIV and AIDS, it might be helpful to have some basic understanding of the disease before exploring the social work against it, as it might help to provide the setting in which the social work is conducted.

HIV is a virus that is spread either by blood, by mother to child transmission (MTCT) or by having unprotected sex (Smittskyddsinstitutet, 2012). The virus targets on specific cells in the body that deal with the immune defense. Once the HIV has infiltrated the cells, the immune system will start to weaken. Within the first couple of weeks of infection, the person might get flu-like symptoms such as a fever and a sore throat. The body will then start fighting against the virus, keeping the infection at a minimum level and preventing any more symptoms. This might trick the person into believing that the body is healthy. However, as the virus duplicates itself into the cells, the body can never get rid of the virus. And so, without the right treatment, the body will develop AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) (Riksförbundet för HIVpositiva, 2013).

When a person develops AIDS, the immune system is weakened to such an extent that it becomes impossible for the body to fight off other infections and tumors. Eventually, the body will have no resistance left and the person will die. However, it might take up to ten years before an HIV infected person develops AIDS

(Smittskyddsinstitutet, 2012; Riksförbundet för HIVpositiva, 2013), during which time the person might have spread the virus to other people. The nature of the virus thus makes it hard to prevent it from spreading.

2

As of today, there is no way of erasing the virus from the cells once the body is infected (Smittskyddsinstitutet, 2012), although research has come a long way in finding a permanent cure. Antiretroviral drugs (ARV’s) have proven very

effective when it comes to keeping the HIV virus in the body under control, and thus allowing the infected person to live a long and often symptom free life. However, the drugs must be taken on a daily basis for the rest of the person’s life.

The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) recently conducted a study funded by the National Institutes of Health that showed that if treatment is started at an early stage, the risk of transmission can be reduced with 96 percent (Cohen et al, 2011). This study was one of the reasons why the Swedish Institute for Disease Control (SMI) changed their recommendations for when to start ARV treatment. The eligibility to taking the antiretroviral drugs is decided by the CD4 count (amount of white blood cells) in the body. According to SMI, HIV positive clients should start their treatment when their CD4 count drops below 500 cells mm3 (Smittskyddsinstitutet, 2013). In Uganda, the person may begin treatment when the person has a CD4 count lower than 350 cells mm3. If the CD4 count is still high, the person is offered counselling and treatment of opportunistic infections (Ministry of Health, 2012). Septrin is the drug most commonly used for treatment of opportunistic infections. One of the challenges Uganda faces when it comes to antiretroviral treatment, is to enable access to all areas. According to the

government’s antiretroviral treatment policy, 50 percent of all health facilities provide HIV testing and counselling, while most health facilities are lacking necessary equipment (Ministry of Health, 2012).

1.2. HIV on a global scale

The US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported on June 5th 1981 that they had recognised five cases of pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii among homosexual men in Los Angeles. The CDC first thought the disease was limited to this group, but by the end of the year the disease had been found among injecting drug users in the UK who were not homosexual. Soon other cases were reported from other countries as well (Merson et al, 2008). HIV has since the outburst in the 80’s up to recent years claimed more than 36 million lives. In 2012, around 35.3 million people were estimated living with HIV and the rates are highest in sub-Saharan Africa where 69 percent of all people diagnosed with HIV are living (WHO, 2013).

The World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Special Programme on AIDS in 1985 which subsequently came to be called the Global Programme on AIDS (GPA). After the outburst of HIV, WHO started working closely with non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) for the first time in the history of the organization (Merson et al, 2008).

WHO has been in a leading position in the global health sector in the fight against HIV and the upcoming needs the disease have given rise to. WHO cooperates with the United Nations Programme on AIDS (UNAIDS) when it comes to HIV treatment and care and HIV/tuberculosis (tuberculosis is a common opportunistic disease, which people who are HIV positive are in danger of acquiring). WHO also works together with UNICEF to eliminate MTCT of HIV.

3

WHO Member States took on a new Global Health sector strategy in 2011 for the years 2011-2015 consisting of four strategic directions to guide both WHO and countries in the work against HIV. The four directions are:

Optimize HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care outcomes. Leverage broader health outcomes through HIV responses. Build strong and sustainable health systems. Address inequalities and advance human rights. (WHO, 2012)

1.3. HIV in Uganda

Adams et al (2011) describes the HIV situation in sub-Saharan Africa in the book Africa: A Practical Guide for Global Health Workers. The book is written to provide health workers who are about to work with medical care in Africa with a deeper understanding of the African context that they are entering. The editors consist of one epidemiologist and social worker and one physician and researcher. As one of the first countries in sub-Saharan Africa to be afflicted by HIV, Uganda was hit by the epidemic in 1982. The disease soon came to be called “slim

disease” because of the way people who got it seemed to lose a lot of weight. The new disease was a mystery until 1985, when the public health officials discovered the correlation between the “slim disease” and HIV that had just recently been discovered (Adams et al, 2011).

The Uganda AIDS Control Programme was commenced in 1986 by the Ministry of Health with the goal to inform people of HIV/AIDS on how it is transmitted and how different behaviours affect its dissemination and outcome. Although the Ministry of Health had already taken action, the Ugandan government led by the new president Museveni came to the conclusion that more things had to be done, due to the way HIV affected the whole society and had developed into a national catastrophe. The president thus started speaking openly about the disease in newspapers, radio and television, which encouraged the public to have a more open discussion about the disease. In 1992, the government established the Uganda AIDS Commission with the mission to work on all levels in society to control the epidemic (Adams et al, 2011).

Alongside the governmental initiatives, independent citizens started to engage in the combat against HIV as well. In 1987, The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) was founded by Noerine Kaleeba and a group of 15 volunteers, as an initiative to emotionally support people affected by HIV and AIDS, to educate people about how it is transmitted and to fight the dissemination. During this time, HIV was associated with stigma and discrimination because of the lack of

knowledge about the disease. Since 1991, TASO is registered as an NGO and has come to be the largest governmental-funded NGO in the field providing people with free HIV testing, counselling and ARV therapy (ART). As of today, TASO has a set-up containing eleven service centres, four regional offices and one training centre in Uganda. TASO’s mission since the very beginning is “To contribute to a process of preventing HIV infection, restoring hope and improving the quality of life of persons, families and communities affected by HIV infection and disease” with the vision to see “A world without AIDS” (TASO, 2013).

In addition to TASO, there has been a rise in private health clinics as well as projects and initiatives to treat and care for people infected by HIV. The ART is

4

free across the country, but the private health clinics will sometimes charge their clients a service fee. However, the private health clinics are often funded by NGO’s in order to stay in business (Adams et al, 2011).

In 1992 the HIV prevalence in Uganda was estimated to 18.5 percent, but in the year 2000 the prevalence had fallen to 5 percent. Many believe that the decrease in prevalence is due to strong political leadership, an open approach and a response from the community, and thus Uganda is esteemed by many as a role model in the combat against HIV. Despite the success, rates have recently increased again and reached 6.7 percent in 2011 (UNAIDS, 2012).

One aspect that has come to affect the HIV prevention work in Uganda is the anti-homosexual bill from 2009 with the aim to discourage anti-homosexuality and

homosexual acts by introducing heavy penalties, including the death penalty. After massive criticism from leaders worldwide and NGO’s from different

nations, the anti-homosexual bill was adjusted and the death penalty was replaced with life imprisonment (Boyd, 2013). The bill also opens up for penalties for people that give counselling or in any other way give support to homosexuals. The bill is thus still considered controversial by many, and is met by criticism both in Uganda and in other nations (CNN, 2013).

Uganda is a country with many born again Christians, and criticism has been directed towards the American right-wing Christians and their influence in

Uganda. According to Boyd, the anti-homosexual bill needs to be seen in the light of a broader African context to get a better grasp of the sociological aspects that led to this bill. For example, she mentions the conflict between the individual and the collective and how this discourse has influenced the anti-homosexuality debate (Boyd, 2013).

When it comes to HIV counselling, this new legislation might create a gap between HIV positive homosexuals and HIV counsellors, where sexually active homosexuals living with HIV are deprived of the freedom to be open and HIV counsellors are restricted in what they are allowed to discuss with their clients.

1.4. The research area

Our research area has been limited to the city of Jinja and its vicinities, an area largely known for its location at the source of the river Nile. Jinja is currently ranked as the fifth largest city in Uganda by population, with an estimated 488 300 inhabitants by 2011 (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2011). It is located approximately 87 km east of the capital Kampala, which had almost 1.660.000 inhabitants by 2011 (ibid). Owen Falls dam and the newly built Bujagali dam provide the area with energy. Although the dams have ruined some of the scenery, Jinja is still a popular place for tourists (Uganda Tourism Board, 2013). Jinja has been an ideal research site, as it is home to one of TASO’s service centres, as well as the NGO our contact person is working with.

Our contact person in Uganda is part of the NGO Youth With A Mission

(YWAM). It is a Christian organization of volunteers working all over the world. When the organization started in the 60’s, most of the volunteers were youths, but today people of almost any age work within the organization in different

positions. The faith-based organization (FBO) was established in 1960 with the focus to serve Jesus in different ways and is today operating in over 180 countries

5

with a staff of more than 18,000 people (YWAM, 2014). YWAM has many ministries in Uganda, the one in Jinja is called TORCH (Together Restoring Community Hope). Since 1995 they have been working to help people affected by HIV and AIDS through education, health care for a low fee, counselling and prayers alongside treatment of physical problems.

During our field study, we lived at the YWAM base in Jinja and participated in some of the organization’s activities. We met many of the people involved, and most of them were willing to share their stories with us. It was also with the help of the YWAM organization that we managed to find interview participants, even though most of them were not involved with the organization.

2. AIM AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Our aim with this study is to describe how counselling of HIV positive people is conducted in Jinja and its vicinities, and how it is perceived by HIV positive clients as well as HIV counsellors. By putting the spotlight on the counselling part of the HIV treatment (which constitutes a major part of the work with HIV

prevention) it might be possible to use our study as an evaluation tool when looking at the different ways to work with HIV prevention effectively. Our main research questions are:

- What is the nature of the interaction between an HIV positive client and an HIV counsellor within a Ugandan context?

- How do they express their experiences with HIV counselling and how do those experiences differ?

- What challenges can be identified when it comes to HIV prevention in general and HIV counselling in particular?

3. THE COUNSELLOR IN UGANDA

In this chapter, we offer a brief description of the counselling profession as it appears in Uganda. The chapter includes the counsellor’s education and training, the counselling content as well as the ethical principles that apply to the

counselling profession. According to the Ministry of Health’s (MoH) (2003) Uganda national policy guidelines for HIV voluntary counselling and testing: “HIV Counselling and Testing (HCT) is the most important service in HIV/AIDS prevention and care strategies.” (Ministry of Health, 2003: p.vii) The policy guidelines describes how the counselling and testing should be conducted and what skills are required of the counsellor or health worker.

The most common type of HCT is the voluntary kind, which requires the consent of the client, as opposed to Mandatory Counselling and Testing, which is

performed on certain high-risk groups. When we refer to HCT in this study, we will use Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) as our standard.

6

3.1. Pre-test and post-test counselling

The Ugandan National Health System (NHS) includes both public and private actors. Health centres are categorized from level I to level IV, depending on the size of the area that the health centre covers (Adams et al, 2011).

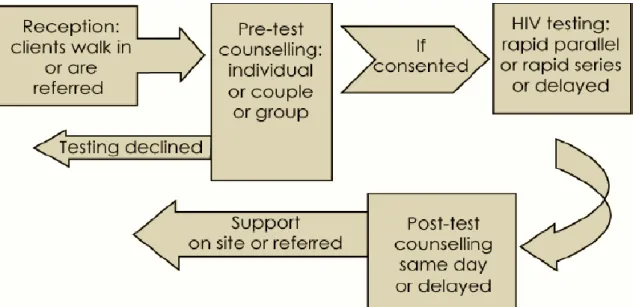

Figure 1. The process of VCT according to MoH guidelines. (Ministry of Health, 2003: 12)

As illustrated by the figure, counselling should be given individually. However, couples may choose to go together. Consent is an important part of the HCT, as the consequences of knowing one’s HIV status depend on the client’s mental readiness to get tested. When the results of the test are ready, the client should get the results together with face to face counselling. If the results show that the client is HIV positive, follow-up counselling as well as proper treatment is provided at the health facility where the test was conducted, or the client is referred to another clinic.

3.2. Counselling content

According to Chippindale and French (2001), the aim with pre-test and post-test counselling is to prevent HIV transmission as well as to give support to the clients who are infected. The pre-test counselling should therefore include such things as information about HIV and how it is transmitted, treatment options, and questions about how the client would handle a positive result (Chippindale & French, 2001). The post-test counselling focuses on the aspects of positive living, an approach which focuses on physical as well as mental well-being. This concept will be explained in further detail in chapter 5.1.4. Coping strategies as well as practical arrangements are also discussed during the post-test counselling. Most of our interview participants has informed us that the counselling is mandatory when a client is taking ARV’s, and is done at the clinic every time the client comes to collect the drugs every other month. The counselling can take from 15 minutes up to an hour, and common counselling topics during the pre- and post-test

counselling will be side-effects of the drugs, HIV transmission prevention and aspects of positive living.

7

3.3. Counselling training

According to the MoH guidelines, it is important for HCT service providers to have an adequate educational background, and training should be conducted by approved institutions.

There are five government-sponsored universities and 21 private universities in Uganda (Adams et al, 2011), a number of which offer guidance and counsellor training. In addition, TASO has its own training centre where medical courses as well as psychosocial/community courses are provided. The goal is to improve the competencies of HIV/AIDS service providers. Some of the courses offered in counselling at TASO are: HIV/AIDS counselling, child counselling, couples HIV counselling and home-based HIV counselling and testing (TASO, 2013).

According to the MoH guidelines, all non-medical counsellors must be registered (Ministry of Health, 2003). The counsellors in Uganda are also encouraged to become members of the Uganda Counselling Association (UCA), which acts as an umbrella organization that brings together counsellors and counselling

institutions. UCA was founded in 2002, with the mission to promote: “ethical and competent counselling through regulating the practice, providing a forum for networking and ensuring professional development of the counsellors and counselling.” (UCA, 2012)

UCA offers its own courses, e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy training. It is also the host of the Annual National Counsellors Conference, which has been held for the last eight years (UCA, 2012).

3.4. Counsellor quality control

MoH defines quality as: “doing the right thing right, right away” (Ministry of Health, 2003: 25). In order to attain good counselling standards, continuous monitoring and evaluation is required. MoH has developed a list of counselling standards that each counsellor should follow in order to provide quality service to the client. The list states that the counsellor should:

Be able to adjust to and respect the social, cultural, religious, educational differences and developmental stage of the client.

Not impose their own view or opinions but respect and follow the client’s agenda or priorities; however, counsellors should use their discretion to help the client consider the implications of their issues and concerns so that the client can make decisions that are appropriate for their situation.

Maintain positive attitudes towards all clients at all times.

Use effective communication skills to help clients make appropriate decisions relevant to the prevailing situation.

Provide proper guidance for the client to face realistic options and act accordingly.

(Ministry of Health, 2003: 25) In addition to these quality standards, MoH also states that ethical values should be maintained by keeping a professional code of conduct, with focus on the relationship between a service provider and the client. It is also important to offer personal and professional support to counsellors, to prevent emotional stress and

8

to promote a learning process between counsellors. It is also advised that counsellors meet with their supervisors as well as with senior counsellors regularly (Ministry of Health, 2003).

The National Department of Health in South Africa has recently published a similar policy guideline. Their core ethical principles include confidentiality, privacy, informed consent and non-discrimination of HIV positive clients. They also argue the importance of HCT that is appropriate to the client’s circumstances, and is thus sensitive to the client’s culture, sex, age, language, etc. Furthermore, they state that counselling must be conducted by trained and supervised

counsellors or health workers (National Department of Health, 2010). There are similarities between the South African HCT policies from 2010 and the Ugandan policies from 2003 that suggest that the approach to HCT on a governmental level is somewhat universal across time and nations.

One aspect where the South African policy guideline differs from the Ugandan policy guideline is on the focus on HCT for children. The South African policy guidelines have a section which focuses solely on children and how to manage children’s testing and counselling correctly. This focus on children is lacking in the Ugandan guidelines, which is not as thorough as its South African counterpart. It is not to say if this is due to budget, recent updates, or national differences in managing the epidemic.

4. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

For this study, we have chosen to focus on three theories to grasp an

understanding of our research findings. The theories selected are stigma, sexual scripts and pastoral power. We believe that these theories will be useful in analysing and theorizing our work, and that they will complement each other.

4.1. Stigma

During our research, we came across the concept of ‘stigma’. Stigma and stigmatization of people is not the main focus of our analysis. Even so, when it comes to HIV and AIDS-related issues, the existence of stigma cannot be overlooked.

According to the Oxford Dictionaries, stigma is: “a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality or person” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2013). The word originates from the Greek word, meaning: “a mark made from a pointed instrument, a dot” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2013).

For this study, we have chosen to base our understanding of the concept of stigma on Goffman’s definition. Goffman (2011) describes stigma as a form of social branding of someone who does not conform to the norms of the society, either because of physical attributes, personality traits or tribal attributes. According to Goffman, a person living with stigma often has to develop coping strategies to fit into society. If the attribute causing the stigma is not visible, the person might choose to hide it, which we can see has been the case of many people living with HIV. For people with a visible attribute causing stigma, hiding is not a choice. Instead, they have to try to solve socially awkward situations, perhaps by joking

9

about their attribute (Goffman, 2011). What attributes that cause stigma and how the stigma is manifested, might vary in different societies or social settings.

4.2. Sexual scripts

During the process of searching for literature about HIV prevention and the ABC method specifically, we came to the understanding that sexual behaviour change was to become a major part of our study. Therefore, we wanted to use a theory that would explain sexual behaviour in relation to interaction. As such, the sexual script theory seemed to be the obvious choice.

Sexual script theory was developed by Simon and Gagnon (1984) and has a dramaturgical approach to describing the sexual norms and expectations at the different levels of society. At a basic level, it provides a theoretical metaphor which tells us when we can have sex, with whom, how we can have sex, and why (Pedersen, 2005). The theory suggests that people are prone to follow certain scripts that have been determined by the social context in which they live. When someone deviates from the script, it creates a discrepancy between reality and expectation, which can cause tensions.

The three levels of scripts described by Simon and Gagnon are the intrapsychic scripting, the interpersonal scripts and the cultural scenarios. Each level deals with norms and expectations that are more or less distinct.

On the intrapsychic level of scripting we find the individual’s own wishes and fantasies as well as his or her expectations on these. Simon and Gagnon states that: “individual desires are linked to social meanings.” (Simon & Gagnon, 1984: 53) The norms and values of the individual are highly influenced by the cultural and social context surrounding the person. Therefore, if the person would start to feel sexual desires that are not accepted by his or her own values, this would create a tension within the person itself and cause an inner emotional struggle. An example of this would be if the person feels sexually attracted to an adolescent, but still believes that such an attraction is wrong.

Interpersonal scripts deal with the expectations that we have on each other. The individual is no longer solely an ‘actor’, but is also a scriptwriter, as he or she is: “shaping the materials of relevant cultural scenarios into scripts for behaviour in particular contexts.” (ibid) This includes the norms within a relationship, which can be articulated as well as tacit. For example, if someone within a relationship starts having sexual activities with others, and his or her partner has expectations on that person to be monogamous, then that is likely to create tension within the relationship.

According to Simon and Gagnon: “cultural scenarios are the instructional guides that exist on the level of collective life. All institutions and institutionalized arrangements can be seen as systems of signs and symbols through which the requirements and the practice of specific rules are given.” (ibid) As such, expectations within the cultural scenarios can be either articulated or tacit. Both spoken and unspoken expectations constitute the cultural sexual norms in society. The articulated expectations can be seen as a country’s legislation. What

expectations are written and what expectations are tacit differ among different societies. For example, in Sweden, a person who has HIV (or any other disease that is considered a danger to the public) is obliged to inform anyone who comes

10

in risky contact with him or her about the disease, according to paragraph 2, chapter 2 in the Communicable Diseases Act (Smittskyddslag 2004:168). Prostitution is another well-debated phenomenon in Sweden as well as in other countries. It is not illegal to sell sex in Sweden, even though it might go against the norms. However, it is illegal to buy sex.

If someone engages in sexual behaviour that is illegal, it will cause tension in the sense that the person will face a penalty. If someone engages in a sexual activity that is not illegal, but still goes against the norm, it might cause tension in other ways, e.g. public bullying or exclusion of the person from society, which can cause stigma for the person concerned.

When reality and expectation diverge from each other, it creates tension. The theory that our sexuality is managed by scripts on different levels is highly useful when it comes to understanding the way we manage our own sexuality and how we affect the sexuality of others.

4.3. Pastoral power

It was not until we entered the Ugandan society that we truly became aware of the impact that religion has on the Ugandan people. As soon as we acknowledged this, we felt that Foucault’s theory of pastoral power would be the most relevant to our study. As Foucault states, the pastoral power has permeated into the modern state, and as future social workers, working within the system of the modern state, it is important for us to explore this phenomenon and create awareness on the subject.

The concept of pastoral power stems from Christianity and its biblical metaphors of the shepherd and his flock. The old Christian tradition puts the pastor in a power relation to his congregation, from where he leads his people to a better life. In order to do that, the pastor must become part of every church member’s life and learn about their intimate thoughts. Only then can he fulfil his role as saviour. Both the pastorate and the congregation regarded this pastoral power as helpful and therefore entered this power relation willingly (Järvinen, 2002).

The pastoral power is not only commanding by its nature but also sacrificing. If necessary, the shepherd has to be prepared to sacrifice his life for the salvation of the flock. The pastoral power thus differs from the royal power in the way that: “the royal power demands a sacrifice from its subjects to save the throne.” (Foucault, 1982: 783)

Foucault differentiates between two aspects of the pastoral power: the

ecclesiastical institutionalization and its function. He meant that even though the power of the church has ceased, the function of it has survived and is now taking place in the “modern state”. He suggests that we can see the modern state as: “a modern matrix of individualization or a new form of pastoral power.” (ibid)

The pastoral power subsequently developed into community caring and

controlling institutions as opposed to a controlling church. Characteristic for the modern day pastoral power is its view on salvation; instead of focusing on the after-life, it is trying to gain a good life here and now, including aspects of health, safety and security. Pastoral power thus encompasses professions and institutions such as physicians, nurses and social workers. Their task is to help and control the

11

individual, by focusing on his or her shortcomings and struggles in life. Just as the pastor is using his power to help his congregation, these modern institutions appear to be helpful for the individual, which is why the client often enters the relationship willingly (Järvinen, 2002).

5. PREVIOUS RESEARCH

In this chapter, we will present previous studies of HIV and HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa, with a focus on Uganda in particular. We will describe the ABC approach and how it has affected the HIV prevention work, as well as some of the challenges that are connected with HIV.

5.1. The ABC-method and positive living

Since the outbreak of HIV in the early 80’s, different prevention strategies and their advantages and disadvantages have been discussed. Over time the prevention strategies have been influenced as well by religious, political, financial as public opinions and there is a wide array of research studies focusing on the

consequences of different prevention strategies, as well as how Uganda has managed the epidemic during the last three decades.

5.1.1. Prevention strategies and ABC

Since the HIV prevalence in Uganda decreased in the 90’s, a large number of studies have been done to find out the reasons for the decline. The debate has in many ways become polarised. Some argue that the decline is caused by behaviour changes among the Ugandan population, such as people starting to have fewer sexual partners. The change in behavioural patterns could be the result of intensive campaigning by the government and different NGO’s promoting the message of “zero grazing” which implies that a person should have no more than one partner. Others argue that the reduction was made possible due to a promotion of condom use together with changes at a structural level when it comes to

poverty, gender, violence and conflicts. The conflict has come to be called the ABC debate, where A stands for abstinence, B for being faithful and C for condom use.

According to Green et al (2006) there is a complex connection between behaviour changes and the decrease in HIV prevalence. Their report suggests that the largest change in HIV prevalence occurred in the late 80’s and early 90’s, and that there is a difference between Uganda and many other African countries that was struck hard by HIV, such as South Africa, Botswana and Malawi, where the situation consists of a complex set of epidemiological, political and socio- cultural factors (Green et al, 2006).

In the earlier promoted strategies, condom use was not seen as one of the primal prevention strategies. President Museveni as well as religious leaders were against condom promotion, and so the government at first chose not to recommend

condom use as a prevention strategy. Later on the governmental standpoint came to soften and their standpoint came to be that HIV can be transmitted even though condom is used. According to Green et al. (2006), earlier research has shown that even though condom use has increased over time, condom use among high risk

12

groups is not higher than in other African countries in the region (Green et al, 2006).

5.1.2. PEPFAR

When the HIV epidemic in the 2000’s began to spread outside of sub-Saharan Africa, the political interest in HIV increased to a global scale. The U.S.

President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS (PEPFAR) was founded in 2003, primarily to help people affected by HIV and AIDS, although it extends to helping people suffering from other diseases as well. PEPFAR mainly targets on women, new-borns and children and supports other countries to improve the health of their citizens. PEPFAR aims to have a comprehensive and multi-sectorial approach and has adopted the ABC method to their program as their main strategy to combat the HIV / AIDS epidemic (PEPFAR, 2013).

PEPFAR has since the very beginning received positive as well as negative criticism; positive criticism for the large amount of funding spent on ARV’s for HIV positive people in poor countries, and negative criticism for the way in which they implement the ABC method and through funding influence countries to work according to their agenda. At first, PEPFAR was reluctant to promote the use of condoms to young people, and would only do so to high-risk groups. According to directives from 2003, one third of PEPFAR funds were therefore set to abstinence and fidelity programmes. After being massively criticized, and after a change in presidency, PEPFAR changed their directives in 2008, and opened up for funding to a broader range of projects. Even though they changed their directives on how the funding should be spent, countries had to report how they used the money if less than half the amount was spent on projects supporting abstinence and faithfulness (Hayden, 2009).

5.1.3. The problem with ABC

One of the organizations criticizing PEPFAR for focusing too much on the A and B part of the ABC strategy is Human Rights Watch (HRW). According to HRW, the ABC approach has become more of an A and B approach, since different funders from countries such as the U.S started to share their mission about an ABC method with a strong A and B but a much weaker and sometimes absent C. HRW’s criticism lies in that the abstinence-only programs refuse young people to get information about how to protect themselves from HIV in other ways than through abstaining from sex until marriage. According to HRW, Uganda started implementing teaching about abstinence more extensively when conservative funders began supporting abstinence-focused programs in the early 2000. According to HRW, the abstinence-only approach undermines HIV prevention rather than complement it (Human Rights Watch, 2005).

According to Cohen (2004), the relationship between HIV and a person’s individual sexual behaviour is too complex to be solved by solely one approach, such as the ABC approach. There is no specific research showing that it was an abstinence-only behaviour that caused the decrease in the prevalence of HIV between 1988 and 1995. Cohen mentions for example that the risk to become infected by HIV is higher for a person with other sexual transmitted diseases and studies have shown that circumcision seems to lower the risk of getting infected for men. Furthermore, aspects such as how many sexual relations the individual has, how often, what kind of sexual activities are practiced and to what extent and how condoms are being used as well as the partners level of infection have an

13

influence when it comes to HIV transmission. It is a fact that the HIV rates in Uganda decreased during the 90’s, while behaviour changes did occur in the sense that people started having fewer sex partners. However, there is no evidence that suggests that having fewer sex partners is or should be the most important behaviour change to reduce the transmission of HIV. Meanwhile, Uganda has done more than simply trying to implement the ABC approach among the population. The government together with different NGO’s and religious

organizations have worked actively to reduce stigma, started talking openly about sexual behaviours, involving people who are HIV-positive in public education, advocating HIV-testing as well as counselling for both individuals and couples together and also improving women’s status in society. Any or all of these incentives may have contributed to how Uganda managed to decrease the spread of HIV during the 90’s (Cohen, 2004).

5.1.4. Positive living

Positive living is a lifestyle approach originating from TASO and then spread to other organizations and organs of society. Positive living is primarily taught to people affected by HIV to help them cope with their disease and stay healthy longer. The lifestyle is about making positive choices that will promote good health both mentally and physically and postpone the progression of the disease. Common advice connected to positive living are: keep yourself informed about your health, take your prescribed medication, work as your energy allows, avoid stress, maintain good nutrition, prevent infections, exercise and seek medical care regularly. Positive living also includes aspects of how to protect others from getting infected, e.g. through condom use and Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT). Even people who are HIV negative get

encouraged to follow this lifestyle by doing the HIV test regularly and by living a responsible life avoiding alcoholism and drug abuse, using condom and avoiding having multiple sexual partners. Moreover they are also encouraged to embrace medical safety procedures such as safe medical circumcision and pre- and post-prophylaxis. On a structural level the philosophy of positive living is about making society more open and supportive towards people with HIV, but also to encourage people who are HIV negative to help preventing further transmission. To make this happen, TASO’s vision is that all levels of society will embrace this way of living:

Living Positively with HIV is about understanding the implications of HIV infection and undertaking positive choices to prevent HIV infection and coping with the challenges associated with it. Living Positively with HIV also entails adopting strategies that enhance the quality of life and wellbeing. Living positively applies to HIV positive and HIV negative people, families, communities as well as institutions for better health and socio-economic outcomes. (TASO, 2013)

5.2. Challenges from a Ugandan perspective

There is no doubt that fighting against the HIV epidemic is a difficult and complex task. A number of challenges when it comes to HIV prevention have been identified by governments, NGO’s and researchers. Some of those

challenges will be presented in this chapter. We have tried to keep the focus on Uganda, although many other countries seem to face similar challenges.

14

The research made in this area is vast, and covers several decades, why it can be hard to sum up all the various research findings in this report. However, we believe that the selection of research presented below covers some of the most protruding issues. The reader should know that we have been generous in our understanding of the term ‘challenge’, and thus have included terms like issues or problems in the concept of challenges. To make the findings more manageable, we have divided them into three categories: medical challenges, structural challenges and attitudinal challenges.

5.2.1. Medical challenges

From a medical viewpoint, some of the challenges that have been identified by the Ministry of Health include side effects of the ARV’s, drug resistance and

problems with monitoring the drug and treatment process (Ministry of Health, 2012). Adams et al (2011) also mention drug resistance as a serious issue, and add opportunistic infections to the list (Adams et al, 2011). However, a study in South Africa has recently concluded that transmitted drug resistance among newly infected remains low, although thorough drug treatment monitoring is

recommended (Manasa et al, 2012). Negative consequences aside, treatment with ARV’s has generally been considered the way forward when it comes to HIV prevention in recent years. Another study from South Africa suggests that in societies where ARV treatment is used to a great extent, there has been a decline in risk of HIV acquisition (Tanser et al, 2013). The results of this study has prompted the UNAIDS to urge nations to expand their drug treatment (UNAIDS, 2012).

Another medical challenge is the MTCT of HIV. Onyango states that: “In Africa […] about 25 – 35 % of HIV-infected mothers pass on the disease to their infants.” (Onyango, 2006: 2) She suggests that the reasons for this high rate can be found in a combination of influential factors, e.g. prolonged breastfeeding, high birth rates and a lack of MTCT prevention interventions. The WHO’s guidelines for ARV for pregnant women states that most children that acquire HIV get it through MTCT. The risk of getting infected is 15 – 45 percent without intervention, depending on if the child is breastfeeding or not. ARV treatment is known to reduce the risk to below 2 percent (WHO, 2004). However, WHO admits in the report that research is lacking when it comes to the effects of the toxicity of the ARV’s on the mother as well as the child. Foster et al (2009) has reviewed the ARV treatment available for pregnant women and they seem to agree with WHO as they state that: “While short-term toxicity data are

encouraging, long-term follow-up of exposed mothers and infants is required.” (Foster et al, 2009: 397)

The biological differences between the sexes can also be categorized as a medical challenge. Some research suggests that women are more physiologically

vulnerable to becoming infected by HIV than men, due to different factors. For example, women have a large mucosal surface more vulnerable than that of men. Because of this, women also run a greater risk than men of getting other sexually transferred infections (STIs), which in turn increases the risk of getting infected by HIV (Ackermann & De Klerk, 2002). The risk of HIV transmission from male to female is two to four times higher than from female to male. Furthermore, women are more or less vulnerable depending on where they are in their

menstrual cycle. Pregnant women run a higher risk of getting infected than other women because of physiological changes (Ostrach & Merrill, 2012).

15 5.2.2. Structural challenges

Adams et al (2011) state that:

In any part of the world, health issues should be understood not only from a medical viewpoint, but with an understanding of other contributing factors such as education, living conditions, gender issues, and religious and ethnic acceptance. (Adams et al, 2011: 12)

We have chosen to categorize these contributing factors as structural challenges, as they have an effect on the HIV prevention work on a higher level.

When it comes to structural challenges, we find a number of different issues, ranging from infrastructure to gender inequality. Adams et al (2011) write from a broader health perspective when they mention medical infrastructure, lack of clean water, unreliable power supplies, and limited funding as some of the greatest challenges in Africa. Limited funding is connected to understaffed and underequipped health facilities, which is also mentioned. The challenge of understaffed health facilities as well as the lack of medical infrastructure has also been a high priority issue for the Ministry of Health.

As Adams et al mention, gender issues can be a contributing factor to the

difficulties of preventing HIV, and that has been the focus of study for Schatz and Williams (2012) as well as Ouis (2012). Schatz and Williams have studied gender inequality in Africa, and they state that:

Understanding gender in Africa is essential to creating policy and designing interventions to address key reproductive-health issues such as HIV/AIDS and maternal mortality that are particularly pressing for the continent and are strongly related to gender inequality. (Schatz & Williams, 2012: 811)

They suggest that gender inequality is a major underlying reason to reproductive health problems in Africa. Ouis offers a more detailed explanation of the gender inequality issue when she points at research that states that 40 percent of the women in South Africa have had their first sexual experience forced upon them. She also mentions that married women may have bigger difficulties negotiating condom use with their partners compared to unmarried women (Ouis, 2012).

5.2.3. Attitudinal challenges

The sexual attitudes and behaviour of the population has a major influence when it comes to HIV prevention, as sexual interaction is one of the ways of

transmission. As such, changing attitudes and behaviour is identified by numerous researchers and institutions as a major challenge when it comes to HIV

prevention.

According to the Ministry of Health, the success of the HIV drug treatment has made people living with HIV feeling freer to engage in risky sexual behaviour (Ministry of Health, 2012). As a proof of this, Beyeza-Kashesya et al. (2011) shows with their research study on condom use that the usage of condoms was less common among HIV-positive youths (34 percent) than HIV-negative youths (59 percent) (Beyeza-Kashesya et al, 2011).

16

Larsson et al (2010) discuss men’s reluctance to go for couple testing. Their study of men’s perception of couple testing shows that the men in the study found it unnecessary to go for testing when they were symptom-free. They felt that getting tested would raise conflicts in the relationship, and that the health workers were rude. This in combination with a stigmatizing setting, made the HIV couple testing unappealing for the men.

A study by Parikh (2007) focuses on the messages protruding in media against infidelity and how it has had an opposite effect on the targeted group. Parikh writes: “An unexpected finding of our research was that HIV prevention discourses have increased the moral stigma of extramarital sex, inadvertently heightening people’s motivation for sexual secrecy and personal denial that an extramarital liaison puts one at risk for HIV.” (Parikh, 2007: 1202) Parikh states that the discourse towards infidelity has created a social morality which: “depicts married people seduced by potential lovers as weak, immoral and backward.” (ibid). The change in attitude to a more secretive sex life, further complicates HIV prevention.

Dr. Ezekiel Kalipeni, who has a Ph.D. in geography and specialises in population and medical resource issues, writes in his book HIV and AIDS in Africa: beyond epidemiology (2004) that: “underlying many studies is the assumption that western-centric forms of marital-based sexual conduct either do or should pertain in differing regions of sub-Saharan Africa.” (Kalipeni, 2004: 4) This is a direct criticism of the behavioural change approach that is currently the main focus in the HIV prevention work. He continues by stating that medical solutions so far has failed to conquer the epidemic, and that it is necessary to study the different ways in which HIV/AIDS are viewed and experienced in each community in order to understand why the behavioural change approach has proven inadequate.

5.3. Stigma and children’s vulnerability

Adams et al (2011) state that: “Like other parts of the world, many African

societies stigmatize those infected with HIV/AIDS, ostracizing them because their disease is considered disgraceful.” (Adams et al, 2011: 12) Adams also mentions that due to the fear of stigma, many people hesitate to get tested, which

contributes to the challenge of preventing HIV transmissions.

In a publication of successful UNAIDS programs from 2005, it is reported that: “HIV-related stigma and discrimination continue to be manifest in every country and region of the world, creating major barriers to preventing further infection, alleviating impact and providing adequate care, support and treatment.”

(UNAIDS, 2005: 4) The report goes on to discuss the reasons behind stigma and discrimination, what the consequences might be, and possible solutions.

When it comes to Uganda in particular, the UNAIDS report also takes a new perspective on stigma, as it focuses on the children. According to the report, the parents’ attitudes about their disease can have a negative impact on their children. If the parents are secretive about their disease, or fail to make arrangements for the future, it increases children’s vulnerability. UNAIDS therefore highlights the great importance of succession planning and ongoing support for the children that are affected.

17

Rwemisisi et al (2008) conducted a small study on parental attitudes toward HIV in Uganda, and found that half of their interviewees (five out of ten) kept their disease a secret from their children, thus preventing their children from getting tested as well. None of the parents chose to test their children as long as the children were symptom-free, as they feared to traumatize the children. The study also showed a lack in policy guidelines and that many of the counsellors

improvised and gave inconsistent advice when it came to unveiling the parent’s disease to the children.

6. METHOD

The research strategy chosen for this report has been the qualitative approach. According to Bryman, qualitative research studies features: 1) an inductive approach to the relation between theory and research, 2) an epistemological position derived from the attempt to grasp the social world we live in by exploring people’s perceptions of it, and 3) an ontological approach where social attributes are a result of people’s interaction with each other (Bryman, 2012). As such, we find this strategy to be very suitable to the object of our study. Because the qualitative research study is tainted by the writers’ own perception of reality, it can never offer an objective understanding of the studied phenomena

(Denscombe, 1998).

The methods that have been used in this study are mainly participant observation and interviewing. Both are common to the qualitative research strategy. In the following chapters we will describe our use of those methods and the

consequences they might lead to. We will then present the ethical considerations that we have made before conducting the study and have a critical discussion of our roles as researchers. Finally, we will describe the analytical process that we have undergone with our data collection.

6.1. Participant observation

Our observations were brief but important as we gained a basic understanding of the nature of HIV counselling. It allowed us to get an inside-look at pre-test counselling and to experience the feeling of being tested for HIV first-hand. Our first HIV-test was conducted at a small village clinic and our second test was conducted at one of TASOs health clinics. The experiences we gained from these tests has been useful when analysing our collected data. Bryman describes the advantage of participant observation as being able to see the world through someone else’s eyes. By gaining first-hand knowledge of HIV counselling, we were able to understand implicit meanings during our interviews.

The disadvantage with participant observation is that it can create preconception about the people or community that is the object of the study. Our own

experiences might not be the same as someone else’s; it is important that we as researchers try to remain as neutral as possible and not to let our own experiences influence how we view the participants. Moreover, observations alone cannot explain the reasons behind the participants’ choices or behaviour. A combination of field observations and interviewing thus gives the researcher the richest data collection.

18

6.2. Qualitative interviewing

Our choice to use qualitative interviewing as our research method is based on the aim of the study, which focuses on HIV counselling and how it is perceived by clients as well as counsellors. The method’s strongest merit as well as greatest challenge is that it leaves open to the interview participants to steer the

conversation in different directions and to immerse themselves in certain topics (Denscombe, 1998). This felt as a suitable choice, because of the nature of our topic. When talking about HIV, it is of great value to let the interviewee choose the direction in order for us to learn how they really think and feel about the disease.

When working with the qualitative research approach, it is crucial to reflect critically on the study’s credibility, confirmability and transferability. That is to say, do the findings from the study say something that can be transferred to other contexts? It is important to make these kinds of revisions of a study, to make sure that the results from the study are trustworthy (Jacobsen, 2010). As we earlier mentioned, since the qualitative study is a subjective interpretation made by the researcher, it is impossible to ensure the trustworthiness of such a study.

However, the above-mentioned criteria can be used as tools for the researchers to critically review their own role in the study. In this study, we have tried to let our respondents speak for themselves by giving their statements a lot of space in the result chapter. This is in order to keep misunderstandings and false conclusions at bay. We have also tried to avoid quotations where we are not sure that we have understood the respondent correctly. When such a mishearing occurs in a

quotation, we have eliminated it from the quotation, by marking it with […]. We also have excluded quotations where we have had different conclusions of what the respondent has intended with his or her statement. When it comes to

transferability, it is not clear if others would come to the same conclusions as we have, as this is a qualitative study. However, with this study we hope to inspire others to view the interaction between people within social work and its contexts in new ways.

6.2.1. Selection and limitations

HIV and AIDS prevention is a huge area of research with medical as well as social aspects. As the scope of this study is limited, we have chosen to focus solely on HIV counselling.

As our focus lie on the interaction between the client and the counsellor, we will not include the medical aspects of HIV prevention in our analysis. Nor will we include the challenges that the debate of homosexuality has given rise to, although we find this field relevant for further research. We also acknowledge the

importance of economic factors when it comes to HIV prevention, such as poverty and lack of funding, although the limitations of this study will not allow us to dig further into this area.

The study was conducted during eight weeks in and around the city of Jinja, Uganda. The study includes nine interviews and two first-hand observations of pre-test counselling. This study is based on findings from a geographically limited research area in Uganda and is not necessarily conveyable to a Western context or even a national Ugandan context.

19

Our contact person from YWAM assisted us in finding our first interviewees, and from them we gathered more interviewees. In that sense, we have used

convenience selection as well as snowballing described by Bryman when selecting interview participants (Bryman, 2012). When it came to finding HIV positive people, we asked our contact person to give our letter of information and the interview guide to people he knew had HIV, before setting up a meeting. In that way, we avoided to be introduced to anyone who did not wish for us to know their HIV status. All our interviewees have been above the age of 30, which suited our wish to interview adults. Among the counsellors, we have interviewed both men and women, but among the clients, we only interviewed women. This is not something we decided upon, but was a result of the fact that our contacts only introduced us to women. All of the interviewed clients were more or less open about their HIV status. The fact that all of our informants among the HIV positive clients were women has its advantages as well as disadvantages. The disadvantage would be that we did not get a male perspective on the issue; however, there might be an advantage in the way that women might find it easier to relate to us as female researchers and thus be able to talk to us on sensitive topics.

6.2.2. Presentation of the interview participants

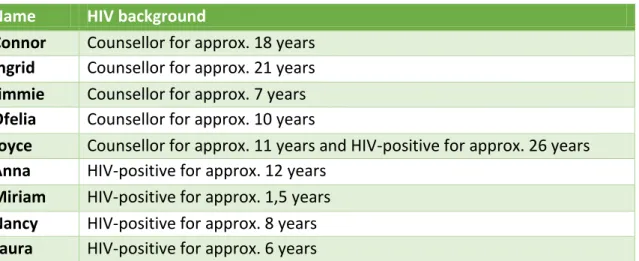

The counsellors and clients that participated in this study are presented in the table below. Due to the principle of confidentiality, we will only present their relation to HIV and HIV counselling. All the names are fictitious.

Table 1. Presentation of the interview participants.

The conditions of the interview setting varied somewhat from person to person. Miriam for example, did not feel comfortable with expressing herself in English, and so we got help from another woman to translate, which might have had an effect on the outcome of the interview. This can be noticed in the quotes by Miriam, which is written in third person. What is more, Anna had her son in her lap while speaking to us. Although we do not believe he understood much of the conversation, as it was held in English, he might have influenced the way she answered. At yet two other occasions, during Ofelias and Connors interviews, we were interrupted by people. It is important to be aware of these impediments, as they might have affected the interviewing results.

6.3. The role of the researcher

According to Brinkman and Kvale (2009) the meeting between interviewers and respondents tend to have an uneven balance of power where the interviewer is in a

Name HIV background

Connor Counsellor for approx. 18 years

Ingrid Counsellor for approx. 21 years

Jimmie Counsellor for approx. 7 years

Ofelia Counsellor for approx. 10 years

Joyce Counsellor for approx. 11 years and HIV-positive for approx. 26 years

Anna HIV-positive for approx. 12 years

Miriam HIV-positive for approx. 1,5 years

Nancy HIV-positive for approx. 8 years

20

superior position to the respondent. This is something we have taken under consideration during our interviews and our concerns about it also revealed some of our own prejudices. We discovered more than once that our own thoughts about what might be perceived as uncomfortable and stigmatizing topics were not shared by our respondents.

When it comes to the result and analysis of a qualitative study, Denscombe (1998) states that there is always a risk that the words of the respondents are taken out of their context and therefore get a different meaning. During the process of coding we have tried to do our respondents justice, but still there remains a risk of misunderstandings. Moreover, our role as researchers is to interpret statements, which might lead our conclusions in directions our respondents did not intend. We are fully aware that the interpretation we have made with the help of our chosen theories are our own subjective understanding of the studied phenomena and that it will be more or less tainted by our own cultural context and

conceptions of life. However, we are grateful for the contemplations of our own cultural understanding that this has given rise to.

6.4. Ethical considerations

Since we are conducting a study entailing delicate information, ethical considerations is of great importance. According to the Swedish Research Council, there are some basic ethical principles to follow: the principle of

informed consent, the principle of confidentiality and the principle of utilization. Informed consent must be obtained from those included in the study (Trost, 2010). All of our nine respondents have been given a letter of information (Appendix 1) about the study and its objective before conducting any interviews. They also had the possibility to see the interview guide (Appendix 2) before the interview and we told them that more questions might be added. All of our respondents either signed an informed consent or gave us verbal consent before participating in the study.

The principle of confidentiality suggests that the respondent’s identity must not be disclosed in the study (Trost, 2010). In our study, we have chosen to give our respondents other names than their real ones and not reveal any detailed information of their background, such as their age or their workplace to ensure that they remain anonymous.

The principle of utilization deals with the collected empirical data and how it may be used. The empirical data may only be used for purposes of research (Trost, 2010), which we informed the respondents about. After asking our respondents for permission, we chose to record all of the interviews so that we could transcribe them and then delete them after finishing the study.

An application to the Ethics Committee at Malmö University was approved 2013-09 – 19 (Dnr HS60-2013/929). Even though we had to change our aim of study and research questions, our main research strategy (to interview people from the local community) remained the same. We thus carried out the recommendations that we received with the original ethical approval.