SWEDISH DENT AL JOURN AL, SUPPLEMENT 235, 20 1 4. DOCT OR AL DISSERT A TION IN ODONT OL OG Y LEIF LEISNERT MALMÖ UNIVERSIT MALMÖ UNIVERSITY

LEIF LEISNERT

SELF-DIRECTED LEARNING,

TEAMWORK, HOLISTIC VIEW

AND ORAL HEALTH

isbn 978-91-7104-605-5 (print) isbn 978-91-7104-606-2 (pdf) issn 0348-6672 SELF -DIRECTED LEARNIN G, TEAMW ORK, HOLIS TIC VIEW AND OR AL HEAL TH

S E L F - D I R E C T E D L E A R N I N G , T E A M W O R K , H O L I S T I C V I E W A N D O R A L H E A L T H

Swedish Dental Journal, Supplement 235, 2014

© Leif Leisnert 2014 ISBN 978-91-7104-605-5(print) ISBN 978-91-7104-606-2(pdf) ISSN 0348-6672 Holmbergs, Malmö 2014LEIF LEISNERT

SELF-DIRECTED LEARNING,

TEAMWORK, HOLISTIC

VIEW AND ORAL HEALTH

Malmö University, 2014

Faculty of Odontology

Institution of Oral Public Health

This publication is also available at: http://dspace.mah.se/handle/2043/17710

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ... 9 ABSTRACT ... 10 POPULÄRVETENSKAPLIG SAMMANFATTNING ... 13 ABBREVIATIONS ... 19 INTRODUCTION ... 20 AIMS ... 24MATERIALS AND METHODS ... 26

RESULTS ... 37 DISCUSSION ... 44 CONCLUSIONS ... 60 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 62 REFERENCES ... 63 APPENDIX ... 67 Study I ...69 Study II ...77 Study III ...89 Study IV ...101 Questionnaire Study IV ...131

PREFACE

This thesis is based on the following papers:

Study I

Leisnert L, Mattheos N. The interactive examination in a compre hensive oral care clinic: a threeyear follow up of students’ self assessment ability. Med Teach. 2006 Sep;28(6):5448.

Study II

Leisnert L, Karlsson M, Franklin I, Lindh L, Wretlind K. Improving teamwork between students from two professional programs in dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012 feb;16(1):1726. doi: 10,1111/j.1600–0579.2011.00702.x. Epub 2011 Sep 27.

Study III

Leisnert L, Hallström H, Knutsson K. What findings do clinicians use to diagnose chronic periodontitis? Swed Dent J. 2008;32(3):11523.

Study IV

Leisnert L, Axtelius B, Wennerberg A. A comparison of proposals for diagnosis and treatment of periodontal conditions by dentists, dental hygienists and undergraduate students. An analysis based on the recommendations from the Swedish National Guidelines. Submitted.

ABSTRACT

The dental program at the Malmö Dental School, the so called

Malmömodel, is guided by four linked principles: selfdirected learning, teamwork, a holistic view of patient care, and oral health (Fig.1).

Figure 1. The four guiding principles of problem based learning at Malmö Dental School, Malmö.

Selfassessment ability is a critical competence for healthcare professionals, necessary for the successful adaptation to the modern lifelong learning environment. Educational research seems to point out two critical factors for the development of such skills, continuous practice of selfassessment (1) and constructive feedback (2). The first study (3) presented in this thesis assessed students’ selfassessment ability by means of the Interactive Examination in a

cohort of senior dental students, who had gone through an identical assessment procedure during their second year of studies (4). The results indicated that selfassessment ability was not directly relevant to subject knowledge. Upon graduation, there were a number of students (10%) with significant selfassessment difficulties. Early detection of students with weak selfassessment abilities appears possible to achieve.

The aim of the second study, concerning teamwork and holistic view (5), was to investigate if highlighting teamwork between dental and dental hygienist students could improve the students’ holistic view on patients, as well as their knowledge of, and insight into, each other’s future professions. This project showed that by initiating teamwork between dental and dental hygienist students, it was possible to increase students’ knowledge on dental hygienists competence, develop students’ perceived holistic view on patients, and prepare students for teamwork.

The third study explored findings clinicians used when diagnosing chronic periodontitis. A questionnaire was distributed to students, dental teachers and clinical supervisors in the Public Dental Services. Within all categories of clinicians, the majority of the clinicians used deepened pocket, bone loss on xrays, and bleeding as findings. There were differences in the use of findings between the categories of clinicians. None of the supervisors used attachment loss as a finding, while 13% to 27% of the other categories of clinicians used this finding. A higher frequency of dental hygienist students used plaque, calculus and pus, compared to the other categories.

Dental hygienist students used more findings for diagnosing as compared to the other categories of clinicians. Fiftyeight of the 76 clinicians used each finding solitarily, i.e. one at a time, and not in combination to diagnose chronic periodontitis. However, about a third of the dental students and the supervisors only used findings either from the soft tissue inflammation subgroup or the loss of supporting tissue subgroup. With the exception of the dental teachers, the majority of clinicians within each category used

The third study (6) gave valuable information when designing the fourth study (7). In the fourth study, a questionnaire was distributed to 2,455 professional clinicians, i.e. dentists and dental hygienists in public and private activity, and dental students at the Dental School in Malmö. The results showed that two groups, representing dentists and dental hygienists delivering basic periodontal care in Sweden, were to a significant degree not sharing the knowledge basis for diagnosis and treatment planning. This may result in a less optimal utilization of resources in Swedish dentistry. The delivery of basic periodontal care was not in line with the severity of disease and too much attention was paid to the needs of relatively healthy persons. To change this pattern, the incentives in, and structure of, the national assurance system need to be adapted in order to stimulate a better intercollegial cooperation between dentists and dental hygienists in basic periodontal care.

POPULÄRVETENSKAPLIG

SAMMANFATTNING

Bakgrund

Tandläkarutbildningen vid Odontologiska fakulteten vid Malmö Högskola bygger på ”Malmömodellen”, som utgörs av fyra hörn stenar självstyrt och livslångt lärande, teamarbete, helhetssyn på patientomhändertagande och oral hälsa (Fig. 1).

Figur 1. De fyra styrande principerna för problembaserad inlärnings metodik vid Odontologiska fakulteten, Malmö Högskola.

Det övergripande målet med detta forskningsprojekt är att ur olika perspektiv belysa dessa grundprinciper samt att jämföra diagnostik och behandling av oral hälsa och sjukdom för olika kategorier av

Gemensamt för två av de fyra delarbetena är möjligheten att jäm föra agerandet hos studenter med de verksamma yrkesutövarna. Möjligheten till återkoppling till såväl utbildning som tandvården utanför utbildningarna är betydande.

Studie 1. Förmåga till självstyrt lärande

Denna studie syftade till att undersöka om förmågan till självvärdering är relaterat till ämneskunskap och om det förekom en kontinuerlig förbättring av denna förmåga under den 5åriga utbildningen. Självvärdering är en avgörande kompetens för den professionelle utövarens förmåga att ta ett eget ansvar för självstyrt lärande. Det är också uppenbart från flera publikationer att alla yrkesutövare inte har denna förmåga. Även om förmåga till självvärderingen inte ifrågasätts vet vi lite om hur man bäst stödjer studenterna i utvecklingen av denna förmåga. Forskning indikerar att två faktorer är viktiga kontinuerlig användning av självvärdering och konstruktiv återkoppling till studenten. Flera tvärsnittsstudier har beskrivit metoder för att stimulera och utvärdera studenters förmåga till självvärdering. Det saknas dock longitudinella data som visar förändringar i studentens förmåga över tid avseende deras självvärderingsförmåga under utbildningen och hur detta kan kopplas till effekten av olika utbildningsinsatser.

I den första studien användes en metod ”Interaktiv examination” där 42 studenter på termin 4 (år 2001) och senare på termin 910 (år 20042005) fick bedöma 1 respektive 3 kliniska fall och föreslå en behandling som värderades mot den behandling som utförts på patienten av en lärare. Samtliga studenter fick skriftligen identifiera skillnader och likheter mellan föreslagen och utförd behandling, samt definiera nya inlärningsmål. Den skrivna behandlingsplanen betygsattes liksom förmågan att identifiera nya inlärningsmål. Kvinnliga studenter redovisade signifikant bättre resultat avseende behandlingsplanen än de manliga studenterna. Hälften av studenterna som underkändes 2001 var godkända 2004 medan hälften av studenterna fortfarande var underkända. Detta innebar att även i slutet av utbildningen fanns 10 % som hade svårigheter

med självvärdering och att identifiera nya inlärningsmål. Det är intressant att 90 % av dessa kunde identifieras redan i början av sin utbildning. Studien visade på ett svagt samband mellan förmåga till självvärdering och ämneskunskaper.

Studie 2. Teamtandvård och helhetssyn

Avsikten med denna studie var att undersöka om ett bättre utvecklat samarbete mellan de båda studentgrupperna under utbildningen förbättrade helhetssynen på patienterna, teamarbetet mellan grupperna samt kunskaperna om varandras kompetenser.

Flera studier visar på epidemiologiska förändringar i Sverige i före komsten av tandsjukdomar. Dessutom är finansieringen av tandvård föremål för kontinuerlig översyn och omprioritering. I Sverige kommer också antalet tandläkare och tandhygienister att förändras. Prognosen från Socialstyrelsen för år 2023 är att antalet tandläkare minskar med 26 % till 5400 och antalet tandhygienister ökar med 47 % till 4700. Sammantaget förutsätter dessa förändringar en god kooperation mellan tandläkare och tandhygienister i syfte att optimera resursutnyttjandet och med en helhetssyn på vården med goda kunskaper om varandras kompetenser. Av tradition sker dock utbildningen av tandläkare och tandhygienister i utbildningar där samarbetet mellan studenterna är begränsat.

Deltagare i studien var 34 tandläkarstudenter och 24 tandhygienist studenter som gick sitt sista utbildningsår. I början av den näst sista terminen besvarade de ett frågeformulär som testade deras kunskaper om varandras kompetenser. Frågeformuläret byggde på ett tidigare publicerat formulär i Tandläkartidningen med frågeställningen ”Vilken tandvård har tandhygienisterna behörighet att utföra?”. Samtidigt med den ovan beskrivna undersökningen genomfördes projekt ägnade åt att förbättra och underlätta teamsamarbetet: • Företrädare för Folktandvården föreläste om teamprojekt

i sin verksamhet.

• Tandläkarstudenterna fungerade som handledare på tandhygienistutbildningen.

• Gemensamma patienter planerades tillsammans.

• Vid ett avslutande seminarium fick teamen redovisa vad som varit bra och vad som kunde bli bättre.

Projektet avslutades med att studenterna fick besvara ovan nämnda frågeformulär en andra gång, nu inkluderande en utvärdering av de ingående projekten.

Kunskaperna om tandhygienisternas kompetens hade ökat i nästan alla frågor. Avseende de genomförda projekten fick planering och genomförd vård på gemensamma patienter, samt tandläkarstudenternas arbete som handledare på tandhygienistutbildningen, högst betyg. Slutsatserna är att det är nödvändigt och möjligt att dels öka kun skaperna om tandhygienisternas kompetens, samt att öka helhets synen i vården av patienterna med ett utökat teamarbete i grund utbildningen.

Studie 3 och 4. Bedömning och behandling av

olika tillstånd av oral hälsa

De två avslutande studierna behandlar hur tandläkare, tandhygienister och studenter bedömer och behandlar olika tillstånd av oral sjukdom. Det finns betydande variationer inom tandvården för hur man diagnostiserar och behandlar sjukdom. Detta behöver relateras till de evidensbaserade medicinska insatserna som Socialstyrelsen fastställt i nationella riktlinjer. En central fråga är om det finns samma variation hos blivande yrkesutövare, såsom tandläkarstudenter och tandhygieniststudenter, som det finns bland redan etablerade kliniska utövare? Hur bedömer och behandlar studenter sjukdom av olika svårighetsgrad i jämförelse med erfarna tandläkare? Finns det variation mellan och inom grupperna av studenter och erfarna tandläkare? En naturlig följdfråga blir vilken betydelse variation i bedömning av olika grader av sjukdom har för den behandling som patienten får och om behandlingen är anpassad till sjukdomsbilden? Hur ser samarbetsformerna mellan aktörerna i teamet ut?

Frågeställningarna har belysts i avhandlingens tredje samt sista publikation. Bakgrunden till den tredje studien var att studenter på Tandvårdshögskolan i Malmö (TVH) använde diagnosen kronisk parodontit på ett icke konsistent sätt. Det har också genomförts ett antal internationella konferenser där man försökt definiera olika former av parodontal sjukdom. I Oslostudien från år 2007 lyfter man fram inkonsistensen vid registrering av parodontal sjukdom. I det tredje delarbetet var målet således att undersöka vilka fynd olika kategorier av kliniska utövare använde för att ställa diagnosen kronisk parodontit och om det fanns skillnader mellan och inom de olika kategorierna. En enkät med den öppna frågan: ”Vilka fynd eller kombinationer av fynd använder du för att ställa diagnosen kronisk parodontit?” distribuerades till sista terminens tandläkarstuderande och tandhygieniststuderande, kliniska lärare på TVH och handledare i Folktandvården i Region Skåne. Sjuttiosex kliniska utövare, som representerade de olika kategorierna, angav tjugofem olika fynd för att ställa diagnosen kronisk parodontit. De fynd som angavs mest frekvent av samtliga kategorier var blödning, fördjupad tandköttsficka och förlust av marginal benvävnad. Tandhygieniststuderande angav signifikant fler fynd än övriga kategorier och var mer benägna att använda irrelevanta fynd, dvs. fynd som inte beskriver själva sjukdomen, t.ex. tandsten, plack och rökning, jämfört med övriga kategorier. Stor variation inom en och samma kategori av kliniska utövare sågs också avseende vilka fynd som användes för att ställa diagnosen kronisk parodontit, dvs. om man angav fynd som påvisar inflammation i tandens stödjevävnad, förlust av tandens stödjevävnad eller om fynden var irrelevanta. Anmärkningsvärt var att de flesta deltagare använde fynden solitärt, dvs. de angav antingen ett fynd som påvisade inflammation i tandens stödjevävnad, ett fynd som påvisade förlust av tandens stödjevävnad, eller ett fynd som var irrelevant. Endast 12 av de 76 deltagarna angav att de kombinerade fynden för att ställa diagnos, dvs. en kombination av fynd som beskrev både förlust och inflammation av tandens stödjevävnad. Variationerna i vilka fynd man använde för att ställa diagnosen kronisk parodontit medför en risk att patienter med samma diagnos och sjukdomsbild får olika behandling av

olika kliniker, om fyndet som användes för att ställa diagnos också ligger till grund för behandlingen. Detta kan i sin tur leda till en kostnadsineffektiv behandling.

Avsikten med den fjärde och avslutande studien var att beskriva hur professionella utövare i den svenska tandvården och studenter diagnosticerar och behandlar parodontal sjukdom. Fanns det gemensamma värderingar mellan tandhygienister och tandläkare om hur en effektiv arbetsfördelning skulle organiseras? Återspeglades föreslagen behandling i sjukdomens svårighetsgrad? I vilken utsträckning var behandlingen i överensstämmelse med Socialstyrelsens nationella riktlinjer?

En enkät med tre olika fall av parodontal sjukdom sändes ut till 804 privatpraktiker, 809 tandläkare i Folktandvården, 802 tandhygienister, samt 40 tandläkarstudenter på sista terminen vid TVH. Fallen beskrevs med olika grad av parodontal sjukdom inklusive röntgenbilder. Deltagarna ombads bedöma diagnos och vilken behandling som var indicerad.

En majoritet, 94 %, av de som besvarade enkäten ansåg att en relativt frisk patient hade sjukdom och 97 % ansåg att risken för att utveckla fortsatt sjukdom var obefintlig till låg. Trots detta ansåg man att patienten behövde förebyggande vård. En majoritet föreslog relativt sett mer tandvård till friska patienter jämfört med patienter med svår parodontal sjukdom.

De två grupperna, tandläkare och tandhygienister, hade olika uppfattningar om hur man optimerar resursanvändningen inom tandvården. Föreslagna insatser bedömdes i hög grad inte vara i överensstämmelse med sjukdomens svårighetsgrad och för mycket uppmärksamhet riktades mot behoven hos relativt friska patienter. För att förändra detta bör strukturen i det nationella tandvårdsstödet förändras och de nationella riktlinjerna implementeras på ett effektivare sätt.

ABBREVIATIONS

PBL Problem Based Learning

CCC Comprehensive Care Clinic

DS Dental Students

DH Dental Hygienists

PP Private Practitioner

PDS Public Dental Service

TVH Tandvårdshögskolan (The Faculty of Odontology)

MAH Malmö University

DHS Dental Hygienist Students

INTRODUCTION

The dental program at the Malmö Dental School (TVH), the so called Malmömodel, is guided by four linked principles: selfdirected learning, teamwork, a holistic view of patient care, and oral health (Fig.1).

Figure1. The four guiding principles of problem based learning at Malmö Dental School, Malmö.

Selfdirected learning is implemented as problembased learning throughout the whole dental program (8). The holistic view is interpreted as caring for the individual rather than providing quantities of items of dental treatment. Furthermore, such a holistic view towards the patient should encourage students to approach their knowledge and understanding, skills and ability, judgment and

stance as expressed in the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance (9). In turn, the holistic view provides a basis for oral health to be maintained, that has been chosen in preference to dentistry seen only as a practical skill. To achieve this, teamwork is developed through work in study groups as well as in clinical settings (5).

In the clinical setting, students take care of their own patients from their second to their final semester. Students have a gradually increasing responsibility for the oral health care of their patients, who present oral health needs of increasing complexity. From the onset, an environment is created in which provision of care is related to: (i) a fundamental understanding of the needs and demands of the individual patient, (ii) evidencebased clinical interventions, and (iii) an interdisciplinary approach to oral health care. This is enhanced during the 8th to the 10th semesters when students, assisted by dental nurses, experience comprehensive care in teamwork with dental hygienist students and dental technicians. The prescription of dental laboratory work is another important inherent part of the program especially during this comprehensive care period. This is essential because teamwork contributes to a developed holistic view. This thesis contains four publications trying to highlight these four linked principles. Thus, each principle will be linked to the studies in the thesis.

Publications 3 and 4 specifically compare students to dentists and dental hygienists outside educational programs.

Ability to self-directed learning

Selfassessment ability is a critical competence for healthcare professionals, necessary for the successful adaptation to the essential and imperative lifelong learning in a modern healthcare context. Educational researchers seem to agree that selfassessment ability, especially in a professional context, is a skill which can be learned, developed and excelled (10). It is also evident that not all professionals possess this ability to a satisfactory degree, thus jeopardizing the implementation of lifelong learning attitudes (11).

Although the importance of selfassessment seems unquestionable, not much is known about how to best assist students in their development of this ability. Furthermore, numerous studies at various levels of training have shown that healthcare students often possess modest to poor selfassessment abilities (12). Educational research seems to point out two critical factors for the development of such skills and these are continuous practice of selfassessment (1) and constructive feedback (2). Based on these two elements, several authors have to various extents described and evaluated methodologies designed to assist the development and even assessment of students’ self assessment ability (3,12,13).

However, the majority of available research consists of oneshot crosssectional studies. Such studies offer important insights, but lack the ability to investigate development and change over time. There is a current lack of longitudinal data in the field of selfassessment ability. Longitudinal data could allow educators to better register and follow how students’ selfassessment abilities develop throughout the curriculum and would also provide the urgently needed documentation for the effectiveness of educational interventions. The Interactive Examination is a structured examination scheme aiming to assess not only students’ knowledge and skills, but also their ability to accurately assess their own competence (4). The first study presented in this thesis “The interactive examination in a comprehensive oral care clinic: a threeyear follow up of students’ selfassessment ability”, assesses students’ selfassessment ability by means of the Interactive Examination in a cohort of senior dental students. These had gone through an identical assessment procedure during their second year of studies. The study aimed to assess students´ selfassessment ability, in parallel with their knowledge and competences.

Teamwork and holistic view

In Sweden, the National Board of Health and Welfare forecasts a decrease of the number of dentists with 26% and an increase of dental hygienists with 47% until the year of 2023 (14). This, together with changes in both epidemiology, especially of dental caries,

and political priorities, calls for an effective and welldeveloped cooperation between dentists and dental hygienists in the future of dentistry.

Hence, the aim of the study concerning teamwork and holistic view was to investigate if highlighting teamwork during the undergraduate studies of dental students and dental hygienist students, could improve the students’ holistic view on patients as well as their knowledge of each other’s future professions.

Oral health

This work began with the third study entitled “What findings do clinicians use to diagnose chronic periodontitis?” (6), which in turn offered valuable information when designing the fourth study entitled “A comparison of proposals for diagnosis and treatment by dentists, dental hygienists and undergraduate students. An analysis based on the recommendations from the Swedish National Guidelines” (7). The fourth study was distributed to 2,455 professional clinicians, i.e. dentists and dental hygienists in public and private practice and dental students at the dental school in Malmö.

It should be mentioned that the third study was the second one in a time line but, since it related more to the principal of oral health, it has more connection to the concluding fourth publication. The results were used when constructing the questionnaire for the fourth publication.

The third and fourth study were ethically approved by the Regional Ethical Board in Lund with registration numbers 317/2006 and 593/2010, respectively.

AIMS

The aims of this thesis were to highlight, from different perspectives, the basic principles guiding the education at TVH. The thesis consists of four publications.

• Study I: The interactive examination in a comprehensive oral care clinic: a threeyear follow up of students’ selfassessment ability.

Leisnert L, Mattheos N. Med Teach. 2006 Sep;28(6):5448. This study aimed to find out whether selfassessment ability is relevant to subject knowledge and if there was continuous improvement in this regard in the 5year educational program.

Since there was a lack of longitudinal data showing how students’ selfassessment abilities develop throughout the curriculum, this study tried to assess students’ selfassessment ability at two points in their studies (2nd and 5th year).

• Study II: Improving teamwork between students from two professional programs in dental education.

Leisnert L, Karlsson M, Franklin I, Lindh L, Wretlind K. Eur

J Dent Educ. 2012 feb;16(1):1726. doi: 10,1111/j.1600– 0579.2011.00702.x. Epub 2011 Sep 27.

This study had the objectives of examining whether placing a stronger emphasis on teamwork during the undergraduate studies of dental and dental hygienist students could:

– Increase the students´ knowledge of future professional collaborations with special emphasis on the dental hygienists´ field of competence;

– Develop a holistic view and approach towards patients, as experienced by the students;

– Prepare the students for teamwork in their future professional life.

• Study III: What findings do clinicians use to diagnose chronic periodontitis?

Leisnert L, Hallström H, Knutsson K. Swed Dent J. 2008;32(3):11523.

This was the first study in the thesis on the issue of diagnosing chronic periodontitis. The aims were to examine:

– What findings dental students, dental hygienist students, dental teachers, and supervisors in Public Dental Health used in order to diagnose patients with chronic periodontitis; – Whether different categories of clinicians used different

findings to diagnose chronic periodontitis. The hypothesis was that there were differences both between and within the categories of caregivers;

– Whether irrelevant clinical findings were used in diagnosing chronic periodontitis.

• Study IV: A comparison of proposals for diagnosis and treat ment of periodontal conditions by dentists, dental hygienists and undergraduate students. An analysis based on the recom mendations from the Swedish National Guidelines.

Leisnert L, Axtelius B, Wennerberg A. Submitted. The aims of this study were to explore:

– How professional clinicians in dentistry performed diagnostic procedures in general;

– If there was a common ground between dentists and dental hygienists concerning sharing different job assignments in an effective way;

– If the methods of treatment used was in accordance with the degree of severity of the disease;

– To what extent the proposed treatment was in accordance with the National Guidelines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study I. Guiding principle: self-directed learning

The Interactive Examination Method

The interactive Examination was introduced in 1998 at the faculty of Odontology, Malmö University (4). A number of studies have evaluated different applications of the Interactive Examination, including webbased (4) and teleconferencebased ones (15). The important element for the assessment of reflective skills appears to be the so called “comparison document” (4) . In this procedure, the students received a task in the form of a clinical problem and were expected to provide a written account of their solution, usually a diagnosis and treatment plan. Thereafter, they received a solution proposed by a qualified dentist. This solution was not the only or the best treatment possible, but represented a grounded opinion of a qualified colleague, reflecting his or her priorities and reasoning. The students then had to come up with a “comparison document” within a week, where they compared their own answer to that of the qualified dentist. In their comparison, the students were expected to identify differences and similarities between the two solutions, investigate and elaborate on the reasons why these differences existed, and consequently define learning objectives for the future. The assessment was based on two elements:

– Students’ subject related competence, as this was expressed through their proposed solution to the clinical case. The assessment of student’s performance was based on a matrix reflecting the specific learning objectives of each case.

– Students’ reflective skills, as expressed by their ability to point out weaknesses in their proposed solution, base their choices on sound arguments, and consequently define relevant future learning needs. The assessment of this skill was done through a special matrix (see Table 1, Study I, p. 545) which assessed the student’s comparison document on a scale ranging from 39.

The sample

A whole cohort of final year students (n=48) went through the Interactive Examination with three clinical cases in the Comprehensive Care Clinic (CCC) during a period from November 2004 to January 2005. The students of that year had a final theoretical and practical examination in December, and the successful completion of this allowed them to start their six month period of vocational training in public dental clinics. Consequently, the students completed the first two cases before their final examinations and worked through the third case right after this examination.

The clinical cases

A special project site was created in “Web zone”, the Internet learning content management system, used at Malmö University at that time. All students and resource persons were registered members of the project and had access to public functions, as well as a private folder. Each case was presented at a given time through an interactive PowerPoint slideshow. Below the appropriate hyperlinks, each case provided the student with general and dental history, current status, major complaints, patient’s wishes, extraoral, intraoral and xray images. After each case was published, students had about two weeks to come up with a written complete treatment plan, which they should then upload in their private folder.

When this stage was completed, the author of the case could publish the treatment plan he followed together with the outcome of the treatment. Students then had another week to compare their treatment plan to the one published and prepare a written comparison document, according to the previously described principles.

The feedback the students received after each case was organised in two forms:

• A written commentary, presenting the key issues of each case and discussing the most common characteristics of students’ treatment choices.

• A group discussion where each case and the treatment plan, as well as students’ common choices, were thoroughly discussed with the case author and expert resource persons, respectively.

Evaluation of performance

Each student’s written treatment plan (see Table 2, Study I, p. 546), was evaluated by use of a specific matrix. The matrix for each case included a number of key issues representing knowledge and attitudes a clinician must have, according to the established standards of the CCC. These key issues were expressed in equivalent points, the number of which differed slightly in the three cases. The maximum score for case one, two and three was 18, 21 and 17, respectively, with the level of acceptance set to 12, 14 and 11 points. The evaluation framework was designed by the author (LL) of the three cases, who was also the one to grade students’ performance. The case in 2001 was assessed on a scale ranging from 16.

Students’ comparison documents were evaluated through the previously designed matrix (see Table 1, Study I, p. 545). This matrix was used for all three cases and it was also used in 2001 for the same purpose.

Evaluation of attitudes

Students’ attitudes were evaluated after the completion of each case through an anonymous, standardised questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Grades on the written treatment plan were analysed for the 42 students who participated both in the 2001 and 2004 cohorts. Differences between male and female student’s scores within each case were analysed with unpaired ttest. The grades for both the written treatment plan and the comparison document for each case in 2004 were compared with performance data of the same students

in the year 2001, with a linear regression analysis. The students who presented unacceptable comparison documents in 2004 were compared with those unacceptable in 2001, in an attempt to track weak students’ development.

Individual student differences between grades in the comparison document of each of the cases in 2004 and the same in 2001 were analysed with a paired ttest.

Study II. Guiding principles: teamwork, holistic view

Students from two dental programmes, dental hygienist and dental students participated in the study.

The project was designed as an intervention study with different activities including seminars, treating patients together, and with presentations of the outcomes of the treatments, framed by pre and posttest. As a pretest a questionnaire was used (16), mapping the students’ knowledge on a sample of the dental hygienists´ competences. Posttest included answering the same questionnaire once more, with questions relating to how the different activities were experienced and to what extent they were deemed useful by the students.

Project organisation

In the research group for the project, responsible for planning, directing and carrying out the activities, students and staff from both the dental hygienist and dental programmes participated.

The project was introduced and started during the spring2007 by

launching a website within the learning management system of the Malmö University, acting as a platform for both information and interactions.

Participants

Beginning from their eighth and second semester, respectively, 34 dental students and 24 dental hygienist students participated in the study. Teams consisting of one dental student and one dental hygienist student were formed. As the number of dental students was larger than dental hygienist students, some dental hygienist students

Activities

A number of activities were carried out during the course of the study (Fig. 2).

Seminar 1 Seminar 2 Seminar 3

Jun -08 Dec -08 Mar -08 Sep -08 Mar -09 Questionnaire 1 Questionnaire 2 Teamwork

Dental students supervising

Figure 2. The figure depicts activities carried out during the course of the study.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of 23 questions on whether or not dental hygienists are licensed for the competences described in the different questions (see Appendix 1 in study II). The same questionnaire was answered one year later. Between the two tests a number of activities were performed.

Seminars

Three seminars were held during the course of the study:

Seminar 1: An introduction of the project including a session with a dentist from the Public Dental Services (PDS), presenting the visions and experiences of a teamwork model developed and successfully practised at the PDS.

Seminar 2: Presentations held by ten chosen teams of students, each group presenting different aspects of how to plan and carry out the treatment of two webbased patients. All students attended this seminar together with supervisors from different fields of dentistry.

Seminar 3: Presentations given by six chosen teams of students, each group presenting how they planned and carried out the treatment of shared patients in the students’ clinic. Discussions on the outcome of the treatment were also an integral part of this seminar.

Prior to the final session, the students were asked to write down problems and possibilities that they had encountered during their team collaborations. These were discussed during the last seminar, as well as the students´ suggestions for future professional cooperation.

Teamwork

As mentioned earlier, the dental students and the dental hygienist students were divided into teams. In these teams, they planned and carried out the treatment of both webbased patients and patients attending the students´ clinic.

The webbased cases were presented and made available on the website of the project, where electronic folders for each team were created as well. In the folders the teams documented their discussions and agreements regarding the webbased cases on the following items: diagnosis, treatment planning and prognosis.

In the folder they also had to document, present and discuss 24 shared patients from the student’s clinic. During the students’ clinical work, they and their clinical instructors could draw on the expertise of one experienced dentist and one experienced dental hygienist in order to support them with encouragement and pinpointing opportunities and advantages of teamwork.

Supervision

To increase the interaction surface between students and to an even greater extent provide opportunities for developing understanding and knowledge on how to cooperate as a dental team, the dental students supervised the dental hygienist students in their clinical practise on one to two occasions.

Students´ opinions on different activities

and parts of the project

Students assessed the different activities and how they valued their contribution in developing successful teamwork. The questionnaire used for this purpose was designed with a number of statements concerning the different activities, where students could mark whether they agreed or disagreed with the statements on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from 1 to 10.

Methodological considerations

The first questionnaire was answered by 32 out of 34 dental students and 23 out of 24 dental hygienist students. On the second occasion, 30 out of 32 dental students and 20 out of 20 dental hygienist students answered the questionnaire. The missing answers were due to electives, Erasmus exchange, interrupted studies or illness.

Study III. Guiding principle: Oral health

Study design

The questionnaire explored findings clinicians used when diagnosing chronic periodontitis, where one open question was: “What findings, or combination of findings, do you use when you diagnose chronic periodontitis?”

The questionnaires with included information were distributed to dental teachers at the faculty by one of the researchers (LL) in a personal meeting. Supervisors in the PDS were informed via email and after a general meeting at the faculty the questionnaires were distributed and answered directly after the meeting. The students filled out the questionnaire at the school in conjunction with their clinical work. The participation of the dentists was voluntary and anonymous, while it was regarded as a part of the education for the students. The licensed dentists stated their age, gender, years of experience as dentist, and specialists noted type of speciality. Teachers at the dental hygienist education did not participate because they were too few to form a group that could be statistically analysed and compared with the other categories of clinicians.

Clinicians

Dental students (DS):

Thirtyseven dental students, in their final month of a 5 year education at the TVH, were asked to participate. Twentytwo of the students answered the questionnaires. Thirteen were females and nine were males. The mean age was 27 years (range 2436) for the females and 26 years (range 2430) for the males. Fifteen students could not participate due to other commitments; these students were therefore not obliged to participate.

Dental hygienist students (DHS):

Sixteen dental hygienist students in their final month of a 2 year education at TVH, were invited to participate. Fourteen females and one male of a total of 16 students participated. The mean age was 31 years (range 2145 years). One student did not participate due to illness.

Dental teachers (DT):

Eighteen dental teachers in the CCC at TVH were invited to participate. The teachers worked at the CCC four to 16 hours per week. Twelve teachers participated, four of these were specialists in prosthodontics, two in periodontology and six were general dental practitioners. Six teachers were females and six were males. The mean age was 47 years (range 3467), for the males 53 years and for the females 41 years. The mean age of the 18 teachers that worked at the CCC were 45 years (range 3467). The questionnaires were returned anonymously in such a way that no dropout analyses could be performed without unmasking the anonymity. The reason for this being that dropouts could easily have been identified since they were all known by the authors according to age, gender and speciality.

Supervisors in the PDS:

Thirty dentists in PDS, who also had a role as supervisors for dental students in their period of outreach training, were invited via email for participation. Twentyseven supervisors, 15 females and 12 males, participated in the study. The mean age was 52 years (range 3665) for the females and 49 years (range 3064) for the males. Three of the 30 dentists did not participate due to other commitments.

Statistical analysis

If differences existed between the numbers of findings clinicians used when diagnosing chronic periodontitis, each category of caregiver was analysed with one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If differences existed, Tukey’s test was used to analyse between which categories these differences existed. Differences between different categories use of respective findings were analysed using the Chi squared test (p=0.05).

Study IV. Guiding principle: Oral health

Respondents

From each professional organization of dentists in the PDS, private practitioners (PP) and dental hygienists (DH), some 800 names were randomly selected for a questionnaire study. Of the respondents, 346 were PP, 349 from the PDS, 369 DH and 39 DS on their tenth and last semester of their five year dental education.

A questionnaire was constructed consisting of three typical patient cases showing different degrees of periodontal disease. The case construction was made in accordance with the grouping in the first Jönköping study (17) and used throughout their following studies up to 2008.

The questionnaires were distributed in the beginning of October 2011 and it was followed by two reminders, four and seven weeks after the original distribution, to those who did not answer the first mail. In total, 2,455 questionnaires were sent out and the participation was voluntary and anonymous. The questionnaire was completed by 1,103 respondents (47%), while 1,226 did not return the questionnaire and 126 were returned by the Postal Service, i.e. it was not possible to deliver or the respondents mailed back and informed us that they for different reasons did not want to answer the questionnaire. The reasons for this were e.g. weakened health, no present activity in their profession or the questionnaire was too extensive and time consuming. The DS answered the questionnaire in conjunction with one of their clinical session. Of the students, 40 received the questionnaire and 39 answered it (98%). Four students were absent due to illness and other commitments. The students also participated voluntarily.

The completed questionnaires were scanned at the University of Linköping and transformed into a SPSS file. The scanned questionnaires were validated through a random sample (n=120) of all the questionnaires securing that a specific questionnaire with its number in the SPSS file had the right characteristic concerning age and gender. No misrepresented data was discovered.

Description of the clinical cases in the questionnaire:

Case 1 healthy individualFemale, 45 years old, healthy and no medicines. Yearly checkups. Plaque index 28% , bleeding when probing 22%. Small amount of calculus in the front of the lower jaw. No horizontal bone loss.

Case 2 localized mild periodontitis

Male, 55 years old, healthy and no medicines. No checkup for the last 3 years. Has the feeling that it is bleeding when he brushes his teeth. Plaque index 40%, bleeding when probing 31%. Subgingival calculus and pus 17m, 16d and 26d. Deepened pocket >4 mm at 24 surfaces. Marginal bone loss ≤1/5 of the root. Vertical bone pockets 17md, 16d, 46d, 26d and 27m. Furcation involvement 17, 16 and 26.

Case 3 generalized advanced periodontitis

Male 45, years old. Medical treatment of high blood pressure. In other aspects healthy. Smokes 20 cigarettes/day. New patient, no checkup for the last 5 years. Has the feeling that it is bleeding when he brushes his teeth. Plaque index 50%. Bleeding when probing 41%. Subgingival calculus lingually in lower jaw. In general, deepened pockets >4mm. Generalized marginal bone loss 1/31/2 of the length of the root. Bone pockets 36m and 46m. Furcation involvement 16, 26, 37, 36, 46 and 47.

In the questionnaire to the clinicians, there were questions concerning gender, age, whether they worked in private or public dental service, whether they worked in big or small towns and where they were educated. In each case, there was a question if the patient was considered to have periodontal disease or not and whether treatment was suggested or not.

Also, there were questions about what clinical findings they used for the diagnostic classifications, what treatment was proposed, and which category of caregiver – dentist, dental hygienist or specialist – they deemed best suited to perform the treatment. There were choices from a list of alternative treatments possible to combine. All treatments were chosen from the National Guidelines as presented by The National Board of Health and Welfare.

Statistical analysis

All data was inserted into the IBM SPSS Statistics version 20. An analysis of the missing answers, compared to those who answered, was made with a logistic regression analysis concerning age, gender and occupation. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups concerning these factors.

A frequency analysis was made for all groups together for the different questions and cross tabulation with Pearson Chisquared test was used to analyse differences between the participating groups.

RESULTS

Study I. Guiding principle: self-directed learning

The average scores of students’ written treatment plans and comparison documents in the three cases mentioned above can be seen in Table 2, Study I, p. 546. Only the grades of written treatment plans in case 2 in 2004 were positively correlated with the respective grades in 2001 (p=0.02, r= 0.34). Female students performed significantly better than males in two out of three cases in the written treatment plan in 2004.

Regarding the comparison documents, the grades on case 1 (p=0.001, r = 0.48) and case 2 (p = 0.0002, r = 0.55) presented a strong positive correlation with the respective grades in year 2001. Comparing document grades in the year 2004, these were in all three cases higher than those of 2001, but the difference was statistically significant only for case 1 (p < 0.0001). Female students received significantly higher grades than males in all three cases.

A total of eight comparison documents were judged unacceptable throughout the three cases. All eight documents originated from five students, four of which were also among the nine students who were judged unacceptable in the year 2001 in the same field. The average score in the 2004 comparison document for these nine students (unacceptable in 2001) was 6.1 for the first case, 4.5 for the second, and 5.1 for the third. This was in all cases lower than the average score of the cohort and this difference was statistically significant for cases 1 and 2 (p = 0.01 and 0.001), respectively.

Study II. Guiding principles: teamwork, holistic view

Students’ knowledge on the competences of the dental hygienistThe results of the first questionnaire showed that it was mostly the dental students who lacked knowledge of the competences of the dental hygienists. In nine out of 23 questions more than 50% provided a wrong answer. For instance, between 50 to 70% did not know that dental hygienists (in Sweden) are allowed to: decide on, carry out and diagnose xrays concerning caries and periodontitis; prescribe alcohol, fluoride and anaesthetics to their place of work; decide on and carry out bleaching of teeth; glue small pieces of jewellery on the teeth; and/or decide on and carry out bacterial analyses of saliva.

Concerning dental hygienist students, more than 50% answered wrongly in five out of the 23 questions. Their gaps of knowledge were on: not being aware of allowance to possess xray equipment when practicing on their own; not being allowed to diagnose diseases in mucous membrane; being allowed to carry out fissure blocking; decide on and carry out bleaching of teeth; and/or to manufacture a bleaching tray.

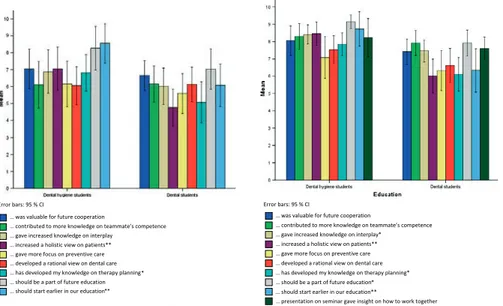

At the concluding seminar, the students’ knowledge had improved on about almost all matters in the questionnaire (see Figures 2a and 2b, in Study II, p. 3).

Evaluation of activities carried out during the project

1. Seminar on teamwork with adentist from the Public Dental Health Services.

Dental hygienist students (DHS) rated this seminar to 6.9, while dental students (DS) rated it 5.3.

2. The fictional webbased clinical cases, with treatment planning in teams followed by a seminar with a presentation of the sug gested treatment.

We noted a significant difference between the dental hygienist students who scored 4.5 and the dental students who scored 6.7, whether to what degree this activity was valuable or not (see Figure 3, Study II, p. 4).

3. Question to the students: Have the two questionnaires on dental hygienists competences increased your knowledge on which competences dental hygienists have?

Dental hygienist students gave a scoring of 6.6 and the dental students 7.2.

4. Dental students supervising dental hygienist students.

This part scored high especially among the dental hygienist students (7.1), who claimed that the teamwork had increased, the holistic approach on patients had been strengthened, and that they had gained valuable experiences for future cooperation. Concerning the holistic view on patients, there was a significant lower score from the dental students (4.8). Both groups found it valuable to make this part permanent (DHS=8.2; DS=7.0) (see Figure 4, Study II, p. 4).

5. Teamwork with shared patient.

Both groups of students felt that treating shared patients should become a permanent part of the education (DHS=9.1; DS=7.0) and start earlier (DHS=8.7; DS=6.3, a significant difference). In addition, the students experienced sharing patients to increase the knowledge – interplay concerning teamwork (DHS=8.4; DS=7.5, a significant difference) and the knowledge on the team members’ competences (DHS=8.3; DS=7.9). Furthermore, it gave valuable experiences for future cooperation (DHS=8.0; DS=7.4) and a more holistic view on patients (DHS=8.5; DS=6.3, a significant difference).

The dental hygienist students display the same pattern of giving higher scores on questions (see Figure 5, Study II, p. 4).

Study III: Guiding principle: Oral health

After the data had been collected, the questionnaires were read by all the authors. Analyses of the answers were performed stepwise. In a first step, the questionnaires were scrutinized to find contentword or concepts that could be coded as a finding. Twentyfive different findings were identified as findings the clinicians used to diagnose chronic periodontitis. In a second step, different contentwords or concepts that could be interpreted as the same finding were brought

together. For example, bleeding on probing and bleeding index were registered as bleeding. Further, subgingival and supragingival calculus were registered as calculus, and plaque and plaque index were registered as plaque. In a third step, findings registered by less than three participants, were excluded. Such findings were age, halitosis, genetics, and diabetes. After these steps, 13 findings remained and were further analysed.

Findings

The 13 findings were divided into three subgroups showing: soft tissue inflammation, loss of supporting tissue, and irrelevant findings, i.e. findings that were considered not to be relevant for diagnosing the disease per se. (see Table 1, Study III, p. 118) presents the subgroups of these findings.

Figure 1, Study III, page 119, presents the number of clinicians that used each of the 13 findings to diagnose chronic periodontitis. Within all categories of clinicians, the majority of the clinicians used deepened pocket, bone loss on xrays, and bleeding. There were differences in the use of findings between the categories of clinicians. None of the supervisors used attachment loss as a finding, while 13% to 27% of the other categories of clinicians used this finding (p<0.05). A higher frequency of dental hygienist students used plaque, calculus and pus, compared to the other categories (p<0.05).

Dental hygienist students used more findings as compared to the other categories of clinicians (p<0.05) (see Figure 2, Study III, p. 119). They registered in average six findings that provided soft tissue inflammation or loss of supporting tissue. All the other categories used in average four findings. The different categories usage of the 13 findings is presented in Table 2 and 3 Study 3, page 120. There was a difference in the number of findings that each category of the clinicians used, as presented in Table 2. Fiftyeight of the 76 clinicians used each finding solitarily, i.e. one at a time, and not in combination to diagnose chronic periodontitis. However, about a third of the dental students and the supervisors only used findings either from the soft tissue inflammation subgroup or the loss of supporting tissue subgroup. The distribution of clinicians that

used irrelevant findings is presented in Table 3. With the exception of the dental teachers, the majority of clinicians within each category used irrelevant findings.

Eighteen clinicians, four dental students, two dental hygienist students, seven dental teachers and five supervisors, out of totally 76 participants, reported that they combined two findings to reach the diagnosis. However, of these 18 clinicians only 12 combined one finding that provided soft tissue inflammation with a finding that provided loss of supporting tissue. The other four only combined findings that all provided loss of supporting tissue.

Study IV: Guiding principle: Oral health

In table 1 (see study IV, p. 10), market demand for clinicians in different dental care sectors are depicted. PP had the lowest number of dentists with patients waiting for dental care (17%), while the same figure for PDS was 52%. Lacks of patients were evident from 18% of the PP, 8% of the dentists in PDS and 8% of DH.

In table 2 (see study IV, p. 11), the results from the question whether the practitioners regarded the different patients to have a disease or not, are depicted. No significant differences were found between caregiver groups in case 1, 2 and 3. In case 1, almost 94% considered that the patient had disease, while 6% considered that the patient had no disease. For case 2 and 3, almost 100% had the opinion that patients had periodontal disease.

In table 3 (see study IV, p. 12), the clinicians were asked to describe what risks they forecasted for developing gingival or/and periodontal disease. The different groups scored between 86 to 97%, with 86% saying the risk is low and 97% saying the risk is none or low. No significant differences were found between the groups. The 2.6% of the students saying there was no risk of developing disease in any of the cases, represent one student.

Table 4 (see study IV, p. 13), depicts whether the respondents regarded that the patients needed preventive care or not. In case 1, the students to a greater extent rejected that preventive dental care

was needed, i.e. 17% in comparison to the other groups who scored about 8%. However, there were no significant differences between the caregiver groups. Still, about 91% of the professional clinicians wanted to give preventive care in this case.

In table 5 (see study IV, p. 14), the opinion is depicted about what category of dental caregiver should examine the patient. In case 1, there were significant differences between the groups: 74% of the private practitioners, 49% of the dentists in the public dental services and 59% of the students wanted the dentist to examine the patients, while only 21% of the dental hygienists considered a dentist should examine the patient (p=0.000).

In case 2, the corresponding figures for caregiver groups were 88%, 80%, 72% and 67%, respectively. A significant majority of dental hygienists considered that they should examine the patients, while a majority of the dentists thought that a dentist should examine the patients (p=0.000).

In case 3, the corresponding figures for caregiver groups were 85%, 50%, 92% and 70%, respectively. In this case, a majority of all caregiver categories considered that the dentist should perform the examination, although 45% of the hygienists felt prepared to do so. In general, private practitioners to a significantly higher degree wanted to perform the examination of the patients (p=0.000). Table 6 (see study IV, p. 16), depicts to what extent treatment was suggested and what category of dental caregiver should perform instruction for effective selfcare. Relative agreement could be found between the groups that dental hygienist should perform this treatment. Dental students and private practitioners had lower scores, i.e. less support for leaving this to dental hygienists. The respondents had a possibility to choose more than one option. There were significant differences between categories of caregivers in all 3 cases, with the exception of specialists.

In Table 7 (see study IV, p. 17), the respondents were asked to describe what findings they used for diagnoses with regard to presence of plaque and calculus.

Table 8 (see study IV, p. 19), depicts what category of dental caregiver should perform professional cleaning of the teeth, according to the respondents. A significant difference appeared. In case 1, 15% of the PP wanted to give professional cleaning, while 0.3% of the DH wanted the dentist to perform this procedure. The corresponding figures for PDS were 7% and DS 0%, respectively (p=0.000). The PP was more inclined (25%) to let the dental nurse perform this treatment (p=0.000).

DISCUSSION

In the book “Qualitative methods” by Malterud (18), the author claims three fundamental conditions for scientific knowledge – relevance, validity and reflexivity. Relevance tells us what the new knowledge could be used for. Validity is about if the new knowledge is true and can be transferable to other situations and conditions. Reflexivity is about the researcher’s ability to raise questions and doubts around the results from the research results. During this discussion these aspects will be highlighted related to the different publications.

Study I: Guiding principle: self-directed learning

The main focus of the first study was the reflective process, which is initiated through comparing your own work with that of someone else. This process is well founded in students’ selfassessment ability, which is a necessary professional skill. In this study, selfassessment ability is addressed as it applies on professionrelated activities. The general skill of selfreflection, however, appears to be more of an element of personality, often associated with personal and cultural characteristics (19). It would be of great interest in future studies to investigate how the general selfreflection ability is connected with professional or taskrelated selfassessment skills.

Very few studies with a longitudinal perspective are available in this field. One study (20) followed medical students’ selfassessment ability at four intervals over the course of their first three years. They concluded that selfassessment accuracy measures were relatively stable over the first two years. In another study (21) conducted during

the first year of dental education, it was found that students’ self– assessment ability increased during the course of three consecutive semesters.

The students in this study had an opportunity early in their studies for selfassessment, i.e. in 2001, when their professionrelated self assessment ability was evaluated. In the three years that followed, the students did not go through any structured intervention of the same magnitude. However, as their PBL curriculum included many instances of selfassessment and constructive feedback, one should expect that by the end of their studies these students would present a more mature and complete ability to assess their competence. This is actually one of the critical functions of the healthcare curriculum, although rarely evaluated (22).

The students’ task in 2004 to present a written treatment plan is not comparable to the written task they had in 2001. Therefore no attempt was made to compare students’ performance in this respect. However, correlations of their grades between 2001 and 2004 were investigated in order to see if the patterns of students’ achievements were repeated. The correlations between the written treatment plans with grades between 20012004 were in general poor, while there was a moderate positive correlation in one of the three cases. In contrast to the written task, the comparison of documents was used in the same way both in 2001 and 2004 and is the main focus of the study, as it attempts to evaluate not subject related knowledge but reflective skills. Interestingly, the grades of the selfassessment ability in 2004 presented a higher correlation with those of 2001, than the actual subject related knowledge did. In addition, as seen in case 3, selfassessment ability remained rather stable even when the written performance was low.

These observations indicate that the selfassessment ability was not directly tied to subject knowledge. Although students seemed to have developed their knowledge and understanding in different ways in the years that followed 2001, their selfassessment ability was correlated to the one measured in 2001 much more than their

actual subject knowledge was. Consequently, the improvement of the selfassessment skills should be a parallel and independent aim in every healthcare curriculum.

Still, it remains unclear whether the selfassessment skills had in general improved during these three years. Grades indicated a moderate improvement, but the possible interassessor variation did not allow for firm conclusions. However, the fact that the number of comparisons below the level of the acceptable was much smaller in 2004, might be indicative. Half of the students judged as unacceptable in 2001 were found to have an acceptable level in three consecutive tests in 2004, although still remaining below the average scores of their fellow students. However, the other half remained on an unacceptable level. This fact suggests that even at the latest stages in their studies, there were students (5 out of 48 – i.e. 10% in our case) who had significant difficulties in assessing their own actions and defining learning objectives. An interesting observation was that 90% of these students were identified already in 2001. The sensitivity of the 2001 examination in predicting the weak students in 2004, based on these figures, was therefore 80% and the specificity 86%. Herein lays one of the most important benefits of longitudinal observation, which is to enable validation of the predictability of the earlier measurements of selfassessment ability.

Strengths and weaknesses

There is a lack of studies showing how progress concerning self assessment develops during the students dental studies. This study assessed students’ selfassessment ability at two points during their studies, making it possible to register if there is any progress during their five year education. Could it be that this differs between different educational concepts? The present interventions were conducted within a full PBL curriculum, which is expected to place a large emphasis on selfdirected learning principles. Similar studies comparing the impact of the curriculum (PBL or not) on the development of selfassessment ability would be of great interest. The study is valid with respect to the possibility to early detection of students with weak selfassessment – in this study 10% of the respondents.

It is more uncertain if there is any connection between selfassessment ability and subject knowledge. In the future, prospective intervention studies are needed to further verify the findings of this single, relatively small study. Special care should be taken to address if and how remedial interventions can help weak students to develop an acceptable level of selfassessment ability before graduation.

Study II: Guiding principles: teamwork, holistic view.

Knowledge on competenceThis study had the aim to investigate whether it was possible to increase a holistic view and improve teamwork in patient care between dental students and dental hygienist students in an undergraduate education context.

Both dental hygienist students and dental students in this project demonstrated an increased knowledge regarding the competences of dental hygienists, as well as a perceived increased understanding and appreciation of some of the common principles of the programmes. Moreover, according to what the students expressed in the evaluation comments, merely sharing patients, planning and performing treatment together, contributed to a more holistic view of the patient and gave valuable experiences for cooperation in their future professional roles. Thus, without this cooperation, especially the dental students would have graduated with considerable knowledge gaps of the dental hygienists competences and it would presumably have proven to be an obstacle for them in developing a fruitful and effective teamwork in the future.

The reasons for testing the students’ knowledge on only competences of the dental hygienists were several. First, one publication (16) found that dentists’ knowledge on this issue was low. Further, they suggested that undergraduate dental students should be better prepared within this field in order to be able to lead and develop a successful teamwork. Third, the competences of dentists are not limited like those of the dental hygienist and are therefore more clear cut and known therefore, there was no need to ask for them. Fourth, the development of teamwork between dental hygienist students and dental students depends to a large degree on the students’ knowledge

of what a dental hygienist license includes. If the dentist do not know what the hygienists are allowed and have education for to perform, it would be troublesome for the dentist to leave parts of the dental care to the hygienists.

Seminar with dentist from Public Dental Health Services

The relatively low ratings on the seminar with a dentist from the PDS could be an effect of a poor performance on the part of the lecturer. On the other hand the comments on the event revealed that it was valued positively in terms of initiating reflections and that the seminar was stated as a good start for the project. The seminars with participants from dental care external to the faculty were recommended to be a permanent part of the curriculum and that it could stimulate students´ knowledge’s and reflections on how to perform good dentistry.

Webbased clinical cases

In general, the dental students were more positive to this activity. Judging from the written comments, the reason behind this probably was because the cases consisted of complicated prosthetic cases which the dental students were more familiar with, compared to the dental hygienist students. Comments suggested that the dental hygienist students found it too difficult to participate in the debate as the case was too “dentist” focused.

The two questionnaires

When asked if the two questionnaires contributed to increased knowledge, the dental students gave higher scores, indicating they felt their knowledge had increased more. It is likely that this was due to their large initial knowledge gaps, and thus they had more to learn.

Dental students supervising dental hygienist students and cooperation with shared patients

It is harder to grasp why dental hygienist students to a higher degree than dental students claimed that they received a more holistic view on patients, when treating shared patients and/or when dental students acted as supervisors. One explanation could be that the dental hygienist students experienced broader perspectives and