Healthcare professionals’ knowledge about

Autism Spectrum Disorder in children

A Systematic Literature Review

Gladys Ayakaka

One year master thesis 15 credits Supervisor

Interventions in Childhood Ingalill Gimbler Berglund & Emelie Pet-tersson

Examinator

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION (HLK) Jönköping University

Master Thesis 15 credits Interventions in Childhood Spring Semester 2021

ABSTRACT

Author: Gladys Ayakaka

Main title - Healthcare professionals’ knowledge about Autism Spectrum Disorder in children

Subtitle – A Systematic Literature Review

Pages: 26

Good prognosis for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their participation in everyday life situations depends on healthcare professionals’ ability to make diagnoses and provide interven-tions as early as possible. Thus, professionals at the primary healthcare level ought to have the knowledge and competence to identify the symptoms of ASD and make referrals where necessary. This study aims to describe healthcare professionals’ knowledge regarding ASD symptoms in chil-dren, and the factors that influence their level of knowledge.

A systematic literature review method as described by Jesson, Matheson & Lacey was used to study the topic, and searches in CINAHL, PsycINFO and PubMed generated 10 relevant articles for the study. Their quality was assessed using the critical review form and content analysis was used to evaluate the findings. ‘healthcare knowledge’ by Kohn were used to explain them. Findings showed that healthcare professionals have varied levels of knowledge regarding ASD symptoms depending on different factors like professionals’ age, years of work experience, previ-ous encounter with children having ASD, among others. The concept, theory-practice gap and types of knowledge were used to explain the findings.

Conclusion: Firstly, increase in ASD training among healthcare professionals is necessary and

secondly, it needs to translate to practice for quality care towards children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, symptoms, healthcare professionals, knowledge, identification, awareness, children Postal address Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation (HLK) Box 1026 551 11 JÖNKÖPING Street address Gjuterigatan 5 Telephone 036–101000 Fax 036162585

Table of Content

1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background on ASD 1 1.2 Children’s rights 2 2 Theoretical framework 3 2.1 Knowledge 32.2 The theory-practice gap 3

2.3 Rationale 4

2.4 Purpose 5

3 Method 6

3.1 Design 6

3.2 Literature search strategy 6

3.3 The inclusion and exclusion criteria 7

3.4 Selection of articles 8

3.4.1 Screening – title and abstract 8

3.4.2 Screening – Full text 8

3.5 Data extraction 11

3.6 Quality assessment 11

3.7 Data analysis 11

3.8 Ethical considerations 14

4 Results 16

4.1 Factors affecting level of knowledge 17

4.1.1 Previous encounter and work experience with ASD 17

4.1.2 Age and years of work experience 17

4.1.3 Nationality and country of primary qualification 18

4.1.4 Level of education and area of speciality 18

4.1.5 Beliefs and attitude towards care for children with ASD 19

4.1.7 Self-perceived competence 19

4.1.8 Awareness about community resources 20

5 Discussion 22

5.1 ASD knowledge among healthcare professionals 22

5.2 Impact on child participation 24

5.3 Limitations and strength of the study 25

5.3.1 Methodological limitations 25

5.3.2 Strength 26

5.4 Practical implications and future research 26

6 Conclusion 26 References 28 Appendices 34 Appendix A 34 Appendix B 35 Appendix C 36 Appendix D 38

1 Introduction

1.1 Background on ASD

Autism Spectrum Disorder, as defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental diseases [DSM-5] is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent deficit in social communication and interaction across various contexts (Ameri-can Psychiatric Association, 2013). Social communication, according to the manual, must be accompanied by controlled and repetitive patterns of behavior for a child to receive ASD diagnosis.

In simple terms, specific ASD social communication symptoms include absence of back-and-forth conversations, lack of non-verbal communication by avoiding eye contact, for instance, deficit in initiation, sustenance, and comprehension of relationships, while symp-toms of compulsive behavior include repetitive movement or use of objects and speech, insistence on the same patterns of behavior such that the slightest change in routine leads to great distress, fixation and strong attachment to certain objects and interests, and hyper or hypo reactivity to phenomena related to the sensory organs; that is, poor response to certain sounds and touches for instance. American Psychiatric Association (2013) and Yates & Le Couteur (2016) have reported on this. They have also noted that the symptoms are usually recognizable between as early as 12 months of life but could manifest earlier or later depending on severity of developmental delays or subtlety of symptoms.

Competent identification and specification of symptoms is important because it informs the diagnostic process. Studies by James & Smith (2020) and Campisi et al. (2018) show that diagnosis still happens relatively late, implying missed chances for timely intervention during the crucial developmental stages. Some factors mentioned in literature as affecting diagnosis in addition to limited knowledge among healthcare professionals (Mazurek et al., 2020; Jain et al., 2020; Ghaderi & Whatson, 2019; Shrestha & Shrestha, 2014) are culture and gender (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). To exemplify, children from low socioeconomic and/or ethnic groups may get late or no diagnoses due to stigmatization associated to mental disorders and/or limited finances to seek medical consultation (Amer-ican Psychiatric Association, 2013; Bello-Mojeed et al., 2017).

Regarding gender, a ratio of one girl to four boys get a diagnosis due to subtlety of symp-tom presentation in girls (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). James & Smith (2020)

however suggests that these discrepancies may have reduced since prevalence is now shown to be at a boy to girl ratio of 2.9:1.

Still, professionals only observe or meet children for short periods during routine checks and in limited contexts such that caregiver information is what they can mostly rely on (Ozdemir et al., 2020). To sync caregivers’ information with professional-observed symp-toms and make ASD diagnoses, professionals need relevant knowledge and self-confi-dence regarding specific ASD symptoms and comorbidities. Otherwise, early diagnosis and good prognosis may be compromised (Atun-Einy & Ben-Sasson, 2018; Bakare et al., 2009) and children’s rights to development and survival are abused.

1.2 Children’s rights

Children (persons below the age of 18 years) have a right to life, survival, and development (United Nations, 1989; United Nations, 2006). And since they, particularly those in need of special support, are a vulnerable group, human rights ought to be at the centre of inter-ventions (Salberg et al., 2020). That is simply because to need special support, as Sandberg & Ottosson (2010) argue, typically means that a child is identified as having a recognised disability, medical condition or is at a psychosocial risk; hence the child needs assistance in socially connecting with peers, and exposure to stimulations that boost their develop-ment. Children with ASD particularly need support with engaging in social interactions because they have difficulties in social communication as the description of symptoms in a previous subsection indicated.

Efforts have been made towards upholding the rights and supporting children with ASD due to increased prevalence of ASD over the recent decades. For instance, tools for eval-uating ASD knowledge, creating awareness, early screening, and intervention among healthcare professionals have been developed. Bakare et al., 2008, American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Magán-Maganto et al., 2017; Eray & Murat, 2017; Campisi et al., 2018; and James & Smith, 2020 have all reported about this. Some of the tools include the

knowledge about childhood autism among health workers (KCAHW) questionnaire by Bakare et al.

(2008). It assesses baseline knowledge among community healthcare workers and subse-quently provides insight into training needs and mobilization of facilities for care towards children with ASD at primary healthcare level. The Autism survey developed by Stone (1987) has also been used by recent researchers to assess professionals’ knowledge regarding ASD. These and more are described in the method section.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Knowledge

Knowledge is defined as having a special form of “know how”, being acquainted with and being able to recognise something as true because of having correct information about it (Lehrer, 2000). According to Kohn (2019), the healthcare field employs three forms of knowledge: provider knowledge, patient knowledge and organizational knowledge. Provider knowledge consists of explicit and tacit aspects of “know-how”: the professional is re-quired to know the standard medical procedures for specific conditions, but also tap into their internal knowledge accumulated through years of practical experiences to comple-ment their knowledge. Patient knowledge simply refers to the patient’s “health status” or what the patient knows about their health condition. This is useful to providers when patients seek medical care, to determine diagnoses and treatment options. Organization knowledge includes information about health conditions generated from different sources like books and diagnostic systems and is accessible to both providers and patients.

The concept, knowledge, in this study refers to competency, awareness, and attitudes re-garding ASD symptoms and associated comorbidities. Hence all three forms are of interest to this review. Professionals acquire knowledge through both theoretical and practical training. Although education alone is not enough to effect change in the practices and behaviours of healthcare professionals, knowledge creation is a vital first step towards this change (Scott et al., 2012). Skår (2010) adds that it is essential that professionals have a theoretical backing for their actions to provide explanations for the actions and be aware of the consequences for inaction. Experiences simply bring up and affirm previously ac-quired knowledge (Skår, 2010). In relation to ASD, professionals hence need theoretical knowledge about the symptoms to identify them when a child and family seek medical help.

2.2 The theory-practice gap

To give meaning to knowledge acquisition, it is crucial that professionals utilise knowledge acquired in their clinical practice.

The concept theory-practice gap, according to Shoghi et al. (2019), has been interpreted in different ways. Using the example of nurses in their study, the authors define the concept as the difference between idealised practice and common practice; the difference between what is taught and what is applied in specific clinical settings; the difference between taught

nursing theory and its use in practice; the gap between scientific knowledge and theory used as common practice, and the gap between individual mental representations of nurs-ing and published theories of nursnurs-ing. They note that the link between knowledge and practice matters in the clinical decision-making process and suggest that bridging the gap can be done through trainings by experts from both education and clinical settings of the healthcare system.

Knowledge generated through research is what the experts pass onto other professionals whether already engaged in clinical practice still pursuing healthcare studies at colleges and universities. It is then applied in healthcare provision. This is referred to as knowledge

trans-lation - “a dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination,

ex-change and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system” (Khoddam et al., 2014, p.3). The main purpose of knowledge translation, according to Jull et al. (2017) is thus to reduce the “know–do gap” through interactive processes between researchers and those who use the knowledge, including policy decision makers, healthcare providers, funding bodies, patients, and their families.

Regarding children with ASD, bridging the theory-practice gap can lead to timely interven-tions that evidence has proven to influence good prognosis later in life. This, according to Imms et al. (2017) increases chances of children’s participation because to live a healthy life and experience development and learning, a child needs social interactions with, espe-cially peers. Healthcare professionals, as described in the family of Participation Related Concepts (fPRC) framework created by the same authors, constitute the external aspect of participation. Thus, aspects of participation within the individual, like activity competence and preferences are assumed to be linked to external aspects like the environment and the context in which participation takes place (Imms et al., 2017). Because participation in everyday life situations is at the core of interventions for children in need of special sup-port, professionals and caregivers ought to understand these factors that impact participa-tion to meaningfully make intervenparticipa-tion decisions (Imms et al., 2017).

2.3 Rationale

Justification for carrying out this review is the need to demonstrate knowledge regarding ASD symptoms among healthcare professionals because such knowledge is crucial for identification, timely diagnosis and care provision for children who present with these

symptoms. As previous research for instance James & Smith (2020) and Campisi et al. (2018) has shown, timely diagnoses and referrals create accessibility to relevant interven-tions that will lead to good outcomes and participation in society.

Apart from a systematic review by Coughlan et al. (2020) on identification and care for children with ASD, there is a research gap regarding a systematic literature review on the topic of knowledge on ASD symptoms among different healthcare professionals. Hence, this review can contribute towards research on the same. Findings from the study can hopefully provide relevant insight into the status of healthcare professionals and situation of children in this group. Policy makers and care providers can also get enlightened about what is indicated in research literature regarding care for children with ASD.

2.4 Purpose

The aim of this study is to describe healthcare professionals’ knowledge regarding ASD symptoms in children, and the factors that influence their level of knowledge.

3 Method

3.1 Design

The study design used for this research is a systematic literature review. It involves an orderly method of carrying out and recording the research process beginning with a defi-nition of the research aim and research question, followed by a description of the review plan, the literature search process, screening and selection of literature, analysis, and dis-cussion of findings (Jesson et al., 2011).

3.2 Literature search strategy

During the period from December 2020 and April 2021, articles were searched, firstly, as a mapping overview to establish availability of literature on the chosen topic and write the thesis plan, then purposely for relevant articles to include in the systematic literature re-view. Three databases, CINAHL, PsycINFO and PubMed were searched because they contain articles published in healthcare journals.

Phrases and keywords used included autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, knowledge, competence,

attitude, awareness, healthcare professionals, healthcare workers and healthcare providers, nurses, doctors, paediatricians, and midwives. Some were combined in the search strings with Boolean

opera-tors, AND/OR. The Population, Interest, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) framework according to Miller & Forrest (2001) was used to formulate the search strings in relation to the research purpose. For this study, only the ‘P’ (Healthcare professionals) and ‘I’ (Knowledge about Autism Spectrum Disorder in children) were used because studies on interventions and outcomes were not the objective of the review.

Choice of search strings was carried out in consultation with one of the university librarians who explained the method of narrowing down or broadening the search. The searches using broader keywords or phrases like healthcare professionals without quotation marks gen-erated some of the relevant articles that some narrow searches like nurses, doctors and

“healthcare professionals” did not. Hence a combination of search strings was considered,

which generated reasonable amounts of hits. After a review of numerous search trials in all three databases showed a repetition of the relevant articles, five search strings were considered. Appendix C contains an outline of the search strings and number of hits gen-erated for each. Figure 1 illustrates the literature search and selection process.

3.3 The inclusion and exclusion criteria

Groups of healthcare professionals of interest include non-specialist physicians, doctors, nurses, midwives, and paediatricians. Studies or results about ASD knowledge among spe-cialists in ASD management and allied health workers are excluded because they often encounter children on referral and are expected to be knowledgeable about the disorders they work with. Articles about studies concerning knowledge about different disorders but excluding knowledge regarding ASD were excluded.

Filters used in CINAHL and PsycINFO were articles published by peer reviewed journals in the English language between 2014 and 2021. The publication-year-filter was used on grounds that there was a shift from DSM-IV to DSM-5 in May 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some of these filters applied to PubMed too. Table 1 contains details. Quantitative studies were preferred for this systematic literature review because they em-ploy instruments to measure relationships between variables using numbers that can be statistically analysed (Cresswell, 2014) - in this case, knowledge level regarding ASD symp-toms among healthcare would be measured.

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Area Inclusion Exclusion

Availability Articles available in English Articles having abstracts only

Publication and study de-sign

Articles published in Peer re-viewed journals

Books, reports, disserta-tions/theses, literature re-views, qualitative studies, ar-ticles published in 2013 or earlier

Population Healthcare professionals Specialists in ASD and other mental disorders, al-lied health professionals, parents, and students Interest Knowledge regarding ASD in

children

Studies that excluded ASD in their list of neurodevel-opmental disorders

3.4 Selection of articles

3.4.1 Screening – title and abstract

Overall, 12 articles were imported from Pubmed, 109 from PsycINFO, and 158 from CI-NAHL after application of the filters. All articles searched in PubMed were screened by title in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria before relevant ones were ex-ported into Zotero. In Rayyan, 156 articles imex-ported from Zotero and screened by title and abstract – two were duplicates. Keywords for inclusion were healthcare professionals, nurses, midwives, doctors, paediatricians, non specialists, to mention examples, while key-words to exclude articles were parents, adults, allied health workers, specialists, pharma-cists, thesis, and reviews, among others. Of the 156 articles, 147 were excluded for one of three reasons: wrong population, wrong interest, or wrong study design. Although some could have been excluded for more than one reason, only one label was allocated to each article for purposes of order. Nine articles then remained for full text screening.

3.4.2 Screening – Full text

The method and result sections of some articles showed that two of the nine articles (Gha-deri & Whatson, 2019; Shrestha & Shrestha, 2014) were regarding studies with the ‘wrong population’: the participant composition included professionals from either the allied health or the specialist group and their responses were not separately analysed. Hence only seven of the articles were included in this review. A manual search of the reference lists of the seven articles generated five more articles of which 4 were found to be relevant and thus included in the review. All together, 11 articles were used in this review. Table 2 con-tains a summary of information on the articles included while Figure 1 is an adopted ver-sion of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] (Moher et al., 2009) flowchart illustrating the literature search and selection process.

Figure 1

Modified PRISMA flowchart showing the literature search and selection processes

Articles from CINAHL, PsycINFO & PubMed into

Zotero (n = 279) Screen ing Inclu ded Eligib ilit y Iden ti ficat ion

Articles after merging duplicates

(n = 158) Articles imported

into Rayyan (n = 158) Articles screened by title

and abstract (n = 156) Records excluded (n = 147) Wrong population (n = 43) Wrong interest (n = 98)

Wrong study de-sign (n = 6) Articles screened by full

text (n = 9)

(n = )

Articles excluded for wrong popu-lation (n = 2) Studies included in quantitative synthesis (n = 7) Manual search of the 7 articles by references (n = 5) Articles included after abstract and full text screening

(n = 4) Total number of

arti-cles included

(n = 11)

Duplicates in Rayyan (n = 2)

Table 2

Summary of articles included

No. Article Country Study

de-sign Instrument used Target sample Sample size quality Article

1.

Corsano et al. (2020) Italy Mixed methods KCAHW Paediatric nurses 93 High 2.

Hayat et al. (2019) Saudi Arabia Quantitative KCAHW Specialist and non-specialist healthcare providers 98 High 3. Rohanachandra et al.

(2020) Sri Lanka Quantitative KCAHW Primary health midwives 406 High 4. Sampson & Sandra

(2018) Ghana Quantitative KCAHW Paediatric and psychiatric nurses 130 High 5.

Zhang et al. (2018) China Quantitative Adopted KCAHW Child healthcare workers in grass-roots health service institutes 265 High 6. Rohanachandra et al.

(2017) Sri Lanka Quantitative KCAHW Doctors in a tertiary care hospital 176 High 7. Effatpanah et al.

(2019) Iran Quantitative Adopted autism survey Paediatricians 122 High 8.

Van ‘t Hof et al (2020) Netherlands Quantitative AKQ-P, CAMI ques-tionnaires Youth and Family Centre physi-cians 93 High 9. Al-Farsi et al. (2016) Oman Quantitative Authors’ questionnaire General practitioners 113 High 10. Garg et al. (2014) Australia Mixed methods Authors’ questionnaire General practitioners 191 High 11. Kilinçel & Baki (2021) Turkey Quantitative

KCAHW - Turkish

version Paediatricians 145 High

Note: KCAHW – Knowledge about childhood autism among health workers, AKQ-P – The autism knowledge questionnaire - physician edition,

3.5 Data extraction

Relevant information about the 11 articles was entered into an excel spreadsheet including identification of articles, methodology, results, and discussion details, among others. See appendix A for a sample of the extraction protocol.

3.6 Quality assessment

Quality assessment of articles was done using a modified quantitative critical review form by Law et al. (1998) since nine of the studies employed quantitative and only two used mixed methods. The review form asked about eight aspects of each study: statement of the study purpose, review of relevant background literature, choice of appropriate study design and method, description of the sample and justification of the size, intervention, outcome, result analysis method and significance, and lastly, statement of limitations and practical/clinical application of the study. A sample of the critical review form is attached as appendix B.

Since this literature review did not have studies about interventions and outcomes, the two areas were not applicable. Hence the form was modified, and quality scored for questions regarding only 6 areas. Articles were of high quality if they got a YES response to at least 80% of the questions and moderate if they got at least 50%. All articles got at least 80% and were deemed of high quality and worthy of inclusion.

3.7 Data analysis

Content analysis used in Rose et al. (2015) and Riffe et al. (2019), was employed in the evaluation of results from all the 11 articles in accordance with the aim of this review. Content analysis comprises a set of procedures used for systematic and replicable analysis of relatable statements in a written, audio, video, or pictorial set of information. Steps include 1) identification of concepts relevant for the study aim like knowledge and com-petence in this case; 2) identification and selection of coding units like instruments used and factors affecting knowledge level; 3) creation of a coding scheme like numbers (or colors as applied here) to represent the units; 4) creation of a book and form (a table in this case) to enter the information; 5) carrying out the actual coding of results (usually through a computer system but was done manually in this review), and finally summarising the findings in a descriptive manner.

Grouping of findings from the articles used in this review was done based on instruments that are described in the preceding section and entered in a table (Sample in appendix D), with similar findings colour coded for easy reference.

Variables that were measured and factors cited as influencing knowledge level among healthcare professionals made up the coding scheme and were assigned different colors as exemplified below:

• Yellow for age and number of years in clinical practice

• Green for previous encounter with child with ASD and training in ASD • Light blue for basic ASD knowledge among professionals

• Red for low knowledge about ASD comorbidities • Pink for level of education source of knowledge

• Turquoise blue for nationality and country of primary qualification

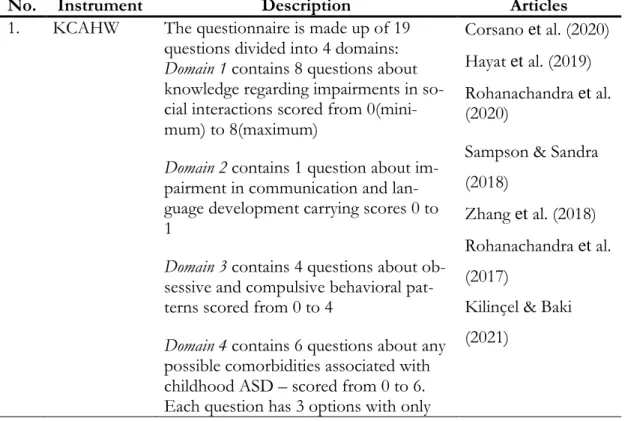

Table 3 contains a description of the instruments used in the different articles. Six of the 10 articles used the same instrument - the knowledge about childhood autism among health workers (KCAHW) while the other 4 used different instruments.

Table 3

Outline of the instruments

No. Instrument Description Articles

1. KCAHW The questionnaire is made up of 19 questions divided into 4 domains:

Domain 1 contains 8 questions about

knowledge regarding impairments in so-cial interactions scored from 0(mini-mum) to 8(maxi0(mini-mum)

Domain 2 contains 1 question about

im-pairment in communication and lan-guage development carrying scores 0 to 1

Domain 3 contains 4 questions about

ob-sessive and compulsive behavioral pat-terns scored from 0 to 4

Domain 4 contains 6 questions about any

possible comorbidities associated with childhood ASD – scored from 0 to 6. Each question has 3 options with only

Corsano et al. (2020) Hayat et al. (2019) Rohanachandra et al. (2020)

Sampson & Sandra (2018)

Zhang et al. (2018) Rohanachandra et al. (2017)

Kilinçel & Baki (2021)

one correct response scored with (1) and wrong response with (0)

2. The autism survey adopted from Stone (1987

Section 1 consisted of 16 statements

re-garding attitudes towards social/emo-tional, cognitive, and treatment/progno-sis of ASD - participants were to rate their beliefs with “agree”, “Not sure” or “Disagree”

Section 2 evaluated participants’

knowledge regarding aspects of the diag-nostic criteria for assessing ASD such as descriptors of behavior, intellect, and symptomology - response options were, ‘‘necessary’’, ‘‘helpful, but not necessary’’ or Not helpful” Effatpanah et al. (2019) 3. AKQ-P Dutch trans-lation of the CAMI ques-tionnaire

Part 1 covers 20 multiple-choice

ques-tions on general knowledge, prevalence, sex differences, and risk factors of ASD

Part 2 contains 12 physician-specific,

multiple-choice questions which evalu-ate ASD early signs, detection, diagnos-tic criteria, and comorbidity - ASD knowledge score was done on a 1–10 scale (1 = least knowledge, 10 = most knowledge).

The CAMI questionnaire is a 40-item, self-reported questionnaire used to eval-uate attitudes toward people with mental illness

van ‘t Hof et al. (2020)

4. Author’s

questionnaire Section 1 asked about the demographics of the participants

Section 2 asked about sources of

partici-pants’ knowledge of ASDs (at the begin-ning, if the participant indicated they had never heard of ‘‘autism,’’ the inter-viewer provided a brief description of ASD, and if the participant was still una-ware of ASD after the explanation, the interviewer ended the interview)

Section 3 asked about participants

atti-tudes toward the care of autistic children

Section 4 asked about physicians’

prac-tices, such as administration of diagnos-tic tests and their referral process to ap-propriate specialists”

5. Author’s

questionnaire Section A collected demographic details of participants

Section B measured relevance and

percep-tions of general practitioners about per-ceived educational needs and referral choices for children with ASD

Section C contained 14 true/false type

knowledge questions on ASDs with a cut off score of 11.

Garg et al. (2014)

Note:

KCAHW – Knowledge about childhood autism among health workers AKQ-P – The autism knowledge questionnaire - physician edition CAMI - Community Attitudes to Mental Illness

3.8 Ethical considerations

In accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki [DoH] (2013), to promote respect for persons involved in research and protect their health and rights, medical research is subject to ethical standards.

Among the studies included in this review, 10 (Corsano et al., 2020; Effatpanah et al., 2019; Hayat et al., 2019; van ‘t Hof et al., 2020; Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018; Al-Farsi et al., 2016; Rohanachandra et al., 2017; Garg et al., 2014; Kilinçel & Baki, 2021) indicated having sought ethical approval from the ethical committees while one (Sampson & Sandra, 2018) indicated that permission was sought from hospital authorities.

Secondly, eight articles (Corsano et al., 2020; Hayat et al., 2019; van ‘t Hof et al., 2020; Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018; Al-Farsi et al., 2016; Garg et al., 2014; Kilinçel & Baki, 2021) mentioned that informed consent was obtained, two (Effatpanah et al., 2019; Rohanachandra et al., 2017) did not indicate information on this, and one (Sampson & Sandra, 2018) indicated, “Not applicable”. Thirdly, eight (Corsano et al., 2020; Hayat et al., 2019; van ‘t Hof et al., 2020; Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018; Al-Farsi et al., 2016; Garg et al., 2014; Kilinçel & Baki, 2021) declared information about funding and no conflict of interest arising from the studies, while 3 (Effatpanah et al., 2019; Rohanachandra et al., 2017; Sampson & Sandra, 2018) did not.

Research ethics considered in this review include transparent documentation of the review process and declaration of any methodological bias. It can therefore be concluded that ethical considerations were made.

4 Results

Eleven articles were included in this literature review. Two articles (Corsano et al., 2020 - Italy; Garg et al., 2014 - Australia) used mixed methods while nine (Effatpanah et al., 2019 - Iran; Hayat et al., 2019 – Saudi Arabia; van ‘t Hof et al., 2020 - Netherlands; Rohana-chandra et al., 2020 – Sri Lanka; Zhang et al., 2018 - China; Al-Farsi et al., 2016 - Oman; Rohanachandra et al., 2017 – Sri Lanka; Sampson & Sandra, 2018 - Ghana; Kilinçel & Baki, 2021 - Turkey) used only quantitative methods.

Various instruments were used to measure professional’s knowledge as described in a pre-vious subsection and all articles employed the IBM SPSS software for data analysis. Results in this review were analysed using content analysis and are presented using descrip-tive tables and text. Table 4 contains mean scores based on the KCAHW questionnaire used in 7 articles (Corsano et al., 2020; Hayat et al., 2019; Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Sampson & Sandra, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Rohanachandra et al., 2017; Kilinçel & Baki, 2021). The highest mean score was 15 and the lowest was 8.82 out of 19 possible scores.

Table 4

Mean knowledge scores based on the KCAHW questionnaire Article

Sample

size Instrument Mean score

Corsano et al. (2020) 93 KCAHW 12.06 out of 19 Hayat et al. (2019) 98 KCAHW 8.82 out of 19 Rohanachandra et al.

(2020) 406 KCAHW 13.23 out of 19 Sampson & Sandra

(2018) 130 KCAHW 11.37 out of 19 Zhang et al. (2018) 265 Adopted KCAHW 7.3 out of 12 Rohanachandra et al.

(2017) 176 KCAHW 13.23 out of 19 Kilinçel & Baki

(2021) 145 KCAHW – Turkish version 15 out of 19

Overall, results from all the articles indicated that professionals had basic knowledge about ASD symptoms related to social communication and interaction, but it was low regarding repetitive and compulsive behaviour, and associated comorbidities like language and intel-lectual impairment that children with ASD commonly present with.

For instance, Rohanachandra et al. (2020) found that knowledge regarding symptoms of impairment in communication was 89 % and 52.4 % regarding the associated comorbidi-ties; Rohanachandra et al. (2017) found that over 50% (n=93) of the doctors were not aware that ASD is associated with epilepsy and 72 (40.9%) did not know that it is associated with mental retardation.

4.1 Factors affecting level of knowledge

Variations in level of ASD knowledge among healthcare professionals was influenced by age, years of work experience, previous encounter with children with ASD, nationality and country of primary qualification from medical or nursing school, level of education, source of ASD knowledge, training in ASD, beliefs and attitudes about ASD and mental illness, perceived competence, and awareness about community resources for ASD care provi-sion. Details about the extent of influence are outlined in Table 5 - while some studies showed positively significant correlations between knowledge level and the factors, others either showed no significant correlations or did not include and analyse the variables in their study; still, others showed an inverse relationship.

4.1.1 Previous encounter and work experience with ASD

Nine out of eleven articles measured and indicated a positively significant correlation be-tween knowledge level and previous encounter with a child diagnosed with or being sus-pected to have ASD. For instance, Sampson & Sandra (2018) got a significant value (p=0.01); Corsano et al. (2020) found that nurses who had worked with children with ASD had more knowledge than their colleagues; Zhang et al. (2018) found that healthcare work-ers with work experience of childhood ASD/suspected ASD had a higher KCAHW mean score than those without (8.45±1.85 vs. 6.76±2.13, P < 0.001) and Rohanachandra et al. (2020) found that 42.9 % had worked with children diagnosed as having autism and 47.3 % had had contact with a child with autism.

Five studies (Corsano et al., 2020; Hayat et al., 2019; Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018; Kilinçel & Baki, 2021) showed a positively significant correlation between knowledge level and professionals’ age and years of work experience, three (Effatpanah et al., 2019; Sampson & Sandra, 2018; Rohanachandra et al., 2017) showed no significant values, two (Garg et al., 2014; Al-Farsi et al., 2016) showed inverse relationships and one (van ‘t Hof et al., 2020) did not measure and analyse the relationship of these variables. Zhang et al. (2018) indicated (p=0.001) for knowledge level and number of years of work experience; Hayat et al. (2019) got a significant correlation (p=0.01); Corsano et al. (2020) found that nurses who were older than 30 years and those who had worked for over five years in the paediatric ward showed greater ASD knowledge. Garg et al. (2014) however found a significantly inverse relationship p-value<0.0001 for age and p-value=0.001 for work experience.

4.1.3 Nationality and country of primary qualification

The variables relating to professionals’ nationality and country of primary qualification were considered by four studies (van ‘t Hof et al., 2020; Hayat et al., 2019; Al-Farsi et al., 2016; Garg et al., 2014). Hayat et al. (2019) and Al-Farsi et al. (2016) found that profes-sionals whose nationality and primary qualification was not Saudi Arabian or Omani, re-spectively, had higher knowledge levels about ASD while van ‘t Hof et al. (2020) and Garg et al. (2014) whose studies were done in the Netherlands and Australia, respec-tively, found that the Dutch and Australian nationals and graduates had higher

knowledge levels than their counterparts. To exemplify, 64.4% of general practitioners with primary qualification from Australia achieved above cut off score while 48.8 % from other countries achieved above cut off score with p-value = 0.04.

4.1.4 Level of education and area of speciality

Level of education and area of specialization were considered by Corsano et al. (2020), Zhang et al. (2018) and Roanachandra et al. (2017), who indicated a positively significant correlation with ASD knowledge level. Zhang et al. (2018), for example, found a significant correlation (p<0.001) between knowledge level and area of specialization, with profession-als majoring in clinical medicine scoring higher than those majoring in nursing or other areas. Postgraduate vs one-degree medical officers in Roanachandra et al. (2017), and uni-versity/college level professionals vs middle vocational or high school level professionals

in Corsano et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2018) demonstrated higher levels of ASD knowledge.

4.1.5 Beliefs and attitude towards care for children with ASD

Effatpanah et al. (2019) explored professionals’ beliefs about ASD and indicated that ma-jority marked “Helpful but not necessary” for items about ASD symptoms in the DSM IV-TR and less than 50% marked “Necessary”. Al-Farsi et al. (2016) examined attitude towards care for children with ASD and beliefs about ASD and found that approximately 35% wrongly agreed to the statement “autism is more prevalent in higher socioeconomic classes” and 23% wrongly agreed to the statement “Autism is prevalent in higher educa-tional classes.” The same applied to about 32% regarding the statement “with added ma-turity, most children tend to outgrow their autistic features”. Still, some doctors, as exem-plified in the study by Effatpanah et al. (2019), indicated that diagnosis before 36 months is “unnecessary”. van ‘t Hof et al. (2020) also compared level of ASD knowledge with attitude towards people with mental illness and found that level of ASD knowledge was higher among professionals who were more compassionate and had lower levels of au-thoritarian attitudes towards people with mental illness.

4.1.6 ASD training and other knowledge sources

Rohanachandra et al. (2020) found that primary health midwives who had participated in at least one ASD training program had significantly higher knowledge than those who had not. These constituted 58.9 % (n = 239) of the sample. Al-Farsi et al. (2016) found that 89% of the general practitioners had heard about ASD, particularly from medical schools (63%), medical literature (30%), media (26%) and other sources (2%). Approximately 7% from the same study indicated that they had cases of autism in their families. Roughly 50% had seen ASD cases before graduation and another 50% had seen children with ASD after graduation (Al-Farsi et al., 2016). In the study by Kilinçel & Baki (2021), knowledge was influence by 1) completion of a child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP) internship during medical school; 2) attendance of a CAP rotation during residency and 3) attendance of a training or meeting on autism spectrum disorder. Findings showed that 59.3% (n=86) fell under category one, 60.7% (n=88) in category two, and 49.7% (n=72) in three.

Rohanachandra et al. (2020) and Rohanachandra et al. (2017) found significantly higher knowledge among primary health midwives and doctors, respectively, who perceived themselves to be competent in identifying ASD than those who did not. Rohanachandra et al. (2017) got a p-value=0.001.

4.1.8 Awareness about community resources

Garg et al. (2014) found a positively significant correlation between ASD knowledge level and awareness about community resources for ASD care provision with p-value = 0.005).

Table 5

Factors influencing knowledge

Note: xx – positively significant correlation, x – negative/inverse relationship, null – no significant correlation, n/a – not analysed Factor →

Article ↓ encounter Previous

Age and years of experience Nationality and country of primary

qualification education Level of Attitudes & beliefs specialty Area of

Awareness about community resources Training about ASD Self-perceived competence Corsano et. al. (2020) –

Italy xx xx n/a xx n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

Effatpanah et. al. (2019) –

Iran xx null n/a n/a xx n/a n/a n/a n/a

Hayat et. al. (2019) – Saudi

Arabia xx xx xx n/a n/a xx n/a n/a n/a

van ‘t Hof et. al. (2020) –

Netherlands n/a n/a xx n/a xx n/a n/a n/a n/a

Rohanachandra et. al.

(2020) – Sri Lanka xx xx n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a xx xx

Sampsom & Sandra (2018)

– Ghana xx null n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

Zhang et. al. (2018) –

China xx xx n/a xx n/a xx n/a n/a n/a

Al-Farsi et. al. (2016) –

Oman xx x xx n/a xx n/a xx xx n/a

Rohanachandra et. al.

(2017) – Sri Lanka xx null n/a xx n/a xx n/a n/a xx

Garg et. al. (2014) -

Australia xx x xx n/a n/a n/a xx n/a n/a

Kilinçel & Baki (2021) -

5 Discussion

In this section, findings from the chosen articles are discussed based on the aim: ‘To de-scribe knowledge regarding Autism Spectrum Disorder in children among healthcare professionals.’ Methodological limitations and practical implications resulting from the findings and future research recommendations are also included.

5.1 ASD knowledge among healthcare professionals

Results from the articles included indicate low knowledge among healthcare professionals regarding ASD symptoms and identification. This explains literature regarding delays in diagnosis and intervention that are attributed to professionals’ lack of competence in symptom identification (Atun-Einy & Ben-Sasson, 2018; Bakare et al., 2009).

In cases where professionals are shown to have the knowledge, differences in diagnostic practices may lead to delays in the diagnosis (Kilma, 2020; Yates & Le Couteur, 2016). For instance, although the shift from DSM-IV to DSM-5 occurred in 2013, healthcare profes-sionals still prefer to use the older manual with claims that it is more straight-forward (for example, Evers et al., 2021). Additionally, socioeconomic constraints regarding service provision in some countries and rural locations may also be contributing to some of delays in giving diagnoses, causing professionals to lean towards personal experiences and in-sights to provide care for their paediatric patients with ASD instead of evidence-based interventions (Kilma, 2020). Such factors create and increase theory-knowledge gaps in healthcare provision.

Positively significant values for ASD knowledge and age or number of years of work ex-perience are explained by exposure to ASD training and supervision during clinical practice such that having been in the field for a longer period increased chances of encounters and work with children diagnosed with or suspected to have ASD as shown in a study by Atun-Einy & Ben-Sasson (2018). Such knowledge is referred to as internal or tacit knowledge, and it complements explicit knowledge which is the second aspect of provider knowledge in healthcare service provision (Kohn, 2019). All professionals need this knowledge hands-on exposure to bridge theory-practice gaps.

There was however an inverse relationship between knowledge and age, plus number of years of work experience for studies by Garg et al., 2014 and Al-Farsi et al., 2016: younger professionals who had graduated 5 or less years earlier more than those above 5 years had heard about ASD. These inverse relationships could be explained by isolation of older

professionals since they may be separated from the teaching environment and may miss out on equal opportunities to consult and share knowledge with colleagues in the field (Rahbar et al., 2011).

Higher education level and area of specialization were also significantly correlated with higher ASD knowledge (Zhang et al, 2018; Rohanachandra et al., 2017). Countries that have policies about ensuring lifelong learning through continuous career development in the medical field, like Canada and the United Kingdom do increase chances of profession-als across all ages to develop competency in applying high quality services in their practice (Rahbar et al., 2011). Level of education can hence be increased through further studies in specialised diploma courses and postgraduate studies which consequently bridge theory-practice gaps.

Based on studies that showed significant correlations between knowledge level and pro-fessionals’ nationalities and/or country of primary qualification supports evidence that knowledge among professionals varies depending on what part of the world they come from, have acquired the health degrees from and carry out their practice (Rahbar et al., 2011). To illustrate, studies conducted in Australia (Garg et al., 2014) and Europe (Corsano et al., 2020; van ‘t Hof et al., 2020) showed more awareness and ASD knowledge among healthcare professionals than Asian and/or middle eastern (Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Rohanachandra et al.,2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Hayat et al., 2019; Effatpanah et al., 2019; Al-Farsi et al., 2016), and the African country (Sampson and Sandra, 2018). This shows a theory-practice gap among professionals in some countries and training schools might re-quire revision of their curricular to include teachings about ASD.

The studies by Rohanachandra et al. (2020), Al-Farsi et al. (2016) and Kilinçel & Baki (2021) considered the variable regarding training for professionals and confirmed the the-ory-practice gap concept. According to Rahbar et al. (2011), carrying out continuous train-ing programs could help raise awareness about ASD among older professionals in devel-oping countries, suggesting that it can be done through career development workshops or special courses across the country. For new or younger professionals, knowledge acquisi-tion is an important first step to implementaacquisi-tion of evidence-based healthcare services and bridging the theory-practice gap (Scott et al., 2012) and should be accompanied by practical strategies like internship, residencies, and mentorship programs (Shoghi et al., 2019).

In societies where mental health and disabilities (even among professionals) are accompa-nied by stigmatization, discrimination, and mythological interpretations about their causes or intervention, children are at a risk of missing timely diagnoses and interventions that can improve developmental outcomes because parents might not feel comfortable enough to seek help (Bakare et al., 2009).For instance, one reason for recommending mainstream education instead of special education for children with ASD is that they would be treated differently because of negative opinions that others have regarding children in this group (Al-Farsi et al., 2016). Hence, healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards disabilities greatly impact care provision to children in need of special support. It can be concluded that in such cases, there is a theory-practice gap.

5.2 Impact on child participation

Because studies included in this review indicate low levels of knowledge about symptoms of ASD among healthcare professionals, children are at a risk of getting late or even wrong diagnoses (Maloret and Sumner, 2014; McClain et- al., 2020). Atun-Einy & Ben-Sasson (2018) note that self-efficacy is relevant for bridging the theory-practice gap and knowledge translation because it depicts the professional’s beliefs about their ability to effectively pro-vide care for their patients. When professionals do not have the self-confidence to make diagnoses, caregivers of children with ASD are likely to also lose confidence in their health workers abilities and refrain from seeking help (Maloret and Sumner, 2014). This is partic-ularly common for children on the African continent (Bello-Mojeed et al., 2017) and cases where professionals do not know the age of earliest ASD recognition (Al-Farsi et al., 2016). Lack of self-confidence widens the theory-practice gaps in healthcare provision. To bridge the gaps, however, healthcare professionals need support from funding and policy regula-tory authorities that can foster the kinds of employee development and training mentioned in earlier subsections (Scott et al., 2012; Bakare et al., 2009). Findings from this review hence suggest that actions be taken to that end.

As shown by different studies cited throughout this review, when children with ASD do not receive relevant interventions, their chances of development and participation in soci-ety are compromised. And because children with autism often prefer withdrawal and self-isolation to maintain predictability of their surroundings, they can be at risk of suffering from anxiety and depression at life threatening degrees (Maloret and Sumner, 2014). This

is the reason why healthcare professionals need to have knowledge about ASD symptoms to make diagnoses and implement the evidence-based interventions available.

5.3 Limitations and strength of the study

One general limitation is that the article selection was not representative enough of the different continents: six (Effatpanah et al., 2019; Hayat et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018; Al-Farsi et al., 2016; Rohanachandra et al., 2020; Rohanachandra et al., 2017) were based in Asian countries, two in Europe (Corsano et al., 2020; van ‘t Hoff et al., 2020), one in Australia (Garg et al., 2014), and one (Sampson & Sandra, 2018) in an African country. Turkey (Kilinçel & Baki, 2021) falls between Europe and Asia.

5.3.1 Methodological limitations

The first methodological limitation of this review is in relation to time allocated for the process, which made it necessary for the author to limit the number of articles to complete on time. According to Jesson et al. (2911), systematic literature reviews should normally be carried out by more than one author to provide an element of objectivity in the review process. Having had one reviewer, some of the decisions made regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria, for instance, bear an element of bias and inevitable subjectivity (Jesson et al., 2011). For instance, there was a bias regarding the filter applied to the publication year based on 2013 when the shift from DSM-IV to DSM-5 took place. This risked leaving out relevant articles, making those included non-representative of research on the topic. Moreover, only two articles (Effatpanah et al., 2019; Garg et al., 2014) referred to a diag-nostic manual (DSM IV-TR). The rest did not.

Furthermore, some studies had a combination of participants, including allied health work-ers, specialists, and non-specialists yet only results about the target population were ex-tracted. This might have reduced the reliability of the results used in the review because not all articles made clear cut comparative analysis of different variables and categories of the professionals. Moreover, two of the studies (Rohanachandra et al., 2020 and Rohana-chandra et al., 2017) were done in the same country and had the same KCAHW mean score for ASD knowledge despite the sample size being more than double for one of them. The reviewer also exercised subjectivity in selection of what parts of the results to use in the review to suit the stated purpose.

5.3.2 Strength

Despite the limitations of this study, it provides a useful summary about knowledge re-garding ASD symptoms (or lack thereof) among healthcare professionals and has the po-tential to compel concerned policy makers into action towards increased knowledge re-garding interventions for children with ASD in especially developing countries.

5.4 Practical implications and future research

Considering limitations of this study, further extensive research is required that includes training and follow up programs to ensure that professionals’ need for ASD knowledge is met. Only two studies (Kilinçel & Baki, 2021; Rohanachandra et al., 2020) among the 11 that were included reported about sources of professionals’ knowledge. Future research should hence highlight more of the sources of knowledge so that they can be directly tar-geted during policy reformations, implementation, and resource distribution. For cases where schools are the main source of knowledge, policy makers can regulate the health schools’ curricular to include teachings about ASD and residence placements in paediatric wards with exposure to ASD cases. And if it is the workplaces, training programs can be incorporated into regular career development seminars workshops.

Regarding the diagnostic criteria for ASD, the study by Effatpanah et al. (2019) showed that professionals referred to it as inapplicable in developing countries though their re-sponses such as, “Helpful but not necessary”, or “Not necessary” to some of the items. The authors recommend that a more appropriate criteria for developing countries might be necessary.

Additionally, because parents or caregivers are an important part of the diagnostic process as professionals rely on their reports about the children (Ozdemir et al., 2020; Evers et al., 2021), research about their needs would provide insight into how collaborations can be improved between them and the healthcare professionals.

6 Conclusion

This systematic review set out to describe healthcare professionals’ knowledge regarding ASD symptoms in children, and the factors that influence their level of knowledge. Eleven articles were selected through a systematic process from CINAHL, PsycINFO and PubMed databases, quality assessed for ethical considerations and sampling methods

before being included herein. Findings from the studies conducted in the 11 articles were analysed using content analysis.

Six different instruments were used by the 11 studies: the KCAHW in seven and 4 other instruments like a modified autism survey and AKQ-P in the remaining four studies. All studies measured the variable of knowledge and different factors influencing it.

Results indicated some significant correlations between level of knowledge and different factors noted by the authors, including the age and number of years of work experience, previous encounter and work experience with a child suspected or diagnosed with ASD, level of education and area of specialization, training programs attended, nationalities and countries of primary qualification, beliefs and attitudes towards ASD and care for chil-dren with ASD, awareness about community resources for ASD care provision and self-perceived competence in identifying ASD symptoms in children.

The findings suggested the need to increase knowledge and ASD training among healthcare professionals especially in developing countries, because of the apparent the-ory-practice gap regarding ASD in children. For the sake of children’s welfare and partic-ipation in society, healthcare professionals need not only acquire knowledge but also have the self-confidence to apply the knowledge in their provision of healthcare services.

References

Al-Farsi, Y., Al Shafaee, M., Al-Lawati, K., Al-Sharbati, M., Al-Tamimi, M., Al-Farsi, O., Al Hinai, J., & Al-Adawi, S. (2016). Awareness about Autism among Primary Healthcare Providers in Oman: A Cross-Sectional Study. Global Journal of Health

Science, 9(6), 65–. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v9n6p65

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disor-ders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

Atun-Einy, O., & Ben-Sasson, A. (2018). Pediatric allied healthcare professionals’ knowledge and self-efficacy regarding ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum

Disor-ders, 47, 1-13. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.1016/j.rasd.2017.12.001

Bakare, M. O., Ebigbo, P. O., Agomoh, A. O., Eaton, J., Onyeama, G. M., Okonkwo, K. O., Onwukwe, J. U., Igwe, M. N., Orovwigho, A. O., & Aguocha, C. M. (2009). Knowledge about childhood autism and opinion among healthcare workers on availability of facilities and law caring for the needs and rights of children with childhood autism and other developmental disorders in Nigeria. BMC

pediat-rics, 9(12). https://doi-org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.1186/1471-2431-9-12

Bakare, M., Agomoh, A., Ebigbo, P., Eaton, J., Okonkwo, K., Onwukwe, J., & Onyeama, G. (2009). Etiological explanation, treatability, and preventability of childhood autism: a survey of Nigerian healthcare workers’ opinion. Annals of General

Psychia-try, 8(1), 6–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-8-6

Bakare, M.O., Ebigbo, P.O., Agomoh, A.O., & Menkiti, N.C. (2008). Knowledge about childhood autism among health workers (KCAHW) questionnaire: description, reliability and internal consistency. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental

Health, 4(1), 17–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-4-17

Bello-Mojeed, M., Omigbodun, O., Bakare, M., & Adewuya, A. (2017). Pattern of impair-ments and late diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among a sub-Saharan Afri-can clinical population of children in Nigeria. Global Mental Health, 4, e5–e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.30

Campisi, L., Imran, N., Nazeer, A., Skokauskas, N., & Azeem, M. W. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder. British medical bulletin, 127(1), 91–100. https://doi-org.proxy.li-brary.ju.se/10.1093/bmb/ldy026

Corsano, P., Cinotti, M., & Guidotti, L. (2020). Paediatric nurses’ knowledge and experi-ence of autism spectrum disorders: An Italian survey. Journal of Child Health Care,

Coughlan, B., Duschinsky, R., O’Connor, M., & Woolgar, M. (2020). Identifying and managing care for children with autism spectrum disorders in general practice: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Health & Social Care in the Commu-nity, 28(6), 1928–1941. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13098

Effatpanah, M., Shariatpanahi, G., Sharifi, A., Ramaghi, R., & Tavakolizadeh, R. (2019). A Preliminary Survey of Autism Knowledge and Attitude among Health Care Workers and Pediatricians in Tehran, Iran. Iranian Journal of Child Neurology, 13(2), 29–35.

Eray, S., & Murat, D. (2017). Effectiveness of autism training programme: An example from Van, Turkey. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 67(11), 1708–1713.

Evers, K., Maljaars, J., Carrington, S., Carter, A., Happé, F., Steyaert, J., Leekam, S., & Noens, I. (2021). How well are DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD represented in standardized diagnostic instruments? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01481-z

Garg, P., Lillystone, D., Dossetor, D., Kefford, C., & Chong, S. (2014). An Exploratory Survey for Understanding Perceptions, Knowledge and Educational Needs of General Practitioners (GSs) Regarding Autistic Disorders in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(7), PC01–PC09. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/8243.4527

Ghaderi, G., & Watson, S. (2019). “In Medical School, You Get Far More Training on Medical Stuff than Developmental Stuff”: Perspectives on ASD from Ontario Physicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3742-3

Hayat, A. A., Meny, A. H., Salahuddin, N., M Alnemary, F., Ahuja, K. R., & Azeem, M. W. (2019). Assessment of knowledge about childhood autism spectrum disorder among healthcare workers in Makkah- Saudi Arabia. Pakistan journal of medical

sci-ences, 35(4), 951–957. https://doi-org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.12669/pjms.35.4.605

van’t Hof, M., van Berckelaer-Onnes, I., Deen, M., Neukerk, M., Bannink, R., Daniels, A., Hoek, H., & Ester, W. (2020). Novel Insights into Autism Knowledge and Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward Mental Illness in Dutch Youth and Family Center Physicians. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(7), 1318–1330.

Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P., Steenbergen, B., Rosenbaum, P., & Gordon, A. (2017). Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of pro-cesses and outcomes in childhood disability. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 59(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13237

Jain, A., Tiwari, S., & Padickaparambil, S. (2020). Cross-Disciplinary Appraisal of Knowledge and Beliefs Regarding the Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders in India: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(3), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_163_19

James, S., & Smith, C. (2020). Early Autism Diagnosis in the Primary Care Setting.

Semi-nars in Pediatric Neurology, 35, 100827–100827.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2020.100827

Jesson, J. K., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional

and systematic techniques. Sage Publications.

Jull, J., Giles, A., & Graham, I. (2017). Community-based participatory research and inte-grated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge.

Implemen-tation Science: IS, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3

Khoddam, H., Mehrdad, N., Peyrovi, H., Kitson, A. L., Schultz, T. J., & Athlin, A. M. (2014). Knowledge translation in health care: a concept analysis. Medical journal of

the Islamic Republic of Iran, 28, 98.

Kilinçel, Ş., & Baki, F. (2021). Analysis of pediatricians’ knowledge about autism. Journal

of Surgery and Medicine, 5(2), 153–157. https://doi.org/10.28982/josam.843719

Kilmer, M. (2020). Primary care of children with autism spectrum disorders: Developing confident healthcare leaders. The Nurse Practitioner, 45(5), 41–47.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NPR.0000660352.52766.72

Kohn, M. (2019). Different types of knowledge in healthcare. https://www.kmslh.com/differ-ent-types-of-knowledge-in-healthcare/

Law, M., Stewart, D., Pollock, N., Letts, L., Bosch, J., & Westmoreland, M. (1998).

Criti-cal Review Form – Quantitative Studies. McMaster University

Lehrer, K. (1990). The analysis of knowledge. In K. Lehrer, Theory of knowledge (295). Routledge.

Magán-Maganto, M., Bejarano-Martín, Á., Fernández-Alvarez, C., Narzisi, A., García-Primo, P., Kawa, R., Posada, M., & Canal-Bedia, R. (2017). Early Detection and Intervention of ASD: A European Overview. Brain Sciences, 7(12), 159–. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7120159

Maloret, P., & Sumner, K. (2014). Understanding autism spectrum conditions. Learning

Disability Practice, 17(6), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.7748/ldp.17.6.23.e1537

Mazurek, M., Harkins, C., Menezes, M., Chan, J., Parker, R., Kuhlthau, K., & Sohl, K. (2020). Primary Care Providers’ Perceived Barriers and Needs for Support in Car-ing for Children with Autism. The Journal of Pediatrics, 221, 240–245.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.014

McClain, M., Harris, B., Haverkamp, C., Golson, M., & Schwartz, S. (2020). The ASKSP Revised (ASKSP-R) as a Measure of ASD Knowledge for Professional Populations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 998–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04321-5

Miller, S., & Forrest, J. (2001). Enhancing your practice through evidence-based decision making: PICO, learning how to ask good questions. The Journal of Evidence-Based

Dental Practice, 1(2), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1532-3382(01)70024-3

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339(7716), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Ozdemir, M., Ilgin, C., Karavus, M., Hidiroglu, S., Luleci, N., Ay, N., Sarioz, A., & Save, D. (2020). Adaptation of the Knowledge about Childhood Autism among Health Workers (KCAHW) Questionnaire: Turkish version. Northern Clinics of Istanbul,

7(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.14744/nci.2019.76301

Rahbar, M. H., Ibrahim, K., & Assassi, P. (2011). Knowledge and attitude of general prac-titioners regarding autism in Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of autism and developmental

dis-orders, 41(4), 465–474.

https://doi-org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.1007/s10803-010-1068-x

Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Fico, F., & Watson, B. (2019). Analyzing media messages: using quantitative

content analysis in research. Taylor & Francis Group.

Rohanachandra, Y., Dahanayake, D., Rohanachandra, L., & Wijetunge, G. (2017). Knowledge about diagnostic features and comorbidities of childhood autism among doctors in a tertiary care hospital. Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health, 46(1), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljch.v46i1.8093

Rohanachandra, Y., Prathapan, S., & Amarabandu, H. (2020). The knowledge of Public Health Midwives on Autism Spectrum Disorder in two selected districts of the Western Province of Sri Lanka. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 1–5.

Rose, S., Spinks, N., & Canhoto, A. I. (2015). Management Research: Applying the Principles. Routledge

Sahlberg, S., Karlsson, K., & Darcy, L. (2020). Children's rights as law in Sweden-every health-care encounter needs to meet the child's needs. Health expectations: an

inter-national journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 23(4), 860–869.

https://doi-org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.1111/hex.13060

Sampson, W., & Sandra, A. (2018). Comparative Study on Knowledge About Autism Spec-trum Disorder Among Paediatric and Psychiatric Nurses in Public Hospitals in Kumasi, Ghana. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 14(1), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901814010099

Sandberg, A., & Ottosson, L. (2010). Pre-school teachers’, other professionals’, and paren-tal concerns on cooperation in pre-school - all around children in need of special support: the Swedish perspective. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(8), 741–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504606

Scott, S., Albrecht, L., O’Leary, K., Ball, G., Hartling, L., Hofmeyer, A., Jones, C., Klassen, T., Kovacs Burns, K., Newton, A., Thompson, D., & Dryden, D. (2012). System-atic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions.

Im-plementation Science: IS, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-70

Shoghi, M., Sajadi, M., Oskuie, F., Dehnad, A., & Borimnejad, L. (2019). Strategies for bridging the theory-practice gap from the perspective of nursing experts. Heliyon, 5(9), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02503

Skår, R. (2010). Knowledge use in nursing practice: The importance of practical under-standing and personal involvement. Nurse Education Today, 30(2), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.06.012

Shrestha, M., & Shrestha, R. (2014). Symptom Recognition to Diagnosis of Autism in Ne-pal. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(6), 1483–1485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-2005-6

Stone W. L. (1987). Cross-disciplinary perspectives on autism. Journal of pediatric psychology,

12(4), 615–630. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/12.4.615

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child, 44/25 CFR. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/professionalinterest/crc.pdf

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and optional protocol. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

Will, D., Barnfather, J., & Lesley, M. (2013). Self-Perceived Autism Competency of Pri-mary Care Nurse Practitioners. Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 9(6), 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2013.02.016

World Medical Association (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Yates, K., & Le Couteur, A. (2016). Diagnosing autism/autism spectrum disorders. Paedi-atrics & child health, 26(12), 513-518. https://doi.org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.1016/j.paed.2016.08.004

Zhang, X., Xu, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Nie, X. (2018). Child healthcare workers’ knowledge about autism and attitudes towards traditional Chinese medical therapy of autism: A survey from grassroots institutes in China. Iranian journal of paediat-rics, 28(5), 1-6.https://doi.org/10.5812/ijp.60114