International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing 41 (2021) 100834

Available online 12 November 2020

1878-1241/© 2020 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

The effects of preoperative oral carbohydrate drinks on energy intake and

postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery: A pilot study

Åsa Loodin

a,b, Ami Hommel

a,b,*aDepartment of Care Science, Faculty of Health and Society, Malm¨o University, SE- 205 06, Malm¨o, Sweden bDepartment of Orthopaedics, Skåne University Hospital, 221 85, Lund, Sweden

A R T I C L E I N F O Keywords: Complications Hip fracture Nutrition Pilot study

Preoperative oral carbohydrate nutrition

A B S T R A C T

Background: Hip fractures represent a major clinical burden for patients. Studies on the effect of preoperative carbohydrate loading before different surgical interventions have shown promising results but have not been tested in patients with hip fracture.

Aim: This study aimed to investigate the effects of preoperative oral carbohydrate drinks on the postoperative energy intake and incidence of complications after hip fracture surgery.

Method: This was a pilot study using a quasi-experimental design with a control group and an intervention group. Result: The number of patients affected by more than one complication was higher in the control group than in the intervention group. According to the logistic regression analysis, the risk of any postoperative complication was reduced by approximately 50% OR (95% CI) 0.508 (0.23–1.10) in patients in the IG compared to those in the CG (p = 0.085).

Conclusion: The result of this pilot study indicated that using preoperative carbohydrate drinks can decrease the number of postoperative complications in patients with a hip fracture. Furthermore, the number of patients who meet their energy needs during the first three days postoperatively might increase. More research is needed to confirm the effect of preoperative carbohydrate drinks.

Introduction

Worldwide, hip fractures could be considered the most significant complication relationg to the morbid-mortality burden of osteoporosis (Boschitsch et al., 2017). Globally, the numbers of patients with hip fractures is expected to increase rapidly from 1.66 million in 1990 to 6.26 million by 2050 (Cooper et al., 1992). In Sweden, where the pop-ulation is 10 million, around 17500 people annually sustain a hip frac-ture (Riksh¨oft, 2018).

Hip fractures constitute a major clinical burden for patients. Osteo-porosis is the most significant underlying cause of a hip fracture after a fall (Flodin, 2015). More than 90% of patients with hip fracture are over 65 years of age and have more morbidities than the general population. Malnutrition increases the risk of complications in patients with hip fracture and those who are malnourished are at increased risk of surgical site infections, wound dehiscence, and prosthetic joint infections (Alfargieny et al., 2015; Blevins et al., 2018). Patients who struggle to recover after hip fracture surgery are often those who suffer from pre-existing problems such as frailty, cognitive deficits and risk of

malnutrition which tend to worsen following surgery. However, nurses are ideally positioned to positively impact these risk factors (Johansen et al., 2017). One study demonstrated a significant (43%) reduction in mortality in patients with hip fracture who received dietetic consulta-tion (Duncan et al., 2005).

Background

The most common medical complications among patients after hip fracture surgery are cognitive and neurological changes, cardiopulmo-nary disorders, uricardiopulmo-nary tract complications, acute kidney injuries, elec-trolytic and metabolic disorders, and pressure ulcers. These complications affect the length of hospital stay and perioperative mor-tality (Carpintero et al., 2014). If the patient is malnourished the risk of developing these complications increases (Aldebeyan et al., 2017). In order to reduce these complications, older patients with hip fracture should be offered post-operative oral nutritional supplements (Volkert, 2018). Additional reasons for extended length of stay in this population include delayed time to surgery and care in departments that lack * Corresponding author. Department of Care Science, Faculty of Health and Society, Malm¨o University, SE- 205 06, Malm¨o, Sweden.

E-mail address: Ami.Hommel@mau.se (A. Hommel).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijotnhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijotn.2020.100834

orthogeriatric skills.

The goal of care for patients with hip fracture in Sweden is that they should be operated on within 24 h of arrival at the hospital and that they should receive care in an orthopaedic department (Hommel et al., 2007, 2008). For each 10-h interval of delay before surgery, the risk of com-plications increases by 12% and for each 24-h, nursing time increases by 0.6 days (Kelly-Pettersson et al., 2017). The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) classification (ASA, 1963) provides a useful risk-stratification system for older patients with a hip fracture. This physical status classification is made on the day of surgery by the anaesthesiologist after evaluating the patient. The ASA classification has five status levels (Fig. 1) and strongly associates with medical problems after hip fracture surgery. Patients with ASA status 3 and 4 had a higher risk of medical complications than those with ASA status 2 (Donegan et al., 2010).

Complications and malnutrition

Adequate nutrition is essential if the body’s demands are to be met. Under various conditions such as trauma, sepsis and surgery, adequate nutrition is vital for healing and recovery. The key lies in systematically identifying those patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnutri-tion, and intervening promptly (Tappenden et al., 2013). Malnutrition refers to deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020) and ESPEN-guidelines recommend a range of effective interventions to support adequate nutrition and hydration in older people. These guidelines support the maintenance or improvement of nutritional sta-tus to improve the patient’s clinical outcomes and quality of life. For example, hip fracture patients should receive individually tailored, multidimensional and multidisciplinary team interventions to ensure adequate dietary intake (Volkert, 2018).

Risk factors for pressure ulcers include advanced age, confusion, inadequate nutritional intake, incontinence, and immobilisation (Swing et al., 2012). A study by Gunnarsson et al. (2009) in which nutritional supplements were administered pre- and post-operatively to patients with a hip fracture, showed a significant decrease in the incidence of pressure ulcers and care-related infections compared to a control group and a simultaneous reduction in the duration of care.

In comparison with a control group of the same age and without hip fracture, a higher proportion of patients with hip fractures were un-derweight and had a low body mass index (BMI). It has been shown that additional weight loss and loss of bone tissue and muscle mass are common even months after a hip fracture (Flodin, 2015). In a population of 218 hip fracture patients, 52% were at risk of malnutrition, 26% were malnourished and the malnutrition was associated with poor functional recovery (Miu and Lam, 2017). Malnutrition is also associated with acute confusion and risk of mortality during hospitalisation (Mazzola et al., 2017).

Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance is a metabolic state of decreased hepatic and pe-ripheral (predominantly muscle) susceptibility to insulin; this is an essential component of the regulation of changes between anabolism (reconstruction) and catabolism (degradation) (Moppet et al., 2014).

When patients about to undergo elective surgery were treated with glucose intravenously or a carbohydrate-rich drink instead of overnight fasting, insulin resistance was reduced by about half (Gustafsson et al., 2008). Insulin resistance is seen during trauma and surgery, and then remains for a few weeks postoperatively, increasing catabolism and initiating inflammatory processes. The severity of insulin resistance is directly proportional to the magnitude of the surgical procedure. It is also linked to the development of postoperative complications. Insulin resistance occurs in parallel with several other metabolic effects such as reduced muscle mass and muscle strength. The catabolic effects can be reduced by offering patients carbohydrate drinks the evening and morning before surgery. Preoperative carbohydrate drinks are effective in reducing insulin resistance in several patient groups (Moppet et al., 2014).

Preoperative preparation

The traditional method of preoperative patient preparation involves a relatively long period of fasting to reduce the real, but small, risk of lung aspiration of the stomach contents. This method means that pa-tients awaiting elective surgery fast from midnight and abstain from clear liquid from 06.00 on the day of the surgery. Emergency patients usually fast for significantly longer periods. This approach initiates a starvation process which is exacerbated by the catabolic effects of sur-gery. A pilot study showed that women with hip fractures had no pro-longed stomach dysfunction after intake of carbohydrate drinks compared to a group of elective patients undergoing total hip arthro-plasty (Hellstr¨om et al., 2017).

Enhanced Recovery after surgery

Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal evidence- based clinical pathway aiming for a faster recovery for patients under-going major surgical procedures. ERAS serves as a guide for all those involved in perioperative care, helping them to function as a well- coordinated team (ERAS, 2000). According to the ERAS Protocol (EP), patients should, for example, receive carbohydrate loading before a surgical procedure. Several studies have been conducted on preopera-tive carbohydrate loading before surgical intervention with good results (Nygren et al., 2015). However, as far as we know, the procedure has not been tested in patients with hip fracture.

Aim

This pilot study aimed to investigate the effects of preoperative oral carbohydrate drinks on the postoperative energy intake and incidence of complications after hip fracture surgery.

Method

Study design and ethical standards

This was a pilot study with focus on sample size estimation and the results from hypothesis testing should, therefore, be interpreted with caution. The method was quasi-experimental in design with a control group (CG) and an intervention group (IG). The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Council in Lund, Sweden (Dnr, 2017/577) and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 1964).

Patients

The study was conducted at a university hospital in southern Sweden on two orthopaedic care wards. Patients in the CG were included be-tween September 4, 2017 and October 24, 2017. Patients in the IG were included from November 2, 2017 to February 4, 2018. During the period between the recruitment of the CG and that of the IG, all personnel on the orthopaedic wards and the operating theatre were introduced to the

Fig. 1. Physical status classification system: American Society of

intervention.

In total 109 patients were included in the study and 59 patients completed the intervention (Fig. 2). The inclusion criteria were that the patient should: have a verified acute hip fracture; be admitted to the orthopaedic ward and scheduled for surgery within 24 h; be able to drink; be able to understand and speak Swedish or English.

When patients who met the inclusion criteria arrived at one of the orthopaedic wards, they were given written and oral information. Each patient was informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw their consent at any time without giving a reason. The information was provided by the first author or a registered nurse on the ward.

Usual care

The routines for taking food and drink preoperatively on the ortho-paedic wards followed normal care procedures, which meant no intake of solid food at least 6 h preoperatively or from 24.00 the night before surgery and no ingestion of drink 2 h preoperatively or from 06:00 on the day of the operation. Patients received parenteral infusion in the form of a glucose solution according to general or individual prescrip-tion. Each patient’s post-operative energy intake was recorded for at least three days and registered in the patient’s medical record.

Control group

Patients in the CG were cared for according to usual care procedures.

Intervention group

Patients in the IG were cared for according to the usual care pro-cedures but they also received one or two preoperative drinks, consisting of a 50 g package of powder mixed with 200 ml of water. The preop-erative drink contained 47.5 g carbohydrates/50 g and 190 Kcal. The goal was that all patients should receive two drinks. Before the patient was given the preoperative drink, the registered nurse or the first author called the operating room to ensure that at least 2 h would elapse before surgery commenced. The registered nurse or the first author mixed the drink and ensured that the patient drank it within a few minutes.

Patients who had fasted for many hours received one further drink. For example, patients who were scheduled for surgery the next day received a drink the evening before and another drink on the morning of the day of the operation. The head anaesthetist coordinated this routine within orthopaedic surgery. The intake of drinks was documented in a separate protocol and in the patient records.

Data collection

Each patient’s individual need for energy intake postoperatively was calculated using the nutritional calculation from the hospital guidelines which were based on the Swedish National Board and Welfares recom-mendation which includes age, BMI and the patient’s activity level (Socialstyrelsen 2011). The patient’s energy intake was checked per serving following the hospital calorie-counter database for the first three postoperative days. The result of BMI and energy intake calculations were documented by the registered nurse on the orthopaedic ward in the patient record. The first author conducted a journal review for each individual patient record to enable the data relating to postoperatively energy intake to be collected. The patient’s cognitive status was also documented, as well as their ASA classification. All patients without a dementia diagnosis were screened using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) which is an instrument for the assessment of organic brain deficit in older people (Pfeiffer 1975). The SPMSQ is included in the national quality register, Riksh¨oft. Data relating to postoperative complications, pressure ulcers, wound infection, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, renal failure, confusion, and other compli-cations, were obtained from the national quality register, Riksh¨oft, and the patient’s medical record. Urinary retention, sepsis, falls, candida infection, postoperative dislocation of the hip and Clostridium Difficile infection were classified as other complications.

Statistical analyses

Demographic data are reported using descriptive statistics. Gender distribution in both groups is reported as numbers and percentages. Mean and standard deviation is reported for current age, BMI and care time. ASA status is given in figures and percentages as well as the me-dian. Levin’s tests were performed to ensure equal variance in the groups. Hypothesis testing is presented with the Student T-test in com-parison with quota data and Chi-2 test on the dichotomy variables. The Mann-Witney U test was used to compare ASA statuses.

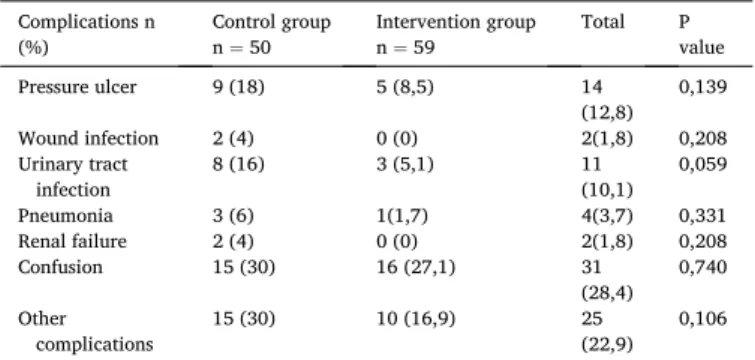

Comparative data for the CG and the IG for each complication are reported as numbers and percentages, separately. The Chi-2 test for variables was used for hypothesis testing where the number of compli-cations exceeds 5. Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the signifi-cance level of variables where the number of complications is < 5. Data relating to patients who contracted >1 complication in the CG and the IG, respectively are reported as numbers and percentages; the signifi-cance level was tested with the Chi-2 test.

A logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the rela-tionship between intake of preoperative carbohydrate and postoperative complications. Postoperative complication was the dependent variable and intake of preoperative carbohydrate drink versus no carbohydrate drink was the non-dependent variable. Odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI) (95%) are reported. Hypothesis testing was performed with Wald’s test.

All data have been processed and analysed using the SPSS version 24.0 statistics program.

The level of statistical significance for all tests performed was < 0.05. Hypothesis testing was performed to counteract the zero hypothesis, which is that there is no difference in the CG and the IG respectively regarding the number of post-operative complications, and post- operative energy requirements achieved. The hypothesis was that pa-tients in the IG are less affected by post-operative complications and that more of them achieve their postoperative energy requirement compared

to the CG. Results

Demographic data

There were no significant demographic differences between the groups (Table 1). All patients were screened for risk of malnutrition by BMI and a question about weight loss in the last six months and/or if they had problems eating. All the patients were at risk of malnutrition.

Outcomes

Of the patients included in the IG, 21 (35.6%) reached the energy intake goal during the first three postoperative days, compared to14 (28%) patients in the CG (p = 0.398). In the CG, 32 patients (53%) suffered from a complication compared to 28 patients (47%) in the IG (p =0.084). The number of patients who were affected by more than one complication was higher in the CG than in the IG. In the CG, 13 patients (26%) suffered more than one complication compared to 5 patients (8.5%) in the IG, (p = 0.014). The calculation and comparison of the number and percentages of postoperative complications are shown in Table 2. The difference regarding patients with urinary tract infection is close to the significance limit. According to the logistic regression analysis, the risk of any postoperative complication was reduced by approximately 50% OR (95% CI) 0.508 (0.23–1.10) in patients in the IG compared to those in the CG (p = 0.085).

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to investigate the effects of oral carbohydrate solution on postoperative energy intake and the postoperative compli-cation rate after hip fracture surgery. Even though we were not able to present statistically significant results, the study showed that the risk of postoperative complications related to hip fracture decreased by 50% in patients in the IG compared with those in the CG.

The number of patients affected by more than one complication was higher in the CG than in the IG, which may be due to the number of patients who met their energy requirements during the first three postoperative days being higher in the IG than the CG.

In a Swedish medical record review study by Nilsson et al. (2016) the incidence of postoperative complications in patients in the age group 18–64 years in Sweden was 13%, while in patients over 65 years it was 17%. Another Swedish study found that 15% of orthopaedic patients had at least one complication and the most common complications were care-related infections and urinary retention (Rutberg et al., 2016), in

comparison to the present study in which 26% of the patients in the CG and 8, 5% in the IG had at least one complication.

The probable explanation for the higher incidence of complications in the CG in this study is that the study by Rutberg et al. (2016) included all patients with an orthopaedic diagnosis whereas we included only patients with a hip fracture (mean age 79). However, Rutberg et al. (2016) showed that patients aged 65 years and older had more com-plications and were also more inclined to suffer from pressure ulcers than younger patients, a finding replicated by Nilsson et al. (2016). In an intervention study (Gunnarsson et al., 2009), a significant variation was observed in the postoperative development of pressure ulcers with different pre- and post-operative nutritional intakes.

In the present study, the most common complications were confu-sion, urinary tract infection and pressure ulcers. Rutberg et al. (2016) did not report the confusion which is common in hip fracture patients (Wang et al., 2018) possibly because the nurses did not detect delirium since approximately 50% of patients suffer from hypo-affective delirium. However, confusion is a lethal condition and prevention is critical. Another reason for the lack of cases of confusion in the medical records is, as Higgins et al. (2008) found, nurses often neither make nor record observations of symptoms associated with delirium as it is assigned a low priority and often delegated to junior or support workers who might not have the required expertise.

The number of patients in the present study affected by one or more complications is significantly higher than in the studies reported above. This may be related to the assessment of patients on arrival at the hos-pital according to the hoshos-pital’s risk assessment routine for malnutrition. The results of this assessment show that all patients were malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. Patients also reported problems with their intake of food and drinks during hospitalisation. A large proportion of patients also failed to reach their estimated energy intake post-operatively. Patients with a low nutrition status are more cognitively impaired than other patients, and low nutritional status is also a strong risk factor for the development of postoperative confusion (Mazzola et al., 2017) which might explain why patients in this study were prone to developing complications.

The costs of interventions aimed at increasing energy intake in pa-tients with hip fracture are relatively low compared with other medical measures (Wyers et al., 2013). Increasing patients ability to meet their energy needs can lead to faster mobilisation and recovery and reduced risk of malnutrition. This was confirmed by the results of a study of 97 patients with hip fractures, where more than half were undernourished or at risk of malnutrition, and where functional status was found to be worse not only before hip fracture but also six months postoperatively (Goisser et al., 2015). Malnutrition is associated with mortality in pa-tients with a hip fracture and nutritional intervention is associated with increased functional recovery (Malafarina et al., 2018).

In the present study, urinary retention was included among other complications. Patients in the CG were more prone to developing uri-nary retention as well as uriuri-nary tract infection than the IG patients. One reason for this might be that the recovery of IG patients was enhanced

Table 1

Demographic data of patients included in the study. Control

group Intervention group Total P value Female n (%) 33 (66) 42 (71.2) 75 (68.8) 0.718 Male n (%) 17 (34) 17 (28.8) 34 (31.2) Age - mean (S.D) 77.9 (10.5) 80.2 (11.3) 79.2

(11.0) 0.285 BMI - mean (S.D) 25.6 (4.7) 23.2 (4.8) 24.4 (4.9) 0.277 Hospital stay – mean

(S.D) 8.7 (3.0) 8.1 (2.8) 8.3 (2.9) 0.471 aASA median n 2.5 2 2 0.717 ASA1 n(%) 0 2 (3.4) 2 (1.83) ASA2 n(%) 25 (50) 29 (49.2) 54 (49.54) ASA3 n(%) 23 (46) 25 (42.4) 48 (44.04) ASA4 n(%) 2 (4) 3 (5.1) 5 (4.59)

aASA 1 = Healthy patients, ASA 2 = Mild systematic disease, ASA 3 = Severe

systematic disease, ASA 4 = Sever systematic disease - constant threat to life.

Table 2

Complications. Complications n

(%) Control group n = 50 Intervention group n = 59 Total P value Pressure ulcer 9 (18) 5 (8,5) 14 (12,8) 0,139 Wound infection 2 (4) 0 (0) 2(1,8) 0,208 Urinary tract infection 8 (16) 3 (5,1) 11 (10,1) 0,059 Pneumonia 3 (6) 1(1,7) 4(3,7) 0,331 Renal failure 2 (4) 0 (0) 2(1,8) 0,208 Confusion 15 (30) 16 (27,1) 31 (28,4) 0,740 Other complications 15 (30) 10 (16,9) 25 (22,9) 0,106

and they were mobilised more quickly postoperatively than CG patients. Risk factors for developing urinary retention are immobility and acute confusion (Wu and Bagulay, 2005). Another important factor in enhanced postoperative recovery is that the indwelling urinary catheter can be removed within a shorter time after surgery. There is an increased risk of urinary tract infection when the catheter is removed after 48 h (Fernandez and Griffiths, 2006).

In the present study more patients in the CG than in the IG were affected by pneumonia. Pneumonia is one of the leading hospital- acquired infections globally. Good oral care as well as early mobi-lisation are associated with a reduction in hospital-acquired infections (P´assaro et al., 2016). Patients in the IG had fewer hours of fasting compared to those in the CG which might have impacted on the oral cavity, reducing growth of pathogenic bacteria and decreasing the risk of pneumonia. Under-nourishment is common in patients with a hip fracture, which leads to an increased risk of postoperative complica-tions. Most studies show that calorie and protein intake is lower in geriatric patients with hip fracture than in other geriatric patients. This catabolic process in patients with hip fracture leads to weight loss and reduced muscle mass and may last up to 4 months after surgery (Malafarina et al., 2018). It is crucial to halt this catabolic process. Preoperative carbohydrate drinks reduce the degree of insulin resistance and hence limit the catabolic state.

It is well known that patients with hip fractures have difficulty in achieving their optimal nutritional intake and several interventions have been recommended to counteract this; yet the use of preoperative carbohydrate drinks remains on a small scale. In a Cochrane systematic review considering nutritional supplementation for hip fracture after-care in older people reviewd 41 trials involving 3881 participants but none of the studies involved carbohydrate oral drinks (Avenell et al., 2016). An international survey of the nursing care of patients with hip fractures, aimed at creating international guidelines, showed that 82% of hospitals record patient nutritional status but only 9% of hospitals administer preoperative carbohydrate drinks (MacDonald et al., 2018). Implementing the interventions tested in this study, the results of which show that patients have fewer complications and better energy intake, could improve nursing care for patients with hip fractures and reduce complications such as pressure ulcers, postoperative infections and cognitive impariment in a cost-effective manner. A meta-analysis has shown that intake of various types of nutritional beverages before and after surgery can help to rehabilitate patients more quickly and reduce post-operative infections and other complications (Liu, Yang u et al., 2015).

Limitations

This is a pilot study with a focus on sample size estimation and the results from hypothesis testing should be interpreted with caution. Another limitation is the quasi-experimental design that cannot elimi-nate the possibility of confounding bias which can hinder the ability to draw casual inferences. However, it was not logistically feasible to conduct a randomized control trial, so we recommend that a randomized control trial with larger sample should be conducted.

Conclusion

The result of this pilot study indicates that using preoperative car-bohydrate drinks might increase the number of patients followoing hip fracture surgery who meet their energy needs during the first three days postoperatively. Furthermore, the number of postoperative complica-tions in patients with a hip fracture might decrease. We found that the number of patients who were affected by more than one complication was significantly higher in the CG than in the IG. Even though we were not able to present a significant result, this study showed that the risk of postoperative complications decreased by 50% in patients in the IG compared to those in the CG. More research is needed to confirm the

effect of preoperative carbohydrate drinks in patients with a hip fracture.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Council in Lund, Sweden (Dnr, 2017/577) and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (The Code of Ethics, 2000).

Financial disclosure

The authors declare that they have not received benefits or financial funds in support of this study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest. References

Aldebeyan, S., Nooh, A., Aoude, A., Weber, M.H., Jarvey, E.J., 2017. Hypoalbuminaemia-a marker of malnutrition and predictor of postoperative complications and mortality after hip fractures. Injury 48, 436–440.

Alfargieny, R., Bodalal, Z., Bendardaf, R., El-Fadli, M., Langhi, S., 2015. Nutritional status as a predictive marker for surgical site infection in total joint arthroplasty. Avicenna J Med 5, 117–122.

American Society of Anesthesiologists, 1963. American society of Anesthesiologists. New classification of physical status Anesthesiology 24, 11.

Avenell, A., Smith, T.O., Curtain, J.P., Mak, J.C.S., Myint, P.K., 2016. Nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001880.pub6. Art. No.: CD001880.

Blevins, K., Aalirezaie, A., Shohat, N., Parvizi, J., 2018. Malnutrition and the development of periprosthetic joint infection in patients undergoing primary elective total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 33 (9), 2971–2975.

Boschitsch, E.P., Durchschlag, E., Dimai, H.P., 2017. Age-related prevalence of osteoporosis and fragility fractures: real-world data from an Austrian Menopause and Osteoporosis Clinic. Climacteric 20 (2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13697137.2017.1282452.

Carpintero, P., Caeiro, J.R., Carpintero, R., et al., 2014. Complications of hip fractures: a review. World J. Orthoped. 18 (4), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v5. i4.402, 5.

Cooper, C., Campion, G., Melton, LJ3rd, 1992. Hip fractures in the elderly: a worldwide projection. Osteoporos. Int. 2, 285–289.

Donegan, D.J., Gay, N., Baldwin, K., et al., 2010. Use of medical comorbidities to predict complications after hip fracture surgery in the elderly. J. Bone Joint Surg. 92 (4), 807–813. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.I.00571.

Duncan, D.G., Beck, S.J., Hood, K., Johansen, A., 2005. Using dietetic assistants to improve the outcome of hip fracture: a randomised controlled trial of nutritional support in an acute trauma ward. Age Ageing 35 (2), 148–153.

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS, 2000. Society guidelines. Retrived 2020 -07-05 from. http://erassociety.org/.

Fernandez, R.S., Griffiths, R.D., 2006. Duration of short-term indwelling-cathete-a systematic review of the evidence. J. Wound, Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 33 (2), 145–155. PMID16572014.

Flodin, L., 2015. Studies on Hip Fracture Patients: Effects of Nutrition and Rehabilitation. Doctoral Thesis. Karolinska institutet, Stockholm). Retrieved from. https://ope narchive.ki.se/xmlui/handle/10616/44572.

Goisser, S., Schrader, E., Singler, K., et al., 2015. Malnutrition according to mini nutritional assessment is associated with Severe functional impairment in geriatric patients before and up to 6 Months after hip fracture. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16 (8), 661–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.002.

Gunnarsson, A.K., L¨onn, K., Gunningberg, L., 2009. Does nutritional intervention for patients with hip fractures reduce postoperative complications and improve rehabilitation? J. Clin. Nurs. 18 (9), 1325–1333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365- 2702.2008.02673.x.

Gustafsson, U.O., Nygren, J., Thorell, A., et al., 2008. Pre-operative carbohydrate loading may be used in type 2 diabetes patients. Acta anesthesiologica scandinavica 52, 946–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01599.x.

Hellstr¨om, P.M., Samuelsson, B., Al-Ani, A.N., Hedstr¨om, M., 2017. Normal gastric emptying time of a carbohydrate-rich drink in elderly patients with acute hip fracture: a pilot study. BMC Anesthesiol. 17 (1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12871-016-0299-6.

Higgins, Y., Maries-Tillot, C., Quinton, S., Richmond, J., 2008. Promoting patient safety using an early warning scoring system. Nurs. Stand. 22 (44), 35–40. https://doi.org/ 10.7748/ns2008.07.22.44.35.c6586.

Hommel, A., Bj¨orkelund, K., Thorngren, K.G., Ulander, K., 2007. Differences in complications and length of stay between patients with a hip fracture treated in an orthopaedic department and patients treated in other hospital departments. J. Orthop. Nurs. 12 (1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joon.2007.11.00.

Hommel, A., Ulander, K., Bj¨orkelund, K., et al., 2008. Influence of optimised treatment of people with hip fracture on time to operation, length of hospital stay, reoperations and mortality within 1 year. Injury 39 (10), 1164—1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. injury.2008.01.048.

Johansen, A., Boulton, C., Hertz, K., et al., 2017. The national hip fracture database (NHFD) – using a national clinical audit to raise standards of nursing care. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing 26 (aug), 3–6. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijotn.2017.01.001.

Kelly-Pettersson, P., Samuelsson, B., Muren, O., et al., 2017. Waiting time to surgery is correlated with an increased risk of serious adverse events during hospital stay in patients with hip-fracture: a cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 69 (apr), 91–97. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.02.003.

Liu, M., Yang, J., Yu, X., Huang, et al., 2015. The role of perioperative oral nutritional supplementation in elderly patients after hip surgery. Clin. Interv. Aging 11 (10), 849–858. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S74951.

MacDonald, V., Butler Maher, A., Mainz, H., et al., 2018. Developing and testing a n international audit of nursing quality indicators for older adults with fragility hip fracture. Orthop. Nurs. 37 (2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1097/

NOR.0000000000000431.

Malafarina, V., Reginster, J.Y., Cabrerizo, S., et al., 2018. Nutritional status and nutritional treatment are related to outcomes and mortality in older adults with hip fracture. Nutrients 10 (5), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10050555. Mazzola, P., Ward, L., Zazzetta, S., et al., 2017. Association between preoperative

malnutrition and postoperative delirium after hip fracture surgery in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65 (6), 1222–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14764. Miu, K.Y., Lam, P.S., 2017. Effects of nutritional status on 6-month outcome of hip

fracture in elderly patients. Annals of Rehabilitation medicine 41 (6), 1005–1012.

https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2017.41.6.1005.

Moppet, K., Greenhaff, P., Ollivere, B., et al., 2014. Pre-Operative nutrition in Neck of femur Trial (POINT) - carbohydrate loading in patients with fragility hip fracture: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trialsjournal 15 (dec). https://doi. org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-475.

Nilsson, L., Risberg, M.B., Montgomery, A., et al., 2016. Preventable Adverse events in surgical care in Sweden: a nationwide review of patient notes. Medicine 95 (11).

https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003047.

Nygren, J., Thorell, A., Ljungqvist, O., 2015. Preoperative oral carbohydrate therapy. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 28 (3), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/

ACO.0000000000000192.

P´assaro, L., Harbarth, S., Landelle, C., 2016. Prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonia in non-ventilated adult patients: a narrative review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Contr. 5 (43), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-016-0150-3.

Pfeiffer, E.A., 1975. A short portable mental status questionnarie for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 23 (10), 433–441.

Riksh¨oft, 2018. Annual Report (In Swedish), ISBN 978-91-88017-27-7. Lund. Rutberg, H., Borgstedt-Risberg, M., Gustafson, P., et al., 2016. Adverse events in

orthopedic care identified via the Global Trigger Tool in Sweden – implications on preventable. Patient Saf. Surg. 10 (23) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-016-0112-y.

Socialstyrelsen, 2011. N¨aring F¨or God Vård Och Omsorg. En V¨agledning F¨or Att F¨orebygga Och Behandla Undern¨aring, ISBN 978-91-86885-39-7 (In Swedish). Swing, E., Gunningberg, L., H¨ogman, M., Mamhidir, A.G., 2012. Registered nurses

attention to a perceptions of pressure ulcer prevention in hospital setting. J. Clin. Nurs. 21 (9–10), 1293–1303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04000.x. Tappenden, K.A., Quatrara, B., Parkhurst, M.L., et al., 2013. Critical role of nutrition in

impoving quality of care: an interdiciplinary call to action to address adult hospital malnutrition. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 113 (9), 1219–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jand.2013.05.015.

The code of Ethics of the world medical association (declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. EC Directive 86/609/EEC for animal experiments.

http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/.

Volkert, D., et al., 2018. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition 38 (1), 10–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. clnu.2018.05.024. Epub 2018 Jun 18.

Wang, C.G., Qin, Y.F., Wan, Xet al., 2018. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative delirium in the elderly patients with hip fracture. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 13 (1)

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0897-8.

World Health Organization, 2020. Malnutrition. Retrieved 2020-07-05 from.

https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_1.

World Medical Association, 1964. Ethical principles for medical research involving human Subjects. Helsinki Finland Retrieved 2020-07-05 from. https://www.wma.ne t/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-resea rch-involving-human-subjects/.

Wu, J., Baguley, I.J., 2005. Urinary retention in a general rehabilitation unit: prevalence, Clinical outcome, and the Role of Screening. Archives of physical medicin and rehabilitation 86 (9), 1772–1777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.012. Wyers, C.E., Reijven, P.L., Evers, S.M., et al., 2013. Cost-effectiveness of nutritional intervention in elderly subjects after hip fracture. A randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos. Int. 24 (1), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2009-7.