ZORAN VASILJEVIC

Ambulatory Risk Assessment

and Intervention in the

Prison Services

Using Interactive Voice Response to assess and intervene

on acute dynamic risk among prisoners on parole

MALMÖ UNIVERSIT Y HEAL TH AND SOCIET Y DOCT OR AL DISSERT A TION 20 1 8:2 ZOR AN V ASILJEVIC MALMÖ UNIVERSIT AMBUL A TOR Y RISK ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTION IN THE PRISON SERVICES

A M B U L A T O R Y R I S K A S S E S S M E N T A N D I N T E R V E N T I O N I N T H E P R I S O N S E R V I C E S

Malmö University

Health and Society, Doctoral Dissertation 2018:2

© Zoran Vasiljevic 2018 ISBN 978-91-7104-896-7 (print) ISBN 978-91-7104-897-4 (pdf) ISSN 1653-5383

ZORAN VASILJEVIC

Ambulatory Risk Assessment and

Intervention in the Prison Services

Using Interactive Voice Response to assess and intervene on acute

dynamic risk among prisoners on parole

Malmö University, 2018

Faculty of Health and Society

This publication is also available at: www.mah.se/muep

CONTENTS

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ... 9

ABSTRACT ... 10

INTRODUCTION ... 11

BACKGROUND ... 13

The Swedish Prison System ... 13

Organisation ... 13

Clients ... 13

Preparation for release ... 14

Criminal recidivism and re- entry to society ... 15

Recidivism risk assessment and management ... 15

Current practice – risk, need, and responsivity ... 16

Acute dynamic risk factors ... 18

Ambulatory assessment and intervention ... 21

Interactive Voice Response and personalised feedback intervention ... 22

A stress- theoretical perspective on criminal recidivism ... 24

AIMS ... 26 Specific aims ... 26 METHODS ... 27 Study design ... 27 Procedure ... 27 Measures ... 28

Acute risk factors ... 28

Stable risk factors ... 29

Intervention ... 31

Sample ... 32

Statistical analysis ... 34

Ethics ... 34

RESULTS ... 35

Response rates and baseline problem severity ... 35

Response rates ... 35

Baseline problem severity ... 36

Intervention effect ... 36

Predictive ability of acute and stable risk factors ... 37

Incremental validity of acute risk factors ... 37

DISCUSSION ... 39

Methodological considerations limitations ... 40

Implications and future directions ... 44

Conclusion ... 47

POPULÄR VETENSKAPLIG SAMMANFATTNING ... 48

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... 49

REFERENCES ... 51

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

The thesis is based on the following papers, referred to in the text using the Roman numerals I-IV. The papers have been reprinted with permission from the publishers.

I. Andersson, C., Vasiljevic, Z., Höglund, P., Öjehagen, A., Berglund, M., (2014) Daily automated telephone assessment and intervention improved 1-month outcome in paroled offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. Published online.

II. Vasiljevic, Z., Berglund, M., Höglund, P., Öjehagen, A., (2017) Daily Assessment of Acute Dynamic Risk: Prediction, Predictive Accuracy and Intervention. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24, 715-729.

III. Vasiljevic, Z., Öjehagen, A., Andersson, C., (2017) Using self-report inventories to assess recidivism risk among prisoners about to be released on parole supervision. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Crime and Crime Prevention, 19, 191-199.

IV. Vasiljevic, Z., Öjehagen, A., Andersson, C., (2018) Incremental validity of ambulatory assessment of acute dynamic risk in predicting time to recidivism among paroled offenders. Manuscript.

ABSTRACT

The transition from prison to society is a challenging period for offenders released from prison. Recidivism rates are high, and the offender’s situation can change rapidly. Advances in technology in recent decades have provided new ways for correctional agencies to provide the level of supervision and immediacy needed to help prisoners to successfully re-enter society. One such area of advance is the widespread use of mobile phones and related developments in communication technologies, such as Interactive Voice Response (IVR), an automated telephony system. The overall aim of this thesis is to investigate the feasibility of using IVR to assess recidivism risk and intervene on everyday stress-related acute risk factors for crime among prisoners on parole. Paroled offenders (N=108) performed daily assessment during their first 30 days after leaving prison. Before release, they also completed a baseline assessment of stable risk factors, including personality, substance use problems, and mental health problems. Data on criminal recidivism one year following parole was collected from the Swedish Prison and Parole Service. After release, all subjects were called daily and answered assessment questions. Based on the content of their daily assessments, subjects in the intervention group received immediate feedback and a recommendation by automated telephony, and their probation officers also received a daily report by email. Although the intervention had no effect on criminal recidivism, the intervention group showed greater improvement than the control group on several of the acute dynamic risk factors studied. Several of these factors could predict criminal recidivism with marginal accuracy, and could provide incremental predictive validity beyond the baseline risk level of stable risk factors, i.e. problematic drug use and impulsiveness trait. In conclusion, IVR may be a feasible way to assess and intervene on daily stress-related acute dynamic risk factors among prisoners on parole.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades the number of incarcerated offenders around the world has increased greatly (Jacobson, Heard, & Fair, 2017). As a result of this increase, more offenders are being released to the community under supervision. Studies investigating recidivism rates among offenders released under supervision indicate that that the prison and probation services may not be effectively managing this group of offenders (Fazel, & Wolf, 2015).

The management of offenders who are released back into the community following completion of their prison sentence holds several challenges for the criminal justice agencies involved. Key challenges include protection of the public, identification of offenders with a higher risk of offending, provision of effective instruments for monitoring and controlling such offenders, and implementation of intervention and support that facilitates the reintegration process (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).

The transition from prison to society supervision is a particularly challenging period for released offenders (Petersillia, 2003). It is a period marked by potentially high levels of stress, where offenders must cope with a number of challenges (Zamble & Qunsiey, 1997). Recidivism rates are high, and many offenders return to prison within the first year of their release (Fazel, & Wolf, 2015). However, criminal justice resources are limited, and parole officers often lack the time to monitor and support released offenders in an efficient way (Petersillia, 2003).

Unparalleled advances in technology in recent decades have provided new ways for prison and parole agencies to provide the necessary level of supervision and immediacy to help prisoners to successfully re-enter the

community. Hand-held computers, electronic monitoring, global positioning satellites, geographical information systems, fingerprint drug test, and other methods to improve the re-entry process and increase public safety are already being implemented and tested in correctional agencies worldwide.

One new area of societal and technological advances, with possible implications for the prison and probation services, is the widespread use of mobile technology and related developments in communication technologies, such as Interactive Voice Response (IVR). IVR is an automated telephone technology system, capable of contacting individuals by telephone to facilitate data collection and deliver messages/interventions tailored to individual needs outside the clinical practice (Andersson et al., 2017). In a prison re-entry context, it provides an opportunity to assess, monitor and study highly transitory acute risk factors for crime, in real-time or close to real-time, and to deliver interventions to released prisoners based on their needs.

To date, there has been no research on the applicability and feasibility of using mobile technology, such as IVR, to assess and intervene on daily stress-related risk factors for crime among released prisoners. This thesis aims to fill that gap. Research on acute, rapidly changing risk factors among released prisoners is extremely limited and only a few studies have been conducted. Further, little is known about the relationship between reoffending and prisoner’s emotional state, and substance use behavior, surrounding the days, weeks, months following release from prison. Such information could potentially help correctional agencies to understand how to better assist offenders during their transition to society and reduce rates of recidivism.

BACKGROUND

The Swedish Prison System

Organisation

The Swedish Prison and Probation Service is responsible for the operative management of detention facilities and enforcement of sentences in a secure, humane and efficient manner, and the work to reduce the number of repeat offences. The service is divided into six geographical regions, where each region is responsible for the operational management of the correctional units under their governance. In international comparisons, Sweden has a low number of individuals imprisoned, approximately 4500, located across 44 high-, medium- and low-security correctional institutions. More than 10,000 persons started serving prison sentences in Sweden each year during 2005-2009 (Swedish Prison and Probation Service Official Statistics, 2012). The prison population rate in Sweden is similar to that in other Scandinavian countries, 78 per 100,000 of the national population, but considerably lower than the world average (Walmsley, 2012). The average sentence time for those admitted to prison in 2016 was nine months, with the most common grounds being drug offences (24%) and theft (18%) (Swedish National Council for Crime

Prevention, 2016).

Clients

Prisoners in Sweden, as in the rest of the world, are mostly male (92%), likely to have been previously sentenced to a criminal justice penalty (56%), and are economically disadvantaged and poorly educated with inadequate employment skills (Swedish Prison and Probation Services, 2014). Epidemiological studies have constantly shown that prison populations have higher rates of mental health problems than general populations (Fazel, & Sewald, 2012; Fazel, et al., 2016). Depressions and psychosis are consistently overrepresented

among prisoners, and substance use disorders as well as personality disorders are highly prevalent upon arrival at prison (Fazel et al., 2016). In Sweden, 60% of inmates who have undergone forensic psychiatric evaluation have been diagnosed with a personality disorder, and the National Prison and Probation Administration estimates that 60 to 70% of the prisoners have severe drug use problems (Swedish National Audit Office, 2004). The drug policy of Sweden is based on zero-tolerance, resulting in imprisonment of many drug offenders as well as individuals with substance use problems.

Preparation for release

By law, correctional care in Sweden is designed to include re-socialisation of the prisoners to the community and to counteract any harmful effects of incarceration. Preparation for the inmate’s release begins on the day of admission to the prison, and the time spent in prison should, as far as possible, be devoted to reducing the risk of future recidivism (Ruggiero, Ryan & Sim, 1995).

On arrival in prison, a sentence plan is drawn up for each prisoner, based on an assessment of their criminogenic needs and associated risk (Swedish Prison

and Probation Services, 2014). The primary purpose of the sentence plan is to

identify criminogenic areas that need to be targeted to reduce the future risk of recidivism. Several treatment programmes have been developed, aimed at targeting different types of risk factors related to criminal activity, such as alcohol and drug misusers, sex offenders and men using violence against their partners. Another measure to help prepare inmates for life in society before release is the possibility of gradual release from prison. This can involve electronic tagging towards the end of the prison sentence, staying at a treatment centre, or a half-way house with special support and supervision. Sweden practises a mandatory release system, which means that offenders who are sentenced to time in prison are generally released on parole (conditional release) after they have served two-thirds of their sentence. The length of the test period, upon conditional release, is usually equal to the length of the original sentence, but at least one year. During the test period, the conditionally released person can be placed under supervision, which usually applies to those prisoners who are deemed to be at greater risk of reoffending. In 2016, approximately 8500 prisoners were conditionally released from prison, of which 3640 were placed under parole supervision (Swedish Prison and Probation Services, 2016).

Criminal recidivism and re-entry to society

Recidivism is a term that refers to recurrence of criminal behaviour within a particular follow-up period, and can include a wide range of outcomes, including re-arrest, reconviction, and reimprisonment. Although crime rates in many western countries have declined in recent years, recidivism rates among released prisoners remain at high levels. Released prisoners represent a high-risk group compared to other offenders, with recidivism rates reported to be 50% or higher in many jurisdictions around the world (Fazel, & Wolf, 2015).

In Sweden, recidivism varies greatly, with the highest rates found in paroled offenders. Of those convicted to a criminal justice penalty, about 40% commit a new crime within three years (Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, 2007). Between 2003 and 2010, an average of 70% of those released from prison were reconvicted within three years following parole (Swedish National

Council for Crime Prevention, 2010). An average of 50% of those released from

prison during the same period were reconvicted to a new criminal justice penalty, prison or probation. The risk for recidivism is highest in the days, weeks and months following release, and decreases gradually as time elapses (Petersilia, 2003).

When re-entering the community, offenders are often faced with numerous challenges, including avoiding a return to drugs and crime, obtaining residence, finding employment, and coping with disappointments, frustration and stigma (Seal et al., 2007). Offenders often have physical and mental health problems, which should be addressed while on supervision in the community for optimal release outcome (Beaudette, Power, & Stewart, 2015). Given that initial release is a high-risk period, (Petersilia, 2003; Brown, St. Amand, & Zamble, 2009), many advocate that intensive services and surveillance should be implemented immediately following release from prison (Serin, 2017). However, correctional resources are limited and there are few rehabilitative resources available for offenders released from prison, especially for those with mental health needs (Draine, Salzer, Culhane, & Hadeley, 2008).

Recidivism risk assessment and management

Correctional agencies have a long history of assessing risk in an attempt to make release decisions more rational and accurate in terms of recidivism prediction. Early generations of risk assessment were based on unstructured clinical judgments, which were highly susceptible to biases (Andrews & Bonta,

2010). In the 1970s, researchers developed a second generations of risk scales; by using easily accessible demographic and criminal history variables – unchanging, static variables that could be easily drawn from a file review – researchers were able to demonstrate greater predictive accuracy than unstructured approaches (Campbell, French, & Gendreau, 2009). However, opposition developed to measurement of recidivism risk only using static risk factors, mainly because they do not permit measurement of changes in risk over time and thereby fail to identify areas of intervention (Andrewa & Bonta, 2010). In contrast to early risk assessment procedures, third and fourth generation risk assessment includes dynamic, i.e. changeable, risk factors to assess change in risk over time. Some dynamic factors are stable, tending to change slowly over long periods of time (e.g. impulsivity, substance abuse), while others are acute and can change rapidly over short time intervals of weeks, days or even hours (e.g. stress, drug and alcohol intoxication) (Hanson & Harris, 2000).

Current practice – risk, need, and responsivity

Modern risk/need assessments and treatment approaches are designed in accordance with the three principles of effective correctional intervention: risk (matching service intensity to level of risk), need (targeting dynamic criminogenic needs), and responsivity (adapting services/treatment based on cognitive-behavioural techniques to each client’s cognitive ability, motivation, cultural understanding, and interpersonal characteristics), also known as the RNR model (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).

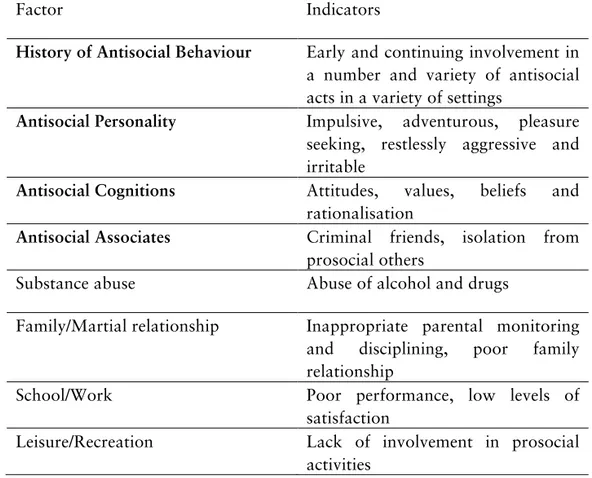

RNR is a theoretical model that outlines both the central causes of persistent criminal behaviour and some basic principles on how criminal recidivism can be reduced (Polaschek, 2012). The model includes a hierarchy of Central Eight risk factors intended to predict recidivism and identify appropriate targets for rehabilitation programmes (see Table 1) (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).1 The Big Four risk factors (history of antisocial behaviour, antisocial personality pattern, antisocial cognition, and antisocial associates) are risk factors that strongly predict criminal recidivism. The Moderate Four risk factors (family/martial circumstances, school/work, leisure/recreation, and substance abuse) have additional, but weaker, impact on the predictive validity for recidivism.

1 Within the context of risk assessment, dynamic risk factors are often referred to as criminogenic needs, because of their empirical ties to criminal behaviour (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).

Beside the central eight risk/need factors, additional needs, such as mental health problems, have been identified as being important to address among prisoners to facilitate the re-entry process and reduce rates of criminal recidivism (Baillargeon et al., 2009). However, research results vary as to whether mental health problems are associated with an increased risk of recidivism (Bonta, Law, & Hanson, 1998). While mental health problems are not identified as a criminogenic need in the RNR model, it has been incorporated as a responsivity factor because it can interfere with the effectiveness of treatments for the Central Eight factors (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).

Table 1. Central Eight factors and their indicators

Factor Indicators

History of Antisocial Behaviour Early and continuing involvement in a number and variety of antisocial acts in a variety of settings

Antisocial Personality Impulsive, adventurous, pleasure seeking, restlessly aggressive and irritable

Antisocial Cognitions Attitudes, values, beliefs and

rationalisation

Antisocial Associates Criminal friends, isolation from prosocial others

Substance abuse Abuse of alcohol and drugs

Family/Martial relationship Inappropriate parental monitoring and disciplining, poor family relationship

School/Work Poor performance, low levels of

satisfaction

Leisure/Recreation Lack of involvement in prosocial

To improve the validity and efficacy of recidivism risk decision-making, many structured risk instruments have been developed in accordance with the RNR principle, with varying content as well as formats of assessment. Some risk instruments are designed to measure a single factor related to risk, e.g. antisocial personality pattern as measured by Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 1991; 2003). Other instruments are all-inclusive and cover most of the Central Eight criminological need factors, e.g. Level of Supervision Inventory-Revised (LSI-R; Andrews & Bonta, 1995). The most commonly used formats for the assessment of risk include file review methods (e.g. Violence Risk Appraisal Guide, VRAG; Harris et al., 1993), file review combined with interview (e.g. Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management Violence Risk Assessment Scheme, HCR-20; Webster, Douglas, Eaves, & Hart, 1997), and self-report measures (e.g. Personality Assessment Inventory, PAI; Morey, 1991).

In general, meta-analytical studies support the RNR principles for the prediction as well as reduction of criminal recidivism among different types of offenders (Andrews & Dowden, 2005, 2006). The most commonly used risk instruments are moderately accurate in predicting recidivism, and can identify 65-75% of the recidivist group (Daffern, 2007). Interventions/treatment programmes that are most likely to improve offender outcomes, such as by reducing recidivism, are those that a) involve a continuum of care, b) provide intensive services over a longer period of time, c) select offenders that are appropriate for the services, and d) use cognitive behavioural therapeutic strategies (Mackenzie, 2000; Sherman et al., 1997).

The RNR model has been criticised on several grounds, such as only consisting of risk factors comprising relatively persistent behaviours that require long-term treatment to bring about change, i.e. stable risk factors. It may be important to alter stable risk factors to facilitate long-term changes in behaviour, and to identify absolute or relative risk, but stable risk factors are considered of limited use for making inferences about rapid changes in risk that enable effective daily management of offenders under community supervision (Serin, Chadwick, & Loyd, 2015).

Acute dynamic risk factors

More recently, a new group of dynamic risk measures has been developed, aimed at assessing rapidly changing risk factors that can be applied in case

planning and risk management in real time or close to real time (Serin, Chadwik, & Lloyd, 2015). In contrast with the RNR-model, where assessment and treatment is aimed at finding and addressing relatively persistent behaviours, assessment and interventions of fast changing risk factors are usually based on short-term goals, aimed at correcting the immediate crisis (Hendricks, & McKean, 1995). Acute, rapidly changing factors, such as stress, anger, negative mood or alcohol and drug intoxication, can signal the timing of re-offence, and are suggested to be particularly useful for monitoring risk during community supervision (Hanson & Harris, 2000). In the corrections field, examples of measures include the Inventory of Offender Risk, Needs, and Strengths (IORNS; Miller, 2006), the Service Planning Instrument (SPIn; Orbis, 2003), the Dynamic Risk Assessment of Offender Re-entry (DRAOR; Serin, 2007), and the ACUTE-2007 (Hanson, 2007).

To date, most studies conducted on acute dynamic risk factors have used single-point estimates, typically collected prior to release (e.g. Hanson & Harris, 1998; Quinsey et al., 1997). Although single-point research designs constitute a relatively quick and inexpensive way to collect data on dynamic risk factors, they are also problematic. Single-point estimates of dynamic risk function like static predictors in prediction analysis, because once they occur they cannot be changed, and do not change during the follow-up period (Douglas & Skeem, 2005).

To increase the likelihood of detecting change, particularly for dynamic variables that are expected to change rapidly, it has been recommended that researchers should employ multipoint studies with a prospective design involving at least three waves of assessment (Brown et al., 2009). With three or more occasions of measurement, more accurate – as well as more complex – estimations of change can be modelled (Whiteman & Mroczek, 2007). Prospective multipoint studies on the predictive and incremental validity of changes in acute risk factors in predicting criminal recidivism have been carried out among different populations in prison and probation services, including sexual offenders with community supervision (Hanson, Harris, Scott, & Helmus, 2007), general offenders on parole (Handby, 2013), and individuals on community supervision (Brown et al., 2009; Jones, Brown, & Zamble, 2010). However, the research is extremely limited and attempts to

identify significant acute dynamic factors have produced inconsistent results. In studies analysing predictive accuracy, low to marginal/moderate accuracy is reported, with the strongest prediction models usually including dynamic as well as static risk factors (Brown et al., 2009; Handby, 2013; Hanson et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2010).

A major limitation, which concerns all the multipoint studies carried out among released prisoners, relates to the assessment of the acute dynamic risk factors studied. These are either assessed irregularly – where the time gap between assessments varies between one week and several months (Handby, 2013; Hanson et al., 2007) – or assessed at regular but infrequent intervals, e.g. 1, 3 and 6 months after release (Jones et al., 2010). The infrequent assessment of risk factors that are supposed to change rapidly makes continuous risk management difficult. The longer the interval between the assessments, the greater the risk that changes will be missed; assessments that fail to estimate the rate of change will miss increases and decreases in the risk state, including those associated with intervention (Douglas & Skeem, 2005). Methodological challenges measuring acute risk factors

Gathering appropriate data for studies of rapidly changing risk factors is clinically challenging. The participants need to be tracked in the community and assessed intensively over time. Despite advances in technology in recent decades, risk assessment, as typically practiced, still relies heavily on traditional paper-and-pencil questionnaires and/or Structured Professional Judgments (SPJ), such as the Dynamic Risk Assessment of Offender Re-entry (DRAOR; Serin, 2007) or ACUTE-2007 (Hanson et al., 2007), which are usually administered by trained research assistants or by officers/practitioners working at the institution.

Assessments of this kind are limited in several ways, including reliance on patients’ retrospective self-report, the skill of the clinical interviewer/observer/file reviewer, the artificial setting of the assessment and, moreover, would make intensive assessment of constantly changing variables time-consuming and costly. The administrative burden placed on those collecting the data also has implications for the prison and probation services, where limited resources make it difficult to implement the use of constantly changing variables and extensive measures (Petersilia, 2003).

Ambulatory assessment and intervention

Ambulatory assessment (AA) covers a wide range of assessment methods, increasingly computerised, to study people in their natural environment in real time or near real time (Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2013). The real-time aspect of AA enables researchers to understand experiences as they occur, which is especially important for experiences that are transitory and often misremembered (e.g. emotions like anxiety, stress and daily substance use). AA methods of assessment include digitised methods of experience sampling (traditionally using paper-and-pencil diaries) (Stone & Shiffman, 1994), ecological momentary assessment (usually by electronic diaries or mobile phones) (Ellis-Davies et al. 2012

)

, and continued psychophysiological, biological and behaviour monitoring (Conner & Barrett 2012).AA has been widely used in clinical psychology to investigate mechanisms and dynamics of symptoms (Peeters et al., 2003), to predict the future recurrence or onset of symptoms (Wichers et al., 2010), to monitor treatment effects (Klosko et al., 1990), to predict treatment success (Wichers et al., 2012), to prevent relapse (Spaniel et al., 2008), and as interventions (Clough & Casey, 2011). Despite the growing interest in AA in many areas relevant to risk assessment, little attention has been paid to the potential benefits of AA in measuring dynamic risk factors.

Capturing data in real time may provide a great opportunity to extend psychosocial and health treatments and interventions beyond traditional research and clinical settings (Heron & Smyth, 2010). Clinicians have long tried to extend treatment into patients’ everyday lives, for example, by giving patients ‘homework assignments’ as a way to practice, generalise, and maintain skills that have been learned in a therapeutic setting (Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2004). AA offers the opportunity to bridge the gap between the client’s everyday life and the clinic by delivering treatments and interventions directly in the situations in which participants should change their behaviour (Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2013).

Such interventions can take a variety of forms, ranging from unstructured clinical recommendations (e.g. a therapist suggesting that a client perform a relaxation exercise when stressed), to more formalised and structured interventions (e.g. an individual receives a text message on their mobile phone with advice for dealing with alcohol cravings during a time when they usually

drink) (Heron & Smyth, 2010). Traditionally, clients maintain these diaries using pen and paper, but researchers and clinicians are increasingly using technology to obtain such records, including mobile telephones (Collins, Kashdan, & Gollnisch, 2003).

Interactive Voice Response and personalised feedback intervention

Recent developments in computer technology have allowed AA research to be conducted in a more appropriate, automated, and secure way by administering assessments on respondents’ telephones and storing the results immediately on a central server (Fernandez, Johnson, & Rodebaugh, 2013). One such technology is Interactive Voice Response (IVR), which uses the respondent’s telephone to administer survey questions through a pre-programmed computer. The respondent can answer each question by pressing the keys on their mobile or landline telephone keypad, and responses are immediately secured on the server and can be used for analysis and action. Several studies

have documented its utility as a device to monitor symptoms of mental health

(Andersson et al., 2014; Johansson et al., 2013; Strid et al., 2016), to study the relationship between alcohol consumption and daily stress (Andersson, Söderpalm, Berglund, 2007), and to deliver brief interventions (Andersson, 2015; Andersson, Öjehagen, Olsson, Brådvik, & Håkansson, 2017).

One of the many benefits of IVR-based systems is that they can automatically tailor AA content and provide personalised feedback and behaviour change instructions based on the individual’s assessment responses (Tucker & Grimley, 2011). Personalised feedback intervention is a brief intervention used to influence behaviour by timely monitoring and providing feedback on progress against some frame of reference (Marchica & Derevnsky, 2016). Such feedback can take a variety of forms, including ipsitative (i.e. comparing current scores to previous scores) or normative (i.e. comparing current scores to normative scores) (Musiat, Hoffman, & Scmidth, 2012). Theoretically, such information can enhance awareness of risk states and highlight discrepancies between current state and a desired state and accordingly enhance the client’s motivation to change their behaviour (Marchica & Derevnsky, 2016).

Personalised feedback about a client’s substance use is often included in Motivational Interviewing sessions (Walters et al., 2009), and incorporates components from traditional treatment approaches, such as Relapse

Prevention (Hendershot et al., 2011). For example, helping individuals to identify high-risk situations, as well as assisting clients to learn adaptive coping strategies for managing difficult situations, is a major component in Relapse Prevention (RP) (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985).1 A frequently used technique to deliver RP is brief interventions, which in their shortest form only includes assessment followed by clear feedback (Hendershot et al., 2011). Brief interventions of this kind have proved to be an effective strategy for treating individuals with substance use problems (Walters & Woodall 2003)

.

Traditionally, personalised feedback intervention was offered through a brief multicomponent in-person intervention for alcohol addiction, the efficiency of which is well established (e.g. Cronce & Larimer, 201). However, it has increasingly gained acceptance as a stand-alone intervention delivered through electronic devices (Collins et al., 2014), not only for alcohol use, but also for other problematic behaviours, such as smoking (Buller et al., 2008), illicit drug use (Andersson et al., 2017; Aharanovic et al., 2017), poor mental health (Andersson et al., 2017), and gambling (Cunningham et al., 2012).Computerised interventions are beneficial because they save time for clinicians and can deliver evidence-based content to clients in a consistent way (Kobak et al., 1997). Compared with other technologies, IVR has several advantages, including text messaging and smartphone applications. IVR calls are natural reminders, which increases the probability of response. No information is stored on the handheld device when using IVR, which is especially important when handling sensitive information, such as individuals’ mental health and substance use. Mobile phones are used in all kinds of groups, making it possible to access difficult-to-reach populations such as homeless people (Aiemagno et al., 1996), drug users (Hakansson, Isendahl, Wallin, & Berglund, 2011), and alcoholics (Alemi et al., 1994).

Although automated personalised feedback intervention has been found to be efficient in many settings, it remains an empirical question whether such interventions are feasible for offenders released from prison and whether it can reduce dynamic risk factors associated with crime, such as substance use and stress, and result in other benefits such as reduction in recidivism in crime.

1 RP is an effective cognitive-behaviour approach, designed to help individuals limit the problematic behaviour, e.g. substance use, associated with high-risk situations, such as negative affective states, during and after treatment (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985).

Given the large proportion of offenders who use drugs and alcohol and who experience problems associated with such use, and the few rehabilitative resources available in the critical time following release from prison, a low-cost intervention such as this could have a significant positive impact on the client’s health as well as public safety, if it proves effective.

A stress-theoretical perspective on criminal recidivism

One way to understand how challenges in the immediate period following release may be associated with recidivism in crime may be through a stress-theoretical framework. Stress is a well-known correlate of criminal behaviour and has a long history in the explanation of criminal behaviour (Agnew, 1992; Zamble & Qunsey, 1997). Stress is sometimes defined as the process by which an individual reacts when exposed to external or internal challenges (Fink, 2009). Although numerous theories of stress and crime have been proposed, the one used here consists of three elements: stressors, the individual makeup, and the stress response (Morse, 1998).

Stressors refer to the potential causes of stress. Stressors can be internal, e.g. strong negative emotions, or external, e.g. negative life events (Morse, 1998). External stressors can be further divided into major life events and minor everyday hassles. Major stressors are usually defined as events that require significant life re-adjustments, e.g. death of a relative, divorce, entering prison, and re-entering society following completion of a prison sentence (Pillow, Zautra, & Sandler, 1994). Minor stressors include problems of everyday life, such as traffic jams, arguments, disappointments, and financial and family concerns (Almeida, 2009).

Major and minor stressors are sometimes considered to be inseparable; for example, the transition from prison to society may be conceptualised as a series of daily hassles or adjustment difficulties following the prisoner’s physical move into society (Almeida, 2009). Upon release from prison, offenders must readjust from a highly structured environment to a highly unstructured outside world, which may include re-connecting with family and friends, finding housing and employment, staying away from drugs and crime, and coping with frustration and stigma (Seal et al, 2007).

Individual makeup refers to individual differences in vulnerability to stressors (Morse, 1998). Individuals vary greatly in how they response to different

forms of challenges, depending for example on personality, mental health problems, and substance use problems. Certain personality traits, e.g. impulsiveness, and mental health problems and substance use problems – characteristics that are common among prison populations – can make individuals more sensitive to exposure as well as reactivity to everyday stress (Zamble & Qunsiey, 1997). Previous studies on acute dynamic risk among violent offenders have suggested that individuals with mental health problems are less capable of handling stressful situations and are at higher risk of committing violent crimes when under stress (Haggård-Grann, Hallqvist, Långström, & Möller, 2006).

Stress response is the reaction to stressors and consists of emotional and behavioural components. The emotional response can for example be an anxious response that may be associated with events that pose a threat, or a depressive response that may be related to events that involve separation or loss (Gelder et al., 2006). The second feature of the stress response is coping strategies aiming to reduce the emotional response to a stressor (Gelder et al., 2006; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Coping strategies may be adaptive, i.e. problem solving oriented, or maladaptive, i.e. strategies that reduce the emotional response in the short term but result in greater long-term difficulties (Gelder et al., 2006).

Earlier research on acute dynamic risk has suggested that stressors in the time following release, as well as the offender’s coping ability, play a pivotal role in successful re-entry (Zamble & Qunsey, 1997: Brown et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2010). Many offenders have weak coping skills, and are unable to recognise and deal with problem situations, which may lead to increased stress levels and impulsive criminal reactions (Zamble & Qunsey, 1997).

AIMS

The overall aim of this study is to investigate the feasibility of using Interactive Voice Response to assess recidivism risk and intervene on everyday stress-related, i.e. acute dynamic, risk factors among prisoners on parole.

Specific aims

To investigate the effects of a brief cognitive intervention on the development of daily stress-related acute risk factors during the first month following parole (Paper I). An additional aim is to investigate the effects of a brief cognitive intervention on recidivism in crime during the first year following parole (paper II).

To investigate the predictive ability of changes in stress-related, acute dynamic risk factors (Paper II), and baseline, i.e. stable, risk factors (Paper III) in predicting recidivism in crime during the first year following parole.

To investigate whether changes in stress-related, acute dynamic risk factors provide incremental ability beyond the baseline risk assessment of impulsivity, history of problematic drug use and mental health problems, in predicting time to recidivism one year following parole (Paper IV).

METHODS

Study design

This study was a randomised trial using automated telephony in a population of general paroled offenders, who were recruited and allocated to two groups while still in prison. In both groups, acute dynamic risk factors were monitored by daily assessments during 30 consecutive days following probation. In addition to these assessments, parolees in the intervention group received daily feedback, including recommendations based on the results of these assessments, and the correctional officers received a daily report on their client’s progress. The feedback and the email report were not given to those in the control group, meaning that the feedback and the email report were the only differences between the two groups. For both groups, each call ended with a brief reminder about the next scheduled call.

Procedure

Appointed employees at 13 out of 15 open and closed prisons in the south and east administrative regions of Sweden were assigned to identify all prisoners scheduled to leave prison on probation between December 2009 and August 2010. All participants were assigned a probation officer, had access to a mobile phone, and were sufficiently fluent in Swedish.

Before probation, eligible participants were scheduled for a meeting with the research group. Participants were told that registry data on criminal recidivism for one year following probation would be collected from the Prison and Probation Service, that participants could withdraw consent at any time, and that such withdrawal would result in their assessments being excluded. After written informed consent was obtained, the participants registered their probation date and mobile phone number into the automated telephone

system, and responded to a baseline assessment including personality, substance use problems, and mental health problems, and the same measurements that were later used during the follow-up period.

At registration, the participants were randomised into two groups. The automated telephone system was then programmed to call all participants, starting the day after release – Day 1 – and continuing with daily assessments for 30 consecutive days. Attempts were made to reach participants every two hours between 12 p.m. and 9 p.m. during the follow-up period, i.e. Days 1 to 30. If contact was established, the automated telephone system collected follow-up data from the participant, and those randomised into the intervention group were given a brief feedback intervention that included recommendations, after which the call ended. After each assessment, the automated telephone system emailed a brief report to the assigned probation officer for those in the intervention group. When all daily data had been collected, in 2014, information about criminal recidivism was collected from the Swedish Prison and Probation Service offender database.

Measures

Acute risk factors

Both the baseline assessment and the 30-day assessment of acute dynamic risk factors, assessed through automated telephony, included 7 measurements and a total of 21 items. The participants gave a numeric response for 20 of these items simply by pressing a key on the telephone keypad, while the final question was an open-ended question where the respondent gave an oral response that was recorded.

Stress was measured with the 7-item Arnetz and Hasson Stress Scale (AHSS; Andersson, Johnsson, Berglund, & Öjehagen, 2009). A brief version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-8D; Fink et al., 1995) was used to assess psychiatric symptoms; subscales assessed symptoms of anxiety and depression. Two items from the Alcohol Urges Questionnaire (Bohn, Krahn, & Staehler, 1995) were used to assess cravings or urges to partake in alcohol and drugs, and the daily use of alcohol and drugs was assessed by simply asking the respondent to rate the intensity of use. Finally, assessment of daily experience (Stone & Neale, 1982) was used; participants were asked to orally record their most stressful event that day, where the severity of this event was rated on a numeric scale.

The present study only includes questions with a numeric response. For all numeric questions, responses were given on a 10-digit scale ranging from 0 (negative) to 9 (positive). The ratings in studies II and IV were reversed, meaning that a high score was considered less favourable and that improvements should result in lower scores.

The analysis included ten different variables representing the following acute dynamic risk factors: stress, psychiatric symptoms, symptoms of depression, symptoms of anxiety, urge to drink alcohol, urge to use drugs, alcohol use, drug use, and the severity of the most stressful daily event. All these variables, except the rating of most stressful daily event, were summarised to a total feedback score for 19 items, ranging from 0 (maximum positive) to 171 (maximum negative), which represents the final variable in the analysis.

Stable risk factors

Personality

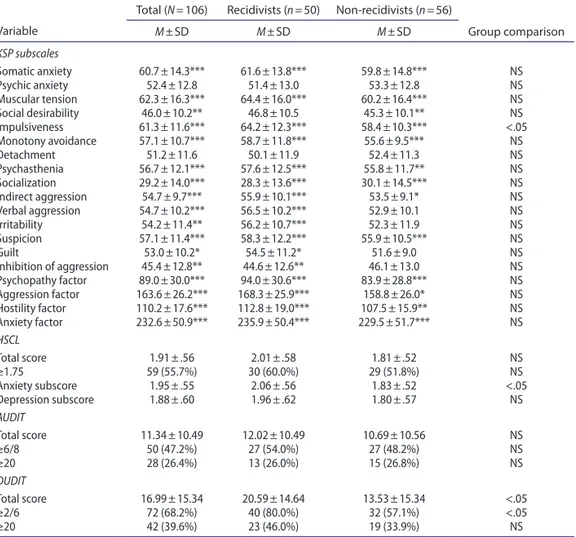

The Karolinska Scales of Personality (KSP) was used to obtain measurements of personality traits (Schalling, 1978). It is a 135-item self-report questionnaire for measurement of stable habitual behaviour and feelings on a 4-point Likert scale. The items are grouped into 15 scales: Somatic anxiety, Psychic anxiety, Muscular tension, Social desirability, Impulsiveness, Monotony avoidance, Detachment, Psychasthenia, Socialisation, Indirect aggression, Verbal aggression, Irritability, Suspicion, Guilt, and Inhibition of aggression. Four overarching factors are discerned: the Psychopathy factor (Impulsiveness + Monotony Avoidance - Socialisation scale), the Aggression factor (Indirect aggression + Verbal aggression + Irritability), the Hostility factor (Suspiciousness + Guilt), and the Anxiety-proneness factor (Somatic anxiety + Psychic anxiety + Muscular tension + Psychasthenia).

For screening of baseline problem severity, the raw scores of the KSP scales were transformed into T-scores (x – mean of healthy volunteers/SD of the healthy volunteers × 10 +50). The comparison group was drawn from the general population, having a mean T-score of 50 and a SD of 10 (Bergman, 1982). Previous studies in Swedish offender populations demonstrate differences from norms regarding most personality traits, specifically on the Socialisation scale (Longato-Stadler, von Knorring, & Hallman, 2002). The Socialisation scale was originally a delinquency scale, which together with

Impulsiveness and Monotony avoidance has been associated with antisocial and psychopathic behaviour (Schalling, 1978; Longato-Stadler et al., 2002). Mental health problems

The Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 (HSCL-25) was used to assess mental health problems (Nettelbladt, Hansson, Stefansson, Borgquist, & Nordström, 1993). It is a 25-item self-rating scale measuring the presence and intensity of symptoms of anxiety and depression, but is also considered a useful self-report measure for general mental health. The HSCL-25 consists of 25 symptoms, and for each item the respondent indicates whether they were ‘not’, ‘a little bit’, ‘quite a lot’, or ‘very much’ affected by the symptom during the previous two weeks. The mean score across all items makes up the total score, which ranges from 1 to 4, where a score of >1.75 indicates mental health problems. Alcohol use

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to measure hazardous alcohol use and probable alcohol dependency (Bergman & Källmén, 2002). It is a 10-item self-rating scale covering alcohol consumption, signs of dependence, and alcohol-related harm, and is frequently used in Swedish prison settings. The total score ranges from 0 to 40, and scores of >6 for women and >8 for men are considered as hazardous alcohol use, while an AUDIT score of 20 or higher implies a diagnosis of dependency.

Drug use

The Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) was used to measure illicit drug use and drug-related problems. The scale was originally validated in prison settings (Berman, Bergman, Palmstierna & Schlyter, 2005), since when it has been frequently used in these settings. It is an 11-item self-rating scale, with a total score range of 0-44. Drug-related problems are identified at a cut-off score of >2 for women and >6 for men, while a score of 25 or higher implies a diagnosis of dependence.

Criminal recidivism

Criminal recidivism is measured as criminal acts (all types) that resulted in reconvictions to a criminal justice sentence, prison or probation, during the one-year period following parole.

Intervention

Immediately after the daily assessments, brief feedback was given by the automated telephone system, including a recommendation to the paroled offender. At the same time, a report was sent by email to the probation officer responsible for each specific offender, according to the information provided to the probation officer at recruitment. The intervention given to the paroled offenders was very brief, consisting of only a few sentences, and lasted less than 60 s.

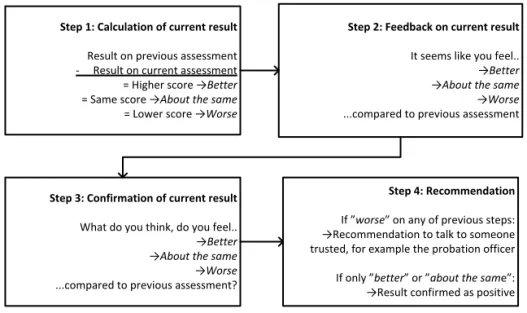

The intervention consists of four basic steps (Figure 1). The feedback and recommendation to the paroled offender were given automatically immediately after each assessment, based on a simple calculation of the direction of movement between the total score from the previous assessment compared with the total score on the current assessment (Step 1). The respondent was informed whether the result of this calculation was positive, negative, or neutral (Step 2). Then the respondent was asked whether they perceived the trend as positive, negative, or neutral (Step 3). Finally, in cases where the calculation and/or the respondent indicated a negative trend, a recommendation was given to the respondent to talk to someone trusted, for example, the probation officer (Step 4). Where the response was neutral or positive, the result was only confirmed as positive.

The intervention also included a daily report sent by email to the probation officer to enable evaluation of treatment results and to improve decisions on individual need of care. Each report included total score on each completed assessment, and information about whether the direction was positive, negative, or neutral, together with information about any missing responses. As reports only contained a summary score, the probation officer was not informed about any sensitive areas such as the use of alcohol. No data was collected on whether the probation officers actually read the daily reports.

Figure 1. Description of four basic steps used as intervention to paroled offenders

Sample

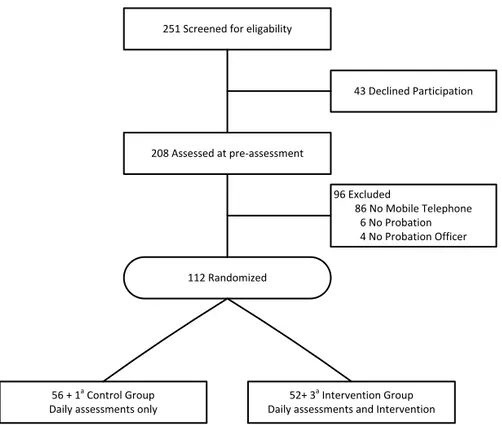

As shown in Figure 2, 251 offenders were screened for eligibility, of which 43 (17%) declined participation, and 208 were assessed at pre-assessment. Ninety-three were excluded for not fulfilling the eligibility criteria. The 112 remaining participants were randomised to two groups; one group was to be simply monitored for 30 days after probation, and the other was to be monitored and receive interventions. Four offenders, one in the control group and three in the intervention group, withdrew consent, stating that the monitoring was too intense and therefore experienced as an adverse event. These withdrawals were excluded from the data set according to informed consent approved by the institutional board.

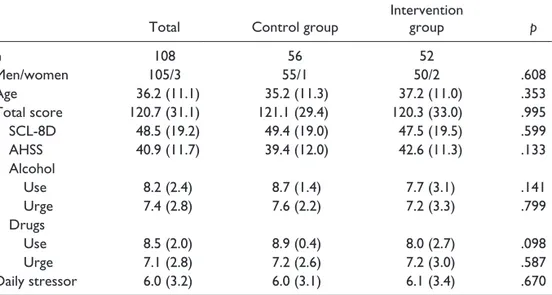

The final sample in Study I included a data set with 108 paroled offenders, 105 men and three women. At pre-assessment, the 93 subjects who were excluded for not fulfilling the eligibility criteria reported less positive scores on the item concerning the urge to consume drugs on the AHSS scale, on the total scale, and scored higher on the KSP-trait guilt, compared with the 108 subjects included in the final sample. There was no difference on the other scales, or in age and gender. Age of the participants in the final sample of 108 offenders ranged from 18 to 61, M (SD) = 36.2 (11.1) years.

Figure 2. Flow diagram showing the sample and randomization process for this randomized controlled trial.

In Study II, a total of 15 participants were excluded from the original sample, seven from the intervention group and eight from the control group. Of these, two participants (one from each group) were excluded because no follow-up data on criminal recidivism could be collected due to the death of the participant in one case and a missing personal identification number in the other. The remaining 13 participants (six from the intervention group and seven from the control group) were excluded because they responded to less than four of the follow-ups, so individual slope parameters could not be estimated.1 The final sample in Study II involved 93 paroled offenders: 45 from the original intervention group and 48 from the control group.

In study IV, an additional three subjects were excluded because they

1

The analysis for studies II and IV require at least four points in time for each individual. The number of parameters a growth model can estimate is one less than the number of occasions (n-1). In a linear model with one covariate, there will be three estimates – one slope, one intercept, and the covariate – so at least four points in time are needed.

Figure 1.

Step 1: Calculation of current result Result on previous assessment -‐ Result on current assessment = Higher score →Better = Same score →About the same = Lower score →Worse

Step 2: Feedback on current result It seems like you feel.. →Better →About the same →Worse ...compared to previous assessment

Step 3: Confirmation of current result What do you think, do you feel.. →Better →About the same →Worse ...compared to previous assessment?

Step 4: Recommendation If ”worse” on any of previous steps: →Recommendation to talk to someone trusted, for example the probation officer If only ”better” or ”about the same”: →Result confirmed as positive

Figure 2

251 Screened for eligability

208 Assessed at pre-‐assessment

43 Declined Participation

112 Randomized

96 Excluded

86 No Mobile Telephone 6 No Probation 4 No Probation Officer

Figure 1. Description of four basic steps used as intervention to paroled offenders

Sample

As shown in Figure 2, 251 offenders were screened for eligibility, of which 43 (17%) declined participation, and 208 were assessed at pre-assessment. Ninety-three were excluded for not fulfilling the eligibility criteria. The 112 remaining participants were randomised to two groups; one group was to be simply monitored for 30 days after probation, and the other was to be monitored and receive interventions. Four offenders, one in the control group and three in the intervention group, withdrew consent, stating that the monitoring was too intense and therefore experienced as an adverse event. These withdrawals were excluded from the data set according to informed consent approved by the institutional board.

The final sample in Study I included a data set with 108 paroled offenders, 105 men and three women. At pre-assessment, the 93 subjects who were excluded for not fulfilling the eligibility criteria reported less positive scores on the item concerning the urge to consume drugs on the AHSS scale, on the total scale, and scored higher on the KSP-trait guilt, compared with the 108 subjects included in the final sample. There was no difference on the other scales, or in age and gender. Age of the participants in the final sample of 108 offenders ranged from 18 to 61, M (SD) = 36.2 (11.1) years.

Figure 2. Flow diagram showing the sample and randomization process for this randomized controlled trial.

In Study II, a total of 15 participants were excluded from the original sample, seven from the intervention group and eight from the control group. Of these, two participants (one from each group) were excluded because no follow-up data on criminal recidivism could be collected due to the death of the participant in one case and a missing personal identification number in the other. The remaining 13 participants (six from the intervention group and seven from the control group) were excluded because they responded to less than four of the follow-ups, so individual slope parameters could not be estimated.1 The final sample in Study II involved 93 paroled offenders: 45 from the original intervention group and 48 from the control group.

In study IV, an additional three subjects were excluded because they

1

The analysis for studies II and IV require at least four points in time for each individual. The number of parameters a growth model can estimate is one less than the number of occasions (n-1). In a linear model with one covariate, there will be three estimates – one slope, one intercept, and the covariate – so at least four points in time are needed.

Figure 1.

Step 1: Calculation of current result Result on previous assessment -‐ Result on current assessment = Higher score →Better = Same score →About the same = Lower score →Worse

Step 2: Feedback on current result It seems like you feel.. →Better →About the same →Worse ...compared to previous assessment

Step 3: Confirmation of current result What do you think, do you feel.. →Better →About the same →Worse ...compared to previous assessment?

Step 4: Recommendation If ”worse” on any of previous steps: →Recommendation to talk to someone trusted, for example the probation officer If only ”better” or ”about the same”: →Result confirmed as positive

Figure 2

251 Screened for eligability

208 Assessed at pre-‐assessment

43 Declined Participation

112 Randomized

96 Excluded

86 No Mobile Telephone 6 No Probation 4 No Probation Officer

56 + 1a Control Group

Daily assessments only 52+ 3

a Intervention Group

Daily assessments and Intervention

offended within the first three days following parole, so the final sample comprised 90 offenders.1 For study III, all participants except the two with missing follow-up data on criminal recidivism were included (n = 106).

Statistical analysis

In Paper I, the outcome variables were analysed using repeated measures linear mixed-growth model, where group (intervention vs. control) and day were entered as fixed effects and subjects as random effect (intercept). For repeated measurements, an autocorrelation structure of order 1 was pre-specified. In Papers II and IV, analysing the relationship between changes in acute risk and recidivism in crime, a two-stage analytical approach was used in which a growth model was first estimated to the longitudinal data, and then the estimated values of the longitudinal trajectories for each individual were used as predictors of recidivism in crime. In Paper II, the outcome variable recidivism in crime was binary (recidivism/no recidivism), so the estimated values of the longitudinal trajectories were analysed using Poisson regression analysis with robust standard errors.2 In Paper IV the outcome variable was time to recidivism, so the longitudinal trajectories were entered in a series of Cox regression analyses.

In the analysis of baseline risk level of stable risk factors, Paper III, Poisson regression analysis with robust standard errors was used. Finally, to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the stable and acute risk factors (Paper III and Paper II respectively), in relation to one-year criminal recidivism, predictive probabilities were calculated. The predictive values were used to analyse predictive accuracy of stable and acute dynamic risk factors, by calculating the area under the receiver operator characteristic (AU-ROC).

Ethics

The studies in Papers I–IV were performed according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and were approved by the Regional Ethics Committee at Lund University, and were registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. Participants in Papers I–IV received a small reward.

1

Participation in Study IV was terminated once the prisoner had re-offended or the one-month data collection following parole had been successfully completed

.

2 In clinical trials, when the outcome variable is dichotomous and the outcome prevalence is high (>10%), a modified Poisson regression with robust standard errors is thought to be a more suitable alternative then logistic regression, if the effects estimate of interest is risk ratio (Knol, Le Cessie, Algra, Vandenbroucke, & Groenwold, 2012)

RESULTS

Response rates and baseline problem severity

Response rates

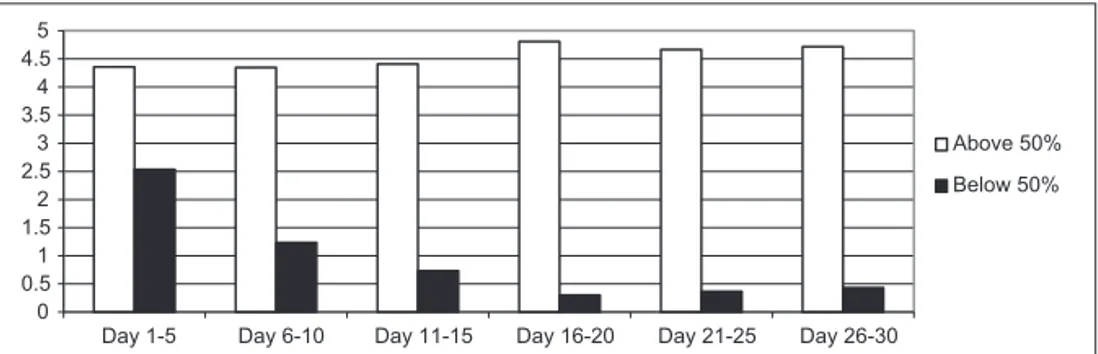

The final sample of 108 participants included in Paper I were able to respond to 30 daily follow-up assessments, resulting in 3240 possible assessments, and 2298 (70.9%) were completed. On average, offenders completed 21.3 (SD = 10.4) follow-up interviews after parole. In the total group of 108 offenders, 28 (25.9%) participated in all the follow-up interviews, and 79 (73.1%) offenders completed at least half of the telephone follow-ups. These 79 offenders completed on average 27.3 (SD = 3.5) follow-ups, compared with 5.6 (SD = 3.9) in the remaining 29 offenders. There was no difference between the two groups at baseline, while the 29 individuals who responded to less than half of the follow-ups had less favourable scores the first five days after parole for the following daily outcomes, i.e. acute risk factors: SCL-8D, alcohol use, alcohol urge, drug use, drug urge, and on the total summary scale. There were no baseline differences between the control group and intervention group on any baseline measure.

Paper II and IV included a reduced sample of 93 respectively 90 individuals. In the final sample of 93 individuals included in Paper II, baseline ratings for the most stressful daily event and daily drug use were less favourable than the corresponding ratings for those 15 participants excluded because of limited follow-up assessments (n=13) and missing data on criminal recidivism (n=2). In paper IV, after the three subjects were excluded because they re-offended within the first three days following parole, no significant differences were found on any baseline measure when comparing the final sample of 90 individuals and the 18 excluded.

Those in the final sample who committed a new crime during the first year following parole in paper II and paper IV responded to fewer daily follow-up assessments during the first month compared to those who did not commit a crime (22.2± 8.42 vs 25.7 ± 7.28, p<.05 respectively 22.5±8.31 vs. 25.7±7.28, p<.05). There were no differences in recidivism rates between those included in the final analysis and the subjects excluded in paper II and IV.

In paper III, forty-seven per cent (50 individuals out of 106) committed a new crime resulting in a return to the criminal justice system during the first year following release from prison. In paper II and IV, forty-sex per cent (43 individuals out of 93), respectively forty-fore per cent (40 out of 90) committed a new crime during the first year following release from prison.

Baseline problem severity

In comparison to healthy volunteers, the total group of prisoners (n=106) differed in all the higher-order KSP factors, where the Psychopathy factor showed the most prominent difference (paper III). The recidivist group (n=50) had higher scores on the KSP-scales for verbal aggression, irritability and guilt compared with healthy volunteers, while these differences were not found when non-recidivists (n=56) were compared with healthy volunteers. The recidivist group had higher scores on the Impulsiveness scale compared to the non-recidivist group, which was the only difference between the two groups. The results in paper III also showed high prevalence for mental health problems (55.7%), problematic drug use (68.2%) and probable drug dependence (39.6%), hazardous alcohol use (47.2%) and probable alcohol dependence (26.4%) in the total group of paroled offenders. The recidivist group had higher scores on baseline symptoms of anxiety (HSCL-25) and drug use (DUDIT), and showed a higher proportion of problematic drug use compared to the non-recidivist group.

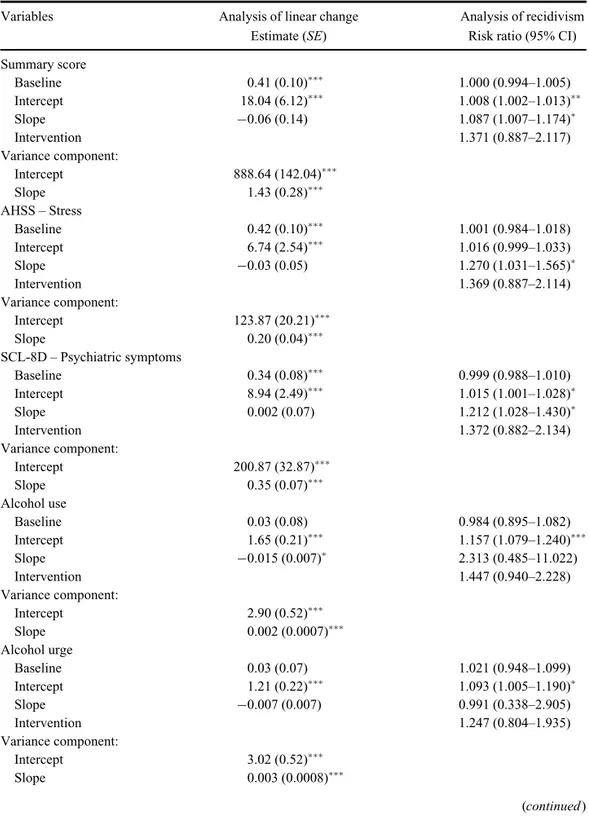

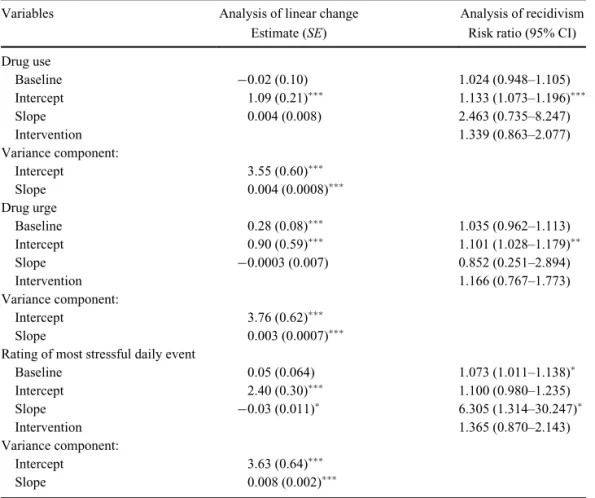

Intervention effect

By using a mixed-models approach, differences in change scores in daily variables between the intervention and control group were analysed over the 30-day assessment period (paper I). Compared to the control group (n=56) the intervention group (n=52) demonstrated significantly greater improvement in the summary scores (p<.05), in mental symptoms (p<.05), in alcohol drinking (p<.05), in drug use (p<.001), and in most stressful daily event (p<.001).