Resettlement constitutes a durable solution to international refugee protection. However, for it to be sustainable, the integration process of the post-resettlement phase is crucial. This volume, which is the outcome of the project “Before and After – New Perspectives on Resettled Refugees’ Integration Process”, sheds light on the integration process from a broader perspective. After briefly addressing the labour-market integration of resettled refugee groups in Sweden, the volume’s main and longest chapter addresses the role of social networks in the integration process of resettled refugees. Social networks are analysed in relation to time and space, and hence attention is paid both to the time before – spent in refugee camps – and to the patterns of mobility pre- and post-resettlement. The following two chapters move away from Sweden and focus on the situation in Australia – with an investigation into the role of ethnic social networks – and Japan, with a focus on the recent development of the country’s resettlement programme. The final chapter brings the focus back to Sweden and enriches the volume by looking at one particular aspect of the resettlement process – the Cultural Orientation Programme – from a postcolonial perspective.

MALMÖ UNIVERSITY isbn 978-91-7104-637-6 (print) isbn 978-91-7104-638-3 (pdf) BIR GITTE SUTER & KARIN MA GNUSSON (EDS.) MALMÖ UNIVERSIT Y • MIM RESETTLED AND C ONNECTED?

R E S E T T L E D A N D C O N N E C T E D ?

S O C I A L N E T W O R K S I N T H E I N T E G R A T I O N P R O C E S S O F R E S E T T L E D R E F U G E E S

© Malmö University (MIM) and the authors Illustration: Arton Krasniqi

Front page image: © 2015, Luca Serazzi.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/>,

Printed in Sweden by Holmbergs, Malmö 2015 ISBN 978-91-7104-637-6 (print)

ISBN 978-91-7104-638-3 (pdf)

Malmö University

Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM)

SE-205 06 Malmö Sweden

BRIGITTE SUTER &

KARIN MAGNUSSON (EDS.)

RESETTLED AND CONNECTED?

Social Networks in the Integration Process

of Resettled Refugees

Malmö University, 2015

MIM

This publication is also available on www.mah.se/muep

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 7

PRESENTATION OF AUTHORS ... 8

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ...11

1. INTRODUCTION ...12

Brigitte Suter and Karin Magnusson 2. RESETTLED REFUGEES IN SWEDEN: A STATISTICAL OVERVIEW ... 35

Pieter Bevelander 3. BEFORE AND AFTER: NEW PERSPECTIVES ON RESETTLED REFUGEES’ INTEGRATION PROCESS ... 55

Brigitte Suter and Karin Magnusson The strength of strong ties: resettled Burmese Karen in Sweden ... 73

Fragmented networks, scattered placement: recently resettled Somalis in Sweden ...101

Findings ...121

4. CREATING COMMUNITY: KAREN REFUGEES’ STORIES OF TRANSITION TO LIVING IN AUSTRALIA ...145

5. ADDRESSING HUMANITARIAN NEEDS OR PURSUING POLITICAL PURPOSES? AN OVERVIEW

OF JAPAN’S RESETTLEMENT PROGRAMME ...180

Sayaka Osanami Törngren

6. RESETTLEMENT FROM A POSTCOLONIAL PERSPECTIVE: ENCOUNTERS WITHIN SWEDISH

CULTURAL ORIENTATION PROGRAMMES ... 213

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This anthology is part of a project financed by the European Refugee Fund (ERF) and MIM, Malmö University, and we are grateful to both of our funders for their financial support. We would also like to express our gratitude to three people who have been instrumental to this project – Henrik Emilsson during the application process, and Louise Tregert and Angela Bruno Andersen throughout the project.

We would like to thank the following people and institutions for their support in creating this anthology: Our reference group – Karin Davin, George Joseph and Gabriella Strååt – for their great commitment and contributions to the project; our steering group – Benny Carlson, Christina Johansson and Pieter Bevelander – for their involvement and sharing of knowledge; Oskar Ekblad and Denise Thomsson from the Migration Board for their assistance and support; our colleagues at MIM – Ioana Bunescu, Inge Dahlstedt, Christian Fernandez, Henrik Emilsson, Anders Hellström, Anna Lundberg, Erica Righard, Sofia Rönnqvist and Ioanna Tsoni – for their invaluable feedback on the texts and our fruitful discussions; Shirley Worland for her generous assistance during the trips to Thailand; and Jenny Money for the language editing.

Last but not least, we would like to thank all the resettled refugees and key informants, who have provided us with information and whose participation has been vital to this project.

PRESENTATION OF AUTHORS

Pieter Bevelander is Professor of International Migration and Ethnic

Relations (IMER) and Director of the Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM). His main research field is international migration, aspects of immigrant integration and attitudes towards immigrants and ethnic minorities. His latest research includes the socio-economic and political impacts of the citizenship ascension of immigrants and minorities in host societies. He has recently co-edited the following publications: Resettled

and Included? The Employment Integration of Resettled Refugees in Sweden (Malmö: MIM, 2009) and Crisis and Migration: Implications of the Eurozone Crisis for Perceptions, Politics, and Policies of Migration (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2014).

Karin Magnusson holds a BA in International Studies from

Macalester College, USA, and an MA in International Migration and Ethnic Relations (IMER) from Malmö University, Sweden. Her previous research involved highly skilled labour migrants and Somali refugees’ labour market integration in Sweden. She is currently working as a Research Assistant at the Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare on projects focusing on resettlement, integration and forced return. Her latest publications include Somalier på arbetsmarknaden – har Sverige något att lära? (Stockholm: Framtidskommissionen, 2012) and The World’s Most

Open Country: Labour Migration to Sweden after the 2008 Law

MeheK Muftee is a Senior Researcher and Lecturer at Linköping

University. She completed her PhD in Child Studies in the Department of Thematic Studies (TEMA). Her research interests revolve around postcolonial theory, refugee migration and child studies. In her dissertation she examined the Cultural Orientation Programs (COPs) for children and youth from the Horn of Africa being resettled in Sweden. One focus of her work is on how the agency of the children came about within the COP context. She has recently published “Children’s Agency in Resettlement: A Study of Cultural Orientation Programs in Kenya and Sudan”, in Children’s

Geographies (2015), 13(2), 131–148.

sayaKa osanaMi törngren received her Ph.D. in Migration and

Ethnic Studies from Linköping University, and is an Affiliated Researcher at MIM. Since 2014 she has been a visiting researcher at Sophia University in Tokyo and engages in research on refugee resettlement in Japan. From December 2014 to April 2015 she worked as a national policy researcher for UNHCR Tokyo, and co-authored the forthcoming report A Socio-Economic Review

of Japan’s Resettlement Pilot Project (provisional title). She is

also a part-time lecturer, teaching courses on race, ethnicity and international migration at different universities in Tokyo. Her latest publications include “Does Race Matter in Sweden? Challenging Colorblindness in Sweden”, Sophia Journal of European Studies (2015), 8, 125–137.

Brigitte suter is a Senior Researcher and Lecturer at the Malmö

Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM). Her research interests include (im)mobility, social networks and processes of in/exclusion and resettlement. She has previously been engaged in several international projects coordinated by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). She is, inter alia, the author of “Social Networks in Transit: Experiences of Nigerian Migrants in Istanbul”, Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies (2012), 10(2), 204–222, and co-author of a chapter on migration in Dahlstedt and Neergard (2015) International Migration and Ethnic

shirley Worland is a Lecturer at Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Since completing her PhD – which explored displaced Karen identity – in 2010 in the School of Social Work and Human Services at the University of Queensland, Australia, she has worked in a voluntary capacity for young Karen refugees. Her latest action research project aims to develop a standardised curriculum for refugee and migrant schools in Thailand to which both the Myanmar and the Thai Ministries of Education will give accreditation. She is the co-author of “Religious Expressions of Spirituality by Displaced Karen from Burma: The Need for a Spiritually Sensitive Social Work Response”,

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AMIF Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund CBO Community Based Organisation

COP Cultural Orientation Programme ERF European Refugee Fund

ICCR Inter-Ministerial Coordination Council for Refugee Issues

IOM International Organization for Migration JEURP Joint EU Resettlement Program

KKBBSC Kawthoolei Karen Baptist School and College KNLA Karen National Liberation Army

KNU Karen National Union KRC Karen Refugee Committee KSC Karen Swedish Community KWO Karen Women Organisation KYO Karen Youth Organisation

MSCWA Multicultural Service Centre of Western Australia NGO Non-governmental Organisation

REC Resettlement Expert Council RHQ Refugee Assistance Headquarters SFI Swedish for Immigrants

SKBF Swedish Karen Baptist Fellowship TBC The Border Consortium

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees WCEC Wyndham Community and Education Centre

INTRODUCTION

Brigitte Suter and Karin Magnusson

For the first time since World War II, more than 50 million people are fleeing conflict and war (UNHCR 2014a). Since 2011, the war in Syria and the refugee crisis connected to it not only makes international headline news, but also tops international humanitarian calls for initiatives and donations. In addition to the war in Syria, the world counts more than 50 other refugee crises, with only 40 per cent of them receiving media coverage in industrialised countries (Mahoney 2014). Among these refugees, the UNHCR has identified around 1 million who are in need of resettlement (UNHCR 2014b). Resettlement constitutes one of the three durable solutions executed by the UNHCR as part of its mandate to protect refugees and seek, together with governments, sustainable solutions:

Resettlement involves the selection and transfer of refugees from a State in which they have sought protection to a third State which has agreed to admit them – as refugees – with permanent residence status. The status provided ensures protection against refoulement and provides a resettled refugee and his/her family or dependants with access to rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals. Resettlement also carries with it the opportunity to eventually become a naturalized citizen of the resettlement country (UNHCR 2011:3).

Resettlement is commonly used when the two other durable solu-tions, local integration and repatriation, are not possible. To give a few examples, Somalis who received refugee status in Kenya, Burmese refugees in Thailand, and any non-European refugees recognised in Turkey are resettled because local integration is not possible in these countries and because a sustainable return to the country of origin is not a feasible option.

The 1 million displaced people identified as being in need of resettlement not only lack access to opportunities for local integration or repatriation; they are also deemed to be “particularly vulnerable”. There is, however, a large mismatch between the number of refugees identified to be in need of a third country willing to receive them and the actual places available; currently around 1 per cent of them receive a resettlement place (SRF 2015; UNHCR 2014b). In light of this mismatch, the UNHCR has, since the year 2000, worked towards increasing the number of both resettlement states and of the places actually available for resettlement.

Global resettlement

The United States continues to lead the resettlement figures; in 2014 alone, it resettled around 70,000 refugees, a figure similar to the number it has resettled in previous years (Refugee Processing

Center 2015). The US is followed by Canada and Australia, which

accepted an overall number of 13,900 and 11,000 resettled refugees respectively – both government sponsored and privately funded (UNHCR 2014c, 2014d). The EU resettled around 7,500 refugees in 2014 (European Resettlement Network n.d.a). Of the EU countries, Sweden’s annual quota of 1,900 is by far the highest. The Nordic countries, Sweden, Denmark and Finland, together accept around 75 per cent of all resettled refugees in the EU (Bokshi 2013).

Resettlement also takes place in South America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay conduct their resettlement in different ways (Cariboni 2014; UNHCR 2003). In Asia, Japan started a pilot programme in 2010 that was transformed into a regular programme five years later. Despite being relatively modest in the number of resettled refugees accepted, Japan’s post-resettlement programme is ambitious and comprehensive (see Osanami Törngren, this volume). Furthermore, another Asian country, Cambodia, has

become a quasi-resettlement country. The Cambodian government sealed a deal with Australia in 2014, agreeing to accept individuals who have been recognised as refugees by Australia. These refugees are individuals who have arrived in Australia irregularly by boat and have been excluded from local integration there under the current restrictive refugee policy (BBC 2014). None of the other countries on the Asian continent1 have thus far responded to general or specific international calls for resettlement (Middle East Monitor 2014).

European developments in the field of resettlement

Western European countries have resettled refugees on an ad hoc basis throughout the past 60 years – for example, refugees from Hungary in 1956, Chile in the 1970s and Indochina in the 1970s. In recent years, European countries – most of them Western European with a long experience of receiving asylum-seekers and refugees – have responded to “special calls” by the UNHCR and/or the European Commission to resettle refugees on an ad hoc basis; among them were Iraqis in 2008, refugees displaced by the Libyan war in 2011 and, currently, Syrians. Germany is the European country that has resettled the largest number: 30,000 Syrians refugees. However, the vast majority of these latter have been accepted under a temporary form of resettlement, the Humanitarian Admission Program, or HAP.2 A handful of European countries have run regular

resettle-ment programmes providing permanent resettleresettle-ment for a substan-tial amount of time; Sweden since 1950, Denmark since 1978, the Netherlands since 1984, Finland since 1985 and Ireland since 1998 (European Resettlement Network n.d.b, n.b.c).

Within Europe, the EU is the main actor pushing for resettlement. Early manifestations on the policy agenda started around 2000, culminating in the adoption of the Joint EU Resettlement Program (JEURP) in 2012. Today, resettlement is a crucial element of the external dimension of the EU’s asylum policy, and thus an integral part of the Regional Protection Programs (RPP). These program-mes are generally conducted in the source regions of conflict (such as the Horn of Africa, the African Great Lakes region and Eastern North Africa) or in the transit countries of asylum-seekers, such as the Eastern European countries of Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine (European Commission 2015). Their rationale is largely to support

the establishment of asylum systems in these countries by extending the EU’s expertise and providing the countries with the financial means to enhance their capacity-building. In return, the EU agrees to resettle some of the refugees in these countries (European Commis-sion 2005). Although resettlement is part of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), it has never been the subject of harmonisa-tion in the way that recepharmonisa-tion and asylum procedures have been.

In cooperation with the UNHCR, the EU has, in the past 15 years, tried to support resettlement on its territory and to encourage more member-states to resettle. This has been relatively successful, especially since the introduction of financial support for new resettlement states was introduced through the European Refugee Fund (2008–2013). Before 2003, there were five resettlement states in the EU with regular programmes; today (2015) 14 EU member-states – Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden and the UK – have regular resettlement programmes. Several others, such as Italy, Poland, Austria and Luxembourg, have resettled refugees on an ad

hoc basis and responded to special calls by the UNHCR and/or the

EU Commission. In addition, the non-EU states of Norway and Iceland have also responded with regular programmes, Switzerland and Iceland with pilot projects and Switzerland and Iceland with ad

hoc receptions (European Resettlement Network n.d.b; Krasniqi &

Suter 2015; SRF 2015; UNHCR 2014e).3

However, despite the EU’s establishment of resettlement as a tool for refugee protection and the recent increase in the number of resettlement countries, the EU’s quota of resettlement places has not substantially increased. As we saw earlier, the Union resettles considerably fewer refugees than the US, Canada and Australia. One explanation for this is that many of the newer resettlement countries accept quite modest numbers of refugees; for example, Portugal and the Czech Republic resettle around 30 persons a year. Another explanation for the low numbers of resettled refugees in the EU is that these countries receive far more asylum applications than do the US, Canada and Australia. In 2013, EU member-states processed almost 400,000 asylum applications (500,000 for European countries as a whole), compared to 90,000 for the USA, 10,000 for Canada and 26,500 for Australia (Australian Government 2014; UNHCR 2013).

There have been concerns that EU member-states treat the reception of asylum-seekers and resettled refugees as part of the same pot, which means that, if one category is increased, the other is decreased (Bokshi 2013). Developments in France, Finland and Belgium suggest that a high number of asylum-seekers have limited the number of resettlement places available. The opposite is also feared – that a higher number of resettlement places decreases the recognition rate of asylum-seekers. However, statistical evidence shows that it is the countries that receive the highest numbers of asylum applications which also resettle the most refugees. For example, Sweden, which had the highest recognition rate of refugees between 2000 and 2011 – an estimated 120,000 – also accepted the highest number of resettled refugees, roughly 19,000 individuals.

All in all, various stakeholders and observers (inter alia, the European Commission 2005; Bokshi 2013; UNHCR 2014b; Zetter 2015) express the importance of increasing the number of resettlement places in order for resettlement to constitute a valuable tool in international refugee protection. Efforts to increase resettlement places are often supported by the argument that it will create more legal channels into the EU and “protect” asylum-seekers from a dangerous, life-endangering journey via potentially unscrupulous smugglers and traffickers (Zetter 2015). This is certainly a laudable argument. However, the drawback is that the increased emphasis on resettlement runs the risk of viewing resettled refugees as “genuine” refugees deserving of humanitarian efforts/aid, while asylum-seekers, who engage independently in mobility in order to access the asylum systems in the richer countries (“The West”), are perceived (according to recent trends) to be “less deserving”. More often, asylum-seekers are seen through the lenses of national and supra-national security and met with suspicion (Hyndman & Giles 2011; Järvinen et al. 2008). The fact that there is no legal obligation to resettle makes resettlement an opportunity for the richer countries to express “goodwill”. Scholars, for example Bokshi (2013), Hyndman & Giles (2011) or Troeller (2002), have criticised the emphasis on resettlement if it comes at the expense of asylum, arguing that there is the risk that adherence to international refugee law is eroded in the process. The challenge for the future development of the asylum system in European countries is thus to strengthen resettlement as

a tool of solidarity towards countries of first asylum, of burden-sharing between EU member-states, and an humanitarian effort for individuals in need of protection, while simultaneously assessing and assuring the protection needs of asylum-seekers who reach EU territory by non-state-assisted means.

The future of resettlement?

Given the various positive statements by major stakeholders, such as the UNHCR, the EU Commission and researchers, on resettlement, it is likely that the topic of resettlement will experience more attention in the future. This section addresses some of the discussions regarding resettlement within the field of refugee protection at international, supra-national and national levels.

For many years, the international community has responded to refugee crises by setting up camps in various countries, many of which are among the poorest in terms of GDP.4 A refugee camp usually provides protection for life, but fails to guarantee other basic human rights, such as the right to mobility, work and education. Many of these breaches of human rights are connected to the fact that the refugees do not enjoy a legal status during their time in the camps. This is accepted since refugee camps have hitherto been seen as temporary places of shelter, not intended to provide long-term solutions to refugee situations (Hyndman & Giles 2011). However, in reality, the average time a displaced person spends in a refugee camp is 17 years (UNHCR 2004). In other words, camps have become much more than just temporary shelters; instead they constitute an existential limbo in which human capabilities are wasted (Hyndman & Nylund 1998). This long-lasting displacement is often referred to as a “protracted refugee situation”, one which will be discussed throughout this anthology.

Furthermore, there has been an increased awareness among humanitarian actors and observers that international refugee law based on the 1951 Geneva Convention and its related 1967 Protocol is ill-equipped to meet contemporary demands of displacement. The factors leading up to displacement today are “complex and multicausal”, hence the current international framework fails to protect those displaced whose protection claims do not fall under the relatively narrow protection framework of the Convention

(Zetter 2015). Not only has this left many individuals excluded from the protection they need, but many also find themselves stuck in refugee camps as their subsidiary protection status often disqualifies them from resettlement or other entitlements extended to recognised refugees under the Convention. On the receiving side, states have introduced somewhat compromised forms of protection, such as “humanitarian admission” or “subsidiary protection” status. These are protection categories in EU and EU member-states’ national laws that extend protection often on a temporary basis and often with a fraction of the entitlements extended to a person recognised as a refugee under the Convention.

Several scholars have suggested that policy-makers reconsider. Zetter (2015) advances two interrelated issues to address in the current “protection crisis”. Firstly, he points to the need to increase legal channels for migration. The enhancement of resettlement is named here as an important component. With regards to the countries of first asylum, Zetter urges states and stakeholders not only to not recognise a refugee situation as a purely humanitarian crisis, and highlights the de facto development of the border region due to the large-scale presence of refugees for the past 20 years, and attests both individual refugees and the wider aid economy surrounding the camps as being crucial for the development of the region. Furthermore, Brees (2009) advances Jamal’s (2008) suggested segmented approach, which argues for the differentiated application of durable solutions – i.e. local integration, repatriation or resettlement – for refugee sub-groups. This segmented approach is, among others, based on the realisation that, even in protracted refugee situations, some sub-groups of refugees are economically and/ or socially de facto integrated, even if their legal status renders proper integration impossible. As such, instead of seeing resettlement as an overall solution to the whole refugee group of a camp or a region, a more nuanced application of different durable solutions to different refugee sub-groups could yield more beneficial results in terms of the economic, social and psychological well-being of all stakeholders involved. Allowing for (or even promoting) increased self-reliance in a situation of displacement – through greater mobility rights as well as the right to work and access education – is furthermore seen as beneficial, above all for those who eventually repatriate. Yet, until a

return is feasible, the increased self-reliance also benefits the region where the displaced find temporary shelter: firstly, refugees, as seen above, often contribute to the revitalisation of a border region. The increased level of self-reliance also allows humanitarian donors to spend their financial contributions on development in the region rather than on feeding a dependent population (see Brees 2009; Jamal 2008).

On supra-national policy development, the EU has been – as mentioned above – a vital actor in bringing the topic of resettlement to the policy agenda and to actively promote resettlement on its territory. The areas where the EU has so far had the biggest impact or is seen to be able to play a crucial role is through the provision of financial aid – via the European Refugee Fund (2008–2013) and the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (2014–2020) – by influencing the political will of national states, and by facilitating collaboration and the exchange of knowledge and skills between the member-states (Bokshi 2013).

The financial incentives that were introduced by the European Refugee Fund (ERF) had a crucial impact on the number of resettlement countries, as several of these latter have since introduced a national resettlement programme, many of which – for example, the Bulgarian, Portuguese, Belgian, German and Hungarian programmes – are fully or partially financed by the fund (Bokshi 2013). Financial constraints – in general and with reference to the financial crisi of 2008–2012 in particular – are indeed a reason given by member-states to account for their small or absent commitment to resettlement. While, under the ERF, member-states received €4,000 per resettled refugee, the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) increased this sum to €6,000 per individual refugee, and to €10,000 for individuals identified as particularly vulnerable: women and children at risk, separated children, persons with medical needs and persons in need of emergency resettlement (Bokshi 2013). In general, the AMIF working programme spells out its rationale to support individual member-states financially, while simultaneously working at the EU-wide level to consolidate the harmonisation of its asylum policy, including the promotion of resettlement and relocation, or intra–EU resettlement (European Commission 2014).

Within the framework of the Joint EU Resettlement Program (JEURP), member-states are offered the possibility to show their political willingness to burden-share with other member-states and to show solidarity with first countries of asylum. Romania, furthermore, used the opportunity to resettle refugees in order to profile itself as a partner in refugee protection in an international and, even more so, EU context (Bokshi 2013). Furthermore, the political will often also has to do with public discourse. While debates around immigration have generally had a tendency to express rejection and suspicion and to call for more restrictive policies, the issue of resettlement is not well-known to the public in the member-states. In cases where resettlement was broadcast in the media, the reaction was often positive. Hence, Bokshi (2013) identifies a need to increase the general public’s awareness about and knowledge of resettlement through increased media reporting at all levels of governance.

Finally, the EU plays a crucial role in facilitating collaboration in other areas, such as selection missions.5 Increased collaboration has the advantage of enabling more cost-effective activities to be conducted which, in turn, would release more funds for increasing the resettlement capacities of the individual countries (Bokshi 2013). Further, the supranational actors can assume a prominent role in facilitating the exchange of knowledge and skills on both pre- and post resettlement processes. For resettlement to be a truly durable solution – in the sense that it attains sustainable outcomes – the post-resettlement situation of these refugees is of particular concern, and the integration of resettled refugees into the economic, political and social spheres of the member-states is thus considered to be a crucial part of resettlement (Bokshi 2013). The recently established European Asylum Support Office (EASO) in Malta has hitherto played a low-key role with regards to resettlement, but it could potentially have an important function in facilitating the exchange of experiences and the collaboration of both pre- and post-resettlement processes.

For the future of the EU resettlement programme and the enhancement of its sustainability and effectiveness, the AMIF certainly, and the EASO possibly, will play a crucial role in providing an infrastructure and financial incentives to member-states, training for staff and other post-resettlement assistance. Apart from these

measures, there have been calls from experts (see European Parliament 2013; van Selm et al. 2004) for a joint EU quota and a specific body that would be tasked with distributing resettled refugees to member-states according to the host-country’s capacity.

The EU’s relatively short and not very extensive history of receiving resettled refugees can explain why academic contributions from a European perspective have hitherto been rare.6 Studies of integration with an explicit focus on resettled refugees are even less frequent (European Parliament 2013). There have been a number of exceptions, mostly from international organisations or think-tanks (such as the UNHCR, ECRE or the Migration Policy Institute), and by researchers (see, for example, Bevelander et al. 2009; Kohl 2015; Muftee 2014; Nibbs 2011; Robins-Wright 2014; Suter & Magnusson 2014; Tip et al. 2014).7 This anthology therefore enriches this scant number of scholarly publications on resettlement within the EU; its empirical and theoretical findings are, nevertheless, of relevance beyond the EU context.

Finally, for the future of resettlement at the national level, many of the concerns and challenges outlined above are the same. While the EU provides guidelines, directives and regulations for increased harmonisation, asylum matters still fall under the scope of the individual member-states. Resettlement is one of the least regulated aspects in the field of asylum, and as such looks – as presented above to some extent –very different in each resettling member-state. The practices of countries vary with regards to how refugees are selected, how they are prepared for resettlement, what provisions are extended to them upon arrival and which residence permit they can obtain and so forth. For example, with regards to the selection criteria, some member-states show an over-representation of women among the resettled, while others predominantly favour Christians over refugees with other religious affiliations (Bokshi 2013).8 However, what is common to all member-states is the very little awareness of the general public on the issue of resettlement, at both national and local levels. This is something that needs to be addressed at all levels if resettlement places are to increase. Furthermore, given the largely national sovereignty over asylum issues, the danger of relocation at the expense of resettlement is principally a national concern, as is the danger of trading off resettled refugees against asylum-seekers.

With reference to the above-mentioned current protection needs on a global scale, such a trade-off would be fatal to the international protection of refugees, the brunt of which is already borne by some of the least-developed countries and ultimately, of course, the displaced refugees themselves.

The post-resettlement period: integration

Since post-resettlement integration is an essential element for resettlement to truly count as a durable solution, some considerations are provided here. Given the perceived difficulties of integrating resettled refugees, researching the topic has become part of the EU’s efforts to increase resettlement places throughout the Union. “The effectiveness of resettlement as a durable solution depends upon ensuring that resettled refugees have the opportunity to integrate” (European Parliament 2013:10).

While, in many countries, relevant statistics on the integration of resettled refugees are unobtainable, Bevelander (2009, and his 2015 chapter in this anthology) is able to demonstrate, for Sweden, that resettled refugees show the least employment integration compared to other refugee categories such as refugees’ relatives and refugees who arrived as asylum-seekers, but that, after 15–20 years they have caught up. With regards to these general results, we should point out that the findings for the different nationalities vary widely. Explanations for this can be sought in the pre-resettlement situation with regards to refugees’ (human, social and cultural) capital acquisition, their mental-health state as a result of war and displacement, the reception framework and the labour market, for example. Studies by Bevelander (2009) and Järvinen et al. (2008) offer several explanations for the slower initial integration of resettled refugees compared to those refugees who arrived as asylum-seekers in Sweden. Unlike the latter, resettled refugees had no time to get acquainted with Sweden before they started their introduction programme.9 They may still be in the early phases of cultural adaptation when they begin the programme, which might make it more difficult for them to digest the knowledge presented and thus slow down their integration (Järvinen et al. 2008). And, in most cases, resettled refugees have not themselves decided in which country to resettle. This could mean that they lack any expectations

of the resettlement country, which has, again, been shown to negatively affect their ability to establish themselves (Järvinen et al. 2008). Furthermore, resettled refugees are often placed in smaller municipalities and in rural areas with fewer job opportunities. Resettled refugees are unlikely to be placed in municipalities with many job opportunities since there is often a lack of housing there (Järvinen et al. 2008). The geographical placement, as well as the concentration of refugees, are indeed important aspects affecting the outcome of the integration process (Brunner 2010). Finally, at least in the Swedish case, resettled refugees tend to have fewer social networks on which they can lean after arrival than other refugee groups (Järvinen et al. 2008). Even so, we should note that, while integration is important for many reasons, as outlined above, ultimately resettlement is a humanitarian practice and (usually) not a political or economic exercise.10 As such, among the resettled refugees are those perceived to be the most vulnerable from a social and health perspective, and economic performance should not, therefore, be the only aspect against which to measure their integration process.

Social networks and mobility

Social networks based on ethnicity or nationality have been mentioned above as important, and they may, indeed, provide some explanation for the differences in the labour-market integration of resettled refugees in Sweden, and to integration in general. This anthology serves to provide more knowledge on the importance of social networks in relation to resettled refugees’ integration, as many of the chapters deal, to a certain extent, with the topic (Chapters 3, 4 and, partially, 5).

International scholarship has generally found social networks based on family ties, nationality or ethnicity to be beneficial for the integration process of resettled refugees. These may be already established social networks to which the newly arrived have access, and which generally fulfill the function of providing information, resources and a feeling of belonging to the newcomers. In cases, however, where refugees arrive as the pioneer group – i.e. where there has not been any prior migration of their co-nationals – this type of support is lacking. Nevertheless, as is shown, in Chapter 3,

while social networks established after arrival with individuals from the same pioneer group cannot provide the same level of support, these networks can still play an important role, as they provide a venue in which to foster bonding ties based on a sentiment of belonging, and promote migrant self-esteem. Over time, these types of network can play an important role in society, and create bridges to other networks that are richer in resources (see Chapter 3 for more details).

Mobility practices can also be crucial for integration. As such, individuals may move to where they feel they will receive the best education, or to a different municipality or country where they can make better use of the social ties they have. In the Canadian context, studies that deal with refugee resettlement specifically have identified employment as well as closeness to family and friends as the most important factors leading to secondary migration within the country after resettlement (Abu-Laban et al. 1999; Simich 2003). Resettled refugees not only rely on government assistance to navigate their way into the new society, but also on family, friends and members of the same ethnic group, who share a similar cultural background and experience of conflict, flight, refuge and refugeehood. The bureaucratic decision to split up extended families between different municipalities in the same country or even – as is the case for some of the Burmese and Somali interviewees in this study – between different countries and continents, leads not only to emotional distress, but also to secondary migration. Ultimately, secondary migration has been found to be a practice enabling refugees to maximise their social support (Simich 2003).

Structure of the anthology

The contribution of this volume is to present multiple views on resettlement, with many chapters focusing on integration and social networks. Out of five chapters, three deal with the situation in Sweden. However, the Swedish experience is also contrasted with resettlement experiences in two other countries: Australia and Japan (chapters 4 and 5). Social networks hold a quite prominent position the chapters: 3, 4, and, 5.

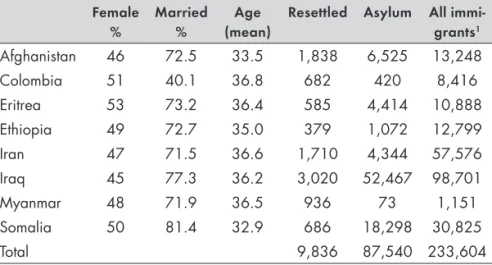

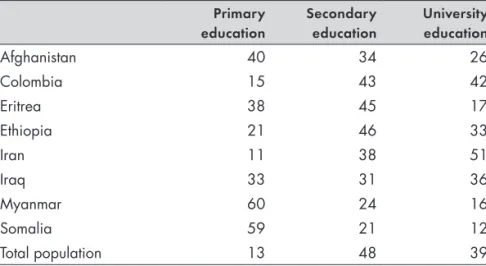

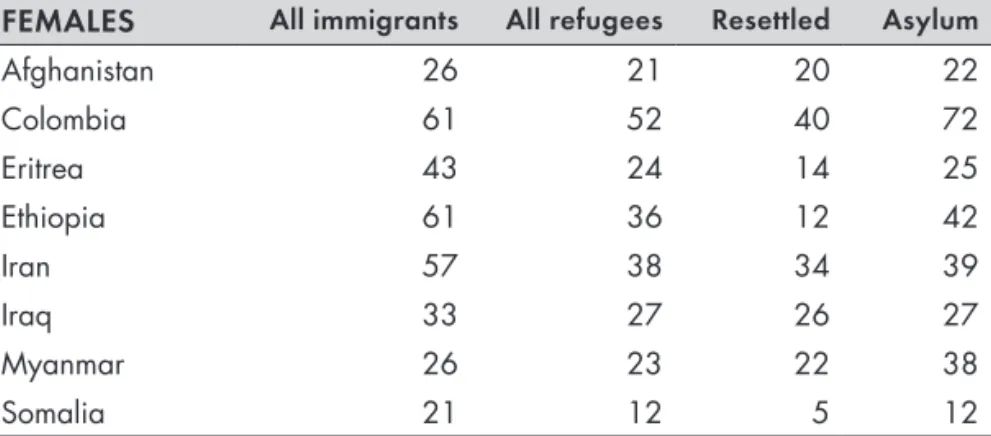

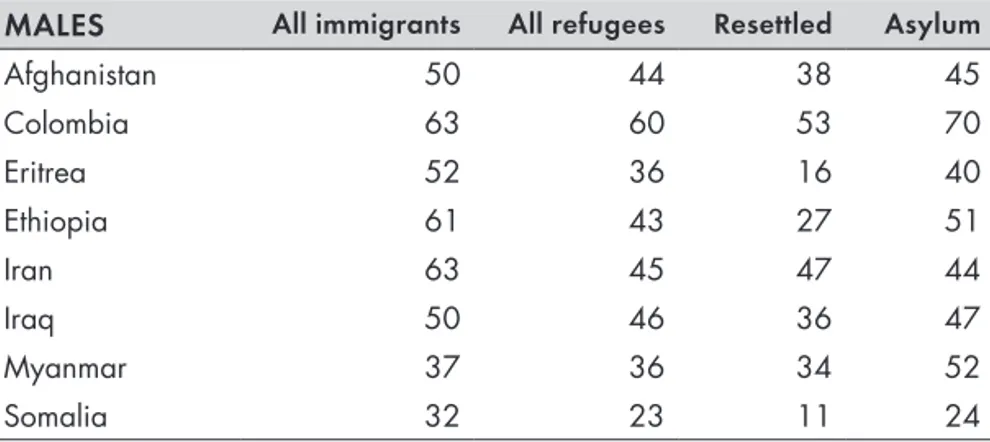

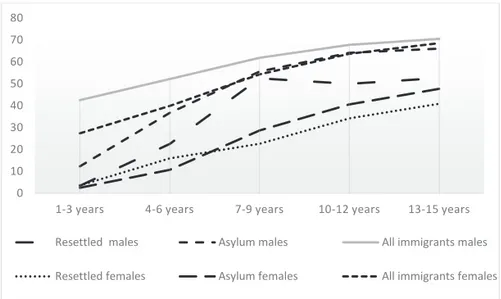

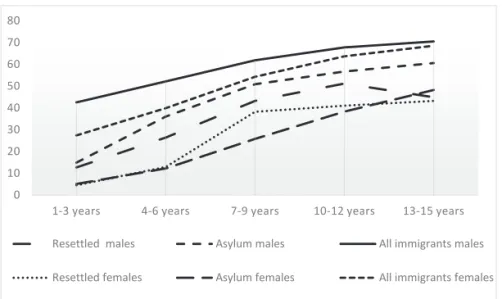

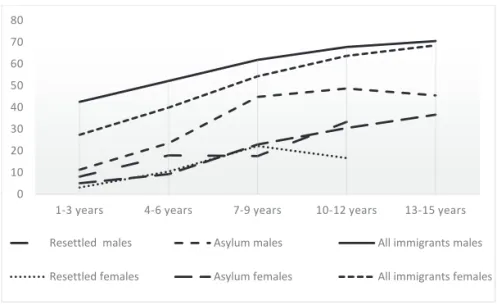

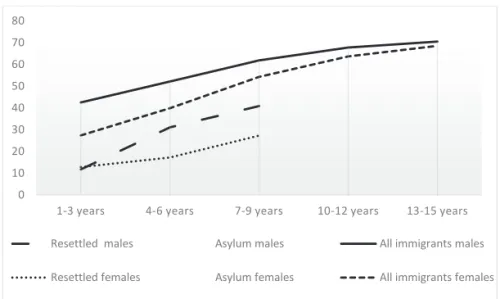

In Chapter 2, Pieter Bevelander provides us with a statistical record of the demographics and socio-economic situation and,

in particular, the employment integration, of resettled refugees, refugees and other immigrants who have arrived in Sweden over the past 15 years. He focuses on eight specific countries of origin –Afghanistan, Colombia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Myanmar and Somalia – from where each group consists of a considerable share of individuals who have arrived through resettlement. First and foremost, the results show a great variation in educational attainment and average employment levels for the different groups in 2012. For both males and females in the eight groups under study, a high correlation between educational attainment and employment level is measured. Studying their employment integration over time shows that all groups present increasing employment levels the more years they spend in the country. Refugees from Iran, Colombia, Eritrea and Ethiopia have had employment trajectories similar to those of the average immigrant in Sweden. Refugees from Myanmar and Somalia do less well and have considerably lower levels of employment over time. These two countries also have the lowest levels of education. Refugees from Myanmar mainly arrived in Sweden through resettlement, following many years in refugee camps without a regular education system.

Chapter 3, by Brigitte Suter and Karin Magnusson, is the

lengthiest of the anthology and is, together with the previous chapter, the product of a two-year study financed by the European Refugee Fund (ERF 86-300). The project is a follow-up to an earlier study, “Resettled and Included?” (Bevelander et al. 2009), and aims to both deepen and broaden knowledge of resettlement and its consequent integration processes in Sweden. Suter and Magnusson’s study focuses on the integration processes of resettled refugees from Somalia and Burma in Sweden through a qualitative lens. Although the chapter’s approach to integration is based on a broad understanding of the concept, it specifically focuses on the experiences and perceptions of the refugees. Its contribution, therefore, lies in conceptualising how social networks in time and space affect the integration process after resettlement. Social networks are seen as influenced by patterns of mobility and by the acquisition, in their pre-resettlement life, of social, economic, human and cultural capital (for instance, in the form of opportunities for education, income generation and self-determination). They connect the situation and opportunities of

the pre-resettlement time with their situation after resettlement in Sweden. In studying social networks in both time and space – at local, national and transnational levels – and in analysing their role in refugee integration, the study distinguishes itself from the majority of other studies in the field that tend to place the focus solely on the post-migration time.11

Each case study starts by shedding light on the pre-resettlement situation and has two main purposes. The first is to show how the situations of conflict and refugee camps can vary greatly in the different places and, as such, to support the literature on critical refugee studies which highlight the refugee as an individual with a history, political preferences and agency. The case study, furthermore, clarifies the fact that refugee camp situations can vary tremendously in the opportunities they offer for education, income generation and self-determination. This, of course, has direct implications for the process of capital accumulation, both at a group and at an individual level.

The case studies then move on to mobility practices, which are directly connected to the pre- and post-resettlement periods. In the refugee camps, freedom of mobility is often restricted, which has direct consequences for capital accumulation and social network formation. After the refugees’ arrival in Sweden, mobility serves as a tool enabling them to forge and maintain social networks and social-network positions. This part also points to institutional and structural factors that contribute to immobility and hinder migrants in strengthening their social ties. Of course, this – as the chapter argues – is not without consequences for the integration processes of the individual refugees.

Finally, the case studies then turn to social-network formation and maintenance. Applying a social capital approach to the discussion of integration has the benefit of being able to link the past with the present. It also serves to show how individuals can benefit from the resources of other individuals through being a member of a social network. Networks can be based on a range of factors – in this study, nationality, ethnicity or language were the basis of the social networks, and the authors highlight how these ethnic social networks are able (or unable) to forge bridging ties to other networks in Swedish society, through which the individuals who are

part of these networks can access further resources and can establish themselves as a group in the new society.

In Chapter 4, by Shirley Worland, the focus remains on Burmese Karen refugees displaced in Thailand and their consequent resettlement experiences. Worland devotes herself to their resettlement in Australia – a traditional resettlement country – and highlights prominent aspects of the refugees’ acculturation through a transition model from the field of social psychology. Contrary to most other countries where Karen refugees from Thailand resettled after 2005, Australia already hosted a large number of Karen refugees who arrived prior to the 2000s. The Karen from this earlier migration were able to build up fully functioning informal and formal social networks and organisations, and some of the individual members also obtained influential positions in local government. The newcomers of the years 2005 and later were able to substantially benefit from these already established network structures – accessing resources and information leading to employment and eventually the purchase of the status symbol, their own house. Like Sweden, the Australian government provides the refugees with considerable welfare benefits once they have been legally admitted to the country. Nevertheless, as this chapter convincingly shows, the positive influence of the ethnic network connections is not to be ignored. In a narrative style over large parts of the chapter, the author not only provides an in-depth account of post-resettlement experiences through rich empirical data, but also convincingly shows the fruitful connections and links between the different agencies and organisations, including those based on ethnic and religious affiliation.

Japan is not known as a country of immigration, and little will change with the reading of Chapter 5, by Sayaka Osanami Törngren, who illuminates the developments that started in 2010 and made Japan the first country in Asia to launch a resettlement programme. The author traces the political and administrative origins of the resettlement programme and contextualises it in a longer history and wider frame of immigration in and to Japan. The chapter highlights the specific circumstances in which the refugees are selected, and some of the original solutions designed by stakeholders to support the self-reliance of the resettled after arrival in Japan. The relatively recent origins of the programme, the comparatively small

numbers of refugees resettled, and the somewhat strict monitoring of the refugees’ establishment in Japanese society enable Osanami Törngren to bring the organisational experience of resettlement closer to the reader; as such, the chapter provides a unique insight into stakeholder discussions on evaluation and on how to improve the system on certain matters of integration and post-resettlement conditions. While the Japanese programme is still very young, and limited in the number and selection of source countries, some of the specific features also deserve to be highlighted as interesting from a more global perspective. For example, as a result of economic self-reliance being one of the most central aspects of the programme, on-the-job training is a crucial part of the one-year introduction programme. Apart from subsidising the employers for every refugee hired, the various stakeholders involved are also instrumental in creating contacts between the employers and the refugees. Another interesting aspect of the Japanese understanding of integration – even though very informal – is the importance placed on ethnic networks as providers of social support. The importance is seen as so crucial to the extent that the local settlement support staff actively make efforts to link together individuals with the same ethnic background. Osanami Törngren emphasises that the Japanese resettlement programme is not based on humanitarian principles; instead, it can be interpreted as constituting a measure through which to address the need for low-skilled labour and to take steps to avert the demographic decline of the population. As the government turned the five-year pilot programme into a regular programme in 2015, the question of humanitarian grounds is indeed a relevant point for consideration.

In Chapter 6, Mehek Muftee enriches this resettlement anthology through two aspects: firstly, a theoretical framework – a postcolonial perspective – that remains largely untouched by the other chapters and, secondly, directing her attention to children in resettlement and showing how they express agency. Based on an understanding of the significance of the colonial legacy, the unequal power relations between refugees from the South, and the humanitarian “good-doers” in the Global North, the chapter focuses on one central aspect of many resettlement programmes: the Cultural Orientation Programme, or COP. In the Swedish case, on which Muftee’s

contribution is based, the COP consists of a Swedish delegation which, in the space of a few days, educates the refugees to be resettled about Swedish cultural specifities and, more generally, about what they should expect in Sweden. As the author argues, the Swedish Migration Board’s declared goal of maintaining these encounters during the COPs in a framework of dialogue is based on the false assumption of non-existing power differentials between the refugee participants and the Swedish delegation. Muftee argues that the goal of two-way communication and dialogue cannot be reached without the members of the Swedish delegation recognising their privileged position within the power hierarchy that resettlement – and the COPs – constitute. First, Muftee questions whether, upon this recognition and further reflection, the encounters within the COPs could go beyond an interaction dictated by stereotypical dichotomous images of “us” and “them”. She illustrates her chapter with excerpts from these attempts at exchange which demonstrate situations in which the youths and children show agency and thereby contribute knowledge and insights which could ultimately encourage the development of modified COPs in order to strengthen the agency and improve the integration of this particular category of refugees in their resettlement.

Notes

1. Some of them – the Gulf countries, for example – have, however, contribu-ted financially (UNHCR 2015).

2. The different admissions countries which apply are described in Krasniqi & Suter (2015).

3. Other EU countries, such as Bulgaria, Slovakia and Slovenia, have provi-sion for resettlement through either a government act or law but have not yet resettled any refugees. Finally, countries like Greece, Cyprus, Lithu-ania, Latvia and Estonia have no formal basis for resettlement, nor have they resettled thus far, either through a programme or on an ad hoc basis. 4. Not all refugees are housed in camps – around 30 per cent of all

displa-ced people on the African continent, for example, live outside camps (but nevertheless in a legal limbo (Hyndman & Giles 2011). In fact, as refugee situations have become increasingly protracted, many of the displaced have opted to settle in urban areas instead (Zetter 2015). These places usually offer better economic opportunities than camps; however the refugees’ lack of legal status renders them very vulnerable to exploitation. 5. Selection missions are trips to a country of first asylum conducted by

representatives of the resettlement country, with the aim of selecting the refugees to be resettled. Often, there is a pre-selection carried out by the

UNHCR, and the selection mission serves to consolidate the UNHCR’s recommendations with the country’s national criteria for the acceptance of resettled refugees.

6. Historically, Europe has been more of a source continent of refugees than a receiver (see Krasniqi & Suter 2015 for more details).

7. Of course, the situation in resettlement-proven countries, such as the US, Canada and Australia, is much different, with a large number of studies concerned with aspects of both resettlement and integration (see, for example, Colic Peisker & Tilbury 2004; Fanjoy et al. 2005; Hyndman & McLean 2006; Neumann 2013; Simich 2003; Worland 2010).

8. Indeed, with regards to religion, Fine (2013) points to the high rate of con-version among Iranian and Afghan asylum-seekers in Turkey, and relates it to their hope that this will give them better access to resettlement.

9. The Swedish introduction programme for immigrants consists of language courses, civic orientation courses and activities to prepare them for the labour market.

10. While some countries simply adhere to the humanitarian criteria of protec-ting the most vulnerable, others apply integration criteria in the selection process, or even make economic self-reliance a prerequisite for a perma-nent residence permit.

11. One notable exception is Erdogan’s (2012) study on the identity formation and acculturation of Karen refugees in Ontario, Canada. Hyndman & Walton-Roberts’ (2000) study on Burmese resettled refugees in the Greater Vancouver area is another. They draw on a transnational concept of migra-tion in order to argue that relamigra-tions to and condimigra-tions in the source country are important aspects to consider when studying refugee integration. Fur-thermore, (Swedish) practitioners also recognise the need to know more about the pre-resettlement situation of the resettled refugees whom they meet during the integration programme (County Administration Gävle-borg 2012).

References

Abu-Laban, B., Derwing, T., Krahn, H., Mulder, M. & Wilkinson, L. (1999) The Settlement Experiences of Refugees in Alberta. Edmonton: University of Alberta, Prairie Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Integration and Population Research Laboratory (revised edition, 15th

November).

Australian Government (2014) Asylum Trends Australia 2012–13. https:// www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/immigration-update/asylum-trends-aus-2012-13.pdf (accessed 10 April 2015).

BBC (2014) Australia and Cambodia Sign Refugee Resettlement Deal. 26 September. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-29373198 (accessed 10 April 2015).

Bevelander, P. (2009) In the Picture: Resettled Refugees in Sweden. In P. Be-velander, M. Hagström & S. Rönnqvist (eds) Resettled and Included? The Economic Integration of Resettled Refugees in Sweden (49–80). Malmö: Malmö University.

Bevelander, P., Hagström, M. & Rönnqvist, S. (2009) Resettled and Inclu-ded? The Economic Integration of Resettled Refugees in Sweden. Malmö: Malmö University.

Bokshi, E. (2013) Refugee Resettlement in the EU: The Capacity To Do It Better And To Do It More. San Domenico di Fiesolo: European University Institute, KNOW RESET Research Report 13/04.

Brees, I. (2009) Livelihoods, Integration and Transnationalism in a Protracted Refugee Situation. Case Study: Burmese Refugees in Thailand. Ghent: University of Ghent, unpublished PhD thesis.

Brunner, L. (2010) From Protracted Situations to Protracted Separations: Acehnese-Canadian Refugee Settlement in Vancouver, BC. Vancouver: Simon Frasier University, unpublished MA dissertation.

Cariboni, D. (2014) Uruguayan Resettlement Scheme Offers Syrian Refugees a Lifeline. Guardian Online, 27 August. http://www.theguardian.com/glob- al-development/2014/aug/27/uruguayan-resettlement-scheme-syrian-refu-gees-lifeline (accessed 10 April 2015).

Colic Peisker, V. & Tilbury, F. (2004) “Active” and “Passive” Resettlement: The Influence of Support Services and Refugees’ own Resources on Resettlement Style. International Migration, 41(5), 61–92.

County Administration Gävleborg (2012) Studiebesök i Thailand. Delrapport inom projektet Landa II. ERF/LS Gäveborg, November 2012.

Erdogan, S. (2012) Identity Formation and Acculturation: The Case of Karen Refugees in London, Ontario. London: University of Western Ontario, unpublished PhD thesis.

European Commission (2005) Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on Regional Protection Programmes. Brussels: European Commission Report COM(2005)0388Final. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52005DC0388 (accessed 10 April 2015).

European Commission (2014) Annex to the Commission Implementing De-cision Concerning the Adoption of the Work Programme for 2014 and the Financing for Union Actions and Emergency Assistance within the Fram-ework of the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund. Brussels: European Commission Report C(2014) 5652 Final.

European Commission (2015) Regional Protection Programs. External As-pects, Migration and Home Affairs. Brussels. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/asylum/external-aspects/index_en.htm (accessed 10 April 2015).

European Parliament (2013) Comparative Study on the Best Practices for the Integration of Resettled Refugees in EU Member States. Brussels: European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies.

European Resettlement Network (n.d.a) Introduction to Resettlement in Europe. http://www.resettlement.eu/page/introduction-resettlement-europe (accessed 10 April 2015).

European Resettlement Network (n.d.b) National Resettlement Programs. http://www.resettlement.eu/country (accessed 10 April 2015).

European Resettlement Network (n.d.c) The Crisis in Syria. http://resettle-ment.eu/news/crisis-syria (accessed 10 April 2015).

Fanjoy, M., Ingraham, H., Khoury, C. & Osman, A. (2005) Expectations and Experiences of Resettlement: Sudanese Refugees’ Perspectives on their Journeys from Egypt to Australia, Canada and the United States. Cairo: The American University in Cairo, Forced Migration and Refugee Studies Program Working Paper.

Fine, S. (2013) The Christianisation of Afghan and Iranian Transit Migrants in Istanbul: Encounters at the Biopolitical Border. Oxford: Oxford University, COMPAS Working Paper No. WP-13-104.

Hyndman, J. & Giles, W. (2011) Waiting For What? The Feminization of Asylum in Protracted Situations. Gender, Place and Culture, 18(3), 361–379.

Hyndman, J. & McLean, J. (2006) Settling Like a State: Acehnese Refugees in Vancouver, Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(3), 345–360.

Hyndman, J. & Nylund, B.V. (1998) UNHCR and the Status of Prima Facie Refugees in Kenya. International Journal of Refugee Law, 10(1–2), 21–48. Hyndman, J. & Walton-Roberts, M. (2000) Interrogating Borders: A

Transnational Approach to Refugee Research in Vancouver. The Canadian Geographer, 44(3), 244–258.

Jamal, A. (2008) A Realistic, Segmented and Reinvigorated UNHCR Ap-proach to Resolving Protracted Refugee Situations. In G. Loescher, J. Milner, E. Newman & G. G. Troeller (eds) Protracted Refugee Situations: Political, Human Rights and Security Implications (141–161). Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

Järvinen, T., Kinlen, L., Doll, J. & Luhtasaari, M. (2008) Promoting Inde-pendence in Resettlement. Final Report of the MOST Project. Helsinki: Edita Prima Oy. http://www.intermin.fi/download/24992_112008.pd-f?18b9449c2cbbd188 (accessed 10 April 2015).

Kohl, K. S. (2015) The Tough and the Brittle: Calculating and Managing the Risk of Refugees. In M. Fredriksen, T. Bengtsson & J. Larsen (eds) The Danish Welfare State: A Sociological Investigation (in press). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Krasniqi, A. & Suter, B. (2015) Refugee Resettlement to Europe 1950–2014: An Overview on Humanitarian Politics and Practices. Malmö: University of Malmö, MIM Working Paper No 15:1.

Mahoney, C. (2014) Supporting Innovation in Refugee Camps. TED talk, 5 February http://tedxtalks.ted.com/video/Supporting-innovation-in-refuge (accessed 10 April 2015).

Middle East Monitor (2014) Organisations Call on Rich Countries to Resettle More Syrian Refugees. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/news/eu- rope/15709-organisations-call-on-rich-countries-to-resettle-more-syrian-ref-ugees (accessed 10 April 2015).

Muftee, M. (2014) “That will be your home”. Resettlement Preparations for Children and Youth from the Horn of Africa. Linköping: Linköping University, Studies in Arts and Science No. 625.

Neumann, K. (2013) The Resettlement of Refugees in Australia: A Bibliog-raphy. http://apo.org.au/files/Resource/resettlement%20bibliography%20 13%20June%202013.pdf (accessed 10 April 2015).

Nibbs, F. (2011) Refugeehood and Belonging: Processes, Intersections and Agency in Two Hmong Resettlement Communities. Dallas: Southern Met-hodist University, unpublished PhD thesis.

Refugee Processing Center (2015) Admissions and Arrivals, January 2015. http://www.wrapsnet.org/reports/AdmissionsArrivals (accessed 10 April 2015).

Robins-Wright, L. (2014) Refugee Resettlement, Impure Public Goods, and Domestic Responsibility Sharing: Evidence from the United States, Canada, and the European Union. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Paper presented at Nordic Migration Research Conference, Panel “Researching the Resettlement of Refugees in Europe”, 13–15 August.

Simich, L. (2003) Negotiating Boundaries of Refugee Resettlement: A Study of Settlement Patterns and Social Support. Canadian Review of Sociology/ Revue canadienne de sociologie, 40(5), 575–591.

SRF (2015) Wie die Schweiz syrische Flüchtline auswählt. 24 March. http:// www.srf.ch/news/schweiz/wie-die-schweiz-syrische-fluechtlinge-auswaehlt (accessed 10 April 2015).

Suter, B. & Magnusson, K. (2014) Perceptions and Experiences of Resettlement of Burmese and Somali Refugees in Sweden. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Paper presented at Nordic Migration Research Conference, Panel “Researching the Resettlement of Refugees in Europe”, 13–15 August.

Tip, L., Collyer, M., Brown, R. & Morrice, L. (2014) Optimising Refugee Resettlement in the UK: A Comparative Analysis. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Paper presented at Nordic Migration Research Confe-rence, Panel “Researching the Resettlement of Refugees in Europe”, 13–15

Troeller, G. (2002) UNHCR Resettlement: Evolution and Future Direction. International Journal of Refugee Law, 14(1) 85–95.

UNHCR (2003) Refugee Integration and Resettlement in Southern South America. http://www.unhcr.org/3fc5c6474.html (accessed 11April 2015). UNHCR (2004) Protracted Refugee Situations. Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme, Standing Committee, 30th Meeting, EC/54/SC/CRP.14. http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4a54bc00d.pdf (accessed 11April 2015).

UNHCR (2011) UNHCR Resettlement Handbook: Division of International Protection. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR (2013) UNHCR Global Projected Resettlement Needs. http://www.

unhcr.org/51e3eabf9.html (accessed 10 April 2015).

UNHCR (2014a) World Refugee Day: Global Forced Displacement Tops 50 Million for First Time in Post-World War II Era. 20 June. http://www. unhcr.org/53a155bc6.html (accessed 10 April 2015).

UNHCR (2014b) UNHCR Global Projected Resettlement Needs. http://www. unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home/opendocPDFViewer.html?docid=543408c4 fda&query=resettlement%20needs (accessed 10 April 2015).

UNHCR (2014c) UNHCR Resettlement Handbook, Country Chapter: Canada. http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ecb973c2.html (accessed 10 April 2015).

UNHCR (2014d) UNHCR Resettlement Handbook, Country Chapter: Australia. http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ecb973c2.html (accessed 10 April 2015).

UNHCR (2014e) UNHCR Resettlement Country Chapter: Iceland. http:// www.unhcr.org/3c5e58384.html (accessed 10 April 2015).

UNHCR (2015) Written statement at Third International Humanitarian Pledging Conference for Syria. Remarks by António Guterres, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Kuwait City, 31 March 2015. Van Selm, J., Woroby, T., Patrick, E. & Matts, M. (2004) Study on the

Feasi-bility of Setting Up Resettlement Schemes in EU Member States or At EU Level, Against the Background of the Common European Asylum System and the Goal of a Common Asylum Procedure. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Worland, S. (2010) Displaced and Misplaced or Just Displaced: Christian Displaced Karen Identity after Sixty Years of War in Burma. Brisbane: University of Queensland, unpublished PhD thesis.

Zetter, R. (2015) Protection in Crisis. Forced Migration and Protection in a Global Era. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

RESETTLED REFUGEES IN SWEDEN:

A STATISTICAL OVERVIEW

Pieter Bevelander

Introduction

Over the last five or six years, immigration to Sweden has been at an all-time high, at close to or more than 100,000 individuals annually; net migration has fluctuated at around 50,000+ individuals yearly during this period. Compared to earlier peaks of immigration to Sweden, in the late 1970s and during the Yugoslavian Civil War in the early 1990s, these recent consecutive years well exceed those earlier years of high immigration (Bevelander 2010; Emilsson 2014).

Although migrants’ reasons for entering Sweden are very diverse, a significant proportion of the immigration to Sweden over the last 15 years, as depicted in Figure 1, consists of individuals who seek asylum and who subsequently gain residence. Equated with the total number of immigrants or refugees, the so-called resettled refugees who are the topic of this volume, are relatively few, with an annual number of 1,500 to 2,000 individuals. Last, but not least, family reunification migration forms a significant part of the yearly inflow. These migrants are, to a large extent, connected to earlier refugee migration, but the flows are also partly due to the migrants’ international marriages with natives.

Although these resettled refugees are few in number compared to other admission categories, but high in political interest, the main aim of this chapter is to map their demographic, geographic, educational and labour market status in Sweden. In order to do this,

we use a special outlet of the Swedish register database STATIV for the year 2012. This database includes, inter alia, demographic, geographic and socio-economic information for each individual. In the case of immigrants, migrant-specific information such as the country of birth, citizenship, years since obtaining a residence permit and admission category is available. The information on admission status is quite important for this study since it makes it possible to distinguish between refugees who seek asylum at the border and subsequently gain access to a residence permit and refugees who are directly resettled through the Swedish resettlement programme. The current study is also able to track the demographic, educational and labour market status of a number of resettled refugee groups who have not previously been studied for Sweden (see Bevelander 2009). The individuals concerned are from Afghanistan, Colombia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Myanmar and Somalia and, together, they make up the majority of the resettled refugees in Sweden over the last 15 years. The employment rate is based on standard measurements by Statistics Sweden and is calculated according to whether or not an individual was employed for more than 40 hours during the month of November and had an income from work equivalent to one “base value”, about 45,000 Krona in 2012.

Figure 1. Immigration to Sweden, 1998–2013

Source: Migrationsverket. 0 20 000 40 000 60 000 80 000 100 000 120 000 140 000 1998199920002001200220032004200520062007200820092010201120122013 Asylum seekers Refugees Resettled refugees Total immigration Family reunification

Earlier studies

Studies for Sweden which analyse the labour market integration of refugees claim that refugee integration into the labour market is dependent not only on the human capital acquired in the home country but also on the migrants’ investment in host-country human capital and, even more, in their labour market experience in the host country (Rooth 1999). Others studies stress the internal migration of immigrants/refugees as important factors related to the obtention of employment. For example, Rooth & Åslund (2006) show that choice of city and the labour market situation are important factors explaining labour market integration. Moreover, immigrants move to areas with relatively higher shares of immigrants in the popu-lation, i.e. the bigger cities (Bevelander et al. 1997). Hammerstedt & Mikkonen (2007), studying the short-term mobility of refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina, found that males who quickly moved to another place on arrival in Sweden had a lower probability of becoming employed than those who stayed. They argue that the host-country language and knowledge of the labour market take time to acquire and that mobility, in the long run, can have a positive effect on the labour-market integration of immigrants. Moving to bigger cities mostly implies a renewed connection with a larger co-ethnic population and the opportunity to make use of ethnic networks. Bevelander & Pendakur (2009), studying the employment proba-bilities of refugees and family-reunion migrants in Sweden, show a clear difference in employment trajectories over time between resettled refugees, asylum claimants and family-reunion migrants. They discuss these differences in employment integration in terms of selection, integration policies affecting the various groups differently and social capital. Resettled refugees are housed in municipalities where housing is available but where employment opportunities are scarce and asylum-seekers have both resources and the possibility of settling where labour-market opportunities are available to them. Family-reunion migrants are likely to draw on the social capital acquired by family and friends already settled in the country (Beve-lander 2011; Beve(Beve-lander & Pendakur 2009).

In direct comparison, employment probabilities for refugee groups in Sweden do not substantially differ from those measured for the same groups in Canada (Bevelander & Pendakur 2014). Using