May 2012

Thesis-Project – Interaction Design Master at K3

Malmö University

Sweden

a Master’s Thesis by Camilla Jusis

K3 - School of Arts and Communication

Malmö University

Master’s Thesis

Interaction Design Master Programme

Supervisor: Mikael Jakobsson

Examiner: Jonas Löwgren

Malmö May 2012

Abstract

The thesis project underlines the importance of designing calm and subtle technologies, by exploring how mobile communicative technologies, such as cell phones, could notify their users about incoming information in a more natural, and non-intrusive manner. The aim of the thesis was to find a way for cell phones to act more appropriately in public and social settings, where they now often are considered intrusive due to their uninhibited manifestations.

The thesis provides a theoretical understanding of how normative expectations of cell phone conduct are constituted and maintained within public and social settings. The theories are further grounded in practical work, where the project employ user centered design methods and techniques to, in a collaborative manner, together with users explore the research field to generate insights. Solutions have further been prototyped and evaluated together with users in their everyday settings.

Taking inspiration from calm technology, the project looks into how information can be notified, in a more subtle manner in the periphery of the user’s attention. Users’ own priming abilities have been considered as a personal way to recognize the notification and to further associate it as relevant information.

As a solution for intrusive cell phones, the thesis proposes Knot; a signature based notification system, which builds on friends’ abilities to recognize each other’s characteristic traits. The system consists of a notification rope, which is a free standing phone accessory that twists and turns, when new information is arriving to the user’s cell phone. It can present whom the information is from by shaping itself into the sender’s representative Knot-signature. If the user can recognize the signature, it will immediately trigger a m eaningful association to the person who sent the information.

The solution builds upon the restrictiveness between those who can associate a certain signature to a certain person, and those who cannot. For those who have the ability to associate to the signature, its role as a notifier will become meaningful and informative, while for others, who do not share this ability, the signature would be subtle and meaningless, and hence not interfering. The thesis exemplifies how interfaces could provide users with output in a more natural way, by considering users’ previous skills and knowledge, and primarily their priming abilities.

Keywords

Notifications, Mobile Communicative Technologies, Cell phones, Output, Modality, Calm Technology, Periphery, Priming, Ambient Display, Interaction Design, Embodied Interaction,

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to my supervisor Mikael Jakobsson. I am sincerely grateful for the great feedback, good critiques and valuable discussions during this thesis project. My learning process has been tremendous, thanks to the insights and knowledge that you have shared during our meetings.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Daniel Spikol, who introduced me to the field of interaction design, and to Samir Drincic, who inspired me to continue with my studies.

This project would not have been possible without the contribution of Tobias Jeppsson, Matilda Andersson, Roger Andersson Reimer, Christofer Leyon, Erik & Malvina Ohliv, Sara Drincic Jeppsson, Unsworn Industries, Livia, Nicklas, Sveta, Tommy, Anders & Madeleine, and the Jeppsson, Appelros, Althén, Lindberg,

Lavesson Families.

Further thanks go to all of my fellow students and the supportive staff at K3; especially to Mette Agger Eriksen & Amanda Bergknut.

1 Introduction

2 Theoretical Framework

3 Related Work

4 The Design Process and Methods Used

5 Empirical Research

6 Simulated Exploration

7 Making Sense of Findings

8 Inspiring Requirements: How to Perceive Subtle Information

9 Concept Development

10 Concept Evaluation I

11 Inspiring Requirements II: How to Withdraw to Emphasize

12 Knot – The Final Concept

13 Concept Evaluation II

14 Reflection and Research Outcomes

Conclusion

Appendix – The Knock Concept

Referenses

Table of Content

6

10

16

20

23

32

37

41

43

45

47

49

54

60

65

66

67

1 Introduction

Performing at the Jewish Orthodox synagogue in Presov, the Slovakian virtuoso violinist Lukáš Kmit was just about to enter a pianissimo part within his piece, as he suddenly got accompanied by a familiar tone. It was the famous Gran Vals played in perfection by an audience member’s cell phone. After a disapproving glare towards his audience, Kmit decided to recant their attention. By including the phone’s ringtone within his performance, Kmit battled the phone by its own means. He delivered a sophisticated critique which not only became a sensation within the synagogue, but which started to travel the Internet a half year later. The short video of a distressed Kmit quickly became an Internet phenomenon, which further brought up discussions regarding cell phones’ way of acting, cell phone conduct in public settings, and about the cellular industries’ responsibility for incidences as these (Ferencik, 2011; Marcus, 2012).

Interruptions, as the one mentioned above can be seen as a byproduct of our modern era. Through our dedicated use of mobile devices, we are now expected to constantly be available and to be informed anywhere, and at anytime. We are, consequently, surrounded by a density of notifications; beeps, flashes, vibrations and other alerts have become common elements in our everyday life. Their presence continues to grow in hand with the increasing amount of mobile devices and their ability to provide us with more personalized information, which in turn, all need their certain cues. The growing density of notifications has led to an overwhelming manifestation, as cell phone users already have to distinguish between numerous of alerts coming from their and other’s devices. The large amount of notifications is not only causing users to face notification overload - the challenge of keeping up with incoming information – but their frequent presence also causes an outrageous amount of interruptions (Dantzich, 2002).

Cell phone notifications are in most cases only intended to reach one specific user, still - and as exemplified in Kmit’s situation - they often affect the surrounding setting as well; making notifications a social issue. This is due to notification’s exaggerating way of acting, which is inherited from the land line phones’ way of alerting incoming calls. Considering the land line phone’s stationary position, more intrusive alerts are needed to obtain attention from a distance. Its specific purpose is to be interfering enough to interrupt users in their current task, so that they in time can answer the call. They are intentionally designed to cause interruptions as a way to get the user’s attention. Unfortunately, the use of similar alerts does not work as well for cell phones, since the proximity between the device and the user’s body is in constant change, due to their possibility of mobility and random repositioning (Haddon; 2009, pp.54-55). An intrusive loud notification can go from being suitable within one context to quickly become inappropriate and disruptive in another.

The use of a cell phone is in many ways more diverse in comparison to the land line phone, and so also the information it provides. Not all incoming information is highly prioritized by the user and therefore not in need of an alarming alert. But even if today’s mobile devices are highly developed in many aspects, their way of notifying incoming information have not changed radically from the traditional idea of getting the user’s attention at any cost. Cell phones and their notifications are, consequently, often perceived as annoying and interfering elements within our society (Wei and Leung, 1999). Their intrusive behaviors are now such a common element in our everyday lives that we have started to adapt ourselves around their existence. “Free zones”, where cell phone usage is undesirable, have been established formally as an attempt to regulate use, or emerged informally as social norms within certain settings (Ling, 1997). In some establishments, manifestations in terms of notification alerts are fully prohibited. But even in these settings, it may be hard to evade their presence. Cell phones’ possibility of extending our connectivity to others have become an indispensable part of our lives, which we only, through great resistance and unwillingness, switch off (Wei and Leung, 1999). In turn, places that previously were considered to be cell phone free zones are slowly becoming infected by the unavoidable density of notifications.

Overwhelming notification rampage is not a result of an increased acceptance within society, but a consequence of the lack of alternatives. Cell phones inappropriate way of acting have until now only been resolved by switching between different output modalities; attention demanding sounds and beeps can be exchanged to a lesser extent by choosing tactile vibrating ones. Modern cell phones can switch between varieties of notification modalities such as: visuals, haptics (vibrations), sound and light. There are, however, two reasons for why these types of configurations fail as satisfactory solutions. First of all, these configurations depend on the user to both judge the situation and to further manually adjust the device accordingly. Consequently, and unfortunately, these adjustments are often forgotten or simply neglected (Fallman and Yttergren, 2005). The second reason is that by adjusting the cell phone, users inevitably make a decision between keeping themselves informed, or to not cause any interference to their surrounding (Hansson and Ljungstrand, 2000). The need of a decision is due to output modalities’ restrictive characteristics, where informative modalities - such as audio - are more noticeable, hence more intrusive, and where less intrusive modalities – such as light, visuals and haptics – evidently are more subtle but less noticeable, and for that reason often less informative for the user.

The use of less intrusive modalities is still the best way to avoid uncontrolled outburst within social settings. But as previously mentioned; their subtle abilities, consequently, make them less noticeable for the user. Light and visuals both have to be within the user’s peripheral vision to be seen, while vibrations work as intended if the device is placed near the user’s body. The restricted selection of placements where these more subtle modalities work, consequently, contradicts with the purpose of a mobile and repositionable phone. Correct placement of the device is therefore often bypassed by many users, with the inevitable outcome of them missing incoming information.

1.1 Research Issue and Question

The inadequacy of current notification modalities is causing the cell phone user to deal with a never-ending decision of whom to satisfy; the surrounding setting or the user’s own needs. The presumed reason for why a user owns a cell phone is that the user wants to be reached by incoming information and thus be notified about it. The user therefore chooses a more informative modality, which often is considered intrusive in many social settings. It is therefore more likely that the user tries to act according to the setting’s established norms for how to behave and hence configures the cell phone to a less intrusive modality, even though, this may increase the risk of the user not noticing the subtle notifications.

Due to the current notification modalities’ insufficiency, users are constantly obligated to manually adjust their cell phones by shifting between the modalities. It is a practice that often is forgotten or ignored due to its tediousness. This thesis project therefore aimed to reconsider the need of shifting between modalities, by exploring possibilities for how mobile communicative technologies, such as cell phones, could be designed to act in favor of both the user and their present surrounding.

The research question the thesis aimed to answer was:

How can we design mobile communicative technologies that would act more appropriately to established norms in public and social settings, while still provide their users with informative notifications?

The thesis project aimed to explore possibilities of more favorable notifications, by investigating cell phone practices within public and social settings. It would, from a user centered perspective employ participatory methods and prototype techniques within the users’ own familiar settings, to uncover insights for how mobile communicative technologies could appropriate their act to established norms in social settings.

1.2 Preliminaries

The scope of the thesis project was limited to a study of Swedish cell phone users, where Swedish residents’ cell phone behaviors were studied in relation to social and cultural norms in Swedish public settings. The design work was therefore heavily influenced by participants’ cultural background, as their insights and desires were used as a fundament during the design process. The project aimed to have a holistic view on cultural aspects which might affect, or be affected by the design solution. I will in the following section discuss some cultural aspects that have been considered and valued during the project.

Sweden has the world’s leading information and communication technology infrastructure and has a

population that through history has been accustomed to embrace technical inventions (Dutta and Mia, 2011). There is also a strong established cell phone culture amongst the population, although, there are no exact numbers on how many mobile devices there are within the country, but according to the Swedish Post and Telecom Agency’s semiannual report there are approximately 13.1 million active subscriptions and pre-paid cards spread amongst the population of 9.3 million (2011). Cell phones are now widely used in many aspects of a Swede’s daily life, and where new cell phone services rapidly are introduced, which in turn, increases the cell phone’s presence and importance within the Swedish society.

Swedes have a peculiar social behavior and mentality, which is interesting to study. In similarity to the other Nordic countries, Swedes preserve a private sphere through strict social boundaries; that regulates both the physical distance to others, and who they allow themselves to interact with. With foreign eyes, this social behavior may seem cold and distant. However, when seen from a Swede’s perspective this is a management of the contact with others, while still being able to protect a sense of self. According to sociologist Åke Daun (1996), this behavior has originated from a tradition of solitude and hard labor; where Swedes traditionally lived distanced from each other and only socialized with others when practical work had to be done. This mentality is still profound; where any socialization with strangers – as a conversation – has to have a purpose. Daun (1996, p.231) also underlines that this social mentality is a reason for why Swedes are fond of any technical formalizations, as long as they reduce the need for face-to-face interactions.

In contrast to Swedes’ preservative notion of the private sphere, Baron and Segerstad (2010), have in their cross culture study - regarding cell phone behavior in public places - observed that Swedes tend to view any outdoor areas as public place, even if they are legally owned by someone. By allemansrätten (meaning the ‘right to roam’) individuals have the right to use other’s land without seeking permission (ibid, p.15). This, however, does not mean that persons are allowed to use the public place as they like; since every setting has their normative expectations. Baron and Segerstad underline that Swedes tend to be “relative quiet” in public place, but that they were most tolerant of other’s “self-expression”, in comparison to inquiries done with Americans and Japanese residents (ibid, pp.15-16).

An aspect which often is forgotten when mobile communicative technologies are designed for the Nordic countries is the change of seasons. Mobile devices can for many reasons not be used as designers had intended during winter. One non-technical reason is the layers of clothing, which affects how the users will utilize the device, and where they will place it. Many Swedes have pointed out the faulty relationship between touch screens and gloves. To evade this kind of design complications, the thesis project held a holistic view of cultural aspects that may affect or be affected by the design.

This report will include keywords which may need some further clarification.

Notification is a collective description of any event occurring on a mobile device, which the user may want to

be informed about. It can be an incoming phone call, text message, calendar entry, application update or even an indication for low battery. They are often accompanied with an alert to attract the user’s attention. This thesis project mainly focused on notifications that derive from a communicative instance, such as a phone call or text message from another human.

Modality is a particular sensory channel in which the information is presented to the user. The modalities

exploited by current cell phones include visual, auditory and tactile. I will in this project separate light sources –such as light-emitting diodes (LED) - from visuals, as visuals here will define elements within the graphical user interface (GUI).

Multi-Modal describes the use of a combination of different modalities to represent information. This

is a good way to extend the call out for the user’s attention, as it aims to stimulate a numerous senses at once. Current phones often use a combination of visuals, sound and haptics, to in a way draw as much attention as possible.

2 Theoretical Framework

Intrusive cell phone notifications can be found in almost any urban public place: teenagers’ repeated beepings that fill the ambiance of the bus ride home; a co-worker’s mysterious vibration underneath the meeting table; an elderly woman’s suddenly ringing handbag at the local restaurant. Despite all these common observations in public, only a few social studies have observed the cell phone’s intrusive nature and its effects on society (Ling, 2004a, b, 1997; Wei and Leung, 1999; Campbell, 2007). These social studies all draw the conclusion that cell phones are most interfering in public and social settings, where they inevitably affect others. The studies also underline that some public settings are more sensitive to intrusive cell phones than others. To be able to understand why the cell phone conflicts with these settings, we first have to establish an understanding of what constitutes a public place.

As initiated in the beginning of this chapter, this framework will make use of social studies to obtain a broader understanding of the social factors that have a fundamental role regarding the research issue. The use of sociological perspectives has during the last decades proven to add valuable considerations to the research field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI). Not only have research methods and techniques, as for example, ethnography been provided, but also a broader understanding of how human actions and interactions take form (Dourish, 2001, pp.56-62). The sociological perspective also allows us to understand the social construction of the place in which these actions and interactions are conducted.

The entry of sociological perspectives within HCI has influenced researchers to critique the field’s

perspectives of “space” and “place”, which for long have been built on a Cartesian model; with its belief that user’s activity and interactions are derived from the spatiality and the temporality of the space (Fallman and Yttergren, 2005; Fallman, 2003; Dourish, 2001; Harrison and Dourish, 1996). Harrison and Dourish (1996) critique this perspective by making a critical distinction between “space” and “place”, by diverging them into physical and social attributes. They argue that “space” is a physical structure of the world; a three-dimensional environment in which objects and events occur. While “place” on the other hand, is a valued and meaningful sense of space that derives from people’s involvement and interaction with the artifacts and people within a space, rather than only from the spatiality of the space as the Cartesian model proposes.

Harrison and Dourish notion of “place” as an outcome of peoples’ involvement with space stands in direct relation to Martin Heidegger’s phenomenological philosophy (1927). Heidegger rejected Descartes’ famous statement: “cogito ergo sum” – I think, therefore I am – and the mind and body dualism which it brought; that the conscious is a mental phenomena of reasoning and meaning, which is distanced from the physical phenomena of our body’s experience of the mundane existence. Instead, Heidegger argued that we need to be in the world in order to think; that our human entity’s existence – Dasein – within the world further shapes the way in which we understand the world. Heidegger further underlined that dasein’s “being in the world” is fundamentally different from other objects’ existence within the world, since dasein is not simply a matter in spatial and temporal space, but rather an entity that encounters the world by being involved with it (Heidegger, 1927; as cited in Dourish, 2001; Fallman, 2003).

In relation to Heidegger’s notion of being in the world, Dourish writes that “embodiment is the common way in which we encounter physical and social reality in the everyday world” (2001, p.100). A world which through Heidegger’s notion is organized for us to derive meaning, both in the ways in which we encounter it and in the way in which it makes itself available to us (Heidegger, 1927; as cited in Dourish, 2001). Dourish makes it clear that our embodiment is more than a physical manifestation within the world, but rather a participative status with the everyday mundane experience to derive the meanings, theories and abilities for actions that are established within the world (Dourish 2001, p.125). But meaning is also created through these encounters.

2.1 The Public Place – The Core of Shared Meanings and Practices

Dourish writes that “[The world] shapes and is shaped by the activities of embodied agents” (ibid). He further defines “embodied interaction”, as the creation, manipulation and the sharing of meaning through the engaged interaction within the physical and social reality of everyday world.

Sociologist Erving Goffman noticed - in his studies regarding the public place - the duality of how meaning both can derive and be created within the same place. In his book Behavior in Public Places (1963a, pp.4-22) Goffman described public places as “gathering places” which could be any space, situation or occasion where face to face interaction could take place. But for this interaction to take place, a social arrangement with other’s in the co-presence of certain proximity has to be acquired. According to Goffman: “persons must sense that they are close enough to be perceived in whatever they are doing, including their experiencing of others, and close enough to be perceived in this sensing of being perceived” (ibid. p 17). It is thus in the exchange of awareness of each other where we start to negotiate the shared meanings of the public place.

Harrison and Dourish build further on Goffman’s notion of the co-presence, by stating: “The sense of other people’s presence and the ongoing awareness of activity allow us to structure our own activity, seamlessly, integrating communication and collaboration ongoingly and unproblematically” (1996, p.2). The meanings which public places carry are therefore social meanings, which are - according to Harrison and Dourish - rooted in the practices and understanding of the community in a place (ibid, p.8). However, Goffman (1983) clarified that the shared meanings are rather a result of “interactional orders” than social orders, since the meanings are sculptured from the situated interaction with the co-present. They are hence created by the practices and the understandings within a community in a certain time and space, than only rooted within its spatiality and temporality. In public places these practices can take their form of shared norms, rules and rituals, which according to Goffman, further reflexively affirm and create the “interactional order” for how the situated interaction should be performed within a place, but also the “normative expectations” for how we judge ourselves and others to behave (1983, 1963b).

2.2 We Obtain Meaning and Act Appropriately

Goffman’s notion of situated interaction is shared by Dourish, who claims that practice is “… knowledge that is shared by a particular set of people based on their common experiences over time” (2001, p.90). But Dourish also emphasizes the importance of the place’s spatiality as a foundation for these interactions. As previously mentioned, Dourish and Harrison had framed space as a physical structure. This structure both provides opportunities and constrains for interactions to take place (Harrison and Dourish, 1996, p.7). For example, a small meeting room with comfortable chairs and a round table may support a particular kind of conversation than a meeting in a large auditorium would (Fallman, 2003). Even though the space’s structure grounds what kind of interaction that might take place, Dourish further claims that “… space is not enough to account for the different kinds of behaviors that emerge in different settings. Two settings with the same physical configurations and arrangements of artifacts may engender quite different sorts of interactions due to the social meaning with which they are invested” (2001, p.89). A public place hence reflects the emergence of practice of a certain community. As the community changes, previous established practices within the place, such as meanings, norms, values, rituals etc, are also likely to be changed.

Fallman clarifies that our behavior is not guided by the physical properties of the settings in which we interact, but rather by the social norms and agreements within these settings (2003, p.153). We are framed to behave accordingly by the social conventions and their normative expectations. Our management of conduct to fulfill these expectations was studied by Goffman (1959) who claimed that; since our social identities are shaped by our status and role in society, we therefore constantly perform role-plays as a way to fulfill the normative expectations. As actors we choose to act in roles which we assume have positive social values and that will integrate us well within the social setting. When a new role is established; as it is accepted by the social setting (the audience), it has to further be maintained and performed. If the actor succeeds with his

performance, the audience will see him in the way in which he wants to be seen. The actor, however, has to fulfill the normative expectations to be able to perform the role well; only then can he maintain his desired social identity (Goffman, 1959, pp.25-40). To act in the contrary to the normative expectations may lead to social sanctions or doubts amongst the co-present, since the misuse of the public place is in the eye of the beholder (Goffman, 1959; as cited in Ling, 2004, p.127).

We do not only maintain our roles through the way in which we act, but also through the setting and the equipment which we choose to surround ourselves with. According to Goffman, we constantly make use of “sign equipment” such as costumes, décor and props. Through his theatrical metaphor, we can understand that these equipment are used to enhance our roles, and to express a sense of self in which we want to be seen (1959, pp. 28-33, 111-112). In line with Goffman’s sign equipment, sociologist Richard Ling observed how teenagers’ used their cell phones as an extension to showcase their identity (2004a pp.104-105). Ling therefore concluded that a cell phone is more than a communication device, but if one only examines it by its potential as a communication medium, it is easy to miss the important social and symbolic

meanings that the device simultaneously may hold (2004b, p.4). Silverstone et al. describe this dual nature of communication technology; where they on one hand only are simply communication devices, while on the other, physical objects that occupy space with a certain aesthetic, and which through their embodiment display their owner’s status and position in society (1992, pp.15-28). The cell phone can in this way be used as sign equipment, and by showcasing it in public settings it will become part of our social identity, or rather an extension of our identities. Since the cell phone is an object of display with functional features, Ling compares it to jewelry such as belt buckles, watches, and broaches. But compared to these functional jewelries, the cell phone is risky sign equipment, since it is not in full control by the owner, and can therefore be set to life by others who call in at the wrong time (1997, p.5).

2.3 Why Cell Phones are Considered Intrusive

According to Ling, a cell phone’s spontaneous eruptions in public settings often derive further actions, where actors around it must prepare to recast as a way to appropriate themselves to the new situation (2004b, p.10). Ling observed that due to a cell phone’s ringing:

“Conversations have to be put into pause mode, the person who’s telephone rings must fish around for the device and start the answering sequence, the erstwhile co-present persons have to quietly fade into the background while the telephonist has to prepare to deal with an parallel portion of his or her life” (ibid). Ling’s observation shows how the cell phone can be considered intrusive on many levels. Not only through the interruptive ringing per se, but also in how the interruption creates a detour of actions from what might have been planned. A third aspect is that the cell phone through its notifications invites the owner to enter a private sphere; a self-selected exclusion from the co-presence in the public setting.

Private spheres are though naturally occurring. It is possible to in any public place (especially in Sweden) observe the certain boundaries we have in relation to the co-present. Ling constitutes from a Scandinavian perspective that: “… we mark our relationship to others to a certain degree with the way in which we manage and use boundaries” (2004b, p.6). The private spheres indicate whom we allow ourselves to interact with, and in turn restrict and constrain the movements of other individuals surrounding us. These private territories may be set by our own presence and belongings, or by the physical structure of the space which we encounter (Harrison and Dourish, 1996). Goffman writes that:

“Some [private territories] are “situational”; they are part of the fixed equipment in the setting (whether publicly of privately owned), but are made available to the populace in the form of clamed goods while-in-use. Temporary tenancy is perceived to be involved, measured in seconds, minutes or hours, informally exerted, raising constant questions as to when it terminates” (Goffman 1971, p.29).

But these private territories can only be ritually established through negotiation with the co-present; to get their permissions and consents. When a cell phone goes off within a public setting an “interactional ritual of reciprocal talking and bodily attitudes” will according to Leslie Haddon begin (2009, p.59). It is an implicit negotiation between the co-present and the phone owner, where they may display their normative expectations of private and public divisions of the space. Through this ritual they share their experience and establish meaning for how to further appropriate behaviors. If the normative expectations are shared by the phone owner, he will try to appropriate his behavior accordingly, by for example, turning his body away from others, or by crouching his body inwards while answering the phone (ibid, pp.57-59). In this way, the phone owner communicates and negotiates an establishment of a private sphere, where he deliberately takes a distance from the public. However, phone owners who distance themselves, without the co-presents’ consents, may be perceived as absent present; as they prioritize the distant other over those who are physically co-present (Campbell, 2007, p.739). Their behavior of taking space is often perceived as an offense, as it obligates the co-present into an uncomfortable social state where they are presumed to wait for the phone owner to finish their private errand, while they often are forced to eavesdrop (Ling, 1997, p.12).

The notion of how technologies constitute private spheres is nothing new (Haddon, 2009). This was noticed by sociologist Georg Simmel at the turn of the twentieth century. His shocking experience, of modernity in the metropolis, generated theories of how the people living in the cities adopted an approach of indifference. Simmel observed how the urban spaces fostered an attitude of reservation and a reluctance to engage with anonymous others. He experienced their silence as if they rather privatized the businesses of everyday life, than mutually recognizing and emotionally responding to each other (Simmel, 1903). A century later, Geoff Cooper reviewed Simmel’s observation in relation to how we now use cell phones in our public places. He writes in his article The Mutable Mobile, that:

“No longer is the private conceivable as what goes on, discreetly, in the life of the individual away from the public domain, or as subsequently represented in individual consciousness; furthermore, although it is still the case that the co-present tend not to speak to each other, they can now have conversations with remote other which are (half) audible to all” (2001, p.22).

What Cooper observed was that these constructed private territories tend to make us ignore others who are in close proximity; a condition which Goffman referred to as “symbolic fences” and Ling as “fictive curtains” (Goffman, 1971, p.29; Ling, 2004, p.126). Cooper also underlined how we now rather socialize with remote others through the medium, than socializing with the co-present.

We are no longer restricted to socialize at a certain physical place or time, as we now can attain many different places wherever and whenever we want. Cell phones are, according to Wei and Leung: “changing the significance of space, time and physical barriers to person-to-person communication” (1999, p.12). They are dissolving the boundary between public and private spaces, as they “[facilitate] a shift of social interaction from private to public places, and conversely from public to private” (ibid). The possibility of accessing multiple places at once brings, nevertheless, a concern for how to balance the social interactions that are occurring simultaneously within the settings. Ling writes: “... the use of the mobile phone in interpersonal situations introduces a new element into out interaction with others. The mobile telephone intrudes into the complex web of interactions, and it demands that they be rearranged” (2004a, p.130). The constant shifts between public and private spheres, which the cell phone contributes to, have made it critical but difficult for cell phone users to appropriate their behaviors to settings’ norms. As a result, cell phone users often unknowingly cross the negotiated boundaries between the private and the public, while trying to juggle between the public setting and the remote setting provided by the phone. Cell phone users are therefore often seen acting inappropriately in public settings (Wei and Leung, 1999, p.12).

In contrast to humans’ attempts to appropriate their actions and behaviors according to a setting’s normative expectations, cell phone’s notifications act static in every setting, unless they are adjusted by their owners.

These adjustments are nevertheless often forgotten or ignored, and since cell phones do not adapt

themselves accordingly; their way of acting often conflict with settings that are less tolerant for inappropriate behaviors (Campbell, 2007; Fallman and Yttergren, 2005; Fallman, 2003). In Relations in Public, Goffman discusses “modalities of violations” and offenses to others. One mentioned offensive modality was “sound interference”, which according to Goffman is when a violator fills up his or her space with sounds, to further violate the territory of others by spreading the sound over a longer than proper distance (1971, pp.33-51). Goffman’s notion of sound interference is comparable to the cell phones ringing in public places; which does not only affect the owner, but everyone in the co- presence. Notifications therefore often conflict with settings that are less tolerant for noisy outbreaks, for example in situations where the social interaction is central and where a common focus of attention is needed, or in situations where it is difficult to cover the audible traces of their existence (Campbell, 2007; Ling 2004b).

2.4 Previous Solutions

Several attempts have been made to tame cell phones’ intrusive behaviors and to assist users in choosing suitable notification modalities. But, according to Fallman and Yttergren, most of these current solutions are built upon a naïve Cartesian model which does not support the situatedness or the involvement of human action (2005, p.5). They exemplify and critique two solutions based on this model. The first one makes use of the spatiality of a geographical location to support the normative conduct that has emerged from the patterns of human behavior and interactions within the space (Fallman and Yttergren, 2005; Harrison and Dourish, 1996). This is done through tagging a certain location with beacons, such as Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) tags, which hold information about how the cell phones should act according to the normative expectations within that place. The information is received by the cell phone as the user enters the location; the phone in turn reacts by self-adjusting its modality appropriately. A similar occurrence happens as the user and his cell phone leaves the location, but then, the modality shifts back. Fallman and Yttergren also exemplify a temporal solution, built upon the ability of synchronizing the desktop computer’s calendar with the calendar in the cell phone. This ability hence sets the foundation for a time-based notification system, where one simultaneously would schedule the cell phone’s behavior according to the scheduled activity.

Even though these exemplified solutions have problems of their own, such as a time-based solution would require the user to constantly provide it with information, they also have issues in common. As previously mentioned, they are both built on a Cartesian way of thinking and are hence structured by the belief that users’ activity and interactions are derived from the spatiality and the temporality of the space. This belief requires the features of the world, and our interactions with it, to be stable, objective phenomena (Dourish, 2001). In other words, for these solutions to work as intended we have to use them accordingly to how they were structured. It is possible to argue that they are modeled after our everyday behaviors and actions, and that they for this reason would seemingly work. But these kinds of model based structures have been critiqued by Lucy Suchman (1987), who argues that human action is not as rational, planned, and structured as these systems conceptualize it to be, but rather improvised, as a moment-by-moment “situated” response to immediate needs that emerge out of the interaction with the physical and social setting.

To design a notification system that would adapt to our “situated actions” would be challenging according to Fallman (2003, p.162), who claims that there is no easy way to capture human’s understanding of a situation, so it further could be used as input data for a computational system. Instead Fallman and Yttergren underline how the norms for cell phone conduct derives from the situated actions and interactions with the

“physio-social context”, rather than from the specific location in time (2005; Fallman, 2003). A notification system should therefore support the situated actions and interactions, rather than try to understand and model itself around them. Fallman and Yttergren exemplify their notion by presenting a democratic inspired concept; where a phone’s notification modality automatically would adjust itself accordingly to the most common modality used within the community of a certain location at a certain time. When two or more cell phones in close proximity would sense each other’s presence, they would start to negotiate about which

modality that would be most appropriate to apply within the certain setting. In theory, this means that the user’s cell phone would always be set in the most appropriate modality in relation to the current setting’s norm. Nevertheless, Fallman and Yttergren underline weaknesses with their own system; considering situations where the user wants or needs to be notified regardless of the current norm, but where the community has appropriated all cell phones in to using subtle and less informative modalities (2005, pp.8-9). The issue that Fallman and Yttergren state, is, and will be a consistent problem as long as designers believe that the solution for appropriating notifications is to shift between subtle and informative output modalities. This thesis project hence aimed to reconsider the need of shifting between modalities by exploring

possibilities for how notifications could be both subtle and informative.

2.5 Rules of Beeping

The aim of this framework has been to emphasize the user as an engaged embodied actor within the world; where his situated actions and interactions with the physio-social context both derive and create meaning. Dourish’s notion of embodied interaction gives us an understanding of how we create, manipulate and share norms within a public setting, and how these norms in turn determine which notification modality that is most appropriate to use. Embodied interaction also relates to how we choose to use our cell phones. As artifacts of our time, we engage with these devices on a regular basis; where we through embodied interactions manipulate, share and establish new meanings for their use and purpose. This kind of creation and sharing of meaning was exemplified in Jonathan Donner’s study The Rules of Beeping (2007) where he observed how people created a communicative practice of using missed calls as a cheaper alternative to the more expensive communication types of texting and calling. In this practice, a person would call a cell phone and then hang up before the cell phone’s owner could pick up the call. These types of communicative practices annoyed many, but for those who shared and performed them, a missed call could hold several meanings depending on whom and when someone had left them. The meanings could shift from “call me back” to more pre-negotiated instrumental messages as for example, “I’m done with my work, pick me up”, or just as a “poke” to announce that the person missed the other.

Donner underlined that this practice was a strong cost-saving rationale for the practitioners, while it unfortunately became a huge cost for the phone operators, who without revenue had to manage all the connections which crowded the networks. This example therefore shows how users’ shared meanings and actions may conflict with the predetermined notion of what the designer had in mind. Dourish clarifies how difficult it is for designers to predict the possible outcomes an artifact may enable, since they arise as the artifact is incorporated in users’ daily situated activities. He therefore states that it is “users, not designers, [who] create and communicate meaning” but that designers have a huge responsibility of providing the user with this opportunity (2001, p.170). Dourish suggests a shift in designer’s mindset for how to deal with this unfamiliar state. Instead of pre-defining how an artifact should be used, designers should, according to Dourish, open up the artifact’s resources to enable multiple forms of use and in turn allowing meaning to take form. Designers would then focus on how these resources could be designed to help users to understand the artifact, and in turn inspire them to appropriate and incorporate the artifact into their everyday lives (ibid, pp.167-173).The notion of an artifact that is open for users to incorporate with their own meanings has inspired this thesis project. The aim was to create an artifact that had the properties of an open material for the user to explore, re-form and where they were allowed to add their own interpretations and meanings. I hoped that by implementing the artifact into users’ everyday settings new meaning of its purpose and use would naturally unfold, regardless of how they choose to use it, because through their chosen actions and interactions with the material the artifact would take its form and in turn become meaningful.

3 Related Work

The thesis project began by looking into some related projects and studies regarding cell phone conduct, subtle outputs and informative cues. I will in this chapter present the most relevant projects with the objective to give a broad overview of how the issue of intrusive notifications previously has been tackled. I have also included studies regarding placement of the device, since I noticed a correlation between missed notifications and the cell phone’s repositionable abilities.

3.1 Studies on Phone Carrying and Placement

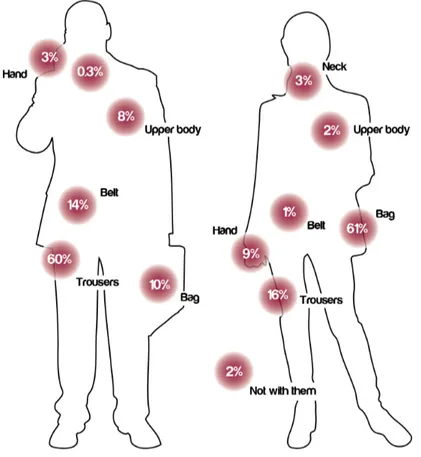

Cui, Chipchase and Ichikawa (2007) have conducted a cross cultural study where cell phone users within eleven different cities on four continents have been interviewed in the streets regarding their phone carrying habits. Swedes were unfortunately not studied, but as representative for Scandinavia were Finns from Helsinki. Cui, Chipchase and Ichikawa’s comprehensive study shows that there are cultural differences for how cell phones are carried, but that the main difference is between genders, regardless of location and culture. Their data shows that women generally used bags as the primary way to carry their phone, while men more often used their trousers’ pockets (Figure 1). According to their study, the carrying option had an impact on how a person would notice their phone’s notifications: “When carrying a phone in trousers pockets, approximately 70% of the participants claimed they always noticed the incoming messages or phone call. This rate was 50% for the participants keeping their phone in their bags” (ibid, p.485). Women’s positioning of their phones hence made them miss more notifications, in comparison to men. According to the authors; the reasons for people’s cell phone placements depended on “instrumental”, “non instrumental” and “contextual restrictions” (ibid, p. 487. Figure 2).

Figure 1: Locations where users usually placed their devices, according to Cui’s, Chipchase’s and Ichikawa’s study. The

percentages are mainly to give a comprehensive view of the study’s outcome. Some figures are rounded to simplify the illustration (Cui, Chipchase and Ichikawa, 2007).

Figure 2: Reasons for the cell phone’s placement, according to Cui’s, Chipchase’s and Ichikawa’s study

(Cui, Chipchase and Ichikawa, 2007, p.490).

A device’s position may affect the user’s ability to access it in time to catch a call. This is what Ashbrook et al. (2008) concretise in their investigation. They studied three common placements for current mobile electronics; the pocket, on the hip in a holster and on the wrist (ibid, p.219). The positions were evaluated according to their access time, i.e. the amount of time it took for a participant to retrieve the device and respond to their alerts while walking on a track within the laboratory. The researchers found that placing a device in a pocket or a holster “incurs a large time penalty when it comes to accessing the device—up to 78% of the total reaction time, while a wrist-mounted device allowed for consistently faster access” (ibid, p.222). The researchers further state that their study may help to explain why the participants in Cui, Chipchase and Ichikawa’s study reported missing phone calls due to how they were carrying their phones.

Patel et al. (2006) contribute with an additional explanation for why users miss notifications due to their devices’ placement. They have through empirical investigations examined people’s perception of how often they have their cell phones nearby. Their data show that people routinely overestimate their own proximity and availability to their cell phones, than what is accurate in reality. “The participant with the closest overall proximity level was within arm’s reach of his phone 85% of the time, despite his strong intuition that he carried the phone nearly 100% of the time” (ibid, p.137). Patel et al. further advice cell phone application designers to design context aware systems, which can take the dynamic proximity between user and device into consideration.

3.2 Studies on Cell Phone Conduct in Public Settings

An important study, regarding social implications due to cell phones, has been conducted in Norway by Richard Ling (1997). He examined how people made sense of the changes the cell phone brought into their social lives. He directed his study to find out where people placed the boundaries for appropriate versus inappropriate cell phone conduct in public settings, such as in restaurants. Even though his ethnographical data is now fifteen years old, and our relation and acceptance towards mobile devices has radically changed since 1997, the study still provides a fundamental understanding for why cell phones are considered intrusive in some public settings, while not in others. Ling explains how the cell phone’s ringing, the effect of loud talking and its ability to withdraw the user into an absent presence, stand in contrast to the norms and etiquette associated with eating at a restaurant. The study underlines both the unimagined possibilities and the complications new technology may bring, which causes us to reconsider our present social structures and behaviors.

Cross culture studies regarding the use of cell phones in public settings have been conducted by both Scott Campbell (2007), and Baron and Segerstad (2010). Campbell underlines that cell phones worldwide are considered in general more intrusive in settings where a common focus is required, such as in a movie theater or a lecture halls; and that norms for what is considered appropriate vs. inappropriate cell phone conduct within public settings are negotiated in similar ways all over the world (2007, pp.747-752). Baron and Segerstad (2010) compared Americans’, Japanese’s’ and Swedish students’ opinions regarding cell phone use in public settings. They found that students from Sweden were most tolerant to any form of cell phone use (phone calls and sending text messages were studied) in the public settings that were studied. Japanese students found it most inappropriate to use voice functions within public settings, while Americans only found it inappropriate when phones interrupted face to face interaction.

3.3 Studies, Products and Projects Regarding Subtle Outputs and

Informative Cues

The following section will present existing products, relating studies and projects that have been conducted in relation to the subjects of subtle outputs and informative cues.

3.3.1 The Reminder Bracelet

Hansson, Ljungstrand and Redström (2000, 2001) are in their project concerned with how mobile devices convey their notifications within social settings. They have observed that auditory notifications are too intrusive and attention demanding; while tactile ones – as vibrations- are too subtle and private. They underline how hard it is for people nearby to perceive the subtle notifications, and how that in turn makes it merely impossible for them to relate to the actions of the person who receives the subtle notification. The designers therefore try to find a middle way between subtle versus intrusive, and private versus public notifications. They describe in their study how a traditional wrist-watch is “public”; in the extent that it is often worn visibly as an aesthetically pleasing object and that people nearby instantly understand the symbolic meaning of a glance at it. Inspired by the watch, the designers created The Reminder Bracelet, which is a notification bracelet that can be connected to a phone. As new information arrives to the phone, embedded LEDs within the bracelet will start to twinkle; giving a subtle notification and a reminder for the wearer to check the phone when possible.

3.3.2 Live View

A phone accessory gives the user the possibility to stay informed of incoming information in a subtle manner, while having the main device hidden or detached from the body, for example, when stored in a bag. There are now a wide variety of notification accessories out in the market. I had for this project the opportunity to get hold of a Sony Live View, which is a wristwatch-sized display that mirrors the events that happens within the phone. It can be clipped on to any piece of clothing, with the intention to be close to the user’s

body; since its main notification modality is an intense tactile vibration. The Live View does not only extend the main device’s notifications, but it also lets the user check the notified content. A text message can directly be read from the accessory, and users can also get a decent overview of who is calling. Despite all this, users cannot act on the information through the accessory, meaning that they still have to fetch the main device to answer calls and text messages. Another concern has been the accessory’s aesthetics; which on one hand can be seen as clean and androgyne, while on the other, may contrasts with the notion of how accessories are objects of display and personalization, as it leaves no room for users to show their individuality.

3.3.3 Shoogle

In their prototype Shoogle, Williamson, Roderick and Hughes (2007) play with the notion of how

notifications usually work. Instead of letting the device have full control over when to inform the user, the designers have turned the interaction around. In Shoogle, the device simply becomes a container for the incoming information, whereas the user is the one who excites it, instead of being notified about it. In turn, the user has to constantly “check” their device, but in an easy and intuitive way. By walking and by more or less unintentionally moving the device, the digital information will be felt and heard bouncing around within the container; as if it had a physical form. Its form depends on what type of information it resembles. A short text message will for instance take the form of a little metallic ball. As the amount of text messages in the device increases, the feeling of multiple metallic balls bouncing around, clunking against the sides of the container will be transferred as an output. The user will after a while learn to recognize and to differentiate between the incoming information, without having to pick the device up from the pocket. Shoogle is interesting as it both places the user in control of the incoming information, as well as it exemplifies how subtle notifications can be highly informative for the user.

3.3.4 Feel Me

Marco Triverio (2011) has designed a text messaging application which allows people to explicitly feel each other’s presence at a distance. When two people are texting each other, Feel Me opens a real-time interactive channel. They can then see each other’s touch inputs. Touches from one side are shown on the other’s screen as small dots. Touching the same spot will trigger a small reaction, such as a vibration or a sound, to acknowledge that both parties are there at the same time. The interaction creates a playful connectivity, which borders the distance between the parties. Feel Me should not be seen as a solution for intrusive notifications. I have included it here to exemplify the importance of human to human communication through a mediating device, but where the device is withdrawn into the background to emphasize the meaningful interaction between humans.

As underlined by the theoretical framework and the social studies; meaning arises through users’ situated actions in their everyday settings. To be able to obtain an understanding of how the design solution may be appropriated by the user, it is crucial to center the design process around the user and the settings where situated actions occur. The design process was therefore based on a user-centered design approach, where users’ own insights, needs and desires were considered as a way to form the design space during the process. User-centered design (UCD) is often used as a broad term to describe design processes in which end-users are actively involved, or in other ways have a possibility to influence how the design takes shape. The term originated from Donald Norman, who in his publications, in the late 1980’s, highlighted how an understanding of users and their needs could contribute to enhance products’ usability. His emphasis on how designers should explore the users’ needs and desires, and further their intended use of the products, evolved within the field of UCD to further engage actual users in the design process; often in the environment where they naturally would use the product. Users’ involvement in the design process allows designers to obtain direct insights of what users require and desire from the product. This approach assures that the end-product is suitable for its purpose and works according to the users’ requirements (Abras, Maloney-Krichmar and Preece, 2004).

There are, however, some issues with this approach. Since the product is shaped according to the certain group of users that are involved in the design process, it is likely that the design solution only is specified for their needs, and hence not as applicable for a more general use. This became a concern during this thesis project, since the framed design problem affected a broad target group; inevitable any Swede owning a cell phone could have been the potential end user. To select representatives for this large target group would increase the risk of designing something for all, but which only would work for a few. I therefore chose to keep the target group open in the beginning of the process, to further see how the research would direct the design towards a certain user group.

The notion of “the user” also had to be re-evaluated, as I early realized that there was not just one primary user to consider, but as Eason (1987) has identified; there are as well secondary and tertiary users that additionally become affected by the use situation. As these different user types evaluate the situation in different ways, all of their insights and perspectives had to be considered and weighed against each other. This consideration became complex, as the user types constantly shifted. A phone user could in one moment be the primary user, to in the next be a tertiary user; affected by someone else’s phone. This in turn, required me to have a holistic view of what I considered to be a user, and whom to center within the design space. By using elements of participatory design, different user types could contribute their perspectives into the design space, which also made me consider how their contributions could affect each other.

The main point of participatory design is for users to become directly involved with the design process, where they become empowered as co-designers. The approach emerged as a political strategy in Scandinavia in the 1970’s, where researchers who focused on system development, often in collaboration with trade unions, pushed for workers to have more democratic control in their work environment. Since then, the approach has developed a stronger theoretical grounding, as well as tools and techniques for the practical work within the approach. Many of these tools and techniques are used together with the participants to establish a common platform for communication. Since participants, within the design process, may have different social and cultural backgrounds, the sharing of meaning and thoughts in a universal language is crucial for everyone to have the chance to be involved (Ehn, 1988; Löwgren and Stolterman, 2004, pp.151 -152). With this in mind, I tried to use basic and simple materials during my participatory workshop sessions, allowing anyone to

4 The Design Process and Methods Used

participate without any need of pre-establish skills or knowledge. It was important that the material became the common foundation where participants’ thoughts and discussions could derive and be shared on equal terms.

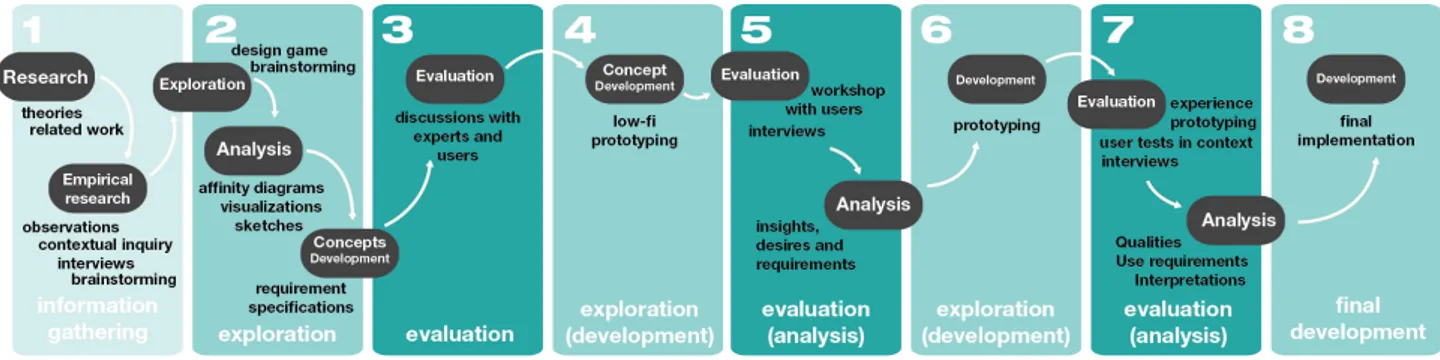

User-centered design and participatory design do not only stress the importance of involving the user within the design process, but they also provide essential methods and techniques for how to gather information, do design explorations and how to evaluate the design together with users. The process was therefore constructed into these three phases: information gathering, design exploration and evaluation. Where the two last mentioned, exploration and evaluation, were repeated after each other to form an iterative process. Each phase had their methods and design tools for how to gather and validate user inputs that could contribute to a framing or a further re-framing of the design space.

The design process began by gathering as much information about the research issue as possible (Figure 4). This was done by a familiarization with previous projects and research contributions within the field, but also through a UCD perspective; which suggested qualitative research. Instead of focusing on one theory of truth, qualitative research has a direct interest in the user’s subjective meaning, perspectives and understanding of the events occurring, and how they further can be modified by user’s intention and involvement. What may be considered to be true is therefore highly subjective and dynamic. Qualitative research can be done through an ethnographic approach, which methods study the user’s activity from inside their everyday setting.

From the range of ethnographical methods, I used naturalistic observation within public places, to obtain a general understanding of the occurring activities without interfering with it. Users’ activities were further studied through contextual inquiry, which is a research method that originated from the contextual design approach within HCI in the late 80’s. It aims to give the designer a broader understanding of the users, the everyday setting and any correlating factors that may affect the implementation of a future design solution (Löwgren and Stolterman, 2004, p.66). I used this method to observe participant’s activities by following them in their everyday settings. In contrast to the naturalistic observation, I was allowed to interfere and therefore conducted interviews and held brainstormed sessions together with the participators. Brainstorming was further used in a more explorative phase, where a design game was used to simulate situations that otherwise would have been too extensive to study through contextual inquiries. The participants were during the game assigned to discuss the simulated situations and to generate solutions for problems which were stated during the game play.

Both the research and the explorative phase generated a large amount of valuable data. To obtain an overview of the findings, anthropologist Kawakita Jiro’s KJ method, also called affinity diagrams, was used. This method helps to structure large amounts of data by pointing out their relating factors. The data can further be organized into meaningful groups, which often provide a more comprehensive overview of the overall material. Affinity diagrams were created with the intention to explore new perspectives and to see recurrent relations within the findings. The data was finally analyzed and grouped into thirteen categories, which were further used as requirement specifications in the conceptual phase. Concepts were created from the

specifications that were most relevant for the thesis at the time. These concepts were then evaluated through discussions with both users and interaction design experts. Their verdict and inputs re-framed the design space, where the final concept further took form.

An iterative process then began with user testing, evaluations and implementations of new ideas and insights that had sprung out from the previous user testing. I chose to extend the traditional user testing and evaluation methods that UCD provide; as I found them to be too usability and efficiency oriented. Instead, experience prototyping within the participants’ own setting gave users the ability to evaluate the prototype from their criteria. This prototyping technique is according to Marion Buchenau and Jane Fulton Suri a valuable strategy for designers to obtain an understanding of existing user experiences. It is a valuable exploration and evaluation of the design idea and simultaneously a good way to communicate it to the chosen target group (2000, p.425). I also held a workshop, where users were assigned to co-create prototypes which were intended to be used in further evaluations.

Most of the tools and techniques used within the exploration and the evaluation phases were hands on prototypes or open materials; free for the participants to explore and to interpret with their own meanings. The use of hands on material and prototypes required the users to be fully engaged in their experience, and to openly share what they were doing and thinking. Only then could reflection on actions generate valuable insights and ideas, which would re-frame the design space which could evolve the concept. The process was hence influenced by what Donald Schön (1983) defines as “reflection-in-action”; a type of situated learning where new knowledge is gained through conscious evaluations of the actions and situations taking place (1983, pp.50-68). These self-reflective insights constantly framed and re-framed the sensitive design space (especially broadly in the beginning of the process) to take new directions and considerations. This explorative, reflective and iterative process continued until the framing was found solid and few new insights were found as groundbreaking improvements for the concept.

5 Empirical Research

To obtain a fundamental understanding of how cell phone’s notifications affect public settings, field studies were conducted in a variety of public places in three cities in south Sweden: Malmö, Lund, and Kristianstad. Phone users and their abilities to adjust their phones, according to the public settings’ norms, were studied through fly on the wall observations and contextual inquiries. Brainstorming sessions and interviews with participants were conducted as gathering methods, to obtain both insights and desires from users.

5.1 Observing Cell Phone Notifications in Public Settings

The aim of the observational study was to get an overall impression of how people used cell phones within different public and social settings. I wanted to see notifications in action; through the observations witness how they captured the user’s attention, and additionally see if the surrounding setting became affected as well. In relation to observing the cell phone’s intrusive behavior, I found it interesting to find the reasons behind public settings’ normative expectations, of how cell phones are expected to behave. I wanted to observe how these expectations influenced users to adjust their cell phones accordingly, or where they did not matter. I was also interested in where the users placed their devices, in terms of access, security and the ability of noticing notifications.

The observations took place in a variety of public settings, such as in: restaurants, libraries, movie theaters, cafes, bus rides, shopping malls, a train’s quiet area, and in streets and squares. All settings allowed me to observe users and their cell phone practices from a distance. By using a non-intrusive naturalistic observation technique called fly on the wall, I was able to silently be part of the setting and unobtrusively focus my gaze on certain practices of interest. This technique is derived from ethnography, where it allows researchers to blend in with the natural activities taking place without interfering with the setting. The technique lets them access the same first-hand experience of places, people and events as the subject of interest. I found the technique to be an important practice for studying unfamiliar territory, and therefore valuable in the beginning of the project when the framing of the design problem still was broad. I documented my observations by taking notes, photographs and by shooting short video clips of occurring events. Most observations were done during day time, when the public places were crowded; apart from the restaurant and the theater observations, which were more accurately conducted during evenings.

To find cell phone users to observe was not hard in Malmö, where I began my observations. I was at first rather overwhelmed, when I realized through my fresh research perspective the density of devices used simultaneously in the streets. Even though the observations occurred during the blistering cold winter; talkers, texters, carriers and device exhibitionists were a recurring sight within the open urban landscape. People were driving, cycling, walking with baby trolleys while simultaneously being immersed by their devices. People’s dedications to their cell phones seemed infinite, especially amongst the majority of users who owned smart phones. These phone users seemed more eager than others, to repeatedly check their devices and to use them during longer intervals. It appeared as if the degree of people’s immersions stood in direct relation to their devices’ ability of providing them with valuable functions.

People also used their cell phones sporadically; often as time killer devices, as a relief to not feel bored during travels or shorter movements. I often saw people who picked up their cell phones as an excuse to not look idle or strange while waiting in public. In many cases the immersion with the cell phone was a deliberated way for users to exclude themselves from the public setting, and as an excuse to not be interfered by unknown others. People who talked on their phones naturally excluded themselves from the co-present by walking away from crowds, or by turning their back to others as a way to secure their privacy. Others signaled their unreachability by avoiding eye-contact with the co-present, by literally staring into the pavement while they were talking on the phone. As I walked around in the urban landscape I found these temporal private spheres fascinating to