Data privacy has been growing in importance in recent years, especially with the constant increase of online activity. Consequently, researchers study, design, and develop solutions aimed at enhancing users’ data privacy. The wicked problem of data privacy is a dynamic challenge that defies straightforward solutions. Since there are many factors involved in data privacy, such as technological, legal, and human aspects, we can only aim at mitigating rather than solving this wicked problem.

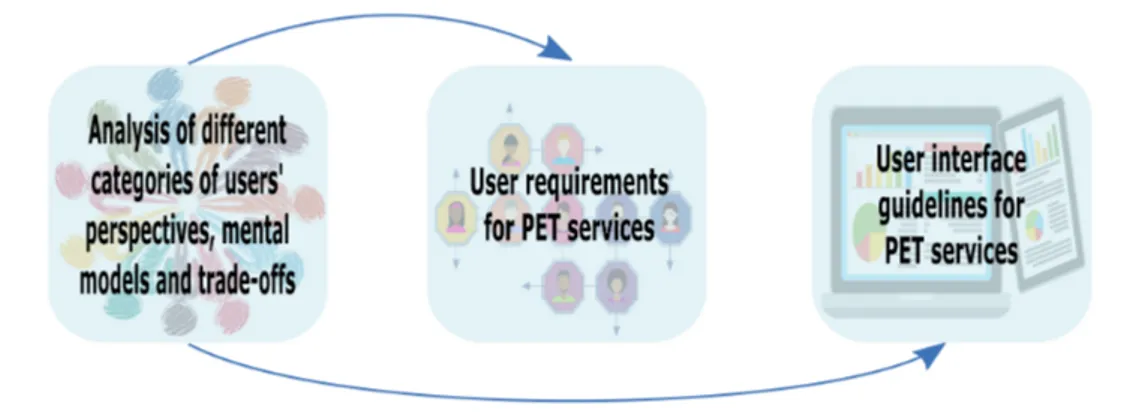

Our aim was to explore challenges and opportunities with a focus on human aspects for designing usable crypto-based privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs). Our results and tinkering conveyed (i) analysis of different categories of user’s perspectives, mental models, and trade-offs, (ii) user requirements for PET services, and (iii) user interface design guidelines for PET services. In our contributions, we highlight considerations and guidelines for supporting the design of future solutions.

Print & layout

University Printing Office, Karlstad 2019

T

inkering

The

W

icked

P

roblem

of

P

rivacy

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy

Tinkering the

Wicked Problem of Privac

y l

Ala Sarah

Alaqra

List of papers

I. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Thomas Groß, Thomas Lorünser, Daniel Slamanig. Signatures for Privacy, Trust and Accountability in the Cloud: Applications and Requirements. In: IFIP Summer School on Privacy and Identity Management. Time for a Revolution?, pp. 79-96, Springer International Publishing, 2016.

II. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, John-Sören Pettersson, Erik Wästlund. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Malleable Signatures in a Cloudbased eHealth Scenario. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security & Assurance (HAISA), pp. 220-230, 2016.

III. Thomas Länger,Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Erik Framner, John Sören Pettersson, Katrin Riemer. HCI Patterns for Cryptographically Equipped Cloud Services. In: HCI International 2018 (20th International conference on Human Computer Interaction), Springer International Publishing, August 2018.

IV. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Erik Framner. Enhancing Privacy Controls for Patients via a Selective Authentic Electronic Health Record Exchange Service: Perspectives by Medical Professionals and Patients. In Journal of Medical Internet Research 20, no. 12, December 2018.

V. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Erik Wästlund. Reciprocities or Incentives? Understanding Privacy Intrusion Perspectives and Sharing Behaviors. HCI International 2019 (21st International conference on Human Computer Interaction), Springer International Publishing, July 2019.

VI. Erik Framner, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Thomas Lorünser, Ala Sarah Alaqra, John Sören Pettersson. Making Secret Sharing based Cloud Storage Usable. In: Information & Computer Security (2019). Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 647-667.

VII. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Bridget Kane, Simone Fischer-Hübner. Analysis on Encrypted Medical Data In The Cloud, Should We Be Worried?: A Qualitative Study of Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Under Submission.

DOCTORAL THESIS | Karlstad University Studies | 2020:5 ISBN 978-91-7867-077-2 (print) | ISBN 978-91-7867-087-1 (pdf)

Design Challenges and Opportunities for Crypto-based Services

Ala Sarah Alaqra

Tinkering the Wicked

Problem of Privacy

Design Challenges and Opportunities for Crypto-based Services

Ala Sarah Alaqra

2020:5

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy

Data privacy has been growing in importance in recent years, especially with the constant increase of online activity. Consequently, researchers study, design, and develop solutions aimed at enhancing users’ data privacy. The wicked problem of data privacy is a dynamic challenge that defies straightforward solutions. Since there are many factors involved in data privacy, such as technological, legal, and human aspects, we can only aim at mitigating rather than solving this wicked problem.

Our aim was to explore challenges and opportunities with a focus on human aspects for designing usable crypto-based privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs). Our results and tinkering conveyed (i) analysis of different categories of user’s perspectives, mental models, and trade-offs, (ii) user requirements for PET services, and (iii) user interface design guidelines for PET services. In our contributions, we highlight considerations and guidelines for supporting the design of future solutions.

DOCTORAL THESIS | Karlstad University Studies | 2020:5 Faculty of Health, Science and Technology

Computer Science DOCTORAL THESIS | Karlstad University Studies | 2020:5

ISSN 1403-8099

ISBN 978-91-7867-087-1 (pdf) ISBN 978-91-7867-077-2 (print)

DOCTORAL THESIS | Karlstad University Studies | 2020:5

Tinkering the Wicked

Problem of Privacy

Design Challenges and Opportunities for

Crypto-based Services

Print: Universitetstryckeriet, Karlstad 2020 Distribution:

Karlstad University

Faculty of Health, Science and Technology

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science SE-651 88 Karlstad, Sweden

+46 54 700 10 00

© The author

ISSN 1403-8099

urn:nbn:se:kau:diva-75992

Karlstad University Studies | 2020:5 DOCTORAL THESIS

Ala Sarah Alaqra

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy - Design Challenges and Opportunities for Crypto-based Services

WWW.KAU.SE

ISBN 978-91-7867-087-1 (pdf) ISBN 978-91-7867-077-2 (print)

To my companion, poké, for being my nemesis and adding bottomless umami to my existence.

To mom and dad, for their infectious strength and unconventionality, as well as for nourishing my pursuits no matter how incomprehensible. To my sister Amy, for always believing in me, and to my other siblings for

increasing my XP through our combats.

To grandpa, for always encouraging my pursuit of science.

And finally, to all the games i played, for expanding my reality beyond this mediocre world; though the cake is a lie, the journey is enjoyable.

v

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy

Design Challenges and Opportunities for Crypto-based Services

Ala Sarah Alaqra

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Karlstad University

Abstract

Data privacy has been growing in importance in recent years, especially with the constant increase of online activity. Consequently, researchers study, de-sign, and develop solutions aimed at enhancing users’ data privacy. The wicked problem of data privacy is a dynamic challenge that defies straightforward so-lutions. Since there are many factors involved in data privacy, such as techno-logical, legal, and human aspects, we can only aim at mitigating rather than solving this wicked problem.

Our aim was to explore challenges and opportunities with a focus on hu-man aspects for designing usable crypto-based privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs). Mainly, there were three PETs in the cloud context included in our studies: malleable signatures, secret sharing, and homomorphic encryption. Based on the three PETs, services were developed within European research projects that were the scope of our user studies. We followed a user-centered design approach by using empirical qualitative and quantitative means for col-lecting study data. Our results and tinkering conveyed (i) analysis of different categories of user’s perspectives, mental models, and trade-offs, (ii) user re-quirements for PET services, and (iii) user interface design guidelines for PET services. In our contributions, we highlight considerations and guidelines for supporting the design of future solutions.

Keywords: Data privacy, wicked problems, user-centered design, privacy enhancing technologies, human factors, malleable signatures, secret sharing, homomorphic encryption

vii

Acknowledgments

The game is not over, however this quest is competed. My gratitude goes to those who influenced my adventure, directly as well as indirectly, on cogni-tive, practical, and inspirational levels. All discussions, collaborations, and encounters have definitely left a great impact on my development and becom-ing processes, thank you all!

I would like to express my appreciation to Simone Fischer-Hübner and Erik Wästlund, for their generous support, timely guidance, fruitful collabo-ration, and sincere advisory. I extend my thanks to my collaborators: Erik Framner, Bridget Kane, Thomas Länger, John Sören Pettersson, and my co-authors who also participated in the work of this thesis and had diverse con-tributions. Acknowledgment goes to the European research projects, Pris-macloudand Papaya, for partially funding the works in this thesis alongside Karlstad university. I would also like to acknowledge those who contributed to the knowledge body in our user-studies.

A glimpse from before I started my PhD journey, I would like to show my gratitude Lars Erik Janlert and Anna Croon Fors for inspiring me to pursue thinking and becoming.

Special thanks goes to my colleagues, Aga, Arty, Jenni, Leo M., Rasmus, and Tobias P., for discussions, friendship, and the generous support especially the past weeks of my thesis writing. Thank you Rickard for the help with printing, and Ida for the layout design.

Finally, as words are failing me, I cannot begin to describe how grateful I am for having the endless support and unconditional love of my family. Mom, dad, you have always inspired, mentored, had faith in, and provided me with everything that anyone can dream of, and to you I owe all my achievements— I love you. Andreas, you have been my anchor and partner in my quantum existence, i cannot thank you enough for riding this roller coaster with me— bubben aishiteru!!

ix

List of Appended Papers

This thesis is based on the work presented in the following papers:

I. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Thomas Groß, Thomas Lorünser, Daniel Slamanig. Signatures for Privacy, Trust and Account-ability in the Cloud: Applications and Requirements. In: IFIP Summer School on Privacy and Identity Management. Time for a Revolution?, pp. 79-96, Springer International Publishing, 2016.

II. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, John-Sören Pettersson, Erik Wästlund. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Malleable Signatures in a Cloud-based eHealth Scenario. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security & Assurance (HAISA), pp. 220-230, 2016.

III. Thomas Länger, Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Erik Fram-ner, John Sören Pettersson, Katrin Riemer. HCI Patterns for Crypto-graphically Equipped Cloud Services. In: HCI International 2018 (20th International conference on Human Computer Interaction), Springer International Publishing, August 2018.

IV. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Erik Framner. Enhanc-ing Privacy Controls for Patients via a Selective Authentic Electronic Health Record Exchange Service: Perspectives by Medical Profession-als and Patients. In Journal of Medical Internet Research 20, no. 12, December 2018.

V. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Erik Wästlund. Reciprocities or Incentives? Under-standing Privacy Intrusion Perspectives and Sharing Behaviors. HCI In-ternational 2019 (21st InIn-ternational conference on Human Computer Interaction), Springer International Publishing, July 2019.

VI. Erik Framner, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Thomas Lorünser, Ala Sarah Alaqra, John Sören Pettersson. Making Secret Sharing based Cloud Storage Usable. In: Information & Computer Security (2019). Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 647-667.

VII. Ala Sarah Alaqra, Bridget Kane, Simone Fischer-Hübner. Analysis on Encrypted Medical Data In The Cloud, Should We Be Worried?: A Qualitative Study of Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Under Submission. The papers have been subjected to minor editorial changes.

x

Comments on my Participation

Paper I I have designed and led the moderating and conducting of the inter-active workshop study (part 1). Co-authors were responsible for the tutorial part of the workshop (part 2), helped in part 1 of the workshop session, and in summarizing results.

Paper II I was the main responsible for the paper. I have designed, led the conducting of studies, analyses results and participated in the requirements elicitation. Co-authors and I have conducted interviews, moderated the work-shop, contributed to the discussions,and analysis of the requirements.

Paper III I was the main responsible for the paper’s work, have led the ducting of the studies, and evaluations of results. Co-authors helped in con-ducting the studies, writing, and reviewing the paper.

Paper IV I have been involved throughout the paper’s work. Thomas Länger was the main responsible for the paper. I took part in the paper’s contribution (patterns) analysis, was responsible for 2/3 of the patterns evaluation studies, and writing.

Paper V I was the main responsible for the paper’s work and have led the conducting of the studies. My co-author and I have worked on evaluating the studies, writing, and reviewing the paper.

Paper VI I have been involved throughout the paper’s user studies. Erik Framner was the main responsible for the study. I took part in the study design, iteration workshops, mock-ups design, paper writing, and reviewing. Paper VII I was the main responsible for the paper’s work, have led the study’s design, and evaluations of results. My co-authors and I conducted the studies, collaborated in writing, and reviewed the paper.

xi

Other Publications

• Alaqra, Ala Sarah. The Wicked Problem of Privacy: Design Challenge for Crypto-based Solutions. Licentiate Thesis. Karlstads universitet, 2018.

• Alessandra Bagnato, Paulo Silva, Ala Sarah Alaqra and Orhan Ermis. Workshop on Privacy Challenges in Public and Private Organizations. To appear in: IFIP Summer School on Privacy and Identity Manage-ment. Data for Better Living: AI and Privacy, Springer International Publishing, 2020.

The work in this thesis has been part of the following European research project deliverables :

• Ala Sarah Alaqra, Simone Fischer-Hübner, John Sören Pettersson, Frank van Gelllerken, Erik Wästlund, Melanie Volkamer, Thomas Länger, Henrich C. Pöhls.Prismacloud D2.1 Legal, Social, and HCI Requirements. Public report. May 2016.

• Simone Fischer-Hübner, Ala Sarah Alaqra, Erik Framner, John Sören Pettersson, Eva María Muñoz Navarro, Alberto Zambrano, Marco De-candia Brocca, Mosconi Marco, Thomas Länger, Katrin Riemer. Pris-macloudD3.2 HCI Guidelines. CO report. October 2017.

• Simone Fischer-Hübner, Ala Sarah Alaqra, Erik Framner, John Sören Pettersson, Thomas Länger, Katrin Riemer. Prismacloud D3.3 HCI Research Report. July 2018.

• Simone Fischer-Hübner, Boris Rozenberg, Ala Sarah Alaqra, Bridget Kane, John Sören Pettersson, Tobias Pulls, Leonardo Iwaya, Lothar Fritsch, Ron Shmelkin, Angel Palomares Perez, Nuria Ituarte Aranda, Juan Carlos Perez Baun, Marco Mosconi, Elenora Ciceri, Stefano Gal-liani, Stephane Guilloteau, Melek Önen. Papaya D2.2 Requirements Specifications. Public report. April 2019.

xiii

Contents

List of Appended Papers ix

Introductory Summary

1

1 Introduction 3

2 Background 4

2.1 HCI and Design . . . 4

2.2 Privacy and Data . . . 4

2.3 Wicked Privacy Design . . . 5

2.4 Mental Models and Acceptance of Technology . . . 6

2.5 Context of Thesis Work . . . 7

3 Research Question 8 4 Research Methods 9 4.1 Approaches . . . 9

4.2 Measures for Studies Support . . . 10

4.3 Interviews . . . 11

4.4 Focus Groups . . . 11

4.5 Survey . . . 11

4.6 Cognitive Walkthroughs . . . 12

5 Contributions 12 6 Summary of Appended Papers 14 7 Conclusions 18

Paper

I:

Signatures for Privacy, Trust and Accountability in the

Cloud: Applications and Requirements

23

1 Introduction 25 2 Cryptographic Tools 27 3 Use-Case Scenarios 30 4 Day 1- Focus Groups Discussions 31 4.1 Workshop Format . . . 31xiv

5 Day 2- Deep Dive on Cryptography: Graph Signatures and

Topol-ogy Certification 40

6 Conclusions 41

Paper

II:

Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Malleable Signatures in a

Cloud-based eHealth Scenario

45

1 Introduction 47

2 Malleable Signatures in eHealth Scenario 48 3 User Studies Methodologies 49

3.1 Semi-structured Interviews . . . 49

3.2 Focus Groups (Workshop) . . . 50

4 Results and Discussions 51 4.1 General Requirements for the Hospital Platform . . . 52

4.2 General Requirements for the Cloud Portal . . . 53

4.3 Requirements for Malleable Signatures Creation . . . 53

4.4 Requirements for Redactions of Signed Documents . . . 54

4.5 Requirements for Accessing Redacted Documents . . . 55

5 Conclusions 56

Paper

III:

HCI Patterns for Cryptographically Equipped Cloud

Ser-vices

59

1 Use of Cryptography in the Cloud 62 1.1 Current Security and Privacy Situation . . . 621.2 Suitable Cryptographic Primitives and Protocols . . . 62

1.3 HCI Patterns as Promoter of Cryptography Diffusion . . . . 63

2 HCI Patterns as Integral Part of a Cloud Service Development Methodology 64 2.1 The Prismacloud CryptSDLC Method . . . 64

2.2 Experts Involved in the CryptSDLC . . . 65

2.3 Role of HCI Patterns . . . 65

2.4 HCI Patterns Methodology . . . 66

3 Example HCI Patterns for Cryptographic Applications in the Cloud 67 3.1 Prismacloud Use-cases . . . 67

3.2 HCI.P1 Digital Signature Visualisation . . . 68

xv

3.4 HCI.P3 Secret Sharing Configuration Preferences . . . 75

4 Assessment and Lessons-Learned of Practical Application 79

Paper

IV:

Enhancing Privacy Controls for Patients via a Selective

Authentic Electronic Health Record Exchange Service:

Per-spectives by Medical Professionals and Patients

83

1 Introduction 86 1.1 Background . . . 86 1.2 Objective . . . 89 2 Methods 89 2.1 Overview . . . 89 2.2 Recruitment . . . 902.3 Documentation and Analysis . . . 91

2.4 Ethical Review . . . 91

2.5 Individual Walk-throughs: Interviews . . . 91

2.6 Protocol: Interviews . . . 91

2.7 Group Walk-throughs: Focus Groups . . . 92

2.8 Protocol: Focus Groups . . . 92

3 Mock-ups User Interface Designs 93 3.1 Mock-Ups Interfaces: Hospital Platform for Medical Staff . . 94

3.2 Mock-Ups Interfaces Sequences: Cloud Portal for End Users . 98 4 Results 101 4.1 Individual Walk-throughs or Interviews: Medical Staff Perspec-tives on Signing a Redactable Electronic Health Record . . . 101

4.2 Group Walk-throughs or Focus Groups: Patient Perspectives on Redacting Their Electronic Health Record . . . 106

5 Discussion 110 5.1 Summary . . . 110

5.2 Comparison with Previous Work . . . 111

5.3 Comparison: Sweden and Germany . . . 112

5.4 Legal Rules and Compliance . . . 113

5.5 Limitations . . . 114

5.6 Conclusions . . . 114

Paper

V:

Reciprocities or Incentives? Understanding Privacy

Intru-sion Perspectives and Sharing Behaviors

125

xvi

1 Incentives: Motivating Behavior 127 2 Privacy: Breaking Boundaries 128 2.1 Scope . . . 129 2.2 Research Objectives . . . 129 3 Methodologies and Approaches 129 3.1 Study 1: Survey/Quiz . . . 130 3.2 Study 2: Focus Groups . . . 132 3.3 Ethical Considerations . . . 133 4 Findings and Discussions 133 4.1 Study 1: Survey/Quiz . . . 133 4.2 Study 2: Focus Groups . . . 137 4.3 Discussions . . . 140

5 Conclusions 142

Paper

VI:

Making Secret Sharing based Cloud Storage Usable

145

1 Introduction 147

2 Background 150

2.1 Secret Sharing Schemes for Archistar . . . 150 2.2 Legal Aspects . . . 151 2.3 Trade-offs Between Goals . . . 152

3 End User Studies 152

3.1 Interviews . . . 153 3.2 Design and Evaluation of Configuration User Interfaces . . . 159 4 HCI Guidelines And Discussion 162

5 Related Work 167

6 Conclusions 167

Paper

VII:

Analysis on Encrypted Medical Data In The Cloud, Should

We Be Worried?: A Qualitative Study of Stakeholders’

Per-spectives

171

1 Introduction 173

1.1 Analysis on Encrypted Data: Papaya Use-case . . . 174 1.2 Objective . . . 174

xvii

2 Background 175

2.1 Data Protection: eHealth . . . 175

2.2 Privacy, Security and Safety Trade-offs in eHealth . . . 176

3 Methods 176 3.1 Study Design . . . 176

3.2 Recruitment and Sampling . . . 177

3.3 Data Collection . . . 178

3.4 Data Analysis . . . 178

3.5 Ethics . . . 179

4 Results 179

5 User Requirements 181 6 Discussions and Related Work 183

Introductory Summary

“Technology is not neutral. We’re inside of what we

make, and it’s inside of us. We’re living in a world of

connections – and it matters which ones get made and

unmade.”

WIRED

— You Are Cyborg (1997)

Donna Haraway

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 3

1 Introduction

Constant advances in technological developments facilitate computer-driven information growth in the cyber age. We live in a time when data, generated by either machine or human, is growing at an exponential rate every two years [23]. Trends, such as the emergence of big data, utilize the large volume of data in developing applications. Big data is a field for processing massive amount of data, structured and unstructured, and addressing the complexities involved [28]. In conjunction with, various data uses and opportunities advance in cyber space using cloud services. Consequently, privacy and security threats to data proliferate, thus requiring proactive measures for data protection [15]. Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are means to protect data with a focus on tackling threats to individuals’ personal data, processing the minimal required amount of data, and for protecting and enhancing privacy [48]. Con-sidering end users, PETs may not adhere to their mental models and could be counter intuitive [53]. Therefore, a development challenge is to design for user’s adoption of PETs at hand [4].

We posit that privacy, specifically in the context of data privacy, is a wicked problem. In design, a wicked problem is a complex one that has no definite solution [10]. The wicked problem of privacy corresponds to the challenge of designing for usable PETs, while taking into consideration the trade-offs and dynamics of technological, legal, and human factors [6]. It refers to the chal-lenge of designing for usable privacy enhancing solutions, while taking into consideration the trade-offs and dynamics of technological, legal, and human factors.

In this thesis, we tinker with the wicked problem of privacy with a focus on human factors within two European research projects. PETs were being de-veloped using cryptographic schemes into services during our work with the projects. Our objective was to explore and identify human-factor-based chal-lenges and opportunities of the PETs and related privacy behaviors The goal is to shed a light on design guidelines and considerations for adaptable PETs. Our strategy for addressing the wicked privacy design challenge involves a col-laboration with different stakeholders as an approach to tackle wicked prob-lems [7]. In our empirical studies, we addressed different categories of users’ mental models, behaviors, and perspectives with their incentives, choices, and trade-offs of data privacy.

The remainder of this summary is structured as follows. Section 2 sets the stage for the thesis with corresponding background and related work. The research question is presented in Section 3. An overview of the approach and methods used are presented in Section 4. Contributions are presented in Section 5. Summaries of appended papers are found in Section 6. Finally, conclusions are presented in Section 7.

4 Introductory Summary

2 Background

In the following subsections, we will present the relevant background and partly related work corresponding to the thesis.

2.1 HCI and Design

The field study of Human Computer Interaction (HCI) is considered the most visible part of computer science [11]. HCI is a multidisciplinary area that fo-cuses on human factors and computer systems integration and interactions. Through observations, analysis, evaluation, and implementation, HCI aims to design systems for human use. Concepts like usability and user experience are shown to be important in designing functionality of systems for users [42]. On the one hand, usability involves meeting up with usability criteria: effec-tiveness, efficiency, safety, utility, learnability, and memorability [42]. While on the other hand, user experience focuses on qualities of the experience: satis-fying, enjoyable, fun, entertaining, helpful, motivating, aesthetically pleasing, supportive of creativity, rewarding, and emotionally fulfilling [42]. Design-ing for the two concepts usually involves trade-offs dependDesign-ing on the context of use, task, and untended users [11]. When dealing with human factors in-teracting with computer systems, it is essential to take both concepts into consideration in HCI design [42].

2.2 Privacy and Data

Whether it is personal space or private belongings, privacy is valued to a cer-tain extent subjectively from one person to the other [32]. What is privacy? The answer would differ based on the perspective. Privacy, as Warren and Brandeis define it is “the right to be let alone” [52]. That definition indi-cates the intrusive role of the exterior environment that could threaten one’s (un)conscious sense of own privacy. In a computer science perspective, in-trusion of privacy tend to be focused on users’ data. Ordinary users tend to overlook the consequences and implications of direct and indirect intrusions to their information. Intrusive applications and portals tend to threaten one’s data privacy implicitly as well as explicitly. Studies show how private informa-tion can be derived from digital records e.g., Facebook likes deriving personal attributes [27]. For instance inferred data (expecting a baby), which can be de-rived from apparently non-sensitive data (shopping list), is usually overlooked by many users, however acquiring that information can still in many cases be considered an intrusion [25].

Another definition of privacy by Westin is “the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others” [54]. Informa-tional self-determination directly relates to the privacy aspects of user control and selective disclosure that we are addressing in our studies.

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 5

2.3 Wicked Privacy Design

Wicked problems is a concept that refers to a complexity of a problem that deems it unsolvable, especially in design where indeterminacy of conditions and limitations are prominent [10]. In contrast, “tame” problems, like for example mathematical integrals, have a clear solution and are thus considered solvable [10, 17]. A great amount of research on data privacy, from technolog-ical, legal, and social perspectives as well, has been shown to take part in many disciplines [44]. For instance, Regan (1995) focused on three forms of privacy concerns: communicational, informational, and psychological. In addition, it was shown that technological advancements have an adverse influence on data privacy. It was stated that privacy as a collective social value is an important factor for addressing privacy concerns [40].

Technology that aims to enhance the privacy and security of tools and applications may follow the privacy by design principle [13]. Whereas laws regulating privacy and data protection focus on the legal perspective, such as the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in Europe [1] requires following data protection by design and privacy by default principles. Hu-man factors taken into consideration in early development stages follow pri-vacy by design and user-centered design approaches [3, 35]. Considering the above-mentioned factors involved in data privacy and their entanglements, it is credible to declare data privacy a wicked problem. We highlight three main aspects of this wicked privacy challenge in the following paragraphs: techno-logical, legal, and human. Keeping in mind the dynamic of time, which would require to update technologies, laws, and experiences.

2.3.1 Technological

Technological advancements in data privacy research deal with enhancing pri-vacy by developing improved solutions. Pripri-vacy Enhancing Technologies or PETs for short, aim to mitigate the privacy challenge by providing several means for users to adopt. Related work has given an account for the short-comings of privacy enhancing technology work [18]. Danezis and Grüses surveyed the field of privacy research of PETs and highlighted the complex-ities of privacy scope and definitions. They presented key technologies, and showed that privacy research is usually tackled within the boundaries of their narrow scope and definitions. They concluded that in order for privacy re-search to progress, we need to address the bigger picture [18]. This entails the wickedness of privacy, since the bigger the picture the greater the complexity when dealing with privacy solutions.

2.3.2 Legal

Not only the definition of privacy varies with context, so do the legal rules for what constitutes privacy in different systems. For instance, the European charter of the fundamental rights clearly defines privacy and data protection as human rights in articles 7 and 8 [2]. Whereas the US constitution does not

ex-6 Introductory Summary

plicitly mention the word privacy, but rather security against intrusions in the fourth amendment (search and seizure). Additionally, unlike the harmonized regulation of the GDPR in Europe, regulations in the US follow a sectoral approach, e.g., medical information are safeguarded by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [36] . Previous work has shown conflicts and contrast between U.S. and EU regulations in privacy policies, and specially implications of those on trade and transaction in globalization and digital age [33].

2.3.3 Human Behaviors and Experiences

The privacy paradox is a phenomenon where users indicate their concerns about privacy while their behaviors state otherwise [8, 46]. It is believed that this is partially because users are primarily seeing the immediate benefits of services while being unaware of the long-term consequences and implications of the digital interactions [46]. We can easily understand the financial impli-cations of sharing a credit card number, whereas on the other hand sharing a location online may seem harmless at the first glance. It has been argued, more recently, that the behavior in the privacy paradox is rather predictable, and that the culprit is in fact the designs of online platforms of which exploit users’ cognitive limitations; employing dark patterns in design and triggering cognitive biases [51]. Understanding dark patterns and psychological dark strategies is considered important in the approach for developing countermea-sures to benefit users [9].

Users behavior is not irrational, constraints to users abilities in privacy decision-making is thought to be attributed to fatigue of security and pri-vacy [16, 45]. When users are overwhelmed by the constant need to be alert and adopt new measures to prevent security risks, they are left tired, depleted, and eventually resigning and losing control; security fatigue [45]. Similarly, the dimensions of privacy fatigue includes the emotional exhaustion and cyn-icism in online privacy behavior, which results in users putting less effort in protecting their privacy [16]. Entanglements of human behavior and subjec-tivity to perceive privacy are clear challenges for designing privacy services.

2.4 Mental Models and Acceptance of Technology

The significance of human factors is high for the adoption of technologies. It is especially the case with new crypto-based technologies, which face the additional challenge of not being familiar. Familiarity can be defined as:

“The degree to which a user recognizes user interface components and views their interaction as natural; the similarity of the inter-face to concrete objects the user has interacted with in the past. User interfaces can be familiar by mimicking the visual appear-ance of real-world objects, by relying on standardized commands, or by following other common metaphors.”1

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 7

The acceptance and adoption of technology is heavily reliant on the end user [50]. Previous studies have investigated the relationship between past encoun-ters (experiences) and acceptances of technologies [5, 24, 31, 47, 49, 55]. Men-tal models, specifically cognitive value of prior experience, are an important factor in the correlation between end-user adoption of technology and user ex-periences [55]. Meanwhile, trust is shown to be a value that is important for the intended behavior of users [24, 31]. Intrinsic and hedonic motivation were also considered as important factors for users acceptance of technology [49]. Therefore, one key approach for designing PETs is to understand user’s pri-vacy related mental models, values, and motivations for adopting PETs.

2.5 Context of Thesis Work

The work of this thesis took place within the scope of two research projects— described in Sections 2.5.1 and 2.5.2— funded by the European Union’s Hori-zon 2020 research and innovation program. The two projects define the cir-cumstances of our studies, why our investigation took place, and which pri-vacy enhancing mechanisms are used. The three used PETs are (i) Selective Authentic Exchange service (SAE), (ii) Archistar configuration management, and (iii) encrypted electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis. Detailed descriptions are below within their corresponding project.

2.5.1 Prismacloud

The first project is Prismacloud, which is short for PRIvacy and Security MAintaining services in the CLOUD [39]. Prismacloud developed cloud-based solutions, which use cryptographic schemes to enhance security and privacy. The project develops novel services from crypto schemes into use-cases within the project, which are in the areas of eHealth, eGovernment, and Smart city.

Selective Authentic Exchange service (SAE) The crypto-scheme addressed in the Selective Authentic Exchange Service—or SAE for short— is a data min-imization2technology called malleable (also known as redactable) signatures.

A malleable signature is a cryptographic scheme that allows specified redaction (removing or blacking out) of fields within a digitally signed document while maintaining the validity of the signature [14, 19]. One of the Prismacloud use-cases involves the implementation of the SAE service in eHealth, which al-lows patients to redact specified fields of documents that were digitally signed by their medical doctor. Using malleable signatures allows users to minimize the amount of information on their signed digital documents and thus enhanc-ing their data privacy. User-control is inferred by usenhanc-ing malleable signatures, as it enables users to first redact and then selectively disclose authentic data.

2Data minimization is a privacy principle that deals with limiting the collection and use of

8 Introductory Summary

Archistar configuration management Archistar is a system that deals with secure distributed data storage in the cloud [29]. In order to secure data storage across different storage clouds, Archistar uses a secret sharing scheme. Secret sharing allows the splitting of data into N secret chunks or shares to be dis-tributed among a number of cloud servers [26, 43]. A predefined amount K of secret shares is required for reconstructing data, where K is less or equal to N. Consequently, secret sharing may enhance the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the stored data. In Prismacloud, Archistar requires usable configurations for the distributed cloud storage system. Our user studies ad-dressed the configurations of the required numbers of N and K, privacy and security concerns, limitations, and trade-offs.

2.5.2 Papaya: encrypted electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis

The second project is Papaya and stands for PlAtform for PrivAcY preserving data Analytics [37]. Papaya develops technologies for privacy preserving data analytics using machine learning. One example is based on using homomor-phic encryption to protect analysis performed by untrusted third-parties. In general, homomorphic encryption enables processing on encrypted data, thus protects the data from unauthorized access and maintaining confidentiality. The development of privacy enhancing schemes and technologies in Papaya aims to ensure that the benefits, cost effectiveness and accuracy of data, are not compromised with the analysis on data that is in encrypted format. One of the use-cases of Papaya that is part of this thesis work is in the area of health-care informatics: encrypted electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis. The use-case description is that ECG data is to be collected by patient’s wearable devices and then transferred to a medical platform where it is encrypted and sent to be automatically analyzed in an untrusted cloud environment. Addressing stake-holders perspectives on possible trade-offs (data quality vs. privacy), concerns, and trust of such proposed solution was part of this thesis work.

3 Research Question

In our attempt to identify key blocks for tinkering the wicked problem of privacy, and to meet our research objective, we addressed the following general research question in our work. A recap to our research objective: to explore and identify human-factor-based challenges and opportunities of PETs (introduced in Section 2.5) and related privacy behaviors

How to design for human-focused crypto-based privacy enhancing technolo-gies?

The adoption of new technologies relies to a great extent on their users’ acceptance, as discussed in Section 2.4, therefore studying users and taking human factors into account is crucial. Understanding users’ intuitive per-ception and mental models is especially important when addressing the

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 9

acceptability of new PETs. In our studies, we addressed novel PETs in crypto-based services developed within two European research projects, and followed a human centered approach in all of our studies. Our ap-proach in designing is to focus on user’s involvement early in the develop-ment processes of crypto-based services. Their involvedevelop-ment includes their perspectives, opinions, concerns, needs, and requirements. For addressing the research question, we have included different categories of users and stakeholders in all of our studies. We explored acceptability and usability needs for adopting PETs. Apart from legal and technical considerations, our investigation also included user experience considerations such as mo-tivations and trust, in addition to possible privacy trade-offs.

4 Research Methods

Throughout studies included in this thesis, a human focused approach was followed in the exploration and investigation design of the studies.

4.1 Approaches

In HCI, various human aspects are taken into consideration, and approaches are adopted accordingly in the design process. Value Sensitive Design (VSD) involves the consideration of human values and morals aspects in particu-lar [22]. In our work, the focus has been on a the privacy value, and thus have been adopting the privacy by design principle [13]. Furthermore, in our projects we have followed a User-Centered Design (UCD) approach, since users are an important factor in the design process of usable technologies [3]. During the iterative cycles of development and design processes, UCD ap-proach allows exploration and detection of user related needs and concerns and adapting accordingly in the next cycle already [3, 35].

Our research has been mainly empirical, and our means for data collection and exploring the complexities of user’s perspectives included both qualitative (semi-structured interviews and focus groups) and quantitative methods (sur-vey), detailed in the following subsections.

In some of our studies, we have been adopting methodological triangula-tion. Triangulation is the use of a combination of methodologies in addressing the same question for validation purposes [30, 41]. The combination can be either within method (all e.g. qualitative), or mixed (qualitative and quantita-tive). We used a combination of two qualitative methods in our triangulation of Paper I, which allowed us to collect data that are more comprehensive and enhanced our understanding in the earlier stages of the project. Similarly in Paper IV, we used two methods corresponding to the study design of hav-ing two categories of users: interviews with doctors and focus groups with end-users. As for Paper V, we have used a mix of both quantitative (survey) and qualitative (focus groups) in our exploration and understanding of user’s perspectives.

10 Introductory Summary

4.2 Measures for Studies Support

Apart from the methods used, the following are means that we used for our tasks description throughout our data collection methodologies. They served as a facilitation to our conduction processes as well as a support of our com-munication with our study subjects.

• Use-cases: A use-case defines tasks, or envisioned tasks in early project stages, with a focus on functionality from users’ perspectives. Use-cases mainly describe the interactions and activities between users and the system [42]. It is commonly the task of software developers to define use-cases for the system usages. Use-cases of Prismacloud and Papaya were used in all papers. In Paper I, three use-cases were used in the areas of eHealth, eGovernment, and Smart city. In Paper III, eHealth and eGovernment uses-cases were used. The rest, apart from Paper VI, were focused on eHealth use-cases.

• Scenarios: A scenario is a description of tasks and activities that follow an informal and story-like format [11]. Scenarios are also considered one of the richest formats of design interaction representation and most flexible [20]. We have used scenarios in the descriptions of our use-cases in most of our user studies (all but Paper VI). Scenarios facilitate the understanding of our use-cases and discussions with our correspondents due to easy language and narrative format.

• Personas: Personas are fictional roles or characters designed with descrip-tive profiles in order to mimic a realistic situation [42]. We used user personas in the study of Paper IV and Paper V to facilitate our discussion and to avoid the exposure of our correspondents’ personal information: correspondents rather used the assigned personas in their tasks and dis-cussions.

• Metaphors: In design, metaphors are used to convey new meanings to users and help understand ideas using comparison. By mapping the fa-miliar to the unfafa-miliar, metaphors help in understanding the target domain and further address users’ mental models [12]. We have used metaphors throughout Papers II–V.

• Mock-ups: Mock-ups are low-fidelity prototypes that are designed in ear-lier stages of the development process, in order to capture user’s feed-back during evaluation. They aid in presenting functionality through visualization in the users’ interface [42]. We have designed mock-up user interfaces (UIs) presented in Paper IV as well as Paper VI.

• HCI Patterns Template: We used HCI patterns template to present our design solutions in our results. The template provided a framework for our patterns [21]. HCI patterns aid in communicating our solutions to designers and developers within the project as used in Paper III.

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 11

4.3 Interviews

Interviews are a form of inquiry for user data collection administrated by a researcher. Interviews can be unstructured (open-ended) , structured (closed), and semi-structures (flexible structure) [42]. Unstructured interviews follow informal dynamic form of conversation, where the interviewer and intervie-wee steer the discussion openly. This form of interviews is typically used when goals are not specified or clear at early stages of design.

Structured interviews are a form of surveying that involves the presence of the interviewer, and follow a structure with predefined questions of specific areas of inquiry. Though structured interviews are used for mostly statistical inference from a sample group, it is sometimes used for qualitative research to get specific feedback. In Paper VI, structured interviews were chosen follow-ing our objective, where specific areas of inquiry regardfollow-ing Archistar are to be investigated by all participants. We collected end users’ input for requirements elicitation and mock-ups design.

Semi-structured interviews are a form of inquiry that does not follow a strict structure, but rather allows deviations and flexibility. The facilitation of discussion openness is necessary for an in-depth understanding of the user’s perspectives [42]. We have used this form of inquiry in Papers II, IV, and VII. Semi structured interviews allow us to investigate user’s perceptions and opinions while customizing our inquiry during the interview. Though time-consuming, this form of interviews facilitates detailed discussions to under-stand correspondent’s responses. In the work presented in Papers II and VII, we used a set of predefined questions as a guide for the interviews. However, in Paper IV, the mock-ups interfaces were the framework for the interviews discussion themes.

4.4 Focus Groups

Similar to the interviews, the focus groups methodology allows us to inves-tigate participants’ perceptions, opinions, attitudes and concerns. However, the dynamic of the focus group gives an added layer of interaction, where participants can agree, contradict, and/or elaborate on others’ inputs [42]. We used focus groups’ interactivity and dynamics of discussions as a second approach to interviews for Paper II. As for Paper IV, the interaction among participants was essential for the study’s design; it included a segment where participants would be assigned a persona and respond to discussion questions about sharing among the focus group members. Furthermore, informality of the focus groups approach allowed the interactivity and varied discussions among different focus groups, e.g., participants with technical expertise were raising technical points to discuss with fellow technical participants.

4.5 Survey

Surveying is a qualitative method for the sampling and investigation of sub-jects’ opinions following a structured format. With a predefined research

cri-12 Introductory Summary

teria, questions in the survey are structured in a way that allows statistical inference of results based on the sample. Using surveys is appropriate when addressing a larger sample of users for a generalized phenomena. We have used a survey in Paper V for investigating the five evaluation criteria relative to the study’s objective. We collected data online from a relatively large sam-ple in order to investigate user’s experiences and behaviors regarding privacy incentives and boundaries.

4.6 Cognitive Walkthroughs

Cognitive walkthroughs are a method that inspects the elements of the user’s interface and identify usability issues [38, 42]. They are a task-specific tech-nique used to evaluate a small part of the system in detail. Evaluators are typically given a task or series of tasks to complete while interacting with the interface with a user’s perspective in mind. The number of steps and series of actions taken by the user, as well as meeting goals are considered towards assessing learnability of new users. [34]. In Paper VI, we used cognitive walk-throughs to evaluate our proposed mock-ups user interfaces for the manage-ment of Archistar. The mock-ups were for setting up and selecting parameters configurations. Our evaluation served as a mean to identify usability require-ments, restrictions, and trade-offs of the configuration settings.

5 Contributions

The work in this thesis has comprised of varied user-studies for human factors in designing PET services. Detailed below are the highlighted contributions which include (i) analyses of different categories of users’ perspectives, their mental models, and possible trade-offs, (ii) user requirements for PET services, and (iii) user interface design guidelines for PET services.

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 13

1. Analysis of different categories of user’s perspectives, mental models, and trade-offs

The first step in addressing the design challenge for PET services is to understand the user’s perspectives and mental models. In addition, we examined different categories of users, e.g., technical vs. lay, and took into account trade-offs in behavior, utility and risks. Our UCD ap-proach has led our investigation of perspectives and mental models of diverse categories of users for each crypto-based privacy service. In ex-ploratory research, it is important to include different categories of users to sample a wider variety of users. Challenges and concerns were high-lighted across our studies which led to considerations, requirements and means for support in our design process.

In the case of the selective authentic exchange service used in an eHealth use-case, based on malleable signatures, users with different technical background, roles in the services process (signing or redacting), and contextual influence (country-based comparison) were the factors con-sidered (Paper I, II, IV, and V). Outcomes included requirements de-pending on the factors addressed. Additionally, mental models of dif-ferent categories of users were highlighted, e.g., technical users require knowledge-appropriate support for trusting the tool and using it. Sim-ilarly in the case of Archistar, the distributed cloud storage system, we investigated technical users from different countries with varied tech-nical roles (Paper VI). Outcomes revealed necessary modification and considerations, e.g., configuration of the tool is challenging even for technically skilled users, and that organizational, legal, and technical skills are required jointly. Different stakeholders were in focus in the eHealth use-case in the analysis of encrypted medical data found in Pa-per VII.

We investigated the perspectives of stakeholders having technical, medi-cal, and research backgrounds. The results have highlighted varied trust concerns regarding the tool, e.g., concerns trusting the accuracy of the analysis depended on trusting the service, algorithm used, and/or lack-ing guarantees. Contributions to the understandlack-ing of user and HCI challenge have helped identifying key HCI considerations and concerns for eliciting usability, trust, and privacy requirements.

2. User requirements for PET services

We have been eliciting user requirements for every PET service in our user studies. The requirements enhancing usability, privacy, and trust for the selective authentic exchange service were elicited, analyzed, and refined through several iterations (Paper I, II, and IV). The first itera-tion (Paper I), requirements were elicited via focus group workshops. For the second iteration (Paper II) the requirements were refined by re-sults from semi-structured stakeholder interviews. Mock-ups addressing

14 Introductory Summary

those requirements were then designed and evaluated by walkthroughs used in interviews and focus groups. Consequently, the evaluations re-sulted in a 3rd iteration of requirements (Paper IV). In Paper VI, for the distributed cloud storage system, Archistar, privacy and legal re-quirements were discussed. In addition, organizational limitations and requirements were considered as we elicited end user requirements from the user studies for the UI. Finally, requirements for trust and inform-ing users, for the analysis on encrypted medical data service in Paper VII, were elicited from the semi-structured interviews.

3. User interface design guidelines for PET services

We present different means of supporting the user interface design of the PET services as follows:

• Mock-ups designs for the hospital platform and cloud portal of the electronic health record of the SAE service, which were tested and evaluated in iterations and could act as a guide template for future applications design (Paper IV).

• Mock-ups designs and guidelines for finding suitable trade-off con-figurations for the management of Archistar, the distributed cloud storage system. Mock-ups were evaluated and tested using cogni-tive walkthroughs and went through two iterations (Paper VI). • HCI patterns, which include metaphors addressing user’s mental

models (Paper III). These include HCI patterns for digital signa-ture visualization, the use of the stencil metaphor for the redaction process, and default configurations for Archistar.

6 Summary of Appended Papers

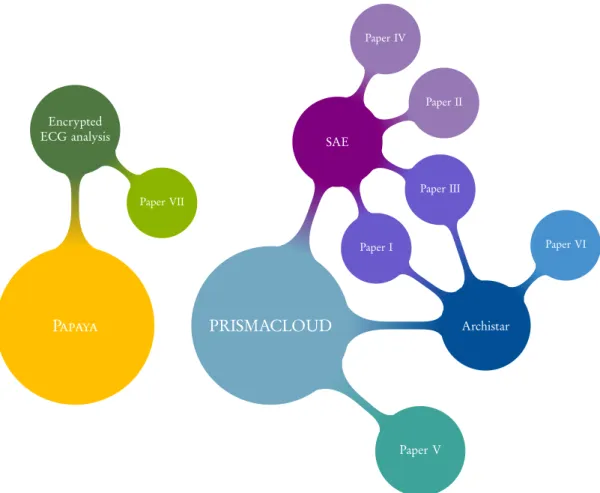

Following with the three main services based on PETs, as introduced in Sec-tions 2.5.1 and 2.5.2), the work of this thesis was involved around sharing and storage, protection and minimization, user control, and trade-offs with data in the cloud context. Figure 2 shows the relationship between research projects, PETs, and papers included in this thesis. The following subsections summarize the appended Papers I–VII.

Paper I – Signatures for Privacy, Trust and Accountability in the Cloud: Applications and Requirements

The work in this paper addresses earlier stages of the Prismacloud project. Results are based on the two days workshop held at the IFIP Summer School 2015. Participants were therefore participants of the conference. Cryp-tographic tools and use-case scenarios of Prismacloud were presented in the workshop. For the first day, an interactive part of the workshop took place. There were 25 participants forming five interdisciplinary parallel focus groups. They discussed use-case scenarios and explored HCI challenges for

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 15 PRISMACLOUD Paper V SAE Paper I Paper II Paper III Paper IV Archistar Paper VI Papaya Encrypted ECG analysis Paper VII

Figure 2: Overview of papers and PET services for the two research projects eliciting usability, trust, and privacy requirements. The second day featured a tutorial on graph signatures and topology certification, followed up by a tech-nical discussion on further possible applications. The paper summarizes the results of the two-day workshop with a highlight on applications scenarios and the elicited end-user requirements.

Paper II – Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Malleable Signatures in a Cloud-based eHealth Scenario

In this paper, the malleable signatures scheme in the eHealth use-case of Pris-macloud was in focus. We investigated stakeholders representing end-users in the earlier stages of our UCD approach. The objective was to gain an un-derstanding of user’s opinions and concerns regarding the use of malleable signatures. We therefore elicited requirements addressing usability aspects as well as social factors. Results from our qualitative studies, semi-structured in-terviews and focus groups, have yielded our end-user requirements presented and evaluated in this paper. Examples included suitable metaphors and guide-lines, usable templates, and clear redaction policies. Future work suggested decreasing the cognitive burden on users through technical and UI support, e.g., default privacy-friendly settings.

16 Introductory Summary

Paper III – HCI Patterns for Cryptographically Equipped Cloud Services This paper presents three HCI patterns for the two Prismacloud cloud based cryptographic PET services: Archistar configuration management and SAE service. The patterns address the challenge of how cryptographic solutions are counter-intuitive to users’ mental models. Tackling security and privacy risks cryptographic solutions in the cloud, HCI patterns provide means for com-municating guidelines and requirements to designers and developers. This ap-proach was used within Prismacloud development lifecycle of its two cloud-based PET services. Details of the categories, analysis, and evaluation of the following patterns were described in the paper. The first pattern HCI.P1 is digital signature visualization. A visual representation of signers’ handwrit-ten signatures on digital documents. This resemblance with signatures on paper visualization and location on the document acts as an intuitive means for using digital signatures. The second pattern, HCI.P2, is a stencil for digital document redaction. A metaphor of blacking-out/graying-out fields on the document in a process of redaction. This process encompasses the data-minimization principle of privacy protection. Finally, the third pattern HCI.P3, is secret sharing configuration preferences. It recommended default configurations settings based on the priority user selection of the three pref-erences: “Cost Minimization” , “Data Confidentiality Maximization – High Data Protection”, and “Data Availability Maximization – High Data Loss Pre-vention”.

Paper IV – Enhancing Privacy Controls for Patients via a Selective Au-thentic Electronic Health Record Exchange Service: Perspectives by Med-ical Professionals and Patients

In this paper, we focus on two different users’ perspectives, the medical pro-fessionals on the one side, and prospective patients on the other. The Selective Authentic EHR Exchange service is the PET service addressed in this paper’s studies in the eHealth scenario. Privacy is enhanced, through the data min-imisation principle, and authenticity is ensured in EHR using redactable sig-natures. We investigated the perspectives and opinions of our participants, in both Germany and Sweden, using the designed low fidelity mock-ups (pre-sented in the paper). For signer’s perspectives, we interviewed 13 medical pro-fessionals. As for the redactors’ perspectives, we conducted five focus groups of prospective patients (32 in total) with varying technical expertise. We psented and discussed the results from both perspectives, and refined our re-quirements and presented further ones for future implementations.

Paper V – Reciprocities or Incentives? Understanding Privacy Intrusion Perspectives and Sharing Behaviors

In this paper, two studies show the investigation of user’s sharing behaviors, perspectives of their data privacy incentives, and influences to their willingness to share their personal information (reciprocities and trade-offs). Following

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 17

an exploratory User-centered Design approach (UCD), data was collected us-ing quantitative (survey) and qualitative means (focus groups). The survey took place online with 165 valid and complete responses, whereas the five fo-cus groups varied in location (Sweden, Germany and Norway) and technical background (lay and technical user groups). The results of the survey, with a factor analysis (PCA with varimax rotation) showed five factors, namely Intru-sion attitude: perception and awareness of intrusive situations to their privacy, Intrusion experience: past experiences of privacy intrusive situations, Effort for privacy trade-off : willingness to make an effort to protect their privacy, Pri-vacy for benefits trade-off : willingness to trade priPri-vacy for benefits trade-off, and Data minimization: the ambition to only enter mandatory information. Focus groups results have provided further details on different contributing factors to sharing more or less information; e.g. social pressure, contexts, online vs. offline. Finally, the complexity of users’ sharing behavior is high-lighted, and factors of reciprocity are entangled with privacy and its incentive for users. We discussed our results is in terms of privacy boundaries, attitudes, and experiences, as well as incentives, and reciprocities; factors influencing the sharing behavior of their information.

Paper VI – Making Secret Sharing based Cloud Storage Usable

In this paper, the focus was on the development of usable configuration man-agement of the secure storage system: Archistar of the Prismacloud project. Using the secure distributed cloud storage system, Archistar uses secret shar-ing as means to protect data. The work on this paper focused on technical users, who would be responsible for the configuration of Archistar in their or-ganization. The aim was to explore user’s requirements and restrictions for the configuration, as well as to investigate possible trade-offs towards supporting usable configuration. Following a user-centered approach, structured inter-views were used to derive requirement leading to the design of UI mock-ups. The mock-ups were evaluated using two iterations of cognitive walkthroughs. Results presented design guidelines and showed that configurations require technical, organizational, and legal expertise, making the task more complex where trade-offs occur. Additionally, we identified the need for support in solving trade-offs, such as setting parameters automatically. Therefore, we as-sert the importance of guidance even for technical users and further discussed different approaches used in the UI designs.

Paper VII – Analysis on Encrypted Medical Data In The Cloud, Should We Be Worried?: A Qualitative Study of Stakeholders’ Perspectives Our work took place within the Papaya project in this paper. The scope of the study included human factors in the eHealth use-case, dealing with homomor-phic encryption in the analysis on medical data in the cloud. Since medical data is considered sensitive data, privacy concerns are critical especially when outsourcing to the cloud or untrusted 3rd parties. The technical development is focused on enhancing the privacy of medical data using machine-learning,

18 Introductory Summary

where analysis is done on encrypted medical data. We aimed in this paper to explore stakeholder’s perspectives, analyze their mental models, and investi-gate possible trade-offs. We have used semi-structured interviews to explore perspectives and concerns of relevant stakeholders with technical, medical, and research expertise. In total, we conducted 14 interviews. Our results present the agreement of all stakeholders to the significance of medical data protection, however differences were indicated in trusting the technology. In addition, possible trade-offs and reassurances for trust were highlighted.

7 Conclusions

In this thesis, we addressed the design challenge of crypto-based technologies by highlighting and tinkering with some of the different aspects and factors in-volved. Throughout our studies, we have been using user-centered approaches to explore users perspectives, mental models, behaviors, and trade-offs. Our tinkering has been in the process of bringing different variables, technological, legal, and human factors, together with data privacy. In tackling the wicked problem of data privacy, identifying and tinkering of trade-offs between nological, legal, and human aspects, is needed. Users’ familiarity with tech-nology, their technical background, and their privacy attitudes are key factors to addressing the human aspects for design.

Contextual factors are important for trust, apart from privacy enhancing notions such as accountability, transparency, verification, and authentication. However, roles and responsibilities of different actors should be made clear. The burden of learning and acquiring technical knowledge should be mini-mized for the user, designs must adapt to existing mental models for intuitive functionality and usability. We believe that metaphors are important means for influencing privacy-friendly mental models.

The effect of experience is significant, and familiarity with existing tech-nologies have an influence on the extent of user acceptance of technology. In addition, it is important to consider different purposes, needs, and data types, hence, to customize designs accordingly. However, as shown in our studies, even users having technical skills still require default setups, support for deci-sion making, and easy to use configurations.

Considering human behavior in adapting privacy technologies entails un-derstanding their motivations. As our studies show, privacy is not always the most important incentive, relating to their contradictory behavior towards their privacy concerns. Circumstantial factors and other incentives are the reason why data privacy gets traded-off. Therefore, reciprocity is key in un-derstanding privacy behaviors and exploring trade-off decisions. Critical cases, such as those in medical data trade-offs, need guarantees for ensuring that util-ity is not compromised; the safety of patients is not put in jeopardy. Risk managements and guarantees must be provided for ensuring that the availabil-ity of medical data is not hindered by securavailabil-ity and privacy measures.

Future work should be focused more on the user’s specific technology needs, incentives, and requirements, for consequently designing solutions in

Tinkering the Wicked Problem of Privacy 19

support of different trade-offs. In addition, lessons learned from our work with projects is that HCI patterns and guidelines should be useful in earliest stages of the project work. We believe that a collaborative approach with user-led methods are suitable for addressing users’ needs and tackling their mental models of intuitive designs, and thus facilitate the adoption of PETs.

Acknowledgment of prior work

PhD dissertations in computer science at Karlstad university have two phases, where the PhD dissertations build upon the licentiate dissertations The work and content of this dissertation is continuation of our licentiate thesis [6].

References

[1] EU Commission: General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:

32016R0679&from=EN.

[2] Charter of fundamental rights of the european union. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/ legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012P/TXT, 2012.

[3] C. Abras, D. Maloney-Krichmar, and J. Preece. User-centered design. Bainbridge, W. Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publica-tions, 37(4):445–456, 2004.

[4] A. Adams. Users’ perception of privacy in multimedia communication. In CHI’99 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 53–54. ACM, 1999.

[5] R. Agarwal and J. Prasad. Are individual differences germane to the acceptance of new information technologies? Decision sciences, 30(2):361–391, 1999. [6] A. S. Alaqra. The wicked problem of privacy: Design challenge for crypto-based

solutions. Licentiate Thesis, Karlstads universitet, 2018.

[7] J. Alford and B. W. Head. Wicked and less wicked problems: a typology and a contingency framework. Policy and Society, 36(3):397–413, 2017.

[8] S. B. Barnes. A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. First Monday, 11(9), 2006.

[9] C. Bösch, B. Erb, F. Kargl, H. Kopp, and S. Pfattheicher. Tales from the dark side: Privacy dark strategies and privacy dark patterns. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 2016(4):237–254, 2016.

[10] R. Buchanan. Wicked problems in design thinking. Design issues, 8(2):5–21, 1992. [11] J. M. Carroll. HCI models, theories, and frameworks: Toward a multidisciplinary

science. Elsevier, 2003.

[12] J. M. Carroll, R. L. Mack, and W. A. Kellogg. Interface metaphors and user inter-face design. In Handbook of human-computer interaction, pages 67–85. Elsevier, 1988.

[13] A. Cavoukian. Privacy by design. Take the challenge. Information and privacy commissioner of Ontario, Canada, 2009.

20 Introductory Summary [14] M. Chase, M. Kohlweiss, A. Lysyanskaya, and S. Meiklejohn. Malleable signa-tures: Complex unary transformations and delegatable anonymous credentials. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2013:179, 2013.

[15] D. Chen and H. Zhao. Data security and privacy protection issues in cloud computing. In Computer Science and Electronics Engineering (ICCSEE), 2012 In-ternational Conference on, volume 1, pages 647–651. IEEE, 2012.

[16] H. Choi, J. Park, and Y. Jung. The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 81:42–51, 2018.

[17] R. Coyne. Wicked problems revisited. Design studies, 26(1):5–17, 2005.

[18] G. Danezis and S. Gürses. A critical review of 10 years of privacy technology. Proceedings of surveillance cultures: a global surveillance society, pages 1–16, 2010. [19] D. Derler, H. C. Pöhls, K. Samelin, and D. Slamanig. A general framework

for redactable signatures and new constructions. In International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology, pages 3–19. Springer, 2015.

[20] A. Dix. Human-computer interaction. In Encyclopedia of database systems, pages 1327–1331. Springer, 2009.

[21] S. Fischer-Hübner, C. Köffel, J. Pettersson, P. Wolkerstorfer, C. Graf, L. Holtz, U. König, H. Hedbom, and B. Kellermann. Hci pattern collection–version 2. Priv. Identity Manag. Eur. Life, 61, 2010.

[22] B. Friedman, P. Kahn, and A. Borning. Value sensitive design: Theory and meth-ods. University of Washington technical report, (02–12), 2002.

[23] J. Gantz and D. Reinsel. The digital universe in 2020: Big data, bigger digital shadows, and biggest growth in the far east. IDC iView: IDC Analyze the future, 2007(2012):1–16, 2012.

[24] D. Gefen, E. Karahanna, and D. W. Straub. Trust and tam in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS quarterly, 27(1):51–90, 2003.

[25] K. Hill. How target figured out a teen girl was pregnant before her father did. Forbes, Inc, 2012.

[26] E. Karnin, J. Greene, and M. Hellman. On secret sharing systems. IEEE Trans-actions on Information Theory, 29(1):35–41, 1983.

[27] M. Kosinski, D. Stillwell, and T. Graepel. Private traits and attributes are pre-dictable from digital records of human behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15):5802–5805, 2013.

[28] S. Lohr. The age of big data. New York Times, 11(2012), 2012.

[29] T. Lorünser, D. Slamanig, T. Länger, and H. C. Pöhls. Prismacloud tools: a cryptographic toolbox for increasing security in cloud services. In 2016 11th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES), pages 733–741. IEEE, 2016.

[30] W. E. Mackay and A.-L. Fayard. Hci, natural science and design: a framework for triangulation across disciplines. In Symposium on Designing Interactive Sys-tems: Proceedings of the 2 nd conference on Designing interactive sysSys-tems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques, volume 18, pages 223–234. ACM, 1997. [31] D. H. McKnight, V. Choudhury, and C. Kacmar. Developing and validating trust

measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information systems research, 13(3):334–359, 2002.