Mälardalen University Dissertations No. 6

DYNAMICS OF THE INTERNET

A Transformation Analysis of Banking and Finance

Anita L Du Rietz

2003

Department of Innovation, Design and Product Development Mälardalen University

Copyright © Anita L. Du Rietz, 2003. ISBN number: 91-88834-07-7

Printed by Arkitektkopia, Västerås, Sweden Distribution: Mälardalen University Press

Abstract

The subject of this study is industrial transformation. Our purpose is to follow how the emergence of the Internet has influenced the Swedish banking and finance sector. After 1995 the Internet diffused rapidly throughout the economy. To what extent has the Internet transformed the industry? Is the diffusion of this new technology facilitating the operations of small firms relatively to large firms? One answer to this question is that large firms, reaping economies of scale and scope, benefit from certain aspects of this technology while small firms, characterized by entrepreneurship and flexibility, benefit from other advantages of the new technology. The industry transformation outcome is hard to predict, except for the fact that the introduction of innovations, as the Internet, may improve efficiency and promote growth. The theory of Experimentally Organized Economy (EOE) suggests that every business idea, firm or innovation can be seen as an economic experiment, tested in the market. A great number of business experiments will increase the possibility that a large number of successful ones are singled out in the market selection.

In chapter 2, the characteristics of economies of scope and economies of scale in banking and finance are discussed. The introduction of the Internet transforms variable costs into fixed ones, favoring large companies taking advantage of economies of scale, something that increases entry barriers. On the other hand the Internet breaks the personal relations between banker and customer, making the latter more prone to accept new providers of financial services.

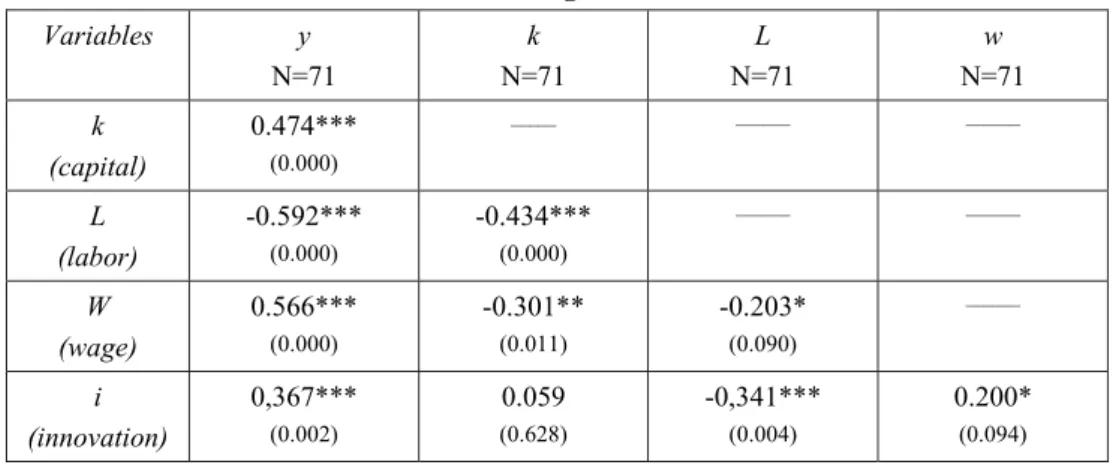

In chapter 3 we estimate a production function econometrically, where some production factors as well as Internet technology are assumed to explain productivity growth in five Swedish banks. Our results suggest that banking productivity correlates positively with innovation output, even when controlling for the skill composition of labor as well as for the physical capital intensity. A one per cent increase in the number of Internet payments will increase productivity (change in value added) with 0.44 percent in four main banks (2000:1-2002:2) and with 0.83 per cent in two Internet pioneers from 1997:4.

In chapter 4 the industry transformation is tested empirically using regression of employment growth on firm age, size and turnover of firms. The theory of the EOE states that a high rate of firm turnover should increase growth. Our results suggest that the turnover rate has a positive and significant impact on employment growth in the finance sector in regressions on two-year period data, in contrast to regressions with annual observations. The estimates for firm age are negatively related to industry growth. Belonging to an enterprise group has a positive impact on growth.

In chapter 5, we study the relationship between new Internet technology, average firm size, net-entry in three size classes and growth rate are examined in thirteen Swedish finance industries between 1993 and 2002. The average size of firms has been halved from 24 to 12 employees per firm during this period. The dominating industries such as banks and insurance companies have both reduced their number of employees. Our results suggest that we cannot draw any specific conclusion from the estimates with net-entry variables, but the estimates for average firm size is negatively related to growth. The parameter estimates of the technology variable have a strong positive and significant impact on growth.

Chapter 6 describes an on-going business experiment in the EOE context of MBT, mobile business transactions - Ericsson’s Jalda-EMCP and we discuss how the Internet is creating new applications for banking services. With the introduction of MBT, e-commerce may develop faster in the future and open up business opportunities for intermediaries in the value-chain from producer to consumer. ISBN: 91-88834-07-7

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A range of people and organizations has contributed to this dissertation in one way or another.

First of all I want to thank my dissertation committee, Professor Bengt-Arne Vedin, Sten Ekman, Ph.D. and Head of the Dep.of Innovation, Design and Product Development and Professor Roland Andersson, all three from Mälardalens Högskola, for having offered me this opportunity and for their support over the past 2,5 years.

Financial support for this project was provided by the “Ruben Rausing Foundation for Research on Entrepreneurship and Innovation”, which is gratefully acknowledged.

I am indebted to my advisor, Bengt-Arne Vedin, for numerous suggestions and useful comments. His generous commitment throughout the entire project has been of great value. Dan Johansson, Ph.D., Ratioinstitutet, has also assisted me with theoretical discussions as well as with solving data problems and his continuous support has been vital for my work.

Furthermore, I want to thank those who have given me valuable empirical and statistical comments: Roger Svensson, Associate Professor, Industriens Utredningsinstitut, Stockholm, Almas Heshmati, Ph.D., The United Nations University, Helsinki and Per-Olov Edlund, Associate Professor, Stockholm School of Economics. Roger Svensson offered important suggestions for chapter 2 and he generously contributed giving comments about the empirical estimations in chapters 4 and 5. Discussions with Almas Heshmati provided me with some vital comments for finishing the empirical estimations in chapter 3 and his friendly support was important during that part of the project.

Kent Bogestam, Ericsson AB and Joachim Ahlm, now at Bankgirocentralen, have generously provided me with information for chapter 6 concerning mobile business transactions in general and the Jalda-EMCP project in particular.

I would like to thank Ulla Lundqvist, Rolf Marquardt and Johan Hansing at Bankföreningen (Swedish Bankers´ Association) for their kind assistance concerning bank issues, during the project. I am also obliged to personnel at Finansinspsektionen (Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority) and Svenska Försäkringsföreningen (Swedish Insurance Society) for allowing me into their record offices for my data collecting. Among many kind people at Statistics Sweden I feel foremost indebted to Urban Fredriksson. Discussions with Anders Bjällskog, Sveriges Riksbank, have also been valuable.

Without the kind reception from bank officials the unique Internet-data set in chapter 3 would never have been collected. Therefore I am indebted to Anders Johannesson, Svenska Handelsbanken, Magnus Gustafson, Sparbanken Finn, Mattias Carlsson, SEB, Therese Karlsson, FöreningsSparbanken, Sven Holm, Nordea, and Göran Lenkel, SkandiaBanken.

The friendly and professional assistance of the librarian staff at Mälardalens Högskola in Eskilstuna is gratefully acknowledged, and special thanks go to Juliana Cucu.

Finally, I am grateful to a beloved husband for his confidence in the project and an encouraging attitude towards my working situation.

Contents

1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

1.1 Introduction...1

1.2 The Experimentally Organized Economy...4

1.3 Research Questions...6

1.4 Data...7

1.5 Limitations...8

1.6 Outline and Main Results ...9

2. INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES AND INNOVATION TRANSFORM BANKING 2.1 Introduction ...13

2.2 Economies of Scale ...15

2.3 Economies of Scope ...17

2.4 Lower Barriers to Entry with Internet Banking ...20

2.5 Deregulation ...23

2.6 Entry and Exits ...26

2.7 IT-Innovations and Branches...28

2.8 Internet Adoption...30

2.9 Internet in Banking ...32

2.10 Summary...37

3. PRODUCTIVITY IN INTERNET BANKING 3.1 Introduction ...41

3.2 Theoretical Discussion ...42

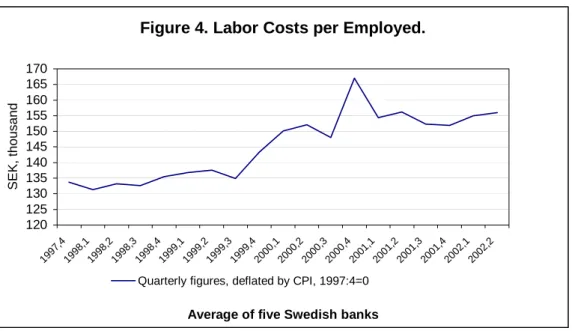

3.3 Internet – Labor Saving? ...47

3.4 The Production Function...51

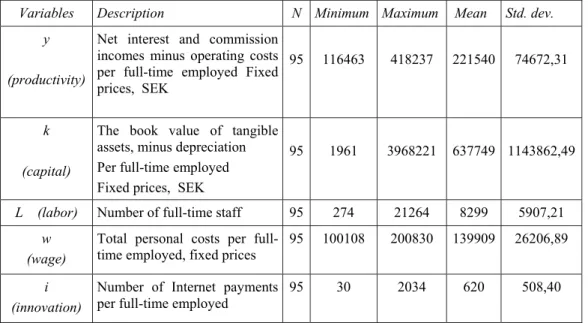

3.5 Data and Definitions ...55

3.6 Empirical Results ...58

3.7 Summary and Conclusions...63

Appendix...66

4. INDUSTRY DYNAMICS: AGE, SIZE AND TURNOVER OF FIRMS 4.1 Introduction ...67

4.2 Prior Studies ...67

4.3 Data and Descriptive Statistics ...71

4.4 Empirical Model ...74

4.5 Hypotheses, Definitions and Correlations ...76

4.6 Empirical Results...80

4.7 Summary and Conclusions ...85

5. INDUSTRY GROWTH AND FIRM SIZE DISTRIBUTION IN THE FINANCE SECTOR

5.1 Introduction ...89

5.2 Data and Descriptive Statistics ...92

5.3 The Empirical Model...96

5.4 Hypotheses, Definitions and Correlations ...97

5.5 Empirical Estimations...99

5.6 Summary and Conclusions ...102

Appendix ...104

6. MOBILE BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS - A NEW TECHNOLOGY FOR PAYMENTS 6.1 Introduction ...107

6.2 Path Dependence and Path Creation...108

6.3 E-Commerce Payments ...109

6.4 Telecommunications offer new Services...112

6.5 Jalda – Ericsson Mobile Commerce Platform ...113

6.6 Digital Certificates...116

6.7 A New Infrastructure for Payments? ...118

6.8 New Creative Competition ...121

6.9 Summary...123

1.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

1.1 Introduction

An evolutionary or dynamic process is often tantamount to growth. The mechanisms behind growth are here decomposed into phenomena such as firm entry, expansion and exit, contraction, redistribution of resources as well as innovations. A dynamic process generating growth has much more complex dimensions, but economic studies have to be confined to measurable variables that to some extent grasp the growth phenomenon. This work is no exception and its intention is to study industrial transformation, both economic growth and decline. Transformation analyses, in contrast to growth analyses, focus on causal chains outside the scope of growth, on disequilibria and chain effects created among other things by entrepreneurial activities, market processes and competition as a dynamic force (Dahmén [1984]).

Our purpose is to follow how the emergence of the Internet1 has influenced the Swedish banking and finance sector. Due to deregulations and diffusion of IT during the last decades and a recent adoption of the Internet the sector has gradually been transformed. The banking and finance sector has been chosen because it is playing a crucial part in economic growth, being a vital sector and actor in financing other ventures/businesses and as such pivotal in the transformation of the whole economy.

Technological change and related economic performance in the service sector is often neglected in economic analyses (Triplett & Bosworth [2000]). Manufactured products are tangible, stored, transported long distances and often subjected to considerable economies of

scale resulting from investments. But services continue to be immaterial and have displayed

low capital intensity, not aiming at mass production with economies of scale. The service sector tends to be exposed to a “cost disease” if wages and salaries increase at the same pace

1 Until 1993 the Internet primarily was used by universities and some businesses to exchange messages and

files. Then the World Wide Web was developed by CERN in Switzerland and MIT in the US to provide a ’distributed hypermedia/hypertext’ system. (Slack, Chambers and Johnston,[2001, p.241]).

as in the cost efficient goods producing sector, which exhibits a higher productivity growth. The service sector is also extremely heterogeneous (Vedin [1989]).

One way to cope with cost increases has been to introduce information technology (IT)

applications. The service sector has adopted computer and communication technologies, at

least kept in step with the manufacturing sector. Banking was probably the first major service industry which adopted new information technologies extensively (de Wit [1990]), profiting from its versatility (Holst & Vedin [1983, 1991]).

The Internet is a vital infrastructure for communication, collaboration and information sharing and it contributes to efficiency improvements and productivity gains as well as to a host of innovations (Vedin [1999]). After 1995 the Internet diffused rapidly throughout the economy. At a relatively low cost the Internet has connected the existing capital stock of computers and communications system into an open network that significantly increases the utility of the component parts. The Internet reduces the communication costs in facilitating and speeding up the diffusion of codified knowledge and ideas. Communication can take place independent of time or geographical location (Vedin [1993], [1995]).

There is a large literature and a continuing debate in economics regarding innovation and the role of large versus small firms in different industries (see Carlsson [1999] and Acs [1996]). On one hand, large firms may be expected to introduce innovations at an early stage and adapt to new technology by virtue of their ability to reap economies of scale and scope; spreading fixed costs over a larger output and a greater product range, having greater ability to appropriate the results of R&D, and being able to take greater risks. On the other hand, small firms may have advantages such as being less bureaucratic, being able to exploit innovations that are of too modest importance for larger firms, and providing more direct personal incentives (Vedin [1984]). On balance there is a role for both large and small firms and they may have more or less advantages in different industries.

A related question is to what extent a new technology as the Internet facilitates the operations for small firms relatively to large firms. One possible answer to this question is that large

firms, reaping economies of scale and scope, benefit from certain aspects of this new technology while small firms, characterized by entrepreneurship and flexibility, benefit from other advantages. The outcome on industry transformation is hardly predictable, except for the fact that the introduction of innovations, as the Internet, may improve efficiency and promote growth. With a new technology emerging, one cannot exclude changes in entry barriers, in the relationship between capital and labor, in transportation costs and in the network of small sub-contractors working for large firms. These are some examples of economic phenomena included in the concept of industrial transformation, subsequent to an introduction of new technology.

1.2 The Experimentally Organized Economy

The approach here, called the Experimentally Organized Economy (EOE), has its origin in the Schumpetarian theory as well as in the Swedish tradition emanating from Knut Wicksell, Johan Åkerman and Erik Dahmén (Dahmén [1984, 1989]). EOE has been further developed by Gunnar Eliasson (1996, 1999, 2002a and 2002b) (for a review see Johansson [2001]). For our purpose there are several important parts of the approach that will be elaborated here2.

Starting with the concept of combinations we can designate the state space as being all potential technical and organizational combinations that may exist in our knowledge (for example the knowledge available through the Internet). But far from all of these combinations in the state space are feasible in an economic sense. Instead there is a subset of state space that holds all the feasible profitable combinations, the business opportunity set. For an entrepreneur and a businessman it is an important task to identify the solutions that lie in the relatively confined business opportunity set existing at a specific point of time.

The EOE approach entails a number of assumptions:

1. The state space and its subset, the business opportunity set, are assumed to be open-ended in the long run. The openness rests on the characteristics of knowledge,

implying that the state space expands through exploration and learning, i.e. the discovery of new combinations. The totality of knowledge assembled will grow the more we search for knowledge.

2. Increasingly, the existing stock of knowledge is assumed to be tacit. Tacit means that the knowledge to a large extent is difficult to codify and communicate (see Polyani [1967]). Information is here defined as a subset of knowledge, constituting codified knowledge.

3. The economic actors and entrepreneurs are assumed to act within the confines of bounded rationality, i.e., they have limited cognitive capacity to understand and analyze information (see Simon [1955, 1990]).

The knowledge paradox can be stated from the assumptions above. Even if the knowledge base of society expands, individual actors nevertheless become increasingly ignorant about all there is to learn, since knowledge is created faster than one can learn. The individual actor must choose to specialize in a clearly defined field. It is impossible for any actor or person to survey the whole economy or the whole market they are operating in. The actors’ focus lies in coordinating their activities even when they have information about various opportunities that are incomplete, fragmented, difficult to interpret and very often deceptive (see Hayek [1945]). Consumers and producers never have complete information about preferences or technology. Consumers have to discover the goods/services they will choose while the suppliers have to find out the best ways to produce and distribute goods and services efficiently. The economic actor has turned into a detector.

From this discussion the conclusion can be drawn that it is unlikely that any entrepreneur will act with optimal efficiency. The very business idea is to explore and expand the business opportunity set. The entrepreneur can introduce new combinations or innovations. But s/he will act with little information about possible economic outcomes. Every business idea, innovation, project or firm can be seen as an economic experiment, tested and controlled in the market against a business hypothesis, the original business idea. The economy is experimentally organized. Various forms of electronic commerce, with relatively low entry barriers, can be seen as business experiments.

Business mistakes are included in the costs of an economy for selection of winners and cannot be regarded as a net waste of resources. The more business experiments that are tested in the market the larger is the possibility that some of the experiments will be successful. A great number of business experiments will increase the possibility that the successful ones are singled out in the market selection. The industrial development will then depend on the number of business experiments carried out, both successful and unsuccessful ones. To make the successful experiments survive there are, according to the EOE-theory, other requisite “modules”, such as the competence bloc (Eliasson, G. & Å. Eliasson [1996]), institutions and social capital (Eliasson, G. [2002a, pp. 13]).

For the long run survival of the firm a businessman has to become a detector, incessantly searching for the most efficient and competitive ways to develop and produce goods and services demanded. If so, an efficient and flexible market behavior of the incumbents will be the strongest barrier to entry. Many new business experiments, i.e., new firms, will not be successful because existing firms are efficiently making use of new technology in meeting the demand.

In the long run, productive resources will constantly be reallocated to meet the demand. Emerging new technologies, as the Internet, will play a part in improving efficiency and productivity in the market, both within existing firms and in the entering new firms.

1.3 Research Questions

The research questions are partly related to the theory of EOE – how new technology contributes to industry transformation, with empirical analyses of the Swedish banking and finance sector.

The Internet is one important new technology emerging. Incumbents in banking and finance rely upon it for the introduction of innovations. New firms enter carrying out business

experiments. Successful ones are singled out through the market selection process. In the long run productive resources will be reallocated and successful incumbents as well as entrants grow.

Five questions are addressed:

1) Has the adoption of Internet banking had an impact on productivity so far?

2) What characterizes the transformation of the finance industries? Have small, young and independent new entrants a significant impact on growth, supporting the EOE-hypotheses?

3) Is a high rate of firm turnover, entries plus exits of firms, promoting industry growth? 4) In a service sector like banking and finance, has net-entry of small firms or large

entrants a stronger impact on growth?

5) Has the Internet affected growth in the finance industries?

1.4 Data

In order to study the Swedish banking and finance sector we have collected two unique data sets.

No productivity measures exist at a lower digit level in banking and finance in official statistics. The only value-added figures that are available annually are on an aggregated level for the whole sector. This lack of value-added data exists in many service sectors and therefore growth has to be measured in employment terms. We have solved this productivity lack problem for five banks by computing their value-added data using annual reports and quarterly reports respectively.

Firstly, we have collected a unique data set for the main Swedish banks (applied in chapter 3), consisting of quarterly observations from late 1997 to mid-2002 covering five banks having introduced the Internet in the second half of the 1990s. The Internet diffusion figures have been collected from each bank and have not previously been published officially. The

rest of the data set originates mainly from annual reports and quarterly reports respectively and if lacking, they have been supplemented by assistance of bank officials. The banks are FöreningsSparbanken, Nordbanken (Nordea Bank Sverige), SEB (Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken), Svenska Handelsbanken and Sparbanken Finn. These banks cover about 88 percent of the total Swedish banking market.

The second data set (in chapter 4 and 5) embraces the whole finance sector including all banks. The author has collected information from old file documentation assembled by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (Finansinspektionen; FI). There is a full scale investigation of firms, existing at any time between 1993 and 2001, containing data from about 2200 entities concerning age, ownership structure, entry and exits. The remaining data of industrial employment growth is drawn from the annual survey conducted by Statistics Sweden (Statistiska Centralbyrån; SCB), with records from individual establishments. These establishments are classified into industries on a five–digit level.

1.5 Limitations

The use of Internet banking in Sweden diffused rapidly from 1996 onwards. In 2002 one third of all banking customers used the Internet. In fact, we are studying a very early phase of the adoption of a new technology and cannot exclude the possibility that our empirical studies would have been different if the Internet data set had been larger.

Furthermore, data on IT employed staff and data of investments in IT and the Internet accumulated over time have not been available for this study. The banks have not allowed us to get access this information. A consequence of this is that we have to substitute an input approach (invested accumulated R&D-capital) with an output approach (the share of Internet payments) in chapter 33.

3 A Swedish example of the input approach, with R&D investments, is in Du Rietz, A. (1975) applied to three

manufacturing industries; iron and steel, chemical and forest-based industries.

Borttaget: during the period 1993 to 2001. The entries have been between 0.24 and 37 percent of all firms annually and the exits have annually varied between 0.85 and 18 percent

One weakness in this study is the limited focus on rules of institutions and the importance of the deregulation of the Swedish capital market during the last two decades. The scope of such an analysis would be too large to incorporate in a study focusing on Internet-linked innovation. Here capital market-deregulations are regarded more or less as historical facts, with some influence on the size distribution of firms during the periods studied. In chapter 2 the process of deregulation is briefly described chronologically, without any analysis of the impact of each deregulation step. An analysis of deregulation would best be performed in a political, socio-economic context, beyond the scope of this dissertation.

Another weakness is the fact that we have not been able to estimate the impact of a well-functioning competence bloc (Eliasson [2002a]). Furthermore, we have not been able to use variables for economies of scale and scope in order to estimate their impact on industry growth.

Nor have this study taken account of the preferences of various actors within socio-economic groups for starting up businesses, for pushing innovations or for expanding the operations.

1.6 Outline and Main Results

In chapter 2, the characteristics of economies of scope and economies of scale in banking and finance are discussed. There are two opposite industry impacts of the new Internet technology. The introduction of this technology transforms variable costs into fixed ones, favoring large companies taking advantage of economies of scale, something that increases entry barriers. On the other hand the Internet breaks up the personal relations between banker and customer, making the latter prone to accept new providers of financial services. The emergence of remote access delivery technologies reduces the significance of traditional barriers, such as an extensive branch network.

The historical development of the Swedish bank and finance sector is described with focus on institutions and innovations. The different steps of the deregulation process are presented,

followed by the emergence and adoption of the Internet. This provides a mainly descriptive historic part of the transformation analysis.

In chapter 3 we econometrically estimate a production function, where several production factors as well as Internet technology are used to explain productivity growth in five Swedish banks for the period 1999:4 - 2002:2. Our results suggest that innovation output has a significantly positive effect on banking productivity, even when controlling for the skill composition of labor as well as the physical capital intensity. A one per cent increase in the number of Internet payments improves productivity (change in value added) with 0.83 per cent, when the data set consists of the two large Internet pioneering banks. The results suggest that for the four main banks the corresponding productivity increase was 0.12 per cent for the whole period and 0.44 per cent for the last part of it (2000:1-2002:2). We have also tested returns to scale. The estimations indicate decreasing returns to scale, when all banks are included. Our results suggest that a further diffusion of the Internet has entailed a production structure characterized by stronger negative returns to scale from 2000 onwards than during the previous period.

For these pioneers, a reduction in the number of employees and higher salaries for the remaining employees has developed during the diffusion period of Internet services in banking. The results from our study indicate that large banks display similar production functions and along with the diffusion of Internet bank services they reduce their number of employees. A smaller Internet banking pioneer in our sample has experienced a different development. This bank expands in number of employees and branches but tries to keep investments in premises low.

In chapter 4 the industry transformation is tested empirically by use of firm age, size and turnover of firms. The theory of the EOE offers predictions regarding the role of entry and exit and turnover of firms. The theory states that many entries and exits and a high rate of firm turnover should increase growth. As more business experiments are carried out the larger are the possibilities for selecting winners and thus for the industry to grow. There is also a discussion among economists about the possible positive impact of small and young

firms on industry growth. Employment growth is usually explained by variables such as age, size, belonging to a group of firms and turnover rate of firms, applied to a unique data set over the period 1993-2001 in eleven Swedish finance industries.

Our hypotheses are that firm age and firm size are negatively related to growth and that a high turnover rate has a positive impact on growth. Our results show that the turnover rate have a positive and significant impact on employment growth in regressions on two-year period data, in contrast to regressions with annual observations where the estimated parameters are non-significant. The estimates for firm size are not significant in the two-year period regressions. The estimated coefficients for the age variable are negative in all regressions of industry growth.In this study, belonging to an enterprise group has been found to have a positive impact on growth. A high turnover rate would generate dynamic forces in

service industries such as the Swedish finance sector, and in addition to what has been

suggested in previous studies our results indicate that this effect on industry transformation becomes important in the long run.

In chapter 5, we study the hypothesis that entrance of small firms plays a role in experimentation and innovation leading to technological change and industry growth. The relationship between new Internet technology, average firm size, net-entry in three size classes and growth rate are examined in thirteen Swedish finance industries for the period 1993-2002.

The results do not permit us to draw specific conclusion from the estimates with net-entry variables. But the estimates for average firm size are negative and significantly related to employment growth. The parameter estimates for the technology variable suggest a strong positive and significant impact on growth. These results contribute to the picture of industry transformation in the Swedish banking and finance sector, where the average firm size in the financial sector has been sharply reduced from 24 to twelve employees between 1993 and 2002. The vivid entry of new, small establishments has not been enough to compensate for the reduction in the number of employees through discontinuations and reduced employments in firms already existing.

Borttaget: s

Borttaget: and significant s Borttaget: in the finance sector.

Borttaget: ¶

Chapter 6 describes an on-going business experiment in the EOE context of mobile business transaction (MBT) - Ericsson’s Jalda-EMCP and we discuss how the Internet is creating new applications for banking services. With the introduction of MBT, e-commerce may develop faster in the future and open up business opportunities for intermediaries in the value-chain from producer to consumer. We use the case study Jalda-EMCP, a new technology for payments based on MBT, when discussing the potential impact of social and institutional influences. The emergence of a novelty may turn into or be affected by the phenomenon of path dependence, where temporarily remote events play a key role in the development of novelty and the consequence is that actors have limited power to exert real time influence. The contrasting perspective is path creation, which can be described as the entrepreneurial need of escaping market selection pressures by designing new technological fields, to open up new parts of state space, integrating them in the business opportunity set. The actors involved - merchants, banks and operators – may be seen as path dependent. Moreover, actors have different interests, technological capabilities, power, belief systems and expectations. Credit card companies continue to work for new secure card payment solutions. The MBT innovators will create niches, where the MBT technology is said to be superior, when it comes to micro-payments and payments over the Internet. For Jalda and all other MBT initiatives there are important issues to grasp beside security and standardization, such as making each actor involved in the transaction-payment link a profit-maker.

2. INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES AND INNOVATION

TRANSFORM BANKING

2.1

Introduction

For the whole economy, computer and information technology is considered to constitute a new techno-economic paradigm not just requiring new technology investments but also changes in the institutional structure (see Helpman, 1998). Probably, the finance industries

were the first of all service sectors to introduce computer technology and today it may be considered a sector having an outstanding experience in the field of automation and IT,

dating back some four decades (de Wit, 1990).

Why has there been such a high rate of IT application in the financial sector?

1) The production process in the finance sector is suitable for IT applications, such as the storage of data, account numbers, individual data such as addresses and personal

social security numbers (in Sweden) and also the processing of modifications in data

as a consequence of payment transfers, withdrawals or deposits.

2) Many bank services are nowadays so standardized that the customers can do the job themselves. The services are produced and sold and transferred securely by the Internet.

3) Bank customers get the advantage of a better overview of their accounts and transactions. They can decide when and where they will have their bank service performed.

On the other hand the competition has increased with deregulation in Sweden.

1) Banks and other finance institutions have found themselves operating in a deregulated Swedish market. In the previous regulated market, bank authorization was given to establish a new branch. Branching was practically the only means of competition

when regulations suppressed various kinds of product diversification as well as price competition.

2) The European Single Market has been designed to foster competition and to achieve efficiency gains. Suppliers with the best and cheapest financial products and services should be free to operate throughout the whole European Market. This has opened up new opportunities for actors entering remote markets and reaching new customers by way of the Internet.

Deregulation of the finance sector has reduced entry barriers and thus increased competition. Tougher competition has forced many firms to profile their operations and to invest in innovations and new technologies, such as the Internet.

Further inroads of the Internet will both reduce and increase entry barriers in the finance sector. There are two effects that have opposite effects. The Internet is transforming variable costs into fixed ones and this favors large companies taking advantage of economies of scale. Entry barriers increase because of scale economies. On the other hand the Internet breaks up the personal relations between customers and banker. This makes the bank customer more prone to accept new providers of financial services. Traditionally, investments in an extensive branch network have been regarded as the primary barrier to entry and to the

expansion of small banks. Now the emergence of remote access delivery technologies reduces the significance of such a barrier.

In this chapter we will describe the development in the banking sector from two perspectives: technological change and the liberalization, through deregulation. Related to technical

2.2

Economies of Scale

Before the IT and Internet era, traditional bank services constituted labor intensive activities, such as: deposit, withdrawal and transferring as well as foreign exchange and trading at the stock exchange. Then banking was characterized by relatively low fixed costs and high variable costs (e.g. compared to manufacturing). More investments in new technology mean that fixed costs have come to substitute variable costs. This opens up for economies of scale. Economies of scale arise when output can be doubled (e. g.) for less than a doubling of costs. Scale economies imply that the same product/service should be sold to as many customers as possible.

The economies of scale for commercial banks operating in the US have been extensively studied (for a review see Rezvanian & Mehdian [2002]). The results of parametric tests indicate that the average cost curve for banks in Europe and the US is U shaped and economies of scale exist for small and medium sized banks. Studies based on the non-parametric technique have assessed the production performance of various samples relative to a constructed best practice frontier. For the US banking industry, studies give estimates of the overall efficiency ranging between 65% and 90%. When including other studies from a great many more countries, the results reveal an average efficiency of around 77% and a median one of 82% (Berger & Humprey [1997]).

There are results from the US suggesting that the size at which scale economies are exhausted may have increased between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s (Wheelock & Wilson [2001]). This seems to be an indication that the new IT, before the Internet, gradually has moved the bottom of the average cost curve outward. In a study of 64 Swedish banks the technical efficiency was estimated for the year 1995 (Ponary Mlima [1999]). Commercial banks were more efficient than savings banks, operating at the 93 percent compared to savings banks’ 78 percent. The calculations of scale elasticities showed that most banks were operating very close to optimal scale. This might be the reason why Swedish banks after mid-1990s have been highly active in cross-border acquisitions and mergers. They were almost forced to look beyond the Swedish borders to find space for continued growth (Sveriges Riksbank;

Financial Stability Report [2002 pp.72, 74]). But the level of strategic risk increases when the banks expand outside Sweden (Financial Stability Report [2002 p.81]). And during the last years the banks have consolidated their holdings and turned more of their interest to developing Internet banking.

There are product-specific economies of scale with respect to loans and securities and diseconomies of scale with respect to “other earning assets”, according to the results from estimates in a sample of Singaporean commercial banks in 1991-1997 (Rezvanian & Mehdian [2002]). These findings suggest that the marginal cost of producing loans and securities falls short of its average cost, which in turn implies that an expansion of banks through an increases in their loans and securities is cost effective. The reverse holds for “other earning assets”. There were also statistically significant product-specific economies of scope indicating that producing all outputs jointly is less costly than production of each output separately.

With Internet banking the fixed costs in IT investments have become relatively higher and the variable costs relatively lower. The fixed costs have increased even more and substituted for the variable costs from a labor-intensive branch network. This holds for many transactional services i.e. those services performed over the bank counter: all kinds of money transfers between accounts, checking accounts, payment of bills, purchase and sale of securities and units in mutual funds, advice and information. The websites of many banks now serves as portals to ‘financial department stores’ offering a wide range of services and products. This opens up for further economies of scale. The larger number of finance services performed via the Internet, the higher the income to cover each firm‘s fixed costs. Marginal costs per transaction are reduced as the number of transactions increases. Banks can reduce their total costs and improve profitability. So finance firms entering have an incentive to increase operations and the number of services, after having invested in the Internet. There ought to be a trend of increased volumes of operations per firm.

Diseconomies of scale are often discussed in relation to transportation costs and complexity costs. Transportation costs can be high for large operations in manufacturing and trade and

complexity costs, for communications and coordination, tend to increase faster than capacity as size increases. After the emergence of the Internet these well-known factors promoting diseconomies of scale may have lost in importance. On the other hand the Internet dissolves these tendencies to diseconomies of scale at large size operations. Firstly, there is no physical delivery of services and thus no problems with transportation. Secondly, complexity costs, for communication and coordination, are substantially reduced with this new technology. This gives rise to increased economies of scale compared to the situation before the arrival of the Internet.

There are other services such as advisory services to private customers and merchant banking business: including all kinds of advisory financial services, brokerage and research within capital and debt markets, project- and trade finance, corporate finance with acquisitions, venture capital investments and security related financing solutions. These advisory services are still personnel intensive even though a lot of financial information is available on the web and gradually have been transferred to the Internet.

The Internet is very useful for simple and standardized services, when the customer can do parts of the job by him/herself. This means that the low paid jobs would disappear in the finance sector. There are great possibilities to substitute new technology for labor (as shown in chapter 3). This is true for transactional services, but within advisory services there is a demand for expert assistance in order to continue to build on the trustworthiness and increase economies of scope.

2.3

Economies of Scope

Economies of scope arise when the combined multi-product output of a single firm is greater than that which would be achieved by two different firms each producing a single product.

There are gains believed to be associated with the joint provision of bank deposits and loans, something constituting a primary argument for expanding banking services to new activities such as insurance, real estate, underwriting, etc.

In fact there ought to exist production4 and consumption synergies in banking. For corporate customers there are transaction, payroll, cash management and foreign exchange services provided in combination with working capital credit, commercial loans and leasing. For retail customers there are transactions and savings services on the deposit side in combination with installment, mortgage, and credit card financing on the loan side.

Consumption synergies arise from reductions in user transaction, transportation and search costs associated with consuming financial services aggregated from the same bank provider, often at the same location, rather than consuming these services separately from different providers at different locations. Bank customers should then be willing to reward joint provision up to the amount of savings they obtain from joint consumption. A direct payment, through higher fees and prices, adds to bank revenue. An indirect payment, through lower interest paid on deposits, reduces bank expenses. Thus banks should gain from supplying financial services jointly rather than separately.

These scope economies would imply that as many services as possible should be offered to any one customer. Belief in synergies of scope economies was strong during the 1990s. Many thrift institutions and credit unions lobbied for and obtained the capacity to expand their product mixes and became banks. Perceived synergy effects served as arguments for the removal of remaining restrictions on commercial banks extending their product lines with offers previously characterizing other, non-bank providers of financial services. Economies of scope also serve as a justification for the creation of ‘financial supermarkets’, where savings, credit-card, and other loans, insurance, real estate, and securities services are all offered jointly by retail firms.

4

Production synergies lower the costs because banks are able to: Spread fixed costs over a broader output, exploit complementarities in production of services and diversify risks.

In a monopoly or even in an oligopoly market we can assume that there are economies of scope to gain because the banks have the ability to set prices to take advantage of comprehensive offerings (market power). But a more interesting question is whether scope economies may exist in a perfectly competitive market?

The answer is yes if the following conditions are met:

Consumers must be willing to pay a premium for combinations or packages of bank services (consumer synergies are positive) and banks would experience diseconomies of scope on the cost side. For if there were no cost justification for charging higher prices for services provided in combinations, competition among banks would eliminate the revenue synergies, even if customers valued comprehension. Customers do not pay higher prices for the consumption of a combined offering because banks are not able to exercise their market power as it relates to providing deposit and loan services together. In the event that consumption scope economies are important but not reflected in prices, banks that do not provide the services jointly may still lose market share and profits to banks that do provide all the services, providing an incentive to continue to provide the services comprehensively.

The answer is no if: There are diseconomies of scope for the banks and consumers do not value joint consumption. Then the banks would rather become specialized. If there is no economies of scope the combined provision of these financial services may just constitute a historical artifact. Before the national and international money markets became so integrated and efficient at transferring funds, the raising of local deposits was much more efficient than other means of obtaining funds to make their local loans. This is no longer the case.

An indivisible asset, as the Internet, which yields scale economies, can similarly provide the foundation for scope economies. Two types of economies of scope can be distinguished (Teece [1980]): one based on the sharing of a specialized physical asset and the other based on the sharing of information. The first type is applicable in banking although it is for manufacturing that this type of economies of scope is often discussed. The use of the Internet displays economies of scale and these economies are not exhausted over the range of the market for payments. The Internet can also be used for performing other financial services,

thus economies of scope will exist in the delivery of both payments and other banking services. The second type – sharing of information – involves indivisibilities associated with obtaining information. Teece (1980, p. 226) predicted the economies of scope on the web: “…. the transfer of proprietary information to alternative activities is likely to generate scope economies if organizational modes can be discovered to conduct the transfer at low costs.” The acquisition of information often involves a set up cost, i.e. resources needed to obtain the information may be independent of the process where the information is used. This can be the cost of collecting information on a financial services or a financial institution of interest.

Assume now that banks may provide services jointly because of economies of scope on the cost side for the banks, a situation that may have been created by a new technology as the Internet. Cost synergies between deposits and loans may be quite small (Berger, Humphrey & Pulley [1996]), but they are measured to be positive on average and would therefore provide some motivation for joint production. The bank has a fixed cost attached to each customer. It has been costly to convince the customer that the bank is a reliable distributor of services (for a comparison with other services as consultants see Svensson [2000]). If the bank has convinced the customer about its trustworthiness and already taken the customer specific fixed costs, the bank benefits from selling as many products as possible to the very customer. Large financial companies may deliver a whole range of services. By this they had a special advantage over smaller firms, particularly before the Internet –era, when customers personally still had to call on a branch of each separate bank.

2.4

Lower Barriers to Entry with Internet Banking?

The transformation of the banking and finance sector is related to barriers to entry.

A previous strategy among banks has been to “lock in” customers by offering many different services, the range of services becoming a barrier to entry for new competitors. The explanation to this includes factors such as cost and discomfort when changing bank and the switching costs increase with the number of services a customer relies upon within the same

bank. Another barrier of similar type is the fact that customers traditionally have had confidence in and strong relations to bank officials at the local branch.

Traditionally, existing banks and financial institutions have strong advantages relative to new entrants. Their investments in personnel intensive branches, establishing trust, have created the foundations for an oligopoly market with substantial barriers to entry. The aim of successful banking has been to create a personal bond between banker and customer. Banking is very much about trust, according to common notions among bankers.

Since the emergence of the Internet, existing enterprises lost some of their advantages with branching. New firms could enter and create similar branch services at the Internet. With Internet banking growth, banks move away from being ‘relation banks’, becoming ‘transactional banks’ instead. Now customers to a less extent will get in touch personally with the banker at his office – a person the consumer usually had full confidence in. From this follows that customers find it easier to change bank or at least move part of their banking services to a specialized actor in the finance market, such as an Internet broker, e-bank or trust fund.

How may the Internet influence barriers of entry? Here we will discuss the impact of the two factors already introduced: economies of scale and economies of scope. The importance of

economies of scale seems to have become even larger with the adoption of the Internet.

Increased fixed costs combined with low variable costs make for lower marginal costs and create economies of scale. Diseconomies of scale will, after the advent of the Internet, show up at an increased size of operations. Most banks will probably expand their operations further. This expansion of scale economies will increase barriers to entry, relatively speaking.

But at the same time economies of scope work in the opposite direction, tending to lower the barriers to entry. The advantages with branches and customer trust of a physical presence are reduced. Bank businesses are said to be local, taking into account regional habits and customs. In banking it is important to have a well-known trademark. But very often it turns out that brand loyalty is low. In order to maintain brand loyalty in banking physical presence

is vital. The Internet tends to reduce the physical presence and to reduce possibilities to sell many various products to one and same customer.

Existing firms have invested in “confidence capital” during many years. They have gained the trust of their customers by delivering first class financial services. They can harvest economies of scope due to that feeling of trust from their customers. This has worked in favor of the large and old companies. When a new firm enters the challenge is to inspire the customers’ confidence in order to obtain market share. The newcomer tries to offer something special, such as innovative services, lower prices, higher yield or higher interest on deposits, more generous loans etc. The entrepreneurial offering defies existing service supply. The entrant has in the long run to produce services sufficient to reap economies of scope and scale.

If large firms that compete across the financial services market have lower costs in most areas because of economies of scope, then the outlook for niche firms is bleak. But the empirical evidence of economies of scope before the Internet-era is mixed (Berger & Mester [1997]).

Due to lowered entry barriers from deregulation and the IT/Internet technology entrants have emerged in all parts of the finance sector. Price competing telephone banks entered after the deregulation, in many cases in alliance with insurance companies or store chains, to win new customers. They were soon converted into Internet banks. A trend in Sweden has been that the banks have lost part of the business of managing the customers’ stock portfolios to new entrants, specialized net brokers.

The difference between Internet-applicable services (information and transaction services) and non-Internet-applicable services (advisory expert services) is blurred. More services may be fit to be offered over the Internet- today than just a few years ago. For the future this trend may continue and thus the development of lower entry barriers. The wider the range of financial Internet services, the more firms may offer them at the Internet in (price-) competition with all other actors and the lowest bidder establishes the barriers to entry.

Against this forecast stands the goodwill and trust that existing banks and financial institutions already have created.

During prosperous times in Sweden, as the in second part of the 1990ies, there was an increase in the number of financial firms (further discussed in chapter 4 and 5). But when an economic slowdown followed, during 2001 and 2002, many of recent entrants have got into economic problems. Customers probably prefer something “safe and sound” to accepting an offer from a newcomer. If a severe financial crisis were to emerge these kinds of loyalties and non-measurable values would probably come to the fore even more, and price-competition from new entrants be down-weighted in customers’ considerations.

2.5

Deregulation

During the last decade the Swedish bank and finance sector has been completely transformed. Before 1900 restrictions on bank foundations and operations in Sweden were few. Over the following 80 years restrictions gradually increased, especially after 1932 when the world depression 1929-1932 had caused the banks great losses. Up to 1930 the credit policy may be called market conform, which means that the government accepted the market functioning (Larsson [1998, p.200]).

In the 1980s a shift towards liberalization took place. Several of the previous restrictions on banking operations were removed, such as liquidity quotas, interest rate controls, credit limits and, finally, currency control. In 1986 banking law was changed so as to allow foreign banks to enter the Swedish market from 1987.

Main Periods in Swedish Bank Development

(Time periods are created on basis of the information given in Larsson [1998] and Werin [1993])

___________________________________________________________________________ Period Main Features of Legislation and Credit Policy

___________________________________________________________________________ 1824-1862 Foundation of banks:

Joint Stock Banks with Unlimited Liability (1824&1846) Joint Stock Companies (1848), Branch Banks (1851)

1863- 1894 The Bank Reform Act of 1863, created a lot of opportunities for a free capital market within the banking system --- free banking.

1895-1918 Legislation aiming to support a concentration of the banking industry, The Banking Law Act (1903 & 1911)--- central banking.

1919-1931 Legislation aiming to prevent concentration of the banking industry 1932-1940 Legislation concerning restrictions on the legal form of banks, and

restrictions of their possibilities to own shares --- low interest rates policy. 1941-1973 Regulation period: currency regulations, credit ration proceedings,

liquidity quotas, control of bond issues, control of interest rates, investments in state bonds regulated (1952 & 1955 & 1962 & 1975) 1974-1989 Deregulation period: deregulation of prices (interest rates) and lending

amounts --- lending limits, liquidity quotas, interest rate regulation. 1990- Integration into the European Single Market, and integration with

insurance.

___________________________________________________________________________

The deregulation period started 1974 when Swedish companies were allowed to borrow abroad. From 1982 they could issue bonds without restrictions. This 15 year long period of liberalization emerged probably because of some prime movers (Blåvarg & Ingves [1997]):

2) increasing internationalization of the Swedish economy,

3) stronger international influence on the Swedish financial market,

4) international liberalization of the financial markets (mainly in the Nordic countries, Belgium, Spain, France and Italy, which were strictly regulated compared to the rest of Europe)

5) over time, more and more evident problems appeared caused by regulations.

Some of the most important liberalizations are mentioned here:

1978---- the limits on interest rates for bank accounts disappeared.

1980---- foreigners allowed to buy Swedish shares, no upper interest rate limits on corporations’ bond issuing.

1983---- banks’ bond issuing free, no control of interest rates.

1984---- mortgage institutes’ lending free (regulated next year to hamper the expansion.) 1985---- interest rates on bank lending no longer capped.

1986----bond issuing for insurance companies free.

1989---- foreigners could buy bonds and other securities denominated in Swedish kronor. 1990---- Swedes were allowed to buy shares on international stock markets.

1985 and 1990 ---- currency regulation abolished.

For a more detailed report of the deregulations, see Werin (1993). A study of the Swedish commercial banks for the period 1984 – 1995 and of the total factor productivity index indicates a productivity improvement for commercial banks of about 8 percent in 1987/88 peaking in 1988/89 at about 21 percent. The low point came 1990/91, the beginning of the bank crisis, followed by a strong recovery and another major productivity crises in 1993/94 (Ponary Mlima [1999]).

In the beginning of the 1990s two new changes were implemented which may have contributed to increased competition in the financial sector. Firstly, banks were allowed to acquire shares or equity in an insurance company after obtaining permission from the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority. At the same time, insurance companies were

allowed to acquire shares or equities in enterprises operating in the finance sector. In 1996,

banks got increased opportunities to supply banking services through representative agents and at the same time special non-financial enterprises were allowed to receive deposits from their customers, such as deposits on customer accounts within petrol station and retail chains.

A special objective has been to harmonize Swedish legislation and the regulations to that of European Union (EU). The ambition here is that a finance institution with an authorization in one member country automaticallyshould be allowed to operate within all of the EU.

2.6 Entry and Exits

The legislated restrictions on banking have influenced entry numbers. Sweden’s savings

banks started their operations in the 1820s following Scottish and English examples. The number of savings banks increased during a century with a maximum of 497 savings banks in 1926. From the beginning of the 1930s and during the rest of the century the number of savings banks diminished. During the second half of the century the decline accelerated

because of problems for savings banks to expand their operations, as their form of association

could not attract external capital like the commercial banks were free to (Werin [1993, p.71-72]). But even commercial banks suffered from a lack of resources for supplying the internationally expanding Swedish non-financialcorporations. Because of regulations, bank

mergers were the only way to meet the demand from the growing economy after the war,

both for commercial and savings banks. In 1991 the savings banks had plans to create one joint-stock corporation.

During the period from 1919 to 1986, the number of commercial banks was reduced continuously (see figure 1), from 80 in 1910 to fourteen during the period 1974-83. Between 1920s and 1982 no new commercial bank emerged, and Sveabanken, entering in 1984,

ceased operations in 1991. After a hiatus of 76 years (in 1986), twelve foreign banks were

permitted to enter. A few more entered but during the bank crisis (1991-93) exits took over.

Borttaget:

Borttaget: Borttaget:

Figure 1. Commercial banks in Sweden 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 1875 1882 1889 1896 1903 1910 1917 1924 1931 1938 1945 1952 1959 1966 1973 1980 1987 1994 2001 Source: Statistics Sweden.

As many as 26 commercial banks have entered after 1993, of which eleven are former savings banks and four are insurance companies.

Year of permission Commercial banks

1994 = SkandiaBanken (insurance company), Postgirot Bank, IKANO Banken (IKEA), 1995 = Tryggbanken (insurance company), Stadshypotek Bank (mortgage institute), Savings Bank-Sjuhärad,

1996 = Länsförsäkringar Bank (insurance company), Dexia Kommunbank, Savings Bank-Eskilstuna,

1997 = HSB Bank, GE Capital Bank (General Electric),

1998 = Salus Ansvar Bankaktiebolag (insurance company), Savings Bank –Söderhamn, Savings Bank- Öland,

1999 = Trevise Bank, Savings Bank- Färs & Frosta,

2000 = Savings Banks; Lidköping, Skaraborg and Varberg, respectively.

2001-2002 = COOP, ICA, Nordnet Securities, Resursbanken, Savingsbanks: Tjustbygdens, Vimmerby, respectively.

In 2002 there were 31 Commercial banks, 77 Savings banks and eighteen foreign banks operating in the Swedish market.

2.7 IT –Innovation and Branch Offices

Historically, the structure of the Swedish banking system has been centered on the branch

network. At an early stage, banks competed for deposits by building a dense branch network and an efficient payment system based on account transfers, The huge step in Nordic banking scenewas the introduction of bank giro (bankgiro or/and postgiro).

In the first stage of IT, in the 1950s and 1960s in Sweden, this technology was restricted to the field of payment systems and a few production centers of commercial banks and at clearing centers. This was part of an internal wave of technological development, before 1980, with the focus on central automation, in contrast to the following period of

decentralized automation, from 1980 and onwards. Now the adoption of IT came to comprehend to the counters and local branch offices. Branches started to adopt minicomputer systems and back office terminals.

The next external wave of technical development presented new possibilities for customers to access banking services without direct face-to-face contact with the bank personnel. New distribution forms emerged and an early step in this trend was the introduction in the

mid-1970s of cash dispensers as a separate activity. The Automated Teller Machines of the type

currently in use, providing on-line links to customers´ account data were introduced in the early 1980s. Towards the end of the 1980s, note-dispensing cash machines were complemented with self-service machines, capable of paying bills and printing out bank statements.

During the 1980s the so-called Private Banking Giro was launched and many individuals started to pay their bills by mail instead of over the counter. Tele Banking or Telephone Bill Payment (TBP) was introduced in the beginning of 1990s. TBP allowed customers to pay

Borttaget:

their bills by calling their financial institution and authorizing it to debit their account and transmit funds to the payees specified. A number of transactions could be handled with one single telephone call. Customers could have their account balances reported, they could make transfers between accounts and they were offered the possibility to buy and sell mutual fund units.

It is often said that due to the emergence of the Internet, Swedish banks have been able to reduce the number of branches. Since 1984 the number of independent branches have been reduced to half in its initial number (see figure 4).

But the process started long before the introduction of the Internet and was probably an effect of the heavy investment in IT and technical development within banks in general. The number of branches (commercial, savings and cooperative banks) was 2839 in 1945 and the number increased to 4238 during the 1970s when the cooperative banks were allowed to start branches. After that, the number of branches fell continuously, to 1837 in 2002. Between 1984 and 1994 the rate of decrease in the number of bank branches was 2.8 percent annually. In five years, between 1995 and 2002, the number of branches fell by 30 percent (see figure 2), 4.8 percent annually. The number of conventional bank branches has diminished, but there are many new outlets for banking services emerging, such as food store and petrol station chains.

Borttaget:

Figure 2. Swedish Banks´ Branches and Inhabitants per Branch 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 Source: Statistics Sweden, own calculations.

Number of branches Inhabitants per branch

The number of inhabitants per bank branch has initially decreased. In 1945 the figure was 2 350 and - the number was reduced in the period 1965 to 1975 to around 2000, when the cooperative banks expanded. The branch network has changed character during the 1990´s. In 1990 there were over 2 600 inhabitants per branch and this number doubled until the beginning of 2000s. In 2002 the number had increased to 4 8605.

2.8

Internet Adoption

Since the introduction of the Internet in 1969, it has evolved from being a domain solely of the academic to becoming a mainstream channel for communication. Internet services growth in earnest started in the mid-1990s, but it did not really take off until 1998 and 1999 when

home computers were widely diffused to Swedish households. At that time, sufficient

infrastructure existed and broad groups of individuals mastered resources allowing them to utilize a number of Internetcommunication applications offered. The share of adults using the Internet from any location is increasing rapidly and in 2000 76 percent used the Internet in Sweden, by far the highest share in the OECD countries (OECD [2002, p.46]). One reason

for the high Internet and PC penetration is that corporations are given tax credits if they provide their employees with PC´s. Increased competition between telecommunications operators has driven down the charges for using the Internet, and in May 2002 Sweden had, after Iceland, the second lowest price of leased lines in the OECD (OECD [2002, p.57]). The high Internet penetration is a key factor when explaining the rapid rise of e-banking in Sweden. Eurostat estimated that in the spring of 2000, 35 percent of the EU population had a computer at home. According to an opinion poll company, some 50 percent of the Swedish population between 21 and 79 had connections to the Internet in the year 2000 (Finansinspektionen [2000, p. 9]. Sweden had at that time a high level of technological readiness – a prerequisite for the success of Internet banking. Both Sweden and Finland were for example among the world’s fastest adopters of mobile telephones.

According to the Eurobarometer survey carried out in February 2001, 36 percent of the EU population (fifteen years and older) or 114 million persons used the Internet.

Figure 3. Internet users per 100 inhabitants 2000

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 Belg ien Denm ark Ger ma ny Fran ce Irela nd Italy Luxe mbu rg Net herla nds Austr ia FinlandSwed en Unite d Kin gdomIcela nd Nor way United State s Japa n Source: Eurostat 2002.

From figure 3 it is obvious that in the year 2000 Iceland was ahead of Sweden in Internet user frequency with the US close behind. And Norway, Finland and the Netherlands displayed high figures as well.

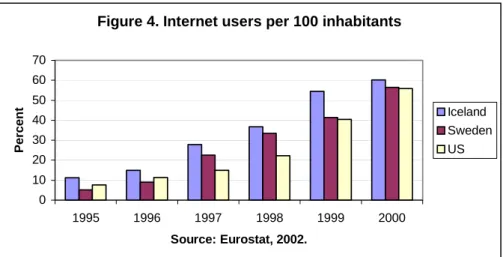

From figure 4 we can see that in the mid 90´s, Iceland’s Internet adoption rate was ahead of

that in the US in and that in Sweden the adoption rate increased rapidly after 1996.

Figure 4. Internet users per 100 inhabitants

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Source: Eurostat, 2002. Percent Iceland Sweden US

2.9

Internet in Banking

When first introduced, Internet banking was mainly used as an information presentation medium in which banks, like other enterprises, presented and marketed their products and services on their Web sites. When secure electronic transaction and asynchronous technologies were developed, more banks came forward to use Internet banking both for transactions and as an information medium. Now, registered bank users may all by

themselves perform basic banking transactions such as paying bills, transferring funds,