University of Stockholm 106 91 Stockholm Phone: 00468–16 20 00 www.su.se

Egg laying preferences of two

Littorina species on co-occurring

Fucus and Ascophyllum thalli

Marit Hichens-Bergström

Supervisor: Lena Kautsky

Magister Degree project, 30 hp

The Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant

Sciences

3

Egg laying preferences of two Littorina species on

co-occurring Fucus and Ascophyllum thalli

Abstract

In the study the preference of two Littorina species, i.e. Littorina obtusata and Littorina fabalis was investigated experimentally and in the field on which of the two fucoid species, Fucus vesiculosus or Ascophyllum nodosum they preferred to place their egg aggregations.

The hypothesis tested was that L. obtusata and L. fabalis both prefer F.

vesiculosus as substrate for spawning over A. nodosum and that L. obtusata

move from their main grazing habitat, i.e. A. nodosum to F. vesiculosus before laying their egg sacs.

The experiment was supported by a field study where the numbers of the two Littorina species, both adults and juveniles, were counted on F.

vesiculosus and A. nodosum thalli collected in the field.

The results showed that both L. obtusata and L. fabalis preferred F.

vesiculosus over A. nodosum as substrate for placing their egg sacs and that

juveniles transfer to their preferred food source after hatching. This is the first report on the ability of adult L. obtusata to actively select favorable substrate for juvenile snails, by avoiding placing their egg sacs on

unfavorable surfaces as A. nodosum.

Both L. fabalis and L. obtusata placed their egg sacs on older parts of the thalli, mostly below the vesicles.

The number of eggs sac was higher for L. obtusata when both A. nodosum and F. vesiculosus where available, but higher for L. fabalis when there were only F. vesiculosus in the jar.

This indicates that more of the preferred nutrition would provide for more eggs in each sac, since the adults have more energy to produce more eggs. The number of snails counted in the field shows the dynamics of population during the summer. There was an obvious shift with more juveniles of both

Littorina species on F. vesiculosus in the beginning of July, changing to most

of the juveniles occurring on A. nodosum at the end of the month. The importance of conducting the study during the hatching season to monitor the movements of the snails between preferred habitat for adult grazing, spawning and juvenile feeding is evident.

Keywords

4

Sammanfattning

I studien undersöktes två Littorina arter, dvs. Littorina obtusata och Littorina fabalis, experimentellt och i fält om vilken av de två fucoid arterna, Fucus vesiculosus eller

Ascophyllum nodosum de föredrog att placera sina ägg samlingar på.

Hypotesen som testades var att L. obtusata och L. fabalis båda föredrar F. vesiculosus som substrat för sina äggsamlingar framför A. nodosum och att L. obtusata flyttar från deras huvudsakliga habitat, dvs. från A. nodosum till F. vesiculosus innan de lägger sina ägg. Experimentet fick stöd av en fältstudie där antalet snäckor av de två Littorina arterna, både adulta och juvenila, räknades på F. vesiculosus och A. nodosum thalli i såväl fält som på insamlade thalli i laboratorium.

Resultaten visade att både L. obtusata och L. fabalis föredrar F. vesiculosus framför A.

nodosum som substrat för att placera sina ägg samlingar och att juveniler flyttar över till

den tångart de föredrar efter kläckning . Detta är den första rapporten om möjligheten för adulta L. obtusata att aktivt välja ett mer gynnsamt substrat för juvenila snäckor, genom att undvika att placera sina ägg på ytor som A. nodosum.

Både L. fabalis och L. obtusata placerade sina ägg samlingar på äldre delar av thallus, mestadels nedanför flytblåsorna.

Antalet ägg per samling var högre för L. obtusata när både A. nodosum och F. vesiculosus var tillgängliga, men högre för L. fabalis när det fanns bara F. vesiculosus i burken.

Detta tyder på att mer av den Fucoid art som adulta L. obtusata eller L. fabalis föredrar, skulle kunna ge mer energi till de adulta så att de kan producera fler ägg.

Antalet individer av Littorina räknade på F. vesiculosus och A. nodosum i fält visar på en stor dynamik i populationerna under sommaren. Med tiden minskade antalet vuxna snäckor av båda arterna, troligen beroende på att de gamla individerna dog efter

förökningen. Det var en tydlig förflyttning av mer juveniler av båda Littorina arterna på F.

vesiculosus i början av juli, direkt efter kläckningen, till fler unga snäckor av L. fabalis på A. nodosum i slutet av månaden. Vikten av att genomföra studien vid olika tider under

säsongen för att övervaka förflyttningar av snäckorna mellan deras habitat för adulta, äggläggning och juveniler, är uppenbar.

5

Contents

Abstract ... 3 Introduction ... 6 Study species ... 6 Aims ... 10Material and methods ... 11

Egg laying preference ... 11

Distribution in the field ... 11

Results ... 13

Egg laying preference ... 13

Distribution in the field ... 16

Discussion ... 18

References ... 21

6

Introduction

The Swedish west coast has an interesting flora and fauna. This has been studied from many different angles, highlighting ecology, life cycles and their interaction with environmental factors affecting the composition of species and e.g. their reproductive success.

In the shallow intertidal zone of many coastal temperate areas a set of fucoids are often found together with different grazing species of gastropods, gammarids and isopods. The tidal zone along the Swedish west coast is narrow, only about 0.2 meters, although periods of high and low water pressure may affect the water level strongly. This results in extended periods of desiccation during low water, affecting the zonation pattern of fucoids such as Fucus spiralis, Fucus serratus, Fucus vesiculosus, Ascophyllum nodosum (Watson and Norton, 1987) and four different Littorina species (Janson, 1981).

The only Ascophyllum species, i.e. A. nodosum occurs on moderately exposed shores mixed with F. vesiculosus at about 0.5-1 meters depth at the Swedish west-coast.

Ascophyllum nodosum does not grow at lower salinities south of Öresund (Wikström,

2004).

Study species

There are four commonly found Littorina species on these rocky shores along the Swedish coast of Skagerrak and Kattegat, i.e. Littorina littorea (L.), Littorina saxatilis (Olivi),

Littorina obtusata (L.) and Littorina fabalis (Turton, 1885) (previously known as L. mariae

(Sacci and Rastelli, 1966), (Jansson, 1981).

All four of the Littorina species live in the intertidal zone, commonly dominated by different Fucus species and Ascophyllum. Littorina fabalis and L. obtusata are herbivores and feed both on different fucoids and on their epiphytes by the small teeth on the radula. Littorina fabalis occurs on the lower part of the shore and has been found on and prefer to graze on F. vesiculosus or F. serratus (Watson and Norton, 1987, Williams, 1990, 1994) while L. obtusata mainly prefer grazing A. nodosum (Norton, 1990) but has also been found on F. vesiculosus and F. spiralis higher up on the shore. Barker and Chapman (1990) showed that L. obtusata prefer F. vesiculosus out of four Fucus species, but the study did not include A. nodosum.

Littorina obtusata is one of few grazers capable of eating A. nodosum despite the fact that

this plant has a very high content of repellent chemicals, e.g. phlorotannins (Williams, 1990; Pavia, 1999; Toth, 2000, 2005), compared to F. vesiculosus.

7

High densities of L. obtusata can even reduce the biomass of F. vesiculosus, as shown by Kozminsky (2013) suggesting that this species in some cases not only consume and grazes on Ascophyllum but also on F. vesiculosus.

The distribution and zonation on the shoreline of L. fabalis and L. obtusata, further differs on more exposed shores, where the abiotic factors have a bigger impact on the snails. Studies made in England where the tidal range is larger than in Sweden, have shown that

L. obtusata crawls back into the algae when it is exposed to air. Littorina fabalis remains

active grazing when submerged, but is then more stressed by desiccation and strong light during low water periods (Williams, 1990).

Figure 1. A typical larger darker shell of Littorina obtusata (left) and smaller yellow shell of L. fabalis (right) collected at Saltö, near Strömstad in June 2013.

Of the two species L. obtusata has been found to be better able to cope with high/low temperatures, desiccation and light (Williams, 1990) than L. fabalis, explaining why L.

fabalis is found only on moderately exposed shores, while L. obtusata can relocate

between more preferable habitats when these abiotic factors affects the snails. Each of the Littorina species have developed different strategies in feeding and reproduction related to their habitat and in which part of the algal zonation they can survive. For example, high wave-exposure and high predation by crabs has been shown to have an impact on which ecotypes that occur at a site and both convergent and parallel evolution within Littorina species have been suggested by Johannesson (2003).

8

According to Hintz Saltin, (2013 and references therein) L. fabalis and L. obtusata where two separate species about 1, 3 million years ago. However until genetic analysis revealed this separation, they have been treated as one and the same species in many studies, which make comparisons with older investigations difficult.

Several studies have been presented about these two Littorina species, their morphology, habitat and feeding preferences, mating choice and even tenacity of attachment

summarized in the review by Davies and Case, 1997.

The main morphological differences between the two species are size and body colour, where L. obtusata is bigger, often with a black body and olive-green to dark/light brown shell, while L. fabalis is smaller, has a yellow body and yellow to light brown shell (Fig 1). Also the age of the two species differs. Littorina obtusata may live for 3-4 years, while L.

fabalis only lives for 1-2 years. (Williams, 1990)

Littorina fabalis and L. obtusata place their long and flattened egg sacs containing several

hundreds of eggs in the first part of the summer, from May to the middle of July

(Williams, 1990) on fucoid fronds. The egg sacs are transparent or white in the beginning but turn darker when the juveniles develop inside the jelly-like sac. Juveniles are about 0.5 mm in size when they hatch (Janson, 1981).

Further, a size difference has been reported with smaller L. obtusata on wave-exposed shores and larger shell sizes of L. fabalis (Williams, 1990). Thus, it is harder to distinguish between these two species at more wave-exposed sites compared to sheltered sites. Contrary, at moderately exposed areas their morphology, i.e. shell size tends to divert and makes it easier to identify the different species. For example L. fabalis has an ecotype at moderately exposed sites that is smaller than on exposed area according to Johannesson (2002).This would motivate the use of moderately exposed sites in this study performed at the Swedish west coast.

Along the Swedish west coast of Skagerrak a set of different Fucus species together with

Ascophyllum are found in the shallow intertidal area. The salinity varies between 30-20

psu. Although the natural tide is almost nonexistent, differing only about 20 cm, large water level variations occur due to high and low air pressure, which may create changes up to 1 meter or more. During winter the shallowest parts of the shore may be covered by ice whilst in the spring during high air pressure the fucoids may be dried out for weeks. These factors structure the zonation of the fucoids. Fucus vesiculosus is found mixed with

A. nodosum at moderately exposed sites (Watson and Norton, 1987, Wikström, 2004).

The different fucoids further differ in the amount of epiphytes and type of epiphytes, with less epiphytes growing on A. nodosum (Williams, 1990) compared to the Fucus species. Together with differences in anti-herbivorous substances, e.g. phlorotannins, the amount of small epiphytes may have an impact on juvenile Littorina which are not able to graze the thallus surface of fucoids.

9

At moderately exposed sites the two Littorina species thrive with their preferred food items, i.e. F. vesiculosus with a rich epiphyte flora and A. nodosum, with less epiphyte but preferred as food by the adult L. obtusata.

To my knowledge no studies have earlier investigated where L. fabalis and L. obtusata could place their egg sacs. They might, as an assumption, have a preference for different

Fucoid species, when it comes to living as adults and where the small newly hatched snails

10

Aims

The aim of this study is to compare feeding preference of adult L. fabalis and L. obtusata and to establish their propensity to select between F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum when placing their egg sacs.

The following questions were addressed:

1. On which species do L. fabalis and L. obtusata prefer to place their egg sacs, i.e. on

F. vesiculosus or A. nodosum thalli?

2. Where on the thalli of F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum do L. fabalis and L. obtusata place their egg sacs?

3. Does the natural distribution pattern of L. fabalis and L. obtusata in the field correlate with their preferences of seaweed substrate for spawning?

To do this, the distribution and numbers of adult and juveniles were studied in the field on

F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum in mixed stands, with the aim to document the natural

distribution patterns of L. fabalis and L. obtusata. Further, a set of experiment were performed.

The field and laboratory work was performed in the summer of 2013 at The Sven Lovén Centre for Marine Sciences, Tjärnö, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

11

Material and methods

Egg laying preference

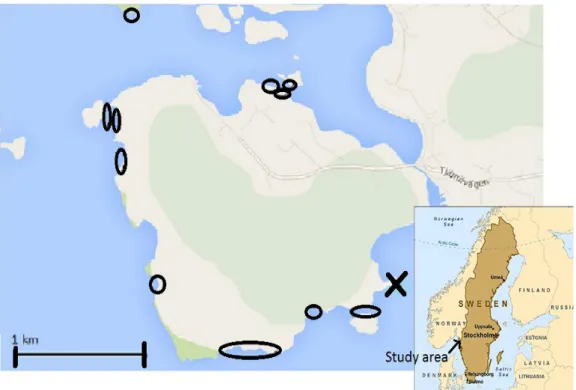

Around The Sven Lovén Centre for Marine Sciences, Tjärnö, several areas occur where mixed stands of F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum are found. These moderately exposed sites were used for the field investigation and collection of material for the experiment.

From a site south east on Saltö, outside Tjärnö (marked with X in fig. 2) 200 of adult L.

obtusata and L. fabalis were collected mainly from F. vesiculosus thalli at the end of June,

2013.

A series of 8 x 6 jars were set up. In each jar 5 snails from either L. obtusata or L. fabalis were placed. They were selected randomly and not determined to sex. The uppermost 10 cm of fronds, totally about 4 g WW tissue, were cut from F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum, respectively and carefully cleaned from organisms such as other snails, epiphytes and small animals.

The setup consisted of three different treatments, one treatment containing a choice between F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum, and two treatments with either F. vesiculosus or

A. nodosum.

The experiment was placed outdoors in running seawater to maintain a natural

temperature range. Every 4-5th day the pieces of seaweed were checked for egg sacs and

old fronds without egg sacs were replaced by new fresh pieces of fronds.

The experiment was run for 3 weeks (25 June – 17 July). At the end of the experiment the egg sacs were counted and photographed. Also where the egg sacs were placed, i.e. on

Fucus or Ascophyllum fronds, on the inner wall/ lid of the jar was registered.

Finally the number of eggs per sac was counted and the placement of the egg sacs on the fronds was noted, i.e. above or below the floating bladder.

Distribution in the field

The number of L. fabalis and L. obtusata were counted on thalli of F. vesiculosus and A.

nodosum respectively at a set of sites on Saltö and small islets nearby, east of Tjärnö,

situated on the west coast of Sweden (Fig. 2).

Mixed stands of F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum at a depth of 0.7-1 m were present in all sites.

The field inventory was carried out at the 27-28 of June and the 7-17 of July and a total of 29 F. vesiculosus and 28 A. nodosum were studied.

Adults and juveniles were distinguished by the size of the snails, i.e. L. obtusata adults ranged from 15-17 mm and L. fabalis between 9-12 mm.

Specimens smaller than 0.5 mm were excluded from the analysis, since they were not possible to determine to species.

12

Figure 2. Map of the island Saltö, west of Tjärnö were Sven Lovén Centre for Marine Sciences is situated: Inventory June -July 2013: X; collecting site for L. obtusata and L. fabalis. Circles; Field inventory of snails.

Two field samplings of whole thalli of F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum were performed by putting a net over single thalli and cutting it off at the holdfast, one on the 27th of June

where 7 F. vesiculosus and 8 A. nodosum thalli were examined and the second one

between the 20-21st of July, where 5 thalli of F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum were analyzed

respectively. The thalli were brought back to the laboratory and the number of the two

Littorina species, i.e. L. obtusata and L. fabalis respectively, i.e. adults and juveniles were

13

Results

Egg laying preference

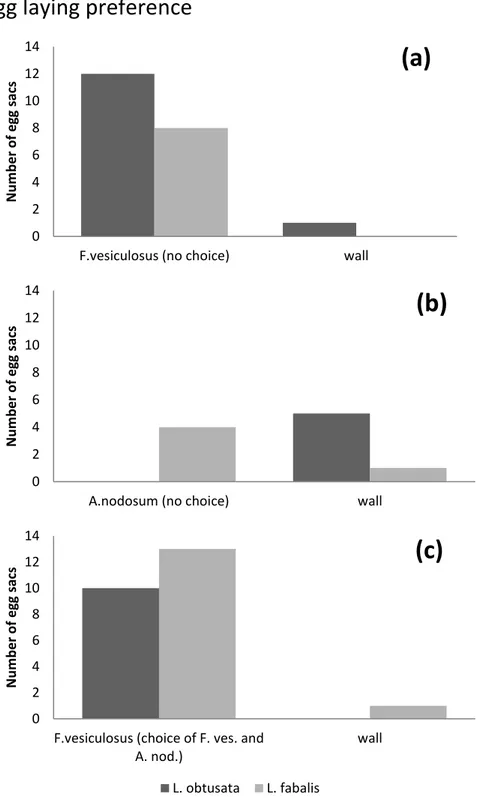

Figure 3. Total number of egg sacs and where L. obtusata and L. fabalis preferred to place the egg sacs on the fronds or on the wall of the jar; (a), only Fucus vesiculosus in the jar(b), only Ascophyllum nodosum in the jar and (c) a choice between F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum (n=8).

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

F.vesiculosus (no choice) wall

N u m b e r o f e gg sacs

(a)

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14A.nodosum (no choice) wall

N u m b e r o f e gg sacs

(b)

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14F.vesiculosus (choice of F. ves. and A. nod.) wall N u m b e r o f e gg sacs

(c)

L. obtusata L. fabalis14

In Fig. 3 the result of the choice experiment run for 3 weeks (25 June – 17 July 2013) are presented. In the jars only containing fronds of F. vesiculosus both L. obtusata and L.

fabalis lay their egg sacs on F. vesiculosus fronds (Fig. 3a).

With only A. nodosum in the jar, they instead placed their egg sacs on the wall or on the lid of the jar (Fig 3b). Littorina fabalis placed very few i.e. 4 egg sacs on the algal frond, while L. obtusata avoided the A. nodosum fronds and only used the wall of the jar. Also, in the choice experiment both Littorina species showed a preference towards F.

vesiculosus as a substrate over Ascophyllum for placing their egg sacs on (Fig. 3c). Both L. obtusata and L. fabalis placed all of their egg sacs on F. vesiculosus except one egg sac on

the wall. The number of egg sacs was similar to the number in jars with only F. vesiculosus (Fig. 3b).

Finally, in the jars with only A. nodosum, the number of egg sacs was much lower.

In total L. obtusata produced 28 egg sacs and L. fabalis 27 egg sacs during the experiment.

Figure 4. The typical placement of Littorina obtusata egg sacs on Fucus vesiculosus to the left and L. fabalis egg sacs on Ascophyllum nodosum to the right. The egg sacs are marked with a red circle. Many of the fronds were also heavily grazed as shown in the photo.

Table 1. Number of egg sacs and where on both F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum (summarized) L. obtusata and L. fabalis placed them. Number of egg sacs produced by each of the Littorina species (No).

L. obtusata L. fabalis

No No

High up on frond 4 5 In the middle, no vesicles 0 8 Above vesicles 3 4 Below vesicles 15 9

On the wall 6 1

15

The egg sacs were mainly found below vesicles on older part of the plants (Fig 4) and rarely on the younger tips of the thalli.

The placement by L. fabalis was similar to L. obtusata and found below vesicles on older part of the F. vesiculosus, while egg sacs on A. nodosum where placed both above and below the vesicle (Table 1).

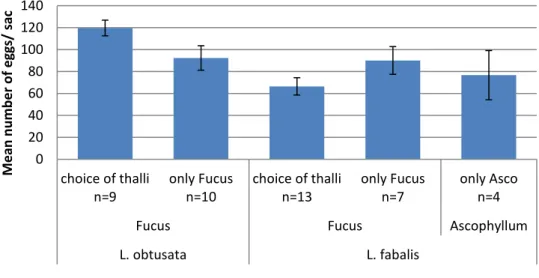

Figure 5. Mean number of eggs per egg sac placed by L. obtusata and L. fabalis, during the 22 days the experiment was running, with a choice between F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum. Error bars show standard error (s.e.).

Littorina obtusata egg sacs contained 92. 4 ± 11.5 eggs per sac, while in the choice

experiment the amount of eggs was slightly higher, i.e. 119.7 ± 7.2 eggs/sac.

Compared to L. obtusata, L. fabalis had overall fewer eggs per sac. In the experiment with only F. vesiculosus fronds in the jar L. fabalis produced 90.1 ± 12.6 and in the choice experiment even lower numbers i.e. 66.5 ± 7.9 eggs/sac on the F. vesiculosus fronds. The egg sacs placed on A. nodosum contained 76.7 ± 22.4 eggs/sac (Fig. 5)

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 choice of thalli n=9 only Fucus n=10 choice of thalli n=13 only Fucus n=7 only Asco n=4

Fucus Fucus Ascophyllum

L. obtusata L. fabalis M e an n u m b e r o f e gg s/ sac

16

Distribution in the field

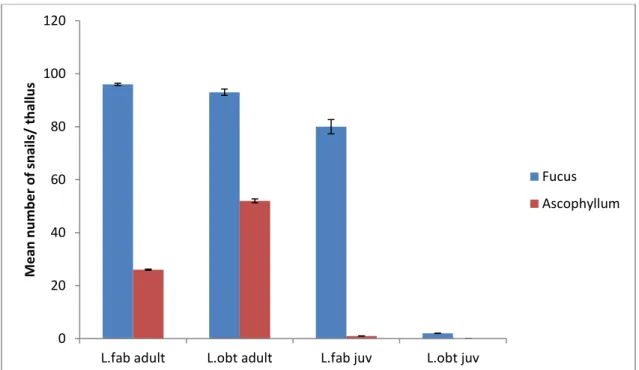

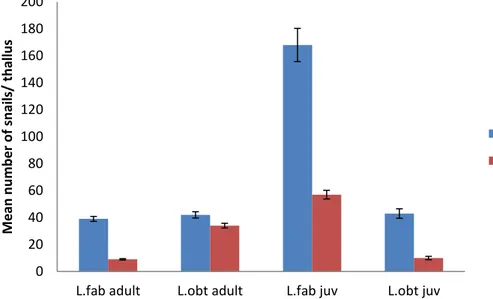

In the field investigations carried through, the highest number of adult L. fabalis and L.

obtusata were recorded on F. vesiculosus thalli compared to A. nodosum. The number of

juveniles of L. fabalis was significantly higher on F. vesiculosus than on A. nodosum and almost no L. obtusata juveniles were found in the investigation performed at 11 sites (Fig. 2), in the end of June 2013. (Fig. 6)

Figure 6. Shows the mean value of snails per thallus on the material counted in the field from 27th June to

17th July, 2013. Error bars show standard error (s.e.).Fucus; n=29 and Ascophyllum; n= 28

The laboratory counting showed that adult snails are found on both Fucus and

Ascophyllum, but some more individuals are found on Fucus. The juveniles are found

mainly on Fucus in the middle of July (Fig. 7).

In the later count there were almost no adults at all (Fig. 8.) There was a much higher amount of juveniles than adults in counts made in the laboratory, compared to the investigation made in the field (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

The counting made in the end of July also shows a higher number of juveniles of L. fabalis than L. obtusata. Most of them are found on F. vesiculosus, but also on A. nodosum (Fig. 8). 0 20 40 60 80 100 120

L.fab adult L.obt adult L.fab juv L.obt juv

M e an n u m b e r o f sn ai ls/ th al lu s Fucus Ascophyllum

17 Figure 7. Shows the mean value of snails per thallus on the material collected and counted in the laboratory in the beginning of July, 2013. Error bars show standard error (s.e.) Fucus n=7 and

Ascophyllum n= 8

Figure 8. Shows the mean value of snails per thallus on the material collected and counted in the laboratory in the end of July, 2013. Error bars show standard error (s.e.) n=5

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200

L.fab adult L.obt adult L.fab juv L.obt juv

M e an n u m b e r o f sn ai ls/ th al lu s Fucus Ascophyllum 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

L.fab adult L.obt adult L.fab juv L.obt juv

M e an n u m b e r o f sn ai ls/ th al lu s Fucus Ascophyllum

18

Discussion

The adult specimens of two species i.e. L. fabalis and L. obtusata were shown to prefer F.

vesiculosus over A. nodosum in the choice experiment, when selecting where to place

their egg sacs. Despite that A. nodosum is a favorite food source for adult L. obtusata, the snails were shown to have the ability to choose other substrates for placing their egg sacs on. An obvious difference between the two species was that while L. fabalis was found to place a few egg sacs on A. nodosum, L. obtusata did not lay any egg sacs at all on

Ascophyllum. In the experiment with only Ascophyllum fronds in the jar, L. obtusata

preferred to place the egg sacs on the wall or on the lid of the jar, not on the fronds of A.

nodosum, the adult snails’ favorite food. Earlier studies by Williams (1990), has shown

that the ability of L. obtusata to feed on A. nodosum and penetrate its tougher thalli could be due to the structure of their radula, with an outer tooth with several indistinct, angular cusps (Watson and Norton, 1987), compared to L. fabalis which radula only can penetrate

F. vesiculosus´ softer surface.

Littorina obtusata was found being able to make holes and excavations on the thallus of A. nodosum, similar to the grazing marks observed on F. vesiculosus.

Also L. fabalis preferred to lay their egg sacs on F. vesiculosus. According to Watson and Norton (1987), juveniles of L. fabalis can easily feed on the epiphytic microflora of F.

vesiculosus that also the adults prefer.

Although A. nodosum is possible to consume for adult L. obtusata, as indicated by the grazing marks, the young newly hatched snails need to feed on microscopic epiphytes that are comparatively few on A. nodosum (Williams, 1990), and more abundant on F.

vesiculosus. Thus, it may be more optimal both for L. obtusata and for L. fabalis to lay

their egg sacs on F. vesiculosus instead of A. nodosum, so that the juvenile snails can take advantage of the rich epiphytic microflora. The radula of juvenile snails can only graze on microalgae, and not on the tougher fucoid thalli such as A. nodosum (Watson and Norton, 1987). This is the first report on the ability of adult L. obtusata to actively select a

favorable substrate for juvenile snails, by actively avoiding placing their egg sacs on unfavorable surfaces as A. nodosum. When there is no choice of fucoid in the jar and only

A. nodosum present, L. obtusata placed their egg sacs on the wall or on the lid of the jar.

When the juvenile snails grow older, larger and develop the teeth on the radula, it makes it possible for them to feed on the tissue of F. vesiculosus and for L. obtusata even on A.

nodosum (Williams, 1992) suggested that the feeding ability of L. obtusata on A. nodosum

may reduce the completion for food and contribute to the maintenance of separate zones of the two Littorina species, i.e. that the occurrence on different fucoids has a selective value for L. obtusata and L. fabalis.

The high amount of phlorotannins in A. nodosum and the grazing of L. obtusata have been studied earlier by Toth et al. (2005). They showed that L. obtusata feed on A. nodosum

19

despite the high amounts of phlorotannins, and especially the apical shoots which contain less phlorotannins than the basal parts of the thalli.

Further the number of viable L. obtusata eggs was lower when snails had been grazing on parts of the thallus containing higher levels of phlorotannins (Toth et al., 2005). This may partly contribute and explain the results found in this study that L. obtusata preferred to lay their egg sacs on F. vesiculosus in the choice experiment.

The results further shows that both Littorina species preferred to place the egg sacs on the lower part of the fronds, mainly below the vesicles. This is in accordance with

observations from the field. This may be due to that younger tissue excretes mucus which may inhibit the establishment of the egg sacs. At the same time the older parts of the fronds have more microscopic epiphytic flora and may be easier to attach to.

Further, in the field, the egg sacs placed below the floating bladders are probably more sheltered from waves and thereby less at risk of falling off.

Thalli, especially A. nodosum thalli, are also broader further down on the shoot, which may make it easier for the snail to stay attach to the surface (Davies and Case, 1998), and have time to lay their egg sacs.

Littorina obtusata was shown to have on average more eggs per sac compared to L. fabalis. In the choice experiment with both F. vesiculosus and A. nodosum in the jars, L. obtusata egg sacs contained the highest number of eggs (Fig. 5). The result suggests that

with more food available for the adult snail, they may be able to produce more eggs per sac. In an earlier study, Toth and Pavia (2005) stated that fecundity was lower when adult

L. obtusata fed on A. nodosum with higher content of phlorotannins. Since F. vesiculosus

fronds contains less phlorotannins this may explain the advantage to use F. vesiculosus as substrate for spawning instead of A. nodosum, since it would be possible to produce more eggs in each sac if the adult has more food resources.

Littorina fabalis egg sacs contained more eggs when there were only Fucus fronds in the

jar, suggesting that the adults, similar to L. obtusata when more food is available can use the energy to produce more eggs per sac.

The number of snails found per thallus on the material counted in the field from June to July, 2013 was higher on F. vesiculosus compared to A. nodosum, by both adult L. fabalis and L. obtusata.

Almost no juveniles of L. obtusata were found, but about 80 juvenile L. fabalis occurred already at the end of June on F. vesiculosus in the field. The data suggest that a high mortality occurs after reproduction in the more short lived L. fabalis, which only lives for 1-2 years as well as for the longer lived L. obtusata. The amount of adult L. obtusata does not decrease as rapidly as L. fabalis (Fig. 5 and 6).

Comparing the results from the beginning of July to the end of July the number of hatched juvenile snails increased. There was also an obvious shift with more juveniles of both

Littorina species on F. vesiculosus in the beginning of July, changing to most of the

20

This result with the juveniles mainly found on F. vesiculosus on the middle of July, i.e. when the hatching occurs and then transferring to Ascophyllum later in the summer, supports the results from the choice experiment.

Juvenile snails have also been observed inside the bladders of A. nodosum (Pavia, 1999), where the phlorotannins-rich outer cell-layers are avoided, suggesting that small juvenile snails of L. obtusata when they have moved to A. nodosum can feed on surfaces earlier grazed by adult snails or inside bladders.

Further studies are needed to find out in detail when and at what sizes after hatching on

F. vesiculosus the juvenile snails move over to A. nodosum i.e. and at what size their

radula has developed enough to graze on the tissue of fucoid species and not just the microscopic epiphytes.

21

References

Barker KM, Chapman ARO (1990). Feeding preferences of periwinkles among four species of Fucus. Marine Biology 1990 Volume 106; 1, pp 113-118

Beer, S. and Kautsky, L. 1992. The recovery of net photosynthesis during rehydration of three Fucus species from the Swedish North Sea coast. Botanica Marina 35:487-491. Davies Mark S., Case, C.M.(1997) Tenacity of attachment in two species of Littorinid,

Littorina littorea (L.) and Littorina obtusata (L.). Ecology Centre, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, SRI 3SD, UK

Goodwin, J and Fish, J. D. (1977) Inter- and intraspecific variation in Littorina obtusata and

L. mariae. Department of Zoology, University College of Wales, Journal of molluscan

studies [0260-1230] yr: 1977 vol: 43 iss: 3 pg:241 -254

Hintz Saltin, Sara (2013). Mate choice and its evolutionary consequences in intertidal snails (Littorina spp.). Gothenburg University

Jansson, K (1981). Strandsnäckors rörliga taxonomi. Fauna och flora 76:273-276

Johannesson, K. Evolution in Littorina: ecology matters, Journal of Sea Research, Volume 49, Issue 2, March 2003, Pages 107-117

Kautsky, L. (2001) Svensk algflora

Kozminsky, E.V., (2013) Effects of environmental and biotic factors of the fluctuations of abundance of Littorina obtusata (Gastropoda: Littorinidae). Hydrobiologia, 706: 81-90. Norton, T.A., Hawkins, S.J., Manley, N.L., Williams, G.A., Watson; D.C. (1990). Scraping a living: a review of littorinid grazing. Hydrobiologia 193: 117-138

Pavia, Henrik (1999). Patterns, causes and consequences of variation in the phlorotannins content of the brown alga Ascophyllum nodosum. Dissertation, Department of Marine botany, Gothenburg University.

Pavia, Henrik, Toth, Gunilla, (2000) Inducible chemical resistance to herbivory in the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum. Ecology, 81, pp. 3212-3225, Ecological society of America

Toth, G. Pavia, H. (2000). Water-borne cues induce chemical defense en a macro alga (Ascophyllum nodosum). PNAS, dec. 2000, vol. 97, nr 26.

22

Toth, G., Langhamer, O., Pavia, H. (2005) Inducible and constitutive defenses of valuable seaweed tissues: consequences for herbivore fitness. Ecological society of America, Ecology, 86(3), pp.612-618

Watson, David C., Norton, Trevor A., (1987). The habitat and feeding preferences of

Littorina obtusata and L. mariae Sacchi et Rastelli. Journal of experimental marine biology

and ecology, 112:1, 61-72

Williams, Gray A. (1990) The comparative ecology of the flat periwinkles, Littorina

obtusata (L.) and L. mariae Sacci et Rastelli. Field studies7, 469-482, Zoology department,

University of Bristol

Williams, Gray A. (1992) The effect of predation on the life histories of Littorina obtusata and Littorina mariae. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 72 / Issue 02 / May 1992, pp 403 – 416

Williams, Gray A. (1994) Variation in populations of Littorina obtusata and L. mariae (Gastropoda) in the Severn Estuary. Biological Journal of the Linnaean society; 51: 189-198 Wikström, S. A. (2004). Marine Seaweed Invasions: the Ecology of Introduced Fucus

23

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Lena and Nils Kautsky for giving me the opportunity to discover the marine world at Tjärnö. Thank you Lena for all the work with this study!

Ellen Schagerström has been a fantastic co-tutor and given me a chance to enter the world of statistics.

Michael Tedengren assisted me in finding this project and Kerstin Johannesson inspired and helped me with all the activity concerning Littorina going on at Tjärnö!

Thanks to Birgitta Åkerman who has been a true supporter when it comes to continuing studying biology for decades!