Urban Leftovers: Identifying and

Harnessing their potential for the

Agenda 2030 in Malmö

Divya Kasarabada

Main field of study - Urban Studies

Degree of Master of Sciences (120 credits) in Urban Studies (Two-Year) Master Thesis, 30 credits

Spring semester 2020 Supervisor: Elnaz Sarkheyli

Abstract

The planning of cities and transformation of social, political and economic structures have resulted in space of three types (figural space, open space and derived space). Derived spaces or leftover spaces are born as a by-product of the design of figural spaces and are commonly unused roof tops, or space under a flyover that is vacant, or spaces behind a building that are unattractive or a parking lot that is empty on weekends. Their nature, appearance and qualities vary from context to context. Some cities are recognizing the untapped potential of these spaces and are working towards revitalizing them. The narrative of a city can change when these spaces are incorporated into the urban fabric of the city. Malmö, as a city with so much industrial history and one in the forefront of sustainable development, is also home to many leftover spaces. These spaces could be a test ground for working towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Leftover spaces are also already being recognized for different needs such as temporary uses, artworks, tactical urbanism, environmental design. This thesis maps the types of leftover spaces in the city using different methods and suggests a typology of spaces for the city. Case study examples from Scandinavia and strategies that were inferred from them form the basis of linking these spaces to the SDGs. These leftover spaces are not ‘seen’ by the city and pose various challenges such as ownership, funding and the building traditions of Sweden. This discussion will put Malmö, Sweden and broadly Scandinavia among the other studies done on the realm of leftover spaces.

Keywords: Open spaces, leftover spaces, Malmö, Temporary use, Middle out Approach , Sustainable Development Goals, Agenda 2030

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor Elnaz Sarkheyli for guiding me through the whole process and bearing with me through all my ups and downs. Thank you for giving me all your feedback even in the time when it was not expected.

I would like to thank Karin Grundström and Fredrik Björk for their valuable feedback on Malmö and proceedings in the city.

I would also like to thank Maria Olsbäck from the Municipality of Malmö for her constant support and helping me find an amazing network of professionals working in the city.

I would also like to thank Jenny Grettve and Daniel Möller for being my unofficial mentors in my journey.

I would also like to mention my friend Mihai Baicu who was always enthusiastic to discuss the challenges in my thesis. I would also like to thank Kevalin Saksiamkul for her guidance in the practicalities of the thesis. I would also like to Teerapong Sanglarpchorenkit who shares a passion for urban issues as well.

I also want to thank all my questionnaire participants for taking the time to share insights on the city. A big thanks to all my interviewees, for taking the time to share professional insights and ideas.

I must also thank all my friends who I live with, for being so understanding through my process and all my thesis mates for being a big source of motivation. A big thanks to Ridwan, Karen, Bibiana and Nneka.

Last but not the least, I would also like to thank my family, who have been so supportive in my journey. A huge thanks to my mother and sister Priyanka Ivatury for being my unofficial co supervisors.

I have had so much help in these past few months, and it would not have been possible without all these wonderful people in my life who have wanted nothing but the best for me. A heartfelt thanks to all of them.

Table of Contents

Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Tables 6 List of Figures 6 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Research Problem 2 1.3 Aim of Study 4 1.4 Research Questions 5 1.5 Previous Research 5 1.6 Disposition 62. Methodology and Methods 8

2.1 Methodology 8

2.2 Research Approach 8

2.2.1 Case study approach 8

2.3 Research Design 9

2.3.1. Preliminary Mapping and Photo Mapping 9

2.3.2 Semi-structured Interviews 11

2.3.3 Questionnaire and participant mapping 12

2.4 Research Analysis 13

2.4.1 Thematic Analysis 13

3. Theoretical Background 14

3.1 Space 14

3.1.1 Derived Space 14

3.1.2 Space and urban life 15

3.2 Different terms and their definitions 16

3.3 Different categorization of leftover spaces 26

3.3.1 Establishment of the term to be used 30

3.4. Brief history of leftover spaces 31

3.5 Uses of Leftover Spaces 32

3.5.1 Formal Uses 33

3.5.2 Informal Uses 33

3. 6 Global Emergence 37

3.6.1 Agenda 2030 38

3.6.2 SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities) and synergies 39

3.6.3 Sustainable ways of using leftover spaces 39

4. Subject of the Study 41

4.1 Malmö 41

4.2 Spaces Within 43

4.3 Spaces outside 45

4.3.1 Spaces on top: Living room in the sky 45

Rooftop Discussions: 45

Current usage of roofs in Malmö 45

P-hus or Parking House 47

Rooftops of Bus stops 50

Roof projects around in Scandinavia 51

4.3.2 Spaces underneath 56

Underpasses 57

4.3.3. Spaces Amongst 60

Rails and trails - railways to greenways 61

Parking lots 65

Harbor Peripheries 67

Industrial areas 68

5. Empirical Analysis and Findings 72

5.1 What are the typologies of leftover spaces in Malmö? 72

5.1.1 Preliminary mapping 72

5.1.2 Questionnaire: 73

5.1.3 Interviews: 77

5.2: How can these leftover spaces be used in Malmö? 79

5.2.1 Case study approach: 79

5.2.2 Questionnaire 81

5.2.3 Interviews: 87

5.3: How do their uses respond to Agenda 2030? 89

6. Discussion and Conclusions 98

6.1: What are the typologies of leftover spaces in Malmö? 98

6.2: How can these leftover spaces be used in Malmö? 100

6.3: How do their uses respond to Agenda 2030? 101

6.4. Further research and recommendations 102

6.5. Limitations 103

6.6 Final Remarks 104

8.Appendix 120

Appendix 1 : Semi structured questionnaire for interviews with professionals 120 Appendix 1.1 : Respondent 1 : Åke Hesslekrans’s Interview Summary (Own creation). 122 Appendix 1.2 Respondent 2 : Christian Röder’s Interview summary (Own Creation) 124 Appendix 1.3 : Respondent 3 Gustav Nässlander’s interview summary (Own creation) 125

: 126

Appendix 1.4 : Respondent 4 : Fredrik Björk interview summary (own creation) 127 Appendix 1. 5 Respondent 5 : Jenny Grettve interview summary (own creation) 128 Appendix 1.6 Respondent 6 : Gustav Aulin, interview summary (Own creation) 129 Appendix 1.7 : Maria Hellström Reimer, Interview summary (Own creation) 131 Appendix 1.8 : Elin Hassleberg interview summary (Own creation) 132 Appendix 1.9 Veronika Hoffmann interview summary (Own Creation) 133

Appendix 2. Digital questionnaire for participants. 134

Appendix 3. Coding exercise in the questionnaire for “What spaces come to mind when you see

the term leftover spaces?” 137

Appendix 4. Coding exercise for questionnaire (What kinds of spaces are most likely to lose their

present function?) 139

Appendix 5. Benefits of green roofs and their impacts on SDGs. 142 142 Appendix 6 . Sample answers from the questionnaire. Source : Author. 144 Appendix 7 : Participant mapping of spaces that will lose their function. 144

List of Tables

Table 1. List of interviewees and their profiles.

11

Table 2. List of authors and the terms with their definitions and categorisation at a glance. 17

Table 3. List of adjectives and examples of spaces from Trancik (1986). 2

Table 4. Different categorization from authors at a glance. 25 Table 5. Typology of Leftover Spaces in Malmö 72 Table 6. Categorization of terms used to describe leftover spaces by participants. 73 Table 7. List of the leftover types from the questionnaire. 74

Table 8. Leftover spaces identified by interviewees. 77

Table 9. Summary of strategies for leftover spaces in Malmö 79

Table 10. Participant responses to thoughts on their identified leftover spaces. 81

Table.11. Summary of strategies and types from participants. 85

Table 12(a). Impact of strategies on the SDGs. (Social, SDG 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,11,16) 89 Table 12(b). Impact of strategies on the SDGs. (Economic, SDG 8,9,10,12,17) 92

Table 12(c). Impact of strategies on the SDGs. (Environmental, SDG 13,14,15) 94

Table 12 (d). Impact of strategies on the SDGs. 95

List of Figures

Figure 1. Conceptual representation of problem formulation. 4Figure 2: Maps of selected neighborhoods along railroads in Malmö. 8

Figure 3. Different terms used for this type of space at a glance. 16

Figure 5. Representation of categories of Leftover Spaces in Malmö. 42

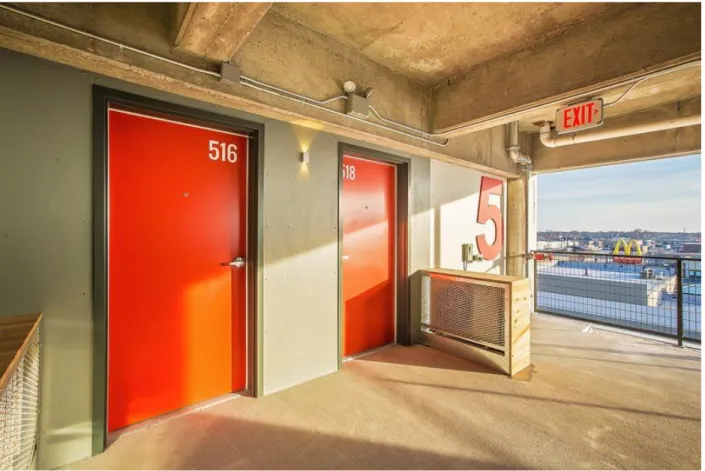

Figure 6. Interior of the garage in Wichita, which is now apartments. 43

Figure 7. Uses of rooftops in Malmö. 46

Figure 8. Map of P-hus in Malmö as of 2020. 47

Figure 9. Rooftops of P-hus in Malmö around the city. 48 Figure 10. Example of use of the roof parking structure. 49

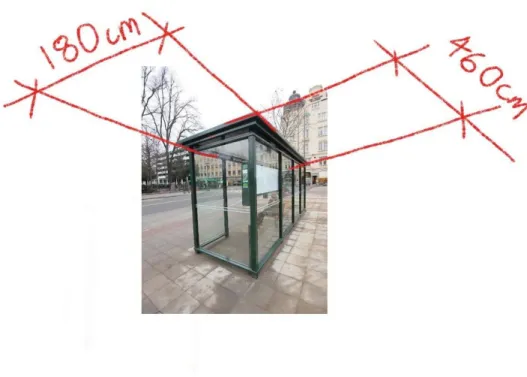

Figure 11. Typical bus stop in the city of Malmö with measurements. 50

Figure 12. Left: Sodermalm Apartments, Stockholm. Right: Tak for mat, Oslo. 51

Figure 13. Kajodlingen. 52

Figure 14. Urban Rigger in Copenhagen showing the three uses of a roof space - solar, green and social. 53

Figure 15. Left: ØsterGro, Copenhagen (ØsterGro, n.d.) Right: 8 House, Copenhagen (8 House / BIG, 2010) 54

Figure 16. Map of “Spaces underneath” in Malmö 55

Figure 17. Leftover spaces: underneath 56

Figure 18. “Tunnelen” in Ammerud, Norway. Conversation of disused underpass. 57

Figure 19. Nobel Tunnel in Malmö 57

Figure 20. Malmö Centralen Tunnel. 58

Figure 21. Leftover spaces: Spaces around 59

Figure 22. Leftover spaces: “Spaces around “i.e spaces outside buildings. 60

Figure 23. Mapping of Existing rail lines in the city of Malmö 61

Figure 24. Example of reusing railways in Taiwan. 62

Figure 25. Map of parking lots on ground. 63

Figure 26. Parking lots in Malmö 64

Figure 27. Vast empty green spaces in Malmö 65

Figure 28. Mapping analysis of Kirseberg 67

Figure. 29. Mapping analysis of Nyhamnen 69

Figure 30. Existing examples from the city of Malmö of uses of certain so called ‘leftover spaces. 70

Figure 31. Participant mapping from the questionnaire “leftover spaces” 74

Figure 32. Summary of all answers from interviewees. 76

Figure 32. Method of creating the final table. Source: Author. 87

Figure 33. Categorization of the SDGs. 88 Figure 34. Type of Leftover spaces in Malmö Malmö Inside and Outside of a built structure (Top of a built structure, under a built structure and around/amongst/in-between built structures) 97

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Cities are complex systems (Batty, 2008). They are organisms or ecosystems with metabolisms. Cities are hubs of innovation, creativity, and prosperity. They are also home to millions. Cities comprise a variety of infrastructure, public services, and buildings housing various functions. Cities are made of masses and voids. Between these built and designed masses lay spaces that are positive and negative (Peterson, 1980). Positive spaces are primarily recreational spaces that may or may not be public necessarily. When they are designed, they create structures like parks, public libraries, and water bodies. Hence public spaces are a part of these so-called positive spaces. According to (UN-Habitat, 2015), 'public spaces' are the spaces between buildings that are open to the public and are primarily of three kinds: (i) Streets and pedestrian access, (ii) open and green spaces (parks, plazas, water bodies, waterfronts) and (iii) public facilities like libraries, community centers, markets. It is known that these spaces contribute to the functioning of a city, its wellbeing, and livability, including social interactions, urban health, labor markets, and the urban environment (Kher Kaw, Lee, & Wahba, 2020).

The focus of this thesis is on negative spaces. These spaces are empty and unoccupied but accessible to the public. It includes informal green spaces, vacant lots, playgrounds, free parking lots, spaces behind or in-between buildings or on top. Negative spaces are commonly known as "lost spaces," "leftover spaces," or "urban voids," and many more in academia. The nature of negative spaces varies from city to city, depending on the degree of urbanization. When their presence is not recognised and continued to be neglected in a city, it can result in social, economic, and even environmental problems for the city (Omar & Saeed, 2019).

Urban planners and architects of the world are becoming more aware of the vast array of opportunities these urban negatives hold for the communities in which they exist. It is noted that open spaces can provide environmental, social, and economic benefits to the community directly or indirectly (Campbell, 2001). Numerous studies in this discourse on "lost/ negative spaces" have focused on identifying and using these spaces to benefit the community. Being a space with no defined function, it is free and hence holds room for opportunities. It holds the potential to be reshaped and redefined as users feel fit (Hudson & Shaw, 2011). While there is a discussion of these kinds of spaces worldwide, this thesis will focus on the city of Malmö in southern Sweden.

1.2 Research Problem

Negative or leftover spaces are thus part of the urban fabric of cities across the world. In many cities, they continue to go unidentified and remain neglected; they are being identified as an asset in some cities. For example, the High Line (New York) is the most famous example of revitalizing a leftover structure. According to academia, leftover spaces are also prevalent in post-industrial cities (Doron, 2006; Accordino & Johnson, 2005). Malmö is also a post-industrial city and has many structures and spaces that reminisce history. As a recent sustainability pioneer, the city is yet to recognize the untapped potential and harm of not using these spaces. These spaces can serve environmental, social, and economic purposes (Campbell, 2001), among many others. If these spaces' opportunity is not explored, these spaces can also cause issues for a city on different levels. In some cases, they can become the cause of lowering property values and lowering the urban environment quality (Wang, Xiang & Luo, 2010). They can also be responsible for the deterioration of an entire area, especially if there are dilapidated buildings.

According to Omar & Saeed (2019), natural, functional, political, economic, planning and design, and cultural factors are responsible for the creation of leftover spaces.

1. Natural factors refer to geographical factors such as land features that create spaces of no defined shape that cannot be used in any way.

2. Political factors include the lack of decision-making, lack of coordination between decision-makers and stakeholders, or inefficient land use and land management policies. Sometimes even wars can result in abandoned portions of the city.

3. Functional factors, on the other hand, refers to the change in functions or land use. The functional factor is primarily associated with post-industrialism or the decline of the industrial component of a city. For example, spaces under bridges or rail lines, edges, or the spaces along highways, abandoned rail yards.

4. Economic factors are those related to urban changes and a shift in the economic scenario. The decrease in property values results in the abandonment of properties or buildings. 5. Planning and design factors refer to the modern movement of design, towards the design

of buildings in isolation from their surroundings. This resulted in a neglect of the open spaces outside buildings.

6. Lastly, cultural factors involve the development of technology and economic growth and reliance on automobiles and suburbanization. Hence this decreased the use of specific spaces in the city center combined with the creation of road infrastructures supported suburbanisation.

Problem of Sustainable Development

As traced above, there are different reasons for which negative spaces occur in cities. In most cases, it is a combination of these different factors that create them. Negative spaces can be seen

both in a good and bad light. If not addressed, their presence can result in social, economic, and environmental problems (Omar & Saeed, 2019). The Brundtland Report in 1987 from the World Commission Environment and Development(UN) defined the idea 'sustainable development' as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." This framework also suggests that progress is sustainable only when it simultaneously addresses the social, economic, and environmental aspects. Hence this is an issue of sustainable development.

1. Social problems refer to the informal usage of these spaces. This includes becoming a space of criminal or illegal activities, such as graffiti and drugs. These spaces also tend to become a trash dump or a space for the homeless (Rahmann & Jonas, 2011).

2. Economic problems refer to the decline of property values. Sometimes, leftover spaces can result in an overall decline in the urban quality of a neighborhood or part of a city. For example, the presence of dilapidated, abandoned buildings in parts of a city can stigmatize the neighborhood and decrease property values.

3. Environmental problems include health risks and visual pollution (Omar & Saeed, 2019). As mentioned above, sometimes leftover spaces house garbage. This, combined with the lack of maintenance of this area, can result in health risks and a decline in the urban quality.

While this can be the downside of negative spaces in a city, it is also found by research that revitalizing them can bring environmental, social, aesthetic, historical and cultural, visual, and aesthetic value to a city (Omar & Saeed, 2019). However, the benefits of using negative spaces are numerous due to their flexible nature (Pluta, 2017). As an “empty” space, the city can use these spaces for multiple functions at different points of time. The use of space is not only to be linked to an investor but are also for the public and other local needs. It is common for the city to sell these so-called damaged or unappealing land plots to developers, and these projects typically do not reflect the needs/wants of society around (Pluta, 2017). Pluta (2017) discusses that these open and empty spaces can serve better purposes than such forms of development, and its revitalization does not require ‘development’ projects. This author also focuses on the ‘emptiness’ of these spaces and how it facilitates new functions. Emptiness brings adaptability, and hence this must be used to create a combination of different functions. These benefits are being realized across the world by revitalizing negative spaces in different ways. As urbanization occurs, the city expands into its hinterland using untouched landscapes while leaving these negative spaces within the city behind and potentially untapped into.

From the Comprehensive plan of Malmö ( Malmö Stad, 2015), it is interestingly found that the city aims to focus on this as well. One of the city’s strategies is to create a ‘green, dense, mixed-function city’; under this, the city intends to use inward densification to achieve this. The strategy states that the city aims to expand within the outermost ring. Hence a study such as this would help the Municipality of Malmö identify and assess their unused spaces that have potential.

Along with this strategy, the Municipality of Malmö is also working extensively on sustainable development. The city has seen the municipality, businesses, food, products, and many different organizations align their work towards the Global goals ever since its introduction. With the global emergence on the rise, more elements of our urban lives are being relooked at through the lens of sustainable development and the Agenda 2030. With this idea in mind, urban planning and design are also being shaped accordingly, and hence the new found potential of leftover spaces offers another means of working towards the Agenda 2030.

Thus, the thesis does not focus on the prevention of leftover spaces but instead on how to turn them into an asset in working towards sustainable development. This is because it has been found that leftover spaces have been a space of opportunity for brownfield development (Németh & Langhorst, 2014) and also facilitated the creation of open and green spaces in dense cities. It has also been found that leftover spaces can bring homeowners, community, realty developers, and others together to address the negative externalities. Using the potential and benefits found in research, there is a possibility to direct the use of leftover spaces towards the Agenda 2030.

1.3 Aim of Study

This thesis aims to explore three areas on the discussion of leftover spaces.

Firstly, the existence of leftover spaces in the city of Malmö, their different types, and the challenges of working with these spaces. To do so, the study uses qualitative and visual methods. Secondly, the study aims to find different ways of using these spaces applicable in the context of Malmö. To do so, the thesis uses a case study approach.

Thirdly, the thesis's final aim is to recognize the benefit of using leftover spaces through the lens of the Agenda 2030 due to the importance of sustainable development in urban studies.

Figure 1 Conceptual representation of problem formulation. Source: Author.

1.4 Research Questions

The following are the research questions based on the research problem. 1.4.1: What are the typologies of leftover spaces in Malmö?

1.4.2: How can these leftover spaces be used in Malmö? 1.4.3: How do their uses respond to Agenda 2030?

1.5 Previous Research

First, space has been extensively discussed by Lefebvre(1991) and Peterson(1980). The study of leftover spaces and spaces alike has been conducted by different authors such as Trancik(1986),

Doron(2006), Abraham & Ariela (2010), Winterbottom(2000), Narayanan (2012), (Jeong, Hwangand & Lee, 2015), Azhar and Gjerde(2016). These researchers attempt to add to the discourse of lost spaces using different terminologies such as urban voids, leftover spaces, vacant spaces. Trancik (1986) wrote a book and detailed the story of leftover spaces in American cities. His book is used as the most common reference when it comes to studying these types of spaces. Jeong et al. (2015) discussed urban voids in the city of Seoul in South Korea. Azhar and Gjerde(2016) in New Zealand and Winterbottom (2000) in Seattle. This paper detailed examples of projects in the city where leftover spaces were converted into space for people.

Laguerre (1994) discusses the everyday uses of leftover spaces in cities, and Steuteville (2014) discusses placemaking as a tool for urban transformation. Hamelin (2016) also outlines different ways of revitalizing urban leftovers. Németh & Langhorst (2014) and Verdelli (2016) discuss the benefits of using temporary use on leftover spaces. While establishing the conventional methods of using leftover spaces, Azhar & Gjerde (2016A) explore how to use them for environmental benefits. This study is vital to establish the use of leftover spaces for sustainable development. Presently there is no such research conducted for the Swedish city of Malmö and broadly Scandinavia. This thesis will add Malmö to discourse on lost spaces of a post-industrial context by identifying a typology of these spaces and suggesting strategies of harnessing these spaces for sustainable urban development or the Agenda 2030.

1.6 Disposition

The next chapter will begin with space and its different types. The position of leftover spaces will be established from the different definitions in academia by different authors. Following this, different typologies of leftover spaces from different authors will be outlined to show the different ways of categorizing these spaces based on the context. This section will then go on to discuss different ways of using leftover spaces. Lastly, the link between leftover spaces and sustainable development will discuss Agenda 2030 and the sustainability aspect of these spaces. The third chapter is the Methodology and methods. Here the chapter will begin with the choice of methods and the relevance they hold for the thesis. Each method will be discussed along with its limitations and validity. The research approach as a case study will be explained, followed by visual methods such as the preliminary mapping and photo mapping. The research uses thematic analysis.

The fourth section is about the subject of the study, Malmö. The section will also outline the typologies of leftover spaces in detail. Here photo mapping method and preliminary mapping will share its findings to give readers a context of Malmö and the leftover spaces the city has. Case studies relevant to each leftover space type are discussed using images and their description to identify similarities and their relevance to the city of Malmö. The case studies are used to draw on strategies that could be applied to the leftovers in Malmö.

The fifth section will present the findings along with the analysis. This includes the findings from the interviews, and questionnaires are structured according to the research questions.

The sixth section will discuss the findings concerning the theories and the research question, limitations, and pointers for further research, and finally, conclude with recommendations and final remarks.

2. Methodology and Methods

2.1 Methodology

The study's aim is threefold; there is a need to use different methods that would complement one another to answer the three research questions. Firstly, for the typologies of leftover spaces in Malmö it was necessary to conduct a preliminary mapping and photographic mapping in combination with gathering professionals' opinions and inhabitants' perceptions. Thus, helping formulate a discussion that is much more informed and holistic.

Secondly, to answer the question about the uses of leftover spaces, it was essential to discuss projects that have already accomplished this. Moreover, if these projects are in the Scandinavian context, it would add more relatability and feasibility to Malmö cases.

Thirdly to discuss the role of leftover spaces in the Agenda 2030, this link is established from the case study approach.

The primary type of research used in this study is qualitative instead of quantitative. This is due to the need for descriptive means to explain the findings rather than numbers. The nature of the research questions stated earlier are descriptive based on the words used in the questions (what, how). Due to the descriptive nature, and the aim of the thesis data needs to be gathered from multiple sources, hence professionals and inhabitants are needed to be spoken with. Their inputs are valuable due to their contact with the proceedings in the city and their experience in their respective field and familiarity. This would help adding to the descriptive nature of the research questions.

2.2 Research Approach

2.2.1 Case study approach

To address the second research question about strategies for revitalizing leftover spaces, there is a need to look for projects that use these spaces and for relatability projects from Scandinavia. The preposition to find relevant case studies was to check if the case used a leftover space. For each type of leftover space, projects that resemble the spaces in Malmö were searched for. This would help show the different ways of using leftover spaces, thus allowing a reader to see the feasibility of the strategies. Hence the qualitative and exploratory form of case study is found to be suitable (Baxter & Jack, 2008). The case studies need to be descriptive and supported by images for the reader's understanding. This helps examine a real-life situation and thus extract strategies.

2.3 Research Design

To answer the first research question about the types of leftover spaces in Malmö and the strategies to be suggested, it was necessary to employ a combination of methods to build a holistic discussion. To inform oneself about the types of leftover spaces in the city, a preliminary mapping was conducted along with photo mapping. Both these methods helped along the way and supported the interviews' and questionnaires' frame. The research approach is also a mix of inductive and deductive approaches to answer the three research questions. The first question uses an inductive approach while the second and third questions use deductive. Inductive theory is used for developing the vagueness of the definitions used in academia, and for the development of a theory specific to Malmö (Bryman, 2012). At the same time deductive is relevant due to the need to test out the theories from different authors and the different typologies suggested by different authors (Bryman, 2012). Deductive theory is used due to the need to observe and draw conclusions from different case examples and their benefits.

Data gathering methods:

The visual methods would help a person who is not familiar with the city of Malmö understand the character of the city and space itself. The findings are presented as a QGIS map.

2.3.1. Preliminary Mapping and Photo Mapping

To inform oneself of the city and kinds of spaces, a preliminary mapping was conducted. There are two types of maps: topographical and topological maps (Xin, n.d.). Topographical maps are detailed and represent the landscape by the use of contour lines, including surroundings and their details. Topological maps are simplified to show vital information and remove details that are considered unnecessary. The research used a combination of the two due to the information needed to be displayed.

Due to the time and scope of the thesis, it was not possible to map the whole city. Trancik (1986) mentions that lost spaces are evident along waterfronts, highways, and railroads. This formulated the selection criteria to limit the scope of the thesis, given the time constraint.

Selection criteria for mapping and analysis

● Identifying significant roadways, railroads, and waterfronts

● Identifying areas adjacent to major roadways, railroads, and waterfronts ● Identifying areas that are underdeveloped, developing and to be developed

Figure 2. Maps of selected neighborhoods along railroads in Malmö. Source: Author, QGIS

The map above highlights the neighborhoods of Nyhamnen, Östra Hamnen, Kirseberg, Persborg based on the selection criteria devised based on Trancik(1987). Nyhamnen is a waterfront industrial neighborhood, Ostra Hamen is the neighborhood with the rail lines, Kirseberg is both a post industrial and railway neighborhood, lastly Persborg is semi industrial as well, with the rail line passing through. To identify spaces, Peterson(1980) provides a definition of derived spaces as one that is formed based on the design of ‘figural’ space. This will be explained in the theoretical background. This definition was used to identify leftover spaces.

Their locations were pointed out on the map to show their numbers in the city. Upon observation, the hand-drawn mapping was fine-tuned on QGIS to be presentable. An Excel sheet of the place's name, postal code, and X, Y coordinates( https://rl.se/rt90) was fed into the QGIS map. The results are presented in chapter four. This was combined with photographic mapping to capture their appearance in Malmö.

This mapping informed the questions that were formulated for interviews with professionals (Appendix 1). This method also shapes the structure of chapter four in the thesis.

2.3.2 Semi-structured Interviews

The qualitative research methods were used to gather information expressed in words as this would help understanding how professionals perceive leftover spaces in Malmö. This method is suitable for the thesis as it was necessary to know how the Municipality is dealing with the identified leftovers in the city. The professionals would share their experiences of being involved in such projects and their thoughts on strategies of using leftover spaces.

Participants involved those who work with the Municipality, architects in the city, professors. Five of the interviewees are working with the Municipality in different departments, one from SGRI (Scandinavian Green Roof Institute), two are affiliated with the University, and lastly, an architect. A total of 9 interviews. A list of questions was prepared based on preliminary mapping conducted in the city, and the understanding gathered from the literature review. The questions prepared can be found in Appendix 2. Five of the interviewees are males and four females. All nine of the interviewees were approached via emails. Some interviewees themselves gave some of the other interviewee's contacts. All interviews were conducted on Zoom due to the pandemic and not in person. Each interview was recorded for ease during transcription upon consent.

Sl.no Name Profile Organization

1 Åke Hesslekrans Architect at City

Planning office

Malmö Stad

2 Christian Röder Real estate

department Malmö Stad

3 Gustav Aulin Landscape Architect Malmö Stad

4 Gustav Nässlander Consultant SGRI

5 Fredrik Björk Professor and

Historian

Malmö University

6 Jenny Grettve Architect Independent

Architect

7 Maria Hellström

Reimer

Professor and researcher in design theory and practice

Malmö University

9 Elin Hassleberg Working with SDGs in Sofielund

Malmö Stad

Table 1. List of interviewees and their profiles. Source: Author. 2.3.3 Questionnaire and participant mapping

A questionnaire was sent to up to thirty participants, along with a digital map of Malmö, for participants to mark the spaces they associate with and share their perceptions.The digital questionnaire was chosen over a face-to-face questionnaire due to the pandemic and restriction of social interactions. There was no need for an in-depth discussion and only to gather many opinions quickly. This data gathered will be presented in detail in the empirical findings chapter and can be useful for one who would like to work with leftover spaces in the city of Malmö. The questionnaire was formulated on Google Forms with a link to a Google Map to mark places of the participant's choice. It took about four weeks to complete responses and analysis began after collecting twenty responses. The broad themes of the questionnaire are - defining leftover spaces and identifying them, describing ways of changing these spaces, and lastly, spaces in the city that will lose their present function. Questions included an open-ended interpretation of the understanding of the term "leftover spaces," naming the spaces that come to mind when thinking of this term, along with describing ways of changing the chosen space. The respondents were chosen based on their activeness in exploring the city and awareness of different spaces, and if they have resided in the city for at least a year. The age groups range from 22-36.

While a questionnaire can be efficient and straightforward, it can be a challenge as the researcher is not present to help with interpreting questions (Bryman, 2012). Hence simplified questions that prompt one to write a paragraph answer were chosen. A few limitations include the inability to ask further questions to the respondents, appropriateness of the questionnaire to all respondents, which could result in either irrelevant or partially completed answers (Bryman, 2012). It was chosen to stop sending the questionnaire out due to the limited responses. Despite sending the questionnaire to 30 participants, only twenty-two responded. Two of those 22 responses were considered incomplete and partially answered and hence were not used in the analysis.

2.4 Research Analysis

2.4.1 Thematic Analysis

This thesis uses thematic analysis to study the data gathered in the interviews and questionnaires. Liu (2020) uses five steps to analyze the data (1) Data organization, (2) Identification of ideas and concepts — coding (3) Building overarching themes (4) Generating findings (5) Confirm findings.

All nine interviews were transcribed manually. Each interview was simplified into a mind map (Appendix 1.1). The data organization and coding were done manually, as well. Key phrases and topics were identified from the transcription (Silverman, 2015). The repetition of topics and keywords resulted in themes and, thus, the technique's validity and reliability. Silverman (2015) suggests organizing codes into themes for structural purposes. The themes are chosen based on focus areas of the thesis, such as "leftover spaces," "challenges of using leftover spaces," "uses." The research question topics were also used as a basis to generate themes. Thematic analysis has helped summarize the key findings from the extensive data set gathered (Nowell et al., 2017). Findings from the questionnaire are also added to the themes generated from the manual coding exercise. This helped to develop a more holistic discussion of the findings.

3. Theoretical Background

In this section, an attempt has been made to define space and negative space. This discourse establishes the presence of leftover spaces in cities. The section will then attempt to focus on leftover spaces and their different definitions and typologies from different authors. The different ways of using leftover spaces are discussed, followed by the global emergence of sustainable development.

3.1 Space

3.1.1 Derived Space

Before defining leftover spaces and their qualities, it is imperative to define space itself. For this thesis, this section will explain the concepts of space that come into place when understanding the realm of leftover spaces in cities. Space is a concept and term that has fascinated humanity for a long time. Space was associated with volume, geometry, and form, but as the decades went by with anti-space introduction, the meaning of space also changed (Peterson, 1980). At this very time, space was being recognized as one of the main objects of architecture. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, space directly translates to 'time' or 'duration' and 'area' or 'extension' (Patricios, 1973).

Peterson (1980) discusses the different conceptions of space. Space is understood to be a 'free' entity in nature; it is found everywhere. It is also conceived as abstract, continuous, vast, and has no form. Peterson (1980) also shares Arnhem's notion of space as something that exists even in the absence of objects, as it goes beyond the objects in it. Space is also seen to exist best in its natural state, but there has been a need to capture it and shape it according to one's own needs. Peterson (1980) explains this notion with the example of walls and furniture, causing a break in the natural state of space. He also compares space to nature and how they should be subjected to limited influence from man to maintain a balance.

According to Peterson (1980), there are two basic notions of space. These notions are opposite in nature. He calls them space and anti-space, similar to the logic behind matter and antimatter. "Anti-space is undifferentiated, formless, infinite, universal, singular, and continuous. Space is differentiated, formed, finite multiple, and discontinuous. Space, by definition, will be obliterated by the presence of Anti-space".

Peterson (1980)

In an interview, Peterson states that there are three types of space that are experienced (López-Marcos, 2017), namely –

1. Man-Made space 'figural space' is closed and formed (exterior piazzas, interior rooms, street corridors) or what he describes as positive space.

2. Natural space or 'open continuous space' is unformed, surrounding, or background space (parks, landscapes, oceans, sky, the earth is seen from the moon).

3. Derivative space is formed as a support to the design of figural space. Peterson defines this space as a leftover space, an in-between zone, or what he calls a negative space. In Peterson's (1980) article, he also describes negative and positive space. He describes negative space as the space between walls. He explains the difference between the two spaces using plans of historic buildings. Using a French word for pocket called poché, he says when the wall is solid, it is poché (positive space), and if it is hollow inside and can be accessed, it is a 'habitable Poche' (negative space). Peterson explains that the city's negative spaces include residual areas within blocks, backyards, and irregular pieces of land. In contrast, urban spaces such as streets, squares, public spaces are considered positive volumes of figural spaces or positive entities. This categorization is relevant to the thesis as Peterson's definition of a derived space is what is in this study's interest. He talks about this negative space: 'residual' and 'hidden' and a 'by-product' of the built environment as an essential component in architecture (López-Marcos, 2017). The terms residual, by-product, derivative imply the dependence on a planned structure. Thus it means residual spaces do not exist on their own.

3.1.2 Space and urban life

Lefebvre's work on space brings out its importance when experiencing and practicing social life (Zieleniec, 2018). His work emphasizes the need for a shift in focus on space from being an abstract entity to one where life and social practices create different meanings and values. According to Lefebvre, space is not only a naturally occurring material or void that is waiting to be filled with objects/contents, but it also has a social dimension. He also talks about the production of space occurring as a result of society working to meet its needs and wants. This happens for the sake of social cohesion, functional capabilities, and maintaining political power and control (Zieleniec, 2018). Space has also been used under the pretext of capitalism; where production and consumption are organized. Hence Lefebvre also refers to space as a 'material product,' a medium of capitalism and interactions between people/ people and objects. According to the above discourse, it is understood that these different types of spaces are used in different ways and have different implications on urban life and cities.

This thesis is particularly interested in the derived spaces of Malmö , its nature and implications on urban life. The following section will discuss the different studies conducted on these so-called 'derived' spaces and their types in cities.

3.2 Different terms and their definitions

It is observed that the most used terms for these spaces are void, gap, lost, and leftover in academia. Before the academic definitions are studied, the following definitions are taken from the Merriam -Webster dictionary to understand their fundamental meaning -

1. Void means "containing nothing," "empty space," "not occupied," "not inhabited." "the quality or state of being without something." (Void, n.d)

2. Gaps are a "a separation in space," "a break in continuity."

3. Lost is defined as "obscured or overlooked during a process or activity," "not made use of," and "ruined or destroyed physically or morally."

4. Leftover is defined as "something that remains unused and still exists," "remainder," These dictionary definitions will be useful towards the end when concluding the general definition of these spaces. Below is an image of the different terms used in academia for the family of these spaces followed by their definitions from different authors.

Figure 3. Different terms used for this type of space at a glance Source: Author.

Table 2. List of authors and the terms with their definitions and categorization at a glance. Source: Author.

"Vacant urban land" (Northam, 1971)

The geographer, Northam, first used the term to describe abandoned lands, residual, small-sized, and irregular pieces of land with physical restrictions, such as steep declines and flood hazards. Vacant urban lands are usually found in 'transitional areas' and hold potential for future uses (Northam 1971, 345–346)

"Lost spaces" (Trancik, 1986)

Roger Trancik, in Finding Lost Space, discusses these spaces using the term "lost spaces." They are defined as "undesirable urban areas," "ill-defined." These spaces lack physical borders. According to Trancik (1986), these spaces were created due to road systems and land-use changes. Lost spaces include abandoned railroad sites, empty factory areas, outdoor parking lots, residual in-between spaces. The following table shares the author's adjectives for describing different identified "lost spaces" in American cities.

Table 3. List of adjectives and examples of spaces from Trancik (1986). Source: Author.

"Waste space" (Lynch, 1990)

Waste space is defined as a space leftover with no value due to production or consumption-related activities.

"TOADS" (Greenberg, M. R., Popper, F. J., & West, B. M.,1990)

Temporarily Obsolete Abandoned Derelict Sites or TOADS are defined as unused pieces of land scattered and vary in shape and size. Some sites may have the presence of an abandoned structure or are just vacant lots. TOADS are no longer in productive use, but some form of treatment is required to change this and reuse them.

"Residual land" (Winterbottom, 2000)

Winterbottom (2000) uses a standard dictionary and the definition from Trancik (1986) to explain residual spaces. This study of residual spaces is conducted in the context of a neighborhood called Fremont in Seattle.

"Derelict land" (Doron, 2006)

According to Doron (2006), the term "derelict land" invokes a feeling of an unattractive piece of land. It is often that appearance or aesthetics is used as a factor to identify these spaces. These spaces are seen as harming the built environment due to their lack of designated function (Doron,2008).

"Vacant land" (Doron, 2006)

"Vacant land is land that is now vacant and could be redeveloped without treatment, where treatment includes any of the following: demolition, clearing of structures or foundations, and leveling."

Doron (2006) emphasizes the broadness and vagueness of the definition. Vacant land does not imply a vacant piece of land. It can also have structurally sound buildings, unlike the definition of open spaces provided earlier. The vacancy is temporal, which is neither 'physical nor

occupational.' While vacant land is not empty as such, it can be devoid of the presence of humans.

"Urban voids" (Abraham & Ariela, 2010)

According to Abraham & Ariela (2010), these spaces are found outside of common urban spaces, in other words - periphery. They can occur because of planned projects as a space left behind, unthought-of, or unaccounted for in the planning process.

"Leftover spaces" (Qamaruz-Zaman et al.,2012)

In this article, leftover spaces are explained as the spaces that occur next to planned development. These spaces could be along or below transport-related infrastructures such as highways or railways. These spaces are undeveloped and are commonly publicly owned or 'no man's land' such as abandoned old building yards and dockyards.

“Urban Voids” (Narayanan,2012)

Based on the definition of void meaning 'being without,' an urban void can be viewed as space without 'permeability' and 'public realm.' This refers to space not having any social or physical barriers.

"Brownfield sites" (Perović, S., & Kurtović-Folić, N.,2012), (Tanja, 2018, p. 216)

Brownfield was a term first used in the United States in 1992 (Perović et al., 2012). Its definitions vary, and it is shaped according to its context.

The definition from the United States- Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) 1997: "Brownfields are abandoned, idled, or under-utilized industrial and commercial facilities where expansion or redevelopment is complicated by real or perceived environmental contamination." ( U.S. EPA.,2003)

"Terrain vague" (De Sola-Morales, 2013)

Terrain vague is defined by De Sola-Morales (2013) in Europe as undefined and empty spaces that have inherent potential.

These spaces refer to the spaces at the edge or on the "border." Liminal space is characterized as space on the frontier, space 'in between.' It is also a space 'on the border of two prevalent spaces,' which is not part of either (Shortt, 2015) (Dale and Burrell, 2008: 238).

"Urban voids" (Jonas & Rahmann, 2015).

According to Jonas & Rahmann (2015), urban voids are both gaps and leftover buffer zones. They do not have any functions or boundaries. They are viewed as unsafe and are also home to illegal activities. Their study is based in Tokyo, Japan.

"Urban Voids" (Jeong, Hwangand & Lee, 2015)

Jeong, Hwangand & Lee(2015) use the term "urban voids" for these leftover spaces and state that these spaces in the city and, in particular, the ones in residential areas have the potential to be "recycled, re-powered, re-densified, reformed and integrated with green technologies." The definition provided in their article is- "unused, underused or currently used with potential for better use."

"Leftover spaces and In-between spaces" (Azhar and Gjerde,2016)

This article uses the definition from (Rahmann & Jonas, 2015) to explain leftover spaces - as an ephemeral object, a site, and a possible future.

"Interstitial spaces" (Wall, n.d)

Interstitial spaces are small, irregular spaces that are enclosed (Wall, n.d). They are typically found between, under, and over large infrastructural forms and are enclosed on at least one side by transportation, power, water, or communications-related infrastructure. Aesthetically interstitial spaces are unattractive and disconnected 'islands' in the city.

From the above introduction to the various definitions provided by research from around the world, it is evident that all these authors speak of the same type of space due to the synonymous adjectives. From all the definitions above, the authors describe this space through two perspectives - their usage and their spatial/physical qualities. Terms such as disused, misused, unused, underused, lack of function, vacant are all the terms that explain their usage. Terms such as irregular shapes, odd-shaped, no boundaries, ill-defined, border or periphery, residual unattractive, found under or between infrastructures speak of similar aesthetics.

3.3 Different categorization of leftover spaces

As a concept, typology is part of the urban studies realm (Foroughmand Araabi, 2016). While typology refers to the 'study and theory of types and classification systems' (Lang, 2005), it is said that the term 'typology' itself is vague (Foroughmand Araabi, 2016). However, a system of classification is meant to make sense of the proceedings of the world. Typology as a concept is highly relevant when studying similarities and differences between objects or phenomena. Due to this reason, this thesis suggests a typology of leftover spaces to group both similar types of spaces and separate the different ones.

Table 4. Different categorization from authors at a glance. Source: Author.

From the table, the following discussion will explain each categorization in some detail to show the contextual nature of these typologies.

TOADS (Greenberg, M. R., Popper, F. J., & West, B. M.,1990)

This research on TOADS suggested three types based on American cities- (1) Once productive and valued

They were once productive and valued but become TOADS due to being abandoned. Examples include factories no longer in function such as paper mills, textile, furniture factories, and abandoned warehouses.

(2) Once productive and not valued

This refers to the structures that were in function but were disliked by the community. For example, a slaughterhouse or paper mill which leaves an odor. Their decline would not bother the community.

(3) TOADS close to other TOADS

This refers to pieces of land that are odd-shaped and have never been developed in any way. These TOADs are left on their own due to their proximity to other TOADs or landfills.

Residual Spaces In Fremont, Seattle (Winterbottom, 2000) 1. Non-Spaces

These spaces are commonly present in the vicinity of mobility pathways such as median strips, right of way along highways and roads.

2. Leftover Spaces

These spaces are disconnected from their surroundings. According to the author, they are "created by intrusions into a previously open space." They include the oddly shaped spaces by intersections, setbacks, frontages, underpasses, traffic islands.

3. Dual-Use Spaces

These spaces typically have a single function and are used for this, and otherwise are not used. For example, parking lots that are empty after business hours.

Urban voids (Abraham & Ariela, 2010)

Abraham & Ariela (2010) use the narration of delineated green spaces to compare and contrast open voids with unplanned voids. With the birth of public spaces in Greek times, the agora and Roman forum, urban voids were defined. These spaces are thus called 'premeditated' voids, and along with them, unplanned urban voids exist as well. They are found on the periphery of urban spaces and usually are abandoned and undesigned. The authors propose three types of urban voids-

(1) Planned voids are born out of urban design such as premeditated voids; they are defined and designed, such as - streets, urban enclosures, and city squares.

(2) Fortuitous or unplanned urban voids refers to the types of spaces that occur by chance or serendipity. They are 'recesses' or gaps between buildings. They are edges of parking lots, small yards no longer in use, alleys.

(3) Contemptuous voids refer to urban decay, such as brownfields, derelict spaces, spaces in industrial areas.

Urban Voids (Narayanan, 2012)

1. Planning voids are created due to errors in planning practices, thus leaving these evident gaps in our cities.

2. Functional voids have lost their actual usage in the city, such as an underused park that could become a garden space for those in the vicinity.

3. Lastly, geographical voids are born due to geographical features such as rivers, hills, valleys, etc. He also mentions that extreme conditions like natural disasters or conflicts can also create urban voids.

Urban Voids in Seoul, South Korea (Jeong, Hwangand & Lee, 2015)

According to their scale, the researcher's classified urban voids start at the building scale, plot scale, block scale, neighborhood-scale, and community scale.

Leftover spaces in Wellington, New Zealand (Azhar and Gjerde, 2016; Azhar and Gjerde,2016A)

The typology is of six types- spaces between buildings, enclosed on three sides, behind buildings, front of and under, and on top of buildings.

These above different categorizations show the contextual approach to the typology study of leftover spaces. Each study described above is conducted in a different city, and hence the suggested typology is contextual. This is a critical aspect of this thesis, and this means that there is no typology to cross-reference the leftover spaces of Malmö with. Just as the above studies conducted their research based on theory, history, and field observations, a similar study is inspired for the case of Malmö.

3.3.1 Establishment of the term to be used

In the past few decades, many authors contributed to this realm by studying urban leftovers from different perspectives since the term's first appearance. Lopez-Pineiro (2020) published a book called 'A Glossary of Urban Voids,' which collects over two hundred terms from 'terrain vague' to 'buffer zone' and so on. In this book, the author reflects how different studies and terms have impacted the study of urban voids and alike. Firstly, based on the characteristics and applications, different terms have been brought to light. Secondly, different types of vacant spaces, rail lines, spaces between buildings, and urban wilds were identified based on the different physical characteristics. All these studies that have been outlined in the above sections viewed urban leftovers in their unique way, and hence most authors have introduced their term. With the addition of numerous detailed studies, the glossary that has resulted is 'extensive and haphazard.' Many academics have found that this is proof of the difficulty involved in defining these spaces.

Lopez-Pineiro (2020) uses the term Urban voids through the book and describes how urban voids invoke a negative feeling. Lopez-Pineiro (2020) also explains that, in some cases, voids are leftovers. This thesis will use "urban leftovers" as the umbrella term to refer to these spaces in Malmö. This is due to the spaces that were found as a result of the research conducted, their

nature is of a aforementioned derived space. However, the definition of a derived space is most closest to the fundamental meaning of ‘leftover’i.e this space continues to exist and is dependent on a figural space.

The term yet again invokes a negative feeling. This is due to its meaning - 'unused or unwanted' or 'residual,' which can result in misunderstanding of the term. However, all the different terms, as seen, do not necessarily convey a positive feeling.

According to the Webster dictionary, the fundamental meaning of leftover is 'still existing after the other parts are used.' This meaning is what the thesis wants to convey. Their position in the urban fabric allows these spaces to become an opportunity (environmental, social or ecological, etc.). This is not the case with other public spaces in a city, thus making urban leftovers unique. In conclusion, their unwantedness makes these empty spaces residual, and this residual nature gives the urban leftovers the potential that other urban spaces do not hold.

3.4. Brief history of leftover spaces

Automobiles are responsible for the transformed landscape of cities all around the world. Most urban land is used for either the storage or movement of automobiles (Trancik, 1986). As highways and rail lines cut through cities, they leave around them these unused spaces. With the progression in urban design, the need to change land use planning also resulted in relocation of functions (Trancik, 1986). The moving of industries and the dying of old transportation facilities also resulted in different types of wastelands. At the same time, urban design was very much centered around the building itself. This resulted in the neglect of open spaces, streets, and gardens (Trancik, 1986). He describes European development in the 20th century, where buildings are mere objects in isolation placed on a large land piece. Green spaces are used as a buffer, and hence there are vast grasslands interspersed between buildings. These spaces are used by few people and are unreasonably large; as criticisms grew, excessive planning resulted in new terms such as "planned wasteland" and "new urban desert" (Cybrisky, 1999).

Apart from the universal reasons for the occurrence of leftover spaces, some are bound to the type of city. This brings the discussion to post-industrial cities as they are also a site for leftover spaces. This is important due to Malmö being a post-industrial city. The decline of the industrial component of cities, suburbanization, and the decreasing population has led to the emergence of vacant lands (Accordino & Johnson, 2005).

"The industrial ruin is both a concrete place and because it has lost its identity, a hollow place that can engender and contain fantasy, desires, expectations."

(Doron, 2006).

The post-industrial scape is generally identified as these vacant or derelict lands due to their appearances. Post-industrial spaces, abandoned factories, unused harbors, abandoned train stations and yards, spaces at the peripheries of the city, zones between the city and suburbs, ruins from the industrial era are identified as the type of spaces that hold these qualities and appearances (Doron, 2006).

Doron (2006) captures the dual nature of an industrial ruin or, in other words - a leftover space. These industrial ruins or leftover spaces are a space that has no identity. However, it is one that appears wild and disconnected from the surroundings and hence can take any identity. As these spaces have lost their identities and are now free to take any identity, shape or form they can be molded by people as they feel fit. In some way, it represents the idea of the "Room of Requirement," an idea created by JK Rowling in her novels of the Harry Potter series. ( A 'Come and Go space' that appears to those in great need of something. This room can take on a function that is needed by the person.) While this is a description of a fantasy space, the spirit of this idea describes the opportunities held with leftover spaces.

Thus, it is seen that the birth and continued existence of leftover spaces and spaces alike is inevitable. It is due to the more prominent global mechanisms at play. In comparison, poor urban land management, lackluster decision-making processes, and oddly shaped parcels of land among the many reasons contributed to the accentuation of leftovers. Hence these spaces are also a sign of the times and not just a sub-product of policies and planning.

3.5 Uses of Leftover Spaces

Historically leftover spaces were seen as a problem that needed to be addressed or prevented. However, with time, they are now seen as a resource and a space for social and ecological transformation (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). This thesis's focus is not on preventing the occurrence of leftover spaces but instead on how to make it an asset in working towards sustainable development. From research and different projects from around the world, it has been seen that leftover spaces have been used in different ways (Németh & Langhorst, 2014).

Broadly their uses range from being a community garden on a single plot to a small-scale urban agricultural project; they have also been subjected to adaptive reuse when there are buildings for business ventures and alike. Leftover spaces have also become social spaces that house community activities and take the role of civic infrastructure. Research has also found that in sites that were long abandoned, they have become a platform for ecological services. For example, cracks in pavement becoming stormwater infiltration enablers—vegetation serving

climate mitigation efforts such as improving air quality and plant life addressing soil contamination.

3.5.1 Formal Uses

Hamelin (2016) outlines approaches to uplifting urban voids.

First, Artwork. Public art and installations are a simple tool that has been used worldwide as a tool in urban transformation. It uses mere color and creativity to transform an otherwise dull and uninviting space into one of expression.

The second, Tactical urbanism. This tool is advocated by government actors, local actors, or community groups to transform a specific space or area that is usually for the good of a particular community or neighborhood. The strength of tactical urbanism is in its temporality and low-cost methods, thus ending up being real-world testbeds. Lydon & Garcia (2015) mention that tactical urbanism has little to no risk to the community. Commonly these projects are small in scale; it has usually involved makeshift seating along streets, appropriating empty parking lots to garden lots, changing roads into temporary green spaces, and street fairs (Voigt, 2015). It is also believed that the ideas behind tactical urbanism, "lighter, quicker, cheaper" help in the production of better spaces in cities (Project for Public Spaces, 2015).

Third, permanent projects (Hamelin, 2016). This kind of approach comes with a higher budget and commonly does not involve extensive public participation. For example, the City of Calgary, Canada, developed underpass guidelines as part of an underpass revitalization project across the downtown. These guidelines formally recognize the need to integrate these neglected spaces into the urban fabric while serving their purpose of being zones of mobility (City of Calgary, 2010). As a result, in Toronto, the space below three overpasses is converted into a neighborhood park with a skatepark, flexible community space, and public art installations (Waterfront Toronto, 2015). These projects may not reflect the needs and wants or the expressions of the people due to their top down approach but end up creating long term permanent solutions.

The fourth approach is a coordination of tactical urbanism and planned approaches. Hamelin (2016) presents a PPP (Pop-Up, Pilot, Permanent) framework as a beginning for works to come. Such a comprehensive approach is highly beneficial (Vogt, 2015).

3.5.2 Informal Uses

Leftover spaces are also home to informal activities (Laguerre, 1994). The spaces are generally outside the view of formal authorities. Despite the uninviting appearance of some of these spaces, they are used for different types of activities. Sometimes these uses can be conflicting to the community. They include homelessness, drinking, street art, drugs (Laguerre, 1994). The

users do not own the property and, in some way, appropriate the space to suit their needs at a certain point in time (Doron, 2006)

As we have seen, there is both a formal and informal dimension to reclaiming leftover spaces. The formal approach to revitalizing leftover spaces includes facilitation by the government, municipality, private investors. This includes community organizations, who use the space for activities either temporarily or permanently (Khalil & Eissa, 2013). As mentioned earlier, an informal intervention is an appropriation done by users who are not part of any formal organization or institution. This intervention is solely to serve the needs of this user.

Németh & Langhorst (2014) found that many cities worldwide adopted strategies to deal with these unused land plots, some permanent and temporary. They also found that cities tended to adopt less permanent uses than temporary ones. This is due to institutional and financial reasons.

3.5.3 Temporary Use

As identified before, leftover spaces house potential for new opportunities and new uses. Sometimes, when a space is abandoned, it is waiting to be acquired by a new owner. However, this process can be time-consuming, leaving this space in a continued state of disuse. In this period of waiting, these spaces can be opened for temporary uses.

A space, which is now a leftover, could have served a function some time ago. Also a space, which is now serving a function, may become a leftover as time passes. This fluidity of spaces with time is the essence of cities. This is where the dimension of the temporality of spaces comes in. The temporariness of spaces is a challenging definition in architecture and planning due to its diverse qualities. Temporary uses can occur in residual spaces, or in spaces that can house multiple uses. It can be formal, informal, spontaneous, political, and illegal. Temporary use can also be intentional to bring out specific characteristics of unused or vacant space (Wesener, 2015). It is also low risk with a possible high reward and supports partnerships; it can be for a few hours, a few days, seasonal, and sometimes years. Temporary use has seen many benefits, and one such benefit is its use in leftover spaces (Bishop & Williams, 2012).

An international research project with support from the European Union between 2001 and 2003 analyzed temporary use projects in different cities (Helsinki, Amsterdam, Berlin, Vienna, Naples). This project identified that temporary use-based projects provide the participation of all kinds of citizens. This encourages them to contribute to urban spaces and urban life. This project also revealed that urban voids or unused spaces are the sites for temporary uses and could thus result in their revitalization (Overmeyer, 2007) and urban regeneration (Chang, 2018).

It has been found that this tool can also bring economic value in terms of increases in investment. Social value has been impacted positively from an increase in entrepreneurial aspects. However, these benefits and outcomes of temporary uses are site-dependent.