Sensing Tranquility

Spaces for Tranquility - an Atmospheric approach.

Author: Maria Fernanda Jaraba Molt Master Thesis

M.Sc. Urban Studies

Department of Urban Studies,Malmö

Abstract

This thesis attempts to introduce tranquility as a spatial concept and to develop first hypotheses into its application within Urban Studies by the application of an experiential theoretical and methodological framework. In order to comply with this objective, three existing fields of research (Restorative Environments, Calm Technology, Stillness) are presented as orientating spatial notions that are akin to tranquility. Subsequently, the research field around atmospheres is introduced as a theoretical and a methodological framework working at the grounds of the executed investigations. These took place in two places within Malmö: a silent after-work concept called Tyst Off the Work and a resting room, referred to as Vilrum, in one of the buildings of Malmö University. Autoethnographical accounts of the two cases are brought forward in the form of micrologies and subsequently interpreted. The thesis concludes with three hypotheses about the rationale around tranquility in the investigated cases: the understanding of tranquility as a rest between productive action, the affective impact of the public-private setting as exclusive, and a tendency towards standardized notions of tranquility.

1

Contents

List of Figures ... 3

1. Introduction ... 4

Aim and Research Questions ... 5

Limitations and Reflexivity ... 6

Thesis Structure ... 7

2. Contextualizing Tranquility ... 8

Choice of terminology ... 8

Existing Concepts ... 8

Restorative Environments ... 8

Calm Technology and Slow Technology ... 9

Stillness ... 9

An experiential approach ... 10

Interim Conclusion ... 11

3. Atmospheres ... 12

Atmospheric Experience and Social Inequality ... 14

Sharing and Staging of Atmospheres ... 15

Summarizing remarks ... 16

4. Catching Atmospheres ... 16

Knowing in ... 17

Knowing about ... 18

Knowing through ... 19

5. Experiencing Spaces for Tranquility ... 20

Tyst Off the Work ... 21

Vignette: Silent Theater ... 22

A calculated cure ... 24

Atmospheric coding ... 24

Staging tranquility ... 25

Niagara’s Vilrum ... 25

Vignette: Secret Room... 27

Soft Exclusivity ... 28

2

Ambiguous Freedom ... 29

Some comparative remarks ... 29

6. Discussion ... 31

Only a break... 31

Public-Private Feelings ... 31

Standardized Tranquility ... 32

7. Conclusion and Outlook ... 33

3

List of Figures

Figure 1. Photograph of the Tyst Off the Work location (El-Alawi, 2018)……….21 Figure 2. Vilrum plate and symbol (Malmö University)………..25 Figure 3. Pictures of the resting room in Niagara (own photos)………..26

4

1. Introduction

Groundedness, inner peace, the connection to oneself. Meditation and mindfulness practice, forest-, rain- and ASMR-sounds on youtube, apps to relax, all-inclusive yoga retreats, home decluttering and “intermittent fasting from technology” for the peace of mind, monastery stays and Western adaptations of zen gardens. There seems to be a never-ending search for recipes for calmness of the mind. Reminding of diet trends, every once in a while, a new recipe appears – or a new adaptation of an old one – is widely used as a promise and a marketable feature in different industries, urban planning and the experiential economy. Some disappear, get substituted by new solutions. Others turn into real subcultures. It is a vague, but somehow constantly relevant topic, creating trends, described with a wide variety of vocabulary and advice. Chasing for the tranquility-recipe through (market-regulated) activities, consumption, abstinence or new ways of spiritual practice is so naturally integrated in Western discourse and popular culture that it hardly ever has to explain itself. The search for tranquility in urban space is of course not new, as it reflects the basic needs for rest and mental and emotional composedness. It has always been part of the human longing for contentedness and plays a role in most of the religions and spiritual practices. My interest, however, is more specifically the part of it where and how it relates to an urbanized and industrialized reality. The underlying narrative of an ambiguously stressful nature of life in the (post)modern and capitalist urban reality and the urgent need for more mental and emotional calmness can be largely traced back to Simmel’s classic writing The Metropolis and Mental Life (2006) and remains an evergreen topic in cultural and commercial production. An increasingly blurry diagnosis exists and is often rather used implicitly as a self-evident fact, sounding roughly like this: The amount of sensorial impressions in the ceaselessly active, densified and technologized contemporary world surpasses the human capacity to process daily experiences and leads to an urban “information overload” (As for instance described by Stanley Milgram (1970)) that, in turn, increases stress levels, reduces the capacity to remain calm and focused, minimizes empathy for other persons (a Simmelian notion) and in the long-term leads to mental and physical instability, possibly even resulting in stress-related chronic illnesses and death.

It might certainly not come as a surprise that constant activity and rapidly changing impressions don’t make for a healthy life. Nor is it illogical that, in the face of the potentially destructive force that a lack of tranquility can become, the need and desire for it grows. However, it is interesting (and at a closer look, sometimes puzzling) what this need and discourse is creating. Even if not seen as such, there is a scattered, somehow incoherent culture around tranquility that this desire has been birthing. Material and non-material objects are being created, paired with literature, events, art – and with them, spaces and situations.

It is these spaces and time-spaces that this work takes a closer look on by conducting an investigation in two exploratory-experimental working steps. The first stage situates the concept of tranquility scientifically and outlines the highly interdisciplinary mosaic that it currently moves in. Two examples for spaces with a designated tranquility function in the city of Malmö are subsequently presented and contextualized. The second stage is dedicated to an autoethnographic, experiential analysis of the same examples by experimenting with accounts of perceived atmosphere. Finally, a number of hypotheses are formulated by interweaving the theoretical considerations with outcomes of the atmospheric accounts.

5

Aim and Research Questions

Mirroring design properties and presentations of spaces with the experience of them is an attempt to understand the effect of places and their design more deeply by investigating between the objective and the subjective. I asked myself what might happen if the two aspects are confronted with each other – on the one hand, how a space is designed from the designers’ point of view, and on the other hand, how the space subjectively feels when moving within it. How do different types of created tranquility feel? Does the experience of the space mirror the claimed intentions? Do aspects reveal themselves that are not visible when taking a “neutral” position upon analyzing its design? The possible answers are not only interesting to understand the effect of spaces on its users for scientific progress, but could also result useful for a higher sensitivity towards spatial experience.

Spaces that specifically serve the function to offer tranquility to their visitors seemed to offer themselves very well for this exercise, as the communicated intention of their design is clear. Applying an autoethnographic perspective offers the possibility to have thick and in-depth descriptions and analyses that include nuanced layers of affect. Answers deriving from my subjective accounts would of course not be representative for all the visitors. However, even if autoethnographic methods risk to be seen as unscientific and solipsistic, they also bear the potential to reveal under-researched aspects that cannot be captured by solely applying positivist parameters. This way of working is intended to offer an alternative to analyzing problematics around tranquility one-sidedly. Amongst those are the quantitative measurements of biomedical variables or the assumption that less sensorial input equals more tranquility. These aspects are to a large extent kept separately from the study of subjective experience or social issues in the city. Urban social matters are also often analyzed in terms of economic variables, social dynamics and the distribution of territory, but urgently need more analyses of mechanisms that work on a smaller, individual scale of personal experience.

In summary, I consider it important to employ new perspectives that find a connection between the material design and individual perception of space as embedded socio-spatial contexts. Accordingly, interdisciplinarity, the mixing of objective with subjective information, and the confrontation of design choices with personal experiences are at the ground of this investigation about tranquility. The interdisciplinary and open nature of the field of Urban Studies offers the possibility to do exactly that – broadening the frames of analysis in order to gain a holistic understanding of a topic that is of relevance for life and planning within the urban.

Two aims can be formulated for this thesis, one resting upon the other. As a first step, it aims to introduce and direct attention to tranquility as a relevant spatial research concept within Urban Studies. Second, an experimental set of research tools is tested on two cases within the framed field in order to investigate the relationship between design and experience in the two examples for Spaces for tranquility. Accordingly, the research questions are:

o How can tranquility be scientifically embedded as a spatial and experiential notion? o Which atmospheric particularities are perceived in the two investigated cases?

o How are the experienced spatial arrangements within the two examples connected to or disconnected from their tranquility function?

6 As can be understood through the research questions, this work is intended to be rather hypotheses-generating than hypotheses-testing. The generation of hypotheses is based on both exploration and experimentation – it is explorative in a sense of locating possible syntheses between research fields in order to situate tranquility scientifically and experimental by trying out a particular research design that contrasts regular Urban Studies practice.

Limitations and Reflexivity

Opening up tranquility as a research topic within urban studies could be approached from countless different angles that are of interest for a general grasp on how tranquility emerges, how it can be subjectively felt, if there are intersubjective patterns of feeling and creating tranquility, which “tranquility trends” surge and why, and how the access to tranquility as a necessary feeling is distributed spatially. Within this work, it is obviously not possible to cover insights or hypotheses regarding all of these issues, as gross simplifications would be necessary to utter such big statements. This is why the topic of this work is narrowed down to only one exemplary approach to one specific aspect. This specific aspect is the individually experienced atmosphere of spaces designed for

tranquility and concluding reflections about the design and possible effects of the two examples.

Due to its character as a novel, or scarcely used thematic intersection within urban studies, the composition of knowledge that forms the basis of this study is highly interdisciplinary and eclectic. By conducting the research in this way, the aim of this paper is to act as a precursor for future research. Accordingly, this study rests upon the awareness that the developed material asks for refinement, deepening and critical application of the elaborated notions. Finding a definite, clear-cut definition of tranquility or creating design instructions for tranquility is consequently not possible within this particular frame. The reflections within this investigation should rather be seen as a reflexive attempt to facilitate future research and the development of a better understanding of the urban spatialities of tranquility through cumulative production of knowledge.

Another aspect that could be seen as a limitation is the extensive use of qualitative, as well as autoethnographic material about my personal experience in and of space. The applied methodology does not lead to objective, quantitative results and autoethnography in particular has been criticized as “self-indulgent, narcisstic, introspective and individualized” (Méndez, 2013:283). I, as a researcher, am taking several roles at the same time as the research incorporated participation, observation, analysis and interpretation. By simultaneously applying different perspectives as one person, “blind spots” of analysis can certainly arise. However, it is not the aim of this paper to apply an objective cause-and-effect logic onto atmospheres and tranquility. On the contrary, this work is supposed to offer a methodological counterbalance to existing research on the topic, and embracing radically subjective accounts as usable scientific material.

Finally, despite the thorough search, the overwhelming majority of the literature found for this research has been written by men with a Western cultural background. A serious underrepresentation of different (cultural, gender, milieu-specific, intersectional etc.) perspectives is given in both atmosphere research and urban studies in general. This is unquestionably hindering the scientific development and limits the knowledge base for this work. Especially the work with atmosphere is in need of a deeper understanding of empirical material that reflects upon the relationship between the experience of atmosphere and the (social, cultural etc.) position of the person exposed to it. Being a woman with a mixed cultural background (German-Chilean) and

7 conducting the research as a foreigner in Sweden, I do attempt to add additional perspective, but I am simultaneously not expecting to act or speak in a representative manner for a specific demographic group or all the potential users of the studied places.

Thesis Structure

The following work is comprised of seven chapters. Following the introduction, the term tranquility is situated in the context of previous research by engaging with three different concepts from different disciplines that are tangent to the issue, namely Restorative Environments, Calm Technology and Stillness, and critically evaluating their usefulness for the notion to be created within this work. The evaluation of the research fields is complemented with an introduction to atmospheres as a relevant research branch for the experiential orientation of the thesis.

The following explanations in chapter three attempt to clarify and illuminate the relationship between individual feeling, social dynamics and space by introducing the concept of atmospheres, their dynamics and social significance.

Building on the theoretical framework around atmospheres, the fourth chapter engages with methodological implications of the work with atmospheres and introduces the micrology and Aisthetic Fieldwork as the methods applied onto the given cases.

The analysis follows in the fifth chapter, contextualizing the two given cases – a silent after-work event and a resting room in Malmö University – on both an urban and a material level. The autoethnographic atmospheric accounts are presented in the form of micrologies and subsequently interpreted individually and comparatively.

Chapter six serves as a connecting discussion between the contextualization of tranquility as a spatial field of research and the outcomes of the experiential material. Finally, the last chapter summarizes outcomes and offers an outlook onto a possible continuation of research around tranquility in urban space.

8

2. Contextualizing Tranquility

Choice of terminology

The term tranquility was chosen as the closest approximation to the topic of this work. Tranquility can be seen as an environmental condition and also as a feeling. It is often used interchangeably with stillness, serenity, calmness and peacefulness, which makes the inherent ambiguity of its use clear. On the one hand, tranquility refers to the general calmness of a situation or a place, as in a perceived atmosphere in the surrounding environment; on the other hand, it is used to describe a calm state of mind in opposition to mental agitation. Tranquility was chosen as the defining term because both of its linguistic meanings are relevant for this work. Both meanings are often seamlessly connected (and sometimes even equated) when used in media, casual talk and even academic research, reflecting a tendency to assume a causal relationship between environmental conditions and the mental and/or emotional state of a person. This research dissects the spatial meaning of tranquility by moving at the intersection between the two inherent meanings that it entails – relating to the spatial environment, and to personal experience.

Existing Concepts

Whilst the word tranquility is seldom used as a term, some concepts applied in different fields of research are akin to tranquility. The following literature overview specifically points out research around three tranquility-related concepts which are clearly situated in urban space by merging different notions from the fields of environmental psychology, media science and human geography.

Restorative Environments

When searching for empirical research about tranquility in the city, approaches from environmental psychology suggest themselves. Especially research around Restorative Environments employs the related notions of stress and the restoration of resources “depleted” through stress. The resources referred to are cognitive, physical and social capabilities (Lindern, Lymeus, & Hartig, 2017:182). A quantitative model is applied by comparing the research participants’ release of cortisol (Tyrväinen et al., 2014; Ward Thompson et al., 2012) or rating on “perceived tranquility” (Herzog & Chernick, 2000; Pasini, Berto, Brondino, Hall, & Ortner, 2014; Watts, Pheasant, & Horoshenkov, 2011) when being exposed to different spatial settings or soundscapes and photos of those. A strong focus lies on the comparison between restoration within streets and green spaces (often referred to as “urban” or “man-made” and “natural” settings) with varying degrees of density and outlook.

The outcomes, however contended within the field, mostly show correlations between the material composition of places and physical signs of stress and tranquility. However, it is questionable if the correlation implies causation. The investigations mostly conclude an objective preference of green space for restoration and fail to capture subjective variables that influence the relationship between persons and the space they are surrounded by, as well as possible consequences that these might have on an individual’s capacity to feel tranquil or stressed in different places. The methodology has a large focus on visual and auditory material instead of being-in the places and excludes a lot of contextual information, e.g. the cultural meanings attached to different types of landscapes or other variables that might be at the ground of perceiving a place as restorative or stressful. Some studies have moved towards more contextual perspectives (Filipan et al., 2017; Newman & Brucks, 2016), nevertheless they tend to apply very simplistic categorizations within the contextual considerations.

9

Calm Technology and Slow Technology

In the late 1980s, the term Ubiquitous Computing was coined by Mark Weiser as a way to describe the development towards a continuous presence of computing technology in human environments. Rooted between computer science and media science, Ubiquitous Computing deals with the personal and social consequences that this development can lead to. Weiser called attention to the “information overload” that the presence of too much informational technology can lead to, and advocated an orientation towards Calm Technology (Weiser & Seely Brown, 1995). The idea behind Calm Technology is to produce efficient and helpful technological products without overburdening the attention of its users. In order to reach this aim, calm design helps to locate information into the “periphery” of attention by not placing it into center stage1.

Calm Technology as a concept has had a big impact within some design fields and media studies (Feijs & Delbressine, 2017; Yu, Hu, Funk, & Feijs, 2018), but it has also been critically deconstructed, for instance if the moving of technology to the background actually leads to a calmer result (Schmidt, 2013) and if the placement of technology at the margins of attention is even desirable or rather controlling (e.g. surveillance systems) and manipulative (e.g. neuromarketing) (Veel, 2013).

Slow Technology went further by referring to the need for technology that “promote[s] moments of

reflection and mental rest in a more and more changing environment” (Hallnäs & Redström, 2001:202). The concept is grounded in a critique of the efficiency-driven Calm technology and proposes to project information in the form of sound or visualizations into space. Hallnäs and Redström see a possibility to heighten the awareness and reflection through this almost artistic approach to design. Though Calm Technology and Slow Technology have been influential concepts, designing against “information overload” and creating reflexive space through technological design have been recurrent topics without necessarily referring to the same terminology (e.g. Akama, Light, & Bowen, 2017; Ghajargar, Wiberg, & Stolterman, 2019).

Stillness

Within human geography, research around stillness has been developing over the last years. It is characterized by a rather philosophical approach to stillness, deriving from its meaning as physical non-movement and simultaneously transcending its definition as a strictly physical phenomenon. Its spatial experience and/or expression remain constant variables of analysis by often relating it to (potential) movement, speed and rhythm (Abrahamsson, 2009; Radywyl, 2009). Within this research branch, stillness is often understood as having a paradoxical relationship to contemporary spatial design: stillness is neglected by the thoroughly orchestrated, productive and efficient time and space of capitalism, while specific types of stillness are produced (like moments of administrative queuing and residual spaces as leftovers from planning) by the same system. Consequently, acts of breaking through expected stillness or breaking expected movement with stillness can be seen as creative acts of opposition, as acts of refusal that uncover normalized spatial practices (Cocker, 2011).

1

An example brought forward by Weiser is the inner office window, which – contrasting an open workspace – offers the possibility to communicate within the periphery instead of taking too much attention. It is possible to peak, wave, signal busyness by closing the curtains, signal openness to a meeting by opening them etc., whereas working in an open plan workspace can lead to marginally relevant information taking center stage.

10 David Bissell has been researching stillness as a (counter)part of mobility studies, analyzing notions of stillness in commuting (Bissell, 2014). David Conradson broaches the issue of stillness in the context of Therapeutic Landscapes (Conradson, 2017). He considers the “experiential economy of stillness” an economic branch that extracts money from a psychic desire for stillness. The rising trend of retreats in Western societies acts as an example for this development. Conradson talks about a new valorization of stillness, which reflects work-life balance pressures and has become part of a broadening experiential economy that offers “the promise of fewer external intrusions, with an accompanying narrative which suggests that such an environment will foster personal renewal and restoration” (Conradson, 2017:35). Commercial and non-commercial expressions of this new economy can be the curation of “slow experiences” and therapeutic mind-body practices.

An experiential approach

The three concepts explored in this analysis cover different aspects by applying biomedical, geographical, philosophical, as well as design-oriented frames of interpretation and form a knowledge base at the grounds of this work. Nevertheless, whilst illuminating a heterogeneous variety of aspects, they have something in common: Tranquility-related concepts (stillness, restoration, calmness) that are worked with are orientated on a certain level of abstraction by focusing on design for tranquility, the cultural and symbolic meaning of tranquility, or the comparison of medically defined levels of tranquility. However, further questions about the experience of tranquility are seldom asked.

Against the backdrop of the existing research, it becomes clear that elaborations on tranquility as a

spatial experience are rather marginal. This research gap is what the work at hand is attempting to

complement by rolling out epistemological and ontological reconsiderations on the grounds of an experiential approach. To embark upon the issue of tranquility in urban space, the lens of analysis has to be able to capture not only objective materiality or cultural meaning, but also the personal experience of space that is interwoven with these aspects. Some first steps in this direction can be found in David Conradson’s investigation on retreats and notions of stillness as an experiential economy (2011; 2017) and Michael Buser’s (2016) work on atmospheres of stillness, but they still lack a more stable, accepted and systematized expression that could turn it into an own research branch.

The interface of individual experience and space is an utterly challenging subject to research. This is due to the ambiguous nature of the matter; when posing the question about how social and material conditions of places affect persons who move within them, the line between the subjective and the objective blurs. The physical properties, the social composition and factors like movement, rhythm and use of places can certainly be documented and talked about in clear manners that don’t leave too much space for disagreement; it is rather the mechanism between space and the affected individual that is hard to understand and capture scientifically. In order to understand this connection better, atmosphere offers itself as a fitting – though also vaguely defined – framing concept.

“[T]he phenomenological notion of atmosphere is linked to the lived space, to the space of ‘users’, to urban life in its full complexity. Feeling and sounding of urban atmospheres – something architects are trained to do – does constitute a link to the social production of space. Sensing a place is not just an individual and elitist exercise, but a relevant tool of ethical and emancipatory design.”

11 The research field theorizing and analyzing atmospheres is relatively young and therefore to large parts in the stage of deepening conceptualization and development of different strands of thought. It has been existing as a relatively small research niche since the 1990s and enjoys growing popularity ever since. Research about atmospheres is an inherently interdisciplinary undertaking and can therefore be found in a multitude of fields. Conceptualizations of atmospheres have partly originated in (mostly German) philosophy, more concretely in aesthetics and phenomenology (Böhme, 1995; Borch & Böhme, 2014; Hasse, 2012), and extended to architectural theory (Pallasmaa, 2014; Schmitz, 1999; Zumthor, 2014), anthropology (Bille, Bjerregaard, & Sørensen, 2015), sociology (Löw, 2013) and the interface of human geography and urban studies (Anderson, 2009; Buser, 2016; Cloke & Conradson, 2018; Healy, 2014), to name a few.

At the same time, ambiances developed within the francophone tradition. Whilst the subject of both terms is mostly concordant, the French strand of research is rather rooted in architecture and Situationist thought. Jean-Paul Thibaud’s work is unquestionably the most influential within the current francophone theorizations of ambiance. Emphasizing situated experience of urban ambiances, Thibaud meshes design and perception by studying both the creation of ambiances and their affective consequences (Thibaud, 2015b; Thibaud, 2015a). However, in the course of the last years, the notions “atmosphere” and “ambiance” have been coalescing and can together be identified as a spread-out, interdisciplinary research field. Proof for this development is the repeated quest from different sides to develop scientific overview over theoretical and methodological approaches and the ways in which they differ or resemble. Attempts to organize, differentiate and merge knowledge are surfacing accordingly (Schroer & Schmitt, 2017; Sumartojo & Pink, 2019). The common denominator of theorizations on atmosphere is the felt necessity to integrate both experiential perspectives and sensorial perception into the study of space or – seen from the other side – to integrate notions of space into the study of affect and aesthetic experience. By giving subjective experience of feeling, sensing and pre-reflexive apprehension of space center stage, the chase for completely objective measurability of space and its affective impact is questioned.

Interim Conclusion

The purpose of this chapter is to clarify the term” tranquility” as it is used within this thesis. A first, very general definition of the term was introduced and juxtaposed with neighboring concepts from different scientific fields, namely Restorative Environments, Calm Technology and Stillness. They were chosen for laying the focus on urban spatial expressions of tranquility-related concepts.

Whilst the existing research serves as a starting point and knowledge base for this work, it was pointed out that the delineated concepts do largely leave out an experiential approach to tranquility which would allow deeper considerations about its connection to spatial and emotive experience. However, the main interest of this work lays certainly in the experience of tranquility as a spatial

phenomenon.

In order to fill the experiential gap, the research field around atmospheres was introduced as a fitting framing concept to be applied in the investigations about tranquility.

Accordingly, the next two chapters serve to clarify atmospheric notions as both a theoretical framework and methodological considerations forming the basis for the subsequent analysis and discussion.

12

3. Atmospheres

It is the second time that I am meeting this person, and it feels like an unclear case of slight sympathy, mixed with mutually ambivalent signs about beginning a new friendship. We are taking a walk around Triangeln and see that Konsthall is open – a public gallery that I visit seldom but somewhat regularly, even though I am not the biggest art connoisseur. I don’t go to Museums that often. It is not due to a lack of interest; I don’t know why it is. But the exhibitions in here are always for free, so it feels easy to simply go in and have a look.

The gallery is a spacious hall with large windows that form the façade, a light wooden floor and white walls. During the day, Konsthall is a very brightly lit place, and it offers a lot of room to walk and to move from one piece of art to the next. I perceive it as beautifully empty, white, tasteful, clean and distancing.

Once the entrance door closes behind us, I can hear the silence – only some footsteps and a slight mumbling resound in the background. Some people are in here, but it is hard to say how many. Is it five or does the size of the hall make them seem less than they are? A woman is standing next to the entrance with her hands folded behind her back, nodding at us. I assume that she works here.

We walk into the space. I instantly begin to move much more carefully than I did outside of the hall, and we talk with a lower voice. We are talking in Spanish. There are some abstract paintings in the background, and I can see colorful woven wool objects in indefinable forms laying in a row. This is when I am beginning to feel insecure. “I am not going to understand this art”, I think. I read the description of the exhibition, but it leaves me even more clueless. My company nods silently whilst reading and looking at the first pieces.

Very close to the entrance stands a table that is filled with patterned books – some of them damaged, others are unharmed. Some are closed, others open. I walk towards the table and instinctively open the cover of one of the books. Somebody shrieks in the background and I immediately flinch and take a step back, quickly realizing my mistake.

The woman from the entrance jogs towards me and tells me in Swedish not to touch the books, as they form part of the exhibition. I can feel myself blushing and quickly apologize in English, as Swedish doesn’t seem to come to my nervous mind. “I guess I was too curious”, I say, laughing nervously. Both shortly laugh with me, and my company asks her questions about one of the paintings. They immerse themselves into a conversation in Swedish, whilst I walk with them, smiling and nodding, waiting for the embarrassment to fade away.

13 What I tried to transport through this vignette is the first-hand approximation of a subjective micro-experience in a place. Although it is nothing but a simplified extract and a reduction of feeling to words, it shows a multilayered experience of sensory perception, bodily feeling, emotion and sociocultural factors as bound to time and space. It is the ‘feeling of the situation’ (Thibaud, 2015b:42) from my personal perspective, and with it, my perception of the atmosphere. Being commonly used in commonplace language, “atmosphere” is often interchangeably used with “mood” or “ambient”. Simultaneously, atmosphere refers to the gaseous envelope of earth, which shares its condition with the former meaning as being just as invisible, located at the background and taken-for-granted if not pointed out. Knowledge about it is tacit and implicit. Nevertheless, philosophical, sociological and geographical thought has been devoted to comprehend the nature of atmospheres. Atmospheres derive from physical and social components and permeate delimited spaces and consequently the individual mental states and feelings within these spaces. They are quickly, pre-reflexively perceived (Löw, 2016:117), not as juxtaposed objects, but as holistic atmospheres and evoke a “spontaneous emotional response” (Borch & Böhme, 2014) – they are not clearly delimited, rather a “haze” that fills spaces (Böhme, 2016:114), “affective powers of feeling, spatial bearer of moods” (Ibid:119), located “between material or existent properties of the place and the immaterial realm of human perception and imagination” (Pallasmaa, 2014:232), a “potentiality of spaces to influence feelings” (Löw, 2016:172).

In his essay “Atmosphere as the fundamental concept of a New Aesthetics”, Gernot Böhme argues that atmospheres are the primary “objects” of perception and perception, in turn, is not only sensory “observation”, but includes the affective impact of the sensorial input. He puts emphasis on the current relevance of studying atmospheres in the context of the aestheticization of everyday life. Böhme argues on the base of ”The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproduction” (Benjamin, 2008), the relevance of atmosphere is no longer limited to the sphere of arts, but more generally applied to all of aesthetic production, as he considers all aesthetic production the production of atmospheres. This move expands the space of possible objects of study to the commonplace, as aesthetic production, and with it the production of atmospheres, encompasses a large and increasing part of contemporary life worlds, ranging from advertisement and day-to-day consumer products to cosmetics, events and interior design. Böhme calls for a new aesthetics by that widening of focus:

“The new aesthetics is thus as regards the producers a general theory of aesthetic work, understood as the production of atmospheres. As regards reception it is a theory of perception in the full sense of the term, in which perception is understood as the experience of the presence of persons, objects and environments.” (Böhme, 2016:116)

A common thread running through the theorizations of atmospheres is its double-edged nature “as at once interior and exterior to the individual” (Schroer & Schmitt, 2017). This condition implies two fundamental characteristics of atmospheres. Firstly, atmospheres permeate simultaneously into different directions; they are a product of the physical, aesthetic and social composition of space, they are created by constellations of persons and things that the feeling individual is part of. Secondly, atmospheres can neither be classified as an entirely objective, nor a subjective phenomenon. They are produced through certain qualities and constellations that are objectively given – qualities that can be perceived through our senses – but their perception is personal. Therefore, atmospheres can be understood as including both the objective and the subjective, being “the common reality of the perceiver and the perceived” (Böhme, 2016:122).

14

Atmospheric Experience and Social Inequality

Martina Löw adopts the concept of atmosphere in her book Sociology of Space, adding a socio-spatial dimension to its understanding and putting it into the context of the constitution of space. According to Löw, space is constituted through the simultaneous and mutually conditioning processes of spacing and synthesis2 (Löw, 2016:134). These two processes of constituting space work on the grounds of perceptual processes and influence the emergence of atmospheres, which are the “invisible” but perceptible characteristics of space:

“Atmospheres are the external effectuality of social goods and people in their spatial arrangement as realized in perception. Due to atmospheres, people feel at home or strange in spatial arrangements. Atmospheres obscure the practice of placement.” (Löw, 2016:233)

By placement, Löw refers to the material and symbolic arranging of space generating (temporary or permanent) places. The pre-reflectively perceived, symbolic and affective effect of atmospheres in a place can overlay and hide the power structures and processes of placement. Löw accords with Böhme that atmospheres don’t only happen serendipitously, but can also be “staged for perception” (Ibid:192), ergo consciously produced in the pursuit of specific results that are connected to the reasons and objectives of placements.

Whilst Böhme conceptualizes atmospheres as intersubjective facts that are experienced in the same manner by different individuals, e.g. as serene, homely, friendly or tense (Böhme, 2016:113), Löw challenges this understanding on the grounds that individuals have different “perceptual schema” which are learned and shaped by past experiences and conflicts, developing some senses better than others and creating preferences and habits. These preferences and habits in turn, are embedded in socialization and culture, and depend “on structural principles such as gender, class, or ethnicity” (Löw, 2016:177). Consequently, the perception of atmospheres varies between persons and always stands in relation to the position of the “perceiver” within the power structures of a society. The perceptual habits at the grounds of this process are not simply a projection of individual experience onto space, but rather a filter, pre-structured by education and socialization, that influences how impressions affect the perceiver.

This means that atmospheres can reproduce social structures, including social inequality through perception. Sensations like for instance fear or unease, as possible affective reactions to atmospheres, can limit the ability of persons to constitute space. In these cases , the inclusion or exclusion is realized by the interplay of two variables: the individual perceptual habitus and the atmosphere of a place (Löw, 2016:182).

The geographer David Sibley does not write about atmospheres but is tangent to Löw’s reasoning when theorizing “Geographies of Exclusion”. Starting from sociological theory and psychoanalysis, he argues that the control mechanisms of institutions like prisons, schools or bureaucracies are projected onto smaller features in the general urban landscape, creating spaces that “signal

2

Spacing refers to the (mostly symbolic) positioning of social goods and people resulting in the identification of a spatial arrangement in relation to other placements. Examples for spacing can be the division of supermarkets into different sections through signs, or borders and attached practices signifying the entrance to communities. Synthesis is defined as the linking of goods and people to the places through perception, imagination and memory. Synthesis is the enabling of recognizing ensembles of goods and people in space as unified elements, e.g. the perception of a church, the church forecourt and the graveyard as one space.

15 exclusion” in “diffuse” forms (Sibley, 1999:85). Individual experience of difference and control in these spaces “moulds” individuals, groups and localities in different manners. At the same time, he insists that the possibility for agency exists; individuals can reflexively adapt to environments whilst maintaining a personal distance to the symbolism and attached value system (Ibid:87).

What connects both thoughts is the notion that socialization and experiences of inclusion and exclusion structure the perceptual schema and spatial habits of individuals, instilling preferences and aversions towards different spaces. Consequently, social inclusion and exclusion can be reproduced by spatial characteristics that are socially produced and that transcend mere physical traits. Whilst Sibley refers to these spatial characteristics on the level of symbolism and social behavior, Löw does not think in terms the effect of various individual elements in space, but rather of holistic “spatial arrangements as realized in perception” (ergo atmospheres, see above) –the entirety of the spatially located situation – which contain an own potentiality.

Sharing and Staging of Atmospheres

The strong influence of atmospheres on social life is also broached by Mikkel Bille. In his investigations about staged atmospheres (Bille, 2015; Bille et al., 2015), Mikkel Bille emphasizes the embeddedness of atmospheric experience in social dynamics and thereby, like Löw, questions Böhme’s widely adopted conceptualization of atmospheres as phenomena which are universal in perception. Nonetheless, for Bille and most of the atmosphere theorists, atmospheres bear the potential to be shared – not qualitatively felt in the same manner, but jointly recognized as a type of affect – and can therefore also be “staged”. Bille inducts this reasoning from his work which points out the role of lighting as a collectively staged atmosphere of “cozyness”, whose feeling and definition varies from individual to individual, while it is socially experienced and expressed as a shared atmosphere (Bille, 2015). Atmospheres are staged or orchestrated in order to obtain social goals or to encounter possible affective realities beyond the given situation.

“In the staging of atmosphere, repetition and emulation can also constitute significant aspects. The intentional orchestrations of atmospheres are not shaped in a vacuum, but are rather oriented toward ideals of how a place, event or practice should or could feel. This, of course, does not necessarily entail success of achieving it. Such normative orientations embrace the simulation of behavior by referring to exemplary atmospheres” (Bille et al., 2015:36) [emphasis in original]

The potentially normative staging of atmospheres can accordingly also be seen as a tool at the service of formation of power, constituting the active counterpart to Löw’s perceptual perspective on the power dynamics inherent in atmospheres. Bille claims that atmospheres can be “space[s] of political formation that underli[e] the realm of discursive politics, but cannot be controlled in any simple and unambiguous way by political agents” (Bille et al., 2015:34).

Stephen Healy’s conclusions about affective atmospheres in shopping malls (Healy, 2014) ascribe even further power to staged atmospheres. Concluding from his investigations on air conditioning in malls3, he insinuates that the orchestration of atmospheres can have regulatory effects on visitors as a current employment of subliminally operating bio-politics (Healy, 2014:42).

3

Healy concludes that Air conditioning and its minimization of thermal stimuli can evoke “languishment” in visitors and induce in them a state of “involuntary vulnerability”, leading to an enhanced openness to affective influences, including incentives to continue shopping.

16

Summarizing remarks

As atmospheres are the main “objects of study” in the following chapters, this chapter serves to outline the theoretical framework at the base of an atmospheric understanding within this work. Atmospheres are “the common reality of the perceiver and the perceived”, or from the perspective of the experiencing subject, the perceived effectuality of the surrounding spatial arrangement. Adopting Löw’s perspective, the subjective process of perception has to be separated from the atmosphere itself, in a way in which its affective consequences (of for instance felt inclusion and exclusion) arise as a combination between atmosphere and perceptual habit. Even though atmospheres are subjectively perceived and therefore affect different persons in different manners, it is still possible to share atmospheres as a common understanding between persons who move within them.

Against the backdrop of these theoretical remarks, the following chapter deals with the methodological implications of working with atmosphere and introduces the micrology as the adopted method of analysis.

4. Catching Atmospheres

“All of us have had the experience of somehow knowing atmosphere in ways that are almost inexpressible and difficult to communicate to another person, which we might find deeply moving or make us feel vulnerable in some way. However […], atmospheres have something to offer as a focus of research because they not only shape how we understand our worlds, but also draw us together with others and condition how we remember what has come before and imagine what might happen next.” (Sumartojo & Pink, 2019:99)

Researching with atmospheres requires taking a leap of faith in the value of feeling and subjectivity for scientific research. Nuanced feeling remains largely unexpressed within scientific and political discourse. By defining the utterable through a language that is structured for objectivity, Western scientific discourse tends to not grant space and an adequate language for subjective and felt experience, classifying it as a private matter (Hasse, 2003:184). This leads to the exclusion of the subjectively felt from large parts of the production of knowledge and limits its possible expression to the private sphere and aesthetic production. However, only a radically subjective approach offers the possibility to deeply engage with the complex, interwoven layers of the affective experience of space. One way to engage with this kind of knowledge is by “thinking atmospherically” (Sumartojo & Pink, 2019:72) – but how can one write about atmospheres in a scientific manner if they are such subjectively felt, complex phenomena?

In order to address this question, two methodological implications may be derived from theorizations on atmospheres:

1. As explained above, this work does not presuppose an intersubjective validity of individual perception of atmospheres. The experience of atmospheres is always influenced by personal perceptual schemata, associations and moods. Therefore, research requires qualitative accounts that embrace the subjectivity of atmospheric experience.

17 2. At the same time, atmospheres are perceived in highly nuanced layers of feeling. The empirical data can be a slight feeling of unease or insecurity, a scent evoking a memory, a relaxing jaw or a sense of hurry. Descriptive accounts require a high level of detail and access to perceptual information that can be documented as directly and richly as possible. The work with informants is therefore ethically challenging: whilst it is desirable for the researcher to attain a detailed and deep description of feeling, privacy and a balance between intimacy and professionalism have to be respected.

Considering these implications, I have decided to use autoethnographic accounts of perceived atmospheres in two cases as empirical data. Whilst the atmospheric accounts form the principal analyzed data, they are juxtaposed with the specific social and material context of the two cases. In this way, it is possible for the research and the reader to grasp possible reasons, continuities and discontinuities between the places as presented and designed on the one hand, and as experienced on the other hand. The choice of these two perspectives is supposed to facilitate a discussion in which the autoethnographic descriptions – how the places presented themselves as phenomena – can be confronted and compared with the presentation of these places by their creators.

A helpful differentiation, following Sumartojo & Pink (2019:71-91) is the one between researching in, about and through atmospheres . Knowing in atmospheres refers to the consideration of the nature of atmospheres in research as constantly emerging and bound to the perceiver. Knowing about atmospheres refers rather to the retrospective analysis of atmospheres by turning accounts of being

in atmospheres into descriptive and possibly representative material. The two steps in the

production of knowledge, in turn, can be applied as research through atmospheres, which means using atmospheric methods as tools to gain a greater understanding about particular topics. The three aspects cannot be clearly delimited from each other, and all of them play a role in this work, as elaborated in the next subchapters.

Knowing in

Knowing in atmospheres refers to an epistemological exercise at the grounds of research and requires a reflexive awareness of the own contribution to atmospheres that one is situated in. This aspect is partly covered by the theoretical and methodological considerations of chapter 2 and this chapter, which illuminate the way atmospheres are understood in this context, and are elaborate on in the analysis.

Two ambiguities come up when employing any subjective method to catch atmospheres: First, neutrality cannot be presumed. The perceptual habit colors everything as interpreted and felt when experienced. Second, as Thibaud has rightfully noted (Thibaud, 2015a), the analysis of atmospheres manifests a dilemma that forces the researcher to prioritize. Disguised under the veil of the unconscious, some deep-laying sensitivities to affect may not be fully rationalized – it is a matter of intellectual impossibility to localize and point out every single suppressed, indirect and unverbalizable affect in a given moment. However, the “fertile exoticization of the ordinary and the infra-ordinary” (Hasse, 2017:48)4 bears the potential to illuminate atmospheric experience further than the sole observation of exterior persons and objects or interviewing of others.

18

Knowing about

Knowing about atmospheres is aimed at with the analysis and discussion in the following chapters by bringing forward and interpreting the specific atmospheric experience. The given experiential accounts are methodologically informed by Jürgen Hasse’s concept of Micrologies (Hasse, 2017) and Jürgen Rauh’s thoughts on Aisthetic Fieldwork within atmospheres (Rauh, 2017). Both developed a phenomenological approach to perceiving and “catching” atmospheres.

Hasse’s micrologies are not an attempt to generate representative data, but to explore what can be captured in the first place; therefore, they always have an exemplary character. Based on Georges Perec’s investigations on the infra-ordinary (Perec & Sturrock, 2008), commonplace situations, the mundane and incidental, are seized and put down on paper, questioning the commonsensical, the natural, the self-evident. One-time situations are rather observed than participated in and described in sensorial and emotive detail. In order to avoid an analysis that is still directly affected by the impressions, interpretations on the micrologies are written with a time distance of at least 6 months after the experience. The outcome is twofold: it includes both an insight into the “deep structure” of situations, and into the perceptual habit and distribution of attention of the author (Hasse, 2017:51-52). Micrologies embrace feeling as scientifically usable material and contrast the hunting for objectivity of the positivist sciences. They can be seen as what Hasse calls the “raw material for phenomenological interpretation” (Ibid.).

This form of gaining knowledge is based on the experience of situations and includes affects, as well as the spontaneously reflexive into the analyzable empirical material. A clear distinction between the experiencing subject and its environment cannot and should not be drawn – on the contrary, the shared reality of both becomes the principal object of study.

Rauh’s Aisthetic Fieldwork offers a similar view on atmospheric methodology. Based on an autoethnographic account and a relatively free form of writing, it pins down three conditional components for aisthetic fieldwork: “the recording of all sense impressions, the expansion and supplementation of these perceptions using a mnemonic protocol, and the fact that the person collecting the data is the same as the person evaluating these data” (Rauh, 2017:10).

These three components, together with Hasse’s method for micrologies, have been used as an orientation to catch the atmospheres of the two cases; after a short introduction into the rough context of the places, the investigations on both cases begin with a description of the place, followed by a micrological text of the experience of finding myself in the given situation and an interpretation of the micrology. In contrast to Hasse, participation was not avoided, though, but rather embraced in its subjectivity. The micrologies refer to one specific visit each, but were written in several steps, which are orientated on Rauh’s Aisthetic Fieldwork. However, as a difference to Rauh’s method, all of the field notes were taken in retrospect, as they took place as an exploratory attempt to learn about tranquility and were not yet planned to be turned into this specific format. First, detailed notes on impressions and affects were written down shortly after the experiences and stepwise filled out with more memories. The full texts were written after a process of repeatedly formulating and prioritizing field notes.

Accordingly, in consideration of the limited space within the thesis format, the micrologies are shortened and less extensive than Hasse’s examples. Due to the consideration of atmospheric experience as an interplay between perceptual habit and atmosphere within this work, the

19 subjectivity of the account is reflected in a style of writing which attempts to transport the very moments of affect and their subjective impact in a contextual and personal manner.

Knowing through

Finally, a summarizing aim of this work is to gain a further understanding of tranquility through the notion of atmosphere, by applying a radically subjective, personal and emotive frame of analysis. Whilst most of the empirical studies on atmospheres have been employing an ethnographic methodology of observation and interviewing of a set of persons with regards to their perception and interpretation of different atmospheres (Bille, 2015; Bille, 2015; Buser, 2016; Rauh, 2017; Schroer & Schmitt, 2017), deeper phenomenological or experiential accounts remain exceptions. By applying atmospheres both as a theoretical and as a methodological framework, the aim of this work is to add new angles to knowledge on tranquility, bringing forward the establishment of a research branch.

20

5. Experiencing Spaces for Tranquility

Two cases in the city of Malmö were chosen for the following analysis: Tyst Off the Work5, a silent after-work event in the multifunctional Studio building, and a Vilrum, a “room for resting”, within the

Niagara building of Malmö University. They were selected on the grounds of their clearly

communicated function for tranquility through both their naming and their official description, which is elaborated on in the description of the places.

Both share a specific urban planning context. Laying only 400 meters away from each other and having opened in 2015 and 2016 respectively, both Niagara and Studio form part of the newer developments in the university area Universitetsholmen in the northwest of Malmö. Universitetsholmen has been under heavy redevelopment since the 2000s under the influence of the strategy around the 4th Urban Environment, which in turn is intended to act as

“a space between the public and private environment, a new hybrid environment in the city structure – […] a result of a fundamental need for innovation and renewal in businesses and institutions, in communities and society” (City of Malmö, 2009:168).

Especially Studio’s function is communicated as a public-private Meeting Point6 (Skanska Sverige

AB, 2016), therefore fitting into the 4th Urban Environment concept. An atrium at the ground floor serves as a public square, surrounded by private offices and other companies. Public-private Meeting Point concepts as a way to create spaces for the creative class serve as a tool of implementing urban development from Malmö’s industrial past into a knowledge city. The trickle-down argument, as well as entrepreneurialism as a city marketing tool and the intentional blurring between public and private space have been main principles leading the municipality’s decision-making along the process of transition, reflecting a neoliberal planning ideology (Listerborn, 2017).

Contextualizing the location as part of the knowledge city strategy and 4th Urban Environment concept is insofar relevant for the analysis of spatial arrangements in design and their spatially discharged atmosphere, as Universitetsholmen is one of the most prominently redeveloped areas in the course of Malmö’s transition to a post-industrial city. Therefore, the interpretation of atmospheres should consider the influence of the radical recent changes in the area.

This chapter is divided into two parts, standing for the two presented cases. Each subchapter begins with a general description of the background in which the place materialized and how it is described by its representatives, its location, material qualities, how and when the place was accessed and other particularities, e.g. communicated rules of behavior. The introductory information about the place is followed by a micrological vignette, catching the situation and spatial arrangement as affectively perceived. As a third step, each micrology is interpreted in the context of atmospheric notions and the previously given contextual information.

5

“Silent Off the Work”, if translated into English 6 Referred to as mötesplats in Swedish

21

Tyst Off the Work

The first case is an event series called Tyst Off the Work, an after-work7 concept organized by the company Off the Work AB8 that took place nine times throughout 2018 with durations around 2

hours each. The title is a mixture between Swedish and English components, namely tyst, the Swedish word for silent, and Off the Work, an alternative naming for after-work. The participation was free of charge, “open to everyone” (Off the Work AB, 2018c) and required the registration on an online form with the full name and e-mail address, affiliation with a company or organization, telephone number and profession or working field. Within the online registration form, in case of registering and not participating without cancelling the registration within 24 hours before the event, a no-show fee of 200 Swedish Kronor would apply.

In the promotional video, the intention of the event is described as follows:

“Our purpose is to create a setting that is free from efforts, achievements and consumption, where you can participate without the pressure to perform […] Just as our bodies need exercise, we need to exercise our minds to feel good. Doing so in silence gives your brain the opportunity to wind down, and recover on a deeper level.” (Off the Work AB, 2018b)

Whilst the visited event was free of charge, the same page pointed out that a silent after-work can be booked as a paid service for companies. One section on the website named research lists several newspaper articles and some journal articles about medical and psychological correlations between silence and brain health, stress and the burn-out syndrome, and negative health impacts of excessive use of smartphones and social media (Off the Work AB, 2018a).

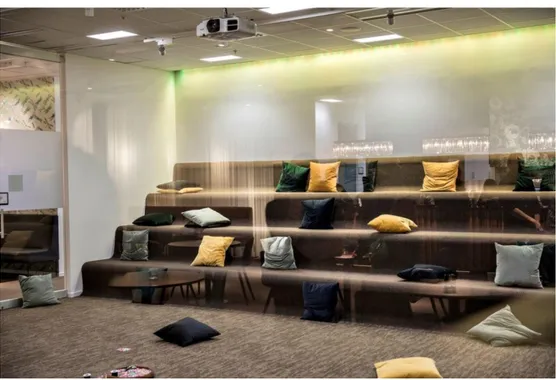

Figure 1. Photograph of the Tyst Off the Work location (El-Alawi, 2018).

7

„After-work“in this context refers to designated activities or social events taking place immediately after working hours and attended with coworkers. It is a very common practice in Malmö and mostly entails the visit of bars or other festive activities.

22 The event took place in an enclosed glass construction of 68m² size within an open plan co-working office called United Spaces (see figure 1). The co-working space in turn is located within the Studio building.

I participated February 15th 2018 at 4pm, together with a study colleague. When entering the co-working office, the participants were asked to confirm their names on the registration list, to turn in bags, jackets, technological devices, clocks, books or similar objects at the entrance, and to take off their shoes before entering the glass room.

The whole room was carpeted as well as provided with pillows and a bowl filled with beads, standing on the floor. Apart from the floor, there were four “steps” on which it is possible to sit or lay. As the room’s walls were made out of glass, the room offered a view into the surrounding office space. At the beginning of the event, a woman explained the following rules: the participants are expected to not talk, to try to make as little sounds as possible and to not look into each other’s eyes. Additionally, she advised to try not to think and preferably not to fall asleep. If one would fall asleep and snort, one would be woken up.

Vignette: Silent Theater

We rushed to the place and even though we already arrived, an abstract feeling of hurry still resounds within me. The entrance of the co-working space looks like the entrance lobby of a hotel, or just a quite elegant version of an open-plan office. “You are late” the woman standing at the entrance of the glass room says with annoyance in her voice. “Take your shoes off”. The comment does linger a bit over my mood when going in, as I feel slightly exposed and ashamed.

We quickly sit down on one of the steps and the woman who has let us in begins to give instructions for the activity. Wow, so many things we are not supposed to do. But I want to test the experience and see what happens. After giving the instructions, she adds that a photographer employed by the municipality was invited to take some photos and film us during the session. “If somebody absolutely

doesn’t want to be filmed, please let us know now”, she says.

Being filmed feels counterproductive to relaxing to me; I generally don’t like to be photographed or filmed by persons I don’t know, as I feel that I would need to pose; should I say something? I hesitate. Then, I decide to remain silent, as I don’t want to complicate things or get into the way that she seems very convinced of.

The silent after-work begins. Ambient music is turned on, and the sounds feel soothing. I begin to let my gaze wander and look around, at the ten persons sitting dispersed in the room and outside of the glass box into the empty working space with its unused tables and chairs. Apart from my colleague, I don’t know who the participants are, I have never met them before; and I am curious, but try to not look them into the eyes, remembering the rules. In the first moments, some people accommodate their positions, leaning back, crossing the legs and stretching out.

One blonde middle-aged man is sitting next to me; he closed his eyes and smiles, seems comfortable. He is quite well dressed, the casual-but-expensive-looking type of well dressed, like most of the people in the room. The group of persons seems relatively homogenous in terms of age and appearance, and I feel like my colleague and I are standing out – not extremely, but notably. For a short moment, I wish I had chosen to wear something a bit different today, maybe more proper, but I

23 quickly let the thought go. I look down to the floor and see another man, maybe around 30, emptying the beads from the bowl onto the floor and beginning to sort them by color. A woman walks to the middle of the room and lies down, closing her eyes. Most of us are sitting and some remain with their eyes open and look around, like me. After observing for a while, I decide to focus more on relaxing and trying to ease into a meditative mood, indecisive where to look and finally focusing my vision onto one spot in the office.

I can see from the corner of my eye how the photographer is moving and taking pictures from different angles. It does feel uncomfortable and I begin to think about where this material is going to end up. “Just focus on relaxing!” I think again, trying to disconnect my thoughts from the photographer and reconnect them to the spot that I have been focusing on.

Slowly, the thoughts settle down and move into the back of my mind. I listen to the music and focus on breathing, feeling a sense of relief about the relative silence and a conscious break from phone or computer displays. Some time passes by; it is hard to say how much. Ten minutes, twenty? As there are no clocks in the room, I don’t know. The man next to me changed position but still smiles with closed eyes. The man on the floor is still sorting beads. The woman is still lying on the floor. My colleague is staring down. The photographer left. I notice how I am more relaxed when I keep staring into this one particular dark corner, ignoring the presence of the other participants. The social setting weighs on me – not heavily, but I feel a clear sense of not-belonging-here that is hard to shake off. I begin to analyze again.

Why does it feel like a performance? I try to locate where the uneasy, stiff feeling comes from. It is not my first exercise in being silent; I had tried several yoga and meditation practices before. It is not the same resounding restlessness of moving from a busy mind to silence that I feel now, it is something else. The photographer left but it feels like we are still trying to relax in order to prove each other amongst strangers that we can relax. It feels like an exercise that will be graded and everybody wants to get an A from the organizer or the woman who explained the rules. I know that I don’t know anybody’s thoughts or feelings in this moment, but this moment resembles sitting on a theater stage, and the man who smiles with the closed eyes has to stick to his role, just like bead guy has to stick to his role, and we as a group have to play the role of the contempt silence-enjoyers. After this moment of realization, I fall into an apathetic mood, looking at my feet, the floor, the glass walls, the composition of the room, letting my mind wander to the plans for the rest of the day. I turn to my colleague and our eyes meet, exchanging a quick nod indicating that we are both ready to go. We leave the glass room, put on our shoes and pick up our bags at the reception. Whilst handing us our bags, the employees of the co-working space explain that they are renting out seats in the office and offer us business cards, in case we want to become members. My urge to leave the place becomes stronger. We take the cards and leave the office, walking to the main entrance of the building with a sense of hurry.