From Loyalty to

Disloyalty

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Marketing AUTHOR: Nikolov, N., Gonzalez, J.P. JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Exploring negative consumer-brand relationships in

social media

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title:

From Loyalty to Disloyalty: Exploring Negative Consumer-Brand

Relationships in Social Media

Authors:

Nikolov, Nikolay; Gonzalez, Juan Pablo

Tutor:

Ahamed, AFM Jalal

Date:

2020-05-17

Key terms: consumer-brand relationships, brand loyalty, loyalty loop, disloyalty, brand hate,

brand abandonment

Abstract

Brand loyalty has been studied extensively in consumer-brand relationship literature. However, the negative side of these relationships has not been studied to the same degree. This paper starts with Court et al.’s (2009) loyalty loop as part of the consumer decision journey and proposes that consumers may stop being loyal to a brand due to various circumstances.

The authors propose a negative view of the loyalty loop, the disloyalty loop, exist, in which consumers become disloyal. Furthermore, the authors conducted this study in order to find out if this relationship exists, the disloyalty loop, within the framework of social media platforms, i.e. applications who allow communication among users over the Internet. These platforms should not solely be seen as online communication tools, but as brands themselves. Semi-structured interviews with social media users were conducted showing that consumers can navigate between the loyalty and disloyalty loops, and even exit the brand relationship completely. These findings indicate that consumers’ brand loyalty should not be taken for granted, and service failures may cause them to reduce their patronage, abandon the brand, and even influence other consumers negatively through word-of-mouth.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study would like to thank first to our lecturers and tutors that have been with us along the Master’s programme in International Marketing journey, as well as to the staff of the Jönköping University to provide and facilitate an amazing educational and life-time experience. We also want to thank to our Master Thesis Tutor, Dr. Jalal Ahamed from the University of Skövde for his guidance so that we could materialize and ground our idea. Finally, we want to express our gratitude to Professor Joseph Bamber and Professor Dr.

Julio Rivas from the Lipscomb University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA for their support with their expertise, advice, and contributions to materialize this work.

I, Nikolay, want to thank my mother Silvia for her motivation inspiring me to take on this challenge, and my father Anton for the continued support and belief through the years. Likewise, I would like to thank my girlfriend Tatiana for the fruitful conversations and patience throughout this process.

I, Juan Pablo, want to thank my mother Olivia for her understanding, for never letting me down, and for always being there. To my father Enrique, for his unconditional love and support, as well as to my brother Julio Enrique for being the best brother I could ever asked for.

Contents

... 1

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1

Background Description ... 1

1.2

Purpose ... 2

1.3

Localization to Social Media ... 3

1.4

Research Questions ... 4

1.5

List of Definitions ... 4

1.6

Delimitations ... 5

1.7

Contribution to existing literature... 5

2.

Literature Review ... 5

2.1

Brand ... 6

2.2

Brand Loyalty ... 6

2.3

Consumer Decision Journey & The Loyalty Loop ... 7

2.3.1

Empowered Consumers ... 7

2.4

Consumer-Brand Relationships ... 8

2.4.1

Understanding Consumer-Brand Relationships ... 8

2.4.2

Hogg’s Model of Anti-Constellations ... 9

2.5

Brand Hate ... 9

2.6

From Loyalty to Disloyalty Loop ...12

2.7

Stages of the Disloyalty Loop ...13

2.7.1

Disappointment ...13

2.7.2

Frustration ...14

2.7.3

Separation ...14

2.7.4

Revenge ...15

3.

Methodology ... 16

3.1

Area of Study & Data Collection ...16

3.2

Research Philosophy ...17

3.3

Type of Study ...17

3.4

Reasoning ...17

3.5

Research Strategy...18

3.6

Method of Data Collection ...19

3.7

Interview Design ...20

3.8

Interview Process & Analysis ...21

3.9

Sampling ...22

3.10

Data Quality ...23

3.11

Ethics ...24

4.

Results ... 24

4.1

Demographic data ...25

4.2

Social Media Use ...25

4.3

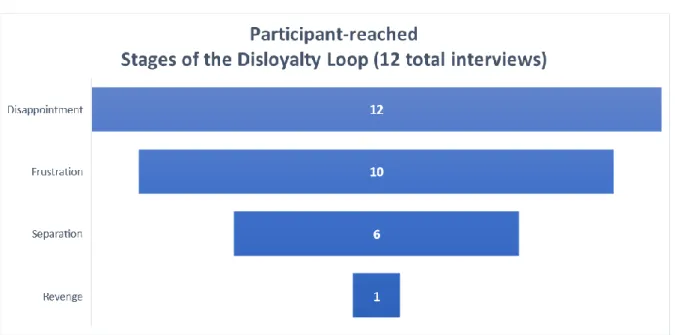

Stages of the Disloyalty Loop ...26

4.3.1

Disappointment ...26

4.3.2

Frustration ...27

4.3.3

Separation ...28

4.3.4

Revenge ...28

5.

Analysis ... 29

5.1

Answering the Research Questions ...30

5.1.1

Can Consumers Exit the Loyalty Loop? ...30

5.1.2

Does a Disloyalty Loop Exist? ...31

5.1.3

Mapping the Stages of Brand Disloyalty ...31

5.2

Theoretical Implications ...36

5.3

Managerial Implications ...37

6.

Conclusion ... 38

7.

Limitations ... 39

8.

Future Research ... 39

9.

Reference list ... 41

Figures

Figure 1

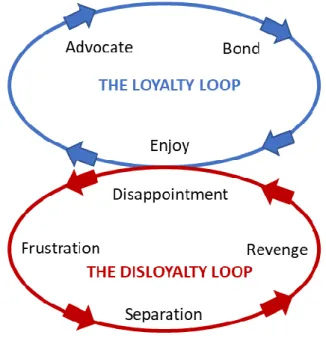

The Loyalty Loop (Court et al., 2009) and the Disloyalty Loop ...12

Figure 2

Participant-reached stages of the disloyalty loop ...26

Appendix

Appendix 1 ...46

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The introduction offers a presentation of the background description and problem formulations. It also outlines the motivation for the study, its aims, research questions, and contribution to existing literature.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1

Background Description

The relationship between consumers and brands has long intrigued marketers (Day, 1969). Much academic work has been done on the issue of the positive side of the consumer-brand relationship, such as brand loyalty, brand preference and brand love (A. Shivakanth Shetty, 2018; Aaker, 1991; Batra, Ahuvia & Bagozzi, 2012; Dick & Basu, 1994; Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978). The bulk of academic papers deals with the topic of consumers repeatedly buying a certain brand, and the emotional and psychological triggers behind these processes. This is understandable from the corporate perspective – companies want to understand their consumers, how to market to them and how to encourage consumer behavioural patterns in their favour (Dalli, Romani & Gistri, 2006).

Up until two decades ago, few studies had attempted to explore the dark side of consumer behaviour – when consumers choose to misbehave and break the patterns and observations marketers have spent so much time outlining (Hogg, 1998). There has been growing interest in exploring the negative consumer-brand relationship – anti-choice and abandonment (Hogg, 1998; Hogg, Banister & Stephenson, 2009), brand avoidance (Lee, Motion & Conroy, 2009), brand dislike (Dalli et al, 2006), and brand hate (Zarantonello, Romani, Grappi & Bagozzi, 2016).

The research in this field concentrates on the relationship between consumer and brand. These relationships are often similar to interpersonal relationships, as brands can be assigned personal attributes, and become thus, an active partner (Fournier, 1998; Fournier & Alvarez, 2012). Therefore, much of consumer behaviour may be influenced by affection towards a brand, and emotion instead of cognition. Additional studies point to the dynamics of consumer-brand relationships, their ability to deteriorate, and the moderating effects of the behaviour of the brand (Aaker, Fournier & Brasel, 2004; Fajer & Schouten, 1995). These indications lead to the effective consideration of consumer-brand relationships to interpersonal relationships as equivalent (Dalli et al, 2006).

In the current era of digitalization consumers do not only receive messaging from brands through the traditional channels – print, radio, and television (Court, Elzinga, Mulder

& Vetvik, 2009). Living in an interconnected world that is in constant communication means the opportunity for marketers to reach their audience are virtually endless. Consumers have a wealth of information available at any moment at their fingertips, and can dissect every considered alternative, transforming the traditional buying decision journey (Court et al, 2009). This also provides the opportunity of influencing other consumers’ brand relationships more profoundly than ever.

The traditional marketing approach of both theory and practice has been skewed towards positive consumer-brand relationships (Dalli et al., 2016). While this opens the door to positive influence, it also enables consumers to develop a negative attitude toward a brand, which could have significant consequences (Hogg, 1998). Consumers could have a negative experience with a representative of the brand, they could react negatively to an advertising piece, or a public relations announcement, engage with negative word-of-mouth online through blogs posts, videos, forums, or social media posts. These negative experiences could make the consumer feel disconnected from the brand, and therefore, fail to identify themselves with it (Hogg, 1998). This could lead to a reduction in patronage and altered purchase behaviour, halting consumption, or, if the disconnect is so great that the consumer believes the brand fails to live up to its promise or it has failed to satisfy the consumer needs, actively recommending other consumers to avoid the product through negative word of mouth (Zarantonello et al, 2016).

Court et al. (2009) carefully studied the consumer decision journey. By analysing consumers from various industries, they proposed a model of the steps consumers taking when evaluating and purchasing a brand. Their research proposed a model of repeat patronage, named the loyalty loop, in which satisfied consumers become increasingly loyal through their consumption (Court et al, 2009). The study found two variations of this phenomenon – active and passive. Active loyalists were likely a stronger attachment to the brand, having a positive association with the brand, and advocating for it. However, another group of consumers continued to exhibit loyalty, but were also open to the communication of other brands.

These findings propose a series of fascinating questions. Are consumers consistently loyal? What could turn them away from their beloved brand? What lies outside the loyalty loop? Is there a way back to brand loyalty? Could a brand lover turn to a brand hater? Does a mirror loyalty, or rather, disloyalty loop exist, which drives consumers further away from a brand, instead of closer to it as in the case of the loyalty loop?

1.2

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to explore whether the possibility of consumers can fall into a so-called disloyalty loop as a devolvement of the consumer-brand relationship is a plausible scenario. First, the authors aim to understand whether consumers can exit the

loyalty loop. Furthermore, the connection between loyalty and disloyalty is to be studied by searching for the existence of a mirror loyalty loop, dubbed “the disloyalty loop”. Finally, this study will attempt to clarify how consumers navigate this unchartered territory of brand disloyalty, and whether there is a path back to the loyalty loop.

We claim that during this study, the reader will gain insights into the dynamics of consumer-brand relationships and the interplay of loyalty and disloyalty in that context. To support our argumentation, the specific methods of data collection will be outlined in order to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the efforts made in the search for evidence for or against the existence of a disloyalty loop in the framework of social media. The following results and analysis could contribute to the generation of future research within the field and potentially practical managerial insights.

1.3

Localization to Social Media

To explore this subject, the authors felt the need to select an industry, in which consumers could seamlessly interact with a brand, with virtually no restrictions, barriers, or even costs. For the means of exploring the consumer-brand relationship the authors focus on a segment that due to its technological characteristics has become virtually omnipresent all over the world, and to which consumers have developed different levels of emotional commitment.

Social media has been rapidly expanding and growing in number of users and popularity becoming an integral part of daily connected life. A social media platform is defined as an application or network that allows users to communicate with each other through the Internet (Law, 2016). While it can be argued that social media has revolutionized the way people get in touch with each other and with organizations, as well as the manner in which communities are built around a brand, users may still find further ways of transportation across the virtual communication oceans. While ships revolutionized and dominated intercontinental transport for centuries, the appearance of a more sophisticated transport technology in aeroplanes changed the way transoceanic transport was conceived (Gensler, Völckner, Wiertz & Yuping, 2013).

An estimate of 3.5 billion people around the world use social media, amounting to nearly half of the global population (Kemp, 2019). The omnipresence of social media platforms acquires a relevance for marketers since consumers are able to communicate not only with other users, but also with other brands (Bacile, Hoffacker, & White, 2014).

Therefore, a deeper understanding of consumer-brand relationships in this context may offer valuable insights for the phenomenon in general.

Social media platforms have largely not been explored as brands that consumers interact and have relationships with. Most frequently, social media platforms are studied as a communication platform for other brands to engage with consumers; instead, the authors propose an analysis of social media platforms as an actor in the consumer-brand relationship. Thereby, this study aims to contribute to the academic body of knowledge through the exploration of brand loyalty and its opposite, brand hate. An alternative model to the loyalty loop (Court et al, 2009) is offered in the face of the “disloyalty loop”, exploring the consumer decision journey outside of the established marketing perspective.

1.4

Research Questions

The research questions of this study are formulated below:

1. Can consumers exit the loyalty loop?

2. If the consumer can exit the loyalty loop, is there a negative, or mirror loyalty

loop (disloyalty loop)?

3. If a disloyalty loop exists, what are its stages, and how do consumers navigate

them?

1.5

List of Definitions

Brand - a tool to differentiate a company’s products and services from those of its competitors (American Marketing Association, 2006).

Consumer-brand relationships – a dynamic interaction through which consumers may develop strong association and emotional connection with a brand (Aggarwal, 2004; Fournier, 1998).

Brand loyalty - consumer support for a brand as a result of satisfaction (Law, 2016).

Brand hate – a desire to avoid or hurt a brand (Gregoire, Tripp & Legoux, 2009). Loyalty loop – a cycle in which consumers buy the same brand to express brand preference (Court, Elzinga, Mulder & Vetvik, 2009).

Disloyalty loop – a cycle in which consumers become enact brand hate and become increasingly negative toward a brand.

Social media platform – an application or network that allows users to communicate with each other through the Internet (Law, 2016).

1.6

Delimitations

This study finds its boundaries within the framework of the brand loyalty loop (Court et al., 2009), whether consumers can navigate outside of it, and its proposed potential negative, the brand disloyalty loop. This research paper does not intend to study cause-effect relationships due to the novelty and uncertainty surrounding the existence of the proposed phenomenon. As mentioned, this area of research regarding disloyalty towards brands is largely unexplored, limiting the availability of existing literature to facilitate a feasible deductive approach. The theoretical conceptualization of brand loyalty or brand hate will not be explored. The stages of the brand loyalty loop will not be studied in detail; instead, the authors will see the loyalty loop as a unitary moment in the consumer-brand relationship, while dissecting the proposed stages of the disloyalty loop.

1.7

Contribution to existing literature

This paper aims to offer an alternative perspective to the established framework of consumer-brand relationships, in which consumers can navigate outside of the brand loyalty loop, and alternatively, follow a different course heading to the proposed brand disloyalty loop. This effort seeks to contribute to the existing body of literature through the exploration of consumer experiences with brands, and the consequent attitudes and emotions developed through the interaction. Finally, the study is localized in the context of social media, providing the different platforms the characteristics of consumer brands, which have not been researched to the same extent as traditional ones (Dalli et al., 2016). The authors of this study also consider it relevant within the context of international marketing, due to its exploration of attitudes to global social media brands with respondents from multiple nationalities, residing in varying parts of the world, with different educational levels, and occupational characteristics.

2. Literature Review

________________________________________________________

This chapter offers an overview of the existing research on consumer-brand relationships, brand loyalty, brand hate, and Loyalty Loop. It finally outlines the author’s proposed model of the Disloyalty Loop and its constituents.

______________________________________________________________________

To conduct an adequate review of the existing literature of consumer-brand relationships, the authors synthesized information from a variety of sources, including journals, books, articles. Databases used include ScienceDirect, EBSCOhost, and ProQuest, accessed through theJönköping University digital library. Among the most frequently used terms were consumer-brand relationships, consumer-brand loyalty, consumer-brand hate, social media, anti-consumption, consumer disappointment, consumer frustration, brand abandonment, and brand revenge.

2.1

Brand

A broad array of definitions of the term brand exists (Strizhakova, Coulter & Price, 2008), a brand is generally defined as a tool to differentiate a company’s products and service from those of its competitors (American Marketing Association, 2006). In regard to the functions it fulfils in society, it may instead be described as a constellation of multiple dimensions (deCharnatony & Dall’Ormo Riley, 1999). Keller (1993) states that consumers perceive brands as a network of associations and establish a certain equity to the brand that can be classified as either positive or negative (Berry, 2000).

2.2

Brand Loyalty

According to the Oxford’s “A Dictionary of Business and Management”, brand loyalty is defined as consumer support for a brand as a result of satisfaction (Law, 2016). It is expressed as a preference and adherence to the brand, accompanied by a reduction of the likelihood of switching to a competing brand despite promotions or other marketing activities. Early definitions of brand loyalty focused solely on repeat patronage - as early as 1969, George Day described brand loyalty as repeated purchases due to an internal preference for the brand (Day, 1969). Consequently, the disposition of the consumer was considered an important element to the concept (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978). Day (1969) also found that many consumers were influenced by opportunity (campaigns, attractive deals) and habit, and thus swayed from their preference. Jacoby and Chestnut (1978) expanded the concept of brand loyalty by arguing that commitment is one of its critical elements, thus differentiating between repeat buying due to inertia and conscious purchase of the preferred brand. The observed phenomenon was defined as “the biased, behavioural response, expressed over time, by some decision-making

unit, with to one or more alternative brands out of a set of such brands, and is a function of psychological decision making, evaluative processes” (Jacoby, 1971, p.2).

In 1994, Alan Dick and Kunal Basu went further in the study of the concept of customer loyalty, aiming to create a framework that would measure the concept. They built on the existing research (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978), and introduced an alternative perspective of

the concept -one, which is based on the relationship between the consumer and the brand.

The intersection of cognitive (accessibility, confidence, clarity), affective (emotion, mood), and conative antecedents (switching costs and expectations) results in a relative attitude of the consumer towards the brand (Dick & Basu, 1994).

2.3

Consumer Decision Journey & The Loyalty Loop

McKinsey published an article with a novel term in 2009 that would change the way academics and business professionals look at the buying decision process (Court et al, 2009). Basing their work on consumer studies of 20,000 consumers in multiple industries, they challenged the conventional view, in which the consumer starts off with several brands in mind, which they get familiar with, evaluates the benefits and drawbacks of all the alternatives, and finally purchase from one of them, which could hence lead to loyalty. Court et al. (2009) had a different perception of the buying decision observing that contemporary consumers are well-informed and may interact with a brand not just in a store or through an ad, but through a plethora of touch points via the internet. Hence, the funnel approach was no longer to contemporary consumer-brand relationships; instead, they named it “the consumer decision journey”.

Once the authors re-imagined the process as a more circular route instead of the linear funnel approach, the customer decision journey took on a different shape and flow (Court et al., 2009). Firstly, a trigger or need forces the consumer to begin considering a brand or product. In the second stage, they actively evaluate their alternatives. Notably different from the funnel model, at this stage consumers may add brands to their consideration, rather than the same number of brands as in the initial stage. Subsequently, the customer makes their decision at the moment of purchase choosing one of the brands and evaluates their experience with that brand. If that experience is positive, the consumer may choose to purchase from the same provider again, falling into a “loyalty loop”, where they express their brand preference and loyalty through repeat buying (Court et al, 2009).

Brand awareness plays a crucial for brands in the consumer decision journey – the study showed that brands that were considered in the initial consideration stage were three times as likely to be purchased compared to those who entered later (Court et al., 2009). However, brands could enter the consumer’s mind at a further stage, even forcing the exit of some previously considered brands and ultimately being purchased. Additionally, this finding suggests the possibility of brands being removed from the consideration phase in a range of different manners (Court et al., 2009).

2.3.1 Empowered Consumers

Traditional marketing focused on push communication – trying to convince the consumers to purchase their product (Court et al, 2009). However, contemporary consumers draw in a lot of information themselves, demanding to know more about products, brands, and services, and generating a pull from the company. This presents a challenge to brands, who are faced with an altered consumer profile compared to the one the marketing funnel was tailored to. The modern informed consumer still communicates with the brand and the

point-of-sale store staff, but they also consult their peers often, reads reviews online and in print publications (Court et al., 2009). Especially in high-involvement purchase decisions, the consumer is willing to evaluate brands for longer periods, months on end, gathering as much information, opinions, and specifications as possible before they make their purchase decision

The previously mentioned study finds two types of brand loyalty – active and passive (Court et al., 2009). It describes active loyalty as repeat buying and positive word-of-mouth, a willingness to recommend the brand to others. Conversely, passive loyalists claim to be loyal to a brand, and will still purchase it, but are in fact open to competing brands (Court et al, 2009). They go on to state that brands should constantly strive to expand the base of active loyalists, both by adding new consumers to the group and by converting passive ones. This also translates to an opportunity to address passively loyal consumers, who are not being converted by their preferred brand. They are the potential actively loyal consumers of a brand who can convince them to switch and consistently give them reasons to stay. The resultant dichotomy between active and passive loyalty overlaps with Aaker’s definition of brand loyalty as an attachment towards the brand, instead of the likelihood of switching to a competing one (Aaker, 1991).

Court et al. (2009) also discuss the tendency of traditional marketing to either focus on building brand awareness or converting the consumer to make the purchase in the final stage. Despite the former, they argue for an integrated marketing strategy, which communicates with the consumer at all possible stages of the consumer decision journey. Communication might take place following a purchase to re-confirm the consumer loyalty to the brand, or the trusted brand could act as a close advisor recommending a product before the customer even realizes they need it (Court et al., 2009). The brand also has a significant opportunity to influence consumers in the direction of promoting positive word-of-mouth, thereby influencing peers. Active loyalists can influence considering consumers in favour of one brand and dissuade them from another (Court et al, 2009). It is vital that the brand be consistent across all touch points with the consumer – instore, on their webpage, on retailers’ webpages, in their online and print ads, in their customer relationship management communication and so on. The aforementioned finding is also considered highly relevant in the case of this study as the consumers experience not only what the social media platform communicates, but also what its users publish on it.

2.4

Consumer-Brand Relationships

2.4.1 Understanding Consumer-Brand Relationships

The field of studying interactions between brands and consumers has been undergoing rapid development in the preceding two decades. Susan Fournier (1998)

pioneered this progress by proposing that consumers perceive brands much like they perceive people. They develop meaningful relationships with them and may exhibit powerful emotions such as love (Batra et al., 2012) and hate (Zarantonello et al., 2016). They can choose to forgive the brand’s service failures (Donovan et al., 2012), end their relationship (Hogg, 1998) and avoid their ex-brand (Lee et al., 2009). Moreover, the same principals of community and exchange are applicable to brands as are to interpersonal relationships (Aggarwal, 2004; Aggarwal & Law, 2005).

The consumer-brand relationship may be described as a dynamic interaction, where both parties contribute to the development or detriment of the relationship. This study examines the cases in which the relationship turns from love to uncertainty and disaffection. The study of existing literature of negative consumer-brand relationships can provide a solid underpinning to a mirror model of the disloyalty loop.

2.4.2 Hogg’s Model of Anti-Constellations

One of the milestones in the field of consumer-brand relationships was set by Margaret Hogg (1998). She studied the motivations behind consumers’ decision to give up consumption of certain products and brands. The results became the base of her model of anti-consumption constellations, which divided the concept into non-choice, which were goods outside the means of the consumer, and anti-choice, whereby the consumer actively did not choose the brand due to an incompatibility with their beliefs or other consumption preferences (Hogg, 1998). The model later expanded in order to include avoidance, aversion and abandonment as the embodiment of anti-consumption (Hogg et al, 2009). This study gave rise to a rapid expansion within the field, with brand hate (Gregore, Tripp & Legoux, 2009) and brand avoidance (Lee, Motion & Conroy, 2009) emerging shortly thereafter. Based on Hogg’s previous research (1998; Hogg et al., 2009), Suarez and Chauvel (2012) defined brand abandonment as the process of consciously halting the consumption of certain product or service.

2.5

Brand Hate

On the other end of brand loyalty (Aaker, 1991) is brand hate (Zarantonello et al, 2016). Brand hate was first conceptualized by Gregoire, Tripp and Legoux (2009) as a dual-sided reaction characterized by a desire to avoid the brand and a desire to hurt the brand. A service failure by the brand may cause the consumer to take a passive or active attitude in addressing their grudge toward the brand. Avoidance becomes a way for the consumer to escape the brand halting or decreasing their purchasing of the brand, and so avoid further damage. Furthermore, a desire for revenge may drive the customers to complain (Bonifield & Cole,

2007), spread negative word of mouth (Gregoire & Fisher, 2016), and take their gripe with the brand public through online media (Ward & Ostrom, 2006).

Consumers are less likely to maintain their desire for revenge over extended

periods of time as actively hurting the brand requires energy, deliberation and leads to no material gains, ultimately becoming too costly to maintain (Gregoire et al., 2009). Instead, the authors state that consumers will avoid the brand because brand relationships are easily replaceable (Aggarwal, 2004). Should the consumers choose to complain about their negative experience, they will not see their relationship with the brand as they did prior to their disappointment, and their desire for avoidance will increase as it requires less commitment than the desire for revenge (Gregoire et al., 2009).

The authors also made some notable discoveries in terms of how different

consumers react to disappoint, and which types are most likely to be susceptible to brand hate. Their study revealed that the most committed and loyal consumers felt most betrayed when they experienced a service quality (Gregoire et al, 2009). Having established a relationship with the brand, they had built trust in its ability to meet their needs and the positive experience of being associated with it. When the brand failed to match their needs, the most loyal consumers felt most violated, resulting in the highest desire for revenge among all consumers (Gregoire et al, 2009). Additionally, the feeling of betrayal was found to be sustained over long periods of time.

Gregoire et al. (2009) also discovered that an attempt by the brand to recover a

consumer, which had gone from brand loyalty to brand hate, is better than no attempt. This became evident in the case of desire for revenge, where the brand could effectively neutralize the harm. However, no significant effect on those who just wanted to avoid the brand was observed – they were not swayed by the contact in either way. Their findings suggests that companies should do their best to establish a stable channel of communication with their detractors and attempt to relieve their disappointment, hopefully even reversing their negative opinion of the brand (Gregoire et al., 2009).

Brand hate was later defined as “an intense negative emotional affect toward the brand” by Bryson, Atwal & Hulten (2013, p.395). Their view underlines the dynamic two-sided interaction between consumer and brand in the relationship, as well as the ability of the consumer to experience powerful emotions in this setting. Additionally, the finding further confirms that consumer-brand relationships are not all that different from interpersonal relationships (Dalli et al., 2006; Fournier, 1998; Fournier & Alvarez, 2012).

The concept of brand hate was also extensively studied by Zarantonello, Romani, Grappi & Bagozzi (2016). They approached the subject in a novel manner choosing to focus on the complete set of brand hate emotions, instead of only one or several as previous researchers had done. Building on existing literature, they conducted two studies to better understand the relationship between the individual emotions that lead to brand hate, and behavioral outcomes.

Zarantonello et al. (2016) created a model to express the factors leading to brand

hate. Based on thirty-eight emotion descriptors, the authors established six factors – contempt and disgust, anger, fear, disappointment, shame, and dehumanization. Furthermore, a second model was constructed where the first two were dubbed as “active brand hate” due to those emotions being classified as active in the psychology literature, and the remaining were grouped into “passive brand hate” (Zarantonello et al., 2016).

The authors defined three paths towards brand hate with three starting points –

corporate wrongdoings, violation of expectation, and taste system (Zarantonello et al., 2016). The first is characterized by the brand acting in a manner that seems unethical, unfair, or simply wrong to the consumer. Violation of expectation can be equated to a service failure, or disappointment. Finally, taste system refers to a negative brand image, or a mismatch between the brand image (Zarantonello et al., 2016) and the character of the consumer, similar to one of the types of brand avoidance that Lee, Conroy & Motion (2009) defined. Similar to the analysis of Gregoire et al. (2009), the authors concluded that brand hate results in two manners – “avoidance-like”, which was defined by a reduction of patronage, and “attack-like”, expressed as negative word-of-mouth. In addition, a third coping mechanism was discovered, “approach-like”, measured as “consumer complaining and protest behaviours” (Zarantonello et al, 2016, p.21).

The consequences of overall brand hate, both active and passive, were

subsequently analysed to assess their relation to behavioural outcomes. The findings show that the phenomenon can lead to one of four outcomes – complaining, negative word-of-mouth (nWOM), protest, and patronage reduction or cessation (Zarantonello et al., 2016). Corporate wrongdoings were the strongest influencing factor of the ones studied, with it leading to the highest level of brand hate of the three drivers, and higher levels of all behavioural outcomes. Violations of expectations led to higher levels of complaining, negative WOM, and protest, corresponding to the “attack-like” and “approach-like” strategies described above (Zarantonello et al., 2016). The final strategy, “avoidance-like” was characterized via the term “taste system”, where consumers choose to passively reduce their patronage of the brand but wish to take no harmful action against it.

2.6

From Loyalty to Disloyalty Loop

The Customer Loyalty Loop explores the cyclical nature of the positive relationship between brand and consumer. Using this framework as a base, we propose a mirror version, dubbed “The Customer Disloyalty Loop”. As the Customer Loyalty Loop is based on the concept of brand loyalty, we will base our working model of the Disloyalty Loop on brand hate. Zarantonello et al.’s (2016) study provides a stable ground for analysis of the emotions consumers experience when falling out of love with a brand. Furthermore, the concepts of active and passive brand hate are fully applicable in the consumer journey of being disappointed, complaining, abandoning, avoiding and desire to take revenge on the brand. They also explore the behavioral outcomes of the fall-out – reduction of patronage, negative word of mouth, complaining, etc. Therefore, the six factors used by Zarantonello et al. (2016) – contempt and disgust, anger, fear, disappointment, shame and dehumanization - will serve as the theoretical underpinning for our model of the disloyalty loop.

Using Gregoire et al.’s (2009) and Zarantonello et al.’s (2016) studies, the

authors propose a novel model to encompass the negative aspects of the consumer-brand relationships, outside the loyalty loop. This presupposes that the consumer has some interaction with the brand and has used its product or service at least once. The proposed model consists of four stages – disappointment, frustration, separation, and revenge.

Figure 1. The Loyalty Loop (Court et al., 2009) and the Disloyalty Loop

The authors of this study consider disappointment as a passing step between the loyalty and disloyalty loop, and therefore, the model assumes that one cannot be classified at that stage long-term. The other stages of the disloyalty loop are constructed to mirror the

individual stages of Court et al.’s (2009) loyalty loop (enjoy, advocate, bond). If the consumer’s negative experience is forgiven, they return to the loyalty loop, and if their disappointment continues, they devolve to frustration. The first two steps – disappointment and frustration – are cases of “passive brand hate”, while the latter two – separation and revenge – are representative of “active brand hate” as described by Zarantonello et al. (2016). These stages are considered to reflect the active and passive forms of brand loyalty (Court et al., 2009), adding further credence to the model. Each stage will be elaborated in the sections below.

The disloyalty loop framework does not limit consumers in a single unidirectional movement along the loop. The authors assume that consumers may move from one stage of the disloyalty to the next or previous one, leave the loop completely, or return to the loyalty loop. It is also possible that consumers skip a stage in their journey, for example, transitioning from frustration to revenge, and then back into the loyalty loop. The authors base this navigation pattern on the findings of Gregoire et al. (2009), which outline how consumers can go from loving to hating a brand. The authors will analyse the navigation of consumers between the loyalty and disloyalty loop and aim to provide further insight in the dynamics of consumer-brand relationships.

2.7

Stages of the Disloyalty Loop

2.7.1 Disappointment

The first stage of the disloyalty loop finds itself closest to the loyalty loop while

the consumer is still enjoying his interaction with the brand. A negative experience takes place, which forces the consumer out of the loyalty loop and into the disloyalty loop. Disappointment is comparable to the “enjoy” stage of the loyalty loop; it is seen as a prerequisite of being in the disloyalty loop. This experience could be a specific event - a service failure, disappointing experience after buying due to a faulty product or unsatisfactory service, an unpleasant interaction with a customer service representative, or even a news article or blog revealing something about the brand that makes the consumer wish to disassociate with it (Gregoire et al, 2009; Zarantonello et al, 2016).

Disappointment is the first stage in the disloyalty loop, and a critical one – most

commonly, the consumers will not voice their issue at this point. Once the consumer enters the disloyalty loop, they are embittered. Their trust in the brand has been betrayed, at the very least at that point in time. They likely still foster positive emotions towards the brand but are increasingly concerned regarding the health and longevity of the relationship. They may also reduce their patronage, but not cease it completely at this stage. It is critical to mention that disappointment is a passing stage in the consumer-brand relationship. Depending on the

source and severity of disappointment, it is possible that the consumer be brought back to the loyalty loop, given his pain is addressed, forgiving brand for its misdoing (Gregoire et al, 2009), or continuing to the next stage of the disloyalty loop.

2.7.2 Frustration

The second stage of the disloyalty loop is frustration - the consumer continues to

experience the same or new issues and is increasingly let down by the brand. The experience that caused them disappointment has not been resolved, either by them or the brand, and it continues to be a pain for them. It is at this stage that the consumer may choose to voice their dissatisfaction by sharing with their surrounding and even to a broader audience via social media. They could contact the brand’s customer service and leave a complaint or enquire about the issue in the case of damaging news to confirm whether it is true, such as could be the case with corporate wrongdoings (Zarantonello et al, 2016).

At this point of the disloyalty loop, the customer is still positive towards the

brand, though increasingly concerned. The relationship is progressively worsening the longer their pain persists. The consumer may still be a patron of the brand depending on the category, however unwillingly. This may be due to convenience or a lack of a suitable alternative. However, in many cases, as the consumer has already invested money and time in the relationship, they have built up a level of commitment to the brand. Thus, many consumers will continue their previous behavioural patterns, implying forgiveness, in hopes that brand will mend its ways and the service failure will simply fade from memory (Donovan et al., 2012).

2.7.3 Separation

Having voiced their frustration and received no adequate solution to their

problem, the consumer becomes increasingly disheartened. They are unable to resolve their issue, and the brand, which they believed to have a meaningful relationship with, not only failed to meet their expectations, but also failed to make up for it and address the consumer’s complaints adequately. At this stage, the consumer chooses to leave the brand (Hogg et al., 2009) and ends the relationship. They may abandon solely the brand or the entire category, should the brand be synonymous with the category.

Having abandoned the brand, the user may decide to take one of several paths.

They could simply avoid the brand by ceasing their patronage and staying away from the brand’s offerings and communication (Lee et al, 2009). Another option would be to attempt to hurt the brand, either to satisfy a personal desire for revenge as justice for the wrongdoing (Gregoire et al, 2009), or to protect fellow consumers, such as in the case of Andy Caroll and

United Airlines (Andres, 2019). A third option is to exit the loop completely over time, thus ending the customer decision journey. Subsequently, that consumer may avoid the brand due to an inability to see themselves using it again (Hogg et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009). The consumer may also choose to forgive the brand and even return to the loyalty (Donovan et al., 2012).

It is important to note that abandonment may occur at any point of the disloyalty loop. A seemingly minor disappointment may cause a user to take a reactive decision to stop buying the brand. This may particularly be the case when the consumer is in the early stages of the loyalty loop, i.e. when they have not been through the loop for a considerable number of cycles or given time period. Additionally, a revanchist aiming to make the brand pay for the damage they have been caused, may still be using the brand while badmouthing it.

2.7.4 Revenge

In line with Gregoire et al.’s (2009) findings, we named the final stage of the

Customer Disloyalty Loop, revenge. Given today’s digital connected reality, consumers may exact revenge on the brand and one or several of many ways – negative reviews on social media, forums, video-sharing platforms, traditional nWOM, or even taking more active approaches, such as producing original material (as in the case of United Airlines explained below). This broad range of possibilities empowers consumers to express their dissatisfaction and fulfil their desire to hurt the brand. On the other hand, it involves large risks for the corporate actor, threatening their business and public image.

A popular example of this is the case of Canadian singer-songwriter Dave Caroll. In 2008, he took a flight to Omaha, Nebraska via Chicago with United Airlines (O’Byrne, 2011). While waiting to leave the airplane at Chicago, the artist was informed by one of the passengers behind him that the ground crew were “throwing guitars out” of the plane. When he arrived at his destination, Caroll discovered his Taylor guitar had been broken in transit (O’Byrne, 2011). He contacted the airline and attempted to receive a compensation for his instrument, but was repeatedly rejected, and he did not even receive an apology.

His frustration led to a creative outburst and a commitment to write and release three songs about the situation on YouTube (O’Byrne, 2011). In 2008, “United Breaks Guitars” debuted on the video-sharing platform, telling the story of his mishap. The video became viral, reaching millions of users all over the world and causing the company significant losses in business and falling stock prices (Andres, 2019). Following the release of the video, United contacted Caroll to reach an agreement, failing to apologize and address his consumer demands. The artist released the remaining two songs about his struggles with the customer

service of the brand, and one demanding it be improved not just for his sake, but for that of all United passengers (Andres, 2019).

This case is unique in terms of being one of the most well-known customer complaints and demonstrates how empowered modern consumers are in making their voice heard, much in line with Court et al. (2009). It outlines a destroyed consumer-brand relationship and the impact it can have on the brand and other users. In this case, the Canadian artist acted in a way to protect other United consumers from having a similar negative experience to his, and put public press on the company to influence into changing its customer service policy (Andres, 2019). Given our connected way of life and the contemporary empowered consumer, brands have much to lose in the dissolution of the relationship with their consumers.

3. Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter describes the research approach, formulation, interview design, sampling, and ethical considerations in this study.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1

Area of Study & Data Collection

As previously stated, negative consumer-brand relationships have not been extensively addressed in marketing literature, and thus, much is still left to be discovered. In addition, social media as a context of study has not been sufficiently explored in terms of the interactions of consumers with the platforms’ brands; instead, the focus has been on these networks as a marketing channel. Further insights are necessary in order to form definitive theories and identify clear cause-effect relationships.

To outline the methods used in this study, the authors follow Saunders et al.’s (2012) model of the “research onion”, comprising of research philosophy, approach, strategy, method choices, time horizons, techniques and procedures. A description of each component, including the author’s choice and justification in relation to the purposes of this study, is outlined in the following sub-chapters.

In order to generate insights into consumer-brand relationships, the authors will need to collect primary data. To understand the intricacies of these interactions, including the emotional experiences and reactions of the respondents, the study will gather qualitative data, i.e. non-numerical verbal information (Saunders et al., 2012). Qualitative studies analyse respondents’ meanings and the connections among them. This type of information captures

the expression of feelings and attitudes, and has the capacity of being highly detailed, identifying previously unconsidered possibilities within the topic.

3.2

Research Philosophy

Research philosophy refers to the description of guiding principles, which will lead the authors through the process of studying a phenomenon (Bajpai, 2011). Qualitative data is typically related to an interpretivist philosophical stance (Dinzin & Lincoln, 2005). Interpretivism assumes that the nature of reality is socially constructed, and the researchers must make sense of the language and meanings that participants attach to their responses (Saunders et al., 2012).

This research philosophy offers access to in-depth information and a high level of validity as participants offer their honest attitudes. However, there is an inherent drawback of this approach due to its subjective nature, which leaves room for researcher bias (Saunders et al., 2012). The authors consider an interpretivist philosophy appropriate for the purpose of this study as it allows for generating in-depth insights in an underexplored field of research. The ability to scrutinize consumers’ narratives of their relationships with brands will provide a greater deal of understanding to their navigation of the loyalty loop and offer evidence in favour or against the disloyalty loop.

3.3

Type of Study

Given the purposes outlined, the decision was made to conduct this study in an exploratory manner. The main reason is that exploratory research aims to provide a better understanding of a problem and bring to light new insights that can contribute to the development of the body of knowledge (Brown, 2006). Exploratory studies seek to deepen the understanding of the nature of the problem in order to reveal whether further investigation is justified (Saunders et al., 2012). The findings are commonly utilized to formulate new theories, rather than providing irrefutable answers to research questions (Brown, 2006).

Exploratory studies have the benefit of being flexible and subject to change throughout the research process (Saunders et al., 2012). Researchers often adjust their focus in line with the findings during the course of the study; they must be prepared to adapt the direction as novel findings are revealed. Furthermore, they are particularly useful for establishing the base for future studies (Saunders et al., 2012). A drawback worth mentioning is that due to the smaller sample sizes often associated with this type of research, the findings are less generalizable to the broader public.

3.4

Reasoning

Reasoning in research studies can be divided among inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning (Johnson-Laird, 1999). Hayes, Heit & Swendsen (2010) refer to inductive reasoning as a process that involves predictions about unexplored or new situations that can

be related to prior knowledge. In plain English, using known information to reach unexplored conclusions. It assumes a “bottom-up” approach, from the specific knowledge of the individual to broader general implication (Saunders et al., 2012). The majority of the predictions are heavily based on, or adapted to probabilistic theories (Hayes et al., 2010). Inductive studies use data collection to gain insights on a specific topic in its context and attempt to extract patterns from the observations (Saunders et al., 2012). This aspect makes them highly appropriate for theory building and expansion of current academic literature.

Deduction, on the other hand, is defined as the one yielding valid conclusion while needing to be true given their premises (Johnson-Laird, 1999). In other words, logical conclusions can solely be reached through deductive reasoning if the premises upon which knowledge is based are true. This means mainly that, deductive reasoning links premises and conclusions together so as to test for validity (Johnson-Laird, 1999). In opposition to the inductive “bottom-up” approach, deductive reasoning starts on an abstract level of theory and follows a way down in the attempt to come to a more specific and concrete level, being called for this reason as “top-down” approach (Johnson-Laird, 1999).

A third existing alternative, known as abductive reasoning, aims to address the weakness of the inductive and deductive approach. Abduction uses what is known to create testable hypotheses, moving between data and theory to effectively combine the other two approaches (Suddaby, 2006). Going beyond data collection for identification of tendencies, this approach may also test the hypotheses proposed.

Due to the abstract and largely unexplored nature of the phenomenon, brand disloyalty in the context of social media, and the limited amount of existing research, this study adopts an inductive approach as most suitable for the research subject. According to Hayes et al. (2010), the study of decision-making processes is best addressed with this method. Due to the abstract and largely unexplored nature of the phenomenon, the limited amount of existing theory and finally the need of determination of existence of a potential alternative consumer journey to the loyalty loop, the authors adopt an inductive reasoning. Finally, an alternative reasoning approach is presumed to limit the perceived flexibility of the research, and thus, the breadth of valid contributions to the study of consumer-brand relationships.

3.5

Research Strategy

A research strategy is defined by the manner, in which the authors aim to answer the research questions (Saunders et al., 2012). In other words, it is the applied methods to generate results. One of the most frequently used strategies in exploratory research is the case study. Case studies are defined as exploring “a research topic or phenomenon within its

content, or within a number of real-life contexts” (Saunders et al., 2012, p.179). They offer

example, the survey strategy where respondents have a pre-defined set of options they can choose from. Case studies may focus on a single case, or on multiple cases (Yin, 2009). The benefit of conducting this type of research with a single respondent is delve into a particularly fascinating example, which may be crucial in understanding the general phenomenon. On the other hand, studying multiple respondents produces a more significant volume of primary data, which aids the reliability of the study (Saunders et al., 2012).

Considering the interpretivist philosophy, the exploratory nature of this paper and its inductive reasoning, a case study strategy would be best suited to answer the research questions. In this manner, the authors can focus on extracting detailed information describing the consumer-brand interactions. By studying multiple cases, different journeys will be discovered, contributing to the conceptualization of disloyalty, and offering new explanations as to why and how consumers become disloyal.

By conducting semi-structured interviews with consumers and understanding their relationships with social media brands, the authors will explore whether a disloyalty loop exists. The insights generated by the conversations with consumers will shed further light on consumer-brand relationships, how they devolve, how they are restored, and what consumers see as valuable determinants in the development of the interaction. Subsequently, the findings of this paper aim to contribute to the existing body of research and lead to a better understanding of the subject matter.

3.6

Method of Data Collection

A research interview is defined as “purposeful conversation between two or

more people, requiring the interviewer to establish rapport, to ask concise and unambiguous questions, to which the interviewee is willing to respond, and to listen attentively” (Saunders

et al., 2012, p.372). Its purpose is to provide the researchers with detailed valid information while enabling interaction with the respondents for further clarification.

For the goals of this study, respondent interviews were conducted. In this type of study, the interviewer has the opportunity to converse solely with one respondent and capture only their perspective on the matter (Jensen, 2012). This method was selected due to the aim of understanding the individual’s relationship with the brand, which necessitates an ability to focus on the interviewee and follow their responses with questions that can lead to further insights. In other interview methods, such as naturalistic or constituted group interviews, the interactions between the actors in the group would be more representative of a general social relationship with the brand, instead of the personal relationship (Jensen, 2012). Therefore, they did not fit the goals of this study.

In order to explore the topic of study in detail, we chose to conduct semi-structured interviews. This method of inquiry allows the exploration of all the aspects of the discussed topic (Schensul & LeCompte, 2013). The interview was designed in an open-ended fashion, where interviewees could answer freely, and not choose their response from a list of options. The authors applied these methods to explore the unclear areas of the novel relationship between consumers and social media brands in hopes to discover a relationship between brand loyalty and brand hate. The free-form information was also used to guide the researchers to the context and history of the concept, particularly what prompted the interviewee to develop a certain relationship (Schensul & LeCompte, 2013).

The interview design was largely determined by the authors’ understanding of the subject of consumer-brand relationships and presuming that a relationship between brand loyalty and brand hate exists. Thus, an unstructured interview would not have fit the purpose of the study, as it is mainly intended to discover novel domains (Schensul & LeCompte, 2013). On the other hand, the exact relationship among the domains was not clear, and therefore, a strictly structured method, such as a survey, would not have sufficed either. Therefore, the semi-structured interview format was selected.

As Schensul & LeCompte state, “semi-structured interviews are best-suited for exploring and delineating factors and subfactors and their association” (2013, p.175). By setting a list of questions grouped at a factor level, the researchers could stay focused on the topic, while having the flexibility of an unstructured interview to further inquire the respondent, where clarification was needed (Cassell, 2015). Open-ended questions were asked. The results from the semi-structured interviews provided a firm base of knowledge to be interpreted, analysed, and concluded.

Due to the aim of the study, and the inherent time and resource constraints of a master dissertation, it adopted a cross-sectional approach. The authors explored consumer-brand relationship at the time of conducting the interviews. The purpose of the study also favoured an inquiry to discover whether brand disloyalty loop exists, instead of studying the development of a specific phenomenon over time as with a longitudinal study.

3.7

Interview Design

Jensen (2012) defines three key factors in interview design – duration, structure, and depth. The duration was not specifically pre-defined by the authors; instead the purpose was to explore the relationships at hand and allow for further questioning in the cases where further insight could be gained. The informal aim was to limit the interviews to thirty minutes

as to encourage respondents to conduct the interview. The authors considered it vital to respect the duration communicated to the participants, as theory suggests (Cassell, 2015).

Firstly, respondents were asked to provide information about the demographic categories. This was considered necessary in order to ensure the international profile of the study. While there is debate in terms of whether these questions should be asked before or after the main theme, the authors opted to receive this data up-front, and allow the participants to focus on their responses in the context of consumer-brand relationship (Schensul & LeCompte, 2013). Only relevant demographic data has been collected for this study, namely age, gender, nationality, and location of residence and occupation status (Cassell, 2015). Subsequently, the questions relating to social media, and the consumer-brand relationship were asked.

The first group of questions looked into the individuals’ general use of social media, including which platforms they used, how many days per week they used them, and their preferences for networks. These were followed by the groups of questions structured in accordance with our model of the disloyalty loop. The main body of the interview mirrored the stages of the model (disappointment, frustration, separation and revenge) and examined whether the respondent was exhibiting behaviours that would classify them in that stage. This was based on the description of each stage in the literature review. The described structure allowed for a logical flow in the interview process. The authors took care to record answers to questions that had not yet been asked, avoiding repetition, and drifting away from the scope of the study (Schensul & LeCompte, 2013).

According to Babin & Zikmund (2016), a pretesting of the questionnaire may assist in addressing incomprehensibility and errors in the questions. Therefore, prior to data collection, a pre-test with was conducted a small group of two people. Moreover, the pre-trial supported the research in terms of ensuring that the questions were clearly formulated (Babin & Zikmund, 2016). The complete set of questions used is available in Appendix 1.

3.8

Interview Process & Analysis

The authors conducted a total of twelve semi-structured interviews through various means of communication, namely phone, and internet voice call services (Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp). The majority of interviews were conducted in English, with the exception of one that was conducted in Spanish, and one in Bulgarian. All interviews were audio recorded with the explicit permission of the participant and subsequently transcribed. In the case of the interviews in foreign languages, the authors translated the interviews with the highest regard to integrity and adherence to the participants’ statements (Cassell, 2015).

Face-to-face interviews could have contributed to a larger extent to this study, with the possibility of the interviewers detecting the emotional reactions of the responses and being more aware of the possibilities to develop the conversation (Stephens, 2007). However, given current global conditions in the face of the Corona virus (COVID-19) pandemic (Nicola et al., 2020), the prospect of meeting in person with the participants presented a risk for both parties. While face-to-face communication offers valuable insight into the respondents’ attitudes through visual cues, some research suggests that phone interviews (which we equate to our online audio calls in this case) may be just as relevant. In fact, studies claim that there are advantages from conducting non-face-to-face interviews, such as a more comfortable setting for the participants and a lower likelihood of the researching taking analytic leaps (Holt, 2010). Therefore, due to the viability of audio interviews, and in the interest of the health and wellbeing of all parties involved, a decision was made to conduct all interviews through voice calls.

3.9

Sampling

As mentioned, global conditions made it virtually impossible to conduct face-to-face interviews, where the interviewers could familiarize themselves with the respondent, build rapport, and attempt to create a safe and inviting environment. This also meant that the potential of reaching out to likely respondents was hampered due to the cancellation of classes at Jönköping University (Nicola et al., 2020), and the government discouragement of public gatherings in Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020). As a result of all these coinciding conditions, there was a limit to the type of sampling the authors could utilize. In terms of probability, non-probability sampling was selected, as it is better suited for qualitative studies (Cassell, 2015). In order to capture the “whole set of entities that decision relate to” (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008, p. 212), i.e. consumers who use social media, the authors ensured that all respondents currently use or have used social media.

Participants were selected by convenience sampling, choosing the most relevant contacts of the two authors of this research and as well as the ones who were available for the interview (Etikan, Musa & Alkassim, 2016). This method was preferred due to its high informative value and its uncomplicated feasibility. A filter was applied during our recruitment process, by determining that only those consumers who at the interview were active users of social media platforms or had been in the past. Although the implemented sampling method has its limitations, it was still beneficial and appropriate to the case of the study.

Regarding sample size, qualitative inductive studies can make great use of smaller groups of respondents, instead yielding a variety of perspectives on the phenomenon (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). Considering the format of semi-structured interviews, a wealth of information and further insight could be provided on the topic of consumer-brand relationships with a similar number of participants. The authors set a minimum of ten interviews as the lowest number of responses, which would add credibility to the study and a variety of consumer-brand relationships.

The exploratory character of the study required access to respondents who would be willing to speak openly about their personal experience with social media. As this topic is close to the heart of many users, it was essential that the respondent feel comfortable in the interview situation (Cassell, 2015). Convenience sampling was selected as the most appropriate option. The authors reached out to their personal networks of friends and acquaintances and found twelve respondents who would be willing to describe their experiences for the purposes of the study.

A critical aspect of gathering high-quality primary data through interviews is that the interviewer establish rapport with the respondent (Cassell, 2015). This can also be described as a process of establishing trust between the two parties (King & Horrocks, 2010). In this regard, the authors were assisted by the use of convenience sampling. The familiarity between the interviewers and the respondents facilitated a comfortable environment, where the respondents felt they could trust their counterparts and freely express their attitudes. This may be seen as a benefit to the study as the respondents shared personal experiences that they may not feel at ease divulging to strangers, despite the perceived value of the academic work they would be contributing to. However, the pre-existing relationship may be viewed as a drawback in terms of replicability of the study, as the respondents may not second their statements to another team of researchers.

3.10

Data Quality

There are three measurements of data quality in qualitative studies – reliability, validity, and generalizability. Reliability addresses the ability of future research to retrieve similar data with similar methods implemented (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). However, what is important to consider is that qualitative research, particularly case studies, offer a high level of flexibility to explore unknown areas (Saunders et al., 2012). Its strength lies in the ability to bring to light new insights and suggest new theories. In addition, the findings reflect the specific circumstances, in which the data was gathered. The authors have ensured to outline their chosen methods, allowing future research to implement the same techniques, and have