Let’s Make Better

Mistakes Tomorrow

BACHELOR’S DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Marketing Management AUTHORS: Ramona Nazem Ghanai, Malin Forss, and

Gabriella Sundkvist

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Brand Management and Crisis Communication

for Social Media Influencers

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratefulness to everyone who have contributed to the finalization of our study.

Firstly, we would like to thank our tutor, Lucia Pizzichini, who has given us valuable feedback and guidance throughout the course of this thesis project.

Secondly, a special thanks to all of the fellow individuals who have participated in our study, spending their valuable time to help us realize our project.

Thirdly, we want to communicate our gratitude for the guidance and information provided by Anders Melander throughout the process.

Fourthly, we want to express our appreciation towards Naveed Akther, who has given us valuable tools for comprehending the principles of research methods.

Lastly, we would like to acknowledge Augustine Pang at Singapore Management University, for bringing the topic of crisis communication to our knowledge during our exchange semester.

___________________ ___________________ ___________________ Ramona Nazem Ghanai Malin Forss Gabriella Sundkvist

Bachelor Thesis Project in Business Administration

Title: Let’s Make Better Mistakes Tomorrow

Authors: Nazem G., R., Forss, M., & Sundkvist, G.

Tutor: Lucia Pizzichini

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Social Media Influencer, Self-Branding, Brand Management, Crisis

Communication, Image Repair Theory

Abstract

Background: The social media user boom has given rise to a new type of profession, namely,

Social Media Influencers (SMIs). The unique selling point of SMIs refers to the relationship they establish with their followers. However, the downside of being a SMI concerns the high media scrutiny received during the event of a crisis. The literature suggests practical implications for organizations and public figures on how to combat a media crisis while lessening the damaging effect on the reputation.

Problem: Current literature is focused on the positive aspects of SMI marketing as well as the

importance of managing the damaging effects towards brands. However, the literature has not yet explored the application of brand management and crisis communication to the SMI profession.

Purpose: This study aims to provide a deeper understanding of SMIs’ brands from a consumer

stakeholder perspective. Additionally, by adopting Image Repair Theory (IRT), meaningful connections from primary data were drawn based on the assumption that reputation is valuable to organizations and individuals.

Method: A qualitative approach was implemented by conducting four focus groups, consisting

of 20 young Swedish females in total, who are followers of four selected Swedish SMIs.

Results: The findings suggest that SMIs are human brands in need of care and management,

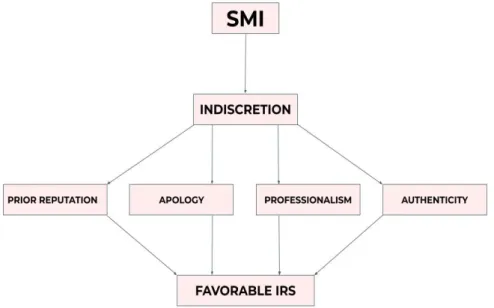

alike those brands of organizations. Furthermore, existing themes along with two newly discovered elements of IRT was implemented, which laid grounds for ways in which SMIs may execute favorable Image Repair Strategies (IRS) when conjunct with allegations of indiscretions.

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2 1.3 Research Purpose ... 3 1.4 Research Questions ... 4 1.5 Delimitations ... 4 1.6 Definitions ... 52.

Frame of Reference ... 6

2.1 Systematic Collection of the Literature ... 6

2.2 Self-Branding ... 7

2.3 Social Media Influencer ... 8

2.4 Social Media Influencer Authenticity ... 9

2.5 The Reputational Asset and Image Repair Theory ... 11

2.5.1 Image Repair Theory ... 12

2.5.1.1 Apologies ... 13

2.5.1.2 Prior Reputation ... 14

3.

Methodology and Method ... 16

3.1 Methodology ... 16 3.1.1 Research Paradigm ... 16 3.1.2 Research Approach ... 17 3.1.3 Research Design ... 17 3.2 Method ... 18 3.2.1 Primary Data ... 18 3.2.2 Sampling Approach ... 19 3.2.2.1 Sampling of Cases ... 20 3.2.2.2 Sampling of Participants ... 21 3.2.3 Focus Groups ... 22 3.2.4 Interview Questions ... 23 3.2.5 Data Analysis ... 24

4.

Ethics ... 25

4.1.1 Confidentiality and Anonymity ... 26

4.1.2 Credibility ... 26 4.1.3 Transferability ... 27 4.1.4 Dependability ... 27 4.1.5 Confirmability ... 28

5.

Empirical Findings ... 29

5.1 Background ... 295.2 Social Media Influencer ... 31

5.2.1 Satisfactory ... 33

5.2.2 Dissatisfactory ... 34

5.2.3 Relatable ... 35

5.2.4 Responsible ... 35

5.3 Social Media Influencers: Image, Indiscretion, and Response ... 36

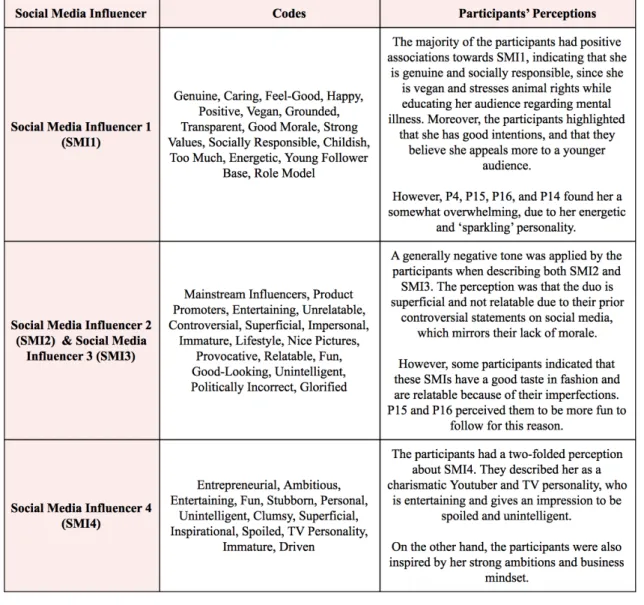

5.3.1 Participants’ Perceptions of the Social Media Influencers’ Images ... 36

5.3.1.1 Image: Social Media Influencer 1 ... 37

5.3.1.2 Images: Social Media Influencer 2 and Social Media Influencer 3 ... 38

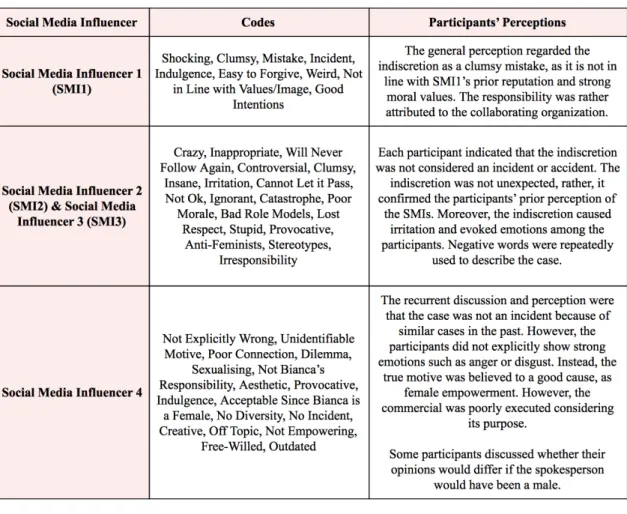

5.3.2 Participants’ Perceptions of the Social Media Influencers’ Indiscretions ... 40

5.3.2.1 Indiscretion: Social Media Influencer 1 ... 40

5.3.2.2 Indiscretion: Social Media Influencer 2 and Social Media Influencer 3 ... 41

5.3.2.3 Indiscretion: Social Media Influencer 4 ... 42

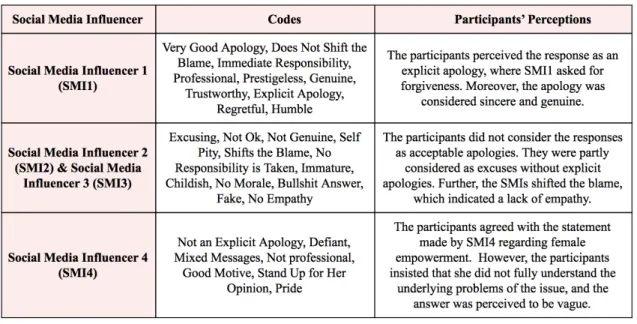

5.3.3 Participants’ Perceptions of the Social Media Influencers’ Responses ... 43

5.3.3.1 Response: Social Media Influencer 1 ... 44

5.3.3.2 Responses: Social Media Influencer 2 and Social Media Influencer 3 ... 45

5.3.3.3 Response: Social Media Influencer 4 ... 45

5.4 Social Media Influencer Self-Branding ... 46

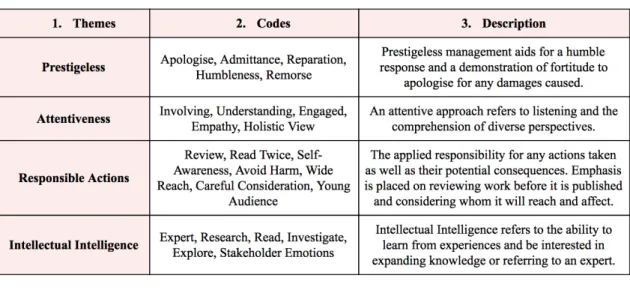

5.5 Favorable Image Repair Strategies ... 47

5.5.1 Prestigeless ... 48 5.5.2 Attentiveness ... 48 5.5.3 Responsible Actions ... 49 5.5.4 Intellectual Intelligence ... 49

6.

Analysis ... 50

6.1 Self-Branding ... 506.2 Social Media Influencer ... 51

6.3 Social Media Influencer Authenticity ... 52

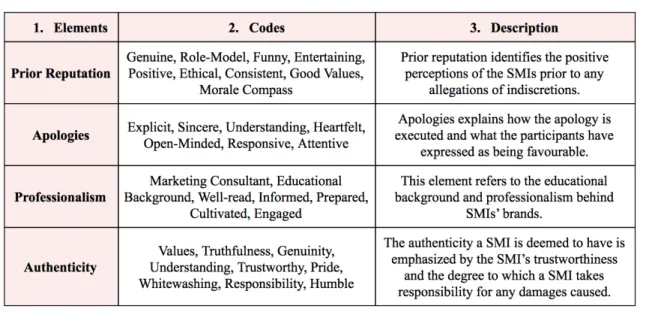

6.4 The Reputational Asset and Image Repair Theory ... 54

6.4.1 Image Repair Theory ... 54

6.4.1.1 Prior Reputation ... 56 6.4.1.2 Apology ... 58 6.4.1.3 Professionalism ... 58 6.4.1.4 Authenticity ... 59

7.

Conclusion ... 61

8.

Discussion ... 62

8.1 Contributions ... 62 8.2 Practical Implications ... 63 8.3 Limitations ... 63 8.4 Future Research ... 649.

References ... 66

10.

Appendixes ... 74

10.1 Appendix 1: Framework of Articles ... 74

10.2 Appendix 2: Themes of Articles ... 77

10.3 Appendix 3: Interview Questions ... 79

10.4 Appendix 4: Consent Agreement ... 81

1

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________

This chapter outlines the background of the phenomenon of Social Media Influencers, highlighting its growing trend in society as well as its potential issues. Thereafter, a problem statement is provided, establishing the purpose of the study and crafting the research questions. Lastly, a list of definitions that ease the comprehension of the research is provided.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The increasing worldwide internet accessibility is a gamechanger for the popularity of social media and various social networks. Accordingly, the average social media user spends approximately 135 minutes on social media each day, representing a trend that is expected to increase over time (Statista, 2019). This ever-changing interactive landscape creates new opportunities for marketers and brands, enabling them to move from traditional marketing strategies to social media marketing strategies (Statista, 2019). Interestingly, Edelman’s global trust barometer shows that there is a decrease in trust towards general information and news that spread on social media (Edelman, 2018). However, Edelman (2018) also claims that 59 percent of the consumers are more persuaded by direct communication of brands through social media, than what is communicated in traditional advertising content. Additionally, it appears that the more critical users are young adults, aged 18-34, of which 54 percent indicate that it is a brand’s fault if its advertising appears next to inappropriate content on social media, and that the brand’s values are implicitly indicated in marketing messages (Edelman, 2018).

Furthermore, the social media user boom has given rise to a new type of profession, namely, Social Media Influencer (SMI) (Suciu, 2020). A SMI may be defined as a person who can influence the behaviors of other people, and from a marketing perspective, a person who is paid by companies to endorse products and services on social media (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d). Undoubtedly, SMI is a new form of a marketing-related profession (Thurfjell, 2018). In fact, as of 2018, certain Swedish high schools provide the possibility for students to educate themselves to become professional ‘Influencers’ or

2

‘YouTubers’. For instance, Thoren Innovation School offers “The Influencer Education”, which aims at preparing young adults to promote themselves as brands in various social media channels (Thurfjell, 2018). In the same course, Suciu (2018) claims that the unique selling point of an influencer is ‘the self’, exposed by the ability to establish trust and relationships with their followers. This bond, built with a sense of trustworthiness, influences consumers to prefer SMI advertising content over traditional advertising (Suciu, 2020). Furthermore, an example of a SMI who has built her brand around her luxurious everyday life, combined with her transparency regarding anxiety and mental illness, is Swedish Michaela Forni (Shayn, 2018). According to Forni (2018), what she is selling is a private ticket to her highly personal and oftentimes sad thoughts regarding relationship problems that her followers can relate to; thus, jeopardizing her private life and blurring the lines between work-life balance.

However, this openness and transparency may now and then create issues for SMIs (Shayn, 2018). Specifically, a downside of being a SMI concerns the negative sentiments and high media scrutiny received on both social- and traditional media concerning a dispute, crisis, or scandal (Sng, Au, & Pang, 2019). In some cases, the negative sentiments and critique are too overwhelming for SMIs, causing them to withdraw from their platforms simply to avoid the negative comments (Palm, 2018). However, brand management and crisis communication literature suggest practical implications for organizations and public figures on how to combat a media crisis and restore trust, while lessening the damaging effect on the reputational asset (Coombs, 2019; Benoit, 1997).

1.2 Problem Discussion

Revisiting the literature, it becomes evident that the phenomenon of SMIs is gaining momentum in the marketing literature. The existing body of knowledge mainly revolves around the positive aspects of SMI marketing, such as the ability of SMIs to establish strong relationships with consumer stakeholders due to SMIs perceived authenticity (Enke & Borchers, 2019); and the positive relation between SMI endorsed products and consumers’ purchasing behavior (Nurhandayani, Syarief, & Najib, 2019; Zak & Hasprova, 2020). In contrast, recent research in crisis communication highlights the importance of being aware of the damaging effects on the endorsed brand when conjunct with allegations of indiscretions (Sng, Au, & Pang, 2019). However, due to the novelty

3

of the SMI phenomenon, the literature leaves room for further exploration in two major areas in particular:

Firstly, it is not yet explored whether SMIs’ brand images are damaged when being portrayed negatively in media due to accusations of irresponsible or offensive behavior. Therefore, the literature leaves a gap to understand if, how, and to what extent, change in consumer stakeholders’ perception occurs when SMIs are conjunct with allegations of indiscretions. As far as image is concerned, it is suggested that the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an indicator of ‘good values’ and serves as an amplifier of trust towards brands (Coombs & Holladay, 2015; Lee, 2016; Janssen, Sanker & Bhattacharya, 2015). However, the available research on the true need for a good reputation for the SMI profession is restrained (Ismail, Pagulayan, Francia, & Pang, 2019).

Secondly, the literature leaves a gap in exploring if and how the Image Repair Theory (IRT) is applicable for SMIs when managing their brands (Coombs, 2015; Benoit, 1997). Specifically, during the event of allegations of indiscretions, favorable elements in Image Repair Strategies (IRS) for SMI brands are yet to be uncovered. Furthermore, the literature claims that companies and political leaders are attributed a higher degree of responsibility than the average person (Ismail et al., 2019). Additionally, it is suggested that SMI marketing is effective partly due to the elevated trust from their relationship with their followers (Djafarova & Trofimenko, 2017). Hence, the idea that SMIs may carry the same type of responsibility as that of organizations and political leaders during the event of a crisis is to be investigated. Conclusively, to fill these gaps, there is a need to extend the knowledge on the perception of SMIs’ brand images when conjunct with allegations of indiscretion and favorable elements in an IRS.

1.3 Research Purpose

Currently, the literature on crisis communication is mainly conducted by the use of case studies and textual analysis in order to establish public perceptions surrounding certain events (Ismail et al, 2019). Therefore, this study aims to provide a deeper understanding of SMIs’ brands from consumer stakeholders’ perspectives. The purpose is to investigate the phenomenon from a new angle deemed at exploring new insights that fill the aforementioned gaps.

4

Moreover, the research is conducted with the ambition to provide useful implications for the SMI profession regarding brand management when conjunct with allegations of indiscretions. The findings may also be useful for understanding SMIs’ target audiences’ perceptions surrounding media scrutiny while providing practical implications for SMIs to manage their brands accordingly.

However, the focal is on understanding consumers' perceptions and thereby contribute to the literature and theory. Therefore, the research may be seen as exploratory by connecting the empirical data with the guiding theory (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2016). More specifically, by adopting Benoit’s IRT as a guiding theory, meaningful connections from the data may be drawn based on the assumption that reputation is valuable to organizations and individuals.

1.4 Research Questions

RQ1: How are Social Media Influencers’ brand images perceived when conjunct with allegations of indiscretions in media?

RQ2: What are considered favorable elements of an Image Repair Strategy for Social Media Influencers?

1.5 Delimitations

To clarify the intended scope and context of the research, certain delimitations need to be outlined. Firstly, the research is delimited to specific cases of allegations of indiscretions against four Swedish SMIs. Accordingly, the research is based on the perceptions of young females (aged 18-30) who are of Swedish nationality and active social media users, due to the relevance of the study and the accessibility of the researchers. Secondly, the research is focused on brand management and crisis communication on behalf of SMIs and does not concern the strategies in using their platforms as marketing tools. This was decided since the novelty of the phenomenon has led to a lack of literature aimed at interpreting the idea of SMIs as brands. Thirdly, the research is delimited to investigate the applicability of the IRT to the SMI phenomenon, as this perspective is yet unexplored in the existing literature. Furthermore, reputation is considered a valuable asset in the brand management and crisis communication literature, and thus, needs to be managed during the event of an indiscretion.

5

1.6 Definitions

Allegation: A statement or claim that someone has done something wrong or illegal,

normally one made without any given proof (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.).

Brand Image: “...perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in

consumer memory” (Keller, Aperia, & Georgeson, 2012, p. 62).

Consumer Stakeholder: A consumer that has an interest in, or is involved in something

(Cambridge, n.d.).

Follower: Someone who chooses to see someone else’s messages and information on

social media (Cambridge, n.d.).

Indiscretion: An act or a statement marked by lack of discretion or wrongful moral nature

(Webster, 2020).

Influencer Marketing: The practice of SMIs promoting commercial brands’ products on

their social channels in return for cash payments or free products or services (Kádeková & Holienčinová, 2018).

Instagram Feed: A place where people can share things of interest and connect with

others. Additionally, all posts and accounts one follows on Instagram appear in the ‘feed’ (Instagram, 2020).

Profession: A paid occupation, in particular one that requires advanced education or

training (Business Dictionary, n.d.).

Social Media Influencer (SMI): A self-branded content generator who has cultivated a

sizable number of followers and who is of marketing value to brands by regularly producing valuable content via social media (Chen & Shupei, 2018).

Social Media: Media forms using the internet, enabling individuals to share information

6

2. Frame of Reference

_____________________________________________________________________

This section presents an overview of the existing body of knowledge on the research topic. Firstly, the systematic procedure of literature collection is outlined. Further, a literature review of the prominent themes within the research on SMIs is performed. Lastly, a theoretical framework based on the reputational asset and the IRT is presented.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Systematic Collection of the Literature

In order to generate a deep and contemporary understanding of the existing scope of literature on the research topic, the literature review mainly draws on previous research from 2015 onwards. Exceptions were made to an article from 1997 by Tom Peters, from which many scholars draw their definitions of the concept of self-branding. Additional exceptions were made with regards to the comprehension of the reputational asset as well as the IRT (see Appendix 1 and 2).

The researchers collected literature using online databases of Google Scholar, Primo, and the Jönköping University Library. The keyword search was based on the three primary fields of this study: brand management, crisis communication, and social media influencer. More specifically, the terminologies included in the keyword search were

self-branding, social media influencer, micro-celebrity, influencer marketing, brand management, and Image Repair Theory, all of which combined differently to discover

suitable literature. To add to the quality and credibility of the frame of reference, the researchers included journals from 2018’s ABS list, as well as assured that each article analyzed is peer-reviewed and written in English. Furthermore, a systematic screening of abstracts and summaries was made, enabling the researchers to efficiently identify the most relevant articles. During this process, the novelty of the research topic became evident, as the width and depth of its existing literature are rather limited. However, particular subjects within the research area proved to be predominant and more frequently appearing than others. The researchers categorized these subjects into different themes, which provided a structured overview of the existing knowledge on the research topic and helped identify the areas within the research field that are currently unexplored.

7

Conclusively, the themes presented in this review serve as a foundation for the identified gap and craft the research question of this study.

2.2 Self-Branding

Since the late 90’s, the idea of thinking of oneself as a brand to be marketed and sold has become a nearly compulsory action for aspiring professional and creative workers (Whitmer, 2019). This action may be interpreted in the notion of self-branding, also known as personal branding. When outlining the concept of self-branding, several authors build on Tom Peter’s definition. Peters (1997) provides a straightforward and practical explanation of the key principles of self-branding, where he states that everyone has the power to be their own brand and that a person’s main task is to be his or her own marketer. Additionally, Peters (1997) stresses that alike commercially branded products, individuals need to assure control of their brand in order to stand out in the marketplace and simultaneously, deliver value to consumers, employers, and markets. Furthermore, another angle is provided by Khamis, Ang, and Welling (2016), who describe that the concept of self-branding refers to the practice of individuals developing distinctive public images for commercial and cultural gain. The main idea is that individuals benefit from having a unique selling point, as well as a singular public identity, that is responsive to the needs and interests of target audiences (Khamis et al., 2016). Accordingly, Whitmer (2019) argues that self-branding involves individuals thinking of themselves as products to be marketed to mainstream audiences, with the purpose of becoming economically competitive. In addition, the recipe for successful self-branding includes careful audience management, selective exposure of personal information in order to reveal a sense of the self-brander’s personality, and capability of carrying a promotional message. It is about constructing and promoting a consistent, authentic self-image, in order to develop relationships that may lead to economic opportunities (Whitmer, 2019).

Along with the current digital era, the concept of self-branding continues to grow both in terms of popularity and influence (Khamis et al., 2016). Additionally, several scholars emphasize the connection between self-branding and social media, particularly in the context of a ‘common’ fame-seeking individual who lacks a strong public identity alike the ones of celebrities (Khamis et al., 2016; Duffy & Hund, 2015; Liu & Suh, 2017). In essence, social media enables ordinary users to practice self-branding and create high

8

public profiles, making fame more attainable. Conclusively, the ease of promoting one’s image through social media, along with the growth of digitalism and individualism, serve as a foundation of the popularity of self-branding and the rise of social media influencers (SMIs; to be discussed below) (Khamis et al., 2016).

2.3 Social Media Influencer

Over the last decade, social media has altered the relationship between celebrities and their fans, moving from an interpersonal experience to a more direct such through intimate interaction on social networks (Vangelov, 2019). This has given rise to the modern phenomenon of social media influencers (SMIs), which Abidin (2015) defines as ordinary internet users who acquire a relatively large following on social media due to textual and visual sharing of their personal lives and lifestyles. As opposed to traditional celebrities who are usually famous from either film, music, or sports, SMIs achieve fan bases via their social media presence (Jin, Muqaddam, & Ryu, 2019). Thus, SMIs strive to gain some sort of ‘celebrity capital’ by obtaining as much attention as possible while crafting an authentic self-brand through the use of social networks (Khamis et al. 2016). Furthermore, other scholars refer to SMIs as third-party intermediaries who have established valuable relationships with hard-to-reach stakeholders, such as young adult consumers or other niche groups. SMIs provide access to, and may potentially influence, these stakeholders through content production, content distribution, interaction, and social appearance on the social web (Enke & Borchers, 2019). To accurately summarize the phenomenon of SMIs, Chen and Shupei’s (2018, p. 59) definition is implemented as follows:

“A social media influencer is first and foremost a content generator: one who has a status of expertise in a specific area, who has cultivated a sizable number of captive followers - who are of marketing value to brands - by regularly producing valuable content via social media.”

According to Enke and Borchers (2019), the term ‘influencer’ itself reflects its function as well as its relevance, in the sense that, due to their influential ability, SMIs can alter the attitudes and opinions of their so-called ‘followers’, and thus, positively affect organizational objectives. This links to the fact that brands have recognized that SMIs are

9

effective in rapidly spreading messages about new products and services, setting new trends, and ultimately, increasing sales (Jin et al., 2019). Moreover, scholars have found positive correlations between products promoted by SMIs and consumers’ purchase behavior, confirming that SMIs may have an impact on consumers’ decision-making processes (Nurhandayani, Syarief, & Najib, 2019; Zak & Hasprova, 2020). For this reason, strategic organization-SMI cooperation has become an integral component of marketing- and communication strategies of many companies (Enke & Borchers, 2019). This practice is labeled ‘Influencer Marketing’ and involves SMIs promoting brands’ products on their social channels, in return for cash payments or free products and services. To specify, commercial brands utilize the intimate and authentic relationship SMIs have with their followers, with the purpose of creating successful Word of Mouth Marketing (WOMM) and ultimately, affect target consumers’ purchase decisions (Kádeková & Holienčinová, 2018). Since consumers often associate certain brands with their celebrity endorser, the use of influencer marketing may not only add to brand attractiveness but also, brand trustworthiness and brand credibility (Djafarova & Trofimenko, 2017).

2.4 Social Media Influencer Authenticity

When discussing the increased interest in SMIs and Influencer Marketing, several scholars recognize that the notion of authenticity often serves as a central attribute (Vangelov, 2019; Kádeková & Holienčinová, 2018; Whitmer, 2019; Audrezet, de Kerviler, & Moulard, 2018; Essi, Pelkonen, Naumanen, & Laaksonen, 2019). The literature serves multiple meanings to authenticity, amongst them lies Whitmer’s (2019, p. 3) definition, which refers to authenticity as “an emotional, self-reflective experience

which encapsulates both the knowledge of what it is to be true to oneself and the subjective experience of being true or untrue to that self”. Similarly, Essi et al. (2019)

state that authenticity often revolves around what is true, genuine and real.

From a marketing perspective, however, authenticity is claimed to boost message receptivity, perceived quality, and purchase intentions, as consumers increasingly seek authenticity in the products and brands they consume (Audrezet et al., 2018). Moreover, drawing on the notions of authenticity and SMIs, research indicates that social media enables SMIs to create intimate and authentic relationships with their followers, leading

10

to a high level of engagement (Vangelov, 2019). Using a celebrity endorser, such as a SMI, to deliver a message, allows the recipient to identify with both the message and the sender (Essi et al., 2019). Moreover, social media facilitates communication through SMIs’ own words, pictures, or videos, making consumers feel more connected to SMIs (Essi et al., 2019). When consumers get a glimpse of SMIs’ everyday lives, it evokes a feeling of being less dissimilar to SMIs (Balaban & Mustățea, 2019). Not only does this lead to an increase in consumers’ trust towards SMIs but also, a decrease in status differences between consumers and SMIs; making SMIs seem like approachable persons (Schwemmer & Ziewiecki, 2018). Furthermore, in research conducted by Audrezet et al. (2018), it appears that SMIs manage authenticity by passionate communication and truthful report of their reality. In this sense, passionate communication refers to being committed to what they do, whereas truthful report refers to the consistency and sincerity of what is being reported (Audrezet et al., 2018).

Although the majority of the literature on SMI authenticity is focused on the importance of remaining authentic when developing a personal brand, Liu and Suh (2017) argue that the nature of self-branding is somewhat contradictory, as it promotes both authenticity and a business-oriented self-presentation. Likewise, Essi et al. (2019) indicate that SMIs are constantly pursuing a balance between remaining interesting and authentic, while sustaining economic profitability. Moreover, to construct a brand on an individual level, one must respond to the needs and interests of the mainstream market, which, due to the market-oriented features of self-branding, makes it hard to maintain authenticity (Liu & Suh, 2017). Therefore, regarding commercial content produced by SMIs, consumers occasionally find it difficult to differentiate honest opinions from those induced by economic incentives (Schwemmer & Ziewiecki, 2018). Furthermore, Khamis et al. (2016) indicate that consistency is another factor that becomes an issue when the concept of branding is applied to an individual. This is based on the rationale that consistency requires caution, authenticity, and avoidance of indiscretions, all of which being extremely difficult to ensure when the human factor is applied (Khamis et al., 2016). Therefore, the literature notes that the use of Influencer Marketing may harm an organization’s brand, due to personal indiscretions of SMIs (Sng, Au, & Pang, 2019).

11

2.5 The Reputational Asset and Image Repair Theory

This section will carve out the understanding of the value of reputation from the branding literature with a focus on two central concepts: reputation and image. Further, the relevant crisis communication literature is examined with a focus on reputation, based on the assumption retrieved from the brand management field indicating that brands are valuable assets differentiating companies from competitors (Rosenbaum-Elliott, Percy, & Parvan, 2015). Traditionally, brands are referred to as names, symbols, terms, designs or a combination of such, that identifies a product or service (Rosenbaum-Elliott et al., 2015). The connecting idea rooted in crisis communication is that reputation is an elevator of a brand image that has to be managed and protected in today’s volatile digital landscape where information spreads rapidly (Coombs, 2019). Moreover, in order to highlight the intangibility of brands, Keller, Aperia, and Georgeson (2012, p. 62) defines the concept of Brand Image as “...perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations

held in consumer memory.”

Another central concept for practitioners to comprehend and monitor is Brand Equity, which can be viewed from two perspectives: the financial perspective and the consumer-based perspective (Rosenbaum-Elliott et al., 2015). In terms of the financial value, brand equity is the asset value to a company that is built from strong positive associations held by stakeholders. Specifically, brand equity is built from presence in the marketplace and positive associations towards the brand. Further, regarding the consumer-based perspective, brand equity may be described as an amplifier of value to a brand that is built over time from triggers of strong emotional associations beyond rationality (Rosenbaum-Elliott et al., 2015). A definition that describes the consumer-based brand equity from a stakeholder perspective is provided by Rosenbaum-Elliott et al. (2015, p. 105) as follows:

“Brand equity from a consumer perspective results from awareness of a brand leading to brand knowledge and positive attitudes towards the brand, resulting in loyalty”.

In accordance, Coombs (2019) emphasizes the value of reputations and categorizes a favorable reputation as an intangible organizational asset formed by reputation management efforts to influence stakeholders. Therefore, a favorable stakeholder

12

relationship is a basic foundation for a positive reputation to meet or exceed stakeholders' expectations (Coombs, 2019). Moreover, Rosenbaum-Elliott et al. (2015) highlight the importance of acknowledging the human factor as an important brand touchpoint. To specify, a touchpoint is every interaction between the brand and a stakeholder, which combined forms the total brand experience. Rooted in this understanding, employee behavior is an influential perception shaper of the brand. Traditionally, corporate image is transmitted through four sets of perceptions held by: customers, employees, stockholders, and the media (Rosenbaum-Elliott et al., 2015).

Moreover, scholars and practitioners agree on several benefits resulting from a favorable reputation linked to the customer base, investments, attracting employee talent, increased job satisfaction, and positive media coverage (Coombs, 2019). Conclusively, these reputational benefits are built through experiences with the organization, positive interactions, and information about the positive character (Coombs, 2019). However, crisis management and communication scholars highlight the potential harm negative events may have on the reputational asset (Sng, Au, & Pang, 2019; Coombs & Holladay, 2015; Benoit, 1997). Furthermore, Coombs (2019) suggests that some common effects of reputational damage are:

1. Increased media scrutiny

2. Increased social media discussion 3. Decreased share price

4. Increased government scrutiny 2.5.1 Image Repair Theory

In harmony with what have previously been presented regarding brand images, Benoit (1997) argues that image is essential to all types of organizations and individuals; thus, there is a need to understand how to protect it. Nonetheless, there are certain differences between organizations and individuals in terms of the resources invested in image repair efforts. First, to be able to understand Image Repair Strategies (IRS), some assumptions must be presented (Benoit, 1997):

13

1. Image is only under threat if the accused is believed to be responsible for the act; 2. Perceptions are more important than reality: as long as the audience believes that

the offensive act is the organization's responsibility, the image is under threat. Secondly, Benoit (2015) presents two essential assumptions of the Image Repair Theory (IRT), which lay the foundation for IRS. The first assumption is that communication is a goal-oriented activity and is described as an intentional or instrumental act. The first building block is followed by a second assumption, that is built on the notion that an important goal in communication is to maintain a favorable impression. Moreover, because image and reputation are of utmost importance to individuals and organizations, humans are motivated to take action to protect it by applying IRS, also referred to as Crisis Response Strategies (CRS) (Benoit, 2015; Coombs 2019).

2.5.1.1 Apologies

Public figures, organizations, or spokespersons on behalf of an organization’s crisis response strategies and apologies, are recurring topics in crisis communication literature (Ismail, Pagulayan, Francia, & Pang, 2018; Crijns, Claeys, Cauberghe, & Hudders, 2017; Sandlin & Gracyalny, 2018). The emphasis is on realizing effective and ineffective strategies to respond to an organizational crisis in order to rebuild trust or lessen the damaging effect on reputations (Coombs, 2015; Coombs, 2019). As a result, several IRS exist to provide practical guidance and implications for managers drawn from research and case studies (Ismail et al., 2018). For instance, Crijns et al. (2017) suggest that gender similarities between the spokesperson and the audience may serve as a buffer when there is a reputational threat posed on the organization. The rationale is that gender similarities stimulate feelings of empathy that is supported by the verbal aspect in terms of response strategy (Crijns et al., 2017). Moreover, it appears that effective interpersonal verbal apologies generally include admittance of the wrongdoing, acknowledge of any damaged caused, remorse, and asking for forgiveness (Sandlin & Gracyalny, 2018; Benoit 1997). Furthermore, Coombs (2015) proposes five common components that may be damaged in times of a crisis, which are repeatedly studied in the crisis communication literature: (1) Reputation, (2) Emotion, (3) Purchase intention, (4) Stock prices, and (5) Word of Mouth (WOM). Moreover, there are some situational factors to understand in order to interpret the damaging effects of the different crisis components mentioned above

14

(Coombs, 2015). First, the degree of responsibility stakeholders attribute to the organization is important for the selection of response strategy. Second, long-term threats are valued as more serious than short term threats. Third, the concept of ‘Stealing Thunder’ acknowledges the potential benefit of being the primary source of information sharing, referring to the importance of timing. Lastly, the corporate reputation is built from an understanding of acts violating ‘competence’ and ‘integrity’. Whereby, stakeholders seem to be more accepting of incidents related to ‘competence’. The idea is that an incident is considered an accident and unintentional (Coombs, 2015). More specifically, Coombs (2015) suggests a framework connecting crisis situation, CRS, and

outcomes for guidance. However, it is noted that it is misleading to assume uniformity

between different crises; thus, each situation should be seen as unique to tailor the strategy to combat it (Coombs, 2015).

2.5.1.2 Prior Reputation

More recent research is built on Benoit’s work and the notion of a reputation as an important asset (Coombs, 2015; Crijns et al., 2017). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) may be broadly defined as an organization's image and efforts to fulfill its perceived obligations towards society (Jansen, Sen, & Bhattacharya, 2015). Admittedly, the concept of CSR has gained momentum as a positive attribute towards reputation (Lee, 2016). On the contrary, Coombs and Holladay (2015) challenge the idea that CSR acts as a reservoir of goodwill in times of an image crisis. Instead, the authors suggest that CSR efforts may have a ‘boomerang effect’ when confronted with allegations of social irresponsibility due to elevated public expectations. Specifically, the general perception that a strong CSR reputation is an asset in a crisis, is challenged by the idea that it can become a liability if managed poorly (2015). Additionally, Jansen, Sen, & Bhattacharya (2015) found that CSR may have three elevating damaging effects on reputation, attention to a crisis, attributions, and expectations. Firstly, it is proposed that companies with a strong CSR image are more likely to be reported in media in times of a crisis. Secondly, CSR may have a backfiring effect if stakeholders have doubts about the CSR motives. Thirdly, stakeholders' expectations may increase. The reasoning is that people expect these companies, or individuals, to exhibit honest behaviors, whereas less responsible companies are expected to behave on behalf of the situation (Jansen et al., 2015).

15

However, the literature leaves a gap for understanding how the prior reputation of individuals, such as SMIs, are being confronted with allegations of social irresponsibility. Similarly, Ismail et al. (2018) argue that individuals, such as political leaders, are under intense reputational threat when being attacked by opposition politicians and high media scrutiny.

16

3. Methodology and Method

______________________________________________________________________

This chapter scrutinizes the methodology and method chosen for this study, starting by outlining the methodology through the three following concepts: (1) Research Paradigm, (2) Research Approach, and (3) Research Design. Thereafter, the methods used for collecting and analyzing data are explained. Lastly, detailed considerations to the ethical aspects of the research are demonstrated.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research Paradigm

Research paradigms, or philosophies, answer some fundamental metatheoretical assumptions about reality and how research is conducted (Weber, 2004; Collins & Hussey, 2014). In particular, there are two distinguishing paradigms: positivism and interpretivism, both of which have strengths and weaknesses depending on the existing knowledge within the research area (Weber, 2004). Specifically, positivism aims to measure a social phenomenon, usually by adopting a quantitative method (Weber, 2004). In contrast, interpretivism is rooted in the assumption that social reality is context-bound and seeks to explore the complexity of social phenomena to gain deep understanding (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

The research questions of this study steer the researchers towards an interpretive perspective, meaning that the findings are derived and shaped by human perceptions and not statistical analyses of quantitative data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Moreover, this research aims to generate a deep understanding of how the participants perceive SMI brands when conjunct with allegations of indiscretions. Thus, the study is designed to contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the research topic, keeping in mind the rationale that there are multiple existing realities. Conclusively, the purpose is not to prove a predetermined theory about a phenomenon, nor to find evidence for a hypothesis, but to produce empirical data crafted from participants’ experiences, attitudes, and perceptions. Hence, the empirical findings should not be considered a generalized view of reality (Krauss, 2005).

17 3.1.2 Research Approach

Drawing on the notion of the interpretive perspective, an inductive research approach will be pursued for collecting data. This specifically means that theory will be the result derived from the empirical findings (Collins & Hussey, 2014). Additionally, the frame of reference, developed from the existing literature on SMIs, brand management, and crisis communication, will work as a guiding tool for analyzing the data. Moreover, while analyzing the data, the research team aspires to find meaningful patterns among the participants’ responses, reflecting their perceptions of SMIs’ brands when faced with negative publicity. Ultimately, it lies within the researchers’ ambitions that the knowledge acquired from this study will be applied as a practical communication strategy for SMIs when managing their brand during the events of a crisis. Thus, this research is distinguished from the deductive research approach, which is more common in quantitative research where theory testing is a central element (Mantare & Ketokivi, 2013).

3.1.3 Research Design

According to Wright, O’Brien, Nimmon, Law, & Mylopoulos (2016), rigorous research is conducted on the premise that there is a match between the research paradigm, research approach, and research method. In order to achieve this coherence, the researchers have chosen a qualitative research design to explore if, how, and to what extent the participants’ perceptions of SMIs brands are affected when conjunct with indiscretions. Additionally, the participants’ consideration of favorable elements in IRS for SMI brands will be investigated. Thus, the research questions are of qualitative nature and structure. Moreover, the research applies an interpretive worldview, an inductive approach, and ultimately, qualitative methods to collect and analyze data. More specifically, a quantitative approach would not be relevant for this research, since its purpose is to produce meaningful data about a phenomenon, and not to map various relationships between variables. Conclusively, the research team aspires to understand the underlying motives for participants’ responses, experiences, and attitudes to fill in the gaps in the literature; hence, entering new territory.

18

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Primary Data

According to Collis & Hussey (2014), primary data is collected from an original source without any prior manipulation. There are several primary data collection techniques, however, researchers should always bear in mind the purpose of the study when selecting their method (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Thus, due to the qualitative nature of this research combined with the researchers’ desire to obtain in-depth contributions, primary data was pursued by the arrangement of focus groups. The purpose behind the chosen method is that focus groups provide an ability for researchers to observe feelings or opinions in a certain group. Specifically, there may be a tendency to evoke and stimulate in-depth discussions (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Additionally, focus groups may be useful when conducting research that aims to explore and develop knowledge of an alternative perspective or novel field, which is in line with this study (Lotish, 2011). To further stimulate free expression of opinions, semi-structured interview questions were created. Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, and Jackson (2012) characterize semi-structured interviews as insightful and aimed at developing an understanding of participants’ worldview. However, before the arrangement of focus groups, the research team conducted a pilot study with two neutral individuals, to leave room for any adjustments in the interview questions and the overall structure of the focus groups.

In order to retrieve meaningful discussion, the participants were carefully selected based on a list of criteria. Specifically, the primary interest was taken in women, based on the premise that the SMI industry is mainly dominated by women and so are their follower bases (Kumpumäki, 2019). To further narrow the sample and to create a match between the participants and the research purpose, the sample had to meet four additional criteria: (1) they had to hold Swedish nationalities, since the SMI presented during the focus groups are Swedish, (2) they had to be in the ages between 18 and 30, since this range represents the cull of generation Y and Z who grew up with the internet and are legally considered as adults in Sweden (Business Insider, 2019), (3) they had to be active on social media platforms and follow SMIs on such, and (4) they had to follow at least one

19

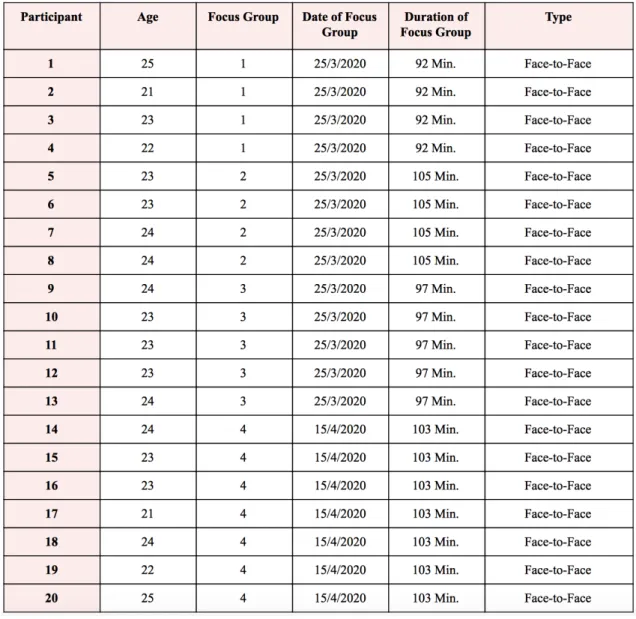

of the SMIs involved in the cases presented during the focus groups. The reason for setting the criteria to follow only one and not all of the involved SMIs, is that the researchers did not want to exclude the possibility that the participants had once followed several of them, but due to any reason, had chosen to unfollow (see Table 1).

Table 1: Participant Overview

3.2.2 Sampling Approach

The sampling procedure of this research included two major steps: to identify a sample of cases to be presented as subjects of discussion during the focus groups and to identify relevant participants. Both of which are explained in detail in the paragraphs below.

20

3.2.2.1 Sampling of Cases

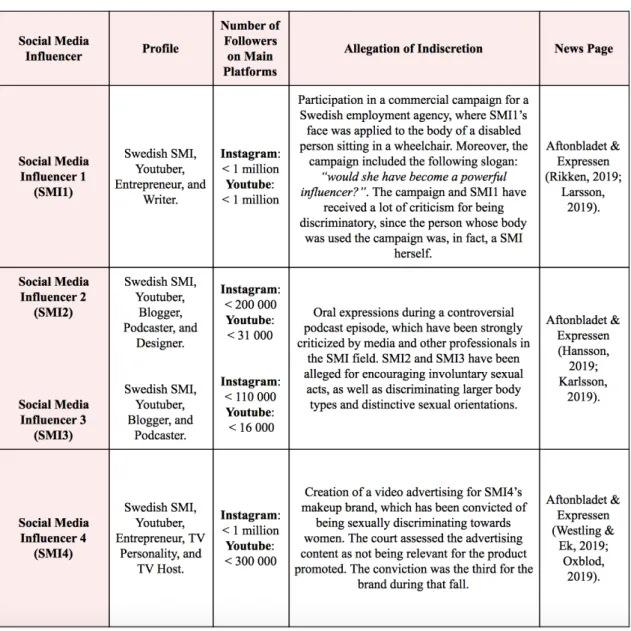

Regarding the sampling approach for selecting relevant cases to present during the focus groups, the researchers chose three different cases to provide real-life examples and to stimulate discussions. Specifically, three cases of allegations of indiscretions towards four SMIs were presented, one of which was targeted at two SMIs simultaneously, as they were involved in the same indiscretion (see Table 2).

Moreover, the cases had to meet certain criteria in order to be suitable for the research: (1) The cases had to be reported by the two most established news pages in Sweden, namely Aftonbladet and Expressen. This criterion was of importance since it increased the possibility that the participants were familiar with the indiscretion or held some sort of prior perceptions about the SMIs. Additionally, this criterion enabled the researchers to present the cases strictly from the media’s perspective by excluding own viewpoints and to avoid a biased perspective. (2) The news articles regarding the allegations of indiscretions had to be published somewhat recently and approximately during the same timeframe. Specifically, they were published between 2019 October 1 and 2019 December 13. This criterion enhanced the possibility that the participants still held emotions or opinions about the cases and found them relevant to discuss. (3) The SMIs conjunct with allegations of indiscretions had to be identified as females to create uniformity between the SMIs and the participants who similarly are identified as females. This was due to the aforementioned reason that the SMI industry is predominated by women, alike their follower bases (Kumpumäki, 2019).

Conclusively, the researchers selected three relatively distinct cases of indiscretions accompanied by different responses applied by the SMIs, with the motive to stimulate rich discussion and allow for comparison from different perspectives. Table 2 provides an overview of the three cases derived from media’s perspective. The summary regarding each case is an interweaving of news articles published online by Aftonbladet and Expressen. Additionally, the names of the SMIs have been replaced by Social Media Influencer 1-4 (SMI1-4), to provide some degree of discretion towards the individuals.

21

Table 2: Cases of Social Media Influencers Conjunct with Allegations of Indiscretions

3.2.2.2 Sampling of Participants

Regarding the sampling of participants, it is nearly impossible to reach an entire population, therefore, researchers normally identify a sampling frame from which the sample is drawn (Easterby-Smith et al., 2012). Hence, the chosen sample reflects a subset of an entire population (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The sampling technique adopted in this research was non-probability sampling, which means that instead of including random individuals in the study, specific participants were chosen based on the premise that the researchers aimed at gathering relevant primary data. Specifically, the study applied purposive sampling combined with snowball sampling as sampling approaches.

22

Purposive sampling refers to the practice of selecting participants based on the research purpose as well as specific characteristics of the individuals (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, 2016). This approach was applied since the researchers trust in their careful consideration and judgment in setting relevant criteria for selecting a suitable sample. Furthermore, snowball sampling refers to the recruitment of other participants, by the selected participants (Glen, 2014). This approach was applied due to two reasons: the researchers needed a relatively high number of participants to conduct the total number of focus groups and the researchers aspired to include individuals outside of their personal networks in order to minimize bias of opinions. However, these individuals would only be approved as participants for the study given term that they met the same criteria as those set for the participants within the purposefully chosen sample.

3.2.3 Focus Groups

As aforementioned, the popularity in using focus groups as a data collection technique is rooted in their ability to generate rich discussions among participants. Moreover, the literature suggests three types of focus groups, namely, full group, mini group, and telephone group (Greenbaum, 1998). Although the different types have several common traits, their main distinguishers are concerned with their number of participants, as well as their settings. Nevertheless, the type of focus group chosen for this research falls in the category of the mini group, meaning that it is constructed around a discussion of approximately 90 to 120 minutes led by a moderator, involving 4 to 6 participants (Greenbaum, 1998). The reason for the choice of data collection technique is grounded on the premise that group discussions encourage participants to share insights between one another, which may lead to the emergence of conclusions that may not have been reached from the use of individual interviews.

Moreover, four focus groups were arranged in total as the researchers took into account the scope and the feasibility of the study. Specifically, the researchers continued the data collection until recurring themes were identified. To confirm the prior findings and to capture distinguishing perspectives, a final focus group was conducted. Additionally, to demonstrate appreciation and respect towards the participants’ time, the date and time set for the focus groups were adjusted according to their personal schedules. Furthermore, the researchers aimed at constructing the focus groups in such a way that there would not

23

be too many individuals within one group who knew, or were familiar with, one another. The purpose behind this strategy was to prevent groupthink and bias of opinion to the possible extent. However, the researchers did not completely exclude arrangement of focus groups where a few individuals were familiar with one another due to the belief of having a personal relationship to at least one other member may bring a sense of safety and comfort, and thus, more open and honest expression of opinions. Ultimately, due to the importance of the participants' contributions, the focus groups were audio-recorded, and notes were taken throughout the sessions. This was incorporated to ease the transcription process as well as to capture meaningful data and responses.

3.2.4 Interview Questions

The structure and set of questions derived from findings in the frame of reference and the pilot study. Furthermore, emphasis was placed on retrieving honest responses from the participants related to the research topic. The interview questions designed for the focus groups were semi-structured, meaning that the participants govern the direction of the interview, as the questions usually tend to be open-ended (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The reason for constructing semi-structured questions is grounded in the researchers’ aim to allow for an open discussion and to capture participants' perceptions (Easterby-Smith et al., 2012).

The structure of the focus groups along with the questions was based on 5 main sections: The session started with an introductory part, where the purpose of the study and its ethical aspect were explained. The following section included a rapport building session, which aimed at ensuring the participants comfort. Thereafter, questions related to the background of the topic were asked. Subsequently, the questions became more in-dept, to stimulate opinions and encourage discussions. Following, the three cases of SMI indiscretions were presented along with a set of questions related to each. This segment was aimed at relating the study to practical examples and to support or evoke emotions within the participants. Lastly, the sessions were concluded with questions aimed at collecting general perceptions and practical implications (see Appendix 3).

24 3.2.5 Data Analysis

According to Collis & Hussey (2014), the choice of data analysis method is dependent on the research paradigm. Hence, due to the qualitative nature of this study, as well as the desire to present findings in a clear, systematic manner, the researchers created data displays using a thematic approach. Specifically, since thematic analyses are based on predominant thoughts, ideas, and attitudes derived from participants’ contributions, they enable identification of meaningful patterns in qualitative datasets (Braun & Clarke, 2012, Chapter 4). Additionally, the thematic approach allowed the researchers to connect empirical findings to the frame of reference.

To illustrate how the thematic analysis was systematically executed, a step-by-step process is outlined. First, transcripts of the primary data were produced in order to get familiarized with the contributions generated by the participants. According to Austin & Sutton (2015), transcribing data may help facilitate the later stages of the analysis due to the clear display of transcripts. Subsequently, specific codes were assigned to the responses of the participants to further analyze the data. According to Braun & Clarke (2012, Chapter 4), codes are straightforward and allow researchers to categorize data into different groups that share common characteristics, which may be helpful when identifying links and patterns. From the codes, specific themes were developed, enabling connections between the data retrieved and the research questions. As a consequence of the emerged themes, it became of great importance to evaluate the overall relevance of the research topic in relation to the empirical findings, to arrive at an understanding of how the data may be interpreted (Braun & Clarke 2012, Chapter 4). Furthermore, associations between the themes were investigated and the researchers described their inferred meanings. Ultimately, the findings were presented in a clear, transparent manner, establishing new insights and contributions to the literature on the research topic.

25

4. Ethics

Ethics may be defined as a set of rules and beliefs about right and wrong behavior within

a society. These rules and beliefs include boundaries of generally accepted behavior and norms, which work as some sort of moral code (Reynolds, 2012). Furthermore, in the context of business research, ethics is a critical element that governs the entire research from start to end, reflecting the credibility and validity of the study (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2007). Therefore, this study has ensured to work in harmony with the sense and morale of the literature on ethics in business research.

First and foremost, the research team had to overcome the challengeof gathering free-willed participants to the focus groups. Therefore, the researchers approached individuals within the selected sample via social networks. A standardized message was sent to these individuals, stating the purpose of the study, as well as the expected contributions from the participants. The message also informed the individuals about the estimated time, anonymity, and confidentiality of the study. In addition, due to the spread of the Covid-19 virus, a disclaimer was added to the message, stating that if any symptoms were felt, the individuals should disregard from the request.

Further, if the responses were positive, the researchers invited the individuals to a closed Facebook group, where details about date and time were set. As mentioned, a pilot study was conducted with the purpose of enabling possible justifications while ensuring that there would be no infringement of privacy of the participants. Additionally, the locales at Jönköping University were selected as setting for the focus groups, providing the participants with comfort and easy access due to the central location of the university. Moreover, to ensure that the participants were aware of their rights, they were handed a consent agreement (see Appendix 4) prior to the focus groups, assuring their privacy, including anonymity and confidentiality. However, since the data collection revolves around focus groups and not individual interviews, it was important to note that although anonymity is guaranteed in the research, it is difficult to control the discretion of other participants. Lastly, the agreement rigorously emphasized the, during any point of the data collection stage, right to decline to answer to questions as well as withdraw from the study (Saunders et al., 2007)

26 4.1.1 Confidentiality and Anonymity

Confidentiality and anonymity are two essential principles during the data collection stage

that are often confused with one another (Saunders et al., 2007). Distinguishing the two concepts, confidentiality refers to the protection of information provided by research participants, whereas anonymity concerns the protection of their identities (Saunders et al., 2007; Bell & Bryman, 2006).

Before and during the data collection stage, confidentiality was ensured by informing the participants about the secure handling and storage of data. In specific, the contributions would be accessible exclusively to the research team. The procedure of assuring this practice included password protection of the device in which the information was carried, as well as elimination of all participants’ data after the completion of the study.

Since confidentiality is closely linked to anonymity, the research team offered to conceal any identifying information of the participants (Bell & Bryman, 2006). As the quality of this study does not depend on the identity of the participants, their names were replaced by a character and a number. The rationale behind this practice was to transmit a trustworthy impression towards the participants and thus, encourage openness and free expression of opinions (Collis & Hussey, 2004).

4.1.2 Credibility

Another key ethical aspect refers to the level of trustworthiness of research, which may be enhanced by establishing credibility (Cope, 2014). According to Koch (2006) and Cope (2014), a study is deemed as credible when researchers interpret and describe in detail their experience as researchers. For this to be achieved, it requires the researchers to hold some degree of awareness (Koch, 2006). Therefore, the demonstration of self-awareness of the research team and the credibility of this research, is three-fold:

Firstly, during the initiation phase of the research process, the researchers engaged in learning as much as possible about methods of business research. Additionally, prior to the data collection process, the researchers acquired deep knowledge about the research topic, which is demonstrated in the frame of reference (Cope, 2014). Secondly, careful considerations were made to each step of the data collection process, including rigor

27

management of the focus groups to add to their credibility as a data collection technique. Thirdly, on several occasions during the research process, the researchers attended tutoring seminars where peer-observations were made. This was executed by regularly debriefing with a tutor and several opponent teams, enabling neutral and honest feedback (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

4.1.3 Transferability

The degree to which empirical findings are applicable to similar settings or groups, is scrutinized in the concept of transferability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). However, transferability is particularly relevant if the study aims to make generalizations about a phenomenon, which is rarely the case of qualitative studies (Cope, 2014). This is because qualitative research often involves smaller, purposeful samples that are put in specific contexts from which the data is generated (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Thus, due to the qualitative nature of this study, generalization is not the intent of its results. On the contrary, the emergence of the research topic is grounded in the lack of existing literature on brand management and crisis communication applied to the chosen context. To clarify, there is a richness of literature on brands as reputational assets; likewise, there is a richness of literature on the social media influencer profession; however, there is a lack of literature on the merging of the two phenomena. Hence, the purpose of this study is not to conduct research that is transferable between different settings, but to bring together two broad concepts and place them in an entirely new setting.

4.1.4 Dependability

Dependability refers to the fixedness of the data over different circumstances. Frankly, a

study is considered dependable if the research findings are similar or at least comparable regardless of the researcher’s profile (Koch, 2006). Lincoln and Guba (1985) suggest that the criterion for research to be dependable is the auditability of its process. Therefore, the researchers have aimed at conducting the research in such a systematic, transparent, and clear manner as possible. To further enhance the replicability of the study, the researchers individually analyzed the data before further discussions of the findings with one another. This did not only allow the researchers to gain individual in-depth understandings of the contributions but also, it decreased groupthink and selectivity of the findings. Moreover, once the researchers confirmed the findings with each other, they developed specific

28

codes and themes based on common grounds. Lastly, the aforementioned tutoring sessions allowed for neutral peer-researchers to evaluate the overall implementation and compliance of the research.

4.1.5 Confirmability

Another ethical consideration revolves around the maintenance of objectivity in the data collection process, which is coupled with the notion of confirmability (Collis & Hussey, 2014). It is important to bear in mind that qualitative data often derive from dialogues between researchers and participants and therefore, the analyzes are to some extent based on the researcher’s interpretation. However, to demonstrate that the data represent the participants’ responses, it is of utmost importance that the data collection is performed accurately and thoroughly (Saunders et al., 2007). In practice, this means that the researchers must avoid selectivity and bias of what is reported and completely exclude own viewpoints. This is not only to assure that the data represent the perspective of the participants without impact from the researchers but also, to add to the validity and reliability of the research (Cope, 2014).

Given the relatively high number of participants (20) in this study, the data were derived from multiple individuals discussing the same phenomena. This enabled the researchers to gain a deep understanding of the participants’ perceptions of SMIs’ in the chosen context. Additionally, direct quotes from the participants are provided to clearly demonstrate that the findings are derived directly from the data (Cope, 2014). Ultimately, transcripts and audios from the focus groups are safely stored, however, available in case the confirmability of this study was to be questioned.

29

5. Empirical Findings

______________________________________________________________________

This chapter represents the empirics derived from the focus groups. A brief background of the participants is provided, followed by a systematic demonstration of the primary data, designed to enhance the comprehension of the analysis with regards to RQ1 and RQ2.

______________________________________________________________________

5.1 Background

As aforementioned, the participants of this study were all considered young females, with a mean age of 23.2 (Urban Dictionary, n.d.). Moreover, a brief description of each participant is found in Table 3. The table presents straightforward data regarding the participants’ social media habits, including why and to what extent the participants are engaged with the phenomenon of SMIs. Specifically, the table showcases an approximate number of SMIs followed by the participants, as well as which of the presented SMIs the participants followed at the time of the research. The data were derived from the brief questionnaire which was handed out during the focus group sessions (see Appendix 5). Furthermore, to trace patterns and links in the dataset, excerpts from the focus groups will be made, and each participant’s contribution will be communicated as ‘Participant #’ or (P#).

Throughout the data collection process, it became clear that a strong motive to why the participants are extensively engaged in the phenomenon of SMIs, is rooted in deep, personal relationships.

“I feel like the deal with influencers is that they are supposed to be like your friends online. You can follow them and follow their lives. Humans are curious in nature.” (P4)

30

31

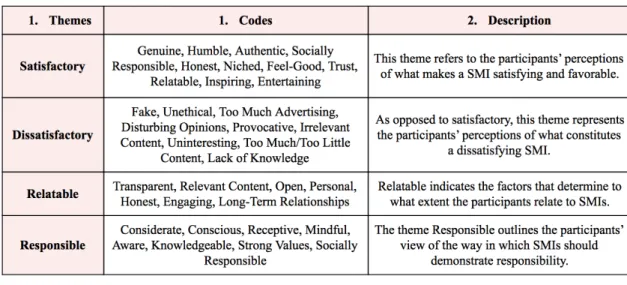

5.2 Social Media Influencer

During the introductory part of the focus groups, the participants were asked to describe a SMI according to their personal viewpoints. At this stage, it became evident that the participants’ portrayals of SMIs were homogeneous. Specifically, the participants described SMIs as individuals who influence, affect, and inspire other people via their social media platforms.

“Someone who can affect many people and when they make a statement, they influence a large audience.” (P6)

“I also think of someone who can establish feelings within someone else, both good and bad ones of course.” (P9)

Moreover, the participants claimed that SMIs have large follower bases on their various platforms and that their main focus is to market themselves and other brands via these platforms.