Doctoral Thesis

T

The

he

importance

importance

of

of

psycho

psycho

log

log

ica

ica

l

l

and

and

phys

ica

l

stressors

on

d

iabetes

phys

ica

l

stressors

on

d

iabetes-

-re

lated

immun

ity

in

a

young

re

lated

immun

ity

in

a

young

popu

popu

lat

lat

ion

ion

–

–

an

an

interd

interd

isc

isc

ip

ip

l

l

inary

inary

approach

approach

Emma

Car

lsson

Jönköping University School of Health and Welfare Dissertation Series No. 072, 2016

Doctoral Thesis inHealth and Care Science

The importance of psychological and physical stressors on diabetes-related

immunityin a young population– an interdisciplinary approach

Dissertation Series No. 072

© 2016 Emma Carlsson

Publisher

School of Health and Welfare

P.O. Box 1026 SE-551 11 Jönköping Tel. +46 36 10 10 00 www.ju.se Printed by Ineko AB 2016 ISSN 1654-3602 ISBN 978-91-85835-71-3

I

t´s

no

t

wha

t

you

look

a

t

tha

t

ma

t

ters

,

i

t´s

wha

t

you

see

4

Acknow

ledgements

I wouldlike to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Maria Faresjö and my

co-supervisors Arne Gerdner and Anneli Frostell. Thank you for engaging myintellect

and my thoughts and challenging me to try to comprehend knowledge that is beyond

my teachings. I enjoy every moment of our discussions, whether research-related or

just plain small talk. I would alsolike to thank Johnny Ludvigssonforletting mebe a

part of the ABIS project.

To my parents, Jerker and Lena; thank you for your endless support and for

encouraging us to grow up as strong,independent women. I am forever grateful for the

solid foundation you have given me. I couldn´t have done this without you!Ilove you!

My sister and mirrorimage, Hanna. Thank you for the laughter’s in good as well as

bad times and for all the mischiefin between. Imagine having someone your own age

to play withfrom day one. Brilliant! Ilove you!

Piff and Puff, Bill and Bull, H1 and H2, Bea and Ulla. Thank you for always reminding

me that work is just work and thank you for making me laugh loudly and heartfelt

every day. You two arejust completely, utterly and wonderfully crazy.

To my brilliant friends from Värnamo and Jönköping. I really do have the most diverse

group offriends and you are all a source ofinspiration! Thank youfor understanding

mylack of presence the past couple of years. I vow to you all that I will be much more

present from now on.

To my colleagues at Mikrobiologen, Molekylärbiologen, Utvecklingsenheten and

Jönköping University. You are the definition of hard work and dedication. Thank you

allforletting me come play oncein a while:-)

Finally, Marcus; my best friend, mylover, and my plutt. Either we´reinlove or we´re

at war. I wouldn’t haveit any other way! Let’s keepliving ourlife our way and never

"rättain ossiledet". Let’s not have a single boring day,let’s never say never andlet’s

keep appreciating the smallest of things. Ilove you!

Last but notleast, I wouldlike to acknowledge the author of this thesis, myself! For

achieving what I set out to do. Nowlet’s move on to new adventures:-)

5

Abstract

Background: The prevalence of immunological disorders such as type 1 diabetes (T1D) is increasingly common amongst children, adolescents and young adults. There is also an increase in psychosomatic symptoms (depression, insomnia, anxiety, headaches and fatigue etc.) as well as a decreasein physical activity amongst young people, affecting the well-being and overall health of our younger population. It is therefore important to study the effects of psychological and physical stressors on the immune system, to evaluate theirimpact onjuvenile health.

Aim: This thesis explores the impact of psychological and physical stressors on the cellularimmune system with specialfocus on diabetes-relatedimmunity in a young population, using aninterdisciplinary approach.

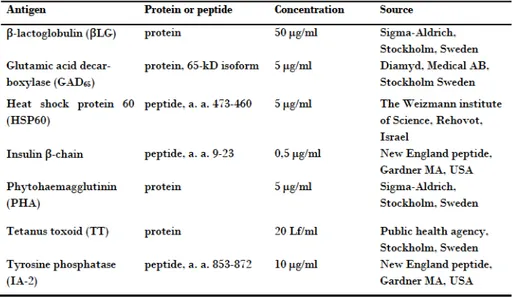

Method: When exploring theimpact of psychological and physical stressors such as psychological stress due to exposure to psychological stressful experiences or degree of physical activity/training on the cellular immune system in children, adolescents and young women, peripheral blood mononuclear cells(PBMC) were stimulated with antigens(tetanus toxoid(TT) and β-lactoglobulin (βLG)) as well as diabetes-related autoantigens (insulin, heat shock protein 60 (HSP60), tyrosine phosphatase-2 (IA-2) and glutamic acid decarboxylase 65(GAD65)) and secreted cytokines and chemokines were

measured by multiplexfluorochrome technique(Luminex). Populations of T -helper (Th) cells (CD4+), T-cytotoxic (Tc) cells (CD8+), B cells (CD19+),

Natural Killer (NK) cells (CD56+CD16+) as well as regulatory T (Treg) cells

(CD4+CD25+FoxP3+CD127-), and their expression of CD39 and CD45RA were

studied by flow cytometry. Diabetes-related parameters (glucose, C-peptide, proinsulin, pancreatic polypeptide and peptide YY) were measured to study β-cell activity and appetite regulation and cortisol was used as a biological markerfor psychological and physical stress.

Results: Children in families exposed to psychological stress showed an imbalanced cellularimmune response as well as anincreasedimmune response towards diabetes-related autoantigens. Also, previous exposure to psychological stress as well as current exposure to psychological stressin young women showed an increased immune response towards diabetes-related autoantigens. Further, previous exposure to psychological stress in young

6

women showedincreased numbers of circulating CD56+CD16+NK cells as well

as decreased numbers of circulating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+CD127-Treg cells.

High physical activity in children showed decreased spontaneous immune response as well as a decreased immune response towards diabetes-related autoantigens, while low physical activity in children showed an increased immune response towards diabetes-related autoantigens. Further, endurance trainingin adolescents, especiallyin adolescent males and young adolescents, showed an increased immune response towards the diabetes-related autoantigen IA-2.

Conclusion: It is evident that psychological and physical stressors such as exposure to psychological stress and degree of physical activity/training impact the cellularimmune system.Experiences associated with psychological stress seem to have a negative effect on the cellularimmune systemin a young population, causing animbalancein theimmune system that could possibly induce diabetes-relatedimmunity. High physical activityin children seems to have a protective effect against diabetes-related immunity. In contrast, low physical activity in children and endurance training in adolescents seems to induce diabetes-relatedimmunity. Itis verylikely that psychological stressful experiences, low physical activity and intense training such as endurance training all playimportant rolesin theimmunological processleading to the development of type 1 diabetes.

7

Or

ig

ina

l

papers

The thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to by their Roman numeralsin the text:

Paper I

Emma Carlsson, Anneli Frostell, Johnny Ludvigsson, Maria Faresjö (2014). Psychological stress in children may alter the immune response. Journal of Immunology 2014:192:2071-2081.

Paper II

Emma Carlsson, Anette Magnusson, Andrea Tompa, Per Bülow, Arne Gerdner, Maria Faresjö (2016). Psychological stress affects the numbers of circulating CD56+CD16+ and CD4+CD25+FoxP3+CD127-cells and induce an

immune response towards type 1 diabetes-related autoantigens in young women. Submitted.

Paper III

Emma Carlsson, Carina Huus, Johnny Ludvigsson, Maria Faresjö (2015). High physical activityin young children suggests positive effects by altering autoantigen-inducedimmune activity.Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Sciencein Sports 2016:4:441-50.doi:10.1111/sms.12450.

Paper IV

Emma Carlsson, Louise Rundkvist, Peter Blomstrand, Maria Faresjö(2016). Endurance training during adolescenceinduces a pro-inflammatory response directed towards the diabetes-related autoantigen tyrosine phosphatase-2. Manuscript.

The articles have been reprinted with the kind permission of the respective journal.

8

Contents

Acknowledgements ...4 Original papers ...7 Contents...8 Abbreviations ...11 Introduction ...14 Background ...15Aninterdisciplinary approach ...15

Type 1 diabetes ...18

An autoimmune disease ...21

Theimmune system ...22

Cells of theimmune system ...27

Natural killer cells ...27

T-helper and T-cytotoxic cells ...27

Regulatory T-cells ...29

Cytokines and Chemokines ...30

Psychological stress ...31

Measuring psychological stress ...32

Psychological stress and theimmune system ...34

Physical activity, exercise and training ...35

Measuring physical activity, exercise and physical fitness ...37

Physical activity/exercise and theimmune system ...37

Psychological stress, physical activity and training as stressors ...41

Rationaleforthisthesis ...42

Aims ...43

Materials and methods ...44

Design and context of 4 papers – in 3 projects...44

Participants ...46

Paper I ...47

Paper II ...47

Paper III ...48

9

Questionnaires ...50

Paper I ...50

Paper II ...52

Paper III ...53

Paper IV ...54

Internal consistency ...54

Laboratory analyses ...55

Separation and cryopreservation of PBMCs(Papers I-IV) ...55

In vitro stimulation of PBMC(Papers I-IV)...56

Multiplexfluorochrome technique(Luminex)(Papers I-IV) ...57

C-peptide, proinsulin, pancreatic polypeptide and peptide YY (Papers II, IV) ...58

C-peptide and proinsulin (Papers I-IV) ...59

Flow cytometry (Paper II) ...59

Cortisol(Papers I, II and IV) ...60

Glucose (Paper I) ...61

Maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) (Paper IV)...61

Statistical analyses ...62

Ethical considerations ...63

Results ...64 Paper I...64 Paper II ...67 Paper III ...70 Paper IV ...71 Discussion ...74

Methodological reflections ...75

Type II error ...75

Immunological methods ...75

Timing and type of psychological stress ...76

Cumulative effect of endurance training ...78

Psychological stress ...78

10

Psychological stressin young women ...80

Physical activity and training ...82

Physical activityin children ...82

Endurance trainingin adolescents ...83

Confoundingfactors ...85

Theinfluence of gender and age ...85

Summary offindings ...89

Conclusion ...90

Clinical and researchimplications ...91

Sammanfattning på svenska ...92

11

Abbrev

iat

ions

APC Antigen presenting cell βLG β-lactoglobulin

BMI Body massindex

BNP Brain natriuretic peptide BSA Bovine serum albumin BSA Body surface area

CCL Chemokine(C-C motif)ligand CCR C-C chemokine receptor CD Cluster of differentiation CNS Central nervous system

CXCL Chemokine(C-X-C motif)ligand CXCR Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor DC Dendritic cell

DMSO Dimethyl sulfoxide Fc Crystallizablefragments FCS Fetal calf serum

FITC Fluoresceinisothiocyanate FOXP3 Forkhead box protein 3 FSC Forward scatter

12

GAD Glutamic acid decarboxylase GH Growth hormone

HbA1c Hemoglobin A1c

HPA Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal HSP Heat shock protein

IA-2 Tyrosine phosphatase-2 IFN-γ Interferon-gamma

IGF-1 Insulin-like growthfactor-1 IL Interleukin

IP-10(CXCL10) Interferon gammainduced protein-10 MCP1(CCL2) Monocyte chemotactic protein 1

MIP-1α (CCL3) Macrophageinflammatory protein-1alpha NK Natural killer

PBMC Peripheral blood mononuclear cell PBS Phosphate buffered saline

PE Phycoerythin

PerCP Peridinin-chlorophyll proteins PHA Phytohaemagglutinin

PP Pancreatic polypeptide PYY Peptide YY

RT Room temperature

13 SSC Side scatter T1D Type 1 diabetes T2D Type 2 diabetes Tc T cytotoxic Th T helper

TNF-α Tumor necrosisfactor-alpha Tr1 Type 1 regulatory

Treg T regulatory TT Tetanus toxoid WBC White blood cell

14

Introduct

ion

Alarming development over the past decade show an increase in immunological disorders such as diabetes, and the impact of type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes (T2D) on individuals, families, communities and health systems are staggering. The World health organization(WHO) predicts that diabetes will be the 7th leading cause of death in 2030 (1). Around 50000

childrenin Sweden are diagnosed with T1D and every day 2 new children are diagnosed. Unfortunately, the cause of manyimmunological disorders such as T1Dis stilllargely unknown and cannot be prevented with currant knowledge. Therefore, it is important to study different environmental factors, such as psychological and physical stressors that could perturb the immune system. There is also an increase in psychosomatic symptoms (depression, insomnia, anxiety, headaches andfatigue etc.) as well as a decreasein physical activity amongst young people, affecting the well-being and overall health of our younger population. In 2014, alargeinternational study,initiated by WHO showed that children and teenagers report an increase in psychosomatic problems and that especially young teenage girls report poorer mental health than teenage boys (2). The study also states that young people’s physical activity remains verylow and that the gap between sedentaryjuveniles and highly physically activejuveniles areincreasing (2). Both sides of the spectrum cause for concern as both low physical activity and extensive exercise could have a negative impact on the health and well-being of young people. The studies involved in this framework taps into the dimensions of mental and physical health, exploring the effects of psychological stress and degree of physical activity/training on the cellularimmune system, with specialfocus on diabetes-related immunityin a young population, using aninterdisciplinary approach.

15

Background

An

interd

isc

ip

l

inary

approach

The current definition of health,formulated by WHOin 1948, describes health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease orinfirmity”. The definition includes the bio- psycho-social nature of human existence as well as the dynamic relationship between the demands made on anindividual´slife and his or hers ability to meet them (3).

This thesis uses an interdisciplinary approach when exploring the impact of psychological stress or degree of physical activity/training on the cellular part of the immune system with focus on diabetes-related immunity. As a theoretical background tointerdisciplinary research, the philosophy of Mario Bunge was applied (4). Mario Bunge states that the explosion of the artefactual (e.g. computers) progress over the past decades, allowing us to share information and knowledge; does not in itself create new knowledge. Artifacts do not explore the outer world and do notinvent newideas or theories that explain or predict newfacts. Nor doesit possess the curiosity, the moral judgement and the critical mind of man thatisfundamentalin the presence of good science. Studying concrete things or phenomena asif they were simple andisolated, and workingin a single discipline asifit had no relatives worth looking into, can only get us so far, and even lead us astray. The unity of science throughinterdisciplinary research will take usfurther. Interdiscipline, a researchfield that overlaps two or more disciplines, sharesideas and methods and postulate hypotheses that bridge the original disciplines and paradigms. Biophysics, biochemistry, socioeconomics, psychoneuroimmunology are only a few cases of interdisciplinary research fields known to be very valuable in studying different phenomena.

Bunge states that every concrete thing orideais a system or a component of a system that involves composition, environment, structure and mechanism. The composition of a systemisits parts, the environmentis the collection of things that act on a system andits components and the structureis the relation ofits components as well as among the components and the environment.

16

To understand a phenomenon, we can´t simply explain the phenomenon, we are required to explore it´s inner mechanism, to understand what makes it “tick”. Mechanism is the collection of processes that makesit whatitis and affect howit gets transformed. All mechanisms do not have to be causal. The systemic model pictures man as a system composed of numerous subsystems (Figure 1), each with its own specific functions, as well as components of suprabiological(i.e. social) systems such asfamily.

This model acknowledges physical and chemical properties, as well as biological, psychological and social ones. Humans can feel, dream, imagine, plan, and enter into social relations – all of which are beyond physics and chemistry, although they are rooted to the physical and chemical properties of living tissue. The components of every system belonging to alevel above the physical one also belong tolowerlevels. As we climb up thelevelladder, we gain some properties but alsoloose other properties. For example, the social levelis composed of animals butis not an organismitself(biologicallevel). The human organism can be studiedfrom different viewpoints: as a physical entity, a chemical system, a biological organism, a psychological being and a component of a social system (e.g. school, family, workplace etc.). Each approach has its shortcomings and suggests a one-sided view of man. Restricting the study of man to the physical approach restricts the study of man to physical components and aspects andignores whatever physicsfail to explain. The chemical approach to study a phenomenonis all but perfect and a good example is that we still do not have a complete and adequate understanding of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecule. The biological approachis a veryimportant approach to adoptinlife science and should be combined with other approaches rather than excluding them. The biologism tends to overlook the social dimension of human life and to mere look at a neuron, for example, would be to overlook the complexity and understanding of the nervous system as well as the mental and social peculiarities of humans. Sociobiology may account for some human features as survival devices acquired by genetic change and natural selection. The psychological approach strives to understand behavioural, emotional, cognitive and volitional patterns. All such functions whether inborn or learned are biological, performed by organs. Thereby, the mental is bound to be psychobiological. Sociological consciousness, work and language seem to be products of social life; so are moral conscience and organizational ability.

17

Figure 1. Modified version of Mario Bunge’s “hierarchical” organization of a systemthat goes uptothe world systems and downto a physicallevel. The systemic modelinvolves numerous subsystems, each withits own specificfunctions, as well as components of suprabiological (i.e. social) systems such as family. This model acknowledges physical and chemical properties, as well as biological, psychological and social ones. DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid, CNS = Central nervous system

Behaviour

Individuals

Supersystems(e.g. CNS, immune system)

Physicallevel

World systems

Society

Social groups

Organs(e.g. pancreas)

Cells(e.g.lymphocytes, neurons)

Organelles(e.g. ribosomes)

Molecules(e.g. DNA, cytokines)

Atoms

Elementary particles

Sociallevel

Psychologicallevel

Biologicallevel

Chemicallevel

18

The “hierarchical” organization of a system goes up to the world systems and down to a physical level (Figure 1). Anything within a certain level is composed of things belonging to alowerlevel. For example; organis composed of cells thatis composed of organelles. Everythingin a systemis connected and a multilevel approach allows one to use different techniques, models and data. This thesis explores parts of theimmune system on a biologicallevel,including thelevels below (chemicallevel and physicallevel) and howitis affected by stressors such as psychological stressful experiences and degree of physical activity/training. Both psychological stress and degree of physical activity/training have biological parts (biological level) as well as emotional and behavioural aspects(psychologicallevel). Both phenomena are developed in social contexts and highly influence the social interactions between individuals (social level). Psychological stress and degree of physical activity/training challenge both biological and psychological paradigms as well as the social paradigm. Therefore, this thesisis ofinterdisciplinary nature, challenging the boundaries of different paradigms. Although my own professional standpoint and experienceis within thefield of biology, this thesis requires me to move up theladder (psychological and sociallevels) to explore psychological and physical stressors, as well as down the ladder (chemical level) to explore different mechanisms.

Type

1

d

iabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a complex metabolic disorder whose main diagnostic featureishyperglycaemia due toinsulin resistance, defectiveinsulin secretion and destruction of the insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells in the islets of Langerhans (5). Two major groups of diabetes-mellitus have beenidentified as type 1 and type 2. Type 2 diabetesis a complex metabolic disorderin which β-cell failure occurs simultaneously with insulin resistance where the body becomes resistant to the insulin it produces, and have been associated with westernlife-style habits such as sedentary behaviour and energy-dense diet (5). Type 1 diabetes wasfirst describedin 1550 B.C. as “the passing of too much urine”. Around the same time Indian physicians classified and described the disease as honey urine. The term “diabetes” which in Greek means “to pass through” was first used 250 B.C. by the Greek physician Apollonius (6).

21

Other factors, such as hormones, can affect insulin sensitivity. Growth hormone(GH) andinsulinlike growthfactor -1(IGF-1) are for example higher during adolescents than during pre-pubertal and adult years (19). Plasma IGF -1 levels are regulated by GH, which is a potent insulin antagonist, and hypersecretion of GH is associated with insulin resistance (20). Growth hormoneinhibits phosphorylation of theinsulin receptor as well asinhibiting signalling moleculesin response toinsulin administration,leading to reduced insulin sensitivity (21). High levels of GH also leads to excess lipolysis and mobilization offreefatty acids, whichinhibits glucose oxidation by acting as a competitive energy source, and thereby worsening insulin resistance (21). Further, IGF-1 is thought to enhance insulin sensitivity as part of the GH/IGF-1-axis feedback loop, where high values lead to lower insulin resistance due to lower levels of GH. Therefore, elevated levels of GH in adolescent yearsinduce a transientinsulin resistance (20), which suggests that the influence of environmental factors on the immune system could be influenced by age. Type 1 diabetesis often regarded as a homogenous disease, which might explain why immune interventions to preserve β-cell function havefailed to reach endpoint. Patients with T1D are oftenlumped togetherin clinical trials irrespective of sex, age, ethnic origin, geographical area, social environment etc. More knowledge on environmentalfactors thatinfluence β-cell function is therefore necessary. At diagnosis of T1D, most children and adolescents have some residualinsulin secretion. Preservation of C-peptide, the connecting peptide that is connected to insulin in the precursor proinsulin molecule, has been regarded as a relevant endpoint of preservation (22). Levels of C-peptide seems to be related toless acute andlate diabetes complications (23), which makes it an important research target for preservation of β-cell function.

An

auto

immune

d

isease

An

auto

immune

d

isease

Type 1 diabetes is caused by a lack of self-tolerance, preceded by an autoimmune destruction of theinsulin-producing β-cellsin pancreas (24). The first autoantibodies described in the progression of T1D were islet cell autoantibodies (ICA) (25). Subsequently, antibodies against insulin (IAA), tyrosine phosphatase (IA-2A) and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) have been observed (26-28). Thelatest autoantibody describedin patients diagnosed

22

with T1D are directed towards a specific β-cell zinc transporter (SCL30A8, ZnT8), where the amino acids arginine(R), tryptophan(W) and glutamine(Q) have been described (29). All these autoantibodies can beidentified during a subclinical period, years before the clinical onset of T1D, which makes these markers valuable as predictors for type 1 diabetes (25). The initial stage in insulitis, whichis still very much unknown,is the sensitization againstβ-cells antigens. Immune cells will present diabetes-related autoantigens(e.g.insulin, GAD65, IA-2 and HSP60) to theimmune system which willinitiate animmune

response,leading toinflammationin theislets of Langerhansin pancreas (30) followed by β-cell destruction.

The

immune

system

The immune system is crucial for our survival and protects us from foreign, harmfulinvaders such as viruses, bacteria,fungi, parasites and cancer and also induceimmunologic memory, and develop tolerance to self-antigens (31). Itis able to produce and activate an enormous variety of different white blood cells (WBC) and components that interact with each other to initiate an appropriate response to eliminateforeignintruders. Functionally, thisimmune responseinvolves the two related activities, recognition and response (32). The recognition process involves cell surface molecules that specifically bind to other specific molecules with particular structures, called antigens, and thereby discriminate betweenforeign antigens and the body´s own antigens. Antigens (antibody generator [Ag]) e.g. chemical substances, proteins, lipids, carbohydrates etc. are molecules capable ofinducing animmune response. This molecular recognitionis the underlying principle of the discrimination process between “self” and “non-self”. When a foreign antigen is recognized, the immune system activates a repertoire ofdifferentimmune cells and molecules to eliminate theintruder, called an effector response. Later exposure to the same foreign antigen will induce a rapid and enhanced immune response called a memory response, hopefully eliminating the foreign intruder before disease onset.

27

Ce

l

ls

of

the

immune

system

Several different immune cells are of interest when exploring environmental factors such as psychological stress or degree of physical activity and their influence on theimmune system. Theimmune system andits cells were briefly introduced above. Below, some of these immune cells are introduced more thoroughly.

Natura

l

k

i

l

ler

ce

l

ls

Natura

l

k

i

l

ler

ce

l

ls

Natural killer cells, primitive killer cellsin theinnateimmunity, possess the ability to both lyse target cells and provide an early source of immunoregulatory cytokines(44). Human NK cells comprise approximately 15 per cent of PBMCs and are defined phenotypically by their expression of the markers CD16(or, FcγRIIIA, low-affinity receptor for the crystallisable fragment(Fc) part ofimmunoglobulin G(igG)) and CD56(adhesion molecule mediating homotypic adhesion) (45). The two major subsets of human NK cells consists of CD56dimCD16+which have low-density expression of CD56

(CD56dim) and high expression of CD16(CD16+) and CD56brightCD16dim/- (46).

T

T-

-he

he

lper

lper

and

and

T

T-

-cytotox

cytotox

ic

ic

ce

ce

l

l

ls

ls

To maintain homeostatic balance, theimmune system keeps a subset of white blood cells. A highlyimportant subset of WBCis the Th cells(CD4+),focused

on directing and helping other cells in the immune system. Upon antigenic stimulation, naïve CD4+T cells activate, expand and differentiate into

different effector subsets characterized by the production of distinct cytokines and chemokines (Figure 4) (47, 48).T helper 1 cells mobilize the cellular part of theimmune system to combatintracellular pathogens, as well as activate cytotoxic and inflammatory responses and delayed-type hyper-sensitivity reactions (38, 39). T helper 1cells produce cytokineslikeinterferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosisfactor-β (TNF-β) (48)and are stimulated byinterleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, IFN-γ and TGF-β (38, 39).

28

T helper 2 cells areinvolvedin activation of B-cells, eosinophilfunction and proliferation as well as phagocyte-independent host defence(38, 39). T helper 2 cells secrete especially IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 and are stimulated by IL-2 and IL-4 (38, 39, 48). Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ, exert aninhibitory effect on Th2-cells while Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 inhibits Th1 proliferation (49). Studies have shown that T1D patients have a lymphocytic dominance in pancreas, and that the dominanceis of IFN-γ secretinglymphocytes (50). This indicates that T1D has a Th1 profile,whichis alsoinline with studies showing that high-riskfirst-degree relatives have a Th1 profile several years before the actual disease onset (51). The subpopulation of Th17 cells has beenidentified as one of the major pathogenic Th cell populations, involved in many autoimmune diseases (52). Th17 cells produce mainly IL-17 (53) and coordinate tissueinflammation byinducing theinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alfa (TNF-α) (54). IL-23, produced by activated DCs, appears to be the critical driver behind Th17 activation and the subsequent production of IL-17 (55, 56). T cytotoxic cells (CD8+) destroy cells

that expressforeign antigens on their surface, cells that areinfected with virus and certain cancer cells (57). T cytotoxic cells can further be divided into subgroupsin the same way as Th cells by the cytokines and chemokines they produce (58). CD4+and CD8+ T-cells differentiatefrom naïve cells to central

memory andlater on to effector memory cells. Memory CD4+and CD8+ T-cells

are characterized based on CD27 and CD28 expression andfurther subdivided into naïve and/or effectors by expression of CD45RA+ (Table 1) (59). C-C

chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7), a receptor important in T- and B-cell migrationinto secondarylymphoid organs (60, 61)play animportant rolein induction and maintenance of central and peripheral tolerance(62, 63). Table 1. Differentiation of memory CD4+and CD8+ T-cells.

Surface marker Expressed by CD27+CD28+CD45RA+CCR7+ Naïve T cell

CD27+CD28+CD45RA-CCR7+ TCM

CD27+CD28+CD45RA-CCR7- TEM(early differentiation)

CD27-CD28-CD45RA-CCR7- TEM(late differentiation)

29

Thus, memory CD4+and CD8+T-cells can be subdivided based on CD27 and

CD28 expression and further by differentiated expression of CD45RA and CCR7into naïve T cells, central memory T cells (TCM), and effector memory T

cells (TEM) by early differentiation, late differentiation or as terminally

differentiated(TEMRA)(Table 1) (64).

Regu

latory

T

Regu

latory

T-

-ce

ce

l

l

ls

ls

Regulatory T cells play an important role in the prevention of autoimmune diseases, allergies and graft versus host disease (GvHD) by suppression and regulation of T cells and other immune cells(65-67). Regulatory T cells also maintainimmune balance and self-tolerance and have the ability to regulate the Th1/Th2 balance by suppressinginduced cell deviation (68). Regulatory T cells develop in thymus and express CD4+and CD25+ on their surface (69).

Several cytokines and markers have been associated with Treg, among them forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) and the cytokine IL-10, a cytokine produced byimmunosuppressive Type 1 regulatory T cells(Tr1)(Figure 4) (68, 70). The transcriptionfactor FOXP3, a specific marker in mice but notin humans have shown to be the best markerfor Treg sofar (71). CD127, a marker negatively correlated to Tregis down regulatedin all T-cells and FOXP3+CD127-cells are

highly representedin peripheral blood (72). CD39is expressed on FOXP3+cells

and are known to suppressinflammation andis therefore a suitable markerfor Treg (73).Three different populations of cells expressing CD45RA and FOXP3 have beenidentified; CD45RA+FOXP3loware characterizedfor resting Tregs,

CD45RA-FOXP3high are characterized for activated Treg and CD45RA

-FOXP3loware expressed on non-suppressive Tregs, making CD45RA a suitable

markerfor Treg activity (74). CD101, expressed on e.g. activated T-cells (75), has shown to be highly correlated with functional suppressor activity within CD4+CD25+Treg cells both in vitroand in vivo (76)and CD129, expressed on

T-cells, may also beimportantfor regulation since this marker is critical for early stages of human intrathymic T-cell development (77). Activated Treg cells express low levels of CD45RA and CD127 and can both be used to distinguish different types of Treg cells (74, 78). Taken together, CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD127- T-cells may be further characterized by the

30

Cytok

ines

and

Chemok

ines

Cytok

ines

and

Chemok

ines

Immune cells secrete small proteins,i.e. cytokines and chemokines, which help coordinate the immune response throughout the body (79). Cytokines act as small signalling molecules to regulate inflammation and modulate cellular activities such as growth, survival, and differentiation (80)and chemokines are a group of secreted proteins within the cytokine family whose function is to induce cell migration through the process of chemotaxis (81, 82). Cytokines and chemokines are usually classified by the type of cells that secrete them, but they can also be classified according to their pro-and anti-inflammatory properties. Pro-inflammatory cytokines e.g. IL-1 and TNF-α,are known to be involvedininflammation, while IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 are anti-inflammatory cytokines while the cytokine IL-6 have both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties (83, 84). Newly diagnosed children with T1D have shown to have increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (85). Plasmalevels of pro-inflammatory and Th1 cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, may be upregulatedin T1D patients (86-89). Th1-cells express chemokine receptors chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor(CXCR) 3 and C-C chemokine receptor (CCR) 5, which is receptors for chemokines such as chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10)and CCL3 (90) and Th2-cells expressi.e. chemokine receptor CCR4, whichis receptorsfor chemokines such as CCL2 and CCL3(90). The pro-inflammatory chemokine IL-8, also known as CXCL8,is often associated with tissueinjury and disordersinvolving chronic inflammation(91, 92)andis animportant neutrophil chemotactic protein (93).

31

Psycho

log

ica

l

stress

The word stressis often usedin a modern sense when expressing time-pressure or too much to do. Although we might regard stress as a rather modern phenomenon,itis certainly not. Claude Bernard, a French physiologist, used the phrase “milieuintérieur”in several of his worksfrom 1854 until his death 1878 to explain that maintenance oflife depend on keeping theinternal milieu constant in the face of a changing environment (94). In 1929, Cannon (95) called this “homeostasis” and in 1956 Selye (96) used the term “stress” to represent the effects of anything that seriously threatens homeostasis. The perceived threat on an organismis described as a “stressor” and the response described as a “stress response” and these stress responses have evolved to be adaptive processes. Selye further observed that a prolonged severe stress response, known today as chronic stress, might lead to tissue damage and disease (96).

An organism will perceive a change in the environment as threatening/challenging or benign/irrelevant, a process known as appraisal (97). If the environmental change is appraised as a threat or challenge, the organism will useits behavioural systems to activate the appropriate response. The appraisal in humans may range from mere reflex to a fully conscious analysis of the problem at hand (97). While reflexes are more orless genetically encoded, cognitive appraisal rely on previous, similar experiences. If the organism successfully meets the challenge, the environment may change, so that the threat is neutralized. This may occur by fighting or fleeing or by meeting the challenge by successful courting orfood seeking. These changes of the environment will downregulate the activated systems. Without a response or environmental change, there would be no stress. To fully capture the essence of stress, one need to consider the stress processin terms of external challenges, perception of the challenge, coping resources and perception of coping resources and how these interplay over time (98). The adaptive response to challenging conditionsis known as the allostatic process, an adjustment process to maintain homeostasisin the body (99), mediated through allostatic systems (nervous, endocrine and immune system) (100). This process includes faster breathing,increased heart rate (HR), constricted blood vessels and tightening muscles (101). The adaptive response is positive in the short run but can be detrimental in the long run. Chronic and/or repeated activation of the

32

allostatic systems, cumulate the homeostasis burden and is termed allostatic load(99, 102, 103). Thisis known as negative chronic stress. Therefore, stress can be both positive and negative, where positive stress prepares the bodyfor survival while negative stress could be detrimental to our health.

Measur

ing

psycho

log

ica

l

stress

Measur

ing

psycho

log

ica

l

stress

Most research refers to environmental challenges as psychological or physical stressors. For a challenge to be a stressor,it needs to be perceived as one. As described above, stressful conditions initiate a coping process to maintain homeostasisin the body. This processinvolves the nervous system as well as the immune system. The major neuroendocrine response to stress is via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (104), where stimulation of the HPA axis increases the glucocorticoid (e.g. cortisol) secretion(105). Researchfocus when measuring cortisol, as a biological markerfor stress, has been the relationship between stressors such as psychological stressful experiences and the activation of the HPA axis.

There are numerous self-reporting psychometric tests to evaluatefactors(e.g. parenting stress, stressful life events etc.) that could influence the level of negative psychological stressin children as well asin adults. In this thesis we examine negative psychological stress as a result of exposure to psychological stressful experiences (referred to as psychological stress in this framework) such as childhood maltreatment, stressfullife events, parenting stress,lack of social support, parental worries and currently perceived stress to evaluate the level of psychological stressinfamilies with young children as well asin young women. Childhood maltreatment has been extensively used as a factor in studying the aetiology in psychological, physical and social problems (106 -109). In this thesis we used items regarding emotional abuse and emotional neglect from the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). Emotional abuse have a negative effect on the child´sintellectual and emotional development, leading tolow self-trust,lack of social competencein close relationships, fear of doing wrong and could implement feelings of not being loved (110). Emotional neglected children tend to be passive and socially isolated, developing problemsin relating to other people (110).

33

Therefore, emotional abuse and emotional neglect are reliable measures for measuring psychological stress in childhood. Childhood adversities can be measured with accuracy and are good measuresfor psychological stress (111) and are also associated with adultinflammation andincreased risk ofischemic heart disease (107, 108, 112). Also, a meta-analysis by Baumeister et al. showed that childhood trauma contributes to an inflammatory state in adulthood, with specific inflammatory profile depending on the type of trauma (106). Other studies have shown that childhood maltreatment can predict adult inflammation(107, 108). Further,several studies have shown that problematic and stressfullife events have animpact on the over-all health and are therefore a reliableinstrumentfor studying the association between stressfullife events and disease (113-116). Serious life events experienced by mothers have also been associated with an increased risk of diabetes-relatedimmunityin children (115), and early stressful life events are known to influence a variety of physical health problemslaterinlife (117).

When using self-reporting psychometric test to evaluating psychological stress in young children, questionnaires including items associated with psychological stress are answered by the child´s caregiver. Children´s psychological stress differsfrom adultsin that children are very sensitive to parental moods and behaviour (118). According to Bowlby´s attachment theory, infants must maintain physical proximity to their caregiver for survival (118). Therefore, psychological stressin the child’s caregivercould be transferred to the child. Itis therefore useful to study psychological stressin parents to be able to assess psychological stress in children. Scales such as parenting stress, lack of social support, stressful life events and parental worries have all been used in previous studies to measure parent’s psychological stress (115, 119-123). Parenting stress, described as a condition where the different aspects of parenthood results in a perceived discrepancy between demands and personal resources, are known to have negative effects on both child and parent andincreased parental stress have been associated with poor infant sleep, colic, childhood infections (124) as well as d iabetes-relatedimmunity (123). Studies havefurther shown that social support works as a buffering factor for parental stress and is known to increase personal resources when faced with external stressors and has been shown to reduce parenting stress (125). Lack of social support can therefore be a riskfactorfor psychological stress.

34

Parental worries concerning the offspring´s health are part of the criteriafor anxiety disorders (126) and worries are included in various anxiety scales. Some parents may be overinvolved and overprotective because they worry too much about negative events (127), which has been related to children developing internalizing problems (127). Also, parental worries have been related to anxiety,and excess maternal worries about children´s health may be associated with a diminished attachment pattern (128). Prior research has also shown that currently perceived stress influencestheimmune system and is associated withimpaired antibody response toinfluenza vaccinein young adults (113).

Psycho

log

ica

l

stress

and

the

immune

system

Psycho

log

ica

l

stress

and

the

immune

system

Theimpact of psychological stress onimmunefunction has been the subject of extensive research efforts (114, 129, 130). The effect of a particular stressor on immune function varies according to the previous stress experience of the individual, while various stressors may actin the same orin opposite ways on the sameimmune parameter. The kind and the magnitude ofimmune response depend on several factors, including the severity and the duration of the stressor, and the ability of theindividual to cope (131). In 2004, alarge meta -analysis of almost 300 independent studies over 30 years indicated that psychological stress was associated with suppression of the immune system (132) and with a number of immunological diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (133), allergic disease (134), atopic dermatitis (135) and celiac disease (136). A number of studies have also found that serious life events during thefirst two years of a child’slifeincrease the riskfor T1D (115, 123, 137). Immune cells contain receptors for and respond to neurotransmitters, neuropeptides and hormones secreted by sympathetic neurons and/or adrenal medulla. At a molecular basis, these effects involve a network of multidirectional signalling and feedback regulations between mediators of neuroendocrine and immune cells. Studies over the past decades have demonstrated a profound relationship between the nervous system and the immune system. Since the two systems are said to regulate each other reciprocally,findings have given rise to thefairly newfield of study known as psychoneuroimmunology.

35

Although chronic stressis known to be harmful,itisimportant to remember that a stress response has adaptive effects in the short run. Therefore, the biological effect of stressis distinguished by the duration of the elevated stress response. During acute stress, physiological systems work in synchrony to enable beneficial response. Dahbhar and McEwen (1997, 2001) stated that acute stressors would cause a redistribution of immune cells into compartments where they are most efficient against invaders (138, 139). Several studies have shown that acute stress significantly enhances both innate and adaptiveimmunefunction by anincrease of NK, Th, Tc and B cells (140, 141)andin 2009, Freier et al. (142)showed that subjects undergoing an acute mental stressor have a decreased number of Treg cells. Short term stress is also known to increase circulating levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in humans (143). This type of short-term stress response is generally adaptive and induces an immunoprotective response against wounding, infection, cancer or vaccination (144). In contrast to acute stress, chronic stress has been shown to dysregulate immune function (129, 145) by altering the Th1/Th2 balance (146)andincreasingimmunosuppressive mechanisms (e.g. Treg) (129, 138, 145-148). Further, chronic stress is also known to dysregulate immune function by promoting pro-inflammatory and type 2cytokine driven responses (146).

Phys

ica

l

act

iv

ity

,

exerc

ise

and

tra

in

ing

Physical activity, exercise, training and physicalfitness, are terms often used in research exploring physical health. Physical activity and exercise have some components in common such as bodily movement, energy expenditure from low to high, and a positive correlation with physicalfitness(149). Exercise and training alsoinclude structured and repetitive movement that considered more strenuous than physical activity and is often performed with a conscious objective toimprove or maintain physical fitness (149). If physical activity, exercise and training are related to the movements thatindividuals perform, then physicalfitnessis an attribute that people have or try to achieve. There is also a distinction between exercise and training, although the two concepts are often used synonymously. Exercise is performed for the purpose of producing a physical stress to satisfy theimmediate need of the exerciser,like burning calories, getting sweaty, increase maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max)

36

etc. and may wellinvolve doing the same thing at every workout. For athletes and people with a definite performance objective, trainingis necessary. In this context, trainingis physical activity performed to satisfy afuture goal, andis therefore more focused on the goal-oriented process rather than the actual workouts themselves. Since this process need to generate a definable result at a given endpoint, the process at hand must be planned to produce satisfactory results. Training may therefore be the most successful exercise plan to achieve the goals that many people seek through exercise. In the current thesis we use the term training wheninvestigating the effects of endurance training on the cellularimmune systemin adolescents and we do not refer to the adolescents as athletes because of their young age. There are a number of components that can be measured to evaluate physical fitness in relation to health such as cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular endurance, muscular strength, body composition and flexibility (149). Substantial evidence suggests that regular physical activity reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes and other diseases (150-152). Thus, regular physical activity is often recommended to adults as well as children with chronic diseases such as asthma, obesity, T2D and also T1D patients (153-155). We know that children and adolescents, who practice healthy living habits, prevent health problemslaterinlife (156). Thisis ofimportance since the global prevalence of e.g. obesity among children and young peopleis dramaticallyincreasing (157) as well as overweight amongst young peoplein Sweden (158). In addition to physical health benefits, several studies suggest that regular physical activity can benefit emotional well-being, byimproving mood and reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety (159, 160). Depression and anxiety being the most common psychiatric conditions observed in medical settings (161, 162). Regular physical activityis also known to decrease depressive symptoms by an increase in brain neurogenesis in the same way as anti-depressant medications (163)as well as having a positiveimpact on mood byincreasing adrenocorticotropic hormone(ACTH) and decreasing cortisol (164).

37

Measur

ing

phys

ica

l

act

iv

ity,

exerc

ise

and

phys

ica

l

Measur

ing

phys

ica

l

act

iv

ity,

exerc

ise

and

phys

ica

l

f

f

itness

itness

When studying degree of physical activity and training and its effect on biological systems such as theimmune system, one has to consider the type of physical activity/training as well as the intensity and duration. Research involving young children (ages 0-6) often study physical activity as the amount of time the childisin motion, either through questionnaires or report cards answered by the parents, through observational studies or the use of pedometers (165, 166). Pedometer can be used to measure physical activityin both children and adults andis a device thatis attached to the hand or hip and counts each step a person takes by detecting motion (166). There are several other ways of measuring physical activity or exercise in older children, adolescents and adults, among them differentfitness tests(e.g. treadmill and cycle), traininglogbooks (167)to asses training volume or use questionnaires concerning degree of physical activity, exercise and training. To evaluate physical fitness in relation to physical activity, exercise and training, maximum oxygen uptake(VO2max) and HRis often used.

Phys

ica

l

a

Phys

ica

l

act

ct

iv

iv

ity/exerc

ity/exerc

ise

ise

and

and

the

the

immune

immune

system

system

Several studies over the past decades have shown that physical activity and exerciseinfluence theimmune system (168-171). Theintensity, duration and the type of physical activity/exercise/training can all influence various immune parameters also associated withinflammatory diseases(172-174). The relationship between exercise and susceptibility toinfectionis often modelled in theform of a “J”-shaped curve(Figure 5) (175).This model suggests that, while engaging in moderate activity immune function may enhance above sedentary levels but excessive amounts of prolonged, high-intensity exercise may impair immune function. Although there is little evidence suggesting significant differencesinimmune function between sedentary and moderately activeindividuals, thereis some convincing evidence that moderate physical activity is associated with a decreased risk for infection (175). It has been reported that two hours of regular moderate exercise per day reduce the risk of upper respiratory tract infection by 29 per cent (176). In contrast, intense exercise such as ultra-marathon,increase the risk ofinfection by 100-500 per centfollowing a competitive race (177, 178). Many studies have reported that

38

variousimmune cellfunctions areimpaired temporarilyfollowing acute bouts of prolonged, continuous heavy exercise, and athletes engaged in intensive periods of endurance training appear to be more susceptible toinfections(175, 179-181).

Figure 5. Relationship between degree of exercise andthe risk ofinfection.

During acute exercise (i.e. single exercise session), leukocyte subsets such as neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes as well as various cytokines (e.g. TNF- , IL-1, IL-6 and IL-10) canincrease to various magnitudes (182, 183). During acute exercise thereis anincrease of differentimmunological markers, such as the cytokines IL-6 and TNF- (172, 173, 184, 185) and after strenuous acute exercise e.g. a marathon race, TNF-, IL-1 and IL-6 increase dramatically(186) as well as the chemokine IL-8(185). This pro-inflammatory releaseis simultaneously balanced by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.

INTENSITY RI S K OF I NF E CT I O N High F I NF Average Low Moderate

41

Psycho

log

ica

l

stress

,

phys

ica

l

act

iv

ity

and

tra

in

ing

as

stressors

Stressors are known as stimuli thatinduce psychological and physical distress, leading to a disturbedbodily homeostasis. Psychological stress,low physical activity and intensive training can all be considered stressors. A short-term stress response (e.g. acute psychological stress and acute exercise) activate physiological systems that arefundamentalfor survival. This stress response prepare theimmune systemfor challenges such as wounding and healing(131) and will return to its initial state after the stress response decline. Most organisms,including humans, are exposed to a series of acute stressorsinlife, that willinduce bouts ofimmune responses which willlater return to baseline after cessation of stress. When the stressor becomes chronic such asfrequently repeated exposure to psychological stressful experiences or intense training sessions, the physiological systems (e.g. immune system) will not have sufficient time to recover between stress exposures,leading to adverse health effects. Low physical activity could also be considered a chronic stressor, since itis often associated with poorlife style choices. In contrast, regular physical activity or moderate exercise or trainingis associated with health benefits. It is apparent that both psychological stress and physical activityis beneficial as long as homeostasis is retained and the physiological systems have enough time to recover between exposures to the different stressors. During conditions where exposure to psychological stress, low physical activity and intense training becomes chronic, homeostasis is not able to recover, resulting in prolonged immune responses, which could possibly induce immunological disorders and possibly autoimmunity.

42

Rat

iona

le

for

th

is

thes

is

Diabetes (T1D and T2D)is a universal concern where the number of people diagnosed with the disease has risenfrom 108 millionin 1980 to 422 millionin 2014 (206), and westill don´t know what triggers theimmune system to attack theinsulin-producing β-cellsin T1D. Thisis very unfortunate since diabetesis a serious disease which can resultin serious complications. Research exploring possible riskfactorsfor developing T1Dis therefore veryimportant and much needed. Also, the pervasiveness of psychological stress and physicalinactivity in young people cause for alarming developments. Several studies have investigated the impact of psychological stress or degree of physical activity/exercise on immune function in adults (169, 207, 208). Far fewer studies have explored theinfluence of psychological stress or degree of physical activity/training in young people and with the range of immunological markers used in this thesis. Further, to our knowledge no studies have investigated the impact of the timeframe when the psychological stress was experienced and the immune response in a young population. Also, the majority of studies that investigate the effect of endurance training collect blood samples after the stimulation of exercise, but in the current thesis we collected blood samples after 24 hours’ rest to be able to explore the effect of endurance training on cellularimmune activity at baseline. This thesis uses an interdisciplinary approach that transcends the paradigm of biology thatis the bodily manifestation of T1D and explores several different levels (physical, chemical, biological, psychological and social) to try to understand the aetiology behind the phenomenon. Both mental and physical conditions during childhood and adolescence are very important for the overall health and well-being throughout life, and thus, this project can bring important pieces of knowledge concerning juvenile health.

43

A

ims

The overall aim of this thesis is to explore the impact of psychological and physical stressors on the cellular immune system with special focus on diabetes-related immunityin a young population, using an interdisciplinary approach.

The specific aims are:

• To examine how psychological stress in the family, influences the cellular immune system in children, with special focus on d iabetes-relatedimmunity(Paper I).

• To examine how psychological stress,in differentlifespans,influences the cellular immune system in young women, with special focus on diabetes-relatedimmunity(Paper II).

• To examine how physical activity versus a sedentary lifestyle in childreninfluences the cellularimmune system, with special focus on diabetes-relatedimmunity(Paper III).

• To examine how endurance training influences the cellular immune systemin adolescents, with special focus on diabetes-relatedimmunity (Paper IV).

44

Mater

ia

ls

and

methods

Des

ign

and

context

of

4

papers

–

in

3

pro

jects

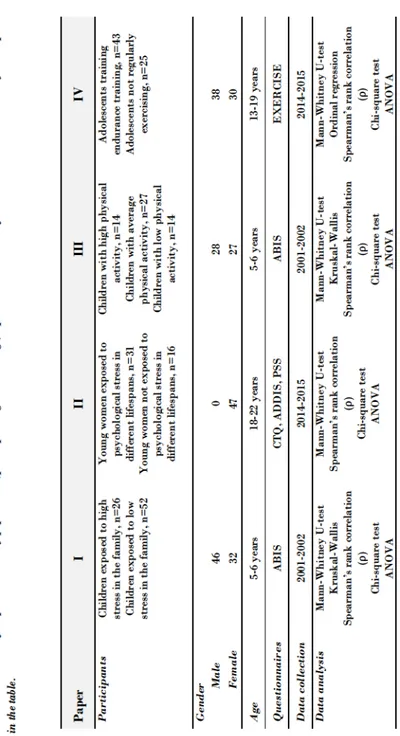

This thesis has a cross-sectional, explorative design with quantitative methods. The different study populationsin this thesis(Paper I–IV) consist of four different cohorts from 3 projects. The cohorts in Paper I and III are childrenfrom the All Babiesin Southeast Sweden (ABIS) project (Linköping University, Linköping). The cohortin Paper IIinvolves young women from the study Impact of stress project(Jönköping University, Jönköping) and the cohortin Paper IVincludes adolescentsfrom the Exercise project (Jönköping University, Jönköping). An overview of the papers can be foundin Table 2. Data collection in the ABIS project took place at the well-baby clinic in southeast Sweden during 1997-1998. Data collection in the Impact of stress project took placein the Youth Health Centre in Jönköping during 2014-2015 and data collection in the Exercise project took place in the Department of Clinical Physiology, Region Jönköping County in Jönköping during 2014-2015. The laboratory work in this thesis was performed at the Division of Medical Diagnostics, Region Jönköping County in Jönköping. Experienced nurses and biomedical scientists collected blood samples and the samples were then transported to the laboratory. Researchers involved in the studies provided participants in the four studies with written and oral information. The research team also handed out the questionnaires to the informed participants.

45 Ta bl e 2. Ov er vi ew o f Pa pe r I-I V. St ud y po pu la ti on ( pa rti ci pa nts , g en de r an d ag e) , q ue sti on na ir es, ti me of da ta c oll ect io n an d da ta a na ly si s ar e pr es en te d in t he ta ble . Pa pe r I II II I IV Pa rt ic ip an ts Ch il dr en e xp os ed t o hi gh st re ss in t he f a mil y, n= 26 Ch il dr en e xp os ed t o l o w st re ss in t he f a mil y, n= 52 Yo un g wo me n ex po se d t o ps yc ho lo gi ca l s tr es s i n dif fe re nt lif es pa ns, n =3 1 Yo un g wo me n no t ex po se d t o ps yc ho lo gi ca l st re ss in dif fe re nt lif es pa ns, n =1 6 Ch il dr en wit h hi gh p hy si ca l ac ti vit y, n= 14 Ch il dr en wit h av er ag e ph ysi ca l ac ti vit y, n =2 7 Ch il dr en wit h l o w ph ysi ca l ac ti vit y, n= 14 Ad ol es ce nt s t ra in in g en du ra nc e t ra in in g, n= 43 Ad ol es ce nt s no t r eg ul arl y ex er cis in g, n= 25 Ge nd er Ma le 46 0 28 38 Fe ma le 32 47 27 30 Ag e 5-6 ye ar s 18 -2 2 ye ar s 5-6 ye ar s 13 -1 9 ye ar s Qu es ti on na ir es A BI S CT Q, A D DI S, PS S A BI S E X E RC IS E Da ta c oll ec ti on 20 01 -2 00 2 20 14 -2 01 5 20 01 -2 00 2 20 14 -2 01 5 Da ta a na ly si s Ma nn -W hit ne y U -t es t Kr us ka l -W all is Sp ea r ma n’s r an k co rr el ati on (ρ ) Ch i-sq ua re te st A N O V A Ma nn -W hit ne y U -t es t Sp ea r ma n’s r an k co rr el ati on (ρ ) Ch i-sq ua re te st A N O V A Ma nn -W hit ne y U -t es t Kr us ka l -W all is Sp ea r ma n’s r an k co rr el ati on (ρ ) Ch i-sq ua re te st A N O V A Ma nn -W hit ne y U -t es t Or di na l r eg re ssi on Sp ea r ma n’s r an k co rr el ati on (ρ ) Ch i-sq ua re te st A N O V A

46

Part

ic

ipants

ABIS project

The cohortsin Paper I and III are from the “ABIS project”. The ABIS project aims to increase the knowledge about different factors contributing to the development of diseases such as T1D, T2D, celiac disease, allergies, asthma etc. It is a prospective cohort study including children in southeast Sweden (the counties of Jönköping, Kalmar, Östergötland, Kronoberg and Blekinge). The inclusion criterionfor ABIS was that the child was bornin southeast Sweden during 1stOctober 1997 and 31stOctober 1999. In ABIS, 17055 children were

included after their parent gave informed consent. Questionnaires and biological samples have been collected at birth, 1 year, 2-3 years, 5-6 years, 8 years and 11-13 years.

Impact of stress project

The cohort in Paper II is from the “Impact of stress project” which investigates how psychological stress,in differentlifespans,influences mental and physical health in young adults. In 2014-2015, 147 young adults (18-22 years old), both men and women were recruited from the Youth clinic in Jönköping. Questionnaires and biological samples were collected following informed consent.

Exercise project

The cohortin Paper IVincludes adolescents from the “Exercise project” which investigates theimpact of endurance training on theimmune system and the cardiovascular system. In 2014-2015, 68 adolescents (13-19 years old), both boys and girls were recruitedfrom orienteering clubs and schoolsin and around the area of Jönköping. Questionnaires and biological samples were collected followinginformed consent.

47

Paper

I

Paper

I

Seventy-eight children (5-6 years old) from the ABIS project wereincludedin Paper I. Twenty-six children (6 girls and 20 boys), exposed to psychological stress(referred to as high psychological stressin the published article and also as high-stressed children)in the family (families exposed to three or four of the domains; parenting stress, lack of social support, serious life events and parental worries) and a group offifty-two(26 girls and 26 boys) children not exposed to psychological stress (families exposed to none of the domains) were selected to represent a group of high-stressed children and a control group of low-stressed children. Due to limited numbers of blood samples, the distribution of boys and girlsin the group exposed to psychological stressin the family was not equal. The control group was further divided into two control groups(C and C1). Control group C, consisting of 26 children, 13 girls and 13 boys had no exposurein any of thefour stress domains,irrespective of heredity or signs of autoimmunity. Control group C1, consisting of 26 children, 13 girls and 13 boys, who were not exposed tofactorsin any of thefour stress-domains and had no autoimmune disease, no diabetes-related autoantibodies, no T1D in the family, and no current infection. Demographic (parent’s education, age and foreign origin, marital status and the child’s number of siblings and the child´s BMI) and diabetes-related(first-degree relatives with T1D and autoantibodies) variables were analysed in children exposed to psychological stressin thefamily and the control groups.

Paper

II

Paper

II

Forty-seven young women (18-22 years old) were included in Paper II from the Impact of stress project. Based on the distribution of stress-scales (Childhood Trauma Questionnaires, CTQ; Stressful Life Events Scalefrom the Alcohol Drug Diagnosis Instrument, ADDIS; and Perceived Stress Scale, PSS), the cut-off of above the 75thpercentiles were chosen to define three stress

groups exposed to three types of psychological stress, related to different lifespans (psychological stress from adverse maltreatment experienced before the age of 12, psychological stressful experiencedfromlife events throughout life and current experiences of psychological stress in the past month). A control group(18-22 years old) was created based on thefollowing criterion: all controls hadless than average(<40 %)on each and every one of these same