J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

M i c r o c r e d i t a n d F i r m Sta r t - u ps

a n d S u r v i v a l s i n D e v e l o p i n g

C o u n t r i e s

Paper within ECONOMICS

Author: Clara Karlsson 830610 Ida Henriksson 830407 Tutor: Åke E Andersson, Professor

Bachelor Thesis within Economics

Title Microcredit and Firm Start-ups and Survivals in Developing Countries Authors Ida Henriksson

Clara Karlsson

Tutors Åke E Andersson, Professor James Dzansi, PhD Candidate Date Fall 2008

Keywords Microcredit, Financial Institutions, Firm Start-up, Remittances, Infrastructure

JEL Classifications F16, F24, G21, I30, J01, J23, J43, O10

Abstract

Still in the twenty first century poverty is widespread and one is constantly reminded of it. The purpose of the thesis is to test if the economic growth in developing countries, measured by firm existence, is influenced by access to microcredit, remittances, corruption and infrastructure. The hypothesis is that if it is possible for individuals to start-up firms, they can take themselves out of poverty and we suggest that microcredit can play an important role.

The main findings of the estimations is that microcredit has a significant positive impact on the number of micro, small and medium size enterprises in low and low-middle income countries. Corruption has as expected a significant negative sign, thus a negative impact on the number of small and medium size enterprises. However remittances have a small negative impact that is significant which is not in line with the hypothesis. One reason for this might be that lower-middle-income countries are included and they are expected to have a more developed financial sector. One cannot conclude that infrastructure affects the number of firms since it is not significant.

The conclusion of the thesis is that microcredit could be a way for poor people to start their own business, thus enhance the economic growth in a country.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Purpose ... 2 1.2 Disposition ... 22

Background ... 2

2.1 Overview ... 22.1.1 Brief History of Microcredit ... 3

2.2 Firm start-up and survival ... 4

2.3 Labor Market Development ... 6

2.3.1 Arthur W. Lewis Theory of Economic Development ... 7

2.4 Credit Access for Poor in the Agricultural Sector ... 9

3

Theory ... 10

3.1 Microeconomic Theory of Firm start-up ... 10

3.1.1 Small New Firm (A) ... 10

3.1.2 Lending firms (B) ... 12

3.1.3 Information Flow (A.a & B.b) ... 12

3.1.4 Negotiation and the Contract (C) ... 14

3.1.5 Risk ... 14

3.2 Importance of local access to capital ... 16

3.2.1 A Swedish example ... 18

3.3 Microcredit ... 19

3.3.1 Microfinance Institutions ... 19

3.3.2 Group Lending ... 21

3.3.2.1 Critique of Group Lending ... 21

3.3.3 Problem and Critique of Microcredit ... 22

3.4 Remittances ... 22

3.5 Infrastructure ... 24

3.5.1 Development of Sweden’s infrastructure ... 25

4

Hypotheses ... 26

4.1 Previous Hypotheses and Their Testing ... 26

4.1.1 Microcredit ... 26

4.1.2 Remittances ... 27

4.2 A Revised Hypothesis ... 27

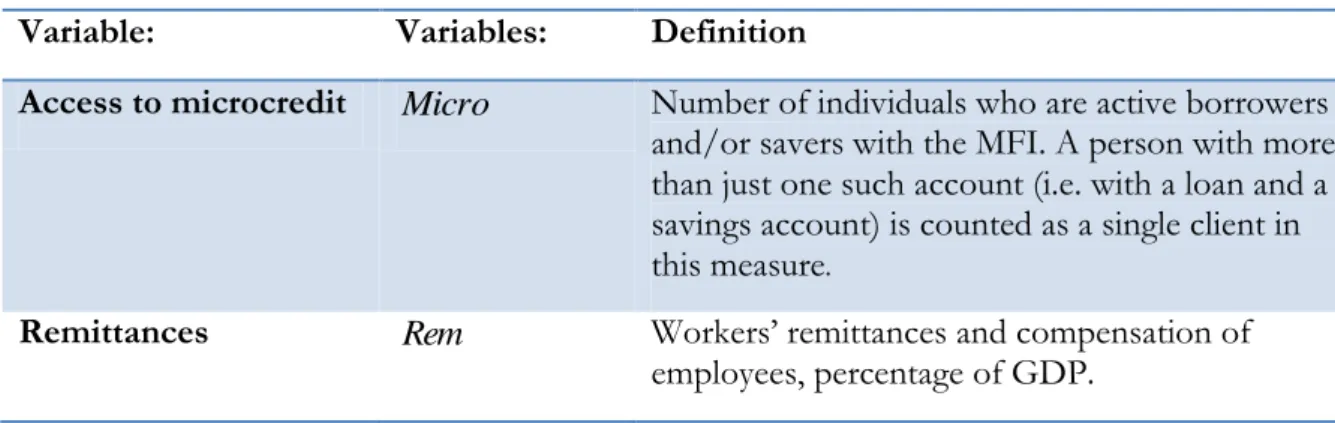

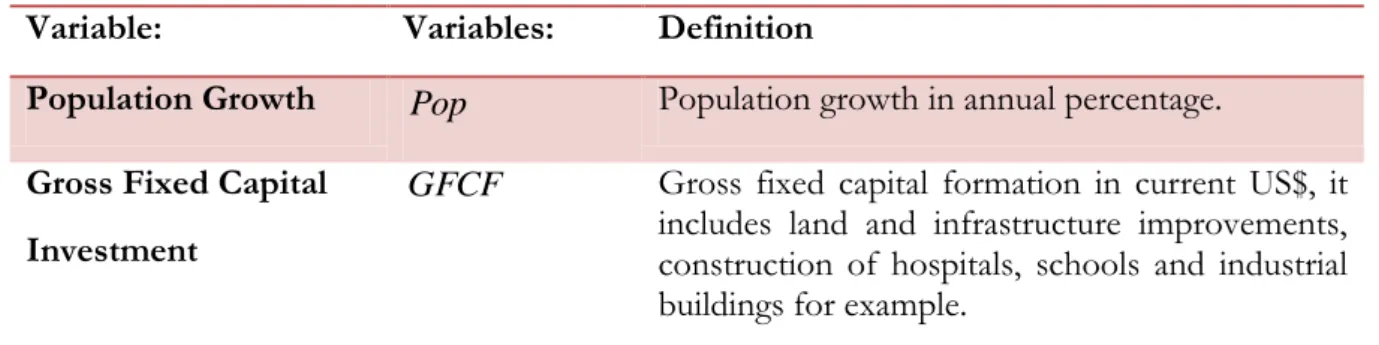

4.3 Data collection ... 29

5

Result and analysis ... 30

6

Conclusions and Suggestions for Further Studies ... 31

References ... 33

Appendix

Appendix 1 Poverty Trap

Appendix 2 Remittances Regression Results I Appendix 3 Remittances Regression Results II Appendix 4 List of Countries Used in the Regression

Equations

Equation 1 Labor Demand Equation 2 Cost Function

Equation 3 Average Cost Function Equation 4 Investment

Equation 5 Entrepreneurs income Equation 6 Entrepreneurs net- income Equation 7 Estimated Regression

Figures

Figure 2.1 Overview Figure 2.2 Firm Existence Figure 2.3 Peasant Economy

Figure 2.4 Marginal Productivity of Capital Figure 2.5 Quantity of Labor

Figure 3.1 Lender – Borrower Relationship Figure 3.2 Example of Cost Function Figure 3.3 Security Market Line

Figure 3.4 Planned Investment Spending

Tables

Table 4.1 Estimated Regression Variables Table 4.2 Regression Hypothesis

Table 4.3 Regression results for micro, small and medium enterprises Table 4.4 Regression results for new entries

Table 5.1 Regression Result for 38 low- and low-middle income countries, 1997-2005.

1

Introduction

It is not a secret that people all over the globe has different financial possibilities. Wealthy people are looked upon as stable and reliable hence they will have a greater access to the financial market than poor people, which are often left to fend for themselves. Being stuck in poverty becomes a negative circle – a poverty trap. The World Bank (2007) defines the extreme poor as people who live with $1,25 per day or less, calculated at the purchasing power parity (PPP). The number of people that live under extreme poverty decreased by 260 million during 1990 to 2004, mainly due to major poverty decline in China. However, the numbers of extreme poor in Africa has increased by almost 60 million during the same time (World Bank, 2007). According to UN data (2008) in 2005 over 50 percent of the Sub-Saharan population in Africa lived on less than 1$ per day. The suggestion of the thesis is that if credit to poor individuals is more available they are able to start their own firms and in a way help themselves out of poverty. They do not have any own money to start a business, and they do not have securities for a loan, thus they are not allowed to borrow any money at the commercial banks. Access to credit is an essential for firm start-ups and survivals. The thesis suggests that microcredit, together with other variables, could be a way out of poverty.

In 2005 it was the international year of microcredit in the UN which was a part of the Millennium Development Project for reducing poverty worldwide. This implies that there is a widespread view of the importance of microcredit as a tool for poverty alleviation. In developed countries one is constantly reminded through the media about developing countries and the situation for people who are poor. Aid has existed in different ways for a long time, yet Easterly (2006) argues that there is no evidence that aid to poor countries generates substantial economic growth effects. Africa for example, has a low growth rate despite the fact that large amounts of aid flows into the continent.

The starting point of the thesis is that microcredit and firm start-up by poor individuals can be a way to reduce poverty. The wide interest of well functioning microcredit in developing context can be explained by several reasons, such as it redistributes money to those who are poor as well as it promotes self-help. Banks that are specialized in microcredit often has higher repayment rates than commercial banks (Hulme & Mosley, 1998).

Development agencies can testify of empty buildings and unused wells because they were handed to people who do not have the incentives, capital or knowledge to use it. However if a person is allowed to borrow money and has to build up his own project it is more likely that he will actually do it.

For the possibility of economic growth there has to be a good economic environment, where new entrepreneurs dare to challenge the risk factors that are contained in the process to start and operate a firm. There are many different factors in an economy that influences firm start-up and survival and we have chosen to look deeper into some of them. The authors are aware of the fact that there are more variables that affect firm existence than the ones included. Microcredit is the first variable and in the theoretical part one can see that the correlation between local access to banks and availability of credit, play an important role for firm formation and survival. Other variables discussed in the theory section are remittances and infrastructure which also influence the economic environment of firm start-up and survival.

1.1 Purpose

The purpose of the thesis is to test if the economic growths in developing countries, measured by firm existence, are influenced by access to microcredit, remittances, corruption and infrastructure. The hypothesis is that if it is possible for individuals to start-up firms, they can take themselves out of poverty and the suggestion is that microcredit can play an important role.

1.2 Disposition

The disposition of the thesis is as follows. First there is a background which describes poverty, firm start-ups and survival and development. Then there is a theory section which deals with the process of firm start-ups and the variables that affect it. This is followed by section four where the variables are explained and section five where the variables are measured and analyzed. Finally there is a conclusion and suggestions for further studies.

2

Background

To understand the situation in developing countries this section describes poverty, microcredit, firm start-ups and survival in developing countries, economic theory of development and credit access for poor.

2.1 Overview

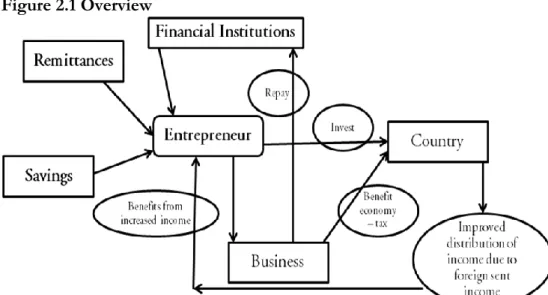

The relationship between different actors that are apart of firm start-ups in a developing economy is explained by Figure 2.1. The basis of the thesis is the individual or family who start a small business and who tries to make it profitable. To start a small business and to get it through the initial phase, one needs financial capital. In Figure 2.1 one can see that this capital can come from different sources; either from the individuals own savings or their relative’s savings, the capital can also come from family members that have migrated and who are sending home remittances or it can come from financial institutions in the form of microcredit. As the individual profit from his business he can consume more, thereby increasing the country’s GDP and tax revenues, which in the long run implies a better income distribution. A better situation in the country attracts more capital and financial institutions, which make banks more accessible and so forth.

Figure 2.1 Overview

Poor people’s lack of financial services is due to the fact that most of them live in a limited economic environment. They operate in small scale, when it comes to saving, borrowing, consumption, trade, production and exchange. Since they operate on a smaller scale, transaction costs can be very high and they are also exposed to risk and insecurity in various levels such as sickness, unemployment, theft, flooding and natural hazards. These and other risks leaves poor outside of formal institutions, thus it is difficult for them to start businesses. It also inclines them to spread their risk by working in networks, which microcredit can provide by group lending. Savings and credit is the insurance they rely on in case something happens. The poorer a household is, the more necessary credit and savings is, as a substitute for insurance (Matin, Hulme & Rutherford, 2002).

Savings is an important part of an individual’s life-cycle, both for consumption now, consumption later, unexpected fluctuations in income and to be able to invest in opportunities that may arise. To accumulate the cash needed for these different circumstances poor people often use one of three methods. They can sell their assets, pawn their assets or try to save small amounts until it becomes a lager sum. The problems that arise from selling assets for example are that many times poor people are forced to sell assets that would generate a larger income down the road. It can be crops that they sell in advance and then use the income to provide the crop that has already been sold. By pawning assets one has the opportunity to get them back again which distinguish that method from the previous one. However in both of these methods one is required to have assets first. If they instead choose to save small amount they can do that either by savings deposits, loans or insurances. Savings is consumption in the future, loans are consumption now traded for saving later and insurance is savings made constantly which allows for some kind of security in the case of an emergency (Matin et al., 2002).

A poor family can build up capital by saving their surplus capital, which in many cases is very small. They can either save it in a bank, who in turn lends it out to businesses, or they can invest it in, for example their own firm or assets bought in the market. If these savings go beyond the depreciation of the money/investment, the family has increased their capital stock. However, if the population grows faster than the capital stock, savings might not be enough to cover the increased population, thus the capital per person decreases. When the population increases faster than savings, the economy is caught in a downward circle, where lower income to the individual leads to smaller savings and tax revenues, which comes back to less public investment and savings. In Appendix 1 there is a model of the poverty trap relationship (Sachs, 2005).

2.1.1 Brief History of Microcredit

When banks lend money to people there is always some sort of collateral involved, this might be a house or some other valuable assets. It is to make sure that the bank has something that they can rely on in case the borrower cannot repay their loan (Armendáriz de Aghion & Morduch, 2005). For poor people, who cannot offer any security for their loans, there exist no regular bank credits, with a market interest rate, since the bank cannot afford to take on the higher risk of a non-collateral loan in the traditional sense. The bank or the financial institution adds to the interest rate an insurance premium, which pays for the costs if the project does not succeed (Hulme & Mosley, 1996).

The idea with microcredit for those who are poor; stems from credit market failures. Historically microcredit has been practiced over 150 years by individuals who have wanted to make credit available to poor people in urban and rural areas. During the 1970s and 1980s however it became a more popular method for development and programs like the

Grameen Bank, which started in the 1970s, are today famous microcredit institutions (Kessy, 2007). The Grameen Bank was started by an economics professor named Mohammed Yunus in Bangladesh. At the time there was starvation in the country, many moved to the cities and unemployment was high. That triggered Mohammed Yunus to put his teaching in to practice, he organized a lending firm that allowed poor people to borrow small amounts to be able to start their own businesses and break free from poverty (Yunus, 2007).

Since poor people usually do not have enough valuable assets to function as ordinary collateral; it is common for them to take loans in groups. If one individual in the group defaults, the others should help out with the repayment. Since there is a joint liability it makes it more important for each individual to do their best. In the Grameen bank for example, repayments are done in front of all of the others that are involved in microcredit in a particular village, which also implies that one’s reputation is at stake (Armendáriz de Aghion & Morduch, 2005). By getting a loan the possibility to start up a firm rise but it is a long way to success.

2.2 Firm start-up and survival

Baumol and Schilling (2008) states that market size and economic growth is positive related to firm start-ups, whereas industrial changes and uncertainty reduces the possibility of it. If there is a small amount of firms in an industry, it might indicate that there is no opportunity worth chasing, but on the other hand; if there are too many firms, competition might be too hard and result in a barrier to entry. Moreover, capital intensity increases entry cost for new firms, which also decreases firm start-ups. Institutional surroundings, such as access to capital and low start-up costs affect firm start-ups positively (Baumol & Schilling 2008).

Someone who starts a firm bears the risk and operates it, is an entrepreneur. In poor countries most entrepreneurs replicate other existing businesses, since this requires less capital and education than innovation does (Baumol & Schilling, 2008). In large parts of Africa agriculture counts for about half of the countries’ GDP, one can therefore assume that in many developing countries a small firm is an agricultural one. There are also many non-farm workers for example tailors, carpenters and so on. If people in rural villages increase their income they are also likely to increase the income of their neighbors by using their services (Mellor, 2008).

It is not easy for a country to encourage firm formation to stimulate economic growth. There are many factors that need to be taken into account and to make a location attractive for new firms. Baumol and Schilling (2008) argues that differences among individuals play a large role in firm formation possibilities, for example; it is more likely that an individual becomes an entrepreneur if he has a higher education, than the average population. In poor countries education is limited and entrepreneurship is more likely to be driven by social status and experience in the field (Baumol & Schilling, 2008). In Tanzania about 75 percent of the 11 percent that finished primary school are entrepreneurs (Kinda & Loening, 2008). In Sub-Saharan Africa the primary education completion level overall was 58 percent in 2005. In low-income countries the same level was 74 percent which can be compared to high income countries where the completion level was 97 percent (World Bank, 2007). It is easier to start a business in high income countries compared to Sub-Saharan Africa due to among other things corruption. Ease of doing business is tested by the amount of days necessary to legally start a new business. In Sub-Saharan Africa the average of days

necessary 2005 was 62, in the Scandinavian countries, at the same time, this average was under 10 days (World Bank, 2008). Corruption is when power is misused through bribes for personal gain and it affects a country negatively political, economical, environmental and social. Scandinavian countries are ranked as least corrupt while countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are ranked as most corrupt (Transparency International, 2009).

As stated above, it is hard to start up a firm and to keep it running, many factors take part in the structure of it, and a number of things can go wrong before the firm is stable. Figure 2.2 shows the relative frequency of firms in an economy and as can be seen, the smaller the size of the business, the higher the frequency of firms. In Tanzania this relationship is shown in a research done by Kinda and Loening (2008). They claim that one person enterprises are the most common enterprise size, this business form has about 56 percent of the whole business market, while five or more person enterprises have a share of about five percent.

Figure 2.2 Firm Existence

Source: Made by authors, based on discussions with Åke E Andersson (2008-10-17)

Therefore small firms, with only one or two employees, play an important part in the economic growth of a country. However financial constraint is the main restriction for entrepreneurs in developing countries since they and their relatives often lack private savings (Paulson & Townsend, 2001). A large part of the income is spent on basic needs, not very much is left to save; consequently the more important it becomes to save efficiently. Robinson (2001) tells the story about carpenters in Bolivia and Indonesia, who save their excess money in wood, not in banks. They buy the wood when the prices are low and store it in their homes, which at times become very crowded. Filling the room with wood is how these carpenters chose to save their extra money. This example shows that there is a need for better and broader information on how they can save.

Liedholm (2002) has found in his research of countries in Africa and Latin America that a large number of new micro and small enterprises (MSEs) start every year, on average over 20 percent. Most of them consist of a single owner/worker. Firms that generate a low return are often started in areas where the economic activity is low. The high rates of MSEs imply that there is not a lack of individuals in developing countries who wish to bear the risk of starting a firm (Liedholm 2002). MSEs or micro businesses are defined by OECD (1996) as a business that has less than 10 employees, is family based and does not require a large quantity of capital. In Africa, MSEs are in large owned by women. They operate from home, which implies that rent for their business location is the same as their living

expenses. It is most common with single-worker enterprises, although these kinds of firms are the least efficient ones (Liedholm, 2002).

In Zimbabwe there is an annual birth-rate of firms of around 17 percent which can be compared to birth-rates in industrialized countries which are around 10 percent. However high closure rates of firms are also common and in Zimbabwe around 10 percent of firms close down. Half of the firms that close down in rural areas do it within three years. However, firms that actually grow are mostly firms that started out as microenterprises and have at most five employees (Liedholm, McPherson & Chuta, 1994). According to Liedholm and Mead (1999) around 10 percent of micro firms in developing countries close every year. Location seems to matter since firms in rural areas have a somewhat higher mortality rate than firms in urban areas. The importance of small firms, with 50 or less employees, for job creation and income to households has increased. In rural areas they consist of up to 45 percent of employment and 50 percent of income to households. Firm start-ups explain the majority of job creation in rural Africa.

According to economic theory, different factors can be considered when it comes to firm growth examples are; age and initial size of the firm. Other factors are in which sector the firm exists and location, firms that are grouped together can benefit from positive spillovers from other firms and access to a larger market. Human capital is also used in economic theory as an important factor for firm growth. Finally the countries culture, political climate and economic situation are also factors that matters for firm growth (Liedholm, 2002). The research done by Fox and Oviedo (2008) states that the employment growth for micro firms with 1-5 employees is 28 percent, however the employment level for medium-large sized firms with 50-100 employees, has instead decreased by 0,2 percent. In Sub-Saharan Africa employment is overall increasing by 16, 6 percent, which can be explained by the large population increase in earlier years.

2.3 Labor Market Development

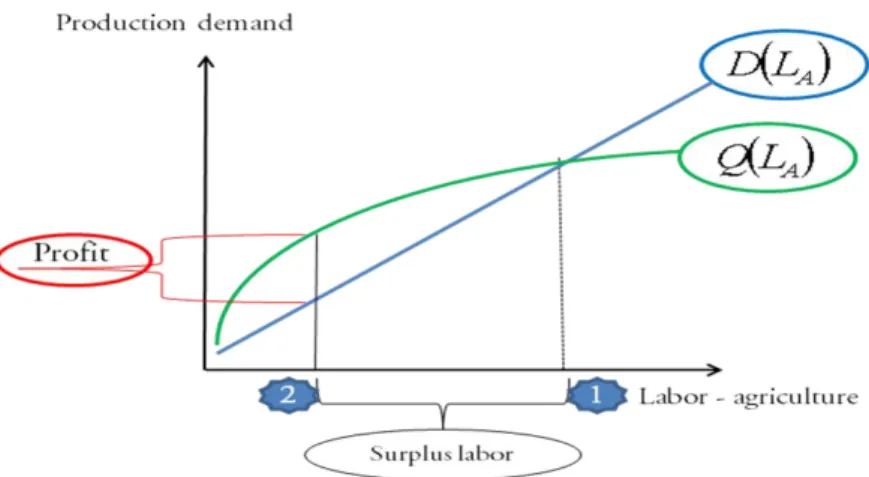

Labor markets in developing countries origins from the peasant economy, which is illustrated in figure 2.3. Point 1 in Figure 2.3 shows the stagnant agricultural economy with peasant equilibrium, where the demand for labor in agriculture equals the quantity of agriculture laborQ

LA .Figure 2.3 Peasant Economy

In the peasant economy it is the same output each year; there is a subsistence economy since people only receive just what they need every year:

LA wagesub LAD ( )* ; (1)

In equation 1, D

LA is the demand for labor in the agricultural sector and L( A) is theamount of labor. As long as the economy is in the stage where population increase, more people has to share the subsistence wage, which leads to even deeper poverty and declining health condition. When the economy starts to move out of the peasant stage, towards a capital economy it reaches for profit maximization. The capitalist equilibrium is at point 2 in Figure 3 where the demand exceeds the output produced in the agriculture sector and wages are higher. When the economy starts to produce more efficiently, the agriculture sector will not need as much labor as before, and there will be surplus labor, which is indicated in Figure 3 and a possible profit when the quantity exceeds the demand for labor:

LAQ <D

LA (Andersson & Holmberg, 1977).2.3.1 Arthur W. Lewis Theory of Economic Development

Arthur W. Lewis has constructed a classical theory of development; the Lewis two-sector model, which deals with poor individuals as surplus labor, which was contrary to the ruling theories at the time of his publication (Lewis, 1955). The model consists of two sectors; the agricultural sector and the industrial sector, which characterize a developing economy. Modern agriculture, which can be technology-intensive, is included in the industrial sector. The agricultural or traditional sector explains the rural areas that are overpopulated with zero marginal productivity of labor. Because of this, there will be no loss in output, if labor is moved out of the sector; the unlimited supply is a reserve of cheap labor for industries with high productivity, since marginal productivity is higher than zero. The labor supply comes from population increase that appears in the demographic cycle. This relationship is explained in Figure 2.3 at point 2, where one uses lower quantity of labor for profit maximization (Todaro & Smith, 2006). However Lewis (1954) does not claim that surplus labor can be applied everywhere, and for example many western countries are exemptions from surplus labor. It exists where natural resources and capital is small relative to the population. In large parts of the economy’s sectors marginal productivity of labor is around zero. In these sectors, for example agriculture, petty trade or domestic services workers only receive a subsistence wage. There is also the case of over-population, when there are more births than deaths. Therefore, as long as the supply of labor is larger than the demand at the subsistence level, there is surplus labor. This implies that new firms can start and old firms can expand without lack of labor (Lewis, 1954).

Lewis’ theory argues that the surplus in labor in the low-productivity sector gradually goes into the industrial, modern sector in urban areas, where there is high productivity. The industrial sector expands as a function of investments and capital accumulation, with the underlying assumption that capitalists reinvest profits. Figure 2.4 shows the trade-off between the two sectors and total amount of capital that is available for them. To reach the desired distribution level, capital moves from the agricultural sector to the industrial sector. The model assumes that wages in the modern sector are constant and higher than in the traditional sector (Todaro & Smith, 2006).

Figure 2.4 Marginal Productivity of Capital

Source: Made by authors, based on discussions with Åke E Andersson (2008-10-17)

According to Lewis, growth requires people to move to new locations and to change occupation as new resources or new ways to use resources are discovered. Since individuals are commonly unwilling to leave their homes something will happen to induce the relocation, this could be famine or over-population which occurs in poor areas (Lewis, 1955).

There are three differences between the agricultural sector and the industrial sector which are technology, organization and behavior. The differences in technology are in the industrial sector where the capital that is used can be re-used and the goods produced can be either consumed or invested. While in the agricultural sector land is used in the production and one can only consume the goods that come out of the sector. The second difference is organizational, where the industrial sector operates in urban areas and is market-oriented whereas the agricultural sector operates in rural areas and production is at a level of subsistence. At this subsistence wage level, Lewis (1954) claims that the supply of labor is unlimited and workers receive a salary that is higher than their marginal productivity, higher than they would have received without a subsistence wage level. In Figure 2.5 one can see the subsistence wage level as W and beyond point M the workers wage level exceeds their marginal productivity.

Figure 2.5 Quantity of Labor

Source: Source made by authors, based on Lewis, 1954, p. 146

As labor migrate from the rural areas to the urban areas, the industrial sector increase. The third difference that Lewis (1954) points out is behavioral. In the industrial sector there are capitalist who save their profits (WNP in Figure 5), however the workers in either sector can never save their money since they are poor. The conclusion is that savings in the

industrial sector, made by capitalists, are used to employ an increasing amount of farm workers. The profits in the industrial sector, which can be seen in Figure 5 and 6, can be used in different ways. As described above, Lewis explains that the profits are saved and used to increase the industrial sector. Profits can be used for consumption, for capital building locally or for capital building in other regions (Vines & Zeitlin, 2008). In order for capitalists to benefit from the profit to start new firms, they need to have access to local banks.

2.4 Credit Access for Poor in the Agricultural Sector

Many poor people in Africa work in the agricultural sector, which is volatile when it comes to investment. To increase technology and firms in this sector is crucial for economic development; however the lack of capital makes this hard. Lack of technology would lead to constant future output, instead of the possibility of an increasing future output (Carter, 2008).

The prospect for a small farmer to make a secure loan is considered low. Carter (2008) advocates that in developing countries of Africa, Latin America and Asia, only 5-15% of the small farming owners have formal financial contracts, while others are borrowing at a nominal interest rate, which has a higher rate, than the formal interest rate charged by formal financial institutions such as state agricultural banks. There is an excess of demand for credit and due to the low formal interest rate, which is relatively hard to raise, the supply will not increase. The low formal interest rate is held low, because if the formal institutions would increase the interest rate and clear the market, the small farming households are not any longer the optimal borrowers, since they are not believed to be able to pay back the loan to the lenders due to higher cost. Carter (2008) concludes that this results in a biased agricultural credit market where the agricultural entrepreneurs are the losers.

In the agricultural sector there is a time lag for the lender and borrower to consider since it takes time from when one plants the crops until there is actual output from it. There is also a great deal of uncertainty due to nature and volatile prices. Rural entrepreneurs are constrained due to a lack of financial institutions since that implies a reduced ability to make investments and take on and diversify risks. Contracts are written at a point in time when the outcome is not yet clear and they are later executed once the harvest has taken place. In an agricultural society it is necessary to be a part of contracts that reduce the risk of being left with nothing in case there is a drought for example. To engage in these types of contracts it is not enough to team up with ones neighbors since they will most likely be affected in the same way by the lack of water. Instead there is a demand for financial intermediaries that can take on some of the risk (Conning & Udry, 2005). However, even if there is a demand there is not necessarily a supply for the rural markets.

Another implication with skewed credit supply is that small agricultural business are not likely to be able to stay on a constant credit level; instead landowners might merge into larger businesses where the possibility of receiving higher credit increases (Carter 2008). Eswaran and Kotwal (1986) show this outcome; a framework that is made to show the structure of the different agricultural classes. Hence, the more land a farmer owns, the more security he can leave to a lender, and thus the more capital he can borrow. The effect of this they claim, makes the agricultural sector less efficient, with lower output, and with a more unequal distribution of the produced output. Carter (2008) shows that when an economy starts off with this kind of biased wealth distribution they will most likely stay with it. Carter (2008) together with other modern works also show that Eswaran and

Kotwal (1996) model is correct in the sense that the higher-income producer becomes wealthier while the low-income producer stays rather poor and become held up in a poverty trap.

3

Theory

This section describes what theories the thesis is based on and also which variables are used in the regression model.

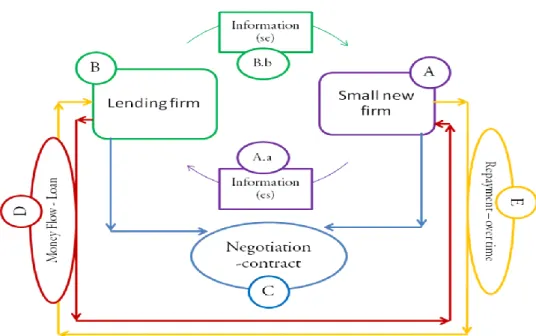

3.1 Microeconomic Theory of Firm start-up

When a poor individual wants to start up a new firm it needs to consider its options and possibilities. Figure 3.1, shows a microcredit model that describes the relationship between a small new firm (A) and a lending firm (B). The small new firm needs to give some information (A.a) to the lending firm, for example to show its assets, its structure, prospect revenue and future plans. Also the small new firm needs information (B.b) from the lending firm, for example about its location and requirements. There will be an interchange of information between the two parts, which can go back and forth until they agree upon a solution – a negotiation and contract (C). When the two parts interact there will be a money flow (D) out from the lending firm to the small firm, and some type of repayment (E) from the small firm to the lending firm. For the reader to more easily follow the structure of section 3.1, the different letters are stated in all of the subsections, related back to Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Lender-Borrower Relationship

Source: Made by authors, based on discussion with Åke E. Andersson (2008-09-26)

3.1.1 Small New Firm (A)

A large fraction of small firms are family oriented, those who are employed are members of the family or relatives. The basis of the firm is often a skill that a family member has, for example the ability to cut hair or to drive a taxi. To start up a business the family or the individual need to take into account the cost of the firm. The new firm needs to determine q – the quantity they should produce to be able to cover their costs. They need calculations on how much people would be willing to pay for the good/service they offer and how

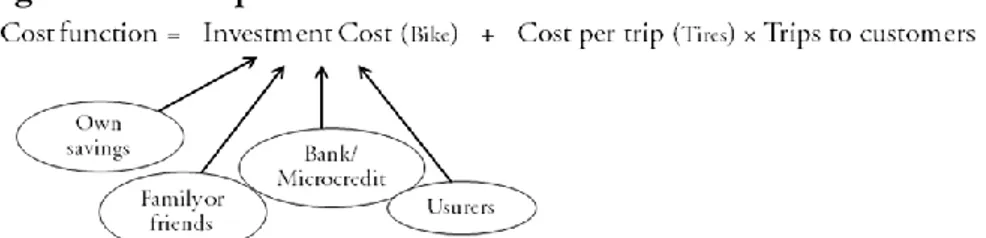

many they can serve. This in turn depends on the price they set and the economic activity around them. In developed countries this can be done by, for example send out a market research, look at statistics or study other firms’ annual financial statements. However in developing countries data is not as easily accessed both due to lack of information from other firms and due to the lack of possibilities to research the market (Cooper, 1981). A basic cost function is shown in equation 2, which shows the fixed and the variable cost that a firm faces. A fixed cost (F) is the investment needed to cover the permanent costs of production (could be a bike if you run a bike-taxi service or a laundry machine if you run a laundry). However, in the long-run even fixed costs vary, thus the firm need to focus on a short-run basis. Variable cost (v) is the sum of all payments needed to cover the firm’s variable factors of production, which is the inputs needed in the production that varies in the short-run (McDowell, Thom, Frank & Bernanke, 2006), like tires for the bike or laundry powder. The q is the quantity produced, the firm’s output, and it is an uncertainty in income.

Cost =Fvq; (2)

An average cost function that the firm faces is shown in equation 3, which shows that the more output the firm produces; the fixed cost becomes less significant (McDowell et al., 2006).

Average Cost =F/qv; (3)

The problems for an individual who wants to start a business are mainly: capital, lack of materials and markets. The main problem with all three of these areas is access. Capital is the most critical need in the start-up, since many small new enterprises lack that, especially for the fixed cost, which is a large share of the budget in the beginning. Location of the firm plays a part in the amount of capital needed, in rural areas activities are often less capital intensive than in urban areas (Liedholm & Mead, 1999).

At the beginning when a small firm faces a cost function, there are different options on how to finance the start-up. The crucial thing for a new firm is to find capital to base its business and to cover the fixed cost needed to the start-up. Figure 3.2 shows the relationship of how to solve the initial need for capital by taking an example with a taxi bike. Capital for the fixed cost to the start-up can be drawn from the individuals own savings, family members’ and friends’ savings, from banks or usurers. However, as Sachs (2005) points out; in developing countries, poor people and their relatives have a lack of individual savings. Banks or usurers are the only option to access capital which makes them important characters in the small firm’s construction.

Figure 3.2 Example of Cost Function

3.1.2 Lending firms (B)

The interaction between a commercial bank and its customer is smooth as long as the customers possess all the required securities needed for a lending contract. However, as soon as the customer does not have that, the bank is out of formal options and the customer is no longer a possible client. Morduch (2008) argues that poverty reinforces poverty, in the sense that the median bank, who are lending to poor people, has less loan balance, than a bank that lend to wealthier people. Morduch (2008) draws the conclusion that poor people lose twice; they start off with less capital, since their income is lower, and as a consequence of this, they have a lower access to the credit market, which could enable them to start up a small firm and offer a way out of their poverty.

A goal of a lending firm can be to lend capital by microcredit to small scale firms. The lending firm can have as a goal, to provide capital to small-scale firms, which in turn can provide jobs for the public and create potential economic growth, or to offer income-openings and services to decrease poverty. Another objective that a lending firm can have is to promote and help small firms run by entrepreneurs who would normally not have access to the financial market due to lack of collateral or that they are included in a disadvantage groups, like many women (OECD, 1996).

Since lending is a business, the bank needs to choose borrowers that succeed with their business. An individual needs to be an entrepreneur with a successful plan, and the problem for the bank is to know which one of these entrepreneurs to select. There are various programs and techniques to follow for the bank, and rules that have to be set and taken into account before starting to lend (OECD, 1996). The bank has a problem of adverse selection which is due to the asymmetric information that the bank has regarding which borrowers are ―bad‖ and which are ―good‖. Since banks do not have the information on this they are tempted to charge a higher interest rate to everyone to cover the risk of lending to hazardous customers (Armendáriz de Aghion & Morduch, 2005). Berger and Udell (2002) categorize a bank’s lending tools into four different starting positions; financial statement lending, credit scoring, asset-based lending and relationship lending (first three are usually called transaction-based lending). Whatever base a bank has, it needs to know two basic things; its client’s plans for the future – possible return, and to what cost it can provide credit to its client. This cost is based on how risky the client seems to be, and the lending firm has to take into account its own possibility to afford a risky client. Since the expected return is of no guarantee, the bank has to charge its client for unexpected losses – it has to have a risk compensation included in its price for the small firm (Berger & Udell, 2002).

OECD (1996) claims that the most successful microfinance programs charge market interest rate on loans, and not subsidized like governments usually do. A high interest on a small loan is more profitable for the lending firm and since the demand for credit is high, individuals and small firms are prepared to pay a high price for the loan since the other option is no credit at all. A bank has to take into consideration what type of information they need, to agree on a loan and from there they arrange their own structure.

3.1.3 Information Flow (A.a & B.b)

Entrepreneurs are ready to invest in projects that might be profitable; however information is important when it comes to lending. Even though investors receive some information about a future project, a minor lack of information can be devastating for the final close-up between the lender and the borrower. Berger and Udell (2002) points out the importance

of this information link, and claims that small firms are more vulnerable because they do not have the same access to the capital market as larger firms do. The difference from larger firms is that the small firms are more dependent on external financial support from financial institutions, which also make small businesses riskier than larger ones.

Berger and Udell (2002) discuss the possibility of reducing the information problem between the lender and the borrower with constant contact. They argue that banks, through some type of contract, will keep up the information with the borrower over time and thus create a smooth relationship between them. This contact between the bank and the borrower is generally known, however not often discussed. Berger and Udell (2002) call this bank-borrower technology relationship lending. It is different from a regular collateral based loan due to its contact structure. A regular loan might be from a bank that offers capital, to a firm that has some assets to use as security and both parties agree on a contract. They exchange hard data, such as information about the firm’s value, based on the firm’s balance sheet, and its income report. The bank need to offer a view on the contract requirements – all this hard data is easy for large, established firms to show and find. However, Berger and Udell (2002) argue that there are different needs of information when it comes to riskier contracts. A small firm with little assets might not be able to hand in any documents (hard data) and they might not have any assets to put in as collateral. This stage of a firm puts more pressure on the bank to be able to meet the needs of a new type of agreement.

Relationship lending requires contact over a period of time, since both parties are building up a contract from soft data, also called tacit knowledge; this can be costly for the bank but valuable in the end. The information gathered over time, such as a long history of the business and the environment of where the firm operates – the neighboring society, is highly creditworthy. When it comes to the issue of borrowing capital, Berger and Udell (2002) claims that at times soft data is more powerful than collateral and financial statements. A strong relationship between a firm and a bank, for example a strong mutual trust between the company and the bank, can affect the price of the loan and also the supply of credit in the small firms’ market. The bank can also gain, due to a lower information cost, since a strong relationship means efficient interchange of information. This is the type of lending that microcredit deals with.

Backman (2008) in the lines with Berger and Udell (2002) argues, that distance between the borrower and the lender matters. Information is costly, since it involves trust and continuous meetings, thus for the borrower to decrease these costs, he could locate close to the credit lender. For the bank, to decrease information cost, it could locate close to the small firm.

Firms have economic links to various actors in the market; these links might be technologic, cooperation and contacts with costumers. Every economic actor has to communicate with its surroundings in different ways, to create links. These links represent information flows and interaction between economic organizations. To create a link the interactions needs to be permanent and once a link is established the transaction costs for the two economic actors are reduced (Johansson & Westin, 1994). This theory is applicable on the interaction between the small firm and a bank. Once they have negotiated the contract there is a link established between them.

3.1.4 Negotiation and the Contract (C)

When an individual takes a loan, he or she substitutes future consumption for consumption today. By the same logic the financial institution or the lender substitutes money today and instead they will receive money in the future, which gives them incentives to make sure that the money is in fact repaid (Hoff & Stiglitz, 1990).

There is an obvious principal-agent problem in the negotiation of a contract between borrowers and lenders. The principal is the poor individual in need of capital to start his or her firm. The agent is the bank or financial institution that the principal turns to, which has an agency problem of not knowing which borrowers who are going to succeed and those who are not. The problems are more specific; the bank does not know what amount is right to lend and if the borrower is trustworthy, since it is not possible or too costly to totally screen all costumers. When the loan is received the agent does not know how the principal will use the capital, if the capital gives the principal incentive to work harder or if it has the opposite effect. At repayment day, the principal can falsely claim that profits were not as high as anticipated. It might also be difficult for the bank to enforce the borrower to fulfill the contract (Armendáriz de Aghion & Morduch, 2005). In summary these problems involve adverse selection, moral hazard, auditing costs and enforcement (Ghatak & Guinnane, 1999).

The problems described above can be solved indirectly, by detailed contracts or directly, by personal contact. In the credit market contracts regulates the amount borrowed and the interest rate, at which the capital is to be repaid. The incentive for the borrower to honor the contract is that it ensures them access to future capital. The direct actions that can be taken are more costly, at least for banks, since it requires personal contact (Hoff & Stiglitz, 1990).

Today the effects of globalization affects everyone, even poor people are a part of large markets. However, even if they can participate and provide services to global markets, they are in general outside the market when it comes to risk spreading, investments and risk-taking. Poor people do not have any back-up and is therefore at high risk, if there is a negative income shock for example. This in turn implies that they might be forced to choose activities that provide a lower return, not using their resources efficiently. In poor areas, financial institutions often have a small amount of activity. According to Dercon (2004) there are three reasons for this, the first one is that governments are, to a large extent involved in banking systems, thus creating regulations which in a way hinders financial institutions. The second reason is that poor areas have low income and is therefore risky to invest in them. The third reason is that the population is spread in developing countries, however this reason does not hold in Africa for example, where microcredit has expanded even in low-density areas. It needs to exist some kind of intermediary in order for financial contracts to take place. There are several kinds of financial intermediaries like banks, pawnshops, savings institutions, insurance companies and safety nets etc. In many developing countries, the lack of access to these kinds of institutions is due to government legislation (Dercon 2004).

3.1.5 Risk

Firms face diminishing returns to capital, if labor is held constant, the more input of capital the less each extra unit of capital input contributes to production (McDowell at al., 2006). This implies that the investments a firm with small capital makes, has the possibility to receive higher returns than the once larger firms makes. As a result firms with low capital

should therefore be prepared to pay interest rates that are higher than relatively richer firms. Conning and Udry (2005) show that, small rural enterprises have a higher marginal rate of return on capital than larger firms. In Ghana for example these numbers are as high as 50 percent for MSEs, while large firms has a marginal rate of return of only 10 percent (Conning and Udry, 2005). If the theory of diminishing returns to capital is applied on world economics then capital investments should be made where there is a higher marginal return to capital for example in developing countries. Therefore capital in general should flow from rich people to poor people. However there is one factor that is not incorporated into the return of the MSEs and that is risk (Armendáriz de Aghion & Morduch, 2005). The expected return on different levels of risks is shown in Figure 3.3. The security market line (red in Figure 3.3) is a balance where all the assets in the market have the same reward-to-risk ratio (Ross, Westerfield and Jordan, 2003). One can see that small businesses, that are candidates for microcredit, are viewed as riskier, thus further away from origin. Banks and other financial institutions want to secure themselves against the risk of lending money to new small firms and therefore they have risk premiums (Grundy, 2002). Innovative projects are often viewed as very risky and in small developing areas it is hard to get credit for this type of projects. However, since financial institutions have the capability to hold diversified collections of many projects with different level of risk, they can accept risky projects that promote innovation (Backman, 2008).

Figure 3.3 Security Market Line

Source: Made by authors, based on Ross et al. 2003

Information about risk is crucial in the real market and to get away from taking on too much risk, banks can lend money to many firms with different risks by diversification. As a conclusion lending firms tend to charge small firms at the average risk cost compensating instead by having a large number of small firms, who would decrease optimal small firm portfolio risk (Ross et al. 2003).

In small firms credit is often constrained and the risks that face a small firm given an interest rate change or other external change is larger than the one larger firms face. Therefore it might be preferable for a small firm to engage in loans with a fixed rate. High interest rate leads to a decrease in investment as seen in Figure 3.4; this is most applicable to small firms which are constrained to receive financing from banks or other financial institutions (Vickery, 2005).

Figure 3.4 Planned Investment Spending

Source: Made by authors, based on Dornbusch et al. (2004) & discussion with Åke E. Andersson 2008-11-25

The relation between interest rates and investment is shown in Figure 3.4 and can be described by Equation 4. We now assume that investment (I0) is determined as the

marginal capital value of a future stream of profits (V0).

rT

rT t T e r V dt e V I 0 1 0 0 = r V I 0 0 ; (4)The integral in Equation 4 shows a time interval for the investment (I) from 0 to its time of death at time T. Vtis equal to expected profit, e represents the base of a logarithm and it is raised to interest rate times death time (of the investment). At year 0 the end the value of I equals, profits (V0) divided by the real interest rate, r. In Figure 3.4 one can see this

relationship that profitability increaseI

I I'

as interest rate decrease

r r'

r

(Dornbusch, Fischer & Startz, 2004). If the interest rate can be pushed downwards, for example by microcredit, it is possible for individuals to make larger investments

Poor people have to spend the largest fraction of their income on consumption, which leaves a very small fraction to deal with risks like income shocks. When poor people engage in lending contracts there has to be both some kind of insurance and credit involved. There is a repeated action involved in microcredit; those who can handle a smaller loan will have the opportunity to engage in a larger one, and so on building a stable credit record. In this way the poor can build up their reputation, which gives them less incentive to moral hazard behavior or other deceitful actions (Dercon, 2004).

3.2 Importance of local access to capital

An implication for the creation of small enterprises is the availability of capital; microcredit is built up on the importance of access to local credit.

Evans and Jovanovic (1989) assume that individuals can borrow in relation to their wealth, which is a constraint for the borrower, especially one with low wealth. This put emphasis on the importance of a capital base accumulated from savings, family members or access to bank loans to be able to start a new firm and make it survive in the beginning. The conclusion is that the more capital constrained an entrepreneur is the less likely he is to

start a new firm (Evans & Jovanovic, 1989). Local access to capital is important in an economy, especially in a developing economy where the infrastructure and communication is limited. An individual who wants to start a firm needs capital, and to attain it a founder faces a cost. In developing countries the founder most likely starts off without own capital, such as savings, so the importance of a financial institution is essential. Furthermore, to keep the business going a financial institution is of value for the firm, to be able to do repayments, invest its excess capital and to borrow again if necessary. According to Backman (2008) there is a positive relationship between new firm start-ups and access to financial institutions. Backman (2008) discusses the fact that the face-to-face interactions; to build up a relationship between the borrower and the lender, is expensive for the founder of a firm, and the distance to the location of the financial institution is crucial. A close relationship between the borrower and the lender is important in a future contract and with a shorter distance between the two, the easier the relationship will function. Therefore, the closer a financial institution is located to a potential firm, the easier it will be for the founder to attain credit, and thus it will be easier to start a new firm.

Local moneylenders and usurers exist due to the lack of formal financial institutions. They have advantage over distant financial institutions, of knowing their customers and their cost of retrieving information about borrowers are lower than for distant banks. This has made them the most important source of capital in developing countries; however their access to capital is also limited since they operate locally. A mixture of regular bank’s capital provision and the moneylender’s information would be preferable (Varghese, 2005).

Theoretically, financial capital is mobile; it is moved to the location that offers the highest return. If a new project has a positive expected return, Backman (2008) argues that there will be available capital. However she claims that the view on the capital mobility is diverse; it can either be seen as that the capital moves to where the firms need it, or the firms start up or move to the location where the capital is offered. Either or, the local businesses that have good access to financial institutions are privileged, compared to regions where capital access is limited. As a result, Backman (2008) concludes that the probability that a borrower will obtain a loan, decreases with the distance to a lender. The closer a lender is to his borrower, the more he knows about the local market in which the borrower operates, hence the easier the access to credit is. It is crucial for an economy’s long-term development to create good firm-environment where there is easy access to financial credit. The first thing an individual has to decide is whether to be employed by someone else or to start his own business. That is a question of opportunity cost, the work situation that yields the highest payoff will be chosen (Evans & Jovanovich, 1989). The income y, an individual can earn if he decides to start his own business is explained in Equation 5. is equal to entrepreneurial ability, k is equal to capital invested in the new firm and is equal to return to the capital that is invested.

k

y ; (5)

If the entrepreneur’s income in Equation 6, exceeds the income from working as an employee with wage, then an individual will start a new firm. This can be shown in Equation 6 where the net income of the entrepreneur is

) (z k r

y ; (6)

r is equal to interest rate, z is equal the capital the entrepreneur starts with, thus z is smaller than k the entrepreneur has to borrow and repay, r(zk).

3.2.1 A Swedish example

About 200 years ago the situation in Sweden was the same as in many developing countries today; this example shows that it is not only the availability of banks that is important for poor individuals, but also their location. . The Swedish savings banks worked as a form of microcredit and made it possible for poor Swedes to borrow and save money.

The agrarian revolution in Sweden took place in the eighteenth and nineteenth century when tax laws for agriculture changed and made it possible for common farmers to own land, previously this it was reserved for the nobility. The new political change came along with new technology that increased the agricultural productivity and made it possible for the average farmer to achieve economic surplus. Magnusson (2000) argues that this increase was not only due to new technology, but it was also due to a growing population which increased the Swedish labor force. Another factor of production that grew substantially during this time was land; an increased amount of land was cultivated for new families to settle down on. However, growth of the population in Sweden increased the poverty for many of the already poor farmers, which made the gap between the land owners and the ones without wider (Magnusson, 2000). The situation in Sweden at this time is an example of the peasant economy, where labor was unlimited, which was described above.

Poverty became a big public problem in Sweden during the nineteenth century and a social campaign started, to ease the suffering for the poor people. The first Swedish savings bank ―Sparbank‖ started in 1820 and was a result of the public’s campaign. The banks were institutions with a purpose to support the society and to reduce the poverty problem. The banks offered local credit and a possibility to deposit whatever surplus the farmers made. The inspiration was taken from Scotland, and the new idea was that any person, noble or poor, could deposit its excess money, with no regulation of too small amounts. To emphasize that the bank were made for poor, the Sparbank regulated a maximum amount for deposits, to be able to target the lowest classes. However, when some of the Sparbanks showed a higher profit than others the development of the Sparbank changed direction and the regulated maximum amount was taken away 1892. The main focus of the bank moved from being a poverty solution organization to become a savings institution (Forssell, 1992), but the banks kept its lack of ownership, to state that no individual would by himself have a share of the profit of the banks (Affärsvärlden, 1992).

Politicians had a motto that those who where poor should have help to self-help to get out of their misery. The Sparbanks worked as cooperatives with social ground and since the government was very positive to these institutions they spread all over the country. The first one started in Gothenburg as early as 1820 and from there it rapidly diffused to other localities, about 100 years later there were 498 Sparbanks locally placed all over Sweden (Schröder, 1996). The success of some of the Sparbank offices was due to their location; in an export city, where the depositors were business men and craftsmen, who wanted to save their excess money. At the countryside, on the other hand, the banks had another purpose; to support farmer with credit. These offices became foremost agrarian banks and were located in the closeness of its clients with locally trusted employees. They gathered the local people’s savings, and in contrast to the business banks, they tried to place the savings at slow growing interest with minimized risk. The savings was usually invested in local agriculture and local real estate buildings (Forssell, 1992).

The structure of the early agrarian Sparbank was characterized by an unforced relationship between the saver and the bank, where the saver could lift out its saved money at any time.

This was possible, since the savers share of the bank’s capital was typically small. The savers saved their capital individually for themselves, and by doing that in the same local institution, a larger amount could be put together and be lent out for interest. Forssell (1992) argues that the early Sparbank was a foundation, not a business, in the sense that it did not want to make large profits, not to expand and it did not have any real competition. Instead the agrarian Sparbank focused on the united interest of its local savers, with a motto that stated that it gave the highest and took the lowest interest (Forssell, 1992). This Swedish example highlights the importance of microcredit – local access to banks for poor individuals. The Swedish Sparbanks made a difference for particularly the poor agricultural population. The farmers now had a chance to borrow the relatively small amounts needed to increase their own output and thus develop the rural areas. The links between the situation in Sweden at the time when the ―Sparbanks‖ started and developing countries today, is clear. Most developing countries today are, as previously discussed, agricultural economies as Sweden was at the time, and do need small, but still very important, investments in basic technology. The link between the local banks that grew in Sweden in this stage and microcredit for developing countries today are also quite clear. The local ―Sparbanks‖ in Sweden gave poor individuals opportunities to easily and locally save and borrow money, which empowered them and developed the rural areas. This example, put in today’s context, can be financial institutions that provide microcredit for poor individuals.

3.3 Microcredit

Local access to credit can be offered by microcredit, which can be available in different forms and have different purposes. However, the main purpose with microcredit is to reduce poverty by helping poor people to start up firms.

3.3.1 Microfinance Institutions

Microcredit or microfinance institutions (MFIs) are financial institutions that provide financial services, for example insurance, credit and saving accounts, in a small scale to people with low income. MFIs that provide this kind of service are banks or organizations that are mostly operated non-commercially (Byström, 2008). Today microcredit has become a popular subject when one discusses the situation of the world’s poorest. Professor Mohammad Yunus started his now famous Grameen Bank in 1983 and with that he re-launched the microcredit method of lending money to poor people instead of giving them aid. The idea with the loans is to help poor people start up new businesses or to be used for emergency needs (Morduch, 2008).

Investors to microfinance institutions could be divided into three sectors; public, institutional and individual investors. The public investors, which Reille, Forster and Surendra (2008) refer to as Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), are investing in microfinance because of their job, which is to support developing countries with their future economic growth. To do this, the DFIs encourage private investment in these countries and they played a major role in the buildup of today’s microfinance structures. The reason for their success is that they can take on higher risks than for example private investors. Nevertheless, public investors do not always support private investments in developing countries. Instead they sometimes compete against them, using lower interest rates and open guaranties, as a way to reach the poor areas. This can result in situations where private investment is crowded out by public ones, since governments can have pressure from external and internal political actors (Reille et al., 2008).

Institutional investors are for example insurance companies or international banks that for different reasons choose to invest in microfinance. One reason could be that their clients demand the possibility to put money in developing countries and therefore they feel the need to offer an option for microfinance to stay competitive in their market. An example of institutional investors is the international bank Citigroup who started a microfinance group in 2005, who has invested money in many projects around the world (Reille et al., 2008). Another example is Swedfund; a Swedish company that provides information and investment opportunities for developed businesses. Their goal is to help invest in new markets with growing profitability. They focus on small African, Latin American and East European enterprises and by investments in these countries investors help to sustain economic development (Swedfund, 2008).

Individual investors are not as recognized or common as the public or institutional investors; however, they play an important advertising role for microfinance. One example of an individual investor is the founder of eBay, Pierre Omidyar, who helped to start a microfinance foundation by investing US$100 million. Microcredit can thus be a way for institutions, public sectors and individuals to make socially conscious investments (Reille et al., 2008). There is a large demand for microfinance in the world, however in most parts of the world there is limited supply (Bossoutrot, 2005). Although, Reille et al. (2008) argue that the supply of microcredit has increased remarkably in the last years, mostly due to the entry of the individual investors, who are not only after profits but are also socially responsible.

The possibility for micro-entrepreneurs and low-income households to take advantage of business opportunities is not very high in today’s financial markets. The fact that they are considered ―non-bankable‖ by the majority of the financial sector decreases their chances to make a better living by borrowing money to start up a new project (Bossoutrot, 2005). During the last thirty years there has been an increasing spread of micro lending mainly, according to Bossoutrot (2005), due to two reasons; the experience that poor people can be reliable borrowers and that they can pay back their loans with high interest rates. Because of factor one, creditors can cover their costs and even gain some revenue. The micro lending institutions have different outcomes in different regions and to prove a positive impact on the country’s growth is hard.

According to Bossoutrot (2005) research shows that when a society has access to financial services, the opportunity of preventing people from falling into poverty becomes larger and it also helps people to come out from it. Financial services, he claims, thus increases the productivity and welfare of people in an economy. This can be interpreted by a simple look at the fast growing microfinance sector which became apparent again in the late 1970s, to fight poverty in developing countries. When it comes to aid or credit, Bossoutrot (2005) argues that microfinance best serves the poor people who are actually already working. He says that the society have to be able to first supply basic needs to their people, such as food, water, shelter, health and education, before the people are ready to totally gain from a credit program. However one can see a change in the microfinance structure and it is going toward an adaption to the different needs of the society. From just offering credit as a solution to poverty, there is now a broader financial sector that offers a variety of services, like insurance products, housing and savings.

Firms belong to informal or formal sectors and in developing countries the informal sector is usually large. Firms in the informal sector are those that are not officially registered and therefore they do not obey under the government’s regulations and taxes. Informal sectors arise in developing countries because governments do not have the capacity to enforce