Co-design Approach on a Matter of

Concern: Structural Racism

Karim Mortada Mohamed Mahmoud

[Interaction Design] [One-year master] [15 credits] [Spring. 2020]

1

ABSTRACT

-

Discrimination and marginalisation are still problems, both on a societal level as well as within the field of technological development. Discourses such as HCI and design often fail to deal with the dynamics of race, even when using participatory approach, co-design. This design study aims to tackle and explore the possibilities of co-design using dialogue on the matter of concern, structural racism. The study aims to answer the questions; what could be the role of co-design when facilitating a discussion about structural racism? And how can we use digital mediums to co-design and create dialogue? The theoretical framework of this study, stems from ‘design thing’, where extended knowledge is produced collectively based on subjects’ experiences and Latour’s view on ‘matters of concern’, which is understanding the political situation from a holistic standpoint. The methodology derives from Sanders and Stappers framework called ‘say-do-make’ including an online survey and three digital creative sessions with participants. The results of the study propose guidelines on how to create dialogue about structural racism through a co-design setting. As a result of the proposed guidelines, this study suggests that interdisciplinarity is fundamental in order to integrate the matter of concern into the co-design discourse.

2

CONTENTS

-

INTRODUCTION 3

RESEARCHQUESTIONSANDAIMS 4

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 5

1.CO-DESIGN 5

1.2 Co-design in the Digital Realm 6

1.3 Co-design and ‘Matters of Concern’ 7

2.STRUCTURALRACISM 7

3.INSPIRATIONALCASES 8

METHOD 10

1.SURVEY 10

2.CREATIVESESSIONS/WORKSHOPS 11

2.1 Preparation for Creative Session 11

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS 13

ACTIVITIES 14

1.SURVEY 14

2.CREATIVESESSION 15

2.1 The Creative Session Implementation 15

RESULT 18

1.CREATIVESESSIONONE 18

2.CREATIVESESSIONTWO 20

3.CREATIVESESSIONTHREE 22

DESIGN PROCESS SUMMARY 25

1.SURVEY 25 2.CREATIVESESSIONS 26 3.FINALRESULTS 29 DESIGN SOLUTION 30 GUIDELINES 30 DISCUSSION 33 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 34 REFERENCES 35

APPENDIX A: STRUCTURAL RACISM WORKSHOP GUIDELINES 38

APPENDIX B: STRUCTURAL RACISM WORKSHOP PRESENTATION 40

APPENDIX C: DESIGNER STATEMENT 42

3

INTRODUCTION

-

Modern society and technology are facing numerous problems in relation to inclusivity and representation (Dachs, 2018). The issues are complex due to their long history and roots, which are embedded within the hierarchical system of society. The accumulation of historically reinforced power structures, actions of domination and discriminatory behaviours deepen the complexity of those problems (Hinson et al., 2018). These types of structures have made societal problems, such as structural racism, hard to solve or to some extent, even discuss. Structural racism is a form of racism made visible through intentional or unintentional behaviours. It leads to inequalities, rooted within hierarchical system and can be found on historical, institutional, cultural, and even interpersonal levels. The inherent power dynamics makes its way into all fields of society and, nonetheless, technology. Technological change causes an increase of use and demand which make technology one of the most advanced field of modern times. However, ethics surrounding the field have not fully developed. An example is exclusion of people of colour, which shows in the result of products, such as ability for face detection or who the product is marketed to. Within design and Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), scholars have been taking steps to investigate the effect of discriminations providing practices and regulations to minimise racial outcomes. Davis and Waycott (2015) created a collaborative workshop to offer HCI researchers and designers a space to reflect on and discuss ethical encounters when addressing complex topics in research projects. Despite the effort, the fields often fail to address racial ideologies, outcomes and rarely deal with the issue -racism and its multiple levels. The disadvantages of not involving directly with non-trivial topics is that the technological fields might miss the possibilities -that can emerge- and the challenges -that might evolve- in the design process when addressing such topics. For instance, participatory design emerged when dealing with workers’ right to democratise workplaces. Addressing sensitive topic might help to create a better humane future though breaking the taboo of unspeakable-topics and lead to individual openness, developed-values and extended knowledge.

This paper presents a case study that uses co-design to explore and create dialogue regarding structural racism in digital setting. Co-design is based on subject’s involvement and participation with an aim to generate new ideas and concerns through working collectively where participants contribute in design process without a need for pre-exiting knowledge about design and technology. Regardless of an agenda with democratic values, O'Leary et al. (2019) claim that participatory practices still carry the risk of continuing marginalisation, masked by the title of design. In this study, the theoretical framework stems from ‘design thing’ and Latour’s concept of ‘matters of concern’ combined with a creative participatory approach, co-design. The methodology derives from Sanders’ framework (2006, 2000) ‘say-do-make’ which is considered to be the engine in the design process from start to end. The design study relies on the digital realm (technical/digital imaginaire) to create a dialogue on structural racism. Several methods have been used when conducting the study such as online survey and digital workshops. Online survey was used as a method for data collection. The collected-data becomes a framework to build activities in the co-design/creative session. Digital tools such as Miro are used to design a template to be used in digital workshops/creative sessions. Three creative sessions have been taking place on Zoom, an online video communication tool where participants can discuss and bring more concerns into the matter of concern, structural racism. The results of the study suggest guidelines on how to create dialogue about structural racism through co-design environment, using digital tools. As a result, this study suggests that

4

interdisciplinarity is fundamental to integrate the matter of concern into the co-design discourse.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND AIMS

This design study aims to explore the possibilities of co-design to create a dialogue on a matter of concern (e.g. structural racism). With the main research questions, what could be the role of co-design when mediating/facilitating a discussion about structural racism? And how can we use digital mediums to co-design and create dialogue? This study’s contribution is to intervene into the co-design field and create a discourse where co-design as a field acknowledge structural racism and take ‘matters of concern’ into account. This study suggests that people who chose to participate in a dialogue are willing both to discuss the issue and imagining solutions. It also suggests that to create a successful co-design project regarding structural racism, interdisciplinarity must be integral in guidelines and methods to understand the matter of concern.

5

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

-

1. CO-DESIGN

Co-design is a design practice with a human-centred agenda. It could be understood as the involvement of individuals in participation, which generates ideas and insights. Yet, scholars and researchers have not established a unified definition to clearly define co-design. Therefore, co-design is often used as an umbrella term for participatory practice or co-creation (Cruickshank et al., 2016). A co-design approach is mainly, a public practice that aims to embed and enrich the participatory role of the users and designers. Further, it has been developed to democratise the design process. Sanders (2008) refers to it as “...any act of collective creativity…the creativity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process” (p. 6).

Similar to co-design, Participatory Design (PD) is an approach to encourage the engagement and collaboration of individuals/communities in the design process.

Simonsen and Robertson (2013) demonstrates the meaning of PD as:

“A process of investigation, understanding, reflecting upon, establishing, developing, and supporting mutual learning between multiple participants in collective ‘reflection-in-action’. The participants typically undertake the two principal roles of users and designers where the designers strive to learn the realities of the users’ situation while the users strive to articulate their desired aims and learn appropriate technological means to obtain.” (p. 2)

These roles of users and designers are beneficial when shaping PD as a practice. PD and co-design have helped the design field to shift to designing things “socio-material assemblies” rather than just designing things (objects) (Emilson & Hillgren, 2014, p. 68). Users/participants show their contribution and have a voice in the design process without a need for pre-exiting knowledge about design and technology. The contribution is reached through methods and techniques, which encourage human-object interactions (i.e. with tools and mock-ups). Designer, on the other hand, has through this approach a possibility to deepen the understanding of the users’ context in a mutual-learning practice. In the light of the similarity between co-design and PD, both terms are used in this paper conjointly.

Within the Swedish/Scandinavian context, where this study is conducted, PD is historically rooted. During 1970s, the idea of democracy for the labour force was reflected and applied through PD movement. The collective act and approach in Scandinavia completely transformed the labour sector and enhanced the workers’ rights leading to the conceptual thought of democratising workplaces (Szebeko & Tan, 2010). Ehn (1989) emphasises on workers’ rights, presenting acts and laws that enacted for better workplace in the 1970s. For example, Sweden passed a legal act that permits workers to be representatives on company boards. In Norway, computer professionals worked with the Iron and Metalworkers Union to boost the workers’ influence on computer systems in workplaces (Kuhn & Winograd, 1996). These changes within the labour sector altered the hierarchy of social structure between workers and management, which aided PD as a new approach to emerge. By using PD practice, they managed to include an oppressed group in the process and successfully change the system from within.

6

Co-design and PD have shown their impact when creating a democratic dialogue in relation to the workers’ rights movement in Scandinavia. Both are ways to gather heterogenous actors and focus on ‘matters of concern’ among participants. By focusing on participants needs, design goes from designing objects to ‘design thing’, which is the exploration of how to make a design relevant and create discussions that continues through collaborations to bring design forward. Emilson and Hillgren (2014) determine:

"Design thing should be considered as a process that involves both setting the preconditions for a process of change and opening up opportunities for new design things in which future users and stakeholders can discuss new matters of concern according to changed conditions and re-design the outcomes of previous design things”. (p. 69)

Discussing a matter of concern for instance, structural racism (as a product) requires an input (the dialogue as an outcome of ‘design thing’) to understand the issue. Inputs and insights open up opportunities for new ‘matters of concern’ through different perspectives embedded in the setting of ‘design thing’. In Nordic and Germanic societies, the word ‘thing’ refers to the governing situations/assemblies where political decisions and problem-solving actions were made. The origin of the word ‘thing’ helps to understand the concept behind ‘design thing’ as well as addressing the design of things as ‘matters of concern’ (Ehn, 2008).

1.2 Co-design in the Digital Realm

French techno-sociologist, Flichy, presents his understanding of the digital world as ‘technical imaginaire’. He defines the digital realm, the internet, as a collective-based project, producing visions and activities that carries out ideas and notions (Olesen et al., 2018, p. 2). Co-design within the digital realm is a way of exploring the ‘technical imaginaire’. By narrowing the concept of ‘technical imaginaire’ to ‘digital imaginaire’ it can be used to analyse how people interact within the digital realm (Olesen et al., 2018, p. 3). E.g. a study was conducted to test the users’ perception when using a digital co-design approach in hospitals. The findings suggest that people in the health sector prefer using a paper-based method in co-design rather than the use of digital ones. However, the use of digital methods can affect a co-design process in a positive way (Shi et al., 2015). Participants showed interest in the digital method through free-text comments and added suggestions for preferred digital-method such as visual enhancement, faster performance and more functions. Another co-design case study/collective project explores the usage of digital technologies in museum development, examining the challenges that might arise in design process. The study indicates that the challenges become visible in co-design activities when participants do not prioritise the collaboration. One noticeable challenge was a tendency that when a certain technological development shapes digital design, technology as result, overshadow the aim of participation and engagement (Olesen et al., 2018). Co-design carries the ideology of collaboration and engagement. If digital practices integrate with co-design to a higher extent it potentially can become an accessible tool for users, as findings show that some target groups still prefer paper-based methods. Flichy sociological views on technical development, as well as a macro perspective on collective visions, is a foundation when bringing the discourses together. Consequently, with an interdisciplinary approach between design and digital practices/‘digital imaginaire’, co-design would have the ability to explore and address the challenges that often emerge

7

within digital activities, challenges such as forgetting the human interaction aspect and overshadow the role of participation.

1.3 Co-design and ‘Matters of Concern’

Even though co-design and PD are based on democratic values, the discourse and method, often fail to incorporate and visualise ‘matters of concern’ into its field. ‘Matters of concern’ is the awareness of a situation as a whole and its consequences. Latour (2004; 2008, p. 36) describes it as “...shifting your attention from the stage to the whole machinery of a theatre”. As a discourse, co-design and PD are entwined with current infrastructures, language and artefacts which are developed on the basis of the current hierarchical systems of society. The discourse therefore often fails to, as Latour puts it, shift the attention to the whole machinery and overlooks ‘matters of concern’ outside of the field’s hegemony. Scholars today have taken interest in this inherent problem and have started to investigate and challenge the field. O'Leary et al. (2019) claim that participatory practices risk continuing racist legacies masked by the title of design, if the discourse does not take oppressions and marginalisation into account.) Further, the article argues that design workshops (co-design or PD) often overshadow local community understanding of design and rather favours the facilitator. If the design field manages to deal with its discourse and open up to ‘matters of concern’, it has the chance to create visions of what design methods could be outside predetermined hierarchies and structures. As the field is developed in correlation to the individuals who dominates it. Hankerson et al. (2016) present concrete examples of racial outcomes concerning technology in design processes. One example describes Apple iWatch and its pulse monitor, which is failed to detect heart rate on darker skin. Therefore, structural racism is one of many ‘matters of concern’ that is necessary to incorporate into the discourse.

2. STRUCTURAL RACISM

Modern society has to revisit old challenges, but as society develops, it is also faced with new ones. The increase use and demand for technology has made the industry into one of the most innovating fields of today, but its ethics has not necessarily evolved as quick. The fast development during the technological era has made new and/or upgraded problems to occur (Dachs, 2018). ‘Upgraded’ refers to old rooted problems that are made visible again by the evolution of society, and in this case technology. Even though technology desires to be a place for universal subjectivity or an objective source of data that can escape the limitations of race or gender, this is a proclaimed misconception. For instance, self-driving cars have complex issues regarding, the ability to detect people in front of the car. Programmers (mainly Caucasian) have failed to create a software where everyone according to skin colour, height and so forth, are detected equally (Wilson et al., 2019). A MIT technology review on self-driving car discusses the potential of autonomous cars to kill its owner in different incidents (Emerging Technology From the arXiv, 2015). Race, and the tech-fields invisible racism, is an embodied discourse in itself, people of colour have not been included to participate in the community or technological development. They become a community without identity in the technological field which Agamben refers to as a “whatever face” (Chun, 2009, p. 24). Old rooted colonial ideologies resurface into modern fields which has inherited historical belief systems and structures.

As presented, inherited racism is one of the historical ideologies which is still prevalent in modern society. Racism is an equivalent word for the individual and social body faced with inequalities due to skin colour or ethnicity. Nelson et al. (2011) describe racism as a phenomenon that causes inequalities, as well as inequity, in power and resources for

8

minority groups in society based on their cultural and ethnical background, or beliefs. Racism can be expressed in many aspects. Berman and Paradies (2010) give an understanding of a few aspects; 1) beliefs such as inappropriate thoughts in relation to stereotypes, 2) prejudice with regards to emotions, and 3) discrimination which is relevant to behaviours and practices that convey unfair treatment. Racism is an umbrella term under which many forms of discrimination are included and still actively operates on multiple levels; individual/ interpersonal, as well as structural/systematic. Many layers of racism have been made visible throughout history by people of colour, perhaps the most prominent one is being the civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Already then, a perfect example is given in the Black Power and Third World publication, which addresses levels of oppression concerning the African and Latin Americans’ struggle during the 1960s (Carmichael, 1967). The publication confronts the distribution of power, culture and calls for a united force between the two oppressed groups (African and Latin Americans). African Americans refers to their community as a colony inside the United States, which in many ways are a referral to the colonial times of the transatlantic slave trade. They highlight the structural injustices and the structural domination of white Americans. Seemingly, these revolutionary collective actions and events - that took place at that time - manifested and contextualised dimensions of racism from a historical framework as well as inherent institutional and structural issues. The civil rights movement made the issues more visible to the global public and expanded the horizon of what defines racism to include society’s institutions and culture (i.e. structural racism). Notions of individual, institutional and structural racism capture the important structural dynamics that shape the lives of people of colour to this day. Structural racism is the systemic, complex structure, presented, developed, and guarded by historically rooted, racial ideologies. A structural perspective helps to shift our attention from a single institution or interaction to inter-institutional and plural interactions. Structural racism is defined as the system in which public policies, institutional practices and other systems work in various, often reinforcing ways, to perpetuate racial inequality (Lawrence et al., 2004). Further, it is a result of historically accumulated white privilege, national values, and reinforced by contemporary culture. The structural model is a method to analyse how housing, education, employment, wealth, health care, and other systems interact and produce outcomes. Such model moves away from an individualised understanding of society and shows how all groups are interconnected and who it favours (Powell, 2008).

3. INSPIRATIONAL CASES

Within many fields, such as healthcare, design and HCI. Co-design is used to tackle and investigate discriminatory behaviour or action. For example, a case study within the Swedish health sector is currently investigating racism. The study is using a participatory approach to enhance equity in the healthcare system through building dialogue. The case study resonates the unspeakable nature of the Swedish society and the difficulty to discuss racism (Bradby et al., 2019).

In 2016, a research study called Becoming Woke was conducted, exploring design-engagement as a way to investigate and dismantle structural racism and white supremacy in a collective act environment through dialogue. The aim was to design a meaningful engagement in-situ to bring public awareness. The researcher went to a bar with a sign hanging on the back that said ‘I would like to have a conversation about race’ to invite random patrons into discussion. The result revolved around participants responses, assembled in a guidebook. The responses varied, from insightful to shallow, but worth mentioning is that many of the participants genuinely showed interest in exploring the

9

topic. The study also showed that white people were more likely to ask for validation when answering a question or explaining their ideas about the topic. People of colour showed support for the design practice and sensed the importance of the direct-approach when addressing complex social issues. Others disagreed and asked for the signage to be removed (McEntee, 2017). The conflicting opinions on the topic bring the issue into a realistic realm and helps the designer, and scholars to address the importance of the public when trying to find solutions or acknowledgements. Therefore, including public opinions in a matter of concern (i.e. structural racism) has the potential to understand the complexity concerning societal problems and retranslate it in an easy way instead of a complex one.

Africatown Activation, a collective project to build an installation that promotes and regains

the trust within the black community in Seattle, United States. The project involved

Africatown’s community, which included the town’s leadership, interns, designers,

developers and other communities. The project amplifies the involvement and the participatory role in communities introduced by PD and co-design using feminist ground and critical/speculative design as methods of data collection. As a result, they saw that the design played an active role both in productivity and engagement. The community meetings proved to be key when designing for the lived experiences of the people in the community. The design process helped people to become more active in their community as well as giving them a stronger hand when planning long-term redevelopment. At the end, authors send an invitation to the HCI community to be critically involved with the dynamics of race within the design process (O'Leary et al., 2019). This case study shows how co-design or PD can be successful when engaging a community and dealing with/confront structural racism.

Becoming Woke and Africatown Activation show the intention of confronting structural

racism. They used different approaches when addressing a matter of concern. Both cases are using a participatory approach as theoretical and methodological framework. One examines structural racism, offering the public a social practice that aims for change in society. The other reflects on community engagement as well as the importance of exploring racial topics through and within design process. In the light of both case studies, this paper takes these as an inspirational source to expand the discourse within the field of co-design. The aim is to acknowledge and embed racial issues such as structural racism in the field and explore what the role of co-design could be in this matter of concern within the digital realm.

10

METHOD

-

The study material for this paper relies on the use of digital tools in regards to data collection and the creative session activities. The employment of co-design methods and techniques can be beneficial for the idea of ‘digital imaginaire’ and subsequently, reactivating the notion of collectively in digital practice as well as inquiring the design process while using co-design.

One of the digital tools used in this study is an online survey, a fill-in electronic form, which includes questions concerning structural racism. The survey is designed for data collection purposes and spread online through social media i.e. Facebook (mainly Swedish-based networks)1. The information gathered, will be analysed and summarised to get an understanding of the participant notions regarding the matter of concern. Jones et al. (2013) emphasise on the pros and cons of the use of electronic survey as a method of data collection. The cons are concerning non-response and subjects’ accessibility. Not everyone can use or have access to internet, computers, or for many other reasons such as the inability of doing/completing the survey due to illness (i.e. blindness) or refuse to reply. Yet, there are significantly more pros, which include, for instance, larger target group, visual aids, quick response and quick data gathering.

1. SURVEY

Participants can take part in the survey anonymously; no names or any other identification is collected. However, at the end of the survey, participants can choose to submit their email if they want to participate in the creative session. Participants -who submit their email- get contacted and asked to sign a letter of consent in order to participate in the creative session through an online meeting room. The digital survey consists of eight questions regarding structural racism as follows:

1. Which definition of racism seems most accurate to you?

2. Where can you see the operation of structural racism in society? 3. Choose a value that society needs to fight structural racism. 4. What do you think is the reason of structural racism?

5. In what everyday life encounters have you or others you know, been confronted with structural racism?

6. What kind of platforms could be used as a tool to raise awareness about structural racism?

7. What is your definition of structural racism?

8. Are you up for an interview/workshop on Zoom, Skype, etc?

These questions are developed to deal with the matter of concern, structural racism. The aim is to collect answers, which can aid addressing the research questions, gaining an understanding of how the participants define the problem and designing the creative session/workshop activities. Each question aims to acquire an understanding of what participants think and what activities to develop. For instance, question number one helps the designer to apprehend how participants perceive the definition of structural racism 1 Facebook groups and pages : Malmö Student, The English-speaking: Malmö-dwelling Society, Innovative Social Research Methods and Migration Memory Encounters. Other groups/organisations were reached through Facebook messenger : Allt åt Alla International, Mångkulturellt centrum i Fittja. The survey is also published through personal networks.

11

which might vary from the definition used by the designer. The question gives insights about participants knowledge level. Question number four is designed to assist the designer when designing a tool-kit. The designer might find that the participants have either very different or very similar ideas on the origins of structural racism. Very different answers might indicate that the tool-kit has to be designed to find a common ground, yet, they could also be an asset on drawing a wider perspective. Similar answers could lead to a tool-kit that goes more in depth of the topic. Further, question number six is designed to understand what type of activity the participants are most interested in, regarding structural racism. The questions and answers are conclusively, designed to build tool-kit for the creative session and gain an understanding of the participants’ ideology and willingness to confront racism through co-design. The design of the survey is done through a digital platform called Typeform. It provides an easy interface for survey design and services.

2. CREATIVE SESSIONS / WORKSHOPS

Latour writes that, ‘matters of concern’ is to understand the political situation as a whole. The aim of the creative session is therefore to acknowledge and address structural racism from a holistic standpoint through dialogue containing a combination of individual experiences and opinions in a co-design environment. Co-design can provide a wide understanding of collective, individual, and contemporary experiences (Locock et al., 2014). After conducting the survey, volunteering-participants who had given their consent to partake in an online creative session, got contacted and scheduled for the creative session. Once time and date were decided, the participants got emailed a structural guide that includes information about the session. In the online meeting room, a digital tool-kit is provided, based on the survey answers. The tool-kit gives the participants a framework of working and discussing the topic. As the session is made online, the tool-kit is of importance to create a natural and dynamic dialogue through digital media. The creative session is designed to create dynamic discussion, time for reflection and possibility to create solutions by transforming individual elements (e.g. experiences and opinions) to collaborative ones (discussion and activities). Sanders and Stappers (2018) illustrates a wide variety of tools and techniques to be used in a co-design situated environment. Sanders describes a framework called ‘say-do-make’. The ‘say-do-make’ strategy is based on the following ideas; what people say (survey, research and fieldwork), what people do (ethnography), and what people make (workshop). The method works as a framework for the study, which is incorporating all of these steps in the co-design process. Creative session is conducted through Zoom.us. A shared-link is sent to participants to join the online meeting room. The virtual communication tool (Zoom) is very helpful when organising and streaming online meetings. For example, Zoom does not require singing in/up procedure for participant to join to the creative session.

2.1 Preparation for Creative Session

To decide time and date, the designer chose a digital tool called Doodle.com. It is a digital, collective tool that aids the process when scheduling meetings. Three date/time slots were decided by the designer and emailed to participants to vote which slot would suit them the best. The decision to have three workshops was based on number of participants in each group, digital convenience to have conversations with a smaller group and the possibility to compare the workshops when analysing the results. The email included an instruction PDF on how to vote on Doodle – in case participants had not used it before - and a deadline for the voting system. After the deadline, each participant was contacted with another email with the time-date-slot she/he voted for. Within the email, a guideline

12

for the creative session is provided. The guideline is designed as a tool-kit to organise and facilitate the dialogue (see appendix A for the guidelines). This guideline consists of; an overall summary on the project, what participants should bring or prepare, what is expected from them, the confidentiality, and most importantly, what kind of activities are planned in the online workshop. When preparing the activities for the creative session the designer planned it in three phases, first phase to encouraging dialogue, second phase to provide knowledge about previous design projects concerning structural racism and thirdly a collaborative workshop. To create dialogue in the first phase of the creative session the designer chose image studies ‘semiotics’ as a starting point, asking the participants to bring three images. Image studies asks the reader to think critically about images and image context and is a vital part of the field visual culture. Visual culture is culture and structures expressed through images and is incorporated in many academic fields such as art history, media studies, advertisement and cultural studies (D’Alleva, 2005). As participants might not be familiar with the design field providing knowledge about previous design projects concerning structural racism is an important element to the creative session. Designer prepared to present two inspirational cases in the second phase. Lastly, the designer prepared for a collaborative session, of importance was that the participants could work with a tool that is accessible and manageable, the designer then chose Miro. Based on question six in survey, the designer was interested to find out how the participants would create such platforms and planned an activity concerning platforms for dialogue. Further, the designer created a presentation to facilitate the navigation of the creative session and its three phases. The presentation works as visual aids and reminder for the participants of the aim of the creative session activities (see appendix B).

13

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

-

The ethical considerations in this study are intertwined with theory of co-design and the design process e.g. methods and tools. In theory and practice, co-design has its own embedded-values; towards human, by democratise workplace as well as human warfare and through practice, the accountability to address meaningful activities in everyday engagement (Friedman and Khan, 2002). In regards to the methods and tools, ethical considerations have been accounted for in various aspects.

For personal data, only necessary data for contacts where collected. The survey stated anonymity, the participants could exit the website at any point and the purpose of their contacts (when asked for) was stated in text. The tool used for the survey is a platform called typeform.com. Before using the tool, the designer checked the website privacy rules to make sure that the collected-data is secured and for protecting participants’ privacy according to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) standards2. To schedule the creative sessions, emails were sent with addresses hidden from the other participants. Signing up for the sessions on Doodle.com was made private, only visible to the designer. The tool is providing a service to promote anonymity, meaning that participants cannot see the names of the others while choosing time and date slot for the workshop. It is not always the case that participants in co-design prefer anonymity, however, in this case the use of anonymity is a way to build trust before the creative session.

The workshop concept was shaped around ethics. The designer considered transparency and the right for participant to know how their data would be used. For instance, the designer created a guideline to be sent to participant which included duration, activities, project information, the aim of the workshop, contacts, information concerning confidentiality to ensure transparency and some rules to minimise conflicts that may arise during the workshop. The participants are free to leave the discussion at any point and can choose to participate without showing their faces. Before participation, the letter of consent was sent to all participants to be signed and sent back. These letters are stored in the designer’s flash drive. The signed-letters are to be sent to Malmö University for assessment and archival.

For designer statement, see Appendix C.

2 For more information see EU data protection rules. European Commission - European Commission. (2020). Retrieved 19 April 2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/priorities/justice-and-fundamental-rights/data-protection/2018-reform-eu-data-protection-rules/eu-data-protection-rules_en. And General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Compliance Guidelines. GDPR.eu. (2020). Retrieved 19 April 2020, from https://gdpr.eu/.

14

ACTIVITIES

-

The activities are designed to address the research questions, which are the basis for this thesis; what could be the role of co-design when mediating/facilitating public discussion about structural racism? how can we use digital mediums to co-design and create dialogue? The designer has used Sanders and Stappers framework (2006, 2000) ‘say-do-make’ which includes different tools and techniques that help to address these questions. 1. SURVEY

The survey was up for answering between April 2nd and April 10th 2020. An overall review

on the survey’s result lean towards a none-response aspect with a 37.4% of completion rate and took almost eight minutes to complete. The survey got 67 responses, 26 are submitted via desktop-computers and 41 are done through phones (see Appendix D for the full results). The survey gave the participants a voice through providing some open-ended questions for participant to write their thoughts. Further, it provided an understanding of people’s knowledge levels and was helpful to see common grounds. Question one, where 46 responses (69.7%) had chosen the same definition of racism:

“… as not simply explicit attitudes but also implicit biases and processes that are constructed, sustained, and enacted at both micro and macro levels.” (Clair & Denis, 2015, p. 858)

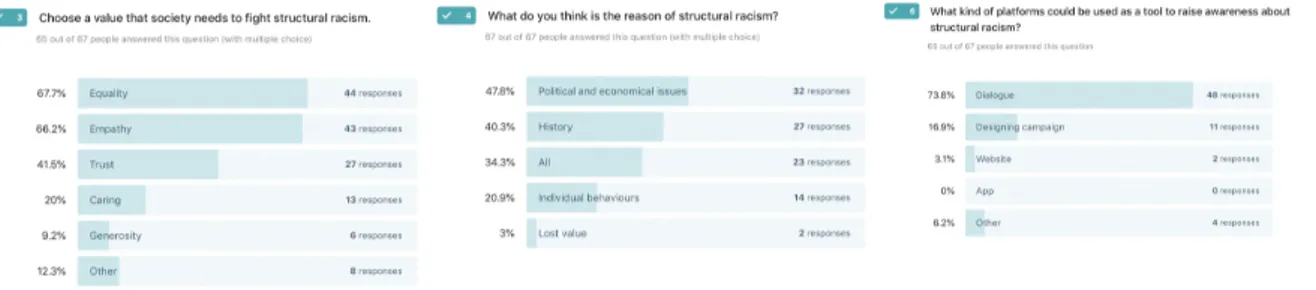

Another common ground was question three, where participants found ‘Equality’ and ‘Empathy’ the most important societal values to confront structural racism. Participants also brought more values into consideration such as transparency, bravery and a willingness to engage in critical reflection. Concerning ‘say-do-make’, the survey furnished the designer with an insight about what people ‘say’ through their answers. The answers of the survey are important to take into account when designing the creative sessions. After conducting the survey, some questions became noticeable and valuable for the creative sessions (see Figure 1).

Question three: Choose a value that society needs to fight structural racism? Question four: What do you think is the reason of structural racism?

Question six: What kind of platforms could be used as a tool to raise awareness about structural racism?

Figure 1. Questions and results used in the survey

The answers of the questions become the framework for the outline of the creative session as they are beneficial when considering method ‘say-do-make’. The survey is the ‘say’

15

stage of this study which led to the next steps, ‘do’ and ‘make’. Out of 67 responses, 23 participants submitted their email to be part of the creative session.

2. CREATIVE SESSION

The goal of the workshop is to explore the topic, structural racism through a dialogue using digital collective tools as well as finding ways to establish a dialogue about what many societies consider, inflammable topic. The survey helps to understand the interests of the participants and is used to decide activities and topics which are the most urgent to discuss. The creative session is divided in relation to ‘do’ and ‘make’. Firstly, each participant got sent out ‘Workshop requirements’ and ‘Rules’ which stated:

Workshop requirements:

- Three pictures which convey and reflect structural racism from political, economic, and historical perspective.

- Sign up/in for Miro.com. It is an easy digital collaborative tool. It is preferably if participant explores the tool before the workshop to understand how it works and as a saving-time strategy during the workshop. For privacy issue, participant can choose any user name if she/he does not want their participation to be shown with the real name.

- Pen and Paper.

- A signed consent-letter. Rules:

- Respect.

- There is no right or wrong.

- Acknowledging that we all have different perspectives.

- Speaker selection way will be through zoom chat. Participant who tends to speak has to write her/his name on the chat and as usual first comes, first speaks. There is an option to raise hand however; it does not show who raised hand first. Speakers are always having two or three minutes to draw her/his thoughts out. That depends on the number of the participants.

These rules are created based on rules and regulations commonly used on live stream services such as YouTube3 and Twitch4, both in relation to their community guidelines and individual content creators5. However, the designer adjusted the rules accordingly to suit the study’s setting (online workshop).

2.1 The Creative Session Implementation

Upon survey analysis, it became apparent that participants found the reason for structural racism is due to political, economic and historical issues. Meaning that the creative session would focus on these issues in discussion and activities. Almost 73% of the participants found dialogue to be the most beneficial tool to raise awareness about structural racism. The result indicates that the workshop should focus on platforms for dialogue and 3 See Policies - YouTube. (2020). Retrieved 17 April 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/about/policies/#community-guidelines.

4See Twitch.tv - Community Guidelines. (2020). Retrieved 17 April 2020, from https://www.twitch.tv/p/legal/community-guidelines.

5Example of one stream channel - Jennajulien. (2020). Home [Twitch Channel]. Retrieved 17 April 2020, from https://www.twitch.tv/jennajulien/.

16

collaboration aspects. The creative session was planned and divided into three phases with a total duration of two hours.

First phase: Discussion, this part is mainly to get to know each other. Reflecting on the answers from question four in the online survey, the participants will be asked to prepare visual representation that conveys structural racism in politics, economy and history. The activity is based on image studies ‘semiotics’, used in fields such as visual culture, media studies and art history. The activity was based on Ways of Seeing, (Berger et al., 1972) and

Methods and Theories of Art History (D’Alleva, 2005). Both of these books contribute to

analysing images, from advertisement to art works. Living in contemporary society means that we are continuously decoding images, we read them and understand their meaning, both unconsciously and consciously. This activity is based on knowledge that is inherent in our contemporary digital culture, as images on social media and advertisement is a constant in people’s daily life. The design method relates to the Sanders and Stappers (2018) ‘do’ as the participants own visualisation is the doing and not controlled by the designer. Visual representation plays a pivotal role when creating dialogue; it creates references and a common ground to base the discussion on. Each participant will be given two/three minutes to lay out her/his thoughts on the chosen images. The aim is to find a common understanding and language to lay the foundation for upcoming discussion. This creates a space to be listened to and to have a chance to express one self. (Duration 30 min) Second phase: The designer presents case studies to discuss. The two cases are Becoming

Woke and Africatown Activation, both mentioned previously in Inspirational Cases. The

designer briefly describes these cases and how they are using a participatory approach to examine structural racism, offering the participants a practice that aims for change in society. This phase is meant to give examples on co-design and participatory approaches that create a dialogue about structural racism and aims to display how co-design have been used when facilitating public discussion. The phase ends with a discussion regarding the pros and cons of these cases from participants’ perspective and is supposed to be inspirational for the third phase of the workshop. (Duration 30 min)

Third phase: Collaborative work; this section aims to design a framework for a project. The aim is to create a framework for “the most beneficial project based on dialogue regarding structural racism, for who, where, how?” The question emerges from the survey question number six, where most people answered that dialogue would be the most beneficial tool to raise awareness about structural racism. This stance is related to Sanders and Stappers ‘make’, as it is about creating a framework for what the participants consider the most beneficial project regarding structural racism. The designer sends a sharable link to participants, which redirects them to an online collaborative tool called Miro. The tool helps the group to co-design and share the same interactive online space. (Duration 60 min)

For the participants to create an interactive space, a template is designed (see Figure 2). The template includes four categories; target group, setting, method and collaboration. Under each, keywords are provided. Each participant will be asked to copy one keyword from each category and paste it in the empty column below. When all participants have put their most preferred keyword into the ‘Hypothetical project’s framework’, there might be a few different options, for example, target group might include ‘public’, ‘local community’ and ‘students’. The group is then to discuss the final one to choose under each category and that becomes the final result. The final result will present the participants’ perspective on what they considered to be the most beneficial project based on dialogue

17

regarding structural racism. The structure gives the possibility to see for who, where, and how? which shapes a framework for a future collaborative project presented by participants in an online co-design setting. As there will be three individual workshops, with different participants, the final result might differ but it will also provide the designer with information on how a successful project regarding structural racism might appear from different perspectives. Further, having multiple workshops gives an insight to the research question “What is the role of co-design when mediating/facilitating public discussion about structural racism?” as multiple workshops can manifest how co-design can be used when facilitating a discussion. Having multiple workshops give the possibility to compare and analyse the functions and dysfunctions of the co-design method from a broader standpoint. The result after using the digital medium, Miro.com will also show how digital mediums can be used to co-design, which is one of the important research questions.

18

RESULT

-

1. CREATIVE SESSION ONE

The workshop was conducted on April 20th. The duration of the session was one hour and

40 minutes in total. Four survey participants had signed up for the creative session nonetheless, only one joined in the end. At first, the participant6 was nervous, hesitant about the creative session, and expressed a worry due to the sensitivity of the topic. It was the first time for the participant to do an online workshop, yet, the participant was curious and prepared which reveals the role of the guideline in the preparation stance. As for the session turning into a one-on-one session, the designer role alternated between mediator and participant during the creative session.

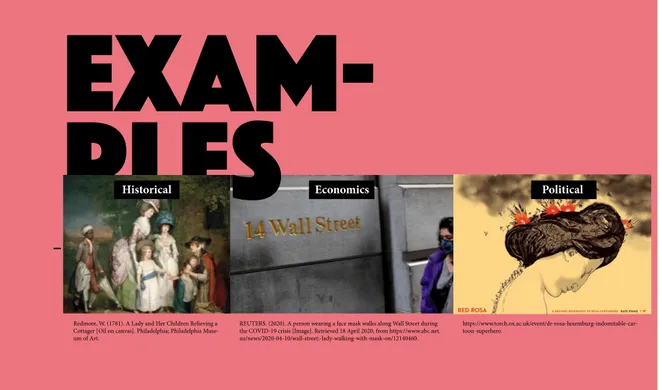

In the first phase, the designer started the discussion by giving examples of images which represented structural racism concerning politics, economy and history (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Examples of images provided by the designer

The shifting role of the designer -from a mediator to a participant- has rendered the designer to emphasise more on his image choices. This was done to create an equal dialogue and a balance in the discussion. Accordingly, the participant seemed to become more relaxed in the conversation and expressed themselves comfortably. The participant showed their contribution by presenting and reflecting on their three images. The images 6 All participants will be referred to with the gender-neutral pronoun they/them in the text; 1) to not reveal their identity/gender, 2) as a matter of respect if any participant does not want to be referred as she/he and 3) to promote inclusion. For more information, DesPrez, E., Baca, D., Blackburn, M., Chen, A., Coles, J., & Domínguez, M. et al. (2018). Statement on Gender and Language. [PDF]. The National Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved 4 May 2020, from

https://ncte.org/app/uploads/2018/10/NCTE-Statement-on-Gender-and-Language.pdf?_ga=2.49965670.1165997442.1588914408-1688763570.1588914408

Exam-ples

REUTERS. (2020). A person wearing a face mask walks along Wall Street during the COVID-19 crisis [Image]. Retrieved 18 April 2020, from https://www.abc.net. au/news/2020-04-10/wall-street:-lady-walking-with-mask-on/12140460.

https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/event/dr-rosa-luxemburg-indomitable-car-toon-superhero

Redmore, W. (1781). A Lady and Her Children Relieving a Cottager [Oil on canvas]. Philadelphia; Philadelphia Muse-um of Art.

19

conveyed colonial events, and an artwork about indigenous people in Colombia. Visual representation played a pivotal role to build a bond of communication between the participant and designer. The importance of the images was apparent later on, in the session. For example, participant stated that the dialogue created by images, led them think about one additional picture to present. Participant expected the designer to present more aggressive pictures, however, the diversity of examples presented by the designer opened up a broader understanding of the topic and eased its sensitivity. The participant understood that there were no restrictions in presenting any type of images and as a result they presented one additional image that aggressively captured structural racism within the societal level in a magazine advertisement in Colombia.

Second phase, the designer presented the two cases Becoming Woke and Africatown as inspiration. At first, the participant expressed hesitation regarding Becoming Woke mostly because the designer of the project was a Caucasian person. The participant doubted the design from an ethical standpoint and questioned if a Caucasian person could create a project about racism. Upon reflection, participant concluded that they cannot base someone’s abilities or perspectives based on skin colour, as this would be as much of an assumption as any other racial biases. Participant’s ability to re-think and reflect gave perspective on the subject structural racism. It changed the position from looking at it through a ‘skin colour’-based topic to a wider understanding of structures that might affect other groups and describe the ideology of society.

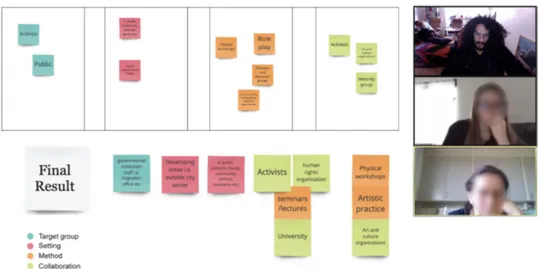

In the third phase, participant was left for a few minutes to do the activity in the predesigned-template in Miro.com. It took about five minutes for the participant to reach to the final result of a framework for future projects based on dialogue concerning structural racism (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Final result of session one.

Participant emphasised on the process of choosing between the alternatives under each category. For instance, at first, the participant chose physical workshops, role play, dialogue and consciousness raising group in the method-category. However, the final choice was ‘artistic practice’. Participant clarified that artistic practice became the final choice as it is broad enough to include all different methods mentioned in the first choices. The participant expressed the importance of changing the systems from within, through organisations/unions and creating, as well as collaborating with human rights

20

organisations that can give insights to peoples lived experiences. At the end of the session participant asked to be updated, which could be viewed as a successful workshop and the intention of future collaboration.

The designer considers that the third phase partly failed due to poor attendance. Since only one individual joined the workshop, the participant had to build the framework of the project based on individual preferences and, in result, the designer had to skip the collaboration part which requires more than one participant to contribute. However, this led the participant to elaborate more on the final result. Thus, the designer realised a way to develop the design method and added a section for participants to reflect on their collaborative ideas in Miro through the comment section. Even though the designer shifted into a more participatory role during the collaborative part, the designer was careful on his thoughts/assumptions, for them not to be explicitly embedded and translated into the final result.

2. CREATIVE SESSION TWO

The workshop was done digitally on April 23rd. The duration of the session was two

consecutive hours. Two participants out of three joined the creative session.

After creative session one, the designer revaluated the design process based on insights made during the first session. For example, the shifting role of the designer (between mediator and participant depending on situation) had led to richer discussion. The designer noted that discussion often ends sooner than it should. Therefore, the designer acknowledged the benefits of shifting the role throughout the session and developed the session accordingly. With the designer as a mediator in mind, more follow-up questions for dialogue facilitation was prepared such as; what principles do you see operating in the picture? could you please describe this principle? The designer further prepared to present and emphasise more on examples (images) comparing to creative session one. By acknowledging the time aspect, the designer added more time to the first phase in this session so participants could emphasise and reflect on their thoughts more. To develop the method, the designer explored more functions that Miro provides, which could be used in the session. Miro provides a section that allows to take notes. For session two, the designer planned to encourage participants to write thoughts, ideas, comments and summarise their project within Miro. This adds an element of reflection and ability to follow the participants thought in relation to the designer and each other. The designer added section on the third phase where participant can elaborate and reflect on their final result for their voices to be heard.

The first phase was time-consuming. One participant (P2) had no images to present and googled images during the session. On the contrary, participant (P1) started with an image that convey structural racism under the category ‘economy’. The image represents worker’s right from the perspective of low-paid-Mexicans who live and work in United stated. The ‘political’ image was regarding COVID-19, which reflects on how people with Asian heritage get treated due to the virus under a hashtag #IamNotAVirus. The image was a result of participant’s self-reflection. P1 realised that their search was too narrow at first, only including people with darker skin tone, but realised that racism is much broader and therefore, widen the search to look at racism from a bigger perspective. The ‘historical’ image was a black and white picture from the period of segregation in USA (according to participant) representing a sign with the word ‘colored’ and an arrow. The word ‘colored’ raised a discussion about the origin of the image as the use of this word was common in

21

South Africa for people with one white parent and one black. The discussion led to more enthusiasm ambience within the workshop. P1 provided an additional image with a suggested new category, ‘social’. The image was from an experiment conducted on black kids to choose a doll, one black and one white, based on an adjective (good/bad). P1 was enthusiastic to have brought a new category in to the workshop and was encouraged for contribution. The addition of categories could be seen as a result of providing more time for images, reflection and flexibility.

After finding images, P2 showed two images that combined the historical, economic and political aspects. Interestingly, P2 showed the same advertisement as the participant from session one - an advertisement from Colombia with white women and black maids. P2 presented a commentary to the first image; picturing black women nude and white maids. Despite the good intention, the second image still objectifies women, and class systems. P2 explained how both images received heavy criticism, and that the images uncover another structure, sexism. This reveals that even though focusing the workshop on structural racism, other intersecting oppressive structures often intertwine in topics surrounding oppression which Crenshaw (1989) calls ‘intersectionality’.

In the Second phase, the designer presented the two cases for the participants to reflect on. P2 stated that Becoming Woke can be seen as similar to this project since both create a temporary discussion and dialogue during a specific time and place. The session they were having during this zoom-meeting, was also a discussion facilitated during a temporary time frame. Regarding Africatown, P1 generally liked the design but hoped the project would include more of a culture exchange where people get to understand the culture more, such as food festival or activities. This way, more people would learn about cultures, as it could be a place to learn rather than just a physical space. This raised the question: It is a design space, but what do we learn from that place if there are no people? In Becoming

Woke the outcome is the discussion itself and learning from others in dialogue. On the

other hand, some people will not be comfortable going to Becoming woke, but comfortable to go to Africatown as it is less invasive.

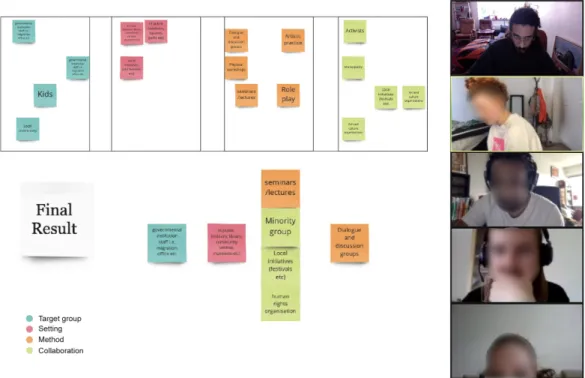

Concerning third phase, participants got 15 minutes to individually create a framework for a future project. When done with the individual choices, the designer asked both participants to collaborate and come up with the framework together.

The participants discussed their individual selection. By introducing the feature of writing notes, P1 had written down three different ideas on collaborative projects during the individual task, which led to better understanding between the participants. It also made it easier for the designer to understand the participant. P1 thought public and kids would be a beneficial target group while P2 was thinking about who would gain most from the project which was ‘governmental institutions’, stating that people who are furthest behind are often institutions. The participants then chose ‘government/’institutions’ in the category target group. In next category ‘setting’ the participants discussed the best setting in regards to their chosen target group. They discussed a setting that would be institutional ‘enough’ for the target group but still being an open space, so libraries and museum would be a good space (public/indoors). As the participants discussed, the framework grew, including both the seminars arranged by academics and the artistic practice in collaboration with activists and human rights organisations. These methods complement each other and could provide different kinds of knowledge. During this part of the session the participants started to discuss how the project might be planned, with actual program and seminars. Further, the participants found subgenres in the categories and how they

22

could be combined. They therefore chose more than one word under each category, something the designer had not reflected on being a potential outcome. They saw overlaps in multiple categories and discussed the differences, what do they mean and how could they benefit each other. An example, physical workshop could be many things, such as painting or walking. They also discussed who could organise what in the project and what the benefits would come of that, e.g. the benefits of involving activists, who have an understanding of the issue. The participants had a good discussion and expressed that they enjoyed working in Miro. They listened to each other’s concerns. This resulted in a diverse framework which they summarised as follows: The project is for staff in governmental institution. It is done in both public (library/museums) and developing area, the method is physical workshops (organised by activists and human rights organisation) and seminars (organised by university and activists such as Yalla Trappan). Designer then summarise the session. The two summaries were a way to show the participant that the designer had listened and tying everything together (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Final results of session two. 3. CREATIVE SESSION THREE

Five participants signed up for the workshop. Four participants attended to discuss the topic. Participants will be referred as Participant 1 (P1), Participant 2 (P2), Participant 3 (P3) and Participant 4 (P4). The workshop conducted on April 26th for a little more than

two hours.

As session one and two got a low number of participants, the designer changed strategy of communication. Differently from previous sessions, to lower the risk of participants dropping off, the designer sent out a reminder the same day to create awareness and trust. Session two, with two participants, had shown the benefits of the images as a conversation starter when more people participate. During session two, the images were beneficial to get to know each other and further expanded and developed during session three. The designer planned for more time to be spent on images and encourage the participants to bring more references during their discussion. Previous insights on Miro was further developed in session three as the designer informed the participants on different features that could be used such as notes, comments and drawing. As seen in session two the participants combined multiple categories, the designer developed the strategy in session three, encouraging the participants to add more than one keyword in the hypothetical

23

framework. P1 showed interest by stating that the reason for attendance was due to the existence of structural racism specially, in European countries and the unspoken nature about it. The online environment was lively as some participants knew each other which aids the level of comfort.

The first phase started with P1 sharing images, starting with the ‘historical’ category. It presented the accessibility of education world-wide on a world map which reflects on the equity through giving opportunities or possibilities based on people’s background. The second image was a representation of political marginalisation within the American politics. The image showed no representation of minorities amongst the governmental figures. The ‘economic’ image was an advertisement for a global fashion brand where a black kid is wearing a hoodie with the tagline ‘the coolest monkey in the jungle’. Interestingly, P3 added that the mother of the kid never reflected on the racial connotations until it became public. It shows racial biases within the industry and the design process, as well as the normalisation and its impact. It also conveys the hierarchy in decision making. P2 chose three images that intertwine all three categories. The first was an imagery of the slave trade which showed fictional events and presenting a setting where the slave and traders interacts on equal level. This image was made during the slave trade, probably as a propaganda to show that the slave trade wasn’t ‘that bad’. The second image was a screenshot from the cartoon shown in Sweden on Christmas. The cartoon was made in the 1930s and had stereotypes of both black and Jewish people. However, a few years ago the broadcaster removed the scenes that contain racial subjects. The ’economic’ image showed structural racism within design in a wide perspective. The image was a caricature of a Chinese person on the cover of a product package. The participants agreed on that companies have to be held accountable and take responsibility, as well as understanding and addressing structural racism. P3 displayed the ’historical’ through an oriental artwork made by a European artist. The image reflects on the perspective of ‘the others’, a concept by the West, particularly when traveling to other countries in the 1900th century. The second image, ’economic’, was capturing the representation of white dominance in boardrooms, where minorities often are excluded from decision making. The ’political’ image was of a boat filled with immigrants in the middle of the sea. This image was capturing structural racism reflecting on who is allowed to move and how. P1 brought up a new image from a French chocolate drink brand. The brand uses a stereotypical image of a black man. It has been controversial, but they still haven’t changed their logo. The brand is embedded into the French culture, but still embed structural racism within their design. What are the hierarchy in the design process, how can it go through so many layers in the company without anyone stopping it? This indicates the effect economic power has on the design process and how stereotypes are a way of branding/marketing. P4 reflected on the ’historical’ and ’political’ context with an image from an American prison which is overrepresented by black-American men. The discussion that followed addressed some reasons behind the large number of black Americans in the prison system. Main reason is being socio/economic problems in society, opportunities, risk of engaging in criminality and racism in the police force. The image also enriched the dialogue through a discussion on different documentaries and interviews the participants had seen. P4 placed the other two categories within the Swedish context. The ’political’ was a picture of a political leader that stated that people in Stockholm are smarter than people from smaller towns. P4 reflected that the politician by this create an us-and-them effect. The ’economic’ image was about a tax-reduction. Companies and individuals can get a tax-reduction for house services such as cleaning. The tax-reduction policy is made for people to be paid fairly. However, the group discussed how this is inherently a class issue and that a lot of people taking these jobs are from foreign countries.

24

The second phase started with no break by the designer presenting the two inspirational cases. P2 preferred Africatown project due to the importance of representing culture and creating new perspective for the future. The group discussed Africatown which was a product by and for community with a main purpose to regain pride within the black community. The project creates a feeling of belonging. However, if the project was done outside the community its publicity and impact could reach further. P4 reflected on

Africatown as a reference to Chinatowns around the world, because those are actually not

inclusive, they are built because people were excluded from the majority. On Becoming

Woke, P1 mentioned that the project’s setting could generate a diversity by inviting

random individuals but P3 found the project risky due to subject vulnerability. The problem with Becoming Woke is the inability to form long-term relationship due to the circumstances surrounding the project. Having sustainability in projects was an important aspect for participants. The group then ended this phase with a reflection, stating the importance of both cases as the results of either might manifest in the future.

Regarding the third phase, participants were asked to individually create a framework. The selection process went fast which indicates that the previous dialogue had setup a mind-set for the participants. The designer asked the participants to collaborate to create one collective project. Even though the participants had chosen different words, the common theme was ’change’ and finding projects that could create an actual change in society. As the group previously had talked about politics and uneven economic structures, the discussion led them to choose words which reflected this discussion. The discussion from phase one impacted the decisions in phase three. The discussion had led to a common ground amongst participants and it prepared them for collaboration and joint decision making. The designer noticed a diplomatic negotiation between the participants about the target group. P2 saw that change for kids is needed as it is easier to change/reveal values while kids are evolving. The others preferred ‘governmental institutions’ as target group because it is an important element in affecting society e.g. making decisions, universities, rules and laws. It was also noticeable that the participants in this session were interested in the social (see Figure 6). The final framework was stated as follows: The target group was ‘governmental institutions’ who would get lectures from local initiatives, minority groups and human rights organisations, after the seminars/lectures the target groups would have a chance to talk and discuss what they had learnt. At the end the participants showed appreciation for the digital tool, Miro.