MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHORS: David Frisk & Karl-Johan Edström SUPERVISOR: Timur Uman

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Audit rotation,

does it matter?

A study on audit rotations relationship to audit

quality and its contingencies

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our supervisor Timur Uman for his continuous feedback and suggestions on how to improve our work. For that we are truly thankful and without you this thesis would not have been possible. We would also like to express our gratitude to our opponents who have provided us with valuable feedback throughout this journey. Lastly, we would like to thank Jönköping University, including teachers and colleagues, for 4 years of great education and experiences.

THANK YOU!

Jönköping 2020-05-17

Abstract

Master Thesis, Civilekonomprogrammet Authors: David Frisk & Karl-Johan Edström Supervisor: Timur Uman

Examiner: Emilia Florin-Samuelsson

Title: Audit rotation, does it matter? A study on audit rotations relationship to audit quality and its contingencies

Background & Problematisation: Poor audit quality has historically led to huge consequences for the society. A low audit quality is often related to a low auditor independence, which can be caused by the auditor's incentive to maximize personal gain. In attempts to strengthen the auditor independence and thereby the audit quality, several audit regulations have been issued, where the mandatory audit rotation has been the subject to intensive debate. Although the previous research on audit rotation and audit quality is extensive, few studies investigate the contingency aspects of the relationship more specifically firm visibility.

Purpose: The purpose of the study is to explain how audit firm rotation and audit partner rotation relate to audit quality and how this relationship is contingent on firm visibility. Method: The study is conducted quantitatively using a positivistic deductive approach. Hypotheses are developed from existing theories and literature in the area. These are later tested by translating concepts into measurable variables. Audit quality has been measured through the proxy variable discretionary accruals which was estimated by two variants of the modified Jones model. The sample consisted out of 58 large-cap firms listed on the Stockholm OMX stock exchange, constituting a total of 580 firm years.

Conclusion: The results of this study suggest that neither audit partner rotation nor audit firm rotation has an influence on audit quality. Furthermore, these relationships are not found to be contingent on firm visibility. The study’s findings contribute to existing debate on mandatory audit rotation. However, the results need to be interpreted with certain caution as we cannot be certain that discretionary accruals measured audit quality as it was intended to do.

Sammanfattning

Examensarbete, Civilekonomprogrammet Författare: David Frisk & Karl-Johan Edström Handledare: Timur Uman

Examinator: Emilia Florin-Samuelsson

Titel: Spelar revisorsrotation någon roll? En studie på relationen mellan revisorsrotation, revisonskvalitet och dess modererande faktorer.

Bakgrund & Problemformulering: Bristfällig revisionskvalitet har historiskt lett till enorma konsekvenser för samhället. Låg revisionskvalitet är ofta relaterad till en låg oberoendeställning hos revisorn. Detta kan orsakas av revisorns incitament att maximeras sin personliga vinning. I försök att förbättra revisorns oberoendeställning, vilket också skulle kunna öka revisonskvaliteten, har ett flertal regler för revision utfärdats. En av dem är revisorsrotation, som har varit ämne för debatt. Fastän det finns många tidigare studier på revisorsrotation, har få studier gjorts på revisonrotation i förhållande till andra aspekter, i synnerhet företagets synlighet.

Syfte: Syftet med denna studie är att förklara hur rotation av revisionsbyrå samt rotation av revisonspartner relaterar till revisonskvalitet, och hur detta förhållande påverkas av företagets synlighet.

Metod: Studien har utförts kvantitativt med en positivistisk deduktiv ansats. Hypoteser har tagits fram med hjälp av existerande teorier och tidigare litteratur. Dessa har sedan testat genom att översätta koncept till mätbara variabler. Revisionskvalitet har mätts med proximal variabeln godtyckliga avskrivningar vilket har estimerats med hjälp av två varianter av den modifierade Jones modellen. Urvalet bestod av 58 large-cap företag listade på OMX Stockholms aktiemarknad, vilket utgjorde totalt 580 observerade företagsår.

Slutsats: Studiens resultat indikerar att varken byte av revisonspartner eller revisionsbyrå påverkar revisionskvaliteten. Vidare hittar vi inte att dessa sammanband är beroende på företagets synlighet. Studien kan bidra till den pågående debatten kring behovet av obligatorisk revisorsrotation. Däremot behöver resultaten tolkas med viss försiktighet eftersom vi inte kan vara säkra på att godtyckliga periodiseringar mäter revisionskvalitet som det var tänkt.

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problematization ... 4 1.3 Purpose ... 7 1.4 Research question ... 7 1.5 Limitations... ... 72 Literature review ... 9

2.1 Agency theory ... 92.2 The auditor’s role and procedures ... 10

2.3 Legitimacy theory ... 12

2.4 Audit quality ... 13

2.5 What factors influence audit quality and how ... 15

2.6 Audit rotation ... 19

2.6.1 Audit partner rotation ... 19

2.6.2 Audit firm rotation ... 20

2.7 Contingency aspects ... 21

3 Method ... 23

3.1 Theoretical method ... 23

3.1.1 Research position and scientific strategy ... 23

3.1.2 Theories of choice ... 24 3.1.3 Source criticism ... 25 3.2 Empirical method ... 26 3.2.1 Timespan ... 26 3.2.2 Sample selection ... 26 3.2.3 Data Collection ... 27 3.2.4 Limitations ... 28 3.2.5 Operationalisation ... 28 3.2.5.1 Independent variables ... 28 3.2.5.2 Dependent variable ... 29 3.2.5.3 Contingency variables ... 31 3.2.5.4 Control variables ... 32

3.2.5.5 Validity, reliability, and generalizability ... 36

3.2.6 Data analysis ... 37

3.2.6.1 Descriptive statistic ... 37

3.2.6.2 Normal distribution ... 37

3.2.6.3 Bivariate correlation analysis ... 37

3.2.6.4 Multiple regression analysis ... 38

3.2.6.5 Multicollinearity ... 38

4 Empirical analysis ... 39

4.1 Descriptive statistics ... 39 4.2 Dependent variable ... 42 4.3 Bivariate Correlation ... 43 4.4 Multiple regressions ... 454.4.1 Results of multiple regressions ... 45

4.4.1.1 Multiple regression with audit partner rotation as the independent variable ... 46

4.4.1.2 Multiple regression with audit firm rotation as the independent variable ... 48

4.4.2 Results of multiple regressions for visible and non-visible observations ... 50

4.4.2.1 Multiple regressions with audit partner rotation as the independent variable for visible firms………. ... 51

4.4.2.2 Multiple regressions with audit partner rotation as the independent variable for non-visible firms………….. ... 52

4.4.2.3 Multiple regressions with audit firm rotation as the independent variable for visible firms……….… ... 54

4.4.2.4 Multiple regressions with audit firm rotation as the independent variable for non-visible visible firms……. ... 56

4.5 Consequences for the hypotheses ... 58

5 Discussion ... 60

5.1 Introductory discussion ... 60

5.2 Audit quality and audit partner rotation ... 60

5.3 Audit quality and audit firm rotation ... 62

5.4 Visibility ... 63 5.5 Control variables ... 64 5.6 Final discussion ... 66

6 Conclusion ... 68

6.1 Conclusion ... 68 6.2 Empirical contributions ... 69 6.3 Theoretical contributions ... 69 6.4 Practical implications ... 716.5 Limitations and future research ... 72

References ... 74

Tables

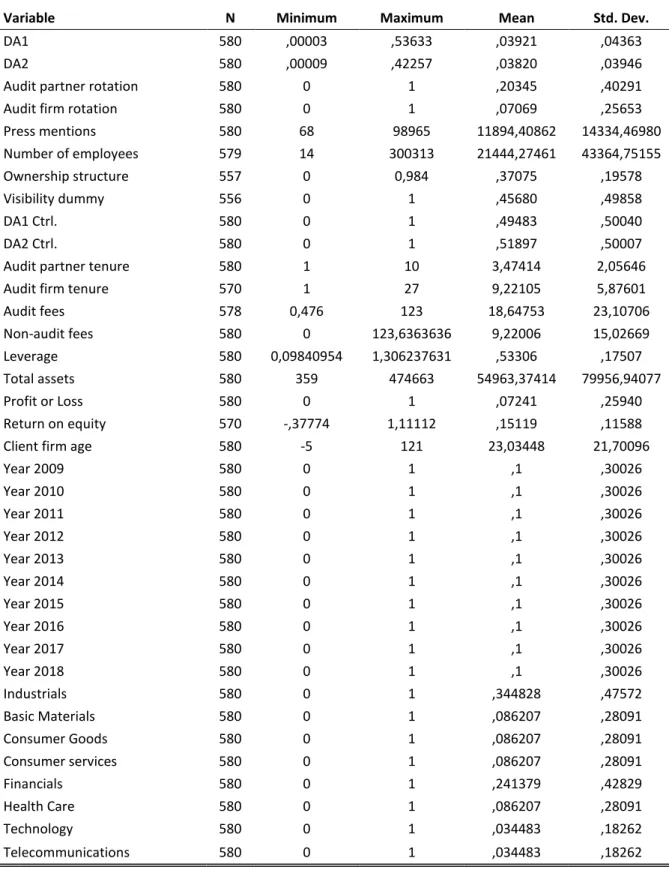

Table 1 - Results of descriptive statistics ... 41

Table 2 - Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for uncoded discretionary accruals ... 42

Table 3 - Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for coded discretionary accruals ... 42

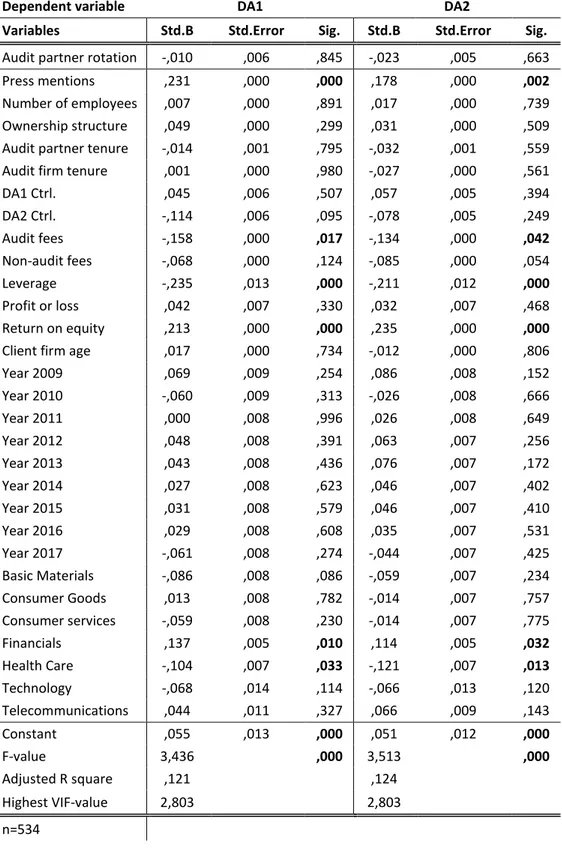

Table 4 - Results of multiple regression ... 48

Table 5 - Results of multiple regression ... 50

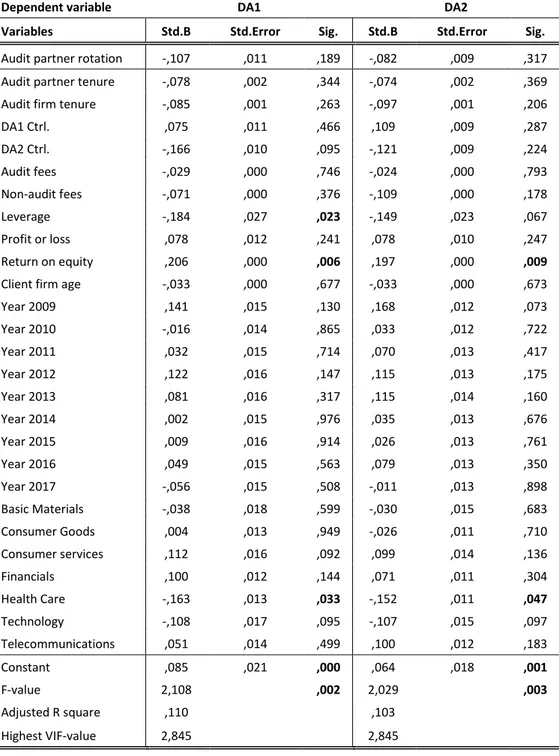

Table 6 - Results of multiple regression ... 52

Table 7 - Results of multiple regression ... 54

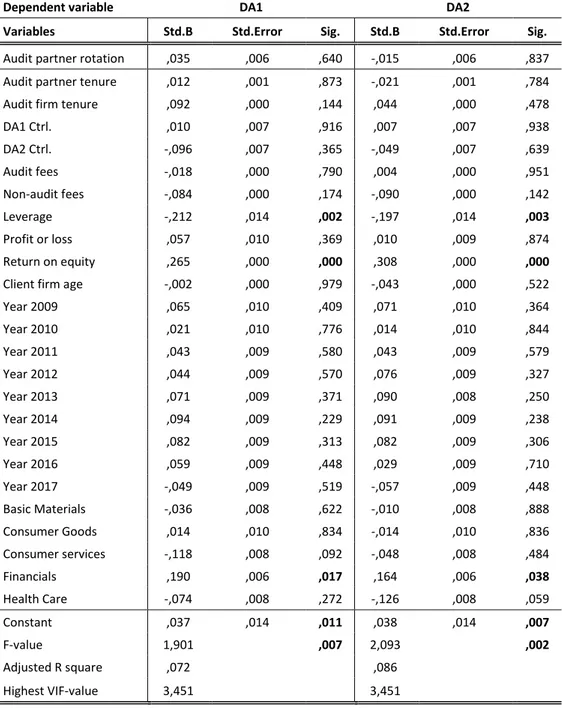

Table 8 - Results of multiple regression ... 56

Table 9 - Results of multiple regression ... 58

Appendix

Appendix 1 - Excluded companies ... 91Appendix 2 - Histogram DA1 ... 92

Appendix 3 - Histogram DA2 ... 92

Appendix 4 - Histogram coded DA1 ... 93

Appendix 5 - Histogram coded DA2 ... 93

Appendix 6 - Correlation matrix ... 94

1 Introduction

In this section, the background is presented, where the reader learns the importance of audit quality from the perspective of previous financial scandals. In the problematisation, a discussion is developed on how, and why the audit quality can be impacted by the auditor, audit rotation and other contingencies. The problematisation culminate in the research question and the purpose of the study. Lastly, the limitations of the study are presented.

1.1 Background

In 2001, Enron were caught using off balance sheet subsidiaries to hide losses and debts. In total losses of close to 600 million dollars, and debts of over 600 million dollars were hidden from the public for many years (Oppel Jr. & Ross Sorkint, 2001). Because of the discovery, Enron filed for bankruptcy (Degerfeldt, 2011). Even if Enron used poor accounting practices, their accounting firm, Arthur Andersen gave its approval. A fatal mistake for Arthur Andersen, as they also went under consequently (ABC News, 2009). In all, thousands of jobs, employer benefits, and large amounts of money from investors were lost (Bragg, 2002). Later, the next year, the telecom company WorldCom filed for bankruptcy after an internal audit discovered $11 billion dollars in expenses had been fraudulently accounted for through creative bookkeeping (Colvin, 2005). The bankruptcy of the once multibillion-dollar company, led to huge monetary losses for investors, as well as the loss of thousands of jobs. Colvin (2005) further explain that major players in the industry at the time before the bankruptcy, AT&T, Qwest and Global Crossing ended up firing employees, committing accounting fraud and, filing for bankruptcy respectively, all resulting from attempts to be able to compete with the later to be revealed fraudulent firm.

Lehman Brothers found themselves in a similar position when they filed for bankruptcy in 2008, which were one of the major players involved in the unfolding of the financial crisis in that same year (Chu, 2018). To this date Lehman Brothers bankruptcy is the largest ever to occur. One reason why the bank went under is due to the fact that the bank had invested, and owned large proportions of mortgage bonds, which were seen as safe investments, however, this mortgage bonds soon became worthless as the housing bubble burst (Stow, 2018). Even so, Lehman brothers were able to hide its losses for some time,

by for example using an accounting gimmick called Repo 105 (Clark, 2010). Lehman brothers auditing firm, Ernst & Young has been blamed for detecting errors, but not taking action (Söderlind, 2010; Friefeld, 2015). The financial crisis in 2008 led to huge consequences, where people lost their jobs, homes, and tax money because of bailouts for banks, and impacted the whole world economy (Mathiason, 2008; Uchitelle 2009). Common for all of the above-mentioned scandals, excluding the huge financial impact on the individual as well as entities, is that the external auditor either did nothing about the ongoing financial fraud or did not find any indicators of any wrongdoing in the entities financials until it was too late. In the light of financial scandals, the reputation for the audit profession have become a subject of public discussion. After the Enron scandal, the Swedish CEO of Ernst & Young at the time, declared that the audit profession and the audit reputation were under pressure (Edling, 2002). A study of a Japanese company that engaged in accounting fraud in 2006, found that PwC prioritised to increase their audit quality, to save their international reputation (Skinner & Srinivasan, 2012). Another Big accounting firm, KPMG is looking to improve their reputation after recent scandals, through increasing their audit quality (Kinder, 2020).

Audit quality is defined by DeAngelo (1981) as both the probability that an auditor will discover material misstatements and the probability to report them. Palmrose (1988) states that audit quality is the level of assurance that an auditor provides to the financial statements. The International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) breaks down the concept audit quality, by providing 5 elements of a quality audit. These consist of; proper values and ethics, sufficient auditors’ knowledge, control procedures in line with regulations, issuance of timely functional reports and proper relationships with relevant stakeholders (IAASB, 2014).

Comparing the previously mentioned scandals with the definitions and concepts of audit quality, one could argue that the audit quality has been poor in all three cases. In Lehman brothers and in Enron, the auditors most likely did detect flaws in the financial statements, however they did not take enough actions (i.e. low level of assurance), which per all mentioned definitions is a lack of audit quality (cf. Francis, 2004). For the WorldCom scandal, auditors failed to detect the financial fraud (material misstatements), again displaying a lack of audit quality per all mentioned definitions. This proves the importance of audit quality, as the consequences of poor audit quality in the mentioned

cases, has had a huge impact on society at large. A good audit quality would provide value to the shareholders. However, even if DeAngelo's (1981) definition is well used, the consensus on how to define audit quality varies, dependent on what attributes each definition focus on. Many of the frameworks are also incomplete. This means that it is not possible for stakeholders to view audit quality in its entirety (Knechel et al., 2013). Furthermore, it is hard to say whether an auditor should have detected certain misstatements or if it was right or wrong to issue for instance, a clean audit report for a company that in a short period of time went bankrupt. Therefore, one could argue that audit quality becomes more of an abstract concept than reality (Francis, 2004).

In attempts to assure and strengthen the audit quality, changes to the audit profession, as well as stricter regulations for the providence of non-auditing services has been installed. This has been done through both company laws and the creation of several audit oversight boards, with the purpose to protect both public and investors interests (Fuller, 2020). According to audit firms, the most questionable reforms, introduced because of recent scandals, is the those regarding audit rotation, (e.g. Ernst & Young, 2015). It is seen as questionable since switching auditor is thought to results in a loss of client specific knowledge, start-up costs and disruption of the organisation subject to the audit (Ernst & Young, 2015). Audit rotation refers to both audit firm rotation and audit partner rotation. Audit firm rotation is the act of changing the external auditing firm of an entity, while audit partner rotation refers to the act of changing the auditing partner of an entity without changing the firm responsible for the auditing (Ernst & Young, 2015).

In 2006, the EU commission issued a new directive regarding audit partner rotation. The EU Directive 2006/43/EC requires key audit partners in PIE’s to rotate after a period of 7 years. The directive requires a cool down period of 2 years, which implicates that the partner is not allowed to participate in the audit of that specific firm during the period. The purpose of this rotation requirement is like the audit firm rotation directive to enhance the independence of the audit (EUR-Lex, 2006). However, about audit partner rotation the EU commission later declared that just changing the audit partner that work within the same firm is not sufficient for increasing audit quality, since an audit firms’ main focal point will be on client retention. Therefore, pressure will be mounting on the new audit partner to keep the long-established connection with the client (European Commission, 2014).

In 2014 the Council of the European Union introduced such a reform through the mandatory audit firm rotation directive. The directive imposes periodical breaks for audit commitments in public interest entities. The objective of the reform is to increase the audit quality, by strengthening the independence of the auditor. According to the EU commission, there is an obvious risk with having the same auditor or audit firm for an extensive period. They state that this would erode the auditor independence, and consequently damage the professional scepticism. This is due to an extensive relationship that emerges with the client and the responsible auditor (European Commission, 2014). Whether regulation results in a higher audit quality remains to be seen. The construct audit quality is mainly based on individual perception (Gonthier‐Besacier et al., 2016). This would raise the question if audit quality and audit rotation is correlated at all. Assuming there is a correlation there might be other underlying factors that needs to be considered. From previous research we understand that there are a lot of aspects that could influence audit quality (e.g. Francis, 2004; Hoang Thi Mai Khanh, & Nguyen Vinh Khuong, 2018), but what they depend on remains unclear.

1.2 Problematization

One way of understanding the importance of auditor’s role and auditor’s independence is through the agency theory perspective. Within public listed companies, we have two different parties, where A is in control of the company (Agent), and B are the owner of the company (Principal) (Fülöp, 2013). However, there might exist misaligned interest for the two parties. This inclines the principles to install some sort of system that monitors the agent. (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Francis (2004) states, referring to the corporate governance issue, that external auditors have an important role in listed companies where ownership and control is separated. Watts & Zimmerman (1983) found that agency cost could be decreased through auditing. This would bridge the gap of interest conflicts between the two parties, if the auditor is independent, otherwise the monitoring system would be compromised (DeAngelo, 1981a; Khurana & Raman, 2006). If the shareholders’ value reduced agency costs, they should be striving for a higher audit quality. Francis (2004) explains that audit reports of high quality provide useful information to shareholders and other stakeholders. On the other hand, audit reports with low quality will provide little to no useful information, consequently, trusting a

low-quality audit report could increase information asymmetries and thereby agency costs will not be reduced.

Arel et al. (2006) explains that there are three threats that could have a negative impact on the audit quality. The first element is extended relationship between the auditor and the client, which enhances the closeness between them. This can be connected to the second element, which is the inclination for the auditor to satisfy their clients. The third one is the absence of attention to detail, which may origin from a long-term relationship between an audit firm, or audit partner with their client. Nasution & Östermark (2013) describes something called belief-perseverance syndrome, which means, in this case, that an auditor ignores new evidence, and fails to change their opinion. This is an effect of a long-term relationship between the auditor and client. A closer interpersonal relation between the audit partner and the client’s CEO has been found to impact the auditor’s independence negatively in several previous studies (e.g. Kaplan, 2004; Gavious, 2007; Chi et al., 2005). These problems could be connected to DeAngelo’s (1981a) study, where she explains that the value of the auditor's opinion increases when the auditor has a greater incentive to tell the truth. The probability of an auditor to report a discovered breach is also defined as auditor independence.

Audit rotation is a concept that was introduced as a way of ensuring the auditor independence, and thereby potentially improving the audit quality. In that case, it would help to mitigate the three threats that Arel et al. (2006) mentions. (European Commission, 2014). Research on overall audit rotation is mainly focused on investigating audit tenure and thereby investigating if there is a need for mandatory audit rotation regulations (Francis, 2004). The main arguments for mandatory audit rotation are that the independence of the auditor is compromised through the relationship that is built over a longer tenure (Francis, 2004). It is also argued that rotation resolve conflicts of interest between the client, audit partner and audit firm (Kalanjati et al., 2019). On the other hand, it is argued that the economic incentives of the auditor to keep the client, along with the rotation of other personnel engaged in the auditing will ensure the professional independence and scepticism of the auditor. Additionally, the acquiring of knowledge that comes with a new auditor is thought to decrease the quality of the audit initially (Francis, 2004).

When measuring audit rotation through audit tenure, findings of the audit rotations impact on audit quality have been divergent (Kalanjati et al., 2019). Previous research have both found a positive relationship between audit rotation and audit quality (e.g. Lu & Sivaramakrishnan, 2009; Blandón & Bosch, 2013), a negative relationship (e.g. Gul et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008; Fargher et al., 2008) and, no relationship at all (e.g Geiger & Raghunandan, 2002; Knechel & Vanstraelen, 2007). Mentioned studies and most of the previous research in the area, investigates the effects of audit rotation, but does not account for the different types of rotation (Mali & Lim, 2018). Kalanjati et al. (2019) explains that audit rotation can be achieved in one of two ways, either at the audit partner level, or at the audit firm level. Kalanjati et al. (2019) found that audit partner rotation increases the audit quality. However, it was also found that audit quality decreases when the audit firm changed. Similarly, Mali & Lim (2018) found that mandatory audit firm rotation decreases the audit quality, while Lennox et al. (2014) found that audit partner rotation at least initially increases audit quality. A longer audit partner or firm tenure is said to increase the partner or firm’s knowledge of the company subject to auditing (Kalanjati et al., 2019). Therefore, it is possible that the gap of knowledge is larger with an audit firm rotation than with an audit partner rotation, subsequently audit quality would be affected differently. However, the overall divergent findings would suggest that there are contingent factors that would affect the audit quality and audit rotation interrelationship. The characteristics of the organisations could possibly be an explanation (cf. Fiedler, 1964).

Although the research of audit rotation and audit quality is extensive, few researchers have studied factors that indirectly could impact the interrelationship. One aspect to consider is the visibility of the firm. Visibility could be explained as certain firm characteristics that makes the firm more apparent to the society. Brammer & Millington (2006) explains that the more apparent or visible a firm is, the higher the interest and attention from society would be, which in turn would increase the political and social pressure on the given firm. This pressure would also be transferred onto the auditors, who are responsible for the auditing in more visible firms. Accordingly, Redmayne et al., (2010) found that hours spent on auditing increased as the visibility of the firm increased. Such behavioural pattern suggest that auditors are more likely to increase their effort when there is more to lose in the eyes of the public. This is consistent with Walo’s (1995)

study, which found that auditor tends to excess more caution when dealing with high risk clients, which could include firms with high visibility.

Characteristics that affect the firm’s visibility commonly include firm size, press mentions and ownership structure (Bushee & Miller, 2012; Redmayne, 2010; cf. Dienes et al., 2016). It is understood that the visibility increases the larger the company is in terms of different attributes (Bushee & Miller, 2012). Press mentions can be understood to increase the visibility of the firm as the public is exposed to firm specific information through mentions in the press. Brockman et al. (2017) assumes that the ownership structure will affect the firm visibility, explaining that a larger institutional ownership attracts a larger public interest.

In conclusion, the increased caution resulting from the visibility of the firm tends to change the behaviour of the auditors, which implies that the audit quality could be affected. For instance, as the behaviour of the auditor changes, the auditor might be more probable to include material misstatements in the audit report. The auditor might also perform a larger substantive testing in the investigation, to enhance the assurance for the auditor. Consequently, this could mean that the relationship between audit rotation and audit quality is contingent on the audited firm’s visibility.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of the study is to explain how audit firm rotation and audit partner rotation relate to audit quality and how this relationship is contingent on firm visibility.

1.4 Research question

How does audit firm rotation and audit partner rotation relate to audit quality and how is this relationship contingent on firm visibility?

1.5 Limitations

As audit quality is more of an abstract idea, than a fully measurable concept, this study will need to use a proxy variable to measure the audit quality (cf. Francis, 2004). More so, this study will be limited to the extent that our proxy variable will estimate audit quality in a correct way. The same could be said about firm visibility, as it may also be measured in a variety of different ways, which will also pose as a limitation.

The mandatory audit firm rotation regulation has yet to come into full effect, with it being issued in 2014, with a possible firm tenure of at least 10 years (European Commission, 2014). This may hamper our sampled data, as companies are not forced to change their audit firm during our sampled years, so a limitation may be the lack of audit firm rotations.

2 Literature review

In this section, the reader is presented with relevant theories and literature related to the subject of the thesis. The first theory that are presented are the agency theory, to be able to understand the role and importance of auditing. The second theory is the legitimacy theory, to be able to understand the importance of audit quality both for auditors and firms. Later in the section, the reader is provided with a brief overview of the audit quality influences after which we argue for the importance of audit rotation in terms of audit quality. Lastly, based on the provided literature, the hypotheses of the thesis are developed which creates the foundation for the method.

2.1 Agency theory

The agency theory describes situations where one actor (agent) has been given the authority to represent another actor (principal). In economics, the agent is often seen as the management control of a firm and the principal as the shareholders (Fülöp, 2013). The agency theory describes that problems may arise when the interest of the executive management and shareholder is not aligned, commonly when ownership and management control is separated (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). The management may work for their own personal interest instead of the interest of the shareholders, finding reason to do so through knowledge gaps between the two parties (information asymmetries) (Fülöp, 2013). The difference incentives between the two parties could lead to something called agency costs (Jurkus et al., 2011). Even so, the shareholders can try to decrease the agency costs by aligning the interest of the parties, such as performance-based compensation or moral pressure. The performance-based compensation will reward the CEO when the CEO has maximised the shareholder value (Donaldson & Davis 1991; Jurkus et al., 2011; Heath & Norman, 2011).

Agency cost is a broad concept and can arise from a variety of sources. It could consist of recruitment costs, moral hazard, stealing, corruption, assurance costs or monitoring costs. (Shapiro, 2005). Monitoring costs is one of those costs that arise from the lack of trust. Due to the lack of trust, the shareholders (principal) will have an incentive to supervise and monitor the CEO (Agent) (Eisenhardt, 1989). Shapiro (2005) states that one way of monitoring the agent is through the auditor, using the financial statements. However, she also states that the relationship between the auditor and the principal will

also pose as an agency relationship, which would also be affected by the agency problems. So, the natural question that arises is, who monitors the monitors? (Shapiro, 1987). This paragraph describes that the role of the auditor is to monitor the agent. The principal in this case be the CEO, or the company. However, the auditor is likely to develop agency problems with the principal as well.

The agency dilemma between the company and the auditor origins from the contract between the two. The auditor is fulfilling the contract by providing services and performing an audit for the given company. In return, the auditor is expected to yield compensation from the audited company. The problem that arises is that the auditor will have a personal interest in retaining the client, i.e. the monetary compensation. (Gavious, 2007). Just as the CEO would have different incentives than the shareholders, the auditor’s incentives would also be different from that of the audited company. Auditors might be willing to overlook certain material misstatements in the financial statements to be able to produce a clean audit report, in the belief that this pleases the principals (cf. Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). However, the possible decrease in reputation as well as the threat of litigation issues that consequently could arise, is likely to restrict the auditor into maintaining his professionalism (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015).

Even so, if the auditor would still have monetary interest in retaining a client, it could harm the independence for the auditor. Hence the auditor’s role as being the median between the market expectations and the audited company would be disrupted, as the balance would shift towards the company (Gavious, 2007). One way of mitigating this agency problem could be mandatory audit rotation, which constrains the auditor from retaining the client (e.g. Mali & Lim, 2018; Kalanjati et al., 2019). The rotation mechanism and its impact on auditor independence will be further discussed later in this section.

2.2 The auditor’s role and procedures

As stated in the agency theory, an auditor's role is to monitor the agent, to bridge the gap between the principal and the agent. This means that the auditor reviews a given company (agent), to enhance the trust and assurance that the company's financial reporting are correct, which will add value to the shareholders (principals) However, the principals is explained to be far more than just the shareholders, it's important for all stakeholders, and

the society as a whole to be able to trust the financial reports and other information that companies release (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Eisenhardt 1989; FAR 2018). Pentland (1993) states that the main purpose of auditing is to enhance trust and give reliability to the stakeholders, due to the risk that the financial reports will reflect the agents (CEO/management) own self-interest. This is where the role of the auditor emerges. The auditor needs to, in a professional and critical approach: plan, investigate and give his or her assessment in relation to the company’s financial reports and management (FAR, 2018). This procedure is known as the auditing.

The first part, planning, is the procedure of gathering information and knowledge about the entity that is going to be audited. The information consists of both internal factors, such as buying and manufacturing processes, and external factors, such as competition and knowledge about the industry the company is working within. The auditor needs to understand the company, both internal and external to be able to do an effective auditing. By having a great knowledge, the auditor is capable of identify where the significant risks are for the specific company (FAR, 2018). Carrington (2010) states that an inadequate planning would increase the risk that the audit would be flawed.

The second part is the investigation, which is explained as a substantive testing of the result and balance accounts from the current recording. This to test if the financial records are fairly and accurately presented by the company. The auditor should concentrate his or her work on what they perceive as the most important part (Significant risks), which can be traced back to the planning phase. The auditor has an ongoing communication with the company's managers, to be able to ask critical questions, and get answers for any unclear or misleading statements from the current recording. (FAR, 2018; Carrington, 2010).

The third part is the assessment, where the auditor presents his/her audit statement. The audit statement should be a written document that is released together with the financial statements for the audited company and should include the auditor's notations and observations that were found in the investigation. However, the statement can never give an absolute certainty for the stakeholders, as the investigation process often only concentrates on the significant risks, while other accounts are not analysed (FAR, 2018).

2.3 Legitimacy theory

Legitimacy theory explains that corporations needs to follow the expectations of society to remain legitimate. The actions of the corporation can be important for legitimacy, but in the end, it is the society’s perception of the corporation that decides whether it is legitimate (Tunks, 1971). Legitimacy theory promotes the idea of an imaginary social contract between corporations and society. To fulfil the contract, corporations need to follow certain ethics and values that is of importance to society, most notably nowadays the environmental impact and awareness of the corporation (Deegan, 2019). If society perceives that the contract is broken, the corporation will lose legitimacy, and could face consequences, such as a decrease in sales. Legitimacy can be improved through higher reliable information disclosure, while a lack of information disclosure or reliability, in combination with a change in ethics and values can damage the legitimacy (cf. Deegan et al., 2002).

Legitimacy is a complex matter; it might be hard to understand if your corporation is legitimate. However, in the context of our study, we suggest that an auditor can either improve or impair the legitimacy. Through the audit of financial statements and the control procedures of a corporation, the auditors can ensure or/and explain ensuing of the social contract in those areas (Chelli et al., 2014). If the auditors explore e.g. misstatements or creative bookkeeping, they are expected to raise concerns in their audit report. This would be likely to result in raised concerns from investors and attract the eyes of the society and probably lead to a decrease in legitimacy. On the other hand, a clean audit report would improve rather than impair the legitimacy. Consequently, legitimacy is of importance to corporations (Tilt, 2003). Having that said, legitimacy can still be impacted or manipulated by the corporation itself (Deegan, 2019), such as recently discovered manipulations of sustainability reports (Littlefield, 2013).

Comparing legitimacy theory to the previously discussed financial scandals (Enron, Lehman Brothers and Worldcom), the society would have perceived the legitimacy contract to have been broken by those firms. Consequently, their reputation and trustworthiness were harmed. Whether the responsible auditors maintained a high audit quality is still a subject of discussion. However, the responsible audit firms as well as the audit profession had seen a decline in legitimacy (Holm & Zaman, 2012). This suggest that no matter the level of audit quality, the legitimacy can still be impaired by other

circumstances (cf. Holm & Zaman, 2012). The decrease in auditor reputation that stems from the decrease in legitimacy could also harm the perceived audit quality (Skinner & Zaman, 2012). Consequently, maintaining a high legitimacy is vital for the audit profession as well (Whittle et al., 2014).

In attempts to restore the legitimacy and thereby the perceived audit quality, regulatory bodies have, considering financial scandals, such as the previously mentioned, introduced new audit regulations (Holm & Zaman, 2012; Mali & Lim, 2018). In the context of our study, regulations on audit rotation is often introduced to meet this objective (e.g. European Commission, 2014). One of the main cornerstones of the audit rotation regulation is to enhance the audit independence, and thereby enhance the trust of the audit profession (European Commission, 2014). As the trust for the audit profession increases, the legitimacy would increase (Skinner & Srinivasan, 2012), which through previous reasoning would increase the perceived audit quality. However, if the actual audit quality is improved or impaired remains to be seen.

This subsection stamps the importance of having an auditor for the retainment of corporate legitimacy. With the assumption that a higher audit quality provides a lower probability of financial misstatements, legitimacy is positively correlated with audit quality. A lower audit quality would imply that the information is less reliable resulting in a less legitimate corporation. This subsection also provides an important understanding of the auditors and audit professions need for legitimacy.

2.4 Audit quality

Audit quality is an important factor in relation with legitimacy, to be able to distinguish whether the legitimacy has been improved or impaired. Just as the term quality, audit quality is often based on the individual's perception. Consequently, the definitions of this abstract term are many, and there is no overall superior definition (Francis, 2011). The most well-cited definition developed by DeAngelo (1981) describes audit quality as a factor of both the probability to find material misstatement and the probability that the auditor reports them. Finding material misstatements is referred to as the technical capabilities of the auditor while the probability that the auditor reports them refers to the independence of the auditor. Although the definition is simple to understand, it does not provide any measurements of audit quality. Whether the audit quality is high or low is

hard to tell with just DeAngelo’s (1981) definition. However, in the study, DeAngelo (1981) reasons that higher audit quality is more likely to appear in audit firms where the customers are few and small. He implies in such cases the audit firms have more to lose and therefore they would ensure a higher audit quality. If this is true, it would mean that effort increases audit quality.

In a later study Palmrose (1988) developed a new definition including a measurement for audit quality. He explains that audit quality is the level of assurance that an auditor provides to the financial statement. Thus, higher level of assurance would imply a higher audit quality. This definition is, however, old, and changes to the audit profession would have changed the definition of audit quality. In a more recent study, Francis (2011) provides six drivers for audit quality: audit inputs, audit processes, accounting firms, audit industry and audit markets, institutions, and economic consequences of the audit outcome. Audit inputs consist of the competence and independence of the personnel as well as the testing procedures and its reliability. Audit processes refers to decision making for implementing specific tests and the evaluation of those test. Accounting firm refers to the impact of the employer of the auditors. Audit industry refers to the impact of operating in a certain industry. Institutions affect the auditor's work through regulations. Lastly, similar Palmrose (1988), Francis (2011) describes the probability of economic consequences to have an impact on audit quality. Francis (2011) further explains that audit quality should be a continuum ranging from low to high audit quality. He states, that only focusing on audit failures for audit quality measurements shortens the spectrum and results in an unfair binary measurement of audit quality. With this broadened definition Francis (2011) provides a framework for how audit quality measurements could be extended from the traditional way of solely investigating a spectrum of high and low audit quality.

In more recent studies on the concept audit quality, Defond & Zhang (2014) states that a higher audit quality will increase the assurance that the financial report would be of good quality, hence, the audit quality is a component of the financial reporting quality. They extend this definition by stating that the financial reporting quality is reliant on the firm’s inborn characteristics and their reporting system, which would by definition also affect the audit quality. Laitinen & Laitinen (2015) extends on a previous definition by Knechel et al. (2013) to create a probability model of audit quality. The audit quality is explained

to be a factor of context, inputs, processes, and outcomes of the audit. The context includes the budget of the auditing firm, the complexity of the audit and the intrinsic risk of the client. Inputs is described as a factor of the experience and expertise of the audit which improves their investigational intuition. Processes refers to the efficiency of audit control systems as well as the performance of the auditor. The outcome of the audit is seen as the probability that the auditor includes at least one material misstatement in their audit report, given their context inputs and processes (Laitinen & Laitinen, 2015). Even if the performance in the factor’s context, inputs and processes is good the audit quality will not be at a high level if the auditor is not probable to include any material misstatements in the audit report (cf. Laitinen & Laitinen, 2015). Lastly, Knechel (2016) understand audit quality to consist out of the auditor independence and auditor knowledge, where auditor knowledge encompasses both the auditor’s expertise and his knowledge of the firm subject to auditing. High auditor independence combined with low auditor knowledge and, low independence combined with high auditor knowledge will not increase the audit quality. Only when the independence and knowledge are at the same increasing level, the audit quality is improved (Knechel, 2016).

This subsection provides an understanding of audit quality and its historic development. To later develop a framework for the audit quality and audit rotation relationship we deem it important to understand what audit quality persist of. For understanding how audit quality is impaired or improved, the following section will provide the different aspects that have been found to impact the audit quality.

2.5 What factors influence audit quality and how

Many studies in this area has emphasized on investigating different factors that could impact the independence of the auditor, implying that a decrease in the independence impairs the audit quality (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). Tepalagul & Lin (2015) investigates the previous literature findings of 4 potential threats to auditor independence. These include client importance, non-auditing services, auditor tenure and client affiliation with the auditing firm.

Client importance can be connected to what was previously mentioned in the agency theory concept. The client importance becomes a potential threat to the auditor independence because auditors are being paid by the same company that they perform

their audit on. This could lead to the fact that the auditor has a higher incentive to satisfy their larger clients, and yield to pressure, which would directly harm the auditor independence, hence, larger clients have a larger economic benefit for the auditor (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015; Chen et al., 2018). As less companies are required to have a statutory audit due to a more lenient audit regulation on a national level (e.g. Justitiedepartementet, 2010), the clientele decreases, which consequently intensifies client importance (cf. Zhang et al., 2014). However, there are also studies that do not support this claim (e.g. Chang & Kallapur 2003; Kinney et al., 2004). Chang & Kallapur (2003) found no significant relationship between client importance measures and abnormal accruals, used as a proxy for audit quality, which suggest that audit independence is not affected by client importance. One argument for why client importance does not seem to affect the auditor independence in these studies might be due to litigation, which means that the auditor might face legal action, which in turn would harm his or her reputation (Deangelo, 1981).

Non-auditing services is thought to influence the auditor independence and thereby the audit quality, as it is argued that an economic bond is created between the client and the auditor. When the auditor is providing more than auditing services, he/she becomes more dependent on monetary compensation from the client, which could make him/her willing to compromise his independence in order to retain the client (Francis, 2004; Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). However, other researchers take an opposite stance, arguing that providing non-auditing services increases the audit quality. Through increasing the auditor’s client knowledge by spending more time on the client, the auditor independence as well as the auditor expertise is thought to increase, which would mean that the audit quality improves (Hong-Jo & Cheung, 2017). The overall findings in this area have been divergent, often depending on the proxy used to observe audit quality (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). Recent studies have found both a negative relationship (e.g. Legoria et al., 2017; Hohenfels & Quick, 2018), positive relationship (e.g. Koh et al., 2013; Kowaleski et al., 2018) and no relationship (e.g. Bell et al., 2015; Hong-Jo & Cheung, 2017) between non-auditing services and audit quality. It has also been suggested that just the providence of non-auditing services can impair the audit quality. The perceived auditor independence is explained to be decreased when non-auditing services is provided which causes the perceived audit quality to be impaired (i.e. audit quality) (Kinney et al., 2004).

As for non-auditing services, auditor tenure is both argued to increase and decrease audit quality. The auditors increased client knowledge that comes from a longer audit tenure is argued to increase the audit quality as the expertise increases. The opposing side argues that the auditor is probable to develop a close relationship with management over a longer tenure and act in their favour, compromising his independence and thereby impairing the audit quality (Francis, 2004). Although the findings on the auditor tenures impact on audit quality is mixed, the empirical evidence suggests that there are little to no correlation between the two (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). Some studies suggest that short audit tenure is associated with a lower audit quality, when examining the quality of the financial statements (e.g. Jenkins & Velury, 2008; Bell et al., 2015). At the same time there is no observed difference in audit quality when comparing medium to long tenure (Jenkins & Velury, 2008). Other studies have found that the effects of audit tenure are often dependent on firm characteristics, namely industry, size, and political environment (Gul et al., 2009; Lim & Tan, 2010).

Client affiliation is explained to be the auditor’s closeness to the client (Firm). Client affiliation might become a threat due to three issues, firstly, the auditor might see the client as a future employer. Secondly, the auditor close relationship between the client (management) might harm the auditor’s relationship with the shareholders, which is the actual employer, not the management. Lastly, the relationship with former colleagues might affect the auditor ability to withstand a decrease in independence towards them. To meet these concerns, some regulations has been put in place, for example the Sarbanes-Oxley Act from 2002 which requires a cooling off period of 1 year before an auditor are able to work for a former client (Imhoff, 1978; Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). Some studies have confirmed these threats and found that an auditor is more likely to issue a clean audit report when performing an audit on a former employer, (e.g. Lennox 2005; cf. Ye et al., 2011). Lennox (2005) Also found that the auditor is more likely to issue a clean audit opinion for companies with affiliated executives (Management). More specific, Guan et al. (2016) found that auditors, who had a relationship with the executives of their clients from college, are more likely to issue a clean audit opinion. They also state that discretionary accruals are reported at a significantly higher level in these types of companies, suggesting that audit quality are negatively impacted by client affiliation.

Having said that, Francis (2004) found that evidence on client affiliation is limited, which might be since it transpires at a lower level than anticipated.

All the above-mentioned threats may decrease the audit quality as the auditor independence might decrease. Previous studies have suggested that audit rotation can alleviate threats connected to auditor’s independence (e.g. Blandon & Bosch, 2013; Mali & Lim 2018; Kalanjati et al., 2019). Audit rotation is closely connected to audit tenure as those who argue a longer audit tenure increases audit quality is opposing the idea of mandatory audit rotation regulations while others who argue the opposite is in favour of mandatory audit rotation (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). If the auditor is rotated on a regular basis, he/she might not be able to develop a relationship with the client and consequently maintaining his independence (cf. Chen et al., 2018). This would also suggest that the client affiliations impact on audit quality are reduced, as the relationship is shortened (cf. Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). Furthermore, retainment of the client is decreasing in importance as the auditor is obliged to leave the client after a certain time (Chen et al., 2010). Since the auditor have less incentive in keeping the client, he/she also might not be willing to compromise his/her independence, consequently the client importance negative impact on audit quality decreases (cf. Chen et al., 2010). The same goes for non-auditing services, as the rotation breaks the economic bond between the auditor and the client (cf. Hohenfels & Quick, 2018). However, some studies argued that the initial lack of client knowledge that comes with a new auditor harms the audit quality (Lennox et al., 2014; Mali & Lim, 2018).

Regulatory bodies have often attempted to improve the audit quality through regulations on mandatory audit rotation. In 2006 the European Commission issued a directive on mandatory audit partner rotation, requiring auditing partners to be switched after serving 7 years as the key audit partner (EUR-Lex, 2006). Some studies on the subject have suggest that the audit quality increases in the early years following the mandatory audit partner rotation (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2014; Lennox et al., 2014; Liao & Chi, 2014). Another study found that the introduction of such regulations has improved the overall audit quality (Monroe & Hossain, 2013). However, if the mandatory audit rotation leads to a rotation of the audit firm, the audit quality is decreased (cf. Mali & Lim, 2018; cf. Kalanjati et al., 2019). Surprisingly in the light of such findings, the European Commission and other regulatory bodies have introduced similar regulations on audit

firm rotation, that requires a rotation of the audit firm after a certain time (European Commission, 2014). In such cases where the audit quality is impaired by the regulations, it would become counterproductive, as the purpose is to enhance the auditor’s independence to improve the audit quality (EU Commission, 2014). In relation, some countries have introduced audit rotation regulations, but has abolished the regulation after a short period (e.g. Spain) (Ruiz-Barbadillo et al., 2009).

As explained above the effects of mandatory audit regulations have been divergent in auditor rotations impacts on auditor independence and consequently the effects on audit quality. Therefore, we deem audit rotation to be the most important factor to investigate. Through understanding its impact on audit quality, it will help regulatory bodies to understand whether there is a need for such regulations or if the regulatory focus should be put elsewhere for the purposes of improving the audit quality.

2.6 Audit rotation

Audit rotation refers to the act of changing the ultimate responsible external auditor of a given firm. Accordingly, mandatory audit partner rotation regulations only require the key audit partner(s) to rotate after certain period in the position (Firth et al., 2012). Practically this means that audit firms can deploy the same audit team except for the key audit partner. However, the rotation of the audit partner can sometimes lead to a change of auditing firm. Such rotations are referred to as audit firm rotation. Audit firm rotation is thought to decrease the risk of audit firms colluding with a client, while audit partner rotation is argued to improve the independence of the auditor as there is less time to develop a close relationship between the individual audit partner and the client (Mali & Lim, 2018). The main difference between the two types of rotation is thought to be the information and knowledge gaps that arise after the rotation, which will be extend on below. As the objectives and argued effects of the different types of audit rotation is different it is important to make a distinction between the two (cf. Kalanjati et al., 2019). 2.6.1 Audit partner rotation

Audit partner rotation is referred to the act of changing the key audit partner while maintaining the same audit firm. The empirical evidence on audit partner rotations effect on audit quality is strongly suggesting at least an initial improvement in audit quality after audit partner rotation, as a consequence of increased auditor independence (e.g.

Bandyopadhyay et al., 2014; Lennox et al., 2014; Liao & Chi, 2014; Kalanjati et al., 2019). As previously mentioned, the relationship is shortened through the rotation which enhances auditor independence. This explanation stems from the argument that independence decreases with a longer the audit tenure, as the risk of collusion increases (Mali & Lim, 2018). This risk could become apparent, both intentionally, and unintentionally from the auditor, where the auditor could favour the management instead of the shareholders. This would deteriorate the role of the auditor as an intermediary between the management and the shareholders, as the auditing statement become less reliable, which consequently would decrease the audit quality. Furthermore, as the audit firm is maintained, the client-specific knowledge is likely to stay intact as auditors in same audit firm easily can communicate with each other and thereby transfer important client-specific knowledge. Client-specific knowledge is of major significance on the auditing process, as the auditor needs to understand the client's industry, accounting policies and working procedures to be able to make a fair auditing assessment of the client. The transfer of client specific knowledge would help to alleviate the threat of a decrease in audit quality due to the transition (e.g. Bobek et al., 2012; Lennox et al., 2014). As the client-specific knowledge is maintained and the auditor independence is reassured through audit partner rotation, the audit quality would be improved.

Previous studies have suggested that the fresh perspective that comes with a newly appointed auditor, after audit partner rotation, increases the likelihood to detect material misstatements, consequently improving the audit quality (Favere-Marchesi & Emby, 2005; Lennox et al., 2014). This implies that a longer audit partner tenure decreases the accuracy of the auditor, as the auditor may become inadaptive to changes, due to his or her comfortability with the client, which would help to motivate a rotation of the audit partner. Taken together, this study has developed the following first hypothesis:

H1: The number of audit partner rotations is positively correlated with audit quality.

2.6.2 Audit firm rotation

Audit firm rotation is the act of changing the responsible audit firm, that said, the same audit partner can still be the responsible auditor. The purpose of the audit rotation is to increase the auditor independence, which would lead to a higher audit quality (European Commission, 2014). However, the empirical evidence often agree that audit quality is

unchanged, or negatively impacted by the firm rotation, which would deteriorate the outcome in relation to the purpose of the mechanism. (e.g. Jenkins & Vermeer, 2013; Mali & Lim, 2018; Widyaningsih et al., 2019; Kalanjati et al., 2019). Different explanations for why the audit quality decreases are provided. Opposite to audit partner rotation client-specific knowledge would not be shared between the successor and predecessor audit firm, which as through previous argumentation would impair the audit quality. The lack of communication could be traced to the fact that these two audit firms are competing, which would suggest that predecessor firm does not have any interest in sharing client information, which could increase the quality for successor audit firm (Kalanjati et al., 2019). The lack of information would lead to the issue that auditors would have to trust the information given by the audited companies managers, which could lead to an opportunistic behaviour and aggressive reporting, which have been found to impair audit quality (Mali & Lim, 2018). A second explanation is that the audit partner does not change (i.e. the audit partner gets an employment at another audit firm, and his or her customer are transferred to the new firm) which would hamper purpose of increased audit independence; hence the same audit partner is still responsible for the auditing. (Kalanjati et al., 2019). Therefore, the second hypothesis have been developed as follows:

H2: The number of audit firm rotations is negatively correlated with audit quality 2.7 Contingency aspects

Even though a lot of previous research suggests an increase in audit quality after audit partner rotation and a decrease in audit quality after audit firm rotation, the findings in the area is not unanimous, some empirical evidence suggest the opposite correlation (Litt et al,. 2014; cf. Corbella et al., 2015). Jenkins & Vermeer (2013) goes as far as suggesting that the empirical evidence on audit rotations impact on audit quality is inconclusive if not worse. This would suggest that there are other factors the affect the audit quality in relation to audit rotation (cf. Fiedler, 1964).

Previous studies have found that auditors are likely to behave different depending on the client’s characteristics (i.e. firm characteristics) (Walo, 1995; Redmayne et al., 2010). Redmayne et al., (2010) found that hours spent on auditing increased as the visibility of the firm increased. Visibility can include many firm characteristics that attracts the attention from society and therefore increases both the political and social pressure of on

the firm. This pressure is likely to be transferred on to the auditor, as the auditors is subject to a high level of scrutiny as the visibility increases, consequently their reputation is more vulnerable (Brammer & Millington, 2006). Hence, the auditors are more likely to act with more caution when dealing with more visible firms (cf. Walo, 1995). As the behavioural pattern of the auditor's changes, it is likely to affect the audit quality. Furthermore, research on audit tenures effect on audit quality have shown that the impairment of audit quality is often dependant on the firm’s characteristics (Gul et al., 2009; Lim & Tan, 2010). As previously mentioned, audit tenure has a significant impact on the audit quality in relation to audit rotation (audit partner and audit firm rotation), as both a stronger relationship is formed between the auditor and the client and the auditors client-specific knowledge increases the longer the audit tenure is (cf. Chen et al., 2018, Kalanjati et al., 2019). The auditor might be less willing to compromise his/her independence in visible firms and therefore the rotation would affect the quality less than in a rotation in a non-visible firm. Seemingly, the audit quality and audit rotation (audit partner and audit firm rotation) interrelationship is dependent on the audited firms’ characteristics (i.e. visibility). Therefore, the third and fourth hypothesis has been developed as follows:

H3: The relation between audit partner rotation and audit quality is contingent on firm visibility.

H4: The relation between audit firm rotation and audit quality is contingent on firm visibility.

3 Method

This section is divided into two major parts, theoretical method, and empirical method. In the theoretical method the reader is presented with the research positioning, an argumentation for the chosen theories and source criticism. In the second part, empirical method, the data collection is described, along with the operationalisation of the study, including choice of control variables. Lastly, the section data analysis is presented, where description of how the empirical tests have been conducted is presented.

3.1 Theoretical method

3.1.1 Research position and scientific strategy

The purpose of the study is to explain how audit firm rotation and audit partner rotation relate to audit quality and how this relationship is contingent on firm visibility. To fulfil the purpose, we have opted for a positivistic approach to the science, where the results for the sample aim to be generalized for the full population, which later can be of help to the society in the form of e.g. new regulations (Bryman & Bell, 2015).

The positivistic approach is recognized one or more of five characteristics. 1. Sensual knowledge can be recognized and presented as knowledge.

2. Hypotheses is created from theories and tested to allow for explanations of the

phenomena.

3. It is presumed to be conducted in an objective way, allowing for as little as possible

self-interpretation.

4. In order to gain knowledge, facts that create basis for laws has to be obtained.

5. Scientific statements are clearly distinguishable from normative statements (Bryman

& Bell, 2011)

The positivistic approach is mainly conducted inductively (4) or deductively (2). The inductive approach, where the researchers create theories from existing studies (Bryman & Bell, 2015), were deselected as previous studies were deemed to be insufficient to gather knowledge on the contingency aspects in the research problem. Instead, this study has chosen to implement a deductive positivistic approach, where we theories lay the

ground for the hypotheses. The researchers obtain data that is later tested empirically through translating the sometimes-abstract hypotheses into subjective and measurable concepts (Bryman & Bell, 2015). For instance, visibility have been translated into three factors that we understand to be a determiner of the term. Later in the research findings are analyses and compared with present theories to explain, understand, and prove causal relationships (Bryman & Bell, 2015).

The deductive approach requires a rigorous sample along with a high amount of objectivity if the findings are to be generalized for the full intended population (Körner & Wahlgren, 2015). Seeing as generalization is key for the study to provide guidance for regulators, we have chosen to investigate the research question quantitatively. A quantitative approach will allow us to gather large amounts of data (Bryman & Bell, 2015), and as we collect most of our data from annual reports little is left to interpretation by the researchers, consequently ensuring the objectivity of the study. If the study were to be conducted qualitatively, the sample size would be smaller and a greater amount of interpretation would be required by the researchers, consequently threatening the generalizability of the study (cf. Saunders et al, 2016).

3.1.2 Theories of choice

This study has opted to use four different theories to be able to understand and explain both the auditor’s role, and how different aspect may affect the audit quality. The given theories are: Agency theory, legitimacy theory, contingency theory, and behavioural theory.

Agency theory. As the purpose of this study is to explain if audit rotation affects the audit

quality, we use the agency theory to explain the auditor’s role, and how why the auditor may need regulations. The agency theory describes the relationship between two actors, the agent and the principal, and the difficulties that this relationship may face, due to differences in interest. (Fülöp, 2013). The differences in interest could lead to agency costs, which could be mitigated using an auditor. This is where the role of the auditor emergence, to monitor the agent (i.e. management of a company) on the principles (i.e. shareholders) behalf (Shapiro, 2005). Also, the independence or self-interest dilemma that may occur for the auditor can also be understood and explained through the agency theory, as the auditor can be seen as the agent, and the shareholders or the public are seen

as the principles. This implies that the auditor also needs certain regulations and control mechanism not to follow his or her personal interest.

Legitimacy theory. Legitimacy theory are used to describe how corporation uses certain

ethics and values that is of importance to society, to increase the corporation’s legitimacy towards the public (Deegan, 2019). This is also used to provide another explanation for why the auditor profession is important, which is to enhance the legitimacy for the corporations towards the society by controlling the financial statements. It has been found that if the trust for the audit profession increase, the legitimacy also increases, which implies that the audit quality is affecting the society. However, if the legitimacy is broken, regulatory bodies will try to enforce it, by issue new regulations, such as the mandatory audit partner rotation (EUR- Lex, 2006) and the mandatory audit firm rotation (European Commission, 2014)

Contingency theory. The contingency theory considers certain characteristics from an

organisation, that will affect the effectiveness of a certain situation (Mcadam et al., 2019). This helps us to understand that there are other factors that may affect the audit quality in relation to an audit rotation, stressing the need for contingency aspects in the study.

Behavioural theory. Behavioural theory assumes that people will act according to their

previous experiences and current environment (Kahneman, 2003). The theory is used to understand how the visibility of a firm can change the audit quality. Through adapting this theory to the auditor, we understand that he/she is likely to act different dependent on the visibility of the audited firm, as the environment would be different. If the auditor changes his/her behaviour the audit quality might be changed.

3.1.3 Source criticism

The academic articles in this study have been searched for and obtained, primarily using Jönköping University library database PRIMO, and secondary, Google Scholar. To ensure that the academic articles has high credibility and quality, all academic articles in this study is peer reviewed. A peer reviewed article is examined by experts for the given subject before publication, to ensure its quality. To the extent that is possible we have used articles published in journals that are highly rated on the Academic Journal Guide (ABS) list. The higher rated the journal is on the ABS list, the higher the reliability of the study (Bryman & Bell, 2015), which consequently makes this study more reliable.