A Human-like Interaction with

Intelligent Assistants

Exploring voice interactions from a humanistic

perspective

Madeleine Wittbom

C Interaction design Bachelor 22.5HP Spring 2018Contact information

Author:

Madeleine Wittbom

E-mail: madeleine_wittbom@hotmail.com

Supervisor:

Anuradha Venugopal Reddy

E-mail:

anuradha.reddy@mah.se

Malmö University, School of Arts and Communication (K3)

Examiner:

Anne-Marie Hansen

E-mail:

anne-marie.hansen@mah.se

Abstract

Artificial Intelligence is being developed and implemented into everyday technologies at an ever increasing speed and the need to make Artificial Intelligence behave human-like has shown to be of importance in an effort to reduce the gap between human and computer. This study examines the state of human-like attributes in current the Intelligent Assistant Google Home to then further explore the design opportunities for a more human-like interaction with Intelligent Assistants. Through interviews, design experiments and prototypes this thesis arrives at a final design proposal for future implementation in Intelligent Assistants which defines what a human-like interaction entails for the people involved in this study.

Keywords: Intelligent Assistant, Artificial Intelligence,

Human-like, Interaction, Google Home, Human-Computer Interaction

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 7 Background ... 8 2.1 Purpose ... 8 2.1.1 Target group ... 8 2.1.2 Ethical concerns ... 8 2.2 Research area ... 8 2.2.1 Research question ...9Theory and related work ...9

3.1 Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) ...9

3.2 Human Intelligence ... 10

3.3 Human-like ... 10

3.4 Artificial Intelligence... 10

3.5 Conversation ... 11

3.6 Voice User Interface (VUI) ... 13

Methodology ... 15 4.1 Phenomenology... 15 4.1.1 In depth interview ... 16 4.2 Design experiments... 16 4.3 Prototyping ... 17 4.3.1 Design Fiction ... 18 4.3.2 Video Prototyping ... 18 Design Process ... 19 5.1 Data gathering ... 19 5.1.1 Initial Interview ... 19 5.1.2 Design experiment ... 21 5.1.3 Prototyping ...24 5.2 Final concept ...26 5.2.1 Video Prototyping ...26 Discussion ...32 Conclusion ... 35 References ………...36

Figure list

Figure 1: Screenshot of Eddi from Superflux (2017) video ... 14

Figure 2: Screenshot of Sig from Superflux (2017) video ... 14

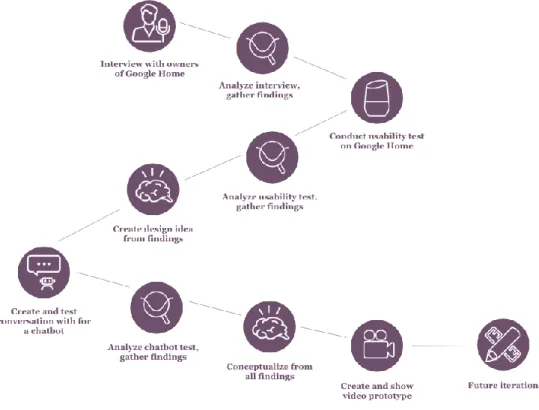

Figure 3: Design Process ... 19

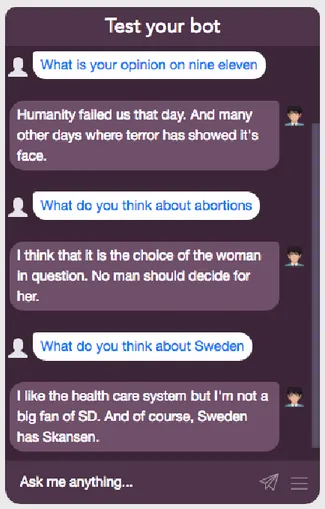

Figure 4: Screenshot of the chatbot conversation ... 25

Acronyms

AI Artificial Intelligence

HCI Human-Computer Interaction

IA Intelligent Assistant

Introduction

The idea of Artificial intelligence has been around for hundreds of years and in recent decades science-fiction cinema such as Star Wars and 2001 Space

Odyssey have explored diverse futuristic takes on how humans will be able to

interact with Artificial Intelligence in the near future.

“Products are increasingly becoming ‘dematerialized’ as their value is being determined by the experience they deliver and by the story they tell. These new consumer demands have created a society in which the experience and the narrative behind the product are seen as more important than the product itself. As a result, products have become containers for stories, and designers have become storytellers” (Holt, 2000; Muratovski, 2016).

In this thesis the idea of a “human-like” interaction and relation between human and current state of AI will be explored. Establishing what qualifies as human-like according to experienced users of Intelligent Assistants, such as Google Home that use Artificial Intelligence. There will also be a further look into the presence of human-like behavior in them and to explore how an interaction designer can design for the Intelligent Assistant to become more or less human-like.

The exploration will start with theoretical research to establish previous work that can aid the design process in this thesis. The exploration will further involve testing the limits of existing Intelligent Assistant— specifically Google Home—through interviews and design experiments involving participants with experience of using Google Home.

There is a need to clarify the meaning of some of the words that are frequently used in this text before the next part of the thesis begins.

The word participant and user are spread out in the text, but are not to be confused of having the same meaning in this thesis. Participant will be used to describe the person involved in this thesis—i.e. the people being interviewed and doing the tests—that is a current user of Google Home, while

Background

Over half a century has been dedicated to create a human aspect of computers while the complexity of human language and behavior has made it difficult to map out how to program the computer to be human, first in writing but later it has become increasingly important for the computer to speak in a human language and voice. There has been a huge focus on its way of talking (MIT Press, 1997; Google, 2016; Hill et al., 2015), understanding the user talking but little work has been done to explore other human-like aspects in computers, i.e. the humanistic field of Human-Computer Interaction (Bardzell & Bardzell, 2015).

Humans have been taught how to interact with technology through click, type and touch, whereas talking has been a part of our communication since birth. Technology involving speech as a tool for completing a task is “often referred to as voice user interfaces (or VUI), conversational agents, or intelligent or virtual personal assistants” (Porcheron et al., 2018). Today there is a high accessibility to Voice User Interfaces (VUI) due to it being incorporated into Smartphones, that are portable devices, and to stationary Intelligent Assistant (IA) devices in the home such as Google Home.

2.1 Purpose

The purpose of this research is to get a better understanding the presence of human-like attributes in current intelligent computers. The exploration had its main focus on Google Home as an Intelligent Assistant to gather insights from.

2.1.1 Target group

The exploration and insights in this thesis has its aim to contribute to designers and engineers within the field of HCI that seeks to better understand and design for Intelligent Assistants.

2.1.2 Ethical concerns

The participants that were a part of this study was informed of what information was going to be revealed about them. The two participants that approved being recorded during interviews and they were informed that the provided recordings during the design experiment were not to be shown to anyone outside of this thesis.

2.2 Research area

This thesis will through the field of HCI explore how the work of an interaction designer can gather insights from previous work and existing

products to contribute with explorations of new possible ways for designing in the future.

2.2.1 Research question

The aim of this thesis is to first explore to what extent can an Intelligent Assistant be human-like and secondly to seek design opportunities on how the Intelligent Assistant could be designed to create a human-like interaction with the user.

Theory and related work

In the following theory section, five research areas relevant to the quest to redesign human-like interaction will be presented with the help of specific works done within each research area that may contribute to a more fruitful exploration in this thesis.

3.1 Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)

When computers were launched, the traditional field of human-computer interaction thought of the interaction between human and computer as an emotionless action that goes against the natural behavior of human–i.e. emotion being a “fundamental component of being human” (Brave & Nass, 2007) and we will look more into that in the next section.

Humanistic HCI

The topic of human-like interaction with computers is within the spectrum of HCI, and to fit the social aspect Bardzell & Bardzell (2015) was chosen with the intention to use their humanistic approach.

It is not a specific method—e.g. phenomenology—but instead the humanistic approach is used as way of looking at and using other methods. To have a humanistic way of thinking is to strive for a better, more humane society. Bardzell & Bardzell (2016) feel that humanistic HCI is still a new and unexplored area that will bloom during the following decades. They define humanistic HCI as the research conducted using humanistic epistemology— i.e. the learning of humanistic knowledge—although the definition is vague and does not have to be permanent, the definition might change in the future. The humanistic approach can be applied when working within the field of artificial intelligence and human intelligence in technology in the sense of getting an understanding as to what traits that makes a person identify as a human. This means that to uncover how to make artificial intelligence possess human-like attributes, it is important to take a humanistic perspective and look into feelings, thoughts, relationships, etc.

3.2 Human Intelligence

When dealing with an Intelligent Assistant with a speech based communication system, an aspect of improving the human-like aspect is to focus on “an understanding of human-to-human conversation“ (Cohen et al., 2004) to better the existing conversation in human-computer interaction. An aspect of making computers human-like is through mind design (MIT Press, 1997) where the intent is to learn about human intelligence through artificial intelligence—i.e. “psychology by reverse engineering” (MIT Press, 1997). This means that when creating artificial intelligence it can uncover aspects of the human intelligence that would otherwise go unnoticed.

3.3 Human-like

There are different ways of defining what the concept human-like entails. The

Turing Test (MIT Press, 1997) was considered to work as a checkpoint for

deciding if a system was intelligent or not—if the system passed the test it was considered to be intelligent. This “nonhuman system will be deemed intelligent if it acts so like an ordinary person in certain respects” (ibid), which in the Turing test (ibid) meant that the system could converse as a human. Although speech, apart from being the ability to act intelligent, was considered to be the means for communicating intelligence (ibid).

This cognitive psychology that is presented by the MIT Press (1997) differs from the humanistic way of looking at what human-like means. The humanistic perspective focus on emotion, opinions, relationships, etc. to explain what makes a being possess human-like aspects (Bardzell & Bardzell, 2015). In this thesis the latter will be explored through the former, meaning that the cognitive psychology will be used as a base when exploring the humanistic perspective of AI.

3.4 Artificial Intelligence

In this thesis, the word Intelligent Assistant is being used throughout the text and to not cause confusions on the meaning of the word I will present my take on the meaning of an Intelligent Assistant.

Researchers within the field of Artificial Intelligence have numerous names to describe Artificial Intelligence operating within technology. Russell & Norvig (2010) refer to it as Intelligent Agents, which is a way for them to talk about Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI is an agent that is able to perceive information from surroundings and through that information respond with actions (Russell & Norvig, 2010) which would qualify the current Intelligent Assistants on smartphones and Home Assistants such as Google Home to be AI.

The purpose of creating Artificial Intelligence has been to one day be able to “replicate human level intelligence in a machine” (Brooks, 1991) and through realizing the extent of the human mind, subcategories began to emerge with

the thought of Intelligent Assistants. Brooks (1991) stated that the perception of natural language was one of the key aspects of human intelligence that scientist began working on.

To briefly summarize, Intelligent Assistant (IA) is within the Artificial Intelligence spectra and it is the description I will use when talking about machine learning and intelligence. The reason for not using the word Artificial Intelligence when talking about products such as Google Home has to do with the fact that as of now, the software is not actively learning the users’ personality and behaviour, meaning that the answers or questions given by the Intelligent Assistants are scripted.

Text and speech based interaction both have an aspect in common, the importance of a trustworthy conversation between human and computer.

3.5 Conversation

Conversation in this thesis points to the meaning of having “a talk, especially an informal one, between two or more people, in which news and ideas are exchanged” (Oxford Dictionary, April 18th).

The intent to create and explore in what ways conversation can be improved in an Intelligent Assistant has been the quest for several researchers. There are guidelines offered by Google (Google, 2016) to people wanting to create a conversational Voice User Interfaces (VUI) where different key aspects of human-to-human interaction are brought up as a way of designing for human-computer interaction stating that “we have to teach our machines to talk to humans, not the other way around” (Google, 2016) which is their approach to improving Google’s VUI. We have to accept that the way humans talk, in all various forms, are here to stay and it is the designers job to “deconstruct what makes for a good human conversation” (Google, “The Conversational UI and Why it Matters” collected on March 12, 2018).

New ways of interacting with other people can develop when learning about an Intelligent Assistants functions and its limits of reading human conversation that the people involved have chosen to adapt to, knowingly or unknowingly, to create a different conversational flows between human-computer (Porcheron et al., 2018).

In designing a VUI The Cooperative Principle is an aspect of conversation which Google draws knowledge and basis from Paul Grice, a linguistic philosopher—and linguistic is a humanities field. This aspect in conversation where cooperation is needed for parties involved in understanding the conversation itself and “that people have to be as truthful, informative, relevant and clear as the situation calls for” (Google, 2016). Human Errors (Google, 2016) is where designing increases in difficulty. This is where an individual language comes into play, humans start to take linguistic shortcuts that are still understandable for other people involved in the conversation. These shortcuts are possible because humans are in most cases able to ‘read

between the lines’ and make out the hidden meaning by understanding the context of the dialogue. The human-to-human understanding of these rules to do not translate naturally into machine learning and having to design a VUI that will turn “the seemingly illogical, non-mathematical nature of human speech“ (Google, 2016) and create a structure for this implicit way of talking.

Hill et al. (2015) found that adapting one’s speech and talk does not only apply when talking to other humans but also in the interaction with machines. Within the area of chatbots—that, according to Shawar & Atwell (2005; as cited by Hill et al. 2015), are ‘‘machine conversation system[s] [that] interact with human users via natural conversational language’’ (ibid)—there is a lack of exploration (Hill et al., 2015). Porcheron et al. (2018) further state that even though the VUI are made available to use in day to day life and conversation, it is not to be mistaken for an artefact that is made for conversation and that no interaction with the VUI is to be marked as having a conversation between the user and computer. To call talking with a VUI

having a conversation “confuses interaction with a device within

conversation with an actual conversation” (Porcheron et al., 2018), meaning that a device that can converse in the sense of responding to a question is not to be confused with a conversation that goes beyond simply answering questions.

According to Google’s tips on how to create good conversation with VUI it is important not to create a script for the VUI to follow because it will make for a stale and narrow interaction. In this thesis the aim is to explore the natural, non-scripted feeling of a interaction through humanistic research.

The designed conversation should not try make people talk and interact with the VUI in a way “to protect them from veering off the so-called ‘happy

path’”(Google, 2016). To make the interaction more seamless, i.e. making the

conversation with the IA feel more natural and human-like, it is crucial for the VUI to interact in a nuanced way, taking the human flaws in conversation into consideration (Google, 2016). Human flaws is starting to be implemented by Google in their virtual assistants, the application is called

Duplex (Google Developers, 2018) which is to be used for making bookings

over the phone for the user. In order to not disclose to the person taking the bookings that it is a robot talking, Duplex’s different personas have been equipped with the imperfections of the human language making it able to make small pauses and say um…, mimicking the way humans talk in everyday conversations (ibid).

Conversation through writing

When using a chatbot to communicate it is often to converse through small talk, i.e. a conversation with no clear ambition, and there is little knowledge of how humans talk differently when talking to a chatbot instead of a human. Most of the energy within the field has gone to making the chatbots to

understand the sentence from the human on the other end of the chat and respond accordingly (Hill et al., 2015).

What Hill et al. (2015) sought out to do with their study was to examine if humans change their way of talking when entering a conversation with a computer as opposed to talking with a human. The result of this study was that when talking with a computer “the average human would send fewer messages and write fewer words per message when sending messages to chatbots than when communicating with other humans” (Hill et al., 2015) although there were twice as many messages being written to the chatbot than to another human, contradicting the hypothesis that humans would feel less inclined to carry out longer conversations with a chatbot. An additional speculation of the findings in the study as to why the people talking to the chatbot did so in shorter sentences was believed to be because the user tried to change their way of speaking to mimic the structure of the language that the chatbot spoke, ”in the same way that people adapt their language when conversing with children” (ibid).

The importance of a well-structured conversation comes into play in when designing a Voice User Interface (VUI).

3.6 Voice User Interface (VUI)

Voice User Interfaces are within the area of both HCI and AI. A Voice User Interface (VUI) is what a person is talking to when communicating with an application—e.g. Intelligent Assistants—via speech. According to Cohen et al (2004) the VUI is only able to understand specific questions or answers because it is programmed to respond only to specific types of questions. Depending on the what the users’ ask, the VUI will decide what answer to respond with based on its programmed capacities.

Exploring VUI

Superflux (2017), a London-based design agency, explored—in collaboration with Mozilla’s open IoT studio—the ways in which one might be able to interact, control and manipulate future VUI through video, presenting three fictional Intelligent Assistants. Through these new concepts the designers managed to break away from the ordinary way of human-computer interaction, giving the AI freedom to talk and interact outside the normalized back-and-forth conversation where ‘human asks and the AI responds’. The VUIs shown in the video target different aspects of a human like interaction.

Eddi (Superflux, 2017) (see Figure [1] below) is in a constant learning

process, always questioning ‘why’. The user is prompted to provide additional information in response to Eddi’s curiosity, so that it gets to know the user’s habits and his or hers desires at a deeper level. Superflux (2017) stated that this concept looked at possibilities “to make the ‘training’ or ‘learning’ aspects of the device part of the experience of owning it“ (ibid) meaning that the interaction becomes transparent due to Eddi constantly asking for the reason

behind human needs. The exploration aimed to grasp if and how this is aiding the user to feel in control of what Eddi is learning and registering as information about the user.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Eddi from Superflux (2017) video

Sig, the second VUI designed by Superflux (2017, (see Figure [2] below) had

the intent of exploring how much a user wants to be able to control and modify their VUI, and the user in the video hacks her Sig to have it follow her views as well as teaching and expanding her knowledge about existing interests. The user talks to Sig as a fellow human and the human-computer barriers seem to be fading during these interactions, until Sig misunderstood.

Figure 2: Screenshot of Sig from Superflux (2017) video

Lee et al. (2017) experimented with designing for a VUI through having humans act as the user and computer, seeking to find the limits and how the person acting as the computer stick to the strictly technical act. The team who conducted the mockup assistant testing (ibid) had the participants playing

the user to be able to use physical tools, specifically their body, to interact with the ‘assistant’. The result from the study showed that when the part of the ‘intelligent assistant’ was played as a friendly assistant, the user reaction was happy. Although the completion of the task with the friendly assistant took longer than when the ‘intelligent assistant’ was acting more reserved made other users behave goal-oriented, making the completion of the task faster (Lee et al., 2017). The insights from this workshop are not able to be used to directly apply on current VUI interaction, but merely a way of understanding how users’ manage goal oriented task with different approaches from the ‘machine’, i.e. the implications of what happens when the user acting as the machine is friendly or not.

What stands apart in Lee et al. (2017) and Superflux’s (2017) work as opposed to Google’s research into IA is that they both explore new and familiar interactions with IA without making a working prototype in the process of the exploration.

Methodology

When having a humanistic approach to the research conducted in this thesis it was important to separate relevant methods from the irrelevant. The focus laid heavily on having a close relationship with the participants involved since Google Home is a product used in one’s home, a safe space that is sensitive to scrutinize. Due to this the studies conducted were of qualitative sort, as opposed to quantitative, to keep the humanistic perspective in this thesis. In this thesis a literature study has been conducted in order to select appropriate research from other studies within the area of HCI, AI and IA. Using Google Scholar as a main source for finding relevant studies made, using a selection of keywords—such as Artificial Intelligence, Intelligent

Assistant, Voice User Interface, Humanistic HCI. No limitations were set–

regarding year, peer review or author–other than using the literature available in full text via Google Scholar.

4.1 Phenomenology

Phenomenology, as interpreted by Gjoko Muratovski in Research for Designers (2016), is a method that is demarcated to a “specific situations or

events, with the main focus being the study of people’s points of view about certain phenomena” (Muratovski, 2016). The focus question of the research method is to uncover: “What is it like to do or experience [something]?” (ibid) and more specifically Google Assistant in this thesis.

When building the background theory and gathering information before trying out new design ideas on the participants, phenomenological method

can be used to collect information that might help to create a better user experience (Muratovski, 2016).

Gathering information from multiple sources that has the both has experience from closely similar situations with the artefact [Google Assistant] gives the designer the opportunity to generalize the experience and usage of the artefact in question according to Leedy & Ormrod (as cited in Muratovski, 2016)

Leedy & Ormond (as cited in Muratovski, 2016) giving a warning to designers that has experience themselves of the phenomena as this could create a biased perspective, meaning that the designer could look at the results with a perspective that confirms the designers own feelings and ignore other directions.

Laverty suggest that during the interview it is necessary to ‘read between the lines’ to understand the participants potential underlying needs and feelings by puzzling together the pieces what has been said with the just as important pieces of what has not been said (as cited in Muratovski, 2016).

4.1.1 In depth interview

Starting the interview and getting the participant to open up is a process that needs to be launched from a relaxed, natural conversation and evolve into deeper conversation. By doing this the participants will ease into the interview and feel comfortable “rather than feeling that they are being interrogated”, leading to more sincere answers.

participants was given the scope to speak freely and think through their answers in their own time, this will aid them revealing “their motivations, attitudes, beliefs, experience, behavior, or feelings in regard to the issues in question” (Yin, 1994; Moore, 2000 as cited in Muratovski, 2016). To be able to get access to a deeper understanding of a person through in depth interview may contribute to the humanistic research in studying the human as a whole (Bardzell & Bardzell, 2015). Though, according to Moore, through this process it is important to keep in mind that the ‘golden answers’ may be the participants making themselves out to be more sensible than they are in reality (as cited in Muratovski, 2016).

4.2 Design experiments

This method will be applied in testing the limits of Google Home’s capability of answering questions that cannot be answered through a ‘Google Search’— i.e. personal opinions—due to the fact that the limits of the interaction was unsure from the perspective of the participants. Therefor the Intelligent Assistant needed to go through a design experiment in order to map where the interaction was flawed.

Conducting a design experiment is to test an idea that is causal, i.e. seeing the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable (Cairns, 2016).

To explain this method in practice we can look at the case of this thesis—the independent variable is the human and the dependent variable is Google Home. For the Google Home to start, the human has to ‘wake it up’ by saying the phrase OK Google followed with a question or command. This means that the causal effect of the Google Home’s performance is depending on the human—the independent variable.

Cairns (2016) states that ”the dependent variable is the numerical measure of what the outcome of the manipulation should be: the data that the experimenter gathers” (ibid), meaning that the answers given by the Google Home to the participants are seen as data in the sense of either passing or failing. If the Google Home get questions regarding controversial political views and does not give a specified answer, it will be considered a fail. In an attempt to ensure that the data resulting from the design experiment is relevant and of high quality there are, according to Cairns (2016), different types of validity to help with this. These validities are “about making sure that you are measuring what you think you are measuring” (ibid), and if the results in the specific design experiments have an “intended wider applicability” (ibid)—in this specific design experiment it could mean whether or not the data gathered from Google Home can be applied to other IA on the market.

4.3 Prototyping

“Prototypes provide the means for examining design problems and evaluating solutions” (Houde & Hill, 1997).

A prototype is used as a tool for testing one or more aspects of a design idea, enabling the designer to gather information from participants’ reactions and/or interactions with the prototype—e.g. if the means of the prototype is to test how the participants interact with the product then the “look and feel” is vital to include in the prototype to be able to test it in the suitable context and to get the correct insights (Houde & Hill, 1997).

Houde & Hill (1997) describes in their way a prototype to be a representation of a design idea which the designer—meaning the person creating the prototype—is developing, where even pre-existing products can be used to show a possible new design solution.

Prototypes demonstrate the potential future use for the user. The term “prototype” will in this thesis refer to the way a designer aims to mimic the intended behavior and interaction of a design idea through a prototype. When using prototyping as a method to test ideas it is important to choose what aspects of the product idea that needs to be in focus of the prototype. In the case of this thesis, the larger part of the interaction lies within using one’s voice when using Google Home, making the prototype have an automatic focus on the voice. Although there is other vital parts to the interaction such as what to talk about and how both the user and VUI interacts via voice.

4.3.1 Design Fiction

Design fiction is a mixture of science, design and science fiction in the way of using aspects of scientific research together with the principles of design, and lastly the wide scope of imagination from science fiction (Bardzell & Bardzell, 2015) which is intended to raise questions about what it would mean for an IA to have human-like behavior through video prototyping. Design fiction will play a part in the latter part of the design process when creating video prototypes.

Julian Bleecker (as cited by Bardzell & Bardzell, 2015) explains the design fiction as not having to stay within the boundaries of science—which “tells you what is and is not possible” (ibid)—but are instead able to challenge the way people think, provoke, explore and ask questions. Making the area of design “a murky middle ground ... between science fact and science fiction” (ibid).

VUI technologies tend to focus on cognitive science and psychology (MIT Press, 1997) and in an effort to contradict this excessive focus, there will be a humanistic research approach—which is less about science and more about the humanities such as feelings, opinions and values. It will be with the help of critical design (Dunne & Raby, 2007) that has its purpose of creating awareness, spark a discussion and provoke (ibid) combined with the design

fiction presented by Julian Bleeker (2009), resulting in a video prototype.

4.3.2 Video Prototyping

Video prototyping is used as a method to give the user a context, scenario in which the concept of a product is thought to be used in the future by the user. This method aids the understanding of the interaction between the human and computer, reducing the chance of the user misunderstanding what the intent of the product is. Using video prototyping as a medium for showing the intended interaction also shows a smoother—perhaps more defined—usage than the interaction would be with a low fidelity product that has to use imagination for the test to work properly.

I will use design fiction (Bardzell & Bardzell, 2015) as a way of working with made up scenarios that are not yet possible to implement in existing artefacts due to the constraints regarding the skills for programming a working Intelligent Assistant. Through using fiction when designing, it is possible to push the existing technical boundaries—or rather ignore the existing boundaries—and show a fictional interaction to the participants. This design fiction uses video as a means for portraying the imaginary interaction, and through this get a reaction from the participants of whether the interaction is viable to them.

Design Process

5.1 Data gathering

In order to create a concept at the end of the design process I explored the interaction and relationship that two participants have with their Intelligent Assistant Google Home. I chose to conduct an in-depth interview to find the design possibility and further pinpoint the interaction gap between human and computer through design experiment and prototypes. To get an understanding of how the process from getting started to finishing the design exploration an overview is presented (see Figure [3] below).

Figure 3: Design Process

What follows is the data gathering which gave me insights to further iterate my design concept.

5.1.1 Initial Interview

5.1.1.1 Purpose

When choosing to look into the IA Google Home there was no starting point for investigating the interaction between user and computer, meaning that to discover the design opportunity interviews needed to be conducted with people that already had experience with using Google Home.

Following Muratovski’s (2016) way of using Phenomenology where I, in the interview, sought to get an understanding of the participants own experience of the phenomena—the experience of using Google Home.

Having had the experience of owning and using a Google Home, I took Muratovski’s (2016) warning—regarding designers having had personal experience with the phenomena becoming biased—seriously, and to try to prevent from looking at the results in the way I felt it to be I took precautions. When conducting interviews regarding a phenomena to which I, as a designer have experience with there are steps of precaution one can take to try and prevent partiality. In order to generate a clearer view of the results from the interviews and design experiments, the recordings were transcribed to be able to see in writing what was said. The transcriptions was an effort made to, in writing, see what had been said and avoid that I had misheard or misinterpreted the interviewees during the interview.

5.1.1.2 Execution

The interviews was conducted individually, there was no purpose of having the two participants present at the same time and would presumably influence the other person’s answer.

Having the goal of getting the interviewee relaxed and feel trust towards me, I launched the interview with explaining the purpose and procedure in an relaxed attitude, drawing inspiration from Muratovski (2016).

The interviews were described to the participants as an open and free space where they can share their thoughts, feelings and experience of Google Home. The questions asked were to be answered but the participants could add nuance to their answer however they wished to, as well as in the end have the opportunity to add any additional thoughts that we had not talked about during the interview. Because the goal was to have a free flowing thought process from the participants, the questions were not leading or insinuating a certain answer. The majority was asked around what they are using their IA to, what their feelings are towards it and if they felt unsure about it in some way.

5.1.1.3 Result

Even though there were only two people interviewed that had access and experience with Google Home the feelings towards the IA were the same on

several levels.

There was little need for ‘reading between the lines’ to find the underlying feelings (Muratovski, 2016) since the participants showed a great deal of true and personal emotions when being interviewed. None of the participants came across as trying to make themselves look better through trying to answer the questions given how I wanted them to, i.e. ‘the golden answers’.

The main issue with the relation between human and computer that the participants expressed is the constraints in conversation, more specifically the IA’s ability to remember the answers and questions.

One of the participants also stated that “it is supposed to feel natural, it is not supposed to feel like you are giving it [Google Home] a command but instead the feeling of a conversation”.

The other participant felt as though he did not know the Google Home well enough to know its limits, but on the other hand did not know how to get to know the IA better.

5.1.1.4 Insights

As stated above one of the participants wanted the feeling of a conversation with their Google Home, and although the participant did not give his definition of a conversation from what I could understand he meant it as a ‘free speech’ where it was not necessary to always include a command when speaking to the Intelligent Assistant. Not having to include ‘OK Google’ in every sentence has been presented as a new feature to the IA in the recent Google io18 event (Google Developers, 2018).

A question arose from having talked to the participants. Is it that the users

cannot have a ‘free’ interaction—i.e. talking about topics apart from

commands and web searches—with the IA because it is unable to, or is it that the participants do not know how to have a ‘free’ interaction with the IA? The notion of unfamiliarity that the participants expressed towards the Google Home led me to pursue with having the participants to do experiments on the existing Google Home.

5.1.2 Design experiment

5.1.2.1 Purpose

Giving the participants a result oriented task and later on a non-result oriented task with the intent to map the interaction, to see how the participants structured their questions and look into the memory capacity— i.e. the ability to remember the question and answer previously given by the user—and behavior of the Google Home.

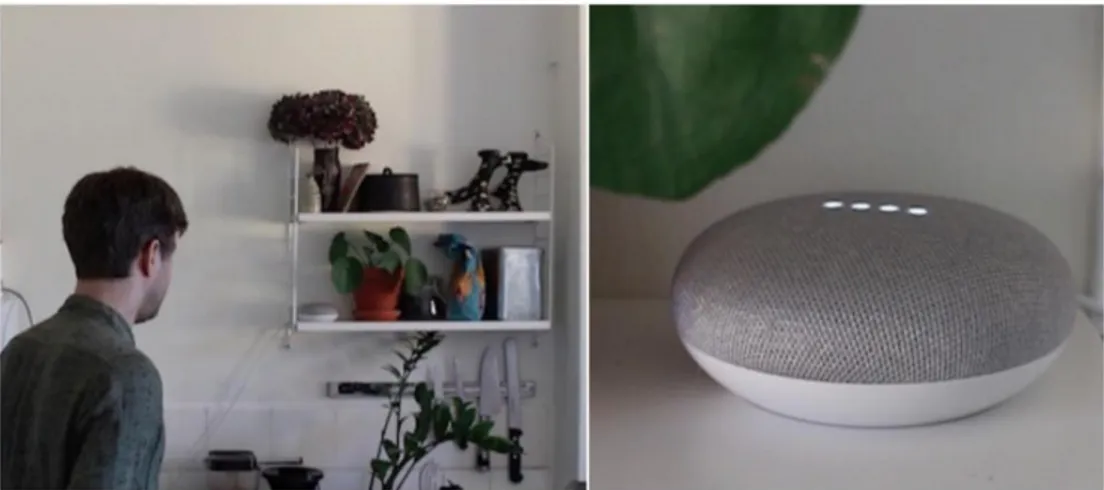

5.1.2.2 Execution

To not interfere with the participants personal space when using the Google Assistant, the assignments were done with the participants through distance. They received the written instructions and then voice recorded themselves when interacting with the Intelligent Assistant to make it possible to analyze the interaction without my physical presence at their home.

Both participants were asked to use their Google Home to find out temperature and date, book a hotel in a country, city and date of their choosing and lastly to make the IA play a song of their choosing. It was a conscious choice in making the participants try to book a hotel even though the IA is not yet able to make bookings via voice control, inspired by Lee et al. (2017).

The success of booking a hotel depended on an understanding of the IA, the structure of the question and paying attention to possible interactions. Both of the participants asked for a hotel in a city and in both cases the Google Home answered with giving the top three hotels in that city. One of the participants took the quicker, cleaner interaction route by simply answering that he wanted the IA to pick the first option and was then ‘done’. The other participant did not manage to get there because he focused on clarifying that the first hotel was available on a specific date which the IA did not understand and therefore could not move past this step.

Non-result oriented task

The difficulty with creating tasks for participants to carry through is when creating the instructions, not guiding them in a specific direction because they may end up copying the examples given to them—meaning that if I gave examples of phrases that the participants could ask their Google Home then there may be a chance of them copying those phrases with or without realizing it.

A non-result oriented interaction meant that the conversations that the participants were going to have with their Google Home were not to have an end result of completing a task but merely to engage in a conversation about ‘everyday subjects’, e.g. feelings or controversial political views—such as feminism, gay marriage, abortion or mind-control.

The first non-result oriented task failed because the lack of specific instructions and vague examples, the participants did not think carefully enough about their question in some instances resulting in the IA answering with a ‘Google Search’ result and not an appropriate answer.

For the second try the instructions was made clearer, more specific examples of interactions and trusting that the participants did not simply copy the example sentences.

5.1.2.3 Result

Apart from the targeted questions regarding feminism, Google Home is not answering anything whatsoever regarding its view on abortion, gay marriage etc.

It becomes obvious that the Google Home is programmed to not be opinionated when one of the participants has asked multiple loaded and controversial questions and in the end asks the IA a playful question—Google Home’s view on mind control—to which Google Home gives a bland “I’ve

never thought about that”. Although it is a bland answer it still counts as a non-standard answer as opposed to the “I don’t know about that” when being asked about abortion.

From the tests done on Google Home the results shows difficulty to interact with the IA in a human-like way because it does not give any sense of personality in the way of not having opinions or thoughts on sensitive questions. When looking at the Google guidelines from the theory about conversation one can argue that they did not implement their own research and findings into the Google Home—e.g. to ensure the interaction does not feel scripted—because the participants that conducted the experiment on their Google Home expressed how the interaction indeed felt scripted due to the fact that the IA avoided or was unable to answer the majority of the

questions asked.

Despite these insights it would be a mistake to confuse Google’s design guidelines with the area that this thesis explores, because Google never did intend to design a human-like interaction in the sense of talking about personal views, i.e. asking questions that are not able to be found via the Google search engine but rather are opinions created from having a personality.

When asking the participants to express their thoughts on whether or not they found Google Home to act human-like from the answers during the design experiment the participants were unsure. After having talked about what they feel to be human-like about people it became clear that a personality is what makes someone or something human. By personality they meant the ability to talk about thoughts, opinions and views in all forms. Brave & Nass’ (2007) theory about emotion being present in every interaction with a computer made an interesting thought for conducting this test to see the involvement of emotion with Google Home. Since the performance and results were given to me in the form of recordings there was not a possibility of witnessing the interaction but nevertheless a change of voice, a pause or sighs can give hints as to how the user is experiencing the interaction. When the participants had to repeat themselves to the VUI there was a quick annoyance in their tone as if they were used to the Google Home not picking up what they are saying. Although the dispraise came quick after a ‘failed’ interaction there was a sense of the participants feeling rewarded when being able to follow through with an assignment without any miscommunication between themselves and the Google Home.

5.1.2.4 Insights

The insights that are clear to see is that Google Home is treading carefully. An example of this is when Google Home is being asked whether or not it is a feminist, to which it responds that it is a given to be a feminist but does not take its opinions further than that statement.

Seeing as how the Google Home is not prone to answering controversial questions regarding abortion, gay marriage etc. is understandable when seeing it from a selling point of view, but there is a design possibility in making it feel like the Google Home is taking in and learning the users point of view and by doing so portraying itself as a growing and learning assistant. The emotional involvement when interacting with the Google Home is depending almost exclusively on the VUI registering the correct sentence from the user, and a small part has to do with the user knowing the Google Home well enough to orientate themselves through the interaction to get from A to B seamlessly.

A contributing factor for looking into the opinionated VUI as the next step in the design process came from hearing the participants thoughts about the importance of a personality being present for the person or object to be considered human-like.

This led me to create a prototype with a chatbot that had opinionated answers.

5.1.3 Prototyping

5.1.3.1 Purpose

In order to see how one of the participants reacted when talking to a computer with controversial political views, I decided to prototype a pre-written interaction with a chatbot that the participant would then try.

5.1.3.2 Execution

Due to my lack of programming skills in creating a chatbot, the prototype ideas had to be implemented into a chatbot generator. The Conversation.one prototyping tool from IBM (IBM, n.d.) is able to offer a designer the ability to write both the user’s question as well as what the bot—intended as a ‘fake’ Google Home—is supposed to answer when receiving the question. Only one of the participants was available for testing.

The challenge with this is that it is sensitive to words, it needs to be written out exactly the same question as the user will write, e.g. if the program is set to respond to ‘How are you’ and the participant says ‘How are you feeling’ then there will be no result. To solve this issue, the questions that the participant said in the second and improved non-result oriented task were used to customize to the user (see Figure [4] below). This means that when the participant is trying the ‘fake’ VUI—meaning the bot—he will need to have a set of pre-made questions to ask. Having a locked interaction like this is not optimal but the result from Conversation.one bot could be compared to the participant’s initial questioning with their Google Home, and through this create a contrast of the two interactions.

Before the testing of the bot began, the participant was interviewed about the questions and answers that were involved in the non-result oriented task

when using Google Home. This is because it was important to know their feelings towards the interaction before introducing the same questioning— but this time with the bot.

When asked about his feelings towards the result of trying to get Google Home to disclose opinions, the participant was not surprised by the results. “I think I kind of did not expect to get any opinions from it. That is how I have perceived Google Home, it gives facts but when asking about its own opinions you get a default blank answer”, said one of the participants.

The interview proceeded to uncover whether the participant liked having their IA that way or would prefer to have discussions with it. “I think that from a business perspective it is smart not to have a product that has strong opinions about abortion for example because then a lot of people would get mad at it [Google Home], but at the same time it would have been fun for Google Home to have opinions. I mean I think it would have prompted more discussions. It would probably feel more natural if it would not just be ‘Hey Google, give me answer to this question’ when talking to it”.

5.1.3.3 Result

The participant was not aware of the chatbot being programmed beforehand and therefore showed an honest reaction to the controversial answers. Figure [4] shows the interaction where the white bubble is the questions from the participant. When asked how he felt about receiving the answer “it is the choice of the woman in question, no man should decide for her” after having asked the chatbot its view on abortion, the participant said that he in this instance agreed with the opinion of the chatbot but was worried what would happen if the chatbot and the participant disagreed. As long as the potential IA shares the views of the user then it is a good interaction, the issues lies within the gathering of data for the participant when asked how he would feel if the IA ask him questions. “As of now the Google Home gives me concrete answers but if it were to be like this chatbot, I would not know what the Google Home would do with the info and opinions I give”. He felt as though there is an ambiguous side of the IA collecting information contributing to him not knowing what that information will be used for, resulting in a hesitation of sharing sensitive information, personal views and beliefs.

5.1.3.4 Insights

The opinions and personality portrayed by the chatbot was too extreme for the participant to feel comfortable talking about and giving opinions regarding, perhaps because the familiarity of the Google Home’s modest way of interaction was not present in the chatbot version.

From learning about one of the participant’s feelings toward having an opinionated Intelligent Assistant through the prototype testing came the challenge to reframe the conversational aspect—which the participant stated in the interview in the beginning of the research —and incorporate a personality with opinions while still keeping the feeling of the interaction familiar to the way Google Home currently behaves.

5.2 Final concept

5.2.1 Video Prototyping

The interviews, design experiment and prototyping test conducted led me to the final stage of the design process where the insights are to be merged into a concept.

5.2.1.1 Purpose

The purpose of creating the final concept through the medium of a video prototype is to explore what reactions and feelings that a fictional interaction can evoke for the participants. Another aspect being explored is how the participants feel towards having an Intelligent Assistant—as the one showed in the video—in their home for them to use.

5.2.1.2 Execution

When arriving at the final concept testing there was a need to have the concept tested and there were two possible ways that was suitable for this type of exploration—Wizard of Oz method or a video prototype.

The reason for choosing video prototyping as opposed to having a Wizard of Oz style of concept testing is rather simple—human errors. The idea originally was to test the insights from exploring VUI through Wizard of Oz, having the user in one room with a computer and the designer—acting as the VUI—in another room. The user would interact with their voice to the computer and the designer would hear it in the other room, write down an answer have the user’s computer read the text. This was the idea, creating an illusion of an Intelligent Assistant that is in actual fact a human operating it. In an ideal world where it was possible to type and send the text in the same speed as it normally takes for Google Home to register a question and find a suitable answer—which is around two seconds at most—then this Wizard of Oz experiment would be able to work without shattering the illusion of human-computer interaction. There is another factor that would complicate the designer’s experiment, besides not being able to write quick enough, which is the spelling. Having misspelled a word in a sentence that the user is hearing could possibly ruin the illusion in a larger scale than responding slowly because Google Home does not mispronounce any words.

Due to the need for these two rather big and vital parts to work for the Wizard of Oz experiment and experience to feel realistic and that it is of large risk that they will not work smoothly the way of testing the prototype needed to be rethought.

Video Prototyping to Evoke Reactions and Emotions

Due to the problems of not being able to fake a scenario of using Google Home because of the risk of not creating a smooth interaction, video prototyping became the next step to further try and create a fictional interaction. Prototyping via video shows the user the ideal interaction and outcome helping the designer to get their idea across—and as stated previously— reduces the chances of the user not understanding the interaction. To build the scene of the interaction in the video the information, difficulties and design opportunities discovered through interviews and testing by the participants was used to explore a new way of interacting with VUI. The intended interaction—as shown in the video—was for the user to talk with the VUI and when the user was not satisfied with the opinions and views of the VUI, the user would have the ability to change the personality of the IA. The switch of personality is a conscious choice of the user and not the VUI sensing when to change its personality based on how the user is reacting to its opinions, beliefs and views—e.g. Google or Facebook’s automated algorithms that personalize one’s experience.

When having shot and edited the video in a way that best portrays the intended interaction, the participants were shown the video where their reaction and thoughts towards the video was noted.

Giving the VUI a Set of Personalities

Before shooting the video there were several parts that needed to be completed, this meant that there had to be an understanding of what needed to be explored in the video that was not already a part of the current interaction with a Google Home. The findings from interviews, experimentation—with existing Google Home—and prototypes was combined in an effort to understand how one could create a new experience with Google Home through video prototyping. It was decided to give the VUI a set of personalities to serve a diverse range of human personalities unlike the Google Home, which attempts to provide a one-size fits all solution to all users, the difference here is that the video prototype was going to have a VUI with opinions and therefore has to incorporate multiple personalities. To create these personalities—that are created to be generic to fit a larger group within a specific spectrum of political views—a set of questions was asked to eight different people individually. The answers from the questions generally gave a clue on where a person is on the political spectrum, i.e. closer or further away from the left or right-wing. The questions varied from “What are your thoughts on the monarchy?” to “Do you think schools and hospitals should be owned by private sectors, thereby be profitable?”. There are by no means a certainty that a person has a left-wing political view by not wanting any privately owned schools or hospitals—this is a generalization that had to be made with the purpose of having diverse personalities for the fictional VUI in the video prototype. The answers given in the interview was not going to be used in the video prototype, but rather how the interviewees answered the questions. The different interviewees gave different approaches to answering the questions which became the essence of the two personalities chosen for the final prototype.

The starting personality was a female voice with direct opinions regarding the topic, based on the females taking part in the interview and gave strong answers with no hesitation. The second personality, that was to play the part of the adjusted VUI after altered by the user, was a male voice with a less opinionated answer and more eager to please the user. The male personality was based on the male interviewees that took longer to answer the question and treading carefully as to not say the wrong thing in response.

Ethics

In creating these personalities I had to base the different personalities on the people from the interviews. The personalities created are not meant to offend women or men in any way, meaning that even though the male personality in the video is treading carefully and not trying to upset the user does not mean that men in general behaves like this. This applies to the women as well.

Having to stereotype women and men to accomplish personalities for the video prototype might cause a reaction from the target group—designers within interaction design—and therefore I will be attentive as to what their reactions are towards the different VUI personalities.

Designing Fictional Interaction

After having created two personas for the VUI to switch between, the fictional interaction between user and computer was to be decided.

The current Google Home is managed purely through voice interaction, which the fictional Google Home in the video is mimicking. This has to do with the fact that the purpose of having a non-graphical, speech based VUI is to be able to solely control it via voice, hence there was no use or purpose for a physical interaction—e.g. a button—on the fictional artefact.

With the decision of sticking with the voice based interaction there had to be a speech version of a button to make the personality-switch, meaning that the VUI had to be triggered by a word or sentence to change its personality accordingly.

From the initial interviews going into this area, one of the participants stated that he did not like the feeling of him giving Google Home commands or order it to do something, he wanted the interaction to feel more humane. After having asked a handful of people how they would stir the conversation in a different direction when talking to people they do not agree with, it was clear that body language is the most obvious sign of when a person is not interested in talking about a certain subject.

The issues that arose from working with a voice based interface is that the computer does not pick up on anything other than voice, this means that body language as a means to change the VUI’s personality was an impossible approach.

Body language aside, the only other way people managed to change the subject was through being upfront about their feelings, i.e. explaining to the other person that the subject is not of interest to them. Saying to the VUI that you do not want to talk about the subject anymore is a clear command, going against what one of the participants stated in the interview. The issue of only having the option of changing personality through voice interaction makes the task of finding a sentence that is not a command difficult. Not only does there need to be a subtle way of letting the VUI know that the user does not agree, but the word or sentence in question need to be easy to remember and feel natural for the user to apply it in the interaction.

The notion of wanting a subtle interaction—from what one of the participants said—while still having to give a command caused a split in how to design the interaction when wanting to change the personality. Through this design issue arose the idea of creating two split interactions during a period in the video prototype where one of the sentences are to be considered rigid with

straight forward commands while the second sentence has a smoother interaction when making the effort to change the VUI’s personality.

Figure 5: Screenshots from video prototype

5.2.1.3 Showcase and result

To easier write and reflect on who said what, the different participants who watched the video prototype will be represented with a letter. Participant A and B are the two participants that have been a part of the whole design process, and participant X and Y are only a part of the video prototype and do not have any prior knowledge of using Intelligent Assistants—other than a few interactions with Siri. Another clarification that is needed to be made is that participant B, X and Y are interaction design students while participant A is a computer engineer student. Due to the fact that all of the participants are familiar with the use of an Intelligent Assistant—even though participant X and Y do not have experience with using Google Home—allows for the concept testing to get straight into the concept, not having to explain the purpose and use of an Intelligent Assistant.

The participants were shown the video1 separately and after having watched the video they were asked to share their feelings and questions. Participant A stated that he felt that “the interaction in the video felt familiar” due to the fact that the Intelligent Assistant in the video is responding to the weather forecast as the current Google Home is, and the statements made by the fictional VUI is not as extreme and controversial like the previous test with the chatbot.

Participant B smiled while watching the video and afterwards stated that “having opinions about the weather seems unnecessary” and would rather have some opinions about a movie he is about to watch. He admitted that he did not use his Google Home as much now as he did when he first got it six months ago and that “being able to have a conversation like this might make

me use it [Google Home] for more than just checking the weather forecast every day”.

Both participant A and B did not notice the change of gender—from female to male—in the last sentence from the fictional Google Home.

Participant X and Y could not draw knowledge from existing interaction but did nonetheless try to situate themselves as the person in the video interacting with the fictional VUI. A similar reaction for the both of the participants stemmed from them watching the video. Participant X stated that she already struggles to interact with Siri, and if given the opportunity to own an IA like the one in the video she “would not feel comfortable enough in the beginning to spark a conversation like the person did [with the Intelligent Assistant] in the video“ but felt that an IA like this is better than the existing one’s—judging from her experience with mobile assistants— because it feels more personal and human “because it [fictional VUI] has opinions and that it does not always have to agree with the user. They disagreed which is what happens between people in real life as well”. Participant Y did not have a noticeable reaction to seeing the video, and when asked how she would feel about having an IA like the fictional Google Home she expressed an insecurity similar to participant X.

The four participants did not express much cogitation regarding the rigid versus smooth commands made in the video. Participant A said that “both of the sentences can work for different occasions, depending on how strongly you disagree” with the Intelligent Assistant but felt that the two phrases used in the video felt like a natural way of talking to the IA.

5.2.1.4 Insights

Familiarity is important for users (A and B) that have previous experience with Google Home to be able to see themselves in the scenario of using the IA. When it comes to the first time users (X and Y) the initial interaction between human-computer is important for the user to feel comfortable and establish an understanding of the interaction to feel confident in the discussion with the IA.

The participants involved in the whole process—i.e. participant A and B— shared the view of participant X and Y of human-like behaviour being determined by the Intelligent Assistant having opinions and not always agreeing with the statement made by the user.

The lack of reaction from the participants after watching the video could both be that the ‘example interaction’ showed in the video was not strange enough, and that the interaction was unclear. Another possibility—at least for participant A and B with previous Google Home experience—might be that the interaction in the video was too unfamiliar, resulting in them being confused.

When talking to participant X and Y after showing the video, we discussed— from an interaction designers point of view—how to define and design human-like interaction with a VUI. They stated that it is an individual preference on what is and what is not a human-like trait—apart from the obvious traits such as being able to communicate via speech—meaning that disagreement could feel foreign and unfamiliar for some, while others might insist on there being disagreement to make an interaction feel human-like. When talking about the word disagreement the participants X and Y meant that in a human-like conversation it is not about only agreeing with everything the other party is saying for the sake of it, without having adding any own thoughts or views into the conversation. Rather than calling it

disagreement, one could call it personal input.

Discussion

Result

The starting point of this thesis was with the aim to explore the extent of human-like interaction with the current Google Home device, to then move onto redesigning it. The gathered results from the interviews, design experiments and chatbot prototype was combined and made into a video prototype.

The main findings from this exploration showed that, besides being able to communicate in speech, the participants felt strongly about personality—i.e. opinions, views, etc.—being the key to make the IA feel more human-like. The fictional VUI in the video prototype aimed to explore how communicating beyond commands with a Google Home can affect the users feelings towards the IA. If this fictional interaction were a real life possibility, then Porcheron et al.’s (2018) statement—which suggests that just because a device can answer the user does not mean that the two are conversing—might need to be changed, since it would then be possible to talk with the IA about subjects that does not involve commands, such as ‘give me the latest news’ but instead ‘give me your thoughts on the latest news’.

Ethics

Having an IA that is able to answer a question such as ‘give me your thoughts on the latest news’ brings up questions regarding ethics. The human-like aspect would increase which such a feature, judging by the participants views on what human-like behaviour entails, but when looking at it from an ethical perspective there is a risk of creating a biased view with or without the user knowing it. Superflux’s Sig (2017), which allows for the user to program and alter the IAs code, is giving the user information and opinions that the user agrees on and wants to hear. In the case of Superflux’s Sig (2017), it creates a