CULTURE-LANGUAGES-MEDIA

Independent Project with Specialization in English

Studies and Education

15 credits, First Cycle

The Effect of Gender on English as L2

Learning Motivation

Påverkan av genus på inlärningsmotivation för engelska som andraspråk

NannaLinnea Bergman

Emma Svensson

Master of Arts in Secondary Education, 270 credits English Studies and Education

2021-01-17

Examiner: Henry King Supervisor: Jasmin Salih

2

Abstract

The aim of this study is to expound on the gender discrepancy that is present in the English subject in the Swedish school, where female students generally and consistently attain higher grades. We do so by investigating any gender differences in motivation to learn a second language (L2). Further, we apply a gender perspective as we research the motivating effect of incidental English as L2 learning through out-of-school activities, known as extramural English (EE) activities. The study provides a summary of five articles that examine the effect that gender has on motivation and four articles that explore how exposure to and use of EE act as a motivator for male and female students separately. The articles show that female students in general are more motivated to learn an L2. Moreover, a possible explanation for this gender difference is different self-constructs and societal expectations. These findings are relevant to the Swedish educational context since the curriculum for the compulsory school states that all teaching should be equivalent, meaning that all students’ different needs and prerequisites should be taken into account. This includes variations in motivation. On the matter of EE activities, there is a stronger connection between time spent on EE hobbies and school performance for male students, especially for those who play digital games with a

communicative aspect; this may offer a solution for the aforementioned gender discrepancy in grades. Nevertheless, there needs to be further research on how to bring the benefits from EE activities into the English classroom.

3

Individual contributions

We hereby certify that all parts of this essay reflect the equal participation of both signatories below:

The parts we refer to are as follows:

• Planning

• Research question selection

• Article searches and decisions pertaining to the outline of the essay • Presentation of findings, discussion, and conclusion

Authenticated by:

NannaLinnea Bergman Emma Svensson

4

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 5

2. Aim and Research Questions ... 8

3. Method ... 9

3.1 Search Delimitations ... 9

3.2 Inclusion Criteria ... 10

3.3 Exclusion Criteria ... 10

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria ... 10

4. Results ... 11

4.1 Gender differences in English as L2 learning motivation ... 11

4.2 Extramural English, L2 learning motivation, and gender ... 14

5. Discussion ... 18

6. Conclusion ... 23

5

1. Introduction

Researchers have long observed a gender gap in second language (L2) learning, where female students in general do better in their L2 studies than their male counterparts (Kissau, 2006). In a Swedish context, this problem takes the form of higher grades for girls on the national tests in English, as well as in the final grades at the end of year nine (Skolverket, 2020). The same type of gender-related difference in final grades is evident in all other language subjects in the Swedish school: Swedish, Swedish as an L2, L3, and mother-tongue tuition (Skolverket, 2020). Henry and Cliffordson (2013) point out that the gender gap in L2 grades is not just typical for Sweden but rather a general phenomenon that has been observed in L2 learners

internationally. Moreover, the gender gap is not only present in results but also in L2 learning motivation. Csizér and Dörnyei (2005) have looked at several different aspects of what

motivates students to learn a second language, like attitudes toward the native speakers of the target language and whether they think it will be useful in a future professional career, and found that females are more motivated in almost all aspects. Other studies (Dörnyei, 2009; Henry, 2010) have analysed what effect motivation has on language acquisition and whether the gender gap in L2 learning can be explained by gender-related variations in motivation. We will investigate the gender gap in L2 learning motivation to find in what way motivation differs between male and female learners of English. Specifically, we will analyse why girls have

stronger motivation to learn an L2 and whether that could be a reason why girls perform better than boys in the subject of English as L2 in Swedish secondary schools.

L2 motivation is also a question of equality in education. In 2011, Skolverket released a new national curriculum for the compulsory school, where it explicitly stated that everyone working within the Swedish school is required to commit to “equivalent education” (Skolverket, 2019a, p. 10). This means that whichever differences students show in terms of prerequisites and individual needs, the school must account for them when planning their teaching. For example, factors that affect students’ access to, and choice of, extramural English (EE)

activities, such as socioeconomic status or gender, could limit their opportunities to learn. This is a challenge for teachers that requires them to exhibit an understanding of different

prerequisites and needs and to understand how to make up for varying levels of interest and access to EE activities, which has proven to be valuable from an English learning perspective.

6

There are ways to counteract these inequalities: for example, a vast majority of Swedish schools provide their students with either a computer or a tablet. With guidance from their teachers, more students could learn how to responsibly use them in ways that promote L2 learning in their spare time.

Even though the gender gap in L2 learning is present in Swedish schools, there are studies (Sundqvist, 2009, and Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012, among others) that show that one male group can perform on par with, or in some cases better than, their female classmates in the subject of English in Sweden. That group includes boys who spend a lot of time outside of the classroom on activities that expose them to the English language through EE. The activities include both passive exposure, such as watching television or listening to music, and active communication, such as video games with chat functions. Since being able to relate learning to personal

interests increases the motivation to learn, EE activities outside of school can bring positive results for students in school. However, research shows that there are gender differences when it comes to what EE hobbies are preferred and that hobbies vary in the extent to which they impact L2 learning (Sundqvist, 2009). Accordingly, there is reason to further investigate the connection between L2 motivation and EE exposure from a gender perspective.

Therefore, our second focus in this paper will be how EE activities motivate L2 learning differently between male and female learners.

In a historical context, students’ opportunities to access EE outside of school have increased since the 1990s as technology has advanced. In a national evaluation of the Swedish

compulsory school, the results for English were presented in the report Nationella utvärderingen av grundskolan 2003: Engelska (NU-03), and they showed a significant difference between above-average and below-above-average students (Oscarson & Apelgren, 2005). NU-03 showed that most of the above-average students claimed that they spoke an equal amount or more of English outside of school, whilst below-average students claimed the opposite (Oscarson & Apelgren, 2005). Additionally, in the report Engelska i åtta europeiska länder – en undersökning av ungdomars kunskaper och uppfattningar, where students’ English knowledge was tested, the countries that reported the highest amount of EE (Sweden and Norway) also had the highest test-scores, whereas the countries reporting the lowest amount of EE tested the lowest (Skolverket, 2004). This strengthens the need to investigate the relation between EE exposure and L2 learning motivation.

7

From a learning theory standpoint, Turuk (2008) suggests that lack of motivation sometimes found in L2 learners could be due to an over-emphasis on teaching language structure and too little time spent in the classroom on activities where theoretical knowledge can be put to use in situations related to the students’ interests. Therefore, using EE activities that the students are already interested in as a learning tool could be a method that increases motivation. Further, Henry and Cliffordson (2013) claim that males generally are less motivated to learn a second or third language than females; thus, it is more urgent to find means to engage and motivate male learners. One way of doing this is by applying the sociocultural theory of learning, which goes well with EE learning motivation. The sociocultural theory of learning describes how learning takes place through social interactions and how students are motivated by learning from each other (Ushioda, 2012, p. 81). Ushioda (2012) describes how cognitive functions that are internalised through social interactions make up a central idea in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (p. 81), and Turuk (2008) ties this idea into the L2 classroom by emphasising the importance of meaningful tasks that allow the students to be creative and “assimilate learning activities into their personal world” (p. 256). The social-interactive aspect is inherent in some EE activities, making them useful to improve and motivate learning. An example of one such EE activity that is also popular with male students is digital gaming: video games that are played online with others provide a social environment that promotes language learning in line with sociocultural learning theory.

We have discussed the gender gap in English as L2 learning in Sweden and presented how it may connect to motivation. We will further investigate this issue because it is central in the Swedish compulsory school that all students receive equal opportunities to learn. We will go on to research how extramural English exposure motivates L2 learning and whether there are ways to balance out the gender differences in L2 learning motivation.

8

2. Aim and Research Questions

This paper aims to investigate the extent of gender’s effect on motivation, specifically in learning English as L2 for secondary school students in Sweden. To investigate this issue, this paper will explore the aspect of motivation and how motivation matters in language

acquisition. We will investigate how the nuances of the relation between motivation and language acquisition can explain the gender gap in L2 English in Sweden.

The second aim of this paper is to map the beneficial effects of extramural English (EE) on English as L2, specifically how gender affects what EE activities are pursued and how this in turn affects the motivation to learn English as L2. This latter focus can perhaps pose a solution to the gender gap if taken into consideration by English teachers in Swedish secondary

schools: motivating students by including their interests in the classroom. Therefore, our research questions are as follows:

• To what extent does gender affect the motivation to learn English as L2 among Swedish secondary school students?

• In what way do extramural English activities motivate L2 English learning differently between male and female students?

9

3. Method

For our research, we have collected multiple articles and studies that examine the effect that gender has on motivation and, in turn, on language acquisition, as well as how extramural English acts as a motivator for male and female students. Our primary method has been to use educational databases to find electronic sources, where our key terms limited the results. In addition, we have also chain searched to expand our search by looking at footnotes and references from various electronic articles.

3.1 Search Delimitations

Our searches for empirical studies and research articles were performed on databases accessed through the Malmö University Library database. ERIC, ERC and Swepub were the main databases used, but we have also accessed some research articles by using other articles’ references as a chain search to find other relevant articles.

When using the databases, we limited our results to studies and articles that have been peer reviewed. We also limited our date range to 2010–2020; we wanted to use up-to-date articles to stay technologically relevant, as extramural activities is an area which has evolved greatly along with technology over a short period of time. We also wanted to focus on research relevant for current classroom situations and environments. However, we have included a few older articles and studies as a foundation for our background research.

In our searches, we have used the following terms in different combinations: Gender, L2, L2 motivation, gender differences, gender gap, extramural English, incidental learning, motivation, language learning, language acquisition, L2 acquisition.

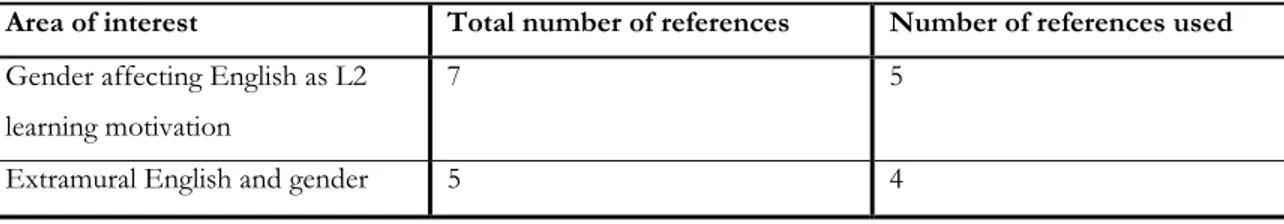

In total, we found twelve articles befitting our research, and after applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria described below, we were left with nine articles all featured in this paper’s result section.

10

3.2 Inclusion Criteria

We decided to include articles where research was performed on students below and above our intended age group, keeping in mind that the results still could be applicable on secondary school students. We also decided to include studies where the research focused on English as L3 because we found it to be applicable in a Swedish context, where many students speak another language instead of or alongside Swedish at home. This also includes studies mentioning English as a Foreign Language (EFL), as it is often used interchangeably with English as L2 and L3. Finally, we decided to include studies performed worldwide.

3.3 Exclusion Criteria

We chose to exclude several articles performed on primary school students and younger. EE activities differ greatly between younger children and our target age group and are therefore not significant to our research.

A summary of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Area of interest Total number of references Number of references used

Gender affecting English as L2 learning motivation

7 5

11

4. Results

In this section, we will present the results of our research, starting with five studies that connect gender-related differences in L2 learning with variations in motivation. Thereafter, we will present four studies on the topic of EE activities and L2 learning, with focus on the motivational aspect and any gender differences that have been observed.

4.1 Gender differences in English as L2 learning

motivation

Several studies address the effect that motivation has on L2 English learning and how gender in turn affects motivation. For example, Henry and Cliffordson (2013) claim that there is a gap in results as well as in motivation between female and male learners of L2 and L3 that partially can be explained by differences in self-construct. In their study “Motivation, Gender, and Possible Selves”, Henry and Cliffordson (2013) asked 271 native Swedish speakers in year nine to answer questionnaires about how they visualised themselves using their L2 and L3 in varying future scenarios. Apart from being more willing to learn a third language, females generally visualised situations involving interpersonal interaction in the target language more than males. Henry and Cliffordson (2013) conclude that this affects language-learning motivation. This was particularly clear in L3 learner groups but less frequent in the L2 ones. The authors present two reasons for this: first, young Swedish people increasingly use English in their lives outside of school, and second, equality has come a long way in Sweden; both genders visualise their future selves similarly.

In a similar study, You and Dörnyei (2016) research what motivates Chinese learners of English in secondary school and university. Over 10,000 students answered a questionnaire, and their answers were then divided into subgroups according to parameters such as

educational strand, gender, and geographical location. The questionnaire was constructed in line with the “L2 Motivational Self System” (L2MSS, You and Dörnyei, 2016, p. 497) to map how different demographic groups are motivated to learn a second language in school through self-construct, how they portray themselves using English in the future, and why. The results show a significant difference between genders, where females in the secondary school age

12

group scored higher in the “ideal-self” motivation category while the males appeared to be more motivated by their “ought-to self” (p. 497). This means that boys responded more strongly to outside pressure, such as parental expectations, whereas girls could visualise themselves in an English-speaking context in the future to a higher degree. The authors conclude that this correlates with the amount of intended effort that the students stated that they made in their studies, where the females again scored higher.

Furthermore, Lee and Pulido (2017) investigate what impact gender has on motivation and what impact this could have on L2 proficiency through reading. The study was conducted on 135 Korean EFL students, where the participants were exposed to both high- and low-interest topic passages with vocabulary post-tests, both immediately after and four weeks after reading. Results showed no significant gender difference in the L2 lexical development through reading. However, Lee and Pulido (2017) reveal that there was significant interaction between gender and topic interest, where females tested better on word recognition in lower-interest texts, indicating that female students are more motivated than male students to keep reading lower-interest texts. Finally, the authors argue that motivation plays a large role in incidental language learning and that maximising student motivation and engagement is crucial for language learning in a classroom setting.

In “The L2 Motivational Self System, L2 Interest, and L2 Anxiety: A Study of Motivation and Gender Differences in the Croatian Context”, Martinović and Sorić (2018) investigate gender differences in L2 motivation based on several L2 motivation factors, including L2 interest and L2 anxiety. From a sample of 204 male and 339 female students in Croatia, Martinović and Sorić (2018) apply the L2MSS approach to L2 motivation research, an approach largely building upon the concept of possible selves and self-discrepancy theory. The study was conducted through a two-part questionnaire analysed both descriptively and through a t-test of different variables. Martinović and Sorić (2018) build upon instrumentality as an important element in L2 English learning motivation, the concept to visualise the utilitarian value of language learning. Furthermore, they divide instrumentality into two core concepts: “instrumentality-promotion” and “instrumentality-prevention” (p. 39). Almost all students who participated in the study showed a sense of instrumentality-promotion; they regarded English as L2 learning as instrumental to job promotion and future opportunities. In

13

where they regarded English as L2 learning to prevent them from failure and exhibited a facilitative type of anxiety and fear of failure to push avoidance of negative outcomes. The results indicated no difference in how the students visualised their L2 self; instead, they tied higher L2 motivation among female students to high rates of L2 anxiety. Finally, Martinović and Sorić (2018) note that while their study complies with other studies showing differences among genders in L2 motivation, the results may be culture specific, and they call for more qualitative and cross-cultural research to better explain the differences.

Lastly, in “Age, Gender, Attitudes and Motivation as Predictors of Willingness to Listen in L2”, Akdemir (2019) sets out to investigate whether gender, amongst other factors, has any effect on EFL learners’ Willingness to Listen (WTL) in L2, attitude and motivation. The quantitative study includes 239 participants of mixed gender, aged 18–33, who were tested through a set of instruments to determine their attitudes and motivations in L2 learning. Akdemir (2019) concludes that the test results show a significant variation between the male and the female participants regarding the speaker aspect of WTL, where females scored higher. The author suggests that the discrepancy lies in motivation by referring to previous studies and existing theories, among them the ideal-self theory by Dörnyei (2009).

Based on the above studies, female students often have an easier time visualising the use of English in their future, thus motivating them in their L2 or L3 acquisition. The findings in Henry and Cliffordson (2013), You and Dörnyei (2016), Lee and Pulido (2017), Martinović and Sorić (2018), and Akdemir (2019) all support the claim that there is a difference in motivation between genders with regards to visualisation. However, there is a difference in how this is portrayed between the studies. Martinović and Sorić (2018) build upon the L2MSS, which is also applied in You and Dörnyei (2016), and they expand the L2MSS-reasoning by including instrumentality-promotion and instrumentality-prevention. With this, Martinović and Sorić (2018) agree with You and Dörnyei (2016) that female students test higher with their “ideal self” but argue that the reason for this is strongly connected to instrumentality-prevention and the fear of failing as a motivator in English as L2 learning.

Furthermore, Lee and Pulido (2017) argue that the gender gap in English as L2 is not due to an inherent connection between motivation and results per se but a strong connection between motivation and engagement. They found that the more motivated a student was, the more likely

14

the student was to engage in the given material regardless of actual topic interest. This agrees with the conclusion reached by You and Dörnyei (2016) and supported by Akdemir (2019), where both articles stated that student effort directly correlated with how the students saw themselves using English. However, while You and Dörnyei’s (2016) study shows correlation between motivation and effort and between effort and results, this does not automatically show causality between motivation and results; other factors could come into play.

However, the discrepancy between different studies could be culturally tied. Martinović and Sorić (2018) argue that the inherent fear of failure in female students is tied to culture and could thus differ across cultures. This cultural discrepancy is further evident in You and Dörnyei’s (2016) research, where they note that Chinese boys are more susceptible to outside pressure. However, the cultural differences do not dispute the correlation between motivation and effort argued for in Lee and Pulido (2017) and You and Dörnyei (2016).

To conclude, the studies show what appears to be a gender-related difference in L2

motivation, where female students generally visualise their future self and their future use of English higher than male students. However, the results varied somewhat in different countries as gender-expectations intersect with cultural standards, and the reason as to why female students visualise themselves differently might be tied to cultural aspects.

4.2 Extramural English, L2 learning motivation, and

gender

Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) investigate whether there are gender differences in young L2 learners regarding their involvement in EE habits and how that connects to their L2

proficiency. Data was collected from 86 Swedish 11–12-year-olds through a questionnaire, a language diary, and three proficiency tests. The results showed that the boys spent more time on EE activities, especially on video games played online with others. The boys also scored higher on the vocabulary test, and the results showed a correlation between time spent on video games and vocabulary proficiency. Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) argue that the gender difference in results is due to what kind of games are played; they point out that boys in the

15

study preferred games that include online communication, whereas girls played offline games with limited opportunities for input/output.

Jensen (2017) expands on Sylvén and Sundqvists’ (2012) previous study by researching whether there are gender-related differences in how young English students in Denmark acquire language in relation to how much time they spend on EE activities. She highlights digital games with different language modes: for example, games that provide opportunities for output/input in oral or written English. Jensen (2017) used similar methods as the above-mentioned study by Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012), where 144 children aged eight and ten took vocabulary tests and filled out language diaries. The results showed that while boys and girls both listened to music and watched television shows in English, boys played almost five times as much video games as girls, and the most popular language mode in games was with both oral and written English input. In addition, the author notes that boys who play games scored higher than non-gaming boys on the vocabulary tests, but still on par with the girls. Jensen (2017) suggests that girls are not motivated by extramural activities to the same extent as boys. Sylvén (2010) investigates incidental vocabulary acquisition, specifically through Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). Comparing the results in two student groups (99 CLIL students and 264 control group students) over the span of two school years, Sylvén (2010) finds that exposure to English outside of the English L2 classroom improves students’ lexical development. However, Sylvén (2010) argues that although CLIL students outperformed the control group students, the highest scorers in both control groups had more features in common than the high CLIL scorers and the low CLIL scorers, specifically regarding their extramural exposure to English. Furthermore, the author argues the importance of attitude and motivation to vocabulary acquisition. The author finds some evidence of difference in results between genders, where male students outperform female students. Sylvén (2010) suggests that this difference in results is due to larger motivation among male students to expose themselves to English extramurally than among female students, such as playing video games, watching movies, and reading books.

Lastly, Sundqvist and Wikström (2015) aim to find and describe a connection between digital gameplay and L2 English grading outcomes. In addition, they investigate any gender

16

English as L2. Sundqvist and Wikström (2015) analyse the learners’ final grades in relation to a questionnaire, language diaries, vocabulary tests, and assessed essays and find that the group which frequently played digital games (all boys) scored the highest for all vocabulary measures. The group consisting of non-gamers (predominantly girls) had the highest final grades, while the group made up of moderate gamers (mixed genders) scored the lowest in most categories. The authors conclude that consistent gameplay correlates positively with L2 outcomes for boys, who seemed to be motivated by putting their language skills to use in a gaming context, but has no impact for girls, who seemingly find their motivation elsewhere.

On the question of whether EE activities have an impact on motivation in second language learning, Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012), Jensen (2017), Sylvén (2010), and Sundqvist and Wikström (2015) are all in agreement. Having opportunities to learn and use English in a context that the students have personal interest in motivates them to develop their language skills and thus perform better in school in terms of tests and grades. Jensen (2017) describes how the motivational factor in an activity of the students’ own choice that requires use of English is indisputable because it is engaged in purely for entertainment (p. 14). For example, an activity such as digital gameplay where in-game progress often is connected to the player’s ability to read instructions and communicate with co-players, improving in English becomes necessary to succeed in the game. In addition, Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) make the point that time spent on an out-of-school activity is indicative of its motivational impact (p. 308), and their study shows a positive correlation between large quantities of time spent on EE activities and school results. Furthermore, the motivating factor provided by hobbies seem to have a larger effect on male learners compared to female learners. For instance, Sundqvist and Wikström conclude that boys’ gameplay correlates with grading outcomes, but not girls’ (p. 74). However, in a majority of the studies (Jensen, 2017; Sundqvist & Wikström, 2015; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012), the female learners performed at least as well on tests as male learners, whether they were engaged in EE activities or not. These findings suggest that girls are motivated to learn English in different ways than boys.

Three out of four studies emphasise that video games in particular have an impact on L2 learning and motivation—namely, Sundqvist and Wikström (2015), Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012), and Jensen (2017)—which further points to a connection between gameplay and learning motivation. Further, it appears that the type of game correlates with the amount of

17

learning. Games that include online communication with other players, such as World of Warcraft, impact learning to a higher degree than offline, single-player games such as The Sims (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012) since improving their communication skills also improves gaming results. The need to communicate is thereby motivating to learn English for online gamers. In addition, Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) conclude that the time spent on gaming also matters: frequent gamers tested higher than moderate gamers in their test. Jensen (2017) reaches the same conclusion, and she offers an explanation: longer gameplay means that language input is often repeated (in the form of instructions, commands, etc.), and repetition is fundamental in language acquisition.

Playing digital games outside of school can thus have an impact on L2 learning motivation, but according to the studies included above, there is a significant difference between female and male students when it comes to game type preferences and time spent on gaming. Generally, boys play games that are of a more communicative nature, including games where the players interact both orally and in writing as part of the game, as well as with other players through a microphone or a chat function. In addition, they play for substantially longer periods of time as well as more often than girls (Jensen, 2017; Sylvén &Sundqvist, 2012). However, even though girls spent quite a lot of time on other activities involving the English language—such as watching television, listening to music, and engaging in social media—there does not seem to be as strong of a correlation between EE hobbies, L2 learning motivation, and English acquisition as the one found with boys.

18

5. Discussion

We have previously presented statistics that show how female Swedish students attain better test results and final grades at the end of year nine in the subject of English, as well as in all other language subjects (Skolverket, 2020). The results that we have found in the articles presented above support the idea that part of the gender gap can be explained by a discrepancy in motivation, where girls generally are motivated to learn an L2 to a higher extent than boys. Moreover, Henry and Cliffordson (2013) point out that the gender gap is present in L3 learning as well, which is relevant in the English education context in Sweden since we have a number of students who, due to immigration, have other first languages than Swedish.

Therefore, Swedish is a second language for these students and English becomes their third (or in some cases fourth or fifth) language. However, since the findings that suggest that there is a gender gap in L2 learning motivation also include L3 learning, they are relevant for the

heterogeneous Swedish classroom. Moreover, English is a compulsory subject in the Swedish school system, regardless if it is as a first, second or foreign language, and that makes findings in relation to English as a foreign language as relevant as English as L2 in our study.

On the question of how motivation affects L2 learning motivation differently between the genders, the findings in all five articles that investigate the subject (Akdemir, 2019; Henry & Cliffordson, 2013; Lee & Pulido, 2017; Martinović & Sorić, 2018; You and Dörnyei, 2016) agree that there is a difference in motivation that pertains to the visualisation of future selves. Henry (2010) suggests that a possible explanation for the difference in motivation between male and female students of an L2 lies in different “ideal-selves”. By applying

Dörnyei’s (2009) theory, “The L2 Motivational Self System”, which is also used by Martinović and Sorić (2018) and You and Dörnyei (2016), Henry (2010) has analysed what motivates students to learn a foreign language over the course of several studies, and he has come to the conclusion that the “ideal-self” differs between the genders. In brief, the ideal-self is a term coined by Dörnyei (2009) that describes how persons see themselves in an ideal future scenario. Henry (2010) claims that when students of English as a second or foreign language are asked to describe how they envision themselves using English in the future, females in general answer that they will have interpersonal interactions to a much higher extent than males. In other words, being able to have future relationships, personal and professional,

19

carried out in English seems to be a strong motivating factor for girls. He connects this to the common societal expectation that is often placed upon girls and women, namely that they are expected to focus on a “social and communal centering” (p. 6) and thereby have a desire to develop and maintain relations with others. On the other hand, boys are described by Henry (2010) to be associated more with traits like independence and autonomy, and are thereby less motivated to learn how to communicate in an L2. This discrepancy in ideal-selves, shaped by social expectations, might explain at least part of the gender gap in L2 motivation that in turn might be part of why there is a gender gap in the English subject in Swedish secondary schools.

Additionally, there is a cultural aspect that needs to be taken into consideration. Several of the presented studies claim that males in general had lower L2 motivation, some arguing that this could be culturally tied. For example, Chinese male students (You & Dörnyei, 2016) and Croatian female students (Martinović & Sorić, 2018) exhibited the same sensitivity to outside pressure, L2 anxiety, and “ought-to-self”, yet the female students in each study still scored higher on the language tests than their male counterparts. Another type of cultural impact was found in Sweden, where Swedish students presented a smaller gender-gap in English results as well as in English learning motivation compared to the other countries included in the studies. Henry (2010) claims that since gender equality has come a long way in Sweden, the “ideal-selves'' imagined by both genders are quite similar. However, he did admit that the study was performed on a group of homogenous, monocultural students with similar socioeconomic backgrounds. Had the composition of students been different with a wider cultural variation, the results could have been closer to those in other countries where the gap in motivation was bigger.

The findings that suggest that girls and boys are motivated by different “ideal-selves” when learning an L2 are relevant when considering the concept of equivalent education, presented in Skolverket’s national curriculum for the compulsory school (Skolverket, 2019a). The

curriculum states that the school and its teachers must account for individual prerequisites and needs when planning their teaching. Since Martinović and Sorić (2018) argue that there are cultural structures within L2 motivation where female students often feel more stress and anxiety regarding L2 learning, and Akdemir (2019) makes the case that male students are generally feeling a lower motivation to participate, it is vital for teachers to be able to

20

understand how to make up for these discrepancies. It is also important for teachers to understand the different impacts that the students’ cultural backgrounds may have on their motivation and to plan their education with this in mind.

Given the importance for teachers to understand how to make up for gender-motivated discrepancies in L2 motivation, a possible solution to this would perhaps be to look into what motivates students outside of the classroom. The presented research above supports the claim that EE has a beneficial effect on L2 English motivation (Jensen, 2017; Sylvén, 2010).

Furthermore, Oscarson & Apelgren’s (2005) report NU-03 attest to the effect of EE on English as L2 results, where above average students claim more use of EE compared to below average students. According to Skolverket’s report Engelska i åtta länder (2004), this is true on a larger scale as well, as countries reporting a higher amount of EE tested higher on students’ English knowledge compared to countries reporting a lower amount of EE. Sweden was among the countries both reporting a high use of EE and scoring high on students’ English knowledge (Skolverket, 2004).

If pursuing EE is a potential solution to mitigate the gender gap in English as L2 motivation, it is important to distinguish between gender differences in terms of the general effect of EE. Neither Oscarson and Apelgren (2005) nor Skolverket’s (2004) report attested to significant gender differences in terms of the effect of EE. However, there is a significant difference in the type of EE activities pursued by male and female students. Sundqvist (2009) and Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) present data showing that male students choose to engage in video games as their primary EE activity, generally five times as much as female students (Jensen, 2017). This is a significant difference, given that playing digital games is considered to be an effective way to learn a language (Thompson & von Gillern, 2020). However, when

investigating if there are any gender differences in L2 vocabulary learning using digital games, Benoit (2017) concluded that there are no significant differences in results; male and female learners can both learn from video games to the same extent. Despite this, boys tend to generally learn more from video games than girls, when it comes down to their own choice of extramural English activities (Jensen, 2017; Sundqvist & Wikström, 2015; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). The fact that girls are able to learn from video games to the same extent as boys, but choose not to, implies that it is a matter of interest and motivation rather than ability.

21

Being able to bring something that clearly is a motivational factor to male students into the English classroom could perhaps aid in mitigating the previously presented gender difference when it comes to motivation. Additionally, in the syllabus for secondary school English (Skolverket, 2019b), it is stated that students are to be given opportunities to put their education in relation to their own experiences and interests, and it is further stressed that English teaching shall stimulate the students’ interest in language and culture as well as convey the benefit of language skills (Skolverket, 2019b, authors’ translation). To achieve this, while not explicitly recommended, it would be helpful for teachers to have knowledge about different motivational factors affecting their students. Exhibiting an understanding of how to make up for lapses in interest and motivation between students and knowing how to cater to gender-related differences, as in cases where students choose different EE activities (Jensen, 2017; Sundqvist, 2009; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012), could be beneficial in increasing L2 motivation and student interest.

The sociocultural theory of learning, as explained by Ushioda (2012) and widely applied in Swedish teacher education, describes how learning takes place through social interactions, and how students are motivated by learning with, and from, their peers. In this paper, we have discussed video games as an EE activity. Online multiplayer video games provide a social environment where the interactive aspect is inherent, and as the student strives to make progress in the game and improve their gaming skills, they are motivated to interact and cooperate with other players by using English. As we have previously stated, young boys are more inclined to spend their free time on video games than girls, therefore male learners of English as L2 benefit more from the motivation that digital games provide in the form of social learning. However, as pointed out by Richards and Burns (2012, p. 5), if a classroom is functioning as an effective learning community, learners can motivate each other and benefit from each other’s knowledge. Thereby, the boys who have learned English from playing video games can aid their non-gaming classmates, on the condition that their teacher designs learning opportunities that allows the students to learn from each other in line with the sociocultural theory of learning.

Finally, adding the above claims that male students generally are less motivated to learn a second language (Henry & Cliffordson, 2013) to Turuk’s (2008) argument on lack of L2 motivation being due to teachers over-emphasising language structure and in turn neglecting

22

the application of theoretical knowledge to the interest of the students, we argue that teachers who exhibit the ability to weave in students’ interests into their education in a meaningful way would have a higher chance of motivating all students on their own terms. For example, teachers could suggest games to play, at home or during spare time in school, that include English input/output based on the students’ interests, in a similar way to how books are traditionally recommended.

23

6. Conclusion

The aim of our research was to investigate the effect, if any, that gender has on L2 learning motivation. We found that male students are generally less motivated to learn a second or third language compared to female students, which may explain the higher grades for girls on the national tests in English, as well as in the final grades at the end of year nine. One reason behind the difference in motivation, as suggested by several studies (Akdemir, 2019; Henry & Cliffordson, 2013; Lee & Pulido, 2017; Martinović & Sorić, 2018; You & Dörnyei, 2016), is the difference in how males and females visualise themselves using English in the future: females have a stronger desire to be able to communicate in a second or foreign language and, thereby, stronger motivation.

Additionally, there is a cultural connection in how students visualise their future selves and their use of English. It is important for teachers to be aware of this connection, and plan their education with that in mind. This goes in line with what Skolverket (2019a) calls “equivalent education” and ensures that every student is given the best education in regards to their individual prerequisites. This cultural connection could be the topic of future research since this paper is limited in its ability to do just that. Since many students in Sweden are not mono-cultural, further research could be conducted to see in what way gender and culture collaborate to affect English as L2 motivation.

Furthermore, we wanted to investigate any differences in how male and female L2 learners benefit from exposure to English outside of the classroom, namely through extramural English activities, and how it might affect motivation differently between male and female learners. We found that although both groups spent time on a variety of activities, boys played digital games to a much higher extent. In addition, boys who spend a lot of time playing games do better in the English subject in school than boys who play a little or nothing, while girls seem to be performing better than boys regardless of how much (or rather little) they play. From this we conclude that the use of video games as a motivational tool could be used to minimize the L2 gender gap in Sweden. However, how to implement this in Swedish L2 classrooms needs to be further researched.

24

This study has two major limitations: the lack of consideration for cultural aspects as described above and a wide age-span among the participants of all the articles that were analysed. Ideally, we would have investigated 12–16-year-olds only, but we were unable to find enough relevant research performed on that age group.

Finally, there are many different cultures present in Swedish schools today, and our VFU schools are no exceptions. In the future we would therefore like to investigate how gender roles within different cultural backgrounds impact English learning motivation. This research could shine a light upon how to navigate cultural individual differences in a heterogenous classroom and thereby aid in our strive towards equivalent education.

25

References

Akdemir, A. S. (2019). Age, Gender, Attitudes and Motivation as Predictors of Willingness to Listen in L2. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 10(4), 72–79

Benoit, J. M. (2017). The Effect of Game-based Learning on Vocabulary Acquisition for Middle School English Language Learners (Doctoral dissertation, Liberty University).

Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Language Learners’ Motivational Profiles and Their Motivated Learning Behavior. Language Learning, 55(4), 613–659.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0023-8333.2005.00319.x

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 Motivational Self System. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Henry, A. (2010). Gender differences in L2 motivation: A reassessment. In S. A. Davies (Ed.),

Gender gap: Causes, experiences and effects (pp. 81–101). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Henry, A., & Cliffordson, C. (2013). Motivation, Gender, and Possible Selves. Language Learning, 63(2), 271–295. https://doi-org.proxy.mau.se/10.1111/lang.12009 Jensen, S. H. (2017). Gaming as an English Language Learning Resource among Young

Children in Denmark. CALICO Journal, 34(1), 1–19.

Kissau, S. (2006). Gender Differences in Second Language Motivation: An Investigation of Micro- and Macro-Level Influences. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics / Revue Canadienne de Linguistique Appliquee, 9(1), 73–96.

Lee, S., & Pulido, D. (2017). The Impact of Topic Interest, L2 Proficiency, and Gender on EFL Incidental Vocabulary Acquisition through Reading. Language Teaching Research, 21(1), 118–135.

Martinović, A., & Sorić, I. (2018). The L2 Motivational Self System, L2 Interest, and L2 Anxiety: A Study of Motivation and Gender Differences in the Croatian Context. ExELL (Explorations in English Language and Linguistics), 6(1), 37–56.

https://doi.org/10.2478/exell-2019-0005

Oscarson, M., & Apelgren, B. M. (2005). Nationella Utvärderingen av Grundskolan 2003 (NU-03). Engelska. Ämnesrapport till Rapport 251. Stockholm: Skolverket

Richards, J. C. & Burns, A. (2012). Pedagogy and Practice in Second Language Teaching: An Overview of the Issues. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge Guide to

26

Pedagogy and Practice in Second Language Teaching (pp. 77-85). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skolverket. (2017). Kommentarmaterial till Kursplanen i engelska. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3858

Skolverket (2019a). Läroplan (Lgr11) för Grundskolan samt för Förskoleklassen och Fritidshemmet. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/grundskolan/laroplan-och- kursplaner-for-grundskolan/laroplan-lgr11-for-grundskolan-samt-for-forskoleklassen-och-fritidshemmet

Skolverket (2019b). Kursplan - Engelska för Grundskolan. Retrieved from

https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/grundskolan/laroplan-och-kursplaner-for-

grundskolan/laroplan-lgr11-for-grundskolan-samt-for-forskoleklassen-och-fritidshemmet?url=1530314731%2Fcompulsorycw%2Fjsp%2Fsubject.htm%3Fsubject Code%3DGRGRENG01%26tos%3Dgr&sv.url=12.5dfee44715d35a5cdfa219f Skolverket. (2020). Slutbetyg i Grundskolan Våren 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from

https://siris.skolverket.se/siris/sitevision_doc.getFile?p_id=549948

Skolverket (2004). Engelska i Åtta Europeiska Länder: En Undersökning av Ungdomars Kunskaper och Uppfattningar (Rapport 242). Stockholm: Skolverket

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English Matters : Out-of-School English and Its Impact on Swedish Ninth Graders’ Oral Proficiency and Vocabulary (PhD dissertation). Karlstad University, Karlstad. Retrieved from

http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kau:diva-4880

Sundqvist, P., & Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school Digital Gameplay and In-school L2 English Vocabulary Outcomes. System, 51, 65–76.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.04.001

Sylvén, L. K. (2010). Teaching in English or English teaching? : on the Effects of Content and Language Integrated Learning on Swedish Learners’ Incidental Vocabulary Acquisition. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Sylvén, L., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as Extramural English L2 Learning and L2 Proficiency among Young Learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302-321.

27

Thompson, C. G., & von Gillern, S. (2020). Video-game based Instruction for Vocabulary Acquisition with English Language Learners: A Bayesian Meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 30. https://doi-org.proxy.mau.se/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100332 Turuk, M. C. (2008). The Relevance and Implications of Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory in

the Second Language Classroom. Arecls, 5(1), 244-262.

Ushioda, E. (2012). Motivation. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge Guide to Pedagogy and Practice in Second Language Teaching (pp. 77-85). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.