Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rred20

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rred20

Trial with academic elite programmes in the

comprehensive upper-secondary education in

Sweden: a case study

Glen Helmstad & Marie Jedemark

To cite this article: Glen Helmstad & Marie Jedemark (2020): Trial with academic elite

programmes in the comprehensive upper-secondary education in Sweden: a case study, Research Papers in Education, DOI: 10.1080/02671522.2020.1789717

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1789717

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Published online: 10 Jul 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 515

View related articles

Trial with academic elite programmes in the comprehensive

upper-secondary education in Sweden: a case study

Glen Helmstad a and Marie Jedemark b

aDepartment of Educational Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; bDepartment of School Development

and Leadership, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

ABSTRACT

Sweden has a long tradition of comprehensive upper-secondary edu-cation. This began in the early 1970s. It culminated in 1994 with all the programmes having a core curriculum that gave general eligibility to higher education. Conservative and liberal governments have intro-duced several neoliberal school reforms, which the subsequent social democratic government has done little or nothing to change. In 2009, the government initiated a trial with academic elite programmes. The aim of this article is to analyse how and why the elite programmes translated into and transformed local school practices as they did. The study builds on interview and questionnaire data from school princi-pals, university teachers, upper-secondary teachers and students involved in the programmes that started in 2010, and questionnaire and interview data from students that graduated from the pro-grammes that started in 2009. The results show that propro-grammes failed to recruit the target group, that relatively few students used the opportunity to specialise, and that the new programmes replaced previously developed local systems for support of the academically most able. The schools used the trial to strengthening their brand. The study confirms the need for ongoing development of the academic quality of the general upper-secondary education programmes.

ARTICLE HISTORY Received 26 February 2020 Accepted 26 June 2020 KEYWORDS Upper-secondary education; general programmes; academic ability; curriculum differentiation; curriculum implementation

Introduction

The comprehensive education model was developed during the twentieth century and implemented in different ways in different countries (Castejón and Zancajo 2015; Moe; Wiborg 2017, 2009a). In Sweden, the concept of ‘a school for all’ has implied that all students should be taught the same curriculum in mixed ability groups, regardless of gender, socioeconomic class, ability or interests (Blossing and Söderström 2014; Haug, Egelund, and Persson 2006; Marklund 1989; Skott 2009; SOU 1974; Wiborg 2009b). This political vision of a common core curriculum for all remains a fundamental principle within the Swedish school system (Blossing and Söderström 2014; Skott 2009). It entails that teachers should provide adequate instruction for all students. It applies not only to students who need extra support but also to students with special talents in a certain area who will need extra challenges if they are to be fully stimulated to develop their ability

CONTACT Marie Jedemark marie.jedemark@mau.se Department of School Development and Leadership, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any med-ium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

and interests. Some critics have argued that this system has focused on the provision of support for students who are at risk of not reaching the minimum standard, while the academically most able students have been abandoned to their own devices (SOU 2008).

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Swedish government implemented a series of reforms aimed at getting away from the problems with the centralised education system and creating a more effective, performance-based education system. Amongst other things, higher efficiency was to be achieved through greater flexibility and more alternatives for families and students to choose different schools; moreover, programmes were expected to promote academic achievement (Moe 2017). In 2009, the conservative- liberal government lead by Reinfeldt initiated a trial of specially designed general upper- secondary programmes for the academically most able students. It was seen as an attempt to offer greater freedom of choice to these students (Ministry of Education 2008b). The change also permeates the new school law from 2010, which states that students with special talents should be given leadership and the incentive to excel in their learning (Education Act 2010, Chapter 3, Paragraph 2).

When it comes to the academically most able students and the concept of talent, there has been a shift from seeing talent as something innate in some individuals to something largely learned and changing, and as something which requires significant encourage-ment and effort to develop (Ziegler et al. 2013). In this context, the focus is on talent- creating education rather than on gifted children and adolescents, and on creating talent rather than on discovering gifted children and adolescents (Balchin, Hymer, and Metthews 2009). The students’ efforts and active approach, and the teacher’s competence, commitment and high expectations of the students have proven to be of great impor-tance. However, it is unclear whether motivation and willingness to exert themselves are a consequence of students being successful or whether they are a prerequisite for students’ success. High-performing students are thus characterised by both cognitive and non-cognitive competencies such as, for example, confidence in their own ability, motivation and endurance. Moreover, as high-performance results are highly dependent on specific learning experiences and a great deal of practice, both considerable effort and endurance are required from students (Balchin, Hymer, and Matthews 2009).

In discussions on how to support high-achieving students, three different strategies have emerged: acceleration, enrichment and levelling. Acceleration aims to make the students go through the education at a faster pace. Enrichment means that students can access other materials and teaching content to broaden and deepen their understanding (Cambell, Muijs, Neelands, Robinson, Eyre, and Hewston 2007; Fischer and Müller

2014). Level classification aims at dividing students into different groups depending on their performance. Reporting on the effects of acceleration, enrichment and levelling, Hattie (2009) argues that enrichment does not produce as positive results as acceleration. Enrichment gives most results in mathematics and the natural sciences but has a low impact on social science subjects. Level grouping can have positive effects if students are able to access specific content that challenges at an appropriate level.

This article explores how the idea of specially designed academic programmes for most able students was translated into practice, how the programmes transformed local school practices and why this happened the way it did.

The development of comprehensive education in Sweden

From the 1950s until the early 1990s, several social democratic governments initiated reforms to expand and integrate a comprehensive school system in Sweden. The concept of equal education emerged as a means of achieving increased equality between different social groups through equal access to education with a common curriculum for all (Lindensjö and Lundgren 2014; Marklund 1989; Wiborg 2004, 2017). This led to the establishment of a nine-year comprehensive compulsory education system intended to provide equal educational opportunities for all children and young people, regardless of ability, parental income and place of residence. A key question was how far through the age grades should the mixed ability groups be kept intact. The solution was to be the application of pedagogical differentiation within mixed ability groups (Lindensjö and Lundgren 2014; Marklund 1989; Richardson 1983; Skott 2009).

The introduction of the nine-year comprehensive compulsory school led to similar reforms within the upper-secondary education in the 1970s. The aim was to offer expanded provision of upper-secondary education (Gymnasieskolan) in a way that would satisfy both the demands of a broad-based modern democracy and the demands of the emerging post-industrial economy (Lundahl, Erixon Arreman, Lundström, and Rönnberg 2010). Differentiation between students would be based on broad programmes with a common core curriculum designed to provide all students with general eligibility for higher education, but with opportunities for individual specialisation for students if desired (Lundahl et al. 2010).

In the 1980s, the focus in the school debate shifted to a greater emphasis on the individuality of each student. Equal education should no longer mean uniform education; instead, it should focus on the students’ interests through increased individualisation of the educational content. The reformulation of the concept of equal education can be seen as arising from a loss of faith in the ability to establish in advance which skills and abilities students need and are able to develop, without limiting their individuality and distinctive character (Englund and Quennerstedt 2008). Equality began to be seen as everyone’s right to maximum development according to their needs, thereby allowing everyone to make educational choices based on their own individuality. Seen from this perspective, students have the capacity to choose, plan and evaluate their own education process according to their own interests and needs. Consequently, the education system has to be flexible and offer opportunities for choice (Francia 2011; Wiborg 2010).

During the 1990s and early 2000s, Sweden, like many other Western countries, imple-mented many reforms intended to strengthen the quality and effectiveness of secondary and upper-secondary education (Blossing, Imsen, and Moos 2014; Moe; Wiborg 2017, 2010). The reform of upper-secondary education towards a more comprehensive model culminated in the 1994 school reform (Ministry of Education 1994). All upper-secondary programmes were three years long and had a common core curriculum designed to provide all students with general eligibility for higher education. The reforms are a consequence of both the structural transformation of the economy and of the transformation of primary and secondary educa-tion, which made upper-secondary education accessible to greater numbers of young people (Lindblad, Lundahl, Lindgren, and Zackari 2002). Despite only nine years of schooling being compulsory, the three-year upper-secondary education has become the minimum require-ment for the transition from school to work. In practice, the expanded optional upper-

secondary education system indirectly transformed into an extended ‘education for all’ (Waldow 2008, 161).

To ensure the quality of the upper-secondary education, the social democratic min-ority government appointed a parliamentary committee for the purpose of proposing a new structure for upper-secondary education. Four years later, the social democratic government presented a bill that proposed only minor changes in the vocational pro-grammes. In 2006, the conservative majority coalition government under Reinfeldt withdrew the decision. In 2007, it appointed a new Upper-Secondary Education Commission to consider the structure and quality of the education in order to ensure efficiency (Ministry of Education 2007). This was strongly supported by The National Union of Teachers in Sweden, which is a part of SACO (Swedish Confederation of Professional Associations).1 In March 2008, the Commission proposed a division of the upper-secondary education into academic and vocational programmes; this was eventually implemented in 2011.2

Trial of upper-secondary education for the academically most able

In addition to the above-mentioned proposal, the Commission’s report also proposed to create specially designed general programmes for the academically most able students. It assessed that extending the model of ‘elite education’ – already contained within elite sport and arts education – to various academic disciplines would lead to ‘greater motivation for those students who desire and are able to reach further during their time in upper- secondary school’ (SOU 2008, 530; our translation). The Commission proposed that the Government should initiate a trial with specially designed upper-secondary general educa-tion programmes in a variety of academic areas (SOU 2008, 530).3 The programmes should be open to students nationally (so-called nationwide recruitment) and provide them with the opportunity to pursue studies at the university level and to acquire university credits, while still within the framework of upper-secondary education.

Subsequently, the Government in the same vein went further. The same year, it instructed the Swedish National Agency for Education to introduce a trial with nationwide recruitment for specially designed general upper-secondary programmes in mathematics, the natural sciences, the social sciences and the humanities, effective from the autumn of 2009 (Government bill 2008/2009, 19). The motivation of the trial reads as follows:

The Swedish school system ought to be able to offer students with special talents in some area an education that sufficiently challenges them to develop optimally in relation to capacity and ability as well as interest. This should normally take place within the framework of regular courses through individualized instruction. In some cases, it may be in the student’s best interest to provide an education designed to develop the student’s special abilities. (SOU 2008, 2; our translation)

The Ordinance stipulated that the National Agency for Education should:

● approve participation of a maximum of 20 programmes;

● ensure an even distribution across the country;

● ensure an even distribution of programmes between, on the one hand, mathematics and the natural sciences and, on the other, the social sciences and the humanities;

● ensure a maximum of 30 students in each class; and ensure that each of the participat-ing schools had established a partnership with a university able to offer courses in the topic or subject of the students’ programmes (Ministry of Education 2008a).

Through the development of specially designed general programmes, the Ministry of Education provided academically able students the opportunity to choose to develop their abilities and to enable society to satisfy the need for enhancement of skills by better utilising students’ abilities and interests.

A school system that is organised in distinct programmes or classes based on the ability and motivation of students demonstrates a form of curriculum differentiation that stands in contrast to the vision of equal education for all in mixed ability groups. Curriculum differentiation means that different knowledge is available for different groups of students (Oakes, Gamoran, and Page 1992). According to Gamoran et al. (1995), curriculum differentiation is an organisational response to the diversity of ability existing among the students. Such organisational differentiation is not the same as ability grouping within the classroom or pedagogical differentiation, which is the most common form of differentiation (Slavin 1987). The outcome of these reforms was a loosening of the concept of comprehensive education with a common core curriculum for all. It led to a questioning of the sustainability of the comprehensive education model in an era of market management and increasing differentiation between various types of upper- secondary school programmes.

Programmes are designed both to satisfy the individual’s right to development and to generate increased efficiency through individual choice. The Swedish initiative is in line with the suggestion by Musset (2012): that curriculum differentiation has become a tool for the management of demand for efficiency as well as for the increased achievement of goals. Curriculum differentiation has also become a tool for the management of market mechan-isms through voucher systems and school choice (Musset 2012). Lundahl et al. (2013) show that competition between schools has affected both staff and students and how this has contributed to the development of new programmes. Moreover, they also point out that there was less of a contribution to improved student performance and well-being. Theoretical framing

In the above account of the development of a relatively comprehensive upper- secondary education in Sweden, we have noted that since the early 1990s there have been several reforms aimed at quality improvement through a system of school choice and educational vouchers. The trial of specially designed upper-secondary general educational programmes for the academically most able students adds to the selection of choices. In addition to the choice of school and programme, the trial makes it possible to choose a more specialised curriculum. This might be interpreted either as an innovation within or as a departure from the concept of a comprehensive upper- secondary education with broad general programmes in different areas, but with common core curriculum for all. To determine this, we need more knowledge of how the idea of the specially designed programmes translates into practice and how the programmes transform local school practices. First, we should frame this subject theoretically.

We have chosen a research-oriented approach inspired by activity theory (Chaiklin and Lave 1993; Engeström 2001). Engeström (ibid.) sets out five principles for activity theory studies:

(1) Participants’ actions can only be understood in relation to the activity as a whole. (2) An activity system is always a community of multiple points of views, partly

because the participants represent different approaches, traditions and interests. (3) Activities are characterised by their history, which is built into artefacts, rules and

conventions. Parts of other former activities are usually contained in the devel-opment of the activity, and it can therefore only be understood in relation to its own local history.

(4) Contradictions play a central role as sources of change and development. New ingredients often lead to contradictions within the activity, when the new ingre-dient comes into conflict with other parts of the activity. This leads to a change in the activity.

(5) New activities may arise as a result of deepened contradictions within an activity, which cause individuals to start to question and deviate from established norms. This, in turn, may lead to the perception that the activity is aimed at something partially different compared to earlier assumptions, and as a result, brand-new activities might develop.

Purpose

A fundamental assumption of the study is that the work of schools and teachers is not easily managed through national decisions and steering documents. It is possible to reach an understanding of how the participants use the specially designed programmes on the basis of how they perceive the purpose of the programmes. This, in turn, has a significant effect on how the programmes are realised in the local school context, although locally developed traditions also influence how the teaching is conducted and becomes part of school activities.

The purpose of the study is to examine how the trial of specially designed general upper- secondary programmes translated into practice, i.e., how the implementation of the programmes proceeded and how the programmes transformed local school practices. In connection to this, we aim at answering the following three research questions:

(1) How did the idea of specially designed general upper-secondary education pro-grammes for the academically most able translate into local school practices? (2) How did the specially designed programmes transform local school practices? (3) Why were the elite programmes shaped as they were, and why did they change the

local school practices the way they did?

Method

The research addresses the trial introduction of a differentiated curriculum in an upper- secondary school system based on the idea of a school for all with a common core curriculum. This meant investigating how those who participated in the trial – in this

case, school principals, school and university teachers and school students – interpreted and participated in the trial in relation to what they saw as the overall purpose of the activity.

Research design

The trial continues through different programmes in different subject areas in different local school contexts and in collaboration with different universities and departments. To capture such complexity, we have chosen a case study design for our research (Merriam

1988; Yin 2018). A case study design involves a careful examination of one or several instances of a phenomenon. Case studies are typically characterised by depth rather than by breadth, particularity rather than generality, holism rather than atomism, natural rather than experimental settings, and reliance on several sources rather than on one single method.

In this study, the ‘case’ is the trial of differentiated curricula in upper-secondary education, and we have examined how the trial was carried out in different programmes in different local school settings. The study consists of two parts. The first deals with all programmes that started in 2010, i.e., eleven programmes. Of the eleven programmes, ten were placed in municipal schools and one placed in a private school. We visited each programme for one full day. We interviewed principals in charge of the programmes, as well as teachers and students engaged in the programmes (Helmstad and Jedemark

2013a). Additional data came from the programme students through a questionnaire. We also interviewed university teachers teaching the programmes. The second part of the study deals with the nine programmes that started in 2009. Here, we gathered ques-tionnaire and interview data from students who had completed their education a little over a year earlier (Helmstad and Jedemark 2013b).

Participants

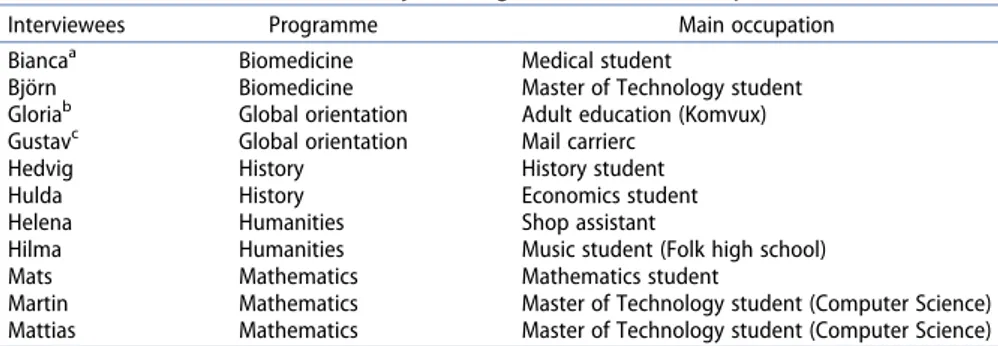

In the first part of the study – the eleven programmes starting in 2010 – the following were interviewed: one school principal at each participating school, with exception to one school where we also interviewed an assistant principal (a total of 12); group interviews with teachers involved in each programme (two to five teachers at each programme, a total of 45); 21 group interviews with students (a total of 93 interviewees); and 129 student questionnaire respondents and 11 university teachers who were closely involved with the design and management of these programmes. In total, the empirical material consists of 23 interviews and 32 group interviews, with 138 participants and 129 student responses from a total of 167 questionnaires (See Appendix Table 1 for an overview).

The second part, addressing the nine programmes that started in 2009, involved a total of 60 former students. In connection with the student questionnaire, the respondents were asked if they were willing to participate in a subsequent telephone/web-interview, which 31 respondents agreed to. These were subsequently contacted via email, to which about a third responded within a couple of days. Of these, the eleven first respondents were interviewed. The response rate for the questionnaire was 43%. The sample of graduates represents five of the nine programmes (See Appendix Tables 2 and 3 for an overview).

Procedures

In this section, we first present the approach to data collection. Then, the analytical approach is presented. Finally, a reflection is made on the quality of these procedures.

For the first of the empirical studies, we asked the programme study directors to plan our visit and organise the following: interviews with one or two school principals, a group interview with teachers, a questionnaire distributed to students in the third and final year of the programme, and two group interviews with students in the second and third years. of the programmes. School principals and teachers were asked, during the interview, to name collaborating university teachers. The latter were interviewed by telephone. The length of each interview was 45 to 75 minutes.

To achieve a nuanced and solidly based account, general overarching questions were addressed to both principals and to teachers. These questions concerned the school and its students, reasons for participation in the trials, the scale and organisation of the operation, selection and admission, quality of education, accomplishment and skills development, collaboration with universities, and attitudes and future plans.

The group interviews with students included questions about how they were briefed on the specially designed general upper-secondary programme, their reasons for apply-ing, selection and admission procedures, experiences of the upper-secondary education and study environment, experiences associated with university studies during the pro-gramme, and their evaluation of the quality of the programme. The additional ques-tionnaire involved questions on the extent of specialisation, results, future plans, and their experiences of both instruction and outcomes.

Interviews with collaborating university teachers focused on the emergence and development of the collaboration, organisation and regulation of the collaboration, and their thoughts on the difficulties of recruiting sufficient numbers of the target group.

For the second part of the study, we sent out an invitation letter, which included a link to a web-based questionnaire, to all former students. The questionnaire included ques-tions about their assessment of the usefulness of the programme and their current occupation at the time of the questionnaire. There was also an opportunity for respon-dents commit to a subsequent follow-up telephone interview, lasting 15 to 35 minutes. The questionnaire data came from both multiple-choice and open-ended questions. All interviews were audio-recorded using digital equipment. Interview recordings were played back and simple interview protocols were established. Sequences that seemed appropriate were replayed and transcribed into verbatim quotations.

The two mentioned sub-studies, together with descriptive statistics from the National Agency for Education, gave us a comprehensive descriptive material. In the analysis of this material, we began by reviewing how school leaders and teachers at the individual schools interpreted the regulation and chose to set up their programmes. We also went through how the university teachers and students perceived the programmes. We then compared and identified similarities and differences between the individual schools’ ways of interpreting and implementing their programmes in relation to the regulation text. This provided the answer to our first research question.

In a subsequent reflection on the type of schools that participated in the project and how they motivated their participation, it was found that most of the schools, long before the trial started, had drawn attention to the target group and established a collaboration

with universities. This actualised the second research question, namely how the programmes changed the local school practice. In the light of the raised question, we conducted a new round of analysis of the same empirical material. In this analytical step, we explicitly searched for utterances in which the participants reflected on how the elite programme worked in relation to the school’s previous work with the target group.

In the first two stages of the analysis, we sought answers on how the participants themselves describe the local trial and how they account for the consequences of the trial in relation to the previously established practice. In the third stage, we sought from an activity theoretical perspective an explanation to why the programmes were designed as they were and why they changed the local school practices the way they did.

The study suffers, to some extent, from our lack of control over the composition of the interview groups. Consequently, we cannot be sure that the whole scale of experience, understanding and judgement within the different groups of participants is covered. Another weakness is that we have no data from those students who had dropped out of the programmes. On the other hand, the number of participants is relatively large, all programmes are included, and the data collection involved different groups of partici-pants and methods.

In summary, the analysis of the empirical material has been done step by step based on the three research questions. In the first step, we have been close to the empirical material. Our answer to the first question is descriptive and well anchored in the empirical material. In the second step, with guidance from our reflection on what emerged through the first description, we have tried to understand the schools’ motives for participating in the experimental activities with the programmes with which they participated. We then found that a large part of the participating schools already had a tradition of supporting the target group. Our answer to the second question is both descriptive and interpretative. This finding led to the need for a theory that could help us deepen our understanding of why the programmes got the design they were given and why they changed the local school practice as they changed them. The choice fell on activity theory (Chaiklin and Lave 1993; Engeström 2001) that recognises the functional relationships between external and internal local conditions, the history of the activity and the inherent contradictions that drive the development of the activity system. This gave us a theoretical framework where local changes could be explained.

Results

The results are presented in terms of the following: (1) how the trial of a differentiated curriculum for the academically most able translates into practice; (2) how the trial transformed local school practice; and (3) why the elite programmes were shaped as they were, and why they changed local school practices the way they did.

How the trial of a differentiated curriculum translated into practice

The motivation behind the trial of specially designed general upper-secondary pro-grammes was the expressed need to provide ‘students with special talents in particular academic areas a sufficiently challenging education’ (Ministry of Education 2008b, 2). The official assumption was that students, as early as the final year of the nine years of

compulsory comprehensive schooling, have developed a keen interest and well- developed talent in specific subject areas. However, it proved difficult to fill the places on many of the specially designed programmes, despite the majority of the participating schools being located in metropolitan areas and information about the programmes made available at open days and on school websites. With few exceptions, the pro-grammes received low or very low numbers of applications. The total maximum number of available places was 1,800; but according to the National Agency for Education (2014), only 933 students participated in the trial as of April 2013. The dropout rate was also higher than for corresponding general national programmes.

Principals and teachers explained the low numbers of applicants by pointing out that the academically most able students tended to be strategic in their choice of upper- secondary school programmes, preferring programmes that provide them with oppor-tunities to gain maximum credits. To be able to specialise in particular areas, students on the specially designed programmes had to complete their normal courses at a faster pace than on the corresponding national programmes. This, however, did not gain them any extra merit points within the specially designed upper-secondary school programme, thus making it difficult for them to gain maximum credits.

Several of the participating schools reported that students on the specially designed programme had actually left compulsory school with, on average, considerably lower merit ratings than students on the corresponding national programmes:

Those who choose the specially designed programme should have the ability to absorb the teaching. The selection instruments do not work. All who apply to the programme are accepted because we do not have very many applicants. Some students really struggle. We need to raise the entry requirements. Those students who are exceptionally able see no point in studying a specially designed programme. They want top grades. They should get extra credits for choosing this programme. This would provide the programme with a totally different level of energy. (Teacher, science)

Because of the difficulty of attracting the academically most able to the programmes, just about every applicant was accepted, even though this meant that programmes based on acceleration and specialisation accepted students with inferior study skills. Consequently, students with higher academic ability expressed that a great deal of teaching time was devoted to students who needed extra support, and even that the pace of the programme had slowed down. Only half of the students of the 11 programmes that started in 2010 reported that they were able to advance as much as they had hoped to do and that they were challenged to use all their intellectual resources (Helmstad and Jedemark 2013a).

Principals and teachers maintained that the specially designed programmes should not be seen as elite education:

Our specialized programme is based on interest rather than on ability, providing the students with a community where they can feel that it’s okay to be interested in school and in social sciences. They have felt a little lonely before in their previous classes. Here, they get an opportunity to discuss. (Teacher, social sciences and humanities)

This teacher even challenged the idea of special talent:

They are talented because they are creative and aware of that they actually want to go to school, and they have a goal, a focus. But special talent? No. (Teacher, social sciences and humanities)

This interpretation of academic ability made enrolment of students with lower grades acceptable, and it may also be seen as an explanation as to why interviewed teachers emphasised that the most reasonable interpretation of academic ability is ‘student interest’.

Teachers on these programmes have high expectations of the students, which stimu-lates the students to increase effort and improve performance. In turn, the students’ efforts and performance encourage the teachers to improve their instruction. The teachers have to try a little harder, be a little better informed and up-to-date than what is usually required. Classes are small so all students can be heard and seen, which creates a favourable environment in which the students can develop. This is also an essential value of the specially designed programmes.

One of the interviewed students confirmed the merits of a school environment where the majority of students are academically orientated:

I was tired of school and did not just want the upper-secondary school to be an extension to the compulsory secondary school. I sought like-minded fellow students, rather than the specialization. Sought a context where they had the same view of studying and knowledge. Sought a challenge. (Student, Entrepreneurship)

From this perspective, the specially designed programmes resonate well with those students interested in looking for a milieu that favoured learning.

The failure to recruit the academically most able students appears to have diminished the specially designed programmes and to have transformed the programmes into specially privileged programmes for academically oriented students with varying aca-demic abilities:

In order to be qualified for enrolment in courses at university level as early as at the end of their second year on the programme, students needed to complete their upper- secondary courses in the chosen area at a faster pace. This acceleration affected their chances of performing at the peak of their ability. In combination with overlapping schedules, classes held in the evenings and a low degree of integration between upper- secondary and university courses, this led to about half of the students failing to complete any university courses. Students take mathematics courses worth 300 credit points beyond the required by the ordinary curriculum. These students have come quite a long way, and those who choose to stop before completion cannot be regarded as failures. It is natural that some choose to do this. They have made a choice, and they will take the experience with them. To assume that many students can take on a workload such as we have on the programme is unreasonable. (Teacher, mathematics)

As a result of the acceleration aspect within the programmes, about half of the students were content enough not to pursue university courses in their main subject after they had finished their upper-secondary courses. Instead, they took courses in other subjects that were likely to generate higher levels of credits:

If many leave the specially designed programme, this will not, in our eyes, be so good. There are students who are happy to study mathematics intensively for two years but then think it’s enough; they take a break from it and do not study any mathematics in their last year. The result is that they are not as well prepared as students who have studied mathematics continuously over three years. (University teacher, Mathematics)

The interviews with university teachers revealed that they saw the collaboration with schools as an opportunity to inform upper-secondary school students about their own university’s activities and to recruit future students. With such low numbers of students on the specially designed programmes, the university teachers were unable to give the students any special attention. Furthermore, they were uncertain that the students on the programmes were best suited to their subjects:

We must remember that they would not automatically become students at KTH Royal Institute of Technology just because they have taken the specially designed programme. They have to compete with others, and incredibly high grades are required for direct acceptance. It’s basically almost a question of 20 or 19.7 credits, so very few students from the specially designed programme will be accepted on KTH real estate and finance courses. (University teacher, economics)

Though the university teachers valued the programmes because they gave the students a solid upper-secondary education, they were concerned about the accelerated pace. They surmised that if the learning became too compressed and that the students had to rush through their education, they might question the benefit of continuing to university-level studies.

How the specially designed programmes transformed local school practice The trial was designed to involve schools that already offered an upper-secondary education with both subject breadth and depth and that were collaborating with uni-versity institutions and teachers. Prior to the trial, this took the form of special classes in particular subjects – such as mathematics or modern languages – for students who had shown themselves to be particularly able and interested in developing their knowledge in the field as far as possible.

One of the participating upper-secondary schools had, for example, already developed a mathematics section with special classes for students who had shown particular aptitude during their first year of upper-secondary education:

The mathematics section was a bit more low-key. The work on the specialized programme has become a little more defined. The framing has become different, including setting up high ability groups from year 1 at upper-secondary level. This has its advantages, but one becomes a little more constrained then. (Teacher, mathematics)

Prior to the trial, another participating upper-secondary school had developed a system of advanced classes in modern languages:

We have had a tradition of very, very, well, advanced language training and very good teachers in all these major languages. French had, to a certain extent, taken the lead. We had developed what we called CF [Classe française]. It was really the first thing that happened; and then we also had DK [Deutsche Klasse] and Clase español, so the tradition of advanced language training has been around a long time. When the option to start specially designed programmes came, we realized that this could be a way to formalize the framework and also make something really cool of it [. . .] we started [. . .] those old CF classes and Clase español, and so on, were mixtures of science and social science students [. . .] so then there were twice as many applicants. (Director of Studies, Classe française)

An unexpected effect of the implementation of the specially designed programme was that the previously developed – and obviously well functioning – flexible system of

courses for advanced learning was discontinued in favour of a less flexible system with one specially designed programme.

Since the specially designed programmes failed to attract sufficient numbers of students, the cost of running them was higher than for the closest corresponding national programmes, which had no difficulty attracting sufficient numbers of academically able students. In practice, the specially designed programmes were in part financially sup-ported both by the ordinary programmes and by the teachers who were directly involved:

I don’t have the energy to work full time. There is not a chance, so it’s on me . . . These small programmes cost a little more. But let them do that. That little . . . smaller classes, more teaching time per student, is my response. One cannot manage to have all these external contacts for all . . . classes. We are at the limit of what we can handle, manage the three classes that we have here. (Teacher, biology)

Both principals and teachers were strongly committed to their programmes. This was confirmed by the students, who also were highly committed. Though this resulted in a productive academic learning environment, the drawback was isolation from the other students at their schools:

. . . We kind of lived in an academic bubble. We worked close to our teachers, and we had assignments all the time [. . .] we were a special class in the school, for better or worse [. . .] we got more resources . . . we had such an intensive schedule in the first two years that we hardly had any contact with other classes. [. . .] I think it was a rather impoverished environment. When all in my class were, the wealthiest from this place, those with the brightest parents from that place. It felt so extremely silly. (Graduated student, humanities)

As corroborated by other students, increased segregation within their schools was a notable effect of the specially designed programmes. The principals and teachers, on the other hand, maintained that the programme had operated as a driving force in the development of the school as an educational institution. Educational developments were seen as having transmitted to other programmes:

They have developed one another, the school and the department . . . especially in chemistry and biology, but maybe also a little in maths [. . .] It’s not just that you are teaching students on the specially designed programme and no others. It is not just the highly able students who receive something extra. It will also indirectly benefit the other students. (Principal, biotechnology)

Cooperation between the specially designed programmes and the universities was facili-tated through some of the upper-secondary teachers already having research experience and close contacts with higher education institutions.

Our interview material also reveals that some principals and teachers saw the special programmes as an investment in their school brand. The schools used the specially designed programme as a means of further strengthening their position in the local school market. Schools tried to improve their position by focusing on academic orienta-tion and ability:

We were looking for ways of attracting academically able students to the school, which is why we applied to be included in the trial. The specially designed programme has been used to advertise the school, and the specialization will attract other students to the school. Students surely realize that this is likely to be good. (Teacher, social sciences and humanities)

The interviews showed that participating principals and teachers used the trial as an opportunity to promote their school and as a means of attracting greater numbers of academically able students.

Why the programmes were shaped as they were and why they changed the local school practices as they did

After the 1994 national curriculum reform, Sweden had a comprehensive upper- secondary education system. All national programmes, general as well as vocational, had uniform length, a common core curriculum, and provided general eligibility for higher education. They were built on a model of equal education that was based on the premise that individualisation could be accomplished in mixed ability classes (Lindblad et al. 2002; Skott 2009; Waldow 2008). During the 1990s, a series of reforms aimed at improving quality through decentralisation, accountability and greater reliance on choice and competition were implemented in Sweden, as in many other western countries, in an attempt to reorient itself in relation to the ‘welfare state crisis’ (Moe 2017; Wilborg 2013). In Sweden, a system of public and private schools, and free school choice entirely finance through taxes and school vouchers was implemented (Blossing, Imsen, and Moos 2014; Lundahl 2005; Lundahl et al. 2013) and conceived as an instrument designed to ensure equal education (Francia 2011; Lindensjö and Lundgren 2014). In the wake of this reform, it became increasingly important for schools to profile themselves in the school market, which led them to develop a variety of local special programmes to attract students. After a while, it became clear to the school politicians that this had led to an unclear situation. Attempting to retake the initiative in the development of upper- secondary education, first the social democratic and then the conservative liberal govern-ment set up a commission aimed at reducing the range of programmes offered. This led to a proposal for a new structure, which eventually also was implemented (SOU 2008). In addition, the commission suggested that the government, in order to meet the interests of the academically oriented most able students, should start a trial with specially designed general upper-secondary programmes. In this process, we can see a struggle between two partially different school political lines: a social democratic line that strives towards a more uniform upper-secondary school and a liberal-conservative line that strives towards increased curricular differentiation.

In line with the ideas of Engeström (2001), the actions of participants can only be understood in relation to the activity as a whole. The trial was implemented in a diversified education market system (Lundahl 2005; Lundahl et al. 2013; Wiborg 2010). Different schools had different resources and means of marketing themselves. In our sample, we found schools that already had developed systems and flexible solutions for supporting the academically most able (c.f. Englund and Quennerstedt 2008). In an upper-secondary education market characterised by competition for the academically most able students, it was important for schools to participate in the trial to continue to promote themselves as more academically excellent than their competitors. Not participating in the trial entailed running the risk of weakening their position in the market. Consequently, providing education for the academically most able became secondary to that of maintaining or improving their market position. Participation in the trial strengthened their position and their general ability not only to attract the academically most able students but also highly

qualified, not infrequently postdoctoral, teachers greatly interested in maintaining and developing contacts with their former university.

When the participating schools failed to reach out to and attract a sufficient number of the intended group, they expanded the target group to include not only the academically most able but also all interested students. This expansion in practice leads to a redefinition of the purpose of the trial in the local school context. Engeström’s fourth principle of activity theory, contradiction as a source of change (2001), indicates that it was the contradiction between what the trial regulations prescribed and what local school practice made possible that transformed local school practice. Overall, this meant a reformulation of the trial as a means to strengthen the competitive position of participating schools, thereby contributing to a continued and increased drift towards even greater school segregation.

The winners are not so much the intended target, ‘students with special talents in some area’ (Ministry of Education 2008b, 2), but the group of ‘interested students’. The programme became more a ‘talent-creating education’ that is characterised by the students’ efforts and active approaches and the teacher’s competence, commitment and high expectations of the students (Balchin, Hymer, and Matthews 2009). The programme was based on acceleration, and it allowed students to complete upper-secondary school courses at a faster pace. Though the time that the students gained from the acceleration was meant to be used for further studies at the university level, it was often used for catching up on missed credit points or taking miscellaneous courses for extra credits, or to relax after several semesters of intensive study. Thus, the opportunity to specialise tended to become an illusion. The distinctive character of the specially designed pro-grammes was partly lost. New and unintended activities replaced intended activities (cf. Engeström 2001, the fifth principle). Consequently, the idea of supporting high- achieving students by acceleration appears not as successful as the enrichment idea embodied in the special courses in the programme that made it possible for students to access other teaching content and other learning activities in order to broaden and deepen their understanding (Hattie 2009).

Discussion

The possible benefits of specially designed programmes appear to mean different things to different actors. From the perspective of the Government, as represented by the National Agency for Education, the trial signals that the educational needs of the academically most able students are taken seriously (SFS 2010:800; Ministry of Education 2008a). From the perspective of the school principals, while the pro-grammes are no cash cow, admission to the trial is regarded as a form of quality recognition that might make a difference in the marketing of the school as a whole with all its various programmes. From the perspective of the teachers, the trial is an opportunity to develop new courses in their special field of competence in collabora-tion with colleagues at the university and an opportunity to teach especially interested and study motivated students. From the perspective of the university teachers, the trial is an opportunity to market their subjects and programmes and to recruit more and better-prepared students for their courses. However, this has mostly failed to materialise because of the small numbers of potential student recruits on the

programmes. From the perspective of the participating students, the specially designed programmes give them a chance to enter a favoured school environment and a classroom where school work is taken seriously by both the teachers and the majority of their peers.

From our perspective, the means and methods employed in the trial do not match the stated goals. The trial assumes that there is a need for nationwide recruiting in specially designed programmes in academic subjects that offer further specialisation than for the corresponding general national upper-secondary general programmes. However, the very construction of the upper-secondary education provides a powerful element that blocks this, namely, the need for courses that yields more points and credits. The specially designed programmes cannot fulfil this requirement to the desired extent.

The trial builds on the idea of acceleration as a means to support the academically most able as if education was a race in time, while enrichment is more in tune with academic values as represented by several of the participating teachers. So, who benefits from acceleration?

It seems like that the majority of the academically most able students did not regard the specially designed programmes as a highway to success in terms of grades and credits; thus, they have tended to avoid them. From the interviews with graduates, it also appeared that they found the programmes too narrow and restrictive, which might also be a disincentive. Long-term educational dilemmas – such as early versus late differentiation or general versus specialised education – are still a living reality on a personal level.

In sum, perhaps the most important finding from the study of the trial is that the involved teachers and students both desire to teach and study at a higher level, and that the opportunity to develop and engage in locally developed academic courses within general national academic upper-secondary programmes is a possibility that should be explored further. In addition, it could be of interest to compare how different countries have catered for the academically most able students and how these initiative work in practice (c.f. Campbell et al. 2007; Fischer and Müller. 2014).

Notes

1. How different categories of parents with respect to political and educational preferences resonate with this is still an open question.

2. The Social Democrats and Green Party minority coalition that has governed since 2014 has not made any alterations of this decision.

3. The results of the consultation included a proposal for a new structure of upper-secondary education with a distinct division of general and vocational programmes, but it also proposed to create specially designed general programmes for the academically most able (Ministry of Education 2008b).

Disclosure statement

Notes on contributors

Glen Helmstad (phD) is senior lecturer in education at the Department of Educational Sciences at Lund University. He is director of studies and lecturer in the teacher education. His research interest focus on university teachers and professional development.

Marie Jedemark (phD) is senior lecturer in educational sciences at Malmö University, Department of School development and Leadership. Her research focuses on teacher professionalism and teacher education. She also lecturer in the teacher education at Malmö University.

ORCID

Glen Helmstad http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5303-8008

Marie Jedemark http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3371-8559

References

Balchin, T., B. Hymer, and D. J. Matthews. 2009. “The Routledge International Companion to

Gifted Education. [Electronic Resource]. Routledge.” International Companions. Routledge.

https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo. b1850113&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Blossing, U., and Söderström. Å. 2014. “A School for Every Child in Sweden.” The Nordic

Education Model: “A School for All” Encounters Neo-liberal Policy. edited by U. Blossing,

G. Imsen, and L. Moos, 17–34. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://link.springer.com/ book/10.1007%2F978-94-007-7125-3

Blossing, U., G. Imsen, and L. Moos. 2014. “Progressive Education and New Governance in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.” The Nordic Education Model: “A School for All” Encounters

Neo-liberal Policy. edited by U. Blossing, G. Imsen, and L. Moos, 231–239. Dordrecht: Springer

Netherlands. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-94-007-7125-3

Campbell, J., D. Muijs, J. Neelands, W. Robinson, D. Eyre, and R. Hewston. 2007. “The Social Origins of Students Identified as Gifted and Talented in England: A Geo-demographic Analysis.” Oxford Review of Education 33 (1): 103–120. doi:10.1080/03054980601119664. Castejón, A., and A. Zancajo. 2015. “Educational Differentiation Policies and the Performance of

Disadvantaged Students across OECD Countries. European.” Educational Research Journal 14 (3–4): 222–239. doi:10.1177/1474904115592489.

Chaiklin, S., and J. Lave. 1993. Understanding Practice: Perspectives on Activity and Context. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo.b2285328&lang=sv&site= eds-live

Education Act 2010. “800.” Retrieved February 18, 2020 from: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/doku ment-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

Engeström, Y. 2001. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work 14 (1): 133–156. doi:10.1080/ 13639080020028747.

Englund, T., and A. Quennerstedt. 2008. Vadå likvärdighet? Studier i utbildningspolitisk

språkanvändning [What Do You Mean by Equivalency? Studies in Language Use in

Educational Politics]. Gothenburg: Daidalos. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebs cohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo.b1566329&lang=sv&site=eds- live

Fischer, C., and M. Kerstin. 2014. “Gifted Education and Talent Support in Germany.” Center for

Educational Policy Studies Journal 4 (3): 31–54. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct= true&db=eric&AN=EJ1129537&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Francia, G. 2011. “Dilemmas in the Implementation of Children´s Right to Equity in Education in the Swedish Compulsory School.” European Educational Research Journal 10 (1): 102–117. doi:

http://dx.doi.org/102304/eerj.2011.10.1.102.

Gamoran, A., M. Nystrand, M. Berends, and P. C. LePore. 1995. “An Organizational Analysis of the Effects of Ability Grouping.” American Educational Research Journal 32 (4): 687–715. doi:10.2307/1163331.

Government bill 2008/09:19. Högre krav och kvalitet i den nya gymnasieskolan [Increases in Requirements and Quality in the New Upper Secondary School].

Hattie, J. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

Haug, P., N. Egelund, and B. Persson. 2006. Inkluderande pedagogik i skandinaviskt perspektiv [Inclusive Pedagogy in a Scandinavian Perspective]. Stockholm: Liber. https://proxy.mau.se/ login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo. b1378230&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Helmstad, G., and M. Jedemark. 2013a. Försöksverksamhet med riksrekryterande gymnasiala

spet-sutbildningar: En aktörsfokuserad utvärdering av de 11 utbildningsprogram som startade hösten 2010 [Trial of Specially Designed Upper Secondary General Programmes with Nationwide

Recruitment: A Participant-focused Evaluation of the 11 Programmes that Started in the Autumn of 2010]. In National Agency for Education (2014). Redovisning av uppdrag enligt förordning (2008:793) om försöksverksamhet med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning och regleringsbrev för 2014 avseende omfattning och utvärdering av försöksverksamheten med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning. Appendix 3. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved 28 June 2018 from: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3285

Helmstad, G., and M. Jedemark. 2013b. Det retrospektivt upplevda värdet av den gymnasiala

spetsutbildningen: En uppföljning av unga vuxnas erfarenheter omkring ett och ett halvt år efter deras examen [The Retrospectively Estimated Value of the Specially Designed Upper

Secondary General Education Programme: A Follow-up of the Experiences of Young Adults about 18 Months after Graduation]. In National Agency for Education. 2014. Redovisning av uppdrag enligt förordning (2008:793) om försöksverksamhet med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning och regleringsbrev för 2014 avseende omfattning och utvärdering av försöksverksamheten med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning. Appendix 4. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved 28 June 2018 from: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer? id=3285

Lindblad, S., L. Lundahl, J. Lindgren, and G. Zachari. 2002. “Educating for the New Sweden?”

Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 46 (3): 283–303. doi:10.1080/ 0031383022000005689.

Lindensjö, B., and U. P. Lundgren, 2014. Utbildningsreformer och politisk styrning [Education Reforms and Political Direction]. (2nd ed.). Stockholm: Liber. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url= https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo. b1836434&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Lundahl, L. 2005. “A Matter of Self-governance and Control: The Reconstruction of Swedish Education Policy, 1980–2003.” European Education 37 (1): 10–25. doi:10.1080/ 10564934.2005.11042375.

Lundahl, L., I. E. Arreman, A.-S. Holm, and L. Ulf. 2013. “”Educational Marketization the Swedish Way.”.” Education Inquiry 4 (3): 497–517. doi:10.3402/edui.v4i3.22620.

Lundahl, L., I. E. Arreman, U. Lundström, and L. Rönnberg. 2010. “Setting Things Right? Swedish Upper Secondary School Reform in a 40-year Perspective.” European Journal of Education 45 (1): 49–62. doi:org.proxy.mau.se/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2009.01414x.

Marklund, S. 1989. Skolsverige 1950–1975. D. 6. Rullande reform [School Sweden 1950–1975. Part 6. Continuous Reform]. Stockholm: Liber/Utbildningsförlag. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url= https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo. b1037738&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ministry of Education. 1994. 1994 års läroplan för de frivilliga skolformerna, Lpf 94: Särskilda

programmål för gymnasieskolans nationella program; Kursplaner i kärnämnen för gymnasiesko-lan och den gymnasiala vuxenutbildningen. [Curriculum 1994 for the Post-compulsory School].

Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet. Retrieved 1 March 2018 from 1 March 2018: http://hdl. handle.net/2077/30998

Ministry of Education. 2007. “Gymnasieutredningen.” [The Upper Secondary School Commission]

(U 2007:1). Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

Ministry of Education. 2008a) Förordning 2008: 793om försöksverksamhet med riksrekryterande

gymnasial spetsutbildning [Ordinance 2008: 793on Trial of Upper Secondary Elite Education

with Nationwide Recruitment]. (SFS No. 2008:793). Retrieved 28 June 2018 from 28 June 2018:

https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/forordn ing-2008793-om-forsoksverksamhet-med_sfs-2008-793

Ministry of Education. 2008b. Inrättande av försöksverksamhet med riksrekryterande gymnasial

spetsutbildning [Establishment of Trial Upper Secondary Elite Education with Nationwide

Recruitment]. (Memorandum 26 May 2008). Stockholm: Regeringskansliet

Moe, T. M. 2017. “The Comparative Politics of Education: Teachers Unions and Education System around the World.” In The Comparative Politics of Education. Teachers Unions and Education

System around the World, edited by T. M. Moe and S. Wiborg, 269–324. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Musset, P. 2012. School Choice and Equity: Current Policies in OECD Countries and a Literature Review, OECD Education Working Papers, no. 66. Paris: OECD Publishing.

National Agency for Education. 2012. Redovisning av uppdrag enligt förordning (2008:793)

avseende omfattning och utvärdering av försöksverksamheten med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning läsåret 2011/12 [Report of Commission Established under Ordinance (2008:793)

on Trial Upper Secondary Elite Education with Nationwide Recruitment] (Ref. no. 60–2008:3014). Retrieved 26 March 20013 from: http://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/pub licerat/visa-enskild-publikation?_xurl_=http%3A%2F%2Fwww5.skolverket.se%2Fwtpub% 2Fws%2Fskolbok%2Fwpubext %2Ftrycksak%2FRecord%3Fk%3D2882

National Agency for Education. 2014. Redovisning av uppdrag enligt förordning (2008:793) om

försöksverksamhet med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning och regleringsbrev för 2014 avseende omfattning och utvärdering av försöksverksamheten med riksrekryterande gymnasial spetsutbildning [Report of Commission Established under Ordinance (2008:793) on Trial Upper

Secondary Elite Education with Nationwide Recruitment and Regulatory Letter of 2014 on the Scope and Evaluation of the Trial of Upper Secondary Elite Education]. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved 28 June 2018 from 28 June 2018: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3285

Oakes, J., A. Gamoran, and R. N. Page. 1992. “Curriculum Differentiation: Opportunities, Outcomes, and Meanings.” Handbook of Research on Curriculum: A Project of the American

Educational Research Association. edited by P. W. Jackson, 570–608. New York: Macmillan.

https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db= cat05074a&AN=malmo.b1081295&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Richardson, G. 1983. Drömmen om en ny skola: idéer och realiteter i svensk skolpolitik 1945–1950 [The Dream of a New School: Ideas and Realities in Swedish Educational Policy 1945–1950]. Stockholm: Liber. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx? direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo.b1605258&lang=sv&site=eds-live

Skott, P. 2009. Läroplan i rörelse: Det individuella programmet i mötet mellan nationell

utbildning-spolitik och kommunal genomförandepraktik. [The Interplay between National Educational

Policy and Local Practice: A study of curriculum processes] (Uppsala studies in Education, 122; Academic thesis). Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Uppsaliensis.

Slavin, R. E. 1987. “Ability Grouping and Student Achievement in Elementary Schools: A Best Evidence Synthesis.”.” Review of Educational Research 57 (3): 293–336. doi:10.2307/1170460. SOU 1974:53. Utredningen om skolans inre arbete. Skolans arbetsmiljö: betänkande [An Enquiry

into the Inner Working of the School System: Working Environment]. Stockholm: Allmänna förlaget.

SOU 2008:27. Framtidsvägen: En reformerad gymnasieskola [The Future Road: A Reformed Upper Secondary School]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Waldow, F. 2008. Utbildningspolitik, ekonomi och internationella utbildningstrender i Sverige

1930–2000 [Education Policies, Economy and International Educational Trends in Sweden

1930–2000]. Stockholm: Stockholm University. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo.b1764821&lang=sv&site= eds-live

Wiborg, S. 2004. “”Education and Social Integration: A Comparative Study of the Compulsory School System in Scandinavia.”.” London Review of Education 2 (2): 83–93. doi:10.1080/ 1474846042000229430.

Wiborg, S. 2009a. Education and Social Integration: Comprehensive Schooling in Europe. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230622937.

Wiborg, S. 2009b. “”The Enduring Nature of Egalitarian Education in Scandinavia: An English Perspective.”.” Forum 5 (2): 117–130. doi:10.2304/forum.2009.51.2.117.

Wiborg, S. 2010. “”Learning Lessons from the Swedish Model.”.” Forum 2 (3): 279–283. doi:10.2304/forum.2010.52.3.279.

Wiborg, S. 2013. “”Neo-liberalism and the Universal Stated Education: The Cases of Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1980-2011.”.” Comparative Education 49 (4): 407–423. doi:10.1080/ 03050068.2012.700436.

Wiborg, S. 2017. “Teachers Union in the Nordic Countries: Solidarity and the Politics of Self- interest.” In The Comparative Politics of Education. Teachers Unions and Education System

around the World, edited by T. M. Moe and S. Wiborg, 144–191. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Ziegler, A., H. Stoeger, B. Harder, and D. P. Balestrini. 2013. “Gifted Education in German-Speaking Europe.” Journal for the Education of the Gifted 36 (3): 384–411. doi:10.1177/0162353213492247.