Swedish Student-Athletes’ Within-Career Transitions

Sverker Fryklund Malmö University Department of Sport Sciences

Supervisors: 1) Urban Johnson, Halmstad University 2) Tomas Peterson, Malmö University

Abstract

The main purpose of this research project was to examine perceptions of within-career transition, as experienced by student-athletes striving to reach the international level.

Interviews were used to examine the perceptions of student-athletes practicing individual sports at the national elite level. Eight categories were identified through thematic content analysis: changes experienced in the transition, career assistance, resources for adjusting to the new level in sport, satisfaction with their current situation, strategies for adjusting to the new level in sport, changes during a dual career, combining studies and everyday life, and strategies for adjusting to a dual career. The student-athletes emphasised prolonged career assistance, interpersonal support, dedication, and commitment, and recognised the need for coping strategies such as stress and time management. Suggestions for promoting successful within-career transitions for student-athletes are discussed.

Keywords: within-career transition, achievement sport, thematic content analysis, student-athlete, career assistance, dual career.

Sammanfattning

Syftet med föreliggande forskningsprojekt var att undersöka upplevelser av

karriärövergångar hos elitidrottande studenter, på högsta nationella nivå, som strävar efter att etablera sig även på internationellt högsta nivå inom sin idrott, samtidigt som de börjar studera vid universitet/högskola och så småningom tillägnar sig en examen.

Semistrukturerade intervjuer användes för att kartlägga och undersöka de elitidrottande studenternas upplevelser. De kategorier som identifierades genom tematisk innehållsanalys var upplevda förändringar i övergången, karriärstöd, resurser för att anpassa sig till den nya nivån i idrotten, upplevd tillfredsställelse med situationen, strategier för att anpassa sig till den nya nivån i idrotten, upplevda förändringar under en dubbel karriär (studier och idrott),

upplevelsen av att kombinera studier, idrott och ett “vanligt” liv, och strategier för att hantera detsamma. De elitidrottande studenterna lyfte fram kontinuerligt karriärstöd, interpersonligt stöd och betonade behovet av att utveckla coping strategier som stresshantering och time-management. Åtgärder för att underlätta framgångsrika karriärövergångar för elitidrottande studenter diskuteras.

Table of contents

Introduction 6

Background 7

Definitions and characteristics of career transitions in sport 10

Athletic career 10

Student-athletes 10

Career transitions in sport 10

Conceptual and theoretical frameworks 11

Athletic career descriptive models 12

The four-stage sports career model 13 The developmental model of transition faced by athletes 13

The analytical career model 15

Career explanatory transition models 15

Model of human adaption to transition 16 Conceptual model of adaption to career transition 16 The athletic career transitions model 17

The psychological field theory 19

Key issues in career transitions in sport 20 Athletic identity and student identity 20

Coping resources 22

Athletes’ non-athletic transitions 24

Student-athletes and dual career 25

Injuries 29

Career assistance/transition programs 29

Summary and objective of the studies 32

Method 34

Participants 34

The career assistance program 36

Procedure 36

Data analysis 38 Results 39 Study 1 39 Study 2 44 Discussion 50 Study 1 50 Study 2 55

Comparison between study 1 and study 2 60

Methodological considerations 61

General discussion and practical implications 63

Conclusions and future research 67

References 70

Attachments 82

Introduction

A growing body of literature is emerging on the topic of career transitions in sport. According to Stambulova (2010), by 2007, more than 270 empirical and theoretical citations had been identified on sports career transition issues. The managing council of the European Federation of Sport Psychology (FEPSAC) has also contributed to the publication of a

position statement on career transition in sport (Wylleman, Lavallee & Alfermann, 1999), and the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) through Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler & Côté (2009), has done the same.

Today, the focus in applied sport psychology is shifting from the

performance-enhancement perspective to the holistic lifespan perspective (Stambulova, 2010; Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007; Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler, & Coté, 2009; Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). Promoters of the holistic lifespan perspective treat athletes as individuals who participate in sports alongside other things in their lives. Within this perspective, an athletic career is seen as an integral part of a lifelong career. Helping athletes to achieve both athletic and personal excellence and to use their athletic experiences for the benefit of a lifelong career have become the major objectives of career assistance to athletes (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004; Stambulova, 2010). One aspect of this is combining university-level study with participation in high-achievement sports. The combination of sport and academic education is demanding (Bengtsson & Johnson, 2010; MacNamara & Collins, 2010; Kane & Holleran, 2008; Martinelli, 2000). Academic success and progress require carefully planned use of time for both sport and study. Educational systems generally assume that students are, for the most part, studying full-time; and so any matters affecting the student’s schedule, such as work and sport, make progress more difficult (Bengtsson & Johnson, 2010). One condition for success in sport today is the need to devote as much as 20 - 30 hours each week to practice and competition (ibid.), which in the absence of a flexible curriculum makes it difficult to

combine full-time study with competitive sport (Scott, Paskus, Miranda, Petr & McArdle, 2008; Petitpas, Champagne, Chartrand, Danish & Murphy, 1997; Petitpas, Brewer & Van Raalte, 1997).

Some athletes are able to make a profession out of the sport they engage in. Nevertheless, most athletes are able to live on their sport only as long as they are engaged in it, while others will never reach an athletic standard that would ensure them a livelihood. Currently, there is a shortage of (and a need for) research on student-athletes and dual career. Consequently, it is important to understand the process by which student-athletes adapt to and cope with transition-related demands, because of its influence on successful and unsuccessful within-career transitions.

The main purpose of the two studies within this research project was to examine

perceptions of within-career transition, as experienced by student-athletes striving to reach the international level. The aim of the first study was to examine the experiences of 26 national elite-level student-athletes striving to reach the international elite level, during a normative within-career transition (transition to university), and the aim of the second study was to examine the experiences of 16 national elite-level student-athletes striving to reach the international elite level, during a dual career transition (prolonged university studies and elite sports).

Background

Studies on career development and transitions of athletes started appearing in the 1960s, and have shown a substantial increase in both quantity and quality since the end of the 1980s. The evolution of the topic within sport psychology has been characterised by several major shifts in research focus, theoretical frameworks, and attention to contextual factors (see e.g., Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007; Wylleman, Alfermann, & Lavallee, 2004).

The first major change was an observable shift in understanding "a transition" as a phenomenon; this was echoed as a similar shift in the theoretical frameworks used for studying athletes' transitions. Historically, pioneering transition studies in sport focused on athletic retirement, which was considered analogous to retirement from a non-sporting career. Therefore, early theoretical frameworks were derived from thanatology (the study of the stages of dying) and social gerontology (the study of the aging process) (Wylleman, Lavallee, & Alfermann, 1999; Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler & Coté, 2009). As a result, an athlete’s transition to the post-career was typically presented as a negative and often traumatic life event. Schlossberg (1981) suggested a definition of transition as "an event or non-event, which results in a change in assumptions about oneself and the world, and thus requires a corresponding change in one's behaviour and relationships" (p. 5). This general psychology definition was initially well adopted in sport psychology, but later challenged by transition research in sport sciences, especially the part of the definition that identifies a transition as an event/non-event. For example, athletic retirement studies indicated that adaptation to the post-career took about one year on average, and that far from all former athletes experienced post-career termination as a negative life event (Sinclair & Orlick, 1993; Alfermann, 2000). This new understanding of transition as a coping process with potentially positive or negative outcomes is well reflected in the athletic career termination model (Taylor & Ogilvie, 1994) and the athletic career transition model (Stambulova, 2003).

A second major change in the career development and transition research was the departure from focusing almost exclusively on athletic retirement, to studying a range of transitions within an athletic career—the so-called "whole career" approach. In many

countries, this new trend in career transition research was inspired by theoretical debates and research around talent development. For instance, Durand-Bush and Salmela (2001) analysed athletic talent definitions and indicated a shift in understanding athletic talent, from focusing

mainly on the innate part of the talent (popular in the 1970s and 1980s) to emphasising its acquired part (since the 1990s). This was followed by a shift in theoretical frameworks, from talent selection/detection models to talent development models (see also Lidor, Côté, & Hiackfort, 2009). Bloom's model (1985) of the three stages in talent development and Ericsson's (1996) 10-year rule for reaching expert performance level can be seen as

predecessors of the current career development descriptive models in sport psychology. It is also important to note that the talent development process occurs within a career development context, and contributes to the athlete's internal resources for coping with career transitions.

A third major change in the career development and transition topic was the shift from an exclusive focus on athletes' transitions in sport to more of a whole-person lifespan

perspective, in which athletic career transitions were viewed in relation to developmental challenges and transitions in other spheres of the athletes' lives (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). Finally, the fourth change was related to the understanding of the role of contextual factors in career development and transitions. While earlier studies focused primarily on how coaches, parents, and peers contribute to athletes' career development and transitions (Côté, 1999; Wylleman, De Knop, Ewing, & Cumming, 2000), more recent studies also consider the role of macro-social factors such as the sport system and culture (Stambulova, Stephan, & Järphag, 2007).

Wylleman, Theeboom, and Lavallee (2004) concluded in their summary of the field that research into the career development of athletes has been evolving in recent decades from focusing on the termination of the sporting career into a holistic, lifespan, multilevel approach to athletes’ sports and post-sports careers.

Definitions and characteristics of career transitions in sport

Athletic career

"Athletic career" is a term for a voluntarily-chosen multi-year sport activity aimed at the achievement of the athlete’s individual peak in athletic performance in one or more sport events (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). In this, "career" relates to all levels of competitive sports. Depending on the highest level of sport competition achieved by the athlete, an athletic career can be local, regional, national, or international; and depending on the athlete's status, the career can be amateur or professional. International level amateur or professional careers are often also labelled as elite careers (Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler & Coté, 2009).

Student-athletes

The term “student-athletes” refers to athletes that are undertaking a scholastic and academic development/career while simultaneously undertaking an athletic career (Wylleman et al., 1998).

Student-athletes need to cope not only with the transitions in their athletic career, but also with the basic transitions in their education and the transitions inherent to each level of

education. These transitions require student-athletes to adjust to and cope with challenges and changes occurring in the combination of academics and athletics (ibid.; Stambulova, 2010).

Career transitions in sport

As mentioned earlier, a transition can be defined as “an event or non-event, which results in a change in assumption about oneself and the world and thus requires a

corresponding change in one’s behaviour and relationship” (Schlossberg, 1981 p. 5). A contemporary description is that the career transitions in sport come with different demands related to practice, competition, communication, and lifestyle. If athletes wish to have a

successful sport career, they must cope with the new demands (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007).

Two types of transitions are identified in the literature: normative and non-normative

transitions. The normative transition is generally predictable and anticipated; it consists of an athlete leaving one stage and entering another. In the athletic domain, normative transitions can include the beginning of sport specialisation as well as transitions from junior to senior level, from regional to national level, and from amateur to professional status. In contrast to normative transitions, non-normative transitions are difficult to predict and often involuntary (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). They do not occur in a set plan or schedule. Non-normative transitions are situation-related and specific to the individual (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). For athletes these transitions may include injuries, overtraining, the loss of a personal coach, or moving from one team to another. These transitions also include events that were expected or hoped for but did not occur – these are known as events. Examples of non-events include being unable to participate in major tournaments, or not being selected for the national team after years of preparation (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

Conceptual and theoretical frameworks

Most of the interest within sports psychology has centred around the end or termination of an athlete’s career and the beginning of a post-athletic career. In this tradition, as described previously, early theoretical frameworks were derived from thanatology (the study of the process of dying and death) (Kubler-Ross, 1969) and (social) gerontology (the study of the ageing process). Several thanatological models have been suggested, such as the social death model, which implies that athletic retirement is comparable to loss of social functioning and the resulting isolation (e.g., Kalish, 1985); the social awareness perspective, which initiates the process of growing awareness of impending death, mutual pretence, and open awareness);

and the stage model, which includes the phases of denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance of the athletic career termination (Kubler-Ross, 1969).

Although the models of social gerontology and thanatology were instrumental in stimulating research on career termination issues, each of these perspectives had limitations such as development from non-sport populations, a limited focus on lifespan development of athletes, and the presumption of the career termination process as an inherently negative event, which rendered them inadequate for explaining the process of sports career

termination. Many of the theories and models that have been used to describe the athletic career were developed and revised following research conducted in the area (Wylleman, Theeboom & Lavallee, 2004). There are currently two major theoretical frameworks in sport career transition: the athletic career descriptive models and the career transition explanatory models. These two theoretical frameworks and their corresponding models are described in detail below.

Athletic career descriptive models

Athletic career descriptive models aim to predict the normative transitions that athletes might experience. These models usually describe the athletic career as a “miniature lifespan course” divided into several stages: preparation and sampling; initiation; development and specialisation; perfection, mastery, and investment; and discontinuation of involvement in competitive sport. They then describe the changes in athletes and in their social environment across these stages (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). The models do not explain the

transition processes, but rather describe and predict the existence and order of the athletes’ normative career transitions (ibid.)

The four-stage sports career model (Salmela, 1994)

According to Salmela (1994), a career in sports is built on a descriptive model of career development which consists of three active phases: initiation, development, and mastery. The athlete becomes involved in sport as a child, during the initiation phase. During these years, the parents are responsible for initially getting their children interested in sport. The second stage is the developmental phase, which starts when the athletes increase their commitment to sport and begin to focus more on the improvement of skills and techniques. In the mastery phase, athletes are obsessed with their sport; they are committed to achieving an elite level of performance. In the last phase, discontinuation, the athlete’s commitment is decreasing as their career comes to an end. In each of these career development phases, parents and athletes must adapt to meet the different demands that are placed on them.

The developmental model of transition faced by athletes (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004)

The developmental model of transition faced by athletes reflects the strong links between the transitions in an athletic career and the transitions occurring in other domains of the athletes’ lives, on levels such as the individual, psychosocial, and academic/vocational. This model uses a “whole person” and a “whole career” approach in order to help us see the demands and transitions that occur outside the sport as well as in a sport context. These transitions will usually occur in a simultaneous and interacting way. If the transitions in different spheres of life overlap, this can lead to difficult life situations for the athletes; consequently, it is highly important to be able to predict such overlaps.

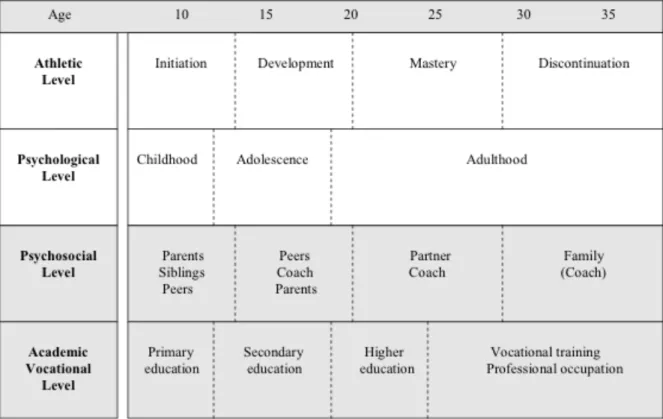

Figure 1 provides an overview of the normative transitions athletes will face on the athletic, individual, psychosocial, and academic/vocational levels, according to the developmental model of transition faced by athletes (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

Insert figure 1 about here

The top layer of this model reflects the athletes’ development in elite sport (though these stages can also be considered for athletes at a non-elite level). The layer consists of four stages and transitions that the athletes face in their athletic development. The first stage is called the initiation stage, and occurs when young athletes are introduced to organised sport and identified as talented athletes. The next stage, the development stage, occurs around the age of 12 or 13 when the athletes become more dedicated to their sport, start to specialise, and increase their participation in training and competition. At the mastery stage, which occurs around the age of 18 to 19, the athletes have reached their highest level of athletic proficiency. When the athletes discontinue further participation in high-level competitive sport, at

approximately age 28 to 30, they have reached the discontinuation stage. It is important to take into account that these age limits are averaged over many athletes and several different sports, and therefore may not be seen as sport-specific. The second layer of the model reflects the normative stages and transitions occurring at the psychological level. It is divided into childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Lavallee, Kremer, Moran & Williams, 2004). The third layer focuses on the athletes’ psychosocial development, covering the development of relationships with different groups and individuals, such as parents, coaches, peers, and spouses (Lavallee, Kremer, Moran & Williams, 2004). The final layer contains the specific stages and transitions occurring at the academic/vocational level, including transitions into primary education/elementary school (at the age of 6 or 7 years), to secondary education/high school (at 12 or 13), and into higher education (at 18 or 19). The last stage in this layer is the transition into vocational training or a professional occupation. This may occur at an earlier age, but here is included after higher education since this reflects the “normal” sports career in North America, where college/university links to high school varsity and professional sport.

The current development in Europe implies that many athletes continue their education up to the level of higher education (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). The developmental model of transition faced by athletes illustrates the concurrence of transitions occurring at different levels of development; for example, the transition from primary education to secondary education occurs at roughly the same time as the athletic transition from initiation to development (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004).

The analytical career model (Stambulova, 1994)

The analytical career model predicts seven normative transitions in an elite sports career. These transitions, which can overlap to a certain extent, are as follows:

1. The beginning of sport specialisation

2. The transition to more intensive training in chosen sport 3. The transition to high-achievement sport

4. The transition from junior to senior sport

5. The transition from amateur sport to professional sport 6. The transition from peak to the end of sports career

7. Athletic career termination and transition to other professional career

Career explanatory transition models

The career transition models focus on reasons, demands, coping, outcomes, and consequences related to a transition. Coping processes are central in all these models, and include all approaches used by the athletes to adjust to the particular set of transition demands (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007).

Model of human adaption to transition (Schlossberg, 1981)

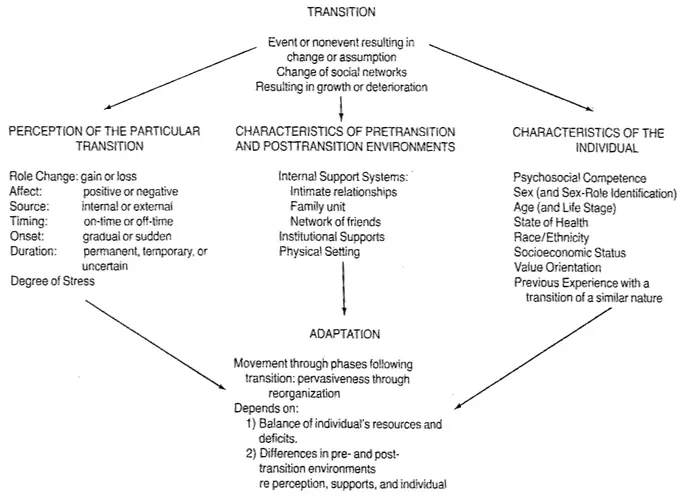

The model of human adaption to transition proposed by Schlossberg (1981) strives to describe the diversity in the experience of transitions. The model consists of three

components, which form a framework for understanding how certain features and variables of a transition may interact in a fashion unique to the individual experience. The first component considers the transition in terms of type, context, and impact. The second component

considers the individual’s coping resources, the balance of present and possible assets and liabilities, including variables that characterise the particular transition, individual, and environment. The third component considers the transition as a process, covering the ways in which the individual reacts to the experience over time, involving phases of assimilation and appraisal. Figure 2 provides an overview of the model. The model attempts to reflect

variability in the experience of transitions, and includes a comprehensive and expandable list of potentially influential variables and features. By emphasising the interaction of individual and environment, the model is particularly helpful in developing an understanding of the process of a transitional experience; that is, the context in which the experience takes place, the meaning it has for the individual, and how it changes over time (Swain, 1991).

Insert figure 2 about here

Conceptual model of adaption to career transition (Taylor & Ogilvie, 1994)

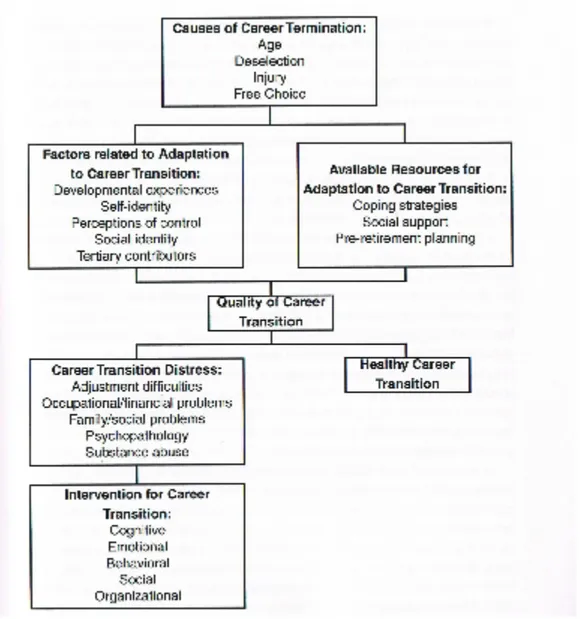

The conceptual model of adaption to career transition proposed by Taylor and Ogilvie (1994) aims to addresses the entire course of the athletes’ transition experience. This model suggests that the sport-career transition of high-level athletes is multidimensional and involves psychosocial (emotional, social, financial, and occupational) factors that interact in response to the sport-career transition and account for the disposition of the athlete in

transition. The model proposes five developmental aspects: 1) causes of career termination, 2) factors related to adaption to career transition, 3) available resources for adaption to career transition, 4) career transition distress, and 5) interventions for career transition. Figure 3 provides an overview of the model.

Insert figure 3 about here

The athletic career transitions model (Stambulova, 2003)

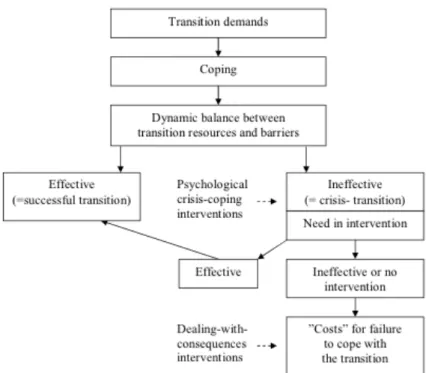

The athletic career transitions model (Stambulova, 2003) treats the career transition as a process rather than a single event. If an athlete is to continue with a successful athletic career, they must cope with a set of specific demands and challenges.

A set of transition demands creates a developmental conflict between what the athlete is and what they want or ought to be. This stimulates the athlete to mobilise their resources and find ways to cope. How effectively the athlete will cope with the transition depends on the balance between coping resources and barriers in the transition.

Resources and barriers can be both external and internal. Transition barriers include all internal and external factors that interfere with effective coping, such as lack of necessary knowledge or skills, interpersonal conflicts, lack of financial support, and difficulties in combining sport and education or work. Transition resources include all internal and external factors that make the coping processes easier, such as the athlete’s knowledge, skills,

personality traits, motivation, and financial support.

Figure 4 shows coping as a key point which divides the model into two parts. The upper part of the model covers the demands which need to be coped with and the factors influencing coping, while the lower part outlines two possible outcomes and consequences of a career transition.

Insert figure 4 about here

The two possible outcomes of the coping process are successful transition and crisis

transition. Athletes who can mobilise their resources or develop the resources necessary to cope with the demands in an effective way will have a positive transition. Conversely, athletes who cannot adequately cope with the situation will face a crisis transition. Reasons for

ineffective coping might include low awareness of transition demands, lack of resources, persistence of barriers, and lack of ability to analyse the situation in order to make proper decisions. An athlete who receives structured psychological intervention may be able to change the ineffective coping strategies and allow them to have an impact on the long-term consequences of the transition. If the intervention is effective, the athlete will make a positive (albeit delayed) transition. If the intervention is ineffective, or the athlete does not receive any qualified psychological assistance, the resulting “costs” of the failure to cope with the

transition may include decline in sport results, overtraining, premature dropout from sport, different forms of rule violations, injuries, psychosomatic illnesses, neuroses, and degradation of personality (manifesting as, for example, alcohol and drug use or criminal behaviour).

Three kinds of interventions are suggested for use during a career transition. The first consists of crisis-prevention interventions aimed at preparing the athletes to cope with a transition and helping them develop all the necessary resources before or at the very

beginning of each transition. Effective interventions at this stage of a transition include goal setting and planning, mental skills training, and organisation of social support systems, all of which can increase the athletes’ readiness for a normative sport career transition. The second type of intervention is appropriate when it is obvious that the athlete is in a crisis; at this

point, psychological crisis-coping interventions are needed. These interventions strive to help the athletes to find the best available way to cope by analysing the situation and responding accordingly. Finally, when the athletes have experienced one or more negative consequences of failing to cope with a crisis transition, psychotherapeutic or clinical intervention is often needed.

The psychological field theory

The psychological field theory considers behaviour to be determined by the totality of an individual’s situation. In this theory, which was developed by Kurt Lewin, a field is defined as “the totality of coexisting facts which are conceived of as mutually

interdependent” (Lewin, 1951). Individuals are thought to behave differently according to the way in which tensions between perceptions of the self and of the environment are worked through. In order to understand this behaviour, it is necessary to view the whole psychological field, or life space, within which people act. Within this life space, individuals and groups can be seen in topological terms using map-like representations. Individuals participate in a series of life spaces (such as the family, work, and school) which are constructed under the

influence of various force vectors (ibid.). In relation to career transitions, this means that sport and university are not only objective institutions or external conditions, but also

phenomenological experiences which influence the values and behaviour of student-athletes. In periods of transition (ibid.), which bring into play shifts in peer affiliations, changes in physical and social position, and expansion of life space into unknown regions, the individual could experience tension and conflict between various attitudes, values, ideologies, and lifestyles. The within-career transitions described in these studies could be influenced by such conflicts, as well as by athletic and scholastic development, and can be seen as a process in

which the student-athletes are adjusting to conditions of the field (ibid.; Christensen & Sørensen, 2009).

Key issues in career transitions in sport

There are a number of key issues that seem to influence and play an important part in developing successful and unsuccessful career transitions in sport, especially among student-athletes (see e.g. Wylleman & Lavalle, 2004; Stambulova, 2010; Schlossberg, 1981; 1995). These key issues are described in detail below.

Athletic identity and student identity

Elite student-athletes must by default hold both a student and an athlete role. Because both roles are enacted in the college environment, they may compete for temporal (i.e., competing or conflicting time demands) and psychological resources, which may result in role conflict. For these athletes, the athletic identity, defined as "the degree to which an individual identifies with the athlete role" (Brewer, Van Raalte, & Linder, 1993) can be an important source of perceived competence and positive self-evaluation, and may occupy such a central role in identity structure that it dominates their ego-identity (Brewer, 1993; Brewer et al., 1993; Murphy, Petitpas, & Brewer, 1996). However, many student-athletes also consider their student identity to be very important, and those who value academic concerns and achievements as highly as athletic ones are more likely to meet with greater academic success while studying, and to enjoy greater life satisfaction after graduation (Killeya-Jones, 2005).

This and other empirical work (e.g., Donahue, Robins, Roberts & John, 1993; Harter & Monsour, 1992; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995) holds that the more integrated one's roles, the more positively adjusted one will be. Research suggests that when the different parts of the self

cohere into an integrated, harmonious whole, the result will be positive well-being and psychological adjustment (e.g., Donahue et al.,1993; Harter & Monsour, 1992; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995; Killeya-Jones, 2005). For the student-athlete, then, it is a complex and

differentiated, yet integrated self-concept that should afford greater well-being and protection from threats to their sense of self in any one domain.

In the multiple self, "role conflict" can be characterised as two or more identities or roles that are mutually exclusive, or are conceived by the individual as being construed so differently in terms of the thoughts, feelings, and traits associated with each that they are irreconcilable. Moreover, one would expect that, for two such roles, there would be at least a moderate difference in the way each is evaluated, one being relatively more positive than the other. Thus, the combination of irreconcilable construals and differences in evaluation may lead to conflict between the roles and associated psychosocial discomfort. Such discomfort might manifest as maladjustment of the individual in one or both identity/role domains, and as relatively poor psychological adjustment or well-being. Conversely, "role integration" in the multiple self can be conceived of as a linked set of concordant identities that share some thoughts, feelings, and traits, and are relatively equal in their evaluation. Thus, they can be reconciled; each can be enacted without causing discomfort relative to the other. Such

integration is likely to be characterised by relatively positive psychological adjustment in each identity/role domain and by relatively positive adjustment or well-being (Killeya-Jones, 2005).

Baillie and Danish (1993) consider the label or role of athlete to be a major source of some of the difficulties that occur upon retirement. When the foundation of self-esteem from a very young age has been based on athletic excellence, the end of the athlete role can become difficult (ibid.). The process of being identified as an athlete, which is also referred to as a situated identity, may begin early and has a significant influence on social, physical, and

personal development (ibid.). Athletes who are disproportionately invested in their sport participation may be characterised as “one-dimensional”, having spent most of their effort in developing their athletic self to the exclusion of other domains; at the end of their professional sport career, they may have few options for investing their ego in other activities that can bring them similar ego-gratification and satisfaction (McPherson, 1980). In addition to the relatively early development of the athlete identity, another factor which can lead to sport-career transition difficulty is the unique public identity of an athletic identity. In relation to career exploration, individuals high in athletic identity are less likely than individuals low in athletic identity to consider thoughtfully a wide array of career possibilities prior to sport career termination (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2007). In particular, athletic identity has been positively correlated to identity foreclosure in three studies of college students and student-athletes (Andersen, 2002; Good et.al., 1993; Swank & Rudisill, 1998, in Wylleman & Lavallee, 2007). Exclusive athletic identity is associated with an increased risk of problems adjusting to sport injury, according to a series of studies by Brewer (1993). Brewer, Van Raalte, and Petitpas (2000) also found that athletic career transition affects the patterns and levels of an individual’s identity. According to Lally (2007), decreasing the prominence of athletic identities can preclude a major identity crisis or confusion upon and following athletic retirement. In a study including intercollegiate students, failure to explore alternative roles and a strong and exclusive identification with the athlete role were associated with delayed career development (Murphy, Petitpas, & Brewer, 1996).

Coping resources

Whereas many athletes adjust in a successful and satisfying way to retirement from sport, others may face severe difficulties due to a lack of coping skills and/or resources (Pearson & Petitpas, 1990; Taylor & Ogilvie, 1994). While some researchers have reported

that athletes may turn to alcohol as a way of coping emotionally with their career termination (Koukouris, 1991; Mihovilovic, 1968), others have found that keeping busy,

training/exercising, and a new focus after retirement were the most beneficial coping strategies during the first few months of retirement (Baillie, 1992; Sinclair & Orlick, 1993). The importance of social support as a major coping resource during a career transition has been studied in a number of reports, including normative (see e.g., Parker, 1994; Thomas, Gilbourne, & Eubank, 2004; Wuerth et al., 2004) and non-normative career transitions (see e.g., Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007; Woods, Buckley, & Kirrane, 2004; Wylleman,

Alfermann, & Lavallee, 2004). Social support and social support networks are important for developing informed practices (Côté, Ericsson, & Law, 2005) and facilitating athletic career transitions at various stages (Martinelli, 2000; Wylleman et al., 2004). The availability of social support networks (e.g., friends, family, team-mates) has also been shown to influence athletes’ adjustment to athletic retirement (Alfermann, 2000; Pearson & Petitpas, 1990; Sinclair & Orlick, 1993; Stambulova, 1994, 1996; Swain, 1991; Wylleman et al., 1998). In fact, social support has been asserted to be the key to an optimal athletic career transition (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2007). Furthermore, the athletic environment’s role in promoting successful career transitions has also been acknowledged by Henriksen, Stambulova and Roessler (2010). According to their research, an environment that is characterized by a high degree of cohesion, by the organization of athletes and coaches into groups and teams, and by the important role given to elite athletes can help talented junior athletes make a successful transition to the elite senior level.

Pre-retirement planning has also been shown to play an important role in athletes’ effective coping with their career ending (Gorbett, 1985; Ogilvie & Taylor, 1993). However, although retirement is an integral part of the athletic career, several authors have reported a resistance on the part of athletes or significant others in their social network to plan for career

termination (Good et al., 1993; Sinclair & Orlick, 1993; Swain, 1991; Wylleman et al., 2000)

Athletes' non-athletic transitions

In recent years the need has been underlined to broaden sport psychologists' views on career transitions so as to include those non-athletic transitions which may impact or be affected by athletes’ athletic careers (Wylleman et al., 1998). These transitions include those occurring in athletes’ psychosocial development and in their scholastic/academic career. For instance, Giacobbi, Lynn, Wetherington, Jenkins, Bodendorf, and Langley (2004) reported several sources of stress associated with the transition of student-swimmers to university, including performance expectations, training intensity, interpersonal relationships, relocation, and academic demands. In addition, Cecić, Wylleman, and Zupanćić (2004) found that both athletic and non-athletic factors have an impact upon the athletic transition, and concluded that athletic and non-athletic aspects of life interact to affect an athlete’s experience of career transition. Research into the development of the careers of talented individuals has revealed a relation between the occurrence of specific phases in the athletic career and the role and influence of the relationships in individuals’ psychological networks (e.g., Bloom, 1985; Salmela, 1994). These findings confirm the importance of the quality of relationships for the development of the athletic career, and thus for the way that athletes are able to cope with the transitions in their sports career (Wylleman, & Lavallee, 2007). While the link between career phases and specific relationships is fairly consistent for most talented individuals (Bloom, 1985), there are also some discrepancies; for example, some student-athletes perceive their parents’ influence to last longer, and the onset of the “separation-individuation” process to occur at a later age, in comparison to other talented athletes (Wylleman et al., 1998).

The relation between an athlete’s psychosocial and athletic development has been approached on different levels. In a first line of research, the development and the quality of

the interpersonal relationships constituting the athletes’ psychosocial setting were

investigated. This revealed, among other results, that among talented athletes the level of athletic achievement was linked to the quality of the athlete-father relationship (Wylleman, 1995). A second approach examined the global network in which the athlete is nested, and more particularly the family context, taking a more global perspective upon this psychosocial setting.

The developmental model of the athlete family as formulated by Hellstedt (1995) is based on the proposition that not only does a family undergo a constantly changing

developmental process, but it should also cope successfully with different major transitional tasks in order to proceed developmentally. In order for athletes to progress and cope with the different transitions in, for example, their athletic or academic career, they need to be

encapsulated in a family which copes successfully with its own developmental changes and transitions. Taking the demands of athletic competition and training into account, Hellstedt (1995) argued that unique circumstances in the athlete family might lead to deviations from the normal developmental life cycle. Both approaches underline the importance not only of the psychological and social support network in athletes’ coping with transitions in their athletic career, but also of the need for sport psychologists to look at the transitions, and their mutual relations, occurring in athletes’ psychosocial and athletic development.

Student-athletes and dual career

Another type of transition essential to athletes relates to their scholastic and academic development. The increased importance placed on the optimal development of talented athletes, as well as the concurrent occurrence of transitions in athletes’ educational and athletic settings (Wylleman et al., 1998), has brought the specificity of the situation of

their athletic career, but also with the basic transitions in their education (e.g., to college or university) and the transitions inherent to each level of education. At secondary level, these transitions include teacher-pupil relationships, choice of subject of study, academic

achievements, intra-class relationships, and a possibly delayed college decision; at higher education level they relate to adjusting to campus life, selecting a subject of study or a major, making the college team, and preparing for a post-university career. These transitions require student-athletes to adjust to and cope with challenges and changes occurring in the

combination of academics and athletics (ibid.).

Student-athletes are confronted with the duality of their situation. Today, athletes who strive to reach the highest level must also consider their post-sport career, especially if their specialisation is in individual sports. One aspect of this process is a dual career combining high performance sport and education. The dual career is characterised by a career with two major foci, in this case sports and studies, and is aimed at both athletic and academic success. It is not only important in coordinating the stages and transitions in an athlete’s athletic and academic development, but is also relevant to their psychological and psychosocial

development (Stambulova, 2010.) Conflict may arise between the role of student and athlete, or may be imposed by people around the athlete who feel that the student-athlete should choose one sphere of activity or the other; for example, coaches may feel that an athlete cannot fully concentrate on and be motivated for high-level sport if simultaneously involved in academic study. The possible causes of conflict between the dual roles are related to the need for student-athletes to excel in two domains, deemed important by society at large, during one and the same period of life (Wylleman & De Knop, 1997). This situation may induce time-management problems, restricted development of relationships, accruing pressure, and demotivation to perform at both a scholastic/academic and an athletic level. In-house psychological services in schools and universities should not only provide primary

prevention to student-athletes, but also support them in developing their career and life skills in order to provide them with the best possible means of coping at an academic, athletic, and psychosocial level. While this may include optimising student-athletes’ study, interpersonal communication, or goal-setting skills, the support provided by student-athletes’ psychological networks should also alleviate the occurrence of problems related to issues such as their living environment, identity foreclosure, injury, and overtraining (e.g., Carr & Bauman, 1996; Finch & Gould, 1996; Greenspan & Andersen, 1995; Petitpas et al., 1997).

For many student-athletes, starting college brings about a substantial psychosocial change and adjustment (Finch & Gould, 1996). Those in transition into or out of university, in particular, can be at risk of developing adjustment disorders (Andersen, 2002). The demands placed on student-athletes, such as academic pressure, travel, sport performance, and training demands usually exceed the demands experienced by non-athlete students. Student-athletes face a variety of developmental issues and have several special pressures in addition to maintaining academic eligibility (ibid.). This has also been acknowledged in a study by Christensen and Sørensen (2009), who investigated how young Danish football talents subjectively experience and describe the way they balance their relations between their interests and ambitions in the field of elite sport and the demands of elite football, and on the choices and requirements necessary for coping with the field of education.

The adaptation processes of first-year, non-athlete college students have been the subject of great interest among researchers in the educational community, because over twenty five percent of first-year college students do not return for their second year

(Giacobbi, et al., 2004). The need to balance freedom and responsibility were seen as difficult challenges (ibid.). MacNamara and Collins (2010) studied the role of psychological

characteristics in managing the transition to university among high-level athletes, and concluded that this transition is perceived as a process that needs considerable pre-emptive

work in the lead-up to the move, focusing on systemic and interpersonal resources. This line of research has also been recognised in research by Miller and Kerr (2002), whose study on Canadian student-athletes revealed that the athletes’ lives revolved around athletic, academic, and social demands, and that the athletes were forced to make a number of compromises to cope with these demands. A study of 26 student-athletes striving to reach international level found that the athletes displayed a need to develop further coping strategies, such as stress and time management, and experienced insufficient financial and scholastic support in their transition (Bengtsson and Johnson, 2010). Interestingly, Kane, Leo & Holleran (2008) concluded in their research on issues related to academic support and performance of student-athletes in the US that although challenges still persist, improvements in the graduation rates of student-athletes over the last few years appear to be the result of a variety of factors such as enhanced student-athlete academic support programs, stronger social support networks within the student-athlete community, and improved psychological support services. Another study showed that the academic performance of student-athletes is lower during the sporting season, primarily due to the demands placed on their time (Scott, Paskus, Miranda, Petr & McArdle, 2008). Research conducted in South Africa revealed that most student-athletes need additional tutoring at convenient times that will not interfere with competition and/or training times, as well as flexibility in terms of the completion of assignments (Burnett, Peters & Ngwenya, 2010). Bengtsson and Johnson (2010) similarly reported that student-athletes saw flexibility and support from the university as central in their transition to university. A study of wellness practices and barriers among university student-athletes found that the participants

experienced problems adjusting to the university setting and lacked the knowledge to address their wellness needs (Van Rensburg, Surujlal and Dhurup, 2011). The study identified several significant wellness practices including peer interaction, reading, and networking, as well as barriers such as poor time management, poor choice of company, and lack of transport. The

pressure and demands for both academic and sport performances can put significant burdens on the student’s shoulders and often leave little spare time for engagement in common student activities and socialising, which could become very stressful (Andersen, 2002, Giacobbi, et.al, 2004, Skinner, 2004) The participants in Skinner’s (2004) study were all concerned about time management in some form. This result correlates with the literature regarding balance in the lives of a freshmen student-athlete. Freshmen athlete students cannot devote much time to outside activities after their daily studies and athletic obligations have been fulfilled (Skinner, 2004).

Injuries

One of the more common reasons for a non-normative transition is injury. Athletes driven to make the transition to a higher competitive level may be at greater risk for

transition-related stress, since individuals highly identified with their sport have been shown to experience greater sport-related stress, for example, in reaction to injury (Brewer, 1993). It has also been shown in later research that individuals with a strong commitment and defined goals, which is displayed by a clear drive towards achievement of athletic goals and

motivation-related behaviour, may be more at risk for sport-related stress when faced with difficult situations such as a sport injury (e.g., Johnson, 2000). Ogilvie and Taylor (1993) conclude in their research that athletes forced to retire due to injuries had more difficulties adjusting to a post-career life. Later research by Alfermann and Gross (1998, in Wylleman & Lavallee, 2007) confirms that athletes who had terminated their career involuntarily (due to injuries) reported more negative feelings, a higher number of coping strategies, more passive strategies, and a higher need for social support in comparison to voluntarily retired athletes.

The growth in size and popularity of high-level competitive sports has to some extent coincided with a growing interest in career assistance, and more particularly, pre-retirement programs for elite athletes. Several career assistance programs have been designed in countries around the world to help resolve the conflict that many athletes face in having to choose between pursuing their sporting and post-athletic career goals (Wylleman, Lavallee & Alfermann, 1999). Career assistance is often based on a set of principles, such as "a whole career" and "a whole person" approach, a developmental and an individual approach, as well as a multilevel treatment and an empowerment approach (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). Programs are generally run by the national Olympic Committee, a national sports governing body, a specific sport federation, an independent organisation linked to the setting of sport, an academic institute, or a combination of these. While most programs address the needs of high-level athletes, some have been explicitly developed for professional athletes (Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler & Coté, 2009).

Sports career assistance programs also vary in format; they may include workshops, seminars, educational modules, and individual counselling. These formats are aimed at presenting information, educating, providing guidance, or assisting in skill-learning, and are generally relevant to topics linked to sports career transitions. The objectives of these programs, while being focused upon assisting (former) athletes competing at elite level, may vary in content and target population. There are five general topics that are covered in the major programs to some degree or another (Wylleman, Lavallee & Alfermann, 1999):

1. Social aspects: quality of relationships (e.g., family, friends) in the context of sport and of an academic/professional occupation.

2. Aspects relevant to a balanced style of living: self-image, self-esteem, and self-identity; social roles, responsibilities, and priorities; and participation in leisure activities.

occupation, financial planning, skills transferable from the athletic career, and coping skills. 4. Vocational and professional occupation: vocational guidance, soliciting (e.g., interviews, curriculum vitae/résumé), knowledge of the job market, networking, and career advice.

5. Aspects relevant to career retirement: possible advantages of retirement, perceived and expected problems related to retirement, physical/physiological aspects of retirement, and decreased levels of athletic activity. Despite the vast amount of research in the area of career transition, few studies have specifically examined athletic career assistance programs. Petitpas et al. (1992), who investigated 142 elite athletes transitioning out of sport, concluded that career assistance services must be tailored to better assist this population, with a focus on enhancement, support, and counselling. According to North and Lavallee (2004), there appears to be some reluctance among younger athletes, and those who perceive themselves to have a significant amount of time before they retire, to develop concrete plans about their future career prior to their retirement. Regarding transition out of sport, one evaluation of a career assistance program for elite athletes concluded that satisfaction levels were high, and the level of career decision-making difficulties tended to diminish in relation to the amount of time spent in the program (Mateos, Torregrosa, and Cruz, 2008).

According to Wylleman, Lavallee, and Alfermann (1999), sports career assistance programs should provide athletes with (a) clinical guidance or counselling, but more particularly, educational modules which are preventive in nature (i.e., optimising athletes’ skills and resources to cope with transitions); and (b) skills and coping resources for both transitions specific to the athletic career (e.g., retirement from competitive sports) and transitions which occur in non-athletic spheres of life but still affect the development of the athletic career (e.g., transitions in the scholastic/academic career). As pointed out by Baillie and Danish (1992), the emphasis of the sports career assistance program should be on athletes’ functional adjustment in the pre-retirement phase, while in the period of

post-retirement, the emphasis should be on the provision of support with regard to emotional adjustment.

Petitpas, Champagne, Chartrand, Danish & Murphy (1997) underline the need to consider the idiosyncrasies of the targeted sport or sports group (e.g., type of sport, nature of the competitive events in which the athletes participate), and the structural aspects of the program (e.g., group size, program format and scheduling, required or voluntary

participation). The actual content and management of a sports career assistance program should touch on the topics delineated earlier, with particular attention for athletes’ social environment. Attention should be paid to the way in which the program is brought to athletes. Program leaders should understand the composition of the participating group of athletes, anticipate potential problems, manage athletes’ emotional reactions, and skilfully use the diversity among participants as a facilitating instrument in group discussions (Wylleman, Lavallee & Alfermann, 1999; Petitpas et al., 1997; Petitpas et.al., 1992, in Wylleman & Lavallee, 2007).

Finally, sports career assistance programs should provide athletes with the opportunity to maintain the momentum of their career development via, for example, local support groups (e.g., of local retired athletes), or periodic experience-sharing meetings (Wylleman, Lavallee & Alfermann, 1999).

Summary and objective of the studies

The transition to University and dual career is coordinative stages and transition in an athlete’s academic and athletic development and in their psychosocial and psychological development (Stambulova, 2010). It is evident from the literature that a within-career

transition to University and a dual career affects athletes from a within- as well as an outside-sport perspective. The years spent at university are important for reaching the higher level in

sport while gaining a university degree. Student-athletes at the national elite level have already undergone a number of career transitions, and are likely to be close to the peak of their athletic careers. For many national elite level athletes, this coincides with other, non-athletic, career transitions that demand attention; in this case, a dual-career transition.

The time spent at University while striving to reach a higher level in sport can provide the student-athletes with the opportunity to develop their athletic skills while undertaking an academic education. Dual career and lifestyle issues include overcoming barriers and

demands relating to career decision-making, time pressures and pressure of combining studies, sport and other aspects of life. One limitation on earlier research in sport is that it has focused on individuals transition out of sport (Alferman, Stambulova & Zemaityte, 2004; Harrison & Lawrence, 2004; Kadlick & Flemr, 2008), and to a lesser extend on how to cope with university studies and high achievement sport. Relative little is known about the student-athletes experiences during this period. Another limitation in earlier research is that although some studies have focused on the transition to university (e.g. Burnett, Peters & Ngwenya, 2010, Giacobbi et al., 2004), there is a shortage of these types of studies in Europe, and especially in Sweden. There is also a clear shortage of studies that has concentrated on the transition for the length of a university degree (e.g. bachelor degree, 3 years full time study). A fourth limitation in earlier research is the lack of combined theoretical assumptions

underlying dual career transition, there is shortage of studies that combine an athletic career descriptive model (e.g. Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004) and a career transition explanatory model (e.g. Schlossberg, 1981). Consequently, it is important to understand this adaptation process and to examine how student-athletes cope with the transition demands of a dual career, because of its influence on successful and unsuccessful within-career transitions.

The aim of the first study was to examine the experience of national elite-level student-athletes striving to reach the international elite level, during a normative within-career transition.

The aim of the second study was to examine the experiences of national elite-level student-athletes striving to reach the international elite level, during a dual career transition.

Method

The assumption in these studies was that a qualitative design was appropriate for studying student-athletes’ career transitions due to the underlying naturalistic paradigm’s ontological notion that numerous and subjective realities do exist and that, epistemologically, it is possible to acquire knowledge by examining people’s life worlds. However, as Allwood (2011) points out, the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research is abstract, and sometimes appears unclear and problematic. Allwood (2011) argues that an alternative to classifying research methods is to specify them at a more concrete and specific level, which may be the best approach in the context of specific types of research problem. Hence, the methods in this study consisted of narrative interviews, which are based on the assumption that people give meaning to events by telling stories (Clandini, 2007), and thematic content analysis (Baxter, 1991). Content analysis employed in this way has its roots in literary theory, the social sciences, and critical scholarship (Krippendorff, 2004), and has been commonly used in health and sport psychology research (Chamberlain & Murray, 2008; Smith & Gilbourne, 2009).

Participants

approached a normative within-career transition. That is, a purposive sample was chosen, to be able to explain some of the issues of the transition (Gratton & Jones, 2004). All the athletes were, at the time of data gathering, enrolled in a career assistance program in Sweden, which presupposed that the athletes were at a national elite level in their sport. The athletes all participated in individual sports: canoeing (4), badminton (4), squash (1), athletics (9), swimming (2), taekwondo (2), rowing (1), boxing (2), and triathlon (1), and were between 19 and 28 years of age (mean age 22.5 years, SD 2.6). The athletes had been competing in their sport for an average of 10.3 years (SD 3.8). They spent about 20 hours per week on training (SD 4.2), and had been competing at the senior level for an average of 4 years (SD 2.8), although some of the athletes were still competing in junior sports as well. The participants had recently made the transition to university, and were at the time of the interview novices at the university.

Participants in the second study were sixteen Swedish student-athletes, 8 men and 8 women, which were contacted, to gain understanding of the process by which the athletes approached a normative within-career transition, in their dual career. Again, a purposive sample was chosen, to be able to explain some of the issues of the transition (Gratton & Jones, 2004). At the time of data collection, ten of the athletes were enrolled in a career assistance program in Sweden, in which the other six had previously taken part. The athletes were at a national elite level in their sport, and had applied and been accepted into the career assistance program for the duration of a year. The athletes all participated in individual sports: canoeing (4), badminton (2), squash (1), athletics (4), swimming (1), taekwondo (1), rowing (1), boxing (1), and triathlon (1), and were between 22 and 30 years of age (mean age 24 years, SD 2.4). The athletes had been competing in their sport for an average of 12.6 years (SD 3,7), and spent about 20 hours per week on training (SD 4.4). The participants had been studying at the university for an average of three years (full-time). Four of the participants had

recently earned their degree, and were at the time of the interview no longer students at the university.

The career assistance program

The original purpose of the career assistance program, which athletes from both studies were involved in to a certain extent, was to be a bridge in the career transition between junior and senior sports when the athletes had left upper secondary school. The support was multidimensional and based on three types of support: tangible, informational, and emotional. The career assistance program included a number of specific support functions. These support functions were A) Medical support, which meant access to health care staff if necessary; doctor, nurse, physiotherapist. B) Physiological support, which meant physiological testing and training advice. C) Sport psychological support, which meant access to a sport

psychologist and psychological skills training. D) Nutritional support, which meant access to a nutritionist for advice and nutritional registration, and E) Career counselling support, with focus on studies and/or upcoming vocational career. The support was limited to

approximately 25 hours based on a financial scholarship, from which the athletes could divide

and choose among the support functions.!

Procedure

Potential participants were contacted by the researchers through a meeting that had been set up to provide information about the study. In this meeting, the purpose and rationale behind the study were explained, assurances of confidentiality were given, and the upcoming interview process was described. The potential participants were also presented with an information letter and a consent form, and were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study. Participants signified their agreement to participate in the study by returning the

completed consent form. The participants also provided the approximate date at which they felt their transition to international elite level commenced, this being indicated by their first major international competition. The study was approved by the regional ethical review board serving universities in the south of Sweden. All interviews were conducted by one of the authors (same author in each case). Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, and was digitally recorded to provide an accurate record.

Interview guide

In both studies, a semi-structured interview guide was developed, focusing on the conception and process of operationalising knowledge in content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004; Kvale, 2007). The interview guide was developed to allow the interviewer to explore the experience of the transition as experienced by the participant, and in this regard drew on the conceptualisation of human transition as defined by Schlossberg and colleagues

(Schlossberg, 1981; Schlossberg et al., 1995). Open-ended questions pertaining to psychosocial and academic influences were also included, included and grounded in!the developmental model of transition faced by athletes (Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). The interview guide was pilot-tested with two athletes of the same level as the participants, resulting in only minor changes.

The interview questions in the first study were all related to a) changes experienced in the transition (perceptions of the transition, degree of stress, concurrent pressures, and

transition changes); b) career assistance (perceived support and expectations); c) resources for adjusting to the new level in sport (sport/life balance, perception of the impact of the

transition on their psychological skills, and readiness for competition); d) satisfaction with their current situation (inside and outside of sport); e) strategies for adjusting to the new level in sport (perception of social support and development of athletic skills).

The interview questions in the second study were all related to a) changes experienced during the dual career (perceptions of the transition, degree of stress, concurrent pressures, and transition changes), b) career assistance (perceived support and potential support), c) perceived life situation (sport/life balance, perception of the combination of sport and studies on the transition, and readiness for competition), and d) strategies for adjusting to a dual career (perception of support and development of athletic and scholastic skills).

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim. The data were analysed using thematic content analysis, progressing from an inductive to a deductive process. Content analysis is used to make replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use (Krippendorff, 2004), and is therefore well-adapted for this study. In the inductive phase, new themes were drawn from the interview transcripts, while in the deductive phase, pre-existing categories (based on existing research) were used to organise the quotes (Kvale, 2007). The first stage consisted of microanalysis, which involves examining the data phrase by phrase and sometimes word by word, as defined by Graneheim and Lundman (2004). Corresponding parts of the interviews were copied into a separate raw data file. Individual meaning units were then extracted and coded from the interview transcripts, in order to identify preliminary themes within the data. To ensure that the results were grounded in the data, raw data themes were derived from the data, rather than forced upon them (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). Once this first stage of coding was completed, the most frequently cited raw data themes were identified and grouped into categories that represented their meaning (high-order themes and low-order themes). The analysis thus became increasingly deductive, with links being made to existing literature. Data analysis was initiated by the authors, and subsequently verified by two senior researchers who at the time were unfamiliar with the data

and therefore able to give an unbiased opinion regarding the validity of the analysis. In instances where there was a disagreement regarding an analytic decision, interpretations were discussed until agreement was reached. To further increase dependability, two participating athletes confirmed that they recognised the findings (as suggested by Krippendorff, 2004), and all participants were also invited to read the transcribed interviews. Each category was structured as a profile, in which themes were ordered according to the number of raw data units related to them, from those with the largest number of raw data units to those with the smallest. Deductive analysis was then used again to verify the validity of the analysis, by rereading the transcripts to ensure that all identified categories were present in the data, providing a true representation of the participants’ perceptions.

Results Study 1

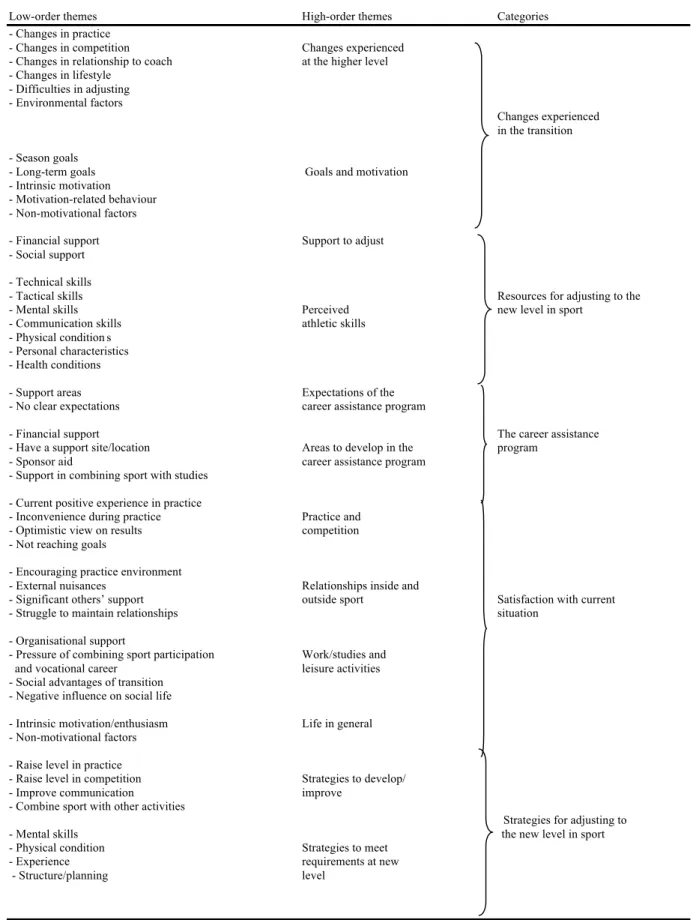

From the raw data themes, 48 low-order themes, 12 higher-order themes, and five general categories emerged. Each of these general categories: a) changes experienced in the transition, b) resources for adjusting to the new level in sport, c) the career program, d) satisfaction with the current situation, and e) strategies for adjusting to the new level in sport are presented in a temporal manner from common factors evident prior to transition and factors related to the transition phase.

[Insert Table 1 about here]

Changes experienced in the transition

The transition to higher competitive sport (international elite level) had triggered several changes in the life of the athletes, both inside and outside sport.