MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Accounting NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECT

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet AUTHORS: Julia Aspler and Elsa Axelsson

TUTOR: Emilia Florin Samuelsson JÖNKÖPING May 2020

The role of CFOs in family

business acquisitions

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and express our gratitude to everybody involved in this study. First, we would like to thank all the interview participants for taking their time despite tough times for the companies due to Covid-19. Your contribution with valuable information has made this study possible.

We would also like to express our gratitude to our tutor Emilia Florin Samuelsson who has provided us with valuable feedback and guidance throughout the process. Also, we would like to thank our seminar group for valuable input.

Finally, we would like to thank our families and friends for their continuous support.

Many thanks!

__________________________ __________________________

Julia Aspler Elsa Axelsson

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: The role of CFOs in family business acquisitions Authors: Julia Aspler and Elsa Axelsson

Tutor: Emilia Florin Samuelsson Date: 2020-05-18

Abstract

Background & Problem: Many family firms face a change in ownership in the near future.

Acquisitions of family firms can therefore be a solution for the change in ownership. Due to special family firm characteristics, acquisitions of such companies can be complicated. Previous research shows that accountants and CFOs have a positive effect on the firm’s survival and growth. However, the CFOs’ roles in family business acquisitions have not been studied before.

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to explore what roles accountants and CFOs have in

acquisitions of family firms.

Method: The base of this study is an abductive research approach with a qualitative research

strategy. The main method was semi-structured interviews that was complemented with a document study of official documents from websites.

Conclusion: The empirical findings and analysis revealed that the CFOs in family firm

acquisitions are important, but the CFOs’ roles in acquirer and acquiree differ. The CFOs in the selling family business is more of a bean counter in the process and provide material. The CFOs in the acquiring group is more of a business partner, conducting analyses and are involved in strategic decisions. The process of acquiring family firms is a special situation for the CFOs in the acquiring group since they need to adapt to the family firms’ informal culture.

Table of contents

Chapter 1 – Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problem discussion ... 2

1.3 Purpose... 6

1.4 The use of concepts and disposition ... 7

Chapter 2 - Literature review ... 9

2.1 Family Businesses - definition and important characteristics ... 9

2.2 The “traditional” role of accountants and CFOs ... 11

2.3 The current discussion about the accountants’/CFOs’ roles in family firms... 13

2.4 Succession and Acquisitions ... 14

2.4.1 Succession...14

2.4.2 Acquisitions ...15

2.5 Socioemotional Wealth ... 17

2.6 Summary and model ... 18

Chapter 3 - Method ... 20

3.1 Research Approach ... 20

3.2 Research Strategy ... 21

3.3 Data collection ... 23

3.3.1 Criteria for sample ...23

3.3.2 Selection of companies ...24

3.3.3 Conducting the interviews ...30

3.4 Data analysis ... 33

3.5 Research ethics ... 33

3.6 Research quality ... 34

Chapter 4 – Empirics ... 35

4.1 Acquisitions of family businesses - the perspective of the business broker ... 35

4.1.1 Henrik and company X’s general approach to acquisitions ...35

4.1.2 The business broker on family business specifics during acquisitions ...37

4.1.3 The business broker on the role of CFOs during acquisitions...39

4.2 Group 1 and their acquisitions of company A and B ... 40

4.2.1 Acquisitions in group 1 ...40

4.2.2 The CFO in group 1 on family business specifics during acquisitions ...42

4.2.3 The CFO in group 1 on the role of CFOs during acquisitions...43

4.2.4 The acquisition of company A - perspective of the financial manager at company A ...44

4.3 Group 2 and their acquisition of company C... 46

4.3.4 The acquisition of company C - perspective of the CFO at company C ...49

4.4 Group 3 and their acquisition of company D ... 51

4.4.1 Acquisitions in group 3 ...51

4.4.2 The CFO in group 3 on family businesses specifics during acquisitions ...53

4.4.3 The CFO in group 3 on the role of CFOs during acquisitions...54

4.5 Group 4 and their acquisitions of company E and F ... 56

4.5.1 Acquisitions in group 4 ...56

4.5.2 The business developer in group 4 on family business specifics during acquisitions ...58

4.5.3 The business developer in group 4 on the role of CFOs during acquisitions ...59

Chapter 5 - Analysis ... 61

5.1 Acquisitions and the role of the accountant/CFO ... 62

5.2 Specifics for Family Business acquisitions and the role of the accountant/CFO ... 65

Chapter 6 – Conclusions ... 70 Chapter 7 – Discussion ... 72 7.1 Contributions ... 72 7.1.1 Theoretical contributions ...72 7.1.2 Methodological contribution ...73 7.1.3 Practical contributions ...73 7.2 Limitations ... 74 7.3 Future Research ... 74 References ... 76 Appendices... 86

Appendix 1 - Interview guide – for the acquiring party... 86

Appendix 2 - Interview guide – for the acquired family business ... 88

Appendix 3 – Interview guide – business broker ... 89

Figures

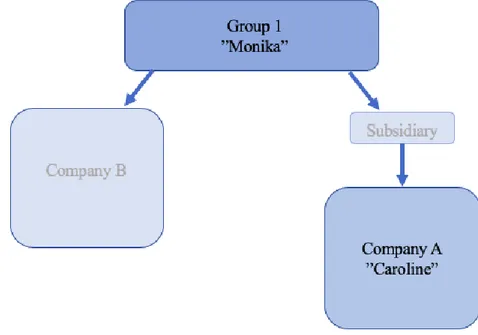

Figure 1: Literature review summary……….…....…....19Figure 2: Group 1………...26

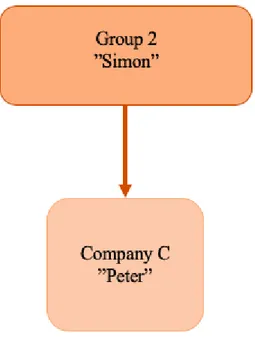

Figure 3: Group 2………...27

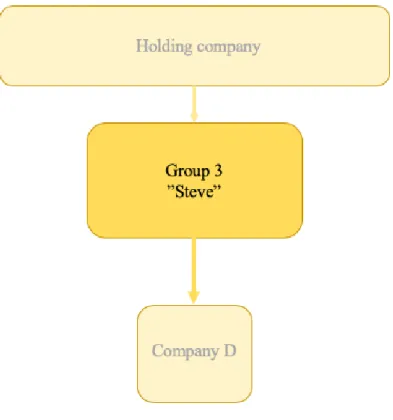

Figure 4: Group 3………...28

Figure 5: Group 4………..….29

Chapter 1 – Introduction

Chapter 1 includes a background and problem discussion of the research subject of this thesis. Further, the purpose of this study is presented with the research question. Lastly, the disposition of the thesis is provided.

1.1 Background

Many companies in the world economy are small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). They are crucial for the countries’ economies since they have a positive impact in terms of economic growth and creation of jobs. According to European Parliament (2019), 99 percent of all companies in the European Union are SMEs. The criteria for a company to be classified as a SME according to the European Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC is that the enterprise employ fewer than 250 people and that the annual turnover does not exceed EUR 50 million, and/or the annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 43 million.

Many of the SMEs in the European Union are family firms. In Sweden, family firms represent about 50-70 percent of all companies depending on what definition is used. Further, around 30 percent of all employed in Sweden are working in a family business (Family Business Network, 2020). A commonly used definition of family firms is a business governed and/or managed by members of the same family (Chua, Chrisman, and Sharma, 1999). A family firm is a complex organization that balances the relationships within and between the family, the business and the ownership (Gersick, 1997). Smaller family firms tend to have an informal way of managing the business and personal characteristics and values influences the governance rather than formal and generally accepted management systems (Gallo et al., 2004). The family firm also lowers the risk of agency problem between the owners and managers since the separation between ownership and control is limited (Jensen et al., 1976; Ali et al., 2007).

The relationships between the owners, managers and employees within the family firm creates a distinct trait but varies from business to business (Hasso and Duncan 2013). Family firms tend to commit to tradition within their family and will see their tradition as an obligation to

could enable them to generate return in the short run are not taken because they do not want to jeopardize the family’s values and future (Gallo et al., 2004). Due to the structure of the family firm, the future orientation may involve focus on surviving the business to next generations (Astrachan 2010; James 1999). In addition, the construction of the family firm may be complex because discussions about the firm may only take place between family members and information to non-family members within the company are left out or not informed in time (Blumentritt et al., 2007).

According to Företagarna (2017), every fourth SME in Sweden face a change in ownership within a time period of the next 10 years, since the owners are in or close to the age of retirement. Within these SMEs there are several family businesses that need to consider the firm’s survival and make a choice of passing on to the next generation or sell the company. For companies that are facing a challenge like this in upcoming years, the accountants or the “Chief Financial Officers” (CFOs) can have an important role in the decisions that will be made.

The role of accountants has been changing over the years. The development of technology and simplification of processes have enabled the accountants to spend time on consulting in decision making. The profession that before was merely seen as a bookkeeping service has evolved to a quasi-consulting service, which provides advice on numerous levels within the business operations in addition to pure accounting advice (Carey, 2005).

1.2 Problem discussion

Many SME family firms have a change in ownership in the near future (Företagarna, 2017). Changes in ownership for family firms may be handled in different strategic ways. Succession within the family could be an option, however that is not always the case due to reasons such as lack of capital or that the children are unwilling or unable to enter the business. Another option may be to let the business be acquired. Acquisitions can contribute with opportunities for the family business to grow and perform better but it can also be challenging (Mickelson and Worley, 2003).

Family firms tend to have other behaviors unlike those of non-family firms (Gómez-Mejía, Cruz, Berrone, & De Castro, 2011) which can affect the acquisition. The differences between

a family firm and a non-family firm can be explained by Socioemotional Wealth (SEW). According to SEW, family-owners consider non-economic aspects in addition to the economic aspects in order to utilize socioemotional wealth (Kalm & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). There exists an emotional bond between the firm and the family, and that bond has an impact on how the family firm is managed (Baron, 2008). According to Gómez-Mejía et al. (2011), the family values are important to some family owners and they want to influence the employees with those values in order to create a desirable organizational culture. The values that the family creates sometimes permeates the whole organization and it can affect the role that the employees take.

Research have shown that family firms may have a less diversified workforce than non-family firms because family members are preferred when recruiting since they probably possess the same values (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Family members usually possess firm specific knowledge, while non-family members may possess a more general perspective of businesses and contribute with other perspectives and expertise. The profession of financial and managerial accounting requires specific knowledge, which is usually only obtained by few individuals with an established accounting background. The probability that the family maintain these skills is lower due to the limited pool of employees (Barbera & Hasso, 2013). Research also shows that a non-family CFO or accountant can bring additional value and lower the financial risks of the family firm (Lutz and Schraml, 2012). Therefore, the role of the accountant or CFO can play and essential role in these kinds of businesses.

The profession of accountants and CFOs has evolved and in many organizations, they are seen as business partners rather than accountants (Siegel, 2000).It has been shown that accountants provide advice on a range of issues and that they have a positive impact on firm growth and survival (Berry et al., 2006). According to Lindvall (2017), the role that accountants take in businesses is in practice most often multifaceted and the accountants are not just a one-dimensional actor in the company. Accountants and especially management accountants can clearly be seen as valuable strategic partners for the business (Clinton et al., 2012).

Accountants in family firms may be a complex profession since the accountants have to consider the specific characteristics regarding the governance mechanisms of the specific

accountant takes within the family firm may be affected by the size of the firm, ownership structure, board structure and change-of-generation. Based on the complexity and specific characteristics of family firms the role of the accountant may differ in family firms. The profession as an accountant in a family firm can be challenging since the profession involves dealing with financial issues at the same time as dealing with more personal and relational problems, like for example emotions for and to family members. It is important to keep in mind that decisions taken in family firms can be driven more by considerations in the family than actual business considerations (Zwick and Jurinski, 1999; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). The accountant can therefore be needed to take another kind of role in a family business than in a non-family business.

Previous research has brought up the accountants’ importance for firm performance in SMEs (Chrisman, Chua, Sharma, & Yoder, 2009; Chrisman & McMullan, 2004; Gibb, 2000; Lussier, 1995; Lussier & Halabi, 2010; Lussier & Pfeifer, 2002). The profession of accountants has evolved and accounting bodies market themselves as consultants with broad business knowledge who can give advice on a numerous of issues, not only advice related to accounting (Nicholson et al., 2010). For example, SMEs often use advice from accountants when they are facing serious competition in order to attain competitive advantage (Gooderham et al., 2004). Further, accountants also provide advice on marketing and sales decision in SMEs which could increase sales (Carey, 2005). Research has shown that non-family firms differ from family firms when it comes to how they use accounting and finance practices and also in the institutionalization of these activities (García Pérez de Lema & Duréndez, 2007; Speckbacher & Wentges 2012; Duller et al., 2011).

Future sales growth depend on the survival of the firm and research has shown that general business advice generates a positive effect of firm survival (Chrisman & McMullan, 2004; Lussier & Halabi, 2010; Watson, 2007). Firm survival is an important issue for family firms and family firms that survive to the second generation is only 30 percent according to Ward (2011). Thus, family firms’ use of accountants may be beneficial for firm survival. However, there are no studies on how accountants and CFOs can be beneficial for firm survival through an acquisition. So, what roles can accountants and CFOs have? According to previous literature, the role of accountants in non-family firms can vary (Carey and Tanewski, 2016; Blackburn and Jarvis, 2010). Do they have different roles in family businesses than in non-family businesses? By having these questions in mind when developing the research question,

the authors aim to contribute with further knowledge about accountants and CFOs in family firms.

Acquisitions include planning and information needs to be distributed to stakeholders. It is important to do this right in order to succeed with the transaction. According to Braun (2001), many acquisitions fail due to that the leaders of the transaction fail to include the most crucial aspects of the organization. If the acquisition would be considered as successful is based on the financials and therefore the accountants/CFO could have a crucial role in this situation (Allison, 1984). The CFOs/accountants have a view of the organization’s financial status and therefore they can an important actor in acquisitions.

As mentioned before, accountants and CFOs have developed to often be described as a business partner rather than just an accountant/CFO. However, in family firms it may be hard to take that role since the business requires knowledge about the family’s way of handling their issues and affairs. Hence, there are limited research on the accountants’ role in family firms (Salvato and Moores, 2010; Duller et al., 2011; Hiebl, 2012). Previous research has shown that the accountants’ profession is constantly changing and therefore the subject is current. The empirical evidence needs to be updated frequently since the profession is continuously changing in practice. Due to the special dynamic within the family firm the ownership succession is a critical situation for a family firm where they have to decide whether to pass on to next generation or to get involved in acquisitions. Therefore, the authors investigate in this study what role the accountant and/or the CFO have in the situation of an acquisition.

1.3 Purpose

Research and engagement within the subject of family businesses has grown and become more rigorous during the last two decades (Sharma et al., 1997 and Litz et al., 2012). However, this field of study is still emerging (De Massis, et al., 2008) and due to the family firms’ big part in the world’s economy and their performance, it is a subject worthy of exploration. Two of the topics getting increased attention is the role of the accountant and the CFO. Attention will be directed to this issue in this study.

The purpose of this study is to explore what roles accountants and/or CFOs have in acquisitions of family firms.

By examining this subject, the authors hope to contribute with important insights, both to practice and theory. The study can contribute to family business research by understanding the roles accountants/CFOs can have in the important situation of succession in family businesses.

The practical contribution of this study will generate information and knowledge to accountants’ and CFOs’ roles in family firm acquisitions and different actors’ perceptions. Further, this study will contribute knowledge about acquisitions of family firms and the process before, during and after.

In order to fulfill the purpose, a research question have been developed and the study intend to answer the following question:

RQ: What are the possible roles of the accountants/CFOs in the case of a family business

acquisition?

When answering the research question a discussion will be held about the aspects that can affect the roles and possible differences.

1.4 The use of concepts and disposition

Throughout this thesis titles like CFOs and accountants are used. However, the authors are aware that there are other actors as well that are included to make a company’s financial department work. When a discussion is held about the titles CFOs and accountants it includes corresponding titles that are engaged in the role of the financial department.

The thesis is outlined with seven chapters as followed:

Chapter 2

This chapter presents a review of the literature within the research subject. The literature review presents family business specifics, the “traditional” role of accountants, acquisitions and socioemotional wealth. The chapter ends with a summary and a model which is used as a base for this research.

Chapter 3

Chapter 3 presents the method used in this study. The chapter aims to explain how the thesis was performed and discuss the choices made of theory and research strategy. The chapter will also explain how the empirics was collected and a presentation of the participants is provided. The chapter also includes information on how the data is analyzed and it ends with a discussion of research ethics and quality.

Chapter 4

The fourth chapter presents the collected empirical data, both from the interviews and documents. The chapter is divided into sections of each group. The presentation of the relevant empirical data is divided into the themes “acquisitions”, “family business specifics” and “role of CFOs”.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5 provides an analysis over the empirical data and the literature presented through the model in chapter 2. The chapter is divided into the themes (1) Acquisitions and (2) Specifics for family business acquisitions.

Chapter 6

In chapter 6, conclusions of the thesis will be presented. The conclusion aims to answer the research question based on the empirical data and the analysis.

Chapter 7

In this chapter a discussion about the contributions of the study will be held. This will be followed by a discussion about implications, limitations and suggestions for future research.

Chapter 2 - Literature review

In this chapter, the theoretical framework is presented. It is based on previous research and literature. The first section presents the definition and important characteristics of family firms. Then a presentation of the “traditional” role of accountants in general and in SMEs is presented, followed by the current discussion of the accountants’ roles in family firms. Thereafter, a review of research and literature of succession and acquisitions and a section of the theory Socioemotional Wealth follows. Lastly, a summary and a model of the study.

2.1 Family Businesses - definition and important characteristics

There exist various definitions of family firms in the existing literature. A commonly used one is by Chua, Chrisman and Sharma’s (1999):

“The family business is a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families”.

Since this study focuses on acquisitions of family business, this section is relevant in order to understand specific characteristics that family firms possess. It is a prerequisite to understand since the study analyzes the specific situation of acquisitions of family firms.

When looking at differences between family firms and non-family firms, it is possible to distinguish the family firm from the non-family firm based upon different characteristics. Firstly, the family businesses have the unique characteristic that they possess two types of social capital at the same time even if they work as a single entity; the firm’s and the family’s (Arregle et al., 2007). Secondly, family firms tend to show inherent attributes which is derived by the overlap of ownership, business, and family. These overlaps result in the distinguishing features of family businesses. (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996; Gersick, 1997). Third, family businesses are known for being entities that are heavily driven and affected by emotions (Kalm & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). Family companies have the willingness to seek for both non-financial and

their socioemotional wealth (SEW) (Reay, Pearson, & Dyer, 2013) which will be explained further in section 2.5 “Socioemotional Wealth”.

Social capital is defined by Arregle et al. (2007) as “the relationships between individuals and organizations that facilitate action and create value”. The family business is unique in the way that the organization’s social capital often is influenced by the family’s social capital.

Attributes of the family firm can be explored from three overlapping systems, ownership, business and family. The system of ownership is a category for those persons who own shares in the business. Discussing the system business refers to how the company is managed and the family includes all members of the family even though they may not be a part of the ownership or the business (Gersick, 1997).

The three systems can be explained by categorizing persons into the different categories and from that see that the complex relations between the different categories. For example, one person can be a family member and an owner but not an employee in the business, and therefore the person only overlaps the two systems: ownership and family. However, there can also be persons that belongs to all three system while other persons can belong to two system or only one. The overlapping systems can therefore explain why family firms are a complex phenomenon (Gersick, 1997).

When the discussed characteristics above are handled properly, they will successfully affect the business performance. On the other hand, if they are not handled in a proper way, they can instead harm the company (Zattoni, Gnan & Huse, 2015). Therefore, the characteristics can be important to have in mind during an acquisition in order to make it successful.

2.2 The “traditional” role of accountants and CFOs

Most companies need an accountant with specific knowledge in order to fulfill Swedish law. Nandan (2010) argue that it is equally important for SMEs as for larger firms to have sophisticated and formal accounting functions in order to enhance customer and owner values and also to manage scarce resources better. The literature discusses the role of accountants in two ways, in general and in SMEs. Even though most companies are in need for an accountant, there are no definition by law of the supposed role an accountant should take in a business. However, there are several empirical studies about what kind of role an accountant in SMEs are expected to have. The traditional role of accountants is no longer to deal with only transaction-based tasks. Instead, the role has emerged to become a more proactive role and the accountants are more involved in strategic and resource management decisions (Baxter & Chua, 2008; Clinton et al., 2012; Scapens, 2006).

Studies show that SMEs rely mostly on the bank and the accountant in order to pursue their businesses. A reason for SME’s need of the accountant is because they need to constitute several financial reports both monthly and/or quarterly such as budgeting, cash flow statements and management accounts (Collis and Jarvis, 2002). Further research also show that SMEs use accountants as the dominant source of advisors and the impact of these advices are important (Bennett and Robson, 1999). Several studies have found that advice from accountants have a positive impact on firm growth and survival (Berry et al., 2006; Chrisman, Chua, Sharma, & Yoder, 2009; Chrisman & McMullan, 2004; Gibb, 2000; Lussier, 1995; Lussier & Halabi, 2010; Lussier & Pfeifer, 2002).

Accountants are reported by several studies to be the most frequently used professional advisor in SMEs (Kirby et al., 1998; Bennett and Robson, 1999; Gooderham et al., 2004; Carey, 2005; Blackburn and Jarvis, 2010; Stone, 2011, 2015; Berry et al., 2006). The research by Berry et. al. (2006) found that a significant source of professional advice were accountants. They found that 70 percent of the respondents in their sample used their accountants for statutory advice. Further, their research also showed that 33 percent saw the accountants’ role as a source for business management advice. A smaller percentage of 31 percent answered that the accountant is engaged in financial management support work. At last, it was only 4 percent of the respondents that engaged the accountant as a management team player.

However, the accountants’ own self perception of their role in larger firms is a more advanced accountant role (Hiebl et al., 2012). In other words, they perceive themselves more frequently as advisors, business partners or business analysts than the former role as a bean counter or bookkeeper (Hiebl et al., 2012; Siegel, 2000). Moreover, the literature highlights that there is a variation in the type and level of accounting advice (Carey and Tanewski, 2016; Blackburn and Jarvis, 2010), but the SMEs may use advice from accountants when they are facing serious competition in order to attain competitive advantage (Gooderham et al., 2004) and advice on marketing and sales decision in SMEs, which could increase sales (Carey, 2005).

Previous research show that owners of SMEs, in addition to routine compliance services, expect advice on specific aspects such as financial planning, cost reduction, succession planning, and pricing decisions from their accountants (Alam & Nandan, 2007; Nandan & Ciccotosto, 2014; Ciccotosto, et al, 2008). According to Cillier (2007), the board of directors expects the CFO to be a part of all major decisions, including evaluation of investments and acquisition strategies. In fact, having a CFO as a member in the strategy team for acquisitions from the beginning to the end of the acquisition increases the likelihood of it being successful (Braun, 2001; Mavhiki, 2013).Hence, the accountants and CFOs are in practice multifaceted actors in the businesses (Lindvall, 2017).

A 15-year prediction by the American Institute of Certified Practising Accountants (AICPA) in 2011, follows that the profession of accountants will change in the future and will no longer be defined by traditional services. Hence, AICPA predicts that the profession will vary and be diverse, so the traditional services will not represent the profession anymore (AICPA 2011). Further, directions from AICPA ensues that in the future, the accountant should be a more rounded “trusted business advisor” (Hartstein, 2013).

2.3 The current discussion about the accountants’/CFOs’ roles in

family firms

Finance and accounting policies in family firms are expected to be less formalized since arrangements and commitments more often are made orally instead of in writing, which also is a result of mutual trust between the family members (Duller et al., 2011). The decrease of expectation for usage of financial management practices in family firms results in fewer resources assigned to accounting in family firms (Hiebl, 2012).

Several empirical studies have investigated how family firms adopt specific financial and accounting techniques and practices. In these studies, it was often found that family firms use less sophisticated finance and management accounting practices than non-family firms do (Speckbacher & Wentges, 2012; Di Giuli et al., 2011; Hiebl et al., 2011; Lutz et al., 2010). However, the differences between non-family and family firms regarding financial and management accounting practices was reduced when the family firm had a non-family manager, like a CFO, on the firm’s executive board (Di Giuli et al., 2011; Lutz et al., 2010; Filbeck & Lee, 2000). Another aspect that can affect the differences between non-family and family firms are the size; the greater the size of the family firm, the less differences when comparing to non-family firms (Speckbacher & Wentges, 2012; Hiebl et al., 2011).

Hiebl et al (2012) compared the accountants’ role in large family firms and large non-family firms. In this research they did not find a significant difference between the accountants’ role in family firms and the accountants’ role in non-family firms. A reason for this may be due to their choice of the size of the firms they chose to investigate since they also concluded that resources specific to family firms decreases when the family firm is growing. However, the research by Hiebl et al. (2012) also show that accountants in large family firms may more often be the drivers of change than in non-family firms and that they take a less traditional role than their peers in non-family firms.

According to Gurd & Thomas (2012) research about the role of the CFO in small and medium sized family firms, they stated that if family firms use the CFOs capabilities more and not only the bookkeeping service the firms will perform better. Their research also show that it is possible that CFOs were selected in order to stick with the bookkeeping because the family

accountants might be expected to have more of a bean counter role than in non-family firms, focusing on accounting tasks and core finance (Hiebl, 2012). Hence, according to the authors the opportunities that the CFO can contribute with are not fully utilized and the family firm are not using their resources efficiently.

Regarding the resources that is used in family firms and what role accountants and financial managers have in family firms, the literature is very limited (Hiebl, 2012). Although, there is evidence that family firms do not have specific departments for management accounting to the same extent as non-family firms have (Hiebl, 2011). This can be a result of that non-family firms rely more on finance and accounting practices than what family firms do (Hiebl, 2012). Further, empirical results show that non-family CFOs in family firms foster the professionalization and introduces more sophisticated financial management techniques, together with reducing the family firm’s financial risks (Lutz et al., 2010). According to Caselli and Di Giuli (2010), a non-family CFO is a good complement to the family “Chief Executive Officer” (CEO) since this management configuration shows admirable performance.

2.4 Succession and Acquisitions

2.4.1 Succession

As mentioned in the background to this study, many family businesses face a change in ownership. In the family business literature, succession within the family, intergenerational succession, is widely discussed and therefore this can generally be perceived as an obvious way to handle the issue of change in ownership (Gaumer and Shaffer, 2018; Daspit et. al., 2016). However, research show that the rate of family firms that survive to the second generations is low, and from second to third generation it is even lower (Ward, 2011; Allio, 2004). Researchers have discussed the explanation for the low survival rate of family firms. Massis et. al. (2008) discuss that the potential successors within the family may not hold the knowledge that is necessary to take over the business. Further, they also discuss that the heirs could lack motivation and therefore are unwilling to continue with the business. The transition from one generation to the next may not be possible due to financial aspects. All heirs may not be willing to stay within in the family firm and want to sell their shares. However, the other heirs may not have the financial abilities to purchase the shares (Massis et. al., 2008).

2.4.2 Acquisitions

An alternative to intergenerational succession can be acquisitions. Acquisitions can work either as a defensive or an offensive way for firms that have an important choice to make regarding their future. In the defensive way acquisitions can be an efficient approach to exit and in the offensive way acquisitions can increase value, establish a competitive advantage and meet the shareholders’ requirements (Mickelson and Worley, 2003). Nevertheless, acquisitions is a complex situation for all companies, especially when it involves family firms (Hussinger and Issah, 2019).

The decision to accept an offer to be acquired or to acquire another company might depend on the ownership structure of the family firm (Caprio, Croci and Del Giudice, 2011). According to previous research (Franks et al., 2010; Barca and Becht, 2001; Faccio and Lang, 2002), both the size of ownership by the family and the character of the owner may be related to if a family firm would make a decision to accept a takeover offer or not. For instance, major managers/owners that are self-interested are more likely to turn down an offer if it would risk their position or that the private benefits for them is less. At the same time, the same managers/owners would see the same offer as favorable if it would generate in a desirable position for them (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986). According to previous research (Graebner and Eisenhardt, 2004; Graebner et al., 2010; Dalziel, 2008), the owners of the selling firm is not always looking for the highest offer. Instead, priorities may be to find an acquirer that can ensure survival for the firm in a long-term perspective or that their employees benefit from the acquisition.

Acquisitions in general is a complex situation because it is a change that involves several actors and the outcome is unpredictable and uncertain. Research shows that acquisitions for the internal employees can cause stress and anxiety since the future is unforeseeable (Dackert et al., 2003). For the overall organization, it can be difficult in a situation of an acquisition because the company that is being acquired possess a culture that needs to be introduced to the new culture in the acquiring company and this can cause tension (Stahl & Voigt, 2008).

Research on acquisitions of family firms are limited. However, Mickelson and Worley (2003) found that acquisitions of family firms can differ from other acquisitions since family

reflects the three systems in the family firm as mentioned in section 2.1. Moreover, the complexity of acquiring a family firm, in addition to the financial aims, can be the emotional objectives that the family firm values (Mickelson and Worley, 2003; Astrachan and Jaśkiewicz, 2008).

Some researchers have discussed potential key factors for an acquisition to be successful in general and how to overcome some difficulties. Mickelson and Worley (2003) argue that the dominant key factor for a successful acquisition is to meet the financial expectations, for example targets of revenue and profitability and increased shareholder value. However, they also discuss other factors that is important for the acquisition to be successful, e.g. goals for integration, how to utilize the skills and knowledge the firms possess and recognize and respect cultures. One tool to overcome the difficulties is to establish a sufficient plan in the pre-acquisition process. Planning is crucial because it can ease the process in terms of developing common goals and strategies. Further, planning can also be helpful to predict and handle problems that occur along the way (Ahammad and Glaister, 2013).

There are several key factors to account for if the acquisition will turn out successful or not. Some of the key factors discussed in the literature are related to the financials and therefore the CFO may have an important role in acquisitions. Moreover, the special practices within the family firm may add more complexity to a situation of an acquisition. For example, the three circle model mentioned in section 2.1 can be one way to explain how acquisitions of family firms may be more complex. The next section will discuss Socioemotional Wealth as an additional way of explaining why family firms can act in a certain way.

2.5 Socioemotional Wealth

The concept of SEW has been frequently applied in family firm literature lately and is based on Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007) research about family firm behavior. The concept claims that family firms might make decisions driven by preserving SEW and the decisions are not always economically rational (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011; Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Berrone, Cruz, Gómez-Mejía, and Larraza-Kintana, 2010). Examples of sources that family firms can derive socioemotional wealth from are if family members work for the company, emotional attachment to the company, and if the family name is associated with the company (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). The non-economic utilities that the owner family achieves from the decisions are defined as affective endowment or SEW (Berrone et al., 2012).

The decisions by family firms that are based on endowment of socioemotional wealth can sometimes be seen as unprofessional to outside observers. Example of such decisions can be to appoint an unexperienced family member as a manager of the firm. However, these decisions generate nonfinancial benefits to the family business. The family firm’s ambition to retain socioemotional wealth influences the family firm’s long-term goals and performance, both negatively and positively (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011).

The emotional bond that is formed when the owners of the family firm derive socioemotional wealth affects how the company is managed by the family-owners (Baron, 2008). As a result, the values of the family-owners will influence the employees through long-term development plans instead of short-term plans. Identification with the firm for the employees increases with a long-term plan and it also strengthens the SEW of the family (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). The SEW can therefore be preserved even after an acquisition.

The SEW concept helps us to understand the family firm’s strategic targets and motivations that drives their actions (Astrachan and Jaśkiewicz, 2008), as well as it serves an important differentiation criterion from non-family firms (Chua et al., 2012; Chrisman et al., 2004). Previous research has discussed SEW in accordance to the willingness of taking risks. Some researchers argue that family firms are less likely to make decisions that involves a high risk in order to maintain their SEW, while others argue that family firms are willing to take high financial risks in order to preserve their SEW (Kalm & Gomez-Mejia, 2016), e.g. the decision

According to Berrone et al. (2012), “SEW is the single most important feature of a family firm’s essence that separates it from other organizational forms” (Berrone et al., 2012: p. 260). However, Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2014) discuss that SEW can be applicable in non-family businesses as well. Research have shown that entrepreneurs venturing contribute to their emotional satisfaction and that rapid growth can preserve their social status and identity (Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Lester, 2011). Further, Healy & Wahlen (1999) found that CEOs of large firms tend to take less risks in order to have stable earnings because they want to build up their reputation as skilled managers.

2.6 Summary and model

In Figure 1 below, a conclusion about the discussed topics from the literature review is presented, in order to summarize and get a picture of the different roles and what factors that could influence the CFOs roles in family businesses in the case of an acquisition. The discussed topics in the literature review have been integrated to give a background on previous literature within the field and this research is the foundation of the approach to fulfill the purpose of this study.

By reviewing the existing literature about family businesses, a conclusion can be made that family firms are assumed to possess a unique set of characteristics. Family firms differ from non-family firms in terms of that they have informal practices in various aspects. Further, the literature discuss that family firms have other aims in addition to financial goals, which can be an explanation to why family businesses sometimes make decisions that are not always economically rational. This could be explained through SEW. The literature indicates that the process of acquiring a family business may differ because the selling owners might have other goals than financial with the acquisition.

The accountants and CFOs role in family firms is a subject that is not fully explored, and further research is therefore needed. The role of accountants and CFOs in general are an important resource for the company and the role have been emerging from a bean counter to be seen as an advisory function for the business, more like a business partner. However, the role that a CFO takes in a family firm is not a widely discussed subject. The research that explores the

role in family firms can be summarized to that family firms may not use the resource and experiences of the CFO efficiently and the accounting departments in family firms do not exist to the same extent as they do in non-family firms.

When an intergenerational succession is not possible in a family firm, acquisition is an option. Acquisition is a complex situation in general and the role and the tasks of the CFO can ease the acquisition to be successful throughout the process. Since the family firm has a unique governance and decision-making styles, the process of an acquisition tend to become even more complicated. Therefore, the authors expect the CFOs’ roles to be heterogeneous and vary between different family firms and different acquisitions. Overall, the literature indicates that the CFO has an important role in an acquisition process and can be a part throughout the whole process.

Chapter 3 - Method

This section presents the method of the thesis. It first discusses the abductive research approach and the qualitative research strategy of interviews. Further, it includes data collection, selection and presentation of the interviewees. Thereafter, explaining how the interviews were conducted and the data was analyzed. The chapter is ended with research ethics and quality.

3.1 Research Approach

The problem of relating theory to practice is one of the most crucial problems in science. There are different concepts that specifies the ways the researchers can act in order to relate theory to empirics; deduction, induction and abduction (Patel and Davidsson, 2019).

The deductive reasoning starts with a general statement or hypothesis deducted from theory and then test this in practice to see if the theory is confirmed (Patel and Davidsson, 2019; Grønmo and Winqvist, 2006). The opposite to the deductive reasoning is the inductive reasoning, which make conclusions and base explanations or theories upon observations (Patel and Davidsson, 2019; Grønmo and Winqvist, 2006). The third way of relating theory to empirics is the abductive reasoning. This is an approach with characteristics from both deduction and induction in the way that a proposal for a theoretical structure (inductive reasoning), is tested in other circumstances (deductive reasoning) (Patel and Davidsson, 2019).

The research approach in this study is most comparable with the abductive approach since already existing knowledge within the subject of the accountants’/CFOs’ role in family businesses will be advanced with observations of practice. An interaction between induction and deduction will emerge because already existing theories will guide the collection of empirical data. The abductive reasoning is useful when the goal is to explore new phenomena (Meyer and Lunnay, 2013), which is suitable for this study since it explores a field where the existing literature is relatively scarce or non-existing. However, there are disadvantages with the abductive reasoning, such as the authors being affected by their previous experiences (Patel and Davidsson, 2019). Nonetheless, all individuals are in some way affected by their experiences. The authors of this study are well aware of this and the reasoning will be based and supported on empirics and previous research within the subject only. Conclusions will be conducted with considerations from previous research of the CFOs’ roles in family firms and

acquisitions together with the collected empirics. The abductive research approach also decreases the probability for the study to be limited, which is the risk if only an inductive or deductive reasoning is used. Also, the abductive approach is best suited when knowledge about a specific phenomenon is limited (Patel and Davidsson, 2019). Therefore, the abductive reasoning is the best research approach for this study in order to achieve the most accurate result as possible.

3.2 Research Strategy

The strategy that is chosen is associated with the chosen research approach as well as the underlying philosophy. The abductive approach can be connected to the philosophy of interpretivism which means that the authors want to explore and understand a certain situation (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The purpose of this study is to explore and because of the formulation of the purpose, the research is in line with interpretivism rather than positivism.

The research strategy depends on what the authors want to find out and what strategy that is possible for the study. The quantitative strategy proceeds from statistical numbers while the qualitative strategy proceeds from words (Patel and Davidsson, 2019; Bryman, 2016). There are advantages and disadvantages with both strategies. One of the major advantages with the quantitative strategy is the potential to include a large sample, which can make the result statistically generalizable. However, it does not give an in-depth explanation and understanding as the qualitative strategy can do.

The expressed purpose of this study is to explore what roles an accountant and/or CFO have in acquisitions of family firms. Therefore, a qualitative research strategy is better suited to the purpose, since a qualitative research strategy enables the authors to get a deeper understanding of the role the accountant and/or CFO can have in this specific situation (Patel and Davidsson, 2019). The qualitative strategy allows the authors to find knowledge of importance which is not mentioned and noticed in the previous literature. However, a criticism to the qualitative strategy is the problem of generalization (Bryman, 2016). This study focuses on understanding a situation and the problem on how to generalize the findings to other settings and to the whole population will remain. However, the findings of this qualitative research seek to be

generalized to theory hence, the theory in this research could be used in other sets of circumstances (Bryman, 2016; Collis & Hussey, 2014).

The primary source of data in this study will be interviews. Therefore, focus will be put on descriptive data, such as the actor's perceptions and statements (Patel and Davidsson, 2019; Olsson and Sörensen, 2011) rather than statistical relationships. This causes the study to concentrate on interpretation and a descriptive process of analyzing and therefore a qualitative case study with semi-structured interviews is conducted. In addition to the main method of semi-structured interviews, the study is complemented with a document analysis of what is said about the acquisitions in official documents. The official documents include different types of news about the acquisitions and mainly the information was found on the companies’ websites. A reason for this is to get a view of what is written about acquisitions officially and to prepare for the interviews. Another part of the document study is an examination of the different parts in a request list for due diligence. This request list became available during one of the interviews and it was studied to understand the documents requested in an acquisition process of Swedish companies. However, this request list is confidential information and therefore the

authors cannot include it as an appendix to this thesis. The document study is a way to

triangulate the situation and to increase the credibility to the research. However, the systematic analysis of this study will be based on the data gathered in the interviews.

Due to the current circumstances of Covid-19, the research strategy has been adapted during the process. The access of participants for the interviews were limited because of the social distancing and the economic crisis that Covid-19 resulted in. Therefore, the authors had to open up for other possibilities of participants in terms of other actors instead than only the parties acquirer and acquiree. This possibility enabled the study to get a wider perspective of the subject.

There are different types of interviews; structured, unstructured and semi-structured. The difference between them is how the questions are being asked and how the answers are predicted (Patel and Davidsson, 2019). In the structured interviews, the goal is to ask exactly the same questions to each respondent and therefore the questions follow a specific schedule, hence the aim is to get the interviews as equal as possible. The unstructured interviews on the other hand, does not follow any schedule and therefore the respondents may answer the questions more freely (Bryman, 2016). Neither of these approaches are appropriate for the

explorative purpose of this research because the authors aim for an in depth understanding. Through a structured interview this would be hard to achieve since it does not enable the interviewer to ask further questions. The unstructured interview would not be appropriate to the purpose of this study since the answers would be hard to compare with each other.

Therefore, semi-structured interviews are conducted in this study, which is a combination of the two types above mentioned interviews (Patel and Davidsson, 2019). The reason for this is because the respondents can contribute with answers that is unexpected, but still can be very valuable for a deeper understanding. The interviewer in a semi-structured interview can also add further questions in addition to the questions in the schedule, if necessary, to reach data saturation. This means that the semi-structured interviews can be a flexible way to get a deeper understanding. The schedule for the questions in this study can be found in Appendix 1-3.

A relationship between the interviewer and the respondent should be established before the interview, which means that the interviewer should achieve rapport with the respondent. If

rapport is achieved to the respondent, the respondent is encouraged to participate in the

interview. However, if rapport is not achieved the respondent are more likely to cancel their participation. One way to achieve rapport is through to-face interviews. Therefore, face-to-face interviews in person would have been the most appropriate way in this study in order to establish trust and achieve rapport. The face-to-face interviews also enables the authors to observe the non-verbal communication in order to aim for a trustworthy process of gathering the data (Bryman, 2016). Due to the circumstances of Covid-19 during the research it was more difficult to achieve rapport since the interviews were done via Teams. Since, the interviews were conducted digitally with a video conversation it made the interviews similar to a face-to-face interview in real life.

3.3 Data collection

3.3.1 Criteria for sample

The first criterion was that the persons the authors interviewed were working at a company that acquired family firms or a company that have been acquired and was a family firm before the acquisition. However, due to the limited access affected by Covid-19, the criteria for the sample

acquisitions of family firms and who has insight and knowledge about the financial department. Another requirement was that the authors felt that the participants were able to answer the questions.

3.3.2 Selection of companies

In order to find suitable situations for the study, the authors started to investigate company groups known for investments which operates in Småland. The reason for investigating investment companies is because they acquire SMEs continuously, and therefore the likelihood of acquiring family firms is high. However, it is not a criterion that the companies are investment companies in this study and therefore the authors searched for other companies as well. The reason for looking at acquiring companies as a first step was because it is difficult to find records of which companies that has been family businesses before an acquisition and therefore, it eased the process to find acquiring companies as a first step.

The authors found suitable companies both by searching online and using their own circle of contacts. The authors were primarily interested in organizations in Småland because the initial thought was to do face to face interviews and therefore it would be easier for the researchers to travel to the interviews. Secondly, the region of Småland is famous for having an entrepreneurial culture with a lot of SMEs and family firms. However, the access problem led us to interviewing participants outside of Småland as well. Also, the location was not as important when the interviews were done digitally via Teams.

When the authors searched online for suitable companies, they used the key words: “investmentbolag”, “investmentbolag i Jönköping”, “investmentbolag småland”, “köper familjeföretag”. When potential companies were found, the authors analyzed their recent acquisitions in order to find out if any of them could be considered family firms prior to the acquisition. This was a challenging step because it was difficult to find information about the acquired company which fulfilled the definition for being a family firm before the acquisition. Therefore, the authors had to investigate existing press releases by the acquiring company to find out if they published who or whom they acquired the company from. If the authors got the indication that the company had acquired at least one family firm they contacted the company’s CEO or CFO by telephone to confirm if they had acquired family firms or not. If they had experienced acquisition of family firms, they were asked to participate in this study.

When some of the interviews were conducted, the authors noticed that it is very common to use a consultant or a business broker in acquisitions. In order to get a wider perspective of this special situation the authors searched for a business broker that would be interested to participate in an interview for this study.

3.3.2.1 Presentation of interviewees and cases

The following section will be organized by different groups (1, 2, 3 and 4). The companies that each group acquire will be presented and called by a letter (A, B, C, D, E and F). Further, the participants will be called by names made up, since individuals as well as organizations had been promised anonymity. To see the overview of the groups, see figures under each presentation below.

3.3.2.1.1 Company X and Henrik

As mentioned in 3.2, circumstances of Covid-19 and access led to the possibilities of searching for other perspectives of the subject. This resulted in an interview with the business broker Henrik who works at company X, which is a consultant company within the issues of ownership and acquisitions. Henrik has an education from high school and after that he has worked within the bank sector for a few years. He has also experiences from being a CEO and owning his own firm. Further, he has experiences from working with acquisitions within a large group. This experience led to that Henrik and his two colleagues started their own consulting company for years ago within acquisitions and ownership issues. From what the authors know, Henrik has no connection to the specific acquisitions discussed in this study.

3.3.2.1.2 Group 1

The acquiring group 1, is a Swedish publicly traded company with a net revenue of approximately SEK 2 billion and with approximately 1085 employees in the whole group (2019). Group 1’s operational activities is to acquire and develop companies with a special niche within the industrial and technique industry.

In group 1, the CFO “Monika” was interviewed. Monika has a Master of Science in business and economics. She has been working within group 1 for 28 years but in different positions. Today she is the CFO of the group and has been for 16 years and since 2014 she has been a part of the group management as well.

In 2019 group 1 acquired the Swedish family owned company A through one of their subsidiaries. Company A is a company with 25 employees and a net revenue of approximately 30 million at the time of the acquisition.

In company A, “Caroline” was interviewed. Caroline has a high school education within economics and have been working at a subsidiary within company A as a financial manager for 8 years. When the acquisition of company A took place, Caroline stepped in as the financial manager in company A as well.

In 2016 group 1 acquired the family owned company B. Company B operates in a foreign country. Before the acquisition, B had a net revenue of approximately SEK 338 million and around 110 employees. Due to several circumstances, interviews with company B was not possible and therefore the authors were not able to get the perspective from the acquired company. However, information about this acquisition was provided in the interview with Monika and through reviewing documents.

3.3.2.1.3 Group 2

The acquiring group 2, is a Swedish private investment company with a net revenue of approximately SEK 697 million and approximately 266 employees in the whole group (2019). The operational activities for group 2 are to invest and develop middle sized enterprises with their own products and brands.

In group 2, “Simon” was interviewed. Simon has a Master of Science in business and economics. He has worked as an auditor for 25 years with different positions within the profession and some of them with focus on acquisitions. Two years ago, group 2 was started by him and seven others and Simon is the CEO of the company.

In 2019, group 2 acquired the family owned company C. Before the acquisition company C had a net revenue of SEK 100 million and approximately 15 employees (2019).

In company C, the CFO and administrative manager “Peter” was interviewed. Peter has a Master of Science in business and economics and has an experience of 26 years of working at different financial departments. The companies that Peter have been employed at have all been family owned.

3.3.2.1.4 Group 3

Group 3 is a part of a holding company with a net revenue of approximately 3,5 billion and 1525 employees (2018). Group 3 started in 2017 and the main operations for group 3 is to invest and broaden the holding company’s offerings by entering new markets. Group 3’s mission is to invest long-term and give the opportunity to grow.

In group 3 “Steve” was interviewed. Steve has a Master of Science in business and economics and he also has a long experience of working as a controller and as CFO of a publicly traded group where they did many acquisitions. Recently, Steve started working for group 3. He does not have an official title at group 3 but, because of his previous experiences he is responsible for the financials of the investments and acquisitions they do and in this study his title will be CFO.

In the beginning of 2020, group 3 acquired company D with a net revenue of approximately SEK 95 million and 66 employees. It was not possible to get interviews in company D due to several reasons and therefore the authors could only get Steve’s thoughts about this acquisition. In addition to discussing the acquisition of company D, Steve discuss acquisitions in general from his previous experiences.

3.3.2.1.5 Group 4

Group 4 is a Swedish publicly traded group with a net revenue of approximately SEK 5 billion and approximately 6300 employees (2019). The operational activities are to manufacture and develop solutions for their customers.

In group 4 “Paul” was interviewed. Paul has a Master of Engineering and has worked for the group fort 12 years in various positions. Since 2013 he is the business developer for group 4, which often includes acquisitions. He is also a part of the group management.

In 2016, group 4 acquired the Swedish family owned company E. Company E had a net revenue of approximately SEK 430 million and approximately 450 employees (2016).

In 2015, group acquired the foreign family owned company F. In 2015 company F had a net sale of approximately EUR 25 million and 400 employees.

Due to several reasons it was not possible to interview company E or company F. However, information about both of the acquisitions of company E and F was provided in the interview with Paul and through reviewing documents.

3.3.3 Conducting the interviews

If the selected companies were interested in participating in the study, the authors provided them with further information about the purpose and explained how the interviews would be conducted. Due to the current circumstances of the pandemic of Covid-19, it was not feasible to perform face-to-face interviews in person. Therefore, the companies were given the opportunity to conduct the interviews digitally via Teams.

The interviews were scheduled during March and April 2020 and lasted for approximately 1 hour each. The interviews were based on the interview guide (see appendix 1-3) with questions that were based on the literature review. The interview guide was structured with open-ended questions at first in order to let the participants answer with their own words. After that, follow-up questions were asked if the authors wanted to get more information that could contribute to a deeper understanding. The follow-up questions could be both open and closed in order to understand the participants. The interview guide was structured based on three phases: introduction, the process and after the process.

In appendices 1-3, different interview guides were used; one for the acquirer, one for the selling party and one for the business broker. All interviews started with an introduction section where questions were asked because the authors wanted to get to know the interviewees. Also, this section was important because the authors wanted to get a sense of their background and try to achieve rapport. The introduction questions provided knowledge about their education and previous experiences to know if this could affect their answers they provided during the interview. Lastly, the interviewees were asked to describe what they thought characterized a family firm. This question was asked because the authors wanted to know their viewpoint of family firms and to see how experiences they were with family firms.

In the second section “the process before the acquisition” in appendices 1 and 2, many questions were similar but they were asked in different ways depending on whether the person worked for the acquiring group or the selling company. Firstly, the interviewees were asked why they acquired/sold the company and their experiences of acquisitions in order to get answers about if the CFO’s role could be different depending on situation specifics. Then open-ended questions about important aspects and key actors in an acquisition process were asked in order to get broad and honest answers, e.g. describing the process in their own words, what

is important in the process and potential difficulties in the process. Follow-up questions were then asked more specifically about the CFO’s role, how they can prepare, their tasks, influence in the process and in decision making. These questions were asked because the authors wanted answers about how the CFO’s role usually is in an acquisition process. Also, this section in the interview guide included a question about how meetings and procedures normally are planned. This was asked in order to get answers about the governance and management practices, since the previous literature stated that family firms might have more informal practices (Gallo et al., 2004; Mickelson and Worley, 2003; Duller et al., 2011; Hiebl, 2012).

However, in the section “the process before the acquisition” in the interview guide for the acquiring group (appendix 1), there were additional questions. Additional questions about acquisitions in general were asked to the acquiring group because they have more experiences of several acquisitions. The acquiring groups were asked if they had a special process when acquiring companies. This question was asked because the authors wanted to know if the process differs depending on different types of companies, including family firms or not. By asking follow-up questions, the authors hoped for getting deeper knowledge about how the approaches could differ when acquiring family businesses. Further, the interviewees were asked if they had experience of an outsourced financial department in the selling company and how that could differ. This was asked because the authors wanted to know if the experience and knowledge of the accountant/CFO affect the process. The authors assumed from the literature that since family firms tend to have informal management practices and lack of financial knowledge, the outsourced financial department would contribute with more knowledge. Lastly, the interviewee in the acquiring group were asked about the CFO in the selling company because the authors wanted to gain knowledge about this position from another perspective.

In the interview guide, there is a section called “SEW” where the main ambition was to get a deeper understanding of how important it was for the companies to preserve SEW. In the interviews with the selling company and the acquiring group, the authors asked if the family members got to keep their positions after the acquisition and how the companies valued their goals even after the acquisition. This was asked in order to get an understanding of how and if they valued non-financial goals and if they cared of preserving SEW in the long-term. The