The effect of Digital

Tools on Auditors’

Professional Scepticism

A Quantitative Study of Professional Scepticism in the

Swedish Audit Profession

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom

AUTHOR: Alexandra Kantonenko & Therése Karlström TUTOR: Timur Uman

i

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: The effect of Digital Tools on Auditors’ Professional Scepticism Authors: Alexandra Kantonenko and Therése Karlström

Tutor: Timur Uman Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Professional Scepticism, Structure and Judgment, CAATs, Audit Process

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to investigate and analyze whether the relationship

between structural domains represented by CAATs and judgment represented by professional scepticism is related to auditors’ individual characteristics, trait scepticism.

Methodology: This study is based on a quantitative method in the form of a questionnaire sent

to all Swedish authorized auditors. The response rate was 16.8 per cent. The responses were analyzed by Spearman correlation matrix, principal component analysis, multiple linear regression analysis, and hierarchical moderated multiple regression analysis. Moreover, this thesis is based on a positivistic perspective to get a general picture of professional scepticism. A deductive approach, going from theory to empirics, has been implemented.

Findings: The results showed a positive relationship between judgment represented by

professional scepticism and structure represented by CAATs, where auditors’ individual characteristics, trait scepticism, have a positive moderating effect on the relationship.

Theoretical perspectives: We apply the profession theory, comfort theory and structure and

ii

Acknowledgements

Approximately 16 weeks of writing this thesis have passed and it is after a lot of struggle, confusion, and effort that we have completed this thesis and are ready to present our results. With this project we hope to highlight the importance of professional scepticism and shed more light on the digital tools in the Swedish audit profession.

We would like to extend our gratitude towards our supervisor Timur Uman for his kind contribution to this project. During the supervisions, Timur has been important support, guiding us with motivation and commitment. His contributions have made a significant impact on this research and contributed to the coherence of the findings. For this, we are very thankful. We are also grateful for the engagement provided by the authorized auditors who took their valuable time to participate in this study. Without their input, it would not have been possible to complete the thesis. Finally, we would like to take the opportunity to thank teachers and staff at Jönköping International Business School. We have had four incredible years and are now moving on with new knowledge and experiences.

_______________________ _________________________

Alexandra Kantonenko Therése Karlström

Jönköping International Business School May, 2020

iii

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Definition ... 4 1.3 Purpose ... 8 1.4 Research Question ... 8 1.5 Outline ... 92.

Literature Review ... 10

2.1 The Audit Profession and The Profession Theory ... 10

2.2 Comfort Theory ... 12

2.3 Structure and Judgment ... 13

2.3.1 Structure ... 13

2.3.2 Judgment ... 15

2.3.3 Structure and Judgment ... 16

2.4 Audit Process ... 19

2.4.1 Planning ... 20

2.4.2 Execution ... 20

2.4.3 Reporting ... 21

2.5 Professional Scepticism as a Representation of Judgment ... 22

2.5.1 State Scepticism ... 23

2.5.2 Trait Scepticism ... 24

2.5.3 Professional Scepticism in The Auditing Process ... 25

2.6 CAATs as a Representation of Structure ... 26

2.6.1 CAATs in the Auditing Process ... 28

2.7 Professional Scepticism and CAATs ... 30

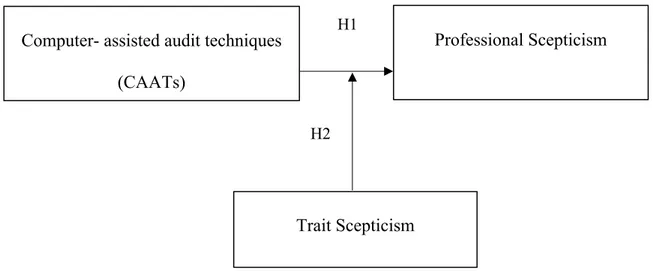

2.7.1 Hypothesis 1 ... 32

2.8 Individual Trait Scepticism ... 32

2.8.1 Hypothesis 2 ... 34 2.9 Research Model ... 35

3.

Method ... 36

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 36 3.2 Research Purpose ... 37 3.3 Research Approach ... 38 3.4 Research Method ... 39 3.5 Choice of Theory ... 403.6 Criticism of the Sources ... 42

3.6.1 Time Horizon ... 43

3.7 Data Collection Method ... 43

3.7.1 Questionnaire ... 44

3.8 Sample Selection ... 47

3.9 Pilot Study ... 48

iv 3.10.1 Dependent Variable ... 49 3.10.2 Independent Variable ... 50 3.10.3 Moderating Variable ... 50 3.10.4 Control Variables ... 51 3.11 Data Analysis ... 53

3.12 Reliability and Validity ... 54

3.13 Ethical Consideration ... 55

4.

Results and Analysis ... 57

4.1 Descriptive Statistics ... 57

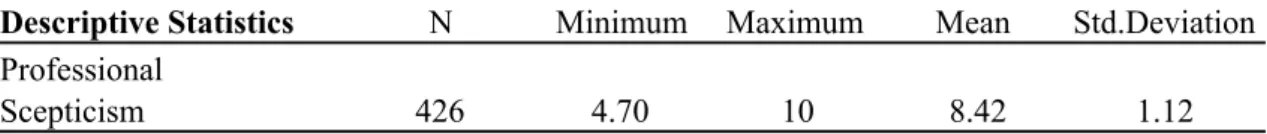

4.1.1 Dependent Variable ... 57

4.1.2 Independent Variable ... 57

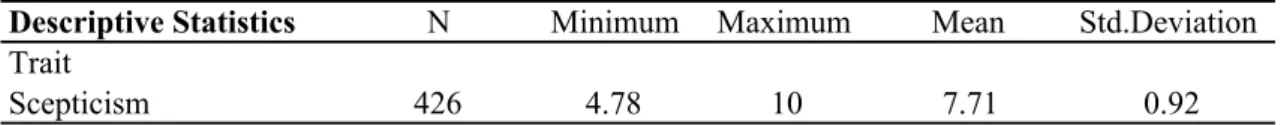

4.1.3 Moderating Variable ... 58

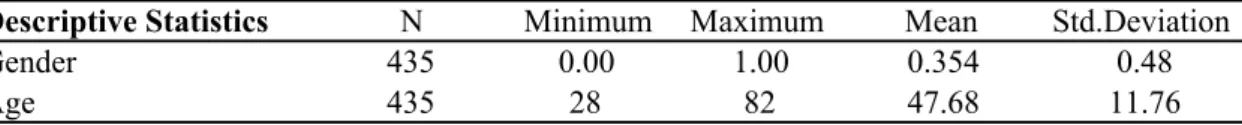

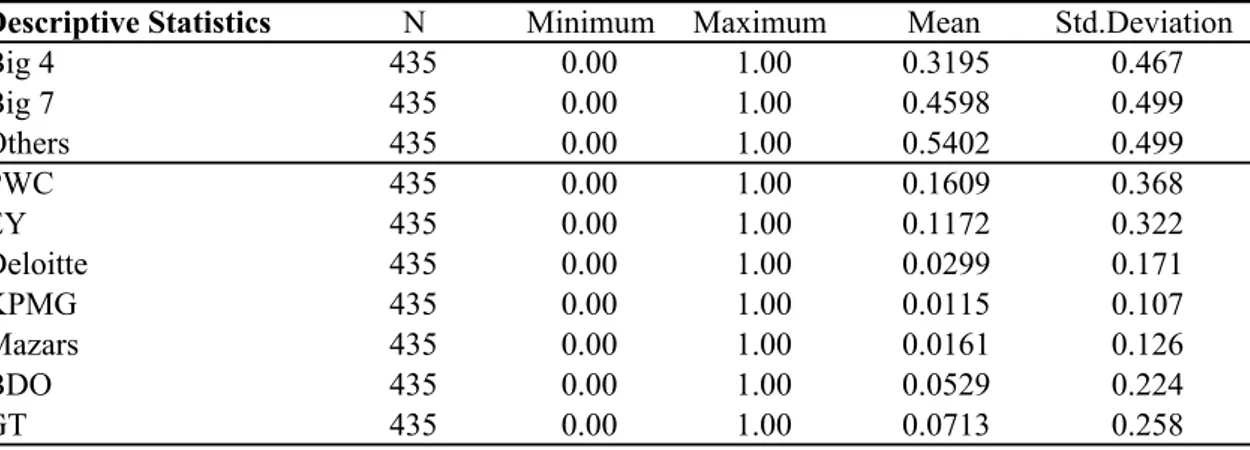

4.1.4 Control Variables ... 59

4.2 Principal Component Analysis ... 60

4.2.1 Dependent Variable ... 61

4.2.2 Independent Variable ... 61

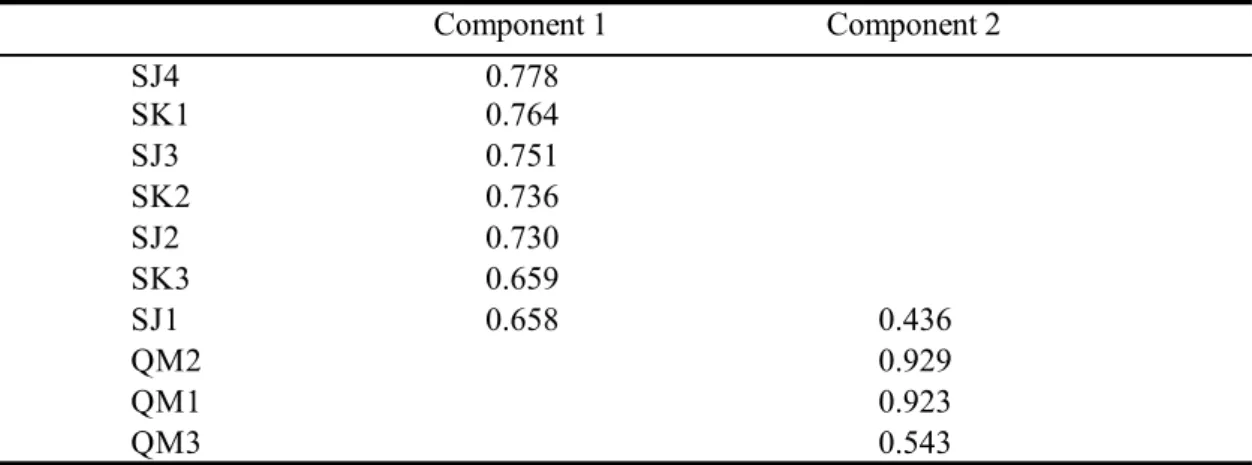

4.2.3 Moderating Variable ... 62

4.2.4 Dependent-, Independent-, and Moderating Variable ... 62

4.3 Normal Distribution ... 64

4.4 Spearman Correlation Matrix ... 64

4.5 Multiple Linear Regression Analysis ... 68

4.6 Hierarchical Moderated Multiple Regression Analysis ... 70

4.7 Hypotheses ... 73

5.

Discussion ... 74

5.1 Hypothesis 1 ... 74

5.2 Hypothesis 2 ... 76

5.3 Other Empirical Findings ... 78

6.

Conclusion ... 80

6.1 Overarching Conclusion ... 80

6.2 Theoretical Contributions ... 82

6.3 Empirical Contributions ... 84

6.4 Practical Implications ... 85

6.5 Limitations and Future Research ... 87

6.6 Reflection ... 90

v

Tables

Table 1- Frequency per Company ... 48

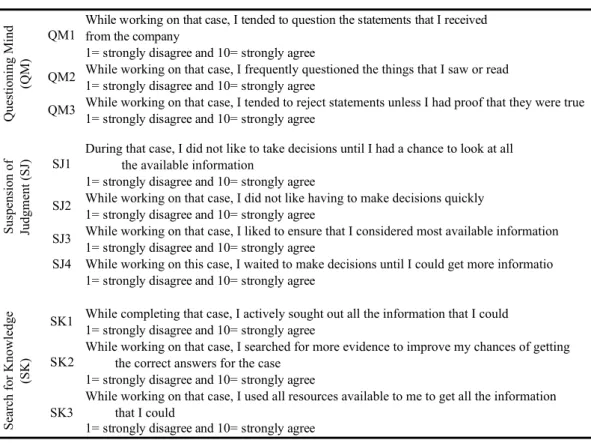

Table 2- Statements Professional Scepticism ... 49

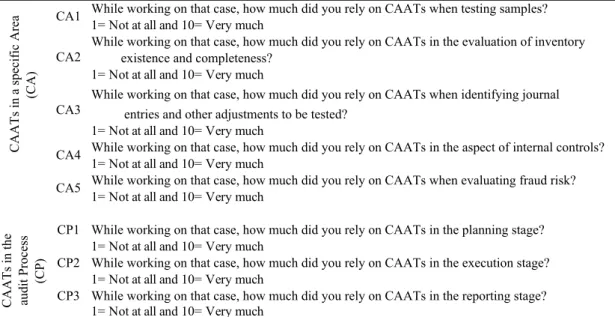

Table 3- Questions CAATs ... 50

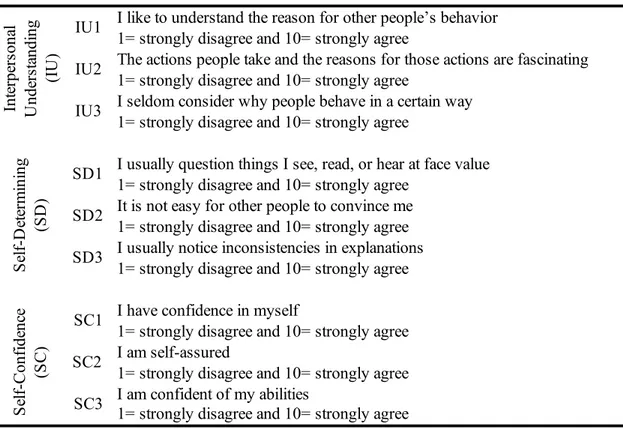

Table 4- Statements Trait Scepticism ... 51

Table 5- Descriptive Statistics Professional Scepticism ... 57

Table 6- Descriptive Statistics CAATs ... 58

Table 7- Descriptive Statistics Trait Scepticism ... 58

Table 8- Descriptive Statistics Gender, Age ... 59

Table 9- Descriptive Statistics Organizational Tenure, Professional Tenure, Partner ... 59

Table 10- Descriptive Statistics Company ... 60

Table 11- Rotated Component Matrix Professional Scepticism ... 61

Table 12- Rotated Component Matrix Trait Scepticism ... 62

Table 13- Rotated Component Matrix Professional Scepticism, CAATs, Trait Scepticism ... 63

Table 14- Spearman Correlation Matrix ... 67

Table 15- Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2 ... 69

Table 16- Tests of hypothesis 1 ... 70

Table 17- Tests of hypothesis 2 ... 71

Table 18- Hypotheses Overview ... 73

Figures

Figure 1- Research Model ... 35Figure 2- Distribution of Professional Scepticism ... 64

Figure 3- Standardized Two-Way Interaction Effect Trait Scepticism ... 73

Appendix

Appendix I- Questionnaire in Swedish ... 1061

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The introductory chapter will present a background to the research as well as a problem discussion. Subsequently, the purpose and the research question of the study will be presented.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The audit profession is one of the most fundamental professions and plays a vital role in society and in global capital markets (IFAC Handbook, 2018a). An auditor’s overall objectives are the conduct of an audit according to the International Standards on Auditing (ISA), where the main target is to guarantee that the financial statements are free from material misstatements (ISA 200; ISA 240; ISA 330). The audit quality indicates the degree to which the audit ensures that the financial statements are free from material misstatements, after the finalization of an audit (Wedemeyer, 2010). Auditors are expected to provide an independent audit review of a company’s operations, which in turn will provide quality assured information for the external stakeholders (Bierstaker, Burnaby & Thibodeau, 2001). Aside from providing essential information to both investors and shareholders, auditors ensure the reliability and reasonability of the financial statements (Umans, Broberg, Schmidt, Nilsson & Olsson, 2016). Nevertheless, with the development that digitalization has brought, the risk of fraudulent behaviour has progressed. Risk of fraudulent behaviour has been the reason for auditors' inability to discover material misstatements in the financial statements and thus, the inability to serve the public interest which has during the previous years led to a decline in the public's trustworthiness towards the audit profession (Carcello, Hermanson & Raghunandan, 2005). Inability to detect fraudulent behaviour has further led to some of the largest corporate scandals in the 2000s, for example, Enron (2001), WorldCom (2002), and Lehman Brothers (2008) (Sonu, Ahn & Choi, 2017). The consequences following the scandals developed several bankruptcies and losses in large financial values, which further generated criticism towards the audit profession (Broberg, 2013; Carcello et al.,

2

2005). According to Forsberg and Westerdahl (2007), these scandals were evidence of the fact that auditors gradually moved from protecting the public interest towards prioritizing the interest of their clients, a situation that threatened the trust in auditors’ judgment.

Auditors across the world are obliged to comply according to the international standards published by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), a worldwide organization. IFAC publishes various International Standards on Auditing (ISA). One important part of these standards is the auditor’s professional judgment. ISA 200 paragraph 16 states that “The auditor shall exercise professional judgment in planning and performing an audit of financial statements”. Professional judgment is one of the most essential aspects of auditing. It is one of the cornerstones within the audit profession, what the clients purchase, and what the public expects from an auditor (Cowperthwaite, 2012). Moreover, it is necessary for auditors to make professional judgments to provide an accurate audit opinion and process. The audit process requires interpretations and decisions, something that cannot be performed without relevant information about the client, experience, or knowledge. Auditors with training, knowledge, and experience are expected to pursue reasonable judgments and hence, have a professional judgment (IFAC Handbook, 2018b).

Professional judgment is related to the concept of professional scepticism (Nelson, 2009). Professional scepticism is defined as an attitude that requires an auditor to maintain a questioning mind and a critical assessment of the audit evidence (Brazel, Jackson, Schaefer & Stewart, 2016; Nelson, 2009). Both concepts, professional judgment and professional scepticism, are important for the correct conduct of an audit and high audit quality (IAASB, 2012). Both researchers (e.g., Nelson 2009) and regulators (ISA 200) promote the importance of professional scepticism in the audit process (Grenier, 2017; Hurtt, Brown-Liburd, Earley & Krishnamoorthy, 2013).

Besides the importance of making professional judgments in the audit profession, Broberg (2013) highlights the essential part of the structure in the audit process. Structure assists in the conduct of audit opinions, which can be shown as time spent on documentation (Broberg, 2013). According to Revisorslagen (2001:883) 24 §, auditors

3

are required to document their audit process with information that is important to estimate the auditors’ impartiality and independence. Broberg (2013) further states that structure within auditing increases the audit quality. Moreover, the structure within auditing is important in order for the auditor to be more effective and efficient in their work and is implemented in the auditing process to control the level of biases (McDaniel, 1990; Schroeder, Reinstein & Schwartz, 1996). Structure within the audit process can be described as IT-systems and technology used within the audit profession (Manson, McCartney & Sherer, 2001). Computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs) can be described as the use of technology that supports auditors in the completion of an audit (Pedrosa, Costa & Aparicio, 2019).

The relationship between structure and judgment is known and discussed in the accounting literature. Prior studies argue that structure can have both a negative and a positive impact on professional judgment (e.g. Bierstaker et al., 2001; Kosmala MacLullich, 2001). Nevertheless, the majority of prior literature argues that structure has a negative impact on professional judgment (e.g. Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986; Kosmala MacLullich, 2001; Myers, 1997; Power, 2003). This negative relationship is claimed to limit auditors’ ability to apply professional judgment (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001). The profession theory describes auditing as a profession where professional judgment plays a crucial role in auditors’ work (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013; Eklöv, 2001). This theory further highlights the auditors’ expertise (Brante, 1988). This expertise could be in the form of structure that contains IT-tools and various computer software which contributes to auditors’ professional knowledge (Öhman, Häckner, Jansson & Tschudi, 2006) that can not be acquired independently (Brante, 1988). Brante (1988) argues that expertise within auditing, in the form of professional judgment (Eklöv, 2001) and structure, must continuously be improved in order for auditing to be viewed as a profession.

Producing comfort is important for auditors since it is the activity where numbers are converted from an untrustworthy state into a comfortable form (Carrington & Catasús, 2007). In order for auditors to become comfortable in their work and perform high-quality audits, structure and judgment are two important factors that must be met (Carrington &

4

Catasús, 2007; Pentland, 1993; Power, 2003). Comfort theory provides an understanding of how comfort relates to professional judgment and how auditors comfort level is affected by structure. A successful audit indicates that comfort has been reached on several levels during the audit process (Carrington & Catasús, 2007).

Adrian (2014) highlights that every audit process requires an individual process where the auditor must assess the data and make professional judgments for each specific case. This is referred to as the professional judgment, where judgments are based on situational factors (Robinson, Curtis & Robertson, 2018), however, previous literature also argues for the impact of individual characteristics on the professional judgment (Broberg 2013; Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Power, 2003). These individual characteristics, referred to as trait scepticism (Quadackers, Groot & Wright, 2014), are compared to situational factors, more stable and consistent (Hurtt, 2010; Nelson, 2009). Moreover, individuals with higher levels of trait scepticism are claimed to require more information and evidence in the audit process, in contrast to those with lower levels of traits (Quadackers et al., 2014). With this said, since every audit process, in the end, will be affected, not only by the professional judgment but also by individual traits, it is of interest to investigate whether the effect of structural domains on the judgment is dependent on auditors’ individual characteristics, trait scepticism. Therefore, the focus of this paper will not only be placed on the negative relationship between structure and judgment, represented by CAATs and professional scepticism, but also on whether trait scepticism moderates this relationship.

1.2 Problem Definition

As we live in a more digitized world, technology plays an important role, impacting many industries (Kuusisto, 2017). One of the concerned industries is the audit profession, where digitalization has contributed to a more efficient and effective audit process (Han, Rezaee, Xue & Zhang, 2016). Technological advancements in auditing are referred to as structure in the accounting literature (Janvrin, Bierstaker & Lowe, 2009). Structure can improve efficiency and effectiveness within the audit process, however, it can have both a positive and negative impact on professional judgment (e.g. Bierstaker et al., 2001; Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986).

5

Professional judgment is one of the most important aspects of auditing (Broberg, 2013). Within accounting, professional judgment is exercised in the prediction of conditions and events, and in situations that have conditions of uncertainty (Eklöv, 2001). Several audit standards (e.g. ISA 200; ISA 315) highlight the importance of professional judgment, a fact that indicates the importance of auditors’ professional judgment in the audit profession (Broberg, 2013). As ISA 200 states, professional judgment must be applied throughout the audit and documented after the completion of the audit. Moreover, professional judgment is essential in the matter of risk assessment (ISA 200). However, structure provided within auditing firms is argued to impact the professional judgment of auditors (Broberg, 2013). Structure within auditing is usually viewed as technological advancements such as audit techniques. Checklists, templates, questionnaires and the audit firm’s work policy are some examples. Since auditors have strong trust in the auditing firms’ systems and guidelines, the structure has a crucial role during the auditing process (Broberg, 2013; Pentland, 1993). The situation where the auditor prioritizes structure within checklists or specific software might lead to the fact that the auditor sets aside commitments that are relevant for their clients (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001). Structure and judgment are a well-discussed topic within the audit research (Broberg, 2013; Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986; Kinney, 1986; Morris & Nichols, 1988; Power, 2003; Schroeder et al., 1996). The development of IT-systems has increased the amount of structure within the audit process (Agevall, Broberg & Umans, 2018). This increase makes auditors mechanical in their way of thinking (Broberg, 2013), leading to a negative impact on professional judgment. Kosmala MacLullich (2001) states that structure endangers auditors’ ability to execute professional judgment since structure within the auditing process decides which professional judgments should be made and when. On the other side of the literature, some authors argue that structure has a positive effect on professional judgment. Power (2003) states that structure legitimates the auditors’ work. Moreover, since structure increases the effectiveness and efficiency of the auditing process (Myers, 1997), auditors have more time to focus on their judgments (Bierstaker et al., 2001). Further, Cushing and Loebbecke (1986) state that there exists a continuum between the two concepts.

6

A theory that highlights the importance of judgment and structure within the audit profession is the profession theory. Judgment is important since it contributes to the fact that auditing is viewed as a profession (Brante, 1988; Eklöv, 2001). Meanwhile, structure, usually referred to as the digital tools in auditing, contributes to auditors’ expertise and professional knowledge (Öhman et al., 2006). Brante (1988) argues that judgment and structure are two components that make auditors professionals.

For auditors to reach the desired level of comfort, comfort must be achieved in both structure and judgment (Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Power, 2003). Auditors must perform the “right things” and do “things right” in order to become comfortable (Broberg, 2013). When auditors aim to do the “right things”, they rely more on the structure. However, when auditors aim to do “things right”, judgment is the dominant aspect (Broberg, 2013). However, sufficient levels of comfort must be attained in both structure and judgment for the auditor to provide a high-quality audit (Broberg, 2013; Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Pentland, 1993).

Judgment can be represented in the form of professional scepticism (Nelson, 2009). Nelson (2009) describes professional scepticism as the product of an auditor's judgment. According to ISA 200 professional scepticism is explained as “an attitude that includes a questioning mind, being alert to conditions which may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud and a critical assessment of audit evidence”. It is essential to exercise professional scepticism throughout the audit in order to conduct an audit opinion (Hurtt et al., 2013; Nelson, 2009). In addition to professional scepticism, auditing standards encourage usage of CAATs (ISA 315; ISA 330). CAATs are one representation of structure (Braun & Davis, 2003) and assist auditors in the conduction of an audit through the extraction and analysis of data from computer applications and software (Pedrosa et al., 2019). The implementation of CAATs increases auditor’s productivity and has automated several audit tasks (Curtis & Payne, 2008; Mahzan & Lymer, 2014). CAATs has made the audit process more automated in its nature where more work is performed automatically and less manually (Curtis & Payne, 2008; Siew, Rosli & Yeow, 2020). The automatic process makes auditors less reflective in the audit process (Gilbert, Krull & Malone, 1990), and more mechanical in their way of thinking (Broberg, 2013). At the same time, auditing standards require auditors to apply professional scepticism

7

throughout the audit process (ISA 200; ISA 240; ISA 330). Professional scepticism is especially important in the area of risk assessment and is necessary to improve the audit quality (ISA 200; Peytcheva, 2014).

In addition to professional scepticism that represents the professional judgment of an auditor (Nelson, 2009), professional judgment is also argued to be moderated by individual characteristics (Broberg, 2013; Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Power, 2003), known as trait scepticism (Quadackers et al., 2014) or individual traits (Hurtt, 2010). As an individual characteristic, professional scepticism can be viewed as trait scepticism used by the individual auditor (Hurtt, 2010). Trait scepticism is the personal difference in feelings, thoughts, and behaviours that represent the core personality of an auditor (Buss, 1989; Church, 2000; Robinson et al., 2018). Nelson (2009) describes individual traits as non-knowledge characteristics that can affect the professional scepticism of an auditor. The personal traits are stable over time and may be difficult to change (Church, 2000; Robinson et al., 2018). According to Libby and Luft (1993), performed judgments are dependent on knowledge and traits. Auditors’ personal traits are therefore reflected in their decisions (Trevino, 1986). Moreover, higher levels of trait scepticism are argued to be connected to individuals that strive for more information and evidence in the audit process, in contrast to those with lower levels of trait scepticism (Quadackers et al., 2014).

Professional scepticism consists of two parts, state scepticism and trait scepticism (Hurtt, 2010). However, other researchers suggest a separation of these two concepts. Robinson et al. (2018) argue these two concepts could be viewed as two separate constructions due to the specific nature of state scepticism and the general nature of trait scepticism. Professional scepticism, as state scepticism, will indicate different levels of professional scepticism in different situations (Robinson et al., 2018), and is argued to be more important in the context of professional scepticism (Shaub, 1996). Moreover, state- and trait scepticism could be viewed separately since state scepticism indicates a greater response in establishing subjective trust of the client. According to Shaub and Lawrence (1996), state scepticism contributes more to the applied professional scepticism compared to trait scepticism. With this said, it is of interest to investigate professional scepticism and trait scepticism as two separate concepts. Investigation of auditors' professional

8

judgment is relevant in the time since the amount of structure is increasing (Agevall et al., 2018) as a result of the development in technology (Sutton, 2010) and automatization in the audit profession(Chan & Vasarhelyi, 2011).

The relationship between structure and judgment has been investigated empirically by several authors (e.g. Broberg, 2013; Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986; Kinney, 1986; Morris & Nichols, 1988; Power, 2003; Schroeder et al., 1996). However, previous research mainly focused on judgment and structure as two broad aspects, without defining a certain definition. Moreover, it has not been investigated whether this relationship could be contingent on the individual trait scepticism of an auditor, a different concept, albeit related to the professional scepticism of an auditor. This study will focus on judgment, represented by professional scepticism, in relation to structure, represented by CAATs, moderated by trait scepticism in the context of Swedish authorized auditors.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether the relationship between structural domains represented by CAATs and judgment represented by professional scepticism is related to auditors’ individual characteristics, trait scepticism.

1.4 Research Question

How does auditor’s trait scepticism relate to the relationship between structural domains represented by CAATs and professional judgment represented by professional scepticism?

9

The literature review presents the main underlying theories implemented in this thesis, which are the profession theory and the comfort theory. Thereafter, every theory is connected to the main concepts in this thesis; judgment, structure, professional scepticism, CAATs and trait scepticism, in the context of the Swedish audit firms.

This chapter covers the process undertaken to examine the research question and hypotheses. It displays the research, choice of method and theory, criticism of sources, time horizon, research strategy, data collection and sample selection. Subsequently, the operationalization of the variables is presented, which is followed by data analysis, the validity and reliability of the data and lastly ethical considerations.

The results and analysis chapter display the results from the quantitative data which has been gathered through statistical data analysis of the online questionnaire. Continuously, the results are analysed and discussed in relation to whether the stated hypotheses are supported or not.

The discussion chapter presents the gathered results in relation to existing literature.

The last chapter presents an overall conclusion, followed by the contributions and limitations of this study. Additionally, suggestions for future research are presented, the chapter is ended with some reflections concerning this thesis. 1.5 Outline

The introduction began with presenting the background of the importance of professional judgment and professional scepticism in auditing. Subsequently, a problematization followed, where the complex relationship between structure and judgment within the audit profession was presented. This ended up in a research purpose and a research question.

Introduction Literature review Method Results and Analysis Discussion Conclusion

10

2. Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides a deeper understanding of the subject by presenting relevant theories of the study. Furthermore, previous research on structure and judgment, with representations of CAATs and professional scepticism will be presented. Additionally, explanations of trait scepticism and the audit process will be provided.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 The Audit Profession and The Profession Theory

Professions and professional work are a commonly discussed field. Today's society demands the expertise that professionals possess, where a profession is viewed as the stream of information with expertise (Abbott, 1988; Brante, 2005). Professional work includes complexity, uncertainty and the obligation of exercising judgment (Brante, 1988; Freidson, 2001). Professions require trust from the society in the work and the judging they accomplish (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). Accordingly, professional judgment is one of the most important parts of the audit profession (Eklöv, 2001). Auditing is classified as a profession since it requires unique knowledge and contains a legitimized role that differentiates it from other professions (Brante, 2005; Grey, 1998). Auditors are viewed as professionals since they have a crucial role in society and perform their work based on scientific knowledge (Brante, 1988). Further, auditors are viewed as neutral representatives with a high level of expertise and corresponding education (Artsberg, 2003).

The audit profession took form from characteristics in professions such as lawyers and surgeons that contributed to professionalism (Abbott, 1988). Traditionally, the auditor's role was to ensure the quality of the audited financial statements (Öhman, 2005). Today, this role also entails a commitment towards the client and a desire to provide additional value through the service (Herda & Lavelle, 2013). Expectations that are placed on the audit profession result in high requirements on auditors independence and integrity (Elg & Jonnergård, 2011). Independence and integrity are especially of importance in

11

situations that require the auditor to make judgments (Öhman, 2005). Auditors along with lawyers, engineers and doctors, are typically regarded as professions that are dependent on the trustworthiness of the society.

Auditing is a regulated profession (Öhman et al., 2006), nevertheless, auditing is based on professional judgments (Eklöv, 2001). This can be seen in e.g. ISA 200 and ISA 315 that require auditors to exercise professional judgment. Auditors with training, knowledge and experience are expected to exercise professional judgment (IFAC Handbook 2010). Beside exercising professional judgment, it is important that auditors follow laws and regulations within the profession to maintain their professionalism (Brante, 2009). Auditors themselves believe that the reason why auditing is viewed as a profession is because of the unwritten action norms placed on the profession (Artsberg, 2003). The impact of profession theory on the audit profession can also be seen in the placed requirements on the auditors’ expertise. Expertise within the audit profession must continuously be improved to regard auditing as a profession in accordance with the profession theory (Brante, 1988). Abbott (1988) argues that in order to be a professional, one must have the expertise that cannot be acquired independently. Increase in structure, as a result of the development of IT-tools, requires auditors to implement and learn various computer software, checklists and new routines to make judgments (Öhman et al., 2006).

Profession theory contributes to the understanding of attributes, characteristics and structure of professionals (Brante, 1988). Profession theory is relevant in this study since auditing is classified as a profession where auditors’ work is based on professional judgments. Further, it is relevant to implement this theory since structure and judgment contribute to the professional development and expertise of an auditor, which makes auditors professionals. Finally, the presentation of profession theory will provide an explanation and a structure of the audit profession.

12

2.2 Comfort Theory

Comfort can be produced both externally and internally, where the internal comfort refers to what the auditor experiences during the audit (Carrington, 2014). Producing comfort is one of the main objectives of an auditor. Production of comfort is an activity that converts numbers from an untrustworthy state into a comfortable form for both auditors and the public (Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Pentland, 1993). Kosmala MacLullich (2003) states that auditing is about making the auditor comfortable with the numbers. In order to be comfortable, the auditor must be confidenton how the audit is performed and by whom (Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Power, 2003). Comfort is not only the desired outcome of an audit, but it is also the state that is being produced during the entire audit process (Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Pentland, 1993). The reached level of comfort is dependent on the different participants and the composition of the audit process. A successful audit effort means that the auditor has attained comfort on several levels. When these comfort levels are reached, the auditor is able to provide an audit opinion (Carrington & Catasús, 2007).

Structure and judgment are important in order for auditors to become comfortable in their work performance and to perform high-quality audits (Broberg, 2013; Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Pentland, 1993; Power, 2003). Broberg (2013) explains that to become comfortable, the auditor must perform its work correctly and focus on the right tasks. When auditors aim to do their work correctly, they appear to rely more on the structure. However, when auditors focus on the right tasks, judgment appears to be the dominant aspect (Broberg, 2013).

To reach comfort, the auditor must work “with and through structure” (Carrington & Catasús, 2007, p.45). The use of structure in the audit process is a greatly appreciated tool to avoid discomforts and instead produce comfort (Carrington & Catasús, 2007). The structure facilitates the audit process and provides comfort for the auditor in simpler tasks (Myers, 1997).Öhman et al. (2006) describe that auditors rarely question structure since it might hinder their ability to reach the desired comfort level. In addition to working “with and through structure” the auditor must also exhibit its personality, integrity and experience to reach comfort (Broberg, 2013). An auditor’s personality and judgments determine which tasks that will be performed to achieve comfort. Moreover, the auditor’s

13

preference for a certain work also implies more comfort for the auditor (Carrington & Catasús, 2007). Further, more complex tasks require higher levels of professional judgment to reach comfort (Eilifsen, Messier, Glover & Prawitt, 2014). This is especially important since the professional judgment of an auditor affects the audit quality (Broberg, 2013).

Important to highlight is that the auditor must attain a sufficient level of comfort in both structure and judgment to provide a high- quality audit (Broberg, 2013; Carrington & Catasús, 2007; Pentland, 1993). Comfort theory is important in this study since it provides an understanding of how a level of comfort relates to the professional judgment of an auditor and how the auditor’s comfort level is affected by structure. Further, this theory will provide an understanding on whether implementation of CAATs makes auditors more comfortable in their work and thus, whether less professional scepticism is applied. The comfort theory will provide a deeper comprehension in how comfort affects the audit profession and affects the relationship between judgment and structure.

2.3 Structure and Judgment 2.3.1 Structure

Cushing and Loebbecke (1986) define structure as: “a systematic approach to auditing characterized by a prescribed, logical sequence of procedures, decisions and documentation steps, and by a comprehensive and integrated set of audit policies”. Structured activities within the audit profession refer to activities that are rule-based and require some kind of routine (Power, 2003). In structured activities, the auditor focuses on performing “things right” and not performing the “right things” (Öhman et al., 2006). According to Power (2003), the “scientistic” assumption of the structure is described as algorithmic decision aids that are encoded from a logical series of steps. In this way, the structure represents a universal audit through a system of rules (Power, 2003). Lastly, structure is defined as control and legitimacy (Power, 2003).

Structure is often viewed as formal decision aids, checklists and mandated procedures, and is often computer-based (Knechel, 2007). The checklists are often pre-printed where computer packages, such as audit program preparations, are designed to assist in auditors'

14

judgments (Prawitt, 1995). According to Cushing and Loebbecke (1986), the structure includes organizational arrangements and technology, which involves both audit tools and decision aids. Technology within the audit profession consists of audit software and systems which are implemented to help the auditor in the conduct of an audit (Broberg, 2013; Pedrosa et al., 2019).

Bhattacharjee and Moreno (2002) explain that structure is especially important for less experienced auditors that are more impressionable in their judgments. It is common that new auditors in the field are introduced to the profession through a highly structured working process. This assists the new auditors in developing a critical mind and helps them in their daily tasks. The structure also assists the more experienced auditors that control that the work is performed correctly. Structure enhances audit quality and efficiency (Dillard & Bricker, 1992)since it will give the auditor more time to focus on more complex tasks (Bierstaker et al., 2001). Audit firms that implement structure design their IT-systems to enforce their methodology and promote consistency across engagements. Moreover, these enforcements are achieved through automated decision support, automated integration and automated tailoring (Teeter, Alles & Vasarhelyi, 2010).

The audit process is a structured way of formalized steps that leads to an audit opinion (Carrington, 2014; Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986). Activities in the audit process that require routine are for example checklists (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001), which provides the auditor with detailed comprehensive guidance (Smith, Fiedler, Brown & Kestell, 2001). Other activities are documentation and administration (Broberg 2013). The audit process is becoming more standardised, which according to Knechel (2013) means an increase in structure. Development of technology and increase in IT-tools within the audit profession are seen as the largest reasons for this increase. (Abdolmohammadi, 1999; Sutton, 2010; Öhman et al., 2006). Some software performs the work completely automatically and does not require an auditor to generalize data. However, software that performs more complex activities might require the auditor to be engaged in the activity (Abdolmohammadi, 1999). More structured software increases audit effectiveness and efficiency by automatically implementing data in the engagement file. This is made through, for example, when risks are identified in the planning stage, they are

15

automatically implemented in the execution stage of the audit process. This guarantees the risk assessment (Carson & Dowling, 2012).

Previously, the larger audit firms could be divided according to their working processes into structured, unstructured or semi-structured firms (Kinney, 1986). However, more recent studies argue that these differences have been reduced and that the larger audit firms could be viewed as semi-structured (Broberg, 2013; Smith et al., 2001).

2.3.2 Judgment

Professional judgment is the foundation of the audit profession (Öhman et al., 2006) and one of the most important aspects of auditing (Broberg, 2013). According to Downie and Macnaughton (2009, p.323), judgment is “an assertion made with evidence or good reason in a context of uncertainty”. Professional judgment can further be seen as the auditor’s knowledge, experience and ability to separate important information and upon that information make decisions (Agevall et al., 2018). According to IFAC (2010), auditors with high training, experience, and knowledge are expected to provide appropriate judgments. Further, professional judgments are needed in order to adjust the audit plan accordingly to the client’s conditions and requirements (Dirsmith & McAllister, 1982). As stated in ISA 200, “Professional judgment is essential to the proper conduct of an audit. This is because interpretation of relevant ethical requirements and the ISAs and the informed decisions required throughout the audit cannot be made without the application of relevant knowledge and experience to the facts and circumstances.” Auditors make many decisions based on their judgment, some of which are: a) assessment of risk of material misstatements in the financial statements, b) construction of an opinion on the financial statements, c) evaluation of management’s judgments in implementing the company’s applicable financial reporting framework, and d) evaluation of audit evidence to device the audit quality (ISA 200: A23; Wedemeyer, 2010).

Professional judgment is a reflection made by auditors who use various audit techniques (Broberg, 2013). However, it is not only the audit techniques that develop the auditor’s judgment, the social context also has an impact. Auditors can reach their judgment

16

through communication, for example, with their colleagues (Solomon, 1987). Professional judgment is created through several assessments that arose during the audit process. An assessment can be explained as a statement based on factual considerations (Öhman et al., 2006). Moreover, Popova (2012) states that professional judgment can be viewed as a subjective perception created through different types of assessments. These judgments are based on the auditor’s knowledge and its intuition made through its scepticism (Popova, 2012). Kosmala MacLullich, (2001) highlights the importance of applying professional judgment throughout the whole audit. It is necessary that auditors execute professional judgment in order to provide a correct audit opinion. Carrington (2014) strengthens this argument by arguing that professional judgment must be, to some extent, included in all levels of the audit process. The judgment is based on activities such as materiality, internal control but also the choice between continuous inspection and acceptance. When enough audit evidence is collected, the auditor concludes their judgments in an audit opinion.

2.3.3 Structure and Judgment

The relationship between judgment and structure is complex and determining the roles of these aspects can be challenging (Agevall et al., 2018; Power, 2003). The structure-judgment debate has been an ongoing topic in the accounting literature for a longer period of time. Nevertheless, Agevall et al. (2018) argue that this debate is more relevant than ever because of the increased structure in the audit profession. Regulations require auditors to document their work which has resulted in many audit firms implementing digital tools and manuals to simplify and improve the audit process. It could also be argued that structure has been used and developed in the audit firms to reach control (Power, 2003) and comfort (Broberg, 2013). These developments have raised one interesting question, whether structure limits auditors’ judgments (e.g. Agevall & Jonnergård, 2007; Kosmala MacLullich, 2001; Power, 2003; Schroeder et al., 1996). Auditing is explained as judgmental in its nature where “judgments are made in tacit and intuitive processes” (Eklöv, 2001, p.62). These processes are resistant to systematization (Eklöv, 2001). At the same time, the existing guidelines executed by ISA are targeted towards more structure and less judgment (Öhman et al., 2006). Power (2003) explains

17

that it might be difficult for an auditor to implement a high level of structure in the audit process and at the same time create space for their professional judgments. Further, Kosmala MacLullich (2001) argues that structure in the audit process endangers an auditor’s ability to execute professional judgments. This is since structure guides the auditor in when to make judgments and what judgments to make (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001).

Structured firms are relying on predetermined audit programs, statistical sampling, analytical models and structured internal controls (Kinney, 1986; Schroeder et al., 1996; Kosmala MacLullich, 2001). This leads to a more predetermined audit plan and process. When the audit process is highly dependent on structure, auditors can get mechanical in their way of thinking and acting, which can reduce auditors’ professional judgment (Broberg, 2013). This can also lead to auditors ignoring important information that is not included in the audit plan (Myers, 1997). Thus, structured firms that rely more on evidence provided in the audit plan rather than on their professional judgment can end up with more misstatements (Schroeder et al., 1996). Audit firms that rely on structural elements tend to concentrate their audit on areas that are familiar and concrete. This might lead to auditors focusing more on quantitative information rather than on qualitative information (Broberg, 2013). Auditors are expected to execute more qualitative assessments (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001), however, at the same time there is an increase in guidelines and regulations that auditors have to follow (Agevall et al., 2018). Ignoring qualitative assessment and evidence might jeopardize the professional judgment of an auditor which means that an efficient audit cannot be performed (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001).

However, structure does not necessarily have to end or reduce the judgment. Kosmala MacLullich (2001) explains that it might rather reallocate the judgment and assist it in the right direction within the audit process. Structure provides guidelines and works as a benchmark for actions, nevertheless, it leaves the final decisions for the individual judgment of an auditor. Further, Kosmala MacLullich (2001) argues that it is the judgment of the auditors that will make a decision whether the structure reflects correct information in the financial statements. Stringer (1981) explains that technology contributes to well-structured processes that increase the audit quality and decrease

18

occurrences of misstatements, assisting auditors' judgment in the right direction. Bierstaker et al. (2001) confirm this statement by claiming that the increase in structure as a result from online audit systems is going to free auditors from several activities and allow them to concentrate more on judgments that each individual client requires. Finally, an increase in structure decreases the number of unnecessary procedures (Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986).

Despite the debate on whether structure increases or decreases judgment, there is also another view on the relationship between these concepts. Broberg (2013) argues that auditors make structured judgments, which means that they must be structured in their way of performing judgments. Meaning that these two concepts should not always be seen as two separate methods, rather they should be seen as complementaries to each other. Further Broberg (2013) claims that in order for an auditor to establish themselves in the audit profession they must be able to balance between structure and judgment. A balance between these two concepts is important to execute a good audit (ICAEW, 2006). Moreover, it provides auditors with the ability to understand the essentiality of the audit (Öhman et al., 2006). More structured firms are especially concerned with maintaining balance (Power, 2003).

In contrast to the view by Broberg (2013) where structure and judgment are seen as complementaries to each other, Keen (1999)views these concepts as two opposite poles on a continuum. Where audit firms that implement structure tend to require the use of statistical sampling and formal scoring sheets, but also rules in perceiving the audit test results. Meanwhile, unstructured firms emphasize the need for individual judgments (Kinney, 1986). Keen (1999) terms the use of structure and judgment together as quasi-rationality and further argues that different tasks contain different compositions of intuitive and analytical thoughts. Meaning that different audit tasks are allocated at different points on the continuum (Keen, 1999). Despite the fact that the relationship between structure and judgment remains unclear (Agevall et al., 2018), the majority of the accounting literature argues that structure endangers the implementation of judgment (e.g. Kosmala MacLullich, 2001; Myers, 1997; Schroeder et al., 1996).

19

2.4 Audit Process

The audit process is a set of procedures and actions that are implemented to review a company. Auditors’ use the audit process to review that the processes and controls of the business operate correctly and that the financials of the company are in order (FAR, 2006). Structure has made it possible to collect and interpret large amounts of data more effectively and efficiently(Shumate & Brooks, 2001). Structure within the audit process is increasing along with the development of IT-systems which creates a more routine procedure of the audit process (Manson et al., 2001). Accordingly, with the increase of structure, there are increasing requirements on auditors to exercise professional judgment and apply a professional scepticism throughout the whole audit process (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001). A failure of applying a sufficient amount of judgment might lead to the risk of an improper audit opinion (Sayed Hussin, Iskandar, Saleh & Jaffar, 2017). Judgment in the audit process combines estimations and evaluations of outcomes and leads to decisions that auditors have to make (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001).

The audit begins when the client develops the financial statements and makes certain assertions of the numbers. The assertion could, for example, be that the management asserts that the revenues in the financial statements are complete or that a certain amount of costs exists (Guénin-Paracini, Malsch & Paillé, 2014). Every audit is performed differently since the undertaken actions will be dependent on the risk factors and effectiveness in the client’s internal control system (Sayed Hussin et al., 2017). The auditor must, during the entire audit process, identify that the client’s financial statements are free from any material misstatements due to fraud. Moreover, evaluation of fraud and fraud risks must be considered during all stages of the audit process (Sayed Hussin et al., 2017). The audit process consists of several activities that are executed by auditors to obtain evidence in order to provide an audit opinion (Guénin-Paracini et al., 2014). Audits are performed annually and are viewed as the exercise of looking backwards (Rezaee, Sharbatoghile, Elam & McMickle, 2002). The audit process consists of 3 stages: planning, execution and reporting (FAR, 2006).

20

2.4.1 Planning

The planning stage in the audit process can be viewed as an ongoing procedure. This is since unexpected situations or information can appear, causing auditors to rethink or change the audit strategy (FAR, 2006). Establishment of an audit plan is a requirement according to ISA (e.g. ISA 300; ISA 315). The objective of the planning stage is to decide the amount and what kind of evidence that is going to be reviewed. These plans should be based upon information regarding the client’s operations (Guénin-Paracini et al., 2014). Appropriate planning is crucial since it provides auditors with the ability to investigate risky areas (FAR, 2006). Further, appropriate planning helps to create the audit strategy but also form, identify and handle risks in a timely way so that the audit can be performed both efficiently and effectively (ISA 200). Failure of performing sufficient planning can lead to mistakes in the audit opinion or result in lack of time to perform the audit.

Judgment is especially important in the planning stage of the audit process (Nelson, 2009). Professional judgment is particularly important in this stage since the auditors must allocate audit hours to the various audits and their elements (Rodgers, Mubako & Hall, 2017). Structure is implemented in the planning stage for the use of checklists that are executed to guide the auditors throughout the audit process (Cushing & Loebbecke, 1986). The structure for each specific audit is set in the planning stage and is established so the audit process is completed in an effective and efficient manner (Bierstaker et al., 2001).

2.4.2 Execution

The execution stage consists of substantive testing, extensive tests of controls and transactions, and examination of the client’s management administration (Carrington, 2014). The auditor investigates the client’s business functions, payables, finance, human resources, investments, purchases, inventory management functions, and their revenue (FAR, 2006). The auditor must also control the existence and completeness of the client’s inventory (Janvrin et al., 2009). According to Pan and Seow (2016), the auditor must verify that the information provided from the client reflects the reality.

21

A test of controls investigates the effectiveness of the client’s internal controls (Desai, Desai, Libby & Srivastava, 2017) and ensures that the data is not misrepresented (ISA 200). The auditors need to obtain an in-depth understanding of the company's internal control (ISA 315), and guarantee that the functions are successfully performed (Desai et al., 2017). Tests of controls and transactions can be done through sampling, where less than a percent of a population is tested. Sampling is the most effective method for testing transactions (Colbert, 2001). Substantive tests are performed to obtain audit evidence regarding certain assertions (Appelbaum, Kogan & Vasarhelyi, 2017) and are made to detect material misstatements in the financial statements (ISA 200). Rezaee, Elam and Sharbatoghlie (2001) state that the aim of performing substantive tests is to control financial accounting validity and existence. One part of substantive testing is the testing of journal entries, where the auditor’s capability to identify fraud is dependent on whether he or she has access to all journal entries and other adjustments from the concerned period (Fay & Negangard, 2017).

Structure in the execution stage has increased the amount of collected data and helps to analyze the collected data properly. The structure increases the ability to get a deeper understanding of the client’s operations (Kokina & Davenport, 2017). Moreover, the structure in the execution process can help the auditor to detect material misstatements and reduce human errors (Issa, Sun & Vasarhelyi, 2016; Knechel, 2007).

2.4.3 Reporting

At the end of the audit, the auditor is expected to provide an audit opinion regarding the financial statements (ISA 700). The auditors summarize the collected audit evidence and provide an explanation of their work and observations (Omoteso, 2012). In the audit report, the auditors should make a statement whether they “recommend” or “not recommend” the establishment of the financial statements. This statement should be made based on whether the profit is used according to the management report, and whether the CEO and the board are free from liabilities (FAR, 2006). Lastly, the auditor must decide on how to proceed with the collected information and take actions based on his or her judgment. Further, judgment is crucial in the conclusion on whether the financial

22

statements show a correct view (Kosmala MacLullich, 2001). The auditor can issue four different audit reports; unmodified, modified, adverse and disclaimer. An unmodified report indicates that the financial statements are free from material misstatements, meanwhile a disclaimer report indicates the opposite (FAR, 2006).

2.5 Professional Scepticism as a Representation of Judgment

Professional scepticism is one aspect that represents professional judgment and is described as the product of the auditor’s judgment (Nelson, 2009). Professional judgment and professional scepticism are essential in the audit profession (Hurtt et al., 2013). According to ISA 200 paragraph 13, professional scepticism is “an attitude that includes a questioning mind, being alert to conditions which may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud and a critical assessment of audit evidence”. Moreover, Nelson (2009, p.1) describes the concept as “indicated by auditor judgments and decisions that reflect a heightened assessment of the risk that an assertion is incorrect, conditional on the information available to the auditor”. Professional scepticism is one of the substantial concepts in auditing practice (Hurtt, 2010), and is according to IAASB (2018) necessary to achieve a high-quality audit.

Professional scepticism is important in the detection of unethical behaviour by the client’s management (Grenier, 2017). Professional scepticism must be applied to be able to question the reliability of collected information and audit evidence (ISA 200). Moreover, professional scepticism is considered to be a fundamental element in the financial statement audit (Quadackers et al., 2014). Auditors should plan and perform an audit with professional scepticism to identify eventual material misstatements in the financial statements (ISA 200). Insufficient levels of professional scepticism in the financial statements can lead to the failure of detecting risks (Beasley, Carcello & Hermanson, 2001), which can result in a decrease of the audit quality (Sayed Hussin et al., 2017). Carpenter and Reimers (2013) state that when auditors apply professional scepticism, they are both effective and efficient in their fraud investigations.

Professional scepticism can be described through the neutral view and the presumptive doubt view (Nelson, 2009). The neutral view is explained as when the auditor assumes

23

the representation of the management to consist of no bias (Nelson, 2009; Popova, 2012). Through implementing the neutrality perspective, the auditor aims for a balance of the evidence that both supports and refutes the financial statements assertions (Quadackers et al., 2014). According to Cushing (2000), the auditor should be unbiased when forming their beliefs, meaning that there should be no bias in an either positive or negative direction. Moreover, Nelson (2009) explains the presumptive doubt perspective as an auditor’s attitude of expecting some level of bias or dishonesty in the management presentations until the opposite is being proved. When conducting the audit, the auditor should have a mindset that a possibility of material misstatements due to fraud could be present (Nelson, 2009). Thus, the presumptive doubt perspective puts the auditor’s focus on error-related evidence rather than on non-errors, e.g. changes in business conditions (Quadackers et al., 2014). Further, when adopting the presumptive doubt perspective, the minimum level of evidence needed to provide an audit opinion increases (Nelson, 2009).

2.5.1 State Scepticism

Hurtt et al. (2013) present a six characteristics model for professional scepticism. This model is developed to measure the professional scepticism of a person. Nevertheless, Robinson et al. (2018) argue that this model must be viewed as two parts where one part is state scepticism (a temporary condition caused by situational factors) and the other one is trait scepticism (stable characteristics of an individual). Where state scepticism is measured as the three characteristics Questioning Mind, Suspension of Judgment and Search for Knowledge. Meanwhile, the other three characteristics (Interpersonal Understanding, Self-Determining and Self-Confidence) refer to trait scepticism, individual characteristics of a person (Hurtt et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2018).

In prior literature (Anderson, Kadous & Koonce, 2004; Gramling, 1999; Hackenbrack & Nelson, 1996; Hirst, 1994; Houston, 1999; Robertson, 2010; Trompeter, 1994), professional scepticism is seen as either trait scepticism, state scepticism or both. Robinson et al. (2018) argue in their study that state scepticism is a separate construction from trait scepticism because of the specific nature of state scepticism compared to the general nature of trait scepticism. Professional scepticism as state scepticism indicates that some situations might warrant a higher level of professional scepticism compared to

24

other situations (Robinson et al., 2018). Additionally, Shaub (1996) argues that trait scepticism is not as important as state scepticism in the context of professional scepticism. This is since state scepticism shows a greater response in determining subjective trust of the client. State scepticism also shows a larger contribution to the applied professional scepticism (Shaub & Lawrence, 1996).

State scepticism is a formable, temporary condition that emerges from situational factors (Hurtt et al., 2013; Steyer, Schmitt & Eid, 1999). Comprehension of state scepticism is necessary in order to get an understanding of the interplay of environmental factors, professional scepticism and the behaviour of the auditor (Robinson et al., 2018). According to Steyer et al. (1999), state scepticism means that behaviour is dependent on specific conditions in each situation. The clients’ incentives affect the situational factors and further the auditors’ judgment and behaviour (Robinson et al., 2018). Moreover, Robinson et al. (2018) argue that state scepticism functions as a transition step between the situational factors and the sceptical behaviour of the auditor. Sceptical behaviour is adjusted by the nature of the situation in the audit. For example, when the risk of material misstatement is higher, the level of professional scepticism is higher (Robinson et al., 2018). Further, the professional scepticism is expected to increase in situations where the client is new, when the communication is poor, when the client experiences financial distress and when inaccuracies appear in the client’s inventory (Shaub & Lawrence, 1996).

2.5.2 Trait Scepticism

Despite the fact that professional scepticism and judgment are affected by situational factors (Robinson et al., 2018), they are also influenced by the individual characteristics (Broberg 2013; Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Power, 2003). Hurtt et al., (2013) refer to the individual characteristics as individual traits. According to Quadackers et al., (2014) they can also be referred to as individual trait scepticism. Traits are defined as individual and relative stable differences in thoughts, feelings and behaviour and are described as the centre of personality (Robinson et al., 2018). Since individual traits affect judgment and decisions (Humphrey & Moizer, 1990; Power, 2003), auditors with higher levels of trait scepticism would usually require more evidence to be convinced compared to auditors

25

with lower levels of trait scepticism (Quadackers et al., 2014). Rose (2007) argues that auditors with higher levels of trait scepticism increase their search in attendance of fraud conditions compared to auditors with low levels of trait scepticism. The difference in the levels of trait scepticism can be reduced through audit training (Rose, 2007).

2.5.3 Professional Scepticism in The Auditing Process

Professional scepticism must be maintained through the planning and executive stage of the audit process (ISA 200). In the audit process, the auditor must obtain an understanding of the client and the company’s operations to make assessments regarding existing risks. In order to make a critical assessment of the validity of the audit evidence, it is necessary that the auditor executes professional scepticism (Broberg, 2013). By executing professional scepticism, the auditor will question the reliability of the audit documents and other information obtained during the audit process (ISA 200).

An auditor must execute professional scepticism throughout the audit process to identify and assess risks of material misstatements, originated from fraud or errors (Nelson, 2009). Prior literature argues that risk assessment and audit planning are related to each other (Kaplan, 1985; Libby, 1985; Nelson, 2009). Professional scepticism in the planning stage is important since it can affect the initial planning of a client and further affect the audit opinion (Nelson, 2009). The overall evaluation of the client’s trustworthiness is performed in the planning stage which is made through investigating the company’s control environment (Shaub, 1996). Since auditors decide what type of audit evidence to collect in the planning stage (Guénin-Paracini et al., 2014), professional scepticism must be applied in order to produce a relevant audit plan (Hurtt et al., 2013). If the client's risk assessment is low during the planning stage, auditors’ professional scepticism will most likely decrease in the executive stage of the audit process (Hurtt et al., 2013).

In the executive stage of the audit process, professional scepticism is essential in order to be critical of the audit evidence (ISA 200). Auditors are required to reevaluate the risk level during the whole audit process to ensure that an appropriate level of professional scepticism is applied towards the collected audit evidence (Glover & Prawitt, 2014). What is described as an appropriate level of professional scepticism depends on the specific

26

audit situation that the auditor is involved in (Glover & Prawitt, 2014). This level should further be applied in the executive stage to achieve a high-quality audit (Glover & Prawitt, 2014; Hurtt et al., 2013).

In the reporting stage, professional scepticism is important to not generalize the evidence when making conclusions from the audit observation (ISA 200). Due to this, professional scepticism is an important factor in the decision-making and in order to conclude an audit opinion (Rodgers et al., 2017). In conclusion, professional scepticism is fundamental for the audit work when considering fraud risks of material misstatements (Nelson, 2009).

2.6 CAATs as a Representation of Structure

Computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs) are one representation of structure and can be defined as the major technological advancements and tools within auditing (Al- Hiyari, Said & Hattab, 2019). The use of CAATs has evolved over time as the use of technology has developed within the audit profession (Ramamoorthi & Weidenmier, 2004). Development of information technology, modern computing technology, and a globally and competitive market, drive together with the change towards a more automated audit (Al-Hiyari et al., 2019; Mahzan & Lymer, 2014). Many audit firms have opted to use sophisticated IT-tools and information techniques in order to develop their audit processes as well as improving their activities within the audit process. This increases the need for CAATs to continue to review and monitor tasks effectively and work in an innovative way (Ramamoorthi & Weidenmier, 2004).

Braun and Davis (2003) define the broad definition of CAATs as techniques that help auditors in the conduct of an audit. CAATs can further be explained as computer techniques that derive and analyze data from computer applications (Braun & Davis, 2003; Pedrosa et al., 2019), or as the use of specific software that can be implemented by the auditor to complete audits (Curtis & Payne, 2008; Janvrin et al., 2009; Siew et al., 2020). CAATs consist of several audit techniques that auditors can implement in their work. Voyager, IDEA, and ACL are a few software that the auditor can use to facilitate their work and make it more effective due to its automatization (Coman, Coman & Munteanu, 2018). However, Microsoft Word and Excel are the two most common