INCLUSIVE ONLINE SOCIAL PLAY

THROUGH NON-VERBAL

COMMUNICATION

How using participatory methods for creating non-verbal communication systems affects inclusive cooperation and cohabitation in online multiplayer games.

by

Daniel Velasquez Araque

Interaction design

Master Level, Two-year master 15hp

Semester 4 / 2020 Supervisor: Susan Kozel Examiner: Clint Heyer

ABSTRACT

This research focuses on the connection between voice-based interactions and harassment in online games, from the point of interaction design. It points out severe faults in privacy afforded by voice-based communication and explores beyond this medium to design a communication system that relies only on non-verbal

communication (NVC). Such system was co-created with the players supporting the idea that inclusion starts even in the early design stages. Through the playtesting of the NVC system the research shows the many ways in which the type of

communication impacts the game and how players experience cooperation,

cohabitation, and inclusion in online games. However, to achieve this, this research had to create a framework and mapping methods that focus on the players and their communicative intention. Hence, the “levels of multiplayer communication” is proposed as a tool to analyze and a method to design for communication in games, and it stands as a knowledge contribution along with the information acquired through its use.

TABLE OF CONTENT

1. OUTLINE ... 5 1.1. INTRODUCTION ... 5 1.2. RESEARCH QUESTION ... 7 1.3. ETHICAL CONCERNS ... 7 Health Concerns ... 8 2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 92.1. Understanding the role of the player ... 9

2.2. Self-determination theory and the need for relatedness ... 10

2.3. MDA framework and fellowship ... 11

2.4. Immersion theories in games ... 13

2.5. Shared involvement: cohabitation and cooperation in online multiplayer games ... 14

2.6. The magic circle ... 15

2.7. Inter-immersion ... 16

2.8. Games as a language ... 16

2.9. Communication problems in online games... 18

2.10. Harassment and gender politics in online games ... 18

2.11. Non-verbal communication (NVC) ... 21

2.11.1. Non-verbal communication and semiotics ... 21

2.11.2. Extralinguistic gestures and NVC forms ... 22

2.12. Pings: canonical examples of collaborative kinesics in games ... 24

2.12.1. Portal 2, and its ping tool ... 25

2.12.2. Apex Legends, and its ping system ... 26

3. METHODOLOGY ... 29

3.1. Research through design ... 29

4. METHODS... 30

4.1. The impact of COVID19 on the methods ... 30

4.2. Digital observation methods ... 30

4.2.1. Fly-on-the-wall ... 30 4.2.2. Holistic observation ... 31 4.3. Secondary Research ... 31 4.4. Immersive interviews ... 32 4.5. Co-design Workshops ... 32 4.5.1. Co-design probes ... 33 4.6. Physical prototypes ... 33 5. DESIGN PROCESS ... 35

5.1. Discover ... 35

5.1.1. Initial research: The context of online games with voice-based communication. ... 35

5.1.2 User observation: digital fly-on-the-wall ... 37

5.1.3. Conclusions: ... 39

5.2. Define ... 40

5.2.1. First activity: players revealing insights about cooperative communication ... 41

5.2.2. Second activity: participatory mapping session with the three levels of online multiplayer communication. ... 43

5.2.3. Conclusions: ... 48

5.3. Develop... 48

5.3.1. Co-designing NVC on a digital game ... 49

5.3.2. Transferring the NVC co-creation from digital to physical ... 50

5.4. Deliver ... 53

5.4.1. NVC co-design ... 53

5.4.2. Design insights and outcomes for the “levels of multiplayer communication” framework. ... 59

5.5. Final design and its place in “game design” ... 62

6. DISCUSSION ... 64

6.1. NVC interactions promoting inclusion and cohabitation in online multiplayer games ... 64

6.2. NVC affects on cooperation and performance ... 65

6.3. Observations about the “levels of multiplayer communication” ... 65

6.3.1. The "levels of multiplayer communication" as a method for mapping online communications between strangers, but still not yet a fully-fledged framework ... 66

6.3.2. Acknowledging the limitations of physical playtesting with participants who are not strangers ... 67

6.3.3. How transferring the game from physical to digital affects the experience and the ideation of NVC systems ... 67

6.4. Avatars and the limits of virtual bodies ... 68

7. CONCLUSION ... 70

8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 71

1. OUTLINE

1.1. INTRODUCTION

Online games are a growing niche for players seeking ludic entertainment from their homes, wanting to connect with other players, and fulfill their psychological need of relatedness and collaborative challenge completion. Nowadays with current events and the arrival of 5G technologies, it is expected that online games will continue to flourish in the near future, making games that can accommodate massive amounts of players in the digital game worlds a standard. While innovations in graphics and connective technologies in online games have seen a rapid increase, there are still severe problems regarding player-to-player interactions and

collaborative communication tools for virtual teamwork. Even though game

designers have given players a way to create customizable avatars that represent them in the games, most games still do not offer a way for players to communicate other than using their voice.

VoIP (Voice over internet protocol) communication via microphone and headphones has been one of the most common choices among players, and while it works well with players who know one another outside the game, it has caused several problems when matching players who don't previously know each other. Voice-based player-to-player interactions have opened the door to racism, exclusion, and frustration (Fox & Tang 2014; 2017) that can affect players well beyond the confines of the "magic circle" (Huizinga, 1955) created during gameplay. Online games that set players in small teams to compete against other teams will randomly pick teammates from an international pool of players. In order to collaborate, players communicate through microphones speaking a common language, English in most cases, and it is the personal information embedded in one's voice that some players use to attack others. Someone's voice is a fragile part of a person that exposes personal information like one's gender, age, and ethnicity. This is something that some players have used as an excuse for harassment, making players shy away from these online games defeating the nature of games as enjoyable autotelic experiences. There have been authors who have explored the documented harassment of female players (Fox & Tang, 2017), and how others are attacked for their accent or English communication skills are being harassed because of their accent (Murnion et al., 2018), as these games are commonly played in English.

When players know each other, voice-chat tends to be an enjoyable social experience in games but studies have identified voice-based interactions as a source of distraction (Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016) that affects virtual teamwork and has a measured impact in team performance. These problems in player-to-player

interaction make it clear that game design has an interaction design problem, and this problem continues to increase with the massive number of players that engage in

these games on a daily basis. Digital gaming platforms like Steam (Valve, 2003) host a total of 1 billion users worldwide (Lanier, 2019), with a total of 90 million monthly active users, and reports having as much as 26 million simultaneous users playing together (Valve, 2020). This critical number of users has made the problem more urgent and raises questions for interaction design towards the design of better user-to-user communicative interactions without the faults currently present in voice-based interactions. One of the most pressing reasons to do so is that communication is indispensable for collaborative play to happen (Salen, Zimmerman, 2014) and

because of its impact on the psychological well-being of the players (Ryan, Rigby, & Przybylski, 2006; Walz & Deterding, 2015). Designing beyond voice-based

communication promises then to promote inclusion and focus communication on enhancing virtual teamwork, social flow (Walker, 2010) play performance.

Designing these communicative interactions on par with the player's response to the game mechanics could provide a shared immersion, by involving players and analyzing their interactions within the context of the game early on. Therefore, this research positions this process in the early stages of playtesting. In doing so, the non-verbal communication systems avoid the problems that occur in some games design processes, in which designers create the whole game and then use microphones not as a proactive decision to improve communication, but as an excuse for not designing contextual communication systems for the game.

The presented points would make this project as much about inclusion as it is about expanding the knowledge related to developing methods for cooperation and cohabitation in online games that do not depend on using the player's voice.

1.2. RESEARCH QUESTION

How using participatory methods for creating non-verbal communication systems affects inclusive cooperation and cohabitation in online multiplayer games.

1.3. ETHICAL CONCERNS

This research is dealing with the impact of in-game communication on the mental well-being of players and how the lack of privacy regarding the player's voice is leading to harassment and exclusion. To respect any individuals that participate in the design process, and to be coherent with the problem that is being researched, this project will follow specific guidelines to ensure that any documentation of activities involving participants will have their consent and will be safely guarded. Using the IEEE Code of Ethics as a basis and to be in compliance with GDPR, there are some key implications to cover, therefore it will be agreed to:

1. As explained in the project overview, the voice gives away too much personal information, therefore the main method to gather data will be written notes, and photography and video will only be used if absolutely needed and agreed by the participants.

2. All users and participants will be informed of the methods used to document the information gathered in any exchange with them and will agree with these methods by signing the corresponding documents that ensure they understand and accept these terms.

3. To ensure the safety of any person to be interviewed or any workshop participants, all information gathered will be kept safely in physical hard drives for a duration of one year.

4. Since the research may happen in collaboration with a video game studio, this will be disclosed with participants or affected parties to avoid real or perceived conflicts of interest.

5. Improve the understanding by individuals and society of the capabilities and societal implications of conventional and emerging technologies, including intelligent systems.

6. Maintain and improve our technical competence and to undertake

technological tasks for others only if qualified by training or experience, or after full disclosure of pertinent limitations.

7. Seek, accept, and offer honest criticism of technical work, to acknowledge and correct errors, and to credit properly the contributions of others.

8. Treat fairly all persons and to not engage in acts of discrimination based on race, religion, gender, disability, age, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.

9. Avoid injuring others, their property, reputation, or employment by false or malicious action.

Health

Concerns

Due to 2020's COVID19 outbreak, this research had to be continuously reframed to ensure that participants would not be exposed to any situation that could risk their health. The specific measures that were taken will be explained in the "Methods" section.

To ensure that workshop participants are not in any risk, all the activities that involved physical components were reframed. Instead the physical components were delivered to the participants, then the package was isolated for at least 7 days. This was done in accordance to the information published by the BBC (Gray, 2020) which said that

“Sars-CoV-2 could survive and remain infectious on smooth surfaces including plastic, stainless steel, glass, ceramics and latex gloves for up to seven days. They found they could not obtain infectious viral particles from cotton clothing after four days and that no virus could be obtained from paper surface after five days.” (Gray, 2020).

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1. Understanding the role of the player

As the objective of this research is to contribute to the creation of inclusive and enjoyable multiplayer experiences, it seems appropriate to discuss relevant studies and theories about multiplayer games. These studies allow to position the importance of sharing play with others and inquire about what drives players to seek these experiences.

The first concept to be discussed is one that is continuously repeated throughout this work, and that is the concept of "player". From the point of view of interaction design, the player can be defined as "the human agent, or agents, that engage with the game system." (Calleja, 2011, p.11). As Calleja mentions, understanding the player only as the user who engages with a game artifact is a rather limited view, mainly because players are a particular type of user who willingly engages in an autotelic experience. The term autotelic, proposed by Csikszentmihalyi (1990), is common in game theory as it describes self-contained activities that users engage with for the sole enjoyment gained from the activity itself. The opposite of autotelic engagement would be an exotelic experience, in which users engage in an activity influenced by extrinsic or external motivations, like deciding to ride a bicycle to get to a

destination. Games are non-utilitarian experiences; you don't play a game to

accomplish anything outside of the game, they are a dialog between players and the game, isolated from the outside world, and exist within a magic circle (Huizinga, 1955). The lack of instrumentality in games, other than enjoyment, means that players are not obliged to endure unpleasant user experiences. This particularity of play means that a player can stop playing whenever the experience is no longer enjoyable, while the bicycle user from the previous example must endure an uncomfortable ride to get to the intended destination. Sicart (2014) also points this out by saying that "players and a certain will to play are needed to engage in play." (Sicart, 2014, p.8), which becomes a problem when designing games, as a less than ideal gaming experience means players will quit and uninstall the games to never come back.

This might not have been a problem in the era of analog and offline games, but now that online multiplayer games function as "lifestyle games" (Cabell, 2020), games depend on players to exist. Online games do not expire after a single game session, instead they offer unlimited opportunities for players to complete cooperative challenges, compete against each other, or to play freely inside virtual playgrounds like Minecraft (Mojang Studios, 2009) or Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013). Most contemporary games depend on player communities because without them, multiplayer experiences would not exist, which has changed the role of the

player in digital games. Much like in analog games, players do not only experience the game, instead they actively shape the ludic experience for fellow players. A good game can be an enjoyable or unpleasant experience depending on the other players. The main difference with physical or analog games is that people usually get to choose who they play with, while in online games this happens randomly through matchmaking systems.

Therefore, if enjoyment is the key experiential goal that keeps players engaged with the game and with each other, it is important to understand the theories behind it and why players seek these experiences.

2.2. Self-determination theory and the need for

relatedness

One of the most influential theories of enjoyment in game design comes from psychology. Self-determination theory, proposed by Deci & Ryan (1985, 2000), explores the psychological motivations that continuously push individuals to take part in these autotelic activities. The findings of their research traced back the experience of fun and engagement to be caused by the satisfaction of core psychological needs, these needs are competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Researches have shown that independent of the game that is played or its genre, the satisfaction of these core needs through gameplay is closely related to pleasurable experiences and enjoyment (Ryan, Rigby, & Przybylski, 2006; Walz & Deterding, 2015). Being in the first level of Maslow's hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943), these core needs help to explain the pleasurable experience players find in games. Each one of these needs must be expanded to understand how they impact the player's need for multiplayer experiences.

The first of these core needs is competence, which is "our fundamental need to

feel effective and successful in the moment-to-moment activities of life" (Walz &

Deterding, 2015. p.120). The need for competence drives people to seek challenges within the range of their skills and overcoming these challenges results in feelings of personal growth, success, and mastery. (Ryan and Deci, 2000). This is closely related to Csikszentmihalyi's theory of flow (1990), which describes flow as an "optimal

experience" or as an intrinsic state of high engagement. This state is achieved when a

person actively chooses to participate in a challenging activity with a difficulty level on par with their skills, allowing the person to successfully complete it.

Autonomy is the basic need for agency, to be able to act independently and to freely choose a desired course of action. This can be seen in games as having control over the game character, choosing which mechanics it will perform and when it will perform them. While this is present in every game, there are certain game genres that are more akin to this psychological need, like role-playing games (RPGs), virtual playgrounds like the aforementioned Minecraft (Mojang Studios, 2009), or massive

multiplayer online games (MMOs) where the player can customize how their character looks, and the weapons and character class they will play.

Lastly, relatedness is understood as the universal human need to interact and connect with others, also described as "our fundamental need to feel supported by others; to feel that "I matter" to others and that they matter to me" (Walz & Deterding, 2015. p.121). Then players feel the need to play games with others, against others, and for others, and in doing so the players end up fulfilling the need for competence and autonomy as well. This is done by competing against others with similar levels of proficiency in the game, as well as strategizing with their teammates, choosing the best course of action to defeat their opponents, and the tools to do so. According to Walz and Deterding (2015) the players satisfy their feel for relatedness when they feel that others are supportive of their need for competence and autonomy. It is also valid to point out that the same study (Walz and Deterding, 2015) shows that the need for relatedness can be fulfilled by non-player characters (NPCs), but other studies (Salen & Zimmerman 2004; Bowman, 2010, 2018; Calleja, 2011) point out that players experience a greater enjoyment and fulfillment of their core needs when they play with other human players, as one of the participants interviewed in Calleja's work (2011) points out: "I think what really strikes me is knowing that all these thousands of characters running around are actually people stuck to their PCs all over the world. There through my monitor is a whole living world" (Calleja, 2011, p.94).

The need for relatedness is the most relevant need for this research, because before analyzing how players communicate it is necessary to understand what motivates players to engage in online multiplayer games. Another reason that makes the need for relatedness is how it affects the other core needs and ends up being a conduit that ends up fulfilling the three core needs more effectively. Therefore, the next step is to review other relatedness theories that involve engagement, immersion, and presence.

2.3. MDA framework and fellowship

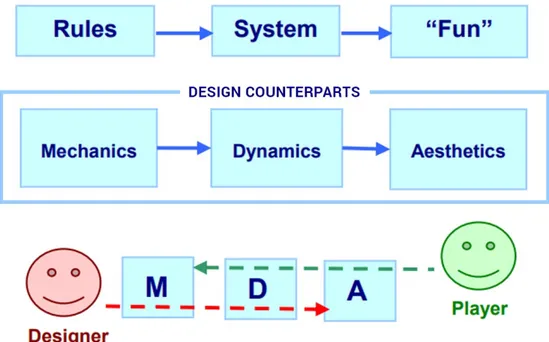

The MDA framework (Hunicke, LeBlanc & Zubek, 2004) is one of the most accepted theories for design games by focusing on the player experiential goals of the games. This is achieved by breaking down the act of game consumption into three main components they call rules, system and fun, and then propose the design counterpart for each concept, by respectively proposing "mechanics, dynamics and

Figure 1. MDA model. Source: Hunicke, LeBlanc & Zubek, 2004

In this framework (Fig. 1), mechanics are the basic interactions that players can perform, which define what they can and cannot do inside the game. Dynamics are the run-time behavior of the mechanics, or systemic relation they create during a game session. Aesthetics are the desired emotional response that should be evoked on the players when they play the game.

This framework situates games as artifacts instead of media and explains the different perspectives in which designers and players experience these game artifacts and directs designers to take on a human-centered design focus on game design. In practice, the MDA framework starts by setting the aesthetic goals of the game before even starting to design the mechanics and dynamics of a game. What makes this more relevant for this research is how Hunicke, LeBlanc & Zubek took the intrinsic

concept of "fun" and expanded it with the concept of aesthetics, by arguing that "Talking about games and play is hard because the vocabulary we use is relatively limited." and continue by saying that "In describing the aesthetics of a game, we want to move away from words like fun and gameplay towards a more directed vocabulary." (Hunicke, LeBlanc & Zubek, 2004, p.2).

The authors then propose a set of eight different aesthetics that account for different experiences of fun one can have during play. These are (1) Sensation or game as sense-pleasure. (2) Fantasy or game as make-believe. (3) Narrative or game as drama. (4) Challenge or game as an obstacle course. (5) Fellowship or game as a social framework. (6) Discovery or game as uncharted territory. (7) Expression or game as self-discovery. (8) Submission or game as pastime. (Hunicke, LeBlanc & Zubek, 2004, p.2).

The authors highlight the aesthetic of fellowship for being the source of

others. The article uses the following example for the aesthetic of fellowship

"Charades and Quake are both competitive. They succeed when the various teams or players in these games are emotionally invested in defeating each other." (Hunicke, LeBlanc & Zubek, 2004, p.3). The parallel between a classic analog game and a MMO game helps to show how players find the relatedness satisfaction in both physical and digital form, by working together with their teams and competing against others.

The idea of breaking down concepts like fun and immersion has continuously proved that players seek the enjoyment experienced from fellowship, relatedness, and shared involvement.

2.4. Immersion theories in games

Discussing game enjoyment through social interactions or relatedness means expanding the idea of game affecting players into a shared experience where player-to-player interactions affect in equal or even more profound manner the gameplay experience and player immersion.

Immersion has a history of sparking very enthusiastic debates among designers and academics, some refer to it in terms of how "the player's mind forgets that it is being subjected to entertainment and instead accepts what it perceives as reality." (François Dominic Laramée. as cited in Salen & Zimmerman, 2004, p.443). The line of thought of the previous interpretation of immersion often suggests that total immersion happens when players forget they are playing a game and truly believe that they are part of the game world. Salen & Zimmerman (2004) oppose this idea of total immersion by calling it the immersive fallacy, arguing that "the very thing that makes their activity 'play' is that they also know they are participating within a constructed reality" (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004, p.445). Salen and Zimmerman express that the player's awareness of being immersed in a game is key for play to happen and maintain the playful mindset, and to present their case against immersion as sensory transportation they say that the game Tetris (Pajitnov, 1985) is a good way to exemplify that "immersion is not tied to a sensory replication of reality" (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003, p.170). This research will avoid falling into the pits of the

immersive fallacy. Instead, Immersion will be understood as a "blending of a variety

of experiential phenomena afforded by involving gameplay." (Calleja, 2011, p.3). Just like how the MDA framework broke down the concept of fun into different aesthetics, authors like Calleja (2011), Bowman (2018), Salen and Zimmerman (2004) expanded the concept of immersion by proposing different categories that account for this phenomenon.

Calleja (2011) proposes to break down immersion in his involvement model, which he created after three years of qualitative research on MMO games and culminated in six divisions that account for the different aspects of the game that continuously engage players during gameplay and motivates them to return to the

game with a promise of core need satisfaction. "The six dimensions of the player involvement model are kinesthetic involvement, spatial involvement, shared

involvement, narrative involvement, affective involvement, and ludic involvement." (Calleja, 2011, p.38). Out of these interconnected dimensions, the most relevant path to immersion for this research is the shared involvement which will be explored further.

2.5. Shared involvement: cohabitation and cooperation in

online multiplayer games

Calleja describes the dimension of shared involvement as "the engagement derived from awareness of and interaction with other agents in a game environment, whether they are human- or computer-controlled." (Calleja, 2011, p.112). The author describes how players have different play experiences when they are sharing the game with others, and documents the player's behaviors when they know that the other characters on screen are actually the game avatars of other players instead of mindless scripted characters. As one the interviewed players expressed "It somehow makes the experience more immersive/intense knowing that there's a real person behind the avatar" (Calleja, 2011, p.101). The multiplayer experience introduces the aesthetic of fellowship, an aspect as shared play that enriches the whole play

experience as players have a direct impact on each other's enjoyment of the game. Calleja unfolds this by offering three sub-dimensions of shared involvement:

cohabitation, cooperation, and competition. Out of these, the first two are the most

influential for the research on teamwork and inclusion.

Cohabitation comprises the implications of sharing a digital world with other players. As MMOs tend to have NPCs to populate their various spaces, it is usually recognizable when a player meets another avatar controlled by another human. While NPC characters offer a sense of cohabitation it is the human players that offer a more potent and meaningful impact. One key characteristic that Calleja mentions is that when players create their characters, they must give it a name that cannot be changed and is used for as long as the game is played. This leads to players being able to recognize each other and form play communities named "guilds", creating a unique in-game culture, and all of this leads to players to be very mindful of their actions inside the game. Players tend to gain reputation according to their behavior and guilds can band together to make the play experience for players who do not act according to the in-game culture. "Some guilds or outfits keep “kill on sight” lists for players whose actions are deemed to be unacceptable… therefore, one's social

standing tends to have a significant impact on the decisions players make during actual gameplay" (Calleja, 2011, p.103). This social mechanic usually keeps users from harassing each other, but at the same time there is nothing stopping guilds from harassing lone players who are either new to the game or do not belong to an existing guild. It is important to understand the cohabitation theory for multiplayer games as this will be crucial for designing methods of communications for this context.

Cooperation is an important aspect of multiplayer games, which covers how players choose to work together as teams either because the game mechanics affords it or because the players have common goals they can achieve together. Either way, the author highlights that the two most important elements of this dimension are communication and teamwork. Calleja talks about the experience of playing offline multiplayer games by saying "The pleasure of these so-called co-op games in the same physical location lies in the immediate interaction players have with each other, making it easier to coordinate their efforts both verbally and by seeing each other's screen" (Calleja, 2011, p.104). In the case of online games cooperation is more challenging given that players do not share the same physical space and any type of interaction between the players must be mediated by the game itself. "teamwork requires a state of seamless communication and cooperation that can be seen as the pinnacle of real-time, networked collaboration" (Calleja, 2011, p.105). Effective communication between players is necessary for teamwork, and according to Calleja's research, players stated that the most enjoyable moments in these games were when they achieved their goals as a team, and the players interviewed consistently emphasized that cooperative gameplay was far more pleasurable than solo-competitive play.

2.6. The magic circle

This research continuously borrows the concept of the "magic circle", originally coined by Johan Huizinga in his work "Homo Ludens" (1955) to describe how the play appropriates the space where it takes place, and sets a spatial, temporal and psychological boundary that separates it from the real world (Calleja, 2011). This happens through the playful mindset of the players and their commitment to a set of rules proposed by the game, rules that may clash with the ones that govern the world outside of play. This theory is widely accepted among game designers and

academics, including Salen and Zimmerman (2004), who comment on it by saying: "Although the magic circle is merely one of the examples in Huizinga's list of "play-grounds," the term is used here as shorthand for the idea of a special place in time and space created by a game … As a closed circle, the space it circumscribes is enclosed and separate from the real world … The magic circle inscribes a space that is repeatable, a space both limited and limitless. In short, a finite space with infinite possibility." (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004, p.95-96).

It is important to consider this phenomenon when discussing social play because the magic circle is created by the players when they decide to engage in play, making it their conscious decision to enter this ephemeral space governed by the rules of the game (Juul, 2008). Moreover, players draw each other deeper into the playful mindset by validating each other's behaviors inside the magic circle, which gives birth to other phenomena like inter-immersion (Pohjola, 2004).

2.7. Inter-immersion

Bowman (2018) also addresses how cohabitation and cooperation can affect the behavior of players who participate in multiplayer games through the phenomenon of

inter-immersion (Pohjola, 2004). Inter-immersion is described as "the ability for

players to draw one another into deeper states of immersion through portrayals of character" (Bowman, 2018, p.32). Even though the idea of inter-immersion comes from live action role-playing games (LARPs), research (Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016) shows that it is also present in MMO games when players validate each other's roles in cooperative play. When players team up they select different player classes which can be offensive, defensive or support, and the class players choose determines their role on the team. Then Inter-immersion occurs when the players acknowledge each other on their roles, making them feel needed, important for the team dynamics, and satisfying their need for relatedness and competence.

2.8. Games as a language

Online games overcome the boundaries of geographic location to create digital playgrounds for global players. This means that players join game sessions from all over the world and must communicate effectively even with their different cultural backgrounds, languages, genders, and ethnicities. This fact might be an obstacle for effective cooperation and cohabitation of game worlds, but the fact is that players always find ways to communicate through the game. Players use the existing game mechanics to communicate and when these are not enough, they use the game as a language and appropriate the game mechanics for this purpose.

Figure X. Illustration of Tic-Tac-Toe

Salen and Zimmerman (2004) explore this in the context of a Tic-Tac-Toe game and explain that "players can sit down and play Tic-Tac-Toe even if they don't share the same native tongue, because they both know the "language" of the game". (Salen and Zimmerman, 2004, p.). This communication happens because both players, regardless of their backgrounds, are immersed in the context of the game, and the specific rules of the game define what they as players can and cannot do, hence,

determining what communication can take place. Players understand that they must place Xs or Os in the grid and understand their meaning, which is different from the meaning such symbols would have in a game of Scrabble. "Marking Xs and Os on empty grid squares is how Tic-Tac-Toe players "speak" to each other in the language of the game".

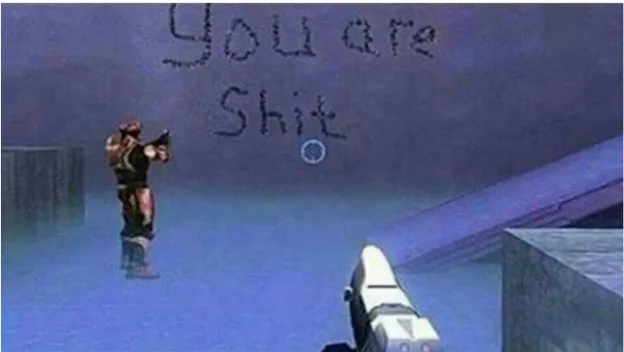

Another example that will be offered is the player appropriation of game mechanics to go beyond the communicative boundaries of a game. Sicart (2014) explains in detail the characteristics of play, and one that is quite evident in online games is its carnivalesque nature. When referring to this unique characteristic he says that "play appropriates events, structures, and institutions to mock them and trivialize them" (Sicart, 2014, p.3). This is exactly what happened in Halo 2 (Bungie, 2004), a renowned game part of a successful franchise characterized by its first-person shooter mechanics, futuristic science fiction setting and engaging lore. While the first

installment did not allow for online gameplay, the sequel introduced online competitive matches that faced teams against each other. The only method for communication between players was through voice chat, which allowed the players of the same team to talk among themselves. Since the communication between teams was limited, the player's appropriated the shooting mechanic to leave each other messages (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Screenshot of Halo 2 (Bungie, 2004) captured by an anonymous player. While the example has some graphic language, it helps to illustrate two points; first, how the creativity of players prevails in the search of ways to communicate, proving yet again that appropriation is a key characteristic of play (Sicart, 2014). The second, is the harsh and toxic way in which players communicate in the online multiplayer sessions, due to the competitive nature of the game. The carnivalesque nature of play mixed with the player anonymity afforded by online games can also be a catalyst for negative social interactions.

2.9. Communication problems in online games

The first multiplayer games were played at arcades in colorful game cabinets and at home in gaming consoles, where players invited their friends over to share the couch and play games side by side. This was due to the limits of the games, as the players needed to be co-located and physically connected to the gaming console to be able to play together (Fox & Tang, 2014). With the arrival of online games,

developers were tasked with an interesting interaction design endeavor of transferring the "couch multiplayer experience" to the digital medium.

Online multiplayer gave birth to virtual game worlds that host thousands of players, which was an outstanding achievement and a milestone for multiplayer games. Nonetheless, it was also the origin of a problem, or more precisely, it made a pre-existing problem in online games even more severe; multiplayer games require player-to-player interactions and there had been little progress in designing for such interactions compared to the growth in the maximum number of players a game could host. When multiplayer transitioned from local to online, designers opted for text-based communication for games but soon they realized that for fast paced games, typing was getting in the way of optimal gameplay. Voice-chat or Voice over IP (VoIP) seemed like a viable option to recreate the local multiplayer experience over the internet, given that players do not usually engage in visual contact with each other while playing locally. There were two main problems with the voice-chat approach for player embodiment, the first is not accounting for extralinguistic gestures or non-verbal communication, and second, the breach in personal privacy. Both will be explored in the following sections.

2.10. Harassment and gender politics in online games

As previously mentioned, local gaming or the "couch multiplayer experience" was carried out in a shared physical space. This meant that players would know each other before being engaged in play and there is a pre-existing relationship between them. However, the transition from offline to online changed this paradigm of playing with friends to playing with strangers, in other words, "rather than playing with another individual in the same physical space, now games are shared with faceless strangers around the world" (Fox & Tang, 2014, p.1). To protect the players privacy and to uphold the playful mindset afforded by the game, online gamedevelopers allowed players to create and customize their in-game avatars. Players can usually choose from a roster of pre-designed characters or even customize them to the point where they can choose their avatar's name, gender, ethnicity, clothing, and in the case of fantasy MMOs their fantasy race (Fig. 3). This practice worked in games that used text-based communication, but when games rely on voice-chat to

communicate the player's privacy is partially compromised as there is no feature or mechanic to protect the information that is embedded in the human voice.

Figure 3. Character creation screenshot from Elders Scrolls Online (Bethesda, 2014) Revealing one's voice to strangers gives away a vast amount of paralinguistic information linked to the speaker's identity. Schuller (2011, p.2) divides this

information in two categories of speaker states and traits. Schuller describes how on the one hand, the speaker states are characteristics that change over time, even during a conversation, like intimacy, deception, emotion, interest, intoxication, sleepiness,

health state, and stress. On the other hand, the speaker traits give away more

permanent information about the players, some of them are age, gender, ethnicity,

height, language, and personality. This information then can be used by the

interlocutors to break the magic circle by using sensitive information from the real world to harass players and affect them in ways that go beyond the game.

Fox & Tang (2014) point out that harassment is more likely in online games due to the anonymity, they say "anonymity has important implications for how

communication transpires in these spaces as it facilitates harassment and other forms of negative interaction." (Fox & Tang, 2014, p.1). Then the same measures that developers use to protect players' identities end up increasing the likelihood of harassment. This toxic behavior happens due to the idea that what happens during play doesn't have repercussions outside the magic circle, as Fox and Tang

note, "Online games also represent the myth of the offline/online dichotomy, wherein people believe online interactions cannot have a "real" impact because they do not take place in the 'real world'” (Fox & Tang, 2017, p.5). Therefore, the only repercussions of negative behavior would come from breaking any cohabitation rules established by the players in their internal game culture. The problem is that ‘‘Video game culture has privileged the default gamer, the white male, leading to the

maintenance of whiteness and masculinity in this virtual setting’’ (Gray, 2012, p. 262). Gray points how games have been mainly targeted to a male audience, even though that research shows (Entertainment Software Association, 2015) that female players account for approximately 40% of video game consumption. The focus on male audiences continuously affects the portrayal of male characters as protagonists

and female characters as support roles, victims, or romantic companions (Fox & Tang, 2014; Williams, Martins, Consalvo, & Ivory, 2009). The affects of this gender depiction can be seen in play communities where some perceive female players as an oddity, while others perceive them as trespassers (Yee, 2006).

In experiments carried out by Kuznekoff and Rose (2013), the researchers played an MMO game in anonymity and interacted with the other anonymous players

through voice-chat, using pre-recorded female voices. The outcome of the experiment was that female pre-recorded voices received three times the amount of harassing comments compared to the male pre-recorded voices. In subsequent research, Fox and Tang (2013) interviewed online players, asking them to discuss the last instance of verbal harassment they had witnessed. The outcome showed that “10% of these incidents reported sexist remarks ranging from traditional sexism (e.g.,‘get back in

the kitchen’) to sexual harassment (e.g., ‘show me your tits’)”(Fox & Tang, 2014.,

p.2). Such negative experiences are driving away female players from participating in online games because even if not all interactions end harassment, the possibility of it acts as a deterrent for joining these games. Fox & Tang comment on this by saying that “women may miss out on the sense of belonging experienced by male gamers and instead experience ostracism and harassment because of their sex” (Fox & Tang, 2014, p.2). As the previous statement points out, female players are playing the same game as the male players but having a completely different experience —for the most part a rather unpleasant one— which defeats the purpose of the autotelic experience by neglecting them from the feeling of fellowship the game is supposed to afford. Further research on the topic of harassment in online games shows that female players are not the only target. “Although we focused on individuals who identify as women, players may also be targeted based on race, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, other aspects of gender identity, or the intersectionality of various identities” (Fox & Tang, 2017, p.12). As numerous researchers point out (Fox & Tang, 2013; 2014; 2017; Gray, 2012; Williams, Martins, Consalvo, & Ivory, 2009) female players and minorities are harassed in online games because of private information that game developers should be protecting.

The presented information helps to highlight one of the key points of this thesis; how voice-based communication is exposing the speaker’s traits and states, and due to the toxic culture of online games afforded by anonymity and lack of repercussions , other players are using this private information to harass players based on their sex, gender, age, ethnicity, nationality and other sensitive data afforded by one’s voice. This situation led this research to go beyond voice-based communication to seek out alternative solutions for player-to-player interactions that afford effective cooperation and allow for expressive interactions. The answer to this ended up being interactions based on non-verbal communication.

2.11. Non-verbal communication (NVC)

The previous sections mentioned how the decision to implement voice-chat as a substitute for the “couch multiplayer experience” ended up neglecting non-verbal communication (NVC). More precisely, like paralinguistic and extralinguistic information (Argyle, 1988). As pointed out by Kujanpää, & Manninen (2003) “ if players share the same physical space, they can yell and give visual signals at the top of their computer screens to convey messages to other players” (Kujanpää, &

Manninen, 2003, p.2). While verbal communication is still mentioned in the previous quote, the authors also suggest that cooperative interactions are more nuanced when these include extralinguistic gestures. These gestures can take many forms, like players pointing at the screen (Calleja, 2011) or using methods that go beyond spoken language. The following paragraphs will explore this realm of communication as it is fundamental for the design process explored for in this research, hence making it necessary to expand on gestures theory and the different forms of NVC can take.

2.11.1. Non-verbal communication and semiotics

The study of communication beyond language has been tackled from many different areas of knowledge and in many forms (Manninen, 2003; Churchill et al., 2001). It has been studied as paralinguistics by George L. Trager in the 1950s while analyzing how nuanced variations of utterance can affect the formation of meaning. At the same time, NVC can also act as a companion to verbal communication in the form of extralinguistic information, which makes NVC invaluable to decode the meaning of a message. Other areas like semiotics have studied NVC as signs that can convey complete messages without relying on linguistics. Shannon & Weaver (1949) made a significant contribution to semiotic and user interaction in their research for the phone company Bell. They created a communication model meant to explain telephone interactions (Fig. 4) that is still used in semiotics and linguistics.

Figure 4. Shannon & Weaver (1949) model of communication.

The model not only accounts for the lack of co-location between interlocutors, but also explores the concept of encoding and decoding the message. This means the sender has the intention to communicate a message but must use a code to transform it into a sign. Such signs can take any form, like of spoken language, electric signals, or any type of signifier. However, the sender must keep in mind that any receiver must have the skills to decode the sign for successful communication to take place. Something worth pointing out is that the source does not need to be a human, static

signs and objects can trigger semiosis (De Souza, 2005). This happens every day without the need of verbal communication, just how seeing or smelling smoke can communicate there’s fire nearby, or how the change of color in traffic lights

communicates when cars must stop. Similarly, people can encode messages without exclusively through extralinguistic gestures, which will be explained in the next section.

2.11.2. Extralinguistic gestures and NVC forms

Gestures are forms non-verbal embodied communication between actors who take part in a dialog, manifesting their presence as “deliberate expressiveness” (Kendon, 2004). Furthermore, gestures can be used to carry out full conversation, or they can be used along verbal communication for different purposes, like (1) adding

information, (2) specifying or correct the meaning of something being said, (3) creating representations of what was discussed, (4) laying out spatial configurations or patterns of actions, and (5) referencing objects spatially (Kendon, 2004; Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016). One particular characteristic of gesture is that for the most part, they are communicated visually, which implies that gestures communicate meaning “through public and intentional actions in reference to objects in the shared visual environment” (Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016, p.2). Subsequently, gestures used in a conversation by a group of interlocutors “become contextual references for the production of subsequent actions” (Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016, p.2). This has profound implications for group dynamics, because gestures are recognized and learned by groups of people or communities that use them, becoming part of the shared contextual information.

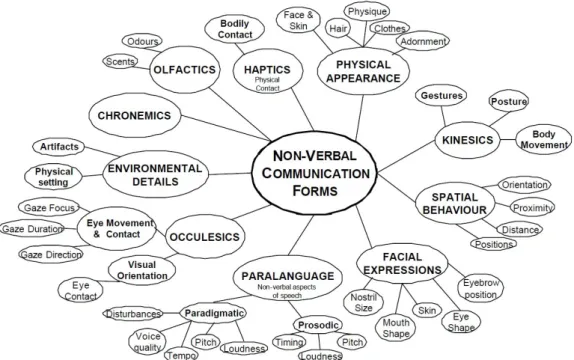

Gestures can take many forms (Fig. 5) that have been repeatedly studied by different authors, making it hard to point out a definitive taxonomy for them. Nonetheless, there are authors that have contributed from the fields of interaction design and game design (Manninen & Kujanpää, 2002; 2003; Manninen, 2003; Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016; Antonijević, 2013) to propose categorizations that bring together contributions from communication literature and anthropology studies. This research will focus on some of these categories for their presence or potential for implementation in multiplayer games, such as proxemics, kinesics, oculesics, and

non-verbal audio.

Proxemics consists of the spatial behavior of an individual and the

communicative use of space. Burgoon & Ruffner (1978) use this concept to refer to interactions that involve the use of personal space, and one’s movement in space. Edward T. Hall explains (Hall et. al., 1968) how different preferences regarding the space between interlocutors can signify different types of relations. In multiplayer games, proxemics relates to the gestures and meaning created by moving one’s avatar in the digital space, and how the avatar’s relative position to objects and other player characters can communicate different things.

Oculesics refers to communication through eye behavior and gaze. Although it is often described as a subcategory of kinesics, it is still considered an important gesture type due to the vast range of meaning that can be conveyed with eye contact and nuanced eye motion. Kujanpää & Manninen (2003) make the distinction between variables like “amount of gaze (e.g., how long people have eye-contact) and quality of gaze (e.g., pupil dilation, blink rate, opening of eyes, etc.)” (Kujanpää & Manninen 2003, p.4). In multiplayer games, players cannot control the eyes of an avatar, but they can control where the avatar faces. The direction where the player is facing and the duration of the “gaze” cannot be attributed to kinesics for the lack of bodily motion, or proxemics for the lack of avatar displacement.

Non-verbal audio can take the form of paralanguage or vocalics, and sounds generated by an individual’s body (Burgoon & Ruffner, 1978). Kujanpää &

Manninen (2003) describes vocalics as non-verbal cues in one’s voice that can either be “linked to speech (e.g., timing, pitch, and loudness)” or “independent from it (e.g., personal voice quality and accent, emotion, disturbances)” (Kujanpää & Manninen 2003, p.4). In multiplayer games, non-verbal audio produced by the character’s avatar occurs in response to the activation of game mechanics, such as the sound of steps when moving, grunting sounds when the character receives damage, or the

characteristic swoosh sound emitted when avatars perform a punch or kick. Non-verbal audio can be even more important than the game mechanics they accompany because they are the only type of gestures that is not limited to shared visual

environments.

Lastly, kinesics offers the widest range of bodily generated gestures, accounting for most of one’s body language. More precisely, it includes all bodily movement and

gestures one can make with the body, except for touching others and moving to different locations (Burgoon & Ruffner, 1978). Some examples are head nods, shrugs, facepalms, or even one’s posture when standing or sitting. Kujanpää & Manninen (2003) explain how kinesic gestures frequently involve hand and arm movement as main transmitters, as a supplement for speech or used independently to point at things.

Figure 6. Examples of gestures from Elder Scrolls Online (Bethesda, 2014)

In digital games, kinesics has been the most prominent form of extralinguistic communication because of its diverse applications, such as allowing players to easily communicate ideas, emotions and give commands through expressive bodily gestures (Kujanpää & Manninen, 2003) that game avatars can enact. An instance of these gestures can be found in the popular fantasy MMO Elder Scrolls Online (Bethesda, 2014), where the players have access to an exhaustive compendium of gestures called “emotes” (Fig. 6) which prompt the avatars to perform pre-designed bodily gestures. These emotes give players the tools to easily communicate ideas, emotions, and even give instructions to other players through their avatar’s expressive bodily gestures (Kujanpää & Manninen, 2003). The inclusion of expressive human-like gestures for avatars enhances the sense of presence and cohabitation during play.

2.12. Pings: canonical examples of collaborative kinesics

in games

The broad range of semiosis offered by kinesics allows MMOs to have the same type of cooperative non-verbal gesture communication generally found in the co-located "couch" multiplayer experience. In the same manner that co-co-located players can strategize by pointing at the screen and planning their actions, digital kinesics offer mechanics that accomplish the same goal, and in some ways, exceeds the limitations of physical bodily gestures. Pointing is a kinesic sign performed by

a specific person, thing, location, event, or idea. However, the individual that

witnesses the pointing gesture can only draw an imaginary line from the finger to the destination, hence, leaving room for error and ambiguity. In contrast, digital games have recognized the need to support verbal communication with kinesic gestures that allow players to mark objects, players, and points in space accurately. This feature is referred to as a "ping” and was originally introduced in the game Rainbow Six Vegas (Ubisoft, 2006). Pings are tagging mechanisms and function similarly to placing pins on a map. For the most part, pings are visual markers that can be placed in the virtual world, and they trigger visual and auditory alerts for the other teammates (Leavitt, Keegan & Clark, 2016). To understand the applications of pings, this research will explore their implementation in the games, Portal 2 (Valve 2011) and Apex Legends (2019).

2.12.1. Portal 2, and its ping tool

Portal 2 (Valve, 2011) is an unconventional game, it is a puzzler-platformer game, but it is played using first-person shooter (FPS) mechanics. The main game mechanic is firing a gun that creates portals which players then use to teleport between them. In the multiplayer mode, two players —blue player and orange player— collaborate by using their respective portals to cooperatively solve spatial puzzles. Adding to the challenge, each player can only create two portals at a given time —one for entering and the other one for exiting— and the multiplayer puzzles require 4 portals to be solved. This particularity of the co-op (cooperative) mode not only promotes communication but makes it crucial for completing any given

challenge. To support such communication between online players, the game presents the “ping tool”, a mechanism that players can use to place pin-like pings on any object or surface (Fig. 7). These pings are colored to match its sender, and they come in three different types differentiated by their icons, these are “look” pings, “timer” pings, “portal request” pings, and the “go here” ping.

Figure 7. Example of Pings in the game Portal 2 (Valve, 2011)

The ping tool is one of the earliest examples of ping systems as a communication mechanism that recreates the affordances of pointing kinesics in digital games. It serves as an example of developers recognizing that the online multiplayer challenges can be very frustrating experiences if players cannot give precise instructions to their

teammates. Moreover, the ping tool was implemented in a simplified way, requiring only one keypress for accessing all ping types. Once summoned, the radial ping menu (Figure X) offers a simple and accessible user experience. Additionally, ping features like the "timer," which allows players to synchronize actions, show how unique game designs require specifically tailored communication methods so that players can rise to the challenge.

2.12.2. Apex Legends, and its ping system

From the moment of its release, Apex Legends (Respawn, 2019) was a

tremendous success in the online FPS genre for its unique mechanics. It used a “battle royale” formula, which consists of having sixty players divided in squads of three, and then dropping them in a huge virtual battlefield. The goal of the game is to be the last squad standing. To add to the challenge, matches have a finite duration as the borders of the map shrink in intervals, meaning that players cannot camp in a specific site, they must keep moving towards the safe locations before the map collapses. Apart from the obvious communicative need to strategize attacks, indicate possible dangers, or communicate about each player’s status, players must help each other to find weapons. At the start of the match, players have no equipment and must

scavenge for any items that can help them stay alive, and with 57 enemies and only two allies, teams need to make sure all collaborators are well equipped to stand a chance of winning.

Figure 8. Pings System as seen in Apex Legends (Respawn, 2019)

To fulfill the game's communicative needs, the developer Respawn created one of the most innovative online communication systems since the ping tool. Apex

Legends features a communicative mechanism called the ping system (Fig. 8). While it shares a lot with the one seen in Portal 2 (Valve, 2011) —like the radial menu, and the tags that can be placed to point to objects and spaces— it offers a far more accurate and intelligent system while maintaining a straightforward and elegant user interface. In a similar manner to Portal 2, Apex Legends includes auditory in its pings

specific to each playable character, and they speak in the language in which the game is set.

Lahti (2019) praises the game by saying that it is the first online FPS game that made voice-chat optional, which is an excellent compliment for a genre that until now relies almost entirely on voice-based interactions. The game shines for the vast amount of messages that can be created with its pings, some of them are (1) pinging a location the map, (2) marking a location to say you are headed there, (3) announcing you are keeping watch on a location, (4)mark the location of specific items, (5) calling "dibs" on items, (6) agree or disagree to pings, (7 reply to a ping saying "I cannot do that", (8) announce that you are joining a specific player, (9) You can retract or cancel a ping, (10) mark a location where enemies are present, (11) mark a location where enemies were previously seen, (12) announce where you are

attacking, (13) announce that you are defending a location, (14) asking for help, (15) announcing you are going to help an injured player, (16) saying "thank you" to teammates, and others.

It can be easy to assume that having so many ping options would encumber the user interface, making it chaotic to find a specific ping among so many options. However, the designers found an intelligent solution to this problem, to make the pings context-sensitive, meaning that once the ping radial menu is summoned, only the relevant options will appear. The options in the "ping radial menu" depend on what the player is currently pointing at, for example, if the player is pointing at an enemy, the ping to mark the location of the enemy will be available. However, if there is no enemy, the ping menu will not include these options. The same thing happens when a player gives instructions to the rest of the team; the option to react to it with a subsequent ping will only be available for a short time (Fig. 9), as it would soon become irrelevant to have the option to react.

As it was mentioned before, NVC systems in online games can go beyond the limitations of physical bodily gestures by providing more accurate pointing

mechanics that avoid the ambiguity in physical kinesics. Apex Legends achieves this with its extensive list of ping gestures, and a context-sensitive interface. Additionally, the game also changed the paradigm of NVC as a supplement to voice-based

interactions. In this game, gestures prove to be the protagonists, and the pre-recorded voices exist to supplement the NVC, to spray some of the character's personality into each ping.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Research through design

This work follows a “research through design” (RtD) methodology driven by how the unique epistemological characteristics of “inquiry and action” (Zimmerman & Evenson, 2007) intrinsic to the design discipline can produce knowledge “in and through design” rather than into or “for design” (Redström, 2017). Meaning that the instead of using design as the subject, this research uses design for the development of knowledge (Zimmerman & Evenson, 2007), and in the process, creating design artifacts that are “knowledge producers both for those that encounter them and those that design them” (Bardzell et. al., 2015, p.1). Any RtD artifact produced in this research will then reflect “a specific framing of the problem, and situates itself in a constellation of other research artifacts that take on similar framings or use radically different framings to address the same problem” (Zimmerman & Evenson, 2007, p.6).

The participatory nature of this research means that any artifacts created will be co-designed with the players and for the players, as they are recognized as the experts on the subject of playing and living within digital game worlds. To leverage co-design and knowledge making, this research will draw parallel lines (Reström, 2017) between the moments of participatory co-creation and the moments of analysis to “create a kind of oscillation between the two, moving back and forth between them, often associated with methodological notions about taking turns between action and reflection” (Reström, 2017, p.28). Therefore, the presented research uses a

methodological approach that would fall into Krogh, Markussen, & Bang’s “serial” (2015) typology of RtD. Particularly, because the co-design workshops and the insights acquired from their analysis, would determine the next steps that would be taken and the direction the research would take (Krogh, Markussen, & Bang, 2015, p.9).

By following the RtD methodology, this research seeks to bring together knowledge from psychology, anthropology, semiotics, and interaction design to contribute to digital social play, and to draw a clear line between interaction methods and the problems with inclusion, cohabitation and cooperation in online multiplayer games.

4. METHODS

4.1. The impact of COVID19 on the methods

The following methods were used in the design process of this research to address the need to analyze the context of online multiplayer games, to inquire on the player’s use of existing communication systems, to understand how players appropriate game mechanics for communicative purposes, and to co-design non-verbal player-to-player interactions using the insights and the proposed methodology that was created

through the research. However, it is important to mention that the 2020 outbreak of the virus COVID19 had direct impact on the methods This means that this research had to take creative liberties to make variations of existing methods and even

reshaping them in different ways. Every method was modified to work remotely and any physical components that had to be delivered between participants and

researchers were isolated for seven days before being opened. All of this was made to minimize any health risks for the research participants and to uphold the social

distancing precautions indicated by the government and healthcare officials.

4.2. Digital observation methods

Ethnographic observation methods were used throughout this whole research because it proved to be invaluable to understanding how online players live their lives in digital game worlds. Different applications of this method revealed vital insights that even players themselves did not recognize due to their involvement in games.

4.2.1. Fly-on-the-wall

An iteration of the “fly-on-the-wall” method (Hanington & Martin, 2012) was used in the initial stages of the research, due to the need to see and understand the culture that players build in various game worlds. This method was a great fit, since it intentionally keeps the researcher from coming in direct contact with the activity that is being observed, hence, “Fly-on-the-wall attempts to minimize potential bias or behavioral influences that might result from engagement with users” (Hanington & Martin, 2012, p.90). The fly-on-the-wall method was used through a digital streaming platform called Twitch, where players willingly share their gameplay letting anyone watch the game from their point of view in real time. Twitch streamers have recurrent watchers and playing with them watching is part of their “everyday life” meaning that having the researcher watching anonymously did not taint the purpose of this method. The digital nature of this method also allowed for descriptive observation (Blomberg et. al., 1993) where the prescriptive and descriptive behavior can be compared.

4.2.2. Holistic observation

This method is described by Blomberg et. al. (1993, p.125) as an observation of the behavior of individuals in relation to the context or everyday life (Fig. 10). This method was used for the workshops that happened inside games, where the behavior between players was observed within the specific context afforded by the game mechanics. The digital observation through streaming helped make this more detailed as the observation happened directly through the eyes of the player.

Figure 10. Illustration of holistic observation from Blomberg et. al. (1993).

4.3. Secondary Research

IDEO (2015) proposed secondary research as a human-centered method to fill the gaps in knowledge the researchers might have, or as a tool to find all the information needed to properly understand the context of the participants. For this research online research was necessary to understand the existing platforms for online games, and to find usage data of them in form of official statistics, journalistic publications, and pre-existing footage of game sessions. This method was also used to understand the history behind the games themselves, the mechanics, and terminology used in the games. This was important as it built common ground to facilitate interviews.

4.4. Immersive interviews

The classic structured and unstructured interviews had to be replaced with what this research is calling immersive interviews. This was a new method that had to be used to be coherent with the health precautions described at the beginning of this section. This research tried to turn the social distancing problem into an opportunity. Since enforcing social distancing required interviews to be carried out remotely, instead of using phone calls or video calls the interviews were held through the games, while the player is still “in-character” and immersed into the game world. This method was first performed by Calleja (2011) who mentioned:

“Each interview took place within the virtual environment of the game about which the participant was being interviewed, in order to further stimulate their memory and to bring their relationship to the game world to the fore”

(Calleja, 2011, p.36).

Even though Calleja (2011) did not name this method or described any instructions of how it should be carried out, this research tried to replicate his method. Therefore, semi-structured interviews were carried out through the game to keep the recent gameplay experience fresh by staying in the game environment.

4.5. Co-design Workshops

Participatory design holds the use of generative tools as one of its most used methods for designing with users and not just for them (Sanders, 2012). This research focuses on the inclusion of players and regards them as experts in the games they play. As such, they were included in the design process through planned activities where the designer acted as facilitator and offered the participants tools and

techniques to be used in generative activities or co-design workshops. Liz Sanders

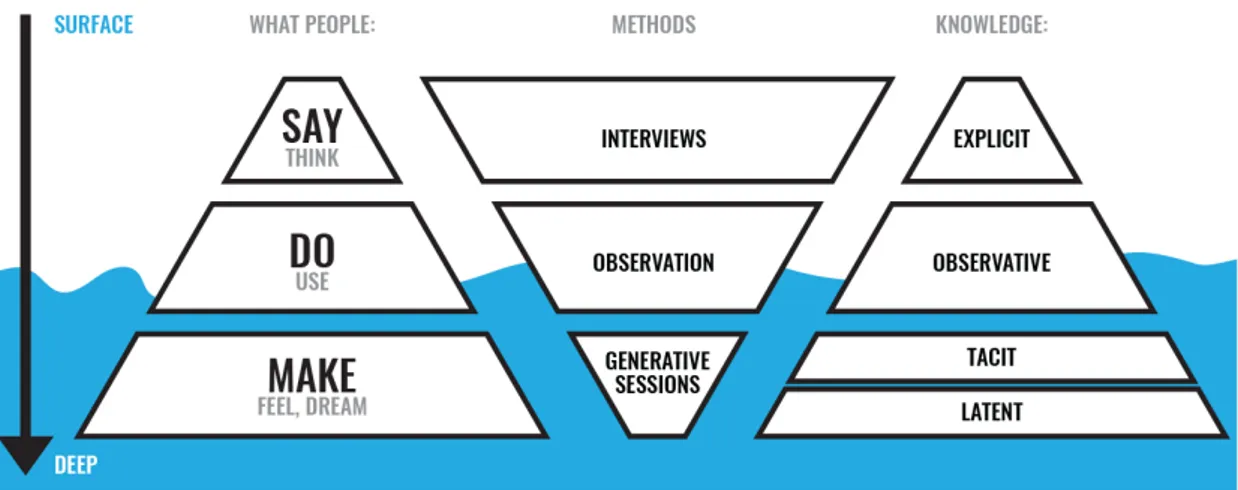

(2012) defines tools and techniques saying “By tool we refer to a physical thing that is used as a means to one end. By technique we refer to the way in which this tool is employed” (Sanders, 2012, p.65). The methods used for the workshops were based on Sanders (2012), who proposes planning activities that engage participants in “say”, “do”, and “make” techniques. Each type of technique resonates with different levels of knowledge, with “say” being with the explicit level, “do” connecting to the

observative level, and “make” reaching to the deepest levels of tacit and latent