“Helping our consumers

buy less,

but choose well”

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ETCS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHORS: Ella Dahlman, Susanne Merkler

TUTOR:MaxMikael Wilde Björling

GOTHENBURG/JÖNKÖPING December 2020

An explorative study on how sustainable fashion brands

market themselves

i

Acknowledgements

We would like to give a huge thanks to everyone who has supported us with insightful knowledge as well as motivation over the past months. We are extremely grateful! First and foremost, we would like to thank our tutor MaxMikael Wilde Björling for the guidance, knowledge and support he has given us throughout this entire process.

Secondly, a sincere thank you to Bert at MUD Jeans, Heather and Itee at Loop, Loris and Jonas at Briga, Lisa McNeill from the University of Otago, Anna at Aiayu, Elisabeth at Jumperfabriken and Kevin from Nudie Jeans for investing their time and efforts through participating in our interviews.

We would also like to end with thanking each other and ourselves for the time we spent together, and the support and commitment we have shown throughout the entirety of this autumn.

We are extremely grateful for this experience and will gladly sign this thesis with pride. #stressodepressogangout

_______________________ _______________________ Ella Dahlman Susanne Merkler

ii

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: “Helping our consumers buy less, but choose well”: An explorative study on how sustainable fashion brands market themselves

Authors: Ella Dahlman & Susanne Merkler

Tutor: MaxMikael Wilde Björling

Date: 2020-12-16

Keywords: Sustainable fashion, Sustainable fashion marketing, Sustainable fashion consumers

Abstract

Background: The fashion industry in its current state operates under conditions that are

considered unsustainable. In order to appeal to the growing environmental and ethical concern of consumers, fashion brands have started to employ strategies of green marketing, often focusing on clothes marketed as consisting of sustainable or eco-friendly fabrics. Meanwhile, fully sustainable fashion brands have emerged, where sustainability values are carried throughout all organisational practices.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore how sustainable fashion brands market

themselves and which types of consumers the current strategies attract. It aims to lay out an initial foundation for further research carried out in the future.

Method: A multi-case study of six sustainable fashion brands and an expert on sustainable

fashion consumption was conducted under an interpretivist paradigm. A thematic analysis of the data received through semi-structured interviews provided an initial in-depth understanding of the phenomenon under consideration.

Conclusion: Sustainable fashion brands emphasized the importance of a holistic approach to

conducting business under sustainability values. This understanding expressed itself in direct implications for design and longevity of fashion garments and a coherent approach to communication and retailing of products utilizing storytelling and a criteria-based choice of retailers. Main consumer groups identified were sustainability-minded consumers, as well as design-interested ones in some cases.

iii

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 4 1.3 Purpose ... 5 1.4 Research Questions ... 6 1.5 Delimitation ... 62.

Methodology and Methods ... 7

2.1 Methodology ... 7

2.1.1 Research Philosophy and Paradigm ... 7

2.1.2 Research Approach ... 8

2.1.3 Research Design ... 8

2.2 Method ... 9

2.2.1 Sampling Method ... 9

2.2.2 Data Collection ... 9

Table 1. Overview of interviews……….10

2.2.3 Data Analysis ... 11

2.2.4 Ethical Considerations ... 12

3.

Frame of Reference ... 14

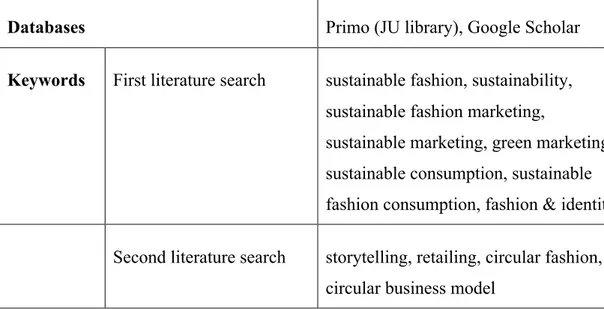

Table 2. Search parameters for literature review………..14

3.1 Sustainability ... 15

3.2 Marketing ... 16

3.2.1 Fast Fashion and Fashion Marketing ... 16

3.2.2 Green / Sustainable Marketing ... 17

3.2.3 Sustainable Fashion Marketing ... 18

3.3 Communication and Distribution ... 20

3.3.1 Storytelling ... 21

3.3.2 Retailing ... 22

3.4 Consumer Behaviour ... 23

3.4.1 Fashion and Identity ... 23

3.4.2 Sustainable Consumption and Consumer Attitudes Towards Sustainable Fashion ... 24

4.

Empirical Findings and Analysis ... 28

4.1 Perceived Sustainability Issues within the Fashion Industry ... 28

4.2 Marketing Strategies ... 31

4.2.1 A Holistically Designed Sustainable Marketing Approach ... 31

4.2.2 Times Design and High-Quality Garments ... 34

4.2.3 Circularity, Wear & Repair ... 37

4.2.4 Storytelling and Transparency ... 40

4.2.5 Retailing ... 44

4.3 Consumers ... 46

5.

Conclusion ... 50

iv 6.1 Implications ... 52 6.2 Limitations ... 52 6.3 Future Research ... 53

7.

Reference list ... 55

8.

Appendix ... 64

8.1.1 Appendix 1 – Interview Questions for Brand Representatives ... 64

8.1.2 Appendix 2 – Interview Questions for Sustainable Fashion Consumption Expert ... 65

1

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The first chapter of this study will introduce the reader to the current state of the fashion industry and the resulting shift towards a more sustainable underlying paradigm. Then, the research problem addressed in the course of this study are presented.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

“There is no beauty in the finest cloth if it makes hunger and unhappiness.”

Mahatma Gandhi

The fashion industry, i.e. the industry concerned with the production and sale of clothes, has become a “multibillion-dollar global enterprise” (Steele & Major, 2019) profiting from people’s desire for self-expression. The fashion industry itself as well as the trends it aims to deliver to its consumers are continuously changing.

The predominant throwaway-and-replace mentality that the fashion industry thrives on however comes at a great cost. The current state of the industry does not meet the conditions needed in order to pursue global sustainable development and sustainability issues related to the fashion industry have become a well-debated topic in today’s society. According to WWF Switzerland (2017), the fashion industry is highly resource-intensive and its environmental and social impacts are “far from sustainable” (p. 3).

As of 2017, growing consumer demand for new items resulting from a growing middle class had led to a 50% increase in the clothes produced in the previous 15 years (Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2017) which in turn led to a growing need for resources required for clothes production. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (as cited in UN News, 2019) reported that the fashion industry annually uses around 93 billion cubic meters of water - an amount which could meet the water needs of 5 million people. As one of the world’s heaviest polluting industries, the production and consumption of fashion has immense environmental impacts.

2

Through its production processes and extensive use of colours and chemicals in the fabric dyeing process, the fashion industry annually causes around 15-20% of global wastewater (Kant, 2012; United Nations Environment Programme, 2018). The extensive use of microfibre that is shed into the ocean equals an annual spill of 3 million barrels of oil (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development as cited in UN News, 2019). Microplastics are considered to be one of the most prevalent risks for marine biodiversity (Gall & Thompson, 2015) and fragments of microplastics have previously been detected in fish consumed by the human population, thus imposing a potential health risk on our own species (Karami et al., 2017).

The fashion industry also makes up for around 10% of total global greenhouse gas emissions (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2018), consuming more energy than maritime shipping and international flights in total (International Energy Agency, 2016 as cited in Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2017). The Ellen McArthur Foundation’s report A New Textiles Economy: redesigning fashion’s future (2017) warns that “if the industry continues on its current path, by 2050, it could use more than 26% of the carbon budget associated with a 2°C pathway” (p. 21), the maximum global temperature increase agreed on in the Paris Agreement (United Nations, 2015). Clothing waste has become a serious problem. According to a report by McKinsey & Company (2016), half of the clothing items falling under the fast fashion category are disposed of within a year after their purchase. WWF Switzerland (2017) reported that only 20% of discarded clothes were recycled, with around 80% winding up in landfills or being burned.

Social impacts of industry practices range from the individual to societal level. The fashion industry has positively contributed to economic growth, employing over 300 million people worldwide (Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2017). The outsourcing of garment production in attempt to lower production costs has led to the creation of work opportunities for millions of individuals especially in producing countries, such as China, India and Bangladesh. According to the International Labour Organization’s Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (2016), developing countries in Asia and the Pacific have become the most important garment exporters. However, working conditions within the fashion industry, and at garment factories in particular, often do not comply with

3

internationally recognized labour standards such as those introduced by the International Labour Organization (Ross & Morgan, 2015) thereby involving serious risk to individual employees’ safety and health.

The Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013 brought the hazardous working conditions of fashion supply chains to light. As a result, it has put immense pressure on fashion enterprises to enhance transparency and ensure the improvement of working conditions for those employed in the bottom end of the fashion industry (Rushe & Safi, 2018). In recent years, consumers have become increasingly aware of the impacts their overall purchasing behaviour has on people and the planet. According to Google Trends (2020) the global interest for ‘sustainable fashion’ in particular has shown an increase over the last 5 years, thus indicating that consumers have become increasingly concerned with the topic.

In order to appeal to the growing environmental concern of consumers, fashion retailers of all sizes have included clothing items consisting (or partly consisting) of materials marketed as sustainable fabrics into their market offering. Organic cotton, Hemp, Lyocell, Rayon and Viscose as well as recycled materials are just some examples of the popular fabrics the ‘sustainable options’ are made of and are more frequently seen on the market (see for example Zara and H&M’s recent product offerings). In addition to the choice of better materials, transparency across fashion supply chains has immensely increased. Many companies are nowadays providing the public with annual sustainability reports, presenting their respective efforts and strategies in terms of environmental and social responsibility (see for example H&M Group, 2018; Uniqlo, 2019; Inditex, 2019). Despite these developments, clothing made from more environmentally friendly fabric alternatives only account for a fraction of the globally available garments. Items consisting of materials such as polyester and other microfibres remain part of the market offerings, thus continuing to impose environmental risks (Grenthe et al., 2019). However, fully sustainable fashion brands have emerged and devoted themselves to sustainable business practices entirely. By ensuring that all of their operations comply with the individually compiled set of sustainability values they stand for (Bismar, n.d.).

4

With both contemporary as well as fully sustainable fashion retailers offering similar products, the market for sustainable clothing has become highly competitive. Accordingly, the need for marketers in sustainable fashion enterprises to develop effective marketing strategies in order to win over eco-conscious consumers has significantly increased.

1.2 Problem Discussion

As part of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, Responsible

Consumption and Production has been identified as one of the key areas requiring

improvement (United Nations, n.d. b). With the fashion industry being considered one of the most polluting industries in the world (UN News, 2019), the consumption of fashion in particular needs to shift towards a focus on more sustainable clothing choices.

Over the years, the general awareness of social and environmental concerns linked to individual consumption behaviour has increased (Maloney et al., 2014). While generally, pro-environmental attitudes have shown to have a strong influence on pro-environmental behaviour (Grob, 1995), when it comes to consumption, actions often do not align with values. Although consumers with a higher environmental knowledge show a higher willingness to pay more for sustainable clothing (Lee, 2011), research identifies a gap between consumers’ sustainability values and their final purchasing behaviour (Boulstridge & Carrigan, 2000; Carrington et al., 2010; Johnstone & Tan, 2015). The attitude-behaviour gaps cause remains a popular research topic, with common explanations ranging from errors in the studies conducted, to the cognitive explanations on the side of the consumer (Davies et al, 2011; Shaw et al., 2015). A common academic understanding of the issue is thus yet to be found. Encouraging consumers to align consumption behaviour with their sustainability values is, however, of vital importance in order to drive global sustainable development forward.

As the amount of market offerings of clothes promoted as ‘sustainable’ increases, making the most sustainable choice can prove a hard task for consumers to manage. Although popular fashion enterprises claim to follow sustainable purposes, many of the activities conducted within the organization often do not align with those claims, thus entailing the risk of organizational greenwashing (Dahl, 2020).

5

Ensuring a fair and sustainable production of clothes often leads to higher prices of the final items which can complicate sustainable fashion companies’ efforts to gain market share. Although consumers’ willingness to pay premium price for sustainable products, especially in the Western world, is increasing (Moisander & Personen, 2002; Dangelico & Vocalelli, 2017), many consumers consider price premiums only as acceptable up to a certain point where the incurred ethical benefits exceed the financial sacrifice (Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008). Indeed, price sensitivity has been identified as one of the factors having a moderating effect on willingness to engage in sustainable fashion consumption behaviour (Bray et al., 2011; McNeill and Moore, 2015).

Sustainable fashion brands thereby need to be able to justify the incurred price premium in the face of competition in order to increase the perceived value of the proposed ethical and sustainable benefits. Moreover, in order to attract fashionable consumers alike, maintaining a ‘fashionable’ image alongside the perceived sustainability advance remains a hard task to manage. The marketing approaches sustainable fashion brands use in order to gain consumer trust therefore play a major role in promoting global sustainable development. The availability of current literature on the marketing of sustainable fashion brands is very limited. A basic understanding of these approaches is, however, of vital importance in order for further research to develop suggestions for improvement to achieve the global sustainability agenda.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to develop a basic understanding of how sustainable fashion brands market themselves in the fashion market. In a more specific manner, the authors aim to investigate the tools and methods sustainable fashion brands use and ultimately which consumers the brands currently attract. As available literature on the topic is limited, this study will be of exploratory nature. It thereby aims to provide an initial foundation of knowledge on the issue that in later research can be used to develop ideas for improvement of the discovered marketing approaches in order to contribute to a more sustainable future.

As previously mentioned, the fashion industry employs over 300 million people world-wide (Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2017), contributing to economic, as well as social and environmental impacts. With a peak growth rate of 6.2 percent predicted in 2020 (Statista,

6

2019), the fashion industry provides an important subject to be further researched in terms of sustainability due to the formerly established economic, social and environmental impacts.

1.4 Research Questions

RQ1: How do sustainable fashion brands market themselves? RQ2: Which consumers are these brands currently attracting?

1.5 Delimitation

The fashion industry is an extremely large and complex system consisting of many different branches. Sustainable fashion has taken on different forms ranging from second hand and vintage clothing, to upcycled and circular approaches as well as textiles produced under sustainable conditions. Many popular fashion brands have started offering clothes marketed “sustainable” or “eco-friendly”. Due to time and resource constraints, the authors of this study have chosen to focus on what were perceived as fully sustainable fashion brands in order to explore how these brands market themselves and thereby stand out in the market. The brands at hand thus shared the same goal of having an aim to improve overall organisational practices within the industry in terms of sustainability. Given the limited time to conduct the presented study, research on the brands’ consumers was conducted based on brand perspective.

In order to allow for a broader perspective and find non-country specific similarities, the study was not limited to any specific geographical locations or branches within the industry.

7

2. Methodology and Methods

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The first section of this chapter presents the methodology, including the research paradigm, research approach and research design under which the presented study was conducted. The following section provides a description of the methods with regards to the sampling, collection and analysis of the data as well as a concluding section depicting the ethical considerations.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Methodology

2.1.1 Research Philosophy and Paradigm

As the researcher’s “set or system of beliefs” (Waite & Hawker, 2009, as cited in Collis & Hussey, 2014, p. 43), the research philosophy under which a scientific study is conducted lays the foundation for the specific methods used in conducting the study. In contemporary research, scientific studies can follow a positivist or interpretivist research paradigm (Collis & Hussey, 2014). While in positivism, reality is considered to be singular, objective and measurable, interpretivism considers reality dependent on the observer’s subjective values and perceptions, thus suggesting that there is no one reality to be discovered (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Although there are internationally recognized definitions of sustainability or sustainable development, individual and organizational perceptions and understandings of the concept can differ widely. The brands interviewed presented similar, yet not identical definitions of sustainability that preceded the marketing approaches they utilized. Considering the subjectivity of the issue at hand, the here presented study was conducted under an interpretivist paradigm in order to allow for an unconfined process of discovering and comparing similar themes arising from the empirical data collected. Given the underexplored character of the phenomenon of sustainable fashion brands’ marketing strategies, the amount of literature on the topic is limited to non-existent. Following principles of interpretivism, the analysis and conclusions presented in the course of this study therefore heavily relied on the authors’ subjective understanding of the studied phenomenon (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

8 2.1.2 Research Approach

In a given study, the research approach defines the way in which data is linked to relevant theory, with two prominent approaches to be chosen from: the inductive or deductive approach (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The choice of research approach is often determined by whether a given study is of quantitative or qualitative nature (Saunders et al., 2019). Quantitative research often utilizes a deductive research approach in order to test a given theory through collected empirical data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Qualitative research, however, mostly follows an inductive approach where theory is derived from data collected during the study of a given phenomenon (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

The lack of scientifically relevant research on the phenomenon of sustainable fashion marketing prevented the definition of hypotheses to be tested and instead required an experience-based approach where themes and patterns were discovered based on the empirical findings made. The presented study thereby followed an inductive research approach moving from the collection of empirical data to the analysis of the general themes identified and analysed using relevant theories.

2.1.3 Research Design

According to Collis and Hussey (2014), inductive research following an interpretivist paradigm often uses qualitative data as a basis for the given study. For phenomena that lack sufficient academic literature, a qualitative research design allows for relationships between arising themes and meanings in the empirical data to be discovered. With the purpose of this study being to develop an initial foundation of understanding of the marketing of sustainable fashion brands, the study was designed as an exploratory study which according to Collis and Hussey (2014) allows for more flexibility during the research where available literature on the phenomenon is limited. Yin (2018) proposes that a case study provides an empirical method that allows in-depth studies of a phenomenon within its given context, with multi-case approaches allowing for a better understanding of underexplored phenomena.

The present study employed a multi-case study method in order to build a stronger foundation of knowledge based on the comparison of differences and similarities between different sustainable fashion brands’ approaches to marketing.

9 2.2 Method

2.2.1 Sampling Method

Considering the growing population of sustainable or ethical fashion brands, conducting research based on all such brands globally would be too resource and time-intensive under the given time constraints of this study. Therefore, a sample of sustainable fashion brands was chosen in order to provide as a base of the research to be conducted. According to Saunders et al. (2019), there are two sampling methods under which participants of the study can be chosen: non-probability sampling and probability sampling.

In this study, in order to be considered as part of the sample, participants had to fulfil predetermined criteria. The sample examined in the course of this study was therefore chosen based on a non-probability method.

Although the study was not continent nor fashion branch specific, the sample included representatives from six sustainable fashion brands within Europe and Asia: Aiayu, Briga, Jumperfabriken, Nudie Jeans, MUD Jeans and Loop Swim. To be considered, sustainable fashion brands needed to fulfil the requirement of openly communicating an overall or holistic approach to sustainability as a guiding principle in contrast to the contemporary fashion industry. One of the brands was simultaneously chosen ad-hoc given one of the author’s prior connections to the company.

Additionally, in order to allow for a broader perspective incorporating the side of the consumers of sustainable fashion, the sample was complemented by Lisa McNeill, Associate Professor in Marketing at the University of Otago, New Zealand. The representative of the expert voice for sustainable consumers was chosen based on her previous extensive research on sustainable fashion consumption behaviour which in part also provided valuable knowledge in the Frame of Reference presented in a later section.

2.2.2 Data Collection

The present study relied on the collection of primary data which according to Collis and Hussey (2014) refers to a type of data collected from a first-hand source.

The data was collected through six semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted with representatives of the chosen brands as well as Ms McNeill. A semi-structured approach

10

was chosen in order to allow for flexibility and opportunity to adapt to the arising themes during the interviews. Due to the geographical distance to some of the participants’ offices, as well as the current Covid-19 pandemic preventing physical meetings, all interviews were conducted via the platform Zoom which allowed for a virtual face-to-face meeting. The collection of data from one of the brands was conducted through the participation in a webinar offered by the brands’ founder especially for research occasions.

Table 1 depicts an overview of the brands and the fashion branch they specialized in, their

representatives and the length of the interviews/seminar.

Brand Name Branch Representative(s) Platform Date of Interview

Length of Interview

MUD Jeans Jeans Bert Zoom

Webinar

2020-11-02 43 min

Loop Swim Swimwear Heather & Itee Zoom Interview

2020-11-03 34 min

Jumperfabriken Knitwear Elisabeth Zoom Interview

2020-11-03 29 min

Briga Socks Jonas & Loris Zoom Interview

2020-11-04 33 min

n/a n/a Lisa McNeill Zoom

Interview

2020-11-11 33 min

Aiayu Knitwear Anna Zoom

Interview

2020-11-12 29 min

Nudie Jeans Jeans Kevin Zoom

Interview

2020-11-12 23 min

11

Semi-structured interviews

The interviews were designed to yield as much valuable information as possible with regards to the research questions. Given the explorative outlook on the study of general marketing approach of sustainable fashion brands, the questions were developed to cover a broad range of topics including but not limited to a brand and value presentation, the perceived issues within the industry, differentiation aspects and consumers. The exact composition of the interview questions differed between those asked to representatives of the brands and those asked to Lisa McNeill due to the different points of view they represented.

For the brand representatives, interview questions were designed as open-end questions to allow for an organic response and ensure that respondents provided in-depth information on what they deemed important. Where deemed necessary to enable a better understanding, the authors utilized follow-up questions to dig deeper into the matter the interviewees brought up.

The interview with Lisa McNeill followed a different approach. Some questions followed an open-ended design in order to build an initial understanding of her individual perception on the topic. Others were slightly more structured as they aimed to receive constructive, expert feedback on the marketing methods the brands presented in terms of their relevance for bridging the attitude-behaviour gap and attracting sustainable consumers.

In the seminar with MUD Jeans, only those questions that had not recently been covered by other participants were asked to complement the received information.

A collection of the interview questions asked is provided in the appendix.

2.2.3 Data Analysis

The collected data was analysed using a thematic analysis in order to identify and interpret emerging themes within and across the collected data (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and thus allow for the determination of key marketing aspects the interviewees presented. As proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006), a thematic analysis consists of six steps: data

12

familiarization, initial coding, theme search, theme review, theme definition and naming, and producing of the report.

The analysis of the empirical data started during the data collection process as notes were taken on the mentioned topics and aspects that could prove of significant importance later on. Throughout the process, special attention was also paid to themes that had previously occurred in other interviews. After transcribing the interviews (step 1), arising topics within and across the written transcripts were colour-coded (step 2) according to their relation to each other. This process presented the initial search for recurring themes (step 3). To provide a better overview of the themes identified, quotes relating to the different topics were collected in a separate document where initial names for the themes were selected as headings. The themes were thereafter redefined and named (step 4 and 5) according to their most striking characteristics. Step 6 - producing the report (Braun and Clarke, 2006) is presented in the empirical findings and analysis section of this report where relevant quotes were chosen to represent the identified themes.

2.2.4 Ethical Considerations

Research of a given phenomenon often involves external parties other than the researches especially during the data collection process. Considering ethics is therefore of high concern in order for the research to be reliable (Saunders et al., 2019). In order to comply to ethical standards, transparency provided as a guiding principle throughout the entire process from the start of the collection of empirical data.

Prior to the start of the interviews, the interviewees were introduced to the subject of the study in order to explain what the data they provided was going to be used for. The interviewed participants were also asked for their consent to the interview being recorded. The researchers also extended the possibility for anonymity which could be favoured in order to conceal any information that could be affiliated with the participants company or name (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Furthermore, it was previously communicated that the thesis will be published on the DIVA-portal after the submission. During the finalising stages of the thesis, the final consent for use of personal and brand names was asked through an email sent to the participants. Although the researchers are sustainability students giving potential to bias

13

in terms of sustainability values, an impartial view of the fashion industry was adapted to the study in order to ensure ethical viability throughout all sections of the thesis. The research was in no way financed by external parties, thus ensuring that the research was carried out for an educational purpose only.

14

3. Frame of Reference

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The following section reviews the available academic literature on the topics of sustainability and its relevance for fashion, sustainable fashion consumption as well as sustainable fashion marketing.

______________________________________________________________________

In order to build a relevant Frame of Reference for the analysis of the later presented empirical data, a systematic review of the available literature on the studied phenomenon was conducted. The search for relevant literature was carried out in two stages. Stage one occurred prior to the start of the data collection process in order for the authors to familiarize themselves with the topic and identify a research gap. During the course of the study, themes that had not yet received adequate attention in the literature review arose, thus calling for the search of further literature to complement the initial review. The flexibility and adaptability of the inductive and interpretive approach to this study proved beneficial in the course of this development.

The aim was to focus on fairly recent (less than 10 years) and peer-reviewed publications. Especially the topics of fashion and identity, however, were deeply rooted in findings made prior to this time whereby the intended time frame could not hold on all occasions.

Databases Primo (JU library), Google Scholar

Keywords First literature search sustainable fashion, sustainability, sustainable fashion marketing,

sustainable marketing, green marketing, sustainable consumption, sustainable fashion consumption, fashion & identity Second literature search storytelling, retailing, circular fashion,

circular business model

15 3.1 Sustainability

Throughout history, human activity and economic activity in particular has followed an accelerating trend. Along with it, it has created and intensified a variety of issues, including but not limited to the climate crisis, the loss of biodiversity and environmental degradation, as well as socioeconomic crises ranging from the uneven distribution of wealth followed by increasing inequalities (Steffen et al., 2015).

Sustainable development aims to mitigate the adverse effects of human activity in that it allows human societies to thrive whilst maintaining a healthy planet and thus a sound foundation for human life. As defined by the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987), sustainable development refers to “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.

Over the years, researchers have developed a variety of frameworks and models in order to visualise and clarify the environmental limits to collective human behaviour. Kate Raworth’s (2017) concept of Doughnut Economics combines the Planetary Boundaries proposed by Rockström et al. (2009) as the outer, ecological boundary with the social aspects of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as the inner, social boundary. It thereby depicts a “safe operating space for humanity” (Raworth, 2017) through both the minimum basic needs needed to be fulfilled and the maximum environmental damage in terms of, for example, resource depletion and emissions, to be done.

In the pursuit of providing an attainable foundation for sustainable development, the United Nations’ member states agreed on 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 (United Nations, n.d. a). As part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the SDGs were designed to guide global action to “end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere” (United Nations, n.d. a). Individuals, organisations and private and public actors likewise are urged to adopt sustainable practices in order to enhance safety and quality of life globally while minimising adverse environmental effects.

16

The need for sustainable development has given rise to the development of business models recognizing the importance of considering long-term consequences of short-term (economic) behaviour and internalizes the consideration of not only economic, but also environmental as well as social aspects as depicted in Elkington’s (1994) concept of The

Triple Bottom Line.

3.2 Marketing

3.2.1 Fast Fashion and Fashion Marketing

Barnes (2013) claims that the “definition [of fashion marketing] as a concept has not been explored widely” (p. 183) yet suggests it to be a specified use of contemporary marketing methods. Kotler and Armstrong (2017) define marketing as “the process by which companies create value for customers and build strong customer relationships in order to capture value from customers in return” (p. 29), thus laying a strong emphasis on the satisfaction of consumer needs, in fashion and other sectors likewise. The fashion industry incorporates different sectors and markets ranging from slow to fast fashion, as well as different price ranges: a diversity that needs to be taken into account when discussing fashion marketing.

The contemporary fashion market is characterized by a high level of competition between brands leading to suppliers’ ability to respond to market cues in a short time increasing in importance (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). Indeed, within the fashion industry, a constant change in consumer lifestyles has been identified, resulting in constant “demands for newness” (Barnes & Lea-Greenwood, 2006, p. 260) fashion brands need to address. As defined by Barnes (2013), fashion refers to “something being with short-term popularity” (p. 187) indicating the short life expectancy for fashion products. The term ‘fast fashion’ in the clothing context was first coined by the New York Times in the 1990s as a means of describing Zara’s mission to shorten the time between clothing item design and market introduction to 15 days (Idacave, 2016). By delivering products to the market in a reduced amount of time (Kim et al., 2013), the fast fashion concept allows consumers to constantly reinvent themselves, their wardrobe and the identity they wish to portray to the outside through their clothing (Crane, 2012). The fast fashion concept has thus developed as a business model in response to predominant consumer needs to newness

17

focusing on short lead times. According to Bick et al. (2018), it “thrives on the idea of more for less”, indicating that mass consumption has become a central aspect in the market with fashion items not intended to be worn as long as they last, but rather until they run ‘out of fashion’. In order to be able to fulfil the need for newness in shorter time-periods, the amount of fashion seasons has increased from the former Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter pattern to incorporate additional mid-seasons (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). The amount of collections introduced into the market each year further underpins the quick rate of obsolescence of fashion garments.

The world is constantly developing, with one main area of growth laying within technology. The growth of technology, including the omnipresence of social media has contributed to a large improvement in consumers’ access to information. In recent years, consumers have become increasingly aware of sustainability matters (Carrington et al., 2010; Bray et al., 2011; Maloney et al., 2014) leading to suppliers’ need to integrate such expectations into their respective operations (Nidumolu, 2015).

Therefore, fashion brands have started to introduce values of environmentalism, ethics and sustainability as a whole into their business models and marketing strategies to varying degrees.

3.2.2 Green / Sustainable Marketing

Green, or sustainable marketing research has produced a variety of definitions of the concept over the years (Dangelico & Vocalelli, 2017). The first definition of marketing that “integrat[es] environmental sustainability into marketing” (Dangelico & Vocalelli, 2017, p. 1264) was put forward by Henion and Kinnear (1976, as cited in Dangelico & Vocalelli, 2017).

In order to address the growing sustainability concern of consumers (Carrington et al., 2010, Bray et al., 2011; Maloney et al., 2014), brands employ green marketing strategies. It is important to acknowledge that the sole focus is not to create new marketing strategies, but rather to incorporate environmental sustainability, thus making products more desirable for consumers (Dangelico & Vocalelli, 2017). The available definitions of the topic, while similar, differ in their degree of commitment to the sustainability cause. The terms green marketing, eco-marketing, ecological marketing and sustainability marketing

18

are related, thus addressing similar topics. Different definitions of the different terms may, however, take on different approaches where “green marketing” remains the “widely accepted” term (Papadas et al., 2017).

According to Prakash (2002, p. 285) for example, green marketing employs “environmental claims” about products or business processes. Later definitions, such as Belz and Peattie (2009, p. 605, as cited in Kumar et al., 2013) go beyond mere claims addressing environmental sustainability and integrate “the building and maintaining [of] sustainable relationships with customers, the social environment and the natural environment”, thereby addressing all areas of the Triple Bottom Line as defined by Elkington in 1994.

In order to address consumers’ growing sustainability concern, various brands have utilized marketing tactics based on environmental claims that indeed proved false (Furlow, 2010). The focus on mere claims about product attributes may be perceived as greenwashing and lead to consumer cynicism about sustainable products especially in the fashion context (Bray et al., 2011). Furlow (2010) further argues that consumer scepticism towards sustainability claims may result from an inability to understand the often complex topic of sustainability issues. According to Papadas et al. (2017), there is a need to differentiate between such “greenwash-driven” organizations and the “holistically-driven” ones (p. 244) as they differ in their respective strategies. The authors (2017) suggest that brands with a green marketing orientation (in their understanding) follow a holistic approach, integrating sustainability strategies on all levels of the organization.

3.2.3 Sustainable Fashion Marketing

In 2007, Kate Fletcher coined the term slow fashion calling for a systematic change in the fashion industry in order to incorporate a “vision of sustainability […] based on different values and goals” (Fletcher, 2013, p. 262) to the predominant fast fashion model. According to Vehmas et al. (2018), the fashion brands aim to utilize sustainability as a provider of competitive advantage. The slow fashion concept has oftentimes been misunderstood as the literal opposite to fast fashion and has thus been used as a term describing allegedly more sustainable (‘slower’) clothing items that were still produced under the predominant industry-common paradigm (Fletcher, 2013).

19

Rather than employing holistically designed strategic approaches to sustainability values (Papadas et al., 2017), it is suggested that the term slow fashion has been used as a marketing ploy (Fletcher, 2013), thus entailing potentials of greenwashing (Furlow, 2010).

While Joy et al. (2012) suggest that luxury brands could excel in fashion sustainability due to the inherent focus on timelessness and high quality, other forms of sustainable fashion have emerged. A clear definition of sustainable fashion may prove difficult to name with interpretations differing across the industry (Lundblad & Davies, 2016). Yet, Joergens (2006) suggests that sustainable fashion incorporates the utilization of sustainable materials for garment production, ethical working conditions and an overall sustainable business model, thus proposing a similarly holistic green marketing approach (Papadas et al., 2017) in the fashion context. Different forms of such fully sustainably marketed fashion include, but are not limited to, second hand or vintage clothing, upcycled clothing or clothing produced under sustainable conditions.

Second-hand sale and upcycling of clothing and textile waste represent methods of preserving the value embedded in materials and products as is typical of circular business models (Lewandowski, 2016; Nußholz, 2017). The main focus of products designed under a circular paradigm is to extend their life through, for example, maintenance and repair as well as ensure the composition of reusable and recyclable materials from the point of production (Lewandowski, 2016; Nußholz, 2017).

Circular fashion business models, as practical implications of circular economy theories, thereby intend to keep materials and products in a closed loop (Vehmas et al., 2018). These models require the “building and maintaining [of] relationships with consumers” (Lewandowski, 2016, p. 17) as an underlying aspect for the functioning of these circular systems. McNeill et al. (2020) determined the value consumers perceived in their garments as an important determinant for their willingness to make efforts to extend their life. Consumers were only interested in engaging in life extension practices of their clothes (McNeill et al., 2020), when the perceived value of the respective garment was high enough for consumers to want it to last (Armstrong et al., 2015). Sustainable fashion brands thus need to ensure that consumer perception of their garments maintains high even after the purchase occasion. Jacoby et al. (1977, as cited in Degenstein et al., 2020),

20

found that the initial purchase price as a factor increasing perceived value also provided an important determinant of later disposal decisions, resulting in higher likeliness of reuse (Degenstein et al., 2020).

Within fashion, the adoption of circularity in terms of upcycling and reuse of materials is considered a fairly new concept (Niinimäki, 2017), yet provides an effective means of increasing the sustainability of fashion textiles as well as marketing it as such.

Although both, second hand/vintage and a circular paradigm express sustainable approaches to fashion marketing, Park and Lin (2018) and Vehmas et al. (2018) found that consumers’ perception of upcycled (i.e. circular) garments outweighed those of second hand clothing as the former were perceived as “basically [...] new” (Vehmas et al., 2018, p. 292). Indeed, second hand shopping was not connected to consumers’ sustainability values, but rather focused on attempts to find individual pieces or save money (McNeill & Moore, 2015). Vehmas et al. (2018), however, suggest that consumers expect circular fashion items to match quality standards of clothes produced of virgin materials. Maintaining high quality of sustainable fashion clothes is therefore of vital importance (Lundblad & Davies, 2016).

3.3 Communication and Distribution

In order for green marketing strategies to be effective with regards to sustainability and consumer purchasing behaviour, they need to be communicated to consumers in an adequate way. Yan et al. (2010) argue that the marketing strategies companies use need to be adjusted to communicate what qualities the products have with regards to sustainability. Such messages are more likely to result in positive responses where the given message is informative and thus provides clarity with regards to sustainability (Yan et al., 2010). Guedes et al. (2020) argue that the marketing of sustainable fashion brands requires improvement while suggesting that positively framed marketing messages could provide a relevant tool for encouraging consumers’ willingness to purchase sustainable fashion. In fact, findings made by Vehmas et al. (2018) suggest that consumers perceived most sustainable fashion marketing as too guilt-inducing and instead asked for positively, or at least neutrally phrased messages.

21

One way to communicate a more neutrally phrased message to the consumers can be done through a highly valued marketing strategy known as storytelling. With this strategy both the product's qualities as well as the company's overall sustainability mission can be communicated and thus constitute an emotional connection for the consumer (Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010).

3.3.1 Storytelling

Although storytelling is not a new concept, the growth of storytelling within business shows that using it as a marketing strategy is becoming more common within any industry (Canziani et al., 2019). James and Minnis (2004) argue that storytelling is used to “facilitate knowledge sharing, guide problem solving and decision making, and generate commitment to change.”, thus, it can be used in order to create an emotional connection between consumers and companies within the fashion industry. The strategy can also be used in order to increase a company’s position on the market since it can contribute to a positive company image (Canziani et al., 2019).

Herskovitz and Crystal (2010) argue that consumers create a story based on the perception they have of the company. Adopting storytelling can therefore help change this perception into one that the company wishes to portray. There are no rules to whether a company should use real or imaginary information when creating the company story, although sustainable companies tend to be transparent through their storytelling in order to share the knowledge they have about the industry with their consumers. Since sustainably aware consumers tend to search for a clear indication of environmentally friendly products to avoid greenwashing (Yan et al., 2010), embedding terms related to sustainable practices, such as; “green, organic, eco” etc. into their marketing practices, i.e. when telling their story will favour sustainable companies within the industry. Thus, being accessible for the consumer through transparency about the company values and practices, whilst embedding the mission into the story can lead to higher trustworthiness within the market.

Having a positive company story can as mentioned shape the perception consumers have of the company. The message that the company wishes to deliver can, if positive, also bridge the gap of attitude behaviour towards sustainable fashion since it is said that positively delivered information can affect behaviour through an emotional engagement

22

(Guedes et al., 2020). Glover (2017) states that “a story in a selling sense is just a conversation you have with someone explaining the product’s virtues”, thus having an honest conversation about the company story can help strengthen the relationship to the consumer, whether it is through online marketing channels or within physical retailing. However, since sustainability is linked to values, any evidence showing that the practices the brands portray as sustainable are not in fact true, it can heavily damage the brand and therefore their business (James, & Montgomery, 2017).

3.3.2 Retailing

Retailing is, according to the Cambridge dictionary “the activity of selling goods to the public in stores or on the internet”. Thus, retailing is necessary in order to get the products from the brand to the consumers. Retailing has been around for a long time, but as the fashion market grows and digitalisation becomes more apparent, a paradigm shift is inevitable (McCormick et al., 2014). The paradigm shift in the fashion industry is nothing new, although it has had an increase recently, Sorescu et al. (2011) argue that“most large retailers have morphed into multichannel firms, where the same customer visits the retailer via different channels for different purposes […]”. With the growth multichannel retailing has seen over the last 10 years (Kautish & Sharma, 2018), it is no surprise that the presence of the online retailing has increased drastically and will continue to do so (Ha & Stoel, 2012).

The access of information as well as the purchase availability can be seen as one of the reasons why there has been an increase in online retailing (McCormick et al., 2014). One could argue that digitalisation has had a positive impact on the retailing industry at large, since the industry has seen a steady increase as a result of multichannel retailing (Ha & Stoel, 2012). Along with this increase comes new responsibilities for the companies on the market, one of them being consumer satisfaction. By offering a holistic shopping experience, the consumer does not only leave the store satisfied but it might also entail customer loyalty, thus ensuring that the consumer will return to the store once more due to a sentimental bond to the retailer (Caro et al., 2020).

Online retailing has certainly had an upswing in the last decade and will continue to increase as long as the availability it has brings value to the customer. Although this is the case, McCormick et al. (2014) argues that “the biggest proportion of apparel sales

23

currently comes from traditional retail formats such as street vendors.”, showing that physical retailers are still very present in the industry and as long as the quality of said physical store remains, customers will choose to use one or the other, or in some cases both channels of retailing (McCormick et al., 2014).

3.4 Consumer Behaviour 3.4.1 Fashion and Identity

The concept of identity has played an important role throughout the history of human existence. In pre-modern societies, such as during the middle ages, people’s identities were predefined and confirmed through their respective position or belonging to different groups within society, or even occupation (Berger & Luckmann, 1967; Bauman, 1988). Nowadays, the concept of identity has become highly individual. In today’s Western societies, often stereotyped as being “highly materialistic” (Solomon, 1996), the self is often expressed through the goods and services an individual chooses to consume. Clammer (1992) mentions that the “acquisition of things” also encompasses “the buying of identity” (p.195) as a means of communicating the social status the consumer wishes to portray outwards. Thus, while previously a person's identity and social status were defined by the social context he or she was born into, it has now become a narrative told through the construct of the individual (consumption) choices he or she makes (Giddens, 1991).

According to Belk (1988), the notion of “people seek[ing], express[ing], confirm[ing], and ascertain[ing] a sense of being through what they have” (p. 146) may be central to understanding consumer behaviour. Materialism, here defined as the value people assign to material possessions (Solomon, 1996), has been identified as an important criterion in determining consumer involvement (O’Cass, 2004). Involvement with a product or activity refers to the degree to which the consumer considers the product or activity a central part of their life based on personal perceptions and values (O’Cass, 2000; Bian & Moutinho, 2011). According to O’Cass (2004), materialistically minded consumers “favour[…] those possessions that are worn or consumed in public”, valuing product attributes such as “utility, appearance, financial worth and ability to convey status, success and prestige” (p. 871). As a prime example of a publicly consumed good,

24

clothing, for example, can become a main component in constructing the image of oneself one wishes to project to the outside.

The fashion industry as a provider of apparel thereby allows consumers to build an identity through their clothing (Crane, 2012). The more consumers are involved with fashion, the higher the relevance fashion holds to the consumer’s identity (O’Cass, 2000). Tigert et al. (1980, as cited in O’Cass, 2004) suggests women to show a higher degree of fashion involvement. The ever-increasing rate of fashion consumption globally provides evidence for the significant position fashion clothing holds in people’s lives and the societal function it fulfils. Fast fashion in particular has allowed individuals to continuously reinvent themselves in line with the constant change in fashion trends they aim to adapt to (Cachon & Swinney, 2011; Gabrielli et al., 2013).

3.4.2 Sustainable Consumption and Consumer Attitudes Towards Sustainable Fashion

In line with increases in public recognition of sustainable development, consumers’ general awareness of sustainability issues has grown over the past years (Carrington et al., 2010; Bray et al., 2011; Maloney et al., 2014). Subsequently, sustainable consumption has gained increasing attention in academic literature. Researchers often utilize the terms sustainable or ethical consumption interchangeably in order to refer to consumption behaviour aiming at minimal negative environmental, social or ethical consequences of the goods and services purchased (Burke et al., 2014; Johnstone & Lindh, 2017).

Pro-environmental values and ethical concern have been linked to increasing the likelihood of sustainable purchasing behaviour (Grob, 1995; Hiller Connell, 2010), but cannot be considered to surely predict sustainable purchasing decisions. Although consumer awareness of sustainability issues concerned with their consumption behaviour has grown (Dickson, 2000; Carrington et al., 2010; Bray et al., 2011; Maloney et al., 2014), their values often do not translate into sustainable purchasing behaviour (Boulstridge & Carrigan, 2000; Carrington et al., 2010; Johnstone & Tan, 2015). In fact, the attitude-behaviour gap or cognitive dissonance within ethical consumption is a well-established phenomenon in contemporary literature (Bray et al., 2011). Academic conclusions on the exact cause of the gap remain divided (Davies et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2015), thus requiring further research in order to build a sound understanding of sustainable consumption decision-making (Johnstone & Lindh, 2017).

25

Academic research has only recently (re-)gained interest in the topic of sustainable consumption behaviour in the fashion industry. An industry characterised by materialistic values, short product life cycles and excessive consumption seems to stand in direct contrast to a sustainability-led approach (Niinimäki, 2010; Lundblad & Davies, 2016). With a consumer base utilizing clothing as a means of allowing constant reinvention of the self, the contemporary (fast) fashion industry may appear mutually exclusive to the concept of sustainable or slow fashion which incorporates ethical production practices, sustainable materials and products made to last (Fletcher, 2013). Despite these seemingly unbridgeable differences, the sustainable fashion market has enjoyed increasing popularity and a broad range of fashion brands has, at least to some extent, adopted or partially adopted the sustainable fashion concept. The available body of literature on the consumption behaviour of consumers of sustainable fashion is limited yet, but still provides insightful understandings of factors impeding sustainable fashion consumption needed to be taken into consideration by marketers aiming to bridge the attitude-behaviour gap.

Several studies have attempted to capture factors influencing sustainable consumption decision-making within the fashion industry (e.g. Hiller Connel, 2010; Bray et al., 2011; Chan & Wong, 2012; Lundblad & Davies, 2016; Park & Lin, 2018). In line with previous research on ethical consumption, those fashion consumers having previous knowledge and concern for environmental and social issues show a higher tendency to demonstrate sustainable fashion consumption behaviour (Lee, 2011; McNeill & Moore, 2015; Park & Lin, 2018). Consumers of sustainable fashion also often presented higher levels of education (Park & Lin, 2018). At the same time, consumers highly involved in fashion as a means of enhancing self-image appear to be frequent consumers of fashion clothing (Tigert et al., 1976; McNeill & Moore, 2015; Park & Lin, 2018). McNeill and Moore (2015) pointed out that these consumers only considered issues of sustainability when it incurred personal benefits, but were generally less concerned with environmental and social consequences of their consumption behaviour. The latter are thus more likely to fall into fast fashion consumption patterns and are according to Lee (2011) unwilling to sacrifice style on behalf of sustainability.

In their study on fashionable consumers’ attitudes towards sustainability, McNeill and Moore (2015) identified three types of consumers with varying prospects of providing an

26

attainable market for sustainable fashion: the previously described highly fashion involved ‘Self’ consumer, the ‘Social’ consumer and the ‘Sacrifice’ consumer. While the ‘Social’ and ‘Sacrifice’ consumers both showed concern for sustainability and ethical issues to some extent, ‘Sacrifice’ thought negatively of the fast fashion and thereby perceived least barriers to the consumption of sustainable fashion. In fact, ‘Sacrifice’ consumers even avoided fashion brands they perceived as fast fashion-oriented (McNeill & Moore, 2015).

The ‘Social’ consumers, (McNeill & Moore, 2015) however, fell victim to the attitude-behaviour gap often described in sustainable consumption literature (e.g. Boulstridge & Carrigan, 2000; Carrington et al., 2010; Johnstone & Tan, 2015). Whilst expressing social and environmental concern, this large group of consumers perceived certain barriers to executing fully sustainable fashion consumption behaviour. Although subjective norms (i.e. values) increased likelihood of purchasing sustainable apparel (Park & Lin, 2018), a study conducted by Bray et al. (2011) pinned down seven factors hindering sustainable consumption behaviour, some of which relating to price sensitivity, lack of information on ethical choices and quality concerns. In fact, garment quality (Niinimäki, 2010; Vehmas et al., 2018) as well as the utilitarian value (Park & Lin, 2018) hold a focal position when deciding for or against the purchase of sustainable clothing. Consumer perceived value as a trade-off between perceived benefits and sacrifice (Eggert & Ulaga, 2002). As reported by Freestone and McGoldrick (2008), in order to accept price premiums concerned with ethical products, the ethical benefits need to exceed the perceived financial sacrifice. McNeill and Moore (2015) additionally deemed unawareness and perceived lack of social acceptance for sustainable clothing as influencing factors. Social pressure and peer opinions are thus considered to have potential of increasing consumer willingness to adopt sustainable fashion consumption practices for this group of consumers (McNeill & Moore, 2015; Park & Lin, 2018). Considering the adverse sustainability impacts of the fashion industry, changing consumption patterns in the industry is of vital importance in order to drive global sustainable development forward. Taking into account the highly involved fashion consumers’ role in the fashion adoption process (Tigert et al., 1976; O’Cass, 2004), marketers’ motivation efforts should not only focus on bridging ‘Social’ consumers perceived barriers, but also on encouraging ‘Self’ consumers to change their ways.

27

Bick et al. (2018) suggest that fashion consumers hold a significant role in improving environmental sustainability in the fashion industry. The authors (2018) argue that in order for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 12 Responsible Consumption and

Production to be met, consumers need to revert to the traditional “less in [sic] more”

philosophy over the currently prevailing “more for less” notion (p. 3). Thus, marketers of sustainable fashion brands hold a significant role in bridging consumers’ attitude-behaviour gap and subsequently signalling to the fashion industry that change is needed.

28

4. Empirical Findings and Analysis

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The following section will present the empirical findings and their analysis. Following one of the two typical layouts of a research report as suggested by Jarl Backman (2008), the empirical findings and analysis sections were combined in order to avoid repetitions and enable a clearer depiction of the discovered themes and their meanings.

______________________________________________________________________

4.1 Perceived Sustainability Issues within the Fashion Industry

In order to develop a better understanding of the industry-context in which the following marketing approaches were designed, interviewees were questioned about their perception of current issues within the fashion industry. The findings pinpointed in this section provided a helpful basis in attaining a deeper comprehension of how the marketing strategies utilized by the participating brands were aimed at differentiating the respective brand from other industry players.

The main industry issues the participants identified in terms of sustainability were the excessive fashion consumption as well as the quality and amount of fashion garments being produced. Anna, for example, stated:

“Fashion has an overproduction and overconsumption problem, right?

You just can’t get around that.”

Indeed Brick et al. (2018) proposed a reduction in fashion consumption to be required in order to induce sustainable development within the fashion industry, thus supporting the participants’ concern of the issue. Consumers’ lack of understanding of the connection between the finalized textiles and the and the number of resources and labour required to produce the product they purchased was named as a potential cause for the unsustainable overconsumption of fashion goods. While in contemporary literature, consumers are said to have an increasing general awareness for the environmental and social issues relating to their consumption choices (e.g. Dickson, 2000; Carrington et al., 2010, Maloney et al., 2014; McNeill & Moore, 2015), the participants in our study indicated that consumers did not connect the understanding of these issues to the actual product:

29

“There’s quite a disconnect between what the consumers understand about the products that are produced, so in terms of the textiles themselves, and what’s actually put out there by the companies that produce fashion.” – Lisa McNeill

Hinting at the attitude-behaviour gap as described in sustainable consumption research (e.g. Boulstridge & Carrigan, 2000; Carrington et al., 2010; Johnstone & Tan, 2015), the participants thereby asserted that when considering the purchase of a finalized product, consumers did not think of the actions required preceding the purchase occasion.

“I think it’s really easy to forget when you see something hanging in a shop, like the finished garment, the number of hands, and the number of hours, and the number of places that something has been in, and the labour involved in it.”

- Anna

In line with the empirical findings, consumers’ (unintentional) neglect could thus be accredited to the impulse-driven character common for fashion consumption behaviour (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). With fashion garments as publicly consumed goods being utilized to create or enhance self-images (O’Cass, 2004; Crane, 2012), it seems reasonable to conclude that the type of consumers the participants were describing when talking about the general fashion industry represent the typical highly involved fashion consumer, or the ‘Self’ consumer as described by McNeill and Moore (2015).

Despite consumption decisions ultimately being in the consumers’ hand, the participants laid a large responsibility for changing such behaviour on the side of fashion brands. Although most participants acknowledged contemporary fashion brands’ efforts of including sustainably produced product lines into their offerings, they criticized the prevalent trend-based, linear business model (Barnes & Lea-Greenwood, 2006) these companies were following and continued that aims to introduce better production practices could not offset the adverse effects of short-term use of such garments:

“Because you can also see fast fashion brands [...] doing whole collections being sustainable and doing it with organic materials and stuff. But then they’re not looking at the fact that in the last 20 years, clothing consumption has increased by 60%. So their business model is