1

Version approved by examiner

Occupation as means and ends in early

childhood intervention – A scoping review

Evelin Fischer

Thesis, 15 credits, one-year master

Occupational Therapy

Jönköping, May, 2019

Supervisor: Dido Green, Professor

2

Abstract

Background: Occupational therapy (OT) plays an important role in providing early

childhood interventions for children with developmental delay. While paediatric OT has long been guided by developmental principles, occupation-centred interventions have been promoted during the last decades, but no unifying definition exists about the core features. Aims/Objectives: The aim of this paper is to (a) identify and describe how occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions are demonstrated in paediatric occupational therapy for infants and young children with developmental delay, (b) identify which outcomes these interventions address and (c) analyse which outcome measures are used. Material and Methods: Eight databases and 15 OT journals were searched. Included studies were peer-reviewed primary sources published in English since 1999, selected based on the terminology proposed by Fisher (2013). Nineteen papers met inclusion criteria. Results: Eight occupation-based, two occupation-focused and nine occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions were identified. Outcomes related mainly to occupational and play skill acquisition as well as mastery of co-occupations. A limited number of occupation-focused outcome measures was implemented. Conclusions: Several occupation-centred interventions have been researched. Gaps in knowledge exist regarding measures taking into account (co-)occupational performance and young children’s perspective. Significance: OTs might want to expand their scope of practice to include all occupational domains and increase parent-delivered interventions in natural environments. Measures used should be relevant to occupational performance and take into account the parent’s and children’s view. Use of uniform terminology can aid identification of evidence and clear placement of OT among other professionals.

Keywords: Developmental delay; early childhood; intervention; occupational therapy;

3

Introduction

Occupational therapists (OTs) play an important role in early childhood interventions promoting children’s development, occupational performance and participation in domains such as play, self-care, and social interaction [1-3]. Traditionally, OT services with young children have been guided by developmental theories focusing on changing performance components to promote occupational performance [4-7]. Nowadays, early intervention services are moving towards family-centred care in natural environments and the support of parent-child interactions [8-11]. The assumption that changing performance components will automatically result in occupational outcomes has been doubted by several authors [12-16]. Humphry [17] further criticizes that this assumption is not in line with OT’s belief that occupations arise from person-environment interactions.

In OT, a shift back towards the original focus on occupation has been under way for several decades [18,19], leading to more occupation-centred interventions, collaborative goal setting and outcomes focusing on improved activity and participation rather than changes in

performance components [14,20]. In paediatric practice, the interconnectedness of the child’s occupational performance with the occupations of parents or other family members also needs to be taken into account [21-23]. Parenting occupations play a central role in providing

children with opportunities to develop and enhance their occupational performance

[21,24,25]. The concept of co-occupation has been introduced to capture the highly interactive nature of occupations of two or more persons, such as mothers and children [26,27].

Within the profession, a differentiation has been made of occupation as means, i.e. as a medium of intervention, or as ends, i.e. the ultimate goal being increased quality of

4

and occupation-based are being used, sometimes interchangeably, and no unifying definition of their core features exists [12,31-33]. Consistent definitions of core concepts are important both as a prerequisite for a profession’s research and evidence-based practice as well as for professional identity, reputation and communication with other professions [34-37]. Fisher [12] suggests the use of uniform terminology with occupation-centred as an overarching concept and a differentiation between occupation-based practice which uses active engagement in occupation as the main ingredient of intervention, and occupation-focused practice which immediately focuses on occupational performance instead of on changing underlying components or environmental factors in order to improve occupational

performance. Fisher [12] specifically defines occupation as meaningful and purposeful doing in the way it ordinarily occurs in a person’s daily life.

Several systematic reviews have been conducted investigating the effectiveness of OT in early childhood interventions [3], but no review of occupation-centred interventions for young children could be identified in a preliminary search using the databases AMED, CINAHL, PubMed and PROSPERO with the search words: review, based, occupation-centred, occupation-focused, intervention, therapy, treatment, practice and program.

Definition of core concepts used

For the purpose of this review, the concept of occupational performance is defined based on the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model [38]. See Figure 1.

Insert Figure 1

The PEOP model assumes that occupational performance arises from a complex, dynamic interaction of person, environment and occupation [38]. According to the model, occupational

5

performance is influenced by enablers or barriers within the person, environment or

occupation with successful occupational performance promoting participation and well-being [38,39].

Developmental delay is defined based on Dornelas, Duarte and Magalhães [40] and can occur along with several childhood conditions including preterm birth, neurological diseases such as cerebral palsy, genetic aberrations such as down syndrome, mental retardation or autism which result in delayed acquisition of motor, cognitive, language, and social skills. The delay can also be transient or without clearly defined underlying pathology [40].

Outcomes measures are tools used to measure change in a person’s occupational performance or engagement in order to determine the success of an intervention. Features or abilities that are expected to be influenced by intervention are therefore being quantified and measured at a minimum at the beginning and end of an intervention. Consistent with client-centred practice, the focus of an outcome measure should be of importance to the client [41].

Purpose/Aim

The aim of this paper is to (a) identify and describe how based and occupation-focused interventions are demonstrated in paediatric occupational therapy for infants and young children with developmental delay, (b) identify which outcomes these interventions address and (c) analyse which outcome measures are used.

Material and Methods

A scoping review was chosen since it is appropriate to explore and map available research, identify gaps in the literature and lay a foundation for future research [42-45]. This scoping

6

review was performed based on the Arksey and O’Malley framework [42], informed by recommendations of Levac et al. [43] as well as guidelines provided by the Jonna Briggs Institute [45]. Findings are reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews [46].

Arksey and O’Malley [42] outline five steps in conducting a scoping review: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. Objectives, inclusion criteria and methods were specified prior to initiation of the search [45].

Identifying the Research Question

The scoping review question was formulated as “How is occupation-centred practice

demonstrated in paediatric occupational therapy for infants and young children with

developmental delay?"

➢ What occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions are demonstrated? ➢ What are the main outcomes addressed in these interventions?

➢ Which outcome measures are used?

Identifying relevant studies

Search words were derived based on the person, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) framework [47,48] and expanded through synonyms using thesaurus and literature relevant to the topic to identify concepts relating to occupational performance [49] and alternative terms for occupation-centred interventions [14]. Using terminology and definitions of occupations and occupational performance summarised by Reed [50], participation was included as an

7

outcome to capture literature involving engagement in play or activities of daily living (ADL) within the child’s sociocultural context [51].

A three-step search strategy was implemented as recommended by Peters et al. [45]. Firstly, databases CINAHL and MEDLINE were searched using keywords based on the PICO-model (Table 1).

Insert Table 1

Text words contained in titles and abstract as well as index terms were screened to identify

additional keywords and the terms ‘neonate, special needs, treatment, rehabilitation and co-occupation’ were added. Secondly, relevant databases (AMED, CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, PsychInfo, OTSeeker, Cochrane, Scopus) were searched using all identified keywords and relevant major headings or MeSH terms. Online issues of 15 OT journals were searched to identify additional literature and grey literature was searched using ProQuest Dissertation and Theses. All searches were performed between 05-03-2019 and 13-03-2019. Thirdly, reference lists of included studies were searched. Included studies were limited to peer-reviewed

literature published in English. Since the last two decades have seen a stronger push towards implementation of interventions focusing on occupation [34,52,53], only literature published since 1999 until March-2019 was included. Full search strategy can be found in Appendix 1.

Study Selection

Papers were included in the scoping review if they were peer-reviewed and reported on an OT intervention for children with developmental delay age 0-5 years. Studies with a broader age range were included if they provided a separate analysis based on the relevant age group. Intervention studies were selected if they were consistent with the definitions for occupation-based (OB) or occupation-focused (OF) practice proposed by Fisher [12], delivered by OTs

8

and provided a clear description of the intervention used and information about ethical procedures, i.e. ethical approval or informed consent.

Definitions proposed by Fisher [12] were chosen since they provide a clear distinction of concepts. Descriptions of intervention procedures and intended outcomes were read

repeatedly and mapped onto Fisher’s definitions [12] to classify interventions as OB or OF. If multiple publications were identified referring to the same sample, the publication with the most comprehensive reporting was chosen for inclusion, but information from background documents, such as study protocols, were taken into account for qualitative synthesis if necessary. Ambiguous studies were included as OB if more than 50% of intervention

strategies used occupation as means of intervention and as OF if at least one primary outcome measure was occupation-focused or the main outcome was occupational, e.g. enjoyment of mealtimes rather than improvement of oral-motor skills. If ambiguity existed, it was discussed with the supervisor and in two cases authors were contacted to clarify details regarding study population and intervention procedures [54,55].

The initial search strategy yielded a total of 678 documents after duplicates were removed (see Fig. 2 for data selection process).

Insert Figure 2

Of these 413 were excluded because the title indicated that the study did not report on a paediatric occupation-centred intervention. After screening of 265 abstracts, 90 articles were eligible for full-text review. Applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 19 articles were selected to be included in the review. Thirty-nine of the 90 articles were excluded due to lack of separate analysis for the age group 0-5 years and 26 for other reasons. Among the

9

excluded papers identified as OT interventions within the specified age range, 17 could not be classified as OB or OF, e.g. interventions at the neurobehavioral level, sensory integration, training of decontextualized skills or developmental domains. Five studies generally met inclusion criteria, but did not provide information about ethical procedures and were therefore excluded. One article describing a relationship-based intervention could not be accessed via university or author [56].

Charting the Data

A data-charting form was created and applied to all included studies [42,43] recording: author, year of publication, geographical location, population characteristics and sample size, short description of intervention, practice setting, research method/study design, intended outcomes, outcome measures and results (Appendix 2). Based on recommendations of Levac et al. [43], the data charting form was initially used on five studies to determine whether extracted data was relevant for answering the research question. As common in scoping reviews, critical appraisal of included studies was not performed [42].

Collating, Summarizing and Reporting

Numerical analysis was performed based on the extracted data and outcomes were reported based on occupational domains [49] relevant to the age group.

Additionally, categories of practice were identified using methods of qualitative content analysis [57,58]. Therefore, extracted data was synthesized into three tables grouped by intervention features (OB, OF, OB+OF) including authors and year, intervention description and outcomes. Descriptions of intervention procedures and outcomes were read repeatedly to identify categories of practice.

10 Ethical Considerations

This review followed general ethical considerations based on the ‘Declaration of Helsinki’ [59] and the principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice and non-maleficence to ensure honesty and integrity in all phases of the review process [60,61]. Since this is a review study without direct involvement of participants, no ethical approval was obtained [62].

Autonomy: Autonomy includes a client’s ability to make informed choices [61] which is

consistent with client-centred OT. Occupation-centred interventions can help to ensure that activities and outcomes addressed in OT intervention are meaningful to a client’s life situation. The use of uniform terminology can aid in positioning occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions more clearly and help families take informed decisions that best suit their needs. The concept of autonomy was taken into account by including only studies in the review which obtained informed consent from participants. Research with young children requires special ethical considerations and the child’s as well as the parent’s perspective should be taken into account [63,64].

Beneficence and non-maleficence: The aim of this review is to provide information which can

inform practitioners about how occupation-centred early childhood interventions are

demonstrated in intervention studies. Additionally, the results can provide a basis for further research. The author set out an objective and transparent process in order to minimize bias and allow for replication of search process and analysis [65,66].

Justice: This review includes only studies which provided information about ethical

procedures, such as ethical approval or informed consent [67,68] to ensure sampling, recruitment, intervention and data management were undertaken correctly and fairly [69].

11

Results

Results of numerical analysis are presented first, followed by results of thematic analysis outlining categories of occupation-centred practice as well as outcomes addressed and outcome measures used.

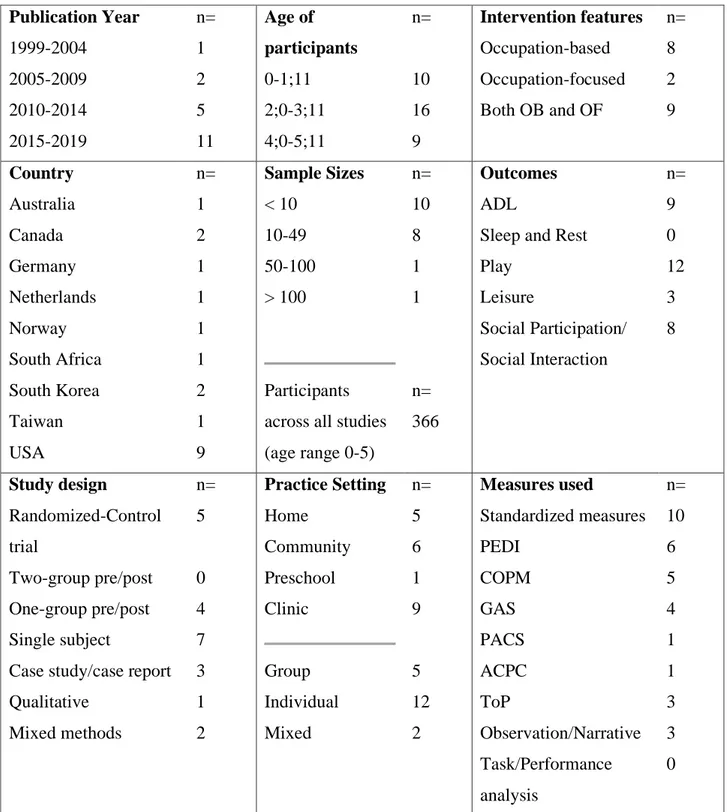

Most studies were conducted in western countries (n=15) [54,55,70-82], especially the United States (n=9) [55,71-75,78-80], and used quasi-experimental or descriptive rather than

experimental designs with small sample sizes (Fig 3). A majority of studies were published during the last 5 years (n=11) [54,55,70,72,74,75,79-81,83,84].

Insert Figure 3

While most identified studies were classified as OB (n=8) [54,55,72-75,79,84] or a

combination of OB and OF (n=9) [70,71,76-78,81-83,85], only two were classified as solely OF [80,86]. See Table 2 for summary.

Insert Table 2

In some cases, the description of intervention procedures or intended outcomes, did not provide sufficient information to classify as OF or OB.

Most studies provided direct interventions to children and their families (n=17) [54,55,70-79,81-85], most often in combination with parent education [54,55,70-72,74-78,81-83,85,86] and almost half were conducted in a clinic environment (n=9) [70,71,77,78,81-85]. Studies examined a wide range of populations, including for example children with cerebral palsy (n=6) [70,71,76,77,81,82], autism (n=4) [55,74,80,83], developmental delays (n=5) [55,72,75,85,86], or prematurely born infants (n=1) [78].

12 Occupation-based Interventions

Promoting Play. The occupation-based interventions focused mainly on play, with five

studies implemented as playgroups in community-settings [55,72,74,75,79]. These included two community-based playgroups for children with developmental delays [55,75], and one aquatic playgroup for children with autism [74], focusing on promoting play and parent-child interaction. Another therapeutic playgroup promoting peer play as well as language and motor development was implemented in a day-care centre by OTs and speech and language

pathologists (SLPs) [72]. One intervention provided an inclusive playgroup setting with opportunities for unstructured play and examined effects of a powered ride-on car on play behaviour and peer interaction for children with mobility-related disabilities [79]. Another used a non-powered mobility device within individual free play sessions with scaffolded support to promote engagement in play for children with severe mobility limitations [84].

Motor Skills Training. One OB intervention provided constraint induced movement therapy

(CIMT) in the home environment [73] for a young child with cerebral palsy (CP). The intervention focused on improving performance skills such as upper extremity reach or bilateral hand use.

Additionally, one paper was included as questionable. The paper described equine-assisted therapy for toddlers and their mothers with the intention to provide positive shared

experiences and improve maternal caregiving and attachment [54]. While horse-riding might not be considered a typical occupation for toddlers in western cultures, in cultures where equine animals are commonly used in daily life, it could be.

13 Occupation-focused Interventions

Promoting Everyday Function. The two OF interventions consisted of coaching for parents of

children with autism within an enriched home environment program [80] or other

developmental delays within a routines-based approach [86]. The focus was on changing barriers in the environment in combination with modification of tasks or routines to improve occupational performance.

Interventions both Occupation-based and Occupation-focused

Occupational and Motor Skills Training. Five of the nine interventions identified as OB and

OF were directed towards outcomes relevant to everyday functioning [71,76,77,81,82], often provided either by OTs or physiotherapists (PTs)[71,77,81,82]. The interventions consisted of providing intensive structured task practice for children with CP [82] including a study

comparing hand-arm bimanual intensive training (HABIT) and CIMT [71]. Further, two interventions consisted of modification of task or environment with the goal of promoting occupational performance in daily occupations, e.g. tying shoe-laces or self-feeding including family-centred functional therapy [76] and a context-focused intervention [77]. Another study describing a context-focused intervention for children with CP [81] was added as

inconclusive. Descriptions of activities used during intervention and outcome areas addressed were insufficient to ensure that the intervention was really OB and OF [81,87].

Experiencing Co-occupation. The other four studies classified as both OB and OF provided

hands-on training of everyday occupations and opportunities for parent and child to

experience these co-occupations in a positive manner. Two interventions focused on feeding occupations, combining parent coaching and hands-on training during mealtimes, for an infant [78] and a 16-month old boy [85] with complex medical needs. Further, a

relationship-14

focused intervention was implemented with a 20-month old girl with CP and her mother combining engagement in child-led free play sessions with parent coaching to promote play, attachment and mother-child interactions [70]. Finally, one intervention for children with autism combined engagement in free play with sensory strategy use and hands-on training for parents [83].

Outcomes and Outcome Measures

Most studies focused on outcomes in the areas of ADL or motor skill acquisition, engagement in play or social interaction with parents or peers. None of the studies focused on outcomes related to the domains sleep or rest. A variety of different outcome measures were used (n=30), with the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI; n=6) and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM; n=5) being the most widely used ones. See

Table 2 for summary. Outcome measures identified as occupation-focused included the

COPM, PEDI, Preschool Activity Card Sort (PACS), Assessment of Preschool Children’s Participation (APCP), Performance Quality Rating Scale (PQRS), and the Routines-based Interview (RBI). These were implemented in OF and OF+OB interventions and were most often combined with component-focused measures such as the Assisting Hand Assessment (AHA), Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM), Test of Playfulness (ToP) or Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Less than a quarter of papers (n= 4) [71,76,80,83] used only occupation-focused outcome measures. In OB interventions mainly component-focused measures were used. Three papers, all OF+OB, reported outcomes only narratively [70,78,85].

15

Discussion

This scoping review provides an overview of occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions for infants and young children with developmental delay based on the

definitions proposed by Fisher [12] and analysed outcomes and outcome measures applied. A considerable rise in publications displaying increased attention towards occupation-centred practice could be identified during the last five years, possibly linked to the publication of the International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) [88] in 2007. Nonetheless, the number of intervention studies which could be classified as occupation-based or occupation-focused was relatively small. Despite the fact that OTs have been encouraged to implement occupation-centred interventions for several decades [52,53], only 19 studies met inclusion criteria, most of them with small sample sizes. It has been criticized that translation from theory into practice is slow with practitioners still using “more traditional approaches directed at remediating impairments” [20,p.47].

Occupation-based and Occupation-focused Early Childhood Interventions

The included papers represent a variety of interventions mainly concerned with promoting play [55,72,74,75,79,84], ADL skills [71,73,76,77,81,82] and mastery of co-occupations [70,83,85,89]. Based on Fisher’s [12] definition of occupation which is specific to how occupations usually occur in a client’s daily life, interventions such as sensory integration were excluded since they use play, but not in the way it ordinarily unfolds in a child’s life. A broader definition of occupation such as proposed within the PEOP [38] might have led to the inclusion of different studies.

One factor complicating clear classifications based on Fisher’s [12] definitions was that several studies used a mix of intervention strategies and outcome measures focusing on

16

occupational performance and performance components likewise. The use of a combination of approaches rather than a single one seems to represent daily practice of paediatric OTs [90,91]. Some authors even argue that OT interventions might be most effective if occupation as the overarching paradigm is combined with approaches addressing performance

components [18,92,93].However, a recent systematic review of paediatric OT interventions found activity-based interventions using a top-down approach to be most effective [94].

Further, despite the findings that parent-delivered interventions are as effective as therapist-delivered ones [94], only two studies described OF parent coaching interventions [80,86] showing a field of research which can be expanded, especially for this young age group where occupational performance is so interconnected [21,22]. This is also true for interventions provided in natural environments which have been found to be most effective [3,94]. Only about half of the studies in this review were implemented in the home [73,76,80,86], preschool environment [72] or in community playgroup settings [55,72,74,75,79], representing a need for more research on how to better implement occupation-centred interventions in natural settings.

Outcomes and Outcome Measures

Regarding outcomes, the main outcome areas addressed concerned ADL, play and social participation. The occupational domain of sleep and rest was not covered in the included studies, despite the fact that sleep problems are common in young children with

developmental delays [95,96] impacting parental stress levels and mental health [97,98]. A review by Ho and Siu [99] found that sleep interventions provided by OTs for clients of all ages mainly used assistive devices or cognitive behavioural approaches, only a small number of interventions adapted activities or habits to improve sleep patterns. During the review

17

process, only one sleep intervention was identified using an assistive device for children with autism [95] which was excluded based on age range. This field of practice would benefit from more research.

When it comes to measuring outcomes of occupation-centred interventions, measures need to be compatible with OT values and suit intended outcomes [20,93,100]. Studies have shown that paediatric OTs frequently use outcome measures that are not conceptually congruent with the frames of reference or theories used [90,91]. During the review process, some studies were excluded due to a mismatch of aims and measures applied, e.g. developmental instead of occupational outcomes measured in a parent coaching intervention with the aim of providing autistic children with more opportunity to participate in community activities [101]. Although this review identified occupation-centred interventions, only a limited number of occupational performance measures were implemented, all of them in interventions with an occupation-focused component. It can be argued if PEDI and COPM, the most widely used outcome measures, qualify as occupation-focused measures. PEDI, in this review mainly used in studies with children with CP, combines items focusing on occupational performance with items focusing on performance components [102]. COPM, recommended as an appropriate tool to help parents set activity-based goals [103,104], was used to set occupational

performance goals, e.g. putting on a sweater, as well as goals focusing on performance components, e.g. bilateral hand use, in the studies included in this review. The same was true for Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), which was used in three papers to measure family-identified outcomes [81,82,86].

Setting clear occupation-based goals is an important prerequisite for measurement of specific outcomes [105]. In line with family-centred practice which takes into account parent’s

18

perspectives and values with regards to goal setting and delivery of intervention [106,107], most studies incorporated collaborative goal setting [71,72,76-78,80-83,85,86]. None of the studies however used child-report measures or family goal setting tools which also exist for younger children with varying psychometric properties [105,108,109]. If activities used in intervention are to be regarded as occupation they need to be meaningful to the child, regardless of age [110]. Interventions taking into account a child’s motivation and level of enjoyment have been found most effective [94,111] and studies with older children have shown that goals of parents and children can be quite different [112]. In order to acknowledge the parent’s and the child’s perspective in occupation-centred interventions, practitioners and researchers should use existing family goal setting tools and child-report measures and ensure that goals and occupations used in intervention are chosen by the client, not the therapist.

Finally, most of the studies focusing on promoting co-occupations [70,85] used only

observation to measure outcomes. There seems to be a need for occupation-centred outcome measures for research and practice that capture the impact of OT interventions on

occupational performance taking into account the interconnected nature of young children’s occupations. Further, DeGrace [113, p.347] has criticized that family-centred OTs should assist families in “’being’ a family engaged in meaningful occupations” rather than doing certain occupations which seems to be reflected to a certain extent in these studies with a focus beyond the child’s functioning on the child-parent dyad as a whole.

Since the studies included in this review were not critically appraised, the level of evidence for occupation-centred interventions with this age group cannot be determined. Questions regarding effectiveness could only be thoroughly answered via a systematic review which might want to include a broader age range to capture more relevant studies with larger sample

19

sizes. The small number of studies identified in this review shows the need for more

intervention studies with high-quality designs and rigorous implementation to strengthen the evidence-base for occupation-centred interventions with young children.

Use of Terminology and Communication about Occupation-centred Interventions Since the introduction of the ICF [114], the view of disability and health has changed and functional outcomes are gaining importance among health care professionals [115,116]. Therefore, OTs are not the only profession valuing goals relevant to occupational

performance. Several of the interventions included in this review (n=7) were provided by OTs and other professionals such as PTs or SLPs [54,71,72,77,81,82,86], two studies did not even include OT researchers [81,82]. Especially occupational and motor skills training seems to be an area of practice where OT and PT interventions overlap. This highlights the importance of clearly communicating the role of OT so we can be differentiated from other professions. Use of occupation-centred interventions and language representing OT’s core values can be a way of promoting OT identity and conveying the profession’s unique perspective [12,117-119].

Regarding the use of clear terminology, Rodger and Kennedy-Behr [14] suggest using the terms ‘occupation-centred’ and ‘performance-component-focused’ to differentiate approaches used in paediatric OT. Within the included studies, only a limited number of papers used the terms ‘occupation-based’ [55,78,85] or ‘occupation-centred’ [80], none of them used

‘occupation-focused’. Instead terms such as ‘family-centred functional therapy’ [76],

‘context-focused’ [77,81] or ‘routines-based intervention’ [86] were used. The use of uniform terminology across intervention studies, can aid in identifying evidence for OB or OF

interventions and facilitate communication within and outside the profession. In order to classify interventions as OB or OF, procedures used in intervention studies need to be

20

thoroughly described, which was not always the case in the included studies. A group of researchers has created a template for more precise reporting of interventions which might also be relevant for OT researchers [120].

Conclusion

This scoping review adds to existing knowledge about occupation-centred interventions for young children by providing an overview of intervention studies performed during the last two decades. Occupational therapists use a variety of occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions to promote young children’s occupational performance mainly targeting outcomes relating to the promotion of play and occupational skills in the domain of ADL as well as positive mastery of co-occupations. Interventions mainly combined strategies and outcome measures focusing on occupational performance with those focusing on performance components. A limited number of occupation-focused outcome measures was implemented, often not taking into account the interconnectedness of young children’s occupations. This study indicates the need for measures capturing the impact of occupation-centred interventions on occupational performance in all occupational domains relevant to young children’s lives, taking into account the family’s and the children’s perspectives and provides a foundation for future research, such as a systematic review. Further, results of this review point to the need of using uniform terminology across intervention studies to aid identification of evidence and help OTs communicate their unique role and perspective more clearly within and outside the profession.

21

Limitations

Although this scoping review was conducted based on the systematic approach by Arksey and O’Malley [42] using recommendations by Levac et al. [43] and guidelines provided by the Jonna Briggs Institute [45], several limitations remain. This review only included articles published since 1999 in English. Only online issues of OT journals were searched and grey literature search was limited to one source. Therefore, relevant articles might not have been identified. Further, several papers relevant to the research question could not be included in the final analysis due to a lack of information about ethical procedures or a broader age range without separate analysis for 0-5 year olds, including interventions such as home, summer camps, cognitive, and handwriting interventions. Studies identified in this review were mainly limited to western countries and results might therefore not be transferrable to other regions. Despite the author’s attempts to reduce bias, results should be viewed in the context in which they were created, i.e. intent, methods and selection of inclusion criteria directly influence results [66,121]. Since no uniform terminology has been accepted among OT practitioners and researchers [31,32], using alternative definitions as a basis for study selection might have affected the results substantially. Furthermore, despite recommendations [43,45], this scoping review was conducted by only one author during a time frame shorter than the 6 months recommended by Anderson et al. [44] and the recommended consultation phase [42] was limited to discussions with colleagues and supervisor regarding importance of the topic and research methods, increasing the risk of bias and individual errors.

Finally, the author’s limited research experience prior to undertaking the review may have affected the quality of analysis, e.g. in extracting and interpreting key findings [122].

22

Significance of findings

- OTs use a variety of occupation-centred interventions for infants and young children with developmental delay, often using a combination of intervention strategies and outcome measures focusing on occupational performance and performance

components.

- Occupation-centred interventions for young children should be expanded to more natural environments and address all occupational domains relevant to young children’s lives as well as include more parent-delivered interventions.

- Measures used in occupation-centred interventions should capture occupational performance outcomes and take into account the parent’s and children’s view.

Recommendations for future research

- The use of uniform terminology around occupation-centred interventions and a thorough description of procedures used in intervention studies can aid identification of evidence and communication with clients and other professionals.

- Occupation-centred outcome measures need to be developed for research and practice that capture the impact of OT interventions on occupational performance taking into account the interconnected nature of young children’s occupations.

- Effectiveness of occupation-centred interventions should be analysed via a systematic review, possibly taking into account a broader age range to capture more relevant studies with larger sample sizes.

Disclosure of interest

23 References

Studies included in the review are marked with *

1. Clark GF, Laverdure P, Polichino J, et al. Guidelines for Occupational Therapy Services in Early Intervention and Schools. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71(S2):1–10. 2. Arbesman M, Lieberman D, Berlanstein DR. Method for the systematic reviews on

occupational therapy and early intervention and early childhood services. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(4):389–394.

3. Case-Smith J. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of interventions used in occupational therapy early childhood services. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(4):379– 382.

4. Humphry R, Wakeford L. An occupation-centered discussion of development and implications for practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2006;60(3):258–267.

5. Burke JP. How Therapists' Conceptual Perspectives Influence Early Intervention Evaluations. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8(1):49–61.

6. Coster W. Occupation-centered assessment of children. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52(5):337–344.

7. Howe T-H, Kramer P, Hinojosa J. Developmental Perspective: Fundamentals of Developmental Theory. In: Kramer P, Hinojoas J, Howe T-H, editors. Frames of reference for pediatric occupational therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019. p. 20–28.

8. Colyvas JL, Sawyer LB, Campbell PH. Identifying strategies early intervention occupational therapists use to teach caregivers. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(5):776– 785.

9. Campbell HP, Chiarello JL, Wilcox JM, et al. Preparing Therapists as Effective Practitioners in Early Intervention. Infants Young Child. 2009;22(1):21–31.

10. Kingsley K, Mailloux Z. Evidence for the effectiveness of different service delivery models in early intervention services. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(4):431–436. 11. Thompson KM. Early intervention services in daily family life: mothers' perceptions

of ‘ideal’ versus ‘actual’ service provision. Occup Ther Int. 1998;5(3):206–221. 12. Fisher AG. Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: Same, same or

different? Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20(3):162–173.

13. Mathiowetz V. Role of physical performance component evaluations in occupational therapy functional assessment. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47(3):225–230.

14. Rodger S, Kennedy-Behr A. Occupation-centred practice with children: A practical guide for occupational therapists. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. 15. Adair B, Ullenhag A, Keen D, et al. The effect of interventions aimed at improving

participation outcomes for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Dev Med & Child Neurol. 2015;57(12):1093–1104.

16. Wright FV, Rosenbaum PL, Goldsmith CH, et al. How Do Changes in Body

Functions and Structures, Activity, and Participation Relate in Children with Cerebral Palsy? Dev Med & Child Neurol. 2008;50(4):283–289.

24

17. Humphry R. Young children's occupations: explicating the dynamics of developmental processes. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(2):171–179.

18. Kielhofner G. Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co.; 2009.

19. Rodger S, Kennedy-Behr A. Introduction to Occupation-Centred Practice for Children. In: Rodger S, Kennedy-Behr A, editors. Occupation-centred practice with children: a practical guide for occupational therapists. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. p. 1–20.

20. Dunford C, Bannigan K. Children and young people’s occupations, health and well being: a research manifesto for developing the evidence base. World Fed Occup Ther Bull. 2011;64(1):46–52.

21. Price P, Stephenson SM. Learning to promote occupational development through co‐ occupation. J Occup Sci. 2009;16(3):180–186.

22. Segal R. The Construction of Family Occupations: A Study of Families with Children Who Have Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Can J Occup Ther.

1998;65(5):286–292.

23. Lawlor MC. The significance of being occupied: the social construction of childhood occupations. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(4):424–434.

24. Pierce D. Maternal management of the home as a developmental play space for infants and toddlers. Am J Occup Ther. 2000;54(3):290–299.

25. Poskey G, Pizur-Barnekow K, Hersch G. Parents' response to infant crying:

Contributing factors of the reciprocal interaction. J Occup Sci. 2014;21(4):519–526.. 26. Pierce D. Co-occupation: The challenges of defining concepts original to occupational

science. J Occup Sci. 2009;16(3):203–207.

27. Pickens ND, Pizur-Barnekow K. Co-occupation: Extending the dialogue. J Occup Sci. 2009;16(3):151–156.

28. Gray JM. Putting occupation into practice: occupation as ends, occupation as means. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52(5):354.

29. Trombly CA. Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. 1995 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Am J Occup Ther.

1995;49(10):960.

30. Royeen CB. Chaotic Occupational Therapy: Collective Wisdom for a Complex Profession. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(6):609-624.

31. Polatajko H, Davis J. Advancing occupation-based practice: Interpreting the rhetoric. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79(5):259-62.

25

32. Che Daud AZ, Yau MK, Barnett F. A consensus definition of occupation-based intervention from a Malaysian perspective: A Delphi study. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(11):697–705.

33. Forsyth K, Mann LS, Kielhofner G. Scholarship of Practice: Making Occupation-Focused, Theory-Driven, Evidence-Based Practice a Reality. Br J Occup Ther. 2005;68(6):260-268.

34. Pierce D. Occupation by Design: Dimensions, Therapeutic Power, and Creative Process. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(3):249-259.

35. Yerxa EJ. Occupation: the keystone of a curriculum for a self-defined profession. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52(5):365.

36. Whiteford GE, Wilcock AA. Centralizing occupation in occupational therapy curricula: imperative of the new millennium. Occup Ther Int. 2001;8(2):81–85 37. Wong SR, Fisher G. Comparing and Using Occupation-Focused Models. Occup Ther

In Health Care. 2015;29(3):297–315.

38. Baum CM, Christiansen CH, Bass JD. The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) Model. In: Christiansen CH, Baum CM, Bass JD, editors. Occupational therapy: performance, participation and well-being. 4th ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2015. p. 49–55.

39. Christiansen C, Baum CM, Bass-Haugen J. Occupational therapy: performance, participation, and well-being. 3rd ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2005.

40. Dornelas LdF, Duarte NMdC, Magalhães LdC. Neuropsychomotor developmental delay: conceptual map, term definitions, uses and limitations. Revista paulista de pediatria: orgao oficial da Sociedade de Pediatria de Sao Paulo. 2015;33(1):88–103. 41. Molineux M. A dictionary of occupational science and occupational therapy. 1st ed:

Oxford: University Press; 2017.

42. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8(1):19–32.

43. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

44. Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, et al. Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst, 2008;6(1):7–19.

45. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015. p. 1-24.

46. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews

26

47. Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):579–589.

48. Eriksen M, Frandsen T. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(4):420–431.

49. AOTA. Occupational therapy practice: framework: domain & process, 3rd edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(SI):S1–S48.

50. Reed KL. Key Occupational Therapy Concepts in the

Person-Occupation-Environment-Performance Model. In: Christiansen C, Baum CM, Bass JD, editors. Occupational therapy: performance, participation and well-being. 4th ed. Thorofare (NJ).: Slack; 2015. p. 565–612.

51. Youngstrom MJ, Brown C. Categories and Principles of Intervention. In: Christiansen C, Baum CM, Bass-Haugen J, editors. Occupational therapy: performance,

participation, and well-being. 3rd ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2005. p. 398–419.

52. Lee J. Achieving Best Practice: A Review of Evidence Linked to Occupation-Focused Practice Models. Occup Ther In Health Care. 2010;24(3):206–222.

53. Whiteford G, Townsend E, Hocking C. Reflections on a Renaissance of Occupation. Can J Occup Ther 2000;67(1):61–69.

54.* Beetz A, Winkler N, Julius H, et al. A Comparison of Equine-Assisted Intervention and Conventional Play-Based Early Intervention for Mother-Child Dyads with Insecure Attachment. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2015;8(1):17–39.

55.* Fabrizi SE, Ito MA, Winston K. Effect of occupational therapy-led playgroups in early intervention on child playfulness and caregiver responsiveness: a repeated-measures design. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(2). doi:10.5014/ajot.2016.017012.

56. Stewart KB. Outcomes of Relationship-Based Early Intervention. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2008;1(3-4):199–205.

57. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

58. Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, et al. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1). doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633 59. WHO. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for

medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(4):373–374.

60. Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009.

61. Beauchamp TL. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2013.

27

62. Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2014.

63. Cocks AJ. The Ethical Maze: Finding an inclusive path towards gaining children’s agreement to research participation. Childhood. 2006;13(2):247–266.

64. Skivenes M, Strandbu A. A Child Perspective and Children's Participation. Child Youth Environ. 2006;16(2):10–27.

65. Thomas B, Tachble A, Peiris D, et al. Making literature reviews more ethical: a researcher and health sciences librarian collaborative process. Futur Sci OA. 2015;1(4). doi: 10.4155/fso.15.78

66. McDonagh M, Peterson K, Raina P, et al. AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care. Avoiding Bias in Selecting Studies. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and

Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008.

67. Vergnes J-N, Marchal-Sixou C, Nabet C, et al. Ethics in systematic reviews. J Med Eth. 2010;36(12):771–774.

68. Weingarten MA, Paul M, Leibovici L. Assessing ethics of trials in systematic reviews. BMJ. 2004;328(7446):1013–1014.

69. Pieper I, Thomson C. Justice in Human Research Ethics. Monash Bioeth Rev. 2013;31(1):99–116

70.* Barfoot J, Meredith P, Ziviani J, et al. Relationship-focused parenting intervention to support developmental outcomes for a young child with cerebral palsy: A practice application. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(10):640–643.

71.* de Brito Brandão M, Gordon AM, Cotta Mancini M. Functional Impact of Constraint Therapy and Bimanual Training in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(6):672–681.

72.* Demchick BB, Day KH. A Collaborative Naturalistic Service Delivery Program for Enhancing Pragmatic Language and Participation in Preschoolers. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2016;9(4):340–352.

73.* Dickerson AE, Brown LE. Pediatric constraint-induced movement therapy in a young child with minimal active arm movement. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61(5):563–573. 74.* Fabrizi SE. Splashing Our Way to Playfulness! An Aquatic Playgroup for Young

Children With Autism, A Repeated Measures Design. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2015;8(4):292–306.

75.* Fabrizi S, Hubbell K. The Role of Occupational Therapy in Promoting Playfulness, Parent Competence, and Social Participation in Early Childhood Playgroups: A Pretest Posttest Design. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2017;10(4):346–365.

76.* Lammi BM, Law M. The Effects of Family-Centred Functional Therapy on the Occupational Performance of Children with Cerebral Palsy. Can J Occup Ther. 2003;70(5):285–297.

28

77.* Law MC, Darrah J, Pollock N, et al. Focus on function: a cluster, randomized controlled trial comparing child- versus context-focused intervention for young children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(7):621–629.

78.* Price MP, Miner S. Mother becoming: learning to read Mikala's signs. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16(2):68–77.

79.* Ross SM, Catena M, Twardzik E, et al. Feasibility of a Modified Ride-on Car Intervention on Play Behaviors during an Inclusive Playgroup. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2018;38(5):493–509.

80.* Sood D, Szymanski M, Schranz C. Enriched Home Environment Program for

Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2015;8(1):40–55.

81.* Kruijsen-Terpstra AJA, Ketelaar M, Verschuren O, et al. Efficacy of three therapy approaches in preschool children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(7):758–766.

82.* Størvold GV, Jahnsen R. Intensive motor skills training program combining group and individual sessions for children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther.

2010;22(2):150–159.

83.* An S-JL. Parent Training Occupational Therapy Program for Parents of Children with Autism in Korea. Occup Ther Int. 2017. DOI:10.1155/2017/4741634

84.* Bastable K, Dada S, Uys CJE. The Effect of a Non-Powered, Self-Initiated Mobility Program on the Engagement of Young Children with Severe Mobility Limitations in the South African Context. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2016;36(3):272–291.

85.* An S-JL. Occupation‐Based Family‐Centered Therapy Approach for Young Children with Feeding Problems in South Korea; A Case Study. Occup Ther Int.

2014;21(1):33–41.

86.* Hwang AW, Chao MY, Liu SW. A randomized controlled trial of routines-based early intervention for children with or at risk for developmental delay [Article]. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(10):3112–3123.

87. Ketelaar M, Kruijsen A, Verschuren O, et al. LEARN 2 MOVE 2-3: a randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of child-focused intervention and context-focused intervention in preschool children with cerebral palsy. BMC Pediatrics.

2010;10(1):80–90.

88. WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health: children and youth version (ICF-CY). Geneva (Switzerland); 2007.

89. Price MP, Miner S. Mother becoming: Learning to read Mikala's signs. Mother becoming: Learning to read Mikala's signs. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16(2):68–77. 90. Nelson A, Copley J, Flanigan K, et al. Occupational therapists prefer combining

multiple intervention approaches for children with learning difficulties. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56(1):51–62.

91. Brown GT, Rodger S, Brown A, et al. A Profile of Canadian Pediatric Occupational Therapy Practice. Occup Ther Health Care. 2007;21(4):39–69.

29

92. Wilby HJ. The Importance of Maintaining a Focus on Performance Components in Occupational Therapy Practice. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70(3):129-132.

93. Weinstock-Zlotnick G, Hinojosa J. Bottom-up or top-down evaluation: is one better than the other? Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58(5):594.

94. Novak I, Honan I. Effectiveness of paediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12573

95. Schoen SA, Man S, Spiro C. A Sleep Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Open J Occup Ther. 2017;5(2).

doi:10.15453/2168-6408.1293

96. Sung V, Hiscock H, Sciberras E, et al. Sleep Problems in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Prevalence and the Effect on the Child and Family. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(4):336–342.

97. Hodge D, Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP, et al. Relationship between Children's Sleep and Mental Health in Mothers of Children with and without Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(4):956–963.

98. Doo S, Wing YK. Sleep problems of children with pervasive developmental disorders: correlation with parental stress. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(8):650–655.

99. Ho ECM, Siu AMH. Occupational Therapy Practice in Sleep Management: A Review of Conceptual Models and Research Evidence. Occup Ther Int. 2018.

doi: 10.1155/2018/8637498

100. Coster WJ. Embracing ambiguity: facing the challenge of measurement. (2008 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture). Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(6):743–752. 101. Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Masiello T. Exploratory Investigation of the Effects of

Interest-Based Learning on the Development of Young Children with Autism. Autism: Int J Res Pract. 2011;15(3):295–305.

102. Haley SM, Coster WJ, Ludlow LH, et al. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI): Development, Standardization and Administration Manual. Boston (MA): Boston University; 1992.

103. Verkerk GJ, Wolf MJM, Louwers AM, et al. The reproducibility and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in parents of children with disabilities. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(11):980–988.

104. Østensjø S, Øien I, Fallang B. Goal-oriented rehabilitation of preschoolers with cerebral palsy—a multi-case study of combined use of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and the Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS). Dev Neurorehabil. 2008;11(4):252–259.

30

105. Pollock N, Missiuna C, Jones J. Occupational Goal Setting with Children and Families. In: Rodger S, Kennedy-Behr A, editors. Occupation-centred practice with children: A practical guide for occupational therapists. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. p. 91–109.

106. Bamm EL, Rosenbaum P. Family-Centered Theory: Origins, Development, Barriers, and Supports to Implementation in Rehabilitation Medicine. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(8):1618–1624.

107. Hanna K, Rodger S. Towards family-centred practice in paediatric occupational therapy: A review of the literature on parent-therapist collaboration. Aust Occup Ther J. 2002;49(1), 14–24.

108. Cordier R, Chen Y-W, Speyer R, et al. Child-Report Measures of Occupational Performance: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147751

109. Harter S, Pike R. The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children. Child Dev. 1984;55(6):1969–1982..

110. Hinojosa J, Kramer P, Howe T-H. Pediatric Occupational Therapy's Contemporary Legitimate Tools. In: Kramer P, Hinojoas J, Howe T-H, editors. Frames of reference for pediatric occupational therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer

Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019. p. 49–66.

111. Brewer K, Pollock N, Wright FV. Addressing the Challenges of Collaborative Goal Setting with Children and Their Families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2014;34(2):138– 152.

112. Kramer J, Walker R, Cohn ES, et al. Striving for Shared Understandings: Therapists' Perspectives of the Benefits and Dilemmas of Using a Child Self-Assessment. OTJR: Occup Particip Health. 2012;32(1):S48–S58.

113. Degrace BW. Occupation-based and family-centered care: a challenge for current practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(3):347–350..

114. WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva (Switzerland); 2001.

115. Rosenbaum P, Gorter JW. The ‘F‐words’ in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think! Child: Care Health Dev. 2012;38(4):457–463.

116. Brochard S, Newman CJ. The need for innovation in participation in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(5):501–501..

117. Wilding C, Whiteford G. Occupation and occupational therapy: Knowledge paradigms and everyday practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54(3):185–193.

118. Aiken FE, Fourt AM, Cheng IKS, et al. The Meaning Gap in Occupational Therapy: Finding Meaning in our Own Occupation. Can J Occup Ther. 2011;78(5):294–302 119. Gillen A, Greber C. Occupation-Focused Practice: Challenges and Choices. Br J

31

120. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348. doi:10.1136/bmj.g168

121. Forssén A, Meland E, Hetlevik I, et al. Rethinking scientific responsibility. J Med Eth. 2011;37(5):299–302.

122. Chen D-Tv, Wang Y-M, Lee WC. Challenges confronting beginning researchers in conducting literature reviews. Stud Contin Educ. 2015;38(1):47–60.

123. Bulkeley K, Bundy A, Roberts J, et al. Family-Centered Management of Sensory Challenges of Children With Autism: Single-Case Experimental Design. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(5):1-8.

124. Magiati I, Moss J, Charman T, et al. Patterns of change in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who received community based comprehensive interventions in their pre-school years: A seven year follow-up study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(3):1016-1027.

125. Ahl LE, Johansson E, Granat T, et al. Functional therapy for children with cerebral palsy: an ecological approach. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2005;47(9):613-619.

126. Carlson G, Armitstead C, Rodger S, et al. Parents' Experiences of the Provision of Community-Based Family Support and Therapy Services Utilizing the Strengths Approach and Natural Learning Environments. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2010;23(6):560-572.

127. Fernell E, Hedvall A, Westerlund J, et al. Early Intervention in 208 Swedish Preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. A Prospective Naturalistic Study. Research in Developmental Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal.

2011;32(6):2092-2101.

128. Blanche EI, Chang MC, Gutiérrez J, et al. Effectiveness of a Sensory-Enriched Early Intervention Group Program for Children With Developmental Disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(5):7005220010p1.

129. Darrah J, Law MC, Pollock N, et al. Context Therapy: A New Intervention Approach for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(7):615-620. 130. Darrah J, Law M, Pollock N. Family-Centered Functional Therapy—A Choice for

Children with Motor Dysfunction. Infants Young Child. 2001;13(4):79-87. 131. Casey J, Paleg G, Livingstone R. Facilitating Child Participation through Power

Mobility. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(3):158-160.

132. Watling RL, Dietz J. Immediate effect of Ayres’s sensory integration–based

occupational therapy intervention on children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61(5):574-583.

133. Case-Smith J, Bryan T. The effects of occupational therapy with sensory integration emphasis on preschool-age children with autism. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(5):489.

32

134. Linderman TM, Stewart KB. Sensory integrative-based occupational therapy and functional outcomes in young children with pervasive developmental disorders: a single-subject study. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(2):207.

33

Figure 1: Core concepts of the PEOP model - adapted from Baum et al. [38]

P A R T IC IP A T IO N P E R F O R MA N C E WE L L -B E IN G Cognition Psychological Physiological Sensory Motor Spirituality PERSON OCCUPATION Activities Tasks Roles Assistive Technology ENVIRON MENT Culture Social determinants Social Support Social Capital Education and Policy

Physical and Natural

34

35 Publication Year 1999-2004 2005-2009 2010-2014 2015-2019 n= 1 2 5 11 Age of participants 0-1;11 2;0-3;11 4;0-5;11 n= 10 16 9 Intervention features Occupation-based Occupation-focused Both OB and OF n= 8 2 9 Country Australia Canada Germany Netherlands Norway South Africa South Korea Taiwan USA n= 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 9 Sample Sizes < 10 10-49 50-100 > 100 Participants across all studies (age range 0-5) n= 10 8 1 1 n= 366 Outcomes ADL

Sleep and Rest Play Leisure Social Participation/ Social Interaction n= 9 0 12 3 8 Study design Randomized-Control trial Two-group pre/post One-group pre/post Single subject

Case study/case report Qualitative Mixed methods n= 5 0 4 7 3 1 2 Practice Setting Home Community Preschool Clinic Group Individual Mixed n= 5 6 1 9 5 12 2 Measures used Standardized measures PEDI COPM GAS PACS ACPC ToP Observation/Narrative Task/Performance analysis n= 10 6 5 4 1 1 3 3 0

ADL = Activities of daily living; ACPC = Assessment of Preschool Children’s Participation; COPM = Canadian

Occupational Performance Measure; GAS = Goal Attainment Scaling; OB = occupation-based; OF = occupation-focused; PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory; PACS = Preschool Activity Card Sort; ToP = Test of Playfulness

36

Table 1: Search words based on the PICO-model

Population Intervention Control Outcome

Infants and young children with developmental delay Occupation-based or occupation-focused interventions Pre-Post Occupational performance Pediatric Paediatric Child Toddler Infant Neonate AND disability delay special needs AND Occupation-based Occupation-centred Occupation-focused Activity-based Activity-focused Task-based Task-focused Participation-based Context-focused AND Intervention Therapy Practice Program Treatment Early Intervention Rehabilitation AND Occupational performance Participation Activities of daily living/ADL Self-care Sleep Play Leisure Social interaction Co-occupation

37

Table 2: Thematic synthesis of occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions with

the most widely used outcome measures

Author, year Occupation-based Occupation-focused COPM PEDI

An, 2014 [85]

An, 2017 [83]

Barfoot, Meredith, Ziviani, & Whittingham, 2015 [70]

Bastable, Dada, & Uys, 2016 [84]

de Brito Brandão, Gordon, & Cotta Mancini, 2012 [71]

Demchick & Day, 2016 [72]

Dickerson & Brown, 2007 [73]

Fabrizi & Hubbell, 2017 [75]

Fabrizi, Ito, & Winston, 2016 [55]

Fabrizi, 2015 [74]

Hwang, Chao, & Liu, 2013 [86]

Lammi & Law, 2003 [76]

Law et al., 2011 [77]

Price & Miner, 2009 [78]

Ross et al., 2018 [79]

Sood, Szymanski, & Schranz, 2015 [80]

Størvold & Jahnsen, 2010 [82]

Kruijsen-Terpstra et al., 2016* [81]

Beetz, Winkler, Julius, Unväs-Moberg, & Kotrschal, 2015** [54]

by title by abstract

05-03-2019

CINAHL Pediatric OR Paediatric OR Child* OR Toddler OR Infan* OR Neonat* AND disability OR delay OR special needs AND Occupation-based OR centred OR

Occupation-focused OR based OR Activity-focused OR Task-based OR Task-Activity-focused OR Participation-based OR Context-focused AND Intervention OR Therapy OR Practice OR Program OR Treatment OR Early Intervention OR Service OR Rehabilitation AND

Occupational performance OR Participation OR Activities of daily living OR ADL OR Self-care OR Sleep OR Play OR Leisure OR Social interaction OR co-occupation English, Boolean/phrase, 1999-2019, Research article 28 14 4 Kruijsen-Terpstra et al., 2016 [81] Law et al., 2011 [77] 05-03-2019

CINAHL (MH "Pediatric Occupational Therapy/MT") English, 1999-2019, Research article 142 54 25 De Brito Brandão et al., 2012 [71] Dickerson, 2007 [73] Kruijsen-Terpstra et al., 2016 [81] Law et al., 2011 [77]

39 Størvold and Jahnsen, 2010 [82] 05-03-2019

AMED Pediatric OR Paediatric OR Child* OR Toddler OR Infan* OR Neonat* AND disability OR delay OR special needs AND Occupation-based OR centred OR

Occupation-focused OR based OR Activity-focused OR Task-based OR Task-Activity-focused OR Participation-based OR Context-focused AND Intervention OR Therapy OR Practice OR Program OR Treatment OR Early Intervention OR Service OR Rehabilitation AND

Occupational performance OR Participation OR Activities of daily living OR ADL OR Self-care OR Sleep OR Play OR Leisure OR Social interaction

Boolean/phrase, search all text, English, 1999-2019

8 3 1 -

05-03-2019

ERIC Pediatric OR Paediatric OR Child* OR Toddler OR Infan* OR Neonat* AND disability OR delay OR special needs AND Occupation-based OR centred OR

Occupation-focused OR based OR Activity-focused OR Task-based OR Task-Activity-focused OR Participation-based OR Context-focused AND Intervention OR Therapy OR Practice OR Program OR Treatment OR Early Intervention OR Service OR Rehabilitation AND

Occupational performance OR Participation OR Activities of daily living OR ADL OR Self-care OR Sleep OR Play OR Leisure OR Social interaction OR co-occupation Boolean/phrase, English, 1999-2019 21 9 1 - 05-03-2019

ERIC (DE "Occupational Therapy") AND (DE "Early Intervention" OR DE "Developmental Delays")

English, 1999-2019 53 17 2 Demchick and

40

Fabrizi et al., 2017 [75]

05-03-2019

MEDLINE Pediatric OR Paediatric OR Child* OR Toddler OR Infan* OR Neonat* AND disability OR delay OR special needs AND Occupation-based OR centred OR

Occupation-focused OR based OR Activity-focused OR Task-based OR Task-Activity-focused OR Participation-based OR Context-focused AND Intervention OR Therapy OR Practice OR Program OR Treatment OR Early Intervention OR Service OR Rehabilitation AND

Occupational performance OR Participation OR Activities of daily living OR ADL OR Self-care OR Sleep OR Play OR Leisure OR Social interaction Boolean/phrase, English, 1999-2019 39 12 7 Kruijsen-Terpstra et al., 2016 [81] Law et al., 2011 [77] 05-03-2019

MEDLINE (MH "Occupational Therapy/MT") AND (MH "Pediatrics")

English, 1999-2019 23 3 0 -

05-03-2019

PsychInfo Pediatric OR Paediatric OR Child* OR Toddler OR Infan* OR Neonat* AND disability OR delay OR special needs AND Occupation-based OR centred OR

Occupation-focused OR based OR Activity-focused OR Task-based OR Task-Activity-focused OR Participation-based OR Context-focused AND Intervention OR Therapy OR Practice OR Program OR Treatment OR Early Intervention OR Service OR Rehabilitation AND

Occupational performance OR Participation OR Activities of daily living OR ADL OR Self-care OR Sleep OR Play OR Leisure OR Social interaction OR co-occupation English, 1999-2019 45 13 3 Kruijsen-Terpstra et al., 2016 [81] Law et al., 2011 [77]

![Figure 1: Core concepts of the PEOP model - adapted from Baum et al. [38]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4649502.120766/33.893.101.791.130.462/figure-core-concepts-peop-model-adapted-baum-et.webp)