Malmö University

School of Teacher Education

KSM: English

Dissertation

10 credits

‘Marks’ or ‘grades’?

– an investigation concerning attitudes towards British English

and American English among students and teachers in three Swedish

upper-secondary schools

Jimmy Sjöstedt Monika Vranic

Bachelor in Teaching, 200 credits Modern Languages - English Final Seminar: 2007-05-31

Examiner: Björn Sundmark Supervisor: Stefan Early

Abstract

English is today a vast world language, and the foremost important business and cross-border language in the world. The two predominant English varieties in the Swedish educational system are British English and American English. A third variety, Mid-Atlantic English, is however on the up-rise, and many researchers expect this to be the future educational standard variety due to escalating globalization. British English is the variety which traditionally has been taught in the Swedish school, but the last couple of decades American English have been gaining ground because of popular media. Today both varieties are referred to in the Swedish National Curriculum, and teachers as well as students face a multifaceted choice. The aim of this paper is to investigate attitudes among upper-secondary level teachers and students; on what grounds they have chosen their personal variety and to what extent they are aware of what English variety they use. What we have seen is that resolute attitudes can be perceived towards the two Englishes. Furthermore, our investigation shows that students mix British and American English, and even though British English still is held in academic esteem, American English characteristics predominate in the mix. British English is recurrently described as “snobbish” and in a more positive fashion as “high-class”, whereas American English is perceived either as “youthful and cool” or “dim and uneducated”. Even students who prefer and think they use British English, to a large extent use American orthography and spelling.

Keywords: British English, BrE, American English, AmE, Mid-Atlantic English, attitudes, MAE, EuroEnglish, upper secondary school, English as a second language, ESL, English as a foreign language, EFL

Content

1. Introduction 7

1.1 Purpose and aim 7

1.2 Definitions and terms 8

2. Background and theory 8

2.1 British English 8

2.2 American English 10

2.3 Mid-Atlantic English 11

3. Method 12

3.1 Presentation of investigated upper-secondary schools 12

3.2 Informants 13

3.3 Material 14

4. Results 14

4.1 Attitudes among teachers 14

4.1.1 School A – the male teacher [34 years old] 15 4.1.2 School A – the female teacher [47 years old] 16 4.1.3 School B – the female teacher [32 years old] 18 4.1.4 School B – the male teacher [49 years old] 19

4.1.5 School C – female teacher [35 years old] 21

4.2 Attitudes among students 22

4.2.1 School A 23

4.2.2 School B 25

4.2.3 School C 26

5. Analysis and discussion 27

6. Conclusion 31

1. Introduction

Without doubt English is today a vast world language, and from a global point of view, the foremost important business and cross-border language in the world. There are hundreds of millions of people who speak English either as their first or second language, and in Sweden English is one of four core subjects in the National Curriculum.

Even though, hypothetically there are a number of major English varieties to choose from, British English has been predominant in the Swedish educational system for the last forty years. It has in other words been more or less the sole variety taught for as long as English has been a required language in Sweden. Today this is not true anymore. The American English influences us greatly due to the immense amount of media from North America. As a consequence of this American media flow, British English lost its exclusive position as the only variety taught in Sweden when the new National Curriculum (Lpf94) was introduced in 1994 , and teachers as well as students were thereby left with the choice of either a British English variety or an American English variety.

It is this choice we, as soon to be teachers at upper-secondary level English, want to dissect and analyze: what does it mean to have two predominant varieties that are taught in the Swedish school system, and more importantly what feelings are concerned in the choice of either variety. Is the British variety still the variety with the most academic prestige among students, or is the American variety gradually taking over? And how is this handled in the classroom, both from a teacher and from a student perspective?

1.1 Purpose and aim

Our aim with this dissertation is to investigate the attitudes among upper-secondary level teachers and students towards the two predominant varieties in the Swedish school system, namely British English and American English. And the purpose is to describe and analyze the attitudes in order to stand better equipped ourselves to handle this in our own teaching. We intend to investigate and further discuss following questions:

- What are the attitudes among teachers concerning teaching British English and American English, and on what grounds have they themselves chosen their personal variety?

- To what extent are students aware of the English variety they use, and what are the attitudes towards these two varieties?

1.2 Definitions and terms

In this essay we will talk about American English and British English, when referring to what often is perceived as the standard varieties, General American and Received Pronunciation, on each continent. When dealing with the teacher interviews and the student questionnaire there are occasions when our interviewees refer to different kind of dialects within these two major varieties. This also makes up part of our investigation, namely to see to what extent they are aware of the different varieties. To limit this essay, and to use the same terms as most of the experts we cite in this essay do, we have chosen to use British English as a collective term for all the British Englishes, and American English for all the American variations. An overwhelming majority of the students and the teachers unimpededly referred to these collective terms, which further convinced us of the naturalness of this decision. As a matter of fact, it is only on a few occasions in this dissertation we have seen us constrained to describe more distinguished attitudes in the light of either British Englishes or American Englishes.

Another essential differentiation is between the terms dialect and accent. As we have seen, many students use these two terms equally, which sometimes makes it difficult to determine if they refer to only the pronunciation, or pronunciation as well as lexical and linguistic variations. In line with Melchers & Shaw’s definitions of the two terms (2003:10–21), we define accent as only concerning the spoken part – the pronunciation – of the language, whereas dialect deals with additional levels of the language, pronunciation as well as lexical and grammatical variations.

2. Background and theory

Besides the two predominant varieties in Sweden today, British English and American English, there is a third variety on the up-rise – Mid-Atlantic English. In this chapter we aim to further present and define these three varieties.

2.1 British English

Many people outside the United Kingdom regard Received Pronunciation (RP) as “the British accent”. Received stands for “socially accepted” and was earlier considered to be better than other accents and referred to as the King’s (or Queen’s) English (Rönnerdal & Johansson, 2005:12). In spite of the fact that RP developed in the south-east of England it is geographically unbounded; it is a social variant which is predominately used by the upper-class. Not only in Britain, but also throughout the world, RP is by many considered to be

the most prestigious pronunciation: “The prestige of British English is probably due partly to its long history, to the influence of the former British empire and to its many unrivalled authors” (Odenstedt, 2000:137). However, it is only spoken by as little as three per cent of the population of Britain (Modiano, 1996:11).

Nevertheless, nowadays the tolerance to different accents is greater than in the past. Although the stereotypes about RP continue, other accents have been accepted and are frequently heard. In the south-east there are notably different accents; the local inner east London accent called Cockney is conspicuously different from RP and can be difficult to understand for outsiders. There is also a new form of accent called Estuary English that has become more prominent in the latest decades; it has some characteristics of RP and some of Cockney. The broad local accent in London is still changing and it is to a degree influenced by Caribbean speech. Depending on class, age and upbringing, London citizens speak with a mixture of these accents (Nationalencyklopedin 1991:5,507).

The mass immigration to Northamptonshire in the 1940s and its close accent borders has become a source to various accent developments. Today, you can hear an accent which is locally known as the Kettering accent; it is a mixture of many different local accents, including East Midlands, East Anglian, Scottish and Cockney. Further up to the north, you can find Corbyite which is largely based on Scottish. Some of the stronger regional accents can sometimes be difficult to understand for some English speakers from outside Great Britain, even though almost all British accents are equally comprehensible amongst the British people themselves (Nationalencyklopedin 1991:5, 508).

According to Rönnerdal & Johansson (2005:12), a model for pronunciation teaching should consist of certain elements. The form of English should not be regionally or socially limited and the pronunciation model should be easy to understand in most situations. It should also represent a variety that people come across i.e. when traveling and in media. Furthermore, an additional consideration is the teaching material that is available. Traditionally, RP has been used as a model since it suits all of these requirements and it is still being taught to English second learners in most European schools.

Today in Sweden the overt prestige (Aithchison 2001:83) of British English – the open prestige in which BrE is associated with academic and social status – can be said to be on the decrease within certain social groups and cultures. Marko Modiano, a researcher and professor in social linguistics argues that “BrE appears to be the domain of a highly cultured people, whereas AmE is less sophisticated and more reminiscent of rural dwellers” (Modiano 1996:134). In other words, factors as education, heritage and social status are

important measures to conclude if, in this case, British English corresponds to your identity image.

2.2 American English

Colonists from England, who settled along the Atlantic seaboard in the 17th century, brought the English language to America. British colonists established the speech and forms of English in America after they had won the war against France in the 18th century. When the first wave of immigrants came to the country from the British Isles, American English developed even more (Nationalencyklopedin 1991:5, 507–508)). The various American English accents are a result of a mixture of different accents from the British Isles (Baugh, 2002:356). While there are numerous recognizable variations in the spoken language, concerning both pronunciation and vernacular, written American English is standardized across the country. Any American accent that is relatively free of obvious regional influences is named General American. American pronunciation varies less than that of British English and it is not a standard accent in the way that RP is in Great Britain (Melchers&Shaw 2003:82).

Even though no longer region-specific, African American Vernacular English remains widespread amongst African Americans (Melchers&Shaw 2003:84). It has close relationship to Southern varieties of American English and to a large extent influenced everyday speech of many Americans. The Inland North dialect is centered on the Great Lakes region and it was the basis for General American in the mid-20th century. Midland speech begins west of the Appalachian Mountains and the North Midland speech continues to expand westward and eventually becomes a similar Western dialect which consists of Pacific Northwest English and the well-known California English. Mormon and Mexican settlers in the west have influenced evolvement of Utah English, so-called Chicano English (Melchers&Shaw 2003:84–85). The South Midland, which is spoken in Ohio River, Arkansas and Oklahoma, is a version of the Midland speech that is influenced by coastal Southern forms. Hawaii has a distinctive Hawaiian Pidgin. Furthermore, the dialect development in the United States has been particularly influenced by the characteristic speech of important cultural centers as Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, Charleston, New Orleans and Detroit, which inflicted their marks on the neighboring areas (Melchers & Shaw 2003:81–84).

More than two thirds of the native speakers of the English language speak some form of American English. Most of the varieties of pronunciation in the United States are found on

the east coast. They are often spoken by small groups such as the former French speaking population in Louisiana and other parts of the South. Contrasting the situation of RP “the establishment of AmE […] has not been based on prestige, educational snobbishness, or any conscious effort to promote a national standard. Instead, it has evolved naturally” (Modiano, 1996:10). In other words, American English can instead be said to uphold a covert prestige (Aitchison 2001:83) - a closed and less patent variety with other more vernacular associations than British English.

2.3 Mid-Atlantic English

Mid-Atlantic English is defined as “something which has both British and American characteristics, or is designed to appeal to both the British and the Americans” (Melchers, 1998:263). Even though American English has through the years, developed to become a world language, it is still not a matter of course that American English has the best references for actually becoming a lingua franca. Modiano argues that Mid-Atlantic English rather is the strongest candidate (1996:135). His argument is based on the clarity and ease of communication that this variety provides which is essential in a cross-cultural environment. Today, the majority of speakers in Western Europe use characteristics from both British Englishes and American Englishes. According to Modiano, students are beginning to speak Mid-Atlantic English since they tend to prefer forms and expressions that are most suitable for their communicative needs (Modiano 1998:242–244). Moreover, he states that it not exclusively second language learners who tend to mix English varieties, but the number of native speakers who are mixing characteristics of British and American English is also increasing. This results in L2 students, often being confused when confronted with their mistakes in the usage of British or American English. However, just like their students, even teachers sometimes find it difficult to separate the two varieties: “Beyond the classroom experience, it is evident that a separation of the two major varieties of the language […]is becoming increasingly difficult” (Modiano 1998:242). Although the National Curriculums for the English language in most European countries still emphasize that students should speak either a British or an American variety of English, an investigation of teachers’ attitudes to varieties of English, shows that many Swedish teachers have started to use and accept Mid-Atlantic English (Melchers, 1998:236–266). Modiano argues that this progress of MAE not only is inevitable but something positive since it is a variety “which allows for cultural pluralism” and which is “a politically and socially neutral lingua franca” (Modiano 1998: 243).

3. Method

In our investigation we use both a quantitative and a qualitative method. The attitudes among students, we concluded, would be easier to present to a certain degree in statistics, as we thought handling that many students qualitatively would exceed the limits of this research. The teachers’ opinions are more interesting, and in a research like this more feasible to handle in a qualitative matter. To allow us to make conclusions between teacher interviews and student questionnaires, we wrote the questionnaire so that four questions were open-ended. The questionnaire is in other words constructed in a qualitative tradition, and thereby it ought to be eligible to compare our results.

3.1 Presentation of investigated upper-secondary schools

The target groups for our investigations are students and their teachers in Swedish upper-secondary schools. We realized our investigations on three different schools, School A in a southern university town, School B and School C in a southern city. Since we aim for our research to be as wide and authentic as possible, we have chosen different types of schools. Besides offering different study programs, the differences in student and teacher mentality, study climate, student motivation, level of English knowledge are also apparent.

School A is a public school with a long tradition of theoretical studies in the heart of the university town, and is known for its high academic achievement and good results. The educational programs that are offered are the Arts Program, the Construction Program, and the Natural Science and Social Science Program. The students who attend School A are to large extent highly-motivated native Swedish students.

School B is also a public school that focuses on vocational programs as the Health Care Program, the Health Program, the Child and Recreation Program and finally the Individual Program. The school has a large majority of female students and of these a big majority is first and second generation immigrants. The teachers in the theoretical subjects are up against unmotivated students with vast problems with the Swedish language, which in turn also affects all language teaching. As a total there are 350 students attending the school. School C is a minor private school that offers three different programs: the Natural Science Program, the Social Science Program and the Electricity Program. The school is interesting not only while it is not a community school, but also because of the diversity of students: the students studying to become electricians are mostly unmotivated male students – in other words, the exact opposite of the female majority of School B – in the other programs we find highly motivated theoretical students, all within the walls of this

fairly small school of approximately 200 students. Furthermore, the teaching is thematic and most school work is done on lap-tops provided by the school.

3.2 Informants

Our investigation consists as mentioned before of questionnaires with six different student groups and of five interviews with English teachers – both students and teachers are at the upper-secondary schools described above.

The students are from all the three upper-secondary years – what year they are in is however nothing we have set up as a variable in the investigation. In order to restrict our research to a ten weeks dissertation we have limited our variables to: course, school and native language (see appendix 1). The students are between the ages of sixteen and eighteen years old, and the total number of students questioned is a hundred and twelve [112]. They are studying on various programs: Natural Science, Social Science, Health Care and Electricity. In other words, both theoretical students and practical students are covered. The interviews with the teachers were carried out with the support of open-ended questions (see appendix 2), with the intention to reach an authentic conversation. It was our intention to make sure we got an age distribution among the teachers interviewed to be able to make conclusions based on generation. With the event at hand, it proved difficult to find a wider range of age-spread than from 32 to 49 years. Considering this we feel we managed to spread the age distribution well according to gender, school and variety spoken, and ended up with: a male teacher at Spyken who is 34 years old and speaks British English, a female teacher - 47 years old- declaring herself to Mid-Atlantic English. At School B we interviewed a female teacher who is 32 years old and defines her English as American English, and a male teacher on the same school who is 49 years old and speaks British English. At the last school we only interviewed one teacher since we decided five interviewees were sufficient for our investigation.(Another as good reason, would be that the English teachers at School C proved all to be women of fairly same age, and all of them speak more or less the same variety). The female teacher at School C is 32 years old and relates to a somewhat blended British English.

3.3 Material

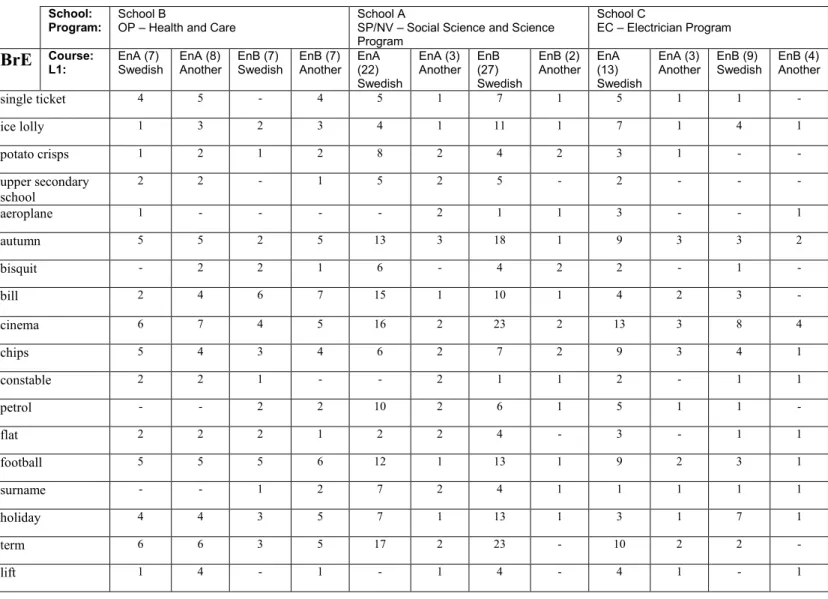

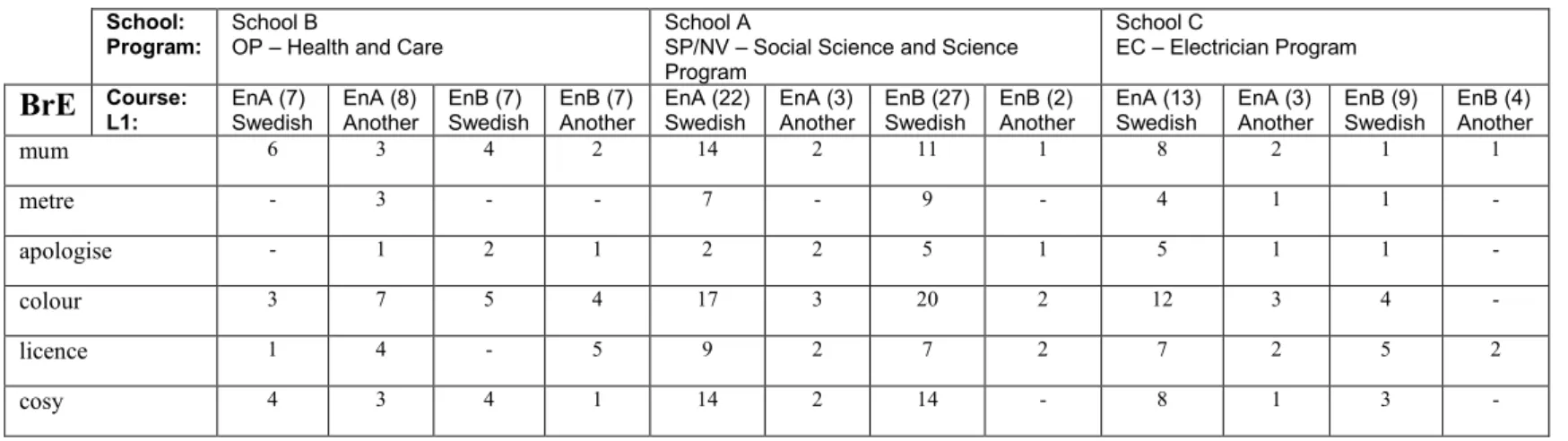

To be able to determine which variety students use and what their attitudes to the two major (collective) varieties are, we have chosen to formulate two-paged-questionnaires (see

appendix 2–5). In these questionnaires, we ask the students what variety they speak, what variety they prefer and what or who has had influence on their English dialect. We also constructed a wordlist in order to determine which variety students use. The wordlist consists of eighteen words, where each word exemplifies one of the varieties we are investigating. In addition to this wordlist, six words with the same meaning, but different spelling in British English and American English, were also presented. The intention was to find out if students actually use the variety that they think they use. Moreover, the questions were formulated with the purpose of finding out what attitudes students have towards British and American English. We chose to write questionnaires in both Swedish and English as we found it necessary in some of the classes in order to get the most out of the questionnaire. Time limitation was also a consideration.

Concerning the investigation among teachers, we chose to interview them individually. We formulated an interview guide with open-ended questions about their attitudes towards British and American English. During the interviews we also allowed room for possible further opinions and reflections, and we encouraged the teachers to come with their own views. Each interview lasted approximately forty minutes and was carried out in a quiet place. Since both of us are used to interviewing people without any recording device, we decided not to use tape recorders, but to make notes. As to this, we also took into consideration the factor of uneasiness that recording may cause. Worth noticing is that all the direct quotations are written down word by word to minimize miscommunications.

4. Results

The results of our interviews and student questionnaires are presented together with comments and in correlation to each other. In this essay, to make it more clear and understandable, we present teacher results and student results separately.

4.1 Attitudes among teachers

Some of the teachers preferred to refer to British Englishes and American Englishes as we do in this investigation, namely as two collective varieties: British English and American English. Whereas two of the teachers questioned the openness of our interview-guide and wondered which of the many British and American varieties we referred to. Since our questions primarily were thought as guidelines for the interview we asked them to share their thoughts and to use the terms and definitions they found suitable.

4.1.1 School A – the male teacher

The male teacher [34 years old] whom we interviewed at School A, highlights the importance of being open-minded and keeping up to date with the relationship between American English and British English. Languages are “alive” and they influence each other constantly, especially in this international world of today.

The teacher himself prefers British English. On two occasions he has lived in the south east of England during five months. Due to this he speaks one variety of British Englishes, specifically Estuary English. Besides that he finds British Englishes sound more beautiful, “cooler” and purely better then American Englishes; he is interested in British popular culture and likes British humor.

He teaches both English A and English B on the Social Science Program, the Natural Science Program and the Arts Program. Since speaking it himself and feeling most comfortable with one of the British dialects, he uses the British variety in his teaching. He explains the increase of influence of American English on British English, and that American strains in British English are clearly noticeable both in vocabulary and spelling. For example, the American “Z” is dominating in written British English, i.e. cozy (AmE) comparing to cosy (BrE). Occasionally, when teaching, he explains differences between the two collective varieties. He believes it is important to be consistent when writing a text and to stick to either British or American spelling, but he does not think it is a problem if one student uses British spelling rules when writing one text, and American when writing another text. Moreover, in speech it is perfectly fine that students combine British and American Englishes, especially if you regard the circumstances in the surrounding world – American Englishes are influencing British Englishes to an immense extent. Even in Sweden, the American Englishes is becoming more accepted after many years of the dominance of British Englishes. He also implies that when speaking a foreign language, you play with your voice a bit and take different characters and roles. For that sake and also because the differences between British and American English are not that clear any longer, it is acceptable to mix. It should also be considered that the ones, who have not spent a longer period of time in an English speaking country, have a pretty hard time choosing a dialect or English variety. It is important to keep up with the development of the society. The teacher tells us about a relatively new term, Euroenglish, that he has heard of on a seminar during one in-company training day. It is a European variety of the English language which is more influenced by American English than British English. It is probably due to the fact that the USA is having a bigger effect on our society and reaches out to a

larger amount of people. Euroenglish is a new variety, a new type of English. “Maybe we will use it in the teaching one day”, the teacher says.

The teacher tells us, that one British dialect is considered to be prestigious and have a very high status – Received Pronunciation (RP); even though only two percent of the British population actually speaks this dialect. Moreover, the dialect that is spoken among intellectual people in New York is regarded as a dialect that belongs to a higher status. However, Southern Drawl, which is one of American Englishes’ dialects, and Scottish dialect in Great Britain, are considered as low-status-dialects. The teacher personally thinks that RP sounds a bit too “posh”. He finds that Estuary English is beautiful, but also a certain New York dialect, the one that is not that broad. He is of the opinion that English teachers in Sweden should not speak a certain dialect. He or she should instead strive to equalize his or her dialect. Besides British Englishes and American Englishes, varieties such as Canadian Englishes or Indian Englishes are acceptable.

The teacher finally describes some dialects of British English; he finds RP sound snobbish with a negative ring, though it sounds fine if it is more neutral regarding social status, but not the “Tony-Blair- RP”.

American English, he describes as “bleating”, and then especially Vernacular English and youth language, though it depends on what dialect is considered.

4.1.2 School A – the female teacher

The female teacher [47 years old] whom we interviewed is of the opinion that language primarily is a tool intended for communication. It is less relevant which variety is used in teaching as long as it is Standard English, in other words – any variety. She thinks it is much more important for students to use a refined language than the actual variety they use. However, once a student has reached a level of high proficiency, he or she can focus more on the preferable English variety. The female teacher stresses though that the more you learn about the English language, the less significant becomes the variety you use. It is also important to be “aware of the growing influence that American Englishes have on British Englishes”. Referring to this fact, it is not interesting to strictly focus on teaching one specific variety. “It is slightly absurd”, the teacher explains. However, it is essential to bear in mind the needs and interests of the individual student. The differences between English varieties should function as stimulant and urge in language learning.

The teacher herself speaks some kind of Mid-Atlantic variety. It varies depending on the environment she is in. Originally she spoke Canadian English after spending a longer

period of time in Toronto. After her university studies in Great Britain, her Canadian English got influenced by British English, which she thinks is completely natural especially since not being a native speaker of English. “The environment forms your English”, she says. Even though her own English is influenced by several varieties, she usually supports her students to “choose one certain variety and stick to it”. She has noticed that a majority of the students speak and write in an American English variety.

Even though only few colleagues of hers genuinely grant this issue a greater attention, many teachers, according to our informant, find British English “nicer”. But the choice of English is more related to the teacher’s personality and experience. Some teachers are trying to teach Received Pronunciation. She thinks that it is important to be aware of using proper and eligible English in the classroom, so called “Classroom’s English”. Although it today is more accepted to speak different English varieties, there are still people who put down too much effort and time on mastering a certain variety.

In general, she believes, teachers tend to find British English more prestigious than American English: particularly Oxbridge and so called, BBC English. The students, on the other hand, prefer American English, often the variety of so-called Black English.

Our informant also concludes that there has been a change in the society regarding the English language; the “Working class English” in Great Britain has developed in a positive way. It is not as “corrupt as Aristocratic English” and it “is more housebroken thanks to Tony Blair”. The teacher also highlights the significance of creating a natural language environment in the classroom, to the utmost possible extent. The Swedish youth should speak as the youth speak within the English culture, either American or British, as long it is the standard variety.

Concerning mixing British and American Englishes, the teacher thinks it is very important to be consistent in written language and she does remark if a student blends different English varieties. She does not accept swearwords at all. However, she appreciates very much if a student has the ability to acquire and use idiomatic expressions. “That brings the natural touch to the language”, she explains. In speech, it is not relevant to comment if a student mixes different varieties. Quite the contrary, she thinks it is good to let students experiment and try out various language varieties in order to become comfortable with speaking English even outside the classroom environment.

The teacher finds it hard to describe British English, due to the many different sub-varieties [British English dialects]. Although, she portrays Standard British English as “intellectual with fun diphthongs and associates it to Hugh Grant – as being emotionally

unintelligent and giving a conservative impression”. Estuary English is youthful and humorous. She also finds British Englishes very social since there are hundreds of verbal expressions to use to approach someone.

American English has a boring intonation and does not consist of as many diphthongs as British English. The American varieties are more of a “way of being” and they are not labeling different social groups to the same extent as British Englishes. Moreover, American English is more suitable for Swedes since there is more “feeling” in this variety. Finally, the teacher points out this particular issue, as a problem existing only in industrialized countries as Sweden.

4.1.3 School B – the female teacher

The female teacher [32 years old] at School B considers the variety used in school as not as important today as it was only twenty years ago. Personally she has preferences, which is naturally her own dialect namely American English. She points out that there are never any remarks from her as a teacher on the varieties the students use. The teacher solely comments the students’ language when there are uncertainties regarding their language skills. Her experience is, however, that this has less to do with geographic variety differences. Instead it is closer related with more general orthography and structure.

Meanwhile, concluding that, in today’s classrooms, it is less important what variety is used, she still acknowledges there is a constant valuation of the English variety people use. This has led her to believe the students would benefit from trying to keep to one variety. On the other hand, this desirable consistency among the students is something she hardly ever experiences in her own teaching, nor does she think this is important to teach in the two first English courses, A-course and B-course.

In the lessons our informant often gives examples based merely on her own American variety. And when a British English example text or vocal recording comes up she admits that this is often something that she feels is pretentious and often makes fun of. This is something that she is aware of potentially will tinge the English of the students in favor for American Englishes. She also argues that the students themselves generally speaking have a more positive attitude towards American English than British English. The reason is that the type of students who choose to study a vocationally-oriented program regard the American English varieties to be easier to comprehend. She believes British English is more class-bound than American English – American English is less theoretical and has “a more colloquial and relaxed atmosphere surrounding it”.

Generally, the attitudes in the society are similar to the ones seen in the English classrooms; she thinks that most people in Sweden today are of the opinion that British English appears “more educated and sophisticated”, whereas American English represents the exact opposite values as “the variety of the working class and young people”. For English teachers in Sweden this means that - even though she points out that perceptions and values like these are shown to slowly grow fainter – many still cherish British English as the most prestigious variety. She also calls attention to the ambiguous attitudes one can detect among the students: meanwhile having American Englishes as the most positive varieties seen from their perspective, she still believes that her students would argue that British Englishes are more “smart” and sounds “better”.

When asked what attitude she has towards British and American English, she reasons that to her “American English is more neutral, and easier to pronounce”. She also believes that American English is the variety easier at hand both when it comes to spelling and orthography. In an overall description she would say that “American English appears less connected with class belongings”, and moreover has a “younger approach”. On the contrary, “British English more obviously signals class and level of education” and has “associations with snobbishness and humor”. The teacher finishes off the interview by stating that to be able to speak proper British English it feels like you “awkwardly have to change the voice”, which probably is why she finds it “comical”.

4.1.4 School B – the male teacher

The male teacher at School B [49 years old] belongs to an older generation of English teachers and argues that he thinks that you tend to like the variety you were raised with. For him it has always been British English (RP) being taught in school, and this is what comes natural to him both when writing and speaking. On the other hand, the male teacher states that “there is no reason really why I should favour one variety above another”. As it is, he believes that students easier understand and speak American English, and this is also reflected in the English textbooks; as it was before, all the teaching material was in British English, whereas today there is a balance between the two major varieties.

Both in school and in society our informant senses a change in attitude towards what English variety has the highest prestige. His students, and as he perceives it, a majority of the younger generations, rather take on American English than British English. American English is considered to be “cooler” while British English is “moth-eaten and old-fashioned”. He settles that this acquired modern prestige is indeed widespread in Sweden

today. However, he thinks that the choice of American English is as much a reaction towards the “stiff upper-lip” notion many associate with British English, as it is an active choice. The “relaxed and easy” perception of American English makes it easier to conceive as “less snobbish and more down-to-earth”. Furthermore, the male teacher argues that the American culture, such as music, film and fashion has “constantly gained ground in Sweden ever since the first films came around from Hollywood”, which he means is one very plausible reason why the variety slowly has won on British in Sweden.

Regarding what variety he believes English teachers in general prefer, he still thinks that many teachers have British English as the variety with the most academic prestige. The same question but with the students in focus led him to ponder, and after some consideration he answered that he would say students still believe British English to be the most prestigious variety. He thinks that many students still refer to British English as the “real” and “original”, and “more correct” variety – no matter what variety they in reality prefer.

In spite of the fact that he both speaks and mainly teaches British English he is of the opinion that it is “no longer possible to differentiate varieties with the students” – at least not in upper secondary school. He does not find it reasonable to demand such distinctions, and that “focus is on communication rather than what variety you are to communicate in”. Nevertheless, he still asks for a certain degree of consistency when the students are writing more formal essays. And he admits to sometimes both urging and encouraging students to be consistent even when they speak – because there are still conventions to follow, but there has to be a balance of how much you are to bring up in your teaching.

When he describes British English he begins by saying that it is “nice to listen to”, and that “it is not as anonymous as American English – it reveals something about the person when communicating”. It is a superior variety to bring about humor in without sounding “too cheerful or tactless”, and “it [British English] breathes of history and culture”. American English he portrays as “a variety with more discordance between pronunciation and spelling”, and as a “symbol of the New World”, since American English is the variety which more and more people around the world adopt.

4.1.5 School C – female teacher

When we asked the female teacher [35 years old] at School C which variety she prefers she stated that she would like to answer Australian Englishes or South African Englishes, but if she had to choose between American and British Englishes the answer would be British

Englishes. She argues that British English both sounds and comes out more beautiful to her when written than American English; British varieties appear as “more neat”. Furthermore, she believes that what variety you prefer “depends on your former experiences concerning that variety” – according to her variety choices are often on an emotional level.

The teacher speaks British English with “a certain touch of Australian English”. This is because she has lived in Australia for a longer period of time, and she can not see any disadvantages of using a mixture of varieties as an English teacher – at least not when it comes to pronunciation. She reckons that it does not matter if your language is colored by many different Englishes and furthermore your native language. This applies both to students and teachers. To a teacher it is valuable to recognize and be able to point out divergences between varieties. However, our interviewee disapproves of the old Swedish way of “stubbornly trying to separate different Englishes” – and high-lighting British English, RP, as the better English - of “pure academic tradition”. She also points out that according to the National steering documents “communication is in focus”, and as a student “you are to be able to recognize English varieties and the differences amongst them and not to produce a certain variety yourself”.

Our informant states that she has not experienced any changes in attitudes for quite a long time neither among teachers nor among students; it has been accepted to mix varieties for more than ten years in the Swedish school, and this could be done in much the same way today as it could already ten years ago. The implication that spelling should be rather more variety consistent than pronunciation is, according to her, more well-founded but she still can not see that this can be called for in upper secondary school.

To appoint the most prestigious variety out of the two – American English or British English - is “a hard nut to crack”, and after some thought she answers that “a distinct use of authentic English carries more prestige than the varieties themselves”. The female teacher argues that even though she well recognizes differences in attitudes amidst school staff and students to American and British Englishes, what is “most prestigious is to reach an English which is close to native English of any kind”. This is true when it comes to accent, but for many of the highly theoretical students there is often an urge to keep to one variety even when writing. Then she adds that, in spite of these widespread intentions and attitudes, few students actually manage to keep to one variety at the end of the day.

She describes British English as “amusing and entertaining” bearing the comedy films and TV series in mind. British English is perfect for joking and pleasantries. On the minus side, she mentions that it shows “a tendency to become nasal”, and is thereby also by many

people perceived as arrogant. Furthermore, British English undeniably feels a bit “conservative and dust-laden”.

What first springs to her mind when we ask her to describe American English is that it sounds a bit “dim-witted and unintelligent”. She has seen many “American b-films” over the years and even more dumb Americans interviewed in “sleazy talk shows”, which have damaged her conception of American English. Then she makes a reservation, and mentions “the American used in for example Woody Allen productions is on the contrary beautiful and pleasant to listen to”. The general feeling for American English is that it is “innovative and mainstream”.

4.2 Attitudes among students

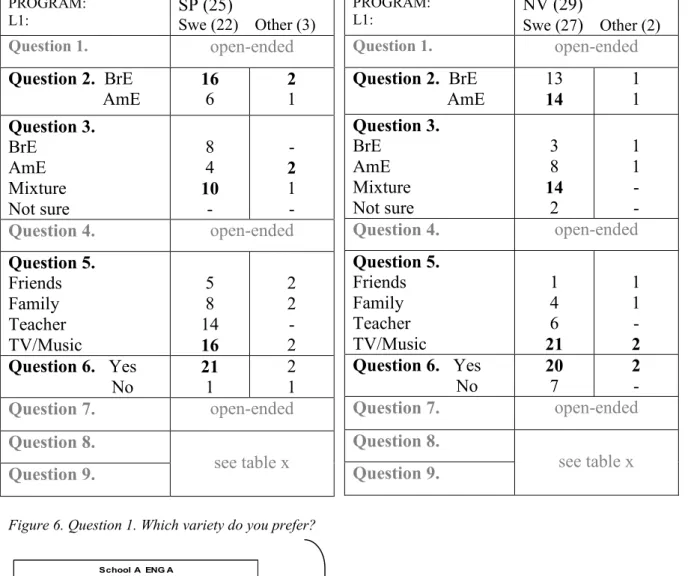

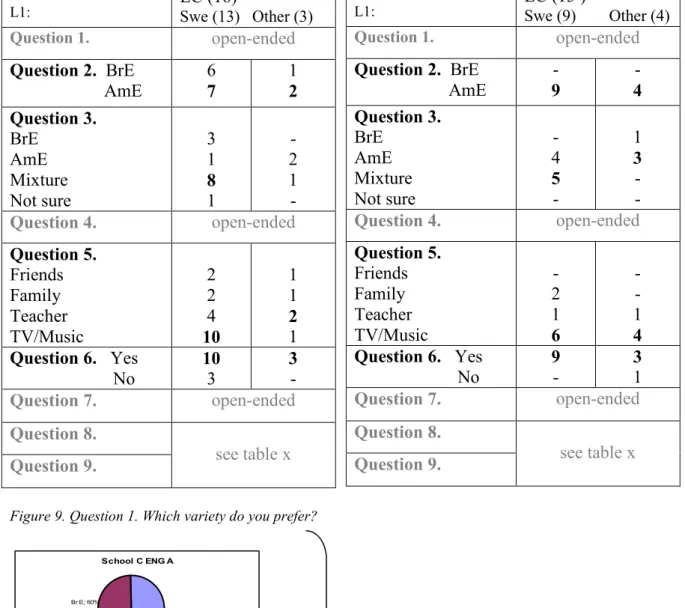

A total of 112 students assisted us in our investigation. These students belong to six student groups; two groups from each upper secondary school in our research. We have deliberately chosen one English A group and one English B group in each school. Worth mentioning is also that all the students have one of the interviewed teachers as their English teacher.

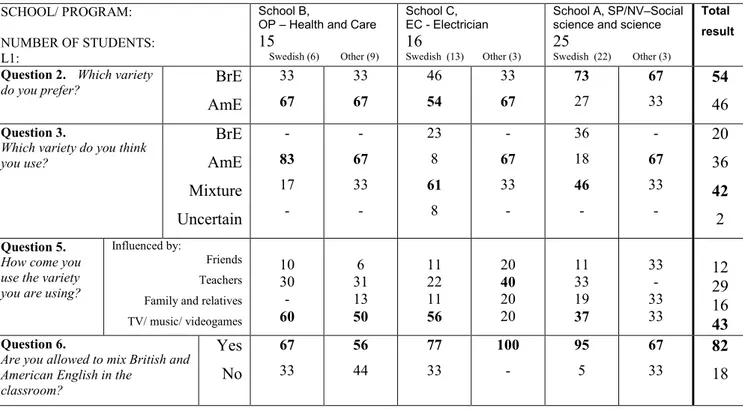

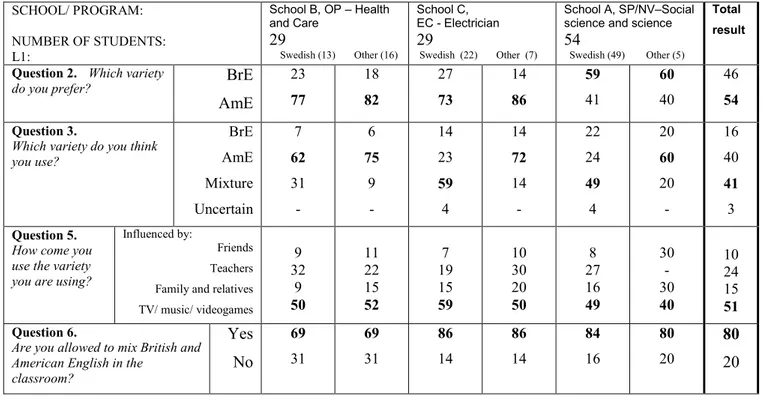

Based on the answers from the questionnaire one can make the overall conclusion of the combined result from the three schools that eight out of ten students (80%) feel they are allowed to mix British English and American English in the classroom. It is extraordinarily even between the two collective varieties with a slight advantage for American English – which 54% of the students state that they prefer. Nonetheless, it is not American English most students recognize as their own variety, instead 41% answer that they use a mixture of the two major varieties. Even more interesting is the fact that there is a vast majority in every single student group that has chosen popular media (TV/music/videogames) – which can truthfully be said to be overrepresented by American English – as the reason why they use the variety they do. In some student groups twice as many has answered popular media to be the main source of their variety than the ones who claim to be influenced by their teacher – in all student groups the teacher influence is down to a third and less.

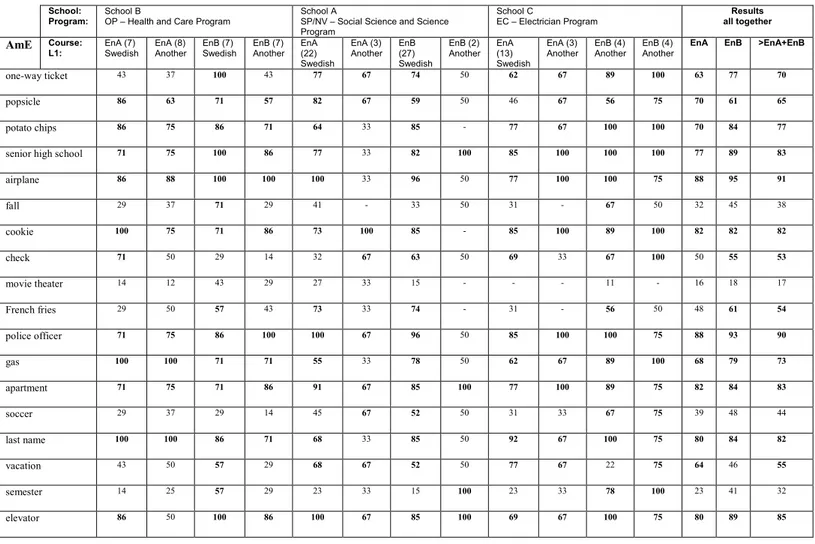

The vocabulary and spelling check on the second page of the questionnaire (see appendix 2–5) also gave some general picture of what variety the students prefer (see appendix 9–11, 14–16). There is a predominance of American spelling even with the more theoretical students. Though, it has to be said that the percentage of British spelling evidently still is higher among the theoretical students than amongst the vocational students. This American dominance is seen in regard to vocabulary preferences as well. And when it comes to

vocabulary only a few British words were fancied in more or less all the groups, namely autumn, cinema, football and term (see appendix 13.). These are words that are either close to the Swedish equivalent or words that everybody for other reasons seem to have taken to heart.

Another general conclusion that can be made is that students with another native language than Swedish are more likely both to prefer and to recognize American English as the variety they use. The only exception is among the immigrant students at School A: a majority (67%) state that they recognize American English as their variety, whereas two out of three students still claim they prefer British English.

4.2.1 School A

The students in the two theoretical programs, Social Science (SP) and Natural Science (NV), at School A differ from the other two schools in results. Almost six out of ten (59%) of the students in the English A and English B together prefer British English to American English. The academic tradition of this school can be detected in the students’ answers, where students categorically point out differences as: “BrE is more proper and I think it is nicer. AmE is just an ugly variety” and “To me British sounds more academic and nice (even if British slang is not understandable to me). American is careless and ‘wide’ in the way the words sound more thick”.

Even the students, who are in favor of American Englishes, show that they recognize British English as the original variety and the uniquely academic one: “English [read British English] […] is what you should learn. The subject is not called American“ and “American English is based on British English and has become more rough” and “British English [is preferable] because it is better to learn from the source. American English comes to you from the TV”. This attitude of having British Englishes as some kind of real English, as supposed to American as an everyday variety comes out in almost every comment in the first question concerning what variety they prefer. The perceptions can not be expressed more directly than in the following two comments: “Bre [read BrE] is more of high-class” and “American ENG is cooler”.

These attitudes towards the varieties are to some extent in contrast with the varieties the students declare they use: in the English A group, there were as many as 75% stating they prefer British English, still half of the students (48%) claim to speak a mixture of the two varieties at hand. This is explained by one student when he claims that “even if the teacher focuses on British, the student is finally going to mix it with American pronunciation

because we live in such an international society”. The students at School A are according to their answers more or less involuntarily influenced by American Englishes: “I have always heard BrE in school and I think it should be that way. On the other hand you mostly hear AmE, but personally I think that BrE is nicer and sounds more correct”.

The students in favor of American Englishes seem to be more positive towards any variety, and not only American: “It is important to understand all varieties, but you don’t have to be able to speak them all. Teaching should therefore include both American and British. As it is today, it is almost too much British”. And some students even question the traditional way of dealing with varieties in the Swedish schools claiming that “It does not matter [which variety is being taught]. Both. The attitude that British English is the original and that that is what we should learn, I think is strange. We should compare and learn the differences” and “Teachers should use the variety they feel most comfortable with; it makes their attitude to the whole thing, better. But the students should have the opportunity to be familiar with the other varieties too”.

One of the students argues that British English is not authentic outside the classroom and in other countries than Great Britain: “Mostly in classroom. Used only in Great Britain, not in the rest of the world or in the movies”. This student is an exception among the students at School A. When asked to describe the varieties as seen above already a large majority of the students at School A are positively disposed to British English, and describe the collective variety as “…nice, sounds more academic”, “more respectful to use” and “Snobbish, haughty and a bit square. More difficult to spit out the words in fast order because everything has to be stressed, but you earn more respect and seem educated”. But there are a few comments that confirm the attitude that British is less modern and not as authentic as every-day variety as American is perceived even among the students at School A: “To me it is more of nice English that is used on special occasions”.

The students describe American English as more “relaxed, rural and more as a dialect that ordinary people speak” and is associated with youthful fun and popular media: “It is ok, if it is not too much “Texas” dialect – it is horrible” and “Lighter slang variety that works good in higher pace, sounds better among ordinary people, young people, and has a more fun sound”. Other comments when asked to describe American English are that it sounds “Casual, superannuated, a bit easier to learn due to media” and that it is less complicated to pronounce: “It goes faster and is easier to speak”. All in all, the students seem, with few exceptions, quite positive towards both the varieties.

4.2.2 School B

At School B both student groups study the Health Care Program, and they are therefore in general not as theoretical as the students at School A. As a result, the attitudes differ quite a lot between the two schools: the students seem to reason in similar turns about the varieties, but the students at School B are in their responses less attached to British English than the School A students. Few students at School B comment on British English in a positive manner, while almost everyone from School A – no matter what variety they prefer – relate British to something positive and describe qualities as well as negative aspects.

Amongst the students at School B there is a convincing majority in favor of American English: in the English A group 67% of the students prefer American English, and in the English B group as much as 93% of the students speak in favor of American varieties. And it is interesting to see that many of them do not seem to have pondered exceedingly on differences and of pros and cons of the two varieties. At any rate, not near as much reflection is received in the replies from the School A students.

The students at School B explain the differences between the two varieties as British English being more “delicate and unfashionable”, and American English as “more slang and easier to speak”. The variety ideals are surprisingly similar throughout the two groups of students at School B. One comment that is recurrent in the answers from School B is that British is described as being almost “unreachable in that it is difficult to speak”. The students at School B also bring about more class related perceptions when they evaluate British English, such as: “They who speak BrE appear well brought up”, “It’s [BrE] a good language for better people” and “It sounds as if you are rich if you speak British”. Still the greater part them speak in favor of American English, and as one student phrased it: “I like American even though and because it is rough and cool”. It seems that the students at School B consider American English to be more accessible for them as young second language users: “You are more use to hear it [AmE] and it’s more common to us” and “More convenient, modern and more accepted to speak when you are young”. Even among the two students in the English B class who were pro British English the perception is that it is “…pleasant and nice, but I don’t speak it”.

Interestingly, not a single student in the English A class claims to have British English as their own English. This even though almost a third of them say they are influenced by their teacher in the choice of what English variety to choose. Their male teacher [49 years old] consistently uses British English in his teaching. In the English B class the young female teacher uses an American variety, that she exercises influence on the students would be one

possible explanation that a vast majority in that group imply they speak American English. Another matter that is interesting is that the immigrant students in the B-group state they use American English to a greater extent (86%) than the students with Swedish as their native language (46%). It is difficult to make any conclusions of why they are devoted to American English to a larger extend, but you are inevitably thinking of Modiano’s reasoning that these student’s jargon is reckoned to correspond better to American English: “With cultural influence, for example, jargon associated with youth, with consumer products, or with the popular vernacular of American television and film, the decision to adopt to AmE features can be a conscious choice made by someone who for various reasons feels compelled to use such language” (Modiano 1998:243).

Looking at the results in last two questions concerning spelling and vocabulary you see that the students, with a few exceptions, in fact use the variety they to a large extent claim to both prefer and to use – namely an American English variety.

4.2.3 School C

What first strikes you about the attitudes among the students at School C is that there is a remarkable discrepancy between the two investigated student groups: in the English A group 60% are in favor of American English, while all the students (100%) in the English B class prefer American English. Worth mentioning in this context is that both groups have the same young female teacher [32 years old], a teacher who speaks British English with some Australian elements. Then again, this could make sense if you consider that in the English A group almost half of the students state that they are influenced by their teacher, whereas only two students in the English B group mention the teacher as an influencer. Another factor that could contribute is that the teacher told us that the English A is unusually theoretical for the Electricity Program.

The consulted students at School C seem to be more likely to have a liberal approach to the two major English varieties. On the question if they are allowed to mix the varieties in the classroom the largest majority of students (86%), in comparison with the other schools, state that they are indeed allowed. Some students explained their close to impartial attitude by saying: “[I] think that the teacher should teach British English, but on the same time respect if someone speaks American and rather learn that”, “It depends. A mixture of British and American English [should be taught]” and “It doesn’t matter to me, as long as we get to learn the language well”.

When asked to describe American English and British English all the students in the English B group answered like-mindedly and assuredly about what variety is the superior of the two. American English is described in much a similar way by each student as the variety which “Sounds better”, is “Better”, which “Sounds more natural” and “Suits me better outside school”. In much the same way, and as black and white, are the descriptions of British English: “I don’t like it the least”, “Sounds exaggerated and snobbish”, “Difficult to understand” and “Sounds strange”. In the English A group the opinions are more heterogeneous and the attitudes towards American English are not all positive: “More slang, ok” and “More ‘street’ and easier to speak everyday” and “American English is cool and relaxed compared to British English, but it doesn’t sound as correct”.

5. Analysis and discussion

Our research shows that there are distinct attitudes towards the two major varieties of English among both students and teachers. Interestingly, the attitudes both within and across these two investigated groups can be said to be surprisingly homogeneous. In other words, teachers and students have rather similar perceptions and associate British English and American English in most the same way. What does differ is the emotive level of the words chosen to describe the two major Englishes. Depending on what preference our informants have they repeatedly describe the varieties with synonyms carrying either negative or positive charges. British English is recurrently described both as “snobbish” and in a more positive fashion as “high-class”, whereas American English is perceived either as “youthful and cool” or “dim and uneducated”.

The most evident difference between teacher and student attitudes can be described as teachers using the variety they prefer, while you among the students, especially in the more theoretical class groups, frequently see that they prefer British English but use American English.

The teachers describe the two major varieties along the same train of thoughts as their colleagues, but reason differently not only to what variety they teach, but also concerning the importance of being variety consistent. Our investigation shows that, it is more a general approach to language that stands out when we discuss the English varieties with them; the three teachers who principally prefer to regard the English language as a tool for communication value the general orthography, structural knowledge, idiomatic expressions and stylistic level more than any specific variety. At the same time, some teachers did state that they ask students to be consistent when writing. These teachers make a clear distinction

between spoken and written language, and say it would be difficult to expect students to produce a native-like and variety specific speech when not being in a natural language environment, especially when being influenced by different varieties. In other words, all the teachers agree that it is impossible to demand a variety consistency from upper secondary level students when it comes to spoken English, whereas two teachers argue that it is more feasible and important to be consistent when writing. This view among the teachers against demanding consistency in spoken English corresponds well with what Modiano concludes: “the differences between AmE and BrE with respect to pronunciation are apparent to native speakers, but not always so clearly differentiated in the ears of the second language speaker” (Modiano 1996:9).

Moreover, all the teachers explain that the English variety they use when teaching, is the variety which they find most natural to them personally and always use outside the classroom. In other words, none of the teachers state that they have a certain “teaching variety”. They all argue that their personal variety is directly related to their personal experiences and emotional preference, for instance living in an English speaking country and more emotional factors as to which variety is regarded as an important element to their own and professional identity.

The teacher’s attitudes towards the two major varieties are homogeneous in that they all describe them in a concordant way. British English is described as more class-marked, more educated and sophisticated. Besides this, British English is perceived as humorous, but rigid and conservative. They describe American English as less connected to social class, more casual and easier, for Swedes in general, to acquire. This corresponds well with what many experts argue. One of the latter is Odenstedt who basically claims: “[it to be] easier for Swedes to imitate the American intonation (Odenstedt 2000:137).

Furthermore, the teachers associate American English to media, popular culture and youth. And all of them make the same interpretation concerning the students’ attitudes, namely that they think that most students both prefer and rather use American English. These hypotheses among the teachers are mainly based on the fact that modern media has a very strong influence on the Swedish youth’s choice of variety. What we see from the results of the students’ questionnaire is that most students in fact both prefer and think they use American English. Deducted from the limited vocabulary and spelling part, it is a fact that they use American English to a large extent. Nevertheless, the teachers were not solely correct in their assumptions, since it showed that British English still is the preferred variety among more theoretical students.

While most people connect prestige to either American or British English - or different kinds of prestige, as mentioned before either overt or covert prestige (Aithchison 2001:83) can be applied - one teacher presents an intriguing perspective on the prestige matter. She thinks that it is not as important, and prestigious, to speak either British or American English, as it is to speak any of these varieties as native-like as possible. This teacher’s reasoning correlates to the expressed attitudes of the other teachers; even though neither one of them advocate a specific variety nor demand consistency when the students speak English, they truly intend to support students who specifically use one variety and encourage them to stick to it. In other words, even though stating the impossibility of demanding variety consistency in spoken English all the teachers still acknowledge the advantage if a student has the capacity and interest to be consistent.

This concordance does not fully correspond with what Modiano advocates, namely “that research findings indicate that it is becoming increasingly probable that the Americanization of Euro-English will eventually lead to the establishment of MAE as the educational standard, not only in Europe, but throughout the world” (Modiano 1998:242). This could well be, at least in practice, since the students to a high degree did answer that they speak a mixture of the major varieties. However, the attitudes among teachers and students today still show that a native-like mastery is prestigious, even though the focus in the Swedish educational system is not exclusivity.

As Modiano argues there is a difference between having English as a foreign language and a second language: “L2 speakers of English in Europe […] will be in a better position to preserve and cultivate the distinctive features of their own diverse speech communities if they speak a less culture-specific variety of the language”, whereas he states that learning English as a foreign language still more focused on a native-like mastery (Modiano 1998:244). The female teacher at School A argues along this train of thought when she states that the actual knowledge of the language is more important than the variety used. Expressed differently, but with the same focus of thoughts, the female teacher at School C pin-points the irrelevance of, as a teacher, working with the purpose of purifying the student’s varieties. Interestingly, all the teachers except for the female teacher at School C share the same opinion; working towards refined English varieties is relevant only when a high-proficiency level of English has been reached among the students. Most often, the teachers feel that this is not feasible in upper secondary school. However, as mentioned before, they all verify that they encourage students who want to use, or in fact already more

or less use, one specific variety. Trudgill and Hannah discuss this matter in International English, and argue that:

…it is not reasonable to expect a Dutch student of English who has learnt EngEng at school and then studied for a year in the USA to return to the Netherlands with anything other than some mixture of NAmEng and EngEng […] Given that the ideal which foreign students are aiming at is native-like competence in English, we feel that there is nothing reprehensible about such a mixture and that tolerating it is by no means necessarily a bad thing. Neither is it necessarily bad or confusing for school-children to be exposed to more than one model. (Trudgill & Hannah 1994:2–3)

There is a minority of the students in all student groups who answer that they are influenced by their teacher when shaping their own English. This, together with the fact that many of the students prefer and use another English variety than their teacher, implies that the teacher has only a marginal impact on their students’ choice of variety – at least according to the students themselves. Mobärg came to the same result in an extensive research executed in upper secondary schools in Sweden (1998:260–261).

It is today a fact that students are vastly influenced by North American popular media. In the student questionnaire responses it was clear that the students were aware of this influence, and that this was the major factor that affects both language use and attitudes among them. In other words, a majority of the students are aware of the differences between American English and British English, and also what variety corresponds to their own English.

When it concerns students’ attitudes, many had decided opinions to one of the two investigated varieties. It appears that a group of students at School C, which according to the teacher were the less theoretical of the two groups, have taken a stand against British English and are clearly in favor of American English. They are more categorical than any of the other students in their answers. Similar responses are seen in one of the student groups at School B where the students show the same categorical rejection of British English. What is interesting in this is, not only the fact that our results of the questionnaire suggest that the more theoretical program the more sympathetic the students are to British, and vice versa with American English, but the fact that students at the more theoretical schools and programs seem to be more likely to be positive to both varieties.

Another interesting finding in our research is that students who do not have Swedish as their mother tongue to a larger extent seem to prefer and state American English as their preferred variety. It could depend on other factors than the ones we decided to distinguish in our questionnaire. Therefore, this is something which is difficult to analyze further.