Student Thesis

Level: Master (1 year)

Euroscepticism – from 1986 to 2020 and beyond

Eurosceptic – a person who is not enthusiastic about increasing the powers of the European Union (The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary of English, 2005)Author: Béatrice Öman Supervisor: Thomas Sedelius Examiner: Kjetil Duvold

Subject/main field of study: Political Science Course code: ASK22M

Credits: 15

Date of examination: 27 August 2020

At Dalarna University it is possible to publish the student thesis in full text in DiVA. The publishing is open access, which means the work will be freely accessible to read and download on the internet. This will significantly increase the dissemination and visibility of the student thesis.

Open access is becoming the standard route for spreading scientific and academic information on the internet. Dalarna University recommends that both researchers as well as students publish their work open access.

I give my/we give our consent for full text publishing (freely accessible on the internet, open access):

Yes ☒ No ☐

the 2019 European Parliament elections and to this date. The thesis was conducted with a particular interest in gathering more knowledge on using an evidence-based method in political science. The purpose was twofold, therefore: one to see how the concept itself has evolved in research, in terms of definition and salience as well as in terms of measuring and explanatory factors, and the other to see if the method used is appropriate to this purpose.

From the data gathered, it can be said that the method is pertinent and relevant when assembling research from a widespread and multifaceted area in terms of geography and content, since it is meant to avoid the pitfalls of ‘picking and choosing’ data. The articles thus uncovered have shown that there is a red thread in research on Euroscepticism, that its context has changed and therefore its content, and that Euroscepticism 2020 is a salient issue.

Keywords:

3 Acknowledgements:

This master’s programme promised to deal with democracy, citizenship, change, with globalisation, European integration processes, polarisation, division, separatism, legitimacy, authority, the traditional nation state, and political culture. I suppose that, since we were the first to partake in this massively ambitious experience, our teachers were probably just as nervous as we students were. I want to thank all our teachers and supervisors for a fantastically illuminating and worthwhile year – every single one of you, who answered from abroad, during paternity leave, late at night, during weekends and holidays. We were a 100 % virtual class before others were forced to do the same thing and managed to forge bonds and mutual understanding all the same, maybe faster and with better continuity than in a traditional classroom. I am deeply impressed by and thankful for your deep commitment to making us succeed (against all odds, as it sometimes felt). I hope that we have shown you that it has been worth your while. As for my own thesis, I need to add that Professor Thomas Sidelius, my uncannily patient supervisor, has had an equally uncanny ability to ask the right questions in order to help me find some needles in my overfertilized mental haystack.

I am thoroughly grateful to you gals and guys in my class, covering 30–40 years of age difference, three continents, entirely different entry points in terms of expectations, experience and knowledge. If you’ve had half as much fun as I had getting to know you and working with you, then you’ve really had fun.

And, as always, I am so very deeply indebted to my loving husband. We are incredibly lucky and privileged to be free to live by our greatest passions: family, music and politics, together, in an impossible order of preference. That, and generally shaking things up whenever we can. If we don’t believe we have the means to make the world a better place, then, frankly, who will?

4

Index

1 INTRODUCTION ... 5

1.1 THE ’BIRTH’ OF EUROSCEPTICISM ... 5

1.2 PURPOSE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 7

1.3 DELIMITATIONS ... 8

1.4 DISPOSITION ... 8

2 PREVIOUS RESEARCH AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 9

2.1 EUROPEAN INTEGRATION, ATTITUDES AND SCHISMS ... 10

2.2 EUROPEAN INTEGRATION AND COOPERATION ... 11

2.3 EUROSCEPTICISM AS COROLLARY OF EUROPEAN INTEGRATION ... 12

2.4 EUROSCEPTICISM AS CONTESTATION OF EUROPEAN INTEGRATION ... 14

2.5 EUROSCEPTICISM AS A MULTIFACETED CONCEPT ... 15

2.6 EUROSCEPTICISM AS AN EVOLVING CONCEPT ... 16

2.7 SUMMARY/CHECKLIST ... 19

2.7.1 PROPOSED STARTING POINTS ... 19

2.7.2 FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS ... 19

3 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHOD ... 20

3.1 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 20

3.2 THE SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW IN RESEARCH ... 21

3.3 THE BEST FIT FRAMEWORK ... 24

3.4 CHOICE OF DATA SOURCE ... 25

3.5 SEARCH STRATEGY ... 26

3.6 SEARCH PROCESS ... 27

4 THE EVOLUTION OF THE CONCEPT OF EUROSCEPTICISM ... 28

4.1 EUROSCEPTICISM 1998-2017 ... 28

4.1.1 HOW EUROSCEPTICISM IS MEASURED AND EXPLAINED ... 29

4.1.2 HOW EUROSCEPTICISM IS DEFINED ... 33

4.2 EUROSCEPTICISM 2018-2020 ... 37

4.2.1 HOW EUROSCEPTICISM IS MEASURED AND EXPLAINED ... 37

4.2.2 HOW EUROSCEPTICISM IS DEFINED ... 40

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ... 46

5.1 DISCUSSION ... 46

5.1.1 DEFINING EUROSCEPTICISM ... 46

5.1.2 MEASURING EUROSCEPTICISM ... 46

5.1.3 EXPLAINING EUROSCEPTICISM ... 47

5.1.4 SALIENCE OF THE CONCEPT ... 47

5.1.5 DEPENDENT OR INDEPENDENT VARIABLE ... 47

5.2 CONCLUSION ... 48

5.2.1 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 48

5.2.2 EPISTEMOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 49

5.2.3 AVENUES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 49

5

1 Introduction

1.1 The ’birth’ of Euroscepticism

Eurosceptic – a person who is not enthusiastic about increasing the powers of the European Union The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary of English, 2005 (2020) Eurosceptic – person who is opposed to increasing the powers of the European Union

(Oxford Dictionary of English 3rd edition 2010, online 2015) (2020) This thesis deals with the evolution of the concept of ‘Euroscepticism’ since 1986. As we can see, ‘authoritative’ dictionary definitions from the same publisher can vary

significantly between countries, with a mere five years between them, the latter equalling scepticism with opposition and the former defining it as missing enthusiasm, while the term

scepticism, according to both, refers to doubt and criticism. Without entering a detailed

semantic discussion (pertaining to linguistics), it is not altogether surprising that the conceptual discussion of Euroscepticism (pertaining to political science) has become

increasingly vivid since then, and the answers provided by these dictionaries beg the obvious question: what exactly is Euroscepticism? If this were a purely semantic question, then a thesis in political science might end here. However, the articles subsequently presented show that there are pertinent reasons to study the concept. The most recent findings will show that Euroscepticism diversifies, that it is connected to radical populist agendas, economic crises, to growing social polarisation, to relationships with countries beyond the outer border of the European Union, to cultural, political, and religious heritage, to name but a few, all of which have an impact on domestic and European policy-making, and therefore the future of the EU and its growing population. All these are aspects of a concept that has developed from lack of enthusiasm via lack of control into a complex political and social kaleidoscope. Every

movement will shake the picture and rearrange the bits. Bakker, et al., with news from June (2020) on a new round of CHES data, were just in time to quote Covid-19 as the most recent traumatic event to bring about ‘economic destruction’ and expose ‘Europe’s fragile

solidarity’. With that in mind, higher doses of Euroscepticism may not be the best way towards a cure – to anything.

With this thought in mind, the biggest challenge behind this project has been the self-given promise not to set out from a normative standpoint. As a confirmed European,

6 look at the European Union, its past, present and future, ‘from the outside’. But after living and working in a number of different parts of the Union, I have come to accept that, with the varied experience Europeans have gained from living in the Community since it was founded, scepticism towards it may be considered pure common sense or, at least, something to keep in mind each time major changes are made to its construct. Each Treaty has had a crucial impact on what is admissible or strictly forbidden and on which political level owns what decision-making power, not to mention who has the right to join or leave the Union. As most of us EU-citizens probably will hasten to confirm, the European Union has evolved into a dauntingly complex network with legislation that seems to increasingly impinge on national sovereignty. All these developments may be met by great joy over e.g. dismantled customs offices or ambitious student exchange programmes, but also by disappointment, disbelief and criticism after costly yet ineffective policy measures, all a posteriori statements – reactions to results.

Enthusiasm, doubt and opposition have in common, however, that they are a priori statements

– attitudes to things that have not yet happened. Hence, before we begin, let us differentiate between scepticism towards the workings of the EU as such, on the one hand, and scepticism of its relative accomplishments, on the other. The pilot light of this paper is to examine whether scepticism towards the EU not only is a result of its present state, but also a reason

for its present state.

The term Euroscepticism itself reportedly came into use in the public political debate in 1986 - see e.g. Leruth, et. al (2018, p. 3), Szczerbiak & Taggart (2008, p. 261), Harmsen & Spiering (2004, p. 15). In many ways, that year was a game changer for Europe: on January 1st, Spain and Portugal joined the European Communities after having waited since 1977

(Spain after Franco's death and Portugal after its first democratic elections in 50 years). Also, in January 1986, the UK and France, two historically uneasy companions, announced that they were planning to build a channel tunnel to connect their countries. In February, the Single European Act was signed, with significant changes made from the Treaty of Rome from 1957 and a mission to prepare for a single market, which subsequently resulted in the Maastricht Treaty to be signed in 1992 (Bogdanor, 1989, p. 205). The European flag was raised to the European anthem for the first time on May 29th in front of the Commission

building in Brussels. On June 11th, European Parliament, Council and Commission signed a

joint declaration against racism and xenophobia (europa.eu, 2020). That same year, however, the Chernobyl disaster on April 26th made it painfully clear to the entire European population

7 that this type of catastrophe neither respects geographical nor political borders.1 In other words, dramatic events in very different yet interconnected spheres of life set in motion an equally dramatic number of snowballs that year – politically, socially, and economically, and all of them together rolling a much larger snowball in front of them, referred to as European

integration.

European integration, the process of ‘coming to constitute a political whole which can in some sense be described as a community’ (Pentland, 1973, p. 21) (Mutimer, 1989, p. 76), had been ongoing since the institution of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952, and the amount of scepticism or goodwill towards the project had varied significantly among countries from the beginning, both in terms of governments and public support. Since this process has impacted on generations of Europeans in an increasing number of countries since then, it feels safe to argue that, as monolithic as it may have been perceived at any given moment in time, few political systems have evolved as dramatically as just the EU since 1952. Our perception of and attitude towards it, in its present shape or earlier, are therefore

dependent on where and when we became part of the process, and its future shape will be influenced by current perceptions and attitudes, not least in their aggregated form as ballots cast in national and European elections. I argue that that is also why Euroscepticism as an evolving concept in all member states has become such a relevant issue to examine.

1.2 Purpose and research questions

Motivated by the brief introductory discussion of the term above, its relevance for how we perceive the EU and how this can impact on its future, the purpose of this paper is to create an up-to-date perspective of how the concept of Euroscepticism has evolved since the term entered the public political debate in 1986. As a result of deliberations subsequently presented in Chapter 3 (Method and Material), this will be done by means of a

semi-systematic literature review of 48 research documents from 1998-2020 that have party-based Euroscepticism as their main subject. Four questions will be asked of the scrutinised research:

1. How is Euroscepticism defined?

2. How is Euroscepticism measured (scope, data & type of study)? 3. How is Euroscepticism explained (what aspects of it)?

4. What salience (relevance) does Euroscepticism have?

1 And so did the assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme on February 28th, 1986. As a by-note, the EU has been

8

1.3 Delimitations

A first cursory glance at available research databases showed that there is a wealth of material on European integration and Euroscepticism, and some crucial initial choices had to be made. As mentioned, this will be dealt with in more detail in Chapter 3.

• Choice no 1 was to decide on a method that would trigger an inductive process, i.e. produce greater knowledge without the pitfalls of foregone conclusions and circular reasoning.2

• Choice no 2 was to focus on party-based Euroscepticism, as an aggregate version of public Euroscepticism

• Choice no 3 was to limit the study to articles that refer to Eurosceptic/Euroscepticism as well as party/parties in their title, as a deliberate focus set by each of the authors, respectively.

• Choice no 4 was to subsequently limit the study to the most recent articles published among the results generated by Choices no 1 to 3.

These choices entail that relevant sources may be left out merely due to their choice of title, but the calculated risk has been that crucial oversights caused by this process will be corrected by the authors in the articles used for the present study (see Chapter 3). Since reproducibility is a prime objective of the method chosen, the process can be extended to further search processes and discoveries (rather than selection) of material.

1.4 Disposition

Chapter 1 gives a backdrop to the questions raised by this paper

Chapter 2 highlights seminal approaches to European integration and Euroscepticism Chapter 3 presents the research method used in this paper

Chapter 4 presents and organises the resulting material

Chapter 5 offers a discussion and conclusion, and attempts to identify research gaps.

2 My own perception and attitude may colour this thesis more than a little, which is one of the reasons for the choice of

9

2 Previous research and theoretical background

The term ‘Euroscepticism’ began spreading in 1986, the same year as the Single European Act (SEA) sat the course for Maastricht (European Parliament, 2020). The EC took gigantic steps forward in terms of policy and cooperation that particular year – some in Brussels, some in Strasbourg, some in the Hague, and a massive one across the channel between Dover and Calais, with all the consequences that entailed. In a note at the end of their introduction to a special issue of Acta Politica on the ‘Sources of Euroscepticism’ from 2007, Hooghe & Marks mention that the expression 'a Euro-sceptic at best' was first used in The

Times on 30 June 1986 to describe how M. Thatcher was perceived by most of the EEC

(Hooghe & Marks, 2007, p. 127).3 Dealing with the impending British presidency of the

Council of the European Communities on July 1st, the article pointed out that Britain, in

exchange, would be forced to accept a number of reforms leading to closer European integration and a wider loyalty to Europe (The Times 1986, 9). The term swiftly became sufficiently recognised to be added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 1992, but we can hardly assume that the notion of ‘Euroscepticism’ was created in Britain in the 1980s. The brief (in parts very personal) historical account and terminological discussion in the

introduction were deemed necessary to set the scene for the present study and to point towards the complexity hidden behind what may seem a simple concept.

The present chapter on theoretical background should provide some concrete entry points into a field not that easy to control in terms of sheer quantity since, despite or because of the relative novelty of the phenomenon, there is a large wealth of writing dealing with Euroscepticism. The offer is replete with articles, research papers, monographs and

anthologies using and/or studying it. As early as 2012, Cas Mudde referred to the field as a ‘true cottage industry of “Euroscepticism Studies”’ (Mudde, 2012, p. 193), an expression often quoted since, and their number has continued to increase exponentially during the years that ensued. The entry points presented here should serve as a red thread stretching from 1986 to the present day and highlight some central aspects. This does not mean that they

necessarily take precedence over the articles presented in Chapter 4, but they are part of the result and intended as a backdrop.

3 Number two of most relevant articles when searching for Euroscepticism as a single term on Google Scholar, with Cécile

10

2.1 European integration, attitudes and schisms

In their paper on ‘the evolution of public attitudes toward European integration: 1970-1986', Inglehart, Rabier & Reif claimed that public support for European integration had ‘stabilized at a high level during the last two decades’ (Inglehart, et al., 1987, p. 135). By means of data from Euro-Barometer, they wanted to ‘tap one’s general feeling of support or opposition to European unification’ and came to several insights on how this ‘general feeling’ had developed over time. While Germany was most positive from the outset, with France and Italy developing the same attitude in the 1970’s, Britain had remained ‘outside of the

framework’, so that the six original member states ‘developed an increasingly European outlook’, creating a ‘large gap’ that remained obvious as the six newer members subsequently joined, some of the latter more positively inclined than others (Inglehart, et al., 1987, p. 140). They differentiated between ‘utilitarian’ aspects (how much is invested as opposed to how much is gained) and ‘affective’ support for the idea of unifying Europe (does it feel right or not), with a remaining earlier cleavage between nationalities, but also a new detectable social cleavage between higher income, education, higher status occupations as an indicator for support ‘throughout the Community’ (Inglehart, et al., 1987, p. 143). In summary, they reported three ‘dismaying shifts’: the change of the social basis as described, but also sinking support from younger people as well as from people with post-materialist values, with the resulting insight that, as early as in the mid-seventies, the attitude that the EC has a materialist and economic agenda had taken hold over other post-materialist notions like unification, still with a remaining difference in attitude between the original six and the next six (Inglehart, et al., 1987, p. 152). Their portentous (and with hindsight ominous) conclusion was that bringing about a European Union was a gamble worth taking, although it could ‘split the Community in a worst-case scenario’ (Inglehart, et al., 1987, p. 155).

There were signs of new schisms developing while old ones had disappeared, with changing attitudes towards the growing Community’s purpose either as an economic project or a socio-political one, with European citizens developing different expectations from one generation to the next, with free trade, free mobility on the labour market, in education and for leisure at one end, and global challenges like saving the climate and ending poverty at the other. Inglehart, Rabier & Reif’s data and reasoning indicate that scepticism towards the EEC had existed, developed further, and was linked at that point to the extension of the European Community and the varying prevailing attitudes in its member states, respectively. This paper

11 will examine the phenomenon over time in closer detail. But, in par with other historical years, 1986 ought to be remembered as one in which borders were opened, limits extended, thresholds lowered, at the same time as their irrelevance in the face of disaster became frightfully clear.

2.2 European integration and cooperation

In turn, Inglehart, Rabier & Reif’s take on utilitarian and affective aspects provides an entry point to the question of how the European Union is constructed, what it should deliver and, maybe even more so, what it should not. According to the Treaty of Rome from 1958, the goal of the EEC was to create ‘an integrated multinational economy’ (Mutimer, 1989, p. 75). As Mutimer points out that, although there was no accepted typology of theoretical

approaches at the time, there were two approaches common to most attempts: federalism and neofunctionalism, with the former seeing integration as the creation of intergovernmental structures to allow for economic integration, and the latter as the creation of political institutions that allow for a new, integrated community to deal with economic integration, among other things (Mutimer, 1989, p. 77f) (Sweeney, 1984, p. 25). Mutimer’s article deals with the anticipated consequences of the then upcoming Maastricht Treaty, and the fact that it would have ‘profound implications for the political future of Europe’, the consequences of a central bank and common currency for monetary policy and the consequences of opening internal borders for immigration policy, for instance, which would not only of extend, but also transfer political legitimacy from national levels to a European level (Mutimer, 1989, p. 100f). Quoting founding neofunctionalist Ernst Haas (1958), who later assumed after the 1970s that the nation state was ‘not yet ready to be surpassed’ after all, Mutimer assumed in 1989 that Project 1992 (Maastricht) may give birth to the ‘world’s first truly trans-national political organization’ (Mutimer, 1989, p. 101)

Hooghe & Marks stated that neofunctionalists assumed that Europeans ‘could be created indirectly’, meaning that they (we) would become European citizens as a result of creating European institutions (Hooghe & Marks, 2006, p. 216). But, as they also pointed out, integration as a means to improve effectivity had not come tantamount to welcoming

supranationalism (relinquishing control), and that a European federation, a project by ‘post-war elites’, had not met with growing support (at least up to that point). And, so they continue, national identity played an important role in this respect, because it could be mobilized

12 politically against the transfer of decision-making power to other institutions beyond national borders. It can be intuited that Euroscepticism, at least in terms of public attitude, varied and was highly salient from the outset. We can also hypothesize that, where it existed, it also grew in strength with each of the steps taken towards ‘piecemeal integration’, i.e. integrating Europe bit by bit according to arising needs (Hooghe & Marks, 2006, p. 216). As Mutimer concluded, a new ‘economic entity’ would emerge after 1992 (Mutimer, 1989, p. 101). It is not altogether surprising that a change so drastic would have a stronger effect on public attitudes yet, and that it could be effectively politicised. It is not surprising either that it would have a stronger effect on those Europeans who were sceptical to the entire project to begin with, both from political elites and their less political public.

2.3 Euroscepticism as corollary of European integration

The issue of negative vs positive attitude towards European integration thus goes back to the birth of the Community at least, it increased in salience with time and after the

European Single Act, in particular. However, a first cursory and exploratory look at JSTOR, Google Scholar and Web of Science confirmed that a search for Euroscepticism and

Eurosceptic will not lend any results older than 1986, a very small number yearly until 1992, and a steadily increasing number of results after that, but the terms are used anecdotally and/or in a context outside of political science research. The first attempt at a definition of party-based Euroscepticism that gained a foothold in research was the one made by Paul Taggart in 1998, which is why his article on the subject becomes a theoretical entry point for this review.

Taggart called increased Euroscepticism the ‘corollary of European integration’, i.e. a self-evident side effect, and set out from the fact that it is not a homogeneous concept, but rather a set of symptoms that vary among countries and political parties as their response to a ‘recent acceleration’ of that integration (Taggart, 1998, p. 363). His purpose was to survey party-based Euroscepticism within countries in order to demonstrate that there is an

‘aggregate phenomenon’, and to relate party positions on the EU to their positions in national party systems (1998, 365). His often-quoted definition is as follows: Euroscepticism

‘expresses the idea of contingent or qualified opposition, as well as incorporating outright and unqualified opposition to the process of integration’ (Taggart, 1998, p. 366). From that it can be concluded that the attitude comes in many guises, some more drastic, some more nuanced.

13 As put by Taggart, it can be ‘softer’ (‘a broader disquiet’) or ‘harder’ (‘out and out

opposition’) (Taggart, 1998, p. 367). Among the national parties examined, he differentiated four types at the time: single-issue, protest-based, established, and factions within (Taggart, 1998)(1998, 368f). The most preponderant type according to Taggart, was protest-based (Taggart, 1998)(1998, 372). He also found that there is an ‘ideological diversity’ behind it that cannot be aligned with traditional differences on the left/right scale due to the advent of new politics parties (e.g. environmentalists) on the left and new populist parties on the right (Taggart, 1998)(1998, 374f). Euroscepticism can arise from entirely different positions and from different corners of the spectrum among different countries, which is why Taggart asked himself whether it was domestic politics rather than European issues that trigger it (Taggart, 1998, p. 378).

In his position map of parties from 1998, he positioned new politics in the uttermost left corner of ‘Global/ Community’ and populist parties in the uttermost right corner of ‘Individual/National’, with some others in the uttermost right corner of

‘Community/National’, while neither are well disposed towards European integration, albeit for opposite reasons (Taggart, 1998, p. 380). None of the established parties stood out as ‘unequivocally anti-EU' at the same time (1998, p. 381). One possible consequence that he names for this is that non-established parties may adopt a Eurosceptic stance in order to differentiate themselves from the established parties specifically because the latter do not (1998, p. 382). Nevertheless, the ideology of the party must be compatible with a Eurosceptic position (1998, p. 383). Taggart concludes that, if other issues than only Euroscepticism can be used to create ‘dissent’, then ‘the lines of division may converge and provide the basis for realignment of party systems’ (1998, p. 384). In other words, Euroscepticism, the complexity of European integration and the feeling of frustration emanating from it can be used to

politicise other issues. It can be used by political parties as a lever to further their own agenda. It should therefore be noted here that Taggart held a presentation in Seattle in 1997 that

contained much of the paper examined here, but with stronger focus on the ‘Populist Politics of Euroscepticism’. In that paper, he wrote that ‘populism is the agenda created around the negative reaction to the institutions of representative politics’, which turns populism into a mixture between political content and method and makes it ‘flexible’ in terms of ideology, as Taggart writes (Taggart, 1997, p. 16). In the article discussed above, the issue of negativity towards institutions in general is named as one aspect. Here, Taggart considers this protest, together with ideological flexibility and the notion of a national ‘heartland’, plus an added

14 popular proclivity to react badly to a political elite’s tendency to sit out difficult questions (referred to as ‘attentisme’), as themes that populism and Euroscepticism have in common (Taggart, 1997, p. 23).

2.4 Euroscepticism as contestation of European integration

In 1999, Marks, Steenbergen, Scott & Wilson conducted a first expert survey at Chapel Hill Center for European Studies (CHES) in the USA to 'evaluate the positions of national political parties on European integration' (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 966f), which introduced the concept of a combined new cleavage between Green/Alternative/Libertarian (GAL) and Traditional/Authoritarian/Nationalist (TAN) as an alternative or complement to the traditional cleavage between left and right (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 966). Their purpose was to investigate the occurrence of Euroscepticism in terms of its linkage to specific national policy areas.4Their seminal article is a discussion of ‘contestation on European integration’, which partly converges with Taggart’s ‘corollary’. But whereas Taggart’s paper examined European and national election results and subsequently mapped ‘party families’ according to ‘where they might reasonably be expected to be located on the basis of their ideology’ (Taggart, 1998, p. 380), the analysis carried out by Hooghe, Marks & Wilson is based on a survey involving a range of country experts who were asked to evaluate different policy areas in order to see whether this European contestation is part of domestic contestation, whether it can be aligned with Left/Right and new politics, and/or whether there are some entirely new issues that have evolved because of European integration (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 966). They reuse Taggart’s expression that integration is a touchstone of dissent for peripheral parties (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 969). Hooghe, Marks & Wilson agree with Taggart’s positioning of extreme left and extreme right parties, so that their inverted U-Curve goes from a bottom left corner to a bottom right corner of extreme opposition to European integration on a bell curve encompassing established parties in the middle that do not show such extreme signs of Euroscepticism (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 968). In other words, extreme left and extreme right are Eurosceptic, but for entirely different reasons, the one side because of it favours

nationalism, the other because it does not favour market liberalism (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p.

15 969). Like Taggart, they also concluded that, for parties, EU positioning is linked to

ideological positioning (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 971). Their data indicates that there is a movement in terms of different policy areas, so that cohesion, employment and environment show a slope from pro-integration left to less integration right (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 973). In other words, the policies proposed differ in their demand for national or supranational control, but so do their fundamental principles when it comes to all other policy areas as well, the latter not following the same movement from left to right.

Also, in agreement with Taggart’s view on single issue and protest parties and their Eurosceptic stance, they add the dimension of ‘new’ politics as an umbrella for different types of contestation related to entirely different aspects of life, e.g. immigration, ecology,

nationalism, cultural diversity etc (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 976). Based on earlier proposed labels for these dimensions (Inglehart, 1990; Franklin, 1992; Müller-Rommel, 1989;

Kitschelt, 1994; Kitschelt & McGann, 1995), Hooghe et al. designed a new scale to cut across the Left/Right dimension in order to accommodate party positionings along the lines of new politics, i.e GAL/TAN, with the added argument that these issues in particular pertain to the European dimension in their nature (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 976). That appears logical since they all have a cross-border dimension (Green Alternative Libertarian vs Traditional

Authoritarian Nationalist) (Hooghe, et al., 2002, p. 966), which means that they also raise the issue of who exerts more power over them at the national or European level. Their data also indicates that, while parties on the extreme right are clearly Eurosceptic, the GAL/TAN scale can help position other parties, both traditional and new, in terms of Euroscepticism.

2.5 Euroscepticism as a multifaceted concept

Although there are many correlations between these two approaches to the concept, there is an important difference between corollary and contestation, since the one is a natural consequence of another event or factor, a side-effect, whereas contestation can either be triggered as an effect of integration or express prior scepticism that will counteract one’s will to integrate. These basic predispositions, if we want to call them that, will have an effect on which ‘model’ of Europe an individual would choose (if given the choice): a federal

organisation like Germany or the USA with a European government with European institutions? In that case, what political level would maintain what power, nationally and within the EU? Or should the EU be an intergovernmental organisation with institutions that

16 simplify cooperation, but without any added common ground beyond these essentials? How would one avoid an evolving neofunctionalist scenario in which we indirectly will turn into Europeans eventually because the new functions required automatically will change the nature of the beast, whether we want to or not? Should the EU therefore not exist at all because the cause is not worth taking the risk? Or should it not exist because the concept goes against one’s personal grain altogether, because it simply is not deemed necessary? Hence, whereas a corollary is an effect of something else that has transpired, contestation can have more sources than that, and Euroscepticism may be a cause of contestation instead of an effect of

integration gone haywire in the eye of the beholder, to use two flippant expressions as one.

In 2012, Cas Mudde, as a highly notable researcher on the populist radical right, wrote a short comparative study of party-based Euroscepticism in which he compared the ‘most important ‘‘schools’’’, i.e. ‘The Sussex School’, which Taggart belongs to, and the ‘North Carolina School’, which Hooghe, Marks & Wilson belong to. In summary, he assessed that there were clear differences between them in terms of definition, data, scope, explanations (Mudde, 2012, p. 193). He reached the conclusions that 1) the two schools could benefit from cross-fertilisation and 2) Euroscepticism would grow and diversify (Mudde, 2012, p. 200f). The first can probably be said of all research, and the second confirms that there may be good reason for this new paper to be added to the growing mount. Mudde’s comparison has merit in so far as it confronts the two schools, so to speak, in order to see how they define

Euroscepticism, the type of data they use, its scope, and what explanations there are for it, with a concluding part on the actual salience of the question. His comparative method using definition, data/scope, explanations of Euroscepticism for the Sussex and North Carolina Schools will be applied to systematise the articles used for this review. The latter is also inspired by Cas Mudde’s question on the ‘so what?’ of Euroscepticism, asking for the issue’s actual salience in the overall European debate (Mudde, 2012, p. 199). Is it (still) a relevant issue? As we will see, these aspects have had a noticeable impact on the evolution of the discussion.

2.6 Euroscepticism as an evolving concept

As will become obvious in chapter 3, the prolific amount of writing on the subject has made it impossible to review the last twenty years of writing on the concept of Euroscepticism within the scope of this paper, which means that it became necessary to succinctly cover the

17 timespan in-between. The search process applied here also led to the discovery of several anthologies all bringing together well-versed researchers, with two major anthologies sticking out, in particular. Some of the top-cited articles are part of one of these collections, others are written by authors who appear on the same list of top-cited results. These two anthologies also contain updated conceptual discussions rather than merely using the concept as an instrument or a vehicle for empirically oriented studies, as a ‘function’ rather than as a ‘subject in its own right’ (Leruth, et al., 2018, p. 4). In our context, it is meant as a subject in its own right rather than an instrument. In my opinion, this paper would therefore not be complete without

highlighting these two works, the first one published ten and the second one twenty years after ‘Touchstone of Dissent’ (Taggart, 1998): Opposing Europe (Szczerbiak & Taggart, 2008) and

The Routledge Handbook on Euroscepticism (Leruth, et al., 2018). Although not all of the

articles mentioned here were rendered at the top of Google’s list, they are a result of the inductive reasoning used (see Chapter 3).

The introduction to the two-volume study Opposing Europe: The Politics of

Euroscepticism in Europe, edited by Aleks Szczerbiak and Paul Taggart (2008), the result of a

network project bringing together experts providing insights on Euroscepticism in party systems in EU countries, proposes an updated version of the dichotomy of soft and hard Euroscepticism, with the choice falling on parties as ‘key gatekeepers in the process of political representation’ (Szczerbiak & Taggart, 2008, p. 2). As updated classifications, they propose Kopecký & Mudde’s ‘Euroenthusiasts, Eurorejects, Eurosceptics, and

Europragmatists’ (2002, p. 303); Flood’s (2002, p. 5) of a spectrum from rejectionism through revisionism and minimalism to gradualism, reformism and maximalism; Conti’s (2003) functional and identity Europeanism as ‘positive corollaries’ of hard/soft

Euroscepticism, and Rovny’s (2004) ideological or strategic motivations for Euroscepticism (Szczerbiak & Taggart, 2008, p. 6). Volume 2 presents ten theory-building articles on the concept and evolution of Euroscepticism, four among which are part of the top thirty most cited articles on our search terms (cf. Chapter 3 of this paper). In the introductory article to volume 2, the same authors propose a number of questions: how to define

(hard-principled/soft-contingent) and measure Euroscepticism in party systems, but also what can cause it: institutional structures, ideology/underlying beliefs vs strategy/tactics, transnational party cooperation, and the varying expressions of the phenomenon in different countries. After a brief discussion of other, linked issues such as Euroscepticism in the European Parliament, in public opinion as well as the step-by-step enlargement of member states, they

18 conclude with the question of salience, i.e. the actual importance of the issue of ‘Europe’ for parties and their voters (Szczerbiak & Taggart, 2008, p. 2ff).

The more recent anthology Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism (2018) turns up as a top result of a year-by-year search on ‘Euroscepticism’ (cf. Chapter 3) and was intended to gather up-to-date input on the issue. In the first part, which deals with defining

Euroscepticism, the authors name the economic crisis from 2008, followed by terrorist attacks and the humanitarian crisis in 2015-16, as a reason to study Euroscepticism as an increasingly salient issue (Leruth, et al., 2018, p. 3). The authors point out that the question remains

whether ‘Euroscepticism is the source or the result of other attitudes’ (Leruth, et al., 2018, p. 5), a question that is, as pointed out earlier, one of the incentives behind this paper. Part 1 of

Handbook deals with conceptualizing and measuring Euroscepticism in an endeavour to deal

with these questions. In a conceptual discussion that covers the period up to that point, Vasilopoulou comes to the conclusion that the concept continues to be highly contested (Vasilopoulou, 2018, p. 26). In order to organize the available knowledge, she set out to do a structured literature review culminating in a meta-analysis of all articles written on the subject of Euroscepticism in 2014. As a result, she stated that we ought to look at the consequences and effects of Euroscepticism much more than we do, that we should use it as an independent variable to explain other occurrences rather than merely trying to explain its origins and causes (Vasilopoulou, 2018, p. 32). The wealth of available research reflects the growing number of member states and, ultimately, Brexit. But it also reflects the different, changing and sometimes volatile relationships that European citizens have had (and will have) with the European Union, and what consequences that will have for election results and what

consequences these election results in turn will have for the European Union. Vasilopoulou’s approach of a structured literature review leading to an update on recent articles will be applied to the present paper, therefore focusing on publications articles from 2018-2020.

19

2.7 Summary/checklist

2.7.1 Proposed starting points

Inglehart, Rabier & Reif (1987)• A difference between utilitarian aspects and affective support

• A difference between the attitude among older member states and newer ones • A difference between materialist/economic outlook and

post-materialist/socio-political aspects Mutimer (1989)

• The European Union as an intergovernmental federation • The European Unions as a neofunctionalist construct Taggart (1998)

• Corollary of European integration

• Contingent/qualified or outright/unqualified opposition • Soft or hard Euroscepticism

Hooghe, Marks & Wilson (2002)

• Contestation of European integration

• Extreme left and extreme right are Eurosceptic for different reasons • GAL/TAN as a better way to pinpoint party positions

2.7.2 Framework for analysis

Mudde (2012)• How to define Euroscepticism • How to measure Euroscepticism • How to explain Euroscepticism

• How salient/relevant is Euroscepticism Vasilopoulou (2018)

20

3 Research design and method

3.1 Research design

The purpose of this paper is to study the evolution of the concept of ‘Euroscepticism’ since 1986. The conflicting dictionary definitions as a first entry point to a conceptual discussion were a simple example of how definitions from sources deemed authoritative can colour one’s perception from the outset, shifting the latter from lack of enthusiasm to

opposition.5 As mentioned in the beginning of this paper, its first goal in terms of method is

therefore to operate inductively, meaning that, instead of proposing set definitions/

explanations of the concept against which we will test subsequent contributions to research, the penultimate question remains how the concept itself has evolved since 1986 and,

consequently, whether its definition and explanations are homogeneous or not. In a first endeavour to trace the origin of the concept of Euroscepticism OR Eurosceptic OR

Euroskeptic OR Euroskeptic as search terms, Google Scholar rendered approximately 30,200 results without a given timeframe.6 From this result, we may assume that Euroscepticism has

become an increasingly documented term. The comprehensive amount of material made it necessary to find an organising principle that fits the scope, timeframe and available person power of the project.

There is ample quantitative survey material available that can be used in order to attempt to identify and measure causes and effects of Euroscepticism, for instance voting behaviour in relationship with other aspects of life, which is done for instance by the Chapel

5 As a comparison, eurosceptic/euroscepticism is defined as follows in a very recent thematic dictionary by the

same publisher:

“Literally meaning a person, a political party, or group of people who are sceptical of the European Union and European integration. The range of euroscepticism can be a stronger anti-European position as well as more moderate positions against key aspects of the European project, such as the Economic Monetary Union, its bureaucratic engrossment, its lack of democratic legitimacy, or the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Euroscepticism can also act as a political platform for the establishment of a party (such as the United Kingdom Independence Party—UKIP).

Nevertheless, in the mainstream, the term ‘eurosceptic’ has come to signify strong opposition to the European Union, particularly with claims that it ‘erodes’ the self-determination and cultural uniqueness of nationality while also undermining state sovereignty. More recently, European rules governing the free movement of people have also attracted eurosceptic anti-immigration scrutiny with claims that free movement diminishes national unity and identity. Although euroscepticism has existed since the founding of the European Union, it has recently gained momentum politically, moving towards anti-Europeanism, as dramatically represented by the UK Brexit referendum to leave the EU, as well as similar campaigns in other EU member states such as France and Holland”. A Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics and International Relations (Oxford University Press, 2018)

21 Hill Expert Survey (Marks, et al., 2020), or using the European Social Survey, among many others. It is also possible to do a qualitative comparative case study of a small number of countries in the European Union in order to gain a deeper understanding of Euroscepticism in those, but that would probably fail to give a bigger picture of the conceptual discussion. A comparative case study encompassing all member states was a possible initial entry point, in which case a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) may have served as a method to investigate the effects of European integration and the development of Euroscepticism in member states, but it became obvious that this would require more time and involve necessary access to software. The advantage would have been the use of comprehensive survey data in order to survey cause, effects and possible correlations of Euroscepticism. However, knowing that the concept of Euroscepticism is quite recent, at least as used explicitly in research, and linked to a political integration project that, in fact, was created in modern time and constantly renews itself, there is merit in recapitulating, synthesising and understanding the research that has contributed to it in order to discuss the concept itself rather than studying it empirically. A systematic literature review was deemed appropriate to the purpose, since it may provide new insights and starting points for future analyses using an updated concept.

3.2 The systematic literature review in research

There are inherent risks in the choice of method. While it may have been surprising to some that the method has not become more widespread in the field of political science

(Dacombe, 2018, p. 148), others consider it a potential trap that even may lead to failure of an entire research project (Daigneault, et al., 2014, p. 267). The former argues against three criticisms, namely that of being ‘unhelpfully positivistic’, that it ‘undervalue[s] qualitative work’ and is ‘theoretically vacant’, and points towards the fact that authors bemoan the difficulty of having to handle growing quantities of material while seeing the pitfalls of bias inherent in purely qualitative assessment. The latter argue that, while the failed project referred to in the article in question led to valuable new knowledge, the methods born out of the ‘evidence movement’, with its roots in health care, have significant requirements in terms of focus, restricted scope, available time and understanding of the method, which may cause a project not to reach completion. In other words, there needs to be some awareness of the imposed practical limitations. It is therefore of tantamount importance for the present study to remind of its restricted size. Since one crucial aspect of the chosen method is reproducibility, much focus has been given to how to detect the material used.

22 There are different types of literature surveys applicable to different aims and topic areas, and its methods have been moving from ‘traditional’ reviewing to also comprising systematic reviewing, which is based on evidence-based practice, as used in medical research, for instance (Jesson, et al., 2011, p. 9) (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 16f). As discussed by Jesson et al., doing a traditional literature review does not necessarily entail a scientifically prescribed model or methodology, whereas a systematic review does (Jesson, et al., 2011, p. 10).

Although both methods are used to review existing knowledge in order to build on it, there is, as they call it, ‘a continuum’ of approaches in-between. While the traditional review tends to be critical, the systematic review intends to be neutral and wants to demonstrate objectivity and transparency (Jesson, et al., 2011, p. 14f). Although the traditional review also can be aimed at a conceptual discussion, delivering state-of-the-art information, expert knowledge or scoping a research field, they still are, according to the authors, based on a ‘personal

selection’ of materials (Jesson, et al., 2011, p. 15). In the present case, although this paper cannot in advance claim to deliver novel expert knowledge, its purpose is to deliver an update on available research and therefore also scope the field for available material, which all are presented as forms of traditional reviewing. But it can be argued that the method of systematic review both implies a neutral and transparent method for picking material and for analysing the material thus discovered or, as the authors put it, the reason and manner of a systematic review are different, but the review still builds on same necessities as a traditional one, i.e. detecting and presenting source material (Jesson, et al., 2011, p. 107).

‘A conceptual review aims to synthesise areas of conceptual knowledge that contributes to a better understanding of these issues’ (Jesson, et al., 2011, p. 15). Choosing relevant sources that study the concept would be easiest, but it would not suffice to paint the bigger picture. Since a major personal motivation for this thesis is to objectivize existing knowledge, there is a risk that the results of such a restricted review of conceptual research would lack both in validity (in terms of bias of choice and consequently in terms of findings) and reliability (in terms of usability for further research). As an example, Greenhalgh (2014) and Mulrow, et al. (1997) name college students leaving out material that doesn’t fit their ‘proposed theory’ so that ‘bias, or systematic error, may exist at the identification, selection, synthesis, analysis and interpretation stages of a review process’ (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 19). Instead, the idea that developed along the way was to apply the principles of a systematic literature review in order to grasp as much of the evolution of the concept of Euroscepticism as possible by following its development in primary sources, and to make it possible to use

23 the same procedure to subsequently deepen and broaden the investigation, since the scope of the thesis precludes an exhaustive review. According to Booth, Papaioannou & Sutton, a ‘literature review as part of a dissertation or thesis should be innovative’, students ‘reflexive about their methods’ and ‘demonstrate their growth through the methodology’ (2016, p. 12f) quoting McGhee, et al. (2007) and Daigneault, et al. (2014). The authors also quote that students are ‘expected to demonstrate their knowledge about a particular field of study, including vocabulary, theories, key variables and phenomena, and its methods and history’ (2016, p. 12), quoting Randolph (2009), as well as ‘demonstrate that they are sensitized to the ‘influential researchers and ‘research groups in the field’ and that the thesis subsequently ‘may become a legitimate and publishable scholarly document’ (2016, p. 12) quoting LeCompte, et al. (2003). Also, ‘clarity, validity and auditability’ are named as crucial considerations (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 19). I use this as an argument to apply the method although it must be used in reduced size in the present context. The term ‘semi-systematic’ is therefore chosen with due caution.

Hence, with all available research at hand, the review will have to be drastically narrow in focus, but it is still intended as a systematic review of research. On the one hand, the restricted practical scope of the task at hand (single researcher, limited timespan) would make it difficult to process a sufficiently large number of books and papers to dare attempt a full-fledged systematic review of Euroscepticism from the origin to the present day. On the other hand, as discussed, it would not seem satisfactory to present a more traditional

exploration of a field that has grown exponentially under the last few decades on the basis of mere personal preference, which is why this review will attempt to apply a proper systematic method, albeit in restricted format. According to Jesson, et al. (2011), a systematic review must have:

o A tightly specified aim and objectives, with a specific review question o Narrow focus

o Transparent process and documented audit trail o Rigorous and comprehensive search for ALL studies o Predetermined criteria for exclusion and inclusion o Checklists to assess quality

o Analysis and synthesis in tabular format

24 Aside from personal curiosity, the underlying motivation is to identify possible

avenues for the future and to observe and understand how Euroscepticism may impact on European politics in the future. Therefore, the proposal is to look at research published since 1986 and to conclude with articles close to the present day, even more since 2020 is the year after the most recent European Parliament election, and to select material following the proposed criteria. Between the ambition to operate within a post-positivistic framework in order to deliver systematic data and control for research bias, on the one hand, and the desire to operate in a socially constructivist framework in order to deliver data that by needs will account for multiple realities, the choice fell on a more pragmatic framework instead. See e.g. Creswell & Poth (2018) for a comparison of interpretative frameworks and philosophical beliefs (2018, p. 34f).

3.3 The best fit framework

The best fit framework, described by Booth, Sutton & Papaioannou (2016), begins with a ‘good enough’ framework, ‘populating it with as much of the data as possible without forcing the data to fit’. After this initial phase, which is deductive, the ‘remaining data’ is gathered inductively, and thereby ‘creating new themes until all the data are processed’ (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 228). According to the authors, ‘framework-based synthesis is an important advance in conducting reviews of qualitative synthesis’ and ‘the ‘best fit’ strategy is a variant of this approach that may be very helpful when policy makers, practitioners or other decision makers need answers quickly’ (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 229). That is the reason for the theoretical background proposed in Chapter 2 which, on the one hand, can rightfully be questioned for representing an a priori subjective choice of material, i.e. the use of Inglehart, et al. (1987), Mutimer (1989), Taggart (1998), Hooghe, et al. (2002), Szczerbiak & Taggart (2008), Leruth, Startin & Usherwood (2018), and hence following a traditional method. I argue, nevertheless, that they all were discovered during the inductively conducted search, but I chose the ‘best fit’ strategy of proposing the seminal research identified before presenting the detected relevant articles, as can be seen from Booth’s proposed steps for applying a best fit framework, and their application in the present paper.

25 Booth & Carroll (2015, p. 702) (Google, 2020)

Chapter 1

How is Euroscepticism defined? How is Euroscepticism explained? What data is used (scope) and how (what type of study)? Chapter 2

(a) Identify seminal articles on the topic

(b) Identify best fit publications

Chapter 3 (a) Extract data on study characteristics and appraise quality

(b) Generate a priori framework

Chapter 4 Present all articles using the same framework

Chapter 5 Create new themes

Chapter 5

Produce new framework

Revisit evidence (excluded in this thesis)

Best-fit framework as proposed by Booth & Carroll and its application to this paper

3.4 Choice of data source

According to Google’s information on ‘About Google Scholar’, the database ‘aims to rank documents the way researchers do, weighing the full text of each document, where it was published, who it was written by, as well as how often and how recently it has been cited in other scholarly literature’ (Google, 2020). Its aim is to provide a tool for broad searches and access to recent material, both online and by facilitating necessary orders of physical copies

26 via library services.7The wide choice of accessible journals, the fact that it facilitates access

to non-electronic copies of older articles via University cooperation networks and its mechanism to evaluate the quality of articles give reason to use Google Scholar as the exclusive source for the scope of this paper. This does not mean that it is the only electronic source of information, but it is deemed sufficiently broad and thorough for the present survey. Since one aim of the methodology used is that it should be reproducible, a subsequent

worthwhile step can (and ought to) be an iteration of the same process using other databases such as Web of Science. In this case, the articles gathered covering the period 1998-2017 are the top thirty number of citations in Google Scholar whereas the recent articles (2018-20) are taken as is, following the example of Vasilopoulou (2018).

3.5 Search strategy

As Booth, Sutton & Papaioannou (2016) argue, complex interventions will require iterative processes with the aid of databases as well as other processes, such as ‘citation searching’ (Levay, et al., 2015), ‘reference list checking’, ‘snowballing’ and ‘hand searching’ (Greenhalgh, et al., 2005) and that that is how a scoping search ought to be carried out for such a purpose, according to Booth, Sutton & Papaioannou (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 114). The objective is to refine the research question and review strategy to make the amount of material manageable and still ‘exhaustive’ while ‘sensitive’ to the research question. Otherwise, the risk may be to exclude or include the wrong material or simply exclude too much or too little. The present paper will need to exclude the iteration because of its limited scope, but the evidence thus gained can be revisited and extended using the same principle. Its starting point is to be exhaustive while sensitive. Following the principle of best fit framework, the idea was to detect seminal contributions as a conceptual pilot light for the subsequent literature. The underlying risk is that this can entail selection bias in a scientific study that hence may leave out essential studies while including others, less essential, if the selection is not conducted systematically (Booth, et al., 2016, p. 142ff). It was therefore important to detect valid sources as entry points. As put by the same authors, this requires a ‘quality assessment’ for internal

validity (can we ‘believe a study’), external validity (‘is the study relevant to the population

identified by our research question?’), reliability (‘what are the results’), and applicability

7 The index used, called H5, is ‘the H-index for articles published in the last 5 complete years. It is the largest

number h such that h articles published in 2014-2018 have at least h citations each’ (Google Scholar Citations 2020).

27 (‘can we generalize the results’), for all articles that will result from a search, and articles considered seminal, in particular. If the framework articles initially proposed do not meet the necessary criteria, this will impact on the analysis of the ‘best fit’ articles. In epistemological terms, prescribing the ‘wrong’ set of articles will have an impact on what other articles subsequently are included or excluded, while the aim of the method is to detect what articles there are.

3.6 Search process

On Google Scholar, Euroscepticism OR Eurosceptic OR Euroskepticism OR Euroskeptic as search terms without any set period results in approximately 32,400 results without timeframe. The first and only valid result for the search term ‘Euroscepticism’ up to 1986 is a book by Norwegian diplomat Tore Nedrebø, Whence Europe (2010, Kindle

Edition), which also remains the only valid/validly dated search result until 1990.8 In the

absence of articles on Euroscepticism, a search for ‘European integration’ for the same period (1986-1990) rendered 2,890 results. When searching for ‘European integration’ and ‘parties’ without timeframe, the number one result over time is Hooghe, et al.’s ‘Does left/right structure party positions on European integration’ (2002) (1,741 citations), which is why it was chosen as a seminal article for Chapter 2. Between 1991 and 1996, there were 45 results when searching for ‘Euroscepticism’ OR ‘Eurosceptic’ OR ‘Euroskeptic’ together with the earlier combination, and only three when adding ‘left-right'. That explains why the top 10 list contains 8 articles from that timespan and one from 1997 (most of the top 100 are from that same period). The issue of Euroscepticism in research seemed to be taking off after the

European Parliament election of 1994, although a combination with the aspects of integration, Parliament and parties only accounts for less than half of references to Euroscepticism by the year 2000. Web of Science, used for confirmation, has its first hit 1998 and that is the same as Google Scholar, i.e. Taggart’s ‘A touchstone of dissent’ (1998). Therefore, this seminal article by Taggart (together with his article on populism) was also used as a starting point for

Chapter 2. However, it became obvious at that point that a choice had to be made in order to produce a more manageable number of articles. It seemed logical to focus on

8 Whence Europe goes back to the author’s graduate thesis from 1986 and a subsequent dissertation on the same

subject from 2010. It is excluded from the list of publications since it is neither a peer-reviewed research paper nor a chapter of an edited research volume on the subject, but its historical perspective makes it a valuable read on and a personal reflexion on ‘the curious divide in attitudes to ‘European integration’ (Nedrebø, 2010, Kindle Edition, p. 128 Kindle Location).

28

‘Euroscepticism’ as part of the title in order to exclude articles dealing with other issues, albeit using the term as a ‘function’ for something else rather than a ‘subject in its own right’

(Leruth, et al., 2018, p. 4), and (following the same principle) ‘party’ in order to produce results dealing with party-related issues instead of popular Euroscepticism.

After a thorough whetting process searching year by year in order to see the

development of the number of articles over time, articles without peer review, academic exam papers, book reviews, faulty links and articles unavailable either online or offline, the list was shortened from 187 to 79 articles. It also became obvious that a number of these articles are book chapters. Chapters belonging to edited anthologies were kept since they gather articles that are whetted following similar processes as those of research journals. Chapters belonging to single-author books were discarded (with the exception of some references to Nedrebø’s

Whence Europe since it had a seminal impact on this paper), as it would be beyond the scope

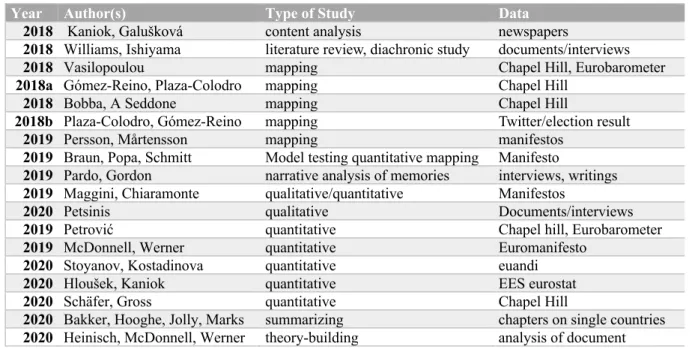

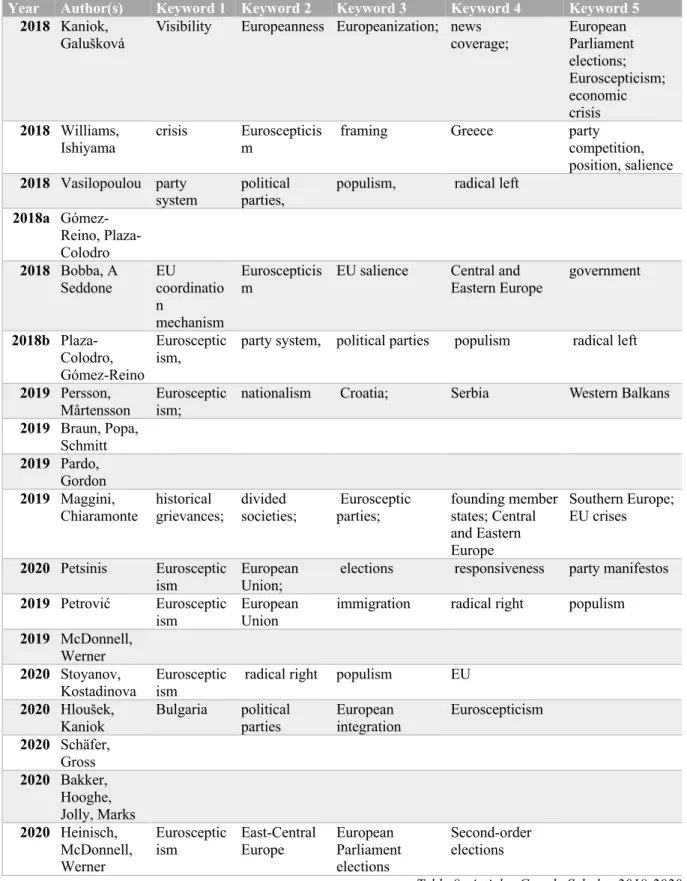

of this article to review these. It can also be noted that a search following the same parameters had very similar results in Web of Science, but I made a pragmatic choice to stick to Google Scholar. Following Vasilopoulou’s example (2018), the 30 top-cited articles from the period 1998-2017, which amount to 49 % of 61 articles, are dealt with in the first section of the following chapter. The three most recent years (2018-2020), which rendered 18 articles deemed qualified for this study following the same principle as above, are dealt with in the second section of the following chapter.

4 The evolution of the concept of Euroscepticism

4.1 Euroscepticism 1998-2017

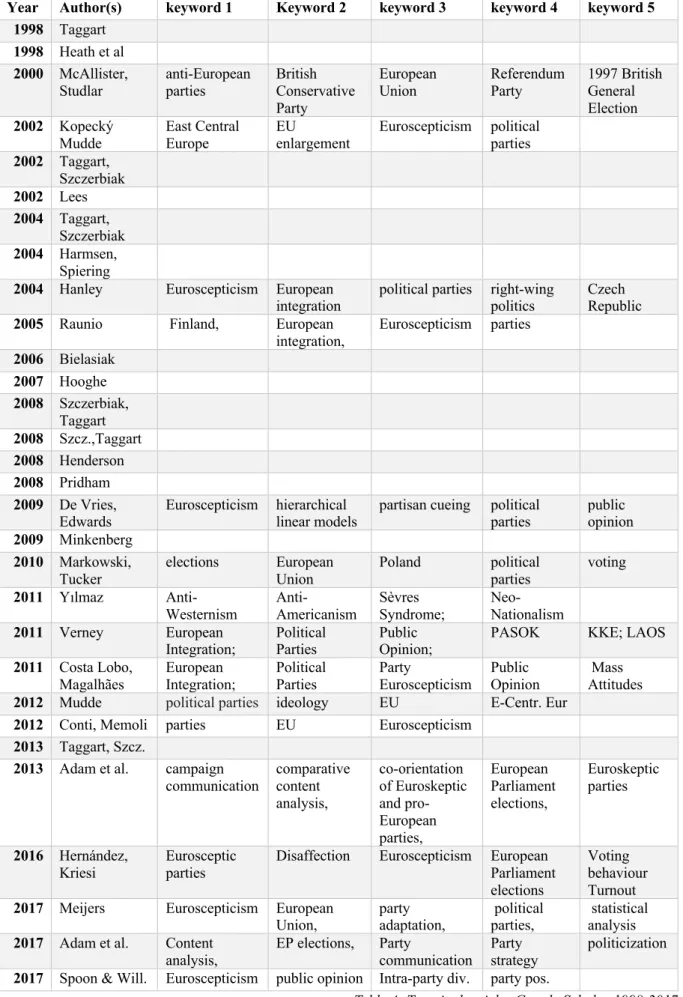

The table on the following page contains the 30 top-cited articles on Google Scholar 1998-2017, which were read with an extremely narrow focus on measuring (scope/type of study/sources used) and definition/explanation of Euroscepticism. The evolution of the concept of Euroscepticism was traced by means of the definition that is given/used in each publication. Scope, type of study and data used are presented in table format, explanatory key

29 terms for future study likewise. As a reminder, it should be noted that the expression ‘EU members’ refers to different groupings depending on when the article was published. 9

Year Author(s) Journal/Publication GS WS

1998 Taggart European Journal of Political Research 1242 351

2002 Kopecký, Mudde European Union Politics 912

2009 De Vries, Edwards Party Politics 496 196

2004 Taggart, Szczerbiak European Journal of Political Research 419 136

2008 Szczerbiak Taggart Opposing Europe 400

2007 Hooghe European Union Politics 192 54

2004 Harmsen, Spiering Euroscepticism: party politics, national

identity and European integration (book) 179

2013 Taggart, Szczerbiak JCMS: Journal of Common Market 128 42

2017 Meijers Party Politics, 113 46

2002 Taggart, Szczerbiak Perspectives on European Politics and

Society 84

2002 Lees Political Studies 82 8

2011 Yılmaz South European Society and Politics, 78 30

2012 Mudde East European Politics 74 24

2010 Markowski, Tucker Party Politics 73 19

2004 Hanley East European politics and societies, 71 19

2009 Minkenberg West European Politics 68 23

2008 Szczerbiak, Taggart Opposing Europe 63

2012 Conti, Memoli Acta Politica 56 20

2011 Verney South European Society and Politics, 52 20

2006 Bielasiak Public Opinion, Party Competition, and the

European Union in Post-Communist Europe 50

2008 Henderson Opposing Europe 46

2008 Pridham Opposing Europe 46

2016 Hernández, Kriesi Electoral Studies 45 15

2000 McAllister, Studlar Party Politics 43 15

2011 Costa Lobo, Magalhães South European Society and Politics 38 14

2005 Raunio T Journal of European Integration 37

2017 Adam, Antl-Wittenberg, Eugster European Union Politics 35 17

1998 Heath, Jowell, Taylor British Elections & Parties 33

2017 Spoon, Williams West European Politics 28 15

2013 Adam, Maier, de Vreese Journal of Political Marketing 20

Table 1: 30 top-cited articles Google Scholar 1998-2017 Euroscepticism and parties

4.1.1 How Euroscepticism is measured and explained

In keeping with the method proposed in Chapter 3, these results are presented in tabular format, first in order of scope, then following type of study and data source, and finally the key terms proposed (consisting of keywords chosen by the authors for journal articles, which is not the case for book chapters).

9 EU members in order of accession: BE, FR, DE, IT LU, NL (1958); DK, IE, UK (1973); EL (1981); PT, ES

30 In terms of scope, we can see that approx. 1/3 of the articles have EU as their scope, approx. 1/3 are single-case and approx. 1/3 comparative case studies, with a noticeable focus on acceding countries as opposed to founding members.

Year Author(s) SCOPE

2013 Adam, Maier, de Vreese AT BG CZ DE HU NL PL PT ES SE UK

2013 Taggart, Szczerbiak AT CY CZ EE DE HU IE IT NL PL SE UK

2004 Harmsen, Spiering AT DE FR UK IE NL SE CZ PL CH

2017 Adam, Antl-Wittenberg, Eugster AT FR DE GR NL PT UK

2002 Taggart, Szczerbiak BG CZ EE HU LV LT PL RO SK SL 2004 Taggart, Szczerbiak BG CZ EE HU LV LT PL RO SK SL 2008 Henderson BG CZ EE HU LV LT PL RO SK SL 2006 Bielasiak BG CZ EE HU LV LT PL RO SK SL 2008 Pridham BG HU, CZ, SK, RO 2002 Kopecký Mudde CZ, HU PL SK 2008 Szczerbiak, Taggart EU 2007 Hooghe EU 2009 Minkenberg EU 2012 Conti, Memoli EU 2016 Hernández, Kriesi EU 2017 Spoon, Williams EU 2009 De Vries, Edwards EU 2008 Szczerbiak, Taggart EU 2012 Mudde EU

1998 Taggart EU member states and Norway

2017 Meijers EU Western 2004 Hanley CZ 2002 Lees DE 2005 Raunio FI 2011 Verney GR 2010 Markowski, Tucker PL

2011 Costa Lobo, Magalhães PT

2011 Yılmaz TR

2000 McAllister, Studlar UK

1998 Heath, Jowell, Taylor UK

Table 2: Top-cited articles Google Scholar 1998-2017 Euroscepticism and parties in order of scope

In terms of study type, it was difficult to be consistent in a description since many articles use more than one method. But most of them are mapping, and they therefore use election data, party manifestos or the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, while introductory book chapters per force summarize the content of the chapters of the publication, which quite probably is a reason for their high result in terms of searches.