Sports sponsorship in Poland:

A comparative study of companies’ sponsorship processes

Dorota Celczynska

Sport Sciences: Sport in Society Two-Year Master

30 credits 4/2020

Abstract

Sports sponsorship has become a global and multi-billion dollar business. It is an integral part of the company's marketing strategy and viewed as a highly effective form of advertising. Clearly, companies have understood the value of sponsorship for their marketing portfolio and aim to build brand awareness, image, customers’ and

employees’ loyalty, and generate higher revenues. However, previous research has shown that the potential of sports sponsorship is still not sufficiently used in Poland. Companies in this country lack knowledge and awareness about the sponsorship of sporting events.

The purpose of this study is to analyze differences and similarities between

companies' sponsorship processes that sponsor local, national, and international sporting events in Poland. It includes exploring sponsorship promotional activities, objectives, selection criteria, as well as decision-making procedures followed by businesses in the sponsorship exchange process.

A qualitative comparative study consisting of 19 interviews with representatives sponsoring sporting events in Poland was used.

The results revealed that sponsorship processes vary depending on the level of the sponsored sports event. As the level increases from local to national or international, companies adopt more profit-oriented goals and decisions.Whereas companies

sponsoring local sporting events often based their choices on emotions and sympathy to sports disciplines or event organizers. Furthermore, the results also suggested that there is a significant difference between the decision-making procedures of companies involved in sponsoring different levels of sporting events. As the event level rises, it becomes more complex, considered, and longer.

In summary, the study shows that companies in Poland recognize event sponsorship as an efficient way to create brand and product image. Although the study also

discovers that the role of event sponsorship as a communication tool to achieve commercial goals is not seen by some corporations as a key aspect of strategy.

Table of contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 5

1.1 BACKGROUND ... 5

1.2 RESEARCH PURPOSE AND QUESTIONS ... 7

1.3 PROBLEM DISCUSSION ... 8

2. PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 10

2.1 SPORTS MARKETING ... 10

2.2 SPORTS SPONSORSHIP ... 11

2.3 SPORTS SPONSORSHIP IN POLAND ... 17

2.4 SPORTS SPONSORSHIP OBJECTIVES ... 20

2.5 SPORTS SPONSORSHIP SELECTION CRITERIA ... 23

3. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 25

3.1 DECISION-MAKING THEORIES ... 25

3.2 SPORT SPONSORSHIP ACQUISITION MODEL ... 28

3.3 EXCHANGE THEORY ... 30

4. METHODOLOGY ... 34

4.1 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 34

4.2 DATA COLLECTION TECHNIQUES ... 36

4.3 EMPIRICAL DATA ... 37

4.4 METHODS OF ANALYSIS ... 39

4.5 SCIENTIFIC CONSIDERATION ... 41

4.6 ETHICAL CONSIDERATION ... 43

4.7 SOCIAL CONSIDERATION ... 44

5. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS ... 45

5.1 SAMPLE SIZE ... 45

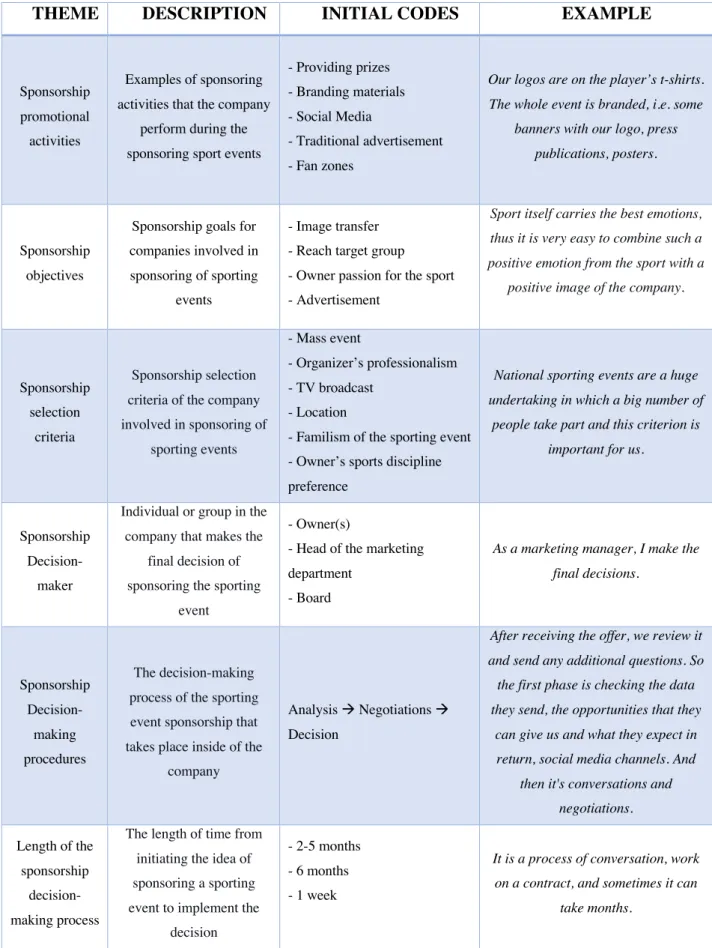

5.2 THEMATIC ANALYSIS ... 46

5.2.1 Companies sponsoring local sporting events ... 47

5.2.2 Companies sponsoring national sporting events ... 54

6. CONCLUSIONS ... 69

6.1 SUB-QUESTION 1:WHAT ARE THE MAIN MOTIVES PRESENT WHEN COMPANIES DECIDE TO ENGAGE IN THE SPONSORSHIP OF SPORTS EVENTS IN POLAND? ... 69

6.2 SUB-QUESTION 2: WHAT ARE THE COMPANIES’ SELECTION CRITERIA WHEN DECIDING WHAT SPORTS EVENT TO SPONSOR IN POLAND? ... 72

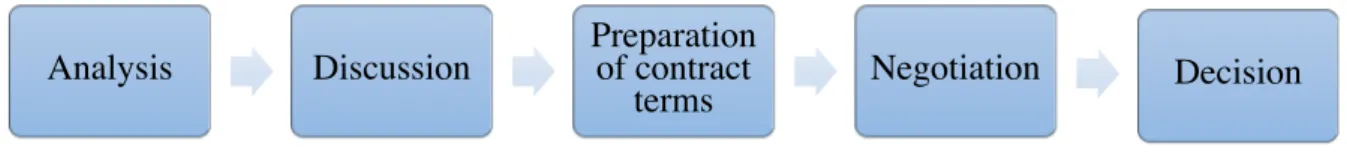

6.3 SUB-QUESTION 3: WHAT ARE THE DECISION-MAKING PROCEDURES FOLLOWED BY COMPANIES INVOLVED IN THE SPORTS EVENT SPONSORSHIP IN POLAND? ... 74

6.4 MAIN RESEARCH QUESTION: IN WHAT WAY ARE SPONSORSHIP PROCESSES DIFFERENT OR ALIKE FOR COMPANIES THAT SPONSOR POLISH SPORTS EVENTS AT LOCAL, NATIONAL, AND INTERNATIONAL LEVELS? ... 76

7. DISCUSSION ... 80

7.1 REFLECTION ON THE THESIS PROCESS ... 80

7.2 IMPLICATION FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 84

7.3 RECOMMENDATIONS ... 85

REFERENCES ... 87

APPENDICES ... 94

APPENDICES 1:COMPANIES OVERVIEW ... 94

APPENDICES 2:INTERVIEW GUIDE FOR THE SPONSORING COMPANIES ... 95

APPENDICES 3:INTERVIEW GUIDE FOR THE SPONSORING COMPANIES.POLISH VERSION ... 96

APPENDICES 4:CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE IN THE STUDY ... 97

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the chosen topic, illustrating the foundation of the thesis. The background is followed by research purpose, research questions and problem discussion.

1.1 Background

The popularity of the sport has grown rapidly worldwide in the last decades. In 2015 the global sports industry was measured to be worth US $145 billion, which accounts for over 3% of the world’s economic activity (Manoli, 2018). The emergence of the digital age has increased with the development of the sports industry. Consequently, the role of marketing in the sports industry has developed enormously during the last forty years, and researchers have more often become interested in sport marketing and management (Fetchko, Roy & Clow, 2013).

Consecutively with the development of the sports industry, management, and

economy, more than ever, sports events have started to dominate the professional sports world. Sports events give authentic insight and create levels of emotions barely seen in other event forms (Gammon, 2011). Moreover, sports events produce mass media interested and can assist in place-marketing initiatives (Gammon, 2011). Since the renewal of the Olympics at the end of the nineteenth century, the Olympic Games appear as the world’s greatest sporting event (Chalkley & Essex, 1999). Over time, other, equally big and famous sports tournaments have been created. It includes, for instance, UEFA Champions League, FIFA World Cup, and The Super Bowl. Events are divided into mega sports events, hallmark sports events, sports heritage, parades and festivals, and small-scale/community sports events (Gammon, 2011; Schwarz & Hunter, 2008).

In the face of growing competition on the sports market and development of sports events, it is necessary to consolidate the brand, service, or product in the minds of customers. There are many tools that companies use to run advertising and marketing campaigns. However, due to the growing knowledge and awareness of customers, television advertising, and other forms of advertising of the company and its products are becoming less effective (Krasucki, 2016). Thus, the companies look for new image building tools. An example can be sponsorship, which is one of the integral parts of

marketing. Over the past years, sponsorship has evolved from a small-scale activity in a limited number of industrialized countries to a major global industry receiving

significant investment (Walliser, 2003). The global sponsorship spending was

determined as $53.3 billion in 2013, which was twice as much as ten years ago (Demirel & Erdogmus, 2014). The growth and popularity of sponsorship are still on the rise, and sports sponsorship leads it. Currently, sporting organizations and events depend on sponsors who provide funds, products, and services. According to a new report, the US business spending on sports sponsorship will increase by 5.4% in 2020 (Fisher, 2019). One of the reasons for the dominance of the sport in sponsorship is that marketing changed as a global activity, and international companies need to communicate with their target markets in various languages, and sport can go beyond borders (Demirel & Erdogmus, 2014).

Sponsorship is an essential and developing source of sports support also in Poland. The sports industry and marketing have professionalized and increased in recent years (Sponsoring Insights, 2018). As more successes and new sports disciplines start to appear, it brings not only the eagerness to sponsor the polish sport but also creates the possibility for long-term relationships with given sports, clubs, and events (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Despite the stable growth of the market value, Poland’s expenditure on sports sponsorship is still small compared to many other European countries (Sponsoring Insights, 2018). In Sweden or Norway, companies invest in sport two to three times more than in Poland, wherein in Germany and Great Britain, the difference is much greater (Sponsoring Insights, 2018). What is more, there is still a lack of funds and resources to build stable financial support for all Olympic and non-Olympic disciplines (Kończak & Jedel, 2019). Sports associations, clubs, and sport event organizers face financial problems, and the Ministry of Sport and Tourism

resources in Poland are among the smallest in the government budget (Kończak & Jedel, 2019). Hence, athletes, sports organizations, and event organizers need to look for new sources of financing. Here sports sponsorship can be a solution not only for sports entities to obtain funding but also for companies that financially support the initiative and, thus, improve the company’s image. Although in Poland, sports sponsorship is not a primary field of corporate communication, and many companies are still not able to sufficiently utilize it (Kończak & Jedel, 2019).

The researchers define sponsorship as a business-to-business relationship between a sponsor and a sports entity for ordinary profits (Farelly, Quester & Greyser, 2005). Furthermore, researchers focus more on the relationship between the sponsors and the sponsee, sponsorship objectives, and decision-making processes. Since the sponsors invest a tremendous amount of money on sports sponsorship, they must have a clear objective of sponsorship (Lee & Ross, 2012). Therefore, understanding and

investigating decision-making processes and ‘how’ sponsoring decisions arrived rather than ‘what’ company can get from sponsorship is important for sponsors' success.

1.2 Research Purpose and Questions

The purpose of this study is to analyze differences and similarities between

companies' sponsorship processes that sponsor local, national, and international sporting events in Poland.

Therefore, the research topic of the master thesis, first of all, considers sports sponsorship during the sports events. Furthermore, the study focuses on sports

sponsorship in the polish market. Moreover, it also concentrates on the decision-making processes, which include sponsorship promotional activities, objectives, selection criteria, and decision-making procedures from the sponsor's point of view. What is more, the thesis considers sports events on international, national, and local levels. Lastly, it is crucial to outline that the thesis will not include any company financial calculation relating to any sports sponsorship as it will focus solely on strategy-based sponsorship and goals.

In order to investigate the different sponsorship processes between diverse polish sponsors engaged in sport event sponsorship, the following main research question will be asked:

In what way are sponsorship processes different or alike for companies that sponsor Polish sports events at local, national, and international levels?

The following sub-questions are specified to understand better the problem statement and support and enrich the final findings:

What are the main motives present when companies decide to engage in the sponsorship of sports events in Poland?

What are the companies’ selection criteria when deciding what sports event to sponsor in Poland?

What are the decision-making procedures followed by companies involved in the sports event sponsorship in Poland?

1.3 Problem Discussion

The topic of sport sponsorship processes and sponsoring companies is highly relevant. Sports sponsorship is becoming more complex, as more organizations and sporting events are being created. Further, sports sponsorship is today a common marketing strategy within companies. It has led to the need for sponsorship research, including activities such leas planning and setting goals, selection, and evaluation for sponsorship programs (Olkkonen, 1999).

However, still, little research has examined the sponsorship goals and how sponsorship engagement is beneficial to a company and its brand (Cornwell, Roy & Steinard, 2001). Moreover, it should be noted that there is a great value in sport sponsorship; however, to use it adequately, it needs implementation in all sponsor’s marketing activities.

Additionally, the sponsorship processes are getting more challenging for sponsors due to the rapid development of sport sponsorship. The lack of this research cause that the majority of companies enter the sponsorship without any clear and formal objectives in mind even though they might have the best intentions (Fahy, Farrelly & Quester, 2004). Besides, many sponsorship investments fail because companies do not maintain their investments with adequate advertising, public relations, and other promotional expenditures (Fahy et al., 2004).

What is more, a large part of the sponsorship literature concentrates on large

corporations and international events. However, the possible goals and strategies of the small and medium businesses sponsoring small or regional events can also be unusual and impressive (Dolphin, 2003). Thus, the thesis might discover sponsorship aspects yet to be considered by scholars as the research includes big companies that sponsor

international events, and also small organizations that engage in a local and national sports event.

Moreover, the thesis can show that the degree to which the sport sponsorship is used as a marketing communication tool may vary for companies that sponsor sporting events on different levels. The current research focuses only on two of them –

established (Walliser, 2003). When taking into account local events and smaller companies, these goals could have been less critical, while the importance of others such, as patriotism, may increase.

Lastly, the thesis includes sports sponsorship in Poland. Based on the review of the existing literature, it can be observed that there is little knowledge about sport

sponsorship in Poland, and it is based on the whole rather than case-oriented analysis (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Thus the study can additionally explore many aspects regarding sponsoring companies, their sponsorship goals,

2. Previous Research

The previous research aims to provide a comprehensive discussion and foundation of the sports marketing, sports events sponsorship worldwide and in Poland, sponsorship objectives, and the selection-making processes.

2.1 Sports Marketing

Marketing is a big part of people’s lives and becomes an essential concept of businesses, institutions, and events. There is often uncertainty what marketing means (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008), however, according to the American Marketing Association, it is ‘Planning executing the conception, pricing, promoting and distribution of ideas,

goods, and services to create exchanges that satisfy individual and organizational objective’ (Kaser & Oelkers, 2008, p. 4). In short, marketing is a clear business activity.

Nevertheless, some argue that marketing components, such as pricing, promotion, distribution does not entirely explain what marketing is, as they act to improve the use of marketing elements (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008). Moreover, the exchange included in the definition may refer to a client that gives away something – usually money, for a product or service of equivalent or higher value (Smith, 2008). According to Drucker, marketing aims to make selling redundant and to know and understand the customer so well that the product suits him and sells itself (Bernstein, 2015, p. 2).

When it comes to sports marketing, the origins go back to the 1860s when many companies realized the popularity of an emerging sport – baseball and began to use team photographs to trade their products and services (Bernstein, 2015).

Sports marketing has two essential characteristics. The first one is the use of general marketing methods for sport-related goods and services (Smith, 2008). Second, it is the marketing of other customers and industrial products or services through sport (Smith, 2008). Similarly, as general marketing mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, the sports marketing aims to meet the needs and wants of customers. However, it is

accomplished by giving sports services and sport-related products to customers (Smith, 2008). Undoubtedly, sports marketing is everything that happens off the field or court and builds the connection with fans through special events, endorsements, licensing, and brand awareness (Bernstein, 2015). In 1979, Parkhouse and Urlich addressed that sports marketing was shown next to merchandising and sales as a developing

sport-related field, which, however, is considered to be a mere commercial, promotional tool (Manoli, 2018). A few years later, Meenaghan proposed extending the marketing communications mix by arguing that commercial sponsorship can be recognized as one of its elements (Manoli, 2018). Since then, sports marketing was no longer shown as a business tool, but rather as a broader umbrella of promotional components that cover features such as commercial sponsorship, advertising, and publicity (Manoli, 2018).

As mentioned briefly earlier, sports marketing has two angles – sports marketing of sport and sports marketing through sport (Smith, 2008). The first one means that sports products and services can be advertised directly to the customer. Here the marketing can involve sporting equipment, professional competitions, sports events, and local clubs as well as the sale of season tickets and team advertising (Smith, 2008). Sports marketing though sport determines that non-sport products and services can be exchanged through sport (Smith, 2008). An example can be a professional athlete supporting a breakfast cereal or a beer company planning to have exclusive licenses to provide beer at the sports venue or event (Smith, 2008).

Since its emergence in baseball in the nineteenth century, sports marketing has become a billion-dollar industry. Nowadays, the purpose of sports marketing is not only to meet the needs and wants of consumers but also to reach the goals of the company concerning their mission and vision as well as to stay in the lead of the competition to maximize the product’s and company’s ability (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008). What is more, marketers recognize the popularity of sports and have made them a central point of marketing campaigns for decades (Bernstein, 2015). For instance, Budweiser spent $3 million on its Super Bowl ads alone in 2014 (Bernstein, 2015). As long as sports remain to fascinate millions of people, they will continue to be top events in which to deliver advertising messages.

2.2 Sports Sponsorship

Sponsorship has become an integral part of sports marketing. The history of sponsorship dates back to ancient Greece, where the first academic work defined the input of sponsorship to the development of private-public finance and the political economy (Johnston & Spais, 2015). In 776 BC, the first Olympic Games took place as a celebration of the achievement of the human body. Prominent Greek citizens and local authorities provided financial support to the organization of the Olympic Games

(Schwarz & Hunter, 2008). By this, they wished to improve their standing and

reputation, thus creating awareness and image, which made the Olympics a commercial event (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008).

What is more, sport has evolved from being a mere means for people to spend their leisure time into a tremendous industry (Radicchi, 2004). Nowadays, sport meets a variety of human physical and entertainment needs and provides an attractive way for global companies to reach a broad public (Radicchi, 2004). Sponsorship in modern understanding began in the second half of the nineteenth century with the development of mass media (Iwan, 2010). One of the first sports sponsorship deals dates back to 1902 when Slazenger became the Official Supplier of tennis balls to The

Championships at Wimbledon (“Wimbledon tennis balls - Slazenger Heritage shop, house of legends”, n.d.). Another breakthrough moment of sports event sponsorship was at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, where Coca-Cola became the Official Olympic Supplier sending 1,000 cases of Coke with the American athletes (Hepburn, n.d.). Coca-Cola is considered as one of the most popular sponsors in sport, alongside with Pepsi and Red Bull (“The Top 8 Most Popular Sponsor Brands in Sports |

FinSMEs”, 2019). However, the largest development of sponsorship occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, when sponsorship has become an increasingly popular form of promotion (Iwan, 2010). Peter Ueberroth – the President of the Los Angeles Olympic Committee 1984 saw the Olympics as an event that should be cost-effective (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008). He had a vision of creating a financially successful Olympic Games that would be in stark contrast to the spending deficit of most host cities involved (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008). Thus, Peter Ueberroth cooperated with USOC (United States Olympic Committee) and IOC (International Olympic Committee) to allow the application of the Olympic symbols by companies in their promotions in exchange for financial support (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008). Another reason for the rapid development of commercial sponsorship was due to the prohibition of cigarette advertising on television and radio introduced by the United States Congress (Meenaghan, 1991). Several other

governments have also limited tobacco and alcohol advertising (Meenaghan, 1991). Hence, the companies that sold these products had to look for new ways of advertising their goods, and one of them was by the sponsorship of sporting events. Further, the research explains that the rapid development of sport sponsorship can also be caused by governments’ inability to sustain financing sport to the necessary level maintain its

to make up the deficiency (Beech & Chadwick, 2013). Lastly, the literature presents that the inefficiencies of existing media, rising costs of media advertising, as well as new opportunities generated by increased leisure time, are also the reasons of the development of sport sponsorship worldwide (Beech & Chadwick, 2013; Hoek, Gendall, Jeffcoat & Orsman, 1997).

The development of sponsorship is impressive. The global sponsorship spending was £15.7 billion during 2002, an increase of £12.6 billion over the past ten years (Beech & Chadwick, 2013). Moreover, the statistics show that the sponsorship market is the most developed in North America, right after there are Europe and the Asia-Pacific region (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). In the 1990s, the USA spent on sponsoring and promotional purposes approximately EUR 1.23 billion, and in 2000 they reached EUR 9.3 billion (Iwan, 2010). World sponsorship has grown in recent years, on average 4% per year, and the dynamics of increase in outlays are similar to the one observed in advertising (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Moreover, the research demonstrates that around 70% of all sponsorship investments worldwide are allocated to sports events (Krstić & Durdević, 2016). It is not a surprise as sports event sponsorship attracts media attention worldwide (Krstić & Durdević, 2016). Hence, it is assumed that the investment in sport event sponsorship will continue to develop with expected annual growth from 10% to 15% (Krstić & Durdević, 2016).

Regardless of the development and importance of sport sponsorship worldwide, there is still a lack of a consistent definition of sponsorship among researchers. In 1971 the UK Sports Council explained sponsorship as financing or material gifts in exchange for donor promotions (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). In the next decade, attention was drawn to the complexity of supporting activities such as planning, organization, implementation, control, and sponsorship area – mainly sport, culture, and the public sector. Sponsorship was an individual marketing tool that fulfills the

organization’s marketing policy (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). One of the most commonly cited definitions was provided by Meenghan (1983, p. 9) which says that ‘Sponsorship can be regarded as the provision of assistance either

financial or in kind to an activity by a commercial organization for the purpose of achieving commercial objectives.’ Moreover, the author considered sponsorship as a

discrete research area attracting the attention of a broader public of marketing and communication scholars (Johnston & Spais, 2015). Another definition says that

or event for the purpose of deriving benefits related to the affiliation or

association’ (Radicchi, 2004, p. 53). Other researchers state that the sponsorship

supports the public opinion of the sponsoring company and makes customers more likely to purchase the sponsors’ goods (Walliser, 2003). While many sports sponsorship definitions exist, they all state that sports sponsorship occurs when a sporting

organization, club, league, venue, cause, or athlete is supported by a separate company or person (Smith, 2008). Usually, the sponsor provides the sports property with cash, products, or services in exchange for the possibility to reach the fans and participants of a sports event, organization, or other features. Moreover, all definitions see sponsorship as a commercial activity and state that in return for support, the sponsoring firm obtains the right to promote an organization with the recipient (Polonsky & Speed, 2001).

For the purpose of the thesis, the most suitable definition of sponsorship is ‘Business

relationship between one that provides means, resources or services, and individuals, events or organizations which in return offer certain rights and associations that can be used for the commercial purposes’ (Krstić & Durdević, 2016, p. 76). The above

definition is considered to be flexible and reflects an understanding of cooperation between the parties. Moreover, it is applied because it is wide enough to cover a range of sponsored activities and implemented motives.

What is more, sports sponsorships can be divided into six fields:

1) Sport governing body sponsorship – the committee responsible for creating sporting competition regionally and internationally

2) Sports team sponsorship – teams and sporting clubs which have small marketing resources sponsored by local or regional businesses

3) Athlete sponsorship – the company seeks to connect its name with an athlete to ensure its right in reaching the goals resulting from the partnership

4) Broadcast and media sponsorship – corporations that invest in a partnership with the radio or the television with broadcast a particular sporting event

5) Sports facility sponsorship – sporting facility (stadiums, sports halls, etc.) carry the name of the sponsoring company

6) Sport event sponsorship – businesses seek to connect their names with the sporting event (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008; Ghezail, Abdallah & Mohammed, 2017).

The researchers also recognize several types of sport sponsorship: • Referring to the title – main, titular, official, technical, partner, supplier

• Relating to the transferred benefits – financial, material, human resources, • Relating to coverage – local, regional, national, international, continental, global • Referring to the goal – image-building, promotional, sales, supporting the brand

(Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018).

When it comes to the sports event sponsorship researchers recognize three sponsorship structures:

• Solus structure – the presence of only one sponsor at a sports event

• Tiered structure – the hierarchical scope of sponsors when there are two or more levels of sponsorship, and on the top of the pyramid there is a sponsor that spend the biggest amount of money, services or goods and thus have the biggest range of rights and usage

• Flat structure – all sponsors have equal state, although every sponsor can invest the same or different amount of material means (Krstić & Durdević, 2016).

Lastly, the researchers distinguish two concepts – patronage and sponsorship. The difference between those two can be seen especially in the goals. Patronage appears as altruism – acting in the public interest (sport, culture, etc.) without expecting anything in return (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Whereas sponsorship, as mentioned before, is a tool used to achieve financial benefits by an enterprise

(Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018).

Despite the extensive knowledge of sport sponsorship, there are still some gaps and controversies. Even though sports sponsorship is considered as a part of advertising, there is a confusion between sponsorship and other promotional communications. First of all, scientists have tried to clarify the difference between sponsorship and advertising. Hastings discussed that advertising messages could be manipulated, wherein the

sponsors' messages are less easily measured (Hoek et al., 1997). He also explains that advertising targets viewers, while sponsorship targets active participants, spectators, and media followers (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). Nevertheless, this difference does not seem to hold with cases such as billboards, which are a form of advertising and target participants, spectators, and media followers when they are placed at an event

(Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). Furthermore, Marshall concludes that sponsorship can ensure the sponsor’s communications with relevant elements that would be impossible to reach through advertising (Beech & Chadwick, 2013). Meenaghan also wrote that advertising and sponsorship are integral to one another; however, he noticed that there

are essential distinctions between the two, for instance, the lack of sponsor control over the quality and quantity of the coverage as well as that the sponsorship is a non-verbal medium (Hoek et al., 1997; Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). He also claimed that

traditional advertising and promotional activities should be used in the assistance of sponsorship to guarantee the sufficient use of property rights to sponsor purchases (Hoek et al., 1997).

Moreover, in 1985 researchers examined the differences between sponsorship and advertising in objectives, awareness, promotion, and audience characteristics. As a remark, the studies showed that the effectiveness of sponsorship should be measured differently than the effectiveness of advertising (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). On the other hand, Witcher et al. have a broader view and proposed that sponsorship is another form of advertising, due to its possible impact on market behavior (Hoek et al., 1997). Lastly, it is crucial to notice that sports event sponsorship is eight to ten times more effective than advertising because sponsored events are most often supported by

significant promotion (Krstić & Durdević, 2016). Despite many differences, there is one feature that links sponsorship and advertising – managers have used both forms to fulfill similar objectives associated with the company's awareness and image (Hoek et al., 1997).

Along with the growing recognition, expanded investment, and numerous advantages, and successes associated with sports sponsorship, there are also some sponsorship’s inherent risks. For instance, the result of the agreement between the sporting event and sponsoring company can be unpredictable, especially for the sponsors. That means that companies cannot be guaranteed that the sporting event will be of high quality; hence there is the uncertainty of return in investment, brand image improvement and changes in the perception of the customers they are looking for (Smith, 2008; Copeland, Firsby & McCarville, 1996). Moreover, sponsors cannot control many circumstances during the event, such as weather conditions, problematic behavior of fans, or the event's failure, which can influence the success of the

sponsorship agreement and lead to damaging the sponsor's image (Krstić & Durdević, 2016). Another issue associated with sports sponsorship might be the presence of a big number of sponsors during the event that can confuse the audience and reduce the sponsorship outcomes (Krstić & Durdević, 2016). Lastly, companies are exposed to ambush marketing, which happens when competitors use the chance and profit without

example of high-risk sponsorship investment is Australian airline group Ansett, in which obtaining the status of official sponsor of Sydney 2000 did not turn into a competitive benefit for the sponsor on the market (Fahy et al., 2004). The investments did not protect the public image against unreasonable financial exposure and internal mismanagement (Fahy et al., 2004). As a result, it might have committed to the safety matters and the final economic collapse of the airline (Fahy et al., 2004).

2.3 Sports Sponsorship in Poland

When it comes to Poland, the sports sponsorship market exists since the late nineties (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). In the years 2003–2005, the value of sports sponsorship in Poland remained relatively similar, reaching more than EUR 100 million annually (Kończak & Jedel, 2019). Nevertheless, the development of sponsorship in Poland started in 2008, reaching almost EUR 400 million, which was caused by the greatest successes of Adam Małysz – polish ski jumper (Kończak & Jedel, 2019). At that time, brands associated with ski jumping dominated the market in terms of achieving media results (Kończak & Jedel, 2019). Another breakthrough moment in the polish sports sponsorship was Euro 2012. The football championships co-organized in Poland showed that it is possible to make a successful international sporting event in Poland, implement effective marketing activities, and prove how big marketing potential major sports events have for sponsors (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). The companies that have not been involved in sport sponsorship became more interested in it. They saw the potential of events, the positive emotions that sport generates, and the huge interest of people of this type of event (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Thus, they started to perceive sponsorship as an effective tool for implementing marketing plans (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018).

Nowadays, research shows that companies allocated their sponsorship activities, mainly to sport (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). The sport is followed by culture and art, social activities, science, and ecology (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). The sport also dominates in the case of sponsorship agreements (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018).

Further, the group of sponsors in Poland is nowadays broader, and the companies’ desire to show up is greater than it was years ago. It is related to the successes of polish

teams internationally and the perception of promotional potential, reach, and interest (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). In 2017 sponsoring companies less often used the traditional advertising methods: printed materials, direct marketing, radio, and television broadcasts (Sponsoring Insights, 2018). Instead, a stronger focus was on digital marketing, which allows companies to reach customers, build a

relationship with them, and quickly analyze the campaign (Sponsoring Insights, 2018). When it comes to the recognition of sport disciplines in Poland, the most popular is volleyball and football (Matuszak, Muszkieta, Napierała, Cieślicka, Zukow, Karaskova, Iermakov, Bartik & Ziółkowski, 2015). In the nineties, the polish sport established a relationship with the polish media, in particular with the television (Matuszak et al., 2015). From this point, volleyball and football matches have become a media product acquired by Polish Television, which caused the sponsors to believe in the power of sponsorship and were eager to get involved in It (Matuszak et al., 2015).

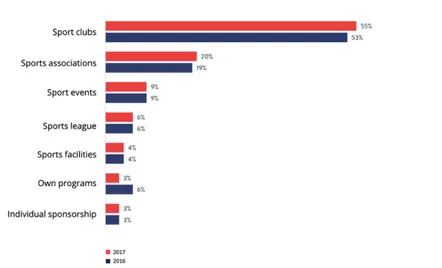

As the statistics show (figure 1), Poland's role in sports clubs and organizations is dominant (Sponsoring Insights, 2018). When it comes to sports events, every second Euro is spent on its sponsorship. In other countries, this ratio often reaches 20% -30% (Sponsoring Insights, 2018).

Figure 1. Sports sponsorship market and the categories of owner rights. Source: Sponsoring Insights, 2018.

Moreover, the statistics show industries that sponsor Polish sport the most (figure 2). As can be seen, the most involved in terms of expenditure on purchasing sponsorship rights are the energy and fuel industries. In contrast, the highest growth is recorded in the construction industry.

It is essential to mention that included graphs can be useful to recognize and analyze trends in Polish sponsorship. Thus, it can help to decide which companies to choose and interview for the purpose of the thesis.

Figure 2. Top 10 industries. Source: Sponsoring Insights, 2018.

Despite many successes and rapid development, the sponsorship potential in Poland is still not sufficiently used by companies (Kończak & Jedel, 2019). After the success of Euro 2012 Polish sponsorship market got momentum and enthusiasm for action,

however, now it lacks an impulse to an even bigger revolution in the market (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Poland already has international successes in sport and recognizable teams and athletes. Nevertheless, there might be a deficiency in professional marketing and large sponsorship agreements that show that the brand can build a unique image and achieve business benefits through sports sponsorship (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Moreover, the reason for poorly developed sports sponsorship in Poland is budget restrictions and a combination of lacking knowledge with an insufficient ability to execute sponsorship activities successfully. Businesses are often too small or do not have sufficient funds to buy

attractive sponsorship rights (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Thus, when looking at the number of sponsored brands, it can be seen how few companies have achieved the most important and the biggest sponsorship agreements (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). Regrettably, there are still companies that have never sponsored any sports event, and their knowledge is similar to twenty years ago (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). When looking at sponsoring football in Poland, only a few companies have a well-developed

marketing awareness (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018). A large part of polish sponsors limits their activities to brand their exposure on stadiums walls wherein lacking the activation of unique brand communication (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 20a18).

Despite the issues in Polish sports sponsorship, experts assure that the potential of sport sponsorship in Poland is much higher than sponsorship expenditure. The potential is seen in the desire to succeed, the sizeable European society, many good polish athletes, and in spectators that support individual sports disciplines (Fundacja Promocji i Rozwoju Sportu SportLife, 2018).

2.4 Sports Sponsorship Objectives

When sports sponsorship became more popular, the researchers have started to investigate the objectives of sport sponsorship.

One of the most known reasons for companies' involvement in sport sponsorship is the desire to increase brand awareness and improve the image of the brand (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008; Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriu, 2004; Dolphin, 2003; Walliser, 2003; Hoek et al., 1997). In one of the studies regarding the 1996 Olympics sponsors, researchers determined that the company's growing public awareness was the most crucial motive to engage in the sponsorship agreement (Apostolopoulou &

Papadimitriu, 2004). It is worth mentioning that maintaining the Olympic tradition was ranked as the least relevant; thus, it confirms the need for sports sponsorship to reach commercial objectives (Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriu, 2004). The researchers also distinguish other motives such as sales boost, larger market share, and target reach (Mack, 1999; Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriu, 2004; Papadimitriu, Apostolopoulou & Daunis, 2008). Concerning marketing goals, researchers also identify the potential for media coverage, the possibility to convert event viewers into company clients, and

occasion for public relations with current and potential customers (Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriu, 2004). From a business point of view, companies use sports sponsorship for business development purposes. For example, through positive relationships with other sponsoring companies, they can influence the view of consumers (Schwarz & Hunter, 2008; Slåtten, Svensson, Connolley, Bexrud & Lægreid, 2017). Moreover, the researchers describe image transfer as another sponsorship objective. It shows the sequence by which a sponsoring company profits from the essential attributes and specific characteristics of a sporting event (Alonso-Dos-Santos, Vveinhardt, Calabuig-Moreno & Montoro-Rios, 2016). In this way, the company tries to categorize itself or its products and services with the positive images of the event by the event’s customers – spectators and participants (Ferrand & Pages, 1996). Hence, the individual consumer combines information about the event’s characteristics, advantages, and attitudes in his memory and transfers them to the brand (Alonso-Dos-Santos et al., 2016). The

researchers identify many examples that explain image transfer, including, ‘this sport is

brought to you by video, Philips video camera are recording it, and Philips is sponsoring it’ (McDonald, 1991, p. 34).

Another identified perspective in the literature is the distinction between internal and external motives. The internal sponsorship goals are also important for companies engaged in sports sponsorship (Slåtten et al., 2017). The sports sponsorship is a perfect way to increase employee motivation, pride, and morale (Mack, 1999; Slåtten et al., 2017) and create a commitment to the company among its employees (Slåtten et al., 2017). Walraven et al. explain that ‘Sponsorships, when used as an internal branding vehicle, have the potential to contribute to employees’ identification and commitment with the corporate brand, their level of company pride and ultimately loyalty’ (Slåtten et al., 2017, p. 148). Lastly, companies apply sports sponsorship into their strategy to improve staff relations by offering possibilities for employees to attend sponsored events, including participation in hospitality areas (Schwarz & Huner, 2008; Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriu, 2004).

Additionally, Smith (2008) states that most of the sponsor objectives are marketing goals; thus, he divided them into different segments – the general public, target market, distribution channel members, and internal stakeholders. For example, the objective of the last segment addresses to the mention above internal goals; however, he also added that the sport sponsorship improves positive communications with media (Smith, 2008, p. 197).

Next to the external and internal sponsorship objectives, researchers identify personal objectives. As Meenaghan (1983) stated, the owner’s keen individual interest can be a crucial motivation for engaging in sport sponsorship. Here, a decision-maker often selects the preferred sport discipline to sponsor. The literature in recent years has also referred to greater accountability (Beech & Chadwick, 2013). Researchers state that many sponsorship initiatives were seen as nonchalant with limited reflection or strategic justification (Beech & Chadwick, 2013). It led to the term ‘chairman’s wife syndrome’, which implies that specific sports were selected for sponsorship because they appealed to the family members of senior staff within the business (Beech & Chadwick, 2013). The literature also suggests that some actions that aimed to bring commercial benefits to the sponsor have turned into philanthropy due to a lack of effective process

management (Beech & Chadwick, 2013).

Lastly, Meenaghan (1983) described the medium for community involvement as another sponsorship objective. Here, a sponsorship has more significant ability for direct influence on the community than any other promotion measure. Such sponsorship can be linked to a particular goal where help in a community project may be an efficient counter to local competition (Meenaghan, 1983). What is more, in 1995, Mount and Niro examined purposes of small and medium-sized businesses that participate in sport sponsorship in small towns (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). As the research showed, in this case, sponsorship aims to build name awareness and form relations with local communities (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998).

There can be plenty of sponsorship objectives; nevertheless, the sponsors’ purposes often depend on many particular aspects such as sponsorship industry, company size (Walliser, 2003), the character of the sponsorship relationship, and the type of supported sports field (Smith, 2008). For example, social and environmental sponsors participate in sponsorship to demonstrate social responsibility (Walliser, 2003). Wherein, for the art, sponsors, the main objective is the hospitality and service sponsors’ desire to enhance employee’s morale (Walliser, 2003). Furthermore, Amis, Slack, and Berrett (1999) state that sponsorship should generate an outcome that fits well with the image that the sponsor is trying to express. One of the cases that present business objectives is Nike, which used Michael Jordan to promote the company through building pride and to develop the corporate culture (Amis et al., 1999). Therefore, the event organizer and sponsor must have a clear understanding of the purposes of a sponsorship deal (Smith,

2008). It cannot be forgotten that sponsorship objectives are associated with the benefits of sports event sponsorship.

2.5 Sports Sponsorship Selection Criteria

When a firm selects an event to sponsor, it has to consider several key aspects, such as communication purposes of the organization, its key market, the danger of

sponsorship, and the opportunities of promotion and sponsorship expenses’ (Kotler & Keller, 2006). Before the company decides to support individual sports events,

responsible should also apply the company’s sponsorship selection criteria, which include factors that directly influence the choice of the event.

Similar to the sponsorship objectives, the list of sponsorship selection criteria usually depends on the company profile, expectations, and purposes (Walliser, 2003). For instance, the researchers examined selection criteria in different food franchises where the findings showed that the decision about sport sponsorship depends on the structure and corporate culture of each company (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997). Nevertheless, researchers identified some of the sponsor’s priorities observed in the sport sponsorship industry. To the selection criteria, researchers include similarities between sponsor product and sponsored activity as well as the correlation between targets of sponsor and sponsored events (Walliser, 2003; Meenaghan, 1983). In 1995, Mohr, Backman, and Backman examined how sponsors select the sponsorship proposals (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). The research showed that it is crucial to determine who in the

company is responsible for the choice of sponsorship and to understand the promotional aims of the potential sponsor (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998). Further research

demonstrated that media exposure (Meenaghan, 1983), exclusivity, and professionalism of event organizers are among the sponsors’ selection criteria (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998).

Moreover, researchers determine selection criteria that refer to marketing goals and relationships with stakeholders. These include popularity and image of the potential sponsored organization, possibility to integrate the sponsorship into the marketing strategy, willingness to cooperate, and contact frequency and quality (Walliser, 2003, p. 11). Researchers also recognized that sponsors consider the geographical reach and audience size (Meenaghan, 1983), the event's reach, expected sponsorship costs and benefits, and the types of rights received (Walliser, 2003, p. 11). Another conducted

research demonstrated that the key criteria that influence the decision include being able to sell products and have commercial signs and visibility within the community

(Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997). Furthermore, the researchers argue that sponsorship type can be a crucial sponsorship selection criteria. Here, a corporation should consider the appropriate involvement – an established or new sponsorship; once-off or longer-term commitment; and the seasonality of sponsorship (Meenaghan, 1983, p. 39-40).

In the 20th century, Howard and Crompton recognized five various criteria that sponsors consider when engaging in sport sponsorship. It includes sponsorship goals, fit, a choice of advertising tools, ambush marketing protection, and the length of

sponsorship agreement (Lee & Ross, 2012). Further, researchers defined the ideal sports event to sponsor from the sponsor’s point of view (Kotler & Keller, 2006). According to it, the sponsors look for events that are unique and do not have other sponsors as well as the one that attracts public attention and commit to a greater image of the product, service, or business (Kotler & Keller, 2006). Lastly, Meenaghan (1983) identifies executive preference as one of the sponsorship selection criteria. The Marketing Magazine considered it as less commercially logical sponsorship selections (Meenaghan, 1983). Nevertheless, Fletcher argued that it is not a wrong decision because, first of all, when the decision-maker is interested in sponsorship, it is less likely that the company will be deceived into bad offers. Second of all, the owner’s choice ensures commitment ‘from the top’ (Meenaghan, 1983, p. 38).

Even though more and more researchers focus on the sponsorship selection criteria of sporting events, most of them contain descriptive characteristics of the requirements that the company should apply (Copeland et al., 1996). Besides, as the number of sponsors and sporting events increases, selection criteria are becoming an increasingly important area. Choosing the right event to sponsor is evolving into a more difficult task, and taking on strategic importance (Walliser, 2003). Companies that can understand the key importance of the selection process will enhance their chance of building a profitable sponsorship deal (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997).

3. Theoretical Background

This chapter identifies relevant models and theories related to sports sponsorship to support the understanding of the research topic and the interpretation of the final results.

3.1 Decision-Making Theories

The research of decision-making has been developing with contributions from the number of fields of study for over 300 years (Oliveira, 2007). As a consequence, decision theories have included several common concepts and models, which exert an essential impact on all the biological, cognitive, and social sciences (Oliveira, 2007).

Decision-making is a process of choosing the optimal and best option among many choices (Verma, 2014). It includes the process of human thought and reaction about the external world, which involves the past and possible future events and psychological consequences to the decision-maker of the events (Oliveira, 2007). The nature of decision-making appears to combine both the beliefs about specific events as well as people’s subjective responses to those events (Oliveira, 2007). Thus, decision-making could be recognized as an argumentative or emotional process which could be

irrationally or rationally based on implicit or explicit assumptions (Shahsavarani & Abadi, 2015, p. 214). The researchers distinguish two critical factors in any decision-making: the value of deciding and implementing it and the possibility of the desired results if one acts following this decision (Shahsavarani & Abadi, 2015).

Moreover, researchers identified factors that impact decision-making: • Rational factors – quantitative aspects such as price, time, predictions • Psychological factors - include determinants such as the decider’s character,

abilities, experience, perceptions, values, aims, and roles

• Social factors – other’s agreement, particularly those who affect decider

• Cultural factors - are influenced by the form of socially accepted values, trends, and shared values (Shahsavarani & Abadi, 2015, p. 216).

Further, the decision-making has many phases such as identification of the problem, initiation of the goal, collection of the data, generation of all the alternative options, the examination of their positive and negative points, decision, implementation of the decision and learning from it (Verma, 2014; Delaney, Guidling & McManus, 2014). By

introducing such standardization, an organization can have consistency in its activities, regardless of who makes the decision (Delaney et al., 2014). The researchers also recognize many models of decision-making processes. Many forms experience common aspects and attributes; however, distinct in the order, area of emphasis, or underlying assumptions (Azuma, Daily & Furmanski, n.d.). Some of the most known approaches are:

The Rational Model

In the rational model, the decision-maker analyzes several potential alternatives from scenarios before making a decision (Turpin & Marais, 2004). Probabilities weight these scenarios, and decision-makers can define the expected situation for each option. The final choice would be to demonstrate the best-expected scenario with the highest

likelihood of outcome (Oliveira, 2007). Rationality has been described as the agreement between choice and value. Rational behavior aims to optimize the value of the results, focusing on choosing rather than highlighting the preferred alternative (Oliveira, 2007). It is expected that managers who make a rational decision identify all potential options, know the results of completing each alternative, have a well-organized set of

preferences for these outcomes, compute the results and decide which one is preferred (Turpin & Marais, 2004).

The Bounded Rational Model

In the bounded rational model, the decision maker’s rationality is bounded by the information he has, the cognitive limitations of the mind, and the limited amount of the time he has to make a decision (Lee & Stinson, 2014). Options are searched and

assessed sequentially. If an alternative meets defined implicitly or explicitly declared minimum criteria, it is assumed to ‘satisfice’, and the research is finished (Turpin & Marais, 2004). This model mainly illustrates how organizational decisions are made on a day-to-day basis (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997). Here, the decision-makers have no other option but to choose the first solutions which satisfy the minimal requirements that are propitious for reaching organizational objects (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997). The Political Model

In the political model, the decision-makers pursue their self-interest, even at the expense of the organization. Moreover, such individuals employ unethical methods, threats, and pressures to assure that decisions are made in their favor (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997).

The Garbage Can Model

In the garbage can model, it is impossible to define how managers make decisions precisely because the decision-making environment is too complex (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997). This model stresses the fragmentation and disorganized nature of decision-making in the company instead of intentional manipulations proposed by the political model (Turpin & Marais, 2004). Furthermore, decisions are made when a problem occurs and when the problem and its solution are known to the decision-maker who has the time, energy, and power needed to complete the solution (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997). When the decision is made, the garbage can is cleared away. It can happen without resolving all or some of the related problems in the garbage can. Because members produce garbage or issues and solutions, the decision depends entirely on the team of members in the can (Turpin & Marais, 2004).

The researchers also recognize the Buying Center, whose creation is related to the fact that more than one person often makes decisions in the company

(Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997; Arthur, Scott & Woods, 1997). The buying centers are informal, cross-departmental systems of all the people and groups that have a role in the decision-making process (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997, p.12). There are usually five roles in a buying center:

• Users – people that use the product or service

• Gatekeepers –people who originally take charge of the flow of purchase information • Influencer - people whose opinions or recommendations affect a buying decision • Deciders - people who have been given formal right to decide on goods and

suppliers demands

• Buyers - people with formal purchase rights (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997; Arthur et al., 1997).

It is noteworthy that many people can perform the same function, and one person can be involved in more than one position (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997).

The concept of the buying center will be further described in the next subchapter. The decision-making models can also be applied to sports sponsorship. Sponsoring companies receive a large number of unsolicited requests to sponsor sports. Events often offer many attractive benefits, which means that choosing one or several events from many can be problematic for decision-makers. It stresses the need for a greater

understanding of essential influences on a decision by companies (Aguilar-Manjarrez et al., 1997).

Furthermore, the decision-making models are significant for the thesis. It can help to create a good base for the analysis of the differences and similarities in decision-making processes within various companies. Moreover, relying on concepts of decision-making theories is relevant and applicable to companies who engage or wish to participate in sport sponsorship. As a result, these theories can improve companies’ knowledge and recognition of the decision-making processes. Lastly, the theory can describe the

components of sponsorship that may affect the decision-making process. Considering it, the theory helps in answering research questions.

3.2 Sport Sponsorship Acquisition Model

Due to the development of sport and sponsorship, sponsorship has become viewed as a legitimate part of the promotional mix that needs to be verified as a business

investment (Arthur et al., 1997). The sponsored companies require qualitative and quantitative data on how and by how much their corporate aims will be fulfilled. It led to a change in the sponsors' decision from emotional to more rational conforming to expanded business orientation (Arthur et al., 1997).

Therefore, Arthur et al. (1997) developed a sports sponsorship acquisition model (figure 3). It implies that once goals and other variables are defined, choosing and concluding the contract with sports events should be initiated as a formal organizational purchasing process similar to other company expenses. The model was based on ten in-depth interviews with companies involved in sponsoring major regional sporting events, including industries, for instance, soft drink, sporting goods manufacture, and air travel. The interviews were conducted with managers responsible for sponsorship decisions. They included questions related, for example, to decision-making processes within the company, individual or department who is responsible for the final decision. When all interviews have been conducted, the gathered information was formed together into a comprehensible and valuable decision process model (Arthur et al., 1997).

Figure 3 . The Sport Sponsorship Acquisition Model. Source: Arthur, Scott & Woods, 1997.

As the figure above shows, the sports sponsorship acquisition model consists of four stages:

Stage 1: Proposal Acquisition

The proposal acquisition includes receiving offers from organizations attempting sponsorship support. It can be either proactive - initiated by the respective corporation or more usually reactive - sports event representatives send offers to companies. Stage 2: The Composition of the Buying Center

In the composition of the buying center, received offers are subject to different

treatments. Some corporations may check them internally to reject unwanted proposals or use external agencies to screen offers. Other companies may not carry out any preparatory work in this area. As mentioned in the decision-making models, more than one person contributes to the stages in the acquisition of company sports sponsorship. The composition of the buying center includes:

The Interaction Process

In the interaction process, the purchase decision process covers many individuals; hence it is complex. Each participant presents a personal agenda of individual and

organizational goals that must be solved. The interaction may include and depend on several rational and emotional factors, as well as task-related and non-task-related determinants.

The Buying Grid

The buying grid refers to three fundamental situations. First of all, where the company evaluates a property new to it (new sponsorship tasks) – the information required would be great and with many options. Secondly, the corporate involvement in the property was ongoing (straight sponsorship rebuy) – the information demands would be minimal with no alternatives. Thirdly, after evaluation, sponsorship is renegotiated to a higher level (modified sponsorship rebuy) (Arthur et al., 1997, pp. 225-226).

Stage 3: The Purchase Decision

In the purchase decision, both rational and emotional circumstances determine the decision to buy a sponsorship. Sports sponsorship acquisition may not be as rationally motivated as initially intended, with heuristic approaches at play in some situations. Stage 4: The selection of the Preferred Sports Sponsorship Property

When the process passes through the stages mentioned above, the sponsorship

investments will be selected for implementation. This decision is then passed on to the property owners.

The sports sponsorship acquisition model will be beneficial for the study. It can help to recognize and analyze the decision-making processes within the interviewed

companies. Moreover, it can show whether examined organizations have standardized sponsorship processes as well as whether they follow presented in the literature stages or make the decisions based on their own established list of points.

3.3 Exchange Theory

The exchange theory is a family of conceptual models rather than a single method (Cropanzano, Anthony, Daniels & Hall, 2017). The theory implies that an exchange situation occurs when the desired results of more than one party are reached through the actions of both actors (McCarville, Copeland, 1994). It is characterized by interrelated conditions such as two parties that exchange resources (physical, financial or

intangible), further, the resources proposed by each party need to be valued by the reciprocating partner (McCarville & Copeland, 1994, p. 104-105). Moreover, the exchange frame was defined as ‘Social exchange as here conceived is limited to actions that are contingent on rewarding reactions from others’ (Emerson, 1976, p. 336). Homans described the exchange as the exchange of activity, tangible or intangible, and

more or less rewarding or costly, between at least two persons (Cook & Rice, 2006, p. 54). He specified social behavior and the forms of social organization produced by social interaction by showing how A’s behavior strengthens B’s behavior (in a two-party relation between actors A and B) and how B’s behavior strengthened A’s behavior in return (Cook & Rice, 2006, p. 54). Blau expressed his micro-exchange theory also in terms of rewards and costs but took a more economical and utilitarian view of behavior rather than building upon reinforcement beliefs obtained from experimental behavioral analysis (Cook & Rice, 2006, p. 54). Even though there are many various alternatives of exchange, most models share a few general characteristics: an actor’s primary treatment towards a target individual, a target’s reciprocal answers to the action, and relationship formation boundaries (Cropanzano et al., 2017).

Moreover, Bogozzi (1975) recognized three types of exchange: Restricted Exchange

Restricted exchange occurs when one party ‘gives’ and another party ‘receives.’ It may be expressed diagrammatically as A « B, where « means ‘gives to and receives from.’ Parties represent social actors such as consumers, retailers, salespeople, organization, or collectivities. Moreover, both parties must get approximately equivalent utility if the exchange is repeated (Bogozzi, 1975).

Generalized Exchange

Generalized exchange occurs between three or more groups, where the groups’ action benefits each other only indirectly (Bogozzi, 1975). For example, a generalized

exchange may be represented as A ® B ® C ® A, where ® signifies ‘gives to.’ In this exchange, social actors form a system in which each participant gives to another but receives from someone other than to whom he gave (Bogozzi, 1975).

Complex Exchange

Complex Exchange is a mutual connection between at least three parties. Here, each social actor is involved in at least one direct exchange, while the whole system is designed by an interconnecting web of relationships (Bogozzi, 1975). An example of a complex transaction can be the channel of distribution where A expresses a

manufacturer, B a retailer, and C a consumer (Bogozzi, 1975). Diagrammatically it looks as A « B « C.

Whereas in the marketing exchange, Bogozzi (1975) identifies three groups: Utilitarian Exchange

Utilitarian exchange is synergy in which the goods are delivered in exchange for money or other products, and the motivation between the activities is the expected use or tangible features generally linked with the objects in the exchange. The utilitarian exchange relates to economic exchange and, thus, to economic man. It implies that men are rational in their behavior, they try to maximize their satisfaction in trades, they have full information on choices available to them in exchanges and these exchanges are relatively free from external impact (Bogozzi, 1975, p. 36).

Symbolic Exchange

Symbolic exchange is a shared exchange of psychological, social, or other immaterial objects between two or more actors (Bogozzi, 1975). It indicates that people buy and exchange items not only for what they can do but also for what they intend and symbolize (Bogozzi, 1975).

Mixed Exchange

Mixed exchange includes both utilitarian and symbolic exchange and suggests a man in his real complexity as aiming for both economic and symbolic profits (Bogozzi, 1975). Here, a marketing man is sometimes rational, sometimes irrational, tangible, and intangible rewards drive him, he engages in utilitarian and symbolic exchanges

involving psychological and social aspects. Moreover, he has incomplete information; he proceeds the best he can and makes a simple and unconscious estimation of the costs and profits. Lastly, the exchanges do not happen in isolation but are subject to many single and social restrictions – legal, moral, normative, and coercive (Bogozzi, 1975, p. 37).

The exchange theory can also be applied to the topic of this thesis – sports sponsorship. Researchers imply that sponsorship includes an exchange of resources with an independent party to obtain an equivalent return for the sponsor (McCarville, Copeland, 1994). The exchange in sport sponsorship is based on usually transferring cash or sports equipment to the recipient by the sponsor. In contrast, the sponsee role is the application of previously agreed services that directly or indirectly contribute to reaching the sponsor’s marketing objectives (Iwan, 2010). Moreover, researchers describe three bases on which exchange theory in sponsorship is established –

rationality, marginal utility, and fair exchange (McCarville & Copeland, 1994, p. 105). These principles indicate that the exchange of valuable resources usually describes effective sponsorship based on each actor’s contribution to the sponsorship (McCarville

isolation. Hence, people looking for partners should first determine rewards that

possible partners now seek but cannot get on their own (McCarville & Copeland, 1994). Moreover, new sponsorship actions are more likely to be attempted when putting in the circumstances of past achievements and existing priorities (McCarville & Copeland, 1994).

Considering the above information and implication of the exchange theory in sport sponsorship, this theory can help to understand the connections that are created and maintained between the sponsoring company and sponsee (event organizer). It can also show whether sponsoring companies in Poland apply the above types of exchange theory. Lastly, it can illustrate what the costs and rewards of this relationship are. Therefore, theory can help structure the answers to research questions.

4. Methodology

This chapter of the thesis presents and discusses methods and techniques employed to achieve the underlying objectives of this research, which were introduced in Chapter One.

4.1 Research Design

The purpose of the thesis is to analyze the differences and similarities in the

decision-making processes of companies sponsoring sporting events at local, national, and international levels in Poland. Therefore, a comparative research design will be used.

Comparison is inherent in all science (Lor, 2011), and primarily, all empirical social research contains a comparison of some kind (Ragin, 2013). It gives a foundation for making statements about empirical regularities and for assessing and describing cases relative to substantive and theoretical criteria (Ragin, 2013). Further, comparative research can be defined as identifying similarities and differences among macrosocial units, which gives the key to understanding, explaining, and interpreting various

outcomes and processes (Lor, 2011). With these means, any technique that supports the purpose of clarifying variations is a comparative method (Ragin, 2013).

The researchers distinguish four types of comparative research:

1. Individualizing comparison - contrasts’ a small number of cases to understand the peculiarities of each case. It thoroughly explains the characteristics or features of each of the cases that are being studied (Adiyia & Ashton, 2017).

2. Universalizing comparison – intends to establish that every example of a phenomenon follows the same rule. It includes the use of comparison to explain fundamental theories with significant generality and importance (Adiyia & Ashton, 2017).

3. Variation-finding comparison – aims to compare various forms of a single

phenomenon to identify logical differences among examples and establish a standard of variations in the character or intensity of that phenomenon (Adiyia & Ashton, 2017). 4. Encompassing comparison – places various examples at different locations within the same system, on the way to defining their characteristics as a function of their multiple relationships to the system as a whole (Adiyia & Ashton, 2017).