HERE WE ARE BUILDING A MUSEUM TOGETHER: An Interactive Exhibition Verónica Giraldo Interaction Design Two-Year Master 15 Credits

Supervisor: Henrik Svarrer Larsen August 2020

Abstract

It has been established by several studies that interactive exhibitions in museums bring many benefits to the experience of its visitors. This thesis explores how to make the exhibition Människor och idéer i rörelse (People and Ideas in Motion) interactive. This exhibition took place at the Workroom of Rörelsernas Museum (Museum of Movements) in Malmö. The exhibition was designed so that no one needed to go inside, but rather view and interact with the content of the exhibition from the street, which was displayed on the windows of the Workroom.

Through a context-based design approach, the design process consisted of three main phases: inspiration, ideation and implementation. Throughout the design process, it was defined that in order to maintain the distance measures needed, it was adamant to employ technology as a design material. Following a number of testings, the specific technologies that were to be used were defined, namely capacitive sensors. Following this, the project delves into the steps needed in order to define the output of sensors. The final product consisted of four sensors. Two of these were connected to surprise boxes that enhanced the visual content of the exhibition. The other two were connected to a sound system that employed the windows as speakers, providing extra information about the museum and the exhibition.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank my team at the Museum of Movements. Thank you to Roxana Ortiz and Fredrik Elg for initiating this collaboration and allowing me to participate in this project. I would like to thank Daria Bogdanska for her empathy and dedication to this project. It was a great privilege to work alongside her and her fantastic artistic skills. Furthermore, I would like to thank Terje Ösling for his all of his help. His expertise and experience with exhibitions were indispensable for this exhibition and definitely a wonderful learning experience.

I would like to specially thank Lennart Czienskowski for all of his help, for his patience, for all of the time he spent helping me with coding & setting everything up, and especially for his moral support throughout the whole process. I would also like to thank the participants that partook in the testings. Furthermore, I would like to express my gratitude to Morgan Deumier, Lennart Czienskowski, Jonas Stegnel and Kristelle José for taking the time to proofread my texts. Your constructive comments and guidance were not only very needed, but also a true gift! Last but not least, I would like to deeply thank Viviana Pohl for her unconditional support, for always listening and for always having kind words of encouragement and understanding during this process.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 3

LIST OF FIGURES ... 1

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ... 2

1.1PROJECT FRAMING AND RESEARCH QUESTION ... 3

1.2THE CASE ... 4

1.2.1. The Museum of Movements. ... 4

1.2.2. The Exhibition ... 5

CHAPTER 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 7

2.1.INTERACTION DESIGN &INTERACTION ATTRIBUTES ... 7

2.2.TECHNOLOGY AS DESIGN MATERIAL ... 8

2.3MUSEUMS AND INTERACTIVE EXHIBITIONS ... 9

2.3.1. Interactive Exhibitions ... 10

2.3.2. Museums in times of Covid-19 ... 11

2.4CANONICAL EXAMPLES ... 12

2.4.1 Interactive Kinetic Art Installations ... 12

2.4.2. Countryside, The Future ... 13

2.4.3. Interactive Window Display ... 14

CHAPTER 3. METHODOLOGY ... 16

3.1CONTEXT-BASED DESIGN ... 16

3.2SEMI STRUCTURED OR CASUAL OBSERVATION ... 16

3.3UNSTRUCTURED INTERVIEWS ... 17

3.4SKETCHING AND PROTOTYPING ... 17

3.5ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 18

CHAPTER 4. DESIGN PROCESS ... 20

4.1DESIGN PROCESS STRUCTURE ... 20

4.2INSPIRATION ... 20

4.3.IDEATION ... 23

4.3.1. Ideation Phase I ... 23

4.3.2. Ideation Phase II ... 32

4.4 IMPLEMENTATION AND FINAL OUTCOME:THE EXHIBITION ... 41

CHAPTER 5. DISCUSSION ... 47

5.1.CONTEXT-BASED DESIGN ... 47

5.2TECHNOLOGY AS DESIGN MATERIAL ... 48

5.3MUSEUMS AND INTERACTIVE EXHIBITIONS ... 48

CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSION ... 49

REFERENCES ... 51

1

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Workroom, Museum of Movements in Malmö. ... 3

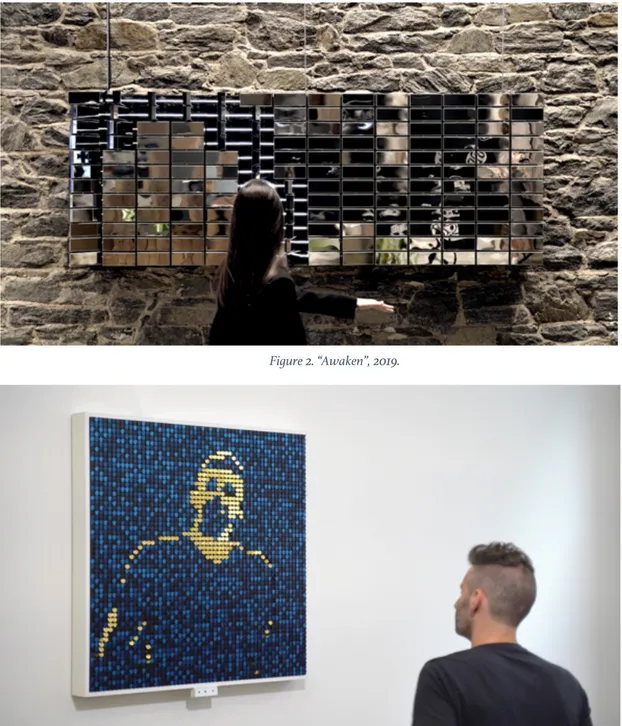

Figure 2. “Awaken”, 2019. ... 13

Figure 3. “Climate Change Series”, 2020. ... 13

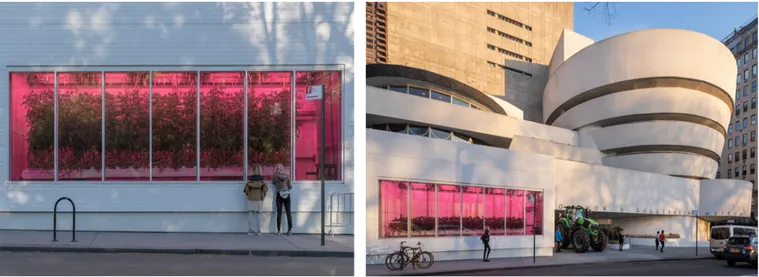

Figure 4. Countryside, The Future at the Guggenheim museum in New York. ... 14

Figure 5. Interactive window display system with gesture recognition. ... 15

Figure 6. Hiut and Rivet & Hide Interactive shop window ... 15

Figure 7. Buxton’s (2007) Dynamics of the Design Funnel (p. 138) ... 18

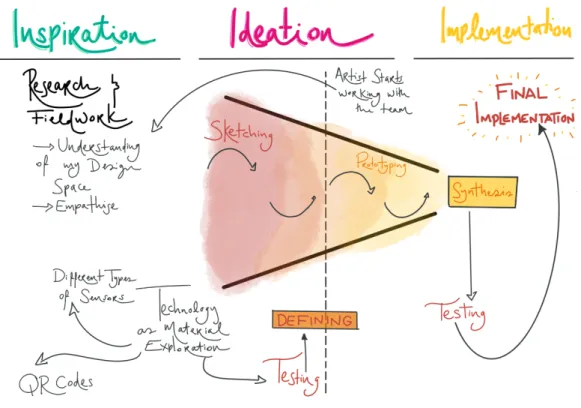

Figure 8. Outline of the design process. ... 20

Figure 9. The Museum’s logo on the windows of the Workroom. ... 22

Figure 10. Entrance installation at the Museum of Movements in Malmö. ... 22

Figure 11. First capacitive sensor sketch. ... 24

Figure 12. Testing of the sketch a museum window. ... 24

Figure 13. Typeform survey. ... 25

Figure 14. QR Codes layouts. ... 26

Figure 15. On/Off switch & ‘wavy hand’ symbol. ... 27

Figure 16. Setup process for capacitive sensors. ... 27

Figure 17. Outline of window panels where sensors can be employed ... 28

Figure 18. Final setup for testing. ... 29

Figure 19. ‘Palm towards window’ gesture. ... 30

Figure 20. ‘Palm towards window’ gesture performed by participants. ... 31

Figure 21. Artist’s first sketches. ... 32

Figure 22. Surprise boxes first sketch. ... 35

Figure 23. Surprise Box iterations. ... 36

Figure 24. Surprise Boxes boxes final version. ... 37

Figure 25. Surprise Box before the light testing ... 38

Figure 26. Surprise Box testing with bulb ... 38

Figure 27. Back of Surprise Box with aluminum foil background. ... 39

Figure 28. LED strip placement in one of the surprise boxes. ... 40

Figure 29. Exhibition “Människor och idéer i rörelse” finalized. ... 41

Figure 30. Final version of the ‘wavy hand’ symbol. ... 42

Figure 31. Visual link between sensor d and surprise box on window panel #4. ... 43

Figure 32. Final setting surprise box window panel #2. ... 44

Figure 33. Speakers window panel #2. ... 45

Figure 34. Speakers window panel #3. ... 45

2

CHAPTER 1. Introduction

It has been established by several studies that interactive exhibitions in museums bring many benefits to the experience of its visitors. The normative behavior in many museums can be described in a short slogan: ‘do not touch’ (Reden, 2015; Lupton, 2017), where the underlying interplay between the visitor and the museum’s content has been predominantly visual. Nevertheless, this is non-reciprocal system started to change for a number of reasons, as stated by Caulton (1998). For one, there was a demand from the public that they were interested in being more involved with the exhibition, as opposed to only looking at the displays. The second reason museums to started implementing interactive exhibitions relied on financial justifications, as there was a decline in the budget from governments that pushed museum to fulfil the needs of a public that could potentially spend their money in other “branches of the leisure industry” (ibid: p. 1). This has led to a shift in the identity of the museum, where they have begun to explore how to create immersive experiences through technology, though the materiality of an object and through stories (e.g. the history of their content), in order to reach their communities and to a wider variety of visitors (Levent & Pascual-Leone, 2014).

Nowadays, museums and the creative industry have been harshly affected by the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, facing massive loss of funding and grave loss in revenue (Castilla, 2020; ICOM, n.d.). Given these circumstances, it is reasonable to argue that museums are facing a new shift in their identity given the drastic change in how museums are ‘normally’ visited. This provides an opening to face the importance that museums and the culture industry has on our society in general, and embrace the inevitable shift in the identity of museums not only in how we visit and interact with exhibitions, but in how the museum as an institution is built and understood (Castilla, 2020).

This project focuses on a specific exhibition case at the Museum of Movements in Malmö (Rörelsernas Museum). The content and motivations for the exhibition will be further discussed in section 2.1 below. This museum is a national museum focused on migration and democracy, and it is in process of development. Currently, the museum has a Workroom1 space in central Malmö where different events, collaborations and discussions take place. At this stage, the museum has to report on their progress and visions for the museum’s future with the goal of obtaining the funding needed to build and develop into a fully operating museum space, which is why this project’s exhibition was scheduled. The exhibition took place at the workshop space in Bergsgatan 20 in Malmö (see figure 1).

3

Figure 1. Workroom, Museum of Movements in Malmö.

1.1 Project Framing and Research Question

Initially, it was intended that this exhibition wanted to capitalize on the ample space the Workroom offers. However, due to the ongoing situation regarding Covid-19, the exhibition is designed so that no one has the need to enter the workshop space, or interact with any staff, but instead can view and interact with the content of the exhibition from the street through the windows. In other words, this will be a distant exhibition in two senses: the rather evident one, which is the physical one, where they are not to touch anything, but also the one where, given that they will appreciate the exhibition from the street, they will have a natural distance from the museum itself.

4

The main purpose of this thesis, and my main research question is thus how to make this [distant] exhibition interactive? In this thesis, the term interactive will be understood as Gonçalves et al. (2012, p. 60), where they state that “interactivity in a museum can be described as the visitor’s ability to change the content and control the information receive[d] through gestures or actions”.

The aspect of distance in this exhibition is an interesting opportunity to explore different technologies and interactive systems that could accommodate to the current situation, where pedestrians (our given visitors) will keep distance and not touch anything. This will interestingly stand in line with the do not touch slogan so many museums live by, but will, at the same time, provide enough interactive traits in order to avoid the ‘unilateral’, only visual experience. This setting also leads to the underlying understanding that, in order to implement any interactivity to this exhibition, the employment of technologies will be necessary and will thus be used as the main design material (Redström, 2005; Bdeir, 2009; Asveld, 2019). This will be further elaborated in section 2.2.

This thesis is organized in six chapters. In the remaining part of this chapter, I will present my design space: The Museum of Movements as well as further background information on the exhibition. In chapter 2, I will continue to present theory and canonical examples. Chapter 3 will cover the methodology and different methods employed for this case, and chapter 4 will subsequently present the design process. Chapter 5 will discuss the outcome, formulating an articulation between the results and the some of the subjects touched upon on chapters 2 and 3. This thesis will thus finalize with the conclusions, presented in Chapter 6.

1. 2 The Case

1.2.1. The Museum of Movements.

As mentioned, the Museum of Movements is a national museum in the making focusing on democracy and migration from the perspective of the civil society. The museum has not been allotted a location yet but has started up with a Workroom located in the cultural district of Möllevången in Malmö. This museum is being developed under the Ministry of Culture and the City of Malmö. In 2017, a feasibility study was published, where the team stated the need and the importance for creating a space that highlights the large variety of cultures and the stories regarding issues such as democracy, human rights and migration. These stories will play a vital role in the understanding of how they all function as building blocks and elementary components of Sweden as a whole. The museum aims to collect these stories through oral history methods. These methods, as well as potential collections, exhibitions, and preservation methods will be required to adhere to rigorous ethical guidelines.

Given the fact that this is a museum that is being built from the ground up, the team has prioritized the importance of maintaining an inclusive, participatory manner throughout its building stages. Given this mindset, they have been working with a number of internal projects such as Women Making History and the Safe Havens, as well as with different stakeholders such as Afrosvenskarnas. The aim of these collaborations is to shed light on different cultures, on some of their stories, struggles and open a dialogue about these experiences. Not just to acknowledge them, but also to find solutions, alternatives and a safe space. The museum is currently at the stage where the project needs to be presented to the Swedish government with the purpose of being official acknowledged as a “national museum”, and also in order to apply for funding to start pursuing the full-scale museum, with a submission date on May 7th, 2020.

5

Furthermore, they have been using a designated Workroom, which is a space where different methods, and cooperation are taking place both as testing and preparation before the full-scale museum opens. The Workroom, as mentioned, is vital for this project, given that that’s where the exhibition took place at. This space counts with five wide windows that are very visible to the pedestrians, giving them an insight into the large room consisting of a stage, some chairs and a large kitchen. The location in the museum is on Bergsgatan, one of the main streets of this neighborhood, and is located next to the city archive, a cinema, and other cultural institutions of the area.

1.2.2. The Exhibition

The aim of this exhibition, titled Människor och idéer i rörelse (People and ideas in motion), is to show the process the museum has undergone, where it is currently standing and finally the future steps that they are aiming to take. The interactive exhibition takes place, both symbolically and physically, in the space between the Workroom space and the public space: on the windows of the Workroom. The reason behind this is to maintain an organic communication surface between the museum and the public. The windows, which symbolize the boundary between the institution and the public space, invites not only civil society organizations to the museum's own space but also to participate in the creation of new stories. Furthermore, this also stands in line with necessary social distancing measures required due to Covid-19.

The outline of the exhibition is set in a storytelling manner. The artwork was created and carried out by cartoonist Daria Bogdanska. The visual narrative is divided in five panels (for each of the five windows) representing a non-linear narrative about the museum’s creation and process, accentuating the importance of dialogue, communication and oral history (Rörelsernas Museum, 2020). The non-linearity of the exhibition addresses the fact that the windows face a busy street, and it is evident that not every pedestrian will approach the windows from the same direction. For this reason, the artist formulated the panels so that the information can be equally appreciated regardless of the direction the pedestrians approach the museum.

For the creation of this exhibition, I worked alongside a team of seven people: four of them focused on working on content, press and strategies, the artist, a production specialist who was in charge of helping with the technical aspects of the exhibition and finally myself. I was in charge of making the interactive part of the exhibition. The meetings with this group began in early April, but it was only until the first week of May that the artist was brought into the team, thus confirming the visual content of the exhibition. This collaborative effort meant we helped each other carry out various tasks. As an Interaction Designer, I have had freedom not only to use the space as I saw necessary, but also to explore different technologies and interactive systems. It is important to note however, the possible limitations for the design process. For this matter, it is necessary to clarify that the “limitations” faced have not constrained my process, but rather helped me frame my design, which will be further discussed in Chapter 4. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that, in line with Reden (2015), the aim of the interactive elements of the exhibition was to create a context and complement the main content of the exhibition, and not to take the focus away from it. The video below2 shows one of the group members describe and advertise the exhibition:

6

https://vimeo.com/434347012?ref=emshare&fbclid=IwAR2fZuutW6GOa32NtnczCUlXf93P8 9GtB71NWNVPGHhUBFHywtvI9VPjt4c

7

CHAPTER 2. Theoretical Framework

The implementation of interactive design to museum exhibitions has become increasingly popular throughout the past two decades; since museums have become “more open to exploring the possibilities brought by the digital realms in order to attract wider audiences” (Gonçalves et al., 2012, p. 59). This chapter delves into the theoretical framework needed to understand the framework for this thesis, with the aim of clarifying how Interaction Design is here understood as well as previous research in the field of interactive exhibitions and museum. The first section will start by presenting the field of Interaction Design and interaction attributes. The following section will discuss technology as design material, followed by a section focused on what are museums and the role of interactive exhibitions. This chapter will conclude with a section devoted to the canonical examples relevant for this project.

2.1. Interaction Design & Interaction Attributes

This thesis is framed within an Interaction Design framework. Here, Interaction Design is understood in Kolko’s (2011) terms:

Interaction Design is the creation of a dialogue between a person and a product, system or service. The dialogue is both physical and emotional in nature and it is manifested in the interplay between form, function and technology as experienced over time (p.15).

This definition could be complemented with the definition provided by Hallnäs & Redström (2006) where they state that Interaction Design “introduces a shift of focus from the things themselves to the acts that define them in use” (p. 22). Both of these definitions articulate that Interaction Design has a shift in the need to design “just” things to instead focus on the behavior the design will instigate in the user. In other words, we could ask ourselves, how will the user dialogue with the design artifact (over time), and how can we, as interaction designers, shape this behavior?

Silver (2007) interestingly states that “interaction designers are linguists of behavior” (p. 8), so in this line of thought, it is important to establish the vocabulary that will be used to describe the properties of the interactive artifacts produced in this project. Both Löwgren (2009) and Lundgren (2011) address that there is a need for an Interaction Design language that will help analyze and describe not only the artifacts created, but also for addressing the manner in which the interaction between the user and artifact unfolds over time.

In his article, Löwgren (2009) provides a more general take on the aesthetic experience of the interaction between user and product. Nevertheless, this experience can be created by a multitude of interaction-related properties, such as those described by Lundgren. For this matter, the language that will be used here for describing, not only the artifact but also the experience, will stand accordingly to the articulations established by Lundgren (2011). In her paper, she introduces a collection of 30 properties related to six categories: Interaction; Expression; Behavior; Complexity; Time & Change; and finally, Users. Each of these properties are understood in ranges, and these can vary in a scale-like according to different states. Given the space limit of this paper, all thirty properties will not be listed out and here described, but instead will be referenced and accordingly defined when in use.

8

2.2. Technology as Design Material

Materials have a central role in design, in our understanding of form, and what it means to craft an object […] There seems to be a significant difference between how we describe and relate to the materials important in, say, the Modern movement and how we relate to the computational technology, information and communication systems that are currently making their way into most areas of design. Whereas we refer to reinforced concrete and plywood as ‘materials’, we refer to electronics and computers as ‘technologies’ (Redström, 2005, p. 12).

As mentioned in section 1.1, in this project, technology will be used as the main design material. Given that the term technology is very broad, it is important to specify that this project will mainly focus on technologies that have actuators3 as technological components, though some other types will be also briefly explored (Section 4. 3). Actuators “provide the means for a digital system to act on the environment. They convert electrical energy into mechanical energy, producing movement [or different types of outputs such as sound or light] in the real world” (Rowland et al., 2015, p. 52). The reasoning for the use of actuators as technology lies in the fact that once the users interact with the technology, the output of this (or the actuators) should be something that can be sensed by the user through the window display. Section 4.3.1 below will delve into the defining of the output for this project.

An important notion that needs to be discussed is that of design material. As a discipline, Interaction Design holds a strong material focus akin other material-centric disciplines such as architecture, product design, industrial design and fine arts (Wiberg et al., 2013). Within these traditional design disciplines, some of the basic materials, such as wood and plastic are used and selected according to the attributes that will best fit the design. Nevertheless, within the field of Interaction Design, the material focus shifts from the traditional design disciplines given that the focus lies on the interactivity of the design, which can lead to the exploration of technology as materials4. The understanding of technology as a design material has been supported and discussed by many (Redström, 2005; Bdeir, 2009 & Asveld, 2019), arguing that despite there being a common frustration, and a scepticism towards the flexibility of working with technologies, there needs to be a reassessment that allows the designer to perceive technology in design as a means for crafting.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that the way one would handle technology as material is not necessarily the same as how one would handle more traditional materials. When using traditional materials, questions on form and aesthetics are predominant in the way we, as designers, do our material exploration, whereas when working with technology as materials, we need to think in terms of functionality. Redström (2005) points out that one of the main reasons why technology is not seen as other traditional materials is because of their ‘immaterial’ characteristic. In other words, the materiality and malleability of technological materials is notoriously different from how one would shape wood or glass.

3 Despite actuators being the main technology here used, other technologies will be mentioned and briefly

explored in chapter 4 below.

4 It is important to clarify that technology is not the only, indispensable material one can explore within the

9

Nevertheless, if we view materials and form according to the traditional definition where material is what builds something and form is how it builds it, it is not unreasonable to view technology as a design material under the same scope (ibid: p. 22).

A further relevant point to mention here, is that the use of technology as design material entails a similar approach to the use of traditional materials in the design process (Bdeir, 2009), as something the designer needs to explore, test and iterate. From Buxton’s (2007) perspective, the exploration and iteration of the technology material itself will be carried out through the sketching process. This will be further explained in section 3.4.

2.3 Museums and Interactive Exhibitions

The importance of interactive exhibition in museum spaces has been widely studied (Hornecker & Stifter, 2006; Gonçalves et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Reden, 2015), discussing not only the benefits, but also the challenges of implementing interactivity in museum exhibitions. However, before delving into this matter, this section will begin by discussing a broader matter: namely, what are museums and what motivates visitors to frequent them?

This thesis will follow the 2019 definition of museums formulated by the Committee on Museum definition, Prospects and Potential (MDPP) and accepted by the executive board of ICOM (International Council of Museums) which stands as following:

Museums are democratizing, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people. Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing (ICOM, n.d.).

This is definition was reached through the process of active listening, collecting and piecing together a number of definitions (ibid). Furthermore, this definition is not a definitive one, meaning that the MDPP will continue to dialogue and adapt their definition accordingly.

In their 2012 book, Falk & Dierking point out that, since the 90s there has been an exponential growth in museum attendance, as well as an exponential growth in the number of museums around the world. They have dedicated many years to explore and understand why people go to museums. In a related study, Falk (2009) explores a number of museum institutions of different types, such as art galleries, aquariums and science museums in order to get an overview of the different demographics of visitors that frequent these places and their experiences. He encourages museum staff that, in order to properly understand and improve the visitor’s experience, it is adamant to expand their scope of the different kinds of visitors they receive, by stepping away from the traditional categorization methods such as age and time of the year. Instead, it would be wiser to think in terms of the visitors’ personal experiences, memories and identity (amongst others) can lead them to visit the museum. For this matter, he suggests five categories for why visitors might want to frequent a museum:

Explorers: visitors who visit the museum out of curiosity and out of need of expanding their knowledge.

10

Facilitators: these are visitors that might not personally visit the museum but do so to accompany someone that cannot go there on their own. A straightforward are parents that accompany their kids to the museum.

Professionals/Hobbyists: These are visitors that have extensive previous knowledge on the content of the exhibition and attend for said special exhibition or object that is being displayed.

Experience seekers: These types of visitors are those who visit a museum as a touristic landmark, as something they need to visit because it is a “must” when visiting a certain city. A very clear example are the many tourists that visit the Louvre because it is something they should see when in Paris.

Rechargers: these visitors frequent places where they can energize and find peace in the museum space.

2.3.1. Interactive Exhibitions

Falk & Dierking (2012) point out that within the time frame of the past three decades, there has been a significant shift in the focus of museum institutions, from prioritizing the collection itself, as well as the preservation of their objects to instead focusing on the visitor experience. The first effect this shift had, was the emphasis on museum spaces beginning educational efforts, which has had a clear effect on, for example, science centers and children’s museums. As a consequence, it became established that their main purpose was that of educating the public. In a more relevant note to the context of this thesis, there has been a further subsequent shift in the focus of museum institutions given the digital and online tools that have increasingly gained importance for the museum experience (ibid: p. 16).

As briefly discussed in chapter 1, the normative behavior in many museums can be described in a short slogan: ‘do not touch’ (Caulton, 1998; Reden, 2015; Lupton, 2017), where the underlying interplay between the visitor and the museum’s content has been predominantly visual. As mentioned earlier, however, there has been a notorious change in this normative behavior. The shifts in the focus of museums discussed by Falk & Dierking (2012), have thus challenged this is non-reciprocal system, as other reasons, as pointed out by Caulton (1998). These are namely a demand from the public to be more involved with the exhibitions as well as for financial justifications.

This has led to a readjustment in the identity of the museum, with the exploration of how to create immersive experiences through technology through the materiality of an object and through stories (e.g. the history of their content), in order to reach out to their communities and to a wider variety of visitors (Levent & Pascual-Leone, 2014). Caulton (1998) states that one way of stepping away from the traditional forms of museum displays is embracing what he calls “hands-on” exhibitions. He explains that in a hands-on exhibition, the visitor will physically interact with the content “whether this is simply pushing buttons, using a computer keyboard, or engaging in a more complex activity with a multiplicity of outcomes”. He proceeds to clarify that not every hands-on exhibition is an interactive exhibition, but explains that a “hands-on exhibit that simply involves pushing a button is not truly interactive, rather it is reactive, in that the exhibit simply follows a predetermined outcome” (p. 2). For this purpose, and as mentioned in the introduction, the term interactive will be understood as Gonçalves et al. (2012, p. 60), where they state that “interactivity in a museum can be described as the visitor’s ability to change the content and control the information receive[d] through gestures or actions”.

11

Given this, a reasonable question we can ask ourselves is, how to implement interactivity in museum exhibitions? Schmitt et al. (2001) concur with the fact that there has been a notorious increase in the implementation of interactive experiences in museums in the past years with the major goal of increasing engagement of the visitor, and allowing them to be “the actors of their own museum experience” (p. 1). In line with the distinction between hands-on and interactivity provided by Caulton (1998), Schmitt et al. (2001) propose the implementation of a number of different interactive techniques, such as Mixed Interactive Systems, a system that combines digital and physical artifacts; Tangible User Interfaces, and Augmented Reality amongst others.

Hornecker & Stifter (2012) performed an evaluation performed on an interactive exhibition in the Austrian Technical Museum Vienna, where both digital and more traditional hands-on elements were employed. The study’s purpose was thus to measure the exhibition’s success based in a number of specific criteria. In line with Caulton (1998), they also highlight that the aim of this exhibition is to educate the public, and remark that an important element for this to occur, is that of engagement. In other words, they understand prolonged or repeated interaction as a positive indicator that the visitor finds the exhibition both engaging and interesting. They evaluated different types of visitors and their different aspects of behaviour, concluding that visitors will engage with media that they are familiar with, instead of exposing themselves to unfamiliar ones. For example, visitors of older age would notoriously avoid the digital elements of the interactive exhibition, while younger focused almost exclusively on these (p. 5).

2.3.2. Museums in times of Covid-19

The impact that the Covid-19 crisis has had on museums and the creative industry has been incredibly harsh, facing massive loss of funding and grave loss in revenue (Castilla, 2020; ICOM, n.d.). Dapena & Perla (2020), highlight the gravity of the situation by stating that

For the culture sector, and more specifically museums, the lockdowns required to contain the spread of the pandemic have been devastating. The American Alliance of Museums estimates that a third of American museums could permanently close this year. These extraordinary circumstances require museums to rethink their roles as agents of social change in society, both broadly and specifically within the communities they serve. The arrival of COVID-19 is more than a calamity that must be surmounted to resume the same type of work that museums were doing before the crisis. It also represents a historic opportunity to reinvent museum operations, programs, and activities to serve communities more effectively.

Given these circumstances, it is reasonable to state that museums are facing a new shift in their identities given the drastic change they must take in order to adapt to the situation. Many museums such as the Louvre, the Guggenheim and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History have made their collections available to the public through free online tours. However, some museums, such as the Museo Casa de la Memoria in Medellín, Colombia, a museum focused on opening dialogue, honoring memory surrounding the armed conflict that has been going on in the country since the 50s. Interestingly, the strategy that this museum is taking in times of Covid-19 is one of community engagement, where with the collaboration of the municipal government, the museum team is aiding, educating and assisting numerous families in a neighborhood called Villa Hermosa, which is home to numerous ethnic groups and victims of violence. They have been engaging in activities focused in the following four areas:

12

1. Communication: The museum members serve as a communication channel between the government and the neighborhood residents for both information about the virus but also about their experiences and needs.

2. Shelter: Given that there are, sadly, a lot of homeless people in the area, the museum staff provide them with shelter and temporary housing.

3. Health: Museum staff are getting trained by medical doctors on preventive issues and treatment reduction techniques. This is an important asset given that many of the residents of this area have no access to healthcare.

4. Food: Food is being distributed to those who have lost their jobs or are unable to work given the situation. (Dapena & Perla, 2020).

This example shows how museums can adapt in many different ways to the needs of their community and of the context of their surroundings. We can clearly see the malleability of the identity of museums, and of the impact they can have on our society. In times of Covid-19, museums, such as the Museo Casa de la Memoria, have the tools for learning from people’s experience during these hard times, to (ethically) gather and preserve their stories and serve as a tool of community building. This provides an opening to face the importance that museums have on our societies in general and embrace the inevitable shift in the identity of museums. One way is how they can adapt to the needs of the communities they aim to serve. However, this shift is also present in how we visit and interact with exhibitions, but in how the museum as an institution is built and understood (Castilla, 2020).

2.4 Canonical Examples

2.4.1 Interactive Kinetic Art Installations

Kinetic art is art that involves movement (both as input and output). Some of these installations, such as the ones created by the BREAKFAST collective are triggered both by gestures and bodily movement as well as environmental factors, such as wind or water. This collective is “a new media artist collective focused on creating forward-looking software-and-hardware-driven artworks that connect viewers to far-away places through interactive experiences, and tell powerful stories about our rapidly-changing world” (BREAKFAST, n,d).

All of their installations are triggered by bodily movement and gestures, but some are also triggered by different environmental factors such as the Kp-Index, or the real time solar activity and its effect on Earth (“Solar Echo”, 2020); seismic activity (“Seismic Echo”, 2020) and even clean energy production (“Energy”, 2020) and climate change (“Climate Change Series” 2019). These installations serve as an inspiration factor for my project because of their distant qualities, showing that museum visitors can interact with art through gestures and actions without having to touch of physically interact with it in order to change the content or control the information received (Gonçalves et al., 2012). Figure 2 and 3 show some examples of these installations.

13

Figure 2. “Awaken”, 2019.

Figure 3. “Climate Change Series”, 2020.

2.4.2. Countryside, The Future

The exhibition, titled Countryside, The Future at the Guggenheim museum in New York, addresses environmental, political and agricultural matters whilst aiming to provide sustainable alternatives and solutions. While the museum is currently closed due to Covid-19, the museum has continued to display one part of the Countryside, The Future exhibition (see figure 4): a grow module that is currently producing around 200 kg of cherry tomatoes around four weeks (Guggenheim, 2020). These are then donated and distributed around New York City.

This display aims to reflect on new alternative agricultural methods that are less harmful for the environment and equally efficient considering that it is indoors and in the

14

city. This exhibition invites the passerby to ponder and reevaluate the normative understanding of agriculture by showing that there are equally efficient methods that do not require as many natural resources (e.g. land and water). Furthermore, this exhibition is a great example of how museums have been adapting to physical displays amidst the pandemic while being sensitive and empathetic with the current socio-economical context. This example is relevant for this project for two reasons. The first one being the fact that this museum has continued to display a physical exhibition in times of Covid-19. The second reason is because of the context sensitivity of the exhibition’s content, where they are clearly adapting to the needs of the community they are aiming to serve.

2.4.3. Interactive Window Display

Given that this exhibition and project took place on a window surface, a natural inspiration source was window displays in general. As new technologies are evolving, retail stores have been implementing interactive techniques not only to catch the attention of passerby clients, but also to compete with the dominant online-shopping habits. SeloyLive (n,d), a company focused on the production of interactive glass, use interactive window displays in order to increase customer engagement. This is a source of inspiration for this particular project given that it allows for the exploration of different technological alternatives that could be employed. Specific examples that were intriguing were:

1. Interactive Window Display System with Gesture Recognition (2013) by Aurora Multimedia Ltd.

This product employs a rear projected film alongside a through-glass gesture sensor that that allows the customer to browse through the different products from outside the store (figure 5). This is an interesting example given that the user does not have to touch anything, which stands in line with the distant aspect of the exhibition.

15

Figure 5. Interactive window display system with gesture recognition.

2. Hiut and Rivet & Hide Interactive Shop Window (2015) by the Knit agency.

This project developed an interactive window that encourages passerby users to stop and interact with the window display at a jeans shop, River and Hide in London (see figure 6). The interaction consists of five bright yellow circles that once they are touched, they activate sound files that provide information about the shop, their products and their history.

In order to activate the sensor, the creators painted the rear side of the circles with conductive paint. Once the user touches one of the circles, the respective sound file is thus broadcasted with the use of an Arduino. These particular sensors would not be useful for this project given that, when using conductive paint, there user has to touch the material (in this case the window). Nevertheless, this example is relevant for this project given that it shows that the use of Arduino is a reliable technology.

16

CHAPTER 3. Methodology

In this chapter the methodology and methods that were used throughout the design process will be presented. This chapter will begin by discussing the methodology: Context-Based Design (CBD). Following this, the four methods that have employed in this process: Semi structured or Casual Observation, Unstructured Interviews and finally Sketching & Prototyping will be described. Furthermore, this chapter will finalize with a short section concerning ethical considerations.

3.1 Context-Based Design

As it will be discussed in this chapter, as well as in Chapter 4, an underlying aspect of this project gravitated towards the context of the exhibition and of the museum space. He et. Al. (2012) state that Context-Based Design (CBD) is “the set of scenarios in which a product (or service) is to be used, including the environments in which the product is used, the types of tasks the product performs, and the conditions under which the product operates” (p. 1).

In agreement with Okholm Hansen (2017), the understanding of CBD allows for the discussion of the concept of situatedness, or situated action coined by Suchman (1987). Situated action is thus the understanding that human activity cannot be understood without evaluating the context it is occurring in. When applying this notion to design, Suchman thus encourages the designer to keep both action and context as interdependent notions. Furthermore, this can also be linked to embodied interaction, and the understanding that

Embodiment is the common way in which we encounter physical and social reality in the everyday world. Embodied phenomena are ones we encounter directly rather than abstractly. For the proponents of tangible and social computing, the key to their effectiveness is the fact that we, and our actions, are embodied elements of the everyday world (Dourish, 2004, p. 100).

This understanding of CBD is compelling for this project given the fact that the whole design process, as well as the final outcome are designed around the context of the museum. This does not only entail the space of the museum itself, but also the content of the exhibition, and equally important, the artist’s work.

3.2 Semi structured or Casual Observation

Observation is a research method that is mostly used during early stages in the design process. It is a tool used to generate understanding of phenomena, such as spaces, people, different types of interactions and even artefacts. Martin & Hanington (2012) point out that this type of observation “typically describes ethnographic methods in the exploratory phase of the design process, where the intent is to collect baseline information through immersion,

particularly in territory that is new to the designer”(p. 120).

This method was used during early stages of the design process in order to gain insight on how pedestrians interacted with the windows at the Workroom. In later stages of the design process, this method was also used to observe how participants interacted with sketches during testing.

17

3.3 Unstructured Interviews

This method is another research method that aims to gather direct, first-hand information from participants through a number of questions posed by the interviewer. According to Wilson (2013), there are three interview methods: structured, semi-structured and unstructured interviews. In this case, only unstructured interviews were used.

Unstructured interviews are “conversations with users and other stakeholders where there is a general agenda, but no predetermined interview format or interview questions” (Wilson, 2013, p. 44). The goal of this type of interviews is thus to “gather rich, in-depth data about the users or other stakeholders’ experiences without imposing restrictions on what they can express” (ibid: p. 44). Given the flexibility of this setting, the interviewer has to be alert and in control of the situation in order to gather the needed information without the conversation drifting too much from the important content. Nevertheless, allowing the conversation to drift can also provide positive and unexpected results (Martin & Hanington, 2012; Wilson, 2014).

The unstructured interviews were employed during early stages in the design process, and were complementary to the observation method described above, where 5 random pedestrians (whose identities were not even requested) were asked: “What caught your eye and inclined you to look inside?” This was used for further understanding as to why they were curious about the Workroom space, and to understand what the existing traits in the Workroom were, that caught their attention. Gaining insight about this could potentially help us to use different traits to engage the visitors (aka pedestrians) to engage with the exhibition.

Later in the process, another unstructured interview was carried out with the artist that was chosen to create the visual content of the exhibition. This interview was used not only to get to know the person that I was going to work closely with in this project, but also, and most importantly, to understand her concept for the content of the exhibition, for further understanding the context. This will be further described in section 4.3.2.

3.4 Sketching and Prototyping

In this thesis, the concept of sketching stands according to Buxton’s (2007) understanding, where he starts by establishing that in Interaction Design, it is important to implement more dynamic ways of sketching other than the traditional pen and paper type of sketching. What is meant by dynamic is the understanding that “the experience of even simple artifacts does not

exist in a vacuum but, rather, in dynamic relationship with other people, places and objects”

(ibid: p. 135). In this line of thought, the notion of both sketching and prototyping stand in line with Buxton’s (2007) “Dynamics of the Design Funnel” model, shown in figure 7 below.

18

Figure 7. Buxton’s (2007) Dynamics of the Design Funnel (p. 138)

This funnel, and as stated on the figure, begins with ideation and leads to usability. The orange-hued area represents the stages under sketching as a discovery tool, which allows for exploration in terms of low-cost and effort. The more time that passes, the higher the quality and usability, thus transitioning into a prototype.

Two types of sketching were used in this process, especially during ideation and implementation phases. The first type were a few traditional paper drawing sketches, in line with the understanding that using this method is a not only a tool for visualization, but also for gaining insight, for generating and articulating design ideas (Goldschmidt, 1991; Buxton, 2007). Accordingly with the design funnel presented above, and as time passed, the sketches evolved from the conventional paper sketches to low-fi sketches and then prototyping (with a fair amount of iterations). This was a helpful tool when exploring different potential technologies that could be employed in the exhibition. Prototyping became a more relevant tool once one technology had been defined. This matter will further be discussed in chapter 4 below.

3.5 Ethical Considerations

In line with The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 2018), all data collected that contain personal information was handled accordingly. In this case, I handled personal information in two occasions: during my testing session, where six participants took part in the activity and once the exhibition was finished, where I filmed some visitors interacting with the exhibition. Since photographs and videos were going to be taken, they all received an informed consent form explaining how the content of the photographs could be potentially used, and the option of stating whether they wanted their faces photographed or not. Furthermore, it was important to consider the precautions needed to take concerning Covid-19 standards. For this reason, I saw each participant individually and only outside the

19

Workspace. Furthermore, they did not have to touch or have any physical contact with anything.

20

CHAPTER 4. Design Process

This chapter will delve into the design process for this project: its structure and how the different methods discussed in Chapter 3 align with the different phases of the process. This section will maintain a first-person narrative, as it will recount my individual design process.

4.1 Design Process Structure

The structure used as a guideline for the design process is based in the three-phased Human-Centered Design Process. These three phases are namely Inspiration, Ideation and Implementation. The formulation of the design process is presented in figure 8 below.

Figure 8. Outline of the design process.

This chapter will thus be divided in the three main phases presented in the Design Process above, which also aligns with the chronological occurrences of the project. Section 4.2 will cover the Inspiration phase, 4.3 the Ideation phase and 4.4 the Implementation phase. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that during this chapter, the writing style will slightly change, as I will use a more journal-like narrative which will allow for a better way of alluding to how I navigated the design process.

4.2 Inspiration

This phase began with establishing the collaboration with the museum, as well as defining the context of the exhibition. As mentioned earlier, the exhibition’s aim is to portray the recount of the process of the museum at its current state and also portray its future

21

prospects. Given the Covid-19 situation, the exhibition was designed so that no one should go inside the Workroom, or interact with any staff, but instead could view and interact with the content of the exhibition from the street through the windows and without touching anything.

The two main methods used during this phase, as part of fieldwork and research, were observation and unstructured interviews. Through the observation method, the aim was to gather information of how pedestrians interact with the windows at the Workroom. In order to perform this, I sat inside the Workroom, where the pedestrians could not see me, and took notes. Due to ethical considerations, I did not photograph the pedestrians, and just focused on taking notes. From this I could gather that a large number of people that pass by, look at the signs that are on the windows and try to glimpse into the space (though it is also possible that they are used windows as reflection). Nevertheless, a large number of people look at the windows and showed curiosity for what is in the space inside.

The second method that was employed during this phase was unstructured interviews. Differently from the natural distance taken during the observation method, I stood outside, and once I saw pedestrians look inside, I approached them, introduced myself and asked them one question: what caught your eye and inclined you to look inside? In total I approached around nine pedestrians, but naturally not all of them were keen on talking to me. In total, I got the chance to talk with 5 pedestrians.

The most predominant answer given by 4 out of the 5 pedestrians I interacted with was that they were intrigued by the space itself, as it looks appealing, but they were unsure of its purpose. Connected to this, they also mentioned that they did not know what the symbol on the windows means (see figure 9 below) and thought that it could perhaps be a dance museum. Three out of the interviewees were also attracted by the colorful installation at the entrance, stating that these bright colors really caught their eye (see figure 10 below). The data here gathered proved helpful in the sense that it gave more certainty that the space itself generates an intrinsic curiosity on the pedestrians, and considering that (despite there not being anything displayed on the windows), they still took some time and energy to think about what is it that’s going on in this space. This served as a positive indicator that pedestrians were to, indeed, take some time to look at the exhibit and hopefully interact with it.

22

Figure 9. The Museum’s logo on the windows of the Workroom.

Figure 10. Entrance installation at the Museum of Movements in Malmö.

This phase served as a way of understanding my design space and as well to empathize and begin to understand the public that will see the exhibition. However, following the results from the observation and interviews, and in combination with the aspect of distance that

23

predominates in this exhibition, it became clear that, in order to implement any interactivity to this exhibition, it would be necessary to use technology as my main material, as it would be a practical and favorable way of accommodating to the fact that the visitors should attain to distancing and avoid touching anything. Defining this, could prove problematic if we take into account Hornecker & Stifter’s (2012) study mentioned above in Chapter 2. They concluded that “the only exhibits that succeeded in reaching all types of visitors were hands-on exhibits” (p. 5), which would clearly not be possible given the necessary social distancing measures.

4.3. Ideation

Following the inspiration phase, and the decision of using technology as my main material, I felt it necessary to start testing if and how would visitors interact with different technologies or interactive systems implemented on the windows. The first step was to investigate which possible technologies could be applied, and that were also accessible (budget-wise) and feasible, considering the time frame. For said reasons, I decided to explore two different technologies: QR codes and Sensors.

It is important to highlight that, at this point, the actual content of the exhibition had not been fully defined, as the part of the team in charge of defining it were still finalizing, and they had not booked an artist either. At this point, it became rather clear that, in order to define what the actual interaction was going to be, I had to work closely with the artist given that the interactive aspect of this exhibition should cohesively stand with not only the style of the artist, but especially with the content of the exhibition. For this reason, and to be time effective, I thought that the outcome of this part of the ideation phase was to define the technology, and once the artist (and thus the content) were defined, I would ideate more and define what the actual output was going to be. For this reason, and in line with the ideation phase being divided in half on the Design Process (Figure 4), this section will focus also be divided in two: Ideation Phase 1 and Ideation Phase 2.

4.3.1. Ideation Phase I

Following this, I entered a phase of exploration as to how these technologies work and how they could be implemented. An appealing aspect of the QR code technology was the possibility of using the data from what was gathered from said interaction for future use. Understanding how QR codes work was rather straightforward: the code itself serves as a natural connecting bridge between a mobile device and an URL. The main questions with this technology were first, were participants to interact with this technology? And what could the potential output be? This second question would be something that was to be addressed in the later stages of the ideation phase.

The second idea was to implement some type of sensor that, when activated, would trigger or activate an output. For this matter, the sensors were to follow two main features: they were to activate through the window, without requiring any physical contact. Similarly, more questions arose when this point was reached: what type of sensors could potentially be used? Would participants interact with them? And if they did, how would participants interact with them? The latter question was very important considering that the visitors touching the windows was to be avoided.

Next, it was thus necessary to start exploring what type sensors could work. Upon some reading and inquiring, I found capacitive sensors, which are designed for non-contact measurements. They can measure proximity and detect anything that is conductive. The

24

description, as provided above sounded truly appealing, and fitting for this exhibition. The main question that emerged was whether they would work through glass.

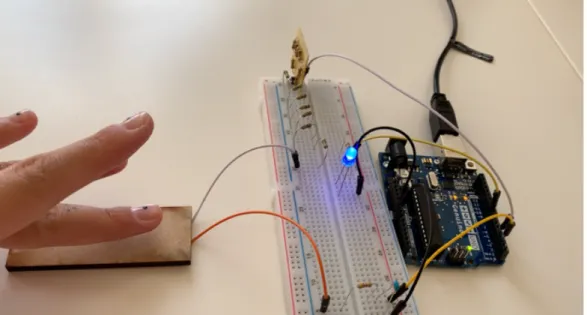

In order to test this, a low-fi sketch of a capacitive sensor was assembled (see figure 11 below). The output of this first sketch was an LED light, which would thus be activated once the sensor was approached. This sketch was created and tested through some glass at home and was then tested through one of the windows at the Workroom, obtaining positive results (figure 12).

Figure 11. First capacitive sensor sketch.

Figure 12. Testing of the sketch a museum window.

Once it was determined that the sensor worked through the windows at the Workroom, I decided to make a setup for the testing with participants in order to gain insights regarding these alternatives and define whether or not they could potentially be employed at the

25

exhibition. Furthermore, I also wanted to test if and how would the participants interact with these two technologies. The museum granted me the permission to freely use the museum space to do any necessary work or testing, which is why all testing and further ideation took place at the Workroom. I will proceed to go through the steps needed to prep for the testing of both technologies as well as the knowledge gained from it.

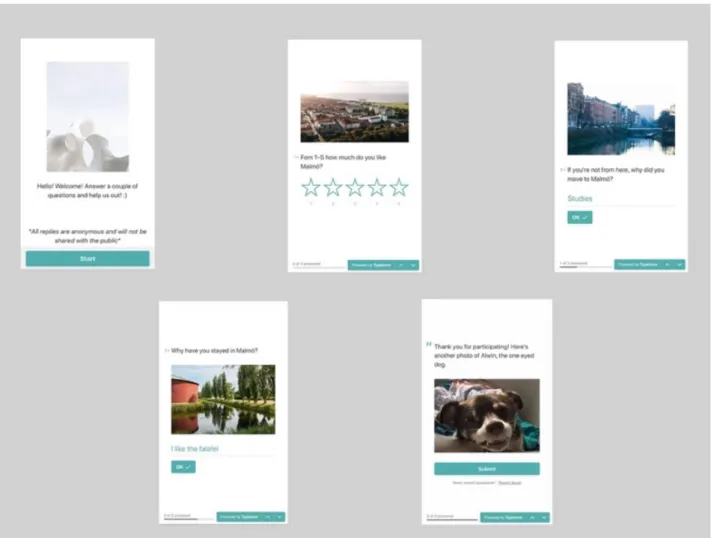

QR Codes:

For this task, the most straightforward way of testing it was to just place some QR codes on the windows and see if participants would naturally scan them and interact with its content. For this case, I created a three-question survey on Typeform (see Figure 13). All of the questions were about Malmö, and the participant’s relation to the city. This stands in line with the content of the museum (also the location of the testing session). The full survey is shown in the Appendix.

Figure 13. Typeform survey.

This survey was connected to QR codes that were generated online. Standing in line with some of the information gathered from the interviews with the pedestrians, it was established that colorful items tend to catch the pedestrian’s eye, which is why two layouts

26

were made: One colorful one and one with the photo of a dog (see figure 14). The QR codes on both layouts connected directly to the same survey.

Figure 14. QR Codes layouts.

Capacitive Sensors:

The capacitive sensors, as mentioned earlier, were an appealing technology that could potentially trigger a number of actuators when approached and would also follow the “no touching” Covid-19 protocol. The main question here was how would the participants approach and interact with the sensor?

The layout was a simple one: a light bulb was to be drawn on the window alongside a an on/off switch. The assumption was that the participant would be triggered to approach the switch, thus activating the light and turning the light on. Upon discussing with one of the group members at the museum, he suggested adding a ‘wavy hand’ sign (Figure 15) so that the way of approaching the sensor without touching the window would be clearer. An important upgrade that had to be done to the sketch was the light, so a new LED ring was mounted on a white cardboard which would aid the light to reflect more, especially during the daytime. Figure 16 shows some images of the setup process.

27

Figure 15. On/Off switch & ‘wavy hand’ symbol.

28

While setting up, a problem was encountered: the sensors did not work on all of the windows. The problem was that three out of the five windows at the Workroom are double-layered windows. The first test discussed in section 4.3.1 was performed on one of the single windows, which is why I assumed that the result obtained would thus apply to all of the windows. Figure 17 below shows the windows where the sensors can be employed. This knowledge played an important role in later stages of the ideation phase 2, which will be discussed on section 4.3.2. Figure 18 below shows the final setup for testing

29

Figure 18. Final setup for testing.

Testing Session: April 24-25, 2020:

For this testing session six participants were asked to come to the museum. The participants were evened out: three male and three female and are aged between 30 and 35 years old. I asked to meet them at the corner of the museum so they would not see the material beforehand. Upon their arrival, I explained that there was something set on the windows and that their task was to act as intuitively as possible towards the material. Once they had all performed their tasks, I asked them what their thoughts behind their actions were, and what they thought of the technologies implemented. Given that I wanted to document this and take photographs, I also provided them with an informed consent form which they all read and signed. Each session lasted for approximately three minutes.

Results

This testing session was carried out in order to see which of the two materials would prompt engagement from participants. I hill here describe the results obtained from both technological materials tested.

QR Codes:

The QR codes did not show yield results. Even though all of the participants scanned them (possibly because they felt they should), all of them were unsure as to how to scan them. Many of them thought that they might need a special app for scanning the codes and were only able to do it once I intervened and told them how. Interestingly, they all thought that since there were two QR code layouts on the window, that there was some kind of sequence, and they were all curious and keen to continue with the next one. This could be a clear indicator that once the visitor is engaged, it is highly likely that they will continue to interact with the rest of the material. The QR codes themselves seem to be a rather exclusionary, considering that if relatively young visitors have a hard time interacting with it, it is likely that older participants will also have hard time knowing how to interact with them.

30

Capacitor Sensors:

The sensors, on the other hand, showed more promising reviews. None of the participants touched the window, and they all used a ‘palm towards window’ gesture (figure 19). When asked as to why they had made that specific gesture, they mentioned that the ‘wavy hand’ sign was a clear indicator as to how they were to engage with the material. Some participants suggested that the ‘wavy hand’ symbol could have been implemented on the on/off switch to make it clearer that they should approach the switch and not the ‘wavy hand’ symbol directly. Furthermore, some participants began their movements quite far from the window, but quite naturally, as the light did not turn on, they moved closer until the light turned on. Figure 20 below show the “palm towards window” gesture performed by all the participants.

31

Figure 20. ‘Palm towards window’ gesture performed by participants.

Once these results were gathered, the next step was to inform the rest of the team of the process for the testing and the results. A meeting was thus appointed a couple of days after the testing session, where I presented the results. Given the fact that I did not want to blind myself and “lock” myself too much on the implementation of the capacitive sensors, I decided to use this meeting to open a dialogue with the team to define what was the quality they liked and found the most valuable. Upon discussion, it was clear that they found the “palm towards window” gesture the most useful. Some of the reasoning behind this was the fact that the participants used their bodies, and specific movements in order to interact with the sensors.

Following this, the next step was to figure out if there was an easier, more concrete way of achieving this movement, which could also be understood as further material exploration. In order to test this, two other sensors were tested: the first one was using a PIR motion Detector. These are infrared sensors that measure infrared light from objects in its range. This detector was promising but showed two main defects. The first one was that it did not work through the window, and if placed on the outside, we would lose the “palm towards window” interaction. Furthermore, once activated, the sensor would stay on for either 5 or 10 minutes, which would make it highly inconvenient, as the content would stay “on” for way too long time. For this reason, this sensor was discarded. The second one was to use photodiode sensors, that would basically activate when they notice changes in light. These were however, briefly considered, given that the windows face a road with heavy traffic. This was a strong trigger to the sensors and made them rather unstable and not as precise. Following this, it was rather opportune to conclude and decide to use the capacitive sensors that had proven to work well during the testing session.

32

Before moving forward, it is important to summarize, in terms of interaction attributes (Lundgren, 2011), how these sensors can be properly described. The first property relevant is that of directness. This property focuses on how hands-on the artifact is, and it allows for a range between real-world manipulation to direct manipulation to indirect manipulation. Taking into account that real-world manipulation is the most hands-on interaction in the range, where users interact with physical artifacts, and direct manipulation implies the use of screens in order to get an instant visual feedback, this particular artifact would stand close to the real-world manipulation except without the actual physical interaction. An interesting aspect of the direct manipulation is the fact that one obtains an instant feedback, which is the main purpose of using the sensors.

The second property of the sensors is that of precision. This attribute is quite straightforward, as it refers to the level of preciseness the user has to have in order for the artifact to work. In order for the sensor to activate, there is a minimum distance that it will recognize, which is roughly of 10cm distance from the window. Because of the high sensitivity of the sensor and the possible sources of interference (this is just a rough estimate). The lack of precision also allows the visitor to play with their movements and their bodies as an interaction with the artifact. In the next section, I will address the other attributes that were determined by the context of the exhibition as a whole.

4.3.2. Ideation Phase II

The second ideation phase was marked by the moment the artist, Daria Bogdanska, started working with the team. Before the first meeting with the whole team, she had had already one meeting with two of the team members where they had filled her in on the project and what they would like her to do. For this matter, when she came to the first meeting, she had a number of sketches (figures 21), where the main focus was that of oral tradition, and how, these stories can be understood as the building blocks of society. It is important to highlight that alongside the drawings she had designated some space for some text to be included on each window panel.