Unpacking the effect

of Communication

Quality on Creativity

within Virtual Teams

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: General Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: MSc in Engineering

Management

AUTHOR: Andrew Neil Gaddas and Santiago Gasch Bielsa JÖNKÖPING February 2020

i

Master Thesis in General Management

Title: Unpacking the effects of Communication Quality on Creativity within Virtual Teams Authors: A. N. Gaddas and S. Gasch Bielsa

Tutor: Tommaso Minola Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Information Sharing, Knowledge Sharing, Openness of Communication, Information Elaboration, Creativity, Virtuality

Abstract

Background: Due to the rise in technical advancements, globalization and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic, many work teams have become virtual. In virtual teams there is usually a lower level of communication compared to face to face teams due to the virtuality element of the team, which results in lower team performance. Communication is a very broad field with different subcategories such as communication quality, which is defined as the extent to which pertinent information for work is adequately distributed among team members. This category of communication has been proved to be strongly related to creativity in face to face teams. Communication quality can be split into several subcategories:

Information Sharing (the overall level of information exchanged within a team), Knowledge Sharing (knowledge or expertise exchange among team members), Openness of

Communication (how comfortable team members feel talking openly within the team) and Information Elaboration (the thorough elaboration and integration of information and perspectives).

Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the relationship between the different types of communication quality with team creativity in a virtual team. This thesis determines the relative importance of these types of communication qualities when it comes to increasing team creativity within a virtual team.

Method: This thesis conducted an online survey of 210 virtual team members from a variety of industries, job roles and countries. The data was validated to prove reliability and analysed using partial correlation, a hierarchical regression and four separate multiple linear regression to build trustworthy results.

Conclusion: The results show that all the different types of communication quality have a positive relationship with team creativity in virtual teams. Out of these types of communication the one that plays the most important role to improve team creativity is information elaboration. This is followed by knowledge sharing, openness of communication and, finally, information sharing.

ii

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1. Background ... 1 1.2. Problem ... 2 1.3. Purpose ... 32.

Frame of Reference ... 4

2.1. Method ... 4 2.2. Literature review ... 5 2.2.1. Teamwork ... 5 2.2.2. Virtual Teams ... 62.2.3. Creativity and Innovation ... 7

2.2.4. Creativity Theoretical Perspectives ... 8

2.2.5. Creativity at the Team Level ... 9

2.2.6. Communication ... 10

2.2.7. Verbal and Nonverbal communication ... 11

2.2.8. Communication and creativity ... 12

2.2.9. Communication in Virtual Teams ... 13

2.3. Theoretical Framework ... 13 2.3.1. Virtuality ... 13 2.3.2. Information sharing ... 14 2.3.3. Knowledge sharing ... 16 2.3.4. Openness of communication ... 17 2.3.5. Information elaboration ... 19 2.3.6. Clarification of hypotheses ... 21

3.

Method ... 22

3.1. Ontology and epistemology ... 23

3.2. Sample ... 24

3.3. Survey ... 25

3.4. Ethical Considerations Towards our Participants ... 26

3.5. Measuring ... 27

iii

3.5.2. Measuring team creativity ... 29

3.6. Data Analysis method ... 29

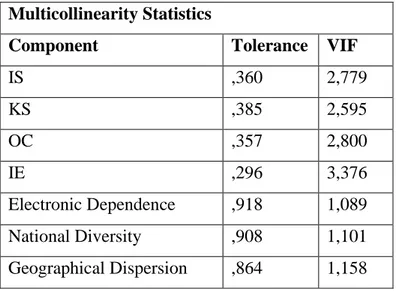

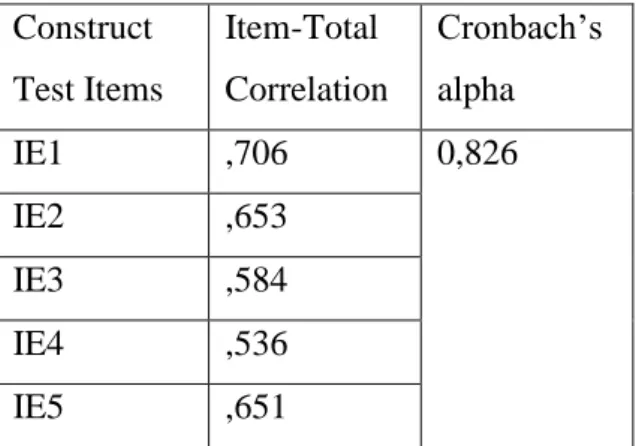

3.7. Pre-Analysis Testing ... 30 3.7.1. Reliability Testing ... 30 3.7.2. Validity Testing ... 31 3.7.3. Multicollinearity Testing ... 32 3.7.4. Method bias ... 33

4.

Results... 33

4.1. Multiple Linear regression ... 36

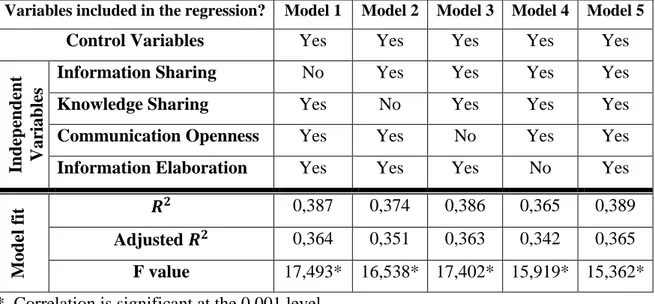

4.2. Comparing regressions Δ𝑅2 ... 37

4.3. Multiple linear regression analyses ... 39

4.4. Analysis conclusions... 41

5.

Discussion ... 42

5.1. Discussion of Results ... 42

5.1.1. Knowledge sharing vs Information elaboration ... 43

5.1.2. Knowledge sharing vs Openness of communication ... 44

5.1.3. Openness of communication Vs Information sharing ... 45

5.1.4. The Global Pandemic Effect ... 45

5.2. Theoretical contributions ... 46

5.3. Implications of Research ... 47

5.4. Limitations of our study ... 48

5.5. Future research ... 49

6.

Annex ... 51

6.1. Survey ... 51

6.2. Reliability Testing Result Tables ... 53

6.3. Validity Testing Result Tables ... 55

iv

Tables

Table 1. Measuring examples and sources for the different types of communication

quality ... 28

Table 2. Multicollinearity Statistics and VIF Results ... 32

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations ... 35

Table 4. Partial correlation controlling for Electronic dependence, national diversity, geographical dispersion and Team size ... 36

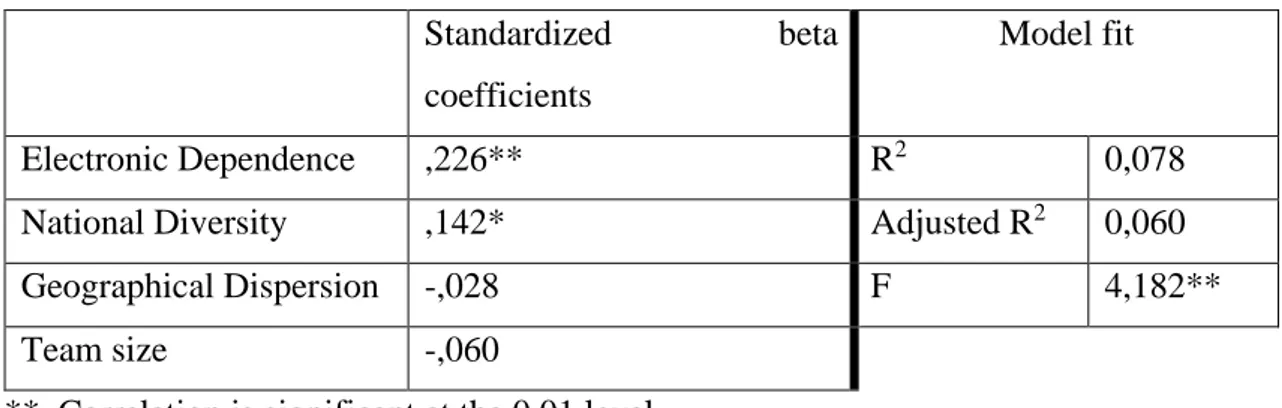

Table 5. Regression analysis with the control variables ... 37

Table 6. Hierarchical multiple regression showing unstandardized beta coefficients ... 38

Table 7. Multiple linear regression analyses, showing unstandarized beta coefficiants and t values... 40

Table 8. Information Sharing Construct Reliability ... 53

Table 9. Knowledge Sharing Construct Reliability ... 53

Table 10. Knowledge Sharing Construct Reliability Removing KS2 ... 53

Table 11. Openness of Communication Construct Reliability ... 54

Table 12. Information Elaboration Construct Reliability ... 54

Table 13. Creativity Construct Reliability ... 54

Table 14. CFA Results of Information Sharing ... 55

Table 15. CFA Results of Knowledge Sharing ... 55

Table 16. CFA Results of Openness of Communication ... 55

Table 17. CFA Results of Information Elaboration ... 55

1

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________

This thesis studies communication practices among virtual team members and the effect on team creative performance. In this section we introduce the topics of virtual teams, creative performance and communication, explore the problem faced by virtual teams and state the purpose of the research with formulated research questions.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1. Background

With the rise in technical advancements, virtual teamwork comes with many advantages for global organisations, as well as for their employees (Schulze & Krumm, 2017). Moreover, with the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus and government advice for employees to work from home, co-located teams are experiencing a transformation into dispersed teams and becoming virtual. Virtual teams are defined as teams that are geographically dispersed, mediated by technology, structurally dynamic, or nationally diverse (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006). This form of workplace creates interesting team dynamics and changes typical team interactions, in turn influencing how a team achieves its goals.

Creativity drives progress and allow organisations to maintain their competitive advantage (Hughes et al., 2018; Zhou & Shalley, 2003). It is frequently being used as a measure of performance and has become a strategic priority within organizations (Martins & Shalley, 2011). Workplace creativity is defined as the cognitive and behavioural processes applied when attempting to generate novel ideas (Hughes, Lee, Tian, Newman, & Legood, 2018). A basic premise in creativity literature is that diversity and divergent thinking between team members is necessary for creativity, due to the combining of knowledge and perspectives from different team members (Martins & Shalley, 2011; Gilson, Mathieu, Shalley, & Ruddy, 2005). In virtual teams, team members are often sought out from different geographical locations for their expert knowledge, allowing virtual teams to harness diversity (Martins & Shalley, 2011). Increased innovation and creativity are often touted as the primary benefit of a virtual team (Gilson, Maynard, Young, Vartiainen, & Hakonen, 2015; Gibson & Gibbs, 2006). However according to Martins & Shalley, (2011) for the potential creative benefits due to differing perspectives to be realized, it is important that interactions enable the pooling, surfacing and coming

2

together of different perspectives which can only be achieved through team communication.

Team communication can be defined as an exchange of information or knowledge, occurring through both verbal and nonverbal channels, between two or more team members (Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009). Team communication is conceptualized as integral to many team processes and it is claimed to enhance team performance via facilitating and improving critical team processes. Specifically, team communication quality is strongly related to team performance, in both virtual and face-to face teams. Communication quality is defined as the extent to which pertinent information for work is adequately distributed among team members. Marlow et al. (2018) include the following types of communication within the category of communication quality: information sharing (i.e., overall level of information exchanged within the team), openness of communication (i.e., how comfortable individuals feel talking openly with other team members), knowledge sharing (i.e., knowledge or expertise sharing with other team members) and information elaboration (i.e., the degree to which individuals thoroughly elaborate on information they share with the team).

1.2. Problem

Virtual teams have several pragmatic advantages above face-to-face teams: (1) virtual teams allow group work across space (geographical) and/or time; (2) virtual teams can be composed of the best performing individuals in a particular field no matter how remote their location; and finally, (3) other benefits such as low costs, low travel efforts, and the enabling of flexible working practices (Curseu, Schalk, & Wessel, 2008); (Bergiel, Bergiel, & Balsmeier, 2008). Such advantages together with ongoing technical advancements have led to a large proliferation of virtual teamwork (Schulze & Krumm, 2017).

However, there are problems associated with virtual teams, just by bringing people with the required knowledge and skills together virtually provides no guarantee that they will be able to work effectively (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006). So how do teams work effectively together? According to Salas et al. (2015) there are some critical considerations for team effectiveness. These include the attitudes and motivations within the team for engaging in teamwork (i.e., cooperation), the behavioural interactions among members (i.e.,

3

conflict, coordination, communication, coaching), and the shared knowledge that arises out of these interactions (i.e., cognition). These considerations should also be present in virtual teams as in co-located teams. However, the truth is that they are usually lacking in virtual teams compared to face-to-face teams. Virtual teams have difficulties establishing and maintaining goals, as well as developing personal relationships, cohesion, and trust (Hertel, Konradt, & Orlikowski, 2004; Gibson & Gibbs, 2006).

A study by Curseu, Schalk, & Wessel (2008) agrees that the development of trust, cohesion and a team identity is one of the most difficult challenges for managers of virtual teams. The lack of face to face communication among virtual team members creates contextual complexity and weak personal ties which can hamper attentiveness, mutual understanding, relationship building and trust development (Curseu, Schalk, & Wessel, 2008). When these features are lacking in a virtual team, innovation and creativity can also be reduced (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006).

A way of facing the challenges posed by virtuality is through communication (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006). Specifically, communication quality is strongly related to team performance and creativity in face to face teams (Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018; Hu, Erdogan, Jiang, Bauer, & Liu, 2018). We think it is of absolute importance for managers and leaders to understand the relations between the different types of communication quality and creativity in a virtual team, so that they can encourage followers to further establish the types of communication with the strongest relation with creativity.

The existing literature has studied the relationship between the different types of communication quality (i.e. information sharing, openness of communication, knowledge sharing and information elaboration) with team performance (Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018). However, there are no studies further focusing into virtual teams and more precisely, studying the effect of each specific communication quality type on creativity.

1.3. Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to unpack communication quality into its different types (information sharing, openness of communication, knowledge sharing and information elaboration) and study its effect on team creativity separately in virtual teams. This study

4

also wants to determine which one of the different types of communication quality has the strongest relation to creativity in virtual teams. Therefore, the research questions are the following:

(RQ1) What is the relationship between the different types of communication quality on creativity in a virtual team?

(RQ2) Which type of communication quality has the strongest correlation to creativity in a virtual team?

This thesis is filling the existent gap in the literature of the specific relation between the different types of communication quality and creativity in virtual teams. This thesis also determines which of these communication quality types is of most importance for creativity in the virtual context.

This study is relevant as virtual teams are becoming the new normal way of working in teams (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006) and with the outbreak of COVID-19, many companies and working positions have quickly changed to working virtually. This makes research in the area of virtual teams very relevant to the challenges of a firm in today’s working climate. Our research will build on a growing body of literature that looks at the performance of virtual teams and the connection with team processes such as communication. Further our study aims to understand better how virtuality affects team creativity and will compare communication types.

2. Frame of Reference

______________________________________________________________________

In this section we conduct a review of the most current literature relevant to the research topic, describe the methods used to find said literature and develop a theoretical framework from which we build our hypotheses.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1. Method

The articles used in this thesis are all pulled from relevant journals with a high impact factor. We have always tried to get the most recent articles of the topic, therefore, we only considered articles from the year 2000 on. The articles that we have included which are older than twenty years old, were considered due to their current relevance.

5

In order to look for articles we first started using keywords like: “Team communication”, “Virtuality”, “Virtual Teams”, “Creativity”, “Innovation”, and their respective Boolean interactions “Communication and Virtual Teams”, “Innovation and Virtual teams” etc. These keywords were entered in search engines such as Web of Science, Primo or Google Scholar. We sorted the results by relevance and then filtered them, only considering articles from 2000 on, on the topic of business management. We first focused on the literature review papers of these topics, and then performed snowballing to the articles they referenced.

Once we had our purpose clarified, we started looking for the different communication quality types, through snowballing or search engines using the following keywords: “Information Sharing”, “Knowledge Sharing”, “Openness of Communication” and “Information Elaboration”.

2.2. Literature review

There are three major concepts relating to the research questions: creativity, communication and virtual teams. In this section we aim to present the current state of literature for these major concepts in order to begin building a foundation for the theory in which to anchor our study.

2.2.1. Teamwork

First the definition of teamwork should be provided, and according to Salas et al. (1992) teams are “a distinguishable set of two or more people who interact, dynamically, interdependently, and adaptively toward a common and valued goal/objective/mission”. For teams to be effective, they must successfully perform both taskwork and teamwork (Burke, Wilson, & Salas, 2003). Both taskwork and teamwork are critical to successful team performance, with the effectiveness of one facilitating the other.

Taskwork involves the performance of specific tasks that team members need to complete in order to achieve team goals. In particular, tasks represent the work-related activities that individuals or teams engage in as an essential function of their organizational role (Wildman, et al., 2012). Conversely, teamwork focuses more on the shared behaviours (i.e., what team members do), attitudes (i.e., what team members feel or believe), and

6

cognitions (i.e., what team members think or know) that are necessary for teams to accomplish these tasks (Morgan, Salas, & Glickman, 1994).

2.2.2. Virtual Teams

Early research on virtual teams defined it as “work carried out in a location remote from the central offices or production facilities, where the worker has no personal contact with co-workers but is able to communicate with them electronically” (Cascio, 2000). However, recently, scholars have shifted away from the dichotomy of pure face-to-face versus pure computer-mediated interactions to focus on the extent of virtuality. Gibson and Gibbs (2006) describe different types of virtuality: teams that are geographically dispersed (consisting of members spread across more than one location), mediated by technology (communicating using electronic tools such as e-mail or instant messaging), structurally dynamic (in which change occurs frequently among members, their roles, and relationships to each other), or nationally diverse (consisting of members with more than one national background). These capabilities are central to the innovation process.

However, various definitions of team virtuality exist in the extant literature (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler, 2011). Kirkman & Mathieu (2005), for instance, raise three dimensions for virtuality, which are different from the ones suggested in Gibson and Gibbs (2006). The former authors claim that these dimensions are: (1) the proportion of team interaction that occurs via virtual means, (2) the extent to which virtual tools transmit data that is valuable for team effectiveness and (3) the synchronicity afforded by the tools, i.e. the extent to which team interactions occur in real time versus incurring a time lag.

One of the problems that virtual teams face is its low social proximity. This concept is defined as the socially embedded relations between agents at the micro-level. Relations are embedded when they involve trust based on friendship, kinship and experience (Boschma, 2005). Virtual teams sometimes struggle to build a sense of social proximity, leading to poor team performance and innovation inhibition.

Virtual teams use computer-mediated communication (CMC) to improve the communications within the team. There are two types of synchronicity in CMC: synchronous (media that allow for real-time communication, e.g. Skype) and asynchronous communication (media that do not allow for real-time communication and

7

which can be used at random times among the participants, e.g. e-mail). Synchronous technologies were found to help establishing common ground as well as presence awareness between individuals (Karis, Wildman, & Mané, 2016). The advantages offered by the asynchronous technologies is that team members can work regardless of their teammates’ availability (Chamakiotis, Dekoninck, & Niki, 2013), these can also handle the uncertainty that can arise from low access to information and the language barriers (Tenzer & Pudelko, 2016).

Some research on virtual collaboration has provided evidence that relational and emotion communication via computer-mediated communication (CMC) is possible but needs time and skills on the side of the collaborators (Beranek & Martz, 2005; Byron, 2008).

2.2.3. Creativity and Innovation

Creativity and innovation are concepts that incorporate several related processes that can overlap but have clearly distinct definitions. Anderson et al. (2014) put forward the definition of creativity and innovation that integrated the two processes as two distinct concepts, where creativity is the stage of idea generation and innovation is the stage of implementing ideas. This definition according to Hughes et al. (2018) has two limitations; first the definition does not describe the nature of the phenomenon and thus can lead to misconceptions. Secondly the phenomenon cannot be differentiated from its effects. i.e. in their definition creativity and innovation are outcomes and products that are recognised by their results. Hughes et al. (2018) put forward the following definition to remove the limitations:

“Workplace creativity concerns the cognitive and behavioural processes applied when attempting to generate novel ideas. Workplace innovation concerns the processes applied when attempting to implement new ideas. Specifically, innovation involves some combination of problem/opportunity identification, the introduction, adoption or modification of new ideas germane to organizational needs, the promotion of these ideas, and the practical implementation of these ideas.”

This definition Hughes et al. (2018) argue, separates creativity and innovation from only being recognised by its outcome. The definition aims to delineate the two concepts further with the argument that there can be novel ideas created but never implemented, likewise

8

there can be innovations based on non-novel ideas. Hughes et al. (2018) further argues that it is important to clearly define the characteristics of creativity and innovation as two separate but related processes, as there have been several publications in top tier journals that have treated the two concepts as the same which has led to hypotheses in innovation being built on creativity research and vice versa. For the purpose of this study we will use the definition put forward by Hughes et al. (2018) for creativity, delineating innovation and creativity but noting that the processes are overlapping.

2.2.4. Creativity Theoretical Perspectives

Most of the creativity literature point towards five influential theoretical perspectives on creativity. Each theory discusses their framework on different levels of analysis, such as the individual, the team, the organization and multiple level analysis. However, some of the frameworks put more emphasis on a chosen level rather than try to integrate the theory to a multi-level analysis (Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

Componential theory of organizational creativity; focuses on work environment that effects creativity through components that contribute to creativity. The three main components that effect individual or small team creativity are expertise, creative thinking skill and intrinsic motivation. At the organizational level there are components that can influence employee creativity, these are organizational motivation to innovate, resources and managerial practices. This theory has received recent empirical support for the motivational side of the theory (Zhou & Shalley, 2010; Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

Interactionist perspective of organizational creativity; discusses that creativity is a complex interaction between the individual and the different levels of the organization. At the individual level, factors such as cognitive style, motivation, personality, relevant knowledge and contextual influences, all influence creativity. At the team level, interactions between team members, team characteristics, team processes and contextual influences, are what effect creativity and innovation. At the organizational level innovation is the function of both group and individual creativity (Yuan & Woodman, 2010; Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

9

Individual creative action framework argues that employees need to choose between being creative with their work or carrying on in routine way. Effecting this choice are three groups of factors: motivation, sense making process and knowledge and skill. All three factors in this theory need to present in order for an individual to take creative action. (Unsworth & Clegg, 2010; Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

Cultural differences are also theorized to have an impact on creativity, and that creativity can work differently in different cultures. At the individual level creativity is influenced by cultural values, which in turn can be moderated by task and social context. On the team level, literature argues that there is value in diversity, meaning that diversity creates divergence in teams which leads to creativity in the team (Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen, 2009; Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

Ambidexterity theory represents the two processes of exploration (the creation of new products) and exploitation (implementation of new products). This requires active management to resolve conflicts between the two conflicting activities. This theory focuses more on the leadership influences on the team level and discusses how executive teams should balance these concepts in order to get the most value out of creativity and innovation (Rosing, Frese, & Bausch, 2011; Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014). 2.2.5. Creativity at the Team Level

Research into the effect of team heterogeneity and diversity has conflicting opinions on its effect on creativity. Findings are both positive and negative for the influence on creativity, research is along the lines of greater diversity lead to team divergence which improves creativity, and research also suggests that greater diversity leads to less team cohesion and in turn lower implementation capabilities (Anderson , Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

Team leadership has also been researched into influencing team creativity. Rosing, Frese, Bauschl. (2011) correlated that transformational leadership strongly influenced creativity, whereas transactional leadership was more effective in innovation. This is supported by ambidexterity theory where leadership needs to be both explorative and exploitative (Anderson, Potocnik, & Zhou, 2014). An extensive meta-analysis by Hughes et al., (2018) investigated the correlation between leadership styles and creativity. Form their analysis

10

transformational and transactional leadership have been the most studied leadership styles in creativity. Other leadership styles such as empowering leadership, authentic leadership and servant leadership had fewer studies on their effects on creativity. Their study indicated that the lesser studied leadership styles had stronger positive correlation to creativity, however, this could be due to the smaller number of samples that were available for analysis.

According to Gilson et al., (2015), creativity as a performance measure in virtual teams has not received much consideration form recent studies. They put forward that creative literature has identified diversity and divergent thinking as necessary for creativity in teams. These are prevalent in most virtual teams as teams are usually geographically dispersed and often span national borders. However according to Martins & Shalley (2011) they found that national diversity had a strong negative effect on creativity. Gibbson and Gibbs (2006) related the difficulties faced by virtual teams as the core factors that affect the innovation and creative processes. In a virtual team setting, teams are geographical dispersed, face a dependence on electronic tools, they can be nationally diverse teams, or have a dynamic team structure. They believe that the ability of teams to innovate depends upon how well team members of virtual teams can generate, import, share, interpret, and apply technological and market knowledge. The study correlated that innovation was negatively affected by geographical dispersion, electronic dependence, national diversity and dynamic team structure. Further the study found that by creating a psychologically safe communication culture within the virtual team, it was possible to reduce the negative impact of the four elements.

2.2.6. Communication

Team communication can be defined as an exchange of information, occurring through both verbal and nonverbal (e.g., email) channels, between two or more team members (Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009). Communication is directly related to team performance and creative performance, since it does not only distribute critical, task-relevant information to team members (Salas, Sims, & Burke, 2005), but also facilitates and improves critical team processes, such as coordination and strategy formulation (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001)

11

Marlow et al. (2018) Classified the most relevant and researched types of communications into two main categories: (1) quality, the extent to which communication, both of a verbal and nonverbal nature, adequately distributes pertinent information among team members as needed; and (2) frequency, the volume of communication, both of a verbal and nonverbal nature, which occurs among team members. In their meta-analysis, they claim that communication quality has a significantly stronger relationship with performance than frequency, supporting the idea that too much communication might mitigate performance.

On the subcategory of communication frequency, they include the following types of communication: objective communication frequency (i.e., the overall communication volume; Jarvenpaa et al., 2004, as cited in Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018), content analysis coded communication (i.e., frequency of knowledge sharing of a specific topic; Minionis, 1995, as cited in Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018) and self-report frequency (i.e., number of times team members meet face to face or how frequently they felt they interacted; Boerner, Schaffner, & Gebert, 2012, as cited in Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018).

2.2.7. Verbal and Nonverbal communication

Verbal communication is defined as human interactions through the use of words, or messages in linguistic form, it can refer to speech (oral communication), written communication, and sign language (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

Nonverbal communication is understood as the sending and receiving of thoughts and feelings via nonverbal cues (Ambady & Weisbuch, 2010, p. 465). Cue is broadly defined as “any numerical, verbal, graphical, pictorial, or other sensory information which is available to a judge for potential use in forming a judgment” (Cooksey, 1996, p. 368). Despite the distinction, nonverbal and verbal communication are related in several ways, since the former can repeat verbal discourse (e.g., a nod to show agreement), substitute it (e.g., an eye roll instead of a statement of contempt), complement it (e.g., reddening while talking to an intimidating person), accent it (e.g., a slap on the back following a joke), or contradict it (e.g., wiping tears away while asserting that one is fine) (Richmond & McCroskey, 2004).

12

There are five functions of nonverbal communication: display personal attributes, exercise dominance and establish hierarchy, promote social functioning, foster high-quality relationships and display emotions (Bonaccio, O’Reilly, O’Sullivan, & Chiocchio, 2016). Bonaccio et al. (2016) also note three types of codes of nonverbal communication: body codes (i.e., communication through the eyes, the body movement, or one’s appearance), sensory and contact codes (i.e., communication through voice, touch or smell) and spatiotemporal codes (i.e., communication through physical space, objects or the use of the time).

2.2.8. Communication and creativity

“Communication is essential to creative teams: without it, no team could perform in any way” (Kratzer, Leenders, & van Engelen, 2004). Literature states that communication aids in the dissemination of knowledge and ideas; through communication new knowledge and insights can be produced; and communication is essential to the timely availability of information required by the creative team members (Kratzer, Leenders, & van Engelen, 2004).

Lack of linguistic commonality is a communication impedance, the greater the mismatch in language and cognitive orientation, the greater the difficulties of communicating, and correspondingly the less encouraging is communication for a high creative performance (Kratzer, Leenders, & van Engelen, 2004). This usually happens when creative teams are split into sub-groups. Since these sub-groups tend to generate their local orientation and coding schemes, those who share this common intra-group language communicate efficiently, minimizing misinterpretations between team members (e.g. Allen, 1984). On the other hand, if team members do not share a common coding scheme and technical language, their communication will be less efficient and more costly (e.g. Wilensky, 1967).

Finally, Kratzer et al. (2004) note that a high frequency of communication tends to decrease the creative performance of innovation teams, however, there should be a minimum of frequency of communication around one to three times the week (Leenders, Kratzer, Hollander, & Van Engelen, 2002).

13 2.2.9. Communication in Virtual Teams

Computer mediated communication offers important advantages over face-to-face communication. In fact, although face-to-face communication offers easier coordination, additional non-verbal information, and a greater opportunity to observe behaviour and build trust, communication via computer-mediated conversation is less inhibited by social norms and group pressures, it has a reduced potential for production blocking and evaluation apprehension, it saves a record of communication/decisions, it gives the opportunity to weigh, consider, and digest information shared by team members, and more time to consider and research contributions to team discussion. However, virtual communication also has weaknesses not found in face-to-face meetings such as increased potential for miscommunication, lack of warmth and non-verbal cues, potentially disjointed communication, and the need for some level of computer/technology proficiency (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler, 2011).

2.3. Theoretical Framework

The goal of this section is to discuss the specific theory we will use in our study to answer our research questions. We develop and discuss several hypotheses on the effect of communication types on creativity and hypothesize which communication type according to theory will have the largest effect on creativity in a virtual team.

2.3.1. Virtuality

Given that most organizational teams can be considered as virtual to some degree (Kirkman, Gibson, & Kim, 2012), the theory of virtual teams has moved towards the degree of virtuality rather than classifying teams as face to face or virtual. Virtuality is considered as multidimensional with Gibson and Gibbs (2006) describing it as: teams that are geographically dispersed, mediated by technology, structurally dynamic or nationally diverse. The two most consistent dimensions shared by research are geographical dispersion and technology mediation (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006). This definition will be integral to our study as we will also move away from the traditional theory of face to face vs virtual teams and instead consider the level of virtuality present within the team.

14

The absence of nonverbal cues associated with most virtual communication within teams (Gibson & Cohen, 2003), makes it hard for team members to discern whether messages are understood, since the understanding of information imparted by team members is often confirmed or denied via nonverbal (Bonaccio, O’Reilly, O’Sullivan, & Chiocchio, 2016). Because of these reasons, communication in face-to-face teams has a stronger correlation with team performance than virtual teams (Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018).

Cultural differences also play a crucial role for effective communication. Because global virtual teams communicate in a language that is not the first language for many of the team members, the levels of linguistic capability of the them may differ in phonics and syntax. Unfamiliar accents and an inappropriate use of vocabulary can make it hard and sometimes impossible to understand each other (Gibson & Cohen, 2003). However, if we go to the opposite extreme of language knowledge, some authors claim that diversity in language has a negative impact on organizational communication in general (Charles & Marschan-Piekkari, 2002). Interestingly in creative theory, cultural differences are theorized to have a positive effect on creativity (Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen, 2009). Within a team, cultural differences create a divergence which can promote creativity. While cultural differences can moderate the effectiveness of communication and thereby negatively influence creativity, it may directly also promote creativity through diversity. Communication Quality Types

Marlow et al. (2018) include the following types of communication within the category of quality communication: information sharing, openness of communication, knowledge sharing and information elaboration. Although they note that there are additional types of communication, these are unable to be categorized using this scheme, as they are based on measures created exclusively for a specific study or measures which are not used in additional studies, and do not map onto the previously described categories.

2.3.2. Information sharing

Information sharing involves conscious and deliberate attempts on the part of team members to exchange work-related information, keep one another apprised of activities, and inform one another of key developments (Bunderson & Sutcliffe, 2002). It could be defined as well as the overall level of information exchanged within the team, which could

15

be either unique, (not know by all the team members) or common (known by every team member). Information sharing is a central process through which team members collectively use their available informational resources; if information is not effectively shared among team members, the team is not able to fully benefit from informational resources initially distributed throughout their team. Sharing information builds the available knowledge stock, and improves team performance, mostly when teams share unique, rather than commonly held, information (Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009). Information and perspectives sharing, also broadens the scope of team skills, inspires team members to look for novel solutions to problems, and provides fresh and useful thinking, sparking new insights, generating creative ideas and promoting team creativity (Hu, Erdogan, Jiang, Bauer, & Liu, 2018).

Mesmer-Magnus and DeChurch (2009) suggest that less knowledge-redundant teams, precisely those teams who stand to gain the most from sharing information, actually, share less information than more knowledge-redundant teams. Their findings, curiously, point to three situations in which teams share more information; it is when (1) all members already know the information, (2) members are all capable of making accurate decisions independently, and (3) members are highly similar to one another. Also, when team members do not share the same functional background, Bunderson and Sutcliffe (2002) found that this situation of intrapersonal functional diversity in a team is positively associated with information sharing.

When it comes to information sharing in the virtual world, past literature on the impact of virtual communication in team information sharing have yielded no clear pattern of results; since, depending on the source, we can either conclude that virtual communication is a benefit, or a detriment (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler, 2011). The study by Mesmer-Magnus et al. (2011) adds on that virtual teams have a longer time to think, process and research about the information, and they are more socially equal (there are fewer cues indicating the status of each team member), they will share more unique information than face-to-face teams. Our first, then, hypothesis addresses the relationship between information sharing and team creativity in virtual teams. We suggest that considering that this type of communication makes information available for teams, improving team performance

16

(Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009) and inspiring team members (Hu, Erdogan, Jiang, Bauer, & Liu, 2018), it is going to have a positive relation with team creativity in virtual teams.

(H1a) Information sharing has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when information is shared.

2.3.3. Knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing can be defined as the transference of knowledge among individuals, groups, teams, departments, and organizations (Asrar-ul-Haq & Anwar, 2016; Crossan, Lane, & White, 1999). It is regarded as a basic element of the team learning process as teams who successfully exchange knowledge develop their knowledge base (Kessel, Kratzer, & Schultz, 2012). Literature has already found strong evidence associating knowledge sharing with creativity; previous studies have shown that knowledge sharing allows teams to combine their knowledge and develop new solutions (Kessel, Kratzer, & Schultz, 2012; MacCurtain, Flood, Ramamoorthy, West, & Dawson, 2010).

Research has identified many knowledge sharing behaviours that can affect knowledge sharing, these characteristics can be on individual, team and organizational levels. For example, on the individual level, attitudes to knowledge sharing was found to be an important precursor to knowledge sharing behaviours and this could be influenced by demographic variables such as age (Asrar-ul-Haq & Anwar, 2016). At the team level, management support and the mixture of values and norms within the team also influence knowledge sharing behaviour. At the organizational level, organization culture can influence knowledge sharing behaviours (Asrar-ul-Haq & Anwar, 2016). Knowledge sharing behaviours enhances the performance of virtual teams by generating new knowledge during the sharing process (Pangil & Moi Chan, 2014). It is considered that knowledge sharing is more difficult in the virtual team (Pangil & Moi Chan, 2014). This is due to the virtual environment reducing trust among members, a lack of knowledge sharing confidence and the perspective that knowledge sharing is a ‘extra role’ rather than a job responsibility, all of which reduces the knowledge sharing behaviour of team members (Hao, Yanga, & Shib, 2019).

17

Knowledge sharing is considered a key factor in creative behaviour (Perry-Smith J. E., 2006; Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004). When a team shares their knowledge between members, the different perspectives and ideas encourage individuals to behave creatively (Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004). In this way knowledge sharing has a positive impact on team creativity (Kim, 2020).

In this study we believe that knowledge sharing behaviours will be present in virtual teams but reduced due to lower trust levels and a lack of knowledge sharing confidence (Pangil & Moi Chan, 2014). However, knowledge sharing will still have a positive effect on the virtual teams’ creativity, therefore our second hypothesis is:

(H1b) Knowledge sharing has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when knowledge is shared.

Further, knowledge sharing is already regarded as a key factor in creative behaviour (Perry-Smith, 2006). Virtual teams are often made up from nationally diverse team members (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006), thereby increasing the likelihood of different perspectives and different knowledge within the team, this would suggest that the national diversity in a virtual team will increase the effectiveness of knowledge sharing on creativity. We propose the following hypothesis that the effect of knowledge sharing on creativity is greater than that of Information Sharing. Where information sharing is the exchange of work-related information (i.e. facts or data regarding work), knowledge sharing the exchange of knowledge (i.e. the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject).

(H2a) Within virtual teams, knowledge sharing has a stronger influence on team creativity than information sharing.

2.3.4. Openness of communication

Openness of communication, instead of focusing on the content or quantity of information shared, assesses how comfortable individuals feel talking openly with other members of the team (Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018). Research suggests that openness of communication is strongly related to team satisfaction and cohesion and sets the stage for more efficient interpersonal team process (Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009), mitigating the negative effects of computer-mediated communication in virtual

18

teams by allowing them to develop the social structures necessary to maintain positive affect, enhancing creativity and team performance (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler, 2011). In fact, although great openness does not necessarily imply an increase in the team’s knowledge, openness indirectly enhances team performance by creating and improving positively the team socio-emotional status such as psychological safety, trust, and cohesion among team members (Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009).

Openness of communication is specially present in teams composed of functionally broad individuals, which usually are more strongly motivated to exchange information and are less susceptible to the stereotypes and in-group/out group biases that restrict the open sharing of information (Bunderson & Sutcliffe, 2002).

We believe that openness of communication is going to have a positive relationship with team creativity in virtual teams, since it is strongly related to team satisfaction and cohesion, which mitigates the lack of warmth, distinctive from a virtual environment, improving trust (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler, 2011) and, therefore, creativity (Gibson & Cohen, 2003).

(H1c) Openness of communication has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when information is open.

Compared to information sharing, openness of communication is less related to team performance in face-to-face teams; however, considering that virtual teams have lack of warmth, reduced verbal and non-verbal cues, and increased possibilities of misunderstandings, information openness plays a more relevant role in performance, than the one by information sharing (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler, 2011). This is why, in our study, we expect that openness of communication will have a stronger effect on team creativity than information sharing.

(H2b) Within virtual teams, openness of communication has a stronger influence on team creativity than information sharing.

When compared to knowledge sharing however, we believe that the moderating effect of virtuality will have a greater negative effect on the openness of communication (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Shuffler,

19

2011) than on knowledge sharing. This coupled with knowledge sharing being regarded as a key direct factor in creative behaviour (Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004) we believe that knowledge sharing will have a stronger effect on creativity than that of openness of communication, hence our next hypothesis:

(H2c) Within virtual teams, knowledge sharing has a stronger influence on team creativity than openness of communication

2.3.5. Information elaboration

Information elaboration was originally defined by (van Knippenberg, 2004) as: “the exchange of information and perspectives, individual-level processing of the information and perspectives, the process of feeding back the results of this individual-level processing into the group, and discussion and integration of its implications”. However due to its overly broad nature and combination of intra and interindividual processes (van Dijk , Meyer , & Van Engen, 2018), Meyer, Shemla, & Schermuly (2011) put forward a definition as: ‘the act of exchanging, discussing and integrating information and perspectives through verbal communication’. The second definition is argued to be a clearer definition that leaves out ambiguity and presents a measurable definition (van Dijk , Meyer , & Van Engen, 2018). The current state of research has shown that teams make better decisions when they thoroughly exchange and integrate information between team members (van Ginkel & van Knippenberg, 2008). The meta-analysis conducted by Marlow et al (2018) also found that information elaboration had the strongest connection to team performance.

A study conducted by (Maynard , Mathieu, Gilson, Sanchez, & Dean, 2019) into effects of information elaboration in virtual teams found that personal and professional familiarity have positive effect on information elaboration, with professional familiarity having a significantly greater effect than personal. However, in the virtual team setting, both personal and professional familiarity were negatively moderated by virtuality, leading to a lower level of information elaboration. (Peñarroja , Orengo, Zornoza, Sánchez, & Ripoll (2015) also found that group information elaboration had a positive association to team learning in virtual teams. Group information elaboration could be considered as an indicator of in-depth processing of task related information and perspectives.

20

Studies have also linked information elaboration with team creative performance (Pillaya, Parkb, Kimc, & Leec, 2020; Toader & Kessler, 2018). An experiment conducted by Toader & Kessler (2018), proved that information elaboration enhanced team creative performance, however, it was driven by similar or complementary team mental modes and moderated by team goal orientations. The study by Pillay et al, (2020) found that expressing gratitude within the team can improve information elaboration and in turn team creative performance.

From our analysis of the literature we believe that in a virtual team there will be lower levels of professional and personal familiarity, with a lower level of team goal orientation. This, in turn, will lead to lower levels of information elaboration in virtual teams and a lower level of team creativity. However, we believe that information elaboration will still have a positive effect on creativity in the virtual team, therefore our next hypothesis is:

(H1d) Information elaboration has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when information is elaborated.

The concepts of information elaboration and information sharing could be confused, but the main difference lays on the fact that whilst information sharing measures the exchange of unique or common information, information elaboration measures the depth and assimilation of this information. Therefore, because information elaboration is not only addressing whether information is thoroughly shared within the team but whether it is acknowledged (Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018), we believe that it is going to have a stronger relationship with team creativity than information sharing.

(H2d) Within virtual teams, information elaboration has a stronger influence on team creativity than information sharing.

As mentioned previously, the meta-analysis conducted by Marlow et al (2018) found information elaboration to have the strongest correlation with team performance. However in the virtual team setting, information elaboration is negatively affected by virtuality (Peñarroja , Orengo, Zornoza, Sánchez, & Ripoll, 2015) due to a reduction in professional and personal familiarity. Therefore, we hypothesize that knowledge sharing will have a stronger influence on creativity than information sharing:

21

(H2e) Within virtual teams, knowledge sharing has a stronger influence on team creativity than information elaboration.

When we compare information elaboration to openness of communication, one could argue that the former must have a stronger relationship with team creativity, even in the virtual context, since the assimilation of the information should be essential for team creativity. In fact, information elaboration is as a very strong predictor of performance, in comparison to other communication types (Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018). This leads us to our last hypothesis:

(H2f) Within virtual teams, information elaboration has a stronger influence on team creativity than openness of communication

2.3.6. Clarification of hypotheses

Hypotheses 1a-d are answering the first research question by proving that the different types of communication, separately, have a positive relationship with team creativity in virtual teams.

Hypothesis 2a-f are aimed at building a hierarchical order of the strength of the relationship of the different types of communication with team creativity in virtual teams. The hierarchical order we have hypothesized is, in first position, knowledge sharing, followed by information elaboration, openness of communication and information sharing, respectively.

Hypotheses 1a to 1d:

(H1a) Information sharing has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when information is shared.

(H1b) Knowledge sharing has a positive relationship with team creativity

within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when knowledge is shared.

(H1c) Openness of communication has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when information is open.

22

(H1d) Information elaboration has a positive relationship with team creativity within virtual teams, such that creativity increases when information is elaborated.

Hypothesis 2a to 2f:

(H2a) Within virtual teams, knowledge sharing has a stronger influence on team creativity than information sharing.

(H2b) Within virtual teams, openness of communication has a stronger influence on team creativity than information sharing.

(H2c) Within virtual teams, knowledge sharing has a stronger influence on team creativity than openness of communication.

(H2d) Within virtual teams, information elaboration has a stronger influence on team creativity than information sharing.

(H2e) Within virtual teams, knowledge sharing has a stronger influence on team creativity than information elaboration.

(H2f) Within virtual teams, information elaboration has a stronger influence on team creativity than openness of communication.

3. Method

______________________________________________________________________

In this section we describe our research design and motivate the choices of research methods. For this study, we have chosen to take the philosophical research positions of realist ontology with a positivist epistemology. Following this position, we have chosen a quantitative methodology using a factual survey to collect data on various virtual teams. The survey collected data on the presence of communication quality types, the level of virtuality and creativity. The data collected was analysed using SPSS. First the data was tested for reliability, validity and multicollinearity. Then the data was analysed through correlation testing, multiple linear regression and hierarchical multiple linear regression.

23

3.1. Ontology and epistemology

The ontological position we have taken in this study is one of realist. Realism is defined as an ontological position which assumes that the physical and social worlds exist independently of any observations made about them (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018). This is the position that we believe will match our research questions the best as we consider that communication quality has an existing relationship with creativity but has not yet been fully identified with all the properties of the connection. By taking this ontology we aim to illuminate a connection that already exists and that our research will bring new properties of the connection into the realm of knowledge. Further we can explore several types of communication in the same study, compare their effect on creativity and hopefully generalise the findings as we are merely highlighting existing connections. However due to taking a realist ontology, this study is limited in its exploration of why the communication types described can affect creativity. Further, this study will not explore how the connection between them are formed or build a new theory of communication type. The approach of realism is more suitable to our studies purpose compared to a nominalism ontology which would not allow us to compare different types of communication. The connection between the communication type and creativity in a nominalism ontology would be subject to the perspective of the virtual team under study and only valid for that specific team.

Following the realism ontology of the study we are taking the epistemological route of positivist. In positivism the key idea is that the social world exists externally, and that its properties should be measured through objective methods (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018). By taking this epistemology we aim to measure the effect that the different communication types will have on creativity. Through measuring the effect, we can identify the relationship between the two (research question 1) and compare which communication type has the strongest relationship to creativity (research question 2). As we know that studies have already identified the connection between communication and team performance (e.g. Marlow, Lacerenza, Paoletti, Burke, & Salas, 2018), it is logical to take measurement approach to our research as we aim to explore if the communication types are as strongly related to creativity in virtual teams. Further our research aims to generalize the theory to all virtual teams. The epistemology of positivism is a better approach to studies purpose as we would not be able to compare the

24

communication types to each other in social constructionism due to each virtual team having varying context that could change the influence of a communication type to creativity.

For our methodology we have chosen to conduct quantitative research using a large factual survey. This method follows the selection of positivism epistemology and realism ontology. It is also the best method for answering our research questions as a quantitative approach that test hypotheses and examines relationships between variables is more appropriate when a problem is clear and propositions have been specified (Eisenhardt, 1989). Our research questions are very generalized towards the concept of virtual teams, we define them as geographically dispersed teams, mediated through technology and nationally diverse. This broad definition of virtual teams means that any research regarding virtual teams would have to cover various configurations of these factors otherwise research explored would not be generalizable to all virtual teams. This broad definition mixed with the various types of communication types makes a large survey the logical choice in methodology. Surveys can be employed to generate large representative samples which enables the development of methodologically robust conclusions (Snow & Thomas, 1994). Additionally, survey analyses due to their analytical and descriptive nature constitute a good research strategy for theory testing (Black, 1999). Although qualitative interviews can give rich and detailed information from respondents (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018), for our study we prioritized quantity and diversity in order to gather more data and easily generalize the theory. Moreover, we can also get detailed information, if our survey questions go straight to the point, using comprehensible vocabulary.

3.2. Sample

In order to answer both of our research questions and prove our hypothesis, we wanted to have a diverse sample that could allow us to study the relationship between the different types of communication quality and creativity among team members working in different levels of virtuality. Since specific departments, companies or cultures can have their different procedures, traditions or perceptions, that could have an impact on our results, we aimed for a diverse survey among different nationalities, industries and companies, so that we could avoid the impact of these in our analysis. As mentioned in section 1.3, our

25

purpose is to study the relationship between the different types of communication quality and creativity in virtual teams, therefore, we think that the more diverse our sample is, the more decontextualized and reliable our results will be. Our sample inclusion criteria is any person working in any job role as part of a virtual team for a private or public company, all sizes of company and all industry types.

Considering that we (the authors of this thesis) have both international experience and work experience, which have developed and diversified our network, we started sending out the survey to our friends, family members and former colleagues that we knew they were working virtually. We used email or instant messaging applications in order to request them to fill in the survey. In the message we also ask them politely to resend the survey to their teammates. We also posted the survey on Facebook and LinkedIn in order to reach out to our extended network and to allow easy forwarding to teammates.

3.3. Survey

The survey was made with Google Forms. The reason why we used this platform is because it provides an easy to use platform for the survey and it is free to use. The answers in this tool are easy to download, moreover, the interface is intuitive, making it easy for respondents to answer the survey, and they only need to have internet connection to answer it.

The survey started by thanking the respondents for their time, followed by a statement ensuring that their data will be confidential and secure and will not be shared with third parties. This helps us establishing a sense of trust with the respondents (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018).

The first questions of the survey are addressing the degree of virtuality of the team, asking about the size of the team and the number of team members working from a different location. Then, using a 5-point Likert scale we asked about the degree the team members communicate between them using (1) e-mail or instant messaging, (2) teleconferencing software, and (3) collaborative software (questions adapted from Gibson and Gibbs, 2006). In this five-point Likert scale 1 represented never, 2 rarely, 3 sometimes, 4 often and 5 always. After that, we asked about the number of different nationalities in the team, and the number of teammates from other nationalities. We decided to ask these questions

26

about the virtuality of the team, to make sure that our sample featured high degrees of virtuality. In this section we also included a question asking if they were already working under these conditions before the COVID-19 pandemic.

After answering the questions listed above, respondents were asked to grade their degree of agreement with statements on different communication quality types. There were a total number of 20 statements, five per each communication quality type. Participants evaluated their agreement to each statement using a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 representing strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 somewhat disagree, 4 neither agree or disagree, 5 somewhat agree, 6 agree and 7 strongly agree. This kind of grading has been used in literature to evaluate the presence of the different types of communication quality in a team (Bunderson & Sutcliffe, 2002; De Dreu, 2007; O'Reilly & Roberts, 1977; among others).

This was followed by statements addressing creativity. Respondents graded each statement using a 7-point Likert scale as above.

Finally, we collected some general information about the team, in order to ensure the diversity of our sample. The questions in this section asked about the industry and the position the respondents work in, as well as their gender, age and country of residence. The entire final survey can be consulted in the Annex of this thesis. The survey was as well translated into Spanish, so that Spanish speakers without any knowledge of English could answer the survey.

3.4. Ethical Considerations Towards our Participants

Bell and Bryman (2007) identified ten principals in ethical practice for conducting research. These ten principals can be summarized into two main concepts of protecting research participants and protecting the integrity of the research community (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018). In order to comply with these 10 principals and to follow ethical practice in conducting our research (Bell & Bryman, 2007), we took the following steps: 1) The research did not collect any personally identifying information such as names, email addresses, addresses or phone numbers. This was done to protect the anonymity of all participants while ensuring their privacy in taking part in the research. 2) The research did not collect the names of any companies that participants

27

worked for. This way the anonymity of all companies was ensured while also protecting participants from any harm in taking part in the research coming from conflict with employers. 3) The purpose of the research was clearly stated at the beginning of the survey, describing the topics of interest to the research and clearly stating the goal of the research. In doing this we avoided deception about the nature and aim of the research, worked honestly and transparently with our participants. 4) All collected data has been stored on cloud-based storage providers that are password protected so that only the 2 researchers of this paper can access the data. The data was not shared or distributed with any third party, ensuring that the research data remains confidential. 5) At the end of the survey, contact details for both researchers was provided as a contact point for any participant with concerns about the research questions or data protection concerns. The hope was to open a communication path to any participant that had concerns regarding the research and thereby respect the dignity of the participants.

3.5. Measuring

Regarding the measurement of the different types of communication quality and team creativity, we based our method in the existent literature. In order to measure the four types of communication quality and team creativity respondents had to grade their degree of agreement with a sentence addressing the types of communication and creativity. The mentioned sentences were adapted from existing articles, which studied some of the concepts that this thesis aims to investigate.

3.5.1. Measuring communication quality types

The items adapted concerning the different types of communication quality, were all adapted from the literature as it is shown in Table 1.

28

Table 1. Measuring examples and sources for the different types of communication quality

Type of communication quality Measuring examples Adapted from:

Information sharing “Team members work hard to keep one another up to date on their activities”

“The quality of information exchange in our team is good”

Bunderson and Sutcliffe (2002), De Dreu (2007)

Knowledge sharing “Team members share their special knowledge and expertise with one another”

“Team members know who on the team has specialized skills and knowledge that is relevant to their work”

(Faraj & Sproull, 2000) (Song, Park, & Kang, 2015)

Openness of Communication “It is easy to ask advice from any member of this team”

“It is easy to talk openly to all members of this team”

O’Reilly and Roberts (1977), which has been cited in very recent articles such as Marlow et al. (2018)

Information elaboration “Team members contribute a lot of information for projects or tasks”

“Team members contribute unique information for projects or tasks”