Initial conditions for penta helix

collaboration in social innovation

A case study of ReTuren

Catarina Vasconcelos

Minh Ha Nguyen

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and OrganisationMaster Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits

Spring 2018

Abstract

Social innovation brings about sustainability which is regarded as a new paradigm for development. In order to bring about social innovation, cross-sector collaboration among different actors is required. However, it is known that establishing cross-sector collaboration is very complex, especially in a penta helix model where the public administration, business, academia, third sector and citizens are all involved. The research aims to investigate the initial conditions for establishing penta helix collaboration in the context of co-produced social innovation from the perspectives of core co-producers. Through a case study of ReTuren, a co-produced public platform for waste handling and prevention in Malmö, Sweden, the research finds out four themes of initial conditions, viz. environment, resources, relationships, and strategy. It is also discussed that the significance of these conditions to the collaboration establishment can depend on the development stage of the social innovation initiative. The research also provides new insights about the unclear boundary and the flexible role of each sector in the penta helix model. Based on the findings, an adapted model of initial conditions from Bryson et al. (2015) for penta helix collaboration in social innovation is created.

Keywords: cross-sector collaboration, penta helix model, initial conditions, social innovation, co-production

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to our supervisor, Sandra Jönsson, Ph.D for her invaluable guidance, inspiration and support. We would also like to thank our classmates and thesis opponents for the advice and comments on this thesis. We are deeply thankful to our families and friends for their endless love and support. This thesis has been completed during one of the researchers' scholarship period at Malmö University, thanks to the Swedish Institute scholarship.Table of contents

1.Introduction ... 1

1.1.

Social innovation: the need for penta helix collaboration ... 1

1.1.1.

ReTuren: a co-produced social innovation initiative... 2

1.2.

Initial conditions for penta helix collaboration: a research problem ... 2

1.3.

Purpose ... 3

1.4.

Research Question... 3

1.5.

Methodology... 3

1.5.1.

Ontological and epistemological ground... 3

1.5.2.

Research approach ... 3

1.6.

Thesis structure ... 4

2.

Pre-understandings ... 5

2.1.

Social innovation and co-production: an environment for cross-sector collaboration ... 5

2.2.

Cross-sector collaboration ... 6

2.2.1.

Penta helix model of cross-sector collaboration ... 7

2.2.2.

Initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration... 8

2.2.3.

Bryson et al. (2015)’s model on initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration .... 10

2.2.3.1.

Criticism of the model ... 12

3.

Methods ... 14

3.1.

Case study design ... 14

3.2.

Case introduction ... 14

3.2.1.

The development of ReTuren ... 14

3.2.1.

Co-producers and core co-producers ... 15

3.3.

Data collection methods ... 16

3.3.1.

Interviews ... 17

3.3.2.

Documents ... 18

3.4.

Data analysis methods ... 19

3.4.1.

Interviews ... 19

3.4.2.

Documents ... 20

3.5.

Quality and ethics of research ... 21

3.5.1.

Quality of research ... 21

3.5.2.

Ethical considerations... 22

3.6.

Limitations of research ... 22

4.

Results and data analysis ... 24

4.1.

Local context and institutional environment ... 24

4.2.

Shortage and availability of resources ... 26

4.3.

Initial leadership and existing relationships ... 27

4.4.

Communication and agreement on problem and vision ... 30

5.

Discussion ... 33

5.1.

Initial conditions for establishing penta helix collaboration ... 33

5.1.1.

General initial conditions ... 33

5.1.2.

Initial conditions in development stages of social innovation ... 34

5.2.

Adapted model of initial conditions for penta helix collaboration in co-produced social innovation ... 36

5.3.

Penta helix collaboration for co-produced social innovation ... 40

6.

Conclusion and implication for future research ... 41

6.1.

Identification of initial conditions ... 41

6.2.

Contributions to theory ... 41

6.3.

Recommendations for practice in co-produced social innovation initiatives... 42

6.4.

Implication for future research ... 42

References... i

Appendices ... vi

Appendix I ... vi

Appendix II ... vii

Appendix III... ix

List of Figures

Figure 1 - Framework of cross-sector collaboration by Bryson et al. (2015) ... 10Figure 2 - Timeline of events in ReTuren’s development stages ... 14

Figure 3 - Organizational structure for both phases of ReTuren ... 16

Figure 4 - Revised and adapted models of initial conditions based on Bryson et al. (2015) ... 39

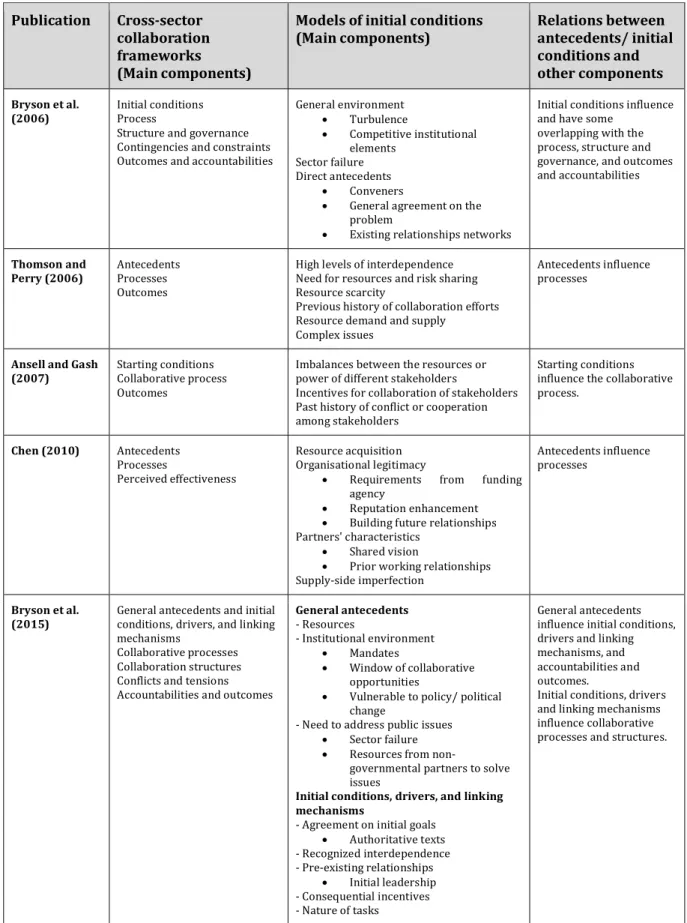

List of Tables

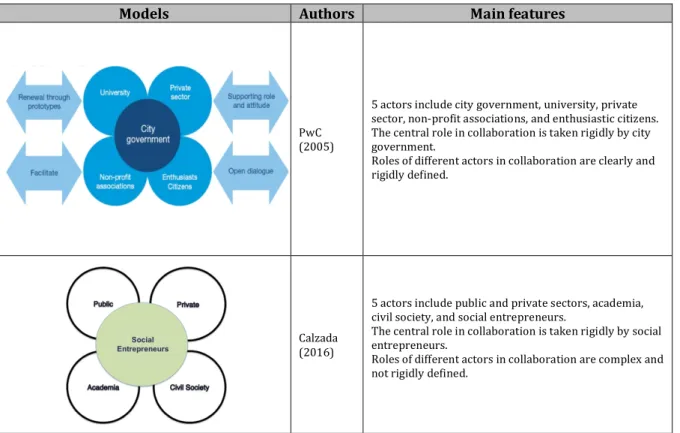

Table 1 - Thesis outline ... 4Table 2 - Models of penta helix collaboration ... 7

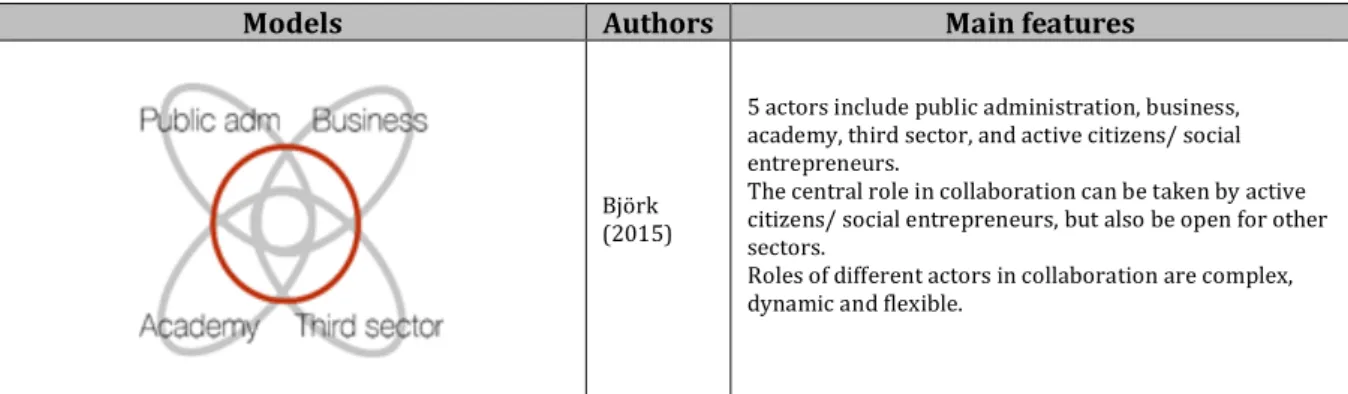

Table 3 - Synthesis of the main models for initial conditions in cross-sector collaboration, from a literature review from 1998 to 2018 ... 9

Table 4 - List of interviewees ... 18

Table 5 - List of collected documents ... 19

Table 6 - Example of interview coding and analysis process ... 20

Table 7 - Example of document coding and analysis process ... 21

Table 8 - Development phases of ReTuren in accordance with Mulgan (2006)’s social innovation initiative stages of development ... 34

List of Figures in Appendices

Figure A1 - Façade of ReTuren, included in the meeting place of Lindängen (left). Upcycled piano as result of an activity with the local community (right). ... viFigure A2 -ReTuren's roll-up, informing of its activities as an upcycling station (left). Waste deposit solutions (right), for recyclables (above) and big and hazardous waste (below). ... vi

List of Tables in Appendices

Table A - Detailed list of interviews, in terms of place and time ... ix1. Introduction

This chapter presents the background and research problem on initial conditions for establishing penta helix cross-sector collaboration in co-produced social innovation. The research purpose and research question are presented afterwards. The methodology for research is presented with a focus on the philosophical approach and research design. The chapter ends with a detailed description of the thesis structure.

1.1. Social innovation: the need for penta helix collaboration

Social innovation brings about sustainability which is regarded as a new paradigm for development, consisting of innovation and change to replace traditional models of development (Fifka & Idowu, 2013). Social innovation can be defined as “innovative activities and services that are motivated by the goal of meeting a social need and that are predominantly developed and diffused through organisations whose primary purposes are social” (Mulgan, Tucker, Ali, & Sanders, 2007, p. 8). It introduces new business models and market-based mechanisms that offer sustainable economic, environmental and social prosperity (INSEAD, 2018). It can also have a great impact on the development of local community (Rondinelli & London, 2003), by enhancing acknowledgment of these three pillars of sustainability. This recognition itself forms the fourth pillar of cultural sustainability1 (Soini & Birkeland, 2014). Co-production is one of the new ways to social innovation by “delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their families and their neighbours” (Boyle & Harris, 2009, p. 11). The increasing focus on co-production in the public sector has led to the establishment of platforms to explore community issues through the engagement of citizens and representatives from different sectors (Ehn, Nilsson, & Topgaard, 2014; Huybrechts, Dreessen, Schepers, & Salazar, 2016) and to explore collaborative relationships in public services (Botero & Saad-Sulonen, 2013; Hillgren, Seravalli, & Emilson, 2011; Lenskjold, Olander, & Halse, 2015). In fact, the number of social innovation projects related to co-production are rising, which can play a major role in innovations in the everyday life of people (Emilson, Hillgren, & Seravalli, 2014). In order to produce useful outcomes in co-produced social innovation, it is important to have the participation of and collaboration with relevant stakeholders that cross organizational boundaries and jurisdictions (Bason, 2010; Sørensen & Torfing, 2011). The reason is that collaboration is an important source of new knowledge and practices (Hermans, Klerkx, & Roep, 2015). Different parties look for others to establish collaboration, in accordance with their compatibility in terms of resources, knowledge, power or network position (Ahuja, 2000; Valk, 2007). In social organisations, the acceleration of social innovation can be supported by practitioner networks, allies in politics, strong civic organisations and the support of progressive foundations and philanthropists (Mulgan et al., 2007). Due to the complexity of social obstacles (Becker & Smith, 2018), cross-sector collaboration in social innovation is considered a useful social problem-solving mechanism among organizations (Waddock, 1989). Bryson et. al (2006) proposes that cross-sector collaboration as “shared-power arrangements” can be considered as a new organizational form that can collectively work towards solving complex public problems. It is also more creative and resilient than individual social innovation efforts (Rondinelli & London, 2003).

The penta helix model is conceptualized as a suitable collaborative approach to social innovation (Björk, 2015). It is a form of collaboration with the inclusion of five sectors in cross-sector collaboration, i.e. public administration, business, academia, third sector, and citizens (Björk,

1 Referring to Soini and Birkeland (2014)'s concept of sustainability, which consists of four interconnected pillars: social, economic, ecological, and cultural sustainability. The fourth pillar is considered to be instrumental to achieving the goals of the first three pillars through the linkage of perceptions and values.

2015; Calzada, 2016; Halibas, Sibayan, & Maata, 2017). It enhances a culture of innovation among actors from different sectors (Halibas et al., 2017). It is formulated based on the triple helix model University – Industry – Government relations (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000) with the addition of two important actors: the civil society, or the third sector, and active citizens or social entrepreneurs. These added elements make the penta helix model become fitter in the context of co-produced social innovation than the triple helix model as it not only shows the knowledge or innovation logic but also democratic logic (Björk, 2015).

1.1.1. ReTuren: a co-produced social innovation initiative

An example of co-produced social innovation is ReTuren, an upcycling station, a co-produced public platform for waste handling and prevention in Malmö, Sweden. It is a co-produced initiative involving penta helix collaboration among the public administration (Malmö Municipality and VA SYD), business (SYSAV), academia (Malmö University), the third sector (STPLN, RSMH), and Lindängen citizens (Altundal & Upadhyaya, 2017; Nilsson, 2016; Seravalli, Agger Eriksen, & Hillgren, 2017). Such collaborations have been important for the establishment and running of ReTuren since they support fruitful synergies between local actors for the interests of citizens (Seravalli, Hillgren, & Agger-Eriksen, 2015). It also went through two development phases, a pilot project and a permanent organisation, which offer different contexts for collaboration. The idea of ReTuren was to "take a holistic approach to promoting sustainable waste management and minimizing waste" (VA SYD, 2016), by creating a waste deposit facility that would help the residents not to drive to the recycling centres in the outskirts. ReTuren aimed explicitly at working with waste prevention by encouraging citizens to reuse and upcycle materials rather than only dispose them. Therefore, it was considered relevant to develop connections with the local context and engage citizens (Seravalli et al., 2017). It is considered to be greatly contributing to the “holistic sustainability” of the region (Seravalli, 2017). In fact, ReTuren's vision is to "be a platform for social, ecological, economic and cultural sustainability and innovation" (Altundal & Upadhyaya, 2017). By becoming more than just a waste deposit facility, it provides inclusive activities that bring citizens together, which fosters both environmental and social sustainability. The local economic sustainability is also improved by opportunities to share, exchange or buy goods at a reduced price as well as to repair broken appliances and bicycles. It also contributes to culture sustainability by creating a common way of meaning among citizens and other stakeholders.

1.2. Initial conditions for penta helix collaboration: a research problem

Social innovation has received increasing attention due to the growing recognition of gaps between services provided by state or traditional business and societal needs (Fifka & Idowu, 2013). It is likely to occur within actors in an interdisciplinary environment (Mulgan, 2006). However, it is known that cross-sector collaboration is very complex and dynamic when operating in diverse contexts. Thus, it is unlikely to have the same formula to establish such collaboration in all contexts (Bryson et al., 2006; Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). Furthermore, according to Bryson et al. (2006), initial conditions affect and influence the success of all forms of cross-sector collaboration. Therefore, although studying cross-sector collaboration and providing practical guidance to policy makers regarding its design and implementation is considerably challenging, it needs to be addressed. Otherwise, important opportunities for creating public value will be missed.

Moreover, when a penta helix model of cross-sector collaboration is used, the complexity of the social innovation system remarkably increases, given the number and inter-disciplinary participants involved (Björk, 2015). Given the importance and complexity of the penta helix collaboration for social innovation, there is a necessity to better understand in which conditions this form of collaboration can be established.

There is also a need for research on how to (re)connect people and the planet in fundamentally new ways in social innovation (Simo & Bies, 2007). Co-production is seen as an approach for developing and delivering collaborative and locally-situated public services (Seravalli et al., 2017). Therefore, it is relevant to explore the initial conditions for penta helix collaboration in the context of co-production.

As individuals and organisations that launch and lead a co-produced initiative, hereby called core co-producers, are directly involved in the establishment of the collaboration. These actors can be perceived as having a higher degree of knowledge about the circumstances in which the collaborations were formed than other co-producers. Therefore, it is important to investigate these conditions through the perspectives of these actors.

Furthermore, little literature or empirical research has been found on the conditions for establishing penta helix collaboration in co-produced social innovation, which is a gap that this research aims to fulfil.

1.3. Purpose

Based on the above-mentioned significance and novelty of the research problem, the thesis aims to investigate the initial conditions for the establishment of penta helix collaboration, from the perspectives of core co-producers. The research is focused on the context of co-produced social innovation.1.4. Research Question

To achieve the research purpose, a research question was formulated based on the perspectives of core co-producers: What are initial conditions for establishing penta helix collaboration in co-produced social innovation?1.5. Methodology

1.5.1. Ontological and epistemological ground

The thesis takes the social constructionist approach to fit with the research focus on social perspectives and outcomes. This is also in line with our research topic of penta helix cross-sector collaboration as complex social relationships which the positivistic approach does not help to understand or explore (Arbnor & Bjerke, 2008). This philosophical approach is reflected through the research approach, data collection and analysis where different opinions, knowledge of issues, and experience of research participants are respected and presented (6 & Bellamy, 2012). It also means that the researchers’ academic pre-understandings and values are included in the data interpretation and thus, affect the research result (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Stake, 1995). Furthermore, taking the social constructionist perspective, the thesis acknowledges the ability of readers to generalise the research findings by their own sense and experience. Thus, by presenting the research purpose, context, methodology and methods, the research aims to help readers understand researchers’ own pre-understandings and background for their decision on generalisation in other contexts. 1.5.2. Research approach The character of this thesis is explorative as it aims to explore an area of little empirical knowledge in the literature in order to have new insights about the perspectives of core co-producers on the conditions to establish penta helix collaboration in the context of co-produced social innovation in the public sector (Blaikie, 2003; Brown, 2006; Jupp, 2006; Kumar, 2011). It also takes on the inductive approach where the researchers simultaneously worked with theoretical pre-understandings and empirical data without having a fixed frame of reference. This approach

helped the researchers to be open to unpredicted findings in the research process (6 & Bellamy, 2012). A qualitative approach was chosen as it helped to explore diverse insights of research participants in the research’s specific context (Silverman, 2014).

1.6. Thesis structure

The thesis is divided into six chapters based on the logic of the social constructionist approach. After the introduction of the research problem, purpose, and question in Chapter 1, the thesis presents the pre-understandings of the researchers on concepts of co-produced social innovation and cross-sector collaboration and models of penta helix and initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration in Chapter 2. From these pre-understandings, the methods to conduct research are described in Chapter 3, followed by data presentation and analysis in Chapter 4. Discussion on the data analysis findings to answer the research question as well as provide new insights in relation with the literature is presented in Chapter 5. Finally, Chapter 6 presents the conclusion of the research, its contributions to theory and practice, and implications for future research. Each chapter begins with an overview, defining its main contents and structure. There are also figures and tables to help readers to acquire a better understanding of the text. The outline of the thesis is summarised in Table 1. Table 1 - Thesis outlineChapter 1 Introduction Description of background, research problem, research purpose and question, methodology, and thesis outline

Chapter 2 Pre-understandings Presentation of concepts of co-produced social innovation and cross-sector collaboration and models of penta helix and initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration

Chapter 3 Methods Case-study design, case description, methods to collect and analyse collection, and analysis of data

Chapter 4 Results and data analysis Presentation and analysis of data

Chapter 5 Discussion Discussion of answers to the research question and aim in relation with the literature

Chapter 6 Conclusion Summary of the findings, its contributions to theory and practice, and implications for future research

2. Pre-understandings

This chapter presents the research’s pre-understandings on theoretical concepts of social innovation and its relation to co-production, cross-sector collaboration and the penta helix model. The concept and literature review of models of initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration in social innovation projects are also described. In accordance with the social constructionist approach, these pre-understandings shape the research design and the interpretation of data as presented in Chapter 3 and 4 respectively.

2.1. Social innovation and co-production: an environment for cross-sector

collaboration

There seems to be no commonly agreed upon definition of social innovation (Phillips, Lee, Ghobadian, O’Regan, & James, 2015). However, Mulgan et al. (2007)'s definition as presented in section 1.1 is considered to be most extensive and useful to understand the characteristics of social innovation. It clearly distinguishes between social innovation and business innovations which are motivated by profit maximisation and distributed through organisations that are mainly motivated by profit maximisation.

Social innovation has three key characteristics that closely relate to the importance of collaboration. Firstly, they are usually new combinations or hybrids of existing elements, rather than being completely new. Secondly, the implementation of social innovation normally requires cutting across organisational, sectoral or disciplinary boundaries (and frequently search for other sources of value through arbitraging ideas and knowledge). Thirdly, social innovation create captivating new social relationships between formerly divided individuals and groups. This fact is critical for the participants, by fostering the spreading and embedding of the innovation while empowering the innovation environment in which each innovation leads to more innovations (Mulgan et al., 2007). According to Mulgan (2006), a social innovation initiative is developed in four phases. The first phase stands for the recognition of need that is not being met, combined with an idea of how it could be met. The second phase refers to the testing of such idea in practice, while the third phase occurs when the idea is proved to solve the need and thus can grow and be replicated, adapted, or franchised. The fourth phase of social innovation comprises the process of continuous learning and adjustment of the initial idea into new appropriate forms, which can be very different from the expectations of the creators. Co-production is a new way to implement social innovation in public services that build on explicit (and occasionally formalised) collaborations between public providers, citizens and societal actors. It aims to deliver services that respond better to specific local conditions while activating and empowering citizens (Bason, 2010; Boyle & Harris, 2009; Cahn, 2008). Co-production is perceived as a value in itself, where the increase of citizen involvement as an objective to be met, together with being more effective, better adapted to local needs, creating societal connections and empowering citizens (Penny, Slay, & Stephens, 2012; Stoker, 2006; Voorberg, Bekkers, & Tummers, 2015). Moreover, when activities are co-produced in this way, both services and neighbourhoods become far more effective agents of change (Boyle & Harris, 2009, p. 11). Social innovation and co-production are concepts that have been “embraced as a new modernization or reform strategies for the public sector” (Voorberg, Bekkers, & Tummers, 2013, p. 3). In fact, policy makers and politicians consider co-production with citizens as “a required condition to create innovative public services” which truly meet the needs of citizens regardless of many societal challenges. Hence, co-production seems to be considered as “a cornerstone for social innovation in the public sector” (William Voorberg et al., 2013, p. 3). According to these authors, the core of social innovation is based on the active involvement of citizens into public service delivery, which is often recognized as co-creation or co-production. Co-production occurs within the production process which precedes the usage stage, according to Lusch and Vargo (2006). This process is outlined as a sequence of operational activities linked in a network (Achrol

& Kotler, 1999) with each set of activities leading to the next (Porter, 1985). The activities include intellectual work of initiating and designing, collection of resources and other managing activities that will lead to the creation of a product that will be used afterwards, as well as ensuring its performance during use (Etgar, 2008). The concept of core co-producers as presented in section 1.2 was created by the researchers in order to clarify the role of organisations and individuals in the establishment of co-production. It was based on the concept of core participants by Seravalli et al. (2015) in co-designing forms for urban commons. However, ‘core co-producer’ is broader but also more specific than ‘core participant’ in that it includes both individuals and organisations that participate in context of co-production in social innovation. This directly connects them to the establishment of cross-sector collaboration for social innovation as the topic of this thesis.

2.2. Cross-sector collaboration

There are many definitions of collaboration in the literature. According to Thomson and Perry (2006), it is defined “as a process in which autonomous actors interact through formal and informal negotiation, jointly creating rules and structures governing their relationships and ways to act or decide on the issues that brought them together; it is a process involving shared norms and mutually beneficial interactions” (Thomson & Perry, 2006, p. 23). This definition is considered useful for analysing processes of collaboration, which can be affected by internal and external conditions.

In order to clarify the boundary of the concept, it is important to differentiate between collaboration and cooperation/coordination. Cooperation and collaboration can differ concerning their depth of interaction, integration, commitment, and complexity, with cooperation in low level of the scale and collaboration in the high (Alter & Hage, 1993; Denise, 1999; Himmelman, 1996; Mattessich & Monsey, 1992). According to Gray (1989), cooperation and coordination can happen as part of the early process of collaboration, as the later refers to a longer-term unified process through which different parties understand their perspectives of a problem, positively analyse their differences and look for solutions that go further than they imagined as possible and implement those solutions jointly.

Cross-sector collaboration is defined as “partnerships involving government, business, non-profits and philanthropies, communities, and/or the public as a whole… [through] the linking or sharing of information, resources, activities, and capabilities by organizations” (Bryson et al., 2006, p. 44), a mutual goal of solving social problems that are beyond the capabilities of each individual organisation (Simo & Bies, 2007). This definition is considered useful to connect cross-sector collaboration to the context of social challenges and social innovation.

Cross-sector collaboration is considered an increasingly important strategy to solve global and societal challenges (Becker & Smith, 2018). It is the sharing of power in the modern society and criticism of the effectiveness of governments’ individual actions that make cross-sector collaboration become a current growing trend (Crosby & Bryson, 2005).

A key reason for the establishment of cross-sector collaborations is the recognition of public managers’ and policy makers’ that government of the impossibility to solve a public challenge on its own (Bryson et al., 2015). Non-governmental partners may have additional expertise, technology, relationships, and financial resources that can be deployed in a joint effort (Holmes & Moir, 2007).

Cross-sector collaboration in social innovation is essential because of the complexity of social obstacles in this century (Becker & Smith, 2018). It is also more creative and resilient than individual social innovation efforts (Rondinelli & London, 2003). It is also described as “social problem-solving mechanisms among organizations” (Waddock, 1989, p. 79).

According to the systems of innovation approach which takes innovation as a systemic and interactive process (Freeman, 1988 as cited in Phillips et al., 2015) cross-sector collaboration

plays a critical role to both social innovation and business innovation. However, its approaches in these two systems are clearly different. Whereas cross-sector collaboration in business innovation, or the conventional innovation system, is focused on commercialisation (Björk, 2015), the social innovation cross-sector collaboration emphasizes a civic perspective which enhances the role of the civil society and active citizens. These values are directly connected to the issue of which actors are involved in the innovation ecosystem (Hansson, Björk, Lundborg, & Olofsson, 2014) which is the basis of the triple helix, quadruple helix, and penta helix collaboration models.

2.2.1. Penta helix model of cross-sector collaboration

There are several penta helix models of cross-sector collaboration (Björk, 2015; Calzada, 2016; PWC, 2005). Overall, it is an approach to collaboration with the inclusion of five sectors, viz. public sector, private sector, academia, third sector, and citizens or social entrepreneurs. It was first developed by (PwC, 2005) with the City government at the centre of the model based on the logic of knowledge, innovation and economic growth. By contrast, in the penta helix models developed by Björk (2015) and Calzada (2016), the citizens or social entrepreneurs can take the central spot. This arguably fits in the context of social innovation as it not only shows the knowledge or innovation logic but also democratic logic (Björk, 2015). The difference between the models drawn by Björk (2015) and Calzada (2016) is that the former shows the dynamic and complex relationships among the actors and emphasizes the flexible connection between the citizens or social entrepreneurs with all of the other actors. Therefore, Björk (2015)’s model is considered more useful in the complex context of co-produced social innovation. Table 2 synthesizes the distinct features of these three penta helix models.

Table 2 - Models of penta helix collaboration

Models Authors Main features

PwC (2005) 5 actors include city government, university, private sector, non-profit associations, and enthusiastic citizens. The central role in collaboration is taken rigidly by city government. Roles of different actors in collaboration are clearly and rigidly defined. Calzada (2016) 5 actors include public and private sectors, academia, civil society, and social entrepreneurs. The central role in collaboration is taken rigidly by social entrepreneurs. Roles of different actors in collaboration are complex and not rigidly defined.

Models Authors Main features Björk (2015) 5 actors include public administration, business, academy, third sector, and active citizens/ social entrepreneurs. The central role in collaboration can be taken by active citizens/ social entrepreneurs, but also be open for other sectors. Roles of different actors in collaboration are complex, dynamic and flexible. There are several ways to define the boundaries among several or all the five sectors in penta helix collaboration (Halibas et al., 2017; Silvestre, Catarino, & Araújo, 2016; Van Der Wal, De Graaf, & Lasthuizen, 2008). Among those, the definition of the boundary put by Halibas et al. (2017) is based on the contribution of each sector to social innovation by using their own resources and expertise. This definition is considered unclear because of high flexibility. However, it is helpful for analysing the dynamic, flexible and complex functions and contributions of sectors in the Björk (2015)'s penta helix model. In detail, the academia promotes and enables the circulation and implementation of innovation and entrepreneurship, enriches industries with new technology and research. The government supports and promotes innovation through public investments in research and development, knowledge infrastructures, laws and policies, etc. The industry supports innovation by research funding, product development and commercialization. The civil society engages in the social and economic development by actively taking part in regional development programs. The social entrepreneur initiates societal change for sustainability and links different sectors together as they can come from any sectors (Dhesi, 2010 as cited in Halibas, 2017).

2.2.2. Initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration

There are many theoretical models and frameworks of conditions or determinants for collaboration (Boudreau & Bernier, 2017; Gray, 1985; Hermans et al., 2015; Hood, Logsdon, & Thompson, 1993; Oliver, 1990; San Martín-Rodríguez, Beaulieu, D’Amour, & Ferrada-Videla, 2005). These frameworks are based on different concepts of “condition” as contingencies of collaboration formation (Hermans et al., 2015; Oliver, 1990) determinants of successful collaboration (Gray, 1985; San Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2005), obstacles to the collaboration process (Boudreau & Bernier, 2017), and factors that affect collaborations (Hood et al., 1993). Since the purpose of the thesis is to explore how to establish the cross-sector collaboration, not how to facilitate or maintain successful collaboration, the concept of “condition” as contingencies for collaboration formation, or initial conditions, is chosen as a basis for the analysis. Based on our literature review from 1998 to 2018, major cross-sector collaboration frameworks have been developed and comprised of models for initial conditions and/or antecedents of cross-sector collaboration (Ansell & Gash, 2007; Bryson et al., 2015; Crosby & Bryson, 2005; Thomson & Perry, 2006). It is notable that to our best knowledge, there has not been any studies that formulate or focus on any stand-alone models of initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration. With the common context of cross-sector collaboration in public management, the major cross-sector collaboration frameworks share the view that initial conditions are variables present at the beginning of the collaboration. However, none of the articles draw the clear boundary between concepts of initial conditions and cross-sector collaboration processes or structures.

Table 3 presents the synthesis of the main models for initial conditions for cross-sectoral collaboration.

Table 3 - Synthesis of the main models for initial conditions in cross-sector collaboration, from a literature review from 1998 to 2018 Publication Cross-sector collaboration frameworks (Main components) Models of initial conditions

(Main components) Relations between antecedents/ initial conditions and other components Bryson et al. (2006) Initial conditions Process Structure and governance Contingencies and constraints Outcomes and accountabilities General environment • Turbulence • Competitive institutional elements Sector failure Direct antecedents • Conveners • General agreement on the problem • Existing relationships networks Initial conditions influence and have some overlapping with the process, structure and governance, and outcomes and accountabilities Thomson and

Perry (2006) Antecedents Processes Outcomes High levels of interdependence Need for resources and risk sharing Resource scarcity Previous history of collaboration efforts Resource demand and supply Complex issues Antecedents influence processes Ansell and Gash (2007) Starting conditions Collaborative process Outcomes Imbalances between the resources or power of different stakeholders Incentives for collaboration of stakeholders Past history of conflict or cooperation among stakeholders Starting conditions influence the collaborative process. Chen (2010) Antecedents Processes Perceived effectiveness Resource acquisition Organisational legitimacy

• Requirements from funding agency • Reputation enhancement • Building future relationships Partners' characteristics • Shared vision • Prior working relationships Supply-side imperfection Antecedents influence processes Bryson et al. (2015) General antecedents and initial conditions, drivers, and linking mechanisms Collaborative processes Collaboration structures Conflicts and tensions Accountabilities and outcomes General antecedents - Resources - Institutional environment • Mandates • Window of collaborative opportunities • Vulnerable to policy/ political change - Need to address public issues • Sector failure • Resources from non-governmental partners to solve issues Initial conditions, drivers, and linking mechanisms - Agreement on initial goals • Authoritative texts - Recognized interdependence - Pre-existing relationships • Initial leadership - Consequential incentives - Nature of tasks General antecedents influence initial conditions, drivers and linking mechanisms, and accountabilities and outcomes. Initial conditions, drivers and linking mechanisms influence collaborative processes and structures.

From the review of these models, it can be seen that most models comprise of conditions of previous relationships, issues of resource scarcity, and shared goals. Bryson et al. (2015)’s model as a synthesis of all the frameworks from 2006 to 2015 is the most comprehensive one on

elements of antecedents and initial conditions or drivers of cross-sector collaboration in the public sector. It is also connected to co-produced social innovation because it includes findings from recent research concerning the importance of partnerships dedicated to public policy or public problem-solving (Sandfort & Moulton, 2014; Scott & Meyer, 1991). Furthermore, this model has also been referred to in other researches on projects in the public sector as one of the important models in the area of cross-sector collaboration (e.g. Lubell, Mewhirter, Berardo, & Scholz, 2017; Ospina, 2017; San Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2005; Sedgwick, 2016; Vangen, 2017). Therefore, this model plays an important role as a pre-understanding to investigate the conditions for establishing effective cross-sector penta helix collaboration.

2.2.3. Bryson et al. (2015)’s model on initial conditions for cross-sector collaboration

Bryson et al. (2015)’s model comprises of two types of conditions, viz. general antecedent conditions and initial conditions, drivers, and linking mechanisms (or initial conditions for short). These conditions are complements to each other and considered to be in chronological order as that antecedents lead to initial conditions. The boundary between these conditions and other categories in the framework lies in the time of happening, in that conditions are factors that exist before actors start collaborating to solve the common problem (see Figure 1). Figure 1 - Framework of cross-sector collaboration by Bryson et al. (2015)

Antecedents conditions include the availability of resources, characteristics of the institutional environment, and the need to address complex public issues, according to Bryson et al. (2015). Resources as a condition can be referred to both financial assets as well as skills or knowledge,

Bryson et al. (2015) is not explicit in his explanation, but it seems to refer to financial resources as an antecedent condition for establishing cross-sector collaborations as means to support development of a shared interest.

The institutional environment comprises of normative and regulatory elements which must be complied by organisations for their existence, especially in the public sector (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott & Meyer, 1991). Regarding the institutional environment, it is possible to find

mandates, window of collaborative opportunity and vulnerable policy/political change as

antecedent conditions. The first condition refers to the fact that cross-sector collaborations can be forced to be established if it is a requirement from government policies or funding programmes (Stone, Crosby, & Bryson, 2013). The second condition, window of collaborative opportunity, is seen as seizing the opportunity of the jointure of relatively non-contingent flows as a problem situation and a solution flow to the form of collaboration (Kingdon, 1995). Thereby, the entrepreneur then is able to gather resources and partners on this opportunity (Lober, 1997). The vulnerability of policy/political change is also mentioned as an antecedents condition, though no clear definition is given. It is then understood as the political decisions and its consequences as promoters of the establishment of collaboration as the case used to explain this condition refers to the influence of politics in promoting cross-sector collaboration.

The need to address a public issue is seen as a determinant condition in the establishment of collaborations. This is based on the acknowledgment by public managers/policy of sector failure that the government or other sector is unable to solve a public problem by themselves or is likely to fail in doing so (Bryson et al., 2006), and by collaborating with third sector, community or private sector they can reduce the risk and provide more effective solutions (Kettl, 2015). Cross-sector collaboration is seen to be influenced by the degree to which single efforts to solve a public problem have failed (Bryson et al., 2006). The society relies on the strengths of different sectors - for-profit, public, and non-profit - to overcome the weaknesses or failures of the other sectors and to contribute to the generation of public value. If all three sectors fail, we have a public value failure (Bozeman, 2002) that can be addressed in one of several ways: we can live with the problem, engage in symbolic action that does little to address the problem, or mobilize collective action to fashion a cross-sector solution that holds the promise of creating public value. According to Bryson et al. (2006, p. 46), “public policy makers are most likely to try cross-sector collaboration when they believe the separate efforts of different sectors to address a public problem have failed or are likely to fail, and the actual or potential failures cannot be fixed by the sectors acting alone”. Moreover, non-governmental collaborators may have different expertise, technology, relationships, and financial resources that can be applied in the collaboration. This condition is named by Bryson et al. (2015) as resources from nongovernmental partners to solve

issue.

Initial conditions encircle the meaning of pre-existing histories and relationships (positive or

negative), agreement on collaborative objectives and perceived interdependence among members, and the availability of leadership.

The agreement on initial aims or problem definition is also an important condition for establishment cross-sector collaborations (Gray, 1989; Waddock, 1986). This can elucidate the role and interest that an organization has in resolving a social problem and how much efforts are required from other organizations to solve the problem. Logsdon (1991) finds that both acknowledged self-interest and interdependence are required prerequisites for the establishment of the collaboration.

Authoritative text is the formal agreement among organisations to collaborate, which enhance the

credibility of the collaboration. Without this condition, the collaboration can become harder to achieve, especially when there is a lack of administrative ability (Babiak & Thibault, 2009).

The shared vision or agreement on common goals is also seen as important facilitating condition (Gray, 1985). In fact, collaborations are, by definition, promoted to jointly achieve an outcome that wouldn’t be achieve separately. Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh (2012) also highlight shared motivation as important to internal collaboration dynamics.

Recognized interdependence is the interdependence of stakeholder organisations when

addressing the problem (Simo & Bies, 2007).

Bryson et al. (2006) states that cross-sector collaborations are more prone to succeed when one or more connecting mechanisms (powerful sponsors, common agreement on the problem, or existing networks) are set at the time of their initial establishment.

Pre-existing relationships or existing networks also play an important role because it is regularly

through these networks that partners evaluate the trustworthiness of other partners and the legitimacy of crucial stakeholders. Jones, Hesterly, and Borgatti (1997) and Ring and Van de Ven (1994) define this as the degree of structural embeddedness: the more partners have interacted in positive ways in the past, the more social mechanisms will enable coordination and safeguard exchanges. However, if previous relationships do not exist, then partnerships are likely to emerge more incrementally and start with minor and informal arrangements that do not demand significantly trust (Gulati, 1995; Ring & Van de Ven, 1994).

Initial leadership can be seen through the boundary-spanning leaders with credibility in multiple

arenas touched by the problem. They are acknowledged as conveners (Kastan, 2000) and they can facilitate the establishment of the collaboration (Gray, 1989; Waddock, 1986). Conveners are perceived as being one of the facilitating conditions on the problem-setting phase. According to Gray (1989), they can group an initial arrangement of stakeholders. In fact, influential sponsors or brokering organizations draw attention to an important public problem (Crosby & Bryson, 2005). Conveners can be “powerful individuals, such as a mayor or chief executive officer, or organizations, or a private foundation” (Bryson et al., 2006, p. 46).

According to Crosby & Bryson (2010)it is especially important the involvement of committed, boundary-spanning leaders with a “collaborative mindset". Also needed is the ability to structure the issue so that the different organizations can understand its importance and its relevance to them (Page, 2010). Other significant individual leadership characteristics include a belief that a problem needs to be addressed, relevant educational qualifications, and age (Esteve, Boyne, Sierra, & Ysa, 2012; Silva & McGuire, 2010).

Specific leader characteristics are required to establish cross-sector collaboration, such as

commitment and having a mindset for collaboration (Cikaliuk, 2011).

Consequential incentives are referred to as either internal drivers (i.e. problems, needs of

resources, interests, or opportunities) or external drivers (i.e. situational or institutional crises, threats, or opportunities) for collaborative action (Emerson et al., 2012).

The nature of the task also plays an important role in establishing cross-sector collaboration (Alter & Hage, 1993; Provan & Kenis, 2008). Though it is not defined in Bryson et al. (2015), its example is provided as the impact of the disastrous conditions by Hurricane Katrina on collaborative actions (Simo & Bies, 2007).

2.2.3.1. Criticism of the model

Despite being the most comprehensive models to date in the literature, Bryson et al. (2015)’s model can be criticised regarding the complex and blurring division of types and themes of conditions as well as unclear definition of several concepts.

First, the division of antecedent and initial conditions is considered to be based on a chronological rationale as well as their influence on other categories, such as processes, structures, and outcomes. This makes it largely difficult to draw the boundary between the two of conditions in reality, because both the timing and influences are hard to divide. During the establishment of

collaboration, the conditions that Bryson et al. (2015) perceives as initial can become antecedent and vice-versa, depending on the context. For example, Bryson et al. (2015) identifies pre-existing

relationships as an initial condition but as it may have existed for a long time and influenced the window of collaborative opportunity, it is hard to be recognized as an antecedent or initial

condition.

Second, the logic of division of themes can be hard to understand as the conditions under some themes seem to have similar contents. For example, antecedent conditions of Resources and

Resources from non-governmental partners can be grouped as availability of resources because

they refer to the same concept but at different levels or in different perspectives. Authoritative texts can be included in Institutional environment given that the both conditions refer to laws and regulations. Consequential incentives and recognised independence can be considered repetitive as they are related to several other initial conditions, such as window of opportunity, resources and need to address public issues. Last but not least, the definition of many concepts and the conceptual division of themes seem to be not clear. Almost all the concept definitions are derived from different authors. Some of them do not have any definitions (e.g. nature of the task). This may be explained as the model was composed based on a literature synthesis.

It is noteworthy that the criticism of the model is based on the its presentation of theoretical concepts. This is part of the research pre-understandings. Therefore, in accordance with the inductive approach, it does not limit the collection or analysis of the data.

Based on the pre-understandings on concepts of social innovation, co-production, and models of penta helix collaboration and its initial conditions as presented in this chapter, the research was

3. Methods

This chapter presents the methods selected to conduct this research, including the case study design, data collection and analysis methods. An introduction of ReTuren as the case for study is also presented. Finally, the quality, ethics, and limitations of the research are explained.

3.1. Case study design

The case study method is chosen to collect qualitative data because it is suited to analysing complex phenomena from different perspectives and can collect a large amount of various data in order to analyse the little-known relationship (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Silverman, 2014). The thesis uses the a within-case research design to gain in-depth understanding of the case by formulating themes and patterns of initial conditions for penta helix collaboration in the context of the two phases of ReTuren (6 & Bellamy, 2012).

3.2. Case introduction

The specific focus and context of the research as penta helix collaboration in co-produced social innovation does not provide the researchers with a broad range of cases to choose from. ReTuren is a representative case of co-produced social innovation which is implemented by penta helix collaboration. It has also gone through two development phases of a pilot project and a permanent organisation, which offer different contexts for collaboration. Therefore, the characteristics of collaboration and development process of ReTuren led us to select this case for our study.3.2.1. The development of ReTuren

ReTuren is an upcycling station located in the neighbourhood of Lindängen, Malmö, Sweden. It is considered a platform for waste management and prevention. Some illustrative photos of this public platform can be found in Appendix I. Collaboration can be found in the two phases of the initiative development: the pilot project from 2012 to September 2016 (phase 1), and the part-time reopening, as a permanent organization, from October 2016 to the present time (phase 2) (Altundal & Upadhyaya, 2017; Seravalli et al., 2017) (see Figure 2). Figure 2 - Timeline of events in ReTuren’s development stages

It was originally designed by VA SYD (municipal association managing wastewater and water) in 2012 as a practical solution for deposit waste closer to the citizens (VA SYD, 2016). This concept is planned to replicate in another neighbourhoods in Malmö (Seravalli et al., 2017).

In August 2015, VA SYD opened ReTuren as a pilot project, which was planned to operate for one year (personal communications, 10-4-2018). It was a platform was not only a deposit site for hazardous and cumbersome waste, but also a meeting place to exchange and repair goods and participate in creative activities as a small makerspace (Altundal & Upadhyaya, 2017; Seravalli et al., 2017). ReTuren's project leader was from VA SYD and the project members were from collaborative organisations such as Malmö Municipality, Malmö University (MAU), STPLN, etc. In September 2016, VA SYD decided to end the pilot project sooner than originally planned (VA SYD, 2016). This sudden closing faced the protests of the local citizens (Nilsson, 2016; Seravalli et al., 2017). Nevertheless, VA SYD still wanted to “create a sustainable organization and concept that can work long-term and that could be applied throughout the city based on the positive learnings from the pilot project” (VA SYD, 2016).

After the closing, MAU and Malmö Municipality promoted meetings to better understand both success and challenges of the pilot project. Participants of these meeting included VA SYD, STLPN, Malmö Municipality, SYSAV, and other organisations as well as citizens (Seravalli et al., 2017). After the withdrawal of VA SYD as the project leadership, the Malmö Municipality took the ownership of the meeting place and turned it into a permanent organization. Although the mission remains the same, it was needed to redefine the terms of existing collaborations and rearrange the organisational structure.

Since the reopening, ReTuren’s organisational structure is constituted by a control group and a steering group. The first constitutes the managerial level of the organizations (e.g. Malmö Municipality, VA SYD), while the second groups the operational level, i.e. members from the participating organizations that work in the daily management of the meeting place (personal communications, 12-04-2018). Local citizens and organizations participate indirectly in the management of ReTuren by interacting with the control group.

All of the events in the development of ReTuren have significant impact on the establishment of collaboration among different actors, which will be analysed in Chapter 4.

3.2.1. Co-producers and core co-producers

As ReTuren is a case of co-production, the participants involved in the process are seen as co-producers.

Its co-producers collaborate in a penta helix formation, which includes five sectors, viz. the public administration (Malmö Municipality and VA SYD), business (SYSAV), academia (MAU), the third-sector (STPLN, RSMH), and Lindängen citizens (Altundal & Upadhyaya, 2017; Nilsson, 2016; Seravalli et al., 2017). It is noteworthy that the collaboration does not occur among these five sectors at the same time but between two, three, or four different sectors simultaneously for the purpose of establishing and operating ReTuren. From the role of organisations as mentioned above, it is possible to consider core co-producers of ReTuren as VA SYD, Malmö Municipality, MAU and STPLN in the first phase, and VA SYD, Malmö Municipality, MAU in the second phase (see Figure 3). VA SYD is a public organization controlled by several municipalities in the southwest Skåne (VA SYD, 2018). The organization is responsible for water and sanitation in these municipalities. Malmö municipal waste department is part of VA SYD.

Malmö Municipality is a government administration of the city of Malmö. In 2016, the governance structure of the local administrations was reorganised from region-based to jurisdiction-based. Therefore, in phase 1, the Malmö Municipality was represented by Southern district administration (Stadsområde Söder), while in phase 2, it was represented by the Cultural

department (Kulturförvaltningen), with close involvement of the local community centre (Framtidens Hus). Malmö Municipality provided the space for ReTuren to be installed in Lindängen. During the pilot-project Malmö Municipality contributed not only with knowledge about the neighbourhood but also as a connector to the local organizations. In the reopening phase it was the responsible for running the meeting place, including the staff employment (VA SYD, 2018).

STPLN is a non-profit association, a makers’ space and an incubator for creative projects. STPLN was involved in the project through the design researcher as established macro culture as a method of concept development within the ReTuren. STPLN contributed in the development of the ReTuren with knowledge and experience of developing completely new types of activities, citizenship and process-oriented learning as well as workshops (VA SYD, 2018).

SYSAV is the south Skåne regional waste management company. It was involved in the project by contributing staffing on behalf of VA SYD, and by providing knowledge and experience in the management of hazardous waste. SYSAV also co-produced the events organized by ReTuren for sustainable waste management, where their environmental educator contributed to activities aimed at young people (VA SYD, 2018).

MAU is a public education institute in Malmö. During the pilot project, MAU contributed to development of ReTuren concept and its activity as researcher for co-production introducing and applying concepts as infrastructuring and communing. In phase 2, MAU participated as a facilitator in the process of reformulating the organizational model of ReTuren. Other participants who are not directly involved in the project leadership and decision-making process, but only in the co-production process are considered only as co-producers, like SYSAV and the local citizens. Figure 3 - Organizational structure for both phases of ReTuren

3.3. Data collection methods

The thesis used primary data collected from interviews to explore the perspectives of core co-producers on the conditions to establish penta helix collaboration in the context of co-produced social innovation projects and organisations in the public sector (the primary and sub- research question).

Secondary data collected from document analysis was used as a complement to primary data to answer both research questions to provide more information about the interviewees’ perspectives as well as contextual information about the project. Document analysis was also conducted according to a direct request of one interviewee from MAU in an email interview, as mean to complement the answers provided.

3.3.1. Interviews

Interviews were conducted to collect data about individual perspectives of the cross-sector collaboration in ReTuren, including their interpretation of what had occurred and what they considered as important or less important. In line with the social constructionist approach, a semi-structured technique was applied when conducting the interviews with the purpose of being flexible and facilitating the freedom of thoughts (Silverman, 2014).

Interviewees were selected based on the role of their organisations during the collaboration within ReTuren scope as well as their roles in ReTuren in its two phases. Because the purpose of the thesis is to explore about the conditions from the perspectives of core co-producers, all of the interviewees were chosen based on their direct involvement in and contribution to ReTuren in one or both of its phases. The interviewees were also selected based on their work positions (i.e. managerial and operational level) in ReTuren and their host organisations to acquire a variety of perspectives on the collaboration based on their responsibilities in the organisations. The interviewee selection processes were conducted based on the consultation of the following four sources: (i) agreements on operating and collaboration of ReTuren signed among different organisations, (ii) the ReTuren webpage newspaper and journal articles on the project, (iii) interviewees' recommendation as a snowball effect based on their knowledge and experience of ReTuren, and (iv) interviewees' narration about their jobs in ReTuren. As a result of these selection processes, a total of eight interviewees were selected to conduct semi-structured interviews (see Table 4).

There are several methods to collect information from interviews, viz. interview in person or by phone, and mail questionnaire (Arbnor & Bjerke, 2008). The researchers conducted the majority of the interviews (six out of eight) in person for two reasons. First, it created a low level of standardization for freedom of thoughts from interviewees. Second, researchers could ask interviewees additional questions during the interviews to clarify or let the subjective meanings of interviewees develop. However, due to the unavailability of the interviewees, one out of eight interviews, was conducted by phone and one via mail questionnaire.

Each interview took from forty minutes to one hour to conduct. All the personal and telephone interviews were recorded and transcribed. All the interviews were conducted in the English language. One transcript of an interviewee was sent back to the interviewee for verification based on their request.

The interview guide was based on Bryman (2016)’s recommendation on interview question design (see Appendix II). Based on the inductive approach, it was first constructed broadly based on the individual, organisational, and network perspectives to explore the context, background, relationships of organisations and roles of individuals in the project. After that, the questions were narrowed down to focus on the conditions for establishing penta-helix cross-sector collaboration in the project and its linkage to sustainable development of the project and local community. The interview guide was tested as a prototype and revised in accordance with the role of interviewees and their organisations in the penta helix cross-sector collaboration. During the interviews, the researchers avoided to mention or pre-define theoretical concepts or terms so that interviewees could express their own understandings and opinions of those concepts.

Table 4 - List of interviewees “-“ Not directly involved 3.3.2. Documents

The documents were collected, first, by requesting the interviewees to provide relevant documents about the project, including their perception about the collaboration in the project. Interview Level Phase 1 Phase 2

Interviewee Method Organisation Involvement in ReTuren Organisation Involvement in ReTuren

I1 Personal Operational VA SYD Project leader - Development engineer VA SYD Member of control group - Development engineer I2 E-mail MAU Project member Embedded Co-Researcher MAU Collaboration facilitator Researcher for a project in ReTuren I32 Personal Southern district administration (Malmö Municipality) Project member - Development Engineer Cultural Department (Malmö Municipality) Coordinator – member of control and steering group - Development Engineer I4 Personal Southern district administration (Malmö Municipality) Project member Community Centre (Malmö Municipality) -

I5 Personal STPLN Project coordinator STPLN -

I6 Personal Managerial VA SYD Project leader’s supervisor -Head of Waste Department VA SYD Member of steering group - Head of Waste Department I7 Phone Southern district administration (Malmö Municipality) Project member -Director for Southern district administration Environmental Department (Malmö Municipality) - I8 Personal - - Cultural Department (Malmö Municipality) Leader of steering group

Second, a literature search was conducted on the databases of Malmö University Library and Google Scholar with the keywords of [ReTuren].

These documents help us have the overview about the project, its context, and the collaboration among organisations in the project. After investigating the documents’ contents for overview, the researchers eliminated documents that do not provide information about the conditions for establishment of the collaboration or the perspectives of core co-producers about it. Therefore, the researchers focused on analysing only the documents in which the interviewees are the author or one of the co-authors to explore their own perspectives about the establishment of penta helix cross-sector collaboration in ReTuren. Table 5 presents the list of collected documents

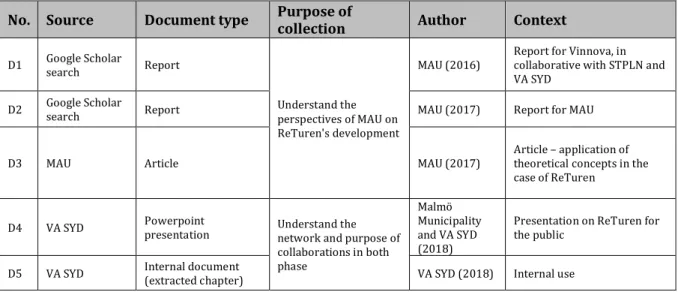

Table 5 - List of collected documents

No. Source Document type Purpose of collection Author Context

D1 Google Scholar search Report

Understand the perspectives of MAU on ReTuren's development

MAU (2016) Report for Vinnova, in collaborative with STPLN and VA SYD

D2 Google Scholar search Report MAU (2017) Report for MAU

D3 MAU Article MAU (2017) Article – application of theoretical concepts in the case of ReTuren

D4 VA SYD Powerpoint presentation Understand the network and purpose of collaborations in both phase Malmö Municipality and VA SYD (2018) Presentation on ReTuren for the public

D5 VA SYD Internal document (extracted chapter) VA SYD (2018) Internal use

3.4. Data analysis methods

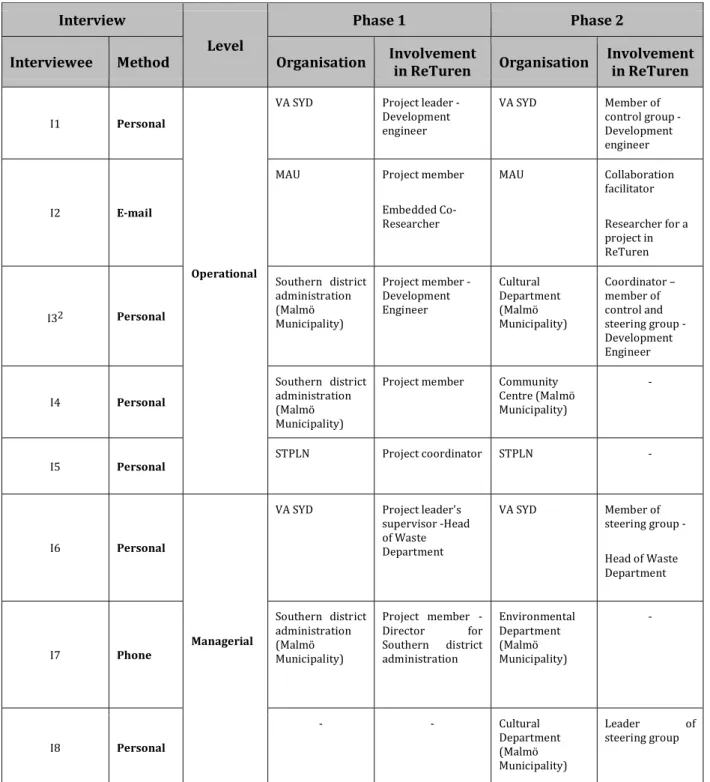

3.4.1. Interviews In order to analyse the qualitative data from the interviews, the method chosen is the content analysis technique (Silverman, 2014). The content analysis is the most adequate data analysis technique to use with the interviews given the type and deepness of the questions and the extent and content of answers received. In addition, the necessity to relate the sustainable behaviour living to the personal definition, opinion and motivation highly requests the establishment of data connections. The data analysis was divided into five main phases. It began by listening to the interview record, making notes of relevant information, and transcribing the interviews. From the transcripts, units of key words or citations related to conditions of penta helix cross-sector collaboration were categorised in different codes. The codes linked to each other by meanings were grouped into categories. Lastly, we defined themes based on the related categories with consideration of the adapted theoretical model of Bryson et al. (2015). This process was repeated for both phases of ReTuren project. Finally, it was possible to identify the linkage between these themes in both phases and compare and contrast them. Below is an example of the coding and analysis process (see Table 6).

Table 6 - Example of interview coding and analysis process

Citations Codes Categories Themes

"it is really boring and deprived environment" Local situation Local environment Environment "The people were upset and were protesting" Social crisis "we work from the waste hierarchy which is a strategy that has been taken by the EU that all the

Member Countries should work." Laws/Policies Institutional elements "We understood and [I1] understood that collaboration with others is very essential to succeed" (I6) Collaborative mindset Initial leadership Relationships "I think my job is to connect people that have some ideas and make it happen." "[I2] suggested that the methods of STPLN and the people that hang out here [STPLN] could be connected to ReTuren" Collaboration facilitators "there was a connection with VA SYD because they are in close contact with the environmental department of course" "long-term building of collaborations that sometimes bear fruit" Previous connections Existing relationships/ Infrastructuring "because they had a very good knowledge about what works in Lindängen, how you got people to come and what they liked" "you kind of use the infrastructure when it comes to, like, a network and people's knowledge that is already there." Skills/ Knowledge Availability of resources Resources "VA SYD decided that they didn't have the

competence to run a public service" Lack of competences Shortage of resources

"we don't have the common vision that actually says what we want to do and how we would want

it to look for a long term" Shared vision Shared vision/ Commoning

Strategy "discussed how makers’ activities with a focus on upcycling and repair could be a part of ReTuren" "we did like informal interviews now and then with people" "but we were quite open and trying to see "okay, how can ReTuren add value to this?" Dialogues Communication

"We don't have a formal agreement" Written agreement Agreement on the problem

3.4.2. Documents

The analysis of documents was also conducted using the same content analysis techniques as with interviews. However, it differs from interview analysis in that we also consider the context of the documents and original purpose of writers when interpreting the data from documents. This