Degree project in the major subject:

English and education

15 credits, advanced level

What’s their game?

- A study of teacher preparation for using

digital game-based teaching

Ett finger med i spelet:

En studie om lärares utbildning kring användandet av digital

spelbaserad undervisning

Michelle Stavroulaki

Jonas Lindskog

Master of arts/science in secondary education (300 hp) Examiner: Thanh Vi Son

Advanced level degree project in the major subject (15 hp) Supervisor: Shannon Sauro Date of opposition seminar 2019-06-04

Acknowledgements

For their valuable contributions to our degree project, we would like to thank all our interviewees for sharing their insights on our topic. We would also like to thank our

supervisor Shannon Sauro for her constructive guidance throughout our independent project and this project, as well as Bo Lundahl for his much appreciated advice.

Contributions

Hereby we state that all the work in this degree project has been divided equally throughout the process. This process consisted of the research stage and gathering of data, compiling the results and interpreting them, and of course the authoring of the thesis.

_________________________ _________________________ Michelle Stavroulaki Jonas Lindskog

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine perceptions regarding digital game-based teaching and the extent to which teachers of English in Sweden have been prepared to use this

approach. The basis for this study is the research on the effects of digital games for language learning and the perceived lack of the incorporation of these in teaching, creating a gap between student interests and teaching methods. Therefore, this study investigates the

approach of teacher educators who are involved in the design of teacher training programs, as well as the perceptions of in-service teachers at secondary and upper secondary schools in Sweden. In-depth interviews and an online questionnaire were used to gather relevant data. The findings show that all teacher educators who were interviewed found digital game-based teaching to be a relevant approach, but they noted that it is not incorporated in their teacher training courses to a sufficient extent. Additionally, the great majority of in-service teachers did not perceive that they received any education on how to use digital games or game elements in their teaching, while most of them found it to be relevant and had used it to some extent. These results would indicate that digital game-based teaching should be integrated to a greater extent in teacher training programs, and steps should be taken to ensure that current research on the topic reaches the teachers out in the field.

Key words: Digital game-based teaching, digital game-based learning, gamification, teacher

Table of contents

1. Introduction 1

2. Statement of purpose 3

2.1 Research questions 3

3. Literature review 4

3.1 The Swedish syllabi for English and digital games 4

3.2 Teaching theories as framework for DGBL 5

3.3 Digital games in educational contexts 7

3.4 Previous research on teacher perceptions and education 9

4. Method 12

4.1 Participants 12

4.2 Ethical considerations and GDPR 14

4.3 Instruments 15 4.3.1 Interviews 15 4.3.2 Questionnaire 16 4.4 Procedure 17 4.4.1 Data collection 17 4.4.2 Data analysis 17

5. Results and analysis 18

5.1 Perceptions on the role of digital tools in teaching 18 5.2 Digital games and their usefulness in education 19 5.2.1 Benefits with using digital games in education 20 5.2.2 Obstacles with using digital games in education 21 5.3 Current integration of digital games in teacher training 23

5.4 Perceptions of teacher preparation 23

5.5 Recommendations and action for the future 26

6. Discussion 29

6.1 Teacher educators’ perceptions 29

6.2 In-service teachers’ perceptions 30

6.3 Considerations and future recommendations 32

7. Conclusion 34

References 35

Interview guide 41

Questionnaire 42

1

1 Introduction

In the past years, research on gamification and its possible applications for language teaching has appeared. However, is this new knowledge reaching the schools and teachers? During our own teacher education the past five years, we have noticed that some forms of digital tools and modern teaching strategies are implemented, such as fanfiction and blog writing; however, there has been very little, if any, implementation of or information about digital games and the gamified classroom. At the same time in our practicum schools, we have noted a surge of interest in games among the student population, and an increase of the popularity and acceptance of digital games in the community in general. Within the school community though, we have not seen teachers approach this interest. The question is what has caused this gap between the students’ interest and teachers’ methods.

On the other hand, why might it be significant to consider gaming and gamification principles in teaching? Several studies have indicated multiple potential benefits for language learning; specifically, gaming can have positive results for vocabulary and potentially for oral fluency (Cardoso, Grimshaw & Waddington, 2015; Franciosi, 2017; Sundqvist & Wikström, 2015; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012; Zheng, Bischoff & Gilliland, 2015). Other major benefits have also been found for motivation and reducing anxiety, two factors that are seen as influential for all learning (Iaremenko, 2017; Reinders & Wattana, 2015; Vosburg, 2017). In order to be able to reap all these benefits, the teacher must be aware of the tool and have sufficient knowledge on how to implement it in the language classroom. Studies have shown that many teachers do not know how to use games or feel reticent and uncomfortable with applying gamification (Bourgonjon et al., 2013; Huizenga, ten Dam, Voogt & Admiraal, 2017; Koh, Kin, Wadhwa & Lim, 2012).

This seems to be the case in Sweden as well, where many teachers appear to not have

received any training on games and the use of gamification in teaching (Raptopoulou, 2015). Sundqvist and Olin-Scheller (2013) argue that this disparity between teacher knowledge and method and student interest causes students to become demotivated, since their interests are not being acknowledged. Furthermore, Sylvén (2013) showcases that Swedish students have among the highest exposure to extramural English in Europe, which has created a gap between the English the students meet outside school and what is being taught. Considering that the Swedish curriculum for upper secondary school encourages teachers to provide

2

students with opportunities to develop areas of their interest and the syllabus for English using language in different contexts with different aids and media, it follows that digital games could become a tool for teachers to reach students and meet their interests (Skolverket, 2011, 2018 ).

Based on the research within the field and the fact that teachers do not seem to feel competent in using games, it makes sense to investigate what might be the root of this phenomenon: teacher training programs. If the design of the current teacher programs is not up to date with the actual context the teachers will face at their workplace, this might leave teachers ill-equipped to meet students’ learning needs. This degree project aims to investigate this issue in order to get a better understanding of how Swedish teacher training programs might be able to incorporate game-based teaching methods in their programs and if this is a feasible expectation.

3

2 Statement of purpose

In this degree project, the focus is on digital game-based teaching and the extent to which English teachers are being prepared to use this approach. In order to investigate this, we have chosen to look at the issue from two angles: on one hand, the teacher training programs, and on the other, the in-service English teachers. To address the gap between the students’ interests and what they are being taught, we aim to further investigate how those responsible for designing and teaching courses in English teacher training programs perceive the role of game-based teaching in the English classroom. Accordingly, we aim to explore whether those involved in teacher training programs see a benefit to using gaming principles in language teaching as well as whether they see potential setbacks in using such an approach. Moreover, it is important to get a better understanding of how teachers out in the field have been

prepared with this method of teaching, and if they would be comfortable and proficient enough with this approach. Our main focus lies with English teachers at secondary and upper secondary schools in Sweden, and the respective teacher training programs at Swedish universities. These two perspectives will be compared to see if the teacher educators’ perceptions agree with the in-service English teachers’ perceptions, something which might provide insight into the overall question of how digital game-based teaching is approached within English teaching in Sweden and if there is any need for change.

2.1 Research questions

1. How is digital game-based teaching approached by the faculty that designs the English teacher training programs at universities in Sweden?

2. To what extent do English teachers perceive that their education and in-service training equipped them with sufficient knowledge for using digital game-based teaching?

4

3 Literature review

Before diving into the theoretical framework of this study, it is essential to

explore some of the key terms used. The first term we use is digital games. This is defined by Clark, Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth (2016) as a “digital experience in which the

participants (a) strive to achieve a set of fictive goals within the constraints of a set of rules that are enforced by the software, (b) receive feedback toward the completion of these goals [...], and (c) are intended to find some recreational value” (p. 87). In studies such as the one made by Iaremenko (2017), gamification is defined as the incorporation of game elements in non-game contexts. However, the main concept we use is digital game-based teaching, a term derived from the more established digital based learning (DGBL) and digital game-enhanced learning, which refer to the incorporation of digital games and game environments that either have a pedagogical purpose or a commercial purpose into educational contexts, in this case with a focus on language learning (Reinhardt & Sykes, 2012). We have chosen to use the term digital game-based teaching instead of DGBL in order to accentuate the focus on teachers and teachers’ practices rather than focusing on the learning process itself.

3.1 The Swedish syllabi for English and digital games

The use of digital games in the classroom is discussed all over the world since there seem to be many benefits to using this method when it comes to language learning, but does this teaching method comply with the policy documents for Swedish schools? On orders by the government, the curriculum for the Swedish upper secondary school was revised in 2018 in order to make it more clear that schools in Sweden have to work more with students’ digital skills in order to help them better understand the digitized world (Skolverket, 2018). In addition to the revised curriculum, the syllabi for the English subject at secondary and upper secondary level are also designed to incorporate digital aspects in the classroom in order to stay up to date with modern society, which would include digital games. In the comment material for the English subject at secondary school, it is stated that the syllabus is worded in a specific way so that it does not exclude the ever-growing digital world where English is used on a daily basis, and it also promotes that teachers work with students’ interests since research indicates that students learn a language more effectively if they use it in contexts that stimulate the students (Skolverket, 2017, p. 8, 10). This demonstrates the flexibility and

5

adaptability of the syllabus for the English subject, which make it possible for teachers to use digital tools to help students develop their language skills.

However, the syllabus at the upper secondary level is not as explicit when it comes to approaching students’ interests and digital tools, but the secondary and upper secondary English courses are supposed to be linked to one-another and a clear progression should be present (Skolverket, 2017, p. 5). Even though the approach to digital tools and student interests is not as explicitly mentioned, it is still very open for interpretation and connections to these approaches and the use of digital games could be made. The aim of the English courses at the upper secondary level is to help the students “develop knowledge of language and the surrounding world so that they have the ability, desire and confidence to use English” and “through the use of language in functional and meaningful contexts, to develop all-round communicative skills” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 1). Digital games have the capability to boost the students’ confidence if used in a correct manner and will allow them to practice a variety of language skills in many different settings; gaming would hence be in compliance with the syllabus since it promotes some of the key aspects of the aim of the subject. It is also written in the core content of English 5 that the course is supposed to cover content in different forms of fiction (Skolverket, 2011, p. 3), and this is a category that many games are part of since most are based on a fictional plot which the students can get immersed in and also interact with. Used appropriately, digital games in an educational setting could find support in the syllabus considering that games can help develop communicative skills, they increase students’ confidence to use English in various settings and they are also a form of fiction, which is supposed to be covered in the course. However, teachers need to know how to use these games in the classroom in order to make them relevant for language learning. This will be further discussed below.

3.2 Teaching theories as framework for DGBL

For a teacher to apply a new tool in their practice, they need to know that it will have positive effects for the type of learning they are looking to achieve in their students. This means that the tool must be researched, and its principles need to comply with theories about learning. This section will focus on the theories for language learning, specifically second language acquisition (SLA) theory, to pinpoint if game-based language teaching draws from theoretical frameworks.

6

One of the most frequently used frameworks in modern language teaching is communicative language teaching (CLT), from which the Swedish curriculum draws greatly as can be seen in the main goal of English teaching discussed above, promoting students’ all-round

communicative skills (Skolverket, 2011, p. 1). This can clearly be seen to correspond with CLT’s focus on the real-world use of language in preparation for interactions outside the classroom (Nunan, 1988, p. 25). Within CLT, communication is often seen to consist of input and output. Krashen (1985) argues that learners develop language skills through exposure to forms of the target language more advanced than their own level. Beyond input, teaching should also strive towards students’ engagement in meaningful tasks, interaction and negotiation of meaning, as well as practice of linguistic elements in order to challenge their communicative skills (Nunan, 2004). How then does game-based teaching fit into this context?

A CLT teaching approach has the potential to prepare students for real-world interactions by using digital games. Gee (2007) has long advocated the learning potential of games, making the argument that cognitive research supports their use in education, since they are based on effective learning principles which promote deep learning (p. 28). Different types of games can be beneficial for different types of learning, and a large variety of games in English exists that exposes the player to both written and spoken English throughout the gaming session. The positive and negative effects of gaming on learning will be analyzed in greater detail in the next section, but one of the main benefits has been shown to be for motivation, a key ingredient for language learning, including and perhaps especially for vocabulary learning. According to Ushioda (2012), intrinsic motivation, i.e. doing something for its own pleasure is considered the most optimal form of motivation since it results in high-quality learning, and Dörnyei (2007) asserts that motivation “has a very important role in determining success or failure in any learning situation” (p. 2). A teacher who wants to use a game-based

approach can therefore claim that their choice finds support in this theoretical framework, as well as in the curriculum; however, the question remains as to how this approach can be applied in practice.

A game-based teaching approach can either use digital games directly as tools, or it can integrate the basic principles that make the games effective for learning. This could be done with the help of blended teaching methods, which combine face-to-face and online learning

7

environments (Stacey & Gerbic, 2009). These are beneficial since they provide students with varied exposure to the target language, which helps them practice their language skills in authentic environments, while simultaneously allowing the teacher to provide feedback and scaffolding (Reinders, 2012). Using digital games can be successful with the teacher’s guidance and scaffolding, but the teacher can also choose to use applications that integrate game principles to support learning. A popular such tool that many teachers use without realizing they are gamifying their teaching is Kahoot!. Iaremenko (2017) investigated the educational game Kahoot! and discovered that the competitive multiplayer game activated students’ intrinsic motivation and improved their language learning. What is left is for the teacher to strike a balance in the use of traditional and game-based teaching, although this might be difficult without knowledge or experience in this approach.

3.3 Digital games in educational contexts

The use of digital games in the English classroom can seem relatively unorthodox, since it is not a traditional tool in a school context and is mainly perceived as a leisure activity with no educational purpose, unless it is a game that is designed specifically for teaching. However, if digital games are used properly, language learning could be achieved by strengthening

various language skills. As mentioned earlier, gaming has a motivational quality, but when it comes to language learning it also shows positive results for vocabulary learning, and it can potentially better the students’ oral fluency (Cardoso et al., 2015; Franciosi, 2017; Sundqvist & Wikström, 2015; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012; Zheng et al., 2015). As an example, Zheng et al. (2015) suggest that an expanded vocabulary could be achieved through online gaming, since it can create connections with native speakers of English who might use words that are new to the students. Reinders and Wattana (2015) point out that vocabulary learning through gaming would be even greater if the students were to get guidance from their teachers and feedback from their peers; proper scaffolding provided by the teacher could result in lifelong learning, since such a framework could be used by the students when they play games at home as well. The use of digital games in the classroom could hence bridge the gap between the students’ interests and what they do in school, and this would help them develop their language skills even further both in class and at home.

Moreover, studies show that gaming as an educational activity can reduce anxiety levels amongst students, and they also become more confident when expressing themselves in the

8

target language (Cardoso et al., 2015; Reinders & Wattana, 2015). The reduced levels of anxiety and the increased confidence create a more relaxed and enjoyable learning

environment, and the students will tend to communicate more freely with each other in the classroom, hence creating a learning context which the students will benefit from when it comes to language learning (Cardoso et al., 2015). However, these learning outcomes differ depending on what type of game the students engage with. Sundqvist (2019) found that multiplayer and MMOs (Massively Multiplayer Online) games are more likely to yield benefits for English vocabulary compared to single-player games. Another crucial factor is the time spent playing; the time played is seen as a predictor for L2 vocabulary, and as Sundqvist (2019) concludes: “Playing COTS [Commercial off-the-shelf] games matters for L2 learner vocabulary” (p. 87). It is evident that research supports game-based teaching, but it is important for the teachers who attempt to use this method to have sufficient knowledge about how games are best utilized in the classroom through scaffolding and clear goals, as well as what type of game to use for different kinds of language exposure.

Even though most research in the field suggests that gaming has some clear benefits when it comes to language learning, there are still some negative aspects to consider when using digital games as an educational tool. Some studies show that gender can sometimes affect the learning outcomes of gaming; for instance, boys seem to outperform girls when it comes to vocabulary development through gaming (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). However, such

differences could be explained by the fact that boys and girls tend to appreciate different sorts of games that promote different learning outcomes; boys seem to prefer massively

multiplayer online role playing games which is favorable for vocabulary learning in comparison to single-player games which is the preferred game type by girls (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012).

Another potentially problematic aspect of gaming is the fact that there is not enough research that proves that there are any long-term learning effects to gaming. Not many researchers have looked at the long-term effects of in-class gaming and Iaremenko (2017) questions whether in-class gaming is good for long-term learning at all. Recently though, Sundqvist (2019) determined that time seems to be the most significant factor, meaning that prolonged periods of gaming increase the probabilities of vocabulary learning; it should, however, be noted that this looked at gaming as an extramural activity, and not in the classroom. Considering that the students only get to play a limited time in school, they might not get

9

enough exposure to English in order for it to be fully comprehended and remembered for a long duration of time. With this in mind, it is all the more important that the teacher is aware of how to use this tool in order to ensure that language learning can occur, and the teacher must also have sufficient knowledge about digital games in order to provide the students with proper scaffolding.

3.4 Previous research on teacher perceptions and education

After looking at some reasons why teachers might or might not want to use digital games in their teaching, it is necessary to explore what teachers seem to believe about game-based teaching. Several studies explore teacher perceptions about digital games and their use for educational purposes, and the overall image that appears is that teachers can see benefits from learning through digital games, but they do not feel comfortable using games in their own practices (Bourgonjon et al., 2013; Huizenga, et al., 2017; Koh et al., 2012). One important observation is made by Allsop, Yildirim and Screpanti (2013), in their comparative study on teacher beliefs in Turkey, Italy and the UK; they found that the context varies significantly depending on the country, not only regarding teachers’ interest in and experience with digital games, but also whether game-based teaching finds support in the curriculum. They also found a gap between current research, policies and what is reaching the schools, which has resulted in teacher training in new technologies not being treated as a priority, despite an investment in digitalization, leaving teachers alone to deal with how to apply these tools that they are expected to use (Allsop et al., 2013). The overall research seems to then point to teachers being aware of these possibilities, but not receiving the tools that would allow them to implement them in their classrooms.Research highlights the significant role of teacher training for adequately preparing future teachers regardless of subject matter. Teachers who are not adequately prepared may not be able to fulfill their expected roles in the classroom, and if preservice education does not teach them that which they in turn are expected to teach, the education system will have failed in its purpose (Newton, 2018). It is not enough to assume that people coming into the teacher training programs are digital natives, because even teachers who are digital natives are often unequipped with experience and knowledge for how to use technology in the classroom (Lei, 2009).

10

Beyond the lack of experience and training, there are other obstacles to implementing game-based teaching. Egenfeldt-Nielsen’s (2011) survey about game-game-based learning with

participants from Denmark, Norway, Finland, Portugal, and the US showed that practical issues dealing with the technological aspects along with the high cost of games are seen as the greatest barriers, followed by teachers’ lack of knowledge, syllabus and time restrictions. This is consistent with obstacles seen in older studies such as Baek (2008), that pointed to curriculum inflexibility, fixed class schedules, limited budgets, lack of supporting materials, and negative effects of gaming as main obstacles, as well as more recent studies such as Allsop et al. (2013), that found technical issues, teachers’ lack of training, and curriculum restraints to be the most common barriers to using games. Additional issues were found when applying game-based teaching through COTS games in Sweden. Berg Marklund (2015) showcases that although COTS games are seen as more efficient for learning, this can bring other difficulties when applying them, such as differences between student gaming

experiences in heterogeneous classrooms, managing student expectations, framing the activity correctly, and promoting collaboration that combines work with subject matter and gaming literacy. These issues can be difficult to manage for an experienced teacher, but how can teachers be expected to implement game-based teaching successfully with little to no training?

Of course, it is not impossible to apply game-based teaching in the classroom, particularly with some experience. Huizenga et al. (2017) interviewed secondary education teachers who used digital games in their classrooms and found that they perceived it to be an efficient tool for learning, with benefits for student engagement, motivation, as well as subject matter skills. Interestingly though, this study did not include any language teachers, as none could be found who had recently used games in their classroom. Since it is a complex matter to

incorporate games in the classroom, this accentuates the need for teacher training all the more.

What is then necessary for teacher training to adequately prepare teachers? Something that might pose a problem to any changes is that there can be a discrepancy between how both teacher educators and teacher students perceive the education. Wilhelmsen (2009)

interestingly found that almost 70 % of teacher educators in teaching programs in Norway believed their students were receiving digital competence through the program; however, less than half of the pre-service teacher students felt that their education had prepared them for

11

using technology in the classroom (as cited in Instefjord & Munthe, 2016). So what would be required to actually equip future teachers? An (2018) showed that even one online

professional development course on digital game-based learning (DGBL) significantly changed the participating teachers’ perceptions, attitudes and self-efficacy. Most importantly, the teachers, not only understood the benefits of DGBL, but also stated that they felt more comfortable using digital games in the classroom after completing the course (An, 2018). This study suggests that teacher education has the potential for equipping teachers with the tools to implement game-based teaching, as well as other digital tools, and that as much as one course might be adequate for this preparation.

12

4 Method

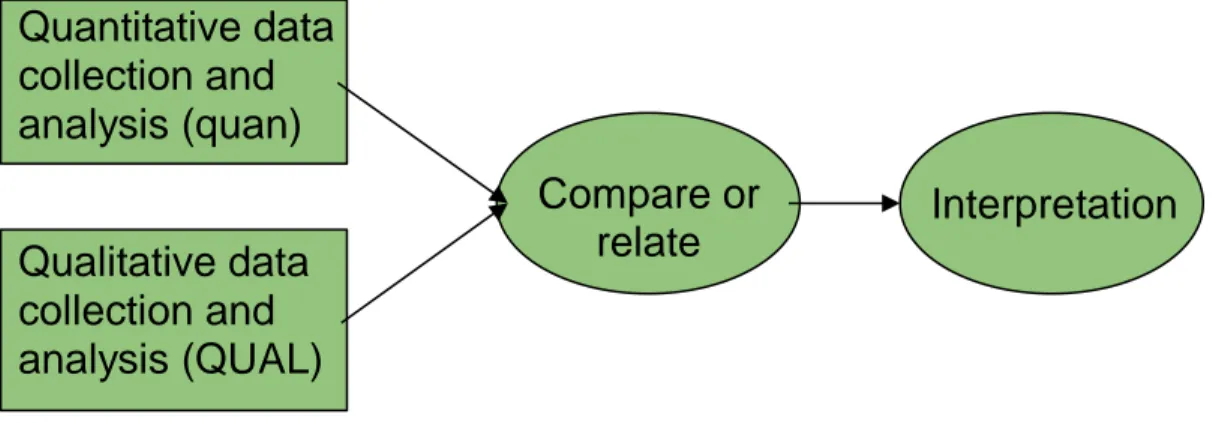

Although the methodology of this study combines qualitative and quantitative aspects, including in-depth interviews and an online-based questionnaire, the analysis adopts a qualitative approach. The research process can be symbolized as qualitative and quantitative (QUAL + quan; Dörnyei, 2007). In order to answer our two research questions, we have chosen a convergent parallel mixed methods design. This means that we have collected both quantitative and qualitative data approximately at the same time and then converged the data to generate a comprehensive analysis (Creswell, 2014, p. 15) (see figure 1). The choice of this method was influenced by our desire to provide an overview of the research problem through investigating two perspectives: in-service teachers of English and teacher educators. To reach the first target group, a quantitative method, namely a questionnaire, was deemed most relevant in order to secure a larger sample. To reach the second target group, it was deemed most relevant to use a qualitative method, interviews, to gain insight into the perceptions and approaches of key staff at teacher training programs.

Figure 1. Flowchart of data collection and analysis according to convergent parallel mixed

methods design. Adapted from Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed

methods approaches (p. 15) by J. W. Creswell, 2014, Los Angeles, Calif.: SAGE.

4.1 Participants

In order to address both research questions, two target groups were contacted. The total number of participants amounted to 55 people (N=55). To gather relevant data for the first research question, the faculties of different English teacher training programs at various

Quantitative data

collection and

analysis (quan)

Qualitative data

collection and

analysis (QUAL)

Compare or

relate

Interpretation

13

universities in Sweden were sought out. The selection of people was initially based on the participation at the Swedish Society for the Study of English (SWESSE) conference at Malmö University in the spring of 2019. Due to a lack of availability, some additional members of English faculties at Swedish universities were contacted. In total, ten people were contacted and five chose to participate in our project (n1=5). The main criteria for the

participants to be included in the interviews were that they work at a university in Sweden and are involved in the design and implementation of the English teacher training program. This ensured that our selected group of interviewees were qualified to answer the questions concerning the design of the English teacher programs.

Regarding the participants who were interviewed, they were from different universities in different parts of Sweden. The first interviewee, who will be referred to as Jack, is a coordinator within a teacher training program with an interest in the use of digital tools in teaching, who has also designed a course on the subject which is given to teacher students. His background is in English language studies and linguistics, and he is also a certified teacher. The second interviewee, Rory, is also a coordinator for the English department at his university, who specializes in teacher training, and he has a background as an upper

secondary teacher of French and English. The third interviewee, Donna, is a professor of Language Education with a research focus in English linguistics and a special interest in extramural English and CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning). She is not a teacher herself but has taught to some extent at upper secondary schools, universities and some in-service courses for teachers. The fourth interviewee, Martha, started off as an upper secondary teacher of Swedish and English, has a specialization in English literature and a research focus on multimodal texts, and is currently working as a course convenor for the teacher training program. The fifth interviewee, Ian, is amongst other things a coordinator for the teacher training program at his university, with a focus on grammar, linguistics and academic writing. All the interviewees, barring Donna, are directly involved in the design of teacher training courses. Donna is still relevant since she has taught student teachers as well as in-service teachers, and she has done significant research within our focus area.

For the second research question, secondary and upper secondary English teachers were asked to answer the questionnaire anonymously. The total number of teachers who answered the questionnaire was 50 (n2=50). They were found through the platform Facebook where

14

for them to share information. The groups that have been used for the distribution of the questionnaire are: Engelska för Gymnasielärare that consists of more than 900 members, the group Engelska i åk 6-9 consisting of 6 430 members, and Språklärarnas Riksförbund with about 3 770 members. These are closed groups, hence increasing the likeliness that the

members have some sort of experience as an English teacher. While the first two groups were chosen to ensure replies from both secondary and upper secondary school teachers, the last group might have some overlap in members, since it involves all language teachers; this can unfortunately not be controlled by us, but we trust that they only fill out the questionnaire once. It has also been considered that not all teachers use social media platforms such as

Facebook which is why English teachers at partner schools were contacted through E-mail

and asked to further distribute the questionnaire within their own networks. This made it possible to reach more teachers and ensure that the participation group is diverse. The final sample group was geographically dispersed, as the participants received their teacher training at eleven different universities and currently teach at fifteen different municipalities in

Sweden. However, it should be noted that not all the participants replied to this question. The majority of teachers who replied to the questionnaire (48 %) were experienced with more than ten years out in the field; an additional 26 % of the teachers had taught for five to ten years. The remaining 26 % have worked as teachers for one to five years. It is also worth mentioning that three of the participants were primary school teachers, but their answers were not outliers and followed the general trends.

4.2 Ethical considerations and GDPR

In qualitative research, it is important to ensure the participants are aware of what is being asked of them and that they can withdraw consent at any time (Cassell, 1982). For this study, the guidelines of Vetenskapsrådet (2002) were followed when interviewing the participants, namely: the information requirement, that the interviewee is aware of their part in

the study and the conditions that apply in order to obtain informed consent; the consent requirement, that the participant is willing to comply with the conditions of the study and is aware that they can stop or interrupt the interview at any time without pressure or influence from the interviewer; the confidentiality requirement, that all information is stored and handled in a way that ensures anonymity; the usage requirement, that the information obtained can only be used for the purposes of the specific study. In addition, the consent forms were stored by the supervisor of the degree project and destroyed after its completion.

15

Regarding the online-based questionnaire, the anonymity ensures none of the respondents’ personal information was collected, and since it is an attitudinal survey, there is no personal data of any kind involved. Beyond this, the respondents were informed of the purpose of the questionnaire and its anonymity before completing it, as well as how the data would be handled. To further ensure that the conditions of GDPR were followed, we adhered strictly to the guidelines and interpretation provided by Malmö University. This meant that we were careful to obtain consent in an appropriate way and using the correct templates, and that we took care to ensure anonymity and the safety of all information by storing all data on Malmö University’s own server.

When conducting surveys, it is necessary to consider the role of the interviewer and survey designer. Since human bias is difficult to avoid, answers elicited in surveys may be

influenced by the phrasing of the questions, leading to some results being artifacts from the elicitation method (Nunan, 1992, p. 139). In consideration of this, the questionnaire used for this survey did not involve any interaction or intrusion by the researchers, while the questions constructed both for the questionnaire and the interviews were created to be as neutral as possible to avoid leading or influencing the respondents. Of course, in the interviews that were conducted face to face, there may have been some asymmetry in the relationship between interviewer and interviewee (Nunan, 1992, p. 150).

4.3 Instruments

This study has a mainly qualitative approach with some quantitative aspects. As mentioned, the methods used were in-depth interviews and an online-based questionnaire. In addition, some digital tools were used for distributing and analyzing the survey and yielded data. These were mainly Sunet Survey, which was used to create and distribute the questionnaire,

Facebook, which was used to find participants and distribute the questionnaires, and Malmö

University’s server to store the data securely. The following sections will present in more detail how the methods were applied and the data analyzed.

4.3.1 Interviews

The five interviews were conducted by the both of us and followed a semi-structured interview model, since this would allow us to control the interview, while offering a great

16

deal of flexibility and yielding rich information optimal for a qualitative study (Nunan, 1992, p. 149, 150). In addition, this format means that the interviews were guided by a series of themes with suggested open-ended questions and follow-up questions, which allow the interviewers to judge the order of questions and the direction of the interview, while

encouraging the interviewee to express themselves more freely, promoting in-depth answers (Kvale, 2009, p. 130). The interviews spanned between thirty minutes and one hour, and they were recorded and stored locally before being uploaded to Malmo University’s server. Prior the interviews, the participants were informed about the ethical considerations, and the information obtained from the interviews was analyzed according to the predetermined themes and transcribed in part.

4.3.2 Questionnaire

A series of closed-ended questions was designed in order to gather information about English teachers’ opinions about game-based teaching at secondary and upper secondary schools and to see whether they feel equipped enough to use such tools in their own teaching. The

questions focused mainly on attitudinal aspects, but there were some factual questions as well so that a better understanding of the teachers’ backgrounds can be achieved, particularly since the questionnaire is anonymous, and some behavioral questions were included as well to better understand how the teachers actually use digital games in their teaching. As previously mentioned, the questions were closed-ended and included both multiple-choice items that yielded diverse answers and true or false questions that generated more accurate data (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 102, 106). Additionally, a comment field was added to some of the

questions to allow teachers to share some of their thoughts on the specific topic, thus yielding some supplementary qualitative answers. The questionnaire was constructed using the tool Sunet Surveys, and before distribution it was piloted by some English teacher students in their final year of the program; to pilot a questionnaire in such a way is to ensure that the questions are relevant, answerable and free from typos (Gillham, 2007, p. 42, 43). The pilot of the questionnaire resulted in minor changes regarding grammar and spelling and a few questions were reformulated in order to yield more relevant answers. A total of 50 responses were received on the questionnaire; however, the participants did not answer all the questions resulting in a varying response frequency on the different questions.

17

4.4 Procedure

4.4.1 Data collection

The interviews were held shortly after contact had been made through E-mail, and they were carried out using the tool Zoom, which allowed us to record both audio and video that was immediately saved on Malmö University’s servers when the interviews were finished. The participants in the interviews were informed of the ethical considerations before the

interviews commenced, and the duration of these interviews varied between 40 to 60 minutes. They were later on partially transcribed through a clean verbatim method in order to make the results more intelligible. Simultaneously, the questionnaire was made available on the Sunet Survey website, and it became publicly known to English teachers through Facebook posts in three different groups with a reminder when one week had passed.

4.4.2 Data analysis

After the data was collected, we proceeded with partially transcribing and coding the interviews according to predetermined categories, as well as new themes that had emerged, and analyzing the statistics from the questionnaire. The interviews were analyzed through qualitative content analysis, taking the predetermined categories as a starting point and searching for new emerging patterns (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This resulted in a

combination of the predetermined and new categories for the interpretation of our survey results. In parallel, we used descriptive statistics to determine the answer frequencies and the qualitative comments from the questionnaire to interpret these. Following this, we looked at the qualitative analysis results in relation to the quantitative and partially qualitative answers from the questionnaire. This resulted in the final interpretation of our results, which is presented below.

18

5 Results and analysis

5.1 Perceptions on the role of digital tools in teaching

Before examining the perceptions that were found to exist regarding digital games, it might be relevant to briefly consider the overall views on digital tools and why new tools are important to contemplate from a teaching perspective. There seems to be a consensus among the interviewees regarding what the role of digital tools in educational contexts should be, and that is to support the main content of the lesson. Jack emphasized more than once during the interview that digital tools should be a supplement to the main teaching, but he also made the point that “we need to prepare our pupils for the digital world that they’re going to be working in, so this is where these tools come in”, indicating that digital tools should be a part of modern teaching practices. Similarly, Rory and Martha put the needs of the students first and digital tools as a secondary concern. Rory stated: “My standpoint is always, you need to start with the pupils and their needs, and then we see what we can use technology for” which mirrors Martha’s comment on how digital tools should be used: “I should use digital tools when I find it helpful, and not all the time”. Rory also stated that he refuses to use tools just for the sake of it; they must the needs of the students. Donna, in contrast, pointed out that she believes that digital tools should be implemented more in every-day teaching, claiming that they offer immense opportunities for the students and make the subject at hand more interesting.

On the flip side of this, the teacher educators note something problematic that seems to be occurring in the educational arena. As Martha continues: “There is a pressure to use digital tools as much as possible, and so…then the tool comes first. And then you figure out what to do with it, instead of considering what is the best tool for what to teach”. Rory continues on the same track: “Our municipality here now, for example, they force teachers to use a digital tool for assessment that, they have never asked for it, nobody has asked for it. Then, of course, the quality becomes very low”. This seems to be reflected in a comment by an in-service teacher when discussing the relevance of digital games:

Methods are only interesting if they help with the goals. There is a bit too much focus on things being good per se if they are digital, which I don't agree with. I also think

19

that schools and municipalities are far too uncritical of the economic interests involved when it comes to digitalisation. I am interested with a critical mind.

This showcases the importance of knowing how to use a tool and not feeling required to use teaching methods or tools that are unfamiliar; this is a factor that needs to be considered greatly when discussing the incorporation of new elements into teaching.

5.2 Digital games and their usefulness in education

After briefly examining the perceptions around digital tools, this section will focus on the perceptions of digital games and their use in education that appeared in our survey. To begin with, none of our interviewees claimed to be a gamer or an expert on our topic; however, most of them were familiar with the concept of DGBL, and one of them, Donna, had

conducted research within the area of gaming for language learning. Even though they were not all as familiar with the area, they could imagine using digital games themselves for certain purposes. Rory, who has been involved with the process of writing the English syllabus, argues that the use of digital games in English teaching in Sweden is justifiable according to the steering documents: “If we call these tools media, yes, they are there [in the syllabus]. If we talk about the way it describes text and literature, we can see these tools as literature or texts as well, so you can justify it from many perspectives”.

Furthermore, most of the interviewees agreed that there is a discrepancy between how teachers and teacher educators view games in comparison to other digital tools; often digital games are seen as something separate, and many might not consider it to be a digital tool for teaching. Despite this, all the interviewees agreed that digital games are relevant for teachers and can be used for educational purposes. As Martha puts it: “if we look at what young people use in their spare time, computer games, tv series and films are the three big

categories… I think that will only increase. I think teachers of English need to be prepared”. This coincides with the view of most in-service English teachers who answered the

questionnaire, 64 % of which agreed that digital games are relevant for teaching and only 4 % did not agree with this, whereas 32 % claimed not to know.

One of the main observations by the interviewees, which is worth mentioning, was that a key component to using digital games is to have a clear purpose and knowledge of how to do so in a beneficial way. Rory describes his process:

20

I always ask students to answer the questions what, how, why, so what, and now what. If you use it, why? And then what do you do with it? So that it’s not just a, you know, pastime activity at the end of class, but that it becomes a part of the learning process.

Martha presents an agreeing view: “You need to learn about it, so you know, why do you teach it, why and then how…That is the key”. It is then evident that, as with all teaching approaches, reflection and evaluation are important to establish that the way it is being used is sound.

5.2.1 Benefits with using digital games in education

When it comes to the reasons the teacher educators believe that digital games can be used for educational purposes, there are several noteworthy points. Firstly, some benefits to using digital games in the classroom were the motivational quality of games and their potential of creating interest with the students; Jack states:

The benefits really are in terms of increasing motivation… you can reach the type of pupil that perhaps would have been very turned off with conventional language teaching, so I think you do kind of reach out to people who maybe find some aspects of learning a language to be a bit more difficult.

Secondly, Donna, Jack and Martha all point out the potential benefits for vocabulary learning. Donna states:

As me and colleagues have found, vocabulary is of course great, digital games are great for vocabulary learning, there is no question about that… if we go a little step above the level of vocabulary, we have word chunks, phrases, idiomatic expressions and so on. There is so much you can work with.

Other benefits that are suggested by the teacher educators are for pragmatic competence, logical thinking, and creativity in language learning. Martha notes that the interactive aspect of games can be very positive and particularly useful when teaching about literature and story-telling. Rory also notes that digital games could be combined with assessment and presentation tools, for example recording the process and evaluating it, but it can also help students exploit the creative element that exists in both games and languages:

Building up creativity by using games—I can see the connection there between the two. That you can build your own worlds, you can compete, you can construct, and

21

you can at the same time build the same things linguistically next to it, explaining what you are doing, building new sentences.

Finally, Ian notes that “what happens in games is you get rewards, you get this instant reward… this works, that is how the human mind works. We want this and it would work if you did it right”.

5.2.2 Obstacles with using digital games in education

Despite all the teacher educators agreeing that there are multiple benefits to using digital games for language learning, they also present some possible obstacles. Something that might have been a problem earlier is the access to technology; however, Jack states that this is not a problem anymore, as “you really have to have a good IT infrastructure in the school, wi-fi and things like that, a fast connection… that used to be the obstacle, now I don’t think that’s really a major problem”. In contrast to this, however, some of the in-service teachers

commented that their schools do not have the technological framework needed. One of them states that “my students do not have the equipment”, and another teacher who had tried to use games wrote that “the school's technology wasn't compatible with what I wanted to use”.

On the other hand, the thing that is presented as a main problem is the lack of time and resources. Jack again, in particular, states that “there is no way that you can, no school or council, municipality, kommun has the money to keep training you in these tools [sic]”. Several of the interviewees also agree that both for teachers in the field and teacher educators there is so much to prioritize that it is very difficult to add more things to that. This

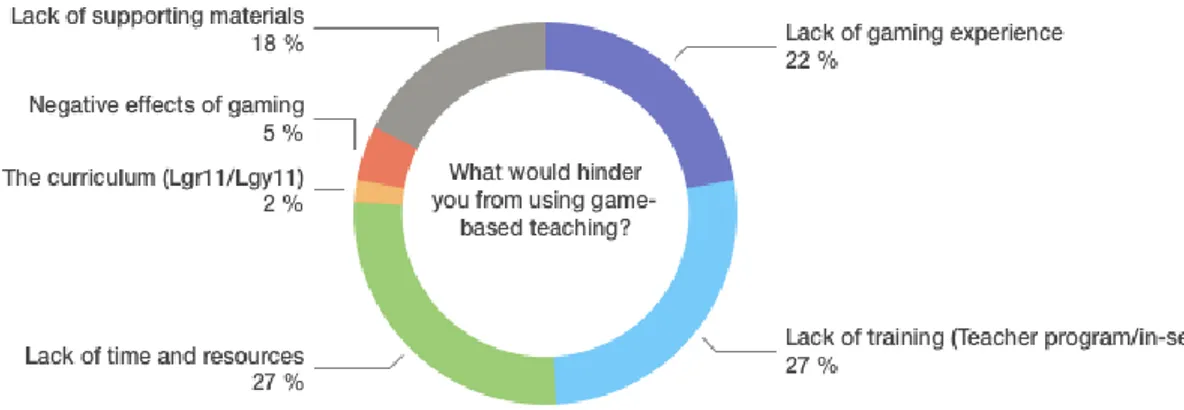

corresponds to what the in-service teachers have answered in the questionnaire, as they identified the lack of time and resources to be the main hindrance to using digital games, along with the lack of training on the subject (see fig. 2). As one teacher put it:

Before I let my students use games I want to make sure that the game is suitable for my subject and that the purpose of using it fits in the curriculum. I also need time to explore it carefully, so I don’t waste time. This takes time, but when it’s done it really is an excellent tool in the classroom.

The problem with lack of training is unanimously brought up by the interviewees as well, and as Donna points out, “there is a resistance towards digital games because most teachers are novices at that as compared to their students who are experts… many teachers who feel more

22

or less scared of introducing something into the classroom that they don’t know basically anything about”.

Figure 2. Hindering factors for in-service teachers for using game-based teaching.

Other obstacles that arise concern the games themselves. Martha points out that many games are expensive and in order to be allowed to use them you need a license to avoid copyright infringement. On the other hand, she notes that using games that exist for free online often requires students to have a login, something which is made complicated by the GDPR regulations for minors. Something else that might be an issue is the willingness of both in-service teachers and teacher educators to incorporate these modern tools into their teaching. Ian states that “some of our instructors aren’t too digital. It is part of their image that they are against these things; they do as little as possible when it comes to computers and digital tools. So they would not, they would basically refuse”. And as Rory adds, it is important to allow differences of opinion, and that teachers use tools that they are familiar and comfortable with. The teacher educators do suggest solutions to this problem, which will be covered in later sections; however, Donna pinpoints something that is perhaps more problematic and

complex. In studies that have found benefits for language learning through the use of games, this has been done in conditions where the students choose to play games on their free time and learning comes as a by-product. Therefore, she observes that it might not be the case that students find the same appeal if the teacher tries do this in class. Her final comment is that:

We need to be kind of careful when introducing digital games, so that we do not, how shall I put it, give the impression that we are trying to take their free time interests and make them into school subjects because if we do that they might lose interest in them altogether.

23

5.3 Current integration of digital games in teacher training

The integration of digital games in teacher training programs appears to vary from one university to another, both when it comes to how much it is used and also how it is being included in the teaching. This study only features teacher educators from universities in five different Swedish cities, so these results do not necessarily reflect what goes on in all the teacher training programs. However, three out of the five teacher educators stated that DGBL is not covered in their programs at all and one that it is used to a very limited extent by few teachers. The one teacher educator who uses digital games at his university is Jack. He works with digital tools and games in his teaching and introduces students to literature about CALL (Computer-assisted Language Learning) but puts the main focus on the practical parts. His teacher students get to play games on their mobile phones or other devices in order to better understand how such games can be utilized in schools, so that pupils can practice vocabulary or other language skills, and in some cases they also get to design their own games for educational purposes. Similarly, Rory does not find the use of digital games in teaching as something odd. He claims that games have always been part of teaching and that teachers today basically do the same thing as teachers thirty years ago, with the only difference being that the games have been digitized and the pupils can play the games on their mobile phones. Despite this, digital games do not seem present in teacher training. This will be covered in greater detail in the next section.5.4 Perceptions of teacher preparation

None of the interviewed teacher educators thought that students enrolled in a teacher training program receive enough information about the use of digital games in educational contexts in order to use them for pedagogical purposes. Except Jack who tries to incorporate some game elements in his course, all the teacher educators’ statements on teacher preparation echo Ian’s:

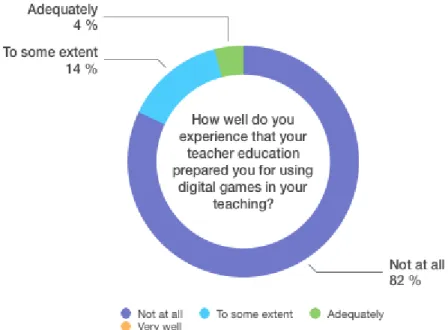

No, not at all. So they would have to get the tools for that elsewhere…We don’t provide them with that in our teacher education. I’m pretty sure that it is not done in any of the courses that I am not totally familiar with either, so no I don’t think so. This belief corresponds with the perception of how well-prepared teachers out in the field feel when it comes to digital game-based teaching. 4 % of all the teachers who responded to the questionnaire think that they have gotten adequate information about this teaching method during their teacher education and 14 % consider that they have gotten information on this

24

topic to some extent, while the majority of 82 % do not feel that they have gotten any information at all (see fig. 3), and some of the teachers also commented that there was a certain reluctance towards using digital games when they received their teacher education: “Talked about the existence of it, but generally the teachers were skeptical when I brought it up”. However, it must be mentioned that gaming as a teaching tool is a relatively new phenomenon, and the majority of the teachers who have participated in this study have already been teachers for more than five years, which would mean that they might have undergone their education before the increased focus on digital tools.

Figure 3. In-service teachers’ perception of preparation for using digital games in their

teaching.

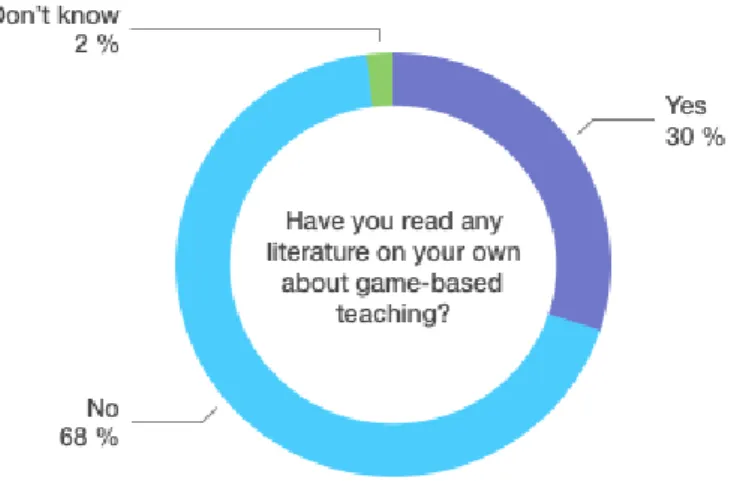

Since there seems to be a lack of coverage on how to use digital game-based teaching in the teacher training programs, Ian and Jack suggested that, if teachers out in the field have an interest in using digital games in their teaching, they can find information about it online in order to develop these skills. However, as shown in figure 2, 27 % of the teachers feel that they do not have the time nor resources to use digital games in their education, and this could mean that the teachers would not prioritize learning about digital game-based teaching on their own due to the lack of time. But since most of the teachers have not gotten any education on this topic, they have not been informed of the various benefits for language learning that digital games can provide and might therefore not think to research it. A total of 30 % of the teachers claim that they have read some literature on game-based teaching leaving 68 % of the teachers unaware of the research in this field (see fig. 4). The relevance

25

of integrating digital games in teaching practices becomes less obvious without any insight in the research that has been conducted in this field; one of the in-service teachers stated, in connection to whether they had been prepared to use digital games in their teaching, that “there are so many other parts in teacher ed that this one should be far down the priority list. Where is the huge internationally acknowledged research on this?”, indicating that there is a certain unawareness concerning the existing research and what benefits digital games hold.

Figure 4. A chart on whether in-service teachers have read about game-based teaching or not.

Another doorway for teachers into digital game-based teaching would potentially be in-service training. Interestingly enough, 24 % of teachers answered that it would be easy to get in-service training in this field; however, the majority, 58 %, was unsure and 18 % thought it would be difficult. Some factors mentioned here were once again time, money and

prioritization as pointed out by some of the in-service teachers: “Not sure what's available and not sure if it is my biggest priority when it comes to supporting my students”, “It’s a matter of financial funding”. This might then be a possibility for teachers with an interest in the method. However, without any information about digital game-based teaching in teacher training programs and without the knowledge about the accessibility of in-service training, the majority of teachers might not be likely to get in contact with this method of teaching.

As seen, together with the lack of time and resources, teachers ranked the lack of teacher education as the number one obstacle for the use of digital games in education (see fig. 2). This combined with the fact that 64 % of the teachers find digital games relevant for teaching purposes indicates that teachers see the potential and relevance of digital games, but

26

despite a large majority stating that they had not received any training on digital game-based teaching and that this would be a hindering factor, as well as the fact that only 4,1 % of the participating teachers had received any in-service training on the subject area, little over half, 55,1 %, of the teachers replied that they had used digital games in their classroom. Some of those wrote that they had read about gamification and that they as well as their students like games, whereas two others described them as fillers, something “you would give a student that’s finished and you wouldn’t know what to do with him/her”. These figures seem to indicate that some teachers have used games without having any knowledge on how they should be utilized in educational contexts, and the question is for which purpose games are then used and with what results. Considering the research that shows the difficulties with applying games efficiently and teacher educators’ points on the complexity of using them correctly, it is likely that using games without any supporting framework may not result in positive effects for learning.

5.5 Recommendations and action for the future

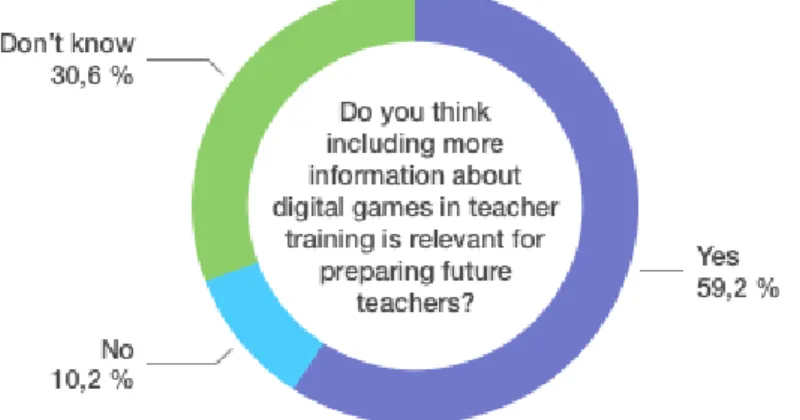

Beyond all the issues and the lack of current incorporation of digital game-based teaching into teacher training programs, the participants in this study do have recommendations for what should be done in the future. As already mentioned, all the teacher educators agreed that digital games can be important for language learning and should therefore be incorporated into teaching and teacher training. The in-service teachers, on the other hand, present a more mixed view. When asked if it would be relevant to add more information about digital games to teacher training to prepare future teachers, 59,2 % agreed that it would be relevant, 10,2 % disagreed, and 30,6 % did not know if it would be relevant (see fig. 5).

Figure 5. In-service teachers’ perception of the relevance of integrating more information

27

Overall, the teacher educators wish to see a greater inclusion of such tools in the teacher training program in the future. Donna stated: “I think both teacher training and in-service courses need to at least inform the teacher trainees about the availability and the possible benefits of using games as a tool”. Moreover, both Rory and Ian believe that game-based teaching should be integrated as much as possible into normal didactics and argue that it should not be a separate module. Ian mentions that at his university they had previously offered seminars to teacher students on how to integrate various digital tools into teaching, but very few students came to these. Ian speculates that this was because the seminars were not obligatory and did not offer credits, or simply because the students already had many other tasks which they prioritized. This led him to conclude that incorporating new tools, such as games, into the existing courses is better than adding them on top. Rory similarly states:

For sure, it should be there, in one way or another. But whether it should be a module of its own where it’s something you could choose or not; I rather think it should be integrated as much as possible into normal didactics. But it should be there.

Regarding the feasibility of integrating the tools, Ian, who holds responsibility over budget matters at his university states that “that should be financially possible. But I think it is important to make room for such activities, to give the teacher education students more input from other areas”. Another suggestion given was that teachers who have more experience with using this approach could be utilized in teacher training courses, so that teacher students can see ways of using games. Through meeting games in various contexts, the teacher

students can feel that maybe games are a good teaching method, instead of feeling forced to work with something that is unfamiliar. Donna suggests that maybe teachers “need to let go of the control of the classroom so they can use, if they have, gamers in class as the experts and let them show how it is being done to the rest of the class. Really taking advantage of the fact that they have gamers in class”. She also noted that it might be easier for teachers to learn how to incorporate game principles, so called gamification, into their teaching instead of using digital games such as COTS, as this might be less daunting and more manageable.

Finally, what is mentioned most frequently by the teacher educators, is that it is integral to have knowledge about the approach before using it in teaching. Martha explains:

28

I think it is a good thing to work with them in the teacher program, because it is not just something that you can say “here is a game, work with that”, you need theoretical background as well, learning how to do it before you can apply it.

The teacher educators also agree that digital game-based teaching should be incorporated in both teacher training and in-service training. This could be done using different methods; as Martha suggests, one way to work with integrating digital games could be with the text universe which contains multiple elements, such as fan fiction, cosplay and different versions of a story. Ultimately, there are many ways to approach this matter, but as Ian argues:

Given that computer games are so important in our society, I guess that bringing in knowledge from that area to training, teacher education and to schools, just can’t be wrong. As long as you don’t lose track of all the other important skills and important knowledge you have to give to your students using this, using computer games or computer game-like things in education seems to be a way of using something that the students and the pupils are already used to and that is important in their lives. If we integrated, you know, we have the content and we have the game and we learn ways of integrating the two into something that becomes more exciting, more interesting, more fun for the students and the pupils, I am sure that this must be the future.

29

6 Discussion

6.1 Teacher educators’ perceptions

As seen in the results section, the teacher educators presented many points on the

incorporation of digital game-based teaching into the teacher training programs. They all thought that it is a relevant approach to teaching and that it should be included more into teacher training. However, when it comes to the actual incorporation of digital game-based teaching in the current teacher training programs, this was seen to be very limited, as only one of the programs seen here offered information on the approach. Four out of the five interviewed teacher educators stated decisively that their universities do not adequately equip teacher students with the tools to use this approach. This was something they expressed should be changed, as it is an important skill for teachers. Even though this result does show a lack of teacher preparation, it does also show that the teacher educators are aware that there exists an issue, unlike a similar study in Norway where teacher educators’ opinions on

teacher preparation on the use of digital tools differed significantly from the teacher students’ perceptions (Wilhelmsen in Instefjord & Munthe, 2016). The major benefits that the

interviewees saw with using digital games were motivation, vocabulary learning, as well as other skills, while the nature of games was seen as something attractive to learners. These points can be seen to correspond with the existing research on the topic, that has shown positive effects of digital games and game environments for vocabulary and oral fluency (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012; Cardoso et al., 2015; Sundqvist, 2019; Franciosi, 2017),

motivation and reduction of anxiety (Iaremenko, 2017; Vosburg, 2017; Reinders & Wattana, 2015), and potential for deep learning (Ryu, 2013).

When it came to obstacles with incorporating digital game-based teaching, an important aspect brought up by Donna is whether digital games have the same benefits for language learning in the classroom as there are in extramural contexts. There are some studies that do look at DGBL and gamification in the classroom. Reinders & Wattana (2015) found that a game-based learning program has positive effects on university students’ willingness to communicate in the EFL classroom; Iaremenko (2017) found that gamification can have very positive effects for motivation in English language learning; and Franciosi (2017) discovered benefits for EFL vocabulary learning from computer game-based lessons. This suggests that