1

The prevalence of early childhood caries among

children between 2-4 years old in Kirikkale, Turkey

Supervisors:

Peter Carlsson, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malmo

Turksel Dulgergil, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Kirikkale

Master thesis (30hp) Programme in Dentistry 15 februari 2016 Malmö University Faculty of Odontology 205 06 Malmö

Lina Jaff

Shqipe Bala

2

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The aim of the study was to determine the early childhood caries

(ECC) prevalence among 2-4 years old children in selected areas of Kirikkale, Turkey. The study aims to find the association between ECC among children and the Streptococcus mutans (S.mutans) level in their mothers. The study should also determine possible associations between risk factors and children’s dental caries, and the association between risk factors and children’s S.mutans level.

Methods: This is a pilot study consisting of a clinical examination and a

questionnaire, designed to collect necessary data. The study population of 60 children, aged 2-4 years old, whom have been clinically examined to determine the ECC prevalence. The mothers’ S.mutans levels have been compared with the ECC prevalence among the children.

Results: The ECC prevalence was 45% and mean number of primary

decayed-filled teeth (dft) 2.1. The study could not show any correlation between S.mutans levels among mothers and ECC prevalence among children. However, the study showed a significant association between children’s age and dft. Furthermore, the study could not find any association between the different risk factors and dft, or children’s S.mutans levels.

Conclusion: The current study suggests that ECC prevalence is relatively high

(45%) among preschool children in selected areas of Kirikkale, Turkey. However, the study could not find any significant relationships between S.mutans levels among mothers’ and children’s ECC prevalence. In consistency with earlier studies in the field, results also suggest that the presence of S. mutans among preschool children is strongly connected to ECC.

3

Kariesprevalensen hos barn mellan 2-4 år i Kirikkale,

Turkiet

Handledare:

Peter Carlsson, Faculty of Dentistry, Malmö Högskola

Turksel Dulgergil, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Kirikkale

Masteruppsats (30hp) Tandläkarprogrammet 15 februari 2016 Malmö Högskola Odontologiska fakulteten 205 06 Malmö

Lina Jaff

Shqipe Bala

4

ABSTRAKT

Mål: Syftet med denna studie var att bestämma kariesprevalensen (ECC) hos 2-4 åriga barn i utvalda områden i Kirikkale, Turkiet, och undersöka associationen till moderns S.mutansnivå. Det undersöktes möjliga samband mellan barnens S. mutans nivå och förekomst av ECC. Utöver det valdes även att undersöka

sambandet mellan riskfaktorer och barnens kariesprevalens samt samband mellan riskfaktorer och barnens S. mutansnivå.

Metoder: En pilotstudie bestående av kliniska undersökningar och frågeformulär utformades för insamling och bearbetning av information. Studiepopulationen bestod av 60 barn mellan 2-4 år. De blev kliniskt undersökta för att bestämma ECC prevalensen. Mammors S. mutansnivåer jämfördes med barnens ECC prevalens.

Resultat: ECC prevalensen var 45% och medelvärdet av karierade fyllda primära tänder (dft) var 2.1. Studien kunde inte visa något signifikant samband mellan S. mutansnivån hos mödrar och ECC förekomsten bland barn. Däremot visade studien en signifikant relation mellan barnens ålder och dft. Studien visade inga samband mellan riskfaktorer och dft och ej heller någon association mellan riskfaktorer och barnets S.mutansnivå.

Slutsats: Studien visar att ECC prevalensen är relativt hög (45 %) bland förskolebarn inom de utvalda områdena av Kirikkale, Turkiet. Studien har inte kunnat finna något signifikant samband mellan S. mutansnivå bland mödrar och barnens ECC prevalens. I samstämmighet med andra tidigare studier, visade det också att förekomsten av S. mutans bland förskolebarn är starkt knuten till ECC.

5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 2

ABSTRAKT ... 4

INTRODUCTION ... 6

MATERIALS AND METHODS ... 11

Study design ... 11

Ethical clearance ... 11

Sample characteristics ... 11

Assessment of oral health status ... 11

Assessment of the child’s plaque sample of mutans streptococci. ... 12

Assessment of the mother’s salivary levels of mutans streptococci ... 12

Questionnaire ... 12

Statistical methods ... 13

RESULTS ... 14

DISCUSSION ... 16

Limitations and bias ... 18

Ethical and social aspects ... 19

CONCLUSIONS ... 19

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 20

6

INTRODUCTION

Despite the increased use of preventive methods and many significant

achievements in the field of oral health during the last few decades, dental caries is still a global epidemic. It is mostly prevalent amongst children and adolescents alike (1). It is a health issue of the utmost concern and the most common chronic disease to occur in both developing and industrialized countries (2). Between 60-90% of school children and nearly 100% of adults have carious lesions, and it is considered as one of the contributing causes of tooth loss in all age groups (3). Dental caries is a multi-factorial disease caused primarily by interaction of microorganisms with fermentable carbohydrates on a tooth surface (2,4). Cariogenic bacteria derive acids from fermentation of sugars, and other dietary carbohydrates that dissolve tooth minerals, and cause dental decay, or in medical terms, caries. The bacteria accumulate on the tooth surface and are known as dental plaque (2,4). The main cariogenic microorganisms, uniquely associated with caries and its progression are Streptococci, mainly Streptococcus mutans (S.mutans), Streptococcus sobrinus (S.sobrinus) and lactobacillus (4).These bacteria produce tooth enamel demineralizing acids from sugars and facilitate further plaque growth (2,4). Particularly S.mutans together with lactobacilli and yeasts are associated with the pathogenesis of dental caries (5). Increased presence of these microorganisms is associated with frequent sugar consumption (2,4,5). An extraordinary virulent form of caries, prevalent among children under 72 months of age, is Early Childhood Caries (ECC) as it has been described by American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) (6).

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research’s (NIDCR) defines ECC as caries presence on one or more primary teeth, in children of 1 to 5 years of age (7). Studies show variation of the ECC prevalence amongst children of different ages in different regions and among different socio-economical communities. In north-western European countries (England, Sweden, and Finland) ECC prevalence range from below 1% to 32% (8,9), while in some eastern European countries ECC prevalence is as high as 56% (10). In the US prevalence of dental caries in children between 2-5 years of age has increased from 24% in 1988-1994 to 28% in 1999-2004 (2,11,12). The ECC prevalence in Canada amongst children in larger populations is less than 5%, while the Native Canadians are considered a high risk population with 65% ECC prevalence (2,13). In developing countries, the prevalence of ECC is reported to be high. A study conducted in a semi-urban area of Sri Lanka showed that the prevalence of ECC was 32.19% among children aged 1-2 years (14), while in northern Philippines ECC prevalence ranges from 59% (2 year old children) to 94% (5 year old

children) (15). Prevalence of ECC in the general population of Turkey is 10%, but in the high socio-economic groups within the country only 8 % are affected (16). The prevalence may vary due to different definitions of ECC. Definitions can be referred to differently because of the diverse etiology of ECC in the studies; for example, focus can be placed on multiple factors rather than just inappropriate feeding methods (2).The difference in prevalence may also reflect income inequalities between different groups. Lower socio-economic status has been related to higher level of caries. Another strong association that has been found to higher level of caries is the mothers’ low level of oral health related knowledge. In addition, differences in dietary and oral habits might intensify the caries risk.

7 Nighttime bottle feeding and liquid containing sucrose is also considered to be associated with ECC (11-15).

Associated risk factors

Except for biological determinants causing ECC, there are important social and behavioral factors that affect this disease. Unhealthy and incorrect nutrition such as prolonged breastfeeding and excessive use of bottle feeding containing sucrose at night, lack of fluoride, poor oral hygiene and poor oral healthcare in general, are important social and behavioral determinants that influence ECC prevalence. These are used as caries risk assessment factors that are further applied for preventive purposes (10,14,15).

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding

Recent evidence states that breastfeeding benefits the health of children since it has a great protective effect against dental caries. It also provides immunity and infant nutrition. For this particular reason, it is therefore recommended by The World Health Organisation (WHO), that children should be breastfed for at least 6 months of age up to 24 months of age (17,18). Other studies have shown an association between breastfeeding and lower levels of dental caries (3), in contrary, another review has identified breastfeeding at night and the duration of breastfeeding, specifically over 18 months, as risk factors (19). However, the association between breastfeeding and ECC has not been confirmed (20). Few studies have investigated the comparison between breastfeeding and bottle feeding, and if it can contribute to a higher risk of dental caries. According to a recent review, breastfeeding prevents the disease, while bottle feeding does not (17). On the other hand, bottle feeding containing sucrose, at night has been identified as a risk factor for dental caries (19).

Socio-economic and educational factors

Studies confirmed strong associations between ECC and socio-economic groups (2). ECC is normally present in children who are born in poor economic

conditions, born in a single parent home, or with low educated parents; especially uneducated mothers. This is consistent with another study which stated that children in low-income families have four times higher primary decayed-missing-filled teeth (dmft) scores than children in high-income families (4).

Socio-economic conditions strongly influence health literacy which in turn also have an impact on general health. According to a study in Taiwan, it was more likely to find children with ECC whose mothers who had full-time jobs than those who had part-time jobs or were housewives. Children who live in poor economic

conditions don’t make their dental visits frequently until dental problems occur, or at an older age (21). Parents with high education are associated with lower

prevalence of ECC. Children with parents or siblings that have carious lesions are in a higher risk zone for development of ECC (4).

The potential influence of socio-economic status on oral health may in addition lead to a broader variety in dietary habits, thus, higher sugar consumption. In the review by Sheiham and Watt on inequalities in oral health, the authors indicated that the main causes of these inequalities are differences in patterns of

consumption of non-milk sugars and the use of fluoride toothpaste (22). Over the last three decades there has been a huge improvement in oral health, which is a result of increased fluoride toothpaste usage and improved socio-economic

8 statuses. To reduce the inequalities of oral health, a disease prevention and

strengthened oral health promotion policy should be implemented (22).

Oral hygiene and fluoride

The presence of dental plaque is corresponded with dental caries development, which is an established risk factor (23). The anatomy of teeth, mostly molars, play a role in the increasing risk of caries. The pits and fissures make it difficult to clean, which in turn, gives a higher risk of caries progression (24). Many studies have confirmed that a non-frequent tooth brushing and neglect of fluoride toothpaste are related with progression of dental caries. Children who do not brush their teeth at bedtime are exposed to a higher risk of early childhood caries. Therefore, parental guidance is needed, and is recommended until the children reach school age. This is due to their lack of ability to brush at early age (4). According to evidence, tooth brushing with fluoridated toothpaste twice a day is considered to be an important prophylactic measure to prevent dental caries in permanent dentition (25). The importance of fluoride toothpaste is mainly for accelerating enamel remineralization and resistance during the demineralization; since the concentration of fluoride in saliva remains for a longer time. Studies have showed that children at five years of age living in fluoridated areas had 50% less caries lesions than children in non-fluoridated areas (26).

Transmission of oral bacteria

Mothers are considered to be the reservoir of cariogenic bacteria by which the transfer of the bacteria occurs, thus, increasing the caries risk (27). The transmission process is still unknown but it may be due to sharing the same

utensils and food, or, through the close contact between mother and child (4). The AAPD recommends measures that decrease transmission of cariogenic bacteria such as reduction of the parent’s and sibling’s S.mutans levels, through good oral health, and minimization of saliva-sharing activities (28). Children whose mothers had a high S.mutans level, had higher risk for receiving the cariogenic

microorganisms compared to children whose mothers had low S.mutans levels (4). In a study conducted by Al Shukairy et al., no statistically significant difference was found between mothers of children with severe early childhood caries (SECC) and mothers of caries-free children, in regard to S.mutans level (29).

Early identification and consequences of severe untreated ECC

Early discovery and treatment of dental caries in children will prevent not only dental diseases but also costly long-term negative health effects. Untreated severe ECC has many health consequences, in addition to the oral health; the general health and quality of life will subsequently be adversely affected. As the treatment for dental caries in young children delays, the caries will progress perhaps along with increased pain and discomfort. In turn, the child might lose appetite, and consequently, deterioration of the health condition. As a result, the treatments might be frequent and more expensive than expected (2,30).

Oral health affects the child both psychologically and physically, as well as the feeling of social well-being. Severe ECC in children under the age of 2 years has been associated with reduced growth due to malnutrition (2,31). Impaired speech development and reduced self-esteem are all related consequences of early tooth loss. Children affected with ECC increases the risk for future oral health

9 problems. Caries in early years is a great predictor for future caries development in late childhood (2,32).

Furthermore, the emphasis should be averted from technical intervention and restorative dentistry to prophylactic treatments, where parents and patients are advised about nutritional and dietary habits and oral hygiene that reduce the risk of progressing and development of dental caries. Therefore, it is important to comprehend and educate the implication of oral health since individuals are susceptible to the disease throughout life (30,33).

Treatment of ECC

Children with newly erupted primary teeth have normally immature enamel. It is important to pay attention to any signs of tooth decay to prevent caries

progression. If the caries cannot be detected and controlled in time, the first carious lesion will be a start of a long list of treatment. It is mainly important to investigate the underlying cause of the child’s caries presence. To investigate whether it is due to diet and/or tooth brushing is of importance to control, since they are the risk factors of caries. Parents must be informed about the side effects caused by sweetened meals and bottle feeding at nighttime. In addition, the parents should be informed about the importance of tooth brushing, how to brush their child’s teeth properly with fluoride toothpaste, and also the twice a day regularly (30).

A recent study has shown that applying fluoride varnish twice a year in children up to 3 years old did not reduce caries significantly in higher risk areas, where brushing teeth with fluoride toothpaste was already part of the daily routines (34). Furthermore, other studies have shown that dental health programs that also contain fluoride varnish twice a year reduces the incidence of ECC in comparison with dental health programs without fluoride varnish. Moreover, a good way to prevent carious lesion, is having children with caries risk visit clinics for fluoride varnish application. This is considered to be an effective clinic-bound practice (35,36).

The chosen treatment of dental caries in primary teeth, many factors need to be considered; such as the extent of the carious lesion, time left to exfoliation and caries activity. Also, if a carious lesion may cause pain before the tooth exfoliates, is important to consider. Active dentine caries, especially in occlusal and

interproximal caries on molars, should be treated with restoration immediately. Carious lesion on the first primary molars is treated with restoration after caries excavating or drilling. In the selection of restoration, the following can be used; glass ionomer cements, resin-reinforced glass ionomer cements and dental

compomers. When caries extends deeply, a stepwise caries excavating needs to be done. This treatment involves removing most of the decayed tooth substance, leaving the deepest layer of the caries pulpally, thereafter covered with a temporary restoration. If a pulp lesion appears, the following therapy can be chosen; partial pulp amputation or extraction. The choice of therapy depends on the age of the child and the value of the teeth for future dentition development. Partial pulp amputation implies removal of the most superficial part of crown pulp and then having calcium hydroxide applied with a restoration (37).

Before starting any treatment, the child should have a tailored introduction to treatment e.g. using the tell-show-do method (38). The purpose of the method is to explain and show every step of the treatment to the child before it is performed to the child. This is in order to make the child feel safe during treatment (39). All

10 invasive treatments should be performed under local anesthesia, to acquire a treatment free from pain (39).

If the child has difficulty coping with the treatment, in case of extensive treatment needs, use of sedation or even general anesthesia may be required (40).

AIM AND HYPOTHESIS

The objective of this study is:

– To determine the prevalence of ECC among 2 to 4 years old children in selected areas of Kirikkale, Turkey;

– To investigate possible correlation between ECC presence amongst this group of children and their mothers’ S. Mutans level.

– To investigate possible association between risk factors and dental caries in children.

– To investigate possible association between risk factors and child’s

S.mutans level and if the level of S.mutans is associated with the incidence of ECC.

The study is based on the following hypothesis:

- Dental caries is highly prevalent among children between 2-4 years old in Kirikkale.

- There is a positive correlation between the presence of ECC in the child and mother’s S.mutans level.

- There is an association between the presence of a child’s dental caries and risk factors such as bottle feeding, prolonged breastfeeding and poor oral hygiene etc.

- Risk factors are associated with the level of S.mutans in the oral microflora of children.

The prevalence of dental caries among children between 2-4 years old is unknown in the Kirikkale region. Therefore, the main aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of early childhood caries in the Kirikkale region.

11

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A pilot study was designed to carry out this investigation. A pilot study is a standard research method, allowing to conduct a preliminary analysis. This method was chosen to fit the time schedule of the study as well as matching the constricted resources available in remote populations, often with outdated insight and technology. Also testing the feasibility of the study for later use and if it may be worth following up in a larger study.

The study was conducted through a questionnaire and clinical examination for the collection of data. In the study, two bacteria tests were also included (Dentocult® strip mutans test, CRT® test) and information for raising awareness among mothers.

Ethical clearance

The study research project was sent to the local Ethics Committee, Faculty of Odontology at Malmo University in Sweden(OD2015/61). It was also sent to the local Ethics Committee, Faculty of Odontology at Kirikkale University in Turkey for approval. Information was provided to parents and written consents were obtained from the parents. The study period was during July and August 2015.

Sample characteristics

The study population consisted of 60 children, aged at 2-4 years old. The children that were eligible to participate in this study had to fulfill the following criteria: 1) children with good general health 2) who lived in Kirikkale 3) who were cooperative for oral examination 4) the absence of antibiotics therapy for 15 days prior to the examination and 5) participating mothers.

A convenience sample of 60 participants was obtained. The mother-child pairs that chose to participate have the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The study was conducted in two different governmental hospitals; the Hacilar and Asigimahmutlar in Kirikkale, both located in low socio-economic areas.

The calibration procedure

All children were examined by a dental student and before performing the examination the dental student had to be calibrated. During a period, the initial training and calibration was obtained, focusing on calibrating the dental student examiner to a gold standard examiner. It is required to meet a certain level

agreement with the gold standard examiner to become a calibrated examiner. This, by comparing results from each examination between the dental student examiner and the gold standard examiner (41). The calibration was not statistically

calculated. The calibration was performed with a group of 200 children, at 2-10 years of age, in a different region of Turkey.

Assessment of oral health status

Children were examined under an electrical light source with a probe and mouth mirror. The teeth were cleaned and dried with sterile gauze pads before recording dental caries. The CPI probe was used, to register visible caries on occlusal, buccal and lingual tooth surface. If the children did not fully cooperate, the visible caries was registered with the non-tactile technique (“lift the lip”). This occurred with 5 of totally 60 children. After visual and tactile inspection of the smooth surfaces, pits and fissures; dental caries were recorded as “cavity in the dentin

12 and/or enamel” according to WHO criteria and all non-cavitated carious lesions were disregarded (42). The total caries experience was registered as number of primary decayed filled teeth (dft). Missing teeth were ignored, because of early age and all teeth haven’t erupted. No radiographs was taken.

Assessment of the child’s plaque sample of mutans streptococci.

We used sterilized toothpicks to collect the plaque from the primary teeth.

Thereafter the plaque on the toothpicks was placed on CRT® bacteria test (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein). The CRT bacteria test was placed in an

incubator at 35-37 ºC (95-99 ºF) for 48 hours (43). By means of the CRT bacteria test, the child’s S.mutans was identified. The classifications were based on the same template as for the mothers.

Assessment of the mother’s salivary levels of mutans streptococci

A strip mutans test (Dentocult® SM, Oral Care, Tokyo, Japan) was performed for each mother for comparison of bacterial occurrence. The strip mutans test was used for the detection of mutans streptococcus (43). It was taken from the mother to investigate the correlation between presence of ECC and the mother’s S.mutans level. The mothers were advised to abstain from food, drinks and teeth brushing for at least 1 hour prior to the test. Each mother chewed a piece of paraffin for 1 minute for extruding bacteria from tooth surfaces to saliva and at the same time stimulate saliva. A strip was rotated on their tongues 10 times and was removed between their lips. The strip was placed in the culture medium (bacitracin discs) and further in an incubator at 35-37 ºC (95-99 ºF) for 48 hours.

Fig 1. Manufacturer model chart of strip mutans.

To define the low level of S.mutans, strip mutans class 0 and class 1 was used as one group. This is because of the small number of samples carrying S.mutans (class 0= no growth, class 1= 1-104 CFU/ml saliv). The high level of mutans streptococcus, class 2 or higher as used as one group (class 2= 105-106 CFU/ml saliv, class 3 > 106 CFU/ml saliv). This classification was based on a template provided by the manufacturer (fig. 1).

Questionnaire

A simple questionnaire was administrated to the parents of the children to gather information (breastfeeding duration, bottle feeding, bottle at night, sharing of utensils such as spoon, tooth brushing and food intake rate). When the parents had any questions about the given questionnaire, the investigators answered and completed the questionnaire directly with the parents. The questionnaire template

13 was constructed in English and translated into Turkish, since the official language in Kirikkale is Turkish. The questionnaire template was translated by a dentist to avoid missing of information and misinterpretation. No backward translation was made.

Thereafter, when all data had been collected, the examiner went through the questionnaire as an education opportunity for the parents, where the examiner made recommendations for preventive care and informed the parents for increased awareness and motivation to perform oral health preventive behaviors for their children.

Statistical methods

One way analyses of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether any of the following risk factors, i.e. bottle feeding, prolonged breastfeeding etc. were significantly associated with the presence of childrens’ dental caries, dft, as a dependent variable.

The Fisher exact test was used to determine if there were any relationships between risk factors and a child’s S.mutans levels in the oral microflora. The level of statistical significance P<0.05 was chosen.

Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate if age was mainly associated with the presence of childrens’ dental caries, dft.

For analyzation of possible associations between the mother-child pairs, the following groups were divided into:

The percentage of high level S.mutans presence among mothers of the children with ECC

The percentage of high level S.mutans presence among mothers of the caries free children.

We have defined high level S.mutans as 2 or more according to manufacturer’s instructions. By comparing those two values by cross-tabs we would assess possible association between mothers’ S.mutans level and ECC. To analyze the cross tabulations, the Chi square test was used. Chi Square test was also used to determine if there was any association between childrens’ S.mutans level and ECC.

14

RESULTS

The study population consisted of 60 children; 32 boys and 28 girls, and was collected from two medical centers in Kirikkale. The mean age of the participating children was 2.9 years. All of the mother-child pairs that were given the

opportunity to join the study, completed the entire study process that was required. Table 1. The presence of ECC (early childhood caries), dft (primary decayed filled

teeth) in children of different ages between 2-4 years old and high S.mutans level (2-3) according to the manufacturer, in children of different ages.

ECC Mean dft High S.mutans (2-3)

2 years old (N=28) 7 0.8 5/28

3 years old (N=11) 6 2.8 5/11

4 years old (N=21) 14 3.5 11/21

Total (N=60) 27 2.1 21/60

Children had higher mean dft as they reached older age (Table 1). It showed a statistically significant relationship between age and dft, (p=0.003) according to multiple regression analysis. Also, the presence of S.mutans level was higher as they reached an older age (Table 1).

Table 2. The relationship between mothers’ S.mutans levels (low 0-1, high 2-3)

according to the manufacturer and ECC (early childhood caries).

Mothers’ S.mutans level 0-1 Mothers’ S.mutans level 2-3 Total

Children with ECC 13 14 27

Children without ECC 15 18 33

Total 28 32 60

Analysis using the chi-square test showed that there was no statistically significant relationships (p=0.835) between mothers salivary S.mutans and children with early childhood caries (ECC), (Table 2).

Table 3. The relationship between childrens’ S.mutans level (low 0-1, high 2-3)

according to the manufacturer and ECC (early childhood caries).

Children S.mutans level 0-1 S.mutan level 2-3

Without caries 33 0

With caries 5 22

The plaque that have been collected and been placed on CRT bacteria test showed that the children with dental caries had higher S.mutans level than children

without dental caries, (p=0.000) according to fisher test.The level of S.mutans in the oral microflora of children was associated with the prevalence of ECC (Table 3).

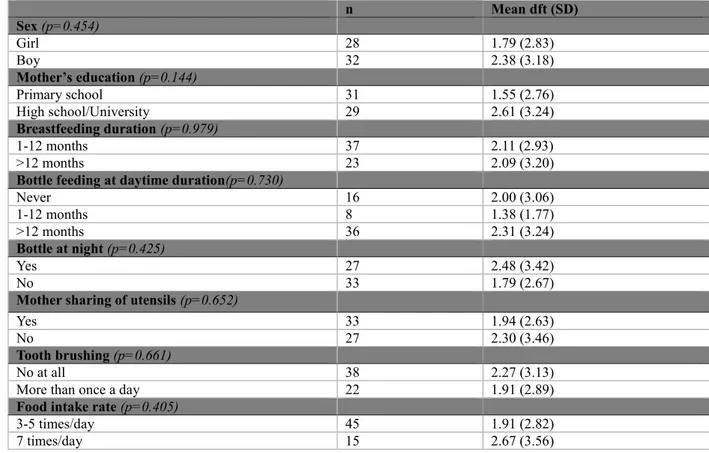

15 Table 4. ANOVA test of the risk factors in relationship to mean numbers of dft

(primary decayed, filled teeth).

n Mean dft (SD) Sex (p=0.454) Girl 28 1.79 (2.83) Boy 32 2.38 (3.18) Mother’s education (p=0.144) Primary school 31 1.55 (2.76) High school/University 29 2.61 (3.24) Breastfeeding duration (p=0.979) 1-12 months 37 2.11 (2.93) >12 months 23 2.09 (3.20)

Bottle feeding at daytime duration(p=0.730)

Never 16 2.00 (3.06) 1-12 months 8 1.38 (1.77) >12 months 36 2.31 (3.24) Bottle at night (p=0.425) Yes 27 2.48 (3.42) No 33 1.79 (2.67)

Mother sharing of utensils (p=0.652)

Yes 33 1.94 (2.63)

No 27 2.30 (3.46)

Tooth brushing (p=0.661)

No at all 38 2.27 (3.13)

More than once a day 22 1.91 (2.89)

Food intake rate (p=0.405)

3-5 times/day 45 1.91 (2.82)

7 times/day 15 2.67 (3.56)

Table 5. Fisher test of risk factors in relationship to the child’s S.mutans level

(low 0-1, high 2-3) according to the manufacturer.

n S.mutans Low 0-1 S.mutans High 2-3

Sex (p=0.496) Girl 28 19 9 Boy 32 19 13 Mother’s education (p=0.496) Primary school 31 22 9 High school/University 29 16 13 Breastfeeding duration (p=0.1000) 1-12 months 37 23 14 >12 months 23 15 8

Bottle feeding at daytime duration (p=0.927)

Never 16 11 5 1-12 months 8 5 3 >12 months 36 22 14 Bottle at night (p=0.788) Yes 27 16 11 No 33 22 11

Mother sharing utensils (p=0.789)

Yes 33 20 13

No 27 18 9

Tooth brushing (p=1.000)

No at all 38 23 14

More than once a day 22 14 8

Food intake rate (p=0.757)

3-5 times/day 45 29 16

16 ANOVA and Fisher tests were used to statistically process data collected through questionnaire and clinical tests. As presented in tables 4 and 5, no significant relationship was found between the different risk factors and the presence of dft or S.mutans levels. Risk factors considered and analyzed in the study were: Maternal education; breastfeeding duration, bottle at night, mother sharing utensils, tooth brushing and food intake rate.

DISCUSSION

One of the main objectives of this study was to determine ECC prevalence among 2-4 years old children in selected areas of Kirikkale, Turkey. The study was conducted in two different low socio-economic areas. The study population consisted of 60 children, aged between 2-4 years. During the examination of children, caries was recorded as “cavity in the dentin and/or enamel” according to WHO criteria and the total caries experience was registered as dft.

Results of this study showed that ECC prevalence among 2-4 years old children in Kirikkale is 45%, with mean dft of 2.1. This is relatively high percentage, higher than ECC prevalence in Western European countries and the US (2,9,11,12), and it is particularly high if we consider the young age of children (2-4 years)

participating in the study. We may therefore conclude that our initial hypothesis stating that dental caries is highly prevalent among children between 2-4 years old in Kirikkale, has proved to be right.

However, ECC prevalence of 45% is lower than ECC prevalence in some developing and Eastern European countries (2,15). A more extended study

conducted by Dogan et al., in city area of Kirikkale showed an ECC prevalence of 17.7% with mean dft of 0.63. The study was conducted among 3171 children aged between 8 and 60 months (44). This relatively low mean age and higher

socio-economic level in city area of Kirikkale, may explain considerable lower ECC rate (44). In a similar study conducted by Ozer et al., in Samsun, Turkey, the ECC prevalence rate was 49.6 %, while mean dft was 2.87 (45). Those figures are slightly higher than results in our study. The study population in Samsun, Turkey consisted of a larger group (226 participants) and of slightly older children (3-6 years). All those mentioned rates are considerably lower than results reported in earlier studies in Turkey. In the earlier study conducted by Olmez et al., in rural Ankara, the ECC prevalence was 70.5%, with mean dft rate 6.2. In this study, 95 children aged 9-57 months were examined (16). Similarly, in the study conducted by Namal et al., in Istanbul, including 598 examined preschool children, 74.1% had experienced dental caries- Mean age of the examined children in this study was 5.33 (46). These figures may indicate some positive development and decreasing of ECC prevalence and dft among preschool children in Turkey. Still, different factors specific to each study, such as mean age of participating children, socio-economic level and dental environment, have impact on results and

therefore ECC prevalence can vary significantly within the same area or country. Another objective of this study was to investigate a possible correlation between ECC presence amongst this group of children and their mother’s S. mutans level. Objective was based on the hypothesis that, association between the presence of ECC and mother’s S.mutans level, exists. S. mutans and other cariogenic bacteria are transmitted to children right after the eruption of teeth. The American

17 for decreasing ECC rate that decrease transmission of cariogenic bacteria, such as the reduction of the parent’s/sibling’s MS levels (better oral health) and

minimization of saliva sharing activities (47).

However, results of this study could not confirm the hypothesis. The study could not find a significant association between high S.mutans levels among mothers and ECC prevalence among children (p=0.835). In 14 cases (52%) of ECC, mothers of the children had low levels of S.mutans (0-1), while in 13 cases (48%) of ECC, mothers of the children had high levels of S.mutans (2-3). Likewise, in the study conducted by Al Shukairy et al., no statistically significant difference with respect to S.mutans level were found between mothers of children with caries and mothers of caries free children (29). One factor that could have affected the results of our study, is a possible recent caries infection among mothers of the children without ECC. Caries presence resulting in high S.mutans level may have deviated the results. Another factor that we should keep in mind throughout discussion is that our study was limited in sampling numbers.

On the other hand, a study found clear association between high S.mutans levels among children and ECC rate, where in 22 from 27 cases with ECC (81%), children had a high level of S.mutans (23). Study showed an association between the level of S.mutans in the oral microflora of children and the prevalence of ECC. This finding is consistent with other studies that have studied the

phenomenon, e.g. Kanasi et al., found strong associations between S. mutans and caries (48); Seki et al., determined S.mutans as one of five significant variables associated with caries (49); while Okada et al., found S.mutans and sugar sweetened beverages to be the only significant caries risk factors among very young (preschool) children (50).

The third hypothesis in this study stated that: “there is an association between the presence of a child’s dental caries and risk factors.” Data collected through questionnaire and clinical examination were processed in order to find mutual relations between considered risk factors and caries (table 4). ANOVA test was used to determine the significance of correlation. Study results showed no significant correlation between considered risk factors (Mother’s education; Breastfeeding duration; Bottle feeding; Bottle at night; Mother sharing utensils; Tooth brushing; Food intake rate) and the presence of dental caries. Therefore, after processing collected data, we have to conclude that this hypothesis has been disproved.

Various earlier studies analyzing similar correlations showed different results. A study conducted by Schroth et al., found that low maternal education is associated with increased caries activity, while bottle feeding and bedtime bottle use were not found to be significantly associated with an increased ECC (51). Campus et al., concluded that bottle feeding at night and low socio-economic level are associated with ECC, while tooth brushing frequency showed no significant association with ECC level (52). Ozer et al., found significant associations between ECC prevalence and both bottle feeding at night and maternal education (45). Wennhall I et al., found significant association between caries and frequent intake of meals (53). Considering the breastfeeding duration as one of the risk factors included in the study, an early

systematic review conducted by Valaitis et al., found that breastfeeding for over one year may be associated with ECC. At the same time, due to the lack of

18 consistency and conflicting findings in reviewed articles, no definitive time for breastfeeding duration was determined (54). Study by Kato et al., found

correlation between 6-7 months breastfeeding and increased caries risk at age of 30 months. However, according to the same study this correlation decreases as children grow older (55). This finding by Kato et al., may explain the lack of significant correlation between one of the risk factors (breastfeeding duration) and caries in our study, since most of the participating children were older than 30 months. Regarding other risk factors considered in our study, although processed data showed some difference between ECC and risk factors versus caries free children and risk factors, we have to conclude that study found no significant correlation between risk factors and ECC presence.

The fourth and final hypothesis in this study stated that: “risk factors are associated with the level of S.mutans in the oral microflora of children.” The collected data was processed and analyzed in order to find a possible correlation between S.mutans levels and considered risk factors. The Fisher test was used to determine if there was any significant correlation between S.mutans levels and risk factors (Table 5). Results showed no significant correlation between risk factors and S.mutans levels. Therefore, we have concluded that the hypothesis of this study has not been proven. Once again, this study was limited, with small sample size, without possibility to match the age of the children or other related factors. The questionnaire used for this investigation was short and brief. The use of a more extended questionnaire on the larger sample group may have been able to uncover more epidemiological information on ECC and S.mutans levels. A larger investigation with a larger sample is required in order to get more reliable findings.

Limitations and bias

The results of the current study must be taken into consideration within the context of the study’s limitations. The study had a limited sample with 60 mother-child pairings. Most of the associations were not found to be statistically

significant due to the limited sample size. This may be proven differently if a larger sample size was used.

Identifications and registration of caries cavitation holds the potential to be different depending on the child, much due to their age between 2-4 years old. Five children among totally 60 children didn’t fully cooperate during the examination, which made it impossible to use the intended tactile-visual technique. Instead, a non-tactile technique (“lift the lip”) was used. In turn, the non-tactile technique could give rise to bias, under-diagnosing and

over-diagnosing could be given, i.e. missing caries lesions respectively assuming dark spots as caries lesions.

Another potential bias could be recall bias that may have been occurred. The bias could arise because of the parents answering questions in a way that they think will lead to being socially accepted or if the questions appear to be sensitive to answer, there is possibility that dishonestly takes place.

There is minimal risk regarding S.mutans colonization, for other types of bacteria, may occur in colonization even though the specificity of strip mutans test is high, which in turn leads to bias (56).

19

Ethical and social aspects

An information sheet that had been provided to parents, and written consents that have been obtained from the parents, made them aware of the possibility to interrupt participation at any time. All collected data of the participants were maintained in secrecy and were protected by encoding all the processed data acquisition. The results are published anonymously and under large groups of participants. The criteria of Helsinki declarations were fulfilled (57).

This research will hopefully result in increasing parental knowledge regarding oral health and making the parents aware of the opportunities to reduce dental caries transmission to their children, also how to eliminate the root causes of ECC, and to maintain a better oral health for their child.

The fact that dental caries is preventable and can be reversed, gives the

opportunity to evade consequential and costly long-term disadvantaged effects. Hopefully the examination part of this study will evoke parental interest and reinforce an understanding of the importance of parental participation, in prevention of oral health.

Within the limits of this research, the expectations were that most mothers are unaware of ECC and its association with risk factors. It’s most often thought that parents generally have inadequate education regarding oral health, and preventive strategies and that mothers are the main transmission agents. It highlights and justifies the importance for implementing preventive educational programs for parents where prolonged parental assistance and guidance are important. Awareness among many other factors could affect the presence of dft. Additionally, the findings from this study will hopefully provide benefits for dental care practices and a basis for future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study results suggest that ECC prevalence is relatively high (45%) among preschool children in selected areas of Kirikkale, Turkey. However, the study could not find any significant relationship between S.mutans level among mothers and children ECC prevalence. In consistency with earlier studies in the field, results also suggest that presence of S. mutans among preschool children is strongly connected with ECC.

20

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, we would like to thank our internal supervisor Peter Carlsson and Pr. Gunilla Klingberg for their excellent guidance, and express our sincere gratitude to our external supervisor Pr. Turksel Dulgergil for his time, precious support, and effort to help us in order to manage this research study abroad.

Our sincere thanks and appreciation goes to to Dr. Jayanthi Stjernswärd for inspiration, feedback and encouragement throughout the study and to Per-Erik Isberg for helping us with statistical analysis.

Besides our supervisors, we would like to thank Dr. Elif Ulku, Dr. Demir, Dr. Umut Unver and Dr. Baykal Tok who provided us with an opportunity and access to perform our research study in the governmental hospitals.

This study was supported by TePe and Colgate Company with providing dental kits and Minor field studies/SIDA for the scholarship, which was greatly appreciated.

Additionally, a big thank to all participating mothers and children that made this study possible.

21

REFERENCES

1. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res 2015; 94: 650-658.

2. Colak H, Dulgergil CT, Dalli M, Hamidi MM. Early childhood caries update: a review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2013; 4: 29-38. 3. World Health Organization. Oral health.

www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheet/fs318/en/; 2015.10.05.

4. Zafar S, Harnekar SY, Siddiqi A. Early childhood caries: etiology, clinical considerations, consequences and management. International Dentistry SA 2009; 11: 24–36.

5. Ersin NK, Eronat N, Cogulu D, Uzel A, Aksit S. Association of maternal-child characteristics as a factor in early childhood caries and salivary bacterial counts. J Dent Child (Chic) 2006; 73: 105-111.

6. Marrs JA, Trumbley S, Malik G. Early childhood caries: determining the risk factors and assessing the prevention strategies for nursing intervention.

PediatrNurs 2011; 37: 9-15.

7. Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. A report of a workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial

Research, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Health Care Financing Administration. J Public Health Dent 1999; 59: 192-197.

8. Douglass JM, Tinanoff N, Tang JM, Altman DS. Dental caries patterns and oral health behaviors in Arizona infants and toddlers. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol 2001; 29: 14-22.

9. Davies GM, Blinkhorn FA, Duxbury JT. Caries among 3-year-olds in greater Manchester. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 381-384.

10. Szatko F, Wierzbicka M, Dybizbanska E, Struzycka I, Iwanicka-Frankowska E. Oral health of Polish three-year-olds and mothers' oral health-related

knowledge. Community Dent Health 2004; 21: 175-180.

11. Berkowitz RJ. Causes, treatment and prevention of early childhood caries: a microbiologic perspective. J Can Dent Assoc 2003; 69: 304-307.

12. Tang JM, Altman DS, Robertson DC, O'Sullivan DM, Douglass JM, Tinanoff N. Dental caries prevalence and treatment levels in Arizona preschool children. Public Health Rep 1997; 112: 319-29; 330-1.

22 13. Peressini S, Leake JL, Mayhall JT, Maar M, Trudeau R. Prevalence of early childhood caries among First Nations children. District of Manitoulin, Ontario. Int J Paediatr Dent 2004; 14: 101-110.

14. Kumarihamy SL, Subasinghe LD, Jayasekara P, Kularatna SM, Palipana PD. The prevalence of Early Childhood Caries in 1-2 yrs olds in a semi-urban area of Sri Lanka. BMC Res Notes 2011; 4: 336.

15. Carino KM, Shinada K, Kawaguchi Y. Early childhood caries in northern Philippines. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31: 81-89.

16. Olmez S, Uzamis M, Erdem G. Association between early childhood caries and clinical, microbiological, oral hygiene and dietary variables in rural Turkish children. Turk J Pediatr 2003; 45: 231-236.

17. Avila WM, Pordeus IA, Paiva SM, Martins CC. Breast and bottle feeding as risk factors for dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0142922.

18. World Health Organisation. Global Strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: WHO 2003.

19. Harris R, Nicoll AD, Adair PM, Pine CM. Risk factors for dental caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent Health 2004; 21: 71-85.

20. Roberts GJ, Cleaton-Jones PE, Fatti LP, Richardson BD, Sinwel RE, Hargreaves JA et al. Patterns of breast and bottle feeding and their association with dental caries in 1- to 4-year-old South African children. 2. A case control study of children with nursing caries. Community Dent Health 1994; 11: 38-41. 21. Tsai AI, Chen CY, Li LA, Hsiang CL, Hsu KH. Risk indicators for early childhood caries in Taiwan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006; 34: 437-445. 22. Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000; 28: 399-406. 23. Karjalainen S, Soderling E, Sewon L, Lapinleimu H, Simell O. A prospective study on sucrose consumption, visible plaque and caries in children from 3 to 6 years of age. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29: 136-142.

24. Fejerskov O, Nyvad B. Clinical appearances of caries lesions. In: Fejerskov O, Kidd E, editors. Dental Caries. The disease and its clinical management. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard, 2008: 8-19.

25. SBU. Att förebygga karies. En systematisk litteratur översikt. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering (SBU); 2007.

26. Shellis RP, Duckworth RM. Studies on the cariostatic mechanisms of fluoride. Int Dent J 1994; 44: 263-273.

23 27. Milgrom P, Riedy CA, Weinstein P, Tanner AC, Manibusan L, Bruss J.

Dental caries and its relationship to bacterial infection, hypoplasia, diet, and oral hygiene in 6- to 36-month-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000; 28: 295-306.

28. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Symposium on the prevention of oral dsease in children and adolescents. Pediatr Dent 2006; 28: 96-198.

29. Al Shukairy H, Alamoudi N, Farsi N, Al Mushayt A, Masoud I. A comparative study of Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in mothers and children with severe early childhood caries (SECC) versus a caries free group of children and their corresponding mothers. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2006; 31: 80-85. 30. Koch G, Poulsen S, Twetman S. Caries prevention. In: Koch G, Poulsen S, editors. Pediatric Dentistry. A clinical approach. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 91-108.

31. Lara-Carrillo E. Clinical, salivary and bacterial markers on the orthodontic treatment. In: Ming-yu L. Contemporary approach to dental caries. 2012.

32. Tove I. Wigen and Nina J. Wang. Health behaviors and family characteristics in early childhood influence caries development. A longitudinal study based on data from MoBa. Norwegian journal of epidemiology 2014; 24: 91-95.

33. Selwitz RH1, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet 2007; 369: 51-9. 34. Anderson M, Dahllöf G, Twetman S, Jansson L, Bergenlid AC, Grindefjord M. Effectiveness of early preventive intervention with semiannual fluoride varnish application in toddlers living in high-risk areas: a stratified cluster-randomized controlled trial. Caries Research 2014; 50: 17-23.

35. Twetman S. Prevention of early childhood caries (ECC). Review of literature published 1998-2007. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2008; 9: 12-18.

36. Marinho VCC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013.

37. Mejáre I, Raadal M, Espelid I. Diagnosis and management of dental caries. In: Koch G, Poulsen S, editors. Pediatric Dentistry: A clinical approach. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 110-140.

38. Vogell S. General anesthesia in the treatment of early childhood caries. Dimensions of Dentl Hygiene 2012; 10: 34-39.

39. Klingberg G, Raadal M, Arnrup K. Dental fear and behavior management problems. In: Koch G, Poulsen S, editors. Pediatric Dentistry: A clinical approach. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 32-43.

24 40. Raadal M, Lundeberg S, Haukali G. Pain, pain control, and sedation. In: Koch G, Poulsen S, editors. Pediatric Dentistry: A clinical approach. 2nd ed.

Copenhagen: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 44-60.

41. Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K, Tinanoff N, Batliner TS, Jue B, Santo W, et al. Examination criteria and calibration procedures for prevention trials of the Early Childhood Caries Collaborating Centers. J Public Health Dent 2015; 75: 317-326.

42. Kavvadia K, Agouropoulos A, Gizani S, Papagiannouli L, Twetman S. Caries risk profiles in 2- to 6-year-old Greek children using the Cariogram. Eur J Dent 2012; 6: 415-421.

43. Lara-Carrillo E. Clinical, salivary and bacterial markers on the orthodontic treatment. In: Ming-yu L. Contemporary approach to dental caries. 2012: 155-180.

44. Dogan D, Dulgergil CT, Mutluay AT, Yildirim I, Hamidi MM, Colak H. Prevalence of caries among preschool-aged children in a central Anatolian population. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2013; 4: 325-329.

45. Ozer S, Sen Tunc E, Bayrak S, Egilmez T. Evaluation of certain risk factors for early childhood caries in Samsun, Turkey. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2011; 12: 103-106.

46. Namal N, Vehit HE, Can G. Risk factors for dental caries in Turkish preschool children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2005; 23: 115-118.

47. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. 2014.

48. Kanasi E, Johansson I, Lu SC, Kressin NR, Nunn ME, Kent R Jr, et al. Microbial risk markers for childhood caries in pediatricians' offices. J Dent Res 2010; 89: 378-383.

49. Seki M, Yamashita Y, Shibata Y, Torigoe H, Tsuda H, Maeno M. Effect of mixed mutans streptococci colonization on caries development. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2006; 21: 47-52.

50. Okada M, Soda Y, Hayashi F, Doi T, Suzuki J, Miura K, et al. Longitudinal study of dental caries incidence associated with Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in pre-school children. J Med Microbiol 2005; 54: 661-665.

51. Schroth RJ, Moffatt ME. Determinants of early childhood caries (ECC) in a rural Manitoba community: a pilot study. Pediatr Dent 2005; 27: 114-120. 52. Campus G, Solinas G, Sanna A, Maida C, Castiglia P. Determinants of ECC in Sardinian preschool children. Community Dent Health 2007; 24: 253-256.

25 53. Wennhall I, Matsson L, Schroder U, Twetman S. Caries prevalence in 3-year-old children living in a low socio-economic multicultural urban area in southern Sweden. Swed Dent J 2002; 26: 167-172.

54. Valaitis R, Hesch R, Passarelli C, Sheehan D, Sinton J. A systematic review of the relationship between breastfeeding and early childhood caries. Can J Public Health 2000; 91: 411-417.

55. Kato T, Yorifuji T, Yamakawa M, Inoue S, Saito K, Doi H, et al. Association of breast feeding with early childhood dental caries: Japanese population-based study. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006982.

56. Wan AKL, Seow WK, Walsh LJ, Bird PS. Comparison of five selective media for the growth and enumeration of Streptococcus mutans. Aust Dent J 2002; 47: 21-6.

57. Williams JR. The Declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2008; 85: 650-651.