Leading in the

Middle of Forced

Remote

How COVID-19 influenced the transformational

leadership dimensions of middle-managers

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Digital Business AUTHORS: Markus Holmström and Albin Lindsjö JÖNKÖPING May 2021

ii

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all interviewees who took their time to speak to us and provide this study with unique insights. We understand that these times are awfully hectic and challenging for all managers.

We would like to thank our supervisor, Jean-Charles Languilaire, for continuously providing us with support and constructive feedback through an open and sincere dialogue.

We would like to thank our families and loved ones. Without you, this study would have not been possible.

The process of writing this study has been incredibly different to what any of us could have imagined. We hope that this pandemic will conclude as soon as possible and that people stay healthy and safe.

Markus Holmström Albin Lindsjö May 23, 2021

iii

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Leading in the Middle of Forced Remote: How COVID-19 influenced the transformational leadership dimensions of middle-managers

Authors: Markus Holmström and Albin Lindsjö Tutor: Jean-Charles Languilaire

Date: 2021-05-23

Key terms: Transformational Leadership, Virtual Teams, Forced Change, Remote Leadership

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected organizations as they have been forced to move their operations from a physical space to a fully remote work environment. This rapid and forced digitalization puts pressure on organizations and their leaders to guide them through these uncertain times. Middle-managers have been seen as a vital link between the top and lower level of the organization, and through utilizing transformational leadership, adaptations to rapid changes might be less disruptive for followers and the organization. However, COVID-19 has resulted in an unprecedented situation which has caught the middle-manager in the middle of turbulent organizational change.

Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to interpret middle-managers’ adaptation to the forced change from a physical working environment towards a fully remote one from a managerial perspective with the transformational leadership dimension.

Method: To address the purpose of this study, a qualitative research design was used, and data was collected through three semi-structured interviews.

Conclusion: This study found that three major adaptations were made by middle-managers in response to the forced relocation to remote. These three adaptations influenced three

dimensions of transformational leadership who has received increased attention following forced remote which puts pressure on the middle-manager to address these dimensions while adhering to the new contextual circumstances.

iv

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem discussion... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 42.

Literature review ... 5

2.1 Transformational leadership ... 52.2 Virtual teams & remote leadership ... 9

3.

Methodology and method... 14

3.1 Methodology ...14

3.1.1 Research philosophy ...14

3.1.2 Research approach ...15

3.1.3 Research design ...15

3.2 Literature review process ...16

3.3 Method ...19

3.3.1 Data collection ...19

3.3.2 Sampling strategy...20

3.3.3 Interview design...21

3.4 Data analysis ...22

3.5 Ethical considerations and quality ...25

4.

Findings and Analysis ... 28

4.1 Contextual leader components ...28

4.1.1 Collaborative problem-solving process ...28

4.1.1.1 Internal structuring of organization ... 28

4.1.1.2 Managerial facilitation ... 28

4.1.2 Leader-follower interaction ...30

4.1.2.1 Development of followers ... 30

4.1.2.2 Follower motivation ... 31

4.1.2.3 Trust in followers ... 31

4.1.2.4 Visions and goals ... 32

4.1.3 Transformational leadership ...33

v

4.2.1 Challenges that arose due to COVID ...36

4.2.1.1 Communication ... 36

4.2.1.2 Follower well-being... 36

4.2.1.3 Physical presence ... 37

4.2.2 Adaptations in response to COVID ...37

4.2.2.1 Applied digital environment ... 37

4.2.2.2 Follower support ... 38

4.2.2.3 Meeting frequency... 38

4.2.2.4 Restructure of daily operations ... 39

4.2.3 Outcomes of adaptations to COVID ...39

4.2.3.1 Accessibility ... 39 4.2.3.2 Electronic dependability ... 40 4.2.3.3 Flexibility ... 40 4.2.3.4 Follower empowerment ... 41 4.2.3.5 Work structure ... 42 4.2.3.6 Work-life balance ... 43

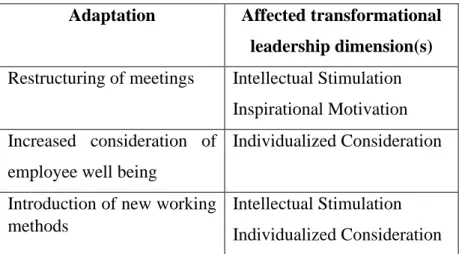

4.2.4 Interpretation of adaptations following forced remote ...45

4.2.5 Influence on transformational leadership dimensions ...48

5.

Conclusion ... 51

5.1 Discussion & theoretical contribution ...52

5.2 Implications ...54

5.2.1 Managerial ...54

5.2.2 Organizational ...54

5.2.3 Societal/Ethical ...55

5.3 Limitations and suggestions for future research ...55

vi

List of Tables

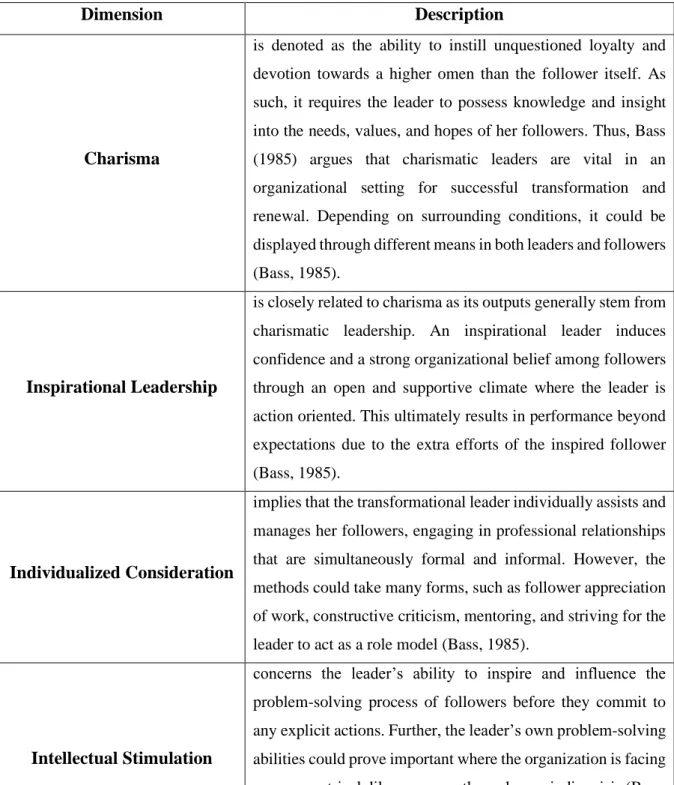

Table 1: Transformational leadership dimensions according to Bass (1985) ... 6

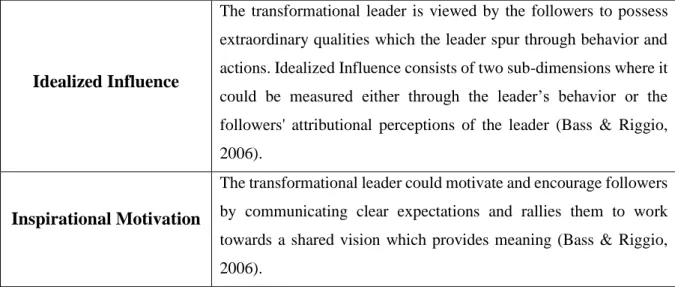

Table 2: Refined definitions of the transformational leadership dimensions from Bass and Riggio (2006) ... 7

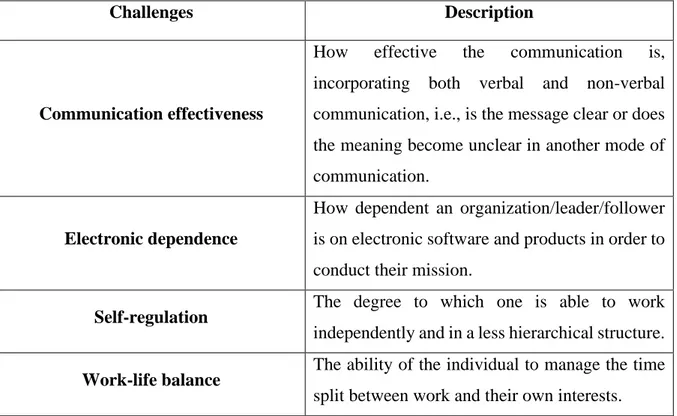

Table 3: The main challenges found in literature that we deem relevant to our study. ... 11

Table 4: Details of the search parameters and number of articles used based on it ... 17

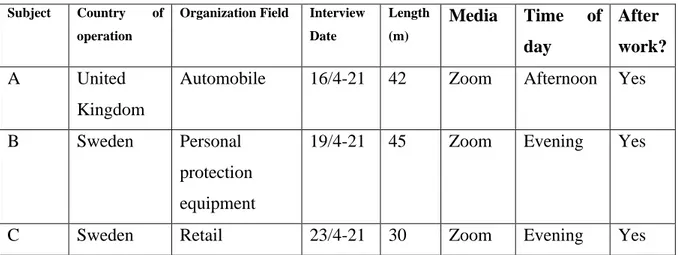

Table 5: Interview details ... 20

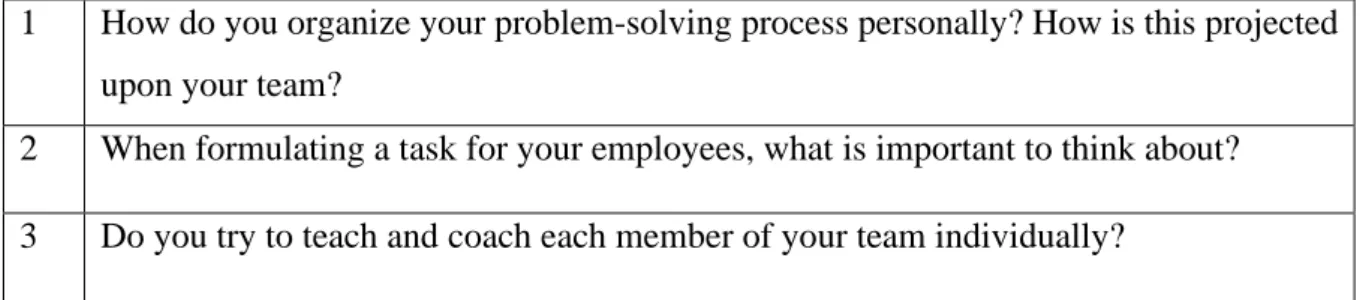

Table 6: Interview Guide ... 21

Table 7: The influence of adaptations on transformational leadership dimensions ... 48

List of Figures

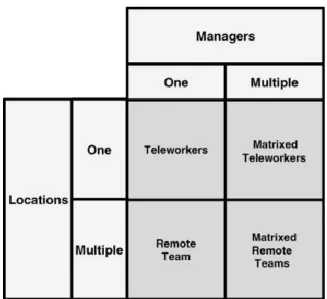

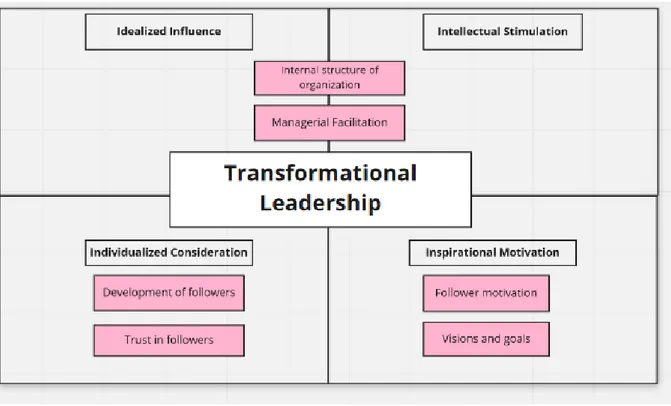

Figure 1: Forms of Virtual Teams from Cascio & Shurygailo (2003) ... 10Figure 2: Contextual leader components ... 24

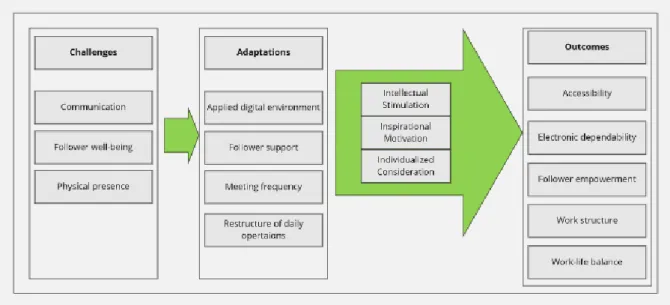

Figure 3: Implications of forced transition ... 25

Figure 4: Contextual leader components within the transformational leadership dimensions ... 33

Figure 5: Interpretation of adaptations ... 45

1

1. Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter introduces the disruptive powers of COVID-19 and the implications on organizations. Further, the importance of leadership among middle-managers during these circumstances is highlighted. Lastly, the purpose and research question are stated.

___________________________________________________________________________ 1.1 Background

Like the financial crisis in 2008, which brought large-scale changes such as the so-called Dodd-Frank Act (Hayes, 2021) and the efforts taken by the European Union (Geoff & Morgan, n.d.), the World was presented with an extraordinary situation following the global outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 and in early 2021, over 100 million cases worldwide have been confirmed (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). In a memo from November 2020, the Swedish Riksbank considered the COVID-19 pandemic to be one of the most extensive crises of all time (Cella, 2020). As of June 2020, the World Bank (2020) estimated that the global economy would sink by 5.2%, similar to that during the post-World War II recession, further speculating that the blow is expected to be hardest towards countries that rely on sectors such as tourism, global trade and external financing. The changes to business operations are on an unprecedented scale and it is likely that things will never return completely to how they were before (Deloitte, 2020). As a result of the new environment, organizations find themselves in a new position where new skills are needed to handle the new “normal” (Bajarin, 2021). Further, the sentiment towards remote work has swung immensely since the outbreak of the pandemic where a recent survey carried out by Gartner (Driscoll, 2020) found that 47% of managers were positive to allowing full time remote work and 43% of managers were positive to having their employees work part time from a remote location. As the pandemic has swept the world, with it, massive changes have been forced upon all parts of society.

Caught as one of the actors in the middle of this crisis, organizations have been faced with uncertainty and new considerations. Perhaps the most disruptive and rapid change witnessed has been the enforcement of utilizing digital platforms remotely to conduct daily operations rather than co-working within a digital environment from a physical space (Deloitte, 2020). Further, this has been a worldwide phenomenon and in the late summer of 2020, it was found by a global survey that over a third of knowledge workers were working from home (Slack, 2020). While the idea and execution of remote collaboration has become increasingly common

2

in the last decade, the ongoing development is unprecedented in terms of the full degree of virtual intrateam operations and collaboration (BDO, 2020). More specifically, rather than a natural, carefully planned digital transformation over time, it could be seen as a rapid and forced digitalization for businesses. As teams migrate from the physical environment to a full digital space there has been a call for leaders to guide the organization and its employees through these transitional and uncertain times (Ingram, 2020). Thus, leaders’abilities to boost team morale and to communicate in a transparent and focused way are more important than ever (Accenture, 2020).

1.2 Problem discussion

Taking a closer look into the organizational hierarchy, we find the middle-manager who operates beneath the top management and bears responsibility of the operational core, i.e., those further down the structure (Harding et al., 2014). Considered agents of organizational change and likened to being sandwiched in the middle, middle-managers create a vital link between the higher and lower parts of the organization (Gjerde & Alvesson, 2020). The importance of middle-managers has been highlighted in research due to their ability to influence strategic change in organizations (Rouleau & Balogun, 2011; Heyden et al., 2017), but also of their ability to strengthen the sense of community among employees (Mintzberg, 2009) and to act as a protector of subordinates (Gjerde & Alvesson, 2020). It could be assumed that pre-established teams formed within a physical perspective carry existing experiences, leadership, and relationships with them into this new stage of a complete virtual environment. As such, rather than enabling geographically dispersed work, it could at this time be argued that the utmost importance lies within the internal communication and performance of the predefined team which is guided by its middle-manager who leads followers while acting as a link between the top and bottom of the organizational structure.

While leadership is crucial for any organization under any circumstances it stands to reason that in times of rapid change, appropriate leadership is increasingly vital for organizations compared to normal operations in order to face transformational challenges (Northouse, 2019), it is especially so in virtual team environments were the tolerance for ineffective leadership is reduced (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). Although technological advancements have enabled organizations to conduct their operations with any one at any time independent of their affiliation, the changing circumstances have challenged the ways of traditional leadership

3

practices through traditional mediums (Van Wart et al., 2019). Leaders throughout different levels of an organization might differ in their approach of leading their followers, albeit one approach that has gained traction in literature and in practice is the leadership style of transformational leadership (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transformational leadership occurs when leaders manage to broaden and elevate the interests of their employees as well as achieve a “greater than I” feeling within the group which makes everyone look towards the good of the group rather than themselves (Bass, 1990). In his book from 1985, Bass constructs four dimensions that measures transformational leadership through the leader’s abilities to inspire, motivate, and show consideration for the followers. Bass (1985) further argues that transformational leaders drive change and could potentially be fit to lead their organization through crises. However, contingency theory within leadership states that challenges occur from the specific internal and external conditions that emerge during changing circumstances and as such, it puts greater pressure on leaders within the organization to be contingent and flexible amid such times (Northouse, 2019). Hence, during times of forced and rapid change it could be assumed that the pressure on leaders to be adaptive is greater than during gradual change, leaving the leader with several choices in a veil of uncertainty on how to progress. Thus, the aforementioned dilemma of responding to multifaceted challenges could subsequently be expected to put greater pressure on all managers throughout the organizational structure and their role of leadership overall but the adaptations could potentially be helped by a transformational leader.

Overall, it could be assumed that existing research could not adhere to the drastic events following the COVID-19 outbreak and simply applying our previous knowledge to today’s problem would not fully address it as it would not build on the circumstances we currently are presented with. Within these turbulent situations of organizational change, the middle-managers have most likely been caught in the middle of this process of rapid change due to them being the link between the top management and operational core. Additionally, due to the global shift of work environment, the followers have begun to rethink how work can be performed and their standing on remote work as it is no longer optional but integral (Slack, 2020). Thus, remote digital work is becoming the new normal (Bajarin, 2021) as a result of these abnormal circumstances meaning that leaders need to adapt to an unprecedented tomorrow.

4 1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to interpret middle-managers’ adaptation to the forced change from a physical working environment towards a fully remote one from a managerial perspective with the transformational leadership dimension.

RQ: How has the forced transition from a physical to a fully remote working environment influenced the transformational leadership dimensions of middle-level managers?

5

2. Literature review

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter presents the theoretical background of this study. First, a historical overview of transformational leadership and how it has evolved over the years is made. This is then followed by implications of transformational leadership research and where research within this topic is today. Second, the meaning of virtual teams and remote leadership is established. This is followed by the identification of challenges that virtual teams face which are drawn from previous literature.

___________________________________________________________________________ 2.1 Transformational leadership

The notion of transformational leadership has been developing throughout the years with the initial ideas taking form in the mid-80s. In response to recent developments within leadership theory in 1985, Bass found that the understanding of leadership needed increased depth as it failed to explain observed phenomena. As such, Bass (1985) set aim to further develop two emergent and distinct types of leadership, namely transactional and transformational leadership.

Instead of viewing the leader-follower relationship as a superficial exchange, Bass (1985) suggests that transformational leaders elevate those around through different aspects that subsequently motivates the follower to exceed expectations in terms of performance, further describing how transformational leaders display seven characteristics, stating that a transformational leader acts with integrity and kindness whilst setting clear goals for both the

individual and the team. They encourage followers while providing support and raising their moral and motivation but also guide individuals away from self-interest and instead towards selflessness. Lastly, transformational leaders inspire to strive for the improbable.

Following multiple studies and observations, Bass (1985) found that the level of transformational leadership could be defined using four dimensions: charisma, inspirational leadership, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation.

6

Table 1: Transformational leadership dimensions according to Bass (1985)

Dimension Description

Charisma

is denoted as the ability to instill unquestioned loyalty and devotion towards a higher omen than the follower itself. As such, it requires the leader to possess knowledge and insight into the needs, values, and hopes of her followers. Thus, Bass (1985) argues that charismatic leaders are vital in an organizational setting for successful transformation and renewal. Depending on surrounding conditions, it could be displayed through different means in both leaders and followers (Bass, 1985).

Inspirational Leadership

is closely related to charisma as its outputs generally stem from charismatic leadership. An inspirational leader induces confidence and a strong organizational belief among followers through an open and supportive climate where the leader is action oriented. This ultimately results in performance beyond expectations due to the extra efforts of the inspired follower (Bass, 1985).

Individualized Consideration

implies that the transformational leader individually assists and manages her followers, engaging in professional relationships that are simultaneously formal and informal. However, the methods could take many forms, such as follower appreciation of work, constructive criticism, mentoring, and striving for the leader to act as a role model (Bass, 1985).

Intellectual Stimulation

concerns the leader’s ability to inspire and influence the problem-solving process of followers before they commit to any explicit actions. Further, the leader’s own problem-solving abilities could prove important where the organization is facing an asymmetrical dilemma, e.g., through a periodic crisis (Bass, 1985). This could be done existentially and idealistic rather than through rationalistic and empirical methods.

Although that transformational leadership should be seen as important, Bass (1985) states that differing external and internal circumstances could influence the implementation and effectiveness of transformational leadership. Leaders operate in an organizational structure that

7

guide its technical concerns, albeit transformational leaders challenge the status quo by driving change of underlying conceptions and norms (Bass, 1985).

In a response to measure the aforementioned dimensions of leadership (Table 1), frameworks have been developed where the most recognized is the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire [MLQ] which subsequently assesses the so-called Full Range of Leadership [FRL] model that incorporates three types of leadership: laissez-faire, transactional, and transformational (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Originally derived from what was perceived to compose a certain leadership style, initial studies used 73 ratable behavioral statements that either could be used to rate one’s immediate superior or to assess oneself, albeit Bass and Riggio (2006) acknowledge that the latter method could be subject to bias. Results from these studies spawned the proposed four dimensions of transformational leadership previously mentioned (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

Since its publication, Bass’ (1985) idea of transformational leadership, both the MLQ and the dimensions has undergone changes (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Although that Individualized Consideration and Intellectual Stimulation have remained largely intact, Charisma, which has been renamed to Idealized Influence, and Inspirational Leadership, which has been renamed to Inspirational Motivation, have received a higher degree of conceptualization as the underlying measurements of transformational leadership have been refined (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

Table 2: Refined definitions of the transformational leadership dimensions from Bass and Riggio (2006)

Idealized Influence

The transformational leader is viewed by the followers to possess extraordinary qualities which the leader spur through behavior and actions. Idealized Influence consists of two sub-dimensions where it could be measured either through the leader’s behavior or the followers' attributional perceptions of the leader (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

Inspirational Motivation

The transformational leader could motivate and encourage followers by communicating clear expectations and rallies them to work towards a shared vision which provides meaning (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

8

Similarly, the MLQ has seen revisions throughout the years after receiving criticism for being too broad in its approach and measurement, thus the current form MLQ (5X) contains four items that assess nine different leadership styles on the FRL, totaling 36 items overall (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

Following the development of a tangible method of measurement, transformational leadership became an increasingly popular topic within research and as such, there has been numerous studies conducted surrounding transformational leadership (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Taking this into account, Bass and Riggio (2006) argue that evidence gathered from research throughout the years have displayed that the MLQ and subsequently the transformational leadership dimensions enjoy both reliability and validity through consistency. Furthermore, it is argued that the abundance of research and their results throughout the years suggests that transformational leadership is an effective method of leadership that could have a positive effect on followers' commitment, loyalty, satisfaction, and overall performance (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Research also suggests that it is the method which subordinates tend to associate with perceived leadership performance (Neufeld et al., 2010) and a key characteristic of transformational leaders is the focus on long-term over the short-term (Dubinsky et al., 1995). Contrastingly, the lack of an understanding or application of transformational leadership within the field of business could result in a decrease of employee satisfaction and productivity, which eventually could negatively influence the complete organization (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

Despite the widespread acclaim of transformational leadership, critics have questioned whether transformational leadership deserves its status and how future research should be conducted. In their paper, van Knippenberg and Sitkin (2013) argue that the research within transformational leadership has grown to such an extent where its borders have become ambiguous which subsequently negatively influences the methods constructed from the underlying assumptions and foundational aspects of transformational leadership. Hence, in order to produce meaningful future literature, it is suggested that researchers do not restrain themselves to strictly adhere to the transformational leadership dimensions but to utilize a larger perspective when drawing conclusions (van Knippenberg and Sitkin, 2013). In a similar manner, Batistič et al. (2017) argue that transformational leadership should be viewed as a multi-level phenomenon that incorporates several factors, albeit the forces under investigation often get attributed to transformational leadership without further analysis as the current norm

9

of level of analysis allows for it. In essence, criticism is not pointed towards the core concepts of transformational leadership themselves but rather the vague conceptualizations within research and subsequently the analysis that it builds upon as it opens for monotonous interpretations (van Knippenberg and Sitkin, 2013).

Nevertheless, the aforementioned sharp increase in research on transformational leadership has resulted in studies being conducted in several fields and applications within varying contexts and settings such as education and group performance within organizations across sectors (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Dumdum et al., 2013; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013; Gardner et al., 2020). This popularity has continued and studies that build upon transformational leadership theories remains one of the most studied topics within leadership (Gardner et al., 2020). However, research that delves into technology’s impact on leadership has been denoted as an area in need of further research as it has largely been a neglected area but also because of the ongoing trend where teams migrate to digital platforms for work which places a higher importance on leadership during such circumstances (Gardner et al., 2020). This is supported by Wong and Nordengen Berntzen (2019) who found that the effectiveness of transformational leadership could be lessened in distributed teams that rely on digital platforms and calls for future research that investigates methods of overcoming this issue. Similarly, Eisenberg et al. (2019) suggest that while transformational leadership is effective in teams where dispersion is low, the positive effect of transformational leadership diminishes as dispersion increases.

2.2 Virtual teams & remote leadership

Virtual teams have over the years been defined in similar but not identical ways often with modest distinctions between them. Already in 2003, Cascio & Shurygailo differentiated between two variables: managers and locations as seen in Figure 1. Then in 2004, Hansen defined virtual teams to consist of three requirements, it has to be a functioning team consisting of a collection of individuals which through varying degrees of interdependence and accountability work together with the goal of achieving a mutual objective. Second, the members of these teams must be dispersed in certain ways. Thirdly, the team members primarily rely on technology to connect and communicate with each other. Additionally, virtual teams tend to be made up of individuals which have little to no shared work history with one another and are therefore very diverse as far as the culture, norms and expertise goes, making them less reliant on functional, organizational and geographic limitations (Maruping &

10

Agarwal, 2004). Lastly, in 2017, Dulebohn and Hoch defined it as arrangements that exists at work in which team members are geographically dispersed, with limited face-to-face contact and where the team members work independently of one another through the use of electronic communication media.

For the purposes of this thesis, we define virtual teams as a group of individuals that are

geographically dispersed which utilize electronic communication and technology to achieve a common objective.

The use of virtual teams and remote work has been increasing for a long time (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003; Gibson & Gibbs, 2006; Neufeld et al., 2010; Sull et al., 2020) and with the continued development of information technology along with the increased competition following globalization (Kirkman et al., 2002; Algesheimer et al., 2011), more businesses are transferring over towards a digital environment in order to ensure that they obtain the expertise that is needed (Maruping & Agarwal, 2004; Malhora et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2019). While virtual teams can bring with it benefits and increase satisfaction to both workers and employers, the switch to a remote working environment can also bring with it increased difficulties for the employees when it comes the work-life balance (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003; Liao, 2017). Teams in the digital environment are faced with challenges which differ from those employees are accustomed to in the physical environment (Van Wart et al., 2019). Based on the reviewed literature, we ascertain that the biggest challenges that are relevant to our research are the

Figure 1: Forms of Virtual Teams from Cascio & Shurygailo (2003)

11

following: Communication effectiveness, Electronic dependence, Self-regulation and Work-life balance.

Table 3: The main challenges found in literature that we deem relevant to our study.

Challenges Description

Communication effectiveness

How effective the communication is, incorporating both verbal and non-verbal communication, i.e., is the message clear or does the meaning become unclear in another mode of communication.

Electronic dependence

How dependent an organization/leader/follower is on electronic software and products in order to conduct their mission.

Self-regulation The degree to which one is able to work

independently and in a less hierarchical structure.

Work-life balance The ability of the individual to manage the time

split between work and their own interests.

As mentioned above, the challenges middle-managers face when working in a virtual environment are varied and cover a broad range of areas, among others it includes how involved a manager should be in the workers tasks. In virtual teams, team member performance has been found to increase the higher the freedom to self-regulate compared to when the manager takes a more involved role in tasks (Kozlovski et al., 1996). Allowing the employees to self-regulate and to abstain from interfering unless necessary also has the added benefit of signalling trust from the manager towards the employees, a factor which Bijlsma and van de Bunt (2003) emphasized as a key component in remote work. Another factor which have been linked to employee dissatisfaction when operating in a virtual and/or remote environment stems from the lack of physical face-to-face interaction between colleagues and here the manager plays a crucial role in mitigating such issues (Kirkman et al., 2002) If employees are forced to work remotely for a prolonged period and managers do not place great emphasis on preventing the sense of isolation amongst the employees, the employees might start to feel invisible and dissatisfied which could further diminish their performance (Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011;

12

Kirkman et al., 2002). Therefore, the leaders must strike a balance between how involved they are and to which degree to allow the team members to operate with greater leeway than in traditional environments. Additionally, the leadership in virtual teams have been proved to benefit when it is shared between the team members (Hoegl & Muethel, 2016).

Virtual teams often cross more nationality- (Gibson & Gibs, 2006) and cultural boundaries than physical teams do, hence, they are much more susceptible to conflicts related to such factors than teams that work together from a physical location (Maruping & Agarwal, 2004). As a consequence of the nature in which virtual teams operate, the members will, contrary to conventional teams who often learn to collaborate over dinner and drinks, they must learn it through electronic measures (Malhotra et al., 2007).

Apart from virtual teams working remotely, they are often characterised by a greater geographical dispersion (Gibson & Gibs, 2006), often spanning multiple time zones, as a result it is a potential for some individuals to “draw the short stick” and be forced to conduct meetings at inopportune times and thus feel overseen or less valued by the management (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). The rotating of meeting times in geographically dispersed teams have been linked to be a catalyst for trust building in the teams (Malhotra et al., 2007). Further, the very nature of working remotely causes problems when managers are trying to encourage and identify new leaders (Cascio & Shurygailo 2003). Just like in physical face to face meetings, people get a first impression in virtual environments which may prove difficult to alter later, even when faced with evidence to the contrary (Zigurs, 2003). Due to the nature of their working environment, virtual teams can often be more reliant on electronics than traditional teams.

The level of electronic dependence which the virtual teams are experiencing can have a significant impact on the performance of the team (Gibson & Gibs, 2006), electronic dependence being the degree to which an organization, group, individual etc. is dependent on electronic devices and functions. Communication effectiveness have also been found to be a crucial element and it can have the potential to limit the effect that physical distance has on communication effectiveness and perceived leader performance (Neufeld et al., 2010). Used proficiently, electronic communication means can serve as an equalizer, promoting the free flow of ideas and opinions from all team members (Balthazard et al., 2009). It is crucial that

13

leaders take consideration to what platforms and media is used for their virtual teams as which platforms that are used can benefit positive communication (Kahai et al., 2012). Additionally, in a digital environment, followers are more inclined to trust the remote leaders if the leader is media savvy (Norman et al., 2019).

14

3. Methodology and method

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter contains two parts. In the first part, the methodological choices of this study are presented in terms of philosophy, approach and design. In the second part, the method of data collection and analysis is elaborated in detail. This concludes with the ethical considerations and quality of this study.

___________________________________________________________________________ 3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research philosophy

In order to conduct research that strives to be seen as one of quality, the underlying philosophical assumptions of the research should be given thought and consideration. Although seen as the least visible element of the research process, the research philosophy, which contains the ontology and epistemology, is critical for research projects since it gathers the foundational philosophical assumptions of the research (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

What is often considered the starting point of research philosophy is the ontology which is the researcher’s basic assumption of the nature of reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Going back to the research question and purpose, there might be varying ways that middle-managers have adapted to a forced change of working remotely, thus it is our assumption that actions and outcomes draw from several perspectives that address the contextual circumstances since it is likely that each individual draw from their unique perspective to interpret and respond to the situation at hand. Furthermore, research on transformational leadership has been receiving critique for rendering myopic conclusions that fail to recognize potentially influential aspects other than transformational leadership itself as stated in the literature review (van Knippenberg and Sitkin, 2013) and assuming that the nature of reality would contain universal answers for phenomena would render our research vulnerable to likewise critique. Drawing from these aforementioned assumptions, the ontology of this research follows a relativistic view.

The other fundamental philosophical position is the epistemology which concerns the methods of enquiring into the physical and social world and the nature of knowledge (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Additionally, epistemology refers to what is to be seen as acceptable, valid, and legitimate knowledge (Saunders et al., 2019). In social sciences, two main paradigms with contrasting views have emerged, namely positivism and interpretivism (Easterby-Smith et al.,

15

2018). Given our relativistic ontology, where reality is considered multiple and subjective, an interpretivist epistemology is deemed the most suitable for this research since interpretivism assumes that knowledge is generated through the subjective views of the participants (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Furthermore, we believe that the purpose of this research, i.e., the interpretation of middle-managers’ adaptation to a contextual anomaly would be the most effectively addressed through interpretivism as it aims to create deeper understandings and interpretations of contexts which is in line with Saunders et al. (2019).

3.1.2 Research approach

Building on the philosophy, the research approach concerns the role of theory (Saunders et al., 2019) and the underlying logic of the research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In an inductive research approach, theory is derived from the data collection through subjective interpretations where the context in which events occur is emphasized (Saunders et al., 2019). As such, an inductive approach is connected to an interpretivist epistemology due to their similar importance placed on subjective interpretations (Saunders et al., 2019).

In our Introduction, we conclude that the circumstances regarding remote work have experienced a change following the COVID-19 pandemic, albeit we do not draw any further conclusions on the effects it has had on the transformational leadership dimensions. Instead, the focus of our research is to interpret the context, i.e., the forced transition from physical to remote, which we hope could contribute to existing theories within leadership. Lastly, an inductive approach could benefit to a greater degree from smaller sample sizes than other research approaches (Saunders et al., 2019) and given these trying times, it could be assumed that it is considerably more difficult to incorporate participants. Hence, this research is subsequently deemed to favorably follow an inductive approach.

3.1.3 Research design

In order to address the purpose of this research while adhering to the aforementioned philosophies and approach, a qualitative research design is deemed the most suitable since it allows us to gather empirical data that builds on the subjective meanings of participants (Saunders et al., 2019). Although that some aspects of transformational leadership could be seen as quantitative in nature, namely the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Bass & Riggio, 2006), a mixed methods research design was deemed not feasible given our timeframe.

16

Further dissecting our purpose, it is not in the scope of this research to investigate the underlying explanations to the reasoning of our participants but rather to further gain knowledge of the impact on a phenomenon brought by the circumstances. Given that our purpose incorporates the particular problem of forced remote work with middle-managers and transformational leadership, it draws up clearer entities than could be assumed if we were to conduct exploratory research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Furthermore, previous theoretical contributions that address transformational leadership and technology exist (Gardner et al., 2020) but could not have predicted the recent and rapid contextual changes. Thus, this research could be classified as descriptive research.

Lastly, in pursuit of addressing our research question with respect to our methodology, this study will follow a single-case study design. In this research, the context of forced remote work and the case of middle-managers' views is not only fundamental but also the result of extraordinary circumstances that were previously inaccessible which adheres to one of the rationales for using a single-case design (Yin, 2018). Furthermore, our previous notions of context and middle-managers leads us to utilize an embedded case study design where the interviewees are seen as multiple units of analysis, operating within a similar context. However, a common pitfall for the embedded design could be that the level of analysis becomes too narrow and fails to focus on the bigger picture (Yin, 2018), albeit a similar issue was raised in the literature review (van Knippenberg and Sitkin, 2013), and as such is a highlighted and important consideration for us in the later stages of this research. Additionally, another pitfall that could hamper the overall application of a single-case study is that eventually the case could significantly deviate from what was initially presumed (Yin, 2018). Thus, we strive to thoroughly investigate the case before taking further steps in the process.

3.2 Literature review process

Initial contact with literature was established through a previous course named “Leading and Organizing Innovation Work” at Jönköping International Business School. This course introduced several leadership theories, one of which was transformational leadership through the article “From Transactional to Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the Vision” by Bass in 1990. This article evoked an interest in the topic and inspired the authors to further investigate transformational leadership. Thus, to utilize an inductive approach and to understand the context in which our data lies, a literature review was conducted to establish a

17

preunderstanding of the topic. Given the relative vastness of previous literature, as seen by “Hits” in Table 4, a traditional literature review was conducted as a bounded area of research was discussed which is in line with Easterby-Smith et al. (2018).

While conducting our search for relevant literature we agreed that it would be beneficial to keep a separate document (excel file) were we could write down any comments and/or notes that we have on each article that we use as this would be beneficial for us later and to allow for better overview of the articles (Saunders et al., 2019). In this file we also noted what search terms had been used to find the article along with which database the search was done in along with the number of hits it received. Further, when initially going through the articles chosen, we decided to only incorporate articles that was published in journals that were presented on the 2018 ABS list. Further, we also made use of articles which we have come across in earlier courses. Additionally, we utilized the software ´Mendeley´ for easier access to the articles between the two authors and to aid in generating a reference list. In several instances, when we found parts of the articles which seemed to be more relevant than others or intrigued us, we would then go on to read the references that said article contained.

The articles chosen for the literature review stemmed from the following searches,

Table 4: Details of the search parameters and number of articles used based on it

Search words Filters Hits Database Articles

used based on search Virtual leadership Articles, English, 2000-, 2,485 Primo 2

Remote Work Virtual leadership, Remote leadership, transformatio

18 nal, English, articles Business Middle Manager * Importance 142,160 Primo 4 Virtual leadership & challenger OR remote leadership & challenges Articles, English, leadership, SAGE complete A-Z list, management, 2010-2021 101 Primo 6 Transformation al leadership, Electronic dependence 1,116 primo 1 Transformation al Leadership, English, articles 85,718 Primo 1 Remote work, Transformation al leadership, English, articles 261 Primo 1 Transformation al leadership four dimensions 17,375 Primo 5 Virtual leadership, remote work English, articles 15,762 Primo 1 remote leadership articles, English, 2010-2021, leadership, 215 Primo 1

19 Business & economics Leading Virtual Teams Articles, English, 2005-2021 77,012 Primo 1 Remote work, MIT Articles, English 45,591 Primo 2 Virtual Leadership, Remote Leadership Articles, English 17,075 Primo 1 Virtual Teams, management Articles, English 75,516 Primo 1 3.3 Method 3.3.1 Data collection

Given the relativistic view of this research and our objective to obtain a deeper understanding of the effects that the forced digital change has had on leaders, we made use of semi-structured interviews. It was deemed that by gathering data in this way it would allow participants to share and evaluate their actions through their own perception without direct or even leading interjections from the researchers. Additionally, it was our goal that the respondents would experience a freer and less restrictive environment to explain their answers while at the same time having some commonality between all the interviews.

Extra effort was put into accommodating the participants in terms of the digital communication media used and at which time the interviews was done, thereby making the participants more at ease. Additionally, to further make the participants comfortable they were given prior information about which areas (leadership, working remotely) we were to cover during the interview, although they did not get the exact interview questions beforehand. The reason for doing so was that we wanted to reduce the possibility of pre-constructed answers so that it would be more of a natural and informal conversation.

20

After obtaining the permission of our participants, all of the interviews were audio recorded and a couple were video recorded so that we would have the ability to go back at a later date and observe it again as well as to allow for the transcription in full. However, as some did not wish to appear on video, or it was impractical given the environment which they were in at the time only audio recordings were made during such circumstances. Additionally, the notes taken by both authors were compared after each interview. Through these steps we strived to ensure that the data collected was reliable and that our empirical data would hold a higher quality.

While face-to-face interviews would otherwise have been our preferred method to conduct the interviews, the decision to conduct internet-mediated interviews were made because of the times we currently live in with an active pandemic where we are trying to limit our physical exposure to other persons.

Table 5: Interview details

Subject Country of operation

Organization Field Interview Date Length (m) Media Time of day After work? A United Kingdom

Automobile 16/4-21 42 Zoom Afternoon Yes

B Sweden Personal

protection equipment

19/4-21 45 Zoom Evening Yes

C Sweden Retail 23/4-21 30 Zoom Evening Yes

3.3.2 Sampling strategy

The requirements of what would qualify a participant for this study were established early and the target population could be implicitly found in our purpose. Therefore, non-probability sampling was used in the form of purposive sampling. In order to be considered, the participant needed to currently occupy a middle-manager position in an organization where, due to COVID-19, the manager’s team has been forced to transition from working together in a physical space to conducting all work completely remotely. As such, a homogeneous sampling technique was used since the members of the sample possessed similar characteristics in the form of a particular level within the organizational structure which in synergy with the

21

qualitative nature of this research could allow for a deeper investigation of the subjects (Saunders et al., 2019).

Due to the circumstances surrounding COVID-19, it was seen as likely that middle-managers who did not know the authors on some personal level from before would be unable to make time for an interview. Hence, initial contact with potential subjects was primarily made through pre-existing connections and channels with an audience where neither author was completely unknown. Additionally, efforts were made through online communications to attract subjects who lacked any former social contact with either authors.

An issue that was given consideration was that the subject’s official title within the company might not explicitly contain the term “middle-manager". As such, the responsibilities and internal position were scrutinized in initial communications to ensure that the subject possessed the necessary characteristics of operating beneath the top management while bearing some form of responsibility over the operational core, as mentioned in the Problem discussion.

3.3.3 Interview design

In order to address the purpose and to develop an understanding of the context in which our interviewees were operating, 11 questions were put forth. The inspiration for formulating these questions was taken from the identified literature in the Literature Review. Since the MLQ 5X was identified to be a quantitative tool for assessing the degree of transformational leadership present, this tool had to be adapted so that we could utilize it in a qualitative manner. Hence, example sentences and examples that were originally drawn up by Bass and Riggio (2006) were adapted so that it would fit our research which can be seen in Question 1 to 5. Furthermore, extra care was taken so that the formulation of the questions was clear, that they were not leading and that it provided the interviewee an opportunity to provide a vivid explanation from his or her individual viewpoint.

Table 6: Interview Guide

1 How do you organize your problem-solving process personally? How is this projected upon your team?

2 When formulating a task for your employees, what is important to think about? 3 Do you try to teach and coach each member of your team individually?

22

4 Do you try to envision the near and/or far future for your employees? If so, how? 5 What do you think is important for your followers to take away from your interactions? 6 How has the pandemic changed the way in which your organization operates

internally?

7 How do the managers at your company motivate the employees now that you are working remotely?

8 How dependent are you and the company of electronic devices and functions? 9 Which medias does your team(s) use for communication?

How do you think it works to communicate in this way? Positives/Negatives.

10 Have you noticed a difference since switching to working remotely when it comes to your ability to handle the work-life balance?

If so, was it better or worse before switching to remote?

11 Do the tasks carried out by the team require a great deal of micromanagement? Less/more so than before?

3.4 Data analysis

Given our interpretivist philosophy where the subjective knowledge is important, it is imperative to find a suitable method that makes sense of complex and subjective data while considering the philosophical assumptions (Saunders et al., 2019). A method that is seen as flexible and foundational for analysis of qualitative data is thematic analysis which scans for themes across a data set (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This is done through coding the qualitative data that subsequently results in codes and themes that relates back to the research question (Saunders et al., 2019). Due to the relative broadness of definition regarding thematic analysis (Saunders et al., 2019), we adhere to the six guidelines of Braun and Clarke (2006) so that our process could be transparent and coherent.

The first phase is the familiarization of data, where the researchers immerse themselves with the data collected. This was done through three actions. Firstly, both researchers were

23

present when possible and took personal notes for all interviews to generate prior insights of the data. Secondly, all interviews were transcribed. Lastly, the transcripts were shared between the researchers and readthrough individually before coding it.

For coding, we used the software NVivo, into which the transcripts were imported and initially, each author generated initial codes across the data individually to avoid influencing each other in an early stage that could potentially negatively influence subsequent analysis since this research is fuelled by the data gathered.

When the initial coding was done, the following steps in the thematic analysis was done and discussed together. First, the codes were compared between the authors and from that, a common standard was set and the search for themes begun.

After sorting the codes into potential themes, the themes were reviewed both internally, i.e., whether the codes within were related and externally, i.e., whether the themes together made sense across the dataset.

The themes were then defined and named so they were distinct but also made sense in the bigger picture of analysis.

Lastly extracts from each theme was put in the producing of the report.

In order to interpret how the adaptations made in response to the forced remote influenced the transformational leadership dimensions, our findings acted as a starting point and together with previous literature guided the analysis. From this it became clear that we had to address two points. First, we had to determine whether our participants are transformational leaders, or it would render subsequent findings and analysis moot. This was categorized as Contextual Leader Components.

24

Figure 2: Contextual leader components

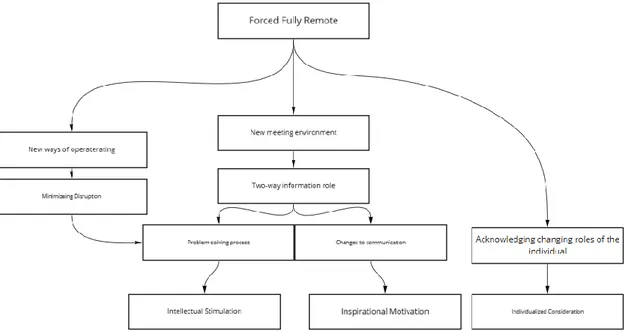

Second, to interpret the adaptations, we had to understand where they came from and what they resulted in, i.e., in which context did these adaptations happen? Gaining this perspective would further assist in determining which transformational leadership dimensions the adaptations influenced. This was categorized as Implications of forced transition.

25

Figure 3: Implications of forced transition

3.5 Ethical considerations and quality

As argued by Saunders et al., (2019, p.232), “Ethical concerns are greatest where research

involves human participants. In line with the four key principles brought forth by Bell &

Bryman (2013) we made sure to take whatever steps we could to mitigate any issues surrounding them. To prevent any harm from coming to the participants of our study, we took several steps. Mainly we focused on preventing anyone from being able to guess whom they

26

were by way of protecting the anonymity of the participants. For this reason, we aimed at giving as vague descriptions as possible of the companies operating sector and decided to not disclose the names of the respondent or the company they work for. Neither did we use titles or gender to describe any of them. To prevent any sensitive information being accessed by unauthorized individuals, all data was stored in a way in which only the authors would have access to it and as soon as was possible notes and recordings were destroyed. Up on initial contact with prospected participants, we made clear that they understood for what reason they were contacted, along with what topics we wanted to ask about as well as informing them of their right to anonymity and to withdraw their full or partial participation in the study at any point. We also took the time to answer any questions that the participants might have so as to be transparent and forthcoming to them. Additionally, we were also flexible in when the interviews were to be done, as we did not want them to feel stressed or limited in time, so as to not intrude on any other commitments that participants might have (Saunders et al., 2019). By doing this we hoped to treat the participants in a way in which we ourselves would have wanted to be treated if the roles were reversed. As neither of the authors had any conflicts of interest with any of the participants or their organizations, there was no conflict to disclose. By being forthcoming and answering any questions that our respondents had we hoped to prevent any sense of deception from their point of view.

According to Korstjens & Moser (2018), there are four quality criterions for all qualitative research: (1) credibility, (2) transferability, (3) dependability, (4) confirmability.

Credibility deals with whether confidence can be placed in the truthfulness of the findings (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). By giving the respondents full anonymity and by giving them advance knowledge of the subjects to be covered, along with the information that they could withdraw their participation at any time, we made sure that those who participated did so willingly. Through the use of anonymity, we hoped that the participants would feel safer to provide information and opinions without needing to fear reprisals or discontent from their colleagues. Additionally, by transcribing the interviews and discussing the notes we had between us we made sure that we were on the same page. To further ensure that the data gathered was interpreted correctly, we made use of respondent validation, whereby we provided each participant with the transcription of the interview that had previously been carried out with that participant. By doing so we strived to provide credibility to each

27

participant's account (Bryman & Bell, 2011) as well as to offer a chance for them to alter anything that was wrong, or they wanted to remove for any reason. Further, we made use of

persistent observation wherein we focused on the characteristics and elements that were the

most relevant to our purpose (Korstjens & Moser, 2018).

Transferability concerns itself with the degree to which the results can be transferred to other contexts or settings with other respondents (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). By providing a full description of the research questions and the design and context of them, along with the findings and interpretations we provide the reader with the means to determine the transferability of this study (Saunders et al., 2019). Therefore, we provide these factors in a number of ways, e.g., in Table 5, we cover information of the interviews and in Table 6 the reader can find the interview guide which served as the basis for all our interviews. Additionally, we give ample information about the process of coding the interviews.

To ensure dependability of our data, we chose to make use of stepwise replication (Lincoln & Guba, 1986), this was done through three steps: First, the two authors coded the 3 interviews separately. Second, the authors discussed the codes and themes that we had started to form, while doing so we also resolved and discrepancies between the two sets of codes we had generated. Third, we created a final set of codes that was then used to build the subsequent analysis.

Confirmability deals with the stability of the findings over a prolonged period of time and those said findings are not figments of the researcher's imagination but rather derived from data (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). To allow for others to better evaluate the research that have been done, we have thoroughly described the process surrounding how we generated, handled and analyzed the data. For instance, through Tables 4 and 6 the reader can clearly see how we went about gathering our data. Along with detailed descriptions of the steps taken for analyzing the gathered data, detailing how the coding and themes were used.

28

4. Findings and Analysis

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter presents the findings of the data collected in accordance with a thematic analysis and with regards to the research question. These themes are then analyzed through their connection with identified previous literature and the purpose of this study.

___________________________________________________________________________ We identified two main themes, ‘Contextual leader components’ and ‘Implications of forced transition’, these themes consist of a set of general categories. These general categories are in turn made up of several sub-categories.

4.1 Contextual leader components

4.1.1 Collaborative problem-solving process

4.1.1.1 Internal structuring of organization

It was expressed that the internal structuring of both the organization and the teams was seen as pivotal for the problem-solving process of the followers since the lack of a solid structure increases the likelihood that some members experience a greater level of insecurity regarding through the entire process:

“Those times I have led and not had an overall structure in place, then there are quite a

few who feel insecure and there will be a lot of questions” (Int 3).

As such, it is seen as important that the leader organize this process in a clear manner, providing the followers with clear goals to strive for as this facilitates them to work towards the same objective:

“[…] as soon as you are very clear with the goal, milestones, what are we going to

achieve, then everyone has it much easier to take initiative and run things on their own”

(Int 3)

4.1.1.2 Managerial facilitation

The actions from a managerial standpoint which are taken to support their employees can take several forms and an overarching idea was that the main responsibilities of the leader were to facilitate that the followers had the necessary resources and capabilities to complete the task they are working on in an efficient and timely manner:

“it's a lot about ensuring that we have resources for these projects by talking with

various function managers who own resources, but then also to lead the team on a daily basis and make sure we follow the timeline, we follow the processes that are set up,

29

checking in on everything, compile business cases, present business cases, makes sure we get "Go" on all the initiatives that we have to do” (Int 3)

“[...] make sure that the team can carry out what they want” (Int 3).

This could be manifested by how the leaders were setting up regular meetings through which they strived to encourage the free flow of ideas and to provide a forum for the discussion and exchanging of ideas:

“where we have people that have ideas, including me, who will come together and we

can discuss them to find a solution on a given problem.” (Int 1),

“if we get stuck on something that needs to be treated a little more thoroughly, we set up

an extra meeting for a specialized group and take in resources as needed” (Int 2).

Additionally, to make sure that the tasks were not too large and/or overwhelming, leaders would try to deconstruct and segment the tasks into smaller pieces which would be more easily approached:

“First it'll be how difficult a task is and how much we can split it down. For example, you

can say to someone "design this" but to design that, if you have to do multiple other bits, you know, you add to those bits as individual tasks, just to sort of break it down to easier, more manageable things” (Int 1)

To be able to deconstruct the tasks in a competent manner, it requires that the leader has a fundamental understanding of the problem at hand if they are to guide the followers along the way:

“it's a lot about understanding the problem, trying to break down the problem in smaller

components, then it takes to the right people or ball each component of the problem with the right person, let them come up with suggestions for solutions and then also let those who are experts and specialists get to implement the solution as they think and rather be a sounding board to them.” (Int 3).

Furthermore, if something was to go awry, supportive actions could be taken through an open dialogue, having a relationship where the followers are comfortable to give the leader a shout if there is something which hinders them from achieving their goal:

30

“An important thing is that they give me a shout if something prevents them from doing

the task they have, that they are open and say if there is something they do not think works or have not understood, that they do not understand their role in the context. Have an open dialogue with me” (Int 2).

Hence, managerial facilitation could be seen as listening to all parties involved, gaining a deeper understanding and the clearing of obstacles to help the followers fulfil their goals:

“clearing obstacles, listening, understanding and helping them do things.” (Int 3).

Overall, the middle-manager coordinates the process in tandem with the employees where they work together, and the leader pushes the followers forward by creating a supportive environment:

“we all try and work together, try and help them to sort of move forwards.” (Int 1) , “I'll

just create an environment there and make sure we get through” (Int 2) & “I'm there to support, enable or help them do that they think is right” (Int 3).

4.1.2 Leader-follower interaction

4.1.2.1 Development of followers

The individual development of the followers was addressed by the leader on two levels, namely the individual level and on a larger, more overall level through actions such as coaching, lectures and supportive actions:

“I definitely focus on coaching and supporting those who spend a lot of their time in the

project” (Int 3)

“We don't do individual coaching unless someone is really stuck. We try to have like lectures and lessons on different topics for different areas of the car” (Int 1).

It is up to the leader to effectively manage these interactions with respect to present constraints as it might not always be feasible to give all parties involved the same level of attention, as the time available for the leader is limited, the leader has to prioritize those followers that are overseen by the leader the greatest amount of time so as to ensure their continued growth:

“I will of course put much more focus on those who spend a lot of their working time [on the project], on coaching them and develop them than to put on those that are only in a few parts, because there is not enough time for me.” (Int 3)

31

“I strive to make everyone heard in any case so that we build a mutual respect in the

team and that everyone has a say and a challenge is to make sure that you move forward”

(Int 2).

4.1.2.2 Follower motivation

The leaders we spoke to emphasize the benefits that come from having a team that is informed of what is going on in other areas around them, with regular meetings taking place relatively often, where they can provide the followers with information which serve to display the overall picture of what the organization/department is trying to achieve. This is seen by the respondents as a way of motivating and provide purpose to the teams along with providing more opportunities for the leader to “check-in” on the followers:

“When we have team-wide meetings which tend to happen about once a month, we sort

of explain to them all the meetings we've had with the [top management] so far and what has come out of them” (Int 1).

“Because to them, they don't really see the behind-the-scenes stuff. I want to make sure that they understand what's happening throughout the team and to make sure that they are still motivated, that they enjoy doing what they do and that I'm also sort of like proud of the work that gets done” (Int 1)

“so an overall structure I would say is one of the most important things to work with in interactions or "check-in" meetings you have with both the group and individuals” (Int

3).

4.1.2.3 Trust in followers

None of the leaders we interviewed expressed any desire for micromanagement, instead all emphasized the importance of showing your followers that you trust in them and their abilities. Instead, the leaders relied more on setting up frameworks for their followers to work within, and as long as they did so they could act freely:

“within these frameworks I point out, there I leave very freely” (Int 3)

Given the complex nature of the tasks that the leaders interviewed oversee, it would be almost impossible for the leaders to be experts in all of the areas that are required to achieve the goals, instead they are typically generalists which then assemble teams that have the desired expertise. Thus, this makes it impractical to micromanage the members since they possess the expertise