DS

The Individual Development Plan

as Tool and Practice

in Swedish compulsory school

ÅSA HIRSH

School of Education and Communication Jönköping University Dissertation Series No. 20 • 2013

The Individual Development Plan

as Tool and Practice

in Swedish compulsory school

ÅSA HIRSH

Dissertation in Education

School of Education and Communication

Jönköping University

Dissertation Series No. 20• 2013

© Åsa Hirsh, 2013

School of Education and Communication Jönköping University

Box 1026

SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden www.hlk.hj.se

Title: The Individual Development Plan as Tool and Practice in Swe-dish compulsory school

Dissertation No. 20 Print: TMG Tabergs

ISBN: 978-91-628-8842-8

ABSTRACT Åsa Hirsh, 2013

Title: The Individual Development Plan as Tool and Practice in Swe-dish compulsory school

Language: English, with a summary in Swedish

Keywords: Individual development plan (IDP), individual education plan

(IEP), teachers‟ assessment practices, formative assessment, doc-umentation, gender, mediated action, tool, inscription/translation, primary/secondary/tertiary artifacts, mastery/appropriation, IDP practices, contradictions, dilemmas, national and local steering of schools

ISBN: 978-91-628-8842-8

Since 2006 Swedish compulsory school teachers are required to use individual development plans (IDPs) as part of their assessment practices. The IDP has developed through two major reforms and is currently about to undergo a third in which requirements for documentation are to be reduced. The original purpose of IDP was formative: a document containing targets and strategies for the student‟s future learning was to be drawn up at the parent-pupil-teacher meet-ing each semester. The 2008 reform added requirements for written summative assess-ments/grade-like symbols to be used in the plan.

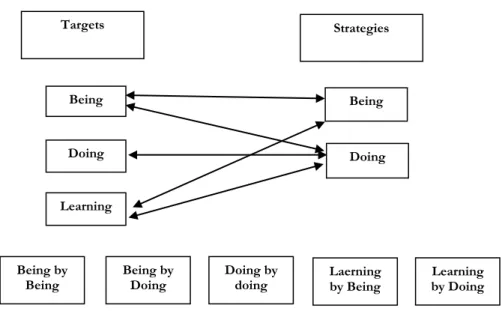

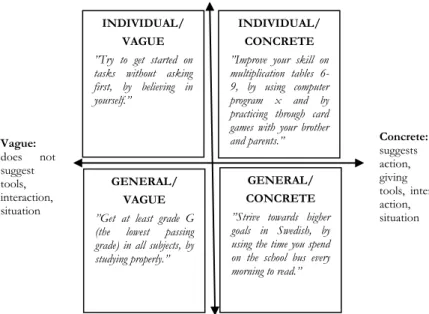

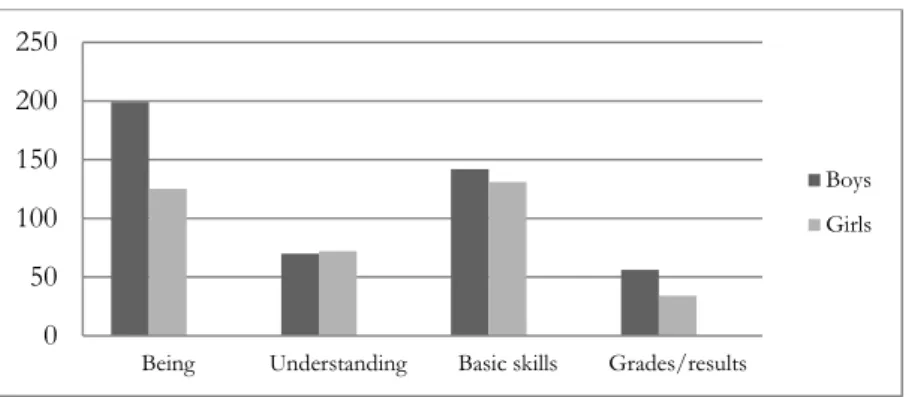

This thesis aims to generate knowledge of the IDP as a tool in terms of what characterizes IDP documents as well as teachers‟ descriptions of continuous IDP work. It contains four arti-cles. The first two are based on 379 collected IDP documents from all stages of compulsory school, and the last two build on interviews with 15 teachers. Throughout, qualitative content analysis has been used for processing data. The analytical framework comprises Latour‟s con-ceptual pair inscription – translation, Wartofsky‟s notions of primary/secondary/tertiary arti-facts, and Wertsch‟s distinction between mastery and appropriation, which together provide an overall framework for understanding how the IDP becomes a contextually shaped tool that mediates teachers‟ actions in practice. Moreover, the activity theoretical concept of contradic-tion is used to understand and discuss dilemmas teachers experience in relacontradic-tion to IDP. In article 1, targets and strategies for future learning given to students are investigated and discussed in relation to definitions of formative assessment. Concepts were derived from the data and used for creating a typology of target and strategy types related either to being aspects (students‟ behavior/attitudes/personalities) or to subject matter learning. In article 2, the distri-bution of being and learning targets to boys and girls, respectively, is investigated. The results point to a significant gendered difference in the distribution of being targets. Possible reasons for the gendered distribution are discussed from a doing-gender perspective, and the proportion of being targets in IDPs is discussed from an assessment validity point of view.

In article 3, teachers‟ continuous work with IDPs is explored, and it is suggested that IDP work develops in relation to perceived purposes and the contextual conditions framing teachers‟ work. Three qualitatively different ways of perceiving and working with IDP are described in a typology. Article 4 elaborates on dilemmas that teachers experience in relation to IDP, concern-ing time, communication, and assessment. A tentative categorization of dilemma management strategies is also presented.

Results are synthesized in the final part of the thesis, where the ways in which documents are written and IDP work is carried out are discussed as being shaped in the intersection between rules and guidelines at national, municipal and local school level, and companies creating solu-tions for IDP documentation. Various purposes are to be achieved with the help of the IDP, which makes it a potential field of tension that is not always easy for teachers to navigate. Sev-eral IDP-related difficulties, but also opportunities and affordances, are visualized in the studies of this thesis.

INCLUDED ARTICLES

The thesis is based on the following included articles:

ARTICLE 1

Hirsh, Å. (2011). A tool for learning? An analysis of targets and strat-egies in Swedish Individual Education Plans. Nordic Studies in

Education 31(1), 14-30.

ARTICLE 2

Hirsh, Å. (2012). The Individual Education Plan: a gendered assess-ment practice? Assessassess-ment in Education: Principles, Policy &

Practice 19(4), 469-485.

ARTICLE 3

Hirsh, Å. (2013). IDPs at Work. Scandinavian Journal of Educational

Research. DOI: 10.1080/00313831.2013.840676

ARTICLE 4

Hirsh, Å. The Individual Development Plan: Supportive tool or mis-sion impossible? Swedish teachers‟ experiences of dilemmas in IDP practice. Accepted for publication in Educational Inquiry.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Förord... 11

Introduction

... 15

Sorting out the terminology ... 18

Aim and research questions ... 19

Background ... 22

Different dimensions of IDP ... 23

Assessment purposes of the IDP: summative and formative assessment ... 24

The emergence of IDP ... 27

History of home-school contact ... 27

Changes in steering and control of Swedish schools ... 30

The 2006 IDP reform... 31

The 2008 IDP reform... 33

Evaluations of the reforms ... 34

Tensions between assessment practices inherent in IDP ... 36

Previous research ... 40

Fostering, normalization and power structures ... 41

Assessment, participation, influence and communication ... 45

Tools for documentation ... 50

Concluding remarks ... 51

Theoretical frames ... 54

Positioning the study ... 55

Mediated action ... 58

Mastery and appropriation ... 59

Primary, secondary and tertiary artifacts ... 60

The use of concepts from activity theory ... 63

Actions as part of an activity system... 63

Context: rules, community and division of labor ... 64

Contradictions ... 65

Method ... 67

Method-theory ... 67

First data collection ... 69

Second data collection ... 71

Analysis procedures ... 74

Trustworthiness... 77

Generelizability ... 78

The four articles: a summary ... 80

Article 1 ... 80

Article 2 ... 83

Article 3 ... 85

Article 4 ... 88

Discussion ... 91

Articles 1 and 2: What characterizes the IDP documents? ... 91

Contribution ... 96

Articles 3 and 4: What characterizes teachers’ work with IDPs? ... 97

Purpose as a central concept ... 98

The shaping of IDP practices... 100

The role of dilemmas ... 101

Reflections on theory ... 104

Reflections on method ... 107

Future research ... 109

Svensk sammanfattning

... 111Bakgrund ... 111

Syfte och frågeställningar ... 113

Teoretiska ramar ... 113 Metod ... 116 Resultat ... 117 Artikel 1 ... 117 Artikel 2 ... 119 Artikel 3 ... 120 Artikel 4 ... 122 Avslutande kommentarer ... 125

References ... 127

Appendix 1: Interview guide... 137

Bilaga 1: Intervjuguide (svenska) ... 140

Article 1 ... 143

Article 2 ... 161

Article 3 ... 179

FÖRORD

Det är svårt att tro att det är sant. Nästan fem år har gått och det är dags att sätta punkt och avsluta en resa som varit omvälvande och fantastisk på många sätt. Vandringen längs doktorandvägen har ofta känts allt annat än rak och arbetet har varit hårt och inte sällan mödosamt. När jag ser tillbaka och summerar tänker jag dock i första hand på hur fantastiskt roligt det har varit, jag känner mig priviligierad som har fått göra den här vandringen och jag är stolt över vad jag har åstadkommit. Många har – mer eller mindre di-rekt – bidragit till att det blev en avhandling som jag kan vara stolt över, och många har – på olika sätt – förgyllt min tillvaro utmed vägen. Detta förord tillägnas er som har funnits där. Att jag har genomgått en forskarutbildning och skrivit en avhandling är fantastiskt, men minst lika fantastiskt är att det finns så många människor att tacka!

Allra först vänder jag mig till mina handledare som med engagemang, värme, klokskap och tålmodig läsning av texter har stöttat och hjälpt mig framåt i min utveckling och mitt skrivande. Claes Nilholm – jag har lärt mig så oerhört mycket av dig! Skarp granskning och rättfram kritik har blandats med spännande diskussioner kring stort som smått och en stor portion upp-muntran, humor och skratt. Ditt engagemang har varit smått fantastiskt – inte bara har du bidragit till att driva min forskningsrelaterade utveckling framåt, du har dessutom sett till att jag i övrigt aktiverats i att läsa deckare och lad-lit, och dessutom använt mig för att höja din egen skill-level i diverse spel. Viveca Lindberg – trots ditt späckade schema har jag alltid känt att du finns nära till hands med dina eftertänksamma och kloka råd. Din varma närvaro har betytt väldigt mycket för mig. Du är en fantastisk förebild både som forskare och människa! Och Cristina Robertson – du har inte bara varit handledare, du har varit min mentor, kollega och vän, och det har varit otro-ligt inspirerande och lärorikt att få arbeta tillsammans med dig! Att du alltid funnits nära till hands har varit ett enormt stöd, inte minst under den period då livet och hälsan tog en oväntad vändning och allt kändes tungt. Jag vill också rikta ett varmt tack till Tomas Kroksmark, som var min handledare när jag började som doktorand. Du stod för kunskap, innovation och inspiration på ett sätt som bidrog till att jag direkt kände att den akademiska världen var både spännande och rolig!

Som doktorand inom Akademin för skolnära forskning har jag finansierats av 13 kommuner i Jönköpings län i samverkan med Högskolan för lärande

Förord 12

och kommunikation i Jönköping (HLK). Mina år som doktorand har innebu-rit ett betydelsefullt kunskapsutbyte med verksamma ute i kommunerna, såväl skolchefer och utbildningsledare/strateger som rektorer och lärare. Jag vill tacka HLK och alla bidragande kommuner för att jag har fått förmånen att vara doktorand. Ett särskilt tack vill jag rikta till Jönköpings kommun, min arbetsgivare sedan många år, som på olika sätt stöttat och gjort det prak-tiskt möjligt för mig att genomföra min forskarutbildning.

Mina år som doktorand på HLK har inneburit förmånen att få lära känna nya kollegor och vänner. En hel rad fantastiska doktorand- och korridorskompi-sar har förgyllt min tillvaro och förtjänar ett stort och varmt tack. Först och främst världens största kram till Ingela Bergmo Prvulovic, min ängel och panda-halva – utan dig och alla våra underbara stunder tillsammans hade det aldrig gått. Tack också till Mikael Segolsson (för din uppmuntran som fick mig att våga söka forskarutbildningen), Karin Karlsson och Ann Ludvigsson (för alla viktiga samtal tidiga morgnar), Rebecka Sädbom (för den trygghet du innebar när vi båda var färska Akademi-doktorander), Pernilla Mårtens-son (för att du varit den bästa rumskamrat man kan ha), Karin Alnervik (för alla teori-samtal och ditt ständiga leende), Ulrica Stagell och Joel Hedegaard (för klokhet och eftertanke) och Christian Eidevald (för råd, uppmuntran och kloka synpunkter). Tack också till övriga som funnits med i olika dok-torandgrupper och på så sätt bidragit med kunskap (och trivsel): Annica Otterborg, Sara Hvit, Pia Åman, Karin Åberg, Martin Hugo, Håkan Fleischer, Helen Avery, Ulli Samuelsson, Mats Granlund, Ulla Runesson och Elsie Anderberg. Jag vill i sammanhanget också rikta ett särskilt tack till min avdelningschef Margareta Casservik (för att du stöttat mig och trott på mig hela vägen), RUC-utvecklingsledare Fausto Calligari (för ditt utmärkta sätt att vara länk mellan kommunerna och oss kommundoktorander) och forskarskolans utbildningsledare Per Askerlund.

Jag har även haft förmånen att få ingå i ett nationellt nätverk kring bedöm-ningsfrågor som med jämna mellanrum träffas på Stockholms universitet. Tack till alla doktorandkollegor där och till Viveca för ditt sätt att hålla samman och inspirera gruppen till ständig utveckling. Sist men inte minst vill jag också tacka för noggrann läsning och värdefulla synpunkter vid halv-tids- och slutseminarier: diskutant Eva Forsberg och läsgrupp Elsie Ander-berg och Christian Eidevald vid halvtid, och diskutant Anne Line Wittek och läsgrupp Mats Granlund och Monica Nilsson vid slutseminariet.

Att genomgå forskarutbildning och skriva avhandling är sannerligen speci-ellt. Man går in i en bubbla av tankar som mal någonstans i huvudet mest hela tiden, och det är lätt att bli fullkomligt uppslukad i denna bubbla. Jag tycker inte att jag har blivit det. Nog för att jag ”brinner” för mitt forsk-ningsämne och för att få bidra till skolutveckling, men det finns annat i livet som också är viktigt. Inte sällan innehåller förord i avhandlingar uttryck av typen ”nu, kära familj och vänner, ska ni äntligen få se mer av mig igen”. Det kan jag inte skriva, för så uppslukad har jag inte varit. Familj, vänner och fritidsaktiviteter har fått sitt utrymme hela tiden, och det tror jag min avhandling bara har mått bra av. Livet utanför forskarutbildningen stannar inte av i fem år. Barnen fortsätter växa, gå i skolan och ha en synnerligen aktiv fritid. Därmed har de också fortsatt behöva en mamma som finns i de-ras liv, läser läxor med dem, engagerar sig i dede-ras aktiviteter, tränar tillsam-mans med dem och pratar med dem om livets vedermödor. Så, mina älskade änglar, Natalie, Jonatan och Ellen – tack för att ni har sett till att jag inte kunnat jobba en massa på kvällar, helger och annan ledig tid. Det är under-bart att jag tillsammans med er fått tillbringa oändligt många timmar på id-rottsplatser, i sporthallar, i ridhus, på gym, och på hockeyarenor. Och att jag nu för tredje gången ”går om” högstadiet är faktiskt också lite kul. Kluriga matteuppgifter och förhör i SO och NO har varit bra repetition för mig också. Tiden med er gör att man kopplar bort forskningen – och det behövs! Ett stort tack också till min man, Tal, som funnits där som stöd hela tiden. Guldmedalj till dig – jag har inte varit lätt alla gånger. Jag älskar er alla!

Jag vill avsluta detta tacksamhetsfyrverkeri med att vända mig till familjen Nilsen sa, Christian, Emil och Clara. Ni är fantastiska Utan er hade inte den vardagliga logistiken fungerat och fritiden hade inte varit lika rolig och innehållsrik. Tack för att ni finns!

Med detta sätter jag punkt för avhandlingen och en epok av mitt liv. Mot nya äventyr!

Habo i oktober, 2013

Förord 14

INTRODUCTION

This thesis deals with individual development plans (IDPs) in Swe-dish compulsory schools. An IDP is an assessment document answer-ing to summative as well as formative assessment purposes. The IDP has an informative function, apprising students and parents of the re-sults and progress of the student in school, as well as a forward-aiming educational planning function. In contrast to the action plan, a similar type of document that is used for pupils in need of special support (SEN), IDPs are given to all students in compulsory school once every semester during parent-pupil-teacher meetings1.

I myself have been a teacher at secondary school level for many years, and I remember when we were told, in 2006, that we were to draw up specific documents during the parent-pupil-teacher meetings. Along with students and parents, we would summarize in writing the students‟ strengths and weaknesses, and, on the basis of this, specify what was most crucial for each student to aim for ahead. The stu-dents‟ and parents‟ right to influence had been emphasized as cen-tral, and the writing of the document tended to be based on teachers asking the students questions such as „What do you think you are good at?‟, „What do you think is difficult?‟, „What would you like to work on a little extra?‟, and „What do you want the school to help you with?‟. On one occasion, we had a visit from School Inspection, who collected and evaluated a sample of our IDP documents. We were

1 Teachers' administrative workload is currently under investigation, and in a

department memorandum (Ds 2013:23) it is suggested that IDPs should be drawn up once instead of twice a year in grades 1-5, and that IDPs should no longer be required in grades 6-9 of compulsory school.

Introduction 16

judged to be inadequate in our IDP-writing and asked to consider how we could improve.

We had no more than begun the process of considering how we could develop our current IDPs, however, when a new IDP reform was in-troduced. According to the new reform, in addition to the forward-aiming summary drawn up at the parent-pupil-teacher meeting, stu-dents were to receive written summative assessments in all school subjects in their IDPs. The municipality created a template for the new type of IDP documentation, where students‟ knowledge in each subject was to be graded in terms of „On the way to reaching the goal‟, „Reaches the goal‟, or 'Reaches the goal by a margin‟. In addi-tion to this, we were to add explanatory and forward-aiming com-ments in each subject.

A web-based system was introduced, where all subject teachers wrote their assessments of students. When sitting as mentors2 with students and parents in the parent-pupil-teacher meetings, many of us noted how different the assessments written by various teachers could be. Some teachers only checked the boxes with „grade levels‟ and wrote no further comments, whereas others wrote long and extensive texts about each student. Some wrote in a very general manner, more or less the same comments for all students in a class, while others wrote very specific information on each individual student. This led to dis-cussions among the school staff and at the municipal level, concern-ing students‟ and parents‟ right to expect the same from all teachers. In 2009, when the second IDP reform was still in its initial stage, I stopped working as a teacher and began working on my dissertation.

2 At secondary school level the students in a class have different subject

teachers in each school subject. One of these teachers functions as a men-tor/class teacher with extra responsibility for the students in the class. The mentor leads the parent-pupil-teacher meetings, compiles the written as-sessments, and draws up the forward-aiming planning in collaboration with the students and parents.

Since then, I have followed the development of IDP from my position and point of view as a researcher.

Assessment issues have always interested me, issues concerning formative assessment in particular. The focus of my research on as-sessment issues in school was predetermined from the start of my dis-sertation process by a number of municipalities that have contributed to financing my studies. My choice to study teachers‟ assessment through IDP largely had to do with the fact that assessments in IDPs are to contain explicitly formative assessments. Moreover, the IDP phenomenon was new and relatively unexplored, and I thought there was good reason to study IDP documents as well as teachers‟ atti-tudes toward and perceptions of IDP.

Lately, the general debate has concerned, to a large extent, the fact that teachers spend so much time on administration and documenta-tion that they no longer find time for planning and evaluating their lessons. The documentation, which up until now has been regarded as quality assurance, is increasingly perceived as a threat to the quality of the school. As a new election approaches, politicians speak of re-moving some of the requirements for documentation in order to pro-vide better conditions for teachers to focus on what is described as their core mission – teaching.

I consider it important, at this point, that the discussion not simply stop at issues dealing with removing or retaining the IDP. Rather, it ought to concern what is perceived as beneficial and sustainable and what is perceived as unsustainable in relation to IDPs. We ought to discuss that which teachers, students, and parents perceive the IDP can or cannot contribute with. For eight years now, teachers have dealt in various ways with difficulties and opportunities surrounding the IDP, and many feel that through this process they have developed a fruitful and functioning practice. The articles and overall chapters of this thesis show that the IDP is multifaceted in many respects, and that there are opportunities as well as concerns that are worth consid-ering.

Introduction 18

SORTING OUT THE TERMINOLOGY

When I began writing the first article of my thesis, I hesitated as to which English terminology I would use for the Swedish concept of „Individuella utvecklingsplaner‟. In one English text from the Swe-dish National Agency for Education3 (SNAE) (2009), the term

indi-vidual development plan is used. Since international comparisons

were to be made, I found it relevant to try to discover what that con-cept would relate to internationally. A Google Scholar search of the term „individual development plan‟ generated approximately 1500 hits, most of which related to adult learning and development, work-places, and career supportive activities. The kind of educational plan-ning document for schools that the Swedish term „individuell utveck-lingsplan‟ refers to is more in line with that which is internationally referred to as an individual education plan4. This term is generally

used for documents prepared for students with special needs in rela-tion to learning and/or funcrela-tioning in the compulsory school context. In content, these documents often resemble the Swedish „utveckling-splan‟ - in that they contain targets and strategies for future learning, follow-up of results, clarification of responsibilities and agreements, etc. For this reason, I chose to use the term individual education plan when writing my first two articles, with a thorough clarification of the differences between the documents I referred to when talking about individual education plans, and the documents given to students with special educational needs internationally. An important difference is that the latter documents primarily address special needs and are of-ten prepared by specially trained personnel. I do not make any

3 The Swedish National Agency for Education is an authority working for the

Department of Education, providing support to school staff and municipalities. Throughout the thesis I will use the abbreviation SNAE when referring to the Swedish National Agency for Education

4 The Swedish counterpart to the internationally termed individual education plan

parisons concerning the actual content of the documents in that sense, rather, I highlight differences and similarities concerning documenta-tion as a phenomenon, how the documentadocumenta-tion is used in practice, and the tools and forms for such educational planning documents.

For the third article, I changed the terminology, following referee comments in which I was advised to use the term individual devel-opment plan in accordance with an SNAE translation. Thus, in arti-cles 1 and 2, the term individual education plan is used, whereas in articles 3 and 4, as well as the general parts of the thesis, the term in-dividual development plan is used.

AIM AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This thesis aims to generate and deepen knowledge of individual de-velopment plans as documents given to students and as tools for teachers for acting in practice. All knowledge is perspective bound, and I have used a socioculturally/activity-theoretically inspired point of view in my studies. I understand the IDP as a tool that mediates teachers‟ actions in practice, i.e., teachers understand and handle (part of) their work through the IDP document. A point of departure is that the IDP is not a tool that can simply „be put into operation‟ in a cer-tain given way. Individual (teachers in collaboration with students and parents), tool (IDP) and context (rules and conditions) mutually shape each other; thus, the ways in which the IDP is put into practice may vary. The included empirical studies concern the IDP tool and teachers‟ use of the tool, but in relation to background, previous re-search, and theoretical concepts it is also possible to discuss the rela-tion between the IDP as ideal construcrela-tion and how it is realized by teachers in local contexts.

The use of IDPs in Swedish schools is investigated in four empirical studies. The first two examine documents and the latter two examine teachers‟ work with the documents.

Introduction 20

The overarching questions are:

(i) What characterizes IDP documents, both in terms of de-sign and in terms of the kind of assessment displayed in the documents?

(ii) What characterizes teachers‟ descriptions of their work with IDPs in relation to perceived purposes and in terms of difficulties as well as opportunities connected to IDP work?

Each of the four articles have their own specific aims and research questions:

ARTICLE 1

Article 1 aims to develop further knowledge about the use of forma-tive assessment in terms of targets and strategies given to pupils in their IDP documentation, by answering the following questions: (i) How are targets and strategies expressed in Swedish IDPs? (ii) In what way(s) do targets and strategies interact with each other? (iii) What differences (if any) are there between IDPs for pupils in differ-ing stages of school?

ARTICLE 2

Article 2 aims to gain knowledge of gendered differences and similar-ities in targets given to pupils in IDPs, by answering the following questions: (i) How are different target types (being as well as learning aspects) distributed in IDPs given to boys and girls of different grade levels in the Swedish compulsory school? (ii) What are the possible reasons for a gendered distribution? An additional interest is aimed at discussing issues of assessment and assessment validity in relation to the gendered distribution of targets.

ARTICLE 3

Article 3 aims to generate knowledge of teachers‟ practices with re-gard to IDP as a tool, by answering the following questions: (i) What do teachers perceive as the purpose(s) of IDP? (ii) What IDP practic-es can be discerned in teachers‟ dpractic-escriptions? (iii) What contextual aspects may affect perceptions of the purpose of the IDP and the im-plementation of the plan in practice? An additional interest is aimed at the (possible) relation between IDP and formative assessment.

ARTICLE 4

Article 4 aims to explore the dilemmas and coping strategies for han-dling dilemmas that can be discerned in teachers‟ descriptions of IDP practices.

Background 22

BACKGROUND

The three chapters that follow are intended to provide a context for the four articles included in the thesis as well as the discussion in which the results are synthesized. The emergence of the IDP tool can be understood as a response to perceived societal needs. As will be apparent in the background, previous research, and theory chapters, the IDP can be understood as answering to different needs and it is possible to view it as a tool for achieving various, potentially contra-dictory, purposes. The needs motivate concrete actions - in this case, IDP related actions. The IDP is used by teachers in practice and is also, in a sense, shaped by them. There are, however, other actors and other dimensions that contribute to shaping the IDP into a tool for documentation and teachers‟ actions in practice.

In this chapter I begin by briefly describing how such dimensions can be understood. Since this can be regarded as a theoretical framework against which the results of the included studies can be discussed, I will return to the issue in the chapter on theoretical perspectives. I consider it important, however, to provide the reader with an intial clarification of how I understand different dimensions of IDP, which dimension my empirical data concerns, and which dimensions are to be understood as a background against which data are interpreted. I then move on to give an account of the assessment purposes of the IDP before I turn to describing and problematizing the short history of the IDP itself and how it has developed from the time of its initial proposal to the present. In addition, because the IDP tool is an im-portant part of the contact between school and home, I give an

ac-count of how this contact has evolved in relation to societal needs and purposes as well as changing views of learning. I conclude the back-ground chapter by problematizing tensions between different IDP related purposes.

DIFFERENT DIMENSIONS OF IDP

The fact that IDP is shaped at different levels can be compared to Goodson‟s (1995) understanding of five different dimensions of cur-riculum. First there is the ideological dimension, the ideal which forms the basis for the way of thinking when the curriculum is formu-lated. Due to political and pragmatic factors, it is impossible to fully implement the ideological dimension. The formal dimension is the actual curriculum that activities in school follow, which is interpreted differently in different schools. The understood dimension concerns how actors in various schools understand the formal curriculum. A number of factors can lead to differential interpretations by, for in-stance, teachers and school leaders. The implemented dimension is what actually takes place in the classrooms. Teachers can understand the curriculum differently, but even if they do have similar under-standings, their actual classroom practices may vary due to other con-textual factors. Finally, the experienced dimension concerns that which the students experience in the classroom.

In this thesis I interpret the IDP in the same way. There is an ideolog-ical dimension on which the idea of IDP is based in the sense that it is based on a certain epistemology and democratic ideals concerning how students are to be viewed. The ideological dimension is behind and affects the content and wording of the formal dimension of IDP as it is written in policy documents and, particularly, SNAE guide-lines that teachers and school leaders are to follow. The understood dimension in the IDP case differs from Goodson‟s understanding of curriculum in that an „outside‟ commercial actor has entered, thus situating this dimension in the intersection between the central

munic-Background 24

ipal level (politicians and school administration), companies develop-ing solutions for documentation, and principals‟ and teachers‟ under-standing of the formal documents. The empirical studies in this thesis do concern teachers‟ understood dimension, but foremost they con-cern the implemented dimension of IDP and how this is manifested in documents and teachers‟ descriptions of their practices with regard to IDP. The ideological and formal dimensions, as well as the under-stood dimension at municipal and company-solution level provide a background for the empirical studies.

ASSESSMENT PURPOSES OF THE IDP:

SUMMATIVE AND FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

Teachers‟ assessment practices are many and diverse, some formal and some more informal. The IDP is a central part of teachers‟ as-sessment practices, and can be regarded as formal in the sense that all pupils are to have an IDP document containing written summative assessments as well as forward-aiming targets and strategies related to assessment criteria in the syllabuses in all school subjects. In an-other sense, the IDP can be regarded as more of an informal „working document‟ that is used formatively, on an ongoing basis, in the class-room.

Up until 6th grade, the IDP represents the only formal, written as-sessment Swedish pupils receive5. The assessment purposes of the current IDP are summative as well as formative: the written assess-ments in the IDP are to summarize students‟ knowledge and contain forward-aiming elements, and function as a tool for acting in practice. In this way, the IDP is representative of what is sometimes referred to as „the new assessment paradigm‟ (Havnes & McDowell, 2008), where there is a drive to use assessment not only as a way of

5 Up until 2011, Swedish pupils received formal grades twice a year in

ling and summarizing student achievement, but also as a tool for learning. Summative assessments have the purpose of determining academic development after a unit of material, and formative assess-ments have the purpose of monitoring and supporting student pro-gress during the learning period (Dunn & Mulvenon, 2009). In an article from 2006, Popham gives a definition of formative assessment that he claims was agreed upon by a number of researchers:

An assessment is formative to the extent that in-formation from the assessment is used during the instructional segment in which it occurred, to adjust instruction with the intent of better meeting the needs of the students assessed. (p. 3).

In my first article, I claim that the formative function of the IDP can be seen much in the same way, although in a longer time perspective. The quote above (Popham, 2006) can be seen as referring to short cycle formative assessment taking place in the classroom in that it says that assessment information shall be used to adjust instruction

during the instructional segment in which it occurred. Even though

assessment in IDPs generally concern longer cycles, the teacher‟s role in clarifying learning intention, sharing criteria for success and providing feedback that moves the learner forward (Wiliam, 2009; Jönsson 2010) is the same as in short cycle classroom assessment. The instructional segment must be seen in another time perspective however.

Bennett (2011) argues that two types of arguments must be involved in a theory of action of formative assessment practices: a validity ar-gument to support the quality of inferences and instructional adjust-ment, and an efficacy argument to support the impact on learning and instruction. It is not enough to talk about one of them. If this state-ment were to hold for IDP practice, this would mean that IDP practice ought to involve teachers‟ making the „right‟ inferences about pupils‟ present levels and their being able to use these inferences to give tar-gets that are valid not only in relation to curricular goals but also in

Background 26

relation to pupils‟ present levels. In addition, teachers should be able to provide relevant strategies, suitable for each pupil, and make sure that everything written and agreed upon actually has an impact on classroom instruction. From my point of view, that an IDP practice lives up to both the validity argument and the efficacy argument de-mands a lot. First of all, teachers must have a thorough knowledge of assessment purposes; secondly, there is the system issue (Bennett, 2011). Formative assessment exists within a larger educational con-text, which in order to function effectively must be coherent with re-spect to its components. The effectiveness of formative assessment, such as IDP assessment, is limited by or benefits from the larger sys-tem in which it is embedded.

It is worth noting that, at the primary and intermediate stages of school, the class teacher who teaches most subjects also writes most of the IDP content - the summative assessments in different subjects as well as the forward-aiming part with central targets and strategies for the future. In secondary school, on the other hand, pupils have different teachers in different subjects, wherefore the summative as-sessments in their IDPs are written by a number of different teachers. For these pupils, one teacher functions as a mentor with extra respon-sibility for a number of pupils in a class, and this mentor is responsi-ble for summarizing the forward-aiming part with targets and strate-gies. Thus, information given by several teachers is interpreted (and possibly transformed) by the mentor before it reaches the student and parents. It is also important to consider the domain dependency issue. To be effective, formative assessment requires not only knowledge of general principles and techniques, but also a certain measure of sub-ject-specific knowledge (Bennett, 2011). For teachers who do not teach more than one or two subjects, it is difficult to make inferences and know what to ask from pupils in subjects other than their own. If we consider the fact that all educational assessment is inferential – that we can merely make conjectures based on observations of pupils‟ work, participation, test results, etc. – it seems the validity argument would be stronger the better the teacher knows his/her pupils:

Each teacher-student interaction becomes an opportunity for posing and refining our conjec-tures, or hypotheses, about what a student knows and can do, where he or she needs to im-prove, and what might be done to achieve that change (Bennett, 2011, p. 17).

It is reasonable to assume that a class teacher in primary and interme-diate school who works together with his/her pupils‟ several hours

every day would be better prepared to make valid inferences than a mentor who only meets the pupils one or two hours a week. Thus,

there are different traditions and rules at secondary school level than at primary and intermediate, and presumably such contextual condi-tions contribute to shaping teachers‟ IDP related accondi-tions in different ways.

THE EMERGENCE OF IDP

The following section deals with the emergence of the IDP in relation to policy. It is about how traditions and changing conditions of teach-er action and autonomy can be undteach-erstood in relation to the IDP as assessment practice and as part of the contact between school and home.

HISTORY OF HOME-SCHOOL CONTACT

While the IDP is part of an assessment practice and mainly viewed as such in this thesis it is currently also a significant part of the contact between home and school. Just as assessment practices have changed and developed over the years, the development of the contact between home and school can be tied to societal needs and demands and the way in which views of learning have changed. The recurring meet-ings that we have today in Swedish schools between teachers,

stu-Background 28

dents and parents – and of which the IDP is part have their roots in post-war changes in theories of child development and learning, as well as in an increased emphasis on democratic ideals such as inde-pendence and critical thinking (Granath, 2008). The need for a form of contact between home and school was born when discussions about learning no longer revolved around children‟s predispositions: if children are malleable, then it must also be possible to influence children‟s future fate. Increasingly, the discussion also concerned the fact that a child is shaped by his or her environment, not least the home environment. Therefore, it was in the interest of the school to get a picture of the child's social life and home conditions. The idea of developmental meetings between home and school were not real-ized, however, until the early 1970s, in the form of regularly recur-ring „individual talks‟ (Hofvendahl, 2006, my translation).

The era of the „individual talk‟ lasted until the mid-1990s, when it was replaced by what is called a developmental parent-pupil-teacher meeting. The „individual talk‟ had proved to be mostly debriefing and reporting of results, rather than a forum for discussion and planning of necessary actions. With the introduction of a new term for the meeting, there were new guidelines emphasizing a future-oriented, equitable and dialogic conversation between three parts (SNAE, 1998, 2001).

Hofvendahl (2006) points out that there are a couple of important dif-ferences between the „individual talk‟ and the „developmental parent-pupil-teacher meeting‟, at least in terms of how they are described in policy documents and similar texts. Whereas student participation in the „individual talk‟ was desirable but not mandatory, it is considered a prerequisite for the „developmental parent-pupil-teacher meeting‟. The SNAE (1998), furthermore, argues that the „individual talk‟ meant that parents came to school for a 15 minute meeting every se-mester to receive information about their child‟s current knowledge status and results. In contrast to this, they describe the „developmental parent-pupil-teacher meeting‟ as a new way of meeting together with the student, where all parts actively discuss and plan for the future.

When something old is replaced by something new, it is often a poli-cy discourse to describe the new in more positive terms than the old, in this case old meetings are described as „debriefings‟ of the current situation, and the new as „aiming for the future‟ (Hofvendahl, 2006). Differences that can be traced are that the new meeting is more set to look ahead, and, in line with the 1994 curriculum, it is characterized by goal orientation. It is also possible to discern a shift to a more in-dividualized approach. A government letter on quality work in pre-schools and pre-schools mentions that “the developmental parent-pupil-teacher meeting should routinely lead to a forward-aiming individual development plan” (Skr 2001/02: 188, s 18, my translation). Thus, thoughts of individual development plans start to appear in policy texts from the early 2000s.

Eriksson (2004) claims that for at least half a century there have been expressed political expectations on parents to support and get in-volved in their own children‟s schooling. In recent decades, however, there has been a change, both internationally and from a Swedish per-spective. An increasing mandate has been placed in the hands of par-ents when it comes to making decisions and being actively involved in their children‟s education. Education has increasingly come to be defined as a matter for the individual and as a family affair. In paral-lel, it also appears that the school has become more accountable to parents (Eriksson, 2004). Brown (1990) argues that the education pol-icy landscape from the 1970s and onwards has entered a stage that he describes as parentocracy. This has not grown out of public or paren-tal needs but has, rather, evolved as a consequence of the state‟s hav-ing bestowed increased responsibility on parents, as formulated in slogans such as “educational choice” and “free market” (Brown, 1990, p. 67). Through this development, Brown argues, we are now in a situation in which children‟s education is increasingly dependent upon the wealth, awareness and wishes of parents. Eriksson (2004) mentions Whitty‟s (1997) arguments that, whereas discussions used to concern how parents were fulfilling their responsibilities to help their children with school work, the discourse now tends to be more about the obligation of schools to fulfill their responsibility toward

Background 30

parents. Parents have the right to receive information and reports from the school and they also have the right to lodge complaints at the schools. They shall have the possibility to judge their children‟s progress and achievements and thereby evaluate the efficiency of their own school compared to other schools. Schools may also benefit from parental participation. Whitty (1997) describes an increased in-terest from schools in „tying up‟ the parents and ensuring their sup-port through the establishment of different types of documents and contracts.

CHANGES IN STEERING AND CONTROL OF SWEDISH SCHOOLS

During the past two decades, the system for control of the Swedish school has undergone major changes. Since the early 1990s, the sys-tem has been one of management by objectives and results, on the one hand creating more flexibility and allowing for local, situation-specific solutions and, on the other hand, controlling the results. Re-sponsibility for the school was decentralized to the municipal level in the 1990s, while the central level concentrated its responsibilities to include quality control, national equality and legal security. Moving responsibility and decisions to the municipal level was described as important from the points of view of both democracy and efficiency (Krantz, 2009). In recent years, the Swedish school has been por-trayed as lacking in quality, as permissive, and as generating poor results in terms of goal attainment among students and in terms of rankings in comparative international measurements (e.g., Avdic, 2010). In answer there has been a growing emphasis on central moni-toring, evaluation and inspection. Increasingly extensive documenta-tion has come to be viewed as quality assurance and as a means of holding schools accountable for their results (Forsberg & Lindberg, 2010). The IDP is part of this picture. It has developed through two major reforms: The first, in 2006, introduced the IDP as a forward-aiming tool for a more individually targeted educational planning and

greater involvement of students and parents. The second, in 2008, expanded the purpose of the IDP to include written summative as-sessments of students‟ knowledge in each school subject.

The following section will describe the two IDP reforms in terms of the needs and objectives of each, how each has been described in guidance from the SNAE, and how each has been evaluated.

THE 2006 IDP REFORM

Preparatory work, proposals, and decisions concerning the first IDP reform came during a period when Sweden had a left-wing govern-ment. Wennbo (2005) argues that a variety of motives as to why the first IDP reform was introduced can be traced in policy proposals. The reason most emphasized is perhaps unsurprisingly that the reform was expected to be beneficial in different ways for student learning and school performance. In 2001 (Ds 2001:19) a governmen-tal expert committee suggested that the purpose behind the action plan “optimally planning the individual‟s conditions for learning” (p. 30, my translation) – should be valid for all students and that each individual should have the right to an educational planning document containing guidance toward optimal learning performance. A docu-ment such as the IDP – that visualizes progress was also expected to develop students‟ meta-cognitive reflections and thus contribute to increased learning, involvement and motivation. Policy justifications indicate that transparency and documentation were expected to con-tribute to more effective learning among students, as these were ex-pected to enable and motivate students to a greater extent (Wennbo, 2005; Krantz, 2009). There were also other factors involved. The po-litical debate in the 1990s and early 2000s dealt to a large extent with quality management and quality assurance. Monitoring results and information about assessment and grading became key components in this discussion and the school's obligation to provide information to the home was increasingly emphasized. Wennbo (2005) points to the

Background 32

fact that the former (social democratic) minister of education clearly described the IDP as not only an educational planning document ben-eficial for students but also a way of controlling schools‟ quality. She argues that it is possible to ask Which was the strongest motive be-hind the reform: the individual‟s need for a tool for learning or the need for increased control of schools‟ (declining) results?

Documenting and informing about students‟ learning and develop-ment fulfills the argudevelop-mentative function of making the school more transparent. Transparency was expected to create understanding and legitimacy of the assessment and its grounds for all parties involved. Krantz (2009) argues that when positive values such as transparency, increased understanding, and motivation are linked to documentation and assessment, it is difficult for schools and teachers to take a criti-cal stance on these issues.

The teachers‟ synthesized observations and assessments of each stu-dent were to provide the basis for the parent-pupil-teacher meetings. Thus, the summative evaluation of the student was to be dealt with orally, while the written IDP was meant to be exclusively prospec-tive: A document describing targets and strategies for the near future was to be prepared as a trilateral agreement between the parties in-volved (SNAE, 2005). Teachers were to ensure that the school, stu-dents and parents had a common understanding of what their respec-tive actions would achieve (Krantz, 2009). The government (Ministry of Education, U2002/3932/S) stressed that the introduction of IDP did not mean that teaching should focus on more individual work. It was emphasized that learning occurs in a social context, which makes a claim on the teacher to consider contextual conditions for learning. Thus, the IDP was positioned within a potentially conflictual tension between an individual success orientation and an activity critical con-textualization (Krantz, 2009).

Teachers‟ collective preparatory work before parent-pupil-teacher meetings and IDP writing was expected to give fruitful discussions on assessment related issues and, by extension, lead to a better learning

situation for pupils. The written plan was to be forward-aiming and formative only, and it was strongly emphasized that the IDP should not be perceived as a way of grading students (Ds 2001:19).

THE 2008 IDP REFORM

After 2006, the education policy debate shifted towards greater focus on the importance of grades, knowledge measurement, and clarity concerning curricular goals and assessment criteria. Grades in earlier school years, a more differentiated grading scale, and more extensive standard testing have been profile issues for the right-wing govern-ment appointed after 2006. Under this governgovern-ment, the IDP has also been developed towards becoming a more knowledge-oriented plan. A 2008 Ministry of Education memorandum stated that information given by teachers at the parent-pupil-teacher meeting often lacked clarity, wherefore teachers ought to be given the opportunity to ex-press themselves in “grade-like forms” (Ministry of Education 2008, p. 4) in the IDP. The writings of the Educational Act were changed, and from 2008, it prescribes an IDP containing written, summative assessments in all subjects, while it also maintains the original pur-pose of IDP as a forward-aiming formative tool. The change was mo-tivated by the fact that official grades together with information given at the parent-pupil-teacher meeting and in the forward-aiming IDP were deemed inadequate in their function of providing information about students' knowledge. Claims on teachers' duty to inform were reinforced; goals and assessment criteria needed to be clarified and concretized. School problems were defined in terms of lack of effec-tiveness in goal attainment. Giving teachers the opportunity to ex-press themselves in grade-like forms was seen as a solution. In this way, the IDP was expected to contribute to countering the vagueness and increasingly widespread permissiveness of school.

Krantz (2009) argues that a number of discursive contrasts are placed against each other in various policy documents concerning IDP:

fuzz-Background 34

iness, tardiness and discontinuity are contrasted with clarity, earlier detection of problems and regularity. Undesirable variation in as-sessment is to be met with extended external control. Just as with the former reform, it is difficult for teachers and principals to adopt a crit-ical stance to a reform described in such a way.

With the introduction of written assessments and grade-like symbols in the IDP, the tension between summative and formative assessment was accentuated. One of the unions for teachers in Sweden (consist-ing primarily of teachers in the earlier school years) expressed con-cern that grade-like assessment information would degrade the infor-mation students received in their plans, and argued that teachers should engage in formative assessment and mainly express what is needed in order for goals to be achieved when formulating the IDP. The other teacher union (consisting primarily of teachers on the sec-ondary school level) was more positive toward what was described as clearer and earlier evaluation of students‟ knowledge, but simultane-ously critical to the fact that the design of the IDP was to be shaped locally (Krantz, 2009).

EVALUATIONS OF THE REFORMS

The SNAE has carried through two major evaluations of the IDP, one in 2007 and one in 2010. The evaluations are largely positive. It is important to bear in mind, however, that there is a dependency be-tween the SNAE and the authority that assigned them the mission to evaluate. Moreover, as mentioned, it might be difficult initially for teachers and principals to take a critical stance to a reform that is de-scribed as countering school problems and declining results.

In both evaluations, teachers, principals, students and parents in sev-eral municipalities answered questionnaires and were interviewed, and documents were analyzed. As mentioned, the results are predom-inantly positive, although shortcomings are highlighted and discussed to some extent. Primarily, the IDP is depicted as having had an

obvi-ous effect on the ways in which teachers speak of students‟ knowledge development in relation to curricular goals. It is argued that the IDP has contributed to developing students‟ meta-cognitive skills, and that teachers have come to realize “the importance of sys-tematic evaluation and planning of school activity” (SNAE, 2007, p. 25, my translation). In the 2010 evaluation, the written assessments are described as having had a favorable impact on the implementation of the curriculum and syllabi. Thus, in both evaluations, the IDP is depicted as being a tool for bringing about professionalization. Noted on the negative side is that the IDP is generally seen in a dis-tinctly individual context. The expert committee that investigated the matter before the introduction of the reform emphasized that the work with IDP must be viewed relationally, i.e., in relation to the context of which the pupil is a part. The SNAE (2007) argues that the IDP doc-uments in the evaluation do not live up to such expectations. Many teachers claim that the difference between the action plan and the IDP is diffuse, and, moreover, that there is great confusion concerning what should be included in the IDP. The SNAE concludes that, due to this variance in interpretations, the scope of the documents collected for the evaluations varies significantly. In the latter evaluation, 40% of the teachers claim that time to write all the assessments is insuffi-cient. Other problems mentioned are, for instance, the fact that the assessments tend to be more summative than formative, that there emerges a clear normative image of the ideal and desirable student in assessments about students‟ social development, and the fact that there is often no clear link between the written assessments and the forward-aiming planning. In the 2010 evaluation, teachers in the ear-liest school forms tend to be doubtful concerning the summative, grade-like evaluation of young children. Furthermore, the IDP is fre-quently perceived as insufficient as a tool for continuous individual planning and monitoring; logbooks, diaries and portfolios are often used alongside.

In both evaluations, the SNAE touches upon the issue of standardized templates for documentation. In their discussion of the

„professionali-Background 36

zation effect‟ that the IDP has entailed, they argue as follows: “Para-doxically, the IDP – if it becomes too mechanical and if the templates are allowed to replace teachers‟ experienced-based „tacit‟ knowledge may lead to de-professionalization” (SNAE, 2007, p. 25-26, my translation). In the 2010 evaluation, they claim to detect a development towards greater standardization in matrices, templates, and forms for documentation used within municipalities. They note that this is problematic in the sense that it may lead to a uniformity which is not necessarily positive. Schools that have developed models for documentation and documentation practice may feel that they have to set these aside in favor of common municipal templates. At the same time, pupils and parents are considered to be entitled to some form of equivalence in terms of quality within a municipality.

TENSIONS BETWEEN ASSESSMENT PRACTICES INHERENT IN IDP

Before the grading system in the Swedish school became goal-oriented in the mid-90s, there was an epistemological discussion in which an instrumental view of knowledge was placed in contrast to qualitative knowledge as Bildung. This discussion subsequently led to a „two-stage‟ target structure in the 1994 curriculum: goals were for-mulated both in terms of what students were to achieve as a minimum and in terms of what schools, teachers and students ought to continue to strive towards. A part of teachers‟ professional autonomy was to interpret and specify the direction of the „goals to strive for‟ from a

Bildung-perspective. Krantz (2009) argues that this created a tension

between goal rationality/instrumentality on the one hand and deeper and more sophisticated learning on the other6.

6The current curriculum, introduced in 2011, is not formulated with goals in

two stages. Instead, it establishes proficiency levels for grade levels A, C and E (grade levels D and B are considered to be intermediate levels that are to be used if students‟ knowledge does not qualify for the grade immediately

When problems concerning students‟ goal attainment and equivalence in assessment and grading are discussed, it appears as though the sys-tem of management by objectives and results poses professional prob-lems for teachers. Systematic monitoring and documentation is seen as one solution to the problem. At the same time, Krantz (2009) claims, the IDP-reform reinforces the tension and discursive struggle between instrumental goal-orientation and Bildung-orientation. Goal-oriented assessment on the level of the individual demands that the goals and the progression towards goals can be formulated in writing. At the same time, demands for transparency, information and uniform procedures are increasing. The discursive struggle between instru-mental goal-orientation and Bildung-orientation concerns which re-sults are to be achieved and what kind of teaching profession is to be developed. The different discourses concern to great extent teachers‟ professional autonomy. In an analysis of policy documents, Krantz (2009) claims to distinguish four different discourses bearing on as-sessment practices and IDP: a Bildung-oriented communicative dis-course, a goal-oriented political-administrative disdis-course, a market discourse, and a professionalization discourse. In my reading, the dis-courses can be understood as descriptions of shifting purposes that can be achieved with help of the IDP.

In the Bildung-oriented communicative discourse, teachers are auton-omous and self-managing within the frames of the requirements of the steering documents. Professional interaction and student partici-pation are key components. Students' knowledge is evaluated

above in its entirety). Assessment criteria in each subject are formulated as abilities (which can be summarized as analytical, communicative, meta-cognitive, information processing and conceptual abilities) at qualitatively different levels. Thus, teachers are still expected to make their own interpre-tations.

Background 38

prehensively, taking into account their differences and the relation to the context of which they are part. Meaning is created jointly rather than individually. Teacher autonomy is seen in the light of the fact that goals are not always easily formulated and concretized in ad-vance. Uncertainties must be handled professionally.

In a goal-oriented political administrative discourse, the task of con-cretizing goals and assessment criteria are shifted toward being a po-litical responsibility rather than a professional one. The focus of ped-agogical practice primarily concerns assessment in terms of measura-bility and objectivity. The professional interpretation space decreases and the external control is strengthened by inspection, standardized tests and grades. Grade-like assessments are assumed to increase stu-dents' motivation and thus, by extension, lead to better results in terms of goal attainment. Local misinterpretations and permissiveness are depicted as factors behind failing results, wherefore more central monitoring and control and extended documentation is necessary. Teachers' professional autonomy is seen as a problem rather than an asset. In this discourse, the teacher is constituted as a results-responsible executor.

Choice and competition are keystones in the market discourse. The customer makes choices on the basis of comparisons, and grounds for comparison are created through documentation, grades, and knowledge measurements. A market discourse constitutes schools and teachers as implementers of what the customer has ordered. In the professionalization discourse, assessment practice has a legiti-macy based on the claim that only qualified teachers are able to ob-jectively see the student's knowledge in a holistic perspective. The importance of teachers developing a common professional language and common forms and procedures for assessment is also stressed. Professional rather than pedagogical implications are discussed when the IDP is formulated as a professionalization project.

Traces of all four discourses are present in the IDP practices and per-ceived dilemmas that are described in studies 3 and 4 of this thesis. I will therefore return to the discourses in the discussion.

Previous research 40

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

So far, aspects that are considered relevant as background for under-standing teachers‟ work with the IDP as a tool have been described and problematized. Such aspects concern assessment purposes, home-school contact, changes in the control and steering of the home-school sys-tem, and the emergence and evaluation of IDP in relation to policy. The current chapter aims to present a picture of research that ties in closer to documentation plans and documentation practices as such, research in which the empirical basis in most cases has been various educational planning documents and teachers‟ work with such ments. The chapter concerns IDPs and comparable forms of docu-mentation tools, with a certain focus on the purposes for which such tools are used, and possible problems as well as opportunities con-nected to document content and use of such tools in practice.

Swedish research into IDPs is not very extensive. The relatively short time that the IDP has existed is presumably one reason for this. My intention has been to cover the Swedish research available, although some studies are more thoroughly described than others. Work with IDPs or resembling documentation and assessment practices can be described as a transnational trend, with similar standardized systems for documentation, contracts and instruments for regulation at the individual level. There are differences between countries, but also commonalities. In English-speaking countries there is the term IEP for individual education plans/programs, and in other countries other corresponding terms are used. These documents are equivalents to the

Swedish action plan and are given to pupils in need of special support (SEN). The Swedish IDP and action plan often resemble each other greatly and are, in many cases, identical documents (Asp Onsjö, 2006). The fact that IDP documentation is provided to all students characterizes the Swedish case (Vallberg Roth & Månsson, 2008). Given the similarities between the documentation forms and issues that can be discussed in relation to various forms of educational plan-ning documents, there is reason to make comparisons between them. Besides research into IDPs, therefore, Swedish as well as internation-al studies of action plans/IEPs will internation-also be referred to. In the Swedish case, I have mainly focused on research from the last decade (which is when the ideas of IDP emerged and were implemented in practice). For the international case, I have primarily used a meta-study of Mitchell, Morton and Hornby (2010) in which the authors present an overview of 319 studies bearning on IEP. In some cases, studies which do not concern such documentation but otherwise deal with issues of relevance for the problem area will also be referred to. While reading Swedish research into IDPs and action plans, I found two more or less distinct branches, where the first is research essen-tially focused on problematizing underlying agendas of documenta-tion practices. This research branch will be presented first. I will then turn to the other branch, which mainly focuses on practical implica-tions of IDP in relation to official or expressed purposes.

The terms IDP, action plan, and IEP will be used alternately in the following text, where IDP and action plan concern the Swedish con-text, and IEP the international.

FOSTERING, NORMALIZATION AND POWER

STRUCTURES

Swedish researchers into documentation in the form of IDPs as well as action plans have taken great interest in studying the fostering and