Perceptions of the urban practitioner:

Towards end-user stakeholder participation within the

innovations of living development process

Tero Konttinen

Kajsa Sjunnesson

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis - focus on Leadership and organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Summer 2020 Supervisor: Chiara Vitrano

Perceptions of the urban practitioner:

Towards end-user stakeholder participation within the

innovations of living development process

Tero Konttinen

Kajsa Sjunnesson

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis - focus on Leadership and organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Summer 2020 Supervisor: Chiara Vitrano

Abstract

Urban practitioners' perception of end-user stakeholders is a study area with a research gap in relation to social sustainable innovative living concepts. The aim of this paper is to further understand how urban practitioners perceive end-user stakeholders participation in the innovation of living process. This includes co-housing, sharing communities and cooperatives that have been built recently responding to societal needs and growing concerns over social sustainability in urban areas. This study attempts to answer research questions of the perception of urban practitioners towards the participation of end-user stakeholders, practitioners’ perception in its use of organisational learning, and their interpretation regarding the distribution of power between all stakeholders. The research is viewed through a theoretical conceptual model linking stakeholder theory and shared value creation; power distribution between stakeholders; and leading towards organisational learning and adaptive organisational concepts. Semi-structured interviews with practitioners, employed in the cities of Malmö and Copenhagen were conducted, transcribed and the data interpreted by the authors through an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis methodological lens. Findings suggest that most perceive a value in stakeholder participation and those practitioners exposed to end-user stakeholder participation have a higher comprehension of its potential value. Respondents agreed that the municipality remains a key stakeholder in shaping the process, even though this was not part of initial questioning. Finally, there is a notion of an interplay between power and financial resources that still controls the development process. The paper concludes while there is a perceived value of the processes and knowledge sharing on the process of end-user stakeholders not all perceive the benefits. Since no formal conclusions can be drawn from the study due to the small sample size, the authors recommend further research to increase comprehension of the perception of urban practitioners. Keywords: Perception, Urban Practitioners, Stakeholder participation, Innovations of living, Social Innovation, Sustainability, Copenhagen, Malmö

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the interviewees for being part of our research and for taking time out of their schedules during this extraordinary time.

Contents

1.0 Introduction 1

1.1 Research Problem, Purpose, Aim & Research Question 2

1.2 Core Concepts: Explanation 3

1.3 Structure of Paper 4

2.0 Background 4

2.1 Innovations of Living: History and Current Projects 5 2.2 Innovations of Living: End-user Participation in Selected Examples 6

2.3 Previous Research: Literature 8

2.3.1 Perception of Urban Practitioners 8

2.3.2 Stakeholder Participation 9

2.3.3 Power, Empowerment and Sharing 11

2.3.4 Organisational Learning, Innovation and Benefits 13

2.3.5 Urban Resilience and Sustainability 13

2.4 Summary 14

3.0 Theoretical Framework 14

3.1 Stakeholder Theory, Participation and Shared Value Creation 14

3.2 Power: Empowerment and Sharing Concepts 15

3.3 Adaptive Organisations & Learning Frameworks 16

3.4 Framework Summary and Connection to Research 17

4.0 Methodology and Methods 18

4.1 Practitioner Interviews 20

4.2 Reliability, Validity & Replicability 21

4.3 Limitations on Data Collection and Methodology 21

5.0 Research Findings 22

5.1 Overall Perception of Urban Practitioners 22

5.2 Findings on Thematic Areas of Research 23

5.2.1 End-User stakeholder participation 23

5.2.2 Municipal participation 24

5.2.3 Organisational learning 25

5.2.4 Importance in the consideration of end-user stakeholder needs/preferences 26

5.2.5 Method of end-user stakeholder participation 27

5.2.6 Competitive advantages by end-user stakeholder participation 28

6.0 Analysis of Findings & Discussion 29

6.1 Analysis of Findings 30

6.1.1 Analysis: Summary 32

6.2 Discussion 33

7.0 Conclusion & Recommendations for Further Research 35

Glossary of Terms i

References iii

Appendix A: Previous Research: List of Articles and Keywords ix

Appendix B: Interviewee Participation Document x

List of Figures & Tables

Figure 1: Photos of Current and Recent Innovative Projects 7

Figure 2: Vauban’s Local Governance Structure 8

Figure 3: Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation 9

Figure 4: New Ladder of Citizen Participation 12

Figure 5: Conceptual Theoretical Framework from the urban practitioners perspective 18

Figure 6: Power Influence Model 31

Table 1: Advantages and Disadvantages of User Involvement 11

1

Perceptions of the urban practitioner:

Towards end-user stakeholder participation

within the innovations of living development process

1.0 Introduction

Today, urban development is recommended to follow the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #11 of sustainable, equitable and resilient cities (UN, 2015). Curry (2012) and others argue housing development is a social enterprise as housing is considered a human necessity. Throughout history, innovations of living have been of importance to improving health and well-being of urban regions (Curry, 2012). This is of further importance today, during this extraordinary time related to the COVID-19 pandemic, where the resilience of economic structures and social norms are under tremendous pressure and strain (Manderson & Levine, 2020). Practitioners around the world are suggesting that this could be a pivotal time for a re-thinking on how to provide housing with a need to address quality of life and social sustainability (Thörn, Larsen, Hagbert & Wasshede, 2020; Salama, 2020).

Based on many urban practitioners, legally mandated participation for urban development does not meet the basic goals of public participation as does not incorporate a broad spectrum of the public (Innes & Booher, 2007). Consequently, it is unable to create genuine participation and trustworthy processes in conventional urban development (Ruiu, 2020). This leaves stakeholders unsatisfied perceiving they have not been heard and therefore changes in decision-making from this participation is seldomly perceived to improve urban development (Innes & Booher, 2007). This ambivalence leads to the questioning by municipalities, urban practitioners and stakeholders on the value of mandated public participation due to the adversarial nature of this participation (Innes & Booher, 2007; Qu & Hasselaar, 2011).

One potential solution to this concern of minimum mandated public participation in conventional development is to incorporate a more engaging stakeholder participation process. This is currently being done a number of socially sustainable innovative living arrangements where future residents and end-users are at the table through in-depth participation processes (Innes & Booher, 2007; Rojs et al., 2019; Rojs, Hawlina, Gracner & Ramsak, 2019). Citizens in this participatory process have their needs communicated to urban practitioners and achieve benefits of enhanced social capital and adapt their living environment to contribute to the quality of life of the project (Qu and Hasselaar 2011 & Arnstein, 1969). While many recommend increasing stakeholder participation, it is not well understood what the perspective of the urban practitioner to this increased end-user participation. It is a question worth asking as urban practitioners have financial and technical expertise to direct urban planning development.

Today, issues related to urban development are no longer observed as simple and linear but more of a complex or a ‘wicked’ problem, since the initial problem defined in processes evolve as new possible solutions are considered or implemented (Rittel & Webber, 1984). New approaches are being developed due to sustainability concerns to incorporate collaboration and a network of stakeholders.

2 This is a response to the dissatisfaction on conventional participation methods and the neo-liberalist housing policy approaches since the 1990s (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011).

This conventional versus new models of participation have created a dynamic paradox and is demonstrated by the variation between concepts of ‘choice’ and ‘voice’ where conventional developments highlight ‘choice,’ or the ability individuals and households have to choose within the current market (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). Whereas for innovative living, the development process shifts towards a ‘voice’ for stakeholders to have the ability to influence plans and products, to be involved in the design and maintenance (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). But with this increased level and depth in stakeholder participation, the question remains:

How those who retain the financial resources and technical knowledge and thus are in a position of power and control, perceive this change in level and depth of end-user stakeholder participation (Taylor, 2000)?

Urban practitioners, considered one group in a position of strength, have limited knowledge of local problems in comparison to the local population (Taylor, 2000). Thus the main aim of the process of urban development is to assist in the decision-making process to achieve the ultimate goal of creating liveable urban areas (Enyedi, 2004).

Innovations of living, both old and new, have been observed to return democratic principles, social justice and empower long-term residents of the community, producing a more resilient community and has improved the quality of life of the overall urban region (Ruiu, 2016). While this has been shown to be empirically true, this research is asking the question from the urban practitioners’ point of view if they view this added participation as valid. Namely, the authors are asking what is the practitioner's perception of increased stakeholder participation in the development process of innovative living solutions? This question is the central focus and will review perceptions from those who work in the Nordic cities of Copenhagen and Malmö. Interestingly, innovations of living is not a new concept in the Nordic nations (Eriksson, Glad & Johansson, 2015). The region has a rich history of creative solutions responding to various era-specific concerns and these innovations have incorporated a high level of end-user stakeholder participation in their processes (Eriksson et al., 2015).

1.1 Research Problem, Purpose, Aim & Research Question

The research problem revolves around the role of the end-user stakeholders in urban development and how their level of participation is perceived by urban practitioners. With specific emphasis on projects that focus on social sustainability. This participation is perceived as having both positive and negative attributes results in a conventional development process (Innes & Booher, 2007). The interplay, skills and roles of major stakeholders are often addressed in academic literature, but not from the viewpoint of the practitioner (Curry, 2012; Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). This coupled with the proposed theoretical research incorporating stakeholder theory, power-sharing, and organisation learning, creates a timely investigation into these interconnected concepts. The tension that requires clarification is between the perceptions of practitioners on the value-added of end-user stakeholder participation in defined innovations of living where social sustainability is a key element. The aim of this paper is:

3 To further understand how urban practitioners perceive end-user stakeholder participation

in the process of innovations of living.

There is research on the overall topic of stakeholder participation in a conventional and socially sustainable development. This research aims to address this research gap on perceptions of urban practitioners in this growing segment of urban development. This will be asked through the three research questions that guide this paper:

What is the perception of urban practitioners towards end-user stakeholder participation within the process of development of innovative living?;

What is the perception regarding the distribution of power between stakeholders within the development process and how does it affect end-user stakeholder participation?; and What is the opinion of urban practitioners on end-user stakeholder participation to their

organisational learning and adaptability?

To provide insight on these research questions, the paper will focus on new emerging innovations of living projects and urban practitioners in cities Malmö, Sweden and Copenhagen, Denmark. These cities have a rich history and emerging developments which have a particular focus on quality of life, social capital and innovation (Eriksson et al, 2015; Strand & Freeman, 2015).

These research questions are bounded by two parameters; first, the research looks into the perception of urban practitioners of end-user stakeholders in innovations of living, including current interpretations of co-housing, shared housing, cooperatives and similar initiatives. Secondly, while selected examples and academic texts from international sources are used, the research in this paper is focused on the cities of Malmö and Copenhagen, the two largest cities in the Öresund region and work in different national policy contexts.

1.2 Core Concepts: Explanation

While a number of terms are provided in the glossary, core concepts central to the research need to be clarified, including innovations of living, end-user stakeholder, urban practitioners and perception. First, the authors have chosen to use the term ‘innovations of living’ as the key term encompassing the housing concepts related to social innovation. With numerous concepts of co-housing, shared housing, cooperatives and with these developments occurring at the building-scale to neighbourhood or district scale, a new term was devised to define these projects. The authors suggest this term to encompass these terms to provide clarity from the potentially ambiguous term of community - a term with multiple meanings (Ruiu, 2016; Curry 2012). However, the word ‘community’ will still be present in this document as many scholars use this term.

Second, the ‘end-user stakeholder’ refers to those individuals and/or organisations that will occupy, reside and use the completed innovation of living project (Eriksson et al., 2014). The term end-user is used in this paper as it is defined in the Swedish context to include those who use the buildings in addition to owner and residents (Eriksson et al., 2014). These stakeholders have a vested interest and are likely to be engaged in the development process to a higher level than conventional development procedures (Enyedi, 2004). Also:

4 “stakeholders are distinguished from other affected interested parties in having both: the

means of bringing attention to their needs; and the ability to take action if those needs are not met.” (Foley, 2005, in Garvare, 2010, p. 738).

Thirdly, urban practitioners are defined as those individuals working the urban development industry in some capacity. They are key stakeholders in the development of urban projects and have the technical knowledge and financial resources to implement new projects (Innes & Booher, 2007; Taylor, 2000). All urban practitioners that have been chosen to interview are currently involved in urban development. They have experience on innovations of living and/or have knowledge about end-user stakeholder engagement in innovations of living from previous or current projects. Although found in the private sector, their roles and responsibilities vary greatly and cross numerous professions. This includes, but not restricted to, urban planners, architects, project managers, consultants, and real estate developers.

Finally, perception is the key concept of study in this research. Largely associated with psychology, the term has expanded to other professionals including business and social science (Smith & Shinebourne, 2012). As defined by Given (2008) perception is:

“a mode of apprehending reality and experience through the senses, thus enabling discernment of figure, form, language, behaviour, and action. Individual perception influences opinion, judgment, understanding of a situation or person, meaning of an experience, and how one responds to a situation” (Given, 2008, p. 606).

1.3 Structure of Paper

The structure of the rest of the paper begins with Section 2.0 Background, with a brief history on socially innovative housing developments in the Swedish and Danish context. This is followed by selected examples of living innovation from around Europe and continues with a review of previous findings from academic literature related to this research. Section 3.0 outlines the theoretical framework model of stakeholder theory, power, organisational learning and adaptability. Section 4.0 reviews methodology and methods. Sections 5.0 and 6.0 describe our research findings, followed by an analysis of the findings and discussion that combines the findings with the research questions and the theoretical framework. Section 7.0 provides concluding statements and recommendations for further study.

2.0 Background

This section provides some background on the main concepts of perception of urban practitioners, stakeholder participation and innovations of living. It is provided through a brief historical review of innovations of living in the Swedish and Danish context, selected examples of innovations of living projects highlighting participatory approaches and continues with a discussion on previous research in the field related to a number of thematic areas.

5

2.1 Innovations of Living: History and Current Projects

Innovations of living has a rich history in both Denmark and Sweden. In different periods from the mid-19th to 21st Century, living habits of people have changed depending on various circumstances. Below, significant milestones in living innovation are discussed within Denmark and Sweden.

Denmark

In the mid-19th Century in Denmark, living conditions of most people were poor and unsanitary leading to the spread of numerous infectious diseases. To improve these living conditions, people started ‘building societies’ (called Byggeforeneing in Danish) as early as 1856 (Andelsboligens historie, 2015). These functioned with each member paying a set monthly fee, and as the buildings were constructed, the potential residents of these apartments were chosen through a ballot system. Once chosen, you had the opportunity to purchase your own apartment.

Prior to the establishment of building societies, the working class did not have the possibility to own their home, consequently, building societies became popular. These societies were the predecessor to the cooperative (called Andelsbolig in Danish) and were based on the same principles as the 1850s Building Societies. The first cooperative was founded in 1912 and spread across Denmark and continued in popularity through the 1930s and 1940s (Andelsboligens historie, 2015).

The modern version of cooperatives have transformed into co-housing. These were established in 1970s Copenhagen and are due to the interest the idea of shared or co-housing which offer small private areas with large public/shared spaces (Andelsboligens historie, 2015).

Sweden

In the 1930s, Sweden had major social issues primarily with housing. Standards were substandard and people suffered from poor housing conditions. Social politics focused on livability and pushed politicians to open the door to social reforms that would foster the development of quality housing. The Swedish prime-minister, Per Albin Hansson, proposed the term folkhemmet, or in English “The people’s home,” a term for a “society that is for everybody.” This was to give everyone in Sweden a safe foundation of living (Björkman, 2019). In coherence with this, architects were to plan and build better homes for the modern family. The conceptual ideas were founded by family sociologists who had knowledge about the family unit and their living habits.

Places were planned for modernity so that people and families could live together but have their own home and space. To create a larger social security net to improve the quality of life, responsibility was shared in a development area. Alva Myrdal, a sociologist of importance in Swedish society, created the concept of housing where local services were located on the ground floor such as a house restaurant and kindergarten (Björkman, 2019; Markeliushuset, 2020). This became beneficial for single mothers, and other families, who now could balance full-time work and family.

In Sweden, as in Denmark, cooperatives grew later in the 1900s. The Swedish ‘kollektivhus’ date back from the 1980s but in recent years have seen new developments and within cities with housing supply shortages. Compared to their conventional housing counterparts, these developments have always had a higher standard of environmental and social sustainability as these innovations of living worked by connecting people through sharing economy concepts (Björkman, 2019).

6 Market driven housing in Denmark and Sweden

Beginning in the 1990s, the housing market became more privatised. Market drivers were primarily high levels of urbanisation leading to a high demand for housing that has been provided by the private market and large scale housing associations (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). This has led to a seller’s market and housing becoming financial assets rather than a residence. This private market dominance meant that innovations of living stagnated due to the high demand and rapid need for housing and therefore, housing units would be sold even if not considered an optimal way of living for the consumers (Andersson & Turner, 2014; Qu & Hasselaar, 2011).

Present time and future - Denmark and Sweden

Today we are also in a time of change. Cities are getting larger and denser due to the rapid urbanisation, a phenomenon also happening in Denmark and Sweden (2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects, 2018). At the same time, the housing industry has become very aware of the need to become more sustainable. Not just environmentally sustainable but also social sustainability as living patterns are constantly changing and becoming more specialized (Abelairas-Etxebarria & Astorkiza, 2020). Living patterns today call for more attention to emerging health issues, such as loneliness in cities, a growing issue that could be mitigated through improved design of homes and cities that fosters social sustainability (Enyedi, 2004; Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). These sustainability-related drivers are currently pushing the agenda of innovations of living. There is a demand to think and act in new ways to meet the needs of people living in our cities (Rojs et al., 2020).

2.2 Innovations of Living: End-user Participation in Selected Examples

Modern innovations of living examples from around Europe showcase projects such as co-housing, sharing, and collective living concepts. These examples also provide a variety of end-user stakeholder participation methods. This includes examples from the Netherlands and Germany, two countries with a rich history with socially innovative projects. These projects, built since the year 2000, provide a showcase of the project typologies that qualify as innovations of living concepts (Figure 1). These are considered experimental with very different local governance systems and decision-making stakeholders in their respective location (Primoz, 2017). They range from a small housing projects (R50, Berlin, Germany & Vrijburcht, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) to larger housing complexes (Embassy of Sharing, Malmö, Sweden; Cph Village, and Lange Eng both in Copenhagen, Denmark) to large neighbourhood or district scale projects (Sege Park, Malmö, Sweden & Vauban, Freiburg, Germany) encompassing a large physical area and population.

In the examples mentioned above, there has been an increase in the level and depth of end-user participation beyond what is mandated by municipal institutions. For smaller projects such as R50, the design has been based on the resident’s aspirations for collective and affordable living and was developed through collaborative efforts with multiple stakeholder consultations and discussions (SPACE10, 2018). The Vrijburcht project in Amsterdam, created Foundation Vrijburcht after an initial design phase, where Foundation board members were project participants that included future residents, and acted as clients for the urban practitioners involved. The Board oversaw the planning process, the financing and the sale of homes. Financial support was provided by a housing association and became a part-owner of the development upon completion (Hulsbergen & Stouten, 2011). Similarly in Lange-Eng, the end-user participation process began as a bottom-up initiative in 2004 and the development process was led by a coalition of future residents, who brought in technical expertise

7 (lawyers, architects, municipal officials) where required (Lange Eng, 2020). The neighbourhood houses approximately 200 people and is owned and operated by the residents (Lange Eng, 2020).

Figure 1: Photos of Current and Recent Innovative of Living Projects. Top Left: Lange Eng co-housing project in Copenhagen, Denmark (Lange Eng, 2020); Top Right: Copenhagen Village (Copenhagen Village, 2020); Bottom Right: Streetscape from Vauban, Freiburg, Germany (City of Freiburg, 2015); Bottom Left: winning proposal of “it takes a block” for Sege Park, Malmö, Sweden (City of Malmö, 2017).

In Malmö, two projects show a work in progress. Sege Park, a variety of housing typologies built by multiple developers will populate the site. This includes those embedded with sharing economy principles such as co-housing cooperatives who have been a stakeholder in the design and planning process from the early stages. The vision for another project, the Embassy of Sharing, encourages innovation, collaboration, knowledge exchange and inspiration (Midroc, 2020). The proposal includes numerous social components including elderly and student housing, incubator and small business spaces plus multi-use rooms. The stakeholder participation component for the project has yet to be fully defined (Midroc, 2020). Another example of stakeholder participation is in the planning and on-going execution of a project. At Cph Village, end-users were not formally part of the development process. Residents are chosen through an application process based partially on interest in sustainability, their connection to the neighbourhood values of sharing, living small, getting to know your neighbours, joining a club and reducing your environmental footprint (Cph Village, 2020).

8

Figure 2: Vauban’s Local Governance Structure (Primoz, 2017).

The Vauban project in Freiburg, was led by the local authorities who supported the city’s green agenda and a citizen-led group, Forum Vauban, was funded by local authorities became a partner in shaping the housing and sustainability principles after initially being left out of the process (Kasioumi, 2011). Ecological and social principles were embedded in the planning process and private building groups and cooperative residential projects were favoured over conventional large developers and investors (City of Freiburg, 2015). The process has built up a network of stakeholders, which form a unique and somewhat complex local governance system as seen in Figure 2. Vauban’s local governance system, which encompasses many different stakeholders, has empowered local citizens.

2.3 Previous Research: Literature

Previous literature is explored in detail and articles provide an overview of academic articles and are combined into three general topics (see Appendix A). The articles under review in this section are organised by individual themes is then followed by a summary of the main findings. Themes discussed include perception of stakeholders; stakeholder participation; power, empowerment and sharing; organisational benefits, innovation and learning; and finally the area of urban resilience and sustainability.

2.3.1 Perception of Urban Practitioners

While few documents relate directly to the perception of urban practitioners, Curry (2012) and Qu and Hasselaar (2011), provide insight into perceptions of practitioners and document their reasoning for end-user participation in developing innovative living concepts. Focusing on conventional developments in the United Kingdom, Curry (2012) states that previous literature suggests that stakeholder participation is perceived as “time-consuming, costly, unwieldy, chaotic and unproductive. The authors’ survey of UK practitioners showed otherwise and suggests that perceptions of inequity in community participation in spatial planning are not as stark as the literature posits” (Curry, 2012, p. 350). This is reiterated by Eriksson, Glad and Johansson (2015) who suggest many negative concerns with stakeholder participation by urban practitioners but conclude that these individuals overall observe the need and benefit of stakeholder partnerships in the urban development process. Qu and Hasselaar

9 (2011) suggest the same in co-housing initiatives that will require a change in roles from practitioners and their perceptions to promote innovation, inclusion and capacity building within communities. Tummers (2011) and Hasselaar (2011) agree that the main barriers for community partnerships are the power and role of project developers and their perception that the community lacks the necessary capacity:

“Participation, for that reason, seems not obstructed by lack of interest from the side of consumers, rather lack of perspective from the planners and project developers” (Tummers, 2011, p. 94).

2.3.2 Stakeholder Participation

Since Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of citizen participation (Figure 3), the issue of stakeholder participation has long been of interest in the urban development field. This discussion has been related to conventional stakeholder participation and is well documented in academic articles and urban practitioner literature. This has continued today, coinciding with a push for stakeholder participation in new concepts for innovations of living within the framework of social, economic and environmental sustainability. Greater citizen participation empowers participants, especially in community building and building social capital (Rojs et al., 2020). Qu and Hasselaar (2011) paradoxically state that altering the planning process towards citizen participation leads to issues of society-level sustainability problems in which complexity and individualization are central themes but overall suggest that community participation is a system improvement.

10 Arnstein (1969), citing the lack of citizen participation in the development process, presented the ladder as a possible step in improving development through increased citizen participation for the end-user. The ladder is seen as a guide for observing the power structure when important decisions are being made and is continued to be used as a source today due to its basis in participatory planning (Qu and Hasselaar, 2011). As one moves up the ladder, greater the voice and power for citizens participating in the urban development process. As Arnstein states herself: “answer to the critical what question is simply that citizen participation is a categorical term for citizen power and the redistribution of power….and to be deliberately included in political and economic process and decision-making“ (Arnstein, 1969).

The compilation of Making Room for People: Choice, Voice, Livability in Residential Places edited by Qu and Hasselaar (2011) provides a comprehensive review in the Dutch context of established concepts of co-housing and citizen participation that is re-emerging as a response to standardized market housing. The report states that stakeholder participation needs to move from a limited, conventional and mandated approach to a required need for active participation to promote collective responsibility (Innes & Booher, 2007). This would move from the stakeholder being only considered consumers and having a ‘choice’ to become empowered citizens with a ‘voice’ (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). But barriers currently exist to respond to the needs of communities in the conventional planning process (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011). To achieve this transformation and include actual and perceived power, practitioners’ knowledge and municipal regulations need to transform to meet new collaborative efforts as mentioned by Enyedi (2004). Tummers (2011) in Qu and Hasselaar adds stakeholder roles in community development need to change to accommodate a variety of processes with active or proactive citizens (Curry, 2012). These projects are more complex with greater stakeholder participation, but will lead to positive impacts on sustainability (Curry, 2012).

Stakeholders in innovative housing processes provide numerous benefits due to their participatory, member-led approach which directly responds to members needs (Bulkeley, 2016). This fits larger societal trends of decentralisation, desire for participation and custom-made solutions (Tummers, 2016). For co-housing, there is a need for an equitable partnership between users and practitioners where these end-user partners are key primary stakeholders, but is dependent on practitioners' position in the process (Czischke 2018). This leads to a co-design process outlined by Nevens (2013) where the stakeholder is redefined and is given ‘real’ participation as a key stakeholder in the process (Kasioumi, 2011). Kasioumi (2011) continues that this is a crucial difference seen in the development of two urban areas of Vauban (Freiburg, Germany) and Hammarby Sjöstad (Stockholm, Sweden) in the realisation of social and environmental goals. This suggests that stakeholder participation requires a holistic, systematic approach and not just a conventional ‘window shopping’ arrangement (Martinez, 2015). Collaboration and proactive ideals are also suggested as necessary (Kasioumi, 2011, Chatterton, 2013).

Eriksson, Glad and Johansson (2015) provide a synopsis on the advantages and disadvantages of user involvement (see Table 1). They explain that user involvement in the development process has potential advantages, but also disadvantages that may be perceived as barriers by practitioners to instil deeper participatory efforts (Eriksson et al., 2015).

11 Table 1: Advantages and Disadvantages of User Involvement

Advantages Notes in between Disadvantages Satisfied customers/users (or

customers at all) Long-term Feel secure

Participation/answer to client needs Identify customer needs

Feeling of participation and influence

Regulations meet many of the demands of users

More specific demands require user involvement

Knowledge level among users Difficulties expressing demands / questions

Difficult to pose questions at the right time

Unrealistic expectations Somewhat difficult to take (everyone) into account More questions after

Too many options—lay person or expert?

The term user is seen as comparable to this paper’s definition of end-user stakeholder.

Source: Eriksson, J., Glad, W., & Johansson, M. (2015). User involvement in Swedish residential building projects: a stakeholder perspective. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 30(2), 313-329.

Two additional points related to stakeholder participation require explanation. One is the participation and role of public sector stakeholders. The municipality is seen as a key stakeholder and remains in control of the rules of participation related to partnerships procedures (Taylor, 2000). Multiple authors (Tummers in Qu, 2011; Czischke, 2018; Taylor, 2000) explain that it continues to be a barrier to innovation in the development process. They state the framework of local planning policies and governance structures create restrictions for co-housing initiatives and related housing developments to take hold. Promises from politicians often disagree with their actual intentions, an area for concern raised by Hasselaar (2011) for increased participation by end-user stakeholders.

Secondly, special consideration for the Scandinavian context should be highlighted. Strand and Freeman (2014) discussion on stakeholder theory in the Scandinavian context provides a cultural backdrop showing the emergence of cooperation over competition and the concept of shared value creation is a key in Swedish society (Strand & Freeman, 2014). The article discusses strategic management in private firms, and the dichotomy of competition versus cooperation (Strand & Freeman, 2014). Traditionally, organisations have taken an insular approach and have been largely concerned with short-term economic gains and have missed the opportunities of developing long-term shared value with a larger array of stakeholders (Strand & Freeman, 2014). The GLOBE Culture, Leadership, and Organisations study reiterates the cultural hypothesis that Scandinavian societies place a high priority on long-term success and identifies with the broader society where rules, orderliness, and consistency are stressed (Northouse, 2015). Northouse (2015) continues power is shared equally among people at all levels of Scandinavian societies while cooperation and societal-level group identity are highly valued. In addition, ideal leadership is highly visionary and participative allowing others to participate in decision-making (Strand & Freeman, 2014).

2.3.3 Power, Empowerment and Sharing

The interrelated subjects of power, empowerment and sharing relate to the distribution of resources between various stakeholders. This is detailed by Bulkeley (2016) and Curry (2010) as an uneven

12 distribution issue leading to one party controlling another stakeholder. Traditionally, end-user stakeholder positions in planning are weak despite a legal framework and need revision to accommodate stakeholders into the process (Tummers, 2016). Chatterton (2013) and Bulkeley (2016) echo this with the need to change how the social and political systems are designed, managed and delivered. While Taylor (2000) is pessimistic of practitioners and the public sector in their ability to change and empower end-user stakeholders. Empowerment of stakeholders, institutionalization of change and proactive government can also lead to transformational change and implementation of integrated goals of sustainable communities (Nevens, 2013 & Kasioumi, 2011 & Martinez, 2015). The empowerment ideal implies the need for trust in authorities by stakeholders, which is in deficit where power imbalances reside. Empowering and restoring the balance is possible through on-going and iterative participatory processes (Curry, 2010). This is echoed by Eriksson, Glad and Johansson (2015) where customers need a feeling of influence and satisfaction to produce positive results to social innovation. Martinez (2015) adds inadequate management to handle empowered stakeholders could lead to negative effects in the process. In addition, Taylor (2000) relays the concept of power is shifting from power rooted in a particular institution at local level to a more dispersed notion of power and authority. This power is based on pluralism and this is to accommodate the changing postmodern concept of power and empowerment.

Figure 4: New Ladder of Citizen Participation. Based on Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen influence, Qu and Hasselaar (2011) have interpreted in a new form for modern development initiatives to increase choice to voice. A participatory decision making process is necessary, leads to a solution that meets local demands, that could not be fully realised by regular approaches. This brings forms of collectivity and participation to the building/rebuilding of neighbourhoods, which may contribute to improving the level of social cohesion (Qu and Hasselaar, 2011).

Hasselaar and Qu (2011) discusses empowerment through a ‘choice’ versus ‘voice’ lens. Power is a framework constructed through a planning system that largely maintains power in the hands of conventional organisations (Hasselaar & Qu, 2011; Taylor, 2000). The concept of the participatory design process is beyond the mainstream developer and consequently, in some cases, co-housing projects are initiated by practitioners wanting to develop something different than private market housing (Hasselaar and Qu, 2011). Practitioners find that roles and influence change in these new processes where the citizen is empowered but the process requires a mix of bottom-up and top-down

13 initiatives and partnerships (Taylor, 2000; Tummers, 2011). Their interpretation of the relationship between citizen participation and empowerment in the development process is based on the work of Arnstein (1969) in Figure 4 and suggests a direct correlation in levels of participation and the degree of empowerment for citizens (Hasselaar and Qu, 2011).

2.3.4 Organisational Learning, Innovation and Benefits

McCormick (2013) and Bulkeley (2016) suggest real-world experimentation in urban development increases problem-solving capacities, learning and the potential alternative creation for organisations. Chatterton (2013) explains organisations involved in innovative housing challenge conventional policy while Bulkeley (2016) and Eriksson, Glad and Johansson (2015) state processes that provide the opportunity to go beyond ‘business as usual’ are also beneficial to stakeholders involved. Innovation leading to societal change and scaling-up potential are possible (Tummers, 2016, Nevens, 2013, McCormick, 2013). Interestingly, Chatterton (2013) raises the long history and traditions related to cooperative housing models and how we can rethink current housing issues. Multiple articles argue the concept of innovative housing and stakeholder participation has a rich history, but these innovations are difficult under today's planning systems (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011, Enyedi, 2004). Financial benefits of stakeholder participation are a key point by Hasselaar (2011) suggesting that initial planning efforts may require greater initial and continuous efforts, but can be rewarding. The author explains:

“This enhanced cooperation that introduces residents as actors within the process may even reduce the financial risk for project developers. In other words: risk is taken by more people, even when their societal position is relatively weak. Again, this is a matter of taking the voice position of users rather than looking at profit from the perspective of the developer alone” (Tummers, 2011, p. 181).

Czischke (2018) whose detailed analysis relates to a review of co-housing in Austria and France, discusses learning and the value to organisations in urban development. Overall, Czischke (2018) states housing providers with “an ethos akin to initiators values will more likely become (and stay) involved in collaborative housing, as compared to mainstream providers” (Czischke, 2018, p. 55) Practitioners are observed as re-learning previously used concepts in housing and community development but also learning new competencies and skills including the inclusion of public participants. Czischke (2018) also remarks on the possible value for practitioners in co-housing production, strategically positioning themselves for long-term success in the field. There is a “need for training of professionals to engage effectively and constructively with the different types of knowledge and competences of residents as one of the key challenges for these initiatives” (Czischke, 2018, p. 77).

2.3.5 Urban Resilience and Sustainability

Urban resilience relate to ‘future-proofing’ a community from potential shocks and stresses and incorporating sustainability into development (Chatterton, 2013). Increased knowledge and participatory efforts by residents will directly affect the quality of the process and product outcome (Curry, 2012). Qu and Hasselaar (2011) raise perceptions and stakeholder participation will allow for great variety in approaches and built form to deal with changing demographics. The co-sharing development Lilac in the United Kingdom, Chatterton (2013) argues self-governing communities, moving from a household to community-level decision-making, add to resilience through intervention allowing for empowerment, local self-management, accountability and neighbourhood-level participation. The author adds results show improved levels of “economic equality among residents,

14 permanent affordability; plus, the de-marketization, non-speculation and mutual co-ownership of housing” (Chatterton, 2013, p. 1662).

Most authors agree that the process for housing innovation allows sustainable development principles to contribute to social change (Martinez, 2015). The difference is presented by Kasioumi (2011) with high-level social cohesion present in Vauban in comparison to Hammarby Sjöstad due to its deep bottom-up stakeholder involvement. Tummers (2016) and Chatterton (2013) also show communities have higher acceptance, social interaction and life in the community. A number of concerns are raised including potential for gentrification, commodification of housing and top-down structures stifling innovation related to exclusivity of co-housing (Tummers, 2016). Inadequate management could lead to controversy and poor results (Martinez, 2015). Kasioumi (2011) suggests the replicability of these projects may not be possible unless the potential population is homogeneous, open to flexibility and collaboration. The term co-housing itself is also seen as confusing and generic as many use the term interchangeably regarding various housing innovations (Tummers, 2016).

2.4 Summary

“Communities are best placed to know what they want”....”once people had become familiar with the planning system, they took a genuine interest in the community benefits that the system could bring” (Curry, 2012, p. 360).

There is a considerable amount of research on stakeholder participation in the urban planning process, including projects that would be considered sustainable in nature. The academic research generally suggests the positive useful nature of stakeholder participation in urban development with some criticisms and concerns. Limited research was discovered on how urban practitioners perceive this suggested increase in end-user stakeholder participation. Specific examples and case studies showcase that living innovation is possible with a change in mindset Evidence suggests the potential for organisations to benefit financially while developing social attributes in innovations of living. Based on the current research, this paper explores the research gap in the perception of urban practitioners in the chosen context of the cities of Copenhagen and Malmö.

3.0 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of the urban practitioner perception on stakeholder participation is presented to explain the data and respond to the research questions. The theoretical framework is outlined by three concepts of stakeholder theory and shared value creation; power: empowerment and sharing concepts; and learning and adaptive organisations. A summary of these theories along with a proposed conceptual model and hypothesis related to this research paper ends this section.

3.1 Stakeholder Theory, Participation and Shared Value Creation

Within business and organisational literature, stakeholder theory is a model that looks beyond the narrow definition of the organisation as an economic entity solely for the benefits of shareholders (Porter, 1985). Freeman’s (1984) widely used definition of the term stakeholder is a group or individual

15 who can affect or is affected by fulfillment of an organisation’s objectives. The theory rejects the narrow definition of a firm's purpose and is largely based on three ideas of jointness of interest, a cooperative strategic posture and shared value creation (Strand & Freeman, 2014). Stakeholder theory changes the vision from a short-term competitive, economic value to long-term cooperative, or shared value which becomes the focus of an organisation (Freeman, 1984).

Stakeholder theory recognizes that different sets of people contributing are important for the organisation as they have various objectives that are recognized (Donaldson and Preston 1995). Zamuto (1982) states that relative power and the importance of different stakeholders will change over time and that their preferences may change. This provides a direct link to organisational change, the need for changing perceptions of relative power through learning capacities in the organisation (Zamuto, 1982; and see Figure 5).

Companies that recognize the value stakeholder interests, continuously build relationships in an effort to create value for more stakeholders. The result is a competitive advantage that achieves an advantage moving from an internal shareholder to an external stakeholder model (Strand & Freeman, 2013). Strand and Freeman (2013) state shared value through cooperation is required for environmental and social sustainability. Conventional narrow economic definition of shareholders cannot incorporate the expanded notion of sustainability frameworks and growing complexity (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011; Rittel & Webber, 1984).

Stakeholder theory is relevant for the urban development organisational theory perspective for its value to the organisation, when the organisation accommodates demands of its stakeholders (Garvare, 2010; Senge, 2000). According to Garvare (2010) traditional organisational constructs present in urban development are unsustainable for long-term organisational health due to the temporal gap between short-term and long-term thinking and behaviour. This premise is valid for practitioners in urban development and their difficulties in changing established organisational behaviours to accommodate stakeholders (Taylor, 2000).

3.2 Power: Empowerment and Sharing Concepts

Organisational power, empowerment and sharing of power also helps explain the theoretical framework. Power is based on long-standing leadership and organisational concepts related to the ownership of desired resources and knowledge (Taylor, 2000). Theories on power concentration have challenged this ‘top-down’ construct, with evidence outlining collaborative processes related to power-sharing are beneficial for stakeholders and the organisation (Weber, 1947; Tolbert & Hall, 2009). Shifts in power do not occur rapidly as those in power desire to remain in power (Taylor, 2000). In addition, allocated financial, procedures and human resources are difficult to alter expeditiously to change established power dynamics (Tolbert & Hall, 2009).

Problems related to sustainability increases complexity in organisations and therefore sharing proper knowledge and skills that include an expanded network of stakeholders improves organisational performance (Qu & Hasselaar, 2011; Rittel & Webber, 1984). Stakeholder theory states the need for an expanded view of power to empower those who are affected by the decisions of an organisation (Taylor, 2000). In the urban development industry, this is exemplified by the empowerment of end-user stakeholders (Qu and Hasselaar, 2011), between traditional ‘choice’ of a conventional consumer

16 to having a ‘voice’. This is defined as empowering end-user stakeholder in an active partnership role during the development process. Active participation currently occurs in some urban projects and is integral to the sharing of power. This concept is a key part of this research model outlined in Section 3.4, where participation builds empowerment leading to greater learning and adaptability of an organisation (Angotti, 2008; Arnstein, 1969; Taylor, 2000).

Power and resource ownership are significant barriers in the empowerment of external stakeholders and in urban development, the project manager (an urban practitioner) is observed as a main barrier to change (Tummers, 2011). This power imbalance and lack of knowledge from end-user stakeholders, delivers products to the end-user of substandard quality and lowers livability (Hasselaar, 2011). Additionally, difficulties in sharing power are embedded in organisational structures and procedures both internal and external to the organisation in question (Enyedi, 2004). Politics and public organisations have a disconnect between rhetoric and intentions, with frameworks laid out for procedures and projects reflecting current power relationships and not emerging theory and concepts (Curry, 2012; Innis & Booher, 2007). The rules of participation and relationships between power and partnerships are firmly controlled by the public sector (Taylor, 2000). These rules and regulations are embedded in the community institutions themselves and influence other public sector entities compounding the difficulty of establishing change in any public sector process (Taylor, 2000).

Shared power is a competitive advantage and not a loss of power or a disadvantage for the organisations and is part of this paper’s hypothesis (Enyedi 2004; Innis & Booher, 2007). The discourse of urban planning is moving from power rooted in institutions to a more dispersed notion of power and authority based on pluralism through greater stakeholder participation (Innis & Booher, 2007). This is a key consideration in the path to adaptive organisations and is incorporated in the theoretical model found in Section 3.4.

3.3 Adaptive Organisations & Learning Frameworks

Change within organisations requires new learning frameworks. This is defined as the process of learning, retaining and transferring knowledge in continuous improvement to gain experience and knowledge (Tolbert & Hall, 2015). Child and Kieser (1981) summarize the learning and adaptability as:

“Organisations are constantly changing. Movements in external conditions such as competition, innovation, public demand, and governmental policy require that new strategies, methods of working, and outputs be devised for an organisation merely to continue at its present level of operations. Internal factors also promote change in that managers and other members of an organisation may seek not just its maintenance but also its growth.” (Child and Kieser, 1981, as cited in Tolbert & Hall, 2015, p. 198).

Multi-loop learning framework, by Argyris and Schon (1974), is a theoretical contribution that addresses the level and depth of organisational learning, especially in environments of significant disruption and uncertainty. Managing social change requires a change in understanding, behaviours and perceptions with individuals and stakeholders involved (Medema et al., 2014; Romme & Van Witteloostuijn 1999). This ideal integrates into the theoretical model in Section 3.4 as it concerns uncertainty and change with the innovations of living concept. The multi-loop framework outlines three levels of learning capabilities (Medema et al., 2014; Pahl-Wostl, 2009). Single-loop learning asks

17 questions of following the rules (incremental change), double-loop learning looks at challenging key assumptions and relationships (reframing the question), while triple-loop learning reviews the learning process (transformational change) (Medema et al., 2014). Some organisations understand the need for adaptive or transformation change to adapt, develop double- and triple-loop learning capabilities to promote new learning capacity (Pahl-Wostl, 2009).

There are a number of obstacles to organisational learning for urban practitioners. This includes an organisation’s preference for stability, routine programs, and internal structures which perpetuates existing programs. Senge (1990) outlines the underlying differences in adaptive or incremental learning (change within current frameworks) versus in generative learning (new ways of looking at the world), an apt comparison to the difference between double- and triple-loop learning. This is a critical component of leadership and organisations characteristics in the development of new procedures and ideas (Senge 1990). This a consideration in urban development as the industry is risk-averse and conservative in its nature and thus adding to difficulties for fundamental learning and change (Innis & Booher, 2007).

Adaptive organisations learn and produce transformative change in response to dynamic situations and environments to understand the behaviours of individuals (Northouse, 2015). Prescriptive, systematic and process-based, adaptive organisations deal with challenges that alter people’s assumptions, perceptions, beliefs and attitudes (Northouse, 2015). Therefore, it requires an openness to new thinking, including adapting to needs of stakeholders affected by change, internal and external to these organisations (Eriksson et al., 2015).

Transformational change within urban practitioner organisations is complex and finds resistance by many in players in the development process (Innis & Booher, 2007). This is particularly evident with very small organisations which lack the resources for transformational change. Large-scale organisations, on the other hand, have resources allotted to current infrastructure making large transformative changes difficult (Tolbert & Hall, 2015). Their resistance to change also lies in their power and dominant functions leading to an urban development industry that is conservative. Organisations focused only on adaptation and incremental change reduce their potential long-term change (Senge, 2005, Pahl-Wostl, 2009). Adoption, also known as generative learning, may be required to develop an organisational structure to correspond to complex problems rather than fitting innovation and change into current leadership and organisational structures (Senge, 2005). In the theoretical framework for the research on urban practitioners’ perception of end-user stakeholders, learning and adaptation of organisations are the result of enhanced participation and empowerment of stakeholders and is further explained below.

3.4 Framework Summary and Connection to Research

The conceptual theoretical framework consists of three components discussed in this section and their relationship from the urban practitioners perspective (Figure 5). It lays the foundational component for how urban practitioners perceive end-user stakeholder participation in innovations of living projects. This concept is based on the hypothesis that stakeholder participation leads to greater levels of power and empowerment for all participants, including the urban practitioners and their respective organisations. The framework suggests a non-linear framework, moving away from a linear approach associated with conventional urban development.

18

Figure 5: Conceptual Theoretical Framework from the urban practitioners perspective (source: authors)

Specifically, the framework begins with stakeholder theory, which suggests increasing the participation and knowledge sharing between various participants in the development process leading to shared value. This cooperation between urban practitioners and end-user stakeholders creates shared value through trust transitioning from a ‘choice’ to ‘voice’ position which subsequently leads to a higher standard in process and delivery in innovations of living (Qu and Hasselaar, 2011). The conceptual model allows for greater sharing of power for participants through the initial sharing of ideas and living requirements as a component of living innovations (Qu and Hasselaar, 2011). With the need for social sustainability in urban settings and the potential of building long-term value, empowerment and sharing power with non-traditional end-user stakeholders has become a valuable source of knowledge (Tummers, 2011). From the urban practitioners’ perspective, this integrated participation of stakeholders leads to empowerment and organisational learning. This allows the organisation to adapt and learn continuously by comprehending the local market and of potential end-users lead to greater innovation and adaptability (Qu and Hasselaar, 2011 & Senge, 2000). This will improve the ability of urban practitioners to respond to future system changes and demands in the housing market as there is no clear template on a standard process of delivery (Curry, 2012; Innes & Booher, 2007). In the theoretical framework, the concept of continuous learning by urban practitioners is hypothesised through the feedback loop organisational perspective back to stakeholder and participation (represented by the dotted line in Figure 5). If this hypothesis holds true, it will allow for the explanation and understanding how urban practitioners perceive end-user stakeholder participation.

4.0 Methodology and Methods

As a relatively new area of research and the method of in-depth semi-structured interviews, they lead to an inductive exploratory research design based on an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) approach. Borrowing from psychology and the medical field, this qualitative methodological approach has seen expanded use into fields of social sciences, business and organisational studies (Smith et al., 2012). IPA is an inductive qualitative research approach committed to the examination of how people make sense of their major life experiences. It is concerned with exploring individual

19 experiences in their own terms (Pietkiewicz, 2014). IPA research is especially interested in what happens when the everyday flow of lived experience takes on a particular significance for people and their perceptions (Smith et al., 2012).

IPA is based on three principles of phenomenology, hermeneutics, and idiography and are the fundamental components of this research methodology (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin 2009). Phenomenology revolves on the way things appear to the experience of individuals or aims at identifying the key attributes of unique experiences (Pietkiewicz, 2014). Studies based on phenomenology, therefore, focus on perceptions of individuals related to events and not through preconceived notions or scientific or categorical systems (Pietkiewicz, 2014). The second principle, hermeneutics, or the Greek word ‘to interpret’, relates to the interpretation of an individual’s experiences (Freeman, 2008). The gathering of information is a dynamic process insofar the researcher is active in accessing the interviewees’ personal experiences and making sense of the information from their perspective while remaining critical (Pietkiewicz, 2014). The third principle of idiography describes the detailed review and in-depth analysis of each specific case before any general statement is developed (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin 2009). While similarities and themes are developed through the IPA approach, anomalies are also considered valuable and provide an increased richness in data collection process and analysis (Pietkiewicz, 2014).

Data analysis in the IPA method is unique compared to other approaches as the research focuses on particular and specific findings (Pietkiewicz, 2014). First-person in-depth interviews from a small sample group is a standard approach to develop a deeper understanding of participants' experiences (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin 2009). It also aims at generating rich and detailed descriptions of how individuals experience phenomena under investigation. (Pietkiewicz, 2014). Data gathered from these interviews is then analyzed and interpreted by placing the researcher ‘in the shoes’ of the interviewee (Smith et al., 2012). This analysis occurs through an appropriate set of adaptable flexible guidelines established by researchers related to their research objective (Pietkiewicz, 2014).

The methodological framework fits into the research aims and questions of this paper, as it is related to perceptions. The interviewees in this research on urban practitioners’ perceptions are involved at different stages of the development process. This allows for an in-depth analysis of experiences and perceptions from their unique perspective (Pietkiewicz, 2014). Urban development is highly institutionalized and follows set procedures but what is less evident is how multiple stakeholders interpret this process. By reviewing perceptions of urban practitioners and interpreting these detailed experiences using IPA allows further understanding in the development process for innovations of living.

This establishes the methodological approach for the study of practitioners perceptions of end-user stakeholder participation. Data is collected by open-ended semi-structured interviews from a small sample group of urban practitioners who are employed in the cities of Malmö and Copenhagen (see Table 3). There is some variance in the interviewees, based on their organisational focus and occupation, but all interviewees work in the private sector, allowing for a divergence and convergence of interviewee experiences (Barriball and While, 1994). Interviews are coded, then systematically analyzed and using hermeneutics outlined in the IPA approach. The researchers then interpret the primary data from the practitioners’ interviews to develop themes, narratives, and unique experiences in detail (Smith et al., 2012). Finally, the interviewee responses are interpreted to understand the meaning and perceptions behind their experiences. These findings are related back to existing academic knowledge for analysis (Smith & Shinebourne, 2012).

20

4.1 Practitioner Interviews

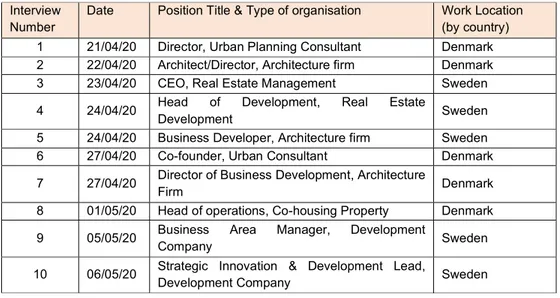

Semi-structured interviews were chosen as our primary mode of data collection to respond to the outlined purpose, aim and research questions in this paper. A total of 10 semi-structured interviews were held in April and May 2020 with practitioners from Malmö and Copenhagen and who are normally based in Sweden and Denmark. Chosen interviewees were recruited through established industry contacts and networking with colleagues. These participants work in the private sector, knowledgeable of the innovations of living concept, and have experience with end-user stakeholders participation in urban development. Interviews were held online through the Zoom online application and were conducted and transcribed in English with both authors in attendance. Table 2 provides an overview of the interviewees professions and employment location.

Table 2: Interviewees: Professions and Work Locations

Interview Number

Date Position Title & Type of organisation Work Location (by country) 1 21/04/20 Director, Urban Planning Consultant Denmark 2 22/04/20 Architect/Director, Architecture firm Denmark 3 23/04/20 CEO, Real Estate Management Sweden 4 24/04/20 Head of Development, Real Estate

Development Sweden 5 24/04/20 Business Developer, Architecture firm Sweden 6 27/04/20 Co-founder, Urban Consultant Denmark 7 27/04/20 Director of Business Development, Architecture

Firm Denmark

8 01/05/20 Head of operations, Co-housing Property Denmark 9 05/05/20 Business Area Manager, Development

Company Sweden

10 06/05/20 Strategic Innovation & Development Lead,

Development Company Sweden

Once an interviewee agreed to an interview, they were provided with a one-page brief in advance outlining our subject area, interview process structure and some general questions to guide the interview (see Appendix B). In most cases, the outline was read by the interviewees prior to the appointment while others reviewed the document during the interview. Interviewees were then reminded and provided authorization that interviews and answers for this research will remain confidential and anonymous for the duration of the research process. Providing the interviewee questions in advance may be considered an unorthodox approach to normal data gathering procedures. This could lead to pre-formulated or biased responses, but the authors believe that this was required to clarify the topic (Mack, 2005). The document provides an explanation on the nature of our project, particularly on perceptions of end-user stakeholders, a detailed area within the development process (Turner, 2010). While a series of questions was listed, they were used as the starting point for the interview and permitted the authors to be flexible during the interviews. Once interviews were complete, each interview was transcribed using a combination of online transcribing services and individual revisions by the researchers.