Technology,

innovation

and

knowledge:

The

importance

of

ideas

and

international

connectivity

Ulf

Andersson

a,b,

A`ngels

Dası´

c,

Ram

Mudambi

d,*

,

Torben

Pedersen

eaMala¨rdalenUnversity,SchoolofBusiness,SocietyandEngineering,Box883,SE-72123Va¨stera˚s,Sweden

b

BINorwegianSchoolofBusiness,DepartmentofStrategy,N-0442Oslo,Norway

c

UniversityofValencia,FacultyofEconomics,Avd.Tarongers,s/n,46022Valencia,Spain

d

TempleUniversity,FoxSchoolofBusiness,PA19122Philadelphia,USA

e

BocconiUniversity,DepartmentofManagementandTechnology,ViaRo¨ntgen,1,20136Milan,Italy

1. Introduction

The importance of ideas and creativity in value creation processesisdramaticallyincreasingandtheyareattheheartof business. Investments in human capital, machinery and infra-structureareallveryimportantingredients,butitistheideasof whereandhowtousethemthatarekeytothedevelopmentand growth of businesses. The global context with its diverse knowledgepoolsandclustersprovidesbothvaluablesourcesfor newknowledgeandalsooutletsforleveraginginnovationwhen sellingthenewoutputsinawiderangeofmarkets.

Over the years the importance of ideas for international business (IB) has been captured in different concepts like technology,innovationandknowledge.Thefocal conceptshave evolvedovertime,butthekeypointthattheideasarecentralforIB remainsassincereasever.Infact,thepossessionand internaliza-tionofintangiblesintheformofownershipadvantagesconstitutes

the main explanation for the existence of multinationals (e.g.

Buckley&Casson,1976;Dunning,1993).MorckandYeung(1991)

demonstratedthatonlymultinationalswithsubstantialR&Dand marketing intangibles were valued at a premium over purely domesticfirms.Recentestimatesdemonstratethatwelloverthree quarters of thevalue ofpublicly traded firms canbe tracedto intangibles(Mudambi,2008).

Much has been written about technology, innovation and knowledgeinaninternationalcontext.Certainly,theliterature hasmaturedtoa pointwherewe haveseennumerousreview papersandmeta-analysesontheseissues(e.g.Alavi&Leidner, 2001;Wijk,Jansen,&Lyles,2008;Michailova&Mustaffa,2012). This paper is an attemptto take stock of what we in the IB scholarlycommunityknowaboutideasandcreativity,theroleof Journal ofWorld Business(JWB)inthisliteratureandtooffera research agenda for the coming decade. With this aim, we documentthe development ofthese issuesin theIBliterature mainlyonthebasisofarticlespublishedinJWB,andthenwewill reflectoninsightsfromthevastliteratureandpointatareasfor futureresearch.

Technology, Innovation and Knowledge are three related phenomena and concepts that have been at the core of the worldwide economy evolution and the international business

ARTICLE INFO

Articlehistory:

Availableonline13September2015

Keywords: Technology Innovation Knowledge Sourcing Internaltransfer Externaltransfer Integration ABSTRACT

TherelevanceofideasisatthecoreoftheIBfieldandhasbeencapturedinconceptsliketechnology, innovationandknowledge.Whiletheseconceptshaveevolvedoverthelastdecades,thepointthatthe ideasandtheinternationalconnectivityarecentralforIBremainsgenuine.Thispaperisanattemptto takestockoftheevolutionoftheconceptstechnology,innovationandknowledgeinIBliteraturealong thepastfivedecadeswithaparticularfocusontheroleoftheColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness(CJWB) andtheJournalofWorldBusiness(JWB)inthisevolution.Likewise,ourobjectiveistoofferaresearch agendaforthecomingdecade.Weproceedintwosteps.First,wescrutinizehowtheIBliteraturehas progressedandexpandedoverthelastfivedecades,illustratingthisonthebasisofarticlespublishedin CJWBandJWB.Second,wetakeahelicopterviewonthisliteratureandreflectontheinsightswehave gainedandthechallengestheIBfieldhasaheadthatcanconstitutethebasisforafutureresearchagenda. Wehighlighttheimportanceofcreatingamicro-foundationofknowledgeprocesseswheremechanisms ontheinteractionbetweenthehigherlevels(nation,firm,teams)andtheindividuallevelareclarified. ß2015ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

* Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses:ulf.r.andersson@mdh.se(U.Andersson),

angels.dasi@uv.es(A`.Dası´),ram.mudambi@temple.edu(R.Mudambi),

torben.pedersen@unibocconi.it(T.Pedersen).

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Journal

of

World

Business

j ourn a lhom e pa g e :ww w . e l se v i e r. c om / l oca t e / j w b

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.08.017

growthduringthelastfiftyyears.Technologyreferstothetoolsand machinesthatareusedtosolvereal-worldproblems.Innovationis anewidea,a moreeffectivedeviceorprocess.Knowledgeisthe familiarity with or understanding of something such as facts, informationorskills.

A striking example of the power of these phenomena is MalcolmP.Mclean’sidea(datingbacktothe1950s)oftransporting entire truck-trailers (containers) without unloading the cargo whenswitchingthemodeoftransportatione.g.fromtraintoship. Thisideaturnedouttobeoneofthemostpowerfulinnovations, promotingcontainerizationandtheinter-modalcargotransport, which has been a major driver of globalization through the lowering of logistics and transport costs.1 In this example the

developmentofthecontainerreflectsthetechnology,theideaof inter-modalcargotransportistheinnovationandtheknowledgeis representedbyMalcolmP.Mclean’ssubstantialprevious experi-enceinthetransportsector.

IBscholarshiphasdevelopedalongtwocontextuallevelswhen dealingwiththesethreeconcepts.Atonelevel,inwhatmightbe called‘‘macro-IB’’,thereisthestudyofaggregatelevelsofbusiness activityattheinter-countryandeveninter-regionallevel(where byregionswerefertogroupsofcountries).ThislevelofIBresearch is mainly developed on the foundations of international trade theory. A useful organizing framework for innovation and knowledge at this level is the national systems of innovation (NSI)approach(Lundvall,2007)thathasprovidedanexplanation aboutthelocationadvantagesforfirmsaswellasabouttheeffect thatforeigndirectinvestment(FDI) spillovershaveon thehost countries.

Atanotherlevel,inwhatmightbecalled‘‘micro-IB’’,thereisthe studyofinternationalactivitiesoffirms.Themostimportantfirms forstudyatthislevelofIBresearcharemultinationalenterprises (MNEs). This level of research developed by applying insights mainlyderivedfromindustrialorganizationeconomics(Buckley& Casson, 1976). Beginning with the work of Kogut and Zander (1993),anevenlargerliteraturehasmushroomed,studyingMNEs’ innovationandknowledgemanagement,astheytapintodiverse pocketsofknowledgearoundtheworldinordertobuttresstheir competitiveadvantages.

Wewantheretohighlighttwokeyaspects–themoreexternal interactionbetween thefirm and thelocation and theinternal interactionbetweenthefirmandthelowerlevelsofteamsand individuals–thathaveaffectedthesetwolevelsofanalysisand shapedtheimportanceofinnovation,knowledgeandtechnology for IB literature. The firm is conceptualized as the agent that combinestheexternalexposure(intermsofadapting,positioning, sourcing,leveragingideas)withtheinternalmobilization(interms ofcreation,integrationanddisseminationofideas).This concep-tualization points at the MNE’s role of orchestrating both the interactionwiththelocationandtheinteractionwithindividuals intheMNE.

1.1. Interactionbetweenthefirmandthelocations

Boththemacro-IBandthemicro-IBstudiesareengagedwith theinteractionbetweenthefirmandtheinternational environ-ment (Dunning, 1993; Rugman & Verbeke, 2001). Within this literature,themobilefirmspecificadvantages(carriedbyMNEs) and immobile location bound advantages (attached to the locations) must evolve together in order to create value. A

traditional view on location would imply that location bound advantages are generic resources available to all firms in the particular location (Dunning, 1993). However, more recent researchchallengesthisviewbysuggestingthatMNEsdifferin theirlocationcapability(‘‘senseofplace’’).Thisimpliesthatnotall MNEsareequallygoodatmakingthemostofthelocationbound advantagesinagivenlocation(Zaheer&Nachum,2011).

An integral part of this literature that relates to ideas and creativityistheexplicitrecognitionoftheongoingprogressionof ‘‘fine-slicing’’ (Mudambi, 2008). Creative activities are being constantly honed and separated into more narrowly defined ‘‘specialized’’ (non-repetitive) activities, with the remainder becoming ‘‘standardized’’ and repetitive. Continual innovation results in persistent activity down-skilling and de-skilling: components of activities that were once creative become standardized, modularized and amenable tobeing offshored to low-cost, low-skill locations or being automated. There is a concomitant process of ‘‘value migration’’, i.e., as specialized activities are down-skilled and become standardized, value becomesconcentrated withtheactivityslicesthat remain non-repetitive. In other words, the creative ‘‘heart’’ of an activity becomes more narrowly defined (Contractor, Kumar, Kundu, & Pedersen,2010).

Thismorenarrowdefinitionhasbothacostandacapability aspect.Highknowledgeactivitiesareexpensive,sodefiningthem morenarrowlyreducescosts.However,morespecializationalso increases innovation and customization capabilities. Related to this process of ‘‘fine-slicing’’ is the configuration of the firm’s activities.TheMNE’sactivitiesarearrangedinsuchawaythatthey make the most of thegeographic dispersion by constructing a global network. MNEs can thereby access dispersed pools of knowledgefosteringtheirinnovation.Consequently,by interact-ing withlocations MNEs have thepossibility to organize their activitiesforbalancingtheexploitationoftheircurrentknowledge baseand theexplorationof newknowledge bases (Cantwell& Mudambi,2005;Cantwell&Mudambi,2011).

1.2. Interactionbetweenthefirmandtheindividuals

Orchestration of the multinational firm relies heavily on connectivity:inter-andintra-organizationalnetworksaswellas betweenandwithinlocations.Connectivityappearsintwoforms– organization-based‘‘pipelines’’createdandmaintainedbyMNEs andindividual-basedpersonalrelationshipsthatoftenarisewithin communitiesofpractice,networksorglobaldiasporas(Lorenzen& Mudambi, 2013). While the key role of connectivity,has been recognizedintheIBliteraturethebulkoftheresearchhasfocused ontheorganizationallevelofanalysis,i.e.,intra-MNEknowledge flows(Foss &Pedersen,2004)and MNEknowledgesourcingin clustersandglobalcentersofexcellence(Cantwell&Mudambi, 2011). The point we make here highlights the importance of individualactorsindeterminingoutcomes.MNEs,communitiesof practiceandnetworksproviderespectivelyformaland informal operatingframeworkswithinwhichindividualemployees under-takeinnovativeactivities.

Theforegoingdiscussionhighlightstwoimportantthemesfor future developments in IB research. First, recognizing the importance of the individual level of analysis enables us to distinguishbetween theabilitytoundertake knowledge-centric actionsthatfurthertheinterestsoftheorganization(e.g.,theMNE) andthewillingnesstodoso(Mudambi, Pedersen,&Andersson, 2014). This ability-willingness divide and more generally the microfoundations of the knowledge processes have received relatively little attention in the IB literature thus far (Foss & Pedersen,2004)astheprimefocushasbeenonknowledgesharing onorganizationallevel.Eventhelimitedlowerlevelliteratureis

1SomedecadesagoPeterDruckerpointedoutthat‘‘...therewasnotmuchnew

technologyinvolvedintheideaofmovingatruckbodyoffitswheelsandontoa

cargovessel...but...withoutit,thetremendousexpansionofworldtradeinthe

lastfortyyears–thefastestgrowthinanymajoreconomicactivityeverrecorded,

ratherscatteredunderavarietyofdifferentlabelsrangingfrom attention(Bouquet& Birkinshaw, 2008)to power (Mudambi& Navarra,2004).Therefore,morefocusonlowerlevelsofanalysis andtheirsubsequentaggregationcanhelpinunderstandingthe mechanismsunderlyingorganizationalprocesses.Since individu-alsaretherealagentsinknowledgeprocessesanunderstandingof higherlevel knowledge processesmust be based on an under-standingoftheindividuallevel.

Second,theimportanceofconnectivityand therelevanceof individualactorssuggest thattheboundary spanning literature offersafruitfulavenuealongwhichIBresearchcandevelopnew insights (Carlile,2002). Connectivity creates the conditions for softening some of the problems that arise when transferring knowledge, but boundary spanning recognizes that for such connectivitytobefruitfulitalsorequiresovercomingresistanceof variousforms(Schotter&Beamish,2010).

Theliteratureonideasandcreativityhasdeveloped consider-ablebothintermsoftheoreticalsophisticationandmethodological depth,however,wehighlightthatamajorchallengeaheadofusis thedevelopmentoftheoriesandmethodologiesthatallowusto study knowledge as a multilevel construct (with interactions between the relevant levels) and where the (higher level) organizationalconstructsaregroundedatthe(lower)individual level.

Wetakestockoftheextantpoolofknowledgeintwosteps. First,wewillscrutinizehowtheIB-literaturehasprogressedand expandedoverthelastfivedecades.Inparticular,weexaminehow thekey concepts and topics that have beenhighlighted in the literaturehavechangedsignificantlyalongthisperiod.Inthemain, weillustratethisonthebasisofarticlespublishedinJWBandas suchwewillrevealthesignificantroleplayedbythejournalinthe IB literature. Second, we take a helicopter view on the vast literatureproducedoverthelast fivedecadesandreflectonthe insightswehavegainedandthechallengeswehaveaheadofus. Thiswillenableustoidentifywhereweshouldfocusourattention infutureresearchonsourcing,generating,applyingandleveraging ideasintheinternationalcontext.

2. Technology,innovationandknowledgeinJournalofWorld Business:ananalysisoffivedecadesofresearch

The last five decades of history have witnessed major technological changes and innovations that have fueled global tradeandtheevolutionofinternationalfirmsbutalsothathave raisedimportantissuesastherelevanceofknowledgeprocesses forsustainingfirms’competitiveadvantage.

Withtheaimofstudyingthoroughlytheoveralltrajectoryof theseconceptsduringthisperiodwehavedonealiteraturereview ofthejournalthatshowsthatJWBanditspredecessorColumbia JournalofWorldBusiness(CJWB)havebeenincontinuousdialog withtheenvironmentalchangesaswellaswiththeevolutionof theIBfield.

WeundertookaBooleansearchofallthearticlespublishedin JWBandCJWBsincetheirinception,2includingthosearticlesthat

hadthefollowingwordsintheirtitles:knowledge,innovationor technology.Thissearchresultedinapreliminarylistof118articles withthefollowingdistributionbykeyword(seeTable1).

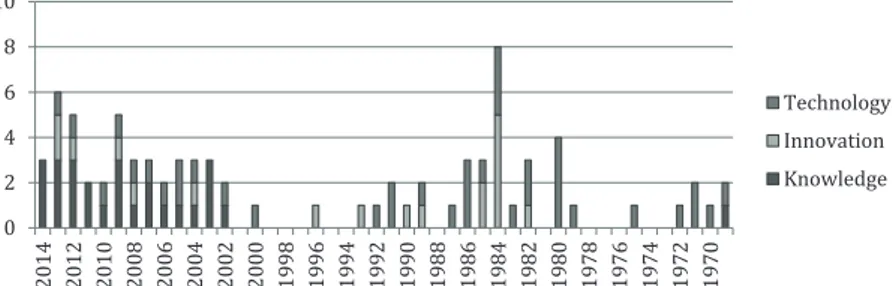

Aftereliminatingduplications(articleshavingtwoormoreof thekeywordsinthetitle)weobtainedalistof110articlesthathad atleastoneofthekeywordsinthetitle.Weanalyzedtheabstract ofthesearticlesandeliminatedthosethatwerenotrelatedtoour approach. Thisprocessended in a finallist of82 articles3 that

presentthefollowingdescriptionregardingtheyearofpublication andthemainwordinthetitle4(seeFig.1).

Concerningtheevolutionofthemainthemes,itisstrikingthat technology-relatedissuescenteredtheattentionofauthorsduring thefirsttwodecadesofthejournal,whileinnovationappearedasa key word in theeighties and knowledge surfaced as themost relevant concept during the last decade. These trends are comparable tothoseshown inthesimilartimeperiodbyother relevantjournalsintheIBfieldsuchastheJournalofInternational BusinessStudies(Fig.2).Theevolutiondepictedherereflectsnot only how IB scholars have treated these main issues but also portraysthemainquestionsinternationalfirmsandinstitutions havebeenconcernedwithduringthelast50years.

Itisfairtosaythatthefocushasbeenonideasandcreativityin thewholeperiod,buttheconceptsforcapturingtheiressencehave changed. Thisis true not onlyfor the IB-field,but alsofor the broaderfieldofstrategyandmanagement.Onewaytoillustrate thedevelopmentinthekeyconceptsistousetheanalogyofatree, where the technology, innovation and knowledge are like the leaves,branchesandtrunkofthetree,respectively.Thetechnology is the tangible outcome of ideas and creativity, while the innovations are thosethat formtheplatformsfor development in technology(likethebranchesthatcarry theleaves),andthe knowledgeiscomposedbytheintangibleandtangibleelements that are underlying both innovations and technology (likethe trunkthatisfeedingthebranchesandtheleaves).Partofthetrunk ishiddenunderthegroundsuchliketacitknowledgethatisalso considered to be the most valuable for supporting both the innovationsandthetechnology.Thisanalogytellsusthatthelast 50yearsofresearchinthisareahavebeenajourneyofdigging deeper and conceptualizing the underlyingfactors. It is also a reflectionoftheglobaldevelopmentwheretechnologycyclesare getting faster and imitation is becoming quicker,which forces firmstofocusmoreonhigherlevelknowledgeandcapabilitiesin ordertocreatevalue.Themanagementofknowledgeincludingthe processesofsourcing,integrationandtransferofknowledgeacross theMNEhasbecomethekeyinstayingaheadofcompetition.

WhencomparingFigs.1and2itisnoteworthythatCJWB/JWB pickeduparticlesontechnology andinnovationrelativelyearly (even before JIBS). However, it was relatively late in featuring articlesonknowledgeprocesses,withitsfirstarticlesappearingin 2002whilethefirstarticlesonsuchprocessesappearedinJIBSin 1993.ThiswasduetothedisciplinarydomainofCJWB,whichsaw itselfasmoreofaninternationalpoliticaleconomyjournal(inthe middle ground between Foreign Policy and Harvard Business Review). This editorial perspective was a better fit with the literature on technology and innovationthat wasmore macro-oriented.ItwasnotuntiltheeditorsFredLuthansandJohnSlocum tookoverin1996thatitturnedintoamoremanagementoriented journal. Intheir first editorialnotethetwo editorsstated‘‘Our statedvisionforJWBistocontributetothreeofthemostimportant areas of global management-strategy, human resources and

Table1

NumberofarticlesbykeywordsinthetitleinJWBand

CJWB.

Wordinthetitle Numberofarticles

Knowledge 34

Innovation 24

Technology 60

Total 118

2

TheBooleansearchwasdoneinSeptember2nd,2014.

3

ThearticlesthatappearinFigure1,butarenotexplicitlycitedintextare

indicatedinthereferencelistwitha*mark.

4

Articleswithmorethanonekeywordinthetitlewereassignedtothemost

marketing’’(Luthans&Slocum,1997,p.2).Thiswasasignificant shiftintheprofile,butitstilltooksomeyearsbeforeJWBwasable tocatchup,sincethejournalmissedthefirstwaveofliteratureon knowledge processes fueled by authors like Rob Grant, Bruce Kogut,andUdoZander.Knowledgemanagementismentionedfor thefirsttimein2000,intheeditorialnoteastheeditorsemphasize ‘‘wewouldhope thatadvanced informationtechnology, knowl-edge management, and entrepreneurship in the international arenawillalsobereflectedinfutureissues’’(Luthans&Slocum, 2000,p.331–332).

InfurtheranalyzingtheevolutionoftheJWBwehaveadvanced intwosteps:firstweperformedageneraloverviewofthelisted articles,andsecondweidentifiedthemaincontributionsof the journal in this time period by scrutinizing the most relevant articlesinthelist.

2.1. GeneraloverviewofJWBandCJWB(1965–2014)

Withtheaimofunderstandingwhicharethemainconcepts andconstructsrelatedtoknowledge,innovationandtechnology thathaveappearedovertheyears,wedidacontentanalysisofthe articles’abstracts.Weinspectedtheabstractsseparately,codified, andclassifiedthemainconcepts.

ToaccomplishthisclassificationweemployedEisenhardtand Santos(2001)categorizationofknowledgeprocessesasconsisting offourspecificsub-processes:externaltransfer,sourcing,internal transfer,and integration. Froma theoreticalpoint of view this categorizationaugmentsourunderstandingasitallowsustotake intoaccountthenuancesofthefirm’sinteractionsbothinternally andexternally,andhowthemainperspective–macroormicro– hasevolvedovertheyears.Wealsoappliedthiscategorizationof knowledgeprocessestotheconceptsoftechnologyand innova-tion,asthisisconsistentwiththewayIBliteraturehasconsidered them. Mainly as sources of sustained advantage and superior performance, and therefore given much attention to those elementsthatdistinguishandaffectthedifferentsub-processes.

The four categories of knowledge-processes reflect two fundamental underlying phenomena: the exploitation of the

extantcompetenciesofthecorporategroup(home-base exploita-tion) and the creation of competencies that are new to the group(home-base augmenting) (Kuemmerle,1999; Cantwell & Mudambi,2005).

Theprocessesofexternalandinternalknowledgetransferare competenceexploitingastheyessentiallyincludethetransferof existingknowledgefromthehomecountryoranotherimportant countrytosubsidiaries(internaltransfer)orexternalcounterparts (externaltransferintheforeigncountry).Sourcingandintegration are,ontheotherhand,moreaboutacquiringnewknowledgefrom outside the MNE and integrating it in the organization and thereforeessentiallyaboutcreatingcompetenciesthatarenewto thecorporategroup.Thefourknowledgeprocessescanfurtherbe divided into whether they are mainly taking place within or outsidetheboundariesofthefirm.Applyingthesetwodimensions thefourknowledgesub-processescanbeplacedinatwo-by-two tableasillustratedinTable2.

2.2. MaincontributionsoftheJWBtotheroleoftechnology, innovationandknowledge

WehaveidentifiedthemostrelevantarticlesinJWBandCJWB by using Google Scholar citations. Among our previous list of 82 articles,we have selected those whose total citations were abovetheaverage(averagecitationsperarticleis38.8).Inorderto beup todate we have alsoadded a few articles,dealing with relevantnewissuesrelatedtothehereanalyzedprocesses,that havebeenpublishedmorerecently(in2012–2014)andthatinour mindshavethepotentialtoreachahighnumberofcitations.Allin allthisisresultingin30articlesthatarelistedinTable3.

Thisgeneraloverviewrevealssomeinterestinginsightsrelated totheevolutionofthemainresearchquestions.Clearly,whilethe dominantperspectiveofthefirsttwodecadeshadbeenmoreon internationalexploitation ofexistingcompetenciesofthegroup (home-basedexploitingknowledgeprocesses),mainlycenteredon howMNEscanprotecttheirtechnologyinvestmentswhendoing business abroad, subsequent development of the journal has divertedintotheglobalsourcingandcreationofcompetenciesthat

0 2 4 6 8 10 20 14 2012 2010 20 08 20 06 20 04 2002 2000 1998 1996 19 94 1992 1990 19 88 19 86 19 84 19 82 1980 19 78 1976 19 74 1972 1970 Technology Innovation Knowledge

Fig.1.ArticlesdistributionbyyearandkeywordinCJWBandJWB1965–2014.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2014 2012 20 10 20 08 2006 20 04 20 02 2000 19 98 19 96 1994 19 92 1990 1988 19 86 19 84 1982 1980 19 78 19 76 19 74 1972 1970 Technology Innovation Knowledge

are new to the group (home-based augmenting knowledge processes)withmoreattentiononinternalprocessesandfactors. Additionally,wecanseehowthejournalhasevolvedfrombeing mainlyfocusedontheinteractionofthefirmwiththeenvironment toward the analysis of the firm’s internal processes related to knowledge,innovationandtechnology.Inthisway,initialarticles weremainlyconcernedwiththeexternal transferandsourcing processes, where the research questions were analyzed at the

country,industryandfirmlevel.However,asthefieldhasevolved toward paying more attention to the role of the firms and individuals in managing the links across the boundaries, the journal has also switched focus toward more micro levels of analysisandhasmaderelevantcontributionsregardinginternal transferandintegrationprocesses.

Someotherreflectionsthatcutacrossthelistedarticlesarethat qualitativearticlesweremoredominantinthebeginningofthe period, when it was difficult to get access to data on these knowledgeprocesses. However, quantitativeanalysis are domi-natinginthemorerecentarticles,indicatingthatdataavailability has muchimproved both when it comes toprimary data (e.g. survey)andsecondarydata(e.g.patentsandtrademarks).Alsothe context ofthestudieshaschanged withthebulkof therecent studies conducted in Chinaor other emerging economies. This change in context alsoresponds toa changein theway these

Table3

Generaloverviewofarticles’content.

Knowledge,Innovation

andTechnologyProcesses

Mainconcepts

ExternalTransfer Country

-NationalSystemsofInnovation(Chakrabarti,Feinman,&Fuentivilla,1982)

-Countries’InstitutionalDevelopment(Hendryx,1986;McGaugheyetal.,2000;Tihanyi&Roath,2002)

-Regionalintegration(Tihanyi&Roath,2002)

-Hostcountryculturalfactors(Buckleyetal.,2006;Hendryx,1986)

Industry

-InterandIntra-industryrelationships(Liu&Zou,2008)

Firm

-Firms’propertyrightsprotection(McGaugheyetal.,2000;Tihanyi&Roath,2002)

-TechnologyFDIandspillovers(Liu&Zou,2008)

-InternationalJointVentures(Berdrow&Lane,2003;Buckleyetal.,2006;Osborn&Baughn,1987)

-Modesoftechnologytransfer(Liu&Zou,2008;Osborn&Baughn,1987;Tihanyi&Roath,2002)

Sourcing Country

-Externalembeddedness(Gassmann&Keupp,2007)

-Culturalfactorsaffectingtechnologyorinnovationsourcing(Zhou,2007)

Firm

-KnowledgeorTechnologyacquisitionmode(Killing,1980)

-Firms’entrepreneurialorientation(Zhou,2007)

-Firms’internationalizationprocess(Casillasetal.,2009;Gassmann&Keupp,2007;Nordman&Mele´n,2008;Zhou,2007)

-Domesticvsforeignsourcing(Kafouros&Forsans,2012)

Individual

-Managerial-expatriateroles(Kotabeetal.,2011;Li&Scullion,2010)

Asset

-Knowledge,innovationortechnologycharacteristics(Li&Scullion,2010;Nordman&Mele´n,2008;Zhou,2007)

-Typeofsourcesofknowledge(Casillasetal.,2009;Kotabeetal.,2011;Li&Scullion,2010)

InternalTransfer Country

-Hostcountryenvironmentalfactors(Cuietal.,2006;Rugman&Bennett,1982)

Firm

-KnowledgeflowsfromHeadquarterstoSubsidiaries(Fang,Wade,Delios,&Beamish,2013;Michailova&Mustaffa,2012;

Wangetal.,2004)

-Reverseknowledgeflows(Asakawa&Lehrer,2003;Lazarova&Tarique,2005;Michailova&Mustaffa,2012;Najafi,Giroud,&

Andersson,2014;Rabbiosi&Santangelo,2013)

-Transfermechanisms(Lagerstro¨m&Andersson,2003;Rabbiosi&Santangelo,2013)

Unit

-Subsidiaryinfluence/roles(Asakawa&Lehrer,2003;Ciabuschi,Dellestrand,&Kappen,2012;Najafietal.,2014;

Rugman&Bennett,1982)

-Subsidiariesperformance(Cuietal.,2006;Fangetal.,2013)

-Embeddedness(Najafietal.,2014)

Team-Individual

-Transnationalteams(Lagerstro¨m&Andersson,2003;Raabetal.,2014)

-Expatriateroleandcareer(Lazarova&Tarique,2005)

-Managers’knowledgemobilization(Raabetal.,2014;Tippmannetal.,2014)

Integration Unit

-Compatibilitybetweenknowledge’sbases(Casillasetal.,2009)

-Realizedabsorptivecapacity(Casillasetal.,2009;Kotabeetal.,2011)

-Levelofknowledgeacquisition(Kotabeetal.,2011)

Team-Individual

-Socialandworkinteraction(Lagerstro¨m&Andersson,2003)

-Managers’visionaryleadership(Elenkov&Manev,2009)

-Culturalintelligence(Elenkov&Manev,2009)

Table2

Thefourknowledgesub-processes.

Competence exploitation

Competence creation

Outsidethefirmboundaries Externaltransfer Sourcing

countrieshavebeenconceptualized–frompassivereceiversofFDI spilloverstosignificantpoolsofknowledgeandinnovationthat canleveragefirm’scapabilities.

Inthefollowingwewilloutlinethemaininsightsofthefour knowledgesub-processesderivedfromthe30listedJWB-articles (inTable3).

2.2.1. Externaltransfer

Externaltransferreferstothoseprocesseswherefirmsshare theirknowledge,innovationandtechnologyacrossfirm bound-aries(Eisenhardt&Santos,2001).Inthecaseofinternationalfirms, externaltransfercaninvolveotherfirms–asithasbeeninresearch onforexampleinternationaljointventures(IJVs)–butalsothe host country institutions as well as the nature and quality of innovationinthehostcountry.

In thissense,thequalityofthehostcountryenvironmentin termsofitsinstitutionalsystemandpropertyrightsprotectionhas beenamajorthemesincethesixties,wheresomeauthorsanalyzed howthesefactorsaffectedfirms’investmentsabroad(Hendryx, 1986; McGaughey, Liesch, & Poulson, 2000). The increasing amountsofFDIflowsfromadvancedcountriesMNEstoemerging ortransitioneconomiesraisedimportantquestionsforfirmsand scholars.For instance,Tihanyiand Roath(2002)pointedattwo mainfactorsaffectingtheinstitutionaldevelopmentofacountry: its market development from planned economies toward the creationofa marketdriven systemandits regionalintegration with other countries. Taking into account these variables the authorsproposedacontingentapproachandestablisheddifferent strategies for firms’ technology transfer that comprised the technology transfer mode, the technology life cycle and the compensationsystem.Suchaperspectivewasinaccordancewith howtheIBfielddevelopedduringtheeightiesandnineties,where thestateofNationalSystemsofInnovationandtheFDIspillovers wererelevantissuesforfirms’internationalstrategies(Dunning, 1993;Pearce,1989).However,morerecentcontributionsevaluate theeffectof internationalforeignspilloversfrom theemerging countries perspective.Along this line, Liu andZou (2008) have shownthepositiveimpactthattechnology-orientedFDIhashad ontheinnovationactivitiesofChinesefirmsandhavedelvedinto theintra- andinter-industryspilloversgeneratedcontingenton theentrymodeused,e.g.exports,greenfieldorM&A.

The choiceofthetechnology transfer modehasalso beena relevanttheme.Initialstudiesfocusedonthefactorsaffectingthe choiceofthetypeofagreementandthereasonsbehindtheuseof licensesorjointventures(Osborn&Baughn,1987).Morerecently, differentauthorshaveadvancedourunderstandingoftheIJVsas strategies for technology or knowledge transfer among firms. ThroughaqualitativestudyofeightIJVsBerdrowandLane(2003)

identifiedsixdimensionsthatdifferentiatethesuccessfulones(e.g. thestrategicintegrationoftheIJVactivitiesorthetypeofmindset ofthepartners).Applyingalearningperspectivetojointventures these authors added relevant insights to extant knowledge (Inkpen,1995),astheydetailedhowthesesixdimensionshada roleinbothdirectionsofknowledgeflows-fromtheparentstothe IJVandalsofromtheIJVtotheparents.

The IJVs have also been the context for investigating the relevantquestionofculturaldifferencesandhowtheyaffectthe process of external transfer. Buckley, Clegg, and Tan (2006)

contributed to the analysis of emerging economies and their specificities by scrutinizing how the importance of networks (guanxi) and face-related issues (mianzi) in China affected the development of relationships with employees, partners and institutions. Part of a fruitful conversation about how cultural differencesinfluencedIB (Shenkar, 2001), their articleoffereda normative model indicating how cultural awareness improved partners’relationshipsandknowledgetransfer.

2.2.2. Sourcing

According to Eisenhardt and Santos (2001) sourcing is the processbywhichmanagersidentifyandgainaccesstorelevant knowledge that is created in the environment i.e. outside the boundariesofthefocalfirm.Thisisexternalsourcingofknowledge thattypicallywillbemorecompetence-creatinginnature,when combinedwiththeinternalknowledge.Recognitionandaccessare twocomponentsofsourcingthatimplydifferentcapabilitiesfrom managers. While the recognition of the knowledge gaps is a process that depends mainly on the managers learning and assessment capabilities (Petersen,Pedersen, &Lyles,2008), the access torelevant knowledge is more dependent on firmsand managers tappinginto specializedknowledge through network embeddedness(Andersson,Forsgren,&Holm,2002).Inaddition,a recent stream of researchexplores the heterogeneity in MNEs abilitiestoachieveembeddednessinknowledgeclusters(Cantwell &Mudambi,2011).ThisresearchconcludesthatleadingMNEsare much more likely to achieve the ‘‘insider’’ status in local knowledge networks that is a key requirement for knowledge sourcing (Giuliani, 2007). In contrast, lagging MNEs remain ‘‘outsiders’’and areforced to rely on their parent’s knowledge resources.

Along these years the JWB has considered different issues relatedtoknowledgeandtechnologysourcingprocesses.Probably, themostrelevantcontributionshavebeenrelatedtotheroleof knowledgeasa sourcefor firms’internationalizationprocesses. The special issue launched in 2007 about the early and rapid internationalization of the firm contributed strongly to the substantial debate about the role that experiential knowledge (Eriksson,Johanson,Majkgard,&Sharma,1997)andinternational entrepreneurialorientation(Knight&Cavusgil,2004)playinthe internationalizationprocessofthefirm(Johanson&Vahlne,1977; Oviatt &McDougall,1994). Zhou (2007)tested both factorson younginternationalfirmsinChinaandfoundaseparateeffectof three dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation, where the proactiveness dimension were the most relevant for obtaining foreignmarketknowledge.

GassmannandKeupp(2007)appliedaknowledge-basedview and identified several factors contributing to the competitive advantage of born global SMEs. Among them, the firms’ embeddednessinglobalcommunitiesandnetworkswaspointed outastheonethatallowed themtoupdateand maintaintheir specialized knowledge atlow marginal cost,which constituted partof thecompetitive advantage of bornglobal SMEs.Hence,

Gassmann and Keupp (2007) extended to SMEs some of the arguments that previously were pointed out as critical in the context of subsidiaries’ competence development (Andersson etal.,2002;Andersson,Forsgren,&Holm,2007).Casillas,Moreno, Acedo,Gallego,andRamos(2009)proposedthatinthecontextof knowledgeneededforentryintoanewmarket,externalsourcesof informationareabsorbedmoreslowlybythefirmthanitsown internal sources, since the latter depend on its own current experiencesandknowledge.

Not only hastheorigin of theknowledge beenanalyzed in relationtofirms’internationalizationprocesses,butalsothetype of knowledge managers and founders possess – international knowledge and technological knowledge (Nordman & Mele´n, 2008).Interestingly,thistypeofknowledgemattersfortheway firms’managersdiscovernewforeignmarketopportunitiesand commit to them. All in all, these studies contributed to the extensiveconversationon theproactiveor reactivecharacterof firms’ internationalization processes (Forsgren, 2002; Petersen, Pedersen,&Sharma,2003;Johanson&Vahlne,2009).

Theroleofmanagersinprovidingknowledgehasbeenrecently emphasized.BothLiandScullion(2010)and Kotabe,Jiang,and Murray(2011)identifytheimportanceofmanagerialtiesaswellas

political and business ties to facilitate external knowledge acquisition,inparticular,inthecaseoffirmsoperatinginemerging marketswherethenatureoflocalknowledgeisdifferentinterms oftacitnessanddiffusion.Adoptingamicro-foundations perspec-tive,Tippmann,Scott,andMangematin(2014)qualitativestudy providesrichfindingsaboutthedifferentpracticesandpatterns that subsidiaries’ managers follow for sourcing knowledge. Accordingtotheir study,suchpracticesdifferdependingon the typeofproblemthatmanagersface.Whiledeliberateknowledge flows (e.g. top-down knowledge inflows) occur mostly within functional domains and serve for routine problems, when managers face non-routine problems and search for specifics solutions,theypromoteemergentknowledgeinflows.Suchtypes of inflows aim at pursuing boundary-spanning knowledge mobilizationsand aremainlybottom-upand lateralknowledge flowsthatincreasethepotentialtodevelopcreativeandinnovative solutionstonon-routineproblems.

While the initial focus was more aggregate with articles providingattentiononhowfirmscouldsourcetechnologybyusing differenttechnologymodes(Killing,1980)themostrecentarticles inJWBhaveextendedourunderstandingofthesourcingprocesses byaddingknowledgeontheexplanatorymechanismsatthemicro levelsthathelpsunderstandtheroleoftheindividualincatalyzing thisknowledgeprocess.

2.2.3. Internaltransfer

Internal transfer processes are related to the sharing of knowledge,innovationandtechnologywithinfirms’boundaries. Regardingtothistypeofprocesses,IBliteraturehasbeengreatly influenced by the Knowledge-Based View (KBV) (Grant, 1996; Kogut & Zander, 1993)as wellas by Gupta and Govindarajan (2000)analysisofMNEsinternalknowledgeflows.

Forinstance,Wang,Tong,andKoh(2004)analyzedthefactors affectingknowledge transfer fromMNEs’ headquarters totheir Chinesesubsidiariestakingintoaccounttwokindsoffactors,the capacityandwillingnessoftheMNEfortransferringknowledge andthecapacityandintenttolearnbythesubsidiary.Eventhough theiranalysiswasatthesubsidiarylevel,therecognitionofthe dualeffectofwillingnessandabilitywasinlinewithsomeofthe seminal studies at this time period pin-pointing the need to uncoverthemicro-foundationsofknowledgetransferprocesses (Minbaeva, Pedersen, Bjo¨rkman, Fey, & Park, 2003; Foss & Pedersen,2004).

Thedebate about theknowledgeflows and thefactors that interveneinrealizingknowledgetransferhasbeenoneofthemost fruitfulinIBliterature.Alongtheselines,MichailovaandMustaffa (2012) made an insightful contribution by reviewing the IB literatureandcategorizingthemain factorsaffectingsubsidiary knowledgeflows.Theirstudyprovidesaclearpictureonthemain issues analyzedduringthetwo last decadesand givesrelevant guidelinesforfutureresearch.Wewillreturntosomeofthemin thenextsection.

Knowledgeandhighvalue-addedactivitieshavebeen recog-nizedas criticalfor subsidiariesspecificadvantages (Rugman & Verbeke,2001)andfor subsidiary power(Mudambi&Navarra, 2004;Mudambietal.,2014).Oneoftheearliestcontributionson subsidiaryroleswasconductedbyRugman andBennett(1982), whosearticleaboutthetechnologytransferthroughworldproduct mandate preceded the wave of research about MNEs internal configuration (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Hedlund, 1986) and discussedamoreactiveroleoftheparentinassigningmandatesto subsidiarieswherestrategicissuesratherthanlocalgovernment subsidiesweretakenintoaccount.

Asinthecaseofexternaltransfer,internaltransferinMNEsis alsoaffectedbyenvironmentalfactors.Cui,Griffith,Cavusgil,and Dabic(2006)madeajointanalysisofseveralenvironmentalfactors

thataffectedsubsidiariesadoptionoftransferredtechnologyand showedthatbothmarketfactorsandculturalfactorsrelatedtothe hostcountrymattersforinternalknowledgetransfer.Particularly marketdynamismandorganizationalculturaldistancecameforth asthefactorswiththestrongesteffect.AsMichailovaandMustaffa (2012)pointoutintheirliteraturereview,subsidiarieshavebeen studiedmoreasreceiversthansendersofknowledgeflows,which create space forfuture research on thedirectionof knowledge flowswithintheMNEandhowtomanagethem.

Alongthisline,therehavebeenseveralcontributionsinJWBon the‘‘reverseknowledgetransfer’’orprocesswheretheknowledge ortheinnovationsflowfromtheforeignunitstowardthecenterof the MNE. Taking into account the interactions between the subsidiariesandtheirgeographicallocations,AsakawaandLehrer (2003)providedimportant insightsabouttherole thatregional officescanplayasinnovationrelaysthatlinkedlocalknowledgeto the MNE’s global operations. In addition they identified the patternsfollowedbythoseMNEsthathaddispersedinnovation processes. On a more micro viewpoint, Lazarova and Tarique (2005) focused on repatriates as knowledge recipientsand the types of knowledge they acquire depending on the type of assignmenttheyhaveperformedabroad.Inordertoimprovethe reverseknowledgetransfer,theauthorssuggestedfirmsshould striveforafitbetweenthecareerdevelopmentinitiativesoffered and the repatriate career goals. Recently, Najafi, Giroud, and Andersson(2014),studiedtheroleofreverseknowledgetransfer forsubsidiaryinfluenceinMNEslookingattheinterplaybetween networkactivitiesandknowledgeactions.

2.2.4. Integration

Integration processes consist of combining knowledge from differentsourcestogeneratenewknowledgeortoapplyingitfor innovation(Eisenhardt&Santos,2001).Research onknowledge integrationprocesseshasfocusedonconstructsatamoremicro level of analysis, applying some of the insights from the organizationallearningliterature(Cohen&Levinthal,1990;Zahra &George,2002).BothCasillasetal.(2009)andKotabeetal.(2011)

applytheconceptsrealizedabsorptivecapacityandcompatibility betweenknowledgebases.

Other studies have investigated factors that can promote knowledgeintegrationandthemechanismsfirmscandeployto promoteknowledgeprocesses.Lagerstro¨mandAndersson(2003)

studythecaseoftransnationalteamsandfoundthatgoingbeyond information technology and creating organizational structures supportingemployees’interactionimprovedefficient communi-cation. Additionally, their qualitative study pointed at the proficiency ina common business languageas a key factor for knowledgesharingand creation.In thisregard, theirworkwas novelasitsignaledthatonefactor–languagedifferences–wasof outmost importance,which nowadays is considered critical for well-functioninginternalknowledgetransferprocesses(Ma¨kela¨, Andersson,&Seppa¨la¨,2012;Tenzer,Pudelko,&Harzing,2014).

Individualcharacteristicshavealsobeenanalyzedasrelevant factorsaffectingintegrationprocesses.Forinstance,Elenkovand Manev(2009)showthatavisionary-transformationalleadership styleofexpatriatespositivelyinfluencedinnovationlevelsinthe units. Further their study shows that the expatriates’ cultural intelligenceisafactorthatpositivelymoderatesthiseffect.

3. Discussion

Theforegoinganalysishashighlightedthecentralroleplayed by the Journal of World Business in developing the agenda in international dimensionsof technology, innovation and knowl-edgeresearch.BeginningwiththeinfluentialKilling(1980)study throughmorerecentsignificantworkslikeinareaslikeemerging

markets(Cuietal.,2006)andgreenstrategies(Eiadat,Kelly,Roche, &Eyadat,2008),JWBhasconsistentlypublishedkeyarticlesthat have often opened up new research streams. Along with this consistencyinhighqualitypath-breakingresearch,wealsofind somesystematicchanges.

Wefindthatinearlierdecades,thepredominantfocusofstudy wasatthelevelof‘technology’.Inmorerecentdecades,thefocus hasshifted tothe wider level of‘innovation’, whilein the last decadeithasgrownevenwider,withanemphasison‘knowledge’. Ourmeta-analysissupportstheviewthatthischangeinsemantics reflectsadeepershifttowardawiderresearchlensinthisdomain ofinternationalbusinessresearch.

Alliedwiththiswideningofresearchfocus,wenoteadriftin theunitofanalysistoamoredisaggregatedlevel.Whileearlywork waslargelyconductedatthecountryandindustrylevel,itlater movedontothefirmlevelandsometimeseventotheteamorthe individuallevel. In themostrecent decade,a great deal of the researchhasbeenconductedattheintra-MNElevel,allowingfor theextricationofunderlyingmechanismsinknowledgeprocesses asthemorecomplexinteractionbetweenfirmsandlocationsfor knowledge accessing and diffusion or the relevance of the individual(e.g.managers,expatriates,employees,etc.)fordriving connectivitywithinandacrossfirms.Outofthefocused34papers themajority(27papers)areempiricalpapers(almost80%),but onlysixpaperstaketheindividuallevelintoaccount.Thefirstof thesesixpaperswaspublishedin2009whichshowsthatdealing withtheindividuallevelisafairlyrecentphenomenoninstudies oninnovation,technology,andknowledge.Onlyonesinglepaper (Raab,Ambos,&Tallman,2014)appliesamulti-levelapproachthat includestheindividuallevel.

WehastentoemphasizethatJWBisnotuniqueinthisregard. OurrobustnesstestonpapersinJIBSsupportsourfinding.Within IBresearchthereappearstobegrowingrecognitionthat(a)the explorationfornewsourcesofvaluecreationisagenericstrategy thatisservedbytechnology,innovationandknowledgecreation; and(b)thatexplorationprocessestendtovarydramaticallywithin firmsandevenacrossprojectswithinfirmsubunits(Andersson, Gaur,Mudambi,&Persson,2015).

Whilethisprogressoftheliteratureistobelauded,wenotea correspondinglackofstudiesthatintegratethevariouslevelsof analysis. With some exceptions (Lederman, 2010; Raab et al., 2014), the most recent studies typically undertake careful disaggregation and provide a detailed analysis of knowledge processesataveryhighlevelofgranularity.Whilesuchstudies answerthecallforbuildingknowledgeprocessesupfromtheir microfoundations,itisequallytruethatcollectivelevelofanalysis ismorethansimpleaggregationsoftheirconstituentindividuals andsubunits. Asrecognizedexplicitly byevolutionarytheorists beginningwithNelsonandWinter(1982),theroutinesthatform thebasisoforganizationalcapabilitiesarestructurallyembedded and cannot be imitated merely by assembling a similar set of resources.However,knowledgeisamultilevelconstruct: knowl-edgeresideswithinthemindsofindividualsandisabsorbedand transferredbyindividuals, while synergiesand interactions are manifested at the organizational level. Hence a complete understanding of knowledge processes requires an integration oftheindividuallevelofanalysiswithmoreaggregatelevels.Such a researchprogram requires the use of a multilevel approach (Andersson, Cuervo-Cazurra, &Nielsen, 2014) that requires the recognition that the objectives of lower levels of analysis like individualsandteamsoverlap onlypartly withthose ofhigher levelsofanalysis(Nohria&Ghoshal,1994;Mudambi&Navarra, 2004;Anderssonetal.,2007).

Whilethisisacriticalanalyticalmethod,itisonlyoneamong many approaches to disaggregating and analyzing knowledge processes.Inadditiontohierarchicaldisaggregation,knowledge

processescanbedisaggregatedalongfunctionallines.Knowledge integrationoftenrequirestheapplicationofdiverseskillssetsthat reside in specialized professional communities, e.g., scientists workingwith managers or R&D units workingwith marketing units(Mudambietal.,2014). Thisformofaggregationrequires applyingboundary-spanningtheory(Carlile,2002)toknowledge processesintheinternationalsetting(Schotter&Beamish,2010). How individual knowledge that is structured within a specific functioncanbecombinedwithotherfunctionalknowledge?How individualsinteractwithinhigher-levelunitsforestablishinglinks and formanagingotherinteractionswiththeexternal environ-ment?Towhatextenttheeffectivenessofconnectivity,intermsof managing knowledgeprocesses, is affectedby both individual-levelcharacteristicsandhigher-leveldeterminants,suchasteam leadershiporHRpractices?Boundary-spanningliterature(Ancona & Caldwell,1992; Carlile,2002; Marrone, 2010) canprovide a propitious lens for analyzing how MNEs manage knowledge-relatedprocessesasithelpsunderstandthechallengesraisedby boundaries (not only geographic but also organizational) and complexity.

The most promising avenues for future researchare at the intersectionofthesetwonexuses.Recognizingthatbothmultiple levelsofanalysisaswellasdiversityareinherentinknowledge processesiscrucial,especiallyascompetitivepressuresincrease with new, aggressive competitors from emerging markets. Knowledge-based competition is occurring in an increasingly globalarena,resultinginfastertechnologycycles.Valueisrapidly migratingoutoftangiblegoodstointangibles (Mudambi,2008) thatareheavilyrelianton tacitknowledgeelementslikedesign (Scalera, Mukherjee, Perri, & Mudambi, 2014). This rising complexitymeansthat singlelevelanduni-dimensional studies become progressively poorer approximations of reality. Future researchers face great challenges, but have at their disposal analyticaltheoriesandmethodswithenormouspromise.

References

Alavi,M.,&Leidner,D.E.(2001).Review:Knowledgemanagementandknowledge

managementsystems:Conceptualfoundationsandresearchissues.MIS Quarterly,25(1):107–136.

Ancona,D.G.,&Caldwell,D.F.(1992).Bridgingtheboundary:Externalactivityand

performanceinorganizationalteams.AdministrativeScienceQuarterly,37:634– 665.

Andersson,U.,Cuervo-Cazurra,A.,&Nielsen,B.(2014).Explaininginteraction

effectswithinandacrosslevelsofanalysis.JournalofInternationalBusiness Studies,45:1063–1071.

Andersson,U.,Forsgren,M.,&Holm,U.(2002).Thestrategicimpactofexternal

networks–Subsidiaryperformanceandcompetencedevelopmentinthe multinationalcorporation.StrategicManagementJournal,23(11):979–996.

Andersson,U.,Forsgren,M.,&Holm,U.(2007).Balancingsubsidiaryinfluencein

thefederativeMNC–Abusinessnetworkperspective.JournalofInternational BusinessStudies,38(5):802–818.

Andersson,U.,Gaur,A.,Mudambi,R.,&Persson,M.(2015).Unpackinginter-unit

knowledgetransferinMNCs.GlobalStrategyJournal,5(3):241–255.

Asakawa,K.,&Lehrer,M.(2003).Managinglocalknowledgeassetsglobally:The

roleofregionalinnovationrelays.JournalofWorldBusiness,38:31–42.

Bartell,M.(1984).*InnovationandtheCanadianexperience:Aperspective.

ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,19(4):88.

Bartlett,C.,&Ghoshal,S.(1989).Managingacrossborders.Thetransnationalsolution.

Boston:HarvardBusinessSchoolPress.

Berdrow,I.,&Lane,H.W.(2003).Internationaljointventures:Creatingvalue

throughsuccessfulknowledgemanagement.JournalofWorldBusiness,38:15– 30.

Bojica,A.M.,&Fuentes,M.M.F.(2012).*Knowledgeacquisitionandcorporate

entrepreneurship:InsightsfromSpanishSMEsintheICTsector.Journalof WorldBusiness,47(3):397.

Borlaug,N.E.(1969).*Agreenrevolutionyieldsagoldenharvest:Technologycan

bemorerevolutionarythanany‘‘ism’’;agricultural,morethanindustrial, technologyistransformingtheinternaleconomiesofdevelopingcountriesand maysoonbeasourceofcriticallyneededforeignexchange.ColumbiaJournalof WorldBusiness,4:9–19.

Bouquet,C.,&Birkinshaw,J.(2008).Weightversusvoice:Howforeignsubsidiaries

gainattentionfromcorporateheadquarters.AcademyofManagementJournal, 51(3):577–601.

Buckley,P.J.,&Casson,M.(1976).Thefutureofmultinationalenterprise.London: Macmillan.

Buckley,P.J.,Clegg,J.,&Tan,H.(2006).Culturalawarenessinknowledgetransfer

toChina.Theroleofguanxiandmianzi.JournalofWorldBusiness,41:275–288.

Camillus,J.C.(1984).*Technology-drivenandmarket-drivenlifecycles:

Implicationsformultinationalcorporatestrategy.ColumbiaJournalofWorld Business,19(2):56.

Cantwell,J.,&Mudambi,R.(2005).MNEcompetence-creatingsubsidiarymandates.

StrategicManagementJournal,26(12):1109–1128.

Cantwell,J.,&Mudambi,R.(2011).Physicalattractionandthegeographyof

knowledgesourcinginmultinationalenterprises.GlobalStrategyJournal,1(3– 4):206–232.

Carlile,P.(2002).Apragmaticviewofknowledgeandboundaries:Boundary

objectsinnewproductdevelopment.OrganizationScience,13(4):442–455.

Casillas,J.C.,Moreno,A.M.,Acedo,F.J.,Gallego,M.A.,&Ramos,E.(2009).An

integrativemodeloftheroleofknowledgeintheinternationalizationprocess. JournalofWorldBusiness,44:311–322.

Chakrabarti,A.K.,Feinman,S.,&Fuentivilla,W.(1982).Thecross-national

comparisonofpatternsofindustrialinnovations.ColumbiaJournalofWorld Business,17:33–40.

Chari,M.D.R.,Devaraj,S.,&David,P.(2007).*Internationaldiversificationandfirm

performance:Roleofinformationtechnologyinvestments.JournalofWorld Business,42(2):184–197.

Chen,C.,&Hsiao,Y.(2013).*Theendogenousroleoflocationchoiceinproduct

innovations.JournalofWorldBusiness,48(3):360–372.

Chorafas,D.N.(1970).*ComputertechnologyinwesternandEasternEurope.

ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,5:61–66.

Ciabuschi,F.,Dellestrand,H.,&Kappen,P.(2012).Thegood,thebad,andtheugly:

Technologytransfercompetence,rent-seeking,andbargaining.JournalofWorld Business,47:664–673.

Cohen,W.M.,&Levinthal,D.A.(1990).Absorptivecapacity:Anewperspectiveon

learningandinnovation.AdministrativeScienceQuarterly,35:128–152.

Contractor,F.J.(1983).*TechnologylicensingpracticeinUScompanies:Corporate

andpublicpolicyimplications.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,18:80–88.

Contractor,F.,Kumar,V.,Kundu,S.,&Pedersen,T.(2010).Reconceptualizingthe

firminaworldofoutsourcingandoffshoring:Theorganizationaland geographicalrelocationofhigh-valuecompanyfunctions.Journalof ManagementStudies,47(8):1417–1433.

Cui,A.S.,Griffith,D.A.,Cavusgil,S.T.,&Dabic,M.(2006).Theinfluenceofmarket

andculturalenvironmentalfactorsontechnologytransferbetweenforeign MNCsandlocalsubsidiaries:ACroatianillustration.JournalofWorldBusiness, 41:100–111.

Daneke,G.A.(1984).*Theglobalcontestoverthecontroloftheinnovation

process:Thecaseofbiotech.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,19(4):83.

Drazin,R.(1984).*Worldwideindustrialinnovation.ColumbiaJournalofWorld

Business,19:5–29.

Dunning,J.H.(1993).Multinationalenterpriseandtheglobaleconomy.Reading,MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Eiadat,Y.,Kelly,A.,Roche,F.,&Eyadat,H.(2008).Greenandcompetitive?An

empiricaltestofthemediatingroleofenvironmentalinnovationstrategy. JournalofWorldBusiness,43(2):131–145.

Eisenhardt,K.M.,&Santos,F.M.(2001).Knowledge-basedview:Anewtheoryof

strategy?InA.Pettigrew,H.Thomas,&R.Whittington(Eds.),Handbookof strategyandmanagement.SagePublications.

Elenkov,D.S.,&Manev,I.M.(2009).Seniorexpatriateleadership’seffectson

innovationandtheroleofculturalintelligence.JournalofWorldBusiness,44: 357–369.

Eriksson,K.,Johanson,J.,Majkgard,A.,&Sharma,D.D.(1997).Experiential

knowledgeandcostintheinternationalizationprocess.JournalofInternational BusinessStudies,28(2):337–360.

Evangelista,F.,&Hau,L.N.(2009).*Organizationalcontextandknowledge

acquisitioninIJVs:Anempiricalstudy.JournalofWorldBusiness,44(1):63–73.

Fang,Y.,Wade,M.,Delios,A.,&Beamish,P.(2013).Anexplorationofmultinational

enterpriseknowledgeresourcesandforeignsubsidiaryperformance.Journalof WorldBusiness,48:30–38.

Ferdows,K.,&Rosenbloom,R.S.(1981).*Technologypolicyandeconomic

development:PerspectivesforAsiainthe1980s.ColumbiaJournalofWorld Business,16(2):36.

Forsgren,M.(2002).TheconceptoflearningintheUppsalainternationalization

processmodel:Acriticalreview.InternationalBusinessReview,11:257–277.

Foss,N.J.,&Pedersen,T.(2004).Organizingknowledgeprocessesinthe

multinationalcorporation:Anintroduction.JournalofInternationalBusiness Studies,35:340–346.

Gassmann,O.,&Keupp,M.M.(2007).Thecompetitiveadvantageofearlyand

rapidlyinternationalizingSMEsinthebiotechnologyindustry:A knowledge-basedview.JournalofWorldBusiness,42:350–366.

Giuliani,E.(2007).Theselectivenatureofknowledgenetworksinclusters:

Evidencefromthewineindustry.JournalofEconomicGeography,7(2):139–168.

Globerman,S.,&Meredith,L.(1984).*Theforeignownership-innovationnexusin

Canada.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,19(4):53.

Grant,R.(1996).Towardaknowledge-basedtheoryofthefirm.Strategic

ManagementJournal,17:109–122.

Gupta,A.K.,&Govindarajan,V.(2000).Knowledgeflowswithinmultinational

corporations.StrategicManagementJournal,21(4):473–496.

Hayden,E.,&Nau,H.(1975).*East-westtechnologytransfer–Theoreticalmodels

andpracticalexperiences.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,10(3):70.

Hedlund,G.(1986).ThehypermodernMNC.Aheterarchy?HumanResource

Management,25:9–35.

Hendryx,S.R.(1986).Implementationofatechnologytransferjointventureinthe

People’sRepublicofChina:Amanagementperspective.ColumbiaJournalof WorldBusiness,21:57–66.

Hill,J.S.,&Still,R.R.(1980).*Culturaleffectsoftechnologytransferby

multinationalcorporationsinlesserdevelopedcountries.ColumbiaJournalof WorldBusiness,15(2):40.

Hong,J.F.L.,&Nguyen,T.V.(2009).*Knowledgeembeddednessandthetransfer

mechanismsinmultinationalcorporations.JournalofWorldBusiness,44(4): 347–356.

Husted,K.,&Vintergaard,C.(2004).*Stimulatinginnovationthroughcorporate

venturebases.JournalofWorldBusiness,39(3):296–306.

Hyman,R.,Treeck,W.,&Sockell,D.(1989).*Newtechnologyandindustrial

relations.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,24(4):79.

Inkpen,A.C.(1995).Organizationallearningandinternationaljointventures.

JournalofInternationalManagement.,1(2):165–198.

Johanson,J.,&Vahlne,J.E.(1977).Theinternationalizationprocessofthefirm:A

modelofknowledgedevelopmentandincreasingforeignmarketcommitments. JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,8:23–32.

Johanson,J.,&Vahlne,J.E.(2009).TheUppsalainternationalizationprocessmodel

revisited:Fromliabilityofforeignnesstoliabilityofoutsidership.Journalof InternationalBusinessStudies,40:1411–1431.

Kafouros,M.I.,&Forsans,N.(2012).Theroleofopeninnovationinemerging

economies:Docompaniesprofitfromthescientificknowledgeofothers? JournalofWorldBusiness,47:362–370.

Kaufmann,L.,&Reossing,S.(2005).*Managingconflictofinterestsbetween

headquartersandtheirsubsidiariesregardingtechnologytransfertoemerging markets-aframework.JournalofWorldBusiness,40(3):235–253.

Killing,J.P.(1980).Technologyacquisition:Licenseagreementorjointventure.

ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,15:38–46.

King,W.R.(1985).*Informationtechnologyandcorporategrowth.ColumbiaJournal

ofWorldBusiness,20(2):29.

Klavans,R.,Shanley,M.,&Evan,W.M.(1985).*Themanagementofinternal

corporateventures:Entrepreneurshipandinnovation.ColumbiaJournalofWorld Business,20(2):21.

Klitmøller,A.,&Lauring,J.(2013).*Whenglobalvirtualteamsshareknowledge:

Mediarichness,culturaldifferenceandlanguagecommonality.JournalofWorld Business,48(3):398.

Knight,G.A.,&Cavusgil,S.T.(2004).Innovation,organizationcapabilities

andtheborn-globalfirm.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,35:124– 141.

Kogut,B.,&Zander,U.(1993).Knowledgeofthefirmandtheevolutionarytheory

ofthemultinationalcorporation.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,24(4): 625–645.

Kotabe,M.,Jiang,C.X.,&Murray,J.Y.(2011).Managerialties,knowledge

acquisition,realizedabsorptivecapacityandnewmarketperformanceof emergingmultinationalcompanies:AcaseofChina.JournalofWorldBusiness, 46:166–176.

Krishna,E.M.,&Rao,C.P.(1986).*IsUShightechnologyhighenough?Columbia

JournalofWorldBusiness,21(2):47.

Kuemmerle,W.(1999).Thedriversofforeigndirectinvestmentintoresearchand

development:Anempiricalinvestigation.JournalofInternationalBusiness Studies,30(1):1–24.

Laforet,S.(2013).*OrganizationalinnovationoutcomesinSMEs:Effectsofage,size,

andsector.JournalofWorldBusiness,48(4):490.

Lagerstro¨m,K.,&Andersson,M.(2003).Creatingandsharingknowledgewithina

transnationalteam:Thedevelopmentsofaglobalbusinesssystem.Journalof WordBusiness,38:84–95.

Lazarova,M.,&Tarique,I.(2005).Knowledgetransferuponrepatriation.Journalof

WorldBusiness,40:361–373.

Lederman,D.(2010).Aninternationalmultilevelanalysisofproductinnovation.

JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,41:606–619.

Lee,S.,Trimi,S.,&Kim,C.(2013).*Theimpactofculturaldifferencesontechnology

adoption.JournalofWorldBusiness,48(1):20–29.

Lehrer,M.,&Asakawa,K.(2002).*Offshoreknowledgeincubation:The‘‘thirdpath’’

forembeddingR&Dlabsinforeignsystemsofinnovation.JournalofWorld Business,37(4):297–306.

Li,S.,&Scullion,H.(2010).Developingthelocalcompetenceofexpatriate

managersforemergingmarkets:Aknowledge-basedapproach.JournalofWorld Business,45:190–196.

Liao,T.,&Yu,C.J.(2012).*Knowledgetransfer,regulatorysupport,legitimacy,and

financialperformance:ThecaseofforeignfirmsinvestinginChina.Journalof WorldBusiness,47(1):114–122.

Liu,X.,&Zou,H.(2008).TheimpactofgreenfieldFDIandmergersandacquisitions

oninnovationinChinesehigh-techindustries.JournalofWorldBusiness,43: 352–364.

Lorenzen,M.,&Mudambi,R.(2013).Clusters,connectivityandcatch-up:Bangalore

andBollywoodintheglobaleconomy.JournalofEconomicGeography,13(3): 501–534.

Lovett,S.,Coyle,T.,&Adams,R.(2004).*JobsatisfactionandtechnologyinMexico.

JournalofWorldBusiness,39(3):217–232.

Lundvall,B.A˚.(2007).Nationalinnovationsystems—Analyticalconceptand

developmenttool.IndustryandInnovation,14(1):95–119.

Luthans,F.,&Slocum,J.W.(1997).TheJournalofWorldBusinessinlaunched.

Luthans,F.,&Slocum,J.W.(2000).Editor’snote.JournalofWorldBusiness,35(4): 331–332.

Lynn,L.(1984).*Japanadoptsanewtechnology:Therolesofgovernment,trading

firmsandsuppliers.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,19(4):39.

Marrone,J.A.(2010).Teamboundaryspanning.Amultilevelreviewofpast

researchandproposalsforthefuture.JournalofManagement.,36:911–940.

Martyn,H.(1969).*Ispy:Thetheftofknowledgeistodayabusinessas

multinationalinitsdriveandstructureasanycorporateentity.Columbia JournalofWorldBusiness,4:47–56.

McGaughey,S.L.,Liesch,P.W.,&Poulson,D.(2000).Anunconventionalapproach

tointellectualpropertyprotection:ThecaseofanAustralianfirmtransferring shipbuildingtechnologiestoChina.JournalofWorldBusiness,35:1–20.

Michailova,S.,&Mustaffa,Z.(2012).Subsidiaryknowledgeflowinmultinational

corporations:Researchaccomplishments,gaps,andopportunities.Journalof WorldBusiness,47:383–396.

Minbaeva,D.B.,Pedersen,T.,Bjo¨rkman,I.,Fey,C.F.,&Park,H.J.(2003).MNC

knowledgetransfer,subsidiaryabsorptivecapacityandHRM.Journalof InternationalBusinessStudies,34:586–599.

Morck,R.,&Yeung,B.(1991).Whydoinvestorsvaluemultinationality?Journalof

Business,64(2):165–187.

Mudambi,R.,&Navarra,P.(2004).Isknowledgepower?Knowledgeflows,

subsidiarypowerandrentseekingwithinMNCs.JournalofInternational BusinessStudies,35(5):385–406.

Mudambi,R.(2008).Location,controlandinnovationinknowledgeintensive

industries.JournalofEconomicGeography,8(5):699–725.

Mudambi,R.,Pedersen,T.,&Andersson,U.(2014).Howsubsidiariesgainpowerin

multinationalcorporations.JournalofWorldBusiness,49:101–113.

Ma¨kela¨,K.,Andersson,U.,&Seppa¨la¨,T.(2012).Interpersonalsimilarityand

knowledgesharingwithinmultinationalorganizations.InternationalBusiness Review,21:439–451.

Najafi,Z.,Giroud,A.,&Andersson,U.(2014).Theinterplayofnetworkingactivities

andinternalknowledgeactionsforsubsidiaryinfluencewithinMNCs.Journalof WorldBusiness,49(1):122–131.

Nelson,R.,&Winter,S.(1982).Anevolutionarytheoryofeconomicchange.

Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress.

Nohria,N.,&Ghoshal,S.(1994).Differentiatedfitandsharedvalues:Alternatives

formanagingheadquarters-subsidiaryrelations.StrategicManagementJournal, 15(6):491–502.

Nordman,E.R.,&Mele´n,S.(2008).Theimpactofdifferentkindsofknowledgefor

theinternationalizationprocessofBornGlobalsinthebiotechbusiness.Journal ofWorldBusiness,43:171–185.

Okimoto,D.I.,&Cargill,T.F.(1989).*BetweenMITIandthemarket:Japanese

industrialpolicyforhightechnology.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,24(4): 75.

Osborn,R.B.,&Baughn,C.C.(1987).NewpatternsintheformationofUS-Japanese

cooperativeventures:Theroleoftechnology.ColumbiaJournalofWorld Business,22:57–66.

Ostry,S.(1990).*Governments&corporationsinashrinkingworld:Trade&

innovationpoliciesintheUnitedStates,Europe&Japan.ColumbiaJournalof WorldBusiness,25(1):10.

Oviatt,B.M.,&McDougall,P.P.(1994).Towardatheoryofinternationalnew

ventures.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,25:45–64.

Ozawa,T.(1971).*JapanexportstechnologytoAsianLDCs:Traditionallyan

importerofwesterntechnology,Japanisbeginningtoexportherown technologytoneighboringAsianmarkets.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,6: 65–71.

Ozawa,T.(1972).*Japans’technologynowchallengestheWest.ColumbiaJournalof

WorldBusiness,7(2):41–49.

Patriotta,G.,Castellano,A.,&Wright,M.(2013).*Coordinatingknowledgetransfer:

Globalmanagersashigher-levelintermediaries.JournalofWorldBusiness,48(4): 515–525.

Pearce,R.(1989).Theinternationalizationofresearchanddevelopmentby

multinationalenterprises.NewYork:StMartin’sPress.

Petersen,B.,Pedersen,T.,&Lyles,M.(2008).Closingknowledgegapsinforeign

markets.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,39:1097–1113.

Petersen,B.,Pedersen,T.,&Sharma,D.D.(2003).Knowledgetransferperformance

ofmultinationalcompanies.ManagementInternationalReview,43(3):69–90.

Rabbiosi,L.,&Santangelo,G.D.(2013).Parentcompanybenefitsfromreverse

knowledgetransfer:TheroleoftheliabilityofnewnessinMNEs.Journalof WorldBusiness,48(1):160–170.

Rodrigues,C.A.(1985).*Aprocessforinnovatorsindevelopingcountriesto

implementnewtechnology.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,20(3):21.

Rondinelli,D.A.(1993).*Nationalinnovationsystems:Acomparativeanalysis.

ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,28(4):94.

Rugman,A.,&Bennett,J.(1982).Technologytransferandworldproductmandating

inCanada.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,17:58–62.

Rugman,A.,&Verbeke,A.(2001).Subsidiary-specificadvantagesinmultinational

enterprises.StrategicManagementJournal,22:237–250.

Raab,K.,Ambos,B.,&Tallman,S.(2014).Strongorinvisiblehands?Managerial

involvementintheknowledgesharingprocessofgloballydispersedgroups. JournalofWorldBusiness,49:32–41.

Scalera,V.,Mukherjee,D.,Perri,A.,&Mudambi,R.(2014).Alongitudinalstudyof

MNEinnovation:ThecaseofGoodyear.MultinationalBusinessReview,22(3): 270–293.

Schoonhoven,C.B.(1984).*Hightechnologyfirms:Wherestrategyreallypaysoff.

ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,19(4):5.

Schotter,A.,&Beamish,P.(2010).PerformanceeffectsofMNCheadquarters–

Subsidiaryconflictandtheroleofboundaryspanners:Thecaseofheadquarter initiativerejection.JournalofInternationalManagement,17(3):243–259.

Shenkar,O.(2001).Culturaldistancerevisited:Towardsamorerigorous

conceptualizationandmeasurementofculturaldifferences.Journalof InternationalBusinessStudies,32:519–536.

Shrivastava,P.(1984).*Technologicalinnovationindevelopingcountries.Columbia

JournalofWorldBusiness,19(4):23.

Simon,E.(1996).*Innovationandintellectualpropertyprotection:Thesoftware

industryperspective.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,31(1):30–37.

Steers,R.M.,Meyer,A.D.,&Sanchez-Runde,C.(2008).*Nationalcultureandthe

adoptionofnewtechnologies.JournalofWorldBusiness,43(3):255–260.

Sunaoshi,Y.,Kotabe,M.,&Murray,J.Y.(2005).*Howtechnologytransferreally

occursonthefactoryfloor:AcaseofamajorJapaneseautomotivedie manufacturerintheUnitedStates.JournalofWorldBusiness,40(1):57–70.

Tang,R.Y.W.,&Tse,E.(1986).*Accountingtechnologytransfertolessdeveloped

countriesandtheSingaporeexperience.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness, 21(2):85.

Tenzer,H.,Pudelko,M.,&Harzing,A.W.(2014).Theimpactoflanguagebarrierson

trustformationinmultinationalteams.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies, 45:508–535.

Tian,X.(2010).*ManagingFDItechnologyspillovers:AchallengetoTNCsin

emergingmarkets.JournalofWorldBusiness,45(3):276–284.

Tihanyi,L.,&Roath,A.S.(2002).Technologytransferandinstitutionaldevelopment

inCentralandEasterEurope.JournalofWorldBusiness,37:188–198.

Ting,W.(1980).*Acomparativeanalysisofthemanagementtechnologyand

performanceoffirmsinnewlyindustrializingcountries.ColumbiaJournalof WorldBusiness,15(3):83.

Tippmann,E.,Scott,P.S.,&Mangematin,V.(2014).Subsidiarymanagers’

knowledgemobilizations:Unpackingemergentknowledgeflows.Journalof WorldBusiness,49(3):431.

Tsurumi,Y.(1979).*Twomodelsofcorporationandinternationaltransferof

technology.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,14(2):43.

Tsurumi,Y.(1982).*Japan’schallengetotheU.S.:Industrialpoliciesandcorporate

strategieschallengetotheUSAposedbytheemergenceof‘‘groupcapitalism’’ keiretsu,emphasizingglobalmarketshareandthedevelopmentofproduction andinstitutionaltechnology.ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,17:87–95.

Wallender,H.W.(1980).*Developingcountryorientationstowardforeign

technologyintheeighties:Implicationsfornewnegotiationapproaches. ColumbiaJournalofWorldBusiness,15(2):20.

Wang,P.,Tong,T.W.,&Koh,C.P.(2004).Anintegratedmodelofknowledge

transferfromMNCparenttoChinasubsidiary.JournalofWorldBusiness,39: 168–182.

Wescott,W.F.(1993).*Environmentaltechnologycooperation:Aquidproquofor

transnationalcorporationsanddevelopingcountries.ColumbiaJournalofWorld Business,27(3):144.

Wijk,R.V.,Jansen,J.J.P.,&Lyles,M.A.(2008).Inter-andintra-organizational

knowledgetransfer:Ameta-analyticreviewandassessmentofitsantecedents andconsequences.JournalofManagementStudies,45:830–853.

Williams,C.,&Lee,S.H.(2011).*Entrepreneurialcontextsandknowledge

coordinationwithinthemultinationalcorporation.JournalofWorldBusiness, 46(2):253–264.

Zaheer,S.,&Nachum,L.(2011).Senseofplace:FromlocationresourcestoMNE

locationalcapital.GlobalStrategyJournal,1:96–108.

Zahra,S.A.,&George,G.(2002).Absorptivecapacity:Areview,reconceptualization

andextension.AcademyofManagementReview,27:185–203.

Zhou,L.(2007).Theeffectsofentrepreneurialproclivityandforeignmarket