Virtual Goods in Online Games

A study on players’ attitudes towards Lootboxes and Microtransactions in Online

Games

Author: Daniel Nielsen Examiner: Tina Askanius Examinated: 2018/06/11

Media and Communication Studies, one-year thesis 15 credits, Spring 2018

Abstract

The aim of this thesis is to investigate players’ attitudes towards microtransactions within online games. The thesis is based on a multi-method approach combining the following methods: focus group-interviews, interview questions posed to hosts of a podcast, for then to discuss in their episode, and a survey. The results of this study are a categorization of players’ attitudes towards microtransactions consisting of: Activist, Idealist, Agile, Pragmatist, Enthusiast and Compliant. By adopting de Certeau’s concept of strategies and tactics, I have elicited distinctive reactions and ways of meaning making towards microtransactions, associated with each proposed category. Apart from categorizing player attitudes, this study has also identified microtransactions to have brought the broader player base into the symbiosis that previously existed exclusively between fan-programmers, socialized players, and game companies. Meaning, feedback from the whole player-base is crucial for success in implementing microtransactions. In turn, this is perceived as a strategy that surrenders power from the producer to the user.

Keywords: Games, Players, Game Design, Microtransactions, Lootboxes, Tactics, Strategies, Attitudes

Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background... 2

1.2 Research Questions and Aim ... 6

2. Previous Research ... 6

2.1 Research on the Digital Economy and the Creative Industries, and the Place of Games in it ... 7

2.2 Research on the Game Industries ... 8

3. Theoretical Framework ... 9

3.1 De Certeau: Tactics and Strategies ... 9

3.2 Liboriussen: Craftsmanship ... 11

4. Method ... 12

4.1 The Structure and Collection of Material ... 14

4.1.1 Focus-group Interviews & Individual Interview ... 14

4.1.2 Survey ... 15

4.1.3 Podcast ... 16

4.2 Validity & Limitations ... 17

4.3 Ethics ... 17

5. Analysis ... 18

5.1 Establishing Categories ... 18

5.2 Categorization of Player Accounts ... 19

5.2.1 Activist ... 20 5.2.2 Idealist ... 21 5.2.3 Agile ... 23 5.2.4 Pragmatist ... 24 5.2.5 Enthusiast ... 25 5.2.6 Compliant ... 26

6. Discussion & Conclusion ... 28

6.1 Final Remark ... 30

Bibliography ... 33

Appendix 1 – Survey Results ... 36

Appendix 2 – Categorization of Survey Results ... 42

Appendix 3 – Focus-group Interviews, Individual Interview and Podcast Details & Questions ... 45

Appendix 4 – Focus-group Interviews, Individual Interviews and Podcast Transcripts ... 48

List of Abbreviations

MTX – MicrotransactionDLC – Downloadable Content

RRM – Random Reward Mechanism

PS – PlayStation

1

1. Introduction

In the recent years a range of online games, on PC, console, and smartphone, have been adopting new economic models for extracting value from gameplay. Where the conventional understanding of game companies generating income has been through selling the product in a hardcopy (also called premium games), alongside merchandise related to the game, the gaming economy is now experiencing the initial conventional purchase cost of a game, followed by an on-going requirement for purchasing downloadable content (DLC), if the player wishes experience the full game/product.

In this context, the game industry has been introducing even newer economic vehicles for profit generation, in the form of so-called lootboxes and Microtransactions (MTX). MTX is a business model for games, where players can buy virtual goods through micropayments.1 MTXs are often adopted by free-to-play games (also called freemium), as in free of initial charges upon download, as an alternative way of generating revenue. The purpose of MTXs is to close the gap between players that have a high amount of leisure time to spend on the game and players that have little leisure time to spend, as it provides the players with little leisure time the option of acquiring items and/or customizations through purchases, instead of spending time obtaining them through gameplay. Lootboxes are an expanding form of MTX. Lootboxes are consumable virtual packages that can be redeemed to receive a randomized selection of virtual items or content, which can range between items featuring avatar customization, to items that have a game-changing impacts such as virtual weapons and armor.

Lootboxes is one of the latest trends in a monetization development within the online game economy. And the randomized reward element2 of the lootboxes have been criticized over a long period of time by the gaming community which has set up the homepage Microtransaction.zone for players to quickly categorize games according to monetized content, to help assess purchasing calls (Simon, and Taylor). Microtransaction.zone can be seen as a collaborative media (Löwgren & Reimer, 2013) that represents the player community taking action against the new monetization model within games. Many see it to be a predatory business practice, as it is argued to be exploiting underage children and individuals with a tendency to develop an addiction for gambling (Knaus, 2017). This has received attention from authorities and governmental entities in The Netherlands (Kansspelautoriteit, 2017), Belgium (Huijbregts, 2017), France (Durain, 2017), the United States (Makuch, 2017) and Australia (Knaus, 2017). In addition, the Netherlands and Belgium as of April 20, 2018, have banned a number of games from offering the lootbox services to players in their countries (Lawson, 2018).

Some of the main directions that the debate has taken are the concerns of players, is whether these micro-purchases should be permitted to have an impact on the gameplay, considering that most of the games, that make use of lootboxes and MTXs, are competitive multiplayer games where advantage is understood to be something you acquire through experience and time spend on the game.

1 Small payment made online.

2 When purchasing a lootbox, the player is not certain of its content. This is the randomized element, and the gambling nature.

2 Another topic concerning the debate is focused on finding the definitions for when ornaments are or are not improving game-play or indirectly locking content behind a ‘paywall’3. An example would be the argument for why a purchased vehicle, taking a player’s avatar/character across the virtual space faster, is indirectly locking content behind a paywall as that limits the content-over-time available to the player who does not make use of MTXs.

When referring to online games, I consider the platforms such as computer, consoles such as Playstation (PS) and Xbox, and smartphones. The online games themselves are primarily of the type Massive Multiplayer Online (MMO)4 and Massive Multiplayer online roleplaying game (MMORPG).5

Lootboxes have not received attention in a degree to receive an academic conceptualization as of yet, although “Random Reward Mechanisms” (RRMs) have been debated as a potential conceptualization of the function behind lootboxes (Hornsby, et al. 2018). This conceptualization can be considered a “Skinnerian Mechanisms”,6 as it is game mechanisms that are arguably developed from Skinner’s principle of contingency. Skinner proved that intermittent reinforcement schedule, or random reward, is stronger at maintaining behavioral patterns as opposed to continuous reinforcement schedule which is better for acquisition: acquiring new behavior (Miltenberger, 2008, p. 86 & 87). In other words, continuously rewarding a player through gameplay will be less effective compared to sometimes, randomly, rewarding the player. This is what RRMs are, the Skinnerian Mechanism within lootboxes or other random reward element that incentivizes a player to repeat a specific activity.

Considering the fairly new entrance of this type of revenue extraction within the game economy, along with the controversy on MTXs in many countries as mentioned above – this thesis will direct its focus to the users of the games and, by using the methods of focus group-interviews and survey, to find out what their experiences and attitudes are towards this capitalistic turn within online games.

Before engaging with this question and the existing research on the topic, I will chart the background against which we can understand some of the economic, social and technological aspects of MTX and their development. In the next section, I will go deeper into ways of understanding the economic, social, and technological aspects of MTXs and its development.

1.1 Background

In this section, I will briefly touch upon the economic and in part, the technological development of the online games industry, in order to place MTXs and lootboxes in a broader context of media production and use. I start this background by taking an example of a topic previously mentioned above, namely the game industries new approaches to generating revenue. Thereafter, I propose potential roots to the introduction of MTXs within game development. And lastly, I outline the

3An arrangement whereby access is restricted to users who have paid.

4 Online game with a player base between hundreds to thousands. The game enables players to cooperate and compete, and it features huge persistent open virtual worlds.

5 MMORPG is similar to MMO, but features multiple avatars/characters that the player can adopt and roleplay. 6 Burrhus Frederic Skinner was an American psychologist, known for inventing the operant conditioning box, also known as Skinner’s Box.

3 various types of MTX approaches that players can come across while being online, in order to establish a more complex understanding of the MTX approaches that companies adopt and, in turn, suggest how this is deviating from conventional goods and use.

The change of conventional hardcopy sales to continued purchase of additional content is what Deuze, Martin and Allan refer to as the gaming industry transitioning from end-product to episodic content creation (Deuze, Martin, Allan, 2007, p. 339). The game industry with its implosion followed by rebirth in the 1980s (games moving from arcades to homes) has caused a great corporate pressure on profitability and need for constantly increasing revenue. This concern for maximizing capital return has also been criticized for influencing the industry to take less novel paths, which challenges scholars general understanding of the online game industry belonging within the creative industries (Hesmondhalgh, 2013, p. 244 & 245). In other words, the online game industry is less groundbreaking or visionary (Kerr, 2006), in terms of economic models following general patterns of value extraction adopted broadly in the creative industries. This economic model is referred to as the corporate strategy of conglomeration, where different parts of a corporation relate to each other and thereby provide cross-promotion and cross-selling (Hesmondhalgh, 2012, p. 166). More precisely, the releases of the gaming industry are “sequels, franchise titles or film adaptations, rather than unique games” (Deuze, Martin, Allan, 2007, p. 337).

MTX is a business model where users, or players, can purchase virtual goods at small sum costs, often between 1 and 10 €. Historically this model derives from the behavior of players trading virtual goods for real money which first really became a trend amongst players in 1999 (Hamari & Lehdonvirta, 2010, p. 15). The idea of selling virtual goods came from the Massive Multiplayer Online Games (MMOs) Ultima Online and EverQuest and was traded over consumer-to-consumer websites such as eBay (Ibidem). This trade of virtual goods did not just exist between leisure players, but also between leisure players and player-workers.

Player-workers are “virtual migrants”, mostly people from China who are employed to generate different types of valuable virtual content through repetitive and tedious tasks in gameplay, for then to sell this content to players, most commonly from the western hemisphere, for real money. These workers are often referred to as “farmers” within the online gaming communities (Scholz, 2013, p. 188 & 189). In relation to these “farmers”, the condemnation of buying virtual currency, by players, can be perceived as the first reaction of the more general player opinion, which is surfacing in the current controversy on lootboxes. Before MTXs were properly implemented as a business model in online games, “farmers” were the topic of controversy because it is “widely considered the worst, more morally reprehensible form of cheating” (Ibid, p. 188). What often seems to be condemned is the “farmers”, but essentially it is the service they provide and the players that make use of this service, that are the source to frustration from the online gaming communities, as this essentially is the element that can be considered “cheating”. Mia Consalvo in her book Cheating: Gaining advantage in videogames (2007) reveals that cheating is a concern for players but they struggle to find consensus as to what cheating is or is not (Consalvo, 2007, p. 150). And there are striking parallels to the controversy on MTXs/lootboxes and “farmers”, in terms of the arguments against MTXs/lootboxes. Instead of problematizing the players that make use of MTXs and lootboxes to gain

4 an advantage, the online game community raises arguments about how lootboxes are gambling, and in turn ethically irresponsible considering a big group in the gaming communities are underage children.

One of the first games to introduce MTXs, and be successful with it, was FarmVille, an Adobe Flash application via Facebook, developed by Zynga. FarmVille was launched in June 2009 with a player-base growing by more than a million weekly (Business Wire, 2009). This suggests that MTXs had not been properly established as a method of revenue generation, within game companies, prior to FarmVille.

MTXs was a business model that was first adopted by freemium smartphone games which was later adopted by premium games. However, Apple did not open its App Store before 2008, which is another suggestion for MTXs to be a relatively new phenomenon. After the launch the App Store, the app downloads increased exponentially from 2.5 billion downloads in 2009 to 150 billion downloads in 2013, and 270 billion in 20167 (Statista, 2017). With this much popularity, it is likely that MTX also took its foothold. The previous Chief Operating Officer of Electronic Arts, Peter Moore foresaw this development of MTXs becoming the primary business model for games in June 2012:

I think, ultimately, those microtransactions will be in every game, but the game itself or the access to the game will be free (…) there's an inevitability that happens five years from now, 10 years from now, that, let's call it the client, to use the term, [is free.] It is no different than... it's free to me to walk into The Gap in my local shopping mall. They don't charge me to walk in there. I can walk into The Gap, enjoy the music, look at the jeans and what have you, but if I want to buy something I have to pay for it. (Totilo, 2012)

So, arguably there exists a timeline for how MTXs came to be a central part of online games in the contemporary world of gaming. The intensifying revenue pressure on the online game industry, as well as, the search for alternative means of gaining profit, has led to the introduction of DLCs and MTXs.

This is the background for a development that has led to the problem of interest: lootboxes and MTXs. Again, to compare with the conventional understanding of premium games being a product to buy and play, the application of lootboxes and MTXs illustrates an additional changing marketing approach within the gaming industry.

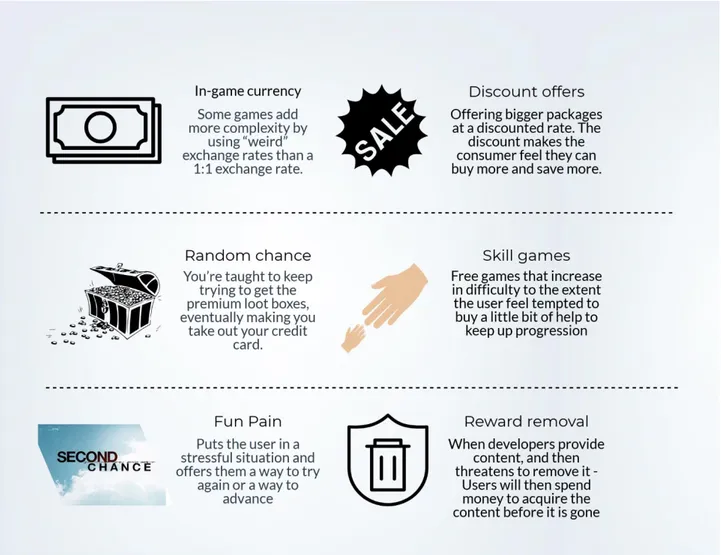

In figure 1 that is presented below, six types of MTX approaches, that have emerged so far and that a player can encounter in online games, are presented. These MTXs are often featured in any online games on mobile phone, PC or Console. All the types are not necessarily adopted by every game, as this is determined exclusively by the game developing company and based on the economic model they wish to adopt.

7 The development is perhaps due to the fact that the whole app-economy and apps in general started finally developing then, after introducing tablets/pads, as well as, new consumer tech.

5

In figure 1, six types of MTX approaches are illustrated. Players often make the distinction between MTXs that are cosmetics or have an influence on player performance, but these are considered different types of product offered, rather than approaches of incentivizing the player to make purchases. In online games, some of the MTX types put the player in a context that require him/her to make purchasing calls and to compare with Peter Moore’s example of walking into The Gap in the shopping mall without making purchases: If he were stopped in the shopping mall and prohibited from accessing the next floor unless he pays a fee, or if he had to pay to use the escalator instead of the stairs. – This is real world adaptations of the invasive nature that MTXs can have on players in online games.

In-game Currency is characteristic for virtual currency, comparable to electronic money or crypto currencies, it holds no legal regulations however and the supply depends on the issuer’s choice (Tomić, 2017, p. 247). The In-game Currency can be bought with real money at a certain exchange rate, the exchange rate has nothing to do with the virtual currency market value being different from the real currency of the player, the purpose of this exchange rate is to cause an opaque relation to the virtual currency when the user makes virtual purchases with it. Discount Offers, is package deals, often within a specific timeframe. The conventional discount trends in trade is related to supply and

6 demand, whereas in the case of virtual goods, there is no supply limits. Random Chance, is RMM which has already been explained extensively in the introduction. It incentivizes the player to make purchases for the chance of “winning”. Skill Game feature continuously rising difficulty in game-play, that eventually causes the play to have to seek help, in the form of MTXs, to keep up progression. Fun Pain is incentivizing element of putting a player in a stressful or challenging situation, where there is a high risk of defeat. Followed by offering the player a second chance, at a cost. Reward Removal is content that is offered during a short period of time, or content that has existed but are threatened to be removed. This makes players more likely to make the purchase, out of fear of not having the possibility at a later time.

This section has given a brief description of lootboxes and MTXs, and its development. It has lifted six types of MTX approaches, that can seem different, but the core mechanics are the same: to generate revenue within online games. More importantly, the section has outlined a change in marketing approach, from end-product creation to episodic content creation, and it is arguably this change of event that is causing a heated debate, which in turn has brought the debate to the level of governments. Below I present the research question and aim.

1.2 Research Questions and Aim

In the light of the above, and considering the presence of tensions between the game communities and the game industries’ new models for profit generation, the aim of this thesis is to investigate players’ attitudes towards MTXs within online games, and answer the following questions:

- What are the players’ attitudes towards lootboxes and microtransactions in online games? - How do players make sense of these new models of value extraction?

- What kind of reactions do these models provoke on the part of the players?

By answering these research questions, will contribute to a better understand the tensions that emerge between players and industries when creative industries, like the online game industries, introduce new models of value extraction.

2. Previous Research

Most existing research on online games focus either on the changing game economy and how it exists within a tight knit relationship with its consumers: the players. Or the focus is on the players themselves, and how their gameplay is very much related to life-projects and work. In relation to the game economy, scholars tend to think of games as a collaborative media and how this collaboration between players is increasingly being turned into means of profit generation for the game companies (Scholz, 2013). Other studies focus on what players do with games, either in the form of literally changing the games, these types of players are called fan-programmers (Postigo, 2007), or contributing to the universe and the atmosphere of the game through participation (Arvidsson & Sandvik, 2007). In this section of the paper, I will outline the academic field of which this study resides within, and provide concepts and knowledge about the study of games.

7 2.1 Research on the Digital Economy and the Creative Industries, and the Place of Games in it

Postigo (2007) and his paper ‘Of Mods and Modders - Chasing Down the Value of Fan-Based Digital Game Modifications’, elaborates upon the collaborative nature of the game industry by shedding light on a specific category of gamers, namely fan-programmers. Fan-programmers consist of modders, mappers and “skinners” who take on different game producing roles. Besides from categorizing the fan-programmer group, Postigo illustrates the additional value fan-programmers bring to a game and subsequently, to the producing company.

Postigo’s research on fan-based digital game modifications in broad terms conclude on a certain symbiosis existing between the game industry and the fan groups producing add-ons. Postigo explains the motivation for fan-programmers to produce content for already existing games, to be social in terms of artistic endeavor, community commitment, increasing the personal joy of playing the game by “taking” ownership, or personal identification by adding new cultural narratives (Ibid, p. 309). In addition, Postigo also concludes, that there are multiple potential gains for companies who embrace the fan groups as producers and game testers. At that time Postigo foresaw potential conflicts between these two entities if exploitation and injustice would be adopted, between the two, over ownership and copyrighted content (Ibid, p. 311). However, the exploration of such conflicts has not been a major theme in the subsequent research of gameplay culture, which instead has focused on, for example, consumer participation or co-creation within gaming or game-play not being passive entertainment or addiction but on the contrary immersion and craftsmanship.

Arvidsson and Sandvik (2007), with their paper ‘Gameplay as design: Uses of computer players’ immaterial labor’, in turn, provides an in-depth understanding of the relationship between the online game developers and the programmers, however, they take the conceptualization of fan-programmers one step further. According to Arvidsson and Sandvik, gameplay is a creative act of “bricolage where bits and pieces of media culture are creatively recombined or reflexively redeployed to produce something new” (Ibid, p. 4). Microtransaction.zone is an example of bricolage and redeployment.

Arvidsson and Sandvik defines gameplay as the acquisition of skill and knowledge, which they connect with the pace and eye-and-hand coordination skill alongside cognitive player requirements made by the game. Additionally, gameplay genres require different qualities from the player, for the player to acquire the socialization as a ‘competent player’ (Arvidsson & Sandvik, 2007, p. 8). Once the player has been socialized, the player’s agency becomes valuable in relation to the reproduction of media capital (Ibid, p. 6).

Arvidsson and Sandvik also identify another type of valuable agency, which they refer to as user-created content (Ibid, p. 15). This player-user-created content, such as guilds or clans8, are related to the online games and the challenges they pose to the players. These challenges require them to engage in a cooperative setting with other players.

8 While clarifying how not only fan-programmers’ contribution to specific online games are deemed valuable by the developers, but also how regular players social contributions are as well, Arvidsson and Sandvik’s argue that online games commercial value is to a large extent a product of the immaterial labor of players. Players are co-designers or co-developers (Ibid, p. 17), and this co-design or co-development exists not only within the virtual world of the game itself but reaches beyond the game whenever the players participate. In relation to MTXs, the immaterial labor suggests that players have a much higher impact on the success of online games which, in turn, makes the introduction of MTXs very sensitive. On the one hand the game producers need to adopt new ways of revenue generation, but on the other hand, MTXs can potentially result in less revenue if the immaterial labor and social contribution turn against the game developers, and instead of being a contribution to becomes a hindrance for success.

Another author whose previous work adds to the understanding of game industries and players, is Liboriussen and his paper ‘Craft, Creativity, Computer Games: the Fusion of Play and Material Consciousness’ (2013). As opposed to the conventional understanding of Homo Faber, as man the maker, Liboriussen emphasizes on curiosity and motivation in craftsmanship, and thus suggest an alternative interpretation of the conception as, man the creative. (Liboriussen, 2013, p. 276). Liboriussen applies this understanding of human to the player of online games. He makes the comparison between online gamers, their avatars/characters and craftsmen and their creations. The link he makes is the material consciousness, which is the anticipation of what is to come with the materials at disposal. The anticipation means being able to be one step ahead of the materials and see the bigger picture ahead. This stands in contrast to factory workers doing repetitive work, as well as gambling/lottery where you have no chance at predicting what is to come. He concludes that craftsmanship in games is the conscious process occurring when a player slowly constructs his/her character/avatar.

2.2 Research on the Game Industries

While the previous research so far has covered players embedded in game production and gameplay and craftsmanship similarities, Hamari & Lehdonvirta (2010) focuses on the online game developing companies. In their study, they attempt to outline the emerging marketing approach of MTXs of virtual goods, by comparing it to conventional marketing design. As they state early on “marketing can also be seen as an activity that creates needs” (Hamari & Lehdonvirta, 2010, p. 17). This is what seems to be permeating their paper, that opposed to conventional marketing, that makes use of big data and consumer segmentation. But in the online game industry, companies rarely need to explore the needs of their consumer base, because they themselves [the companies] set the terms for the players’ needs when determining the game mechanics.

Hamari & Lehdonvirta, in their study, mention game mechanics such as status restrictions9 and

increasingly challenging content10 as ways of enforcing game structures to direct the player behavior. (Ibid, p. 20). They raise inconvenient gameplay elements as another example of game design creating

9 Gradually making obtained items useless to the player. 10 Content increasing in difficulty

9 player needs, which is a game product possessing various limitations or inconveniencies deliberately to motivate the player to buy augmenting products [MTXs] to solve the “problem” (Ibid, p. 22). However, Hamari & Lehdonvirta suggest more complex methods for creating player needs by proposing persuasive technology, which is the use of technology to persuade change of behavior in players (Ibid, p. 27).

The mentioned scholars have gamers and the game industry, as field of study, as their common interest. They almost touch upon MTXs in this relation, but not quite extensively. The topic of MTXs, stands in relation to Postigo’s prediction of a conflict between fan-programmers and game producers. The symbiosis that the fan-programmers and game producers shape is arguably also encapsulating the casual players, as a result of web 2.0 and user-generated content having a huge impact on the game industry as Arvidsson and Sandvik emphasizes (2007, p. 15). However, the question that remains unanswered is the relationship between players and the online game industry. And that is the question, that I perceive the study to be contributing more insight and understanding towards.

3. Theoretical Framework

In order to understand the ways in which players react to and make sense of MTXs and lootboxes as new economic models in gameplay, I use Michel De Certeau’s (1984) theory of practices in everyday life. In particular, I draw on his key ideas on tactics and strategies. In addition, I adopt Liboriussen’s (2013) theory of Fusion of Play and Material Consciousness, to understand players’ meaning-making in online games. This section introduces the theoretical framework through which I approach the problem of MTXs, and how this framework is operationalized in relation to the analysis of the gathered material.

Below I first present the key ideas of de Certeau’s work on tactics and strategies, followed by an elaboration on Liboriussen’s concept of Craftsmanship in games.

3.1 De Certeau: Tactics and Strategies

By using de Certeau’s concepts of tactics and strategies I can get a better understanding of how new economic models for revenue generation in online games provokes reaction amongst players. I do this by analyzing and identifying tactics and strategy identifications within players’ accounts and attitudes towards MTXs in online games.

What concerned de Certeau is the act of consumption: what the consumer does with what he/she consumes. This stands in contrast to the general understanding of consumption being a passive act. He problematizes this understanding, for only observing the effects, meaning the quantity and place of consumption (Certeau, 2011, p. 35). Instead, De Certeau refers to consumption as another type of production: which is the utilization of the initial production (Certeau, 2011, p. xii & xiii). This means making practical or effective use of what is ready-to-hand, essentially using it in unexpected ways for other goals than the presumed ones, intended by the producer. The acts of utilization by the consumer, de Certeau identifies as tactics, are not merely consumption but instead another type of production because they do not obey the law of the “place”, offered by the producers.

10 The act of tactics is not defined nor identified by the producer (Ibid, p. 29), since they are considered unmappable as opposed to the strategies. To elaborate on this: opposed to the general notion of production being a paid service or object, de Certeau sees it as a hidden kind of production. This hidden production is in turn, “scattered over areas defined and occupied by systems of “production”” (Ibid, p. xii), such as television, urban development, and commerce etc. This means that producer strategies are visible to the user, but user tactics are not visible to the producer.

The other concept de Certeau lifts in the consumer-producer relationship is strategies. This concept is linked to the producers of a product. In the citation below, de Certeau explains strategies as:

the calculation (or manipulation) of power relationships that becomes possible as soon as a subject with will and power (a business, an army, a city, a scientific institution) can be isolated. It postulates a place that can be delimited as its own and serve as the base from which relations with an exteriority composed of targets or threats (costumers or competitors, enemies, the country surrounding the city, objectives and objects of research, etc.) can be managed (Ibid, p. 35 & 36)

What is stressed in the explanation above, is the power relationship between a dominant and a dominated. For the dominant to manage the dominated it needs to assume a place as its own, where interference is minimal. A dominant could be a city, which dominates its citizens to act within its set framework of roads, sidewalks, and streetlights. Hence, there can be a power balance between city and citizen. Although these roles might seem fixed, de Certeau argues that the roles can swap, and therefore change the power balance. When the roles swap, it is because the means of relation with an exteriority is weakening, and the strategist will, in turn, be able to adopt measures of deception, and ultimately be transforming strategies into tactics (Ibid, p. 37).

Returning to the first concept lifted, “[a] tactic is an art of the weak” and is “a calculated action determined by the absence of a proper locus” (Ibid, p. 37, both quotes). This means, a tactic is an act of the dominated, and it is always adopted when the presented options [by the producers] does not suffice the users’ needs. A tactic is depending on time, and the user does not have the power to impose will on the system at hand, so when the moment comes that the user can will something: when and how is determined by the circumstances of the situation (Ibid, p. xix). The user is, according to de Certeau, seeking out opportunities ‘on the wing’. And the user needs to master “clever tricks of the “weak” within the order established by the “strong,” an art of putting one over on the adversary on his own turf, hunter’s tricks, maneuverable” (Ibid, p. 40).

In relation to the study on player attitudes towards MTXs, one type of tactic cannot be exclusively identified as the hidden production. De Certeau stresses that, the tactic is always calculated and determined by the circumstances of the situation and this, in turn, also makes it difficult to identify for the producer, as well as, anyone else. Therefore, the act of purchasing MTXs, can be a tactic if the motivation is different from the intention of the producer’s strategy.

The player making sense of MTXs can also be a tactic, whether the reasoning is accurate it still serves the purpose of supporting the player in dealing with the domain of the adversary. These tactics are

11 types of hidden production in the sense that they utilize the offered product in a way that serves the player’s needs. What is important to stress is that, it is not the choice between either producer production and consumer production. The player can make use of both, although in theory s/he will always produce a hidden product, and not necessarily make use of the producer product.

In applying the concepts of strategies and tactics to players meaning-making of lootboxes and MTXs within online games, one can say that lootboxes and MTXs are marketing strategies. And the studios and companies producing the online games are the dominant subjects as the power balance favors them, in the sense, that they have access to and determines the proper place: the online game. Lootboxes and MTXs can then be perceived as the base of generating relations with an “exteriority”, which is the players playing the online games. In turn, tactics refer to what these players do with game elements related to lootboxes and MTXs, when playing online games.

While the power relationship favors the studios and companies producing online games, the players remain active users, and the focus of the study is on players direct or indirect accounts of how they actively engage with these online game elements related to MTXs. Hence, there are tactics, that the user uses to benefit from the product in ways that are not presumed by the producer of the game. In that way, the power balance is not fixed between these two parties – but shifting in relation to what tactics and strategies they use.

3.2 Liboriussen: Craftsmanship

As I have already mentioned in previous research, Liboriussen emphasizes the conception of human as Homo faber, the creative man, to underline how factory work, or repetitive work, is alien to craftsmanship. But to clarify this relationship between craftsmanship and creativity, he draws on Sennet (2008) and his work The Craftman. Sennet explains the necessity for the anticipation of what is to come and being a step ahead of the materials at disposal. This will provide meaning to the worker, which in turn is craftsmanship (Liboriussen, 2013 p. 277). Also, Liboriussen draws on Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi work: Flow: the psychology of optimal experience, to emphasize the transitioning

from challenge to mastery and then boredom. The craftsman will seek new challenges, whereas the worker in factory production is forced to repeat the work, and experience little fulfillment as well as diminishing creativity. Clear goals and feedback are crucial for achieving flow and micro-goals are the satisfying factor, not the end goal. Micro-goals are the precise measures, perfectly executed blows or neatly laid stones: they all move towards a bigger picture (Ibid, 278).

According to Liboriussen, craftsmanship in gameplay is in fact competition, roleplay11 and immersion. Craftsmanship and competition in gameplay occur in the case of avatar comparison since the avatar essentially is the masterpiece being crafted by the player. If the game is without avatars, there often exists other ‘things’ of “projective identity”: the players project in the making which additionally reflects values and desires of the player (Ibid, p. 280). One example is FarmVille, where the capabilities or capacities of the player’s farm in relation to other players can be perceived to be a

11 “the desire to play another role than oneself, or to lose oneself, by

12 competitive drive in craftsmanship, and in turn project the players values and ambitions. Lastly, Liboriussen sees the link between online games and craftsmanship through the loss of self or immersion. This is often perceived as excessive or addicted gaming, but according to Liboriussen, it might just be “temporary suspension of goal-directedness” (Ibid, p. 281). A patience for detail and long-term commitment, that can be hard to comprehend for outsiders.

In relation to MTXs, the theory of craftsmanship in games provides an initial understanding of players meaning-making when playing games. Also, MTXs are often purchases for the ‘things’ of projective identity, e.g. avatar/character, city or farm, which suggests why MTXs are different from buying more game contents such as DLCs. DLCs provide overall game extensions, whereas MTXs provide modifications for the ‘thing’ representing the players accomplishments and progression.

De Certeau’s and Liboriussen’s theory merge, when it comes to craftsmanship being the primary drive for certain player tactics towards MTXs in online games.

In this section I have brought up strategies, tactics and craftsmanship in games, these concepts provide a theoretical lens through which I will grasp the relationship between producer [game companies] and player, by analyzing how players respond to MTXs within online games.

4. Method

In this section I introduce the multi-methodological framework. Firstly, I will outline the different types of methods followed by a motivation of each method choice and what I received from using them. Secondly, I present the structure and approach for collecting the material, for each method. This is followed by some brief thoughts on validity and limitations, as well as, ethical considerations.

This study adopted five types of methods when collecting material: (1) Online focus group-interviews, (2) Offline focus group-group-interviews, (3) Offline individual-group-interviews, (4) Survey. In addition, the interview questions were sent to a (5) Podcast, which then debated them between the podcast hosts and the listeners/subscriber.

The multi-method approach was chosen based on my perception of studying player tactics to be relatively difficult. In the light of the controversy on MTXs, I thought that, getting players to elicit potential tactics were going to be time consuming and potentially cause irritation to the informants. The reason for it to be time consuming was that, I expected participants to not immediately understand what I meant with experience, avoidance and tactics. As a result, I estimated that I would spend most of the interview asking questions that eventually would lead the informants towards the focus of the theme, or comprehensive accounts, instead of general opinions (Kvale, 2007, p. 13). This search for comprehensive accounts, in turn, I assumed could potentially cause irritation amongst the informants, and therefore, I did not conduct interviews longer than 30-45 minutes. With the prospect that, interviews consisting of 30-45 minutes, would only provide 10-15 minutes of comprehensive accounts, and the fact that informants might not have anything to say that is relevant to the focus, I estimated that I would need a minimum of four focus group-interviews. Additionally, I made the compromise that one of these focus group-interviews, could be from the podcast, in case any of the

13 informants, I had reached out to, did not respond. These focus group-interviews turned into individual, online or offline interviews as a result of, as a researcher you need to go where the knowledge resides. Meaning, these three types of methods emerged by request from the informants.

Method 1, 2, 3 and 5 were qualitative research approaches. Qualitative research was considered a suitable method for the purpose of eliciting player attitudes in relation to MTXs within online games. Since qualitative internet research provides an opportunity of grasping multiple meanings and experiences related to a particular place or context, in turn, the aim of qualitative internet research is to question these meanings and experiences (Baym & Markham, 2009, p. 34). And method 5, was considered equal to that of qualitative interviews with an unstructured approach, since the podcast hosts were regular debaters of the online game Destiny, I presumed that their answers would be extensive.

Method 4 was a quantitative survey, with open-ended questions which permitted participants to elaborate on their thoughts, but also risked minimum answers. The motivation for conducting a survey as an auxiliary method (Kvale, 2007, p. 48), was to gain an overview of different attitudes towards MTXs. The survey results later turned out to be very helpful in structuring the analysis of the qualitative material, for the sake of clarity.

Focus group-interviews benefit from the social implications, where multiple informants share their viewpoints on a specific theme. One informant’s viewpoints might provoke new viewpoints in another informant. Information, in turn, becomes available through debate, as informants have to elaborate, specify or revise their initial statement(s) (Pickering, 2008, p. 71). Also, this approach avoids the deadlock of the interviewers’ questions being the only drive for discussion. This turned out to be very rewarding in the case of the offline focus group-interview, as is facilitated an unstructured interview approach where the informants would elicit valuable information through debate. This information I could not have thought of on my own when formulating the interview questions. However, focus interview was less beneficial in the case of online focus group-interviews, where I had to adopt a more semi-structured approach to the informants, and multiple probe questions were required to extract data at all. This can be due to the context of communication through Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC), which arguably removes certain elements of the social context that otherwise was the strength of focus group-interview.

The individual interview was adopted out of necessity, in the moment of collecting informants, I realized that I had not been able to reach any female informants. This made me forfeit my principle of chain-sampling, and contact an acquaintance directly. So, this method facilitated information not to be completely gender bias.

The case of the material collected from the podcast, was initially a matter of assuring material. With the timeframe set for this work, and informants being considerably slow in getting back to the requests, I had to improvise. And the material from the podcast was adopted as additional material compatible with the focus group-interviews as the hosts engage in debate weekly when creating their podcast episodes, therefore, I felt assured they would be able to discuss the questions extensively and “draw out the finer similarities and differences underlying the generalized consensus” (Pickering,

14 2008, 74). Placing the podcast as either written or oral interview categorization is not entirely possible. On the one hand, the interviewer/moderator is not present when the interview is being conducted, and it is therefore not possible to come up with probes or prompts to further certain comprehensive accounts that is deemed valuable to the study. On the other hand, the interview is still conducted orally and debate occurs between the three hosts.

In the study of player attitudes towards MTXs, I generated general knowledge of the world of players through focusing on the informants meaning-making of MTXs and by interacting with the research informants and their “life-worlds” through focus group-interviews (Pickering, 2008, p. 70). Adopting de Certeau’s concept of tactics and strategies, and in turn using the concepts of consumers and producers, it is important to stress that “participants are seen as active meaning makers rather than passive information providers, and interviews offer a unique opportunity to study these processes of meaning production directly.” (ibidem).With participants as active meaning makers as the point of departure, I introduce the research paradigm. Interpretivism emphasizes the social reality of participants and informants, and the meaning they produce and reproduce out of necessity in everyday practice. The interpretivist in turn construct models of typical meaning making that have been discovered in the research process (Blaikie, 2009, p. 99). This, also goes in line with the ontological assumption of idealist: that social reality is made up and shared between social actors (ibid, p. 93). As well as, the epistemological assumption of constructionism: that this production of meaning making by social actors, are also the knowledge the social scientist discovers and reinterprets into technical language (ibid, p. 95).

4.1 The Structure and Collection of Material

In this subsection, I present the generic information about the informants and participants and how I went about in collecting the material for the respective method. All the material was collected in the time between April the 11th and 28th, 2018. And the total amount of interview informants was eight, fifteen survey participants and three podcast hosts. The total gender representation was 26 being male and one female.

4.1.1 Focus-group Interviews & Individual Interview

The interviews were conducted on eight informants, all being players of various online games. The interviews consisted of three focus group interviews and one individual interview. The interviews consisted of total 6 Swedish informants and 2 Danish informants. I refer to appendix 34 for details.

One of the focus group interviews and the individual interview were conducted offline, where the remaining two focus group interviews were conducted online using the recording software Amolto Call Recorder. Of the two offline interviews, one was conducted in Southern Sweden, at the home of one of the informants, while the other was conducted in Malmö public space.

The informants were reached by chain sampling which means, one informant was reached out and asked to contact other informants s/he saw fit for the group interview. This facilitated a dynamic and active group interview since the informants were not strangers to each other.

15 The informants were not selected based on their knowledge around microtransactionsMTXs or online games. The criteria for the informants to qualify for the interviews, both online and offline, where their capability to understand the concept: microtransaction. This was understood to be adequately suggesting that the informant had been in some form of contact with MTXs in online games. In one case, two informants decided to leave an interview because they realized that they had not experienced MTXs. This exemplifies the approach that was adopted, that informants were not preselected based on the certainty of their knowledge of the phenomenon at hand.

The interviews were unstructured or semi-structured with open-ended questions. The aim was to obtain accounts of player attitudes in relation to MTXs when playing online games. The informants were first asked if they knew what MTXs were. Most informants related it to lootboxes or RRMs, which gave me a chance to elaborate on other forms of MTXs (see fig. 1). Secondly, the informants were asked about platforms (PC, Console12, or Smartphone) and games they have played/play on. These initial questions were posed, to be able to, analyze and compare the player accounts depending on the platform or game that the player was familiar with.

The first focus group-interview became a pilot study. After the interview, I reevaluated the unstructured and semi-structured approach and questions, for then to rework them to match the new insight I had acquired.

To elicit the player attitudes towards MTXs within online games, I asked the informants what they thought of MTXs within online games. This was followed by an acknowledgment that it was all valid viewpoints, but that I was trying to get a sense of the user experience, literally, the experience the player had whenever s/he encountered MTXs directly, or encountered elements related to MTXs. After the informants attempt to elaborate on more specific experiences, I asked the informants about their personal usage of MTXs, followed by requesting them to describe their motivation for buying or not buying MTXs. After that account, I asked the informants about their initial reaction to MTXs, for example in the case of opening a lootbox or being exposed to various types of MTX advertisement. This question was then followed by the more theory related question “have you adopted any methods to avoid/prevent microtransaction offers?” and lastly, I asked if the informants had been watching any videos, read/written on any forums or created any content around MTXs.

Keep in mind that the interviews were either unstructured or semi-structured: at any chance given I let the informants talk freely about the subject, as the goal was to gain as much information as possible. Therefore, the only principle I adopted was to assure that they talked about their experience instead of other things such as motivating the flaws in MTXs by giving examples of other players, such as the 19-year-old who spend $ 10,000 on MTXs in Battlefront (Gach, 2017). For more detailed information on how the interviews were conducted, I refer to appendix 4.

4.1.2 Survey

The survey was conducted on 15 participants, all being players of various online games. The age of the survey participants was between twenty-one and thirty-nine, and the nationality composition was five Danish and seven Swedish, one Dutch and one Italian.13

12 Xbox, Nintendo and PlayStation (PS)

16 The participants were reached the same way as the interviews, by chain sampling, I sentd out themy survey to individuals I had been in contact with previously, in relation to online games, and asked them to answer themy survey and sendd it to individuals within his/her network. Additionally, the podcast host posted the survey on their Facebook page and encouraged their listeners to take part. To clarify, I did not send the survey to themy interview informants as I considered that to be a form material duplication.

In conducting the survey, I adopted similar questions to that of the interviews but sought out the possibility of categorizing the participants within player segmentations, by asking the participants which category they associated themselves with the most (see appendix 5 for details on player segmentation). Then I asked for participants purchase habits of MTX, followed by asking them which of the six MTX characteristics (illustrated in fig. 1) they mostly encountered. Then I asked the participants in what context they often encounter MTXs, followed by requesting them to describe their initial reaction to these encounters. And lastly, I asked the participants if they adopted any methods to avoid/prevent MTXs during gameplay, followed by a question on them to explain why they think MTXs have or have not changed their gaming experience. The survey consisted of 19 questions, and the answers varied between thorough and long responses to very short or yes/no answers. This could be due to the open-ended questions, which is not ideal for a survey. For more details on the survey questions and structure, I refer to appendix 5.

4.1.3 Podcast

The podcast interview was conducted on three hosts of the podcast: De Danske Guardians (the Danish guardians), which features weekly episodes on the online game Destiny 2. The hosts regularly play the online game Destiny 2, on the console. And being the hosts of weekly podcasts, they debate all aspects of this online game, e.g. lootboxes and MTXs. The three hosts are all from Denmark. The questions were sent to them on April 11th, 2018, and they answered them in their episode on April 12th, 2018. The episode lasted two hours, while the hosts discussed my questions 40 minutes of that time.

The podcast material was acquired by sending the hosts a number of questions related to my thesis aim. Since they were questions for discussion in a public podcast, I thought it necessary to adapt them for clarity and make them easier to answer. The first question was related to immediate reactions and feelings when a player experiences their gameplay directly or indirectly interrupted by MTX offers, as well as feelings towards content being framed around MTXs. The second question was on potential conscious or unconscious adaption to the commercial circumstances of MTXs. Followed by example questions specifically related to Destiny 2.14 Lastly, I asked if they experience any types of community fragmentation due to MTXs, followed by example questions such as “is it suddenly bad taste to have MTX equipment on?” For details on questions posed to the hosts of the podcast, I refer to appendix 3.

The interviews and the podcast material were transcribed and analyzed using Certeau’s concepts of strategies and tactics. These concepts were then adopted in a thematic coding process, that was split

14 Is it 100% acceptance? Or do you avoid Tess [MTX vendor in Destiny 2] and thereby the Tower [social space in Destiny 2]? Do you ignore incentives such as 3x weekly experience rate [progression bar that awards a lootbox per completion]?

17 up in three steps. In the first step, each interview was treated as a single case where statements and narratives were connected to the concepts. In the second step, each interview was analyzed for “emerging codes”, to see the interview independently from Certeau’s concepts, to potentially make visible material that could be suggested as alternative or complimenting strategies and tactics. In the third step, the interviews were compared with the remaining material in order to see similarities or differences.

The survey material was transcribed and analyzed in the same manner, although the thematic coding process was done by color coding accounts and categorizing them into themes, which resulted in the six categories of player attitudes.

4.2 Validity & Limitations

In terms of validity, I have come across two potential issues in conducting the interviews, and one in relation to conducting the survey. Firstly, there is the risk of informants not feeling like they know enough about microtransactions to be able to contribute. It can be challenging to pose the right questions, in the right way, for not to make the informant feel insufficient in his/her contribution. This is the challenge of posing yourself as an equal or less to the interviewee and not a levitated entity. This also stands in relation to the other potential issue, that the participation in the debate might affect the opinions of the informants, and that I unconsciously favorized prompts and probes for specific individuals, and in turn failing to bring forth informants that were not as active as others. In relation to the survey, there is potential for a breach of validity as the chain-sampling approach started at acquaintances that resides within my social sphere of online games. While I personally had not been in contact with these acquaintances for the past eight years, there is still the risk of overrepresenting one gamer segmentation over another.

In terms of limitations, this study cannot assure equal representation of online players attitudes towards MTXs. As Deuze et al. (2007, p. 348) have established, there exists multiple types of players, or gamers. For further studies, it would be beneficial to make more participation criteria. Another matter of limitations, is looking in retro perspective at the interview questions. It was only after collecting the material and analyzing it, that I discovered the link with Liboriussen’s concept of craftsmanship in games, which I think could have brought forth more insight on players’ attitudes and reactions towards MTXs, had I formulated a question(s) around this theory.

4.3 Ethics

In conducting the interviews, all informants were informed about the study and its aim prior to commencing. This was followed by more details on the nature around the writing of the thesis, such as information about defense of the thesis and that the thesis will be available publicly at a later point. This was to give the informants an idea about how many people that will potentially be reading the study, and to underline that it will be available online in the nearest future. Then I explained in detail how I approached the analysis, as in, how the theories influenced the analysis of the material. This was to provide the informants with an idea about how their accounts would potentially be interpreted, as well as, which accounts that would be included and which that would be excluded. This all worked to the point of making the informants know that they were being studied, how they were being studied and, in turn, provide inter-subjective control to the informants (Kvale, 2007, p. 30).

18 Then I explained the principles of confidentiality, that data in the material that would potentially identify the subject, would be excluded from transcripts and later analysis (Ibidem). Thereafter, I asked the informants if they still wished to participate, and if they wanted anonymity, I also assured that the material would not be used for anything else but this study, and that the material would be destroyed after end thesis. Some of the players’ profession as game developers made it very sensitive for them to participate unless anonymity was assured. This sensitivity caused my decision of complete anonymity amongst the focus group-interview informants, as arguably anonymity lose its weight if only one informant is presented as anonymous, then it is already possible to isolate the anonymous informants accounts.

The hosts of the podcasts were informed about the study and its aim prior to sending the questions, and that they could, at any time, withdraw or omit any questions. In terms of confidentiality, the hosts of the podcast agreed to their environment [the podcast] being public and that they would be referred to by name (Baym & Markham, 2009, p. 73).

5. Analysis

In this section, I will present the main results and analysis from the thesis. Firstly, I introduce six categories I have established, based on the survey material. The categories represent the players perspectives and attitudes towards MTXs and lootboxes. Secondly, I strengthen these categorizations by drawing on the data from the qualitative focus-group interviews and individual interviews, alongside the data from the podcast. Simultaneously, I draw on de Certeau’s concepts of tactics and strategies, to elicit their unique appearance depending on the category of attitudes I refer to. However, the sampling is non-representational, as it only serves as a help in identifying distinct types of tactics. Also, an informant has multiple attitudes, these attitudes can fall into different categories, a category is explicitly reserved for an attitude and is not related to the player exclusively. In other words, a player can present more than one attitude at the same time.

5.1 Establishing Categories

When I analyzed the material, specific attitudes appeared repeatedly in the informants’, as well as participants’ accounts. Some players for example expressed not just contempt but also an agenda directed at specific companies. While other players expressed more than just acceptance or joy, but also thought of MTXs as an enriching factor in their game-play experience. Through thorough examination of the survey material, six categories were generated: (1) Activist, (2) Idealist, (3) Agile, (4) Pragmatist, (5) Enthusiast and (6) Compliant. For more information on how these categories were generated, I refer to appendix 1 & 2. When I refer to one of the six attitudes, I refer to that specific expression or behavior that is describe and it is that expression or behavior that is identified as activist, idealist, agile, pragmatist, enthusiast, or compliant.

The Activist is identified as accounts that resonate negative reaction. The Activist accounts reflect general contempt towards the implementation of lootboxes and MTXs. However, what makes these accounts stand out from being purely disapproval, is the action as opposed to inaction. The players have identified an antagonist which in this case is EA, Blizzard, Ubisoft and Activision, as well as estimated their means of confrontation: through boycotting or complete refusal of MTX offers.

19 The Idealist is identified as accounts of ideals. As in, how things are supposed to be in ideal form. The Idealist accounts suggest ideas to the ideal form of games, or players engaging in game-play. For example, one account suggests that gaming should be about gaming, hence not bothered about MTXs. This also insinuates that MTXs, according to this account, is not an established part of the game itself.

The Agile is accounts that reflect flexibility. As in, acceptance of lootboxes and MTXs, although adopting workarounds or compromises. The Agile accounts accepts the MTXs as an integral part of the game, on the premise that they can avoid them and still play the game, or that the MTX approach comply with certain principles, such as, reasonable pricing, possibility of playing without having to buy MTXs, generating in-game currency to work towards MTX related content and MTXs being purely cosmetics.

The Pragmatist’s reasoning emphasizes practical considerations for lootboxes and MTXs influence on game-play. The Pragmatist accounts resonate little argumentation. The player buys MTXs due to either of these reasons: it provides a sense of joy, advantage, saves time, desire. Or they do not buy MTXs due to it being waste of time, not worthwhile, or they want to know what they are buying, which the RRM effect of lootboxes does not permit.

The Enthusiast is identified as accounts that resonate positive acceptance as well as benefits with the new business models of lootboxes and MTXs. The Enthusiast accounts are positive towards MTXs and lootboxes, and emphasize the individual benefits through joy of crafting your character, as well as benefits for the community through economic contribution to the game company, in turn, to the community.

The Compliant are accounts that reflect negative acceptance, due to little prospect of alternatives. The Compliant accounts reflect contempt towards lootboxes and MTXs but accept the business model anyway. The short responses insinuate reflective exhaustion, or in other words, shortage of alternatives available to the player. The accounts are therefore short statements of hatred, dislike or annoyance.

In this subsection, I have introduced and analyzed the categories of player attitudes towards lootboxes and MTXs, based on the survey results. In the subsequent subchapter, I develop further on these categories, by drawing on the material from the focus-group interviews, individual interviews and podcast material. Additionally, I adopt de Certeau’s concepts of strategies and tactics to elicit how these differ depending on the specific category of attitude.

5.2 Categorization of Player Accounts

The six types of player attitudes towards lootboxes and MTXs are not mutually exclusive as overlaps occur, there are however distinct qualities that separate them from one another. And these distinctions are important to reach depth in the analysis of tactics and strategies. This creates the base for “comparability and the ability to offer analyses that can be coordinated with others” (Baym & Markham, 2009, p. 175). In this subsection I draw on the material from the focus-group interviews, individual interview and podcast, to strengthen the categorization and elicit strategies and tactics. I refer to appendix 3, for an overview of the informants and their subsequent statements that I cite throughout the analysis.

20 5.2.1 Activist

The Activist category reflects de Certeau’s emphasis on consumers not being passive, but instead active. While this is not unique to this category, it is the one type [the activist] of active consumption that is the most immediately visible. This type of attitudes can be of considerable value to the game and its developers, as Arvidsson and Sandvik suggest (2007, p 15). It is the casual player and his/her social contribution to the game, not to mention user-generated content related to the game and other forms of players participation in this content. To exemplify I draw on an account from informant G:

I read a lot about it [MTX], sometimes I also participate in the debate by putting up a post. – it is because I feel that the companies are exploiting me as a consumer. (Informant G)

This player participation as a result of an absence of “proper locus” (Certeau, p. 37, 2011), can arguably be severe to the creators of the game, as the new product that emerges through the “bricolage where bits and pieces of media culture are creatively recombined or reflexively redeployed” (Arvidsson & Sandvik, 2007, p. 4), can shake the “… place that can [otherwise] be delimited as its own and serve as the base from which relations with an exteriority composed of targets or threats […] can be managed” (Certeau, 2011, p. 35 & 36). In other words, when the user-generated content and the social contribution by casual players, redeploy a new product around the game, the game creators risk losing the place delimited as its own, because they do not hold exclusive power of public relations any longer, and in turn cannot adequately manage the relations with an exteriority. The redeployment of a new product can be user-generated content such as blog posts, YouTube videos or podcasts, or simply forum participation. While this can be negative for the game creators, it can also be positive if the players are satisfied with their locus/product. And this suggests the casual gamer to achieve a status similar to that of the fan-programmers and their mods, maps and “skins”, that helped in prolonging the lifetime of games (Postigo, 2007, p. 308). The diminishing control over the place by the producer, suggests what de Certeau claimed, that the role of adopting strategies and tactics can swap, meaning the users, in this case, the players adopt strategies such as user-generated content and social contribution, to take hold of a proper place. As a result, the producer must adopt measures of deception, ultimately transforming strategies into tactics (Certeau, 2011, p. 37).

The first results of this shifting power relationship between producer and consumer are expressed in informant A’s claim:

It has become a selling point, one year in advance developers they announce that their upcoming game will not have microtransactions. And everybody seems to think that will determine if it is a good game. (Informant A)

Informant A’s claim suggests that it is not the consumers that are masters of “hunter’s tricks, maneuverable” (Certeau, 2011, p. 40). But instead it is the producer that attempts to use tricks and maneuverable and appeal to the assumed needs of the consumer.

Focus-group 1 have extensive insight as to the community, the games and the development of MTXs, lootboxes as well as DLCs. This exemplifies the activist attitude, as they are taking an active role in understanding and creating an opinion about MTXs and lootboxes, and the revenue strategies related to it. Informant B for example, have very detailed ideas about the strategies of the producers: