Kurdish female fighters versus ISIS -

A textual and image analysis

Program: MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION STUDIESCourse: Master’s Thesis in Media and Communication Studies

Malmö University Date: 30.10.2020 Supervisor: Michael Krona Course Director: Erin Cory Examiner: Jakob Friedrich Dittmar

Student: Perisan Kevci Word count: 16.247

Keywords: Kurdish female fighters, YPJ, media representation, new paradigm, ‘jineoloji’, Kurdistan, Middle East, ISIS

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 5

2 Background ... 6

2.1 Who are the Kurds? ... 6

2.2 Who are ISIS? ... 8

3 Previous Research ... 10

4 Theoretical Framework ... 15

4.1 Theory of Representation ... 15

4.2 Gender Theory ... 17

4.2.1 Gender Roles in Western Media ... 18

4.2.2 The Search for ‘Real Women’ ... 19

4.3 Kurdish Theory and the Concept of Women’s Liberty... 20

4.4 Methodology ... 24

4.5 Research Design ... 27

4.5.1 Visual analysis ... 29

4.5.2 Content analysis ... 30

4.6 Ethical Issues ... 30

4.7 Role of the Researcher ... 31

4.8 Reflections ... 32

5 Analysis ... 33

6 Discussion and Conclusion ... 52

7 Bibliography ... 57

Letter to the examiner, Mr. Jakob Friedrich Dittmar

Thank you very much for your response to my thesis.

I have tried to address all your comments. Due to time restrictions, I could not address some of the smaller comments. The changes that have been made are highlighted in yellow. It was a marathon against time and I am sure if I had more time, I would be able to implement all your comments. It is very yellow in the text, which show that I have tried to integrate all comments that I received from you.

Abbreviations

ISIS Islamic State in Iraq and Syria IS Islamic State

YPG People’s Protection Units YPJ Women’s Protection Units PYD Democratic Union Party PKK Kurdistan Worker’s Party KRG Kurdistan Regional Government

Abstract

The relationship between media, gender, war, and society has been the subject of much research, with the primary focus being on the analysis of media texts. Kurdish female battalions (YPJ) have received considerable international media attention. The role of female fighters in the conflict in the Autonomous Administration of North and

East Syria, also known as Rojava, is different from what normally is perceived in the Middle East. These fighters have established a life according to the doctrine of 'jin', 'jiyan', 'azadî' –Kurdish words for ‘women’, ‘life’ and ‘freedom’. This study examines the representations of Kurdish female fighters struggling against ISIS, with the aim of answering the following questions: Which of the multiple interpretations of Kurdish female fighters are conveyed? How have these female fighters been represented in UK and US media? To answer these research questions, content and visual analyses were conducted. Data consisted of news articles from national media outlets in the UK and US. The data was examined with a frame analysis. The results showed that the

juxtaposition of Kurdish female fighters with ISIS terrorists allowed for their depiction as exceptional and heroic.

1. Introduction

Media representation is a complex concept. Hall (1997), who made great contributions to our understanding of the concept, has said that representation connects meaning and language to culture. The relationship between media, culture and society has been the subject of numerous studies.

One of the world’s most brutal terrorist organizations, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), was first given international news coverage in 2011. This organization garnered considerable attention in the global media. Since then, countless research papers and dissertations have focused on the brutality of this organization. Far fewer studies have focused attention on the Kurds, especially Kurdish female fighters, who were major partners of the global alliance to fight ISIS.

Since 2013, many Kurdish female fighters in Rojava, the Kurdish self-ruled region of North-Eastern Syria (officially called the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria), have fought against ISIS as part of Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) – all-female battalions falling under the umbrella organization of the People’s Protection Units (YPG). Their battle can be summarized with the Kurdish words ‘jin’, ‘jiyan’, ‘azadî' – ‘women’, ‘life’ and ‘freedom’ – which also summarizes their ideology.

This thesis investigates how Kurdish female fighters struggling against ISIS are represented in news coverage. Few studies have focused on Kurdish female fighters; thus, the aim of this thesis is to contribute to current research and discussions. The overall aim of this study is to attempt to understand and frame the analysis of Kurdish female fighters’ war against ISIS, and discover the hidden force that may contribute to victory against one of the biggest threats to the people and stability of the Middle East.

Kurdish women have been integral to the survival of the Kurdish people, who remain the largest nationality without a state and are often rendered invisible historically. While there are no reliable statistics, most sources suggest there are around 40 million Kurds. Over the last few years, many news stories, reports, and photos have been published on Kurdish fighters in Rojava. Several of these reports highlighted women’s participation in the armed conflict.

This study is about the media representations of Kurdish female fighters and their participation in the war against ISIS, with a focus on US and UK media from 2014 to 2019.

The main research questions were as follows:

- How are Kurdish female fighters struggling against ISIS represented in US and UK media coverage? – a textual analysis

- Which of the multiple interpretations of Kurdish female fighters are conveyed visually? – an image analysis

The first research question is highly western perspective, and the established myths about fighters must be taken into consideration, which comes from the postcolonialism, the ‘historical period or state of affairs representing the aftermath of Western

colonialism; the term can also be used to describe the concurrent project to reclaim and rethink the history and agency of people subordinated under various forms of

imperialism’ (Britannica, 2020). The western cultural frames shall also not be neglected when it comes to the representation of the Kurdish female fighters. Everyone sees from their windows and their interpretation.

After presenting the theory underlying my analysis, I discuss the methodology. Then, I present the results and outline my main conclusions. The results show that female

fighters are represented in UK and US media as sexualized, modern-day heroine figures.

2. Background

2.1. Who are the Kurds?

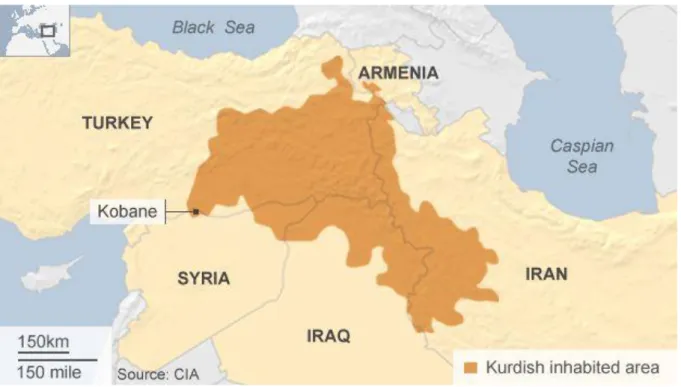

To answer the question of who Kurds are, it is helpful to have a map to hand. However, it must be underlined that millions of Kurds have been displaced forcibly across Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria:

Figure 1. Map of Homeland of Kurds, source bbc.com

Kurds are one of the indigenous peoples of the Mesopotamian plains and highlands, in what is now officially called south-eastern Turkey, north-eastern Syria, northern Iraq, north-western Iran, and south-western Armenia. The Kurdish diaspora has settled mostly in Europe and Northern America (Baser, Toivanen, Zorlu, & Duman, 2019, p 13).

However, the Kurds are forced to be bilingual due to the strict assimilation policies of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Many Kurds are not able to get medical help if they are not able to speak the official language of the country, they reside in. However, such cases are rarely recorded in official statistics.

The Kurdish language in public life was banned in Turkey officially until the beginning of the 2000s. It is notable that such political, linguistic, and other forms of oppression remain visible today. Kurds have even been killed because ‘of being Kurdish’; for example, in 2015, a young Kurdish man, Selim Serhed, was killed by Turks after singing in Kurdish at a stage in Istanbul. (Diyarbakirsoz.com, 2015).

One of the longest Kurdish uprisings – which continues today – has been driven by the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK). The military war against Turkey started in 1984 with

the aim of creating a nation of Kurds in Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq, exactly where they have always lived (ui.se).

The PKK has waged a military struggle for Kurds to receive the same rights as Turks, Arabs, and Persians, alongside the emancipation of Kurdish women. It is noteworthy to underline that the PKK is outlawed by the European Union and the United States of America (Official Journal of the European Union, 2009; US Department of State, Bureau of Counterterrorism, n.d.). As a result, some states regard them as ‘terrorists’, whereas others see them as freedom fighters.

Kurds within Rojava, a region in north-eastern Syria, were somewhat forgotten until they organized themselves and filled the vacuum left by the withdrawal of the Syrian regime from the region in 2012. In 2014, they received global attention when they began fighting ISIS (Baser et al., 2019, p 16).

Kurds in Rojava succeeded in establishing an autonomous system of governance that challenged the traditional system of the nation states in the area. This model, developed based on the ideals of the jailed leader of the PKK, Abdullah Öcalan, emphasized bottom-up democracy, active citizenship participation, and equal representation of men and women (Baser et al., 2019, p 16).

2.2. Who are ISIS?

The terrorist organization Islamic State (ISIS) emerged as an off-shoot of Al-Qaeda in Iraq soon after the 2003 US invasion. ISIS was shaped by a Jordanian jihadist, Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, who later became the head of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. The aim of this organization was to fuel war between Sunnis and Shiites and then to establish a

caliphate (Moubayed, 2015, p 12/97). While Al-Zarqawi was killed in 2006, his vision was realized in 2013–2014, when ISIS overran South Kurdistan (officially called Northern Iraq) and north-eastern Syria in just a few weeks (Moubayed, 2015, p 12).

The ideological roots of ISIS, Moubayed (2015) argues, can be traced back to the early years of Islam. Islamists believe that the goal of true believers is to establish a state

ruled by the laws of Sharia and governed by a caliph. This goal has been passed down through generations of Islamists (2015, p 12).

In mid-2014, ISIS launched attacks in Rojava. These attacks were repelled by the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), a female-only military unit affiliated with the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD)

(Moubayed 2015, p 197). After ISIS advanced into the Kurdish areas of Northern Iraq in August 2014, several offensives were launched in other areas. Towns inhabited by minority groups like the Kurdish Yezidis fell into the hands of jihadists. In one such town, Shengal (officially named Sincar), ISIS jihadists killed or captured thousands of Yezidis. The Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga of the Kurdistan Regional Government both withdrew from these areas, leaving ISIS to massacre the populace (Moubayed 2015, p 197).

The YPJ and YPG were able to establish a humanitarian corridor for thousands of Kurdish Yezidis from areas around Shengal, allowing them to escape. Subsequently, the PKK and KRG sent forces to defend Yezidi areas and drive out jihadists (Civiroglu & Salih, 2014).

ISIS is not just a terror organization wanting to create a caliphate in the Middle East. It positions itself against the rest of the world, notably by taking issue with Western rules and norms. The character of this organization is exemplified by the now-infamous video released in August 2014 showing the beheading of kidnapped US citizen James Foley (Krona & Pennington, 2019). In the video, Foley, depicted in an orange jumpsuit, is forced to read a scripted message addressed to the US state, while a jihadist (later called Jihadi John) blamed the US for Foley’s death. This video soon went viral (Krona & Pennington, 2019, p. 1-2). While the video was dubbed as a ‘message to the US’, it seems pertinent to it a message to the whole world – it was a critique of how a handful of wealthy people financed and used the poor in the Middle East as instruments for their inhumane politics.

However, the war waged by ISIS was not only to ‘establish a caliphate’ – it was also to prolong the slavery of women.

3. Previous Research

There is limited (albeit sufficient for the purposes of this thesis) research written about Kurdish women fighting ISIS. However, they have received considerable global attention in daily news websites, newspapers or magazines. The lack of scholarly research may reflect the acuteness of the situation – more time must pass before

sufficient research is done on the struggles of these Kurdish women. The news coverage was limited as well, although this is normal in journalism – normally, news stories are short and only the most sensational stories could pass the agenda setting of the medium. Kocer (as cited in Baybars-Hawks, 2016) argues that the representations of women fighters in Kobane (a Kurdish town in north-east Syria) embody broader dominant media frames constructing women based on difference – namely, as sexualized, exotic, oriental or ‘abnormal’ objects (p 164–165). Kocer further claims that despite rich and diverse cross-cultural ethnographic evidence of women’s participation in violent conflicts, women are still represented as victims in dominant media frames. Confining women to victimhood deprive them of their agency (as cited in Baybars-Hawks, 2016, p 166). Furthermore, Kocer underlines that looking at the images circulating through international news and social media, we often see beautiful women with long-braided, flower-adorned hair who, despite looking tired, carrying guns, looking fierce, and showing confident smiles, are shown in feminine settings such as cleaning armour (p 167).

One interesting point made by Kocer is that reporters are culture and image brokers, but they cannot be the sole brokers of representations of women. Women are diverse and multifaceted, which can make it difficult for journalists to separate gender stereotypes when they see women in armed conflicts (as cited in Baybars-Hawks 2016, p 167). In the context of this thesis, reporters are not considered the sole brokers of the

representation of Kurdish female fighters as reflected through images and photos – they are merely capturing a moment of what is happening on the war front against ISIS. Kocer remarks that the images of Kurdish female fighters being transformed via global media coverage are raising awareness of their struggles (as cited in Baybars-Hawks 2016, p 169-170).

Although women are generally linked to household work, with war being considered ‘men’s work’, there are examples throughout history of women taking up arms to defend their interests. To fully understand the media representation of women in combat, it is necessary to look to at their history.

Mojab (2000), in examining the history of Kurdish women, stressed that in the last two decades of the twentieth century, women joined the guerrillas fighting against Turkey and Iran, entered parliamentary politics, published academic journals, and created women’s organizations. However, she further remarked that the patriarchal nationalist movement continues to emphasize the struggle for self-rule at the expense of the struggle for equality. Mojab (2000), herself of Iranian origin, writes that nationalists depict women as the heroes and reproducers of the nation; protectors of the

‘motherland’; the ‘honour’ of the nation; and the guardians of Kurdish culture, heritage, and language. She argues that through these depictions of women and the relegation of equal rights to the future, the Kurdish case is by no means different from other

nationalist movements (Mojab, 2000).

Mojab (2000) underlines that the Kurds have been subjected to genocide, ethnic

cleansing, linguicide and ethnocide, with Kurdish women being especially vulnerable in ‘internal’ or ‘external’ conflicts during war. In another article, she argues that in

enduring war zones in the Middle East and North Africa, including Afghanistan, Israel-Palestine, Kurdistan (especially, Iraq, Turkey, Iran), Sudan, women are targets of violence. For example, in Afghanistan, the Taliban regime and its rival warlords engaged in selective violence against women (Mojab, 2003).

Branded as the inferior gender, women have been subdued physically, psychologically, morally and culturally. Mojab (2000) underlines, however, that images of Kurdish female fighters highlight a different representation – behind the laughing faces, these images communicate the idea of freedom for women, equality, and national pride, with the armour and weapons symbolizing a call to arms. These images can be a means for Kurdish female fighters, through their reflections in the lenses and/or the pencils of journalists, to identify themselves with a political or religious affiliation, such as the tricolour flag of Kurdistan or the symbols of the YPJ.

Toivanen and Baser (2016) also studied the media representations of female Kurdish fighters and their participation in the armed conflict against ISIS. They write what the Kurdish female commander, Nesrin Abdullah, said of the conflict in Rojava: Kurdish women are engaging in two struggles – a national struggle and a struggle for women’s rights (p 297). Furthermore, they stress that the representation of female fighters played a significant role in the war against ISIS, with these fighters being glorified for their efforts (Toivanen & Baser, 2016, p 297).

Begikhani, Hamelink, & Weiss (2018) outline the need for a new focus on the realities of women in different parts of Kurdistan in order to gain new insights into the

involvement of women in war, their victimization, their everyday life in conflict zones and post-war realities and their experiences of internal or transnational displacement. Begikhani et al. (2018), using a classical feminist approach, examined women’s bodies and sexualities as violable objects in war strategies and women’s active role and participation in war and militant organizations in defence of their communities, their nation and nationalist projects. The nation, Begikhani et al. (2018) stress, is rooted in traditional gender roles, assuming that men are active agents of war (soldiers, warriors and aggressors) while women are passive agents – victims, weepers, mothers and wives who are vulnerable to rape, aggression and slavery. They further note that national liberation appears traditionally to have been the main aim of Kurdish feminist groups. Kurdish women across all regions have begun to be more vocal in political activism as they become aware of the need for liberation from patriarchal structures (Begikhani et al., 2018). Begikhani et al. (2018) also draw attention to what women have achieved in the last 20–30 years. For instance, women have been able to participate more in political life through the introduction of co-chairs for mayors and self-governed areas such as Rojava. This in turn allowed women to gain confidence and a legacy to build on. Another Kurdish scholar, Caglayan (2007), analysed the roles of women in society and as political actors. According to her, Kurdish women’s basic lifestyle, experiences and social relational networks must be examined in order to understand why they have participated in the Kurdish movement and become political actors. She summarizes their gender role very basically as follows: women and girls are pressured in both society and their family, with girls being considered less important than boys. Boys were always sent to school, with girls being sent only when able (p 46). Caglayans

(2007) further explored the patriarchal nature of Kurdish society and the role of women therein. She notes that society consists of an Islamic lifestyle and secular male order, which define class power and is the product of national traditions (p 40). This is another reason that Kurdish female fighters have rejected a life under ISIS.

Pinar Tank (2017) points out that media framing paints the Kurdish female fighter as exceptional through a focus on her resistance to gender and state oppression, given that many Kurdish women struggle under the traditional patriarchal structures of Kurdish society. Many Kurdish women in Syria and Turkey have been subjected to honour killings, child or forced marriage, a culture of domestic violence and rape. Thus, female fighters are shown as not only combating ISIS, but also as trying to survive and change their society.

Pavicic-Ivelja (2017), in analysing the war against ISIS, argues that the science of women – called jineoloji in Kurdish and a major tenet of Öcalan’s theory of the liberation of Kurdish women – is key to their struggle against ISIS. Pavicic-Ivelja (2017) further writes that the revolution of Kurdish women against ISIS in Rojava is taking place not only through combat, but through dissemination of Öcalan’s ideology. In an article about the war in Syria and Rojava, Del Re (2015), underlines that the role of women is significant to accurate interpretation of the facts, but remains a

controversial issue. Furthermore, Del Re (2015) notes that while the war in Syria ongoing since 2011 has received too little global attention overall, news coverage of Kurdish female fighters has helped to bring some attention to the conflict. Del Re (2015) mentions that ‘attractive Kurdish female soldiers in uniform’ is a subjective concept – beauty is very subjective and its norms differ across cultures (p 84-85). Kurdish women themselves had ‘a third independent strategy’ (i.e. a strategy not sided with the Basar regime or the US and Russia) to defend their homeland and create an equal society, based on bottom-up democracy and the representation of a feminist struggle against ISIS in Rojava alongside Western state powers. Thus, Simsek and Jongerden (2018) argue (citing Debrix, 2007), Kurdish women function as instruments, with fighting women being represented as the boots on the ground of a Western

intervention. According to Simsek and Jongerden, again citing Debrix (2007), the representation of Kurdish women by Western media was a form of ‘tabloid geopolitics.’

Tabloid geopolitics is a popular geopolitical narrative that is easy to understand because it uses little text and numerous pictures.

The US intervention in Iraq and its presence throughout the Middle East hinged on a myth – the evidence for starting the intervention never existed, as was later admitted by the US. Therefore, the US found it difficult to clarify why they were in the area at all – as a force to bring democracy or as an occupying nation. Scholars like Simsek and Jongerden (2018) note that the portrayal of Kurdish women fighters by media channels allowed for attention to be drawn away from the impotence and failure of the American military intervention.

This thesis is an attempt to add to the limited academic research on how Kurdish female fighters are represented in the media. As can be seen from the above research, there is comparatively little research on the historical, political, and social aspects of this area of study.

What makes this study unique compared to previous studies is that it points to the similarities between the role of media representations and the role of Kurdish female fighters in propagating moral messages as well as their ability to act as mirrors of Kurdish society. Of course, thousands of years ago, evolution and revolution took place everywhere in the world – some regions were quick to develop in terms of their

principles and traditions, whereas others needed a longer time. Kurdish society, when compared to other societies in the Middle East, is unique in its aim to achieve equality for women and its pursuit of democracy.

Reports and photos emerging from the war on ISIS do not lend further credibility to the notion that photography as a medium allows a kind of unfiltered expression of meaning – in fact, every pair of eyes that alights on a photo adds new meaning to it. While photos can arguably communicate an opinion more emphatically of written texts, they remain subject to the biases of the viewer and, indeed, the photographer.

The media representation of Kurdish female fighters changed the course of war.

Beforehand, ISIS had gained considerable success, having taken over an area as large as France within several weeks of commencing their attacks, allowing it to gain further support from the traditional segments of Iraqi society. At this point, the role of news

media in the conflict zone was no longer just the ‘reporting source’; it had to choose a side or not. Accordingly, media coverage in the conflict zone was able to serve as a vital means of communication to support Kurdish female fighters in changing the rules of the war front. The photos – women preparing for combat – helped to communicate their ideals in opposition to patriarchal norms and the will of regional colonizers to continue with the enslavement of Kurdish women.

However, the ideology of Kurdish women – that is, Ocalan’s theory of a ‘free society’ – is a hidden facet of these photos not clearly visible in the lenses of reporters. Rather, the categorization and interpretation of these photos has been more focused on traditional gender roles and their status as heroes. The focus on Kurdish women’s ideology is exactly how this thesis differs from previous studies. More specifically, the Kurdish ideology – ‘women, liberty and life’ – is a core feature of my framing analysis of their representation in international news outlets and photos (see section 4).

4. Theoretical Framework

To answer my research questions, I conducted textual and visual analyses. The purpose of the textual analysis was to derive meaning from the data set, while the visual analysis was used to strengthen the results of the textual analysis.

4.1. Theory of Representation

I chose a research problem closely connected to theories in media and communication studies, particularly the concept of representation. According to Stuart Hall,

‘Representation means using language to say something meaningful about, or to represent, the world meaningfully, to other people’ (1997, p 15).

The theory of representation has many aspects, but it generally deals with how language, signs, images and culture are interwoven, with one being less without the others. There are three different approaches to theorizing representation: reflective, intentional, and constructionist. The reflective approach holds that language reflects a meaning which already exists; the intentional approach outlines that language expresses

only what the speaker or writer wants to say; and the constructionist approach suggests that meaning is constructed in or through language (Hall, 1997, p 1-2).

Hall also outlines the concept of mental representation, which holds that meaning depends on the relations between things in the world – people, objects, and events, real or fictional.

In sum, there are two related systems of representation: The first helps us give meaning to the world by constructing a set of correspondences between people, objects, events, and abstract ideas. The second involves constructing correspondences between our conceptual map and a set of signs, arranged, or organized into various languages which stand for or represent those concepts. In other words, the meaning of the link between things, concepts, and signs is the core of the production of meaning in language. What links these three elements is, according to Hall (1997, p 5), representation.

Dyer (2006) studied the representation of social groups and noted that

the complexity and variety of a group is often reduced to a few characteristics. Then an exaggerated version of these characteristics is applied to everyone in the group as if they are an essential element of all members of the social group in question. These

characteristics are then represented in the media through media language (p 353–360). Dyer (2006) further argues that stereotypes are always about power and that some are more recognizable than others – for example, stereotypes about women are more recognizable, while stereotypes of white or middle-class men are difficult to recognize, since they are hidden very well in the language.

Regarding signs, language theorist Barthes (1988), has an interesting point: ‘a garment, an automobile, a dish of cooked food, a gesture, a film, a piece of music, an advertising image, a piece of furniture, a newspaper headline – these indeed appear to be

heterogeneous objects.’ What might they have in common, he argues, ‘that this at least all are signs, this car tells me the social status of its owner, this garment tells me quite precisely the degree of its wearer’s conformism of eccentricity’ (Barthes, 1988, p 147). Although this is dated and semiotics has developed since Barthes, his theory is still important to consider – especially when evaluating images.

4.2 Gender Theory

One is not born a woman, but rather becomes a woman. No biological, psychological, or economic fate determines the figure that the human female presents in society; it is civilization as a whole that produces this creature, intermediate between male and eunuch, which is described as feminine’ – Simone de Beauvoir (1949 p 8)

The above quotation from Simone de Beauvoir is worthy of applause because of how well it summarizes how gender is produced. Feminism is an emancipatory,

transformational movement aimed at undoing domination and oppression, as

emphasized by Steiner (2014). However, as Steiner (2014) argues, this is a complex and much contested concept. She underlines that feminist media theory applies

‘philosophies, concepts, and logics articulating feminist principles and concepts to media processes such as hiring, production, and distribution; to patterns of

representation in news and entertainment across platforms; and to reception’ (p 359). Therefore, feminist theory does not hide in politics, but is on the contrary explicitly political and addresses power. In comparison with other media theories, feminist media theory takes gender seriously.

In her book, Steiner (2014) writes that gender intersects with other dimensions of identity such as race, class, ability, nationality and sexual orientation, and the inherent power relations within these categories (p 359). The media debate surrounding the digital movement #MeToo was a recent major challenge to patriarchal norms and values. It is an example of the use of digital media in feminist political struggle.

An imperial and colonist approach remains in place in Turkey, Iran, and Syria against Kurds. Their language is banned from all official institutions and they are only

‘allowed’ to speak their language at home, which leaves Kurds in general and

particularly women out of the political, cultural, and educational systems. They either have to learn a foreign language in order to get an education or live outside the system in poverty.

hooks (1999) recalls that in America, the social status of black and white women has never been the same. This parallels the situation of Kurdish women in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. If Black and White feminists are going to speak of female accountability, hooks (1999) says, then the word racism ‘shall be seized, grasped in the bare hands, ripped out of the sterile or defensive consciousness in which it so often grows, and transplanted so that it can yield new insights for our lives and our movements’ (p 18).

Although women are prominent in media content, their role is often secondary to that of men. Women are also significantly under-represented in different types of media, such as video games; women are also under-represented within key decision-making roles in media institutions (Hodkinson, 2017, p 244–245).

Hodkinson is not offering a general evaluation of female representation across the world. Instead, he is emphasizing the representation of Western women. Being financial and sexually free is an important step towards equality and a free society. But it is no secret that women earn much less than men do, even for the same position. Thus, more has to be done in the West as well. But how about women in Eastern societies,

especially women in the Middle East?

4.2.1. Gender roles in Western media

In her book Gender and the Media, Gill (2007) writes that feminist studies are

heterogeneous – while many researchers agree on the influence of the cultural part, they disagree on the theoretical approaches and methods. Specifically, they have different epistemological experiences, different views on power relations, different views on how to look at the relationship between representations of reality and the media's reference to the individual and subjective understanding (Gill, 2007, p 8).

In Gender and the Media, Gill (2007) examines how gender roles are portrayed in Western media, particularly how the media construct masculinity and femininity and the relationship between them. She argues that women are portrayed as objects and are often sexualized when viewed from a male perspective. She also notes that media usually depict the Western white woman and that she can represent "women" while men are assigned the task of representing the world (Gill, 2007).

Gill also discuss the concept of "women's culture", which includes genres such as soap operas, women's literature and romantic comedies. Such genres have been assigned a lower status in society than other types of culture. This is problematic because it reduces all women's cultural interests to a genre considered inferior to those better represented by the male sex (Gill, 2007, p 18). This leads to the emergence of stereotypical women's interests and does not account for how women are all different, which of course is also expressed in their cultural interests.

Gill (2007) also discusses that women tend to play a more self-sacrificing role than men. Gill notes that the stereotyping of women helps to maintain hegemony concerning the power of men over women. Gill, like Hall, defines stereotyping to maintain unequal power relations.

4.2.2. The Search for ‘Real Women’

In Cultural Representation and Signified Practices, Gledhill (1997) looks at how women are portrayed in soap operas. She notes that women are represented by stereotypes rather than as ‘real women’, which we need to change. Gledhill asks whether reducing stereotyped portrayals of women, the image of women can be redefined. Gledhill rightly notes that women are not a homogeneous group in which everyone can recognize themselves; they are a heterogeneous group that differs in age, sexual orientation, class, ethnicity, etc. She emphasizes that it is not a question of reducing the image of the female sex as perceived in the media, but that the problem is rather to create a new stereotype of the ‘real woman’. But who really has the power to do this? (Gledhill 1997, p 346). Using representations of women to increase sales and improve marketing strategies is widely applied in other media as well, suggesting that the same lenses can be applied to examination of ‘brave Kurdish girls from the Middle East’ in news media as well. The theory from Gledhill could be interpreted as dated source, and lot of things have changed from news-reporting and entertainment-mediums but the political situation in Middle East is much the same, therefore this information is relevant to this thesis.

In Western media coverage, the female sex is depicted as ‘the white woman’ while men are assigned to represent the world. This shows a polarized reality. In some ways the polarization could be translated to ‘bad’ versus ‘good’, which can also be applied to understanding the global attention to Kurdish female fighters, with them being presented as being ‘good’ in juxtaposition to the bearded men in black as ‘bad.’ This polarization is correct but it is still a polarization.

In terms of stereotypes, Kurdish female fighters, in their movement towards the liberation of women, have rejected traditional stereotypes and have taken ‘the power’ from men to create their own ‘land’ and territory. This shows that eliminating

stereotypes in the Middle East is possible. Girls who were once ‘not equal’ to boys were ‘suddenly’ good enough to fight on the forefront against terrorists and to write in favour of change. From this perspective, they are searching for the ‘real woman and an equal life.’

If stereotypes, according to Hall, are meant to maintain unequal power relations, Kurdish female fighters have certainly begun challenging their stereotypes. Still, the way they were depicted in the media indicate that stereotypes are not easy to change. Indeed, Kurdish female fighters are represented in US and UK media through the construction of sexualized and heroic figures. No new stereotype is being created – they are being represented using the classical lens.

The question of who will be able to change the power relations in the Middle East remains unclear, but Kurdish female fighters are certainly making a powerful attempt in their fight against ISIS.

4.3. Kurdish theory and the concept of women’s liberty

To understand Kurdish women fighting against ISIS in Rojava, it is pivotal to understand their motivation, particularly the ideology of Abdullah Öcalan, the jailed PKK leader and the creator of the term jineoloji – the concept of women’s liberty through creating an equal society. Understanding and analysing the circumstances underlying the revolution of Kurdish women is fundamental, since a lack of

consideration of such socio-political factors would preclude an understanding of why Kurdish female fighters gained global awareness.

Kurdish women are the backbone of the Kurdish people. The Kurdish nation, which has experienced so much hardship, would not have been able to stand on its feet had it not been for Kurdish women. Without Kurdish women, perhaps there might not even be a Kurdish nation today. This is not even a matter of reproduction. Besides the women in Rojava fighting ISIS, Kurdish women in Turkey, Iran and Iraq have been very keen to enact the ecological paradigm of Öcalan’s ideology. Colonialism at the state level and backward feudal family structures paralyzed women.

Öcalan’s writing shed light on this issue and the solution he proposed was considered crucial for the advancement of women. The majority of Kurdish men are also convinced that the solution is ‘free Kurdistan and free women as a combined process.’ According to Öcalan, this is wrong – both struggles go hand in hand. Freedom and equality for women must not be postponed. This is exactly what happened in Rojava, where the fight against the ISIS also became the struggle for ‘liberation of women.’

The historical aspects and structures of the family in Kurdistan and the Middle East cannot be neglected. Thus, they need to be thoroughly evaluated. Since the end of 1970s, the PKK – with Öcalan as leader – has recruited women and has given considerable attention to the internal social problems that the Kurdish people were facing.

Öcalan was later captured in a secret operation involving numerous countries and handed over to the Turkish authorities in 1999. From prison, he has developed a democratic solution for the Kurdish question in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria with a focus on the role of a free life for women.

Öcalan, who started the war against Turkey, denounced violence and preached for autonomy and equal rights of women, men, minorities, and all segments in society through a bottom-up democracy which he argued would be superior to the

Euro-American one. In brief, the Kurdish leader designed the Rojava model as a new form of self-government. The model consists of a central government and local communities that enjoy considerable political autonomy.

In the Middle East, the family structure is important. The dynastic system, Öcalan (2013) argues, should be understood as an integrated whole, where ideology and structure cannot be separated. This system developed from the tribal system but later established itself as the upper-class administrative family nucleus, thereby challenging the tribal system. It has a strict hierarchy, acting a proto-ruling class, a prototype of a state that depends on men and male children (Öcalan, 2013, p 36).

According to Öcalan (2013), in the Middle Eastern civilization it has become so deep-rooted that there is almost no power or state that is not a dynasty and every man in the family perceives himself to be the owner of a small kingdom. This dynastic ideology is effectively why family is such an important issue (Öcalan, 2013, p 37).

Öcalan stresses that the male monopoly that has been maintained over the lives and worlds of woman throughout history is not unlike the monopoly chain that capital maintains over society. He argues that dominance over woman is the oldest colonial phenomenon, with the family becoming ‘the man’s small state’ (Öcalan, 2013, p 37-38). The family as an institution has been continuously perfected throughout history, solely because of the reinforcement it provides to the power and state apparatus. First, the family becomes a stem cell of state society by giving power to the family in the person of the male. Second, women’s unlimited and unpaid labour is secured. Third, she raises children in order to meet the needs of the population. Fourth, as a role model, she fights against slavery and is a role model to the rest of society. Family, thus constituted, is an institution where successional ideology becomes functional (Öcalan, 2013, p 38). According to Öcalan’s concept of women’s liberty, the most important problem for freedom in a social context is classical marriage and family. When the woman marries, she is in fact enslaved and this is not a general reference to sharing life or partner relationships that can be meaningful depending on one’s perception of freedom and equality. The absolute ownership of the woman means her withdrawal from all political, intellectual, social, and economic areas (Öcalan, 2013, p 38–39).

The dynastic family culture that remains so powerful in Middle Eastern society today is one of the main sources of its problems, having given rise to an excessive population with the power and ambitions to share in the state’s power (Öcalan, 2013, p 38–39).

In Kurdistan, Öcalan (2013) argues, family is considered sacred, but it has been crushed because of a lack of freedom, economic problems, a lack of education, and health problems and so-called ‘honour killings’, which are a symbolic revenge for what has happened to society in general. In other words, women are made to pay for the obliteration of society’s honour (Öcalan, 2013, p 42).

The Kurdish male has lost both his moral and political strength, except for where it concerns women’s honour; thus, he has no other area left to prove his power or powerlessness. The loss of masculinity is taken out on women (Öcalan, 2013, p 42). One should not discount family, Öcalan argues. If soundly analysed, family can become the mainstay of democratic society. Indeed, not only the woman but the whole family should be analysed as the stem cell of power; if not, we will leave the ideal and the implementation of democratic civilization without its most important element. Family should be transformed, and the claim of ownership over women and children, handed down through the hierarchy, should be abandoned (Öcalan, 2013, p 39-40).

In opposition to the traditional and conventional family structure, Öcalan proposes, capital in all its forms and power relations should have no part in the relationship of couples, the breeding of children as motivation for sustaining this institution should be abolished and the ideal approach to male–female relationships is one that is based on the philosophy of freedom and devotion to moral and political society. Within this

framework, the transformed family will be the most robust assurance of democratic civilization and one of the fundamental relationships within that order (Öcalan, 2013, p 40).

This thesis is about how Kurdish female fighters fighting ISIS are represented in Western media coverage – in other words, how they are represented without a Kurdish lens. Thus, bringing in Öcalan’s theory provides another perspective, clarifying how family structures and historical aspects fit into the emancipation of Kurdish women, their role in their society and their struggles on the frontline. This study of Western media coverage would be lacking without bringing in Öcalan’s concepts. Without the architecture of jineoloji (directly translated as the science of women), understanding the ‘angels of Rojava’ would be limited.

Some researchers have reflected on Öcalan’s ideology of women’s emancipation. Novellis (2018), for instance, performed a comparison study of women in nationalist guerrilla movements such as those in Sri Lanka and Angola. She found that women's militancy in these countries did not achieve changes in traditional patriarchal structures. By contrast, the militancy of Kurdish women, according to Novellis (2018), led to substantial equality in the PKK, particularly because the party’s ideology actively promotes a subversion of traditional gender structures. While Novellis (2018) stresses that even though patriarchal structures remain unchanged and female militants were handed from a patriarchal family to a patriarchal party, the Kurdish women movement within the PKK has gained a kind of autonomy and have an active influence on the PKK’s ideology and practice.

4.4. Methodology

Visual and qualitative content analyses were carried out. All photographs connected to the selected news articles were analysed. The purpose behind the visual data collection was clear, as the photos served to complement the text and can confirm or challenge the content of the written text. What is not found in the text may be hidden in the photo. Before going into the methods in depth, I should reiterate the research questions:

- How are Kurdish female fighters struggling against ISIS represented in US and UK media coverage? – a textual analysis

- Which of the multiple interpretations of Kurdish female fighters are conveyed? – an image analysis

The research questions were slightly finetuned after the investigation started. As Layder (2013) explains, research questions emerge cumulatively from the research and

therefore the more flexible the sampling process is, the more thorough an investigation will likely be.

In order to answer my research questions, I needed a framework to address the research problem. Research methods should be chosen because they are the most appropriate for the problem that is being investigated (Layder, 2013, p 7). In this section, I

contextualize my research methods. To interpret and categorize empirical data in a research project, having a theory as an analytical framework is essential. Collins (2010)

also notes that a central function of a framework is to give a comprehensive overview of the findings and contextualize them (p 36).

What is qualitative analysis? Denzin and Lincoln (1994) state that qualitative research is a type of scientific research:

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative

researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of or interpret phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical

materials case study, personal experience, introspective, life story interviews, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts that describe routine and problematic moments and meaning in individuals’ lives (p 192).

Several scholars and theorists have also considered the overall purposes of qualitative research. In this regard, Patton (1985) summarizes:

Qualitative research is an effort to understand situations in their uniqueness as part of a particular context and the interactions there. This understanding is an end in itself, so that it is not attempting to predict what may happen in the future necessarily, but to understand the nature of that setting – what it means for participants to be in that setting, what their lives are like, what’s going on for them, what their meanings are, what the world looks like in that particular setting – and in the analysis to be able to communicate that faithfully to others who are interested in that setting…The analysis strives for depth of

understanding (p 1).

The above quote is pivotal to my thesis – It describes how I dealt with the data set. Giving meaning to the situations in images and text is essentially an attempt to try on the shoes of the subjects: How is it for them? What would I say or do if I were in their clothes?

According to Merriam and Tisdell (2015), the researcher is the primary instrument of data collection and analysis in qualitative research. Since understanding is the goal of

this research, the human instrument, which is able to be immediately responsive and adaptive, is the ideal means of collecting and analysing data (p 16).

According to Berg (2009, p 338), ‘a content analysis is a careful, detailed, systematic examination and interpretation of a particular body of material to identify patterns, themes, biases and meanings. Other theorists, like Wildemuth (2009), have clarified the distinction between content analysis and qualitative content analysis. She underlines that ‘qualitative content analysis goes beyond merely counting words or extracting objective content from text to examine meanings, themes and patterns that may be manifest or latent in a particular text’ (p 309).

According to Hsieh and Shannon (2005), there are three clear categories for the

application of content analysis: conventional content analysis, directed content analysis and summative content analysis (p 1277). Conventional content analysis is ‘a way to describe a phenomenon when existing information or theory on its occurrence is

limited’ (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005, p 1279). This method has researchers examine a text, from which they construct categories (as opposed to using pre-determined categories). Direct content analysis is somewhat less flexible in terms of its ability to identify key themes and categories – this approach assumes that existing theory is helpful and can be used to explain a phenomenon, but still it is incomplete. In general, researchers use this approach to validate or extend current theory. Summative content analysis, according to Hsieh and Shannon (2005), involves identifying and quantifying content or words in the text to better understand their context and use within the text (p 1283).

For this thesis, the conventional content analysis of Hsieh and Shannon (2005) served as the basis. This thesis required consideration of different themes such as personal

motivation, women’s liberation and beauty. These themes emerged – linked to the concept of Barthes’ ‘writerly text’ – in relation to how women are formulated in general in the media; therefore, I used these themes to interpret the articles found on the

websites of The Guardian and CNN International.

I used two different news mediums: newspapers and television. I used both because while searching for US papers, some of them were behind paywalls. The material is very restricted and due to time and financial restrictions in gaining more material, I had to take what was available. It is also very important to underline that they are different

medium, but due to their position - one could expect already the content from the outset. The fact that this is a research paper there should be a room for error and trials.

Therefore, the choose was not changed. Moreover, it was easy to gain access to the CNN archive and due to time restrictions, it was easiest to choose this news source as representative of US news. CNN occupies a centre-left position on the political

spectrum, the same as The Guardian. I chose these news outlets for this thesis because it aligned with my research questions and overall aim of examining the media

representation of Kurdish female fighters. Nevertheless, while reflecting on the results, I realized how many narratives were written about western women fighting against ISIS in Rojava. Accordingly, one might conclude that CNN and The Guardian were ‘cherry-picking’ stories for their audience in order to create a point of ‘contact’ with that audience. It is of course much easier for their audiences to comprehend these stories when it is ‘one of them’ fighting against ISIS. In this way, audiences could claim the struggle of the YPJ as their own. The worldwide admiration for the YPJ, as reflected in media coverage, might also explain why so many Western European women decided to fight together with the Kurds.

This thesis utilized an interpretivist/constructivist paradigm. This paradigm or ‘lens through which we view the world’ is largely the product of an accumulation of beliefs, ideas and assumptions which influence how we as individuals make sense of things (Collins, 2010, p 38). This lens was applied to the visual analysis. Gillian Rose (2001) says that the famous phrase from John Berger – ‘ways of seeing’ – refers to how ‘we never look at one thing, and we are in fact identifying relations between ourselves and that at which we look.’ According to Rose, the study of visual matters has somewhat veered away from auteur theory (i.e. the notion that a text’s author’s intended meaning is the most relevant for visual analysis). Nowadays, Rose means that there is more a trend towards understanding how audiences construct meaning, and how an image is made and seen in relation to other images.

4.5. Research Design

The research design comprised the two types of analysis I previously outlined: qualitative content analysis and visual analysis of images in news articles.

The data for this study consisted of 19 online news articles on female Kurdish fighters in Northern Syria and Rojava from selected national presses in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) – specifically, the websites of The Guardian and CNN International. The selective articles were categorized considering the frames of

‘personal motivation’, ‘liberation of women’ and ‘beauty of women’. The material was, admittedly, highly selective – only 19 articles were found using ‘YPJ’ as a keyword, despite the aim of finding at least 20 articles.

I categorized the data as such because, journalists tend to write news articles using these frames to make their news more appealing. In the context of Kurdish female fighters, 1) personal motivation is primarily about emotions, with their attendance in the war being about how they feel after the loss of a member of family; 2) the liberation of women frames the participation of female fighters as ideological, and 3) beauty of women frames in reference to their women’s physical features.

To collect the data, I searched words such as ‘YPJ’ (Women’s Protection Units, Syria-Rojava) on the internet. Articles published between 2014 and 2019 were obtained in The Guardian and CNN International. I chose publications from both the UK and USA because they covered Kurdish female fighters. Both countries were also involved in supplying military aid to Kurdish forces inside Syria and Iraq.

For the qualitative content analysis, I chose 19 articles from both news outlets and categorized them using the three previous categories (at the beginning there were 20 articles, but after the deep analysis, I found out one article was duplicate, after more search no article according to the specific criteria was not found). Specifically, after data collection, the data set was read through and each article was categorized as in the Excel spreadsheet (see Appendix 1). The same questions were used for every article so that every article was treated the same (see sections 4.5.1 and 4.5.2).

To better understand the context of the text, it is necessary to use a broader perspective including where it was situated and who created it. This offered a reference to what social and political events may have influenced the text at the time. Consideration of location, the production, and historical aspects of the image, and who the journalist is and her/his gender will help to create a greater understanding of the text and the image itself, according to Rose (2001).

For the visual analysis, I referred to Rose’s (2001) book Visual Methodologies – An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. As with text, the location and the creator of the photo is important, as are the social and political events at the time the photos were created. Indeed, when evaluating photos, Rose (2001) mentions that it is important to know all aspects of the image, including its production (p 29).

Regarding the process of how to analyse photos, one of the main elements concerns reflection on the potential meanings within the piece. During this stage, it is important to understand the significance of certain images within the piece, as well as how different cultures may read these images or photos.

According to Barthes (1988), there are two texts: the readerly text, the meaning of which is unambiguous and there is no need for interpretation, and the writerly text, which makes room for multiple meanings. In this thesis, during the evaluation of the data, I focused on the writerly text. If we consider the photos as merely belonging to the articles about Kurdish female fighters, we would understand them as part of a readerly text – thus, the formal elements can be easily recognized and not much argumentation is required. However, if we consider the articles as writerly texts, then the door to many interpretations is open, which in turn means the reader can use her/his sensemaking system to interpret and give comments.

Directly after gathering the sample data, initial readings were conducted of each article in order to identify areas for analysis. Through the complementary process of these two analyses, I could fully engage my sensemaking system to interpret the articles.

4.5.1. Visual analysis

The first step consists of a descriptive, formal analysis of the image. This was done to ensure that all applicable elements were considered and incorporated. The emphasis throughout this stage of the analysis is not to apply any level of interpretation beyond the most basic processing of immediate comprehension and requires articulation of everything which is visible to the naked eye. This first stage could perhaps be considered as a content analysis of sorts, as there is at least some potential for replication of results between researchers due to the lack of interpretation required. The following questions were used in my analysis of every article:

1 - Where is it? Who took the picture? 2 - What is seen in the photo?

3 - What kind of emotional and human message(s) does the photo convey to me?

4 - Into which of the three themes can you categorize the photo? (1) personal motivation is primarily about emotions, with their attendance in the war being about how they feel after the loss of a member of family; 2) the liberation of women frames the participation of female fighters as ideological, and 3) beauty of women frames in reference to their women’s physical features)

4.5.2. Content analysis

For the content analysis, the context of the text was considered and a broader look at the piece, including where it was situated and who created it, was used to provide a frame of reference as to how social and political events at the time may have influenced the text. I used the following questions to guide my analysis:

1 - Who wrote this article? (note that this question was not relevant the analysis; it was simply used for organization of the data set)

2 - What kind of message(s) is conveyed in the article?

3 - In which of the three themes can you categorize the article?

Following this, a comparative analysis was conducted to assess whether certain frames were dominant over others in both data sets.

The dataset and the individual analysis together with the specific links can be found in Appendix 1.

4.6. Ethical Issues

According to Polonsky and Waller (2004), when the researcher is dealing with data, there are ethical considerations regarding consent, privacy, and authorship (p. 149). For the content of the articles that I accessed for the data collection, there was no need to request permission to use because they were all available to the public. I referenced authors and never touched the content of the articles in the data collection for this study either.

Another ethical consideration concerned the photos. However, since all the articles were open to the public, I did not need to exclude or blur them or request consent from the persons in the photos.

Finally, according to Polonsky and Waller (2004), one thing all researchers need to consider, regardless of the methods used, is how the results are communicated and presented. I made sure to avoid plagiarism and misrepresentation of results. 4.7. Role of the researcher

It is likely that my own biases affected my point of view as a researcher. Since I am of Kurdish origin, this could have affected selection and interpretation of the data. I searched for accessible articles about the Kurds to ensure that data collection and analysis could be replicated by another researcher.

My generation, commonly called the Millennials, grew up with Kurdish women defending themselves and their homes. They struggled against the Kurdish feudal dogmas and the states using strategies such as genocide, feminicide, assimilation to marginalize Kurdish endeavours to obtain nationality. Much of the research conducted until now has been valuable and informative; however, it has lacked a historical

perspective on the Kurdish question. This is likely because there is limited information on the Kurds, since many states – especially Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria – destroyed books and literature about the Kurds. Turkey is particularly well-known for this type of policy: ‘There are no Kurds, there are only Kar-Kurt’ (which sounds like the Turkish word for Kurd but means the sound of walking on snow).

I had the same difficulties in obtaining previous literature on Kurds, especially Kurdish women. Thankfully, due to technical advancements, information on groups are not easily erased. Therefore, I tried to insert a historical perspective into my analysis as well. The Kurdish women (or ‘angels’) fighting against ISIS depicted by Western media have a history; they did not fall from heaven or emerge from a deep jungle. They were there before ISIS and they remain there after succeeding in defeating many of the ISIS forces. One should not forget that Kurdish women have had a quiet voice – one could even call it ‘a voice from the grave’. Their political and military presence have given

them greater attention. Their ideology can be summed as ‘jin’, ‘jiyan’, ‘azadî,’ (women, life, freedom), which can often be heard at many demonstrations.

It is very difficult to understand ‘the other’ within an already highly heterogenous region like the Middle East, where the culture and language can differ even from village to village. The stories of the Kurdish women struggling against ISIS gained

international attention and put a face on the revolution in Rojava. To understand this phenomenon better it is necessary to use all our senses – particularly our eyes, even if they cannot tell a whole story alone. The pictures and news coverage portrayed women in a very positive light, allowing us meaning and hope. The Kurdish female fighters defended humanity against ISIS; therefore they received attention, not because they were beautiful or brave.

As matter of fact, the criteria for beauty are considerably different between the West and Middle East. In the West, having a ‘bikini-style’ body is beautiful, while in the Middle East it is considered more beautiful to be overweight. This is crucial to for my analysis, as it helped me to analyse the images without adherence to either set of criteria. It is pivotal here to underline that the images were described through what can be seen with the naked eye.

4.8. Reflections on learning

I think that the main strength of content analysis lies in its ability to use a wide range of articles. However, to ensure a more representative sample, it would have been better to use a larger selection of articles from different newspapers across different countries. The sample size in this study was limited due to time restrictions.

In my case, the research method was not so well designed and everything was done somewhat rashly. Therefore, collecting data could have been more time-consuming than what was done for this study. I think this is the biggest learning outcome from my application of this method.

Furthermore, due to lack of time, my whole methodological process was too narrow. Further research questions could have strengthened the study.

The content analysis of the articles gave insight into the themes and frames of these articles.

To understand these articles in terms of Hall’s (2001) theory of representation, it is important to underline that humans possess a complex approach to meaning making, which could be a system. This system develops over our lives with our experience grows, enabling us to recognize different indicators as having different conceptual meanings. We then categorize these concepts in relation to how similar or different they are to other concepts. Thanks to this mechanism, we can give meaning to the world around us.

In the context of this thesis, one might say that reporters and image brokers are not solely responsible for turning their cameras on beautiful and feminine women even on the battlefield. For example, in one Guardian article (Townsend & Ochagavia, 2017), young women from the UK are being presented as humanity, with ISIS being positioned as the enemy of humanity: ‘Kimberly Taylor from Blackburn is part of the all-female Kurdish force battling to rout Islamic State’. This news content clearly conforms to theme 2 (liberation of women). This frames the participation of female fighters as ideological. Although there is some description of the women, there is no direct sexual objectification. Rather, greater information is given: ‘She has no body amour or helmet, and is wrapped with an emerald and orange embroidered keffiyeh around her forehead to help her express her femininity.’

The journalist’s writing shows how the ideology of Öcalan (2013) is being reflected through the role of women on the warfront against ISIS: ‘first shall the DAESH be crushed and then the women shall be liberated’ (The Guardian, 2017).

Analysing the photos in terms of Hall’s (2001) theory underlines how people may need these visualizations in order to make sense of the war against ISIS. On the other side, the struggle of the Kurdish female fighters has created a positive perception of the Rojava revolution. Diplomats are investing countless hours in creating such a positive view of their culture, language, and country. In this way, Kurdish female fighters have invested their lives towards boosting interest and increasing awareness of their struggle globally.

Even though the femininity of Kurdish female fighters could be depoliticizing and devalue their ideological goals through specific Western marketing strategies designed to increase sales, they will remain in the history books and people can visualize them with their true personal or ideological motivations.

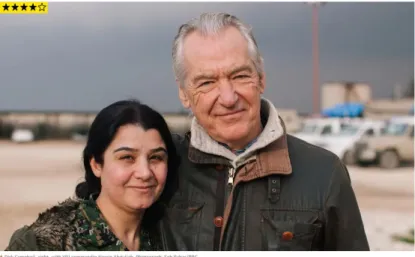

Figure 2: Kurdish female fighter, The Guardian, Photograph: Mark Townsend/The Observer

The young girl in Figure 2 is smiling towards the camera. The green scarf around her young face gives her ‘neutral’, non-militarized look. Green is commonly associated with springtime, freshness, and harmony. In a way, the colour gives harmony to her face. Moreover, her uniform is touched with the feminine through visibility of the light blue t-shirt.

To Barthes (1968), a ‘text’ is everything that is read or seen. On the other hand, Hall requires that a shared language system is an important element for interpreting meaning. Moreover, Barthes underlines the collective presence of signs, which signify meaning and relate to each other in order to create meaning from context. According to Collins, the reader must describe what he/she sees. The fact that the cultural contexts differ in the audiences of the material for this thesis.

When the above ideas are applied to the photos in the collected articles, the first thing that catches the eyes are the serious, determined but happy faces of the female fighters. Their clothes and uniforms are signs, their scarfs adding femininity to their military clothes. The way they hold the weapons is another sign. Even though we have not seen these women in real life, we still can imagine them thanks to the photos and videos, which gives them meaning and categorization in our mind. This is image is semi-closup which gives the audience for The Guardian a glint of the setting from a war front in Rojava.

Figure 2: Kimberly Taylor from UK, under the flag of the YPJ, The Guardian Photograph: Mark Townsend/The Observer

When applied this to the photos in the articles, readers’ interpretation is guided through a conceptual map connecting with other elements within the image to allow for a greater understanding of what it could be, after which the language can be analysed to give an overall picture. One must consider the difficulties of reporting from a battlefield – at the frontline, it is extremely difficult to observe the situation. As such, it may be easier for the reporter to go behind the lines to see how Kurdish female fighters are preparing for the war, such as doing their hair or taking care of their hygiene, which all humans do, in a non-sexualized way.

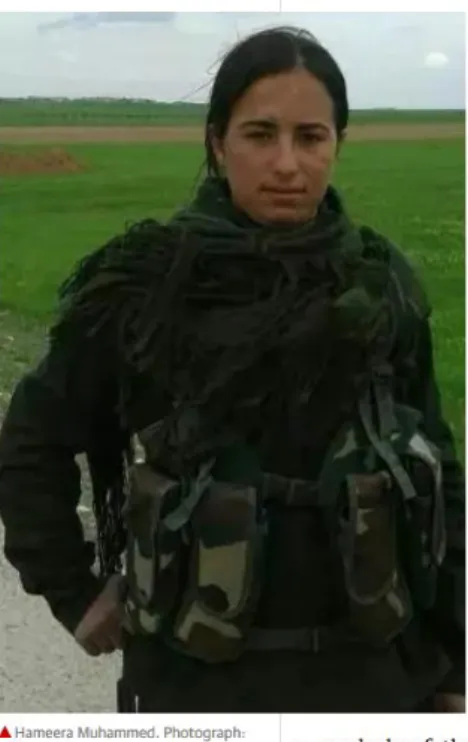

Figure 3: Kurdish female fighter, The Guardian Photograph: Mark Townsend/The Observer

Connecting Hall’s theory of representation to text from The Guardian, the war is being evaluated from the perspective of a young British women, describing herself as a

Marxist, fighting ISIS under the umbrella of Kurdish SDF forces. She uses her language to say something meaningful about or to represent her experiences to other people, in this case the readers of The Guardian (Blake, 2018):

“I have never seen anything like it in all my life,” she said from her military base in the Kurdish city of Qamishli, where her unit has repaired since escaping the city. “It was chaos. The bombing was really heavy, especially just before the city fell. They hit the hospital, people were fleeing. I was helping out at the hospital and bodies were just coming in day after day. Seeing women screaming, fainting. Mothers who have lost their sons, daughters who have lost their

fathers. These were civilians, not soldiers. It was heartbreaking.

Both the above quote, and the following, make it clear that the young woman is espousing the ideology of Öcalan without naming it directly, describing the system in Rojava as a direct democracy. The quote underlines ‘she is western’ but she wants to help her sisters in Rojava:

“They have built a system of direct democracy and gender equality in the heart of the Middle East,” she says. “The region has suffered war and oppression for