MARIE APPELGREN

CARING FOR PEOPLE WITH

INTELLECTUAL AND

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

How can it be experienced and perceived by

registered nurses?

LICENTIA TE THESIS, F A CUL T Y OF HEAL TH AND SOCIET Y 202 1 .1 MARIE APPEL GREN MALMÖ UNIVERSIT Y C ARIN G FOR PEOPLE WITH INTELLECTU AL AND DEVEL OPMENT AL DIS ABILITIES L I C E N T I A T E T H E S I SC A R I N G F O R P E O P L E W I T H I N T E L L E C T U A L A N D D E V E L O P M E N T A L D I S A B I L I T I E S

Licentiate thesis R&D report 2021: number

Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö University

© Marie Appelgren 2021

Cover Illustratiopn: The puzzle is incomplete if pieces are missing ISBN 978-91-7877-153-0 (print)

ISBN 978-91-7877-154-7 (pdf) ISSN 1650-2337

DOI 10.24834/isbn.9789178771547 Holmbergs, Malmö 2021

MARIE APPELGREN

CARING FOR PEOPLE

WITH INTELLECTUAL AND

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

How can it be experienced and perceived by

registered nurses?

Malmo University, 2021

Faculty of Health and Society

This publication is also available at: www.mau.diva-portal.org

For reflection

If One Is Truly to Succeed in Leading a person to a Specific Place,

One must First and Foremost Take Care to Find Him Where He Is and Begin There. This is the secret in the entire art of helping.

Anyone who cannot do this is himself under a delusion if he thinks he is able to help someone else.

In order truly to help someone else,

I must understand more than he-but certainly first and foremost understand what he understands.

If I do not do that,

then my greater understanding does not help him at all. If I nevertheless want to assert my greater understanding,

then it is because I am vain or proud,

then basically instead of benefiting him I really want to be admired by him.

But all true helping begins with a humbling.

The helper must first humble himself under the person he wants to help and thereby understand that to help is not to dominate but to serve,

that to help is not to be the most dominating but the most patient, that to help is a willingness for the time being to put up with

being in the wrong

and not understanding what the other understands.

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 9 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ... 11 ABBREVIATIONS ... 12 DEFINITIONS OF TERMS ... 13 INTRODUCTION ... 15 BACKGROUND ... 17 Nursing ... 17Intellectual and developmental disabilities over time ... 17

Context and practice settings for nursing and caring targeting intellectual and developmental disabilities ... 19

Care needs of patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities ... 21

The current knowledgebase in nursing targeting patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities ... 22

AIM ... 24

METHODS ... 25

Design ... 25

Study setting and context ... 27

Recruitment and participants ... 27

Data collection ... 28

Data analysis ... 29

Pre-understanding ... 30

RESULTS ... 34

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 39

Legitimacy ... 39

Trustworthiness ... 41

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ... 44

CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 50

FUTURE RESEARCH ... 52

SAMMANFATTNING PÅ SVENSKA ... 53

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 57

ABSTRACT

Registered nurses [RNs] are within the frontline of professional nursing and are expected to provide a diverse range of health care services to a varied and heterogenic group of patients. They are bound by a code of ethics that man-dates that nurses respect all human rights regardless of the patient’s abili-ties or functional status. However, research implies that RNs do not feel ade-quately prepared to support patients with intellectual and developmental disa-bilities [IDD], and that patients with IDD are often misinterpreted and misun-derstood in care. Gaining in-depth knowledge about how RNs can experience

nursing for this group of patients is therefore of great importance. The overall

aim of this thesis was to describe, appraise, integrate and synthesise knowledge concerning nursing for patients with IDD. A further aim was to explore and describe Swedish RNs’ perceptions of providing care for patients with IDD within a home health care setting.

This thesis consisted of two studies designed to investigate various aspects of nursing and caring for patients with IDD. Paper I was a systematic review us-ing a meta-ethnographic approach, and Paper II was an interview study usus-ing a qualitative descriptive, interpretive design. Data was collected by systematic data base searches (Paper I), and by individual interviews (Paper II). The sys-tematic review comprised 202 RNs (Paper I) and the qualitative descriptive study comprised 20 RNs. In the systematic review, data was analysed by a Line of Argument Synthesis [LOAs] as described by Noblit and Hare (1988), while the data in Paper II was analysed by content analysis.

Nurses’ experiences and perceptions of nursing patients with an IDD could be understood from 14 LOAs. Six of these were interpreted to reflect a tentatively more distinctive and unique conceptualisation of RNs’ experience of nursing for this group of patients. The remaining eight LOAs were interpreted to re-flect a conceptualisation of nursing per se that is a universal experience

regard-less of context or patient group (Paper I). In Paper II, the nurse’s perceptions

hostage in the context of care, Care dependant on intuition and proven expe-rience and Contending for the patient’s right to adequate care.

Absence of understanding and knowledge about IDD might be an explanation for the “otherness” that still appears to surround this group of patients. Con-centrating on the person behind the disabilities label as well as on abilities in-stead of disabilities could be a reasonable approach in nursing care for pa-tients with IDD. Thus, implementing nursing models focusing on person-centred care could support RNs to moderate the health and care inequalities that are still present among patients with IDD (Paper I).

As a result of the home health care context and its organisation, the RNs per-ceived themselves as unable to provide care in accordance with their profes-sional values. Not mastering the available augmentative and alternative com-munication tool additionally meant having to provide care based on second-hand information from support staff. The RNs also perceived that caring for this group of patients involved a daily battle for the patient’s rights to receive the right care at the right place and time and by the right person (Paper II). Hence, a broad base of evidence on what actually works best in clinical prac-tice for this group of patients, particularly in the home care context, is still needed.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

This thesis for the degree of Licentiate is based on two Papers, referred to in the text by Roman numbers. The published Papers have been reprinted with permission from the publishers.

I. Appelgren, M., Bahtsevani, C., Persson, K. & Borglin, G. (2018). Nurses’ experiences of caring for patients with intellec-tual and developmental disorders: a systematic review using a meta-ethnographic approach. BMC Nursing, 17, (51). Doi: 10.1186/s12912-018-0316-9

II. Appelgren, M., Persson, K., Bahtsevani, C. & Borglin, G. (202x). Swedish Registered Nurses’ Perceptions of Caring for Patients with Intellectual and developmental disabilities: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Health & Social Care in the Community [Accepted 07.01.21]

ABBREVIATIONS

AAC Augmentative and Alternative Communication ANA American Nurses Association

APA American Psychiatric Association CB Challenging Behaviour(s)

DSM V Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition

EBP(s) Evidence-Based Practice(s) HCP Health Care Professional(s)

ICD-11 International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics 11th edition

ICF International Classification of Functioning, Disabilities and Health

ICN International Council of Nurses

IDD Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities LOAs Line of Argument Synthesis

PCC Person-Centred Care

QES Qualitative Evidence Synthesis RN(s) Registered Nurse(s)

SSF The Swedish Society of Nursing (Svensk sjuksköterskeförening) UN United Nations

WMA World Medical Association WHO World Health Organization

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: [IDD] (earlier conceptual-ised as intellectual disabilities) manifests itself during the developmental period (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and means a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and apply new skills (impaired intelligence). This results in a reduced ability to cope inde-pendently (impaired social functioning) with a lasting effect on development (WHO, 2021).

Nursing: The concepts nursing and caring are often intertwined and used synonymously. In this thesis, nursing is understood as a human science, a pro-fession and a discipline (Meleis, 2017). As a propro-fession, nursing has a system-atic body of knowledge that provides the framework for the profession’s prac-tice; standardised, formal higher education leading to a licence; commitment to provide a service that benefits individuals in the society; a unique role that recognises autonomy, responsibility and accountability; control of practice re-sponsibility of the profession through standards and a code of ethics and a na-tional professional organisation. As a discipline, nursing knowledge and caring form the critical dyad for nursing (Finkelman & Kenner, 2017).

Caring: In this thesis, caring is understood as the clinical practice registered nurses are performing, hence, “the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; al-leviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response; and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations” (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2015).

Registered Nurse: A person who has completed a programme of basic, generalised nursing education and is authorised by the appropriate regulatory authority to practice nursing in his/her country. The nurse is expected to carry out person-centred care, collaborate with other health care professionals, em-ploy evidence-based practice, apply quality improvement, deliver safe care, and utilise informatics (Cronenwett et al., 2007; Swedish Society of Nursing, 2017).

Ordinary living: Apartment or private house where people live “at home” (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2021).

Assisted living: Various kinds of municipal housing for people with intel-lectual and developmental disabilities, e.g. group homes or service homes (Na-tional Board of Health and Welfare, 2021).

Community home health care: “health care when it is provided in the pa-tient's home or equivalent and where the responsibility for the medical measures is coherent over time” (authors translation). Measures and interven-tions must have been preceded by care and nursing planning. Home health care is provided in both ordinary and special housing, as well as in daily activ-ities and day activactiv-ities. Home care must be separated from outpatient care (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2008).

INTRODUCTION

Registered nurses (RNs) work within the framework of professional nursing and are expected to provide a diverse range of health care services to a varied and heterogenic group of patients (Desroches et al., 2018; Ganann et al., 2019), but research implies that RNs do not always feel adequately prepared to support or to care for patients with intellectual and developmental disabili-ties (IDD) (earlier conceptualised as intellectual disabilidisabili-ties) (Wilson et al.,

2018). Research indicates that patients with IDD often are misinterpreted and misunderstood in care (Lewis et al., 2016). Health and social care organisa-tions in developed countries are nowadays experiencing a noteworthy increase in the number of people with IDD growing older and reaching retirement age (65 years).

This group of people are, according to Lay (2014), part of a larger post-World War II birth cohort which have had access to a vastly improved medical ser-vice as well as improved hygiene, diet and physical exercise standards. This has resulted in a significantly improved health status (ibid) in comparison to those before them given the same diagnosis. However, this does not necessari-ly mean they are living healthy lives. In fact, there is evidence that people with IDD still experience poorer health and have a shorter lifespan, compared to the general population. Heslop and colleagues (2014) reported that problems with co ordination between and across services contributed to premature deaths among patients with IDD. While Trollor and colleagues (2017) report-ed that adults with IDD experiencreport-ed premature mortality and were over-represented among avoidable deaths. It is likely that RNs will provide care to this group of patients in a variety of different health care settings. It is also probable that this patient group in general presents with complex health

sup-port needs when needing to acquire relevant and qualitative health services as well as nursing care. How well RNs are taught and prepared to care for this group of patients during the nursing education is, however, not well described. However, a recent national audit of 31 Australian universities’ nursing curric-ulum content conducted by Trollor and colleagues (2016) uncovered substan-tial variability in essensubstan-tial IDD content with numerous gaps evident. Unfortu-nately, this might also be reflective for the Swedish universities’ nursing cur-riculum content.

In addition, as patients with IDD nowadays have moved out from the institu-tions and into the community, so have the RNs who are expected to care for them. These shifts have had consequences for the patients with IDD, as well as for the delivery of care. Rather than the delivery of care in institutional set-tings, community and primary care has now been designated as the main pro-vider of health care to people with IDD. RNs based in community care teams are therefore often their first contact point with health care services and much of the care for people with IDD is nowadays described to take place at home (Jaques et al., 2018).

Thus, as RNs often are on the frontline of both primary and secondary care, it appears important to describe and integrate the current available knowledge-base in relation to how RNs can experience caring for this group of patients (Paper I). Knowledge about how the care delivered in the home health care setting can be described and perceived by RNs additionally seems imperative (Paper II). Such knowledge is critical in the development of an evidence-based care targeting patients with IDD, but also in supporting the RNs to work against the health inequalities apparently still present among this group of pa-tients.

BACKGROUND

Nursing

Nursing is nowadays both a profession and a discipline (Finkelman & Kenner, 2017). As a profession, nursing has a systematic body of knowledge that pro-vides the framework for the profession’s practice: standardised, formal higher education leading to a licence; commitment to provide a service that benefits individuals in the society; a unique role that recognises autonomy, responsibil-ity and accountabilresponsibil-ity; control of practice responsibilresponsibil-ity of the profession through standards and a code of ethics and a national professional organisa-tion. An RN is a person who has completed a programme of basic, generalised nursing education and is authorised by the appropriate regulatory authority to practice nursing in his/her country (Cronenwett et al., 2007; Swedish Society of Nursing, 2017). As a discipline, nursing knowledge and caring forms the critical dyad for nursing (Finkelman & Kenner, 2017). Nursing practice fol-lows the nursing process of assessment, diagnosis, outcome identification, planning, implementation and evaluation. The RN collects data as part of the assessment process, uses critical thinking skills to synthesise the information, formalises a nursing diagnosis and identifies specific priorities and outcome measures. The health plan of care and interventions is rooted in the assessment process and based on evidence-based practice (Hahn & Fox, 2016). Meleis (2017) describes nursing as a human science, a practice-oriented discipline, a caring discipline and a health-oriented discipline.

Intellectual and developmental disabilities over time

Although all people are unique and there can be a broad variation in regard to each individual’s unique abilities and limitations, IDD results in a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and

apply new skills. This results in a reduced ability to cope independently, and begins before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020). The prevalence of IDD is estimated at 2.5% of the population internationally and 1.5% nationally, and is reported to be twice as common in males compared to females (Bourke et al., 2016; Drake et al., 2015). Over time many changes have taken place in parallel for people with IDD, such as the way individuals with IDD have been named and catego-rised. Terms formerly used, such as idiot, imbecile, feebleminded, mentally subnormal, moron, mentally deficient and retard, are now seen as highly pejo-rative and stigmatising, although at the time of their use they were acceptable terms in the scientific literature (Nehring & Lindsey, 2016). There is no inter-national consensus of which term is best to use. The term intellectual disabili-ties is used in the U.S. and in many parts of the English-speaking world, the terms intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities are used synony-mously in Canada and the terms learning disabilities and learning difficulty are used in the United Kingdom (Parmenter, 2011). The diagnostic instrument DSM V (APA, 2013) uses the term Intellectual Disabilities (as equivalent with Intellectual and developmental disabilities) and the diagnostic instrument ICD-11 (WHO, 2020) uses the term Disorders of intellectual development. This thesis uses the term Intellectual and developmental disabilities [IDD].

Over time, there have also been different models in the way individuals with IDD have been explained. The currently prevailing model is the integrative bi-opsychosocial/relational model, in which disabilities is explained as an interac-tion between features of the individual and features of the overall context in which the individual lives (Tideman, 2015; WHO, 2002). The last major change refers to how patients with IDD have been cared for. By 1900, care was delivered in institutions designed to house large numbers of patients. The institutions were often built outside of the cities in order to separate the tients from the general population (Nehring & Lindsey, 2016). The care of pa-tients with IDD in institutions altered dramatically in the 1960s and 1970s with scandals in England, Wales and the USA revealing the conditions in these institutions (ibid.). Following these scandals, Bank-Mikkelsen in Denmark and Nirje in Sweden in 1969, with further development by Wolfensberger (1972), introduced the principles of normalisation. This was a paradigm shift both na-tionally and internana-tionally for patients with IDD who were subjected to insti-tutionalisation (Nehring & Lindsey, 2016). The principles focus on patients

living with IDD having the right of self-determination and integration into so-ciety (Wolfensberger et al., 1972). These writings had a huge impact on the subsequent deinstitutionalisation and community living and influenced the de-velopmental model which outlined the need for care across the lifespan (Scheerenberger, 1987). The principles also influenced an understanding and changing experiences about patients with IDD and the sort of opportunities that should be available to them (Thomas & Woods, 2003). The principles fi-nally led to reforms that aimed to normalise living standards and integrate people with IDD into society (Tideman, 2015).

Context and practice settings for nursing and caring targeting intellectual and developmental disabilities

Lakeman (2013) highlights the importance of offering a rich description of the general context in which the research has been conducted. Only then can the global audience understand practice. During the latter part of the 20th century,

the shift toward the professionalisation of nursing led to the development of university study programmes for all nurses across the western world (Francis, 1999). This period also coincided with a shift in disabilities policy frame-works, and closure of large residential institutions for patients with IDD. An unfortunate side effect this closure was the impact on the RN’s role within the field of IDD, whose specialty skills were no longer seen as necessary. The ar-gument at that time was that necessary supports could be provided by staff trained to assist activities of daily living. Another argument was that an RN with general nursing education, rather than a sub-specialty RN, was all that was required to provide care to an individual with IDD (Wilson et al., 2018). Thus, historically, nurses most often worked in large institutions that housed patients with IDD (Nehring & Lindsey, 2016). Today, most RNs caring for patients with IDD work in community settings of various types, such as assist-ed living, ordinary living, special assist-education settings in schools or primary health care clinics (Auberry, 2018; Wilson et al., 2020). This varied landscape of settings may propose diverse expectations and role definitions for the RN. The transition of individuals out of institutions and into community settings has further added to the ambiguous role of the RN caring for patients with IDD. RNs working in community settings in this field may work as consult-ants, supervisors, or administrators. However, these different roles are unclear and the value that RNs bring to patients with IDD in community settings is not acknowledged in the current literature (Auberry, 2018; Wilson et al.,

2020). Researchers have found that RNs face varied challenges in the field of IDD: a lack of education regarding this population, the health care complexity of this patient group, an unclear role, varied practice settings, the nursing model of care controversy, and a heavy workload (ibid.). Auberry (2018) con-cluded that the IDD field requires a synthesised approach to health care man-agement that currently does not appear to exist across settings. Although most RNs work in community settings, patients with IDD of all ages and ethnicities are found in all health care settings, including hospital care. Hence, RNs are likely to meet patients with IDD regardless of which setting or context they might work within. Therefore, it seems as a necessity to prepare nursing stu-dents to care for this patient group. Furthermore, development of standardised principles and evidence-based practises is of huge importance. The RN role within the field of IDD also needs to be clarified. Finally, an increase in nurs-ing research for this patient group and area of practice are warranted.

In Sweden, the county councils are the regional providers of health care, while the municipalities are responsible for the care of people with IDD living in service homes or in group homes in accordance with the Act Concerning Support and Service for People with Certain Functional Impairments (Swedish Code of Statues, 1993:387). The Act Concerning Support and Service for People with Certain Functional Impairments (Swedish Code of Statues, 1993:387) is an entitlement law and entails supplementary support for persons with significant and long-term functional disabilities. The support aims at au-tonomy, influence, respect and participation in everyday life for the individual. The Act applies to: i) persons with intellectual disabilities and people with au-tism or conditions similar to auau-tism (Pk1), ii) persons with significant and permanent intellectual functional disabilities following brain damage as an adult (Pk2) and iii) persons, who as a result of other serious and permanent functional disabilities, which are clearly not the result of normal ageing, have considerable difficulties in everyday life and a great need for support or service (Pk3).

The care is guided by RNs in accordance with the Health and Medical Services Act (Swedish Code of Statues 2017:30); however, the main providers of support and service in the municipalities are social pedagogues, support pedagogues and support assistants/enrolled nurses (hereafter reffered to as support staff) working in accordance with the Act Concerning Support and

Service for People with Certain Functional Impairments (Swedish Code of Statues, 1993:387). This entails challenges in the teamework since the boundaries between the Health and Medical Services Act (Swedish Code of Statues 2017:30) and the Act Concerning Support and Service for People with Certain Functional Impairments (Swedish Code of Statues, 1993:387) are fluctuating. Absent from the literature is any kind of detailed description of these diverse settings in the Swedish context.

In the living facilities, the support staff are on duty around the clock to provide regular care and support in daily living and are situated in the common premises. Social pedagogues supervise the daily work at the service and group homes and have the responsibility for implementing decided pedagogical methods. RNs are on call and accessible around the clock. RNs have the responsibility for several group homes and are situated in their own office, apart from the living facilities. During day-time, RNs caring for patients with IDD work exclusively within the disabilities support depart-ments. At night-time and weekends, RNs work in the whole community. The university education aims to equip the Swedish nursing students with the knowledge, competencies and skills needed to take charge of nursing care. How well Swedish nursing students are equipped to meet and care for this pa-tient group is not very well described.

Care needs of patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Today, people with IDD are growing older and reaching retirement age (65 years). This group of people is, according to Lay (2014), part of a larger post-World War II birth cohort who have had access to a vastly improved medical service as well as improved hygiene, diet and physical exercise standards. This has resulted in a significantly improved health status (ibid) in comparison to those before them given the same diagnosis. However, this does not necessari-ly mean they are living healthy lives. In fact, there is evidence that people with IDD still experience poorer health and have a shorter lifespan compared to the general population. This is mainly due to their lifestyles, as many of them get little exercise, have poor diets and are overweight or obese (Coughlan et al., 2020; Sandberg et al., 2017), resulting in a frailty that predisposes them to an earlier burden of disease (Inglis et al., 2014; Lollar & Phelps, 2016). Adding on to this is the understanding that this group of people also has an increased

risk of suffering from co- or multi-morbidities compared to the general popu-lation. They are therefore at high risk of developing secondary conditions (Cooper et al., 2015). That is, if they are less able to access health care, their vulnerability to secondary conditions increases (Inglis et al., 2014; Lollar & Phelps, 2016). Researchers have reported that problems with co ordination between and across services contributed to premature mortality and deaths among people with IDD (Heslop et al., 2014), deaths that were avoidable (Trollor et al., 2017). Hence, this population has specific needs that are likely to present challenges for health care services and RNs providing them care.

The current knowledgebase in nursing targeting patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Reviewing the literature, it appears that much research including this patient group seems to have been conducted after the deinstitutionalisation and within areas other than nursing, such as social work. However, in the 21st century,

there has been a growing knowledgebase internationally within nursing in-cluding patients with IDD. The majority of research has been conducted in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Anderson and Bigby (2017; 2020) and Emerson and colleagues (2020) have investigated the meaning of inclusion in society for people with IDD and the impact on their wellbeing. Donelly et al. (2018) have explored the importance of a support network for people with IDD when promoting participation and engagement in society. Furthermore, Trollor and colleagues (2017) have investigated mor-tality and its causes in people with IDD. In a research project across Europe, Haveman and colleagues (2011) explored ageing and health status in adults with intellectual disabilities. Adam et al. (2020) have investigated palliative care for patients with IDD and explored how support staff best can communi-cate about death and dying with patients with IDD. Doody and colleagues (2020) have investigated clinical placements in IDD nurse education. Desroch-es and colleaguDesroch-es (2018)

investigated

RNs’ attitudes and emotions toward caring for patients with IDD and the effects this had on care outcomes. Northway and colleagues (2016; 2017) have investigated educational needs among support staff when caring for older patients with IDD. Lewis and col-leagues (2016) in their review investigated RNs’ experiences of caring for pa-tients with IDD in an acute care setting and, Wilson and colleagues (2018) ex-plored RNs working in IDD settings and the uniqueness of their role. Lewis and colleagues (2020) furthermore investigated demographic profiles of the

IDD nursing workforce in Australia, and Wilson and colleagues (2019; 2020) have explored educational needs, including clinical training, among RNs when caring for this patient group.

In Sweden, research by nursing academics including this patient group has been conducted in recent years. In their study, Gimbler Berglund and col-leagues (2017) investigated RNs’ experiences of caring for children with au-tism spectrum disorders in an anaesthesia and radiographic context. Further-more, there has been research about healthy ageing among patients with IDD. Johansson and colleagues (2017) explored this from the frontline manager’s perspective and Alftberg and colleagues (2019) from an assistant staff perspec-tive. Holst and colleagues (2018) investigated how assistant staff and frontline managers could detect signs of dementia among this patient group. Axmon and colleagues (2018) investigated psychiatric diagnoses in relation to the se-verity of IDD and challenging behaviour [CB]. Further, they explored falls re-sulting in health care among older people with intellectual disabilities (Axmon et al., 2019a), and hospital readmissions among older people with IDD in comparison with the general population (2019b). Lastly, in her thesis, Berlin Hallrup (2019) investigated experiences of everyday life and participation for people with IDD. However, there seems to be a lack of research exploring ex-periences and perceptions of nursing for this patient group from those who ac-tually are in charge of care, that is the RNs, especially in a home health care context where most of caring today takes place. Hence, there is a knowledge gap on what actually works best in clinical practice for this group of patients.

AIM

The overall aim of this thesis was to describe, appraise, integrate and synthe-sise knowledge concerning caring for patients with intellectual and develop-mental disabilities. A further aim was to explore and describe registered nurs-es’ perceptions of providing care for this group of patients. More specifically, the aims of the thesis were the following:

• To develop a conceptual understanding of registered nurses’ experi-ences of caring for patients with intellectual and developmental dis-abilities (Paper I).

• To explore and describe Swedish RNs’ perceptions of providing care for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a home health care setting (Paper II).

METHODS

Design

This thesis has its point of departure in a constructivist paradigm. According to the ontology and epistemology of social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Lincoln & Guba, 2013), all knowledge is derived from and maintained by social interactions, shaped by human experiences and so-cial contexts, and is therefore best studied within its socio-historic context. Even though we live in the same world, we do not necessarily give the world the same meaning. Furthermore, we cannot separate ourselves from what we know. The researcher and the object of investigation are linked such that who we are and how we understand the world is a central part of how we under-stand ourselves, others and the world. Research is concerned with underunder-stand- understand-ing how individuals interpret the world within their context (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Lincoln & Guba, 2013). Therefore, this thesis consists of two studies designed to investigate experiences and perceptions of caring for patients with IDD. Paper I was a systematic review using a meta-ethnographic approach (Noblit & Hare, 1988), aiming to synthesise and integrate the knowledge base and to develop a conceptual understanding regarding RNs’ experiences of caring for patients with IDD. The result of Paper I guided the development of Paper II. Paper II was an interview study using a qualitative descriptive, interpretive design (Sandelowski, 2000), aiming to explore and de-scribe Swedish RNs’ perceptions of caring for patients with IDD in a home health care setting.

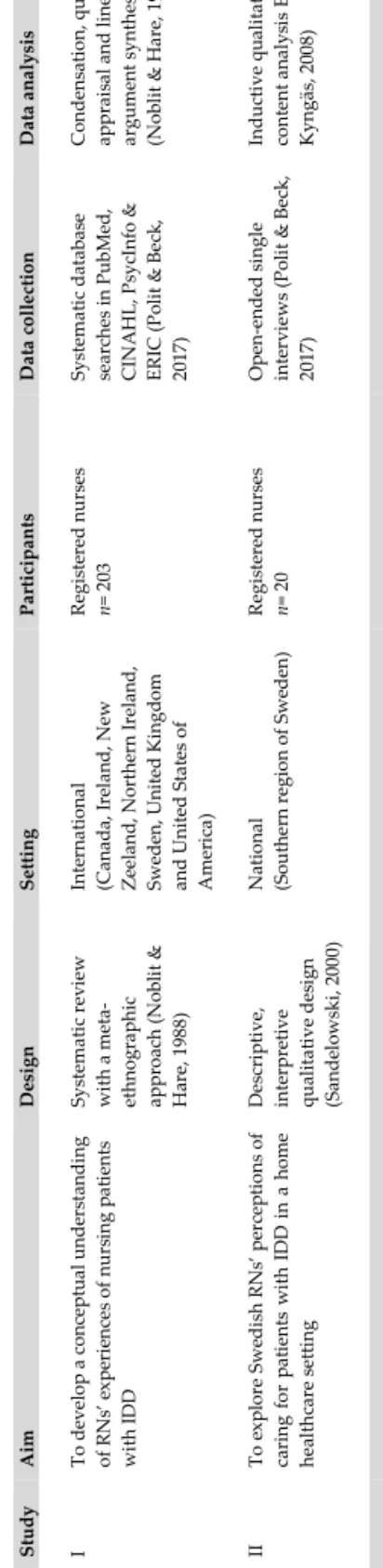

Tab le 1. O ver vi ew o f s tu di es St udy A im D es ig n Se ttin g Pa rt ic ip ant s D at a c oll ec tio n D at a an al ys is I To de vel op a c on cep tu al u nde rs ta ndi ng of R N s’ e xp er ie nc es o f nu rs ing p at ients wi th IDD Sy stema tic rev iew wi th a m eta -ethno gr ap hi c ap pro ac h ( N ob lit & H ar e, 198 8) Inte rn ati on al (Can ad a, Ire la nd , N ew Z eel and , N or the rn Ir el an d, Sweden, Un ited K ing do m and Uni ted S ta tes o f Am er ic a) R eg is te red nu rs es n= 2 03 Sy stema tic da ta ba se sea rc hes in P ubM ed, C IN A H L, P sy cI nf o & ER IC (P ol it & Bec k, 2017 ) C ondens ati on, q ua lity ap pra is al an d lin es o f ar gu me nt s ynthes is (N ob lit & H ar e, 1 988 ) II To e xp lo re Swe di sh R N s’ p er cep tio ns o f ca ri ng fo r p at ients w ith IDD in a ho m e hea lthc ar e s ett ing Des cr ip tive, inte rp re tive qu al ita tiv e des ig n (Sa nde lo ws ki , 2 00 0) N at io na l (So uther n r eg io n o f Swe den) R eg is te red nu rs es n= 2 0 O pe n-ended s ing le inte rv iews (P ol it & Bec k, 2017 ) Indu ct ive q ua lit at iv e co nt ent a na ly si s El o & K yn gäs , 2 008)

Study setting and context

For Paper I, the single studies (n= 18) included in Paper I were performed in the UK (n= 9), Ireland (n= 3), Northern Ireland (n= 2), USA (n= 1), Canada (n= 1), New Zealand (n= 1), and Sweden (n= 1). The data set was comprised of 202 RNs, where 91 were specialised in IDD and 111 were general RNs. Three studies were performed in a hospital setting and 15 studies were per-formed in a residential andcommunity services setting. Paper II was conduct-ed in the southern part of Swconduct-eden, in an urban city and four smaller communi-ties, with respectively 22,000, 45,400, 125,000, 148,000 and 344,000 inhab-itants. RNs, working both day-time and night-time in a home health care set-ting within the community, were recruited from health care services and disa-bilities support service administrations. Twelve RNs were caring only for pa-tients with IDD and eight RNs were caring for papa-tients with and without IDD. Seven of the RNs had a specialist education and 13 of the RNs had a general-ist education.

Recruitment and participants

In Paper I, the identification of studies followed a given systematic approach (PRISMA-P) (Moher et al., 2009). A detailed search strategy was developed in collaboration with a specialist librarian using a modified form (Lord et al., 2017) of the SPIDER tool developed by Cook et al. (2009), specifying terms for sample, phenomenon of interest and research design. The SPIDER tool was useful to identify words suitable for the literature search. The literature search was conducted in the databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and ERIC, as well as a manual search in the reference list of individual studies possi-ble for inclusion (Polit & Beck, 2017). To identify pertinent search terms

in the databases, search terms were compared with each database system of

subject headings. A combination of free-text and indexed medical subject headings was used. The search terms were combined with the Boolean op-erator “OR” to make the search sensitive and then with the Boolean oper-ator “AND” to assure specificity within the search strategy (ibid.).

Free-text terms were also used to access studies not yet indexed (Shaw et al.,

2004). Studies were included if they (i) were in English, (ii) were published in a peer-reviewed journal, (iii) used qualitative methods and demonstrated qual-itative analysis and (iv) reported the experiences of caring for adults with IDD regardless of health care context. These inclusion criteria were essential if the research question was to be answered. Studies were excluded if data

from RNs could not be distinguished from those of other health care profes-sionals or if participants could not be identified as RNs.

In Paper II, inclusion criteria were RNs working in the community within home health care caring for patients with IDD. A multi-stage sampling tech-nique (Battaglia, 2008) was used, in which sampling was done sequentially across three hierarchical levels in the organisations where the RNs were em-ployed; hence, Paper II was established within these organisations. The first author (MA) contacted the department managers within the communities through e-mail, asking for permission for an interview study to take place within their organisation. A letter was sent to them with a description and aim of the study. With the department managers’ permission, the first author con-tacted the front-line managers within the disabilities departments through e-mails and by telephone, asking for registered nurses’ participation. A letter was also sent to them with a description and aim of the study. The front-line managers provided MA with names, e-mail addresses and telephone numbers of RNs interested in taking part in the study. Finally, the RNs were contacted by the first author, through e-mails and by telephone. A letter was sent to them with a description and aim of the study. Initially, 23 RNs expressed an interest and 22 were interviewed. The remaining RN found it difficult to ar-range a time to meet. Two of the interviews were of a too poor recorded quali-ty for transcription, leaving twenquali-ty interviews included in the data set.

Data collection

In Paper I, the literature search resulted in 10,403 studies at abstract level. Af-ter duplicate removal and on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criAf-teria, the first author (MA) read 66 studies in full text, and a further 35 studies were excluded, leaving 31 studies assessed as eligible for inclusion. The manual search in the reference list of individual studies gave no additional studies of relevance. A data extraction and quality appraisal protocol was developed based on the ideas of Toye et al. (2013) and Schütz (1967) regarding first- and second-order constructs commonly used in meta-ethnographic studies to dis-tinguish the data (Toye et al., 2013). The methodological quality appraisal of the studies was conducted, following the conceptual model for quality appraisal by Toye et al. (2013), that is, i) Conceptual clarity: How clearly has the author(s) articulated a concept that facilitates theoretical insight? and ii) Interpretive rigor: What is the context of the interpretation? How inductive

are the findings? Has the interpretation been challenged? Each study was thereafter categorised as either a key Paper (KP), a satisfactory Paper (SP), a fatally flawed Paper (FFP) or an irrelevant Paper (IRP). The protocol helped to focus the data extraction. The first author (MA) critically appraised and ex-tracted data from all 31 included studies. Two of the co-authors (CB and KP) acted as second reviewers of 10 studies each, while the third co-author (GB) acted as second reviewer of 11 studies. If there was any disagreement between the reviewer pairs, a third reviewer reviewed the studies, which occurred in one case. After this appraisal, 18 studies out of the 31 were included in the systematic literature review.

In Paper II, unstructured single face-to-face interviews were performed (Pat-ton, 2015). Four pilot interviews were conducted in order to control the suita-bility of the research question, and to gain experience and skills in interview techniques. These pilot interviews were not included in the final data set. Be-fore the interview began, the researcher again explained the study’s aim, the right of withdrawal and the handling of the data. All the interviews were con-ducted by the first author (MA) between September 2018 and May 2019. In order to enable a calm and friendly atmosphere, the RNs could choose the lo-cation for the interview; hence, the interviews took place in a clinical setting (n= 19) and at the researcher’s office (n= 1). Each RN was individually inter-viewed on one occasion. The interview began with letting the RN read a pa-tient case based on the findings from Paper I to facilitate reflections and narra-tion. All interviews thereafter began with the open-ended overarching question “How do you as an RN perceive caring for this group of patients?”, with gen-eral probing (Patton, 2015), such as “What do you mean?”, “Can you please give me an example?” and “Can you tell me more?” This research method was useful because it allowed the Swedish community RNs to discuss their perceptions of caring for patients with IDD in a home health care setting, and the probes gave the RNs the opportunity to provide more detailed information based on their initial answer (ibid.). The interviews lasted between 30 to 80 minutes (mean 37 minutes), were recorded and transcribed verbatim, resulting in 291 pages of data (1.5 space).

Data analysis

In Paper I, data from the included Papers result section was transferred on to a synthesis matrix including study author(s) and translatable second-order

con-cepts with supporting text explaining and describing the concept for each study. The text was condensed into idiomatic translations focusing on mean-ing of the text rather than the literal translations of words (Noblit & Hare, 1988). The meaning of all translatable second-order concepts was continuous-ly compared which helped in identifying similarities and differences within and across the included studies. A line of argument [LOA] synthesis was then for-mulated, interpreted to represent (ibid.) an overarching conceptual under-standing of the experience of caring for patients with IDD. The intention of meta-ethnography is to bring together conceptual categories into a line of ar-gument that is greater than the sum of its parts. Therefore, the conceptual model goes beyond the constituent elements (Noblit & Hare, 1988).

The text included in the analysis in Paper II contained 103 pages (1.5 space) and was subjected to inductive qualitative content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). Both manifest and latent data was analysed. The transcribed texts were read several times to grasp of the whole and to make sense of the data. This process included open coding, where notes and tentative headings were writ-ten in the margins while reading the text (i.e., naïve reading). The headings were collected from the margins onto mind maps, and then transferred to cod-ing sheets. Meancod-ing units, that is, a piece of any length that refers to the expe-riences of caring for patients with IDD, were extracted into condensed mean-ing units. The meanmean-ing units were then labelled with codes. The codes were compared and brought together in terms of their similarities and differences to formulate sub-categories which later on in the analysis process submerged into three distinct categories (ibid.). All authors participated in the continual pro-cess of iteration by focusing on the whole and the parts; this was done to check and confirm the interpretations, that is, investigator triangulation (Den-zin, 2006). Intercoder agreement (Neuman, 2020) was also applied to verify the process of interpretation until the categories emerging from the data were found to be mutually exclusive.

Pre-understanding

Pre-understanding originates from something that the researcher is familiar with, either context or tradition, and it might facilitate, but also constrain the understanding (Nyström & Dahlberg, 2001). The author of this thesis is an enrolled nurse, and has been working as a support assistant in assisted living centres for persons with IDD for the last ten years. She also has a 25-year-old

son with mild IDD. Hence, she has not been an “unknowingly blank page” throughout the research process. However, she has the perspective of a sup-port assistant, a pedagogical perspective rather than the RNs perspectives of caring. The author’s experience and knowledge may have facilitated the inter-actions with the RNs. This can be seen as both a strength and a weakness (Patton, 2015). The strength is that the researcher is not an RN and does not have a pre-understanding regarding how RNs think and could not anticipate RNs’ narratives. The potential risk, that data collection was guided by the au-thor’s pre-understanding in the topic of research and may have resulted in the author posing leading questions or missing following up ques, is a weakness. However, the author tried to meet all RNs with an open mind by focusing on each individual RN and his/her narrative.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethics is about what is right, good and virtuous. Research ethics is about pro-tecting others, minimising harm and increasing the sum of good. Research eth-ics is also about showing consideration for the informants (Israel & Hay, 2006). Researchers do not have an inalienable right to conduct research in-volving other people (Oakes, 2002). Researchers continuing to have the free-dom to conduct such work is, in large part, the product of individual and so-cial goodwill and depends on the researchers acting in ways that are not harm-ful and are just. Ethical behaviour may help assure the climate of trust in which the researchers continue their socially useful labours (Israel & Hay, 2006). By caring about ethics and by acting on that concern, researchers pro-mote the integrity of research. Since much of what researchers do occurs with-out anyone else “watching”, there is ample scope for them to conduct them-selves in improper ways. If researchers can behave ethically, society can be more confident that the results of work they read and hear about are accurate and original. Since researchers build on each other’s advances, poor practices affect not only the individual and professional reputation, but also the veracity and reliability of the individual and collective works (Israel & Hay, 2006). There is no conflict of interest in this thesis since none of the authors has done any research in this field. The intended utility of this thesis is to improve the care for patients with IDD and add new knowledge to the already existing knowledge base.

There is no need for ethical approval regarding conducting a systematic re-view. However, occasionally it occurs that there are studies with insufficiently described ethical considerations and there may be doubts about the morality

of using their results in the synthesis (Weingarten et al., 2004). For Paper I, studies were excluded if they did not have a paragraph with ethical considera-tions and approval from an ethical review board. However, there were no such studies. Ethical approval for Paper II was given by the Ethical Review Board in Lund (Ref. no. 2018/472).

The World Medical Association [WMA] (WMA, 2013) has developed the Declaration of Helsinki, which contains ethical principles for medical research involving humans: the ethical principles of autonomy, non-maleficence, benef-icence and justice. These principles guided the work with this thesis. The prin-ciple of autonomy relates to a person’s right to make decisions regarding par-ticipation in research based on knowledge (ibid.). Before the study, the RNs were provided with written and oral information about the purpose of the study and the data collection procedure, funding, eventual conflicts of inter-ests, the expected benefits of the study and eventual risks and discomfort from the impact of the study. The RNs were provided with information that partic-ipation was voluntary and that they were entitled to withdraw at any time and without stating a reason. Once the participants received and understood the information, they provided written consent. Before the interview began, the information was repeated. Secondly, the principle of non-maleficence refers to the obligation of not doing harm and the principle of beneficence involves do-ing good and actdo-ing for the benefit of others. The RNs were assured of confi-dentiality (WMA, 2013) and all identifying information from the transcribed text was removed. The RNs’ names were replaced with pseudonyms in the form of a capital letter and a number and only the authors had the code key. The transcripts were stored in a locked cabinet and the codes in another locked cabinet, separate from each other. Recorded interviews were stored on the university’s home catalogue. When presenting the findings, no individual information about the participants was given. Finally, the principle of justice refers to justice and equal opportunity to gain access to various resources (WMA, 2013). The RNs were welcome to participate in the study regardless of gender, ethnicity, religion, political standpoint or sexual identity.

RESULTS

The analysis in Paper I indicated that RNs’ experiences of caring for patients could be understood from 14 line of argument syntheses [LOAs] (coded from A to N). Six of the LOA syntheses (marked with an *) were understood to re-flect a unique conceptualisation of RNs’ experiences of caring for patients with IDD. The remaining eight LOA syntheses were interpreted to represent a conceptualisation of caring per se, that is, a conceptualisation of caring that was interpreted as an earlier described universal experience of caring in gen-eral, regardless of population. The analysis in Paper II indicated that Swedish RNs’ experiences of caring for patients with an IDD in a home health care set-ting could be understood from three overarching categories. An overview of the findings is presented in table 2.

RNs experienced that continuity and trust were vital for the care of this pa-tient group, as reflected in the LOAs “Based on long-term relationship (A*)” and “Rest its foundation on trust (B)”. RNs stressed the importance of creat-ing a trustcreat-ing relationship also with relevant others, as reflected in the LOAs “Include relevant others to offer quality of care (E)”, since relevant others of-ten knew the patient well (Paper I). However, the current work structure was perceived as counteracting RN’s attempts to build these relationships, as mir-rored in the category “Nursing held hostage in the context of care”. The struc-ture of the RNs’ everyday work led to experiences of a fragmented care deliv-ery and a day filled with putting out fires. The RNs therefore perceived that the context in which the care was delivered resulted in inefficient and incom-plete work (Paper II). As a result of not attending the service and group homes on a regular basis, most of the RNs felt overly reliant on the support staffs’ descriptions of and information about the patients. However, this was not a

Tab le 2. An ove ra ll u nde rs ta nd ing o f r eg is te red nu rs es ’ ex pe ri ences a nd pe rc ep tio ns o f nu rs ing a nd ca ri ng fo r p at ients wi th i nte lle ctu al a nd dev el op me nt al di sa bil itie s Li ne s o f Arg um ent Synt he si s ( Pa pe r I ) Ove ra rc hi ng c at eg ori es (Pa pe r II ) Ba sed o n lo ng -te rm r el at io ns hi p (A) * Res t i ts fo und at io n on t ru st (B) Inc lu de re lev ant othe rs to o ffer q ua lity of c ar e (E) Inte r-pro fe ss io nal c ol la bo ra tio n ( L) N ur si ng he ld ho st ag e in t he co nte xt of c ar e Go bey ond ve rba l c om mu ni ca tio n a lo ne (C )* Ra is e the ba r i n nu rs ing fo r thi s p ati ent g ro up (G) * Ev id ence ba sed p ra cti ce (I ) C ar e dep end ent on intu iti on a nd p ro ven e xp er ien ce Be f or w ar d pl an ni ng (D) Wo rk a ga ins t neg at ive a tti tu des a nd al ien ati on (F )* Ackno w le dge the p er so n be hi nd the la be l o f d is ab ili ty (H ) Ent ai ls a dv oc ac y and s af e gu ar di ng (M ) Under st and the c omp le xi ty of th is p at ient g ro up (N )* C ontend ing fo r the p at ien ts ’ r ig ht to a de qu ate ca re Twel ve ou t o f f ou rteen LO As o f R N s’ e xp er ien ces o f nu rs ing fo r p at ients w ith ID D (P ap er I) we re int er pr eted to a ls o r ef lec t the th ree cat eg ori es o f RN s’ p er cep tio ns o f c ar in g f or th is p ati en t g ro up in a ho me hea lth ca re co nte xt (P ap er II ). T wo LO As we re no t p ar t o f th e R N s’ p er cep tio ns in p ap er II ; K no wl edg e a nd sk ill s bey ond the di ag no si s ( K ), and Ta ki ng u np red ic ta bl e si tu at io ns into a cc ou nt (J)* . *= LO A s su gg es ted to ref lec t a u ni qu e co nc ep tu al is at io n o f R N s’ e xp er ie nc es o f nu rs ing p at ients wi th IDD .

big issue for most of the time since the presence of the support staff resulted in safe and secure patients (Paper II). Collaborating in inter-professional teams was experienced as an important tool for ensuring a structured and organised care, as reflected in the LOAs “Inter-professional collaboration (L)” (Paper I). It was perceived as necessary and beneficial for the patient’s care and was also a way for RNs to perceive their care delivery as less fragmented (Paper II). Among those RNs with a specialist IDD nursing education, there was a re-peated experience of needing to engage in educating, informing and teaching colleagues and relevant others about the care and needs of the patients, as re-flected in the LOAs “Raise the bar in nursing for this patient group (G*)”. There was a general need to raise the level of competence and knowledge about IDD on both an organisational and an individual level. Those RNs not having a specialist IDD nursing education stressed the lack of adequate knowledge in pre-registration education about IDD (Paper I). The RNs experi-enced that caring for patients with IDD had to be based on evidence-based practices, as reflected in the LOAs “Evidence based practice (I)”, especially when caring for patients with challenging behaviour (Paper I). However, the RNs could also perceive a lack of evidence-based practices and felt that they had to manage care on their own, and simply hoping that their strategies ap-plied in care would work out for the best, as mirrored in the category “care dependant on intuition and proven experience” (Paper II). RNs suggested that a specialisation is needed, particularly as caring for those with IDD is per-ceived as highly complex (Paper II). Theoretical knowledge about IDD was not always sufficient. Sometimes the RNs needed to go beyond this type of knowledge through intuitive awareness and proven experience. This could mean to intuitively know what lines not to cross in the care of the patients. RNs stated that they also needed practice situations in order to develop such intuitive awareness. It could be perceived as hard for the RNs trying to reach out while at the same time not intruding. The RNs had to use their creativity and adapt and adjust to the patients to deliver the care they were meant to give. Caring for patients with IDD was perceived as always needing to be on the patient’s terms (Paper II). Communicating with patients with IDD, of whom many are without verbal language, was described as a big challenge for the RNs, as reflected in the LOAs “Go beyond verbal communication alone (C*)”. The RNs experienced nonverbal communication as a complex skill and often experienced that they lacked the necessary knowledge for how best to do

this (Paper I). RNs raised concerns about not knowing how the patient felt about the care delivered, resulting in fear that they would almost abuse the pa-tient (Paper II). Sometimes very simple methods could facilitate care. For ex-ample, preparing the patient by repeating information a couple of days in ad-vance and showing pictures or videos, but in the majority of cases, this was not common knowledge for the RNs. Sometimes, RNs knew that augmenta-tive and alternaaugmenta-tive communication [AAC] existed, but they did not use these methods (Paper II).

RNs experienced a constant need to yell and fight for the patients’ right to ad-equate care, as reflected in the LOAs “Entails advocacy and safeguarding (M)” (Paper I) as well as in the category “Contending for the patients’ right to adequate care” (Paper II). They could experience negative attitudes towards this patient group. They experienced that they needed to actively engage in working against stigma to counteract unequal and poorly delivered care, as reflected in the LOAs “Work against negative attitudes and alienation (F*)” (Paper I). RNs also perceived that the patients with IDD were not allowed a voice of their own, treated like small children and often paternalised, hence, becoming an invisible patient group. Psychiatric problems were perceived as not being taken as seriously as physical problems, and as a result, the patients were not offered adequate psychiatric care (Paper II). Therefore, seeing the whole patient was an important part of caring, as reflected in the LOAs “Acknowledge the person behind the label of disabilities (H)”. It was experi-enced as a necessity in incorporating a person-centred care, focusing on abili-ties instead of disabiliabili-ties (Paper I). There was also awareness that the patients both felt alienated and different from their peers without IDD. Hence, the RNs described that it was vital to avoid singling them out by treating them too differently (Paper II). Caring for patients with IDD could be experienced as more complex than caring for other patients, as reflected in the LOAs “Under-stand the complexity of this patient group (N*)” (Paper I). There was a need to let the patients set the pace for care, that is, ‘to allow it to take time’. When care organisations did not support patients’ needs for longer appointments, it restricted RNs’ abilities to deliver safe and optimal care (Paper I). Caring was experienced as needing to have a lifespan perspective, as reflected in the LOAs “Be forward planning (D)”. Offering the patients a relevant environment and support in retirement, loss and bereavement was experienced as important (Paper I). RNs pointed out that the elderly in particular needed to be offered

nursing competence in the form of care rather than pedagogical competence.

RNs implied that the context of care had not kept up with developments in society or the statistics reflecting that this group of patients are reaching a much higher age than ever before (Paper II).

The LOAs “Knowledge and skills beyond the diagnosis (K)” and “Taking unpredictable situations into account (J*)” (Paper I) reflected how the RNs experienced a lack of knowledge and skills relating to IDD, but also a lack of knowledge about physical ill health in general. They experienced it as extra challenging when physical ill health became part of the equation. Lacking knowledge could result in an experience of ill health being under- or over-diagnosed or that the care did not meet the patient’s actual needs. Furthermore, RNs experienced a need to be on the alert and prepared for volatile, unpredictable situations when patients displayed behaviour that challenged. They experienced that they had to be prepared to control cha-os and turmoil to be able to deliver safe care in all types of environments, whether high risk or low risk. RNs could also experience negative thoughts about the patients. In those cases, RNs experienced a need to emotionally distance oneself and ‘close off’. RNs also reflected experiences of a need to focus on personal protection and safety and r a i s e d fears that violence and abnormality could become the norm when caring for this group of patients (Paper I).

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The purpose of research is to generate new knowledge, new insights and in-creased understanding, but there is always a risk of sources of error and inter-pretations that can lead to too far-reaching conclusions. Several methodologi-cal considerations need to be addressed to evaluate the strengths and weakness of this thesis. For Paper I, the legitimacy, that is the data’s genuineness needs considerations. For Paper II, the trustworthiness, i.e., the data’s credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), and au-thenticity (Guba & Lincoln, 1994) needs considerations. Accordingly, these factors will be discussed under the headings legitimacy and trustworthiness.

Legitimacy

The SPIDER (Cook et al., 2009; Lord et al., 2017) tool was useful in developing a clear and specific research question and in identifying terms suitable for the literature search. The literature search strategy was then developed in collaboration with a specialist librarian, to en-sure that the search strategy was rigorous and thorough. However, rel-evant terms may have been missed, especially concerning free text terms. The literature search was conducted in common nursing databases

(PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO) as well as in a database for

pedagog-ics (ERIC). This gave important width to cover both caring and IDD. However, there is a possibility that searches in additional databases could have generated further studies to be included in Paper I. Due to a time lapse between the search and the synthesis, a repeat search was conducted just before work on the synthesis began (November 2017) to ensure all relevant Papers were included, and that no further studies could be identi-fied.

The inclusion criteria were set in relation to the aim of the study, and the screening process ensured that the studies included all fell within these criteria. MA screened all titles, abstracts and reference lists herself, which may have restricted the inclusion of studies. The inclusion criteria were wide regarding clinical settings and qualitative methodologies, but strict concerning health care professionals, in this thesis RNs. The latter criteria were essential to make it possible to answer the question at issue. The decision to include any type of qualitative design was based on the assumption that regardless of individual methodology, qualitative designs overall derive from the same epistemological and ontological perspectives. Brookfield et al. (2019) states that “the exten-sion of qualitative synthesis across multiple methodologies has not under-mined the position of meta-ethnography within the field” (p. 4).

The extraction and quality appraisal protocol helped to focus the data extrac-tion. MA extracted the data herself, however, using a detailed protocol to en-sure that no data was missed. By using protocols that compelled the reviewers to motivate their judgement regarding the critical appraisal, and by using four independent reviewers, the validity regarding the quality appraisal process was strengthened. There is currently a discussion about i) the importance of quality appraisal per se and ii) whether eligible studies assessed as methodologically weak should remain in the synthesis (Campbell et al., 2011). One of the chal-lenges is that there is very limited agreement about what determines a “good” primary qualitative study (Dixon-Woods et al, 2007; Toye et al, 2013). In-deed, a significant number of qualitative evidence-synthesis [QES] reviewers choose not to appraise studies (Campbell et al., 2011; Hannes & Macaitis, 2011). However, although quality appraisal might highlight methodological

flaws, it does not necessarily help the reviewer to appraise the usefulness of findings for the purpose of QES. It could be argued that good studies are ex-cluded if our primary concern is methodology rather than conceptual insight, which are not considered in quality appraisal programmes such as Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [CASP] (2018), GRADE-CERQual (2020), Con-Qual (2018) and so on. The experience from the quality appraisal in the Paper I study following the conceptual model for quality appraisal by Toye et al. (2013) showed that a study could be deemed fatally flawed methodologi-cally, but could still provide interesting and rich insights conceptually.

Therefore, such Papers were included even when the methodological quali-ty was not optimal.

A meta-ethnography will inevitably be partially a product of the researcher. The researcher must also consider the audience in relation to the synthesis; the readers are also comparing their own worldview to that revealed by research (Noblit & Hare, 1988). During the analysis, there was constant shifting be-tween the whole and the details, from the single study’s idiomatic translations and the LOA synthesis, in order to be close to the data and giving a fair trans-lation (Polit & Beck, 2017).The majority of the LOAs were well represented throughout the 18 included studies regardless of their quality assessment; hence, the suggestion was that the synthesis that reflected how general and specialist RNs could experience the care for patients with IDD can be general-ised across a European health care context.

Trustworthiness

In qualitative designs (Paper II), trustworthiness can be evaluated in terms of credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), and authenticity (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Credibility can be viewed in the light of whether the results present a truthful description of participants’ experiences and experiences (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The setting and context have been thoroughly described to facilitate the understanding (Lakeman, 2013). Only three male RNs were recruited, which could be viewed as a limitation. However, women are in the majority in nurs-ing in Sweden, as only about 11% of RNs are male (Rudman et al., 2010), thus limiting the possibility of recruiting male RNs. Although being only three males, the twenty RNs varied in gender, age, education and work experience, which should be regarded as sufficient to ensure variation in perceiving the same phenomena (Marton, 1981). An interview guide was developed to help the researcher focus on the topic (Patton, 2015). Four pilot interviews were conducted in order to control the suitability of the research question and re-vise it, and to gain experience in an interview situation. These pilot interviews were not included in the analysis and the final report. In spite of this, there was a potential risk that data collection was guided by the author’s pre-understanding in the topic of research, and may have resulted in the author posing leading questions or missing following up ques. The interviews took