B

ECAUSE THEY

L

OVE

Y

OU

A

N ANALYSIS OF THE@BVG_K

AMPAGNET

WITTERF

EEDLuisa E. Falkenstein

1

styear master’s thesis

Malmö University

K3 – School of Arts and Communication

Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media

and the Creative Industries (Master of Arts, 2-year)

Supervisor: Emil Stjernholm

Examiner: Pille Pruulman-Vengerfeldt

Date of examination: November 4

th, 2019

Abstract:

In this case study, I focus on Berlin’s BVG (public transport provider), who overcame a severe online firestorm in reaction to their marketing campaign centered around the slogan “weil wir dich lieben “ (because we love you) in January 2015. Through a content analysis of the BVG’s Twitter feed in January 2015 (during the firestorm) and January 2016 (after the firestorm), I aim to determine how crisis communication strategies were employed by the BVG and what role humor played in their communication on Twitter. My approach to this topic is very much rooted in a rhetorical/ text-based theory of both crisis communication and humor, focusing exclusively on tweets authored by the BVG and analyzing each tweet’s content regardless of its context.

My results indicate that humor is employed in the majority of the BVG’s tweets both during the crisis and after, a practice that may have helped reduce the perceived severity of the initial cause for the online firestorm. The use of humor in direct response to the crisis is more cautious than after the crisis, showing that despite its newfound jovial image, the BVG in no way underestimated the severity of the crisis situation. Furthermore, the BVG’s Twitter com-munication is shown to be highly interactive and conducted in a conversational tone. This indicates that the BVG uses their Twitter account to engage with their customers in a friendly and open conversation, building stronger relationships and ultimately creating a network of support, which can be useful both for marketing purposes and as a deterrent for future com-munication crises.

This study can be seen as a small addition to crisis communication and humor research as well as research into online marketing. For future research the framework and methodology may need to be expanded to more widely assess how humor could be employed to overcome negativity online and especially face organizational crises such as online firestorms.

Keywords: Crisis communication, Twitter, Humor, Online Marketing Communication,

Conversational human voice, Content analysis, Online Firestorm

T

ABLE OFC

ONTENTS1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

2. BACKGROUND ... 3

COMMUNICATION IN THE TIME OF TWITTER ... 3

ONLINE FIRESTORMS: ONLINE OUTRAGE AND NEGATIVE EWOM ... 5

THE BVG AND #WEILWIRDICHLIEBEN ... 7

3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 11

MARKETING IN A NETWORK SOCIETY AND LISTENING TO THE GROUNDSWELL ... 11

CRISIS COMMUNICATION AND CRISIS MANAGEMENT ... 14

HUMOR ... 15

4. PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 16

HUMOR ONLINE... 16

HUMOR IN ADVERTISING AND ONLINE MARKETING ... 17

HUMOR IN CRISIS COMMUNICATION ... 18

WEBCARE AND COMPLAINT MANAGEMENT... 19

5. FRAMEWORK FOR CASE STUDY ... 20

6. RESEARCH DESIGN ... 21

METHOD ... 22

SAMPLE ... 23

CODING ... 24

PILOT AND REJECTED CODING CATEGORIES ... 27

EXAMPLES OF TWEETS ... 27

LIMITATIONS ... 29

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 30

7. KEY RESULTS ... 31

TWITTER ACTIVITY... 31

CONTENT,HUMOR AND TONE ... 33

8. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ... 34

@BVG_KAMPAGNE IN CRISIS ... 34

@BVG_KAMPAGNE AS A TWITTER PARAGON ... 36

9. CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK: MAKE ‘EM LAUGH ... 38

L

IST OFF

IGURESFIGURE 1LAYERS OF TWITTER COMMUNICATION, ACCORDING TO BRUNS &MOE (2013) ... 4

FIGURE 2BSRPOSTER,1999-2000 (“BSRMARKETING,”2019)... 8

FIGURE 3BVGPOSTER "PUG",2016(“BVG:UNTERNEHMEN,”2019) ... 9

FIGURE 4 TWEETS IN RESPONSE TO #WEILWIRDICHLIEBEN (JANUARY 13TH 2015) ... 10

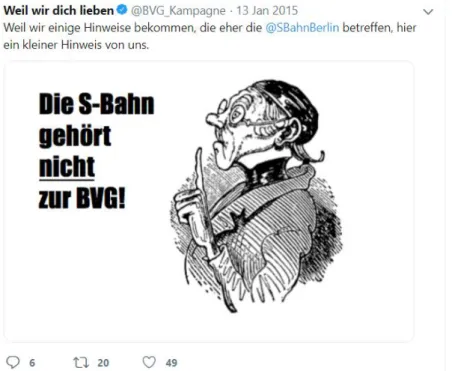

FIGURE 5EXAMPLE TWEET 150113_23"HUMOR REFERENCE" ... 28

FIGURE 6EXAMPLE TWEETS 150114_07 AND 150114_08"HUMOR REPLIES" ... 29

FIGURE 7EXAMPLE TWEETS 150113_06 AND 150113_07"NO HUMOR" ... 29

FIGURE 8TWITTER ACTIVITY PER DAY COMPARED ... 31

FIGURE 9 ALLOCATION OF TYPES OF TWEETS PER YEAR ... 32

FIGURE 10HUMOR DEVICES USED PER YEAR ... 33

L

IST OFT

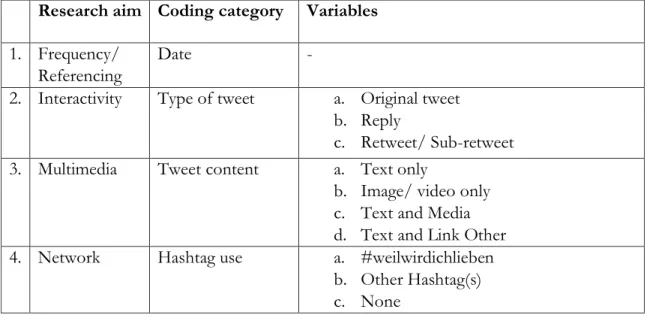

ABLES TABLE 1HUMOR DEVICES IN ADVERTISING ... 17TABLE 2CODING CATEGORIES 1-4 ... 24

TABLE 3CODING CATEGORIES 5-7 ... 25

TABLE 4REJECTED CODING CATEGORIES ... 27

TABLE 5OVERVIEW OF RESULTS... 32

TABLE 6TWEET CONTENT PER YEAR ... 34

A

PPENDICESCODEBOOK

SPREADSHEET EXCERPTS

1

1. I

NTRODUCTIONIn January 2015 the BVG (Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe), Berlin’s public transport provider, who operate the German capital’s busses, tramlines and subways (U-Bahn) and ferries, launched an online and offline marketing campaign, centered around the slogan and the hashtag “Weil wir dich lieben” and #weilwirdichlieben (engl.: because we love you). As part of the campaign, their social media followers were asked to share happy and positive anec-dotes pertaining to Berlin’s public transport. In the following days the BVG found itself facing a so-called online firestorm, with users criticizing and attacking the BVG for a variety of real or perceived failures and infractions (“Die Hintergründe der BVG- Kampagne ‘Weil wir dich lieben,’” 2017), essentially hijacking the positive hashtag and campaign intentions. The offline press quickly got wind of this, and the firestorm spilled over into mainstream media, presenting the BVG with a major communication crisis (Briest, 2015).

These sorts of crises are becoming fairly common as more and more companies attempt to use social media to attract new customers and to communicate with their existing network (Hill, 2012). The consequences of an online firestorm can be severe, with the negative elec-tronic word-of-mouth (neWOM) affecting customer or stakeholder behavior offline (Pfeffer, Zorbach, & Carley, 2014). Various companies, from fast food chain restaurant McDonald’s in 2012 (Hill, 2012) to online bank ING-DiBa in 2013 (Stegbauer, 2018), have experienced similar backlashes and crises on social media in reaction to attempts at connecting with customers online. It has therefore become of interest to both marketing professionals and researchers to develop strategies that can help either prevent online firestorms or give cor-porations the tools to overcome them (Steinke, 2014).

What sets the BVG’s campaign apart from the failed campaigns, however, is that within a few days the organization managed to overcome the wave of negativity and in fact garnered praise both on- and offline for its humorous way of dealing with the complaints. The cam-paign later won numerous awards and is now considered a massive success, with the BVG being lauded for their innovative and highly effective online communication (“BVG erfolgreich bei Social Media,” 2017). The press coverage and conversations surrounding the initial online firestorm and the later course of the campaign noticeably focus on one specific aspect of the BVG’s communication: Humor is always cited as the means with which the BVG rose above the storm of negativity (“Die Hintergründe der BVG- Kampagne ‘Weil wir dich lieben,’” 2017).

2 I personally, began following the campaign not long after its inception, partly out of personal interest and curiosity and partly as part of a university course on online firestorms. To me, as a Millennial, a digital native and an avid Twitter user, contemporary forms of corporate communication on social media, be it for marketing purposes or crisis communication, are endlessly fascinating. And the success of the BVG’s campaign in spite of (or maybe because of) its less than ideal beginnings presents an interesting subject for a case study.

Such a study could be a useful contribution to research of both marketing communication and crisis communication. As humor appears to be a relatively unconventional tool for both a deeper insight into its uses might be relevant for marketers trying to develop strategies to overcome or prevent online firestorms. However, an inquiry into humor use, especially when faced with online negativity, might in fact proof even more far reaching: In times when social media has become embedded into many aspects of everyday life phenomena like online bul-lying and harassment have also sadly emerged. If research into humor as a tool of building a strong online network and overcoming adversary, yields useful strategies for marketers, sim-ilar strategies might also be developed to combat other phenomena associated with negativity online.

For this master’s thesis I thus chose to take a deeper look at the BVG’s Twitter communi-cation during and immediately following the online firestorm in January 2015 as well as the company’s Twitter communication in January 2016, when the campaign had turned into a success. To better understand the organization’s communication practices, I conducted a content analysis of the @BVG_Kampagne’s Twitter feed to ascertain:

RQ1: How did the @BVG_Kampagne’s Twitter communication differ between Jan-uary 2015 and JanJan-uary 2016?

RQ2: How was humor a part of the BVG’s crisis communication strategy and their general marketing communication?

To present as comprehensive an account as possible of my research process, I will in the first part of my thesis (chapters 2-5) discuss the context for my study as well as the relevant the-oretical considerations and previous literature surrounding the topic, which helped to de-velop my research questions. In the second part of this thesis (chapters 6-9) I will explicate my research process and present my findings.

3

2. B

ACKGROUNDTo begin this thesis, I will provide a more detailed context for my research. Firstly, I will give a brief overview of Twitter practices and communication1, followed by a brief discussion of

the phenomenon of an online firestorm along with two examples of negative outcomes will be introduced. Secondly, I will introduce the BVG and briefly elaborate on the 2015 market-ing campaign and subsequent online firestorm. The presentation of specific online firestorms in this chapter largely relies on non-academic sources, such as (online) newspaper articles, marketing newsletters, and a podcast on online communication and should be seen as more of a narrative contextualization for the study rather than an academic examination.

COMMUNICATION IN THE TIME OF TWITTER

Twitter is a so-called microblogging platform, founded in 2006. The term microblogging sug-gests that, like on a blog, updates appear in reverse chronological order, with the most current on top, whilst each post (called a tweet) is relatively short, being limited to only 140 characters in length (Weller, Bruns, Burgess, Mahrt, & Puschmann, 2013). Initially created to serve as a place to post short status updates about everyday life, Twitter has over the years developed into a complex communication hub. The platform can be accessed through mobile apps on various devices or simply through the website Twitter.com, which also allows internet users to see the interface without having to log in. However, in order to post, interact or receive notifications of activity, one must create a Twitter-account (Bruns & Moe, 2013; Halavais, 2013).

Bruns and Moe (2013) as well as Halavais (2013) provide a comprehensive overview of the technical functions of Twitter as well as an understanding of the layers of Twitter communi-cation (see Fig. 1).

1 Twitter itself has received a fair share of academic attention in recent years and has developed into

an increasingly complex platform. Due to the scope of this thesis, I will not be able to provide an in-depth rundown of every feature or practice and will instead focus only on the aspects which are most relevant for the later analysis and discussion.

4

Figure 1 Layers of Twitter communication, according to Bruns & Moe (2013)

Twitter users can follow accounts to receive updates on those accounts’ activities. This allows users to curate highly personal feeds of activity and information. The relationship between follower and followed is not reciprocal by default, as “a user may follow any other user […] without requiring the other user to follow back in return” (Bruns & Moe, 2013, p. 16). By encouraging other users to follow one’s own account each user can also build their own audience. These follower audiences form the meso-layer of Twitter communications: Fol-lowers are the default audience for every tweet posted (although the tweet is also visible for any other user) and are generally a gradually grown and relatively stable group (Halavais, 2013).

Tweets contain a maximum of 140 characters and can also include links to external sites or media files which are uploaded to Twitter. The platform also enables retweeting (sharing an-other user’s tweet verbatim) and sub-retweeting (sharing anan-other user’s tweet with an added commentary).

In addition, tweets can be explicitly addressed to one or more specific accounts by adding those accounts’ Twitter-handles (denoted by an @-symbol, e. g. @BVG_Kampagne) to the beginning of the tweet. These types of tweets are usually considered replies (or @-replies); however, they can in fact also be used as an @-mention, without addressing a specific previ-ous tweet (Halavais, 2013). In addition to tweeting and replying to tweets, users further have

5 the ability to send direct messages to other users. These practices form the micro-layer of Twitter communication: they are used for immediate interpersonal exchanges between indi-viduals or within a small group. Nevertheless, @-replies are also visible to any other Twitter user regardless of follower status (Bruns & Moe, 2013).

The macro layer of Twitter communication is formed by interactions between users, that may reach beyond their individual follower networks. In many cases such interactions will be centered around a so-called hashtag (a topic which is denoted by a #-symbol, e. g. #weilwirdichlieben) (Bruns & Moe, 2013). Conversations surrounding hashtags can assem-ble a large amount of previously unconnected users in a relatively short amount of time and are according to Bruns & Moe (2013) the most visible Twitter phenomenon, however the audiences surrounding a hashtag often disperse rather quickly.

Twitter activities are not always restricted to only one of the previously mentioned layers: A reply may include a hashtag and therefore be both part of an interpersonal exchange and a larger public discourse; and a tweet that receives a lot of retweets might quickly leave the user’s original follower network and be noticed by a much wider audience.

ONLINE FIRESTORMS: ONLINE OUTRAGE AND NEGATIVE EWOM

Pfeffer et al. (2014) define an online firestorm as “the sudden discharge of large quantities of messages containing negative WOM and complaint behavior against a person, company, or group in social media networks. In these messages, intense indignation is often expressed, without pointing to an actual specific criticism” (Pfeffer et al., 2014, p. 118). The dynamics of an online firestorm can be likened to the circulation of rumors, in that both are circulated mainly via WOM (word-of-mouth) and with a lack of evidence sourcing. However, the level of aggression of a firestorm is much higher than that of a rumor and the messages spread in an online firestorm are almost always based on the sender’s personal opinion. Whilst rumors are usually unconfirmed, an online firestorm can be caused by both an unconfirmed and a confirmed event (Pfeffer et al., 2014).

In German the term Shitstorm has been established in both academia and everyday discourse to describe the same phenomenon. According to Stegbauer (2018) during such an event so-cietal regulations and rules of conduct are temporarily turned off – and attempts to moderate the conversation can easily be seen as attempts to suppress – further eliciting aggression. Online firestorms can thus be understood in terms of cultural opposition – the (less fortu-nate, but more righteous) masses fighting against a perceived elite (a company or a person of

6 interest), which make them very difficult for organizations to handle without appearing de-tached or dismissive (Stegbauer, 2018). There are two main characteristics to an online fire-storm: Firstly, the negative WOM is centered around or directed towards a specific individual or organization. Secondly, an online firestorm takes place over a relatively short period of time.

The following examples illustrate how organizations and individuals faced with online fire-storms often have to deal with negative consequences, for failing to properly respond to the digital outcry.

MCDONALD’S AND THE #MCDSTORIES “BASHTAG“

The BVG aren’t the first corporation to find their positive campaign hijacked and turned into an online firestorm. In 2012 McDonald’s intended to draw attention to its new adver-tising campaign, which focused on the farmers working as part of the fast-food restaurant’s supply chain, by promoting the hashtags #MeetTheFarmers and #McDstories on Twitter. Within a short amount of time #McDstories was used by users to share negative experiences, relating for example to lack of hygiene in restaurants, food poisoning or the overall unhealth-iness of McDonald’s products (Sherman, 2012).

McDonald’s reacted by immediately deleting the hashtag and stopping the promotion of the trend, which did limit the spread of further negativity. However, by this point media outlets had noticed the online firestorm and began reporting on it, with one contributor to Forbes.com dubbing the hashtag a ‘bashtag’ (Hill, 2012). Ultimately McDonald’s faced ridi-cule both for losing control of their hashtag and for handling the negative response badly and later attempting to downplay the magnitude of negative tweets (Sherman, 2012). The #McDstories firestorm only lasted a few hours, due to the company’s quick reaction in deleting the tweet and having the hashtag removed from Twitter trending topics, however it did do some reputational damage, mainly due to the mainstream media coverage of the inci-dent (“McDonald’s #McDStories Twitter Campaign Fails,” 2012). This so called “spillo-ver”(Johnen, Jungblut, & Ziegele, 2018, p. 3141) from Twitter, or other social media, into mainstream media (both on- and offline) can severely amplify the negative outcomes of an online firestorm.

JUSTINE SACCO AND #HASJUSTINELANDEDYET

Despite this thesis’ focus on corporate online communication, it should be noted that the target of an online firestorm is not always a company or organization facing dissatisfied

7 customers or having to excuse inappropriate behavior. As social media makes privates lives more public than ever before, individuals with no prior claim to fame can also find them-selves at the center of international social media attention. One such example is Justine Sacco. In December 2013, Sacco, a PR-executive, was flying from New York City to Cape Town, where her family lived. During a stop-over in London, she tweeted: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” (Ronson, 2015) to her modest following of around 170 Twitter followers. Sacco had no internet connection during her 11-hour flight and there-fore did not know, that her tweet had garnered the attention and the outrage of Twitter-users world-wide, who criticized Sacco for the ignorance and racism displayed in her tweet. By the time she landed, the Hashtag #HasJustineLandedYet was trending world-wide with more than 10.000 tweets, offline media was reporting on her story and, as a direct consequence of her tweet and the online firestorm that followed, she had been fired from her job (Hill, 2013; Ronson, 2015).

Justine Sacco’s case exemplifies what can happen if an online firestorm is not addressed at all by the entity at which it is targeted – Sacco’s inability to quickly respond to the online outrage, either by apologizing, deleting the tweet or otherwise engaging, ultimately meant that by the time she was back online it was too late for damage control and she faced dire consequences. Furthermore, despite Sacco’s relatively small initial following on Twitter, her tweet ended up being seen by thousands of users, which illustrates the unpredictability of information spreading during an online firestorm.

THE BVG AND #WEILWIRDICHLIEBEN

The Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) is a service provider under public law, operating Ber-lin’s busses, tramlines, U-Bahn subways and ferries. The company employs more than 14.000 employees and, according to their website, transports more than 1 billion passengers per year (“BVG: Unternehmen,” 2019). Facing decreasing numbers of ticket subscriptions and an overall low approval and customer satisfaction rating, the BVG launched a new marketing campaign in January 2015 which is still ongoing until this day. This campaign’s overall tone and style was inspired by previous campaigns by the Berliner Stadtreinigung, or BSR (the service provider responsible for Berlin’s waste management) which had featured humorous slogans and puns such as “we kehr for you” – a play on the German verb “kehren”, meaning to sweep and the English word care (see Fig. 1), since 1999 (“Die Hintergründe der BVG- Kampagne ‘Weil wir dich lieben,’” 2017).

8

Figure 2 BSR Poster, 1999-2000 2 (“BSR Marketing,” 2019)

For their 2015 campaign the BVG instigated an overhaul of both its offline advertising, in-troducing new posters and brochures, and its online communications, including new counts on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. There had previously been social media ac-counts, e. g. the @BVG_Bus3 account, which informed commuters about delays or

road-work along bus routes. However, there had not truly been a social media account with the sole purpose of reaching out to customers and involving them in a conversation.

The campaign was centered around the Slogan “Weil wir dich lieben” (Because we love you) and, much like the BSR’s advertising, used puns and a humorous tone. One example of this can be seen in Fig. 2; the 2016 BVG poster announces: “Du musst deine Möpse nicht ver-stecken” (You don’t have to hide your pugs) next to an image of a pug in a shark costume. “pugs” is a German euphemism for female breasts, however, as the subtitle makes clear: the poster is merely pointing out that small pets do not require an extra ticket when travelling on BVG services.

2 Translation Poster: We sweep for you. [BSR] We’ll restore order.

3 The accounts @BVG_Bus, @BVG_Tram and @BVG_UBahn had been active on Twitter since

9

Figure 3 BVG Poster "Pug", 20164 (“BVG: Unternehmen,” 2019)

On January 12th, 2015 the official Twitter account @BVG_Kampagne, tweeted for the first

time, announcing the launch of the new campaign online and introducing the new hashtag #weilwirdichlieben (#becauseweloveyou). Within less than a day the account and the BVG at large experienced an outpouring of negativity (see Fig. 3): from complaints about delayed trains, high ticket prices and cancelled busses, to general insults. While a certain pushback from the public had been expected the amount of negative attention their inaugural tweet had attracted presented a major PR crisis and challenge for the BVG, especially as the fire-storm spilled over into the mainstream media almost immediately (“Die Hintergründe der BVG- Kampagne ‘Weil wir dich lieben,’” 2017).

4 Translation poster: You don’t have to hide your pugs. Small pets travel free of charge.

10

Figure 4 tweets in response to #weilwirdichlieben (January 13th, 2015)56

In response to the high number of negative tweets, the @BVG_Kampagne account began engaging with complainants on Twitter. Without taking themselves too seriously, they started replying to tweets in a humorous way, often making fun of themselves. Where the campaign had initially been regarded with glee and schadenfreude by social media users and traditional media outlets alike, they now garnered praise for their friendly spirit and typically Berlin hu-mor. By spring 2015, the campaign was receiving positive press coverage (Köhler, 2018; Rehn, 2015).

Another major turning point for the campaign occurred towards the end of 2015: on De-cember 11th, almost exactly eleven months after their campaign had first launched, the official

BVG YouTube channel premiered a video, featuring rapper Kazim Akboga entitled “Is mir egal” (I don’t care). The video responded to many of the prevalent criticisms voiced during and following the online firestorm. It featured Akboga, dressed as a BVG employee, pointing out a variety of infractions and disturbances that had been noticed by customers and voiced as complaints in reaction to the Hashtag #weilwirdichlieben. Theses disturbances to com-muter transportation, including loud music playing, people eating or even cooking, people moving large pieces of furniture, members of sub-cultures (goths, leather daddies, transves-tites), people transporting large pets (in the video: a horse) on the underground, are acknowl-edged by Akboga and ultimately dismissed by him repeatedly saying “Is mir egal, egal” (“I don’t care, whatever”). The only thing the video’s protagonist does appear to care about: the validity of every traveler’s ticket. The video concluded by Akboga saying “Wir euch lieben – ist euch egal, egal” (We love you – you don’t care, whatever) and text displayed on screen reading: “Nur wir lieben dich so wie du bist” (Only we love you the way you are). The video, 5 Translation tweet 1: Your machines have been stamping made -up dates unto tickets for months e.

g. April 57t h. #becauseweloveyou

6 Translation tweet 2: Getting kicked out of the bus because the card readers for electronic tickets

11 produced by German advertising agency Jung von Matt, was well received and at the time of this study the video has more than 12 million views on the BVG’s YouTube channel and has been reposted on various other channels. In the years since the beginning of the campaign a number of equally successful videos have been posted, many of which share the humorous tone and blasé attitude of “Is mir egal”.

In addition to the campaign’s success in terms of advertising awards and views and clicks online, the campaign is credited with having a tangible offline impact: ticket sales have been rising consistently and instances of both vandalism and attacks on BVG employees have decreased significantly. Overall, the BVG’s image, not only as a service provider, but also as an employer has drastically improved (“Die Hintergründe der BVG- Kampagne ‘Weil wir dich lieben,’” 2017). This huge success stands in stark contrast to the bleak situation of Jus-tine Sacco after her brush with Twitter notoriety and shows that the attention generated by an online firestorm can be used to further an organization’s or company’s success in online marketing, when handled correctly.

3. C

ONCEPTUALF

RAMEWORKNow that the context for this study has been established, this chapter will introduce the underlying theories of this research and more thoroughly examine how the subject of (hu-morous) online communication in the face of an empowered audience and an online fire-storm might be approached in this study. As a marketing campaign, the subject matter is clearly rooted in the field of marketing communication, specifically online communication, which can be understood using Jan van Dijk’s theory of a network society. Furthermore, due to the volatile situation of an online firestorm, crisis communication concepts will be con-sulted to better comprehend the BVG’s communication strategies. Additionally, as I am spe-cifically interested in the BVG’s use of humor, predominant theories of humor will briefly be introduced in this chapter.

MARKETING IN A NETWORK SOCIETY AND LISTENING TO THE GROUNDSWELL

Both the phenomenon of online firestorms itself, as well as the new ways of marketing com-munications from which it arises, can be understood, from a comcom-munications research per-spective, as challenges of marketers in a network society. Marketing – “a set of processes for creating, communicating, and delivering value to customers and for managing customer re-lationships” (Kolb, 2008, p. 8), has adapted new ways of connecting to and communicating with an ever expanding and increasingly confident audience in a digital arena.

12 To describe the way that information and communication technology have become interwo-ven with most aspects of everyday human life, Jan van Dijk coined the term “network soci-ety” in 1991. Network society describes “a social formation with an infrastructure of social and media networks enabling its prime mode of organization on all levels” (van Dijk, 2006, p. 20). Supported by the so-called “new media” (van Dijk, 2006, p. 9) both mass communi-cation and private communicommuni-cation increasingly take place in an online setting. In fact, van Dijk theorizes that the development of a network society also leads to the inception of addi-tional types of communication, situated between interpersonal, private communication and mass communication. Basically, through the increasing interconnectedness of the new media, messages addressed to one individual recipient might still be transmitted in plain view of a larger network, blurring the lines of private and mass communication in a way that was pre-viously impossible. Networks, it should be noted, are according to van Dijk, in no way a new phenomenon. Human networks can be traced back all the way to the earliest beginnings of human civilizations. But the contemporary media landscape in a progressively digitalized world enables new forms of connection and information sharing, creating digital networks, which permeate everyday life in the Western world (Jan van Dijk, 2006).

Whilst van Dijk’s concept of networks and new media – “media which are both integrated and interactive and also use digital code at the turn of the 20th and 21st century” (van Dijk,

2006, p. 9), predates most of what we today have come to think of as social media – “Inter-net-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and the exchange of User Generated Content” (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2011, p. 254), it nonetheless identifies components most relevant for social media marketing: networks, multimedia integration and interactivity.

Marketing relations in a network society can exist between an organization and an individual as well as between an organization and a network of individuals. As the new media allows for both highly individual communication and interaction and the creation and maintenance of online communities (a form of network), marketing communication can be targeted at individuals, entire existing networks or newly formed targeted communities (Jan van Dijk, 2006).

As the continued spread of new media in the network society opens new pathways through which organizations can reach their customers, it also opens new ways for customers to connect and communicate to one another. Li and Bernoff (2009) use the term groundswell to describe the new, empowered customers in a new media world. Where one voice, positive or negative, could easily be overlooked in the past, the Internet, with social media platforms,

13 blogs and forums has allowed for new ways of organizing and connecting, and ultimately achieving much higher visibility (Li & Bernoff, 2009).

These new ways of connecting and organizing among customers is a prerequisite for elec-tronic Word-of-Mouth. Word-of-mouth (WOM), meaning individuals willingness to share experiences and information with other individuals in their network, has long been an ob-served tool of marketing communications as it greatly influences consumer behavior and trust in organizations. Social media, with its interactive infrastructure and its inherent options for sharing, reposting, liking and commenting, opens up new ways of accessing networks and letting information spread (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2011). Thus, networks are the basis for present day social media marketing, viral marketing and content marketing (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2011).

In many ways Twitter, the object of this very study, is the quintessential new media – it is a digital platform, which allows for multimedia content to be published to an audience con-sisting not only of one’s own followers, but Twitter users at large and in fact any person with internet access. Relating back to the characteristics of Twitter communication outlined ear-lier, it becomes clear how Twitter communication enables the building and maintenance of networked relationships on every communication layer: follower networks form a stable au-dience of customers and stakeholders which continuously receive information; ties within this network can be deepened through one-on-one interactions and involvement in hashtagged conversations can increase visibility outside of one’s own network.

Building on the idea of a network society, a more contemporary understanding of the platform society has been developed, focusing on the way in which digital platforms have permeated every aspect of life, from social interaction to commerce and politics to healthcare (José van Dijk, Poell, & de Waal, 2018). As this thesis’ interest in the BVG’s marketing communication is focused on their attempts at building, repairing and nurturing network bonds through social media communication, Jan van Dijk’s concept of a network society lays a sufficient groundwork. However, this line of inquiry at least runs tangent to the deeper implications of a platform society and its challenges regarding private and public interests and values, and future research into this topic should take into consideration the role of the platform itself (in this case Twitter) to a higher degree.

So, with regard to the topic of this study, van Dijk’s theory of a network society can be used to explain the BVG’s efforts of Twitter marketing by instigating a conversation around the hashtag #weilwirdichlieben. Encouraging users to use the hashtag ultimately allowed the

14 BVG to follow the conversation of users outside of their follower-network and to interact with users participating in the conversation.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION AND CRISIS MANAGEMENT

A crisis, or more specifically an organizational crisis, can be defined as an unanticipated or unexpected occurrence, which severely threatens an organization’s values and reputation and must be addressed within a short window of time to deter further damages (Frandsen & Johansen, 2017). Coombs (2007) stresses, that crises are “unpredictable but not unexpected. Wise organizations know that crises will befall them; they just don’t know when.” (p.3) and thus highlights the importance of crisis management and crisis communication as part of any organizational structure.

Crisis management is the sum of the strategies implemented to diminish the negative conse-quences of a crisis and to prevent future crises. The main factors of crisis management are prevention and preparation, response and revision, which correspond to a three-stages model of crisis management: prevention and preparation take place during the pcrisis stage, re-sponse occurs during crisis stage and revision is conducted in the post-crisis stage, in order to then strengthen the pre-crisis strategies (Coombs, 2007).

The advances of communication technology and new media have impacted crisis manage-ment. In a network society, crises are more likely to be noticed by a wider audience, increasing the risk of negative outcomes. Coombs (2007) thus coined the term paracrisis, to describe an organizational crisis were both the initial complaints and the reactionary crisis response are communicated in plain sight of a wider network. This calls for new strategies in countering crises and an understanding of social-mediated crisis communication (Coombs, 2007; Frandsen & Johansen, 2017). Crisis communication is one of the fundamental components of crisis management. It can be defined as “a complex and dynamic configuration of com-municative processes which develop before, during, and after an event or a situation that is interpreted as a crisis” (Frandsen & Johansen, 2017, p. 148). In general, crisis communication is one branch of an organization’s communication with the public and as such, in a network society, is increasingly focused on relationships and networks (Frandsen & Johansen, 2017). Crisis communication has been approached from a variety of research angles, leading to multiple models and theories. Text-oriented and rhetorical approaches are focused on the content of communication whereas strategic and context-oriented approaches focus on the structures, context and reasons of crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, 2017).

15 Rhetorical approaches to crisis communication suggest, that a key aim of crisis communica-tion should be to control and influence the narrative of the crisis itself in order to retain or reclaim a favorable image in the eyes of stakeholders (Miller & Heath, 2004). William Benoit’s image repair theory states much the same: according to Benoit an organization’s communi-cation is always oriented toward maintaining a favorable reputation. To ensure that no lasting damage is sustained during crisis, Benoit suggests general response strategies of which one or more may be employed, should the organization’s reputation come under attack: Denial, evasion of responsibility, reducing offensiveness of the cause for attack, taking action to correct the offense and mortification. Whichever one’s of these strategies will be employed and the exact nature of the communication content may depend on contextual factors of the crisis (Benoit, 2014; Frandsen & Johansen, 2017).

Regarding crisis context, it should be noted, as in the following thesis the online firestorm encountered by the BVG will be used as an example of an organizational crisis, or paracrisis, in accordance with Coombs (2007) and Frandsen and Johansen (2017), that the threat posed to the BVG by the online firestorm was very much centered around reputational damage. The main cause for the public’s negative reaction had been smaller annoyances, as illustrated previously, and there had been no severe accidents or gross misdoing by the company, which would have necessitated different crisis management approaches to mitigate negative effects.

HUMOR

“Humor is indicated by at least one of three responses: behavioral (laughing), cognitive (appraising something as “funny”), or emotional (experiencing the positive emotion of amusement). We refer to a stimulus as humorous to the extent that it elicits greater perceptions of humor (on average)” (Warren & McGraw, 2015, p. 1).

Humor has been approached from a multitude of academic angles and therefore is defined in a variety of ways. In relation to humor other terms such as joke, comedy and laughter, have been used both to express opposition and equivalence, further muddling the concept (Gulas & Weinberger, 2006). As indicated by Warren and McGraw (2015), there are three main theories of humor: Cognitive Theory, Superiority Theory and Arousal Safety.

According to cognitive theory, humor is understood to be triggered by incongruity, i. e. a situation being resolved in a way that challenges the audience’s expectation and therefore builds on surprise. Humor can therefore be understood by analyzing the use of language devices and message content (Gulas & Weinberger, 2006; Simpson & Bousfield, 2017) and has been described as being a result of so called benign violations – “moral violations that

16 simultaneously seem benign elicit laughter and amusement in addition to disgust” (McGraw & Warren, 2010, p. 1).

Superiority Theory describes a situation as humorous where an audience can clearly establish a winner and a loser. According to superiority theory humor is usually experienced at the loser’s expense and to understand humor one must analyze who the winner and loser of a specific situation is (Gulas & Weinberger, 2006; Simpson & Bousfield, 2017). And, finally: “From the perspective of relief theory, humour helps a speaker defuse intense interpersonal communication and release tension in the target audience.” (Meyer, 2000 in: Ge & Gretzel, 2018, p. 65). Humor is thus connected generally to pleasant and positive emotional out-comes.

4. P

REVIOUSR

ESEARCHThis chapter will present an overview of some existing literature relevant to my research questions. The review is broadly divided into four categories: first, I will discuss research focusing on humor online in general, secondly, I will discuss research concerning humor as a tool of online (marketing) communication and advertising, thirdly, I will discuss research concerning humor use in crisis communication and finally, research concerning other tools in online marketing and crisis communication.

HUMOR ONLINE

Looking broadly at humor in an online context, Shifman (2007) identifies three characteris-tics of the Internet that lend themselves to expressing and spreading humorous content: interactivity, which is defined as “the process of reciprocal influence” (Shifman, 2007, p. 190); multimedia, as in “the capacity of the Internet […] to convey and combine all existing communication morphologies – script and sound, static pictures and moving images” (Shifman, 2007, p. 190) and global reach. Shifman’s analysis focused on humor websites, that he referred to as “humor hubs”, and concludes, that the internet could function both as a carrier of older humor types, such as jokes in a traditional verbal/ written format, and as a generator of new forms of humorous content, such as user generated animation or manipu-lated images.

A deeper analysis of humor on Twitter comes from Simis-Wilkinson et al. (2018). Building on McGraw’s understanding of humor as benign violations, they analyzed the types of humor used in tweets using the hashtag #overlyhonestmethods, which was popularized by scientist sharing insights into the accident-prone realities of lab work on Twitter. Through a computer

17 aided content analysis of 58.125 tweets over the course of three years, the authors determined that the majority of humorous tweets using the hashtag described minor ethical or otherwise questionable infractions (such as dropping a tray of samples or failing enough times to get a statistically significant result) committed by the person tweeting themselves during a scien-tific investigation. The humor was found to be most often derived from the dichotomy be-tween an idealized image of the scientific process and the reality of accident-prone lab work and often appeared to be somewhat of an in-joke to be enjoyed particularly by other scientists (Simis-Wilkinson et al., 2018).

While Shifman (2007) highlights the opportunities for new forms of humor to exist and develop online, Simis-Wilkinson et al. (2018) focus on Twitter and specifically hashtags as a way of building a network or starting a conversation surrounding one specific humorous trope.

HUMOR IN ADVERTISING AND ONLINE MARKETING

Humor has been a prominent tool in advertising for decades and a subject of interest to scholars for just as long. Writing extensively on the subject Gulas and Weinberger (2006) collected insights from a variety of studies on humor devices used in advertising as can be seen in Table 1.

Study Catanescu and Tom (2001) Weinberger and Spotts (1989)

Research sub-ject

Humor devices in TV and Magazine advertising

Humor in US and UK TV ads Humor devices Comparison,

Exaggeration, Personification, Pun, Sarcasm, Silliness, Surprise, Pun, Understatement, Ludicrous, Joke, Satire, Irony,

Table 1 Humor devices in advertising

A more recent study conducted by Gretzel and Ge (2018) focuses on social media conver-sations initiated by Chinese regional tourist marketing organizations on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. The researchers observed the customer engagement metrics (number of likes, comments and shares) on a variety of posts and concluded that posts coded as hu-morous generally elicited a more positive response from customers – expressed in a high number of likes, comments and shares. Furthermore, image-based humor and humor based

18 on less complex text, were shown to be the most effective in engaging Weibo users (Ge & Gretzel, 2018). Based on Ge and Gretzel’s research, it could be surmised, that the popularity of humor in offline advertising translates somewhat into online marketing communication as well, with humor that is quick and easy to understand, improving the success of such communication.

HUMOR IN CRISIS COMMUNICATION

To determine in what way humorously framed crisis response messages affected organiza-tions’ reputation, Xiao, Cauberghe & Hudders (2018) conducted two experiments, observing respondents’ reactions to two Facebook posts, of which one was framed as a factual crisis situation and the other one as a rumor. The respondents were then shown crisis response messages framed in an aggressive humor style and a self-deprecating humor style. The au-thors concluded that the effectiveness of humor in crisis communication might depend on both the perceived severity of the crisis (rumor based, or event based) and the sincerity of the respondent. If the crisis was perceived as less severe, or not clearly defined, humorous communication was perceived as further decreasing the severity of the situation. Further-more, “the effectiveness of humorous message framing in crisis communication may depend on whether the crisis is confirmed or not (i.e., rumour situation)” (Xiao, Cauberghe, & Hudders, 2018, p. 256). Overall the researchers concluded that humor might be considered a “double-edged sword”(Xiao et al., 2018, p. 247), with humorous crisis responses only being successful in certain situations.

Similarly, investigating the crisis communication of Swedish railway service SJ in response to customer outrage in 2011, Vigsø (2013) concluded that ironic and self-deprecating crisis communication helped improve the company’s reputation, by essentially taking the blame and appearing contrite yet charming. Their analysis showed that SJ’s ironic and self-mocking videos received comments praising the company for its sense of humor. However, SJ appar-ently displayed an inability to further profit from the generated goodwill. Despite the pre-sented successful example of ironic crisis communication, the study concludes that irony should only be used with caution, when faced with a crisis situation due to the risk of being misunderstood and inadvertently causing offense. Furthermore, irony might only be suitable in a crisis where no human lives are threatened in any way (Vigsø, 2013).

Kim, Zhang & Zhang’s (2016) study of Chinese retailer Alibaba’s crisis communication comes to a similar conclusion. Their examination of crisis response messages by Chinese retail company Alibaba, show a positive influence of self-deprecating messages from the

19 company CEO on customers, making the company’s leadership appear more trustworthy and likeable. They further conclude that a humorous strategy may work best in a social media context, if the overall tone of corporate communication is already somewhat informal.

WEBCARE AND COMPLAINT MANAGEMENT

In addition to humor as a tool for trust-building, marketing and complaint management/ crisis communication a number of other strategies have been identified.

Through a survey of 157 people, who had recently interacted with Microsoft through their company blog, Kelleher (2009) identified communication using conversational human voice as a measure which organizations can undertake to increase their network’s trust and com-mitment. Conversational human voice was defined as being open to dialogue, trying to be interesting, using humor and trying to make communication enjoyable (Kelleher, 2009). Re-garding conversational human voice in marketing communications Barcelos et al. (2018), determined that the effects depend on the offered product and company reputation, as a conversational tone was sometimes deemed inappropriate or unprofessional by potential customers.

Building on the idea of a conversational dialogue between organizations and the public, van Noort & Willemsen (2011) and van Noort, Willemsen, Kerkhof & Verhoeven (2016), iden-tified webcare as a strategy for managing online complaint behavior. Webcare essentially means online customer care, using the infrastructures of social media, to engage with cus-tomers and mitigate potential fallout from negative eWOM. This could either happen as a direct response to a complaint or other negative communication (reactive webcare) or as a preemptive measure before a direct complaint is voiced (proactive webcare). Analyzing both the customer and the organizational side of webcare, the researchers identified two main characteristics of proactive webcare: continuous communication with stakeholders and cus-tomers through timely and concise replies and creating and maintaining a friendly, affable image (van Noort & Willemsen, 2011; van Noort, Willemsen, Kerkhof, & Verhoeven, 2016). Steinke’s (2014) research surrounding “Shitstorm-Prevention” corroborates that these strat-egies can help build and strengthen a relationship between a company/ individual and its network, making it less likely for the network to believe damaging rumors and thus pile onto an online firestorm.

20

5. F

RAMEWORK FOR CASE STUDYBefore moving on to the design and execution of my research, this chapter will briefly sum-marize and focus my research query: As theorized by van Dijk (2006) and Li and Bernoff (2009) the continued social media saturation of daily life has led to social media such as Twitter becoming a valuable tool for marketers and organizations to reach stakeholders and potential customers. In a network society, organizations can use the tools afforded by social media such as Twitter - the ability to communicate on three communicative levels (macro, meso and micro) with both individuals and entire networks of individuals, to transmit their messages and to nurture relationships and thus increase both their reach and their esteem. However, in a day and age where social media potentially allows for everyone to communi-cate and connect, regardless of location, time, or any social dividers, organizations now face an empowered and connected audience. This makes it necessary for corporate communica-tion strategies as well as crisis communicacommunica-tion strategies to be reimagined. Social media makes it more likely for complaints or dissent to become public knowledge, leading to paracrises (Coombs, 2007), where organization’s attempts at recovering a favorable image are under public scrutiny. Therefore, corporations must find a way to communicate directly to any party voicing discontent, whilst ensuring that their communication also serves to improve their image in the eyes of a wider audience and strengthens the ties of their existing network. Humor is widely cited as evoking positive emotions and has long been a successful tool in advertising. It might therefore also serve as a tool to gain public favor when used as a way to present a favorable image of an organization or company.

As previously established, the BVG’s humorous response to the online public’s less than friendly reaction to their 2015 marketing campaign, has been widely cited as the reason for turning the initial Shitstorm into a “Lovestorm” (Köhler, 2018) and helping the campaign achieve a high level of success. With regard to the theories and literature outlined above, the idea of humorous communication overcoming adversity, might hold some merit. Conse-quently, the aim of this study is to review the crisis communication strategies employed by the BVG through their official Twitter account @BVG_Kampagne, during the month of January 2015, when the online firestorm occurred, as well as the company’s online marketing communication one year after the crisis, in January 2016.

More specifically, I will observe the use of humor, network interaction and relationship man-agement by the BVG in both crisis stage and post-/ pre-crisis stage by way of a content analysis. Through this analysis of the BVG’s Twitter practices I endeavor to offer an insight

21 into humor-driven marketing and crisis management and an addition to existing research in this field. I opted for this approach, mainly out of my own personal interest in and enjoyment of the BVG’s Twitter activities. In accordance to the theoretical background and the previous research outlined above, I have formulated two research questions:

RQ1: How did the @BVG_Kampagne’s Twitter communication differ between Jan-uary 2015 and JanJan-uary 2016?

RQ2: How was humor a part of the BVG’s crisis communication strategy and their general marketing communication?

To gain an overall understanding of the BVG’s communication strategies I first will examine the characteristics of their Twitter activity with regards to frequency, interaction, which can be a tool for relational management, network building and the use of multimedia content as well as the use of humorous language devices and the overall tone of the tweets, both in times of crisis and after the crisis. However, as noted by Riffe, Lacy and Fico (2014) content analysis often yields results that are mainly descriptive, necessitating a second step in research, in which meaning is inferred from the amassed data. I will, therefore, in a second step analyze how the Twitter activities of the @BVG_Kampagne account, most specifically their tone and humor use, correspond to an operationalization of crisis communication strategies and network driven marketing strategies both during the time of crisis and after the crisis has been overcome.

6. R

ESEARCH DESIGNNow that the what of my study has been established, this chapter focuses on the how, out-lining my methodological considerations7. This research is designed to follow deductive

rea-soning, meaning that the “general statements” (Blaikie, 2007, p. 3) derived from theory and explicated in the previous chapter are applied to specific cases and thus tested (Blaikie, 2007). To answer the research questions outlined above, I chose to conduct a content analysis of every tweet authored by the BVG’s official Twitter account @BVG_Kampagne in January 2015 and January 2016. This methodological approach offers the benefit of providing quan-tifiable results based on an objective and reliable structured assessment. However, as the initial findings were highly descriptive, a second step in the form of a qualitative analysis of my findings was necessary for a more thorough insight. In the following chapter I will

7 Parts of this chapter were previously submitted as part of the final assignment in the Research Methodology course.

22 introduce my method, report on my data collection, coding and analytical process and ad-dress the limitations and ethical considerations of my approach.

METHOD

Content analysis is a scientific method by which text (content) is analyzed based on catego-ries. Generally speaking, content analysis can be used to detect trends or patterns and achieve quantifiable, representative results in media and communications research. Furthermore, content analysis can help make sense of large volumes of data (Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 2014). For the purpose of this study, I chose to conduct a content analysis utilizing categories that were established a priori, based on the theories and previous research outlined above and additionally make use of emergent properties which I developed during the coding process. After coding an initial sample of 111 tweets (74 from January 2015 and 37 tweets from Jan-uary 2016) I revised and adjusted the chosen variables.

Content analysis is traditionally assumed to be grounded in positivism, an epistemology which assumes that social science research can be conducted the same way that natural sci-ence research is; through a systematic, objective analysis based on previously established cat-egories which can ultimately lead to a definite result and an objective truth (Hodkinson, 2011; Stemler, 2001). The basic understanding of positivism blends empiricism (the understanding that knowledge is gained from observation) and rationalism (the understanding that knowledge and theory are obtained through systematic reasoning). Thus, positivism exists within a circle of theory and observation, where one is needed to verify the other (Bhattacherjee, 2012).

Although content analysis is most commonly used in quantitative research, Krippendorff (2019) argues that: “ultimately, all reading of texts is qualitative, even when some character-istics of text are later converted into numbers” (p. 21). Babones (2016) similarly argues, that a research approach which is too focused on being quantitative and positivist simply ignores the more reflexive and qualitative goings-on within the research process and calls for more interpretivist approaches to quantified data.

Despite being conducted as objectively as possible, and producing numerical results, the en-tire design of this research is nonetheless based on my premonition on how to best conduct this analysis; from the choice of theory and consulted literature to the choice of method and inception of coding categories. In fact, I would argue that while I initially designed this re-search with a quantitative approach in mind, the second step of my analysis, which stems in

23 equal parts from the quantified results of my a-priori coding and the qualitative properties which emerged during the research process as well as my deeper knowledge and understand-ing of the wider context of my subject, constitute an interpretivist and more reflexive ap-proach. This somewhat contradicts a strictly positivist research paradigm and gives credence to Blaikie’s (2019) assessment that “a common approach to social research is just to muddle through” (p.1).

SAMPLE

To observe possible shifts in the BVG’s Twitter practice, I chose to observe the Twitter activity of the BVG campaign’s official account @BVG_Kampagne over two different timespans. The first interval I observed, was the month of January 2015, and thus the timespan when the campaign initially kicked off and encountered the brunt of the digital outcry. The second interval was January 2016, 12 months after the campaign’s less than op-timal beginnings and one month after the publishing of viral YouTube video “Is’ mir egal” on the BVG’s official channel brought renewed, positive attention to the campaign. The chosen timespans correspond to the different stages of an organizational crisis as outlined by Coombs (2007). The crisis stage itself occurred in mid-January 2015, leading into post-crisis stage at the end of the month. I initially assumed, that most of January’s tweets should be seen as constituting crisis communication. January 2016 would then represent a pre-crisis stage, as by that point the BVG campaign was highly popular and the 2015 crisis well and truly overcome; tweets from this month would therefore represent the BVG’s marketing communication strategies.

I obtained the sample by accessing Twitter through the website and taking screenshots of every individual tweet. I made use of Twitter’s advanced search feature, searching for all tweets by the @BVG_Kampagne account between January 1st, 2015 and January 31st, 2015

and between January 1st, 2016 and January 31st, 2016. To avoid accidentally coding duplicates,

each tweet was given a unique reference number.

Whilst the campaign Twitter account was set up in December 2014, according to its Twitter bio, it wasn’t activated until January 12th, 2015, when the first tweet was posted. Thus, the

activity in January 2015 occurred between January 12th, 2015 and January 31st, 2015. In this

timespan, the account authored 182 tweets, including original tweets, replies and retweets. Between January 1st, 2016 and January 31st, 2016, the account authored a total of 283 tweets,

24

CODING

When conducting a content analysis text is coded based on predetermined categories and variables, which have been precisely defined and in order to avoid confusion must be mutu-ally exclusive, meaning that no text may fall in between two categories and exhaustive, mean-ing that no text may fall outside of the variables (Hodkinson, 2011; Stemler, 2001).

Since I am the sole author of this paper, I couldn’t enlist the help of a second coder in my research to ensure inter-coder reliability. I therefore coded the sample by myself, starting with an initial sample of 111 tweets to pilot my coding variables and, after revising the vari-ables, which led to some categories being dismissed, coding and subsequently analyzing the entire sample according to the following categories.

Each tweet was initially given an individual reference, based on the tweet date, to avoid ac-cidental duplicate coding. Arranging tweets by date also allowed to test the frequency of Twitter activity. Any tweets that started with an @-Twitter handle were always coded as replies, even if the Twitter interface did not display them as such. For the subsequent analysis of the content, reply tweets as well as retweets (including sub-retweets with or without com-ment) were deemed as proof of an interactive and conversational Twitter practice, relating to relational management and network maintenance. If there was any text or punctuation mark or text written before an @-Twitter handle, the tweet was coded as an original tweet. Tweets including images, videos and links to other sites, were considered examples of mul-timedia content. As mulmul-timedia content has been shown to improve the shareability and overall engagement of social media posts (Ge & Gretzel, 2018), a high number of multimedia

Research aim Coding category Variables

1. Frequency/ Referencing

Date -

2. Interactivity Type of tweet a. Original tweet

b. Reply

c. Retweet/ Sub-retweet

3. Multimedia Tweet content a. Text only

b. Image/ video only c. Text and Media d. Text and Link Other

4. Network Hashtag use a. #weilwirdichlieben

b. Other Hashtag(s) c. None

25 content may be interpreted as an attempt to activate one’s network and initiate the spreading of eWOM.

Due to Twitter’s inherent infrastructure allowing for communication both to a network of followers or as part of a conversation surrounding a hashtag, hashtag use was investigated to further assess strategies for network activation and network outreach. Tweets using the cam-paign hashtag #weilwirdichlieben, specifically could be seen as an attempt to bring more attention to the campaign and interact with an audience beyond one’s own followers, all the while maintaining the focus on the BVG. Likewise, using another hashtag and thus engaging in another conversation could represent an attempt to widen one’s reach into other networks.

Research aim Coding category Variables

5. Human voice Tweet Voice (tone)

a. Informal b. Formal

c. Can’t be determined

6. Humor use Language

De-vices/ rhetorical devices a. Sarcasm/ Irony b. Incongruity/ Surprise c. Pun d. Nonsense/ Silliness e. Exaggeration/ Overstatement f. Satire g. Joke

h. Humorous reference/ Allusion to popular culture

i. Self-mocking j. None of the above k. Comparison l. Personification m. Understatement

7. Tweet Aim This category emerged during the coding to

help me as a kind of memory prop. Both the pilot sample and the entire sample were coded according to the following variables, that were established intuitively during the coding pro-cess: a. Information b. Marketing c. Participation d. Apology e. Amusement f. Other

26 Conversational human voice has been identified as a strategic component of firm initiated conversations and relational management in crisis communications (Kelleher, 2009; Kelleher & Miller, 2006) and was therefore accounted for in this analysis. Tweets using informal voice and / or humor were deemed examples of conversational human voice. The variables were defined with respect to Kelleher’s (2006) and Barcelos et al.’s (2018) research designs, which defined conversational voice as including elements such as emoji use, informal address8 or

use of slang.

To assess the use of humor which may serve as a strategy for image repair by reducing the initial offensiveness of the offense, as suggested by Xiao et al.’s (2018) research, tweets were coded with regards to the use of humorous language. To define the variables, I referred to the humor devices that were found to be prominent in advertising, as presented by Gulas and Weinberger (2006) in chapter 4, as I felt that using rhetorical devices, which had set definitions, might lead to more objective results, than if I had simply observed, whether I myself found the respective tweets funny. After piloting these categories, I elected to elimi-nate three variables which I deemed superfluous and instead added two categories which corresponded more closely with the sample at hand and were backed by findings of other researchers.

The final category “Overall tweet aim” was initially established to help me as a memory prop. The variables were bestowed upon the tweets during the coding process (emergent coding) and weren’t established a priori, ultimately yielding the six denominations seen in Table 3. Information referred to any tweets including information or educational content, such as information about delays or clarifications, as seen in Figure 4. Any tweets referring to the ongoing campaign or any services of the BVG (both on- and offline), such as the tweets seen in Figure 6, were marked as Marketing tweets. Tweets that called for actions or asked ques-tions were considered participatory, whereas tweets that included excuses or genuine apolo-gies (i. e. using the word ‘sorry’) were coded as apology tweets. Amusement included tweets that were judged to be simply posted for comedic reasons and did not match any of the above variables, e. g. the tweets seen in Figure 5.

Adding a qualitative element to my analysis helped me further understand how certain com-munication tools might be used and gave me a deeper insight into the BVG’s Twitter strate-gies. As mentioned previously, research approaches which allow for “variables to posses [sic] emergent properties that may not correspond to the requirements of the research”

8 The German language clearly differentiates between the informal pronouns of address “du/ ihr” and the formal pronouns of address “Sie/ Sie”.

27 (Babones, 2016, p. 459) and thus break with a strictly positivist research paradigm, might lead to a more nuanced understanding in social research. I thus chose to include these findings in my analysis.

PILOT AND REJECTED CODING CATEGORIES

After piloting the categories, I revised the variables of the “Language devices” category – as my initial pilot sample did not offer any tweets using Comparison, Personification or Under-statement, I decided to eliminate those variables and instead added two variables, based on my findings: self-deprecation which had been evident in 3 tweets and had been defined as a humor device in Kim et al.’s (2016) study on crisis communication; and humorous reference, which I added due to the number of tweets referencing popular culture, e. g. Schlager-Stars, soccer and a well-known German graphic novel.

This constituted an act of emergent coding, as defined by Stemler (2001). The sample that had been coded as part of the pilot was reassessed after reviewing the categories. This led to a very small number of tweets being coded differently in select categories during the second coding process, due to the added categories and in two cases due to an oversight (having overlooked a hashtag).

Additionally, I decided to eliminate the following categories, which had initially been part of my codebook:

Rejected category Reason for dismissal

Language The vast majority of tweets was in German. Only 1 tweet in the initial sample had been written in English. I therefore concluded that this category was unnecessary.

Author voice This category was ultimately deemed unnecessary as it only speci-fied one aspect of “Tone” and didn’t add any value to the analysis.

Table 4 Rejected Coding categories

EXAMPLES OF TWEETS

To exemplify my coding process, I have chosen a small number of tweets, which will be discussed in a little more detail. As mentioned before, during the pilot coding, I added the variable “allusion to pop culture/ humorous reference” to my codebook under the “language device” category. One tweet featuring such a reference is displayed in Figure 4: the image used in the tweet references the character of a stern, unpopular teacher from the illustrated story (graphic novel) “Max und Moritz”. Despite being originally published in 1865 and

28 written in verse, the story is still a staple in most German childhoods, and the reference to it is therefore highly recognizable to a German audience. This image was in fact used multiple times by the BVG Twitter account, always alongside its caption “the S-Bahn is not part of the BVG”. In addition to being coded as a “humorous reference”, the tweet (Fig. 4) was coded as an original tweet, consisting of “Text+Media”, using informal/ conversational tone and not using any hashtags. In the “tweet aim” category it was coded as an informational tweet.

Figure 5 Example tweet 150113_23 "Humor Reference"9

Two examples of reply tweets can be seen in Figure 5. Both of these tweets were coded as using informal tone, no hashtag and text only. Both were identified as using humorous lan-guage devices, with one tweet being coded as “Silliness” and the other as “Self-deprecation”. In terms of tweet aim both tweets were understood to be posted for amusement.

9 Translation tweet text: Because we are receiving messages concerning the @SBahnBerlin, here’s a

little reminder from us: